Abstract

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most abundant modification on messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and is catalyzed by methyltransferase-like protein 3 (Mettl3). To understand the role of m6A in a self-renewing somatic tissue, we deleted Mettl3 in epidermal progenitors in vivo. Mice lacking Mettl3 demonstrate marked features of dysfunctional development and self-renewal, including a loss of hair follicle morphogenesis and impaired cell adhesion and polarity associated with oral ulcerations. We show that Mettl3 promotes the m6A-mediated degradation of mRNAs encoding critical histone modifying enzymes. Depletion of Mettl3 results in the loss of m6A on these mRNAs and increases their expression and associated modifications, resulting in widespread gene expression abnormalities that mirror the gross phenotypic abnormalities. Collectively, these results have identified an additional layer of gene regulation within epithelial tissues, revealing an essential role for m6A in the regulation of chromatin modifiers, and underscoring a critical role for Mettl3-catalyzed m6A in proper epithelial development and self-renewal.

Epitranscriptome regulates epigenome to promote proper epithelial development and homeostasis.

INTRODUCTION

Self-renewing somatic tissues, such as the cutaneous and oral epithelia, provide an essential protective barrier throughout life that is constantly self-renewing through a stepwise differentiation program. In the skin, stem-like progenitor cells such as epidermal keratinocytes progress upwards to become terminally differentiated cells that make up a barrier against water loss, injury, and microbes (1). This highly coordinated differentiation process requires precisely regulated spatiotemporal changes in gene expression (2), dysfunction of which can promote both neoplastic and inflammatory skin diseases (3). One emerging area of gene regulation is that of epitranscriptomics (4), or regulated RNA chemical modifications that offer an additional layer of gene regulation beyond modifications to DNA and histones (5). While epitranscriptomic mechanisms have been implicated in a variety of processes ranging from stem cell differentiation to cancer, the role of the epitranscriptome in self-renewing epithelial tissues is poorly understood.

Among RNA modifications, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most abundant chemical modification of mRNAs and is enriched in long internal exons, in the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) and near stop codons in human and mouse transcriptomes (6). m6A is catalyzed cotranscriptionally on nascent pre-mRNA by an evolutionarily conserved, multicomponent writer complex with one known catalytic component, methyltransferase-like 3 (Mettl3). Mettl3-mediated m6A has been shown to regulate various aspects of mRNA metabolism, including both its stability and degradation by phase separation (7), as well as its translation (8–10).

At the organismal level, Mettl3-mediated m6A has been shown to regulate various aspects of cell development and homeostasis. For example, it facilitates rapid transcriptome turnover during cell differentiation to maintain homeostasis (11). Studies have shown that a reduction in m6A levels promotes cell differentiation, while an overall increase of methylation induces stemness and, therefore, suppresses cell differentiation (12). Consistent with this, the loss of m6A via deletion of the writer catalytic subunit Mettl3 promotes differentiation of mouse T cells (13), and down-regulation of Mettl3 promotes up-regulation of hematopoietic cell differentiation genes (14). In contrast, overexpression of Mettl3 has been found in numerous cancers, including epithelial cancers such as oral and cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), and has been shown to be associated with stem-like properties and to accelerate the proliferation, invasion, and migration of SCC cells (15, 16). Despite this, a deep mechanistic understanding of the functional roles of Mettl3 and m6A in self-renewing stratifying somatic epithelia is lacking. Therefore, in this study, we combined both genome-wide methods and in vivo modeling to better understand the role of the Mettl3-m6A epitranscriptome in these critical tissues.

RESULTS

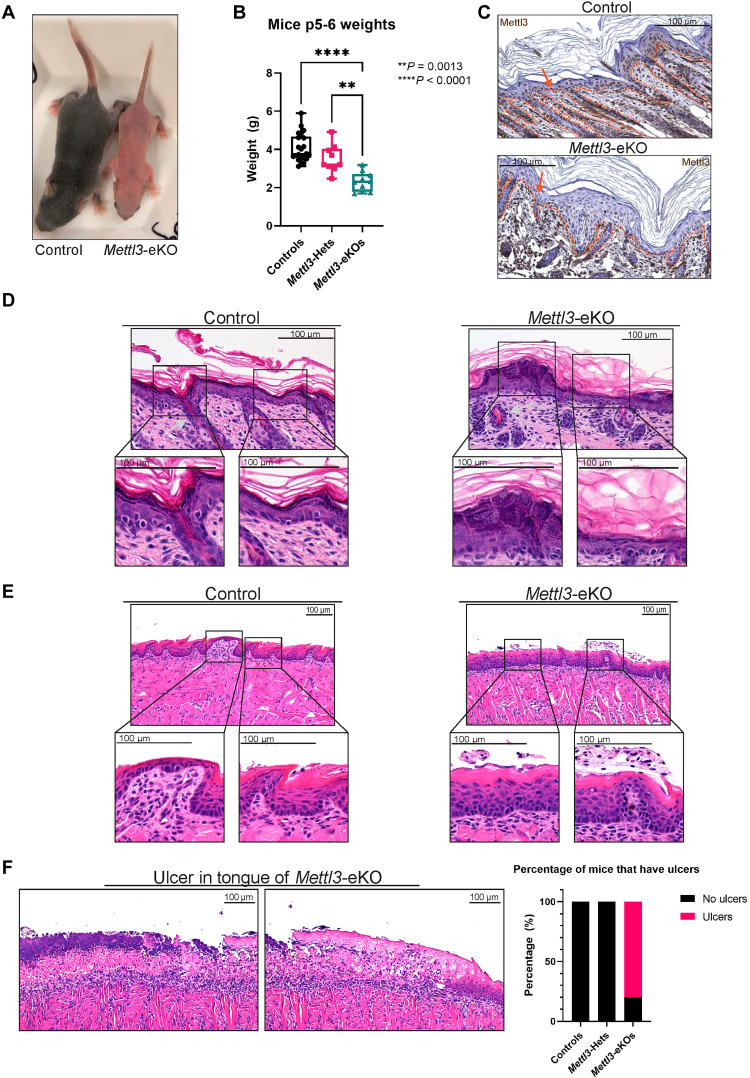

Loss of Mettl3 leads to grossly abnormal epidermal and tongue development

To better understand the role of the epitranscriptome in stratifying epithelia, we created mice with an epithelial-specific deletion of Mettl3 by crossing mice floxed for Mettl3 with mice carrying a keratin 14 (Krt14)–Cre (Krt14-Cre; Mettl3fl/fl or “Mettl3-eKO”), as a whole-body deletion of Mettl3 is embryonic lethal (17). Mettl3-eKO mice did not survive past 1 week of age; thus, we harvested them for our experimental purposes on postnatal day 5 or 6 (P5 or P6). Phenotypically, Mettl3-eKO mice displayed pink skin at P5 and P6 that was notably different in comparison to wild-type (WT) controls (Fig. 1A), suggesting a potential failure to enter anagen, the period of active hair growth from P1 to P12 (18–20). In addition, Mettl3-eKO mice were also about half the size of WT littermates (Fig. 1A). Notably, we observed that Mettl3 heterozygotes weighed more than Mettl3-eKO mice, but less than WT control mice, suggesting that there is a correlation between weight loss with the loss of each allele of Mettl3 (Fig. 1B). Together, these gross observations underscored how critical Mettl3 is for proper epithelial development.

Fig. 1. Loss of Mettl3 leads to grossly abnormal epidermal and tongue development.

(A) Postnatal day 6 (P6) Mettl3-eKO mice display a complete absence of hair and are half the size of WT control littermates. (B) Mettl3-eKO mice weigh less than controls and Mettl3-heterozygotes (“Hets”). (C) IHC of murine dorsal skin. The dotted orange line demarcates the epidermis-dermis junction. The orange arrow signals the nucleus of the keratinocyte in which Mettl3 is found. Controls have Mettl3 present throughout the epidermis, but the staining is gone in the Mettl3-eKO epidermis. (D) Mettl3-eKO skin displays malformed hair follicles (silver arrows), as well as loss of cell polarity in the basal epidermal cells along with thicker granular and cornified layers. (E) Mettl3-eKO oral epithelium of the tongue has malformed filiform papillae and tastebuds. (F) Mettl3-eKO tongues also display large ulcers in the posterior dorsal aspect.

We next examined the epithelial tissues histologically. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) confirmed a complete loss of Mettl3 throughout the epidermis (Fig. 1C). Using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, we saw that the skin of WT mice demonstrated normally formed epidermal layers with fully developed hair follicles and visible hair growth. In contrast, the Mettl3-eKO epidermis revealed several morphological abnormalities. In the basal layer of the interfollicular epidermis (IFE), we found that the cell nuclei were not parallel to each other and displayed a loss of cell polarity, together suggesting potential defects in cell adhesion and proliferation (21). Consistent with a previous study, we observed notable abnormalities in hair follicle morphogenesis (Fig. 1D and fig. S1A) (22). Beyond the loss of cell polarity in the basal IFE, the typical clear separation observed between Krt14 and keratin 10 layers of the IFE were more blurred, suggesting potential dysregulation of the differentiation process (fig. S1B). Consistent with this, we observed increased numbers of Ki67-positive staining cells in both the basal and suprabasal cells in Mettl3-eKO mice in comparison to WT mice, suggestive of potentially accelerated transition of basal progenitors to the suprabasal layers (fig. S1C). In addition, the suprabasal IFE displayed increased thickness of several epidermal layers, including stratum granulosum as well as the stratum corneum (Fig. 1D and fig. S1D). For example, while overall expression of the stratum corneum protein filaggrin did not appear changed, there was a clear thickened stratum granulosum layer below the stratum corneum (fig. S1D).

Because the Krt14-Cre system would also delete Mettl3 in the oral epithelium (23), we next examined the murine tongue. While WT control tongues demonstrated normal taste buds and filiform papillae across the dorsal lingual epithelium, Mettl3-eKO mice displayed severely impaired development of these features (Fig. 1E), consistent with previous work showing that loss of Mettl3 led to severe defects in taste bud development and abnormal epithelial thickening (24). More unexpectedly, however, we observed that 80% of Mettl3-eKO mice were found to have full-thickness ulcerations in the posterior aspect of the tongue, while none were present in WT controls, nor in Mettl3-heterozygotes (Krt14-Cre; Mettl3+/fl) (Fig. 1F), suggesting the Mettl3-eKO mice had impaired cell adhesion. Together, these results demonstrated that Mettl3 is a critical regulator of normal epithelial development and homeostasis.

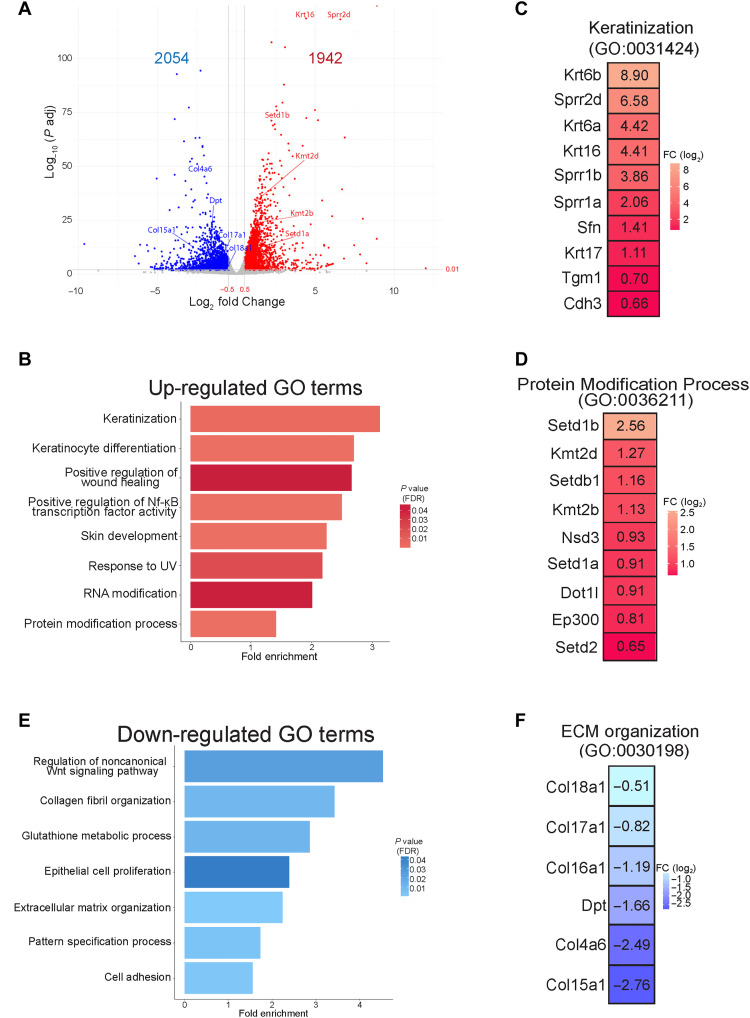

Mettl3 loss promotes marked transcriptional dysregulation

To begin to address the mechanisms behind how Mettl3 loss drove these marked phenotypic changes, we next performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) from the dissected epidermis of Mettl3-eKO mice in comparison with their WT control littermates. Consistent with Mettl3’s established role in mRNA transcript regulation, as well as the numerous phenotypic abnormalities we were observing, Mettl3-eKO mice displayed profound transcriptional dysregulation, with almost 4000 genes displaying significant differential expression upon Mettl3 deletion (Fig. 2A) (table S1). In line with the increased epidermal thickening we observed in the Mettl3-eKO mice, Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of up-regulated genes identified categories such as “keratinization” and “keratinocyte differentiation,” along with specific transcripts like Krt6a, Krt6b, Krt16, and Krt17 (Fig. 2, B and C), all of which are associated with both thickened acral skin such as the human palm or sole, as well as in wounded and/or stressed keratinocytes after injury. Numerous other transcripts associated with keratinocyte terminal differentiation were significantly up-regulated, including prodifferentiation transcription factors (Grhl3), several small proline rich protein (Sprr1a, Sprr2b, Sprr2d, Sprr2f, and Sprr2g), genes and several late cornified envelope (Lce3a, Lce3b, Lce3d, and Lce3f) genes, as well as Tgm1 and Sfn. However, as not all canonical differentiation genes seemed altered (fig. S1E), these results suggested that it was not a simple “turning on” of differentiation, but rather dysregulation.

Fig. 2. Mettl3 loss promotes marked transcriptional dysregulation.

(A) RNA-seq was performed on epidermis from Mettl3-eKO P6 mice (n = 3) versus control littermates (n = 3). A log2 fold change of ±0.5 and an adjusted P value of <0.01 was done to visualize the significant changes. (B) Biological Process Terms Gene Ontology (GO:BP) analysis of up-regulated transcripts in Mettl3-eKO mice. UV, ultraviolet. (C) Highly significant up-regulated transcripts in Mettl3-eKO mice from the “keratinization” category. (D) Highly significant transcripts from the up-regulated “protein modification process” category. (E) GO:BP analysis of down-regulated transcripts in Mettl3-eKO mice. (F) Highly significant down-regulated transcripts of the down-regulated extracellular matrix (ECM) organization category.

In addition, we noted enriched up-regulated categories of “RNA modification” and “protein modification process,” which was particularly intriguing given the emerging role Mettl3 and m6A have been shown to play in the regulation of other epigenetic modifiers in a context-specific fashion (25). Transcripts identified by the “protein modification process” were particularly notable for the broad representation of numerous chromatin modifiers, and in particular, histone methyltransferases. These included four H3K4 methyltransferases, Setd1a, Setd1b, Kmt2b (Mll2), and Kmt2d (Mll4), as well as methyltransferases for H3K36 (Setd2), H3K9 (Setdb1), and H3K79 (Dot1l) (Fig. 2D). This was particularly interesting, as it has been shown previously that forced reduction of H3K4me3 by knockdown of KMT2B could reduce TGM1 in normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs). In addition, knockdown of KMT2D caused a reduction of SPRR2B, together suggesting that these H3K4 methyltransferases may activate many genes involved in different stages of epidermal progenitor cell differentiation (26). In support of this, more recent work has demonstrated the importance of Kmt2d (Mll4) in promoting epidermal differentiation and tumor suppression in vivo (27), while in contrast, enzymes that remove H3K4 methylation can suppress the expression of these terminal differentiation genes (28).

Next, we performed GO analysis on the down-regulated transcripts. In contrast to the enrichment of genes associated with differentiation seen among the up-regulated transcripts, down-regulated transcripts were enriched for pathways and categories typically associated with epithelial progenitor cells and more developmental pathways. These included categories such as “regulation of non-canonical Wnt signaling,” “epithelial cell proliferation,” “extracellular matrix (ECM) organization,” “collagen fibril organization,” “cell adhesion,” and “pattern specification process” (Fig. 2E). All of these GO terms represent categories known to be important for the development and establishment of the basal layer of epithelial surface tissues like the skin epidermis and oral epithelium as well as hair follicle morphogenesis. For example, when examining the transcripts that made up these categories, we noted that numerous collagen genes were down-regulated (Fig. 2F), including Col17a1 (collagen XVII) (fig. S1, A and B), which facilitates epidermal-dermal attachment and regulates proliferation of epidermal stem cells in the IFE (29). Intriguingly, mutations in human COL17A1 are associated with junctional epidermolysis bullosa, a genetic blistering disease of the skin (30, 31), while autoantibodies against collagen XVII are also known to be the primary cause of mucous membrane pemphigoid, a mucous membrane–dominated autoimmune subepithelial blistering disease that causes oral epithelial blistering (32). Collectively, these data present an overall picture whereby a loss of Mettl3 promotes a more differentiated, less progenitor cell–like phenotype. While the aberrant expression of numerous terminal differentiation transcripts may explain the thickened outer layers of the epidermis, the loss of transcripts involved in adhesion, including to the epithelial basement membrane, may offer insight into the loss of polarity observed in the epidermis, as well as the ulcerations observed in the tongue. Last, the broad up-regulation of numerous chromatin modifying enzymes and histone methyltransferases demonstrated that a loss of Mettl3 may function to promote extensive gene expression alterations (and gross phenotypic abnormalities) through large-scale disruption of epigenetic and chromatin states.

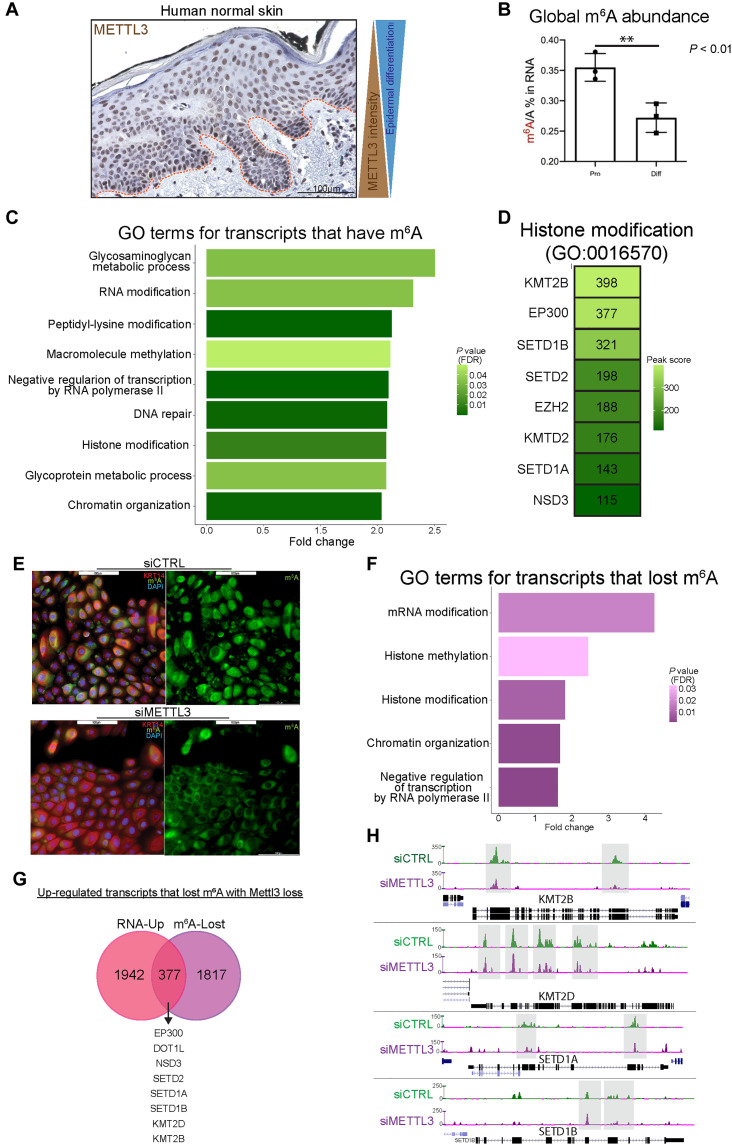

Mettl3-mediated m6A dynamically regulates chromatin modifier mRNAs in epithelia

To gain further insight into the underlying mechanisms behind the phenotype in the Mettl3-eKO mice and how Mettl3 and m6A function in epithelial tissues, we further examined human tissues such as the skin epidermis. Here, we observed that Mettl3 was present in the nuclei of keratinocytes, and its abundance decreased gradually from the basal stem-like progenitors to the terminally differentiated cornified layer (Fig. 3A). Investigation of both mouse (fig. S2, A to F) and human (fig. S3, A to F) publicly available single-cell RNA-seq data atlases clearly demonstrated that the expression of Mettl3 in epidermal keratinocytes gradually diminishes with epidermal differentiation and mirrors that same pattern to what is seen with basal marker Krt14. In contrast, differentiation genes and markers display the opposite pattern (figs. S2, A to F, and S3, A to F). Consistent with this, we found that the global amount of m6A present in transcripts of differentiated keratinocytes was reduced in comparison to the progenitors upon in vitro differentiation of primary human keratinocytes (Fig. 3B). Together, these results suggested that higher levels of expression of Mettl3 and m6A were associated with a more stem-like progenitor cell state, while reduced levels correlated with more differentiated epidermal cells and layers. This was consistent with our RNA-seq data that suggested that in vivo deletion of Mettl3 promoted a more differentiated, less progenitor-like transcriptional phenotype.

Fig. 3. Mettl3-mediated m6A dynamically regulates chromatin modifier mRNAs in epithelia.

(A) IHC of Mettl3 in normal human skin, where above the dotted line is the epidermis. (B) Quantitative analysis of the m6A level by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry done in proliferating versus differentiated neonatal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs) demonstrates reduced global m6A with differentiation. (C) GO analysis of transcripts which contain m6A peaks enriched in epidermal progenitors. (D) Representative transcripts of the “histone modification” GO:BP category. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (E) Mettl3 siRNA reduces visible m6A in NHEKs. (F) GO analysis of transcripts which contain m6A peaks that are lost with siRNA depletion of Mettl3. (G) Overlap of the up-regulated transcripts by RNA-seq (pink) and transcripts that lost m6A peaks with Mettl3 depletion (purple). (H) UCSC Genome Browser on Human (GRCh37/hg19) tracks from the m6A-seq analysis to visualize the decrease of m6A peaks in representative “histone modification” transcripts in control (green) and Mettl3-depleted NHEKs (purple).

Next, using this human epidermal progenitor cell model, we knocked down Mettl3 via small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and examined m6A (fig. S4A). We then performed m6A sequencing (m6A-seq) to map m6A across all the mRNAs in the transcriptome. As previously reported, m6A was enriched in DRACH motifs (fig. S4B). After calling common peaks across all human donor samples (table S2), we performed GO analysis to identify any enriched categories of m6A-modified mRNAs within the epidermal progenitors. Intriguingly, similar to the RNA-seq data in mice, our human model m6A-seq was enriched in categories representing epigenetic modifications, such as “peptidyl-lysine modification,” “macromolecule methylation,” “histone modification,” and “chromatin organization” (Fig. 3C). Within these categories, we found represented many of the same H3K4 methyltransferase transcripts including SETD1A, SETD1B, KMT2B, and KMT2D (Fig. 3D). We next confirmed that siRNA Mettl3 knockdown keratinocytes displayed global reductions in m6A (Fig. 3E) and then further interrogated these results to elucidate which transcripts lose m6A upon Mettl3 depletion (table S2). To do this, we performed GO analysis on transcripts that displayed a significant reduction in m6A with siRNA Mettl3 knockdown, and once again, we saw that transcripts pertaining to the biological process categories of “histone methylation,” “histone modification,” and “chromatin organization” were particularly enriched for a loss of m6A (Fig. 3F). Notably, all of these epigenetic modifiers were among the 378 transcripts that displayed both reduced m6A and increased mRNA abundance with Mettl3 depletion (Fig. 3G). In contrast, only 152 transcripts that lost m6A also showed reduced mRNA expression (fig. S4C). Direct visualization of these changes demonstrated that the intensity of m6A enrichment had decreased substantially in the transcripts of SETD1A, SETD1B, KMT2B, and KMT2D in long internal exons, stop codons, and/or 3′UTRs (Fig. 3H). These data suggested that Mettl3-mediated m6A was directly regulating the abundance of these chromatin modifier mRNAs. In contrast, canonical keratinocyte genes associated with either the progenitor state (COL17A1 and COL7A1) or the differentiated state (LCE genes and SPRR genes) that were dysregulated with Mettl3 deletion did not display m6A enrichment or loss. To look at these expression associations in a human disease context, we examined gene expression data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Intriguingly, consistent with our results, we found an inverse correlation between METTL3 expression and the expression of histone methyltransferases in two epithelial cancers [head and neck SCC (HNSCC) and lung SCC (LUSC)] (fig. S4, D and E), suggesting that the gene regulatory relationships observed in our model systems under homeostatic conditions might also be reflective of what is occurring in diverse disease states.

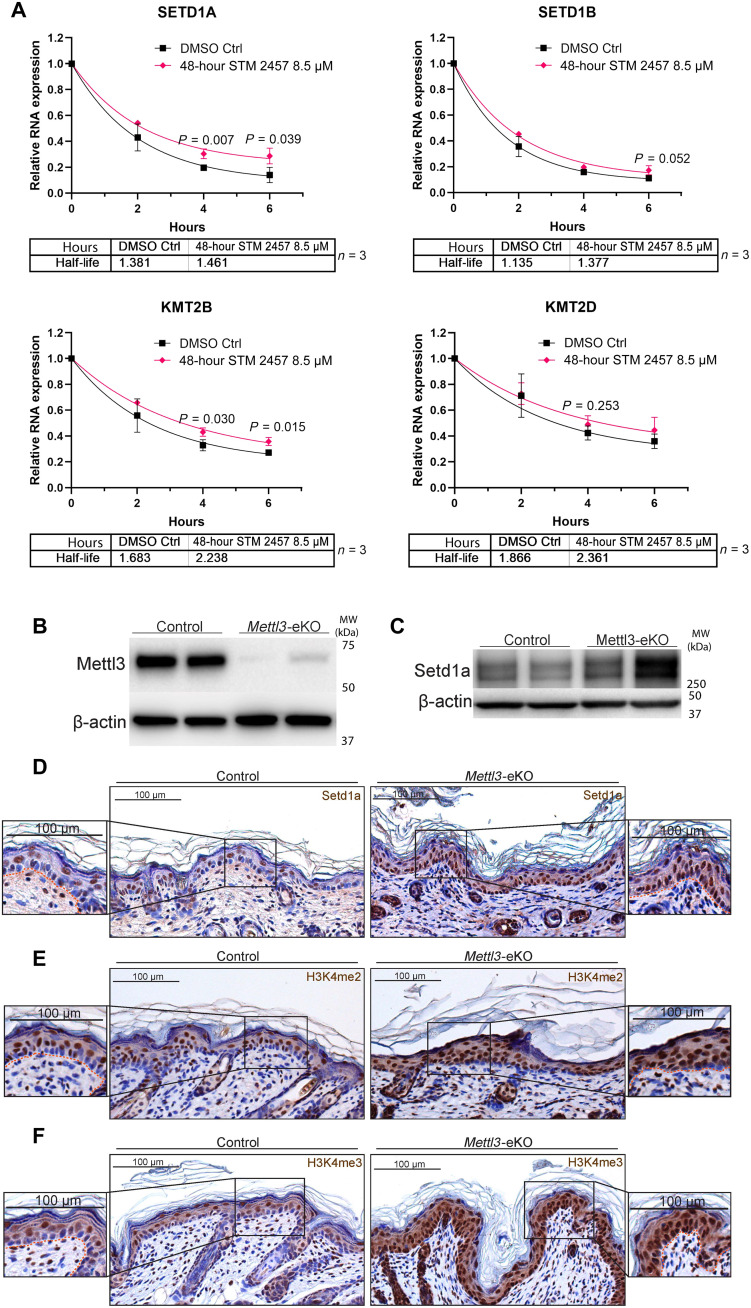

Mettl3 loss increases mRNA half-life and enhances the expression of chromatin modifiers

Given our data demonstrating that a loss of Mettl3-mediated m6A on chromatin modifying enzyme transcripts was associated with their increased expression, we wanted to test whether Mettl3 depletion was affecting the degradation of these transcripts. To do this, we used a mRNA turnover assay (33), which measures mRNA stability following the inhibition of transcription with actinomycin D. By inhibiting the synthesis of new mRNA, this allows for the measurement of mRNA decay by measuring mRNA abundance (34). Using this approach we measured the mRNA half-life of the KMT2B, KMT2D, SETD1A, and SETD1B transcripts in epidermal progenitors. In addition, to test whether these associations were due directly to the depletion of m6A over these transcripts (in contrast to some other non-catalytic function of Mettl3), we used a highly specific catalytic inhibitor of Mettl3 (STM2457). STM2457 potently and significantly reduced global m6A levels and generally recapitulated the gene expression changes observed in our mouse model in the epidermal progenitors following just 48 hours of exposure (fig. S5B). Through this approach, we observed that KMT2B, KMT2D, SETD1B, and SETD1A transcripts displayed evidence of a longer mRNA half-life upon Mettl3-mediated m6A inhibition (Fig. 4A and fig. S5C). Similar trends were observed using genetic depletion studies with both siRNAs and shRNAs for METTL3 (fig. S5D). While not all results reached statistical significance in every case, the trends were consistent across the differing systems and also contrasted sharply with other dysregulated transcript that did not display similar patterns. For example, collagen genes that lost expression in the Mettl3-eKO mice displayed a more linear degradation pattern without evidence of increased stability in contrast to the chromatin modifier genes (fig. S5, E versus F). Collectively, these data supported a model whereby the loss of Mettl3-mediated m6A was leading to reduced degradation of chromatin modifier mRNA transcripts.

Fig. 4. Mettl3 loss increases mRNA half-life and expression of chromatin modifiers.

(A) mRNA turnover assay to measure the mRNA half-life transcripts in epidermal progenitors demonstrates prolonged half-life of SETD1A, SETD1B, and KMT2B transcripts with METTL3 depletion. KMT2D transcripts shows a trend of prolonged half-life with METTL3 depletion. Transcripts were normalized by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. (B) Immunoblotting of Mettl3 in control versus Mettl3-eKO P6 mouse epidermis. (C) High-molecular weight Western blot for Setd1a in P6 mouse epidermis. (D) IHC for Setd1a in P6 mouse epidermis. (E) IHC for H3K4me2 in P6 mouse epidermis. (F) IHC for H3K4me3 in P6 mouse epidermis.

Given these findings, we next asked whether these increases in mRNA transcript levels were also seen at the protein level, suggesting reduced mRNA degradation. We first examined Setd1a given its relatively abundant expression in human skin as per the Human Protein Atlas, as well as its essentiality for early mouse embryonic development (35). Western blotting demonstrated an up-regulation of Setd1a protein levels in Mettl3-eKO mice in comparison to WT controls (Fig. 4, B and C). Upon staining the epidermis of Mettl3-eKO mice with Setd1a antibodies, we both confirmed the increased expression of the protein but also noted that it was particularly enriched in the basal epidermal progenitors of the Mettl3-eKO mice in comparison to WT mice where it was largely absent from the basal cells (Fig 4D). As Setd1a is one of the major H3K4 histone methyltransferases in cells, we next interrogated levels of H3K4me2, which marks the gene body for activation, and H3K4me3, which primarily marks transcription start sites (36, 37). Consistent with increased expression of multiple H3K4 methyltransferases including Setd1a, we found increased levels of both modifications throughout the epidermis (Fig. 4, E and F). In addition, similar to Setd1a expression, we also saw a particular enrichment of the modifications in the basal epidermal progenitors of Mettl3-eKO mice in comparison to WT controls (Fig. 4, E and F).

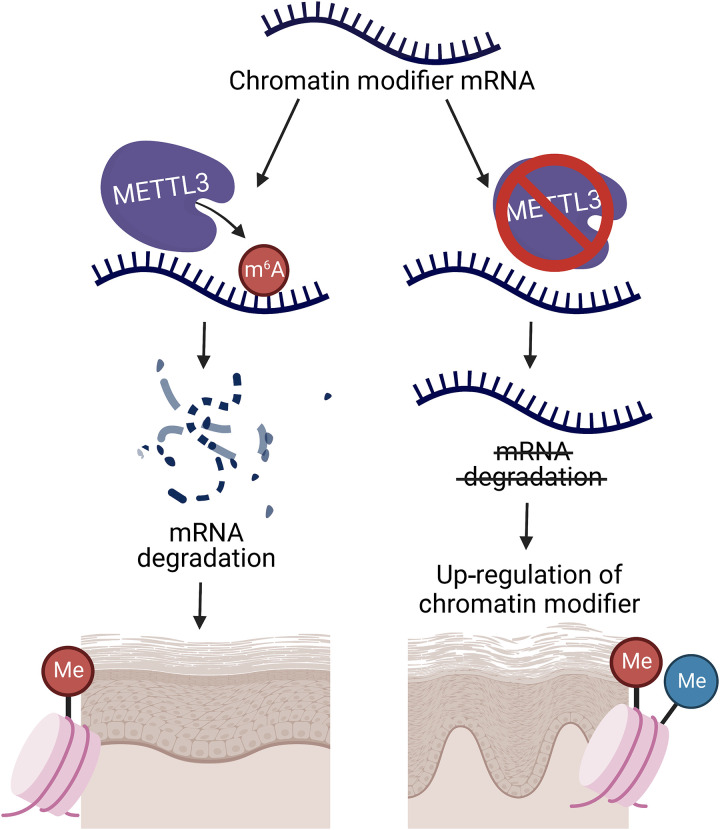

Together, these data suggest a model whereby Mettl3-catalyzed m6A on H3K4 methyltransferase mRNAs promotes their degradation. In the absence of Mettl3, m6A is lost on these transcripts and their reduced degradation leads to their increased mRNA and protein abundance, ultimately resulting in both extensive epigenetic and phenotypic dysregulation (Fig. 5). Notably, enzymes that remove H3K4 methylation (i.e., the histone demethylase, LSD1) have been shown to repress differentiation (28), while enzymes that catalyze H3K4 methylation (i.e., KMT2D/MLL4) have been shown to promote differentiation (26, 27, 38). Thus, this aberrant increased expression of these modifiers and the resulting increased H3K4 methylation in basal epidermal progenitors can promote the aberrant activation of more terminal differentiation genes and a loss of the progenitor state. This model is also consistent with emerging data demonstrating the existence of extensive cross-talk between epitranscriptomics and epigenetics (25).

Fig. 5. Schematic of Mettl3-mediated m6A gene regulation in self-renewing stratifying epithelial tissues.

Loss of the Mettl3-m6A epitranscriptome promotes the up-regulation of chromatin modifiers by reducing mRNA degradation to promote increased mRNA half-life. This up-regulation of chromatin modifiers and, in turn, their associated histone modifications leads to dysfunctional epidermal development and differentiation.

DISCUSSION

Our present study demonstrates that Mettl3 is critical for the proper development of stratifying epithelial tissues and for maintaining the precise regulation of chromatin modifiers and histone modifications in these tissues. Building upon previous evidence of a role for Mettl3 in hair follicle development (22), our results demonstrate a critical role for Mettl3 and m6A in the direct regulation of the epigenome in stratifying epithelia. Specifically, we find that deletion of the m6A catalytic writer protein Mettl3 in the epithelial tissues of mice results in a notable phenotype in which the Mettl3-eKO mice are half the size and weight of their control littermates, are hairless, and unable to survive past a week while WT control littermates are healthy and thriving. In addition to the loss of normal hair follicle structures, basal layer keratinocytes in the IFE display a loss of polarity and adhesion along the basement membrane, while the oral epithelium of the tongue displays notable ulcerations. In contrast, the more differentiated granular and the cornified layers are thicker. Consistent with these phenotypic alterations, RNA-seq demonstrated a broad loss of expression of genes involved in the epidermal progenitor state and adhesion to the basement membrane. These included adhesion genes like Col7a1 and Col17a1, as well as genes associated with Wnt signaling and hair follicle stem cells (i.e., Lef1, Wnt5a, Wnt7a, and Krt15). In contrast, up-regulated genes included a variety of proteins associated with epithelial thickening and differentiation as well as numerous epigenetic regulators.

Mechanistically, we find that Mettl3 depletion reduces m6A preferentially at chromatin modifying enzymes, and at H3K4 methyltransferases in particular. Using a highly specific inhibitor of Mettl3’s catalytic function recapitulated these results, supporting the conclusion that these results were due directly to the loss of m6A on these transcripts (Fig. 4 and fig. S5). This results in specific notable increases in the mRNA levels of these transcripts due to impaired degradation (Figs. 4 and 5). While previous data have shown that increases in H3K4 methylation are associated with epithelial differentiation (26, 27, 38), our data demonstrate that Mettl3 and m6A follow the opposite pattern and display reduced levels with differentiation. Our results further show that the observed changes in expression of differentiation genes (decreases in progenitor- and epidermal basement membrane–associated genes along with concomitant increases in terminal differentiation genes) are more likely secondary effects due to the widespread epigenetic dysregulation that occurs, in contrast to the direct m6A-mediated effects that loss of Mettl3 promotes on chromatin modifying transcripts.

Consistent with this model is a growing consensus in the field that a primary function of m6A is to promote mRNA degradation (39). For example, recent evidence suggests that YTHDF epitranscriptomic reader proteins act redundantly to induce degradation of the same mRNAs (40). In addition, these data are in line with extensive emerging evidence to show abundant interplay between epigenetics and the Mettl3-m6A epitranscriptome (25). For example, m6A has been shown to also promote the destabilization and degradation of chromatin modifying enzymes in neural stem cells (41). Furthermore, in addition to our results suggesting that H3K4 methylation was the primary modification to be regulated, other more recent studies have observed similar phenomena affecting heterochromatic marks such as H3K27me3 (42) and H3K9me2 (43).

In summary, our results demonstrate how m6A regulates epigenetic regulators in epithelial tissues. They have revealed an additional layer of complexity to the epigenetic regulation of epithelial development and differentiation. While these results underscore the essential nature of normal Mettl3 and m6A function during epithelial development, important outstanding questions still remain, including what effects the postdevelopment somatic loss of Mettl3 might have. In addition, much remains to be found regarding the importance of epitranscriptomic regulation in epithelial diseases, particularly beyond cancers. However, even with the little we do know at this time, already potential therapeutic opportunities can be envisioned. For example, while Mettl3 has been shown to be overexpressed in epithelial cancers like SCCs (44), KMT2D/MLL4 is a known tumor suppressor that is frequently lost in those same cancers (28). As there are numerous inhibitors of Mettl3 being developed currently (45, 46), these data suggest that Mettl3 inhibition could play a dually effective role of both inhibiting Mettl3 and increasing the expression of important tumor suppressors like KMT2D/MLL4. Given the great interest in and potential of drugs targeting epigenetic and epitranscriptomic regulators, we anticipate the results presented here will help inform those future studies in lieu of the epigenetic-epitranscriptomic cross-talk uncovered here.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania. Mice were maintained on a C57BL/6 background. Mice carrying Mettl3 floxed alleles crossed with Krt14-Cre transgenic mice. Krt14-Cre; Mettl3fl/fl (Mettl3-eKO) were considered mutants. Unless noted otherwise, littermates homozygous for the Mettl3 alleles of interest lacking Krt14-Cre were used as controls. The generation of Mettl3fl/fl mice has been described elsewhere (13).

Genotyping

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was done using a Thermo Phire Animal Tissue PCR kit (F140WH). All experimental mice were an equal mix of males and females. The number of animals used per experiment is stated in the figure legends.

Weight collection

Before euthanasia, mice at 6 days of age were measured for total body weight. Data figures are the composite of multiple litters of Mettl3-eKO or littermate controls. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to calculate the significance between groups when considered for genotype. All P values are noted in figure legends and were considered significant if P < 0.05 and nonsignificant (NS) if P > 0.05.

Mice RNA and protein extraction

Murine epidermis was dissociated from the dermis before the isolation of bulk RNA and protein. Following the euthanasia of 6-day-old mice, the skin was dissected, and the underlying fat pad was removed using a scalpel. The resulting tissue was floated dermis side down in dispase (5 U/ml; Corning) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 40 min at 37°C. The epidermis was then removed using a scalpel, and for RNA, the epidermis was flash frozen in TRIzol and stored at −80°C until RNA isolation. RNA was extracted using an RNeasy kit (no. 74104, QIAGEN) at the same time and date for all mice belonging to a single experimental cohort (i.e., RNA-seq) regardless of the date of murine euthanasia to reduce batch effects and stored at −80°C. For protein, the epidermis was placed directly into cold PBS and centrifuged at 4°C for 5 min at 2500 rpm. To the resulting pellet, protein lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail was added, and the mixture was homogenized, sonicated, rotated at 4°C for 10 min, and then centrifuged at 4°C at full speed for 10 min. Lysates were quantified using the Bradford assay. Frozen lysates were stored at −80°C.

Two-dimensional cell culture

Proliferating primary NHEKs (or epidermal progenitors) cells were isolated from deidentified discarded neonatal foreskin provided by Core B - Skin Translational Research Core (STaR) of the Penn Skin Biology and Diseases Resource-based Center (NIH P30-AR069589). NHEK medium is a filtered 50:50 mix of 1× keratinocyte serum-free medium (keratinocyte-SFM) supplemented with human recombinant epidermal growth factor and pituitary extract combined with medium 154 supplemented with human keratinocyte growth supplement and 1% 10,000 penicillin-streptomycin (U/ml). Incubator: 37°C with 5% CO2. Proliferating NHEKs were cultured in NHEK medium under normal incubating conditions. Differentiating NHEKs arise from seeding proliferating NHEKs in NHEK medium for the first 24 hours after seeding and then changing the NHEK medium containing 1.22 mM calcium chloride (CaCl2) for 72 hours.

Small interfering RNAs

Proliferating NHEK cells were cultured in penicillin-streptomycin free NHEK media, and 24 hours later, the scrambled control siRNAs (siCTRL) or the siRNAs against METTL3 (siMETTL3) were added at 500 nM dose for 72 hours under normal incubation conditions, changing to fresh penicillin-streptomycin free medium at 48 hours to prevent cell differentiation. Cells were harvested 72 hours after transfection.

Polymerase chain reaction

Complementary DNA was obtained using a high-capacity RNA-to- DNA kit (no. 4368814, Thermo Fisher Scientific). For quantitative real-time PCR, Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (no. 4367659, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used. Quantitative real-time PCR data analysis was performed by first obtaining the normalized cycle threshold (Ct) values (normalized to β-actin and GAPDH RNA), and the 2−ΔΔCT method was applied to calculate the relative gene expression. ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System was used to perform the reaction (Applied Biosystems). The average and SDs were assessed for significance using a Student’s t test. All P values are noted in the figure legends and were considered significant if P < 0.05 and nonsignificant (NS) if P > 0.05.

Short hairpin RNAs

We generated stable fresh METTL3 knockdown in proliferating NHEK cells and, after two or three passages to avoid compensatory mechanisms of loss of knockdown, we performed experiments.

STM2547 treatment

Proliferating NHEK cells were cultured in NHEK media, and 24 hours later, dimethyl sulfoxide (vehicle control) or STM2457 (Selleck, no. S9870) at 8.5 μM was added for 48 hours under normal incubation conditions. Cells were harvested 48 hours to investigate METTL3 catalytic inhibition.

mRNA turnover assay

To assess the half-life of mRNA, actinomycin D was used to treat the proliferating NHEK cells after short hairpin RNA knockdown or STM2547 treatment. After the treatment, mRNA expression level at 0, 2, 4, and 6 hours was analyzed via real-time quantitative PCR with half-life statistics performed via a nonlinear analysis of a one phase decay model as described previously (33).

Quantitative analysis of the m6A level via liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

The PolyA+ RNA was extracted from total RNA using the Dynabeads mRNA Purification Kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified RNA was digested and dephosphorylated to single nucleosides using Nucleoside Digestion Mix (NEB, M0649S) at 37°C for 1 hour. The detailed procedure was as previously described (47). The nucleosides were quantified using retention time and the nucleoside-to-base ion mass transitions of 282.1 to 150.1 (m6A) and 268.0 to 136.0 (A). All quantifications were performed by converting the peak area from the liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry to moles using the standard curve obtained from pure nucleoside standards running with the same group of samples. Then, the percentage ratio of m6A to A was used to compare the different modification levels.

Single-cell RNA-seq analyses

Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) data from murine skin and keratinocytes was derived from the Gene Expression Omnibus dataset GSE154679. Human skin scRNA-seq data were obtained from the GTEx Portal dbGaP accession number phs000424.v9. The human (48) and murine (49) data were separately processed and analyzed as follows: Data were individually filtered on the basis of standard filtering before combining them using Seurat V4 62. First, poorly sequenced cells with a low number of genes detected were excluded. Then, cells that were likely to be doublets were removed. Additional removal of doublets was done with a doublet finder (scDblFinder) to further filter doublets (50). Each dataset was then normalized, filtered for epidermal keratinocytes, and visualized with FindVariableFeatures, ScaleData, and RunPCA. This was followed by RunUMAP (performing reductions with Harmony that significantly improve batch effects (51), FindNeighbors, and FindClusters. Last, selection and visualization via violin plots was conducted of METTL3/Mettl3, KRT14/Krt14, KRT10/Krt10, KRT1/Krt1, and LOR/Lor transcripts.

m6A sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit (catalog no./ID: 74104). The following protocol was performed with 35 to 50 μg of total RNA. mRNA was purified with Dynabeads mRNA purification kit (Invitrogen Catalog No. 61006). Fragmentation of the mRNA was performed using the Ambion RNA fragmentation reagents (catalog no. AM8740), and then the mRNA was subjected to the RNA Clean and Concentrator-5 (catalog no. R1013 from Zymo Research). mRNA quality was checked by Aligent BioAnalyzer 2100 using the RNA 6000 Pico Kit (part number 5067-1513). One round of m6A immunoprecipitation was performed using the EpiMark N6-Methyladenosine Enrichment Kit (NEB no. E1610S) and protocol. m6A-seq libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA library preparation kit for Illumina (NEB no. E7760). Library quality was checked by Agilent BioAnalyzer 2100 using the High Sensitivity DNA kit (part number 5067-4626), and libraries were quantified using the Library Quant Kit for Illumina (NEB no. 7630). Libraries were then sequenced using a NextSeq 500 platform [75–base pair (bp) single-end reads]. All kits were used following the manufacturer’s instructions.

m6A-seq data processing

First, sequence quality was verified using fastqc. We used bowtie2 to map reads to the genome of mouse (mm10) with default parameters. Then, bedtools were used to remove the reads that contained low-quality bases (MAPQ <10) and undetermined bases. Mapped reads of input (IP) and input libraries were processed by macs2 callpeak function, which identifies m6A peaks with bed or bam format that can be adapted for visualization on the UCSC genome browser. We called the peaks using the threshold of false discovery rate < 0.05, no shifting model building, extension size of 200 bp, and the removal of duplicates. HOMER is used for both the annotation of the called peaks and the de novo and known motif finding followed by localization of the motif with respect to peak summit. The differentially expressed peaks were selected with an absolute value of a fold change >2 (and P < 0.05) by R package deseq2 (52). Specifically for the motif analysis, HOMER was used for the de novo and known motif finding by perl scripts. In particular, we specified the motif finding size parameter in findMotifsGenome.pl to 200 bp. We sorted the predicted motif in the fig. S2B. According to the P value, and the smaller the P value, the higher the rank. The most commonly reported motif structures are RRACH (where R = A or G, H = A, C or U). The differential m6A peaks were characterized by the GGACT motif, which is the first-rank motif structure from the merged prosiCtrl sample.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit (Cat No./ID: 74104). The following protocol was performed with 1 μg of total RNA. mRNA was purified using the NEBNext poly(A) mRNA magnetic isolation module. RNA-seq libraries were prepared using NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA library preparation kit for Illumina (NEB no. E7760). Library quality was checked by Agilent BioAnalyzer 2100 using the DNA 1000 kit (part number 5067-1504), and libraries were quantified using the Library Quant Kit for Illumina (NEB no. 7630). Libraries were then sequenced using a NextSeq 500 platform (75-bp single-end reads).

RNA-seq data processing

All RNA-seq was aligned using RNA STAR (53) under default settings to Mus musculus GRCm38 FPKM (fragments per kilobase per million mapped fragments) generation and differential expression analysis were performed using DESeq2 (52). Statistical significance was obtained using an adjusted P value (padj) generated by DESeq2 of less than 0.01.

GO analyses

All GO analyses were performed using PANTHER on Bioconductor (DOI: 10.18129/B9.bioc.PANTHER.db) to determine statistically overrepresented GO terms using Fisher’s exact test under the category “biological process.” P values for GO terms are false discovery rate statistics. The top eight plotted GO terms represent the GO terms with the highest fold enrichment under PANTHER’s default hierarchical clustering categorization. GO term figures are generated using ggplot2.

Immunoblotting

Samples were separated by electrophoresis in 4 to 20% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels with 30 μg per lane, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and blotted with antibodies. Secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagents (catalog no. RPN2232, GE Healthcare) were used for detection. For high–molecular weight proteins, samples were separated by electrophoresis in 3 to 18% tris-acetate gel electrophoresis gels with 30 μg per lane, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and blotted with antibodies. Secondary HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagents (catalog no. RPN2232, GE Healthcare) were used for detection.

Histology

Mouse dorsal and ventral skin tissues were processed for histological examination by Core A - Cutaneous Phenomics and Transcriptomics (CPAT) Core of the Penn Skin Biology and Diseases Resource-based Center (NIH P30-AR069589) and mounted on frost-free slides. H&E staining was processed by Penn Skin Biology and Disease Resource-based Center Core A. A Leica DM6 B microscope was used to observe and capture representative images. Exposure times and microscope intensity were kept constant for all human samples and across mouse littermate comparisons.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue slides were baked for 1 hour at 65°C, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated through a series of graded alcohols. After diH2O washes, slides were treated with antigen unmasking solution (1:100; SKU H-3300-250, Vector Laboratories) at 95°C for 12 min according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Hydrogen peroxide, blocking, primary antibody binding, HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, and 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) were done using the Mouse and Rabbit Specific HRP/DAB IHC Detection Kit - Micro-polymer (ab236466, Abcam). Before the protein block, tissues were treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 diluted in 1× tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 5 min to unmask the antigens expressed in the nucleus. After overnight primary antibody incubation at 4°C and endogenous treatment with secondary anti-rabbit antibody at room temperature (RT) for 20 min, the staining was visualized with DAB with exposure times synchronized throughout all tissue samples within an antibody group for the exact same time. All slides were counterstained with hematoxylin (Hematoxylin QS, H-3404, Vector Laboratories) for 20 s at RT, dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in xylene, and mounted with VectaMount (permanent mounting medium, H-5000, Vector Laboratories).

Immunocytochemistry

Proliferating NHEKs with METTL3-KD were cultured in a chamber slide after being coated with 0.1% gelatin for 30 min at 37°C. After 48 hours, the chamber slides were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 25 min at RT and then washed with 1× DPBS. Chambers were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in Dulbecco’s PBS for 10 min and blocked with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Dulbecco’s PBS for 2 hours in RT at gentle shaking. Primary antibodies diluted in 5% BSA in Dulbecco’s PBS were incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. Following fluorescent secondary antibody treatment 1 hour at RT in gentle shaking, the sections were mounted with ProLong Gold with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (catalog no. P36935, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

TCGA RNA-seq analyses

Data from TCGA was downloaded from cBioportal (www.cbioportal.org/) on 19 April 2023. Specifically, RNA-seq v2 data of HNSCC and LUSC was downloaded. For each gene, the correlation between genes in each RNA-seq dataset was analyzed using Pearson analysis and the P values were extracted using R function rquery.cormat. The correlation plot was drawn using the corrplot (version 0.92) package in R 4.1.2.

Immunofluorescence

Tissue slides were baked for 1 hour at 65°C, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated through a series of graded alcohols. After diH2O washes, slides were treated with antigen unmasking solution (1:100; SKU H-3300-250, Vector Laboratories) at 95°C for 12 min according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Hydrogen peroxide, blocking, primary antibody binding, and secondary antibody binding were done using the Mouse and Rabbit Specific HRP/DAB IHC Detection Kit - Micro-polymer (ab236466, Abcam). Before the protein block, tissues were treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 diluted in 1× TBS for 5 min to unmask the antigens expressed in the nucleus. After overnight, primary antibody incubation at 4°C and endogenous treatment with secondary fluorescent antibodies at RT for 1 hour. All slides are mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (P36935, Invitrogen).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using R or GraphPad Prism 8. Details of each statistical test are included in Materials and Methods. Sample sizes and P values are included in the figure legends or main figures. Investigators were not blinded during experiments or outcome assessment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank R. Flavell of Yale University for donation of the Mettl3fl/fl mice.

Funding: This research was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) of the National Institutes of Health (K08AR070289) (to B.C.C.), NIAMS of the National Institutes of Health (R01AR077615) (to B.C.C.), NIAMS of the National Institutes of Health (T32AR007465 to A.M.M.L.), National Institutes of Health grants (R35GM133721 and R01HL160726 to K.F.L.), Dermatology Foundation Stiefel Award for Skin Cancer (to B.C.C.), Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation Clinical Investigator Award (to B.C.C.), and Skin Cancer Foundation Todd Nagel Memorial Research Award (to B.C.C.). This research was also supported by Cores A and B of the Penn Skin Biology and Diseases Resource-based Center funded by NIAMS (P30AR069589).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: A.M.M.L. and B.C.C. Data curation: A.M.M.L. and B.C.C. Formal analysis: A.M.M.L., S.H., R.A.R.H., J.T.S., K.F.L., and B.C.C. Investigation: A.M.M.L., G.P., E.K.K., H.S., J.S., M.S., A.A., S.P., N.K., C.A.D., and H.E. Supervision: B.C.C. Visualization: A.M.M.L., S.H., and R.A.R.H. Validation: A.M.M.L., S.H., R.A.R.H., J.T.S., K.F.L., and B.C.C. Writing—original draft: A.M.M.L. and B.C.C. Writing—review and editing: A.M.M.L., S.H., G.P., E.K.K., N.K., C.A.D., R.A.R.H., H.E., H.S., J.S., M.S., A.A., S.P., H.-B.L., J.T.S., K.F.L., and B.C.C.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S6

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Data S1 and S2

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.A. Baroni, E. Buommino, V. de Gregorio, E. Ruocco, V. Ruocco, R. Wolf, Structure and function of the epidermis related to barrier properties. Clin. Dermatol. 30, 257–262 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Y. A. Miroshnikova, I. Cohen, E. Ezhkova, S. A. Wickstrom, Epigenetic gene regulation, chromatin structure, and force-induced chromatin remodelling in epidermal development and homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 55, 46–51 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.P. Rousselle, E. Gentilhomme, Y. Neveux, Markers of epidermal proliferation and differentiation, in Agache’s Measuring the Skin, P. Humbert, F. Fanian, H. Maibach, P. Agache, Eds. (Springer International Publishing, 2017), pp. 397–405. [Google Scholar]

- 4.E. M. Novoa, C. E. Mason, J. S. Mattick, Charting the unknown epitranscriptome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 339–340 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.C. J. Lewis, T. Pan, A. Kalsotra, RNA modifications and structures cooperate to guide RNA-protein interactions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 202–210 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.J. Liu, K. Li, J. Cai, M. Zhang, X. Zhang, X. Xiong, H. Meng, X. Xu, Z. Huang, J. Peng, J. Fan, C. Yi, Landscape and regulation of m6A and m6Am methylome across human and mouse tissues. Mol. Cell 77, 426–440.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.R. J. Ries, S. Zaccara, P. Klein, A. Olarerin-George, S. Namkoong, B. F. Pickering, D. P. Patil, H. Kwak, J. H. Lee, S. R. Jaffrey, m6A enhances the phase separation potential of mRNA. Nature 571, 424–428 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.S. Lin, J. Choe, P. Du, R. Triboulet, R. I. Gregory, The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes translation in human cancer cells. Mol. Cell 62, 335–345 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.B. Slobodin, R. Han, V. Calderone, J. A. F. O. Vrielink, F. Loayza-Puch, R. Elkon, R. Agami, Transcription impacts the efficiency of mRNA translation via co-transcriptional N6-adenosine methylation. Cell 169, 326–337.e12 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.J. Zhou, J. Wan, X. E. Shu, Y. Mao, X. M. Liu, X. Yuan, X. Zhang, M. E. Hess, J. C. Brüning, S. B. Qian, N6-Methyladenosine guides mRNA alternative translation during integrated stress response. Mol. Cell 69, 636–647.e7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.P. J. Batista, B. Molinie, J. Wang, K. Qu, J. Zhang, L. Li, D. M. Bouley, E. Lujan, B. Haddad, K. Daneshvar, A. C. Carter, R. A. Flynn, C. Zhou, K. S. Lim, P. Dedon, M. Wernig, A. C. Mullen, Y. Xing, C. C. Giallourakis, H. Y. Chang, m6A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 15, 707–719 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.B. S. Zhao, I. A. Roundtree, C. He, Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 31–42 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.H. B. Li, J. Tong, S. Zhu, P. J. Batista, E. E. Duffy, J. Zhao, W. Bailis, G. Cao, L. Kroehling, Y. Chen, G. Wang, J. P. Broughton, Y. G. Chen, Y. Kluger, M. D. Simon, H. Y. Chang, Z. Yin, R. A. Flavell, m6A mRNA methylation controls T cell homeostasis by targeting the IL-7/STAT5/SOCS pathways. Nature 548, 338–342 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.I. Barbieri, K. Tzelepis, L. Pandolfini, J. Shi, G. Millán-Zambrano, S. C. Robson, D. Aspris, V. Migliori, A. J. Bannister, N. Han, E. de Braekeleer, H. Ponstingl, A. Hendrick, C. R. Vakoc, G. S. Vassiliou, T. Kouzarides, Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by m6A-dependent translation control. Nature 552, 126–131 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.R. Zhou, Y. Gao, D. Lv, C. Wang, D. Wang, Q. Li, METTL3 mediated m6A modification plays an oncogenic role in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma by regulating ΔNp63. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 515, 310–317 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.W. Zhao, Y. Cui, L. Liu, X. Ma, X. Qi, Y. Wang, Z. Liu, S. Ma, J. Liu, J. Wu, METTL3 facilitates oral squamous cell carcinoma tumorigenesis by enhancing c-myc stability via YTHDF1-mediated m6A modification. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 20, 1–12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Y. Wu, L. Xie, M. Wang, Q. Xiong, Y. Guo, Y. Liang, J. Li, R. Sheng, P. Deng, Y. Wang, R. Zheng, Y. Jiang, L. Ye, Q. Chen, X. Zhou, S. Lin, Q. Yuan, Mettl3-mediated m6A RNA methylation regulates the fate of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and osteoporosis. Nat. Commun. 9, 4772 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.R. Paus, Principles of hair cycle control. J. Dermatol. 25, 793–802 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.E. Fuchs, B. J. Merrill, C. Jamora, R. DasGupta, At the roots of a never-ending cycle. Dev. Cell 1, 13–25 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.M. V. Plikus, C. M. Chuong, Complex hair cycle domain patterns and regenerative hair waves in living rodents. J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 1071–1080 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.M. Watanabe, K. Natsuga, W. Nishie, Y. Kobayashi, G. Donati, S. Suzuki, Y. Fujimura, T. Tsukiyama, H. Ujiie, S. Shinkuma, H. Nakamura, M. Murakami, M. Ozaki, M. Nagayama, F. M. Watt, H. Shimizu, Type XVII collagen coordinates proliferation in the interfollicular epidermis. eLife 6, e26635 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.L. Xi, T. Carroll, I. Matos, J. D. Luo, L. Polak, H. A. Pasolli, S. R. Jaffrey, E. Fuchs, m6A RNA methylation impacts fate choices during skin morphogenesis. eLife 9, e56980 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.L. Su, P. R. Morgan, J. A. Thomas, E. B. Lane, Expression of keratin 14 and 19 mRNA and protein in normal oral epithelia, hairy leukoplakia, tongue biting and white sponge nevus. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 22, 183–189 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Q. Xiong, C. Liu, X. Zheng, X. Zhou, K. Lei, X. Zhang, Q. Wang, W. Lin, R. Tong, R. Xu, Q. Yuan, METTL3-mediated m6A RNA methylation regulates dorsal lingual epithelium homeostasis. Int. J. Oral Sci. 14, 26 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R. L. Kan, J. Chen, T. Sallam, Crosstalk between epitranscriptomic and epigenetic mechanisms in gene regulation. Trends Genet. 38, 182–193 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.A. S. Hopkin, W. Gordon, R. H. Klein, F. Espitia, K. Daily, M. Zeller, P. Baldi, B. Andersen, GRHL3/GET1 and trithorax group members collaborate to activate the epidermal progenitor differentiation program. PLOS Genet. 8, e1002829 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.S. Egolf, J. Zou, A. Anderson, C. L. Simpson, Y. Aubert, S. Prouty, K. Ge, J. T. Seykora, B. C. Capell, MLL4 mediates differentiation and tumor suppression through ferroptosis. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj9141 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.S. Egolf, Y. Aubert, M. Doepner, A. Anderson, A. Maldonado-Lopez, G. Pacella, J. Lee, E. K. Ko, J. Zou, Y. Lan, C. L. Simpson, T. Ridky, B. C. Capell, LSD1 inhibition promotes epithelial differentiation through derepression of fate-determining transcription factors. Cell Rep. 28, 1981–1992.e7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.K. Natsuga, M. Watanabe, W. Nishie, H. Shimizu, Life before and beyond blistering: The role of collagen XVII in epidermal physiology. Exp. Dermatol. 28, 1135–1141 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.T. J. Sproule, J. A. Bubier, F. C. Grandi, V. Z. Sun, V. M. Philip, C. G. McPhee, E. B. Adkins, J. P. Sundberg, D. C. Roopenian, Molecular identification of collagen 17a1 as a major genetic modifier of laminin gamma 2 mutation-induced junctional epidermolysis bullosa in mice. PLOS Genet. 10, e1004068 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.J. Hoffmann, F. Casetti, A. Reimer, J. Leppert, G. Grüninger, C. Has, A silent COL17A1 variant alters splicing and causes junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Acta Derm. Venereol. 99, 460–461 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.H. H. Xu, V. P. Werth, E. Parisi, T. P. Sollecito, Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 57, 611–630 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.M. Ratnadiwakara, M. L. Anko, mRNA stability assay using transcription inhibition by actinomycin D in mouse pluripotent stem cells. Bio Protoc. 8, e3072 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.C. Y. Chen, N. Ezzeddine, A. B. Shyu, Messenger RNA half-life measurements in mammalian cells. Methods Enzymol. 448, 335–357 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.A. S. Bledau, K. Schmidt, K. Neumann, U. Hill, G. Ciotta, A. Gupta, D. C. Torres, J. Fu, A. Kranz, A. F. Stewart, K. Anastassiadis, The H3K4 methyltransferase Setd1a is first required at the epiblast stage, whereas Setd1b becomes essential after gastrulation. Development 141, 1022–1035 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.N. D. Heintzman, G. C. Hon, R. D. Hawkins, P. Kheradpour, A. Stark, L. F. Harp, Z. Ye, L. K. Lee, R. K. Stuart, C. W. Ching, K. A. Ching, J. E. Antosiewicz-Bourget, H. Liu, X. Zhang, R. D. Green, V. V. Lobanenkov, R. Stewart, J. A. Thomson, G. E. Crawford, M. Kellis, B. Ren, Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global cell-type-specific gene expression. Nature 459, 108–112 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.A. Kranz, K. Anastassiadis, The role of SETD1A and SETD1B in development and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 1863, 194578 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.E. Lin-Shiao, Y. Lan, M. Coradin, A. Anderson, G. Donahue, C. L. Simpson, P. Sen, R. Saffie, L. Busino, B. A. Garcia, S. L. Berger, B. C. Capell, KMT2D regulates p63 target enhancers to coordinate epithelial homeostasis. Genes Dev. 32, 181–193 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.S. Murakami, S. R. Jaffrey, Hidden codes in mRNA: Control of gene expression by m6A. Mol. Cell 82, 2236–2251 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.S. Zaccara, S. R. Jaffrey, A unified model for the function of YTHDF proteins in regulating m6A-modified mRNA. Cell 181, 1582–1595.e18 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Y. Wang, Y. Li, M. Yue, J. Wang, S. Kumar, R. J. Wechsler-Reya, Z. Zhang, Y. Ogawa, M. Kellis, G. Duester, J. C. Zhao, N6-methyladenosine RNA modification regulates embryonic neural stem cell self-renewal through histone modifications. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 195–206 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.C. Wu, W. Chen, J. He, S. Jin, Y. Liu, Y. Yi, Z. Gao, J. Yang, J. Yang, J. Cui, W. Zhao, Interplay of m6A and H3K27 trimethylation restrains inflammation during bacterial infection. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba0647 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Y. Li, L. Xia, K. Tan, X. Ye, Z. Zuo, M. Li, R. Xiao, Z. Wang, X. Liu, M. Deng, J. Cui, M. Yang, Q. Luo, S. Liu, X. Cao, H. Zhu, T. Liu, J. Hu, J. Shi, S. Xiao, L. Xia, N6-Methyladenosine co-transcriptionally directs the demethylation of histone H3K9me2. Nat. Genet. 52, 870–877 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.A. Maldonado Lopez, B. C. Capell, The METTL3-m6A epitranscriptome: Dynamic regulator of epithelial development, differentiation, and cancer. Genes (Basel) 12, 1019 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.E. Yankova, W. Blackaby, M. Albertella, J. Rak, E. de Braekeleer, G. Tsagkogeorga, E. S. Pilka, D. Aspris, D. Leggate, A. G. Hendrick, N. A. Webster, B. Andrews, R. Fosbeary, P. Guest, N. Irigoyen, M. Eleftheriou, M. Gozdecka, J. M. L. Dias, A. J. Bannister, B. Vick, I. Jeremias, G. S. Vassiliou, O. Rausch, K. Tzelepis, T. Kouzarides, Small-molecule inhibition of METTL3 as a strategy against myeloid leukaemia. Nature 593, 597–601 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.M. Berdasco, M. Esteller, Towards a druggable epitranscriptome: Compounds that target RNA modifications in cancer. Br. J. Pharmacol. 179, 2868–2889 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.R. J. Ontiveros, H. Shen, J. Stoute, A. Yanas, Y. Cui, Y. Zhang, K. F. Liu, Coordination of mRNA and tRNA methylations by TRMT10A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 7782–7791 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.G. Eraslan, E. Drokhlyansky, S. Anand, E. Fiskin, A. Subramanian, M. Slyper, J. Wang, N. van Wittenberghe, J. M. Rouhana, J. Waldman, O. Ashenberg, M. Lek, D. Dionne, T. S. Win, M. S. Cuoco, O. Kuksenko, A. M. Tsankov, P. A. Branton, J. L. Marshall, A. Greka, G. Getz, A. V. Segrè, F. Aguet, O. Rozenblatt-Rosen, K. G. Ardlie, A. Regev, Single-nucleus cross-tissue molecular reference maps toward understanding disease gene function. Science 376, eabl4290 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.R. Ruiz-Vega, C. F. Chen, E. Razzak, P. Vasudeva, T. B. Krasieva, J. Shiu, M. G. Caldwell, H. Yan, J. Lowengrub, A. K. Ganesan, A. D. Lander, Dynamics of nevus development implicate cell cooperation in the growth arrest of transformed melanocytes. eLife 9, e61026 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.P. L. Germain, A. Lun, C. Garcia Meixide, W. Macnair, M. D. Robinson, Doublet identification in single-cell sequencing data using scDblFinder. F1000Res 10, 979 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.I. Korsunsky, N. Millard, J. Fan, K. Slowikowski, F. Zhang, K. Wei, Y. Baglaenko, M. Brenner, P. R. Loh, S. Raychaudhuri, Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat. Methods 16, 1289–1296 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.M. I. Love, W. Huber, S. Anders, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.A. Dobin, C. A. Davis, F. Schlesinger, J. Drenkow, C. Zaleski, S. Jha, P. Batut, M. Chaisson, T. R. Gingeras, STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S6

Data S1 and S2