Abstract

Borrelia burgdorferi-induced arthritis in mice is characterized by tendonitis, synovitis, and inflammatory-cell infiltrate, predominantly of neutrophils. Because genetic deficiency in E and P selectins results in delayed recruitment of neutrophils to sites of inflammation, mice with this deficiency were tested for their response to infection with B. burgdorferi. E and P selectins were not required for the control of B. burgdorferi numbers, nor did deficiency in E and P selectins result in alteration of arthritis severity.

Arthritis can develop in humans and in certain inbred mice upon infection with the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi (1, 11). The murine model of Lyme disease has been extensively studied, but the mechanism of arthritis development remains unknown. In the murine model, C3H/He mice develop severe arthritis when infected with B. burgdorferi. This arthritis is reminiscent of human Lyme arthritis, with edema, infiltration of neutrophils, and the hyperproliferation of the synovial membranes within the joint (3). Ankles taken from infected mice exhibiting severe Lyme arthritis show the presence of high numbers of spirochetes in the joints by PCR analysis (9, 19).

In contrast to the severe arthritis seen in C3H/He mice, B. burgdorferi-infected BALB/cAN and C57BL/6N mice develop mild to moderate arthritis (1). The pathology in the joints of these animals shows mild edema and proliferation of synovial membranes, with fewer infiltrating neutrophils. Infected BALB/cAN mice show low numbers of spirochetes in tissues by PCR, whereas C57BL/6N mice show high numbers of spirochetes in the joint but low numbers in the heart (9). Interestingly, the mechanisms of resistance to severe arthritis are different in these two strains of mice; the resistance of BALB/cAN mice can be overcome by a high infectious dose of B. burgdorferi, whereas C57BL/6N mice are resistant to a very high infectious challenge (9). Severe arthritis in C3H/He mice infected with B. burgdorferi is characterized by tendonitis, synovitis, and neutrophil influx into joint tissues. The mild arthritis seen in resistant mice displays little synovial hyperproliferation and tendonitis, with little evidence of neutrophil infiltration. We have observed a consistent correlation between high neutrophil influx into joint tissues and histopathologically severe arthritis.

The induction of chemokines and adhesion molecule upregulation on both endothelial and infiltrating cells is required for the infiltration of inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils, into tissues (15). Outer-surface components of B. burgdorferi have been documented to upregulate both chemokine and adhesion molecule expression on inflammatory cells (4, 5, 12–14, 18). Neutrophil degranulation is induced by stimulation with B. burgdorferi lipoproteins in vitro as well (10). This study was designed to determine the role of the adhesion molecules E selectin and P selectin in the development of murine Lyme arthritis and their role in the control of spirochete persistence in tissues. To this end, we utilized a strain of mouse in which the genes encoding the E and P selectin molecules were disrupted by homologous recombination (8). These mice previously were shown to have delayed neutrophil extravasation in thioglycolate-induced peritonitis and cytokine-induced meningitis (8, 17).

Male mice homozygous for the E and P selectin deficiency were bred in the Center for Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Both wild-type controls and E and P selectin double-deficient mice were descendants of F2 intercrosses between 129sv and C57BL/6 strains. Intercross populations of 129sv × C57BL/6 and 129sv × Black Swiss mice have been found to resist severe Lyme arthritis in other studies (6, 7), suggesting that the 129sv mouse is arthritis resistant, like the C57BL/6 mouse. Male C3H/HeJNCr and C57BL/6NCr mice were obtained from the National Cancer Institute. Mice were infected with 2 × 103 B. burgdorferi organisms (N40 strain) by intradermal injection into the shaven back or were mock infected by injection of an equivalent volume of sterile BSK-H medium (9). Four to five mice from each experimental group were sacrificed at 2 weeks postinfection, and the remainder were sacrificed at 4 weeks postinfection. At the time of sacrifice, multiple tissues were taken for culture (blood, ear, and spleen), histological analysis (rear ankle joint), or isolation of DNA for determination of spirochete levels (rear ankle joint, heart, ear, urinary bladder, and brain), as previously described (9).

All tissues taken for culture were incubated in BSK-H medium containing 6% rabbit serum, 100 mg of phosphomycin/ml, and 50 mg of rifampin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)/ml for up to 14 days at 32°C. Tissues taken from mock-infected animals had no spirochetes present in any tissue cultured. All ear cultures from infected mice contained spirochetes, confirming that 100% of the mice injected with B. burgdorferi were infected. Although culture positivity among blood or spleen cultures from infected mice was variable, differences were not noted between the different mouse strains.

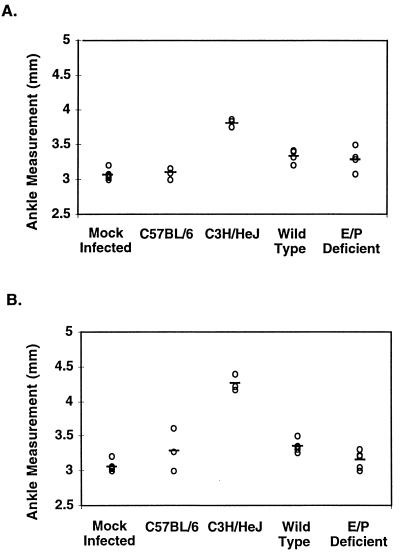

At the time of sacrifice, both rear ankle joints from each mouse were measured for swelling with metric calipers as previously described (9). Figure 1 shows the average rear ankle swelling for each group of animals. C3H/HeJNCr mice had severe ankle swelling at both 2 and 4 weeks postinfection, while C57BL/6NCr mice showed little to no swelling at both time points. Infected E and P selectin-deficient mice and their wild-type littermates showed very little swelling at either 2 or 4 weeks postinfection. Based on these data, the E and P selectin-deficient mice and their wild-type littermates displayed an arthritis-resistant phenotype. Others have also observed that 129Sv × C57BL/6 mice are resistant to severe arthritis development during infection with B. burgdorferi (7). In this case, the lack of E and P selectin molecules did not result in increased ankle swelling upon infection with B. burgdorferi.

FIG. 1.

Effect of E and P selectin deficiency on ankle swelling in mice infected with B. burgdorferi. Rear ankle joints were measured in mice at 2 (A) and 4 (B) weeks following infection, and the measurement of the most severely swollen rear ankle joint from each mouse is indicated on the graph. Mock-infected mice include C3H/HeJ mice, E and P selectin-deficient mice, and wild-type controls.

The rear ankle joint displaying the greatest degree of swelling was taken for histological analysis. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of the joint were examined microscopically and assigned scores from 0 to 4+, as previously described (9). The examiner was not aware of the identity of the experimental group from which the sections were taken. Histological analysis revealed severe pathology in infected C3H/HeJ mice (3+ to 4+) and mild to moderate pathology in C57BL/6N mice (1+ to 2+), as previously reported (9).

A range of pathology was noted in ankle sections from infected E and P selectin-deficient mice and wild-type littermates (0 to 2+). Significant alteration in joints was not noted until 4 weeks postinfection, at which point pathology ranged from zero to moderate inflammation, as assessed by degree of proliferation of synovial membranes, edema, and neutrophil influx. Interestingly, synovial thickening and edema were always associated with the presence of neutrophils in joint tissues. Thus, the defect in neutrophil extravasation into tissues in the E and P selectin-deficient mice appeared to be overcome by 2 to 4 weeks following infection with B. burgdorferi. This is consistent with recent studies by others in a model of wound healing, in which the defect in neutrophil extravasation in E and P selectin-deficient mice was most apparent at early time points. By 3 days following the trauma, neutrophils were present at one-third the numbers found in wild-type mice, suggesting that alternative adhesion mechanisms were allowing neutrophil influx into tissues (16). The similar ranges of pathology seen in E and P selectin-deficient mice and wild-type mice indicate that the absence of the E and P selectin molecules in vivo does not significantly affect the outcome of arthritis during infection with B. burgdorferi. Additionally, the histological sections supported the ankle swelling measurements, indicating that E and P selectin-deficient mice and the wild-type controls mice show an arthritis-resistant phenotype when infected with B. burgdorferi.

To assess the role of E and P selectins in clearance of tissue spirochetes during infection with B. burgdorferi, DNA was isolated from various tissues of mice for PCR determination of spirochete levels. Five tissues were harvested for PCR analysis: one ear, one rear ankle joint, the heart, the urinary bladder, and the brain. Primers and conditions used in PCR analysis were as previously published (9). A standard curve containing known numbers of B. burgdorferi organisms was run with each set of samples, allowing an estimation of the number of B. burgdorferi organisms in infected tissues for comparison purposes. Samples were subjected to PCR, run on polyacrylamide gels, and subjected to PhosphorImager analysis for quantification.

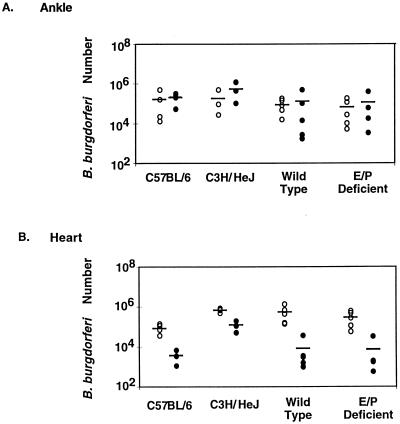

C3H/HeJNCr and C57BL/6N mice had similar levels of spirochetes in rear ankle joints at 2 and 4 weeks following infection (Fig. 2). Higher levels of spirochetes were found in hearts from C3H/HeJNCr mice than in hearts from C57BL/6N mice at both time points, as previously reported for 4 weeks postinfection (9). The 129Sv × C57BL/6 wild-type mice harbored levels of spirochetes very similar to those found in the inbred C57BL/6N mice for all tissues tested. The deficiency in E and P selectins had no detectable effect on spirochete levels in hearts and joints (Fig. 2). Similar results were obtained for the other tissues analyzed by PCR: no increase in spirochete levels was attributed to deficiency in E and P selectins.

FIG. 2.

Effect of E and P selectin deficiency on spirochete levels in ankle joints and hearts. Ankle joints (A) and hearts (B) were collected from mice 2 weeks (open circles) or 4 weeks (closed circles) following infection, as indicated. Spirochete levels were determined by linear range PCR, with standard curves of known B. burgdorferi numbers included on each gel. Circles represent results from individual mice, and bars represent the average value for each group. Values for E and P selectin-deficient mice were not significantly different from values for wild-type controls at either time point, in either tissue (P > 0.05).

The finding that E and P selectin deficiency did not result in higher levels of tissue spirochetes was somewhat surprising. We had hypothesized that defective neutrophil extravasation into tissues at any point during infection could result in increased numbers of spirochetes in tissues. The importance of neutrophils in the control of B. burgdorferi infection in vivo has been inferred from studies of mice with the beige mutation (2). These mice, with defective granule function in several cell types, develop more severe arthritis than congenic C57BL/6 mice. Because depletion of NK cells in the infected beige mice had no further effects on arthritis outcome or spirochete numbers, neutrophils were concluded to be essential for the control of spirochete proliferation in vivo. Our results indicate that a defect which reduces early neutrophil extravasation does not alter the outcome of arthritis, nor does it alter the numbers of spirochetes present in tissues at later times postinfection.

The observations that E and P selectin-deficient mice exhibit a Lyme arthritis-resistant phenotype and do not display altered numbers of spirochetes in tissues suggest that the adhesion molecules E selectin and P selectin are not required for resistance to severe Lyme arthritis. E and P selectins also are not required for effective control of B. burgdorferi in tissues. Because intercross populations of E and P selectin-deficient mice and wild-type littermates were used, we cannot say that the only genetic difference between these mice was in the E and P selectin genes. However, as both parental strains of the intercross are resistant to severe arthritis, and no difference was seen in arthritis severity between E and P selectin-deficient and wild-type littermates, it is likely that these adhesion molecules are not required for arthritis resistance.

It should also be noted that other pathways of neutrophil extravasation become important after several hours of inflammation, and these may override the importance of E and P selectins in persistent infection with B. burgdorferi (8, 17). In fact, neutrophil influx into the joints of infected mice strongly correlated with the development of arthritis in these experiments. It is possible that E and P selectins play a more active role in neutrophil recruitment in mice genetically susceptible to B. burgdorferi-induced arthritis; however, these deficiencies are not available on such backgrounds. Although E and P selectins do not appear to play a critical role in host defense or arthritis development, further study will be required to determine exactly the role of neutrophils in infection with B. burgdorferi.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI-32223 and AI-43521 (to J.J.W.), AI-24158 (to J.H.W.), HL-53756 (to D.D.W.), and HL-41484 (to R.O.H.). R.O.H. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The project described was also supported in part by an award from the American Lung Association (J.H.W.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barthold S W, Beck D S, Hansen G M, Terwilliger G A, Moody K D. Lyme borreliosis in selected strains and ages of laboratory mice. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:133–138. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barthold S W, de Souza M. Exacerbation of Lyme arthritis in beige mice. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:778–784. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.3.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barthold S W, Persing D H, Armstrong A L, Peeples R A. Kinetics of Borrelia burgdorferi dissemination and evolution of disease after intradermal inoculation of mice. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:263–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boggemeyer E, Stehle T, Schaible U E, Hahne M, Vestweber D, Simon M M. Borrelia burgdorferi upregulates the adhesion molecules E-selectin, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on mouse endothelioma cells in vitro. Cell Adhesion Commun. 1994;2:145–157. doi: 10.3109/15419069409004433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns M J, Sellati T J, Teng E I, Furie M B. Production of interleukin-8 (IL-8) by cultured endothelial cells in response to Borrelia burgdorferi occurs independently of secretion [sic] IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha and is required for subsequent transendothelial migration of neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1217–1222. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1217-1222.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman J L, Gebbia J A, Piesman J, Degen J L, Bugge T H, Benach J L. Plasminogen is required for efficient dissemination of B. burgdorferi in ticks and for enhancement of spirochetemia in mice. Cell. 1997;89:1111–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fikrig E, Barthold S W, Chen M, Grewal I S, Craft J, Flavell R A. Protective antibodies in murine Lyme disease arise independently of CD40 ligand. J Immunol. 1996;157:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frenette P S, Mayadas T N, Rayburn H, Hynes R O, Wagner D D. Susceptibility to infection and altered hematopoiesis in mice deficient in both P- and E-selectins. Cell. 1996;84:563–574. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma Y, Seiler K P, Eichwald E J, Weis J H, Teuscher C, Weis J J. Distinct characteristics of resistance to Borrelia burgdorferi-induced arthritis in C57BL/6N mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:161–168. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.161-168.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison T B, Weis J H, Weis J J. Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein A (OspA) activates and primes human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1997;158:4838–4845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nocton J J, Steere A C. Lyme disease. Adv Intern Med. 1995;40:69–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaible U E, Vestweber D, Butcher E G, Stehle T, Simon M M. Expression of endothelial cell adhesion molecules in joints and heart during Borrelia burgdorferi infection of mice. Cell Adhesion Commun. 1994;2:465–479. doi: 10.3109/15419069409014211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sellati T J, Abrescia L D, Radolf J D, Furie M B. Outer surface lipoproteins of Borrelia burgdorferi activate vascular endothelium in vitro. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3180–3187. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3180-3187.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sellati T J, Burns M J, Ficazzola M A, Furie M B. Borrelia burgdorferi upregulates expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells and promotes transendothelial migration of neutrophils in vitro. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4439–4447. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4439-4447.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Springer T A. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subramaniam M, Saffaripour S, Van De Water L, Frenette P S, Mayadas T N, Hynes R O, Wagner D D. Role of endothelial selectins in wound repair. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1701–1709. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang T, Frenette P S, Hynes R O, Wagner D D, Mayadas T N. Cytokine-induced meningitis is dramatically attenuated in mice deficient in endothelial selectins. J Clin Investig. 1996;97:2485–2490. doi: 10.1172/JCI118695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wooten R M, Modur V R, McIntyre T M, Weis J J. Borrelia burgdorferi outer membrane protein A induces nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-κB and inflammatory activation in human endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1996;157:4584–4590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang L, Weis J H, Eichwald E, Kolbert C P, Persing D H, Weis J J. Heritable susceptibility to severe Borrelia burgdorferi-induced arthritis is dominant and is associated with persistence of large numbers of spirochetes in tissues. Infect Immun. 1994;62:492–500. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.492-500.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]