Abstract

Vitex L. is the largest genus of the Lamiaceae family, and most of its species are used in the traditional medicinal systems of different countries. A systematic review was conducted, according to the PRISMA methodology, to determine the potential of Vitex plants as sources of antimicrobial agents, resulting in 2610 scientific publications from which 141 articles were selected. Data analysis confirmed that Vitex species are used in traditional medicine for symptoms of possible infectious diseases. Conducted studies showed that these medicinal plants exhibited in vitro antimicrobial activity against Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus. Vitex agnus-castus L. and Vitex negundo L. have been the most studied species, not only against bacterial strains but also against fungi such as Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans, viruses such as HIV-1, and parasites such as Plasmodium falciparum. Natural products like agnucastoside, negundol, negundoside, and vitegnoside have been identified in Vitex extracts and their antimicrobial activity against a wide range of microbial strains has been determined. Negundoside showed significant antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus (MIC 12.5 µg/mL). Our results show that Vitex species are potential sources of new natural antimicrobial agents. However, further experimental studies need to be conducted.

Keywords: antimicrobial drug, herbal medicine, medicinal plant, traditional medicine, Vitex

1. Introduction

Bacterial resistance to clinically available antibiotics is a global phenomenon whose impact has increased significantly in recent years. Multidrug-resistant infections are a very common problem, greatly affecting mortality and morbidity in populations around the world and leading to greatly increased economic burdens. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates that the increase in multidrug-resistant bacterial infections will result in a total expense of approximately USD 20 to USD 35 trillion by 2050 [1,2]. Resistance mechanisms developed by bacteria to circumvent the effects of antibiotics are very diverse. Enzyme-based bacterial processes can directly inactivate antibiotics; efflux pumps can expel antibiotics from inside bacterial cells, reducing their concentration to subtoxic levels; mechanistic bacterial targets of antibiotics, such as ribosome subunits, DNA gyrase or RNA polymerase, can undergo conformational changes that prevent drugs from binding to them. Such mutations can be either spontaneous or adaptive, and some of them can undergo horizontal gene transfer, which can eventually lead to new naturally resistant bacteria. For example, Staphylococcus aureus, one of the most common etiological agents of infections in hospital and non-hospital contexts, shows a huge increase in resistance patterns to antibiotics of different classes, which means that this species can develop different resistance mechanisms to available drugs [2,3]. Medicinal plants have long been used in several traditional healing systems to treat many infectious symptoms and infectious diseases. Studies have shown that plant extracts (and/or natural products isolated from them) not only exert antimicrobial activity against various bacteria but can also modulate bacterial resistance mechanisms and increase the activity of concurrently administered antibiotics, or, in some cases, even reverse established resistance mechanisms. For example, several flavonoids, which constitute one of the most common classes of natural products, have demonstrated the ability to reverse bacterial multidrug resistance by inhibiting efflux pumps [4,5]. Research has shown that many plants’ secondary metabolites can exhibit antimicrobial activity, which can be exerted through a wide variety of mechanisms. Plants thus serve as direct antimicrobial agents and reservoirs of diverse bioactive compounds capable of inhibiting the growth and spread of harmful microorganisms. Vitex L., also known as the chaste tree genus, is the largest genus in the family Lamiaceae and comprises about 230 species distributed worldwide [6]. Most Vitex species are deciduous shrubs or small trees [7]. These species are scattered and mostly distributed in temperate regions of Asia and warm regions of Europe, being substantially distributed through Southeast Asia [8,9]. However, most species that belong to this genus are used in traditional medicine in southwest Asian countries like India, China, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Malaysia, and other countries, namely Indonesia, Egypt, Iran, Morocco, Brazil, and Mexico. In India, Vitex agnus-castus L., Vitex negundo L., Vitex peduncularis W., Vitex pinnata L., and Vitex trifolia L. are frequently found throughout the country [10]. Vitex species are well recognized as sources of useful medicines in different geographic areas and have already been the subject of different research studies, mainly referring to V. agnus-castus and V. negundo [11].

Traditionally, Vitex plants have long been used for different types of treatment of menstrual disorders, fertility problems, menopausal symptoms, diarrhea, asthma, fever, cold, headache, migraine, gastrointestinal infections, and breast pain [12,13]. Recent studies have revealed that this genus has a wide range of biological properties, especially antimicrobial activities [14]. It has been utilized in various traditional medicinal systems around the world to address health concerns beyond its antimicrobial applications. Traditional practitioners usually prepare herbal medicines to treat and prevent diseases [15]. They use plant parts of Vitex species for the treatment of various infectious diseases such as bacterial, viral, and protozoal infections [16]. Several studies have examined the antimicrobial properties of Vitex L., and the results have shown that different parts of Vitex such as the leaf, bark, root, stem, flower, fruit, and seed exhibit antimicrobial activity against a wide range of microorganisms. Phytochemical analysis of the Vitex species has found several previously known compounds, mainly terpenoids, flavonoids, and alkaloids. This review has explored the potential antibacterial effects of Vitex extracts and their isolated natural products [17].

Herein, a concise and original review of the literature concerning the ethnomedicinal use of medicinal plants from the Vitex genus and their potential, as both antimicrobial herbal medicines as well as sources of new antimicrobial natural products, was made. This state-of-the-art paper will provide a comprehensive understanding of the potential of this genus as a source of antimicrobial agents.

2. Results

2.1. Selection of the Information

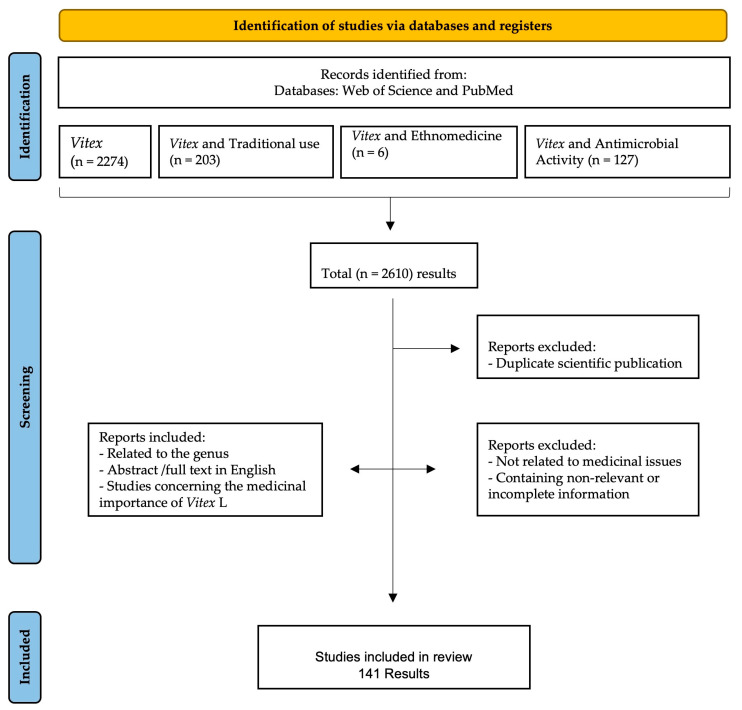

Details of data collection and selection are given in Figure 1. The initial title and abstract search yielded 2610 results. Of those, 2610 scientific publications were considered, and many articles were removed for the following reasons: repeated results, no relation to medicinal issues, and the inclusion of irrelevant or incomplete information. Finally, a total of 141 scientific publications were considered eligible to be included in this review as they were related to the use of Vitex species in traditional medicine, were abstracts or full texts written in English, and the studies conducted focused on the Vitex species and their antimicrobial activity against different microorganisms.

Figure 1.

Data screening based on PRISMA methodology.

2.2. Traditional Uses

Obtained results concerning the traditional use of the Vitex species are summarized in Table 1 and classified according to the symptoms they were used against (Figure 2). From the recognized 230 species of Vitex, only 13 species have been reported as being used in traditional medicine, namely Vitex agnus-castus L., Vitex doniana L., Vitex gardneriana Schauer., Vitex mollis L. Vitex negundo L., Vitex obovata ssp. wilmsii (Gürke) Bredenkamp & Botha, Vitex peduncularis W., Vitex peduncularis L., Vitex pinnata L., Vitex polygama L., Vitex pseudo-negundo L., Vitex rehmannii sp., Vitex rotundifolia L., and Vitex trifolia L. These species are traditionally used for the treatment of menstrual disorders and hormonal imbalance, increasing breast milk production, and hypertension [18,19,20,21]. Vitex species are also used for infectious diseases treatment such as cavity infections, dysentery, diarrhea, asthma, cholera, and malaria [22,23,24,25,26]. The leaf of Vitex is the most frequently used plant part for medicinal purposes, but other parts like the bark, root, and flower are also referred to in the literature.

Table 1.

Ethnomedicinal use of Vitex species.

| Species | Part Used | Country | Signals or Symptoms or Pathology | Bib. References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V. agnus-castus | L | Iran | increasing breast milk | [18] |

| F | Turkey | corpus luteum insufficiency, hyperprolactinemia, infertility, menstrual disorders, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, menopause disrupted lactation, cyclical gastralgia | [19,20] | |

| L | Brazil | oral disorders; diuretic, antiseptic, digestive, antifungal, anti-anxiety, aphrodisiac, anti-estrus, emmenagogus, antispasmodic, aperitif, and analgesic properties | [22] | |

| L | Brazil | menstrual disorder | [27] | |

| V. doniana | Sb | Nigeria | decoction, gastroenteritis, diarrhea, dysentery | [25] |

| V. gardneriana | L | Brazil | analgesic pain, anti-inflammatory properties | [28] |

| V. mollis | L | Mexico | dysentery, analgesic, anti-inflammatory properties, scorpion stings, diarrhea, stomachache | [29] |

| V. negundo | S, F | India | increasing lactation | [30,31] |

| L | India | post-partum bath | [30,31] | |

| R, B, Fl | India | diarrhea, dysentery, flatulence, indigestion, cholera | [24,32] | |

| L | Maldives | fever | [33] | |

| L | Bangladesh, India, Malaysia | headache | [26,34] | |

| L | China, India, Nepal | cough, sore throat | [35,36,37] | |

| R, L | India | rheumatism | [38] | |

| L | India | hives, cellulitis, carbuncle | [39] | |

| L | India | fever, hearing problems | [24,40] | |

| Fl | Philippines | cancer | [41] | |

| L | Bangladesh | chronic disease, infectious diseases | [42] | |

| L | India | paralysis | [43] | |

| L | China | skin disease | [44] | |

| L | China | coughs, phlegm, asthma | [45] | |

| L | Pakistan | antiallergic properties | [46] | |

| R, Wp | Bangladesh | malaria, fever | [26] | |

| L | China and India | stomachic, antiseptic, depurative, and rejuvenating properties; eye problems; gonorrhea | [47] | |

| L | Bangladesh | diarrhea, dysentery | [48] | |

| L, B | Nepal | jaundice, wounds, body ache, toothache, asthma, eye problems | [49] | |

| V. obovata | L | South Africa | body pain | [50] |

| V. peduncularis | Wp | India | wounds, dysentery, stomach diseases, fever, hypertension | [51] |

| B, L | Bangladesh | joint ache, diabetes | [26] | |

| R | India | eye problems, skin problems, chest pain | [52] | |

| L | India | malaria, fever | [53] | |

| V. pinnata | Wp | Malaysia | hypertension, gastrointestinal disorders | [21] |

| L | Brunei | hypertension, fever | [16] | |

| L, B | Malaysia | fever, gastric ulcer | [54] | |

| Wp | Brunei | jaundice | [55] | |

| L | Brunei | sanitizing | [23] | |

| Wp | Malaysia | dysentery, inflammatory | [56] | |

| Wp | Indonesia | cancer, gastrointestinal disorder, fever, wound, skin tumor | [57] | |

| V. polygama | L, F | Brazil | emmenagogue and diuretic properties. | [58] |

| V. pseudo-negundo | L | Iran | hyperprolactinemia, hormonal imbalance syndromes, breast diseases, infertility | [59] |

| V. rehmannii | L | South Africa | stomach disease | [50] |

| V. rotundifolia | F | China | cold, headache | [60] |

| V. trifolia | L | India | liver disorders, rheumatic pains | [61] |

| L | India | ulcers | [62] | |

| L | Philippines | cough | [63] | |

| F | China | migraines, eye problems | [45] | |

| Fl | Bangladesh | fever, vomiting | [64] | |

| L | Fiji | coughs, gonorrhea, stomach pain | [64] | |

| L | Tongo | infections | [65] | |

| St, L | Madagascar | stomach pain | [66] | |

| Fl | Thailand | asthma | [67] |

B—Bark; F—Fruit; Fl—Flower; L—Leaf; R—Root; Sb—Steambark; St—Steam; Wp—Whole plant.

Figure 2.

Symptoms of disease treated with Vitex plants.

In Figure 2, we can see the major symptoms that are treated with Vitex species, grouped according to the physiological systems impaired. Results showed that these species are mostly used by traditional medical practitioners as antimicrobial agents. Vitex plants are also used in inflammatory diseases, as analgesics, as hormonal regulators, and in infectious and non-infectious gastrointestinal diseases.

2.3. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity Studies

Reviewed articles were screened for information regarding plant species and corresponding origin, plant parts and solvents used for extract preparation, antimicrobial activity essay performed, bacteria species used to evaluate antimicrobial activity, and substances used as control. Results were expressed as minimum inhibitory concentrations, minimum bactericidal concentrations, and inhibition zones exhibited according to the type of essay performed. The gathered information is summarized in Table 2. Our analysis showed that different essays were used to study antimicrobial activity against a wide variety of bacterial species and strains. Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus were the most frequent subjects studied, mainly through disk diffusion and broth dilution methodology. Among the controls used in antimicrobial activity essays were known antibiotics like amoxicillin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, and gentamicin, and results showed that Vitex species plant extracts often exhibited significant activity against tested strains.

Table 2.

In vitro antibacterial activity studies on Vitex species.

| Species | Country | Plant Part Used | Extractive Solvent/Compound | Test Type | Strains | Positive Control | Results | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

V.

agnus-castus castus7 |

Iran | F | H2O | DDM |

Bacillus cereus PTCC 1015 Escherichia coli PTCC 1399 |

gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | IZ 5 mm | [68] |

| Iran | F | H2O | BDM | Escherichia coli PTCC 1399 | gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | MIC 25 µg/mL | [68] | |

| Iran | F | H2O | BDM | Bacillus cereus PTCC 1015 | gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | na | [68] | |

| Iran | F | H2O | BDM | Escherichia coli PTCC 1399 | gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | MIC 12 µg/mL | [68] | |

| Iran | F | H2O | BDM | Bacillus cereus PTCC 1015 | gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | MIC 25 µg/mL | [68] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | ADM | Agrobacterium tumefaciens * | na | MIC 575 mg/L | [69] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | ADM | Erwinia carotovora var. carotovora * | na | MIC 425 mg/L | [69] | |

| Brazil | L | EtOAc | BMicDM |

Streptococcus mutans ATCC 25175 Lactobacillus casei ATCC 11578 |

chlorhexidine dihydrochloride | MIC 15.6 µg/mL | [22] | |

| Brazil | L | EtOAc | BMicDM | Streptococcus mitis ATCC 49456 | chlorhexidine dihydrochloride | MIC 31.25 µg/mL | [22] | |

| Brazil | L | EtOAc | BMicDM | Streptococcus subrinus ATCC 33478 | chlorhexidine dihydrochloride | MIC 125 µg/mL | [22] | |

| Brazil | L | EtOAc | BMicDM | Streptococcus salivarius ATCC 25975 | chlorhexidine dihydrochloride | MIC 200 µg/mL | [22] | |

| Bulgaria | F | Et2O | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | na | IZ 11.25 ± 0.05 mm | [70] | |

| Bulgaria | F | Et2O | AWDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 | na | IZ 12.03 ± 0.02 mm | [70] | |

| Bulgaria | F | Et2O | AWDM | Kocuria rhizophila ATCC 9341 | na | IZ 9.37 ± 0.04 mm | [70] | |

| Bulgaria | F | Et2O | AWDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 8739 | na | IZ 8.00 ± 0.0 mm | [70] | |

| Bulgaria | F | Et2O | AWDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 9027 | na | IZ 8.03 ± 0.02 mm | [70] | |

| Bulgaria | F | Et2O | AWDM | Salmonella abony NCTC 6017 | na | IZ 11.15 ± 0.05 mm | [70] | |

| Bulgaria | F | Et2O | AWDM | Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATCC 2601 | na | IZ 11.86 ± 0.03 mm | [70] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6358 | chloramphenicol | IZ 30 mm | [71] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | DDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 | chloramphenicol | IZ 10 mm | [71] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | DDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 25923 | chloramphenicol | IZ 20 mm | [71] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | chloramphenicol | IZ 20 mm | [71] | |

| Turkey | Fl | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus 17 | ampicillin 10 µg and oxacillin 5 ug | IZ 18 mm | [72] | |

| Turkey | Fl | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus 18 | ampicillin 10 µg and oxacillin 5 ug | IZ 12 mm | [72] | |

| Turkey | Fl | EtOH | DDM | Coagulate negative Staphylococci 33 | ampicillin 10 µg and oxacillin 5 ug | IZ 8 mm | [72] | |

| Turkey | Fl | MeOH | DDM | Coagulate negative Staphylococci 33 | ampicillin 10 µg and oxacillin 5 ug | IZ 10 mm | [72] | |

| Turkey | Fl | EtOH | DDM | Coagulate negative Staphylococci 36 | ampicillin 10 µg and oxacillin 5 ug | IZ 9 mm | [72] | |

| Turkey | L | EtOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | gentamycin | IZ 7.5 mm | [73] | |

| Turkey | F | EtOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | gentamycin | IZ 10 mm | [73] | |

| Turkey | L | EtOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa * | gentamycin | IZ 9 mm | [73] | |

| Morocco | L | MeOH | BMicDM | Bacillus subtilis CIP 5262 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | R | MeOH | BMicDM | Bacillus subtilis CIP 5262 | chloramphenicol | MIC 31.25 µg/mL MBC 31.25 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | S | MeOH | BMicDM | Bacillus subtilis CIP 5262 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | Fl | MeOH | BMicDM | Bacillus subtilis CIP 5262 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 31.25 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | Se | MeOH | BMicDM | Bacillus subtilis CIP 5262 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | L | MeOH | BMicDM | Escherichia coli CIP 53126 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | R | MeOH | BMicDM | Escherichia coli CIP 53126 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | S | MeOH | BMicDM | Escherichia coli CIP 53126 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 31.25 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | Fl | MeOH | BMicDM | Escherichia coli CIP 53126 | chloramphenicol | MIC 31.25 µg/mL MBC 31.25 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | S | MeOH | BMicDM | Escherichia coli CIP 53126 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | L | MeOH | BMicDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa CIP 82118 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | R | MeOH | BMicDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa CIP 82118 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | S | MeOH | BMicDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa CIP 82118 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | Fl | MeOH | BMicDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa CIP 82118 | chloramphenicol | MIC 7.81 µg/mL MBC 7.81 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | Se | MeOH | BMicDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa CIP 82118 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | L | MeOH | BMicDM | Salmonella enterica CIP 8039 | chloramphenicol | MIC 7.81 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | R | MeOH | BMicDM | Salmonella enterica CIP 8039 | chloramphenicol | MIC 31.25 µg/mL MBC 31.25 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | S | MeOH | BMicDM | Salmonella enterica CIP 8039 | chloramphenicol | MIC 7.81 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | Fl | MeOH | BMicDM | Salmonella enterica CIP 8039 | chloramphenicol | MIC 7.81 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | Se | MeOH | BMicDM | Salmonella enterica CIP 8039 | chloramphenicol | MIC 7.81 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | L | MeOH | BMicDM | Staphylococcus aureus CIP 483 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | R | MeOH | BMicDM | Staphylococcus aureus CIP 483 | chloramphenicol | MIC 31.25 µg/mL MBC 31.25 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | S | MeOH | BMicDM | Staphylococcus aureus CIP 483 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | Fl | MeOH | BMicDM | Staphylococcus aureus CIP 483 | chloramphenicol | MIC 7.81 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Morocco | Se | MeOH | BMicDM | Staphylococcus aureus CIP 483 | chloramphenicol | MIC 15.62 µg/mL MBC 15.62 µg/mL |

[74] | |

| Turkey | F | MeOH | DDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6051 | ampicillin | IZ 25 mm | [75] | |

| Turkey | F | MeOH | DDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6051 | ofloxacin | IZ 30 mm | [75] | |

| Turkey | F | MeOH | DDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 11775 | ampicillin | IZ 28 mm | [75] | |

| Turkey | F | MeOH | DDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 11775 | ofloxacin | IZ 28 mm | [75] | |

| Turkey | F | MeOH | DDM | Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 292 | ampicillin | IZ 26 mm | [75] | |

| Turkey | F | MeOH | DDM | Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 292 | ofloxacin | IZ 20 mm | [75] | |

| Turkey | F | MeOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 1014 | ampicillin | IZ 23 mm | [75] | |

| Turkey | F | MeOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 1014 | ofloxacin | IZ 23 mm | [75] | |

| Turkey | F | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 12600 | ampicillin | IZ 20 mm | [75] | |

| Turkey | F | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 12600 | ofloxacin | IZ 26 mm | [75] | |

| Turkey | F | MeOH | DDM | Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 2524 | ampicillin | IZ 22 mm | [75] | |

| Turkey | F | MeOH | DDM | Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 2524 | ofloxacin | IZ 24 mm | [75] | |

| Turkey | Se | MeOH | DDM | Escherichia coli * | erythromycin | IZ 16 mm | [76] | |

| Turkey | Se | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | erythromycin | IZ 16 mm | [76] | |

| Lebanon | Fl | EtOAc | BMicDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | oxacillin and gentamicin | MIC 512 µg/mL | [77] | |

| Lebanon | Fl | EtOAc | BMicDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 | oxacillin and gentamicin | MIC 512 µg/mL | [77] | |

| Lebanon | Fl | EtOAc | BMicDM | Candida albicans ATCC 10231 | oxacillin and gentamicin | MIC 512 µg/mL | [77] | |

| Lebanon | Fl | EtOAc | BMicDM | Trichophyton rubrum SNB-TR | oxacillin and gentamicin | MIC 512 µg/mL | [77] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | BMicDM | Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 13311 | streptomycin | MIC 44.5 ± 0.9 µg/mL MBC 89.0 ± 1.5 µg/mL |

[78] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | BMicDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 35210 | streptomycin | MIC 219.0 ± 3.0 µg/mL MBC 445.0 ± 2.9µg/mL |

[78] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | BMicDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | streptomycin | MIC 219.0 ± 1.7 µg/mL MBC 445.0 ± 5.8 µg/mL |

[78] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | BMicDM | Micrococcus flavus ATCC 9341 | streptomycin | MIC 445.0 ± 5.5 µg/mL MBC 890.0 ± 23.1 µg/mL |

[78] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | BMicDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC 10907 | streptomycin | MIC 890.0 ± 11.0 µg/mL MBC 890.0 ± 5.8 µg/mL |

[78] | |

| Iran | F | na | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | gentamicin | MIC 62.5 ± 4.0 µg/mL MBC 125.0 ± 8.0 µg/mL |

[79] | |

| Turkey | L | Et2O | BDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 | ceftriaxone | MIC 22.8 µg/mL MBC 55.0 µg/mL |

[80] | |

| Turkey | L | Et2O | BDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC BAA-977 | ceftriaxone | MIC 13.7 µg/mL MBC 45.8 µg/mL |

[80] | |

| Turkey | L | Et2O | BDM | Enterococcus eliflavus ATCC 700327 | ceftriaxone | MIC 13.7 µg/mL MBC 27.5 µg/mL |

[80] | |

| Turkey | L | Et2O | BDM | Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 | ceftriaxone | MIC 13.7 µg/mL MBC 27.5 µg/mL |

[80] | |

| Turkey | L | Et2O | BDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | ceftriaxone | MIC 27.5 µg/mL MBC 27.5 µg/mL |

[80] | |

| Turkey | L | Et2O | BDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | ceftriaxone | MIC 27.5 µg/mL MBC 55.0 µg/mL |

[80] | |

| Turkey | L | Et2O | BDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603 | ceftriaxone | MIC 36.6 µg/mL MBC 55.0 µg/mL |

[80] | |

| Turkey | L | Et2O | BDM | Enterobacter hormaechei ATCC 700323 | ceftriaxone | MIC 27.5 µg/mL MBC 27.5 µg/mL |

[80] | |

| Ukraine | L | EtOH | AWDM | Escherichia coli * | azithromycin | IZ 2.8 ± 0.17 mm | [81] | |

| V. altissima | India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus cereus NCIM 2155 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 13.500 ± 0.866 mm |

[82] |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus pumilus NCIM 2327 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 12.330 ± 0.258 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus subtilis NCIM 2063 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 13.160 ± 0.763 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Micrococcus luteus NCIM 2376 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 125 µg/mL MBC 250 µg/mL IZ 14.800 ± 0.793 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Staphylococcus aureus NCIM 2901 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 250 µg/mL MBC 500 µg/mL IZ 14.770 ± 0.437 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Escherichia coli NCIM 2256 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL IZ 8.700 ± 0.435 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae NCIM 2957 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL IZ 8.270 ± 0.801 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIM 5031 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL IZ 8.130 ± 0.814 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Proteus vulgaris NCIM 2027 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL IZ 9.360 ± 0.437 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Salmonella typhimurium NCIM 2501 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL IZ 8.390 ± 0.437 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Shigella flexneri MTCC 1457 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL MBC 2000 µg/mL IZ 11.180 ± 0.822 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Shigella sonnei MTCC 2597 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL MBC 2000 µg/mL IZ 11.760 ± 0.473 mm |

[82] | |

| V . diversifolia | India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus cereus NCIM 2155 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 250 µg/mL MBC 500 µg/mL IZ 14.430 ± 0.473 mm |

[82] |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus pumilus NCIM 2327 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 13.590 ± 0.452 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus subtilis NCIM 2063 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 5000 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 13.740 ± 0.444 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Micrococcus luteus NCIM 2376 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 125 µg/mL MBC 250 µg/mL IZ 16.180 ± 0.822 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Staphylococcus aureus NCIM 2901 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 250 µg/mL IZ 16.320 ± 0.435 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Escherichia coli NCIM 2256 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 4000 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 10.400 ± 0.525 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae NCIM 2957 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 4000 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 10.150 ± 0.581 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIM 5031 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 4000 µg/mL MBC 2000 µg/mL IZ 8.810 ± 0.815 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Proteus vulgaris NCIM 2027 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 4000 µg/mL MBC 2000 µg/mL IZ 10.180 ± 0.822 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Salmonella typhimurium NCIM 2501 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 4000 µg/mL MBC 2000 µg/mL IZ 9.760 ± 0.473 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Shigella flexneri MTCC 1457 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 11.250 ± 0.452 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Shigella sonnei MTCC 2597 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 12.120 ± 0.785 mm |

[82] | |

| V. doniana | Nigeria | Sb | MeOH | BDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | tetracycline | MIC > 500 µg/mL | [83] |

| Nigeria | Sb | MeOH | ADM | Salmonella typhi * | na | MIC 0.31–2.5 µg/mL | [25] | |

| Nigeria | Sb | MeOH | ADM | Shigella dysentarae * | na | MIC 0.02–0.08 µg/mL | [25] | |

| Nigeria | Sb | MeOH | ADM | Escherichia coli * | na | MIC 0.04–0.38 µg/mL | [25] | |

| Nigeria | L | Et2O | DDM | Bacillus subtilis ATTC 33923 | gentamicin | IZ 40 mm | [84] | |

| Nigeria | L | Et2O | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATTC 6538 | gentamicin | IZ 36 mm | [84] | |

| Nigeria | L | Et2O | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATTC 27856 | gentamicin | IZ 36 mm | [84] | |

| Nigeria | L | Et2O | DDM | Bacillus cereus ATTC 14579 | gentamicin | IZ 31 mm | [84] | |

| Nigeria | L | Et2O | DDM | Proteus mirabilis ATTC 21784 | gentamicin | IZ 31 mm | [84] | |

| V. gardneriana | Brazil | L | Et2O | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 | na | MIC 0.31 µg/mL | [85] | |

| V. mollis | Mexico | F | H2O | BMicDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 | gentamicin | IZ 8.8 ± 0.26 mm | [86] |

| Mexico | F | H2O | BMicDM | Escherichia coli A011 | gentamicin | IZ 9.8 ± 0.35 mm | [86] | |

| Mexico | F | H2O | BMicDM | Escherichia coli A055 | gentamicin | IZ 9.5 ± 0.70 mm | [86] | |

| Mexico | F | H2O | BMicDM | Shigella dysenteriae * | gentamicin | IZ 7.5 ± 0.70 mm | [86] | |

| Mexico | F | H2O | BMicDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | gentamicin | IZ 8.8 ± 0.35 mm | [86] | |

| Mexico | F | H2O | BMicDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | gentamicin | IZ 10 ± 1.41 mm | [86] | |

| Mexico | F | H2O | BMicDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | gentamicin | MIC 7.5 µg/mL MBC 7.5 µg/mL |

[86] | |

| Mexico | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 | methicillin | IZ 14.50 ± 0.30 mm | [87] | |

| Mexico | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 | methicillin | IZ 14.63 ± 0.51 mm | [87] | |

| Mexico | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 43300 | methicillin | IZ 12.37 ± 0.40 mm | [87] | |

| Mexico | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus MRSA1 | methicillin | IZ 12.43 ± 0.45 mm | [87] | |

| Mexico | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus MRSA2 | methicillin | IZ 18.53 ± 0.40 mm | [87] | |

| Mexico | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus SOSA1 | oxacillin | IZ 14.34 ± 0.30 mm | [87] | |

| Mexico | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus SOSA2 | oxacillin | IZ 18.60 ± 0.23 mm | [87] | |

| Mexico | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus epidermidis CoNS1 | oxacillin | IZ 18.60 ± 0.23 mm | [87] | |

| Mexico | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus epidermidis CoNS2 | oxacillin | IZ 14.25 ± 0.30 mm | [87] | |

| Mexico | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus epidermidis CoNS3 | oxacillin | IZ 18.53 ± 0.50 mm | [87] | |

| Mexico | F | Chl | DDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | ampicillin | MIC 2.0 μg/mL MBC 2.0 μg/mL |

[88] | |

| V. negundo | India | L | Chl | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | gentamycin | IZ 21 mm | [89] |

| India | L | Chl | AWDM | Bacillus subtilis * | tetracycline | IZ 18 mm | [89] | |

| India | L | Ace | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | gentamycin | IZ 21 mm | [89] | |

| India | L | Ace | AWDM | Bacillus subtilis * | tetracycline | IZ 24 mm | [89] | |

| India | L | Ace | AWDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa * | gentamycin | IZ 19 mm | [89] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | gentamycin | IZ 24 mm | [89] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa * | gentamycin | MIC 0.078 µg/mL | [89] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa * | gentamycin | IZ 18 mm | [89] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | gentamycin | IZ 21 mm | [89] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae * | ciprofloxacin | IZ 16 mm | [89] | |

| India | L | EtOH | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | ciprofloxacin | IZ 11.4 ± 0.23 mm MIC 12.5 µg/mL |

[90] | |

| India | L | EtOH | AWDM | Streptococcus epidermidis * | ciprofloxacin | IZ 12.4 ± 0.14 mm MIC 6.25 µg/mL |

[90] | |

| India | L | EtOH | AWDM | Bacillus cereus * | ciprofloxacin | IZ 14.2 ± 0.14 mm MIC 25 µg/mL |

[90] | |

| India | L | EtOH | AWDM | Corynebacterium xerosis * | ciprofloxacin | IZ 13.53 ± 0.14 mm MIC 50 µg/mL |

[90] | |

| India | L | EtOH | AWDM | Escherichia coli * | gentamycin | IZ 14.0 ± 0.14 mm MIC 25 µg/mL |

[90] | |

| India | L | EtOH | AWDM | Klebsiella pneumonia * | gentamycin | IZ 13.5 ± 0.34 mm MIC 12.5 µg/mL |

[90] | |

| India | L | EtOH | AWDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa * | gentamycin | IZ 10.9 ± 0.20 mm MIC 12.5 µg/mL |

[90] | |

| India | L | EtOH | AWDM | Proteus vulgaris * | gentamycin | IZ 12.5 ± 0.28 mm MIC 6.25 µg/mL |

[90] | |

| India | L | HX | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 3160 | methicillin | IZ 10.3 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | HX | DDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC 619 | methicillin | IZ 11.6 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | HX | DDM | Escherichia coli MTCC 4296 | methicillin | IZ 10.6 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | HX | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 2488 | methicillin | IZ 10.0 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | HX | DDM | Candida albicans MTCC 3018 | methicillin | IZ 9.6 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | HX | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 2488 | methicillin | IZ 10.0 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | HX | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 2488 | methicillin | IZ 10.0 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 3160 | methicillin | IZ 11.6 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC 619 | methicillin | IZ 13.3 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Escherichia coli MTCC 4296 | methicillin | IZ 15.6 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 2488 | methicillin | IZ 15.0 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Candida albicans MTCC 3018 | methicillin | IZ 15.3 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 3160 | methicillin | IZ 21.6 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC 619 | methicillin | IZ 19.6 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Escherichia coli MTCC 4296 | methicillin | IZ 18.3 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 2488 | methicillin | IZ 18.6 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Candida albicans MTCC 3018 | methicillin | IZ 17.6 mm | [91] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | na | IZ 14.0 mm | [92] | |

| India | B | MeOH | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | na | IZ 8.6 mm | [92] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Escherichia coli * | na | IZ 22.5 mm | [92] | |

| India | B | MeOH | AWDM | Escherichia coli * | na | IZ 14.13 mm | [92] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Bacillus subtilis * | na | IZ 11.16 mm | [92] | |

| India | B | MeOH | AWDM | Bacillus subtilis * | na | IZ 6.23 mm | [92] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Klebsiella pneumonia * | na | IZ 8.50 mm | [92] | |

| India | B | MeOH | AWDM | Klebsiella pneumonia * | na | IZ 4.4 mm | [92] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | na | IZ 14.1 mm | [92] | |

| India | B | MeOH | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | na | IZ 8.8 mm | [92] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Escherichia coli * | na | IZ 22.8 mm | [92] | |

| India | B | MeOH | AWDM | Escherichia coli * | na | IZ 14.22 mm | [92] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Bacillus subtilis * | na | IZ 11.05 mm | [92] | |

| India | B | MeOH | AWDM | Bacillus subtilis * | na | IZ 6.8 mm | [92] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Klebsiella pneumonia * | na | IZ 8.22 mm | [92] | |

| India | B | MeOH | AWDM | Klebsiella pneumonia * | na | IZ 4.26 mm | [92] | |

| India | L | Et2O | BMicDM | Escherichia coli MTCC-724 | na | MIC 3.28 ± 1.24 μg/mL | [93] | |

| India | L | Et2O | BMicDM | Enterobacter aerogenes MTCC-39 | na | MIC 21.26 ± 1.04 μg/mL | [93] | |

| India | L | Et2O | BMicDM | Enterococcus faecalis MTCC-2729 | na | MIC 21.07 ± 1.70 μg/mL | [93] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMicDM | Escherichia coli MTCC-724 | na | MIC 3.28 ± 1.24 μg/mL | [93] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMicDM | Enterobacter aerogenes MTCC-39 | na | MIC 21.26 ± 1.04 μg/mL | [93] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMicDM | Enterococcus faecalis MTCC-2729 | na | MIC 21.07 ± 1.70 μg/mL | [93] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | BMicDM | Staphylococcus aureus BMLRU1002 and pseudomonas aeruginosa BMLRU1007 | tetracycline | MIC 0.312 μg/mL | [94] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | BMicDM |

Bacillus subtilis BMLRU1008 Salmonella typhi BMLRU1009 |

tetracycline | MIC 1.255 μg/mL | [94] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | BMicDM | Escherichia coli BMLRU1001 | tetracycline | MIC 0.60 μg/mL | [94] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Escherichia coli * | chloramphenicol | IZ 12 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Klebsiella aerogenes * | chloramphenicol | IZ 13 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Proteus vulgaris * | chloramphenicol | IZ 16 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Pseudomonas aerogenes * | chloramphenicol | IZ 20 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Escherichia coli * | chloramphenicol | IZ 14 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Klebsiella aerogenes * | chloramphenicol | IZ 16 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Proteus vulgaris * | chloramphenicol | IZ 14 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | EtOAc | DDM | Pseudomonas aerogenes * | chloramphenicol | IZ 15 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | Et2O | DDM | Escherichia coli * | chloramphenicol | IZ 22 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | Et2O | DDM | Klebsiella aerogenes * | chloramphenicol | IZ 22 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | Et2O | DDM | Proteus vulgaris * | chloramphenicol | IZ 19 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | Et2O | DDM | Pseudomonas aerogenes * | chloramphenicol | IZ 20 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Escherichia coli * | chloramphenicol | IZ 17 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Klebsiella aerogenes * | chloramphenicol | IZ 15 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Proteus vulgaris * | chloramphenicol | IZ 19 mm | [95] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aerogenes * | chloramphenicol | IZ 19 mm | [95] | |

| Vietnam | L | EtOH | BDM | Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus * | spiramycin | MIC 90 μg/mL | [96] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aerogenes * | na | IZ 7 mm | [97] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Klebsiella pneumonia * | na | IZ 9 mm | [97] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | na | IZ 7 mm | [97] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Bacillus cereus * | na | IZ 8 mm | [97] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus cereus NCIM 2155 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 13.550 ± 0.473 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus pumilus NCIM 2327 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 12.280 ± 0.710 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus subtilis NCIM 2063 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL MBC 2000 µg/mL IZ 12.060 ± 0.877 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Micrococcus luteus NCIM 2376 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 13.180 ± 0.499 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Staphylococcus aureus NCIM 2901 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 13.410 ± 0.717 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Escherichia coli NCIM 2256 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL IZ 7.920 ± 0.917 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae NCIM 2957 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL IZ 8.360 ± 0.439 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIM 5031 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL IZ 8.070 ± 0.767 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Proteus vulgaris NCIM 2027 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL IZ 8.800 ± 0.822 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Salmonella typhimurium NCIM 2501 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL IZ 7.430 ± 0.473 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Shigella flexneri MTCC 1457 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL MBC 2000 µg/mL IZ 10.590 ± 0.452 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Shigella sonnei MTCC 2597 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL MBC 2000 µg/mL IZ 11.380 ± 0.469 mm |

[82] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | DDM | Vibrio cholerae AY-1868921 | ciprofloxacin | IZ 21.133 ± 0.503 mm | [48] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | DDM | Vibrio cholerae O139 NIHCO270 | ciprofloxacin | IZ 19.700 ± 0.529 mm | [48] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | DDM | Escherichia coli O157:H7 M-885496 | ciprofloxacin | IZ 15.233 ± 0.351 mm | [48] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | DDM | Shigella dysenteriae Vm110432 | ciprofloxacin | IZ 10.566 ± 0.568 mm | [48] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | DDM | Shigella flexneri M-12163 | ciprofloxacin | IZ 12.066 ± 0.568 mm | [48] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | DDM | Shigella boydi M-297092 | ciprofloxacin | IZ 11.733 ± 0.723 mm | [48] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | DDM | Shigella sonnei M-275521 | ciprofloxacin | IZ 13.466 ± 0.288 mm | [48] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | DDM | Vibrio parahaemolyticus AQ-3794 | ciprofloxacin | IZ 18.466 ± 0.472 mm | [48] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | DDM | Vibrio mimicus MGL-2585 | ciprofloxacin | IZ 9.966 ± 0.702 mm | [48] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | DDM | Aeromonas sobria MGL-3585/1 | ciprofloxacin | IZ 16.700 ± 0.435 mm | [48] | |

| Bangladesh | L | MeOH | DDM | Aeromonas cavie MGL-3615/1 | ciprofloxacin | IZ 17.733 ± 0.568 mm | [48] | |

| Pakistan | L | MeOH | ADM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 | erythromycin and cefixime | MIC 1µg/mL | [98] | |

| Pakistan | L | MeOH | ADM | Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 19433 | erythromycin and cefixime | MIC 1 µg/mL | [98] | |

| Pakistan | L | MeOH | ADM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 7221 | erythromycin and cefixime | MIC 1 µg/mL | [98] | |

| Pakistan | L | MeOH | ADM | Vibrio cholera ATCC 11623 | erythromycin and cefixime | MIC 1 µg/mL | [98] | |

| Pakistan | L | MeOH | ADM | Entrobacter coccus ATCC 13048 | erythromycin and cefixime | MIC 1 µg/mL | [98] | |

| Pakistan | L | MeOH | ADM | Klibsella pneumonia ATCC UC57 | erythromycin and cefixime | MIC 1 µg/mL | [98] | |

| Nepal | L | MeOH | AWPM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC6051 | ampicillin | MBC 1.562 µg/mL | [49] | |

| Nepal | L | MeOH | AWPM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC653P | ampicillin | MBC 6.25 µg/mL | [49] | |

| Nepal | L | MeOH | AWPM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC6051 | ampicillin | MBC 2.372µg/mL | [49] | |

| Nepal | L | MeOH | AWPM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC653P | ampicillin | MBC 0.245 µg/mL | [49] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BDM | Escherichia coli Dk1 | methicillin | MIC 35.00 µg/mL | [99] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BDM | Staphylococcus aureus MRS901 | methicillin | MIC 40.00 µg/mL | [99] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Vibrio cholerae 3906 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 12.73 ± 0.64 mm | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Escherichia coli 118 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 21.9 ± 0.85 mm | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Escherichia coli 614 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 18.8 ± 0.72 mm | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Shigella flexneri 1457 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 12.3 ± 1.2 mm | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Shigella flexneri 9543 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 17.16 ± 1.04 mm | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Salmonella enterica typhimurium 98 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 15.8 ± 0.72 mm | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Salmonella enterica ser. typhi 733 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 10.8 ± 0.08 mm | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Salmonella paratyphi 3220 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 11.43 ± 0.4 mm | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae 109 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 18.4 ± 0.64 mm | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1035 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 12.1 ± 1.7 mm | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1035 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 12.1 ± 1.7 mm | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Enterococcus faecalis 2729 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 13.6 ± 1.23 mm | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH and DCM | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus 1430 | fluconazole and clotrimazole | IZ 14.7 ± 0.82 mm | [100] | |

| India | L | EtOH | PDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633 | amoxicillin | IZ 0.21 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | PE | PDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633 | amoxicillin | IZ 0.21 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | EtOH | PDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633 | amoxicillin | IZ 0.25 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | PE | PDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633 | amoxicillin | IZ 0.25 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | EtOH | PDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC6538P | amoxicillin | IZ 0.25 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | PE | PDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC6538P | amoxicillin | IZ 0.21 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | EtOH | PDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC6538P | amoxicillin | IZ 0.21 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | PE | PDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC6538P | amoxicillin | IZ 0.25 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC6538P | amoxicillin | IZ 0.34 ± 0.06 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC6538P | amoxicillin | IZ 0.53 ± 0.07 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC6538P | amoxicillin | IZ 0.53 ± 0.09 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633 | amoxicillin | IZ 0.42 ± 0.13 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633 | amoxicillin | IZ 0.46 ± 0.06 mm | [101] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC6633 | amoxicillin | IZ 0.5 ± 0.08 mm | [101] | |

| India | Sb | HX | AWDM | Escherichia coli MTCC B1560 | ciprofloxacin | MIC > 1000 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | Chl | AWDM | Escherichia coli MTCC B1560 | ciprofloxacin | MIC > 1000 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | MeOH | AWDM | Escherichia coli MTCC B1560 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | HX | AWDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae MTCC B4030 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | Chl | AWDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae MTCC B4030 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | MeOH | AWDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae MTCC B4030 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 250 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | HX | AWDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC B2297 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | Chl | AWDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC B2297 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 250 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | MeOH | AWDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC B2297 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 62.5 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | HX | AWDM | Proteus vulgaris MTCC B7299 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | Chl | AWDM | Proteus vulgaris MTCC B7299 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 62.5 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | MeOH | AWDM | Proteus vulgaris MTCC B7299 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 31.2 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | HX | AWDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC B2274 | ciprofloxacin | MIC > 1000 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | Chl | AWDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC B2274 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | MeOH | AWDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC B2274 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | HX | AWDM | Enterococcus faecalis MTCC B3159 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | Chl | AWDM | Enterococcus faecalis MTCC B3159 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | MeOH | AWDM | Enterococcus faecalis MTCC B3159 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 250 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | HX | AWDM | Micrococcus luteus MTCC B1538 | ciprofloxacin | MIC > 1000 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | Chl | AWDM | Micrococcus luteus MTCC B1538 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | MeOH | AWDM | Micrococcus luteus MTCC B1538 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 62.5 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | HX | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC B3160 | ciprofloxacin | MIC > 1000 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | Chl | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC B3160 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | MeOH | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC B3160 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 250 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | HX | AWDM | Streptococcus pneumoniae MTCC B2672 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | Chl | AWDM | Streptococcus pneumoniae MTCC B2672 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | Sb | MeOH | AWDM | Streptococcus pneumoniae MTCC B2672 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 62.5 µg/mL | [102] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 1144 | gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | MIC 5000 µg/mL | [103] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Escherichia coli * | gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | MIC 2500 µg/mL | [103] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Shigella flexneri * | gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | MIC 1250 µg/mL | [103] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Vibrio cholerae MTCC 3904 | gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | MIC 5000 µg/mL | [103] | |

| India | B | MeOH | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 1144 | gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | MIC 5000 µg/mL | [103] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Escherichia coli * | gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | MIC 5000 µg/mL | [103] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Shigella flexneri* | gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | MIC 5000 µg/mL | [103] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Vibrio cholerae MTCC 3904 | gentamicin and ciprofloxacin | MIC 5000 µg/mL | [103] | |

| India | B | PE | DDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC 7164 | ampicillin | IZ 10.3 ± 1.15 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | PE | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 1144 | ampicillin | IZ 11.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | PE | DDM | Escherichia coli MTCC 1098 | ampicillin | IZ 12.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | PE | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 1034 | ampicillin | IZ 11.0 ± 0.00 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | PE | DDM | Vibrio cholerae MTCC 3904 | ampicillin | IZ 11.0 ± 0.00 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | PE | DDM | V. alginolyteus MTCC 4439 | ampicillin | IZ 12.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC 7164 | ampicillin | IZ 8.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | Staphylococcus epidermidis MTCC 3615 | ampicillin | IZ 11.3 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | Escherichia coli MTCC 1098 | ampicillin | IZ 12.3 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | Salmonella typhimurium MTCC 3216 | ampicillin | IZ 10.0 ± 1.73 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 1034 | ampicillin | IZ 11.0 ± 0.00 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | Vibrio cholerae MTCC 3904 | ampicillin | IZ 11.0 ± 0.00 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | V. alginolyteus MTCC 4439 | ampicillin | IZ 13.0 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | Chl | DDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC 7164 | ampicillin | IZ 9.6 ± 2.08 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | Chl | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 1144 | ampicillin | IZ 10.3 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | Chl | DDM | Staphylococcus epidermidis MTCC 3615 | ampicillin | IZ 13.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | Chl | DDM | Escherichia coli MTCC 1098 | ampicillin | IZ 13.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | Chl | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 1034 | ampicillin | IZ 10.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | Chl | DDM | Vibrio cholerae MTCC 3904 | ampicillin | IZ 9.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | Chl | DDM | V. alginolyteus MTCC 4439 | ampicillin | IZ 12.3 ± 1.52 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | Chl | DDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC 7164 | ampicillin | IZ 10.3 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | Chl | DDM | Staphylococcus epidermidis MTCC 3615 | ampicillin | IZ 11.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | Chl | DDM | Escherichia coli MTCC 1098 | ampicillin | IZ 13.0 ± 1.00 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | Chl | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 1034 | ampicillin | IZ 12.3 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | Chl | DDM | Vibrio cholerae MTCC 3904 | ampicillin | IZ 11.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | Chl | DDM | V. alginolyteus MTCC 4439 | ampicillin | IZ 11.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | EtOH | DDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC 7164 | ampicillin | IZ 11. 6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | EtOH | DDM | Staphylococcus epidermidis MTCC 3615 | ampicillin | IZ 11.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | EtOH | DDM | Escherichia coli MTCC 1098 | ampicillin | IZ 13.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | EtOH | DDM | Salmonella typhimurium MTCC 3216 | ampicillin | IZ 11.3 ± 0.57mm | [104] | |

| India | B | EtOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 1034 | ampicillin | IZ 13.0 ± 0.00 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | EtOH | DDM | Vibrio cholerae MTCC 3904 | ampicillin | IZ 11.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | EtOH | DDM | V. alginolyteus MTCC 4439 | ampicillin | IZ 11.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC 7164 | ampicillin | IZ 11.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Staphylococcus epidermidis MTCC 3615 | ampicillin | IZ 13.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Escherichia coli MTCC 1098 | ampicillin | IZ 16.3 ± 1.52 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Salmonella typhimurium MTCC 3216 | ampicillin | IZ 11.3 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 1034 | ampicillin | IZ 11.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Vibrio cholerae MTCC 3904 | ampicillin | IZ 9.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | V. alginolyteus MTCC 4439 | ampicillin | IZ 11.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | MeOH | DDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC 7164 | ampicillin | IZ 13.0 ± 1.00 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 1144 | ampicillin | IZ 11.3 ± 1.15 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus epidermidis MTCC 3615 | ampicillin | IZ 13.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | MeOH | DDM | Escherichia coli MTCC 1098 | ampicillin | IZ 12.3 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | MeOH | DDM | Salmonella typhimurium MTCC 3216 | ampicillin | IZ 11.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | MeOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 1034 | ampicillin | IZ 10.6 ± 1.15 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | MeOH | DDM | Vibrio cholerae MTCC 3904 | ampicillin | IZ 13.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | B | MeOH | DDM | V. alginolyteus MTCC 4439 | ampicillin | IZ 9.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC 7164 | ampicillin | IZ 9.3 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 1144 | ampicillin | IZ 8.0 ± 0.00 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus epidermidis MTCC 3615 | ampicillin | IZ 11.3 ± 1.15 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Escherichia coli MTCC 1098 | ampicillin | IZ 12.3 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Salmonella typhimurium MTCC 3216 | ampicillin | IZ 9.0 ± 1.00 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 1034 | ampicillin | IZ 13.3 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Vibrio cholerae MTCC 3904 | ampicillin | IZ 11.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | V. alginolyteus MTCC 4439 | ampicillin | IZ 9.6 ± 0.57 mm | [104] | |

| India | L | na | na | Staphylococcus aureus * | na | IZ 14 mm | [105] | |

| India | L | na | na | Proteus mirabilis * | na | IZ 10 mm | [105] | |

| India | L | na | na | Vibrio cholerae * | na | IZ 12 mm | [105] | |

| India | L | na | na | Pseudomonas aeruginosa * | na | IZ 12 mm | [105] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae MTCC 7407 | rifampicin | IZ 13.0 ± 0.21 mm | [106] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Staphylococc usaureus MTCC 96 | rifampicin | IZ 11.0 ± 0.12 mm | [106] | |

| India | L | EtOH | BMicDM | Streptococcus faecalis * | fluconazole | MIC 125 µg/mL | [107] | |

| India | L | EtOH | BMicDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae * | fluconazole | MIC 250 µg/mL | [107] | |

| India | L | EtOH | BMicDM | Escherichia coli * | fluconazole | MIC 250 µg/mL | [107] | |

| India | L | EtOH | BMicDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa * | fluconazole | MIC 500 µg/mL | [107] | |

| India | L | EtOH | BMicDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | fluconazole | MIC 250 µg/mL | [107] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Bacillus cereus NCIM 2156 | chloramphenicol | IZ 0.68 mm | [108] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus NCIM 2654 | chloramphenicol | IZ 0.66 mm | [108] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | S. epidermidis NCIM 2493 | chloramphenicol | IZ 0.71 mm | [108] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Mycobacterium smegmatis NCIM 5138 | chloramphenicol | IZ 0.88 mm | [108] | |

| India | Se | EtOH | DDM | Bacillus cereus NCIM 2156 | chloramphenicol | IZ 0.72 mm | [108] | |

| India | Se | EtOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus NCIM 2654 | chloramphenicol | IZ 0.63 mm | [108] | |

| India | Se | EtOH | DDM | S. epidermidis NCIM 2493 | chloramphenicol | IZ 0.76 mm | [108] | |

| India | Se | EtOH | DDM | Mycobacterium smegmatis NCIM 5138 | chloramphenicol | IZ 0.72 mm | [108] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Escherichia coli NCIM 2027 | streptomycin | IZ 0.88 mm | [108] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIM 5032 | streptomycin | IZ 1.0 mm | [108] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Proteus vulgaris NCIM 2027 | streptomycin | IZ 0.78 mm | [108] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Salmonella typhimurium NCIM 2501 | streptomycin | IZ 0.80 mm | [108] | |

| India | Se | EtOH | DDM | Escherichia coli NCIM 2027 | streptomycin | IZ 0.86 mm | [108] | |

| India | Se | EtOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIM 5032 | streptomycin | IZ 0.90 mm | [108] | |

| India | Se | EtOH | DDM | Proteus vulgaris NCIM 2027 | streptomycin | IZ 0.84 mm | [108] | |

| India | Se | EtOH | DDM | Salmonella typhimurium NCIM 2501 | streptomycin | IZ 0.72 mm | [108] | |

| India | L | EtOH | BDM | Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 7443 | chloramphenicol | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL |

[109] | |

| India | L | EtOH | BDM | Micrococcus luteus MTCC 4821 | chloramphenicol | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL |

[109] | |

| India | L | EtOH | BDM | Bacillus subtilis MTCC 2389 | chloramphenicol | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL |

[109] | |

| India | L | EtOH | BDM | Escherichia coli MTCC 2127 | ampicillin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL |

[109] | |

| India | L | EtOH | BDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae MTCC 7172 | ampicillin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL |

[109] | |

| India | L | na | DDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae * | na | MIC 400 µg/mL | [110] | |

| India | L | na | DDM | Escherichia coli * | na | MIC 400 µg/mL | [110] | |

| India | L | na | DDM | Salmonella Para typh | na | MIC 400 µg/mL | [110] | |

| India | L | na | DDM | Salmonella typhi * | na | MIC 400 µg/mL | [110] | |

| Malaysia | L | MeOH | DDM | Escherichia coli * | cefotaxime | IZ 28.0 ± 0.5 mm | [111] | |

| Malaysia | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | cefotaxime | IZ 21.0 ± 1.5 mm | [111] | |

| V. obovata | South Africa | L | MeOH | ADM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 0.02 µg/mL | [50] |

| South Africa | L | MeOH | ADM | Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 0.02 µg/mL | [50] | |

| South Africa | L | MeOH | ADM | Escherichia coli ATCC 11775 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 4.00 µg/mL | [50] | |

| V. peduncularis | India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus cereus NCIM 2155 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 125 µg/mL MBC 250 µg/mL IZ 18.040 ± 0.876 mm |

[82] |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus pumilus NCIM 2327 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 125 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 16.770 ± 0.473 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus subtilis NCIM 2063 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 125 µg/mL MBC 250 µg/mL IZ 17.160 ± 0.817mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Micrococcus luteus NCIM 2376 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 62.05 µg/mL MBC 125.0 µg/mL IZ 21.590 ± 0.821 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Staphylococcus aureus NCIM 2901 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 62.05 µg/mL MBC 125.0 µg/mL IZ 22.600 ± 0.755 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Escherichia coli NCIM 2256 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 13.680 ± 0.520 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae NCIM 2957 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL MBC 2000 µg/mL IZ 11.190 ± 0.810 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIM 5031 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 12.730 ± 0.452 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Proteus vulgaris NCIM 2027 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 12.430 ± 0.473 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Salmonella typhimurium NCIM 2501 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 12.590 ± 0.821 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Shigella flexneri MTCC 1457 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 250 µg/mL MBC 500 µg/mL IZ 14.430 ± 0.391 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Shigella sonnei MTCC 2597 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 250 µg/mL MBC 500 µg/mL IZ 15.310 ± 0.605 mm |

[82] | |

| V. pinnata | Indonesia | L | MeOH | BMicDM | Streptococcus mutans * | na | −1.48 μg/mL | [112] |

| Indonesia | L | HX | BMicDM | Streptococcus mutans * | na | −1.45 μg/mL | [112] | |

| Indonesia | L | EtOAc | BMicDM | Streptococcus mutans * | na | −0.17 μg/mL | [112] | |

| Indonesia | B | EtOH | BDM | Propionibacterium acnes ATCC 6919 | chloramphenicol | MIC 1.00 μg/mL | [54] | |

| Indonesia | B | MeOH | BDM | Propionibacterium acnes ATCC 6919 | chloramphenicol | MIC 2.00 μg/mL | [54] | |

| Indonesia | S | EtOH | BDM | Propionibacterium acnes ATCC 6919 | chloramphenicol | MIC 1.00 μg/mL | [54] | |

| Indonesia | S | MeOH | BDM | Propionibacterium acnes ATCC 6919 | chloramphenicol | MIC 1.00 μg/mL | [54] | |

| Brunei | L | EtOAc | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 | streptomycin | IZ 6.2 ± 0.5 mm | [113] | |

| Brunei | L | EtOAc | DDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC 11774 | streptomycin | IZ 9.3 ± 0.5 mm | [113] | |

| Brunei | L | Chl | DDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC 11774 | streptomycin | IZ 9.3 ± 0.1 mm | [113] | |

| Brunei | L | HX | DDM | Bacillus subtilis ATCC 11774 | streptomycin | IZ 8.2 ± 1.2 mm | [113] | |

| Brunei | L | Chl | DDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 11775 | streptomycin | IZ 8.4 ± 0.1 mm | [113] | |

| Brunei | L | EtOAc | DDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 11775 | streptomycin | IZ 10.2 ± 0.3 mm | [113] | |

| Brunei | L | EtOAc | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | streptomycin | IZ 6.2 ± 0.5 mm | [113] | |

| V. pooara | South Africa | L | Ace | ADM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | nordihydroguaiaretic | MIC 32 µg/mL | [114] |

| South Africa | L | Ace | ADM | Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778 | nordihydroguaiaretic | MIC 16 µg/mL | [114] | |

| South Africa | L | MeOH | ADM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1.00 µg/mL | [50] | |

| South Africa | L | MeOH | ADM | Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 0.50 µg/mL | [50] | |

| South Africa | L | MeOH | ADM | Escherichia coli ATCC 11775 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 8.00 µg/mL | [50] | |

| V. pseudo-negundo | Iran | L | MeOH | AWDM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 | na | MIC 22.6 ± 0.3 µg/mL | [115] |

| Iran | L | MeOH | AWDM | Escherichia coli ATCC 35150 | na | MIC 17.1 ± 0.2 µg/mL | [115] | |

| V. rehmannii | South Africa | L | Ace | ADM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | nordihydroguaiaretic | MIC 16 µg/mL | [114] |

| South Africa | L | Ace | ADM | Bacillus cereusATCC 11778 | nordihydroguaiaretic | MIC 8 µg/mL | [114] | |

| South Africa | L | MeOH | ADM | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | nordihydroguaiaretic | MIC 0.02 µg/mL | [114] | |

| South Africa | L | MeOH | ADM | Bacillus cereusATCC 11778 | nordihydroguaiaretic | MIC 0.02 µg/mL | [114] | |

| South Africa | L | MeOH | ADM | Escherichia coli ATCC 11775 | nordihydroguaiaretic | MIC 4.00 µg/mL | [114] | |

| V. trifolia | India | L | Peth | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa * | chloramphenicol | IZ 5 mm | [116] |

| India | L | Chl | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa * | chloramphenicol | IZ 22 mm | [116] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa * | chloramphenicol | IZ 17 mm | [116] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae * | chloramphenicol | IZ 18 mm | [116] | |

| India | L | Chl | DDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae * | chloramphenicol | IZ 22 mm | [116] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae * | chloramphenicol | IZ 18 mm | [116] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | Streptococcus pyogenes * | chloramphenicol | IZ 18 mm | [116] | |

| India | L | Chl | DDM | Streptococcus pyogenes * | chloramphenicol | IZ 20 mm | [116] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Streptococcus pyogenes * | chloramphenicol | IZ 17 mm | [116] | |

| India | L | PE | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | chloramphenicol | IZ 14 mm | [116] | |

| India | L | Chl | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | chloramphenicol | IZ 19 mm | [116] | |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Staphylococcus aureus * | chloramphenicol | IZ 15 mm | [116] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus cereus NCIM 2155 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 250 µg/mL MBC 500 µg/mL IZ 15.490 ± 0.526 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus pumilus NCIM 2327 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 14.820 ± 0.320 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Bacillus subtilis NCIM 2063 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 250 µg/mL MBC 500 µg/mL IZ 14.300 ± 0.611 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Micrococcus luteus NCIM 2376 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 125 µg/mL MBC 250 µg/mL IZ 16.590 ± 0.452 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Staphylococcus aureus NCIM 2901 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 125 µg/mL MBC 250 µg/mL IZ 17.500 ± 0.347 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Escherichia coli NCIM 2256 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL MBC 2000 µg/mL IZ 11.550 ± 0.195 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Klebsiella pneumoniae NCIM 2957 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL MBC 2000 µg/mL IZ 10.590 ± 0.821 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIM 5031 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 1000 µg/mL MBC 2000 µg/mL IZ 8.810 ± 0.790 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Proteus vulgaris NCIM 2027 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL IZ 9.810 ± 0.330 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Salmonella typhimurium NCIM 2501 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 2000 µg/mL MBC 4000 µg/mL IZ 10.420 ± 0.412 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Shigella flexneri MTCC 1457 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 12.250 ± 0.452 mm |

[82] | |

| India | L | MeOH | BMacDM | Shigella sonnei MTCC 2597 | ciprofloxacin | MIC 500 µg/mL MBC 1000 µg/mL IZ 12.930 ± 0.713 mm |

[82] | |

| Malaysia | L | MeOH | DDM | Bacillus ceres NRRL 14591B | nystatin and streptomycin | MIC 62 µg/mL | [117] | |

| Malaysia | L | MeOH | DDM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa UI-60690 | nystatin and streptomycin | MIC 125 µg/mL | [117] |

Ace—Acetone; ADM—Agar Dilution Method; ADM—Agar Dilution Method; AWDM—Agar Well Dilution Method; B—Bark; BDM—Broth Dilution Method; BMacDM—Broth Macrodilution Method; BMicDM—Broth Microdilution Method; Chl—Chloroform; DCM—Dichloromethane; DDM—Disc Diffusion Method; EC50—Median Inhibition Concentration; Et2O—Diethyl Ether; EtoAc—Ethyle acetate; EtOH—Ethanol; F—Fruit; Fl—Flower; H2O—Water; HX—Hexane; IZ—Inhibition Zone; L—Leaf; MBC—Minimum Bactericidal Concentration; Mean ± standard error; MeOH—Methanol; MIC—Minimum Inhibition Concentration; na—Not available; PDM—Paper Disc Method; PE—Petroliumether; R—Root; Sb—Steambark; Se—Seed; *—Strain not indicated.

Graphical interpretations of these results can be seen in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6. Figure 3 shows that V. negundo is the most studied Vitex species (38%), followed by V. agnus-castus (29%). Other species do not have the same expression in terms of scientific research focus. In Figure 4 and Figure 5, we can see that most of the studies focused on leaf plant parts and methanolic and ethanolic extracts of plant material. An analysis of Figure 6 shows the main bacterial strains that Vitex species have been tested on. These strains are widely known to be responsible for infections in humans, which makes the antibacterial activity exhibited by Vitex species an important focus of research for the development of new drugs.

Figure 3.

Vitex species studied for their in vitro antibacterial activity.

Figure 4.

Plant parts used in antibacterial studies.

Figure 5.

Solvents used for plant extraction for antibacterial activity essays.

Figure 6.

The microorganisms were extensively studied for their interactions with Vitex species.

Collected data show that all Vitex species used in traditional medicine to treat symptoms of infectious diseases exhibit in vitro antimicrobial activity against several bacterial strains, which can justify their use in traditional medicine to treat symptoms of infectious diseases.

2.4. In Vitro Antifungal, Antiviral, and Antiprotozoal Activity

Results showed that Vitex species exhibit biological activity, such as through antifungal, antiprotozoal, and antiviral activities. This information is summarized in Table 3 and Table 4. V. negundo and V. agnus-castus were the most studied plant species against a wider variety of these types of microorganisms. Methanolic extracts of leaf and root were the most frequent types of extract and plant parts used. Microbial agents tested were mostly fungal, namely C. albicans and A. niger, but viruses like HIV-1 and parasites like Plasmodium falciparum were also tested. Nevertheless, the most noteworthy significant value was observed in terms of antifungal activity against C. albicans. For example, an antifungal activity evaluation of ethanolic, methanolic, and aqueous extracts of the V. agnus-castus leaf showed that all had the ability to inhibit Candida species growth. Minimum inhibitory concentrations of studied extracts ranged from 25 µg/mL to 12.5 µg/mL against C. tropicalis, C. albicans, and C. ciferri while minimum fungicidal concentrations ranged from 100 µg/mL to 25 µg/mL [118].

Table 3.

In vitro antifungal activity studies on Vitex species.

| Species | Country | Plant Part Use | Extractive Solvent | Test Type | Strains/Microorganism | Result/MIC/MFC (µg/mL, mm) |

Positive Control | BR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V. agnus castus | Saudi Arabia | L | EtOH | AWDM | Candida tropicalis * | MFC 25 MIC 25 |

Nystatin (10 µg) | [118] |

| Saudi Arabia | L | MeOH | AWDM | Candida tropicalis * | MFC 50 MIC 25 |

Nystatin (10 µg) | [118] | |

| Saudi Arabia | L | H2O | AWDM | Candida tropicalis * | MFC 50 MIC 25 |

Nystatin (10 µg) | [118] | |

| Saudi Arabia | L | EtOH | AWDM | Candida albicans * | MFC 50 MIC 25 |

Nystatin (10 µg) | [118] | |

| Saudi Arabia | L | MeOH | AWDM | Candida albicans * | MFC 100 MIC 25 |

Nystatin (10 µg) | [118] | |

| Saudi Arabia | L | H2O | AWDM | Candida albicans * | MFC 50 MIC 25 |

Nystatin (10 µg) | [118] | |

| Saudi Arabia | L | EtOH | AWDM | Candida ciferrii * | MFC 50 MIC 25 |

Nystatin (10 µg) | [118] | |

| Saudi Arabia | L | MeOH | AWDM | Candida ciferrii * | MFC 50 MIC 25 |

Nystatin (10 µg) | [118] | |

| Saudi Arabia | L | H2O | AWDM | Candida ciferrii * | MFC 50 MIC 25 |

Nystatin (10 µg) | [118] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | GIT | Alternaria alternata * | EC50:167 (109–222) range | na | [69] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | GIT | Botrytis cinerea * | EC50: 462 (373–592) range | na | [69] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | GIT | Fusarium oxysporum * | EC50: 532 (413–740) range | na | [69] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | GIT | Fusarium solani * | EC50: >1000 | na | [69] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | GIT | Alternaria alternata * | EC50: 229 (193–270) range | na | [69] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | GIT | Botrytis cinerea * | EC50: 245 (213–281) range | na | [69] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | GIT | Fusarium oxysporum * | EC50: 222 (182–269) range | na | [69] | |

| Egypt | L | Et2O | GIT | Fusarium solani * | EC50: 369 (314–453) range | na | [69] | |

| Iran | L | EtOH | MDM | Candida albicans * | MIC 0.25–8 range | Fluconazole | [119] | |

| Egypt | L, Fl | EtOH | SDB | Rhizoctonia solani * | MIC 400 | Fluconazole | [120] | |

| Turkey | L | MeOH | BMicDM | Candida albicans * | MIC 0.39 | Ampicillin (10 µg/disc), penicillin (10 µg/disc) | [121] | |

| Egypt | L, F | MeOH | BDM | Aspergillus flavus LC325160 | MGI 2000 | na | [122] | |

| Egypt | L, F | MeOH | BDM |

Cladosporium cladosporioides

LC325159 |

MGI 2000 | na | [122] | |

| Egypt | L, F | MeOH | BDM | Penicillium chrysogenum * | MGI 2000 | na | [122] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | MDM | Alternaria alternata DSM 2006 | MIC 130.0 ± 2.9 MFC 178.0 ± 1.2 |

Bifonazole | [78] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | MDM | Aspergillus flavus ATCC 9643 | MIC 178.0 ± 1.2 MFC 178.0 ± 0.6 |

Bifonazole | [78] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | MDM | Aspergillus niger ATCC 6275 | MIC 178.0 ± 2.1 MFC 219.0 ± 1.5 |

Bifonazole | [78] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | MDM | Aspergillus ochraceus ATCC 12066 | MIC 219.0 ± 2.3 MFC 219.0 ± 1.5 |

Bifonazole | [78] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | MDM | Fusarium tricinctum CBS 514478 | MIC 178.0 ± 2.1 MFC 219.0 ± 3.5 |

Bifonazole | [78] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | MDM | Penicillium ochrochloron ATCC 9112 | MIC 178.0 ± 1.2 MFC 219.0 ± 2.3 |

Bifonazole | [78] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | MDM | Penicillium funiculosum ATCC 36839 | MIC 178.0 ± 0.6 MFC 219.0 ± 3.5 |

Bifonazole | [78] | |

| Serbia | L | EtOH | MDM | Trichoderma viride JCM 22452 | MIC 267.0 ± 1.7 MFC 267.0 ± 2.0 |

Bifonazole | [78] | |

| Turkey | L | Na | BDM | Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 | MIC 31.2 MFC 62.5 |

Fluconazole | [80] | |

| Turkey | L | Na | BDM | Candida albicans ATCC 14053 | MIC > 250 MFC > 250 |

Fluconazole | [80] | |

| V. doniana | Nigeria | L | Na | ADM | Candida albicans MTTC 227 | IZ 36 mm | Gentamicin | [84] |

|

V. gardneriana

|

Brazil | L | EtOH | BMicDM | C. albicans ATCC 90028 | MIC 4 | Amphotericin | [28] |

| Brazil | L | EtOH | BMicDM | C. tropicalis LABMIC 0110 | MIC 4 | Amphotericin | [28] | |

| Brazil | L | EtOH | BMicDM | C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 | MIC 4 | Amphotericin | [28] | |

| Brazil | L | EtOH | BMicDM | C. krusei LABMIC 0124 | MIC 4 | Amphotericin | [28] | |

| V. mollis | Mexico | Se | MeOH | BDM | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides * | MGI 100 ± 0.0 | Thiabendazole | [123] |

| Mexico | Se | HX | BDM | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides * | MGI 100 ± 0.0 | Thiabendazole | [123] | |

| Mexico | Se | EtOAc | BDM | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides * | MGI 100 ± 0.0 | Thiabendazole | [123] | |

| V. negundo | India | L | ButOH | AWDM | Fusarium verticillioides * | MIC 1.25 | na | [124] |

| India | L | MeOH | DDM | Colletotrichum gloeosporioides * | MIC 62.5 | Methicillin | [91] | |

| Pakistan | L | MeOH | ADM | Aspergilus niger 0198 | IZ 13.29 ± 0.72 | Terbinafine | [98] | |

| Pakistan | L | MeOH | ADM | Aspergilus flavus 0064 | IZ 61.06 ± 1.10 | Terbinafine | [98] | |

| Pakistan | L | MeOH | ADM | Aspergilus fumigates 66 | IZ 31.9 ± 0.53 | Terbinafine | [98] | |

| Pakistan | L | MeOH | ADM | Rhizoctonia solani 18619 | IZ 100 ± 0.00 | Terbinafine | [98] | |

| India | L | DCM | PDB | Alternaria alternata | IZ 28 | na | [125] | |

| India | L | DCM | PDB | Cochliobolus lunatus | IZ 14 | na | [125] | |

| India | R | MeOH | AWDM | Candida albicans 3017 | IZ 14.4 ± 1.6 mm | Fluconazole | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH | AWDM | Candida krusei | IZ 8.9 ± 1.1 mm | Fluconazole | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH | AWDM | Candida glabrata 3814 | IZ 12.9 ± 0.8 mm | Fluconazole | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH | AWDM | Cryptococcus marinus 1029 | IZ 14.4 ± 1.6 mm | Fluconazole | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH | AWDM | Aspergillus niger 9933 | IZ 20.1 ± 1.2 mm | Fluconazole | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH | AWDM | Aspergillus brasiliensis 1344 | IZ 21.0 ± 1.0 mm | Fluconazole | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH | AWDM | Aspergillus flavus 9607 | IZ 25.9 ± 0.9 mm | Fluconazole | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH | AWDM | Rizopus oryzae | IZ 31.5 ± 0.78 mm | Fluconazole | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH | AWDM | Epidermophyton floccosum 7880 | IZ 28.2 ± 1.2 mm | Fluconazole | [100] | |

| India | R | MeOH | AWDM | Microsporum gypseum 2819 | IZ 29.8 ± 0.77 mm | Fluconazole | [100] | |

| India | L | EtOH | DDM | Candida albicans ATCC10231 | IZ 00 mm | Miconazole | [101] | |

| India | L | HX | AWDM | Aspergillus niger MTCC 4325 | MIC > 1000 | Nystatin | [102] | |

| India | L | DCM | AWDM | Aspergillus niger MTCC 4325 | MIC > 1000 | Nystatin | [102] | |

| India | L | MeOH | AWDM | Aspergillus niger MTCC 4325 | MIC 1000 | Nystatin | [102] | |

| India | L | HX | AWDM | Candida albicans MTCC 4748 | MIC 500 | Nystatin | [102] | |

| India | L | Chl | AWDM | Candida albicans MTCC 4748 | MIC 250 | Nystatin | [102] | |