Abstract

Random minitransposon mutagenesis was used to identify genes involved in the survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica within eukaryotic cells. One of the mutants which exhibited a reduced ability to survive intracellularly harbored a minitransposon insertion in a locus (ris) which displays a high degree of homology to two-component regulatory systems. This system exhibited less than 25% amino acid sequence homology to the only other two-component regulatory system described in Bordetella spp., the bvg locus. A risA′-′lacZ translational fusion was constructed and integrated into the chromosome of B. bronchiseptica. Determination of β-galactosidase activity under different environmental conditions suggested that ris is regulated independently of bvg and is optimally expressed at 37°C, in the absence of Mg2+, and when bacteria are in the intracellular niche. This novel regulatory locus, present in all Bordetella spp., is required for the expression of acid phosphatase by B. bronchiseptica. Although catalase and superoxide dismutase production were unaffected, the ris mutant was more sensitive to oxidative stress than the wild-type strain. Complementation of bvg-positive and bvg-negative ris mutants with the intact ris operon incorporated as a single copy into the chromosome resulted in the reestablishment of the ability of the bacterium to produce acid phosphatase and to resist oxidative stress. Mouse colonization studies demonstrated that the ris mutant is cleared by the host much earlier than the wild-type strain, suggesting that ris-regulated products play a significant role in natural infections. The identification of a second two-component system in B. bronchiseptica highlights the complexity of the regulatory network needed for organisms with a life cycle requiring adaptation to both the external environment and a mammalian host.

Bordetella bronchiseptica is a respiratory pathogen that causes diseases in many warm-blooded animals (28). B. bronchiseptica and other Bordetella spp. produce several virulence factors which have been implicated in bacterial attachment and colonization, such as filamentous hemagglutinin, pertactin, and fimbriae, and others, such as the dermonecrotic toxin and the adenylate cyclase hemolysin (32, 37, 42, 43), which seem to be responsible for tissue damage (35, 57), suppression of antibody responses (39), and alteration of host clearance mechanisms (25). The expression of most of the virulence genes is coordinately regulated at the transcriptional level by the bvg (for Bordetella virulence gene) locus in response to environmental signals, such as changes in temperature and the presence of nicotinic acid or MgSO4 (52, 72). This locus encodes two proteins, BvgS and BvgA, which are the environmental sensor and transcriptional activator, respectively, of a two-component regulatory system.

In recent years, several reports have demonstrated the capacity of different Bordetella spp. to invade and survive within epithelial cells (22, 23, 61, 63), dendritic cells (33, 34), and macrophages and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (9, 25, 60, 66). Persistence in a cellular reservoir might allow bacteria to escape from host clearance mechanisms and might also favor a chronic course of infection (7, 30, 57, 69); the bacteria would also be located in an environment rich in nutrients and devoid of competing microorganisms (24).

The processes employed by eukaryotic cells to kill intracellular microorganisms have been extensively characterized (40). However, bacterial genes involved in resistance to intracellular killing and the regulation of such genes are less well characterized (11). In contrast to other Bordetella spp., in which intracellular survival seems to be dependent on bvg-activated products (7, 22, 25, 60), both wild-type and bvg-negative B. bronchiseptica strains are able to invade and survive within eukaryotic cells (33, 34, 61, 63). In addition, recent studies have suggested that, at least in macrophages, bvg-negative mutants may have a selective advantage for long-term survival (7). This suggests that the synthesis of a product(s) involved in intracellular survival might be independent of, or repressed by, the bvg locus.

To identify genes encoding proteins involved in the intracellular survival process, bacterial mutants impaired in survival were generated by random minitransposon mutagenesis. This approach led to the identification of a novel two-component regulatory system which is present in all Bordetella spp. and is required for bacterial resistance to oxidative stress, production of acid phosphatase, and in vivo persistence in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

B. bronchiseptica BB7866 (a spontaneous ΔbvgS avirulent-phase derivative of BB7865 [31]), Bordetella pertussis Tohama I (73) and BP338 (72), Bordetella avium 35086 (Culture Collection of the University of Göteborg, Göteborg, Sweden), and Bordetella parapertussis 15311 and MS/180 (71) were used throughout this work. Bordetellae were grown at 25, 30, or 37°C on Bordet-Gengou (BG) agar base (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 1% glycerol and 10% (vol/vol) defibrinated horse blood and in SS-X broth (65). SS-X broth containing 20 mM MgSO4 instead of NaCl (SS-C) was used to downregulate bvg-activated products.

Escherichia coli SM10(λpir) (50) was used as a donor strain for the conjugative transfer of pUT::mini-Tn5Km2 (18) and pBSL204::miniTn5Tc (4), whereas E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene) was used as the recipient strain for cloning experiments utilizing the vector pUC18Not (36). E. coli Q358(pR751::Tn813) (64) was used for the in vivo transfer of the Kmr cassette into the spontaneous nalidixic acid- and rifampicin-resistant virulent strain BB7865. E. coli strains were grown in or on Luria-Bertani broth or agar (58).

Generation of mutants impaired in intracellular survival ability.

Random minitransposon mutagenesis of B. bronchiseptica with mini-Tn5Km2 was performed as described by Herrero et al. (36). In brief, the donor strain, E. coli SM10(λpir) containing pUT::mini-Tn5Km2, and the recipient strain, BB7866, were mixed in a 1:1 ratio in 0.7% saline and incubated overnight on BG agar. Colonies were collected and suspended in 0.7% saline, and appropriate dilutions were plated onto SS-X agar supplemented with kanamycin at 50 μg/ml (allowing selection for the minitransposon) and cephalexin at 50 μg/ml (allowing negative selection for the donor E. coli). The presence of insertion mutants resulting from cointegration events was excluded by their sensitivity to ampicillin (the marker of the suicide vector).

In vivo transfer of the Kmr cassette into the bvg-positive strain BB7865 and complementation studies.

The Kmr cassette, inserted into the avirulent strain BB7866 ris, was transferred into the virulent strain BB7865 (Nalr Rifr) by the in vivo transfer technique described by Smith and Walker (64). Briefly, E. coli Q358(pR751::Tn813), which contains the conjugative plasmid pR751, harboring the cointegrate-forming transposon Tn813, was conjugally mated with BB7866 ris, inducing the transfer of the plasmid into BB7866 ris. The transposase encoded by Tn813 catalyzes the permanent cointegration of the plasmid into the chromosome. This strain (resistant to trimethoprim at 50 μg/ml and to kanamycin at 50 μg/ml) was then mated with BB7865 (Nalr Rifr). The chromosomally integrated tra genes of pR751 promote chromosome transfer. The Kmr cassette was thus transferred to the recipient strain, and transconjugants were selected by their resistance to rifampin at 100 μg/ml and to kanamycin at 50 μg/ml. Correct integration was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). Kmr cassette insertion into BB7865 ris and BB7866 ris was complemented by chromosomal insertion of the ris locus via pBSL204::miniTn5Tc containing the 4.1-kb NotI fragment of pHJ2, thereby generating BB7865 ris::Tn5Tc-ris+ and BB7866 ris::Tn5Tc-ris+.

Tissue culture methods and invasion assays.

B. bronchiseptica insertion mutants were tested for their ability to survive in the spleen dendritic cell line CB1 (54) and the macrophage-like cell line J774A.1 (ATCC TIB 67). Dendritic cells were maintained in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (Sigma Chemie GmbH, Deisenhofen, Germany) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum and 5 mM glutamine (GIBCO Laboratories, Eggenstein, Germany), and cell line J774A.1 was maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 4.5 g of glucose (Sigma) per liter, 10% fetal calf serum, 5 mM glutamine, and 1.5 g of NaHCO3 per liter, both in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were seeded at a concentration of approximately 5 × 104 per well in 24-well tissue culture plates (Inter Med NUNC, Roskilde, Denmark) and infected for 2 h (CB1 cells) or 30 min (J774A.1 cells), and invasion assays were then performed as previously described (33, 34).

DNA manipulations.

Standard methods were used for plasmid purification, agarose gel electrophoresis, ligation, transformation, and restriction analysis (58). Restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from New England Biolabs (Schwalbach, Germany). DNA purification from agarose gels was performed with a Jet Sorb Gel Extraction Kit (Genomed, Bad Oehnhausen, Germany). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by using an Applied Biosystems 394-8 DNA synthesizer. Colony blotting was carried out by transferring bacteria from agar plates to Biodyne A nylon membranes (Pall, Dreieich, Germany), which were processed according to the procedure of Sambrook et al. (58). PCR amplification of the risA and the risS genes from total DNA of different Bordetella spp. was performed with DNA polymerase MobiTaqK (MoBiTec, Göttingen, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, using the primer pairs 5′-GTGAACACCCACTAGCCGCTGGCTT-3′-5′-CAAGGTTTCTGAACAGTCTGCGCATG-3′ and 5′-TGGCGGCAGTTGACCTAATG-3′-5′-TCAAGCCCTAAATTCTACGCT-3′, respectively.

Cloning of the two-component system and DNA sequence analysis.

To clone the minitransposon and flanking DNA sequences, chromosomal DNA was digested with a restriction endonuclease for which there existed a cleavage site flanking the gene coding for kanamycin resistance (either NotI or EcoRI) and ligated with pUC18Not. After transformation of the ligation mixture into E. coli XL1-Blue, transformants which were resistant to ampicillin (pUC18Not marker) and kanamycin (mini-Tn5 marker) were selected. To clone the full operon, a gene library was generated by cloning NotI-digested chromosomal DNA from BB7866 into pUC18Not. The resulting recombinant clones of E. coli XL1-Blue were screened, using the 1.2-kb digoxigenin (DIG)-labelled NotI-EcoRI fragment of pHJ1 (see Results) as a probe. A positive clone, containing a hybrid plasmid (pHJ2) with the 4.1-kb NotI fragment spanning the insertion site, was identified. Sequencing was performed by the method of Sanger et al. (59), using a Taq Dyedeoxy Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (ABI Prism; Applied Biosystems) and an automated sequencer (model 373; Applied Biosystems). Homology searches were conducted with the FASTA program (55).

Construction of a risA′-′lacZ fusion.

For the construction of a risA′-′lacZ fusion, a PCR-amplified (using the primers 5′-CGGAATTCACGCGCACCCAGCCAG-3′ and 5′-GCGCAGCCCGGGATCATCGTCGAC-3′) EcoRI-SmaI fragment containing 732 bp of the upstream sequence of risA and 76 bp of the risA gene was cloned into pUJ9 (18). Then, the transcriptional terminators of the rrnB gene, T1 and T2, present in pKK232-8 (10) were amplified by PCR as a 313-bp fragment and inserted upstream of the fusion to prevent transcriptional read-through from promoters located upstream of the integration site. The cassette encompassing the transcriptional terminators and the fusion was cloned as a NotI fragment into pUT::mini-Tn5Km2. The minitransposon was then inserted into the chromosomes of BB7865 and BB7866, thereby generating BB7865 risA′-′lacZ and BB7866 risA′-′lacZ, respectively. Three recombinant strains harboring the insertion in different chromosomal sites which did not affect the growth characteristics of the bacterium were selected for further analysis. β-Galactosidase activity was generally quantified by the method of Miller (48). To achieve a higher detection sensitivity, enabling the determination of the β-galactosidase produced by intracellular bacteria, the β-Gal Reporter Gene Assay Kit (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, cells were infected as described above, and 2 or 24 h after gentamycin treatment, the monolayers were lysed with H2O and the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation. One aliquot was taken to determine the number of bacteria (CFU), and the rest of the cells were lysed and the amount of β-galactosidase present in the sample (in femtograms per CFU) was determined. The enzymatic activities produced by bacteria grown in tissue culture medium and in SS-X medium were measured as controls.

Southern blot analysis.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated by using a genomic DNA purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), digested with either EcoRI or NotI, separated on 0.7% agarose gels, and transferred to Pall Biodyne B nylon membranes (58). The DNA was probed with DIG-labelled oligonucleotides (DIG Oligonucleotide 3′-End Labelling Kit; Boehringer) that were complementary to the O end (5′-GCCGCACTTGTGTATAAGAGTC-3′) and the I end (5′-GGCCAGATCTGATCAAGCGACA-3′) of the minitransposon (18). After hybridization was performed by using a DIG Luminescent Detection Kit for Nucleic Acids (Boehringer), the light emissions of bound probes were recorded on Kodak X-ray film.

Northern blot and RACE analysis.

Total RNA was isolated by using a total RNA isolation kit from Qiagen. RNA (15 μg) was subjected to electrophoresis in a denaturing agarose-formaldehyde gel and transferred to Pall Biodyne B nylon membranes (58). A 630-bp BspEI-SalI risA internal DNA fragment was used as a probe. Hybridization was performed at 42°C in a solution containing 50% formamide, 1× Denhardt’s solution, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 8× SSC (1× SSC is 150 mM sodium chloride and 15 mM sodium citrate), 10% dextran sulfate, and 100 μg of salmon sperm DNA per ml. The blot was washed twice in 2× SSC–0.1% SDS for 15 min at 50°C and twice in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS for 15 min at room temperature and then autoradiographed for 24 h.

For determination of the transcriptional start site, the RNA was analyzed with a 5′-3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) system (Boehringer). Briefly, after reverse transcription with the primer 5′-GGCCTTGGCGGTCAGCATGATGAT-3′, which hybridizes to positions 249 to 273 of the risA gene, the cDNA was 3′ dA tailed and PCR amplified with an oligo(dT) primer and a nested primer (5′-AGGAGATCGCGCAGTCGGGGATCAT-3′) complementary to positions 50 to 74 of the risA gene. The resulting product was subsequently cloned and sequenced.

Urease, motility, acid phosphatase, and SOD determinations.

Urease and motility were determined as previously described (46, 74). For acid phosphatase determinations, bacteria were harvested in the late exponential phase, cell pellets were disrupted by using a French press, the lysates were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were tested for phosphatase activity by a modification of the method of Dassa et al. (17). For superoxide dismutase (SOD) determinations, bacterial cells were disrupted by using a French press and the lysates, each containing 100 to 200 μg of protein, were loaded onto a 10% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel, electrophoresed at 80 V, and assayed for SOD activity as described by DeShazer et al. (19).

Sensitivity to oxidative stress.

Susceptibility to paraquat (methyl viologen; Sigma) was determined by a disk diffusion test (11). Overnight cultures of strains BB7865 and BB7866, the ris mutants, and the corresponding ris complementation strains were diluted in saline, and 106 cells of each were plated onto SS-X and SS-C agar. A filter (0.22-μm pore size) soaked in 10 mM paraquat in sterile water was centered onto each plate, and the bacteria were incubated 48 h. The zone of growth inhibition on each plate was determined in two axes relative to the disk, and the averages were calculated. To determine bacterial sensitivity to H2O2, bacterial suspensions were adjusted to an A600 of 0.1 in SS-X broth, H2O2 was added to a final concentration of 1 or 5 mM, and samples were further incubated at 37°C. Aliquots were taken after 0, 15, and 30 min, diluted, and plated to determine the number of viable bacteria (CFU) with respect to the inoculum.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

French press lysates were separated by isoelectrofocusing on a pH gradient ranging from 3 to 10 in capillary gels, using a Mini-Protean II 2-D cell (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). After separation of proteins according to their isoelectric points in the first dimension, they were further separated in a second dimension by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (41), and protein spots were visualized by silver staining (Bio-Rad).

In vivo colonization studies.

Approximately 106 bacteria were resuspended in 1% Casamino Acids in phosphate-buffered saline and administered intranasally to 4-week-old female BALB/c mice. Groups of animals were sacrificed at 2 h and at 4, 8, 14, and 21 days after challenge (four mice per time point). Their lungs were homogenized by using a Polytron PT 1200 homogenizer (Kinematica, Lucerne, Switzerland), and the numbers of viable microorganisms were determined by plating appropriate dilutions onto BG agar supplemented with cephalexin (50 μg/ml).

Statistical analysis.

The statistical significance of the results has been evaluated by the Students t test, using Statgraphic Plus for Windows version 2.0 software (Statistical Graphic Corp.); differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence data for the ris locus of B. bronchiseptica BB7866 have been submitted to the EMBL database and appear under accession no. Z97065.

RESULTS

Identification of a second two-component regulatory system in B. bronchiseptica.

Survival of B. bronchiseptica within eukaryotic cells is bvg independent (33, 34, 61, 63). Therefore, to facilitate the identification of B. bronchiseptica genes which are involved in intracellular survival, a bvg-negative background was chosen for mutagenesis studies. BB7866, the bvgS deletion derivative of the wild-type strain BB7865, was randomly mutagenized by using a minitransposon. Approximately 1,000 Kmr transconjugants with stable integration of the minitransposon were generated. The insertion mutants that were able to conserve the growth properties of the parental strain in liquid medium were screened for their ability to survive within CB1 cells. A BB7866 derivative that exhibited a moderate (32%) but statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) reduction in intracellular survival capacity after 24 h of infection was selected. This clone was further characterized by Southern blot analysis.

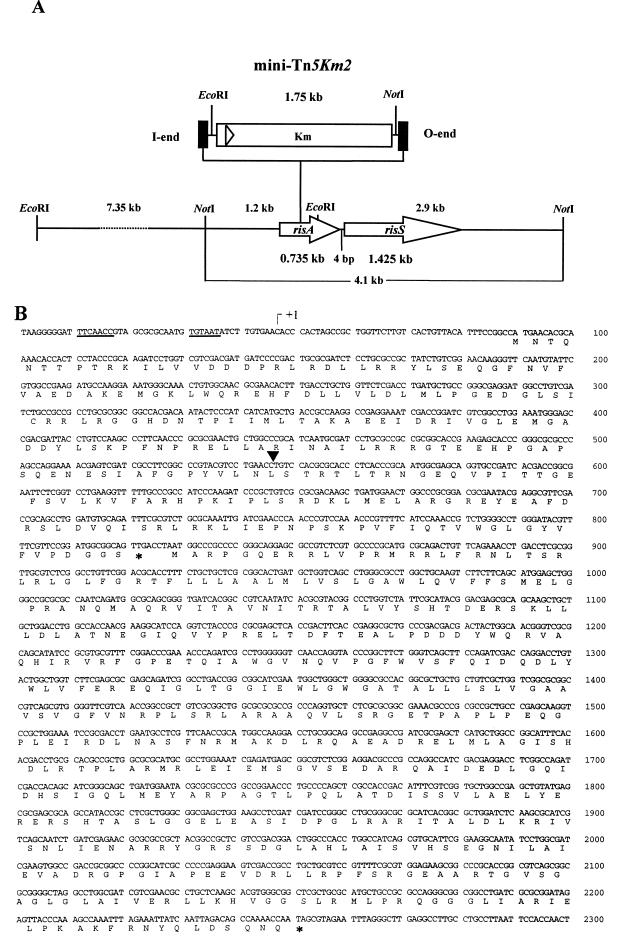

The cassette present in the minitransposon coding for resistance to kanamycin is flanked by the sequences recognized by the endonucleases EcoRI and NotI. Therefore, total DNA was digested with either EcoRI or NotI, separated in agarose gels, and analyzed by Southern blotting with DIG-labelled oligonucleotides specific to the mini-Tn5 I and O ends, respectively (data not shown). The size of the EcoRI and NotI fragments containing the Kmr cassette and the flanking Bordetella chromosomal region established that mini-Tn5Km2 was inserted within a 4.1-kb NotI fragment (Fig. 1A). Then, a 3.0-kb NotI fragment containing the Kmr cassette together with flanking chromosomal DNA (1.2 kb) was cloned into the NotI site of pUC18Not, thereby generating pHJ1. DNA sequence analysis revealed that the minitransposon was integrated into an open reading frame (ORF) encoding a product that exhibits a high degree of homology to the NH2-terminal regions of response regulators from bacterial two-component regulatory systems (Fig. 1B). This gene, which is distinct from bvg, was designated risA (for regulator of intracellular stress response).

FIG. 1.

(A) Linear restriction map of the ris locus present in B. bronchiseptica BB7866. The insertion site of mini-Tn5Km2 in risA is indicated. (B) Nucleotide sequence and predicted translation products of the ris locus. The transcriptional start site identified by RACE analysis (+1), the putative promoter consensus sequences (underlined), the position of the transposon insertion (arrowhead), and the stop codons are indicated.

Most of the two-component systems are encoded by an operon in which the response regulator is found upstream and the second component, the sensor kinase, is located downstream. To clone the full operon, a gene library was generated by cloning NotI-digested chromosomal DNA from BB7866 into pUC18Not. The resulting recombinant clones were screened with the 1.2-kb NotI-EcoRI fragment of pHJ1 as a probe. A positive clone which contained a hybrid plasmid (pHJ2) with the 4.1-kb NotI fragment spanning the insertion site was identified. The pHJ2 insert contains both risA and, 4 bp downstream, a second ORF, designated risS, encoding a product with homology to sensor kinases (Fig. 1B).

Northern blot analysis confirmed that risA and risS are cotranscribed in a bicistronic mRNA of 2.42 kb (data not shown). In addition, the small distance between the two genes suggests that the expression of the corresponding proteins is coupled at the translational level. The analysis by RACE allowed the estimation of the position of the transcriptional start site at nucleotide −43. No typical rho-independent transcription termination site (70) was observed downstream of risS.

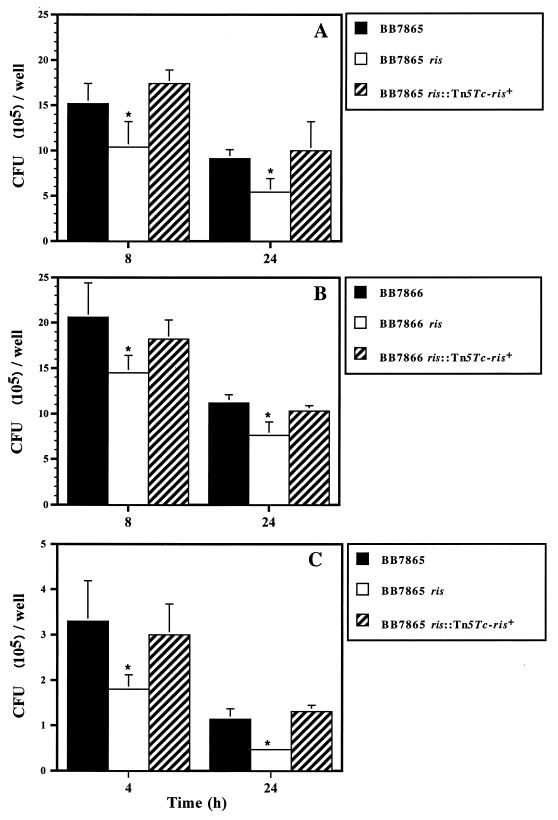

To assess the role of the ris locus in a bvg-positive background, the mutation present in BB7866 ris was transferred into BB7865 by an in vivo transfer technique (64). Both BB7865 ris and BB7866 ris exhibited moderate (41 and 32%, respectively) but statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) reductions in intracellular survival capacities, compared to those of the parental control strains, after 24 h of infection (Fig. 2A and B). Since professional phagocytes constitute the first line of defense against microbial pathogens, the capacities of BB7865 and its ris derivative to survive in the macrophage-like cell line J774A.1 were investigated. A clear reduction in the intracellular survival of the mutant strain was also observed in this cellular system (Fig. 2C) after 4 and 24 h of infection (45 and 59%, respectively). To further confirm the role of products encoded by the ris locus in the observed phenotype, the ris mutant strains were complemented under physiologic monocopy conditions by transferring the 4.1-kb NotI fragment of pHJ2 into the chromosome via a second minitransposon. The presence of the ris locus reestablished the intracellular survival capacities of the ris mutants (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

B. bronchiseptica ris mutants exhibit reduced intracellular survival capacities. CB1 (A and B) and J774A.1 (C) cells were infected with B. bronchiseptica strains and their corresponding ris derivatives, and the numbers of viable intracellular bacteria were determined at different time intervals. The complementation of ris-deficient strains with the intact ris locus in monocopy reestablished the phenotype to wild-type levels. The results are averages of three independent determinations; standard errors of the means are indicated by vertical lines. Differences between wild-type and recombinant strains were significant at P ≤ 0.05 (★).

Sequence homology of the ris products and other two-component regulatory systems.

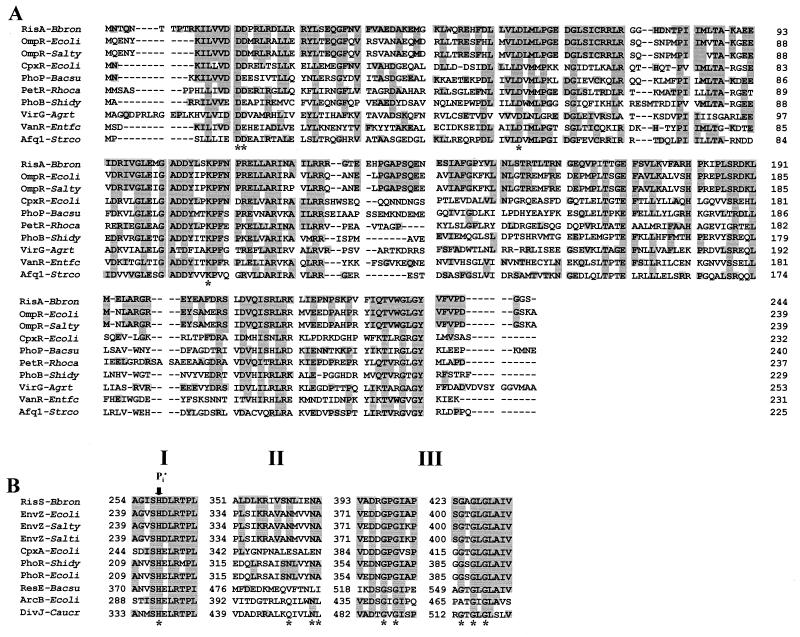

The risA (0.735-kb) and risS (1.425-kb) genes encode proteins with estimated molecular masses of 27.7 and 52.6 kDa and predicted isoelectric points of 6.46 and 7.14, respectively. The GC contents of risA (61.4%) and risS (67.4%) are similar to the overall GC content of the B. bronchiseptica chromosome (64%), which argues against the recent acquisition of the ris genes by B. bronchiseptica. The risA and risS ORFs, as well as their products, were analyzed for homology to other genes and their products by using the FASTA program (55) with a gap extension penalty of 4. RisA and RisS exhibited the highest degree of homology to E. coli OmpR and EnvZ, with 66.5% (236-amino-acid overlap) and 29.5% (437-amino-acid overlap) identity at the protein level, respectively (Fig. 3). RisA showed the highest degree of homology to OmpR in the NH2-terminal region of the protein, which is conserved among response regulators and contains the phosphorylation site (Asp at position 60) as well as the aspartate residues necessary for the generation of an acidic pocket (Asp at positions 17 and 18) and the conserved lysine at position 110 (53). RisS showed the highest degree of homology to the conserved COOH-terminal region of EnvZ and exhibited homology to other sensor kinases in the three functional regions, whereas the overall degree of similarity was relatively low (38, 53, 67). The predicted autophosphorylation site was present in region I (His at position 258), and the AsnXXXAsnAla motif, which appears to be required for phosphotransfer and is common to all members of the EnvZ family (51), was present in region II (positions 360 to 365). Finally, in region III, two conserved glycine-rich sequences (GXG and GXGXG) (53) and a conserved phenylalanine at position 412 (39) were observed. The identity between EnvZ and RisS in the predicted periplasmic domains was only 15% (126-amino-acid overlap), in contrast to an overall identity of 29.5%, suggesting that different environmental signals might be sensed by the periplasmic domains of EnvZ and RisS. The levels of homology between RisA-RisS and the components of the only other known Bordetella response regulator system, BvgA-BvgS, are 23% (RisA versus BvgA) and 25% (RisS versus BvgS), respectively. It has been described that the overlap between the termination and initiation codons observed in ompR-envZ favors translational coupling, thereby allowing an optimal molar ratio between the two proteins (14, 44). This supports the hypothesis that the ATG located 4 bp downstream of the risA stop codon is the start codon of risS.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of RisA-RisS to other two-component regulatory systems. (A) RisA of B. bronchiseptica (Bbron) showed homology to the response regulators OmpR of E. coli (Ecoli) and S. typhimurium (Salty), CpxR of E. coli, PhoP of Bacillus subtilis (Bacsu), PetR of Rhodobacter capsulatus (Rhoca), PhoB of Shigella dysenteriae (Shidy), VirG of Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Agrt), VanR of Enterococcus faecium (Entfc), and Afq1 of Streptomyces coelicolor (Strco). Dashes indicate gaps in amino acid sequence for optimal alignment. (B) RisS exhibited homology in the three functional regions to the histidine kinases EnvZ of E. coli, S. typhimurium, and Salmonella typhi (Salti), CpxA of E. coli, PhoR of Shigella dysenteriae and E. coli, ResE of Bacillus subtilis, ArcB of E. coli, and DivJ of Caulobacter crescentus (Caucr). The conserved functional residues are indicated by asterisks, identical residues are shaded, and the putative autophosphorylation site is indicated (Pi).

Regulation of ris expression.

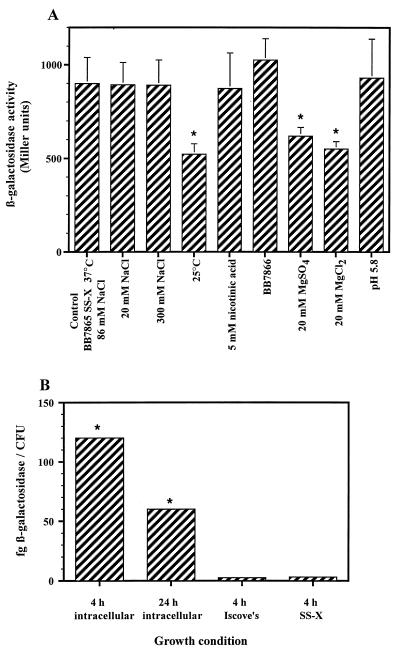

To investigate which environmental signals are involved in the activation of ris, a translational fusion between risA and the lacZ reporter gene was generated. The resulting construct was integrated into the chromosomes of BB7865 and BB7866 in a single copy. Due to the high degree of similarity between ris and other osmosensory two-component systems (e.g., ompR-envZ), we first determined whether increments in osmolarity resulted in modification of the amounts of β-galactosidase expressed by the recombinant strains. Supplementation of SS-X broth with NaCl in concentrations ranging between 20 and 300 mM did not result in a significant change in expression of the reporter gene in either BB7865 risA′-′lacZ or BB7866 risA′-′lacZ (Fig. 4A). This and the lack of alteration in the outer membrane profile between the parental strains and their ris mutants (data not shown) suggest that the ris locus is not a homolog of the ompR-envZ locus in B. bronchiseptica.

FIG. 4.

Regulation of ris expression. (A) The β-galactosidase activity of B. bronchiseptica BB7865 risA′-′lacZ grown at 37°C in SS-X broth supplemented with increasing NaCl concentrations, at 25°C in SS-X broth, at 37°C in SS-X broth containing 5 mM nicotinic acid, at 37°C in SS-C broth containing 20 mM MgSO4 or MgCl2, or at 37°C in SS-X broth at pH 5.8 was determined. BB7866 risA′-′lacZ was grown at 37°C in SS-X broth. The results are mean values of three independent assays performed with independent strains harboring risA′-′lacZ integrated at different sites. Standard errors of the mean are indicated by vertical lines; differences with BB7865 risA′-′lacZ grown at 37°C in SS-X broth were significant at P ≤ 0.05 (★). (B) Determination of the β-galactosidase activity produced by B. bronchiseptica BB7865 risA′-′lacZ recovered 4 and 24 h after infection of CB1 cells. The results are means of data from three independent assays; standard errors of the mean were less than 5%. Differences with the strain BB7865 risA′-′lacZ grown in either Iscove’s or SS-X medium were significant at P ≤ 0.05 (★).

To assess the influence of bvg on ris expression, BB7865 risA′-′lacZ was grown under bvg-modulating conditions, such as in SS-X medium at 25°C or in the presence of either 5 mM nicotinic acid or 20 mM MgSO4 at 37°C. Expression of β-galactosidase in BB7865 risA′-′lacZ was reduced 42% after growth at 25°C and 31% in the presence of MgSO4. However, the enzymatic activity was not reduced in BB7865 ris′-′lacZ grown in the presence of nicotinic acid or in the bvgS avirulent strain BB7866 ris′-′lacZ. This indicates that bvg has no influence on ris expression and that the observed effect may be attributed to a downregulation at low temperatures. A similar downregulation of risA was observed when bacteria were grown in the presence of 20 mM MgCl2 instead of MgSO4. This suggests that Mg2+ has an effect on ris expression. It is likely that the intraphagosomal Mg2+ concentration is low enough to enhance ris expression, as occurs in Mg2+-repressed intracellularly activated genes of Salmonella spp. (26, 27). β-Galactosidase activity was not affected when bacteria were grown at pH 5.8. Although phagosome acidification has been shown to stimulate gene expression in many intracellular pathogens, the environmental parameters of B. bronchiseptica-containing phagosomes have not yet been elucidated. To establish the influence of the eukaryotic cell environment on ris expression, the level of β-galactosidase produced during bacterial infection of CB1 cells was determined. The expression of the reporter gene was increased by 48- and 24-fold after 4 and 24 h of infection, respectively (Fig. 4B). This clearly demonstrates that the ris locus is activated upon bacterial infection of eukaryotic cells.

Identification of the ris locus in other Bordetella spp.

To assess whether the ris regulatory system is conserved among different Bordetella spp., DNA from B. avium, B. parapertussis, B. pertussis, and B. bronchiseptica was digested with EcoRI and analyzed by Southern blotting with a probe encompassing a 500-bp internal fragment of risA. A band of approximately 8.6 kb that specifically reacted with the probe was observed in all species (data not shown). The DNA was also used as a template in a PCR with primers based on the 5′ and 3′ ends of risA and risS. A 735-bp and a 1,425-bp fragment, respectively, were amplified in all tested strains; sequence analysis of the PCR products revealed 100% identity between B. bronchiseptica (strain BB7866), B. avium (strain 35086), and B. parapertussis (strains MS/180 and 15311) risA fragments and a single conservative exchange (C to A) in B. pertussis (strains BP338 and Tohama I) at position 546 of risA. When the risS gene was analyzed, 100% identity between B. bronchiseptica (strain BB7866) and B. parapertussis MS/180 was found, whereas one exchange was observed in B. parapertussis 15311 and B. pertussis (strains BP338 and Tohama I), at position 1,414 (C to G), and two exchanges were evident in B. avium 35086, at positions 1414 (C to G) and 1344 (conservative C-to-G exchange) (data not shown). The overall sequence data (EMBL accession no. Z97065, AJ224798, AJ224799, AJ224800, AJ224801, AJ224802, AJ224803, and AJ224804) demonstrate that the ris locus is highly conserved among different Bordetella spp.

Effect of the ris mutation on protein expression by B. bronchiseptica.

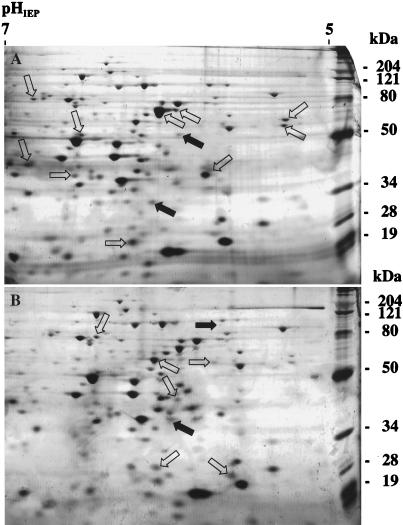

Two-component systems are generally involved in the coordinate regulation of several gene products (51, 53). Therefore, their inactivation usually results in a highly pleiotropic effect. In an attempt to further characterize the role of the Ris system in B. bronchiseptica physiology, whole-cell protein extracts from BB7866 and its ris derivative were analyzed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. The comparative analysis showed that proteins with approximate molecular masses of 80, 76, 68, 62, 53, 50, 39, 36, 30, and 16 kDa are downregulated in the ris mutants, whereas others, of 95, 73, 58, 56, 42, 36, 26, and 20 kDa, seem to be repressed by ris (Fig. 5). This suggests that the ris locus has a significant role in the regulation of B. bronchiseptica gene expression.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of the protein expression patterns of B. bronchiseptica BB7866 and BB7866 ris by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. French press lysates of BB7866 (A) and BB7866 ris (B) were separated by isoelectrofocusing in the first dimension and by sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the second dimension; then proteins were identified by silver staining. Protein spots detected in larger amounts in one strain are indicated by open arrows, whereas those detected in only one strain are indicated by filled arrows. The positions of molecular mass markers are indicated on the right.

Effect of ris mutation on the expression of bvg-independent and bvg-repressed B. bronchiseptica products.

Intracellular survival has been shown to be unaffected, or even favored, in bvg-negative mutants (33, 34, 61, 63). This has led to the hypothesis that bvg-independent or bvg-repressed gene products play a role in intracellular survival. Therefore, the ris regulatory locus may be involved in the activation of bvg-independent or bvg-repressed products. Urease production and motility are characteristic phenotypes of B. bronchiseptica which are repressed by bvg and, additionally, regulated by temperature (33, 34, 61, 63). Neither urease production nor motility was affected in the ris mutants BB7865 ris and BB7866 ris (data not shown). This suggests that the expression of the urease and motility genes is ris independent.

We have previously identified an acid phosphatase that is produced by B. bronchiseptica, but not by other Bordetella spp. (13), which plays a role in bacterial intracellular survival. The acid phosphatase activity was reduced by 85 and 87% in BB7865 ris and by 49 and 75% in the BB7866 ris mutant when cells were grown at 37 and 30°C in SS-X, respectively (Table 1). The phosphatase activity was restored in the ris mutants by the chromosomal insertion of the ris locus (Table 1). These complementation studies strongly suggest that acid phosphatase expression is regulated in response to environmental signals transduced by RisA-RisS.

TABLE 1.

Determination of the acid phosphatase activity present in French press lysates of B. bronchiseptica strains

| Strain | Acid phosphatase activity when grown ona:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37°C

|

30°C

|

|||

| SS-X | SS-C | SS-X | SS-C | |

| BB7865 | 8.3 ± 2.3 | 78.9 ± 4.6 | 112.4 ± 10.0 | 232.2 ± 15.5 |

| BB7865 ris | 9.2 ± 1.2 | 11.6 ± 2.3 | 29.7 ± 1.1 | 31.0 ± 1.3 |

| BB7865 ris::Tn5Tc-ris+ | 17.3 ± 3.0 | 38.8 ± 4.6 | 74.7 ± 14.5 | 140.1 ± 3.0 |

| BB7866 | 67.0 ± 6.0 | 67.5 ± 2.5 | 80.6 ± 5.2 | 181.5 ± 9.3 |

| BB7866 ris | 26.7 ± 4.2 | 34.5 ± 0.4 | 38.5 ± 1.9 | 45.2 ± 1.0 |

| BB7866 ris::Tn5Tc-ris+ | 55.6 ± 1.8 | 57.1 ± 7.1 | 110.78 ± 7.8 | 165.15 ± 20.1 |

The reported results are means of values from three independent assays ± standard errors of the mean and are expressed in milliunits of acid phosphatase activity per milligram of protein.

Sensitivity to oxidative stress of B. bronchiseptica ris.

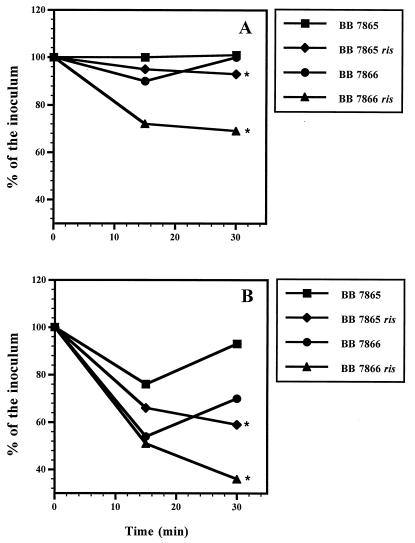

One of the strategies employed by intracellular pathogens to overcome host oxygen-dependent clearance mechanisms (e.g., O2·− and H2O2) is the enzymatic conversion of oxidants by SOD (i.e., conversion of O2·− to H2O2 and O2), catalase, or other oxidoreductases (i.e., conversion of H2O2 to H2O and O2). Therefore, the sensitivity of B. bronchiseptica to killing by increased levels of intracellular superoxide anion radicals generated by the compound paraquat was analyzed (Table 2). The growth of strain BB7865 was inhibited by paraquat when this organism was cultured in SS-X medium, compared to its growth in bvg-repressing SS-C medium and to the growth of strain BB7866 in SS-X. Growth inhibition was increased in both BB7865 ris and BB7866 ris, with respect to the growth of their parental strains, under all growth conditions, and they generally exhibited a higher sensitivity to paraquat on SS-X than on SS-C medium. The complementation of the ris mutants by the chromosomal integration of the ris locus restored resistance to reactive oxygen. To expand these studies, the sensitivity of B. bronchiseptica to H2O2 was analyzed (Fig. 6). The viabilities of strains BB7865, BB7866, and BB7865 ris were not significantly affected by a 30-min exposure to 1 mM H2O2. In contrast, after a similar treatment, the number of viable cells of the mutant strain BB7866 ris was reduced by 30%. When BB7865 and BB7866 were exposed to 5 mM H2O2, reductions of viability were observed after 15 min (25 and 46%, respectively). However, after 30 min, both strains regained viability with respect to the control (100 and 70% of the inoculum, respectively). In contrast, BB7865 ris and BB7866 ris exhibited steady reductions in viability after 30 min of exposure to H2O2 (40 and 64%, respectively).

TABLE 2.

Susceptibility of B. bronchiseptica to paraquat

| Strain | Growth inhibition zone on medium ata:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37°C

|

30°C

|

|||

| SS-X | SS-C | SS-X | SS-C | |

| BB7865 | 5 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| BB7865 ris | 25 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 |

| BB7865 ris::Tn5Tc-ris+ | 8 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| BB7866 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| BB7866 ris | 11 ± 0 | 11 ± 1 | 8 ± 0 | 6 ± 1 |

| BB7866 ris::Tn5Tc-ris+ | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

Growth inhibition is reported in millimeters measured in two axes relative to the disk and averaged ± the standard error of the mean.

FIG. 6.

Sensitivity of B. bronchiseptica to H2O2. Bacteria were exposed to 1 mM (A) or 5 mM (B) H2O2, and the number of viable microorganisms was determined. Results are expressed as the percentage of the initial inoculum and are means of values from three independent experiments; standard errors of the mean were less than 5%. Differences between the parental and the mutant strain were significant at P ≤ 0.05 (★).

These results suggest that ris and bvg are involved in the expression of a product(s) which is required for bacterial resistance to oxidative stress and is necessary for intracellular survival. The initial, reversible reduction in the number of viable bacteria observed after a 15-min exposure of the parental strains to H2O2 further supports the inducible nature of these products. Interestingly, neither catalase nor SOD production was affected in the ris mutants (data not shown). This is in agreement with previous work (20, 29) which suggested that neither sodA nor sodB is essential for intracellular survival of Bordetella spp.

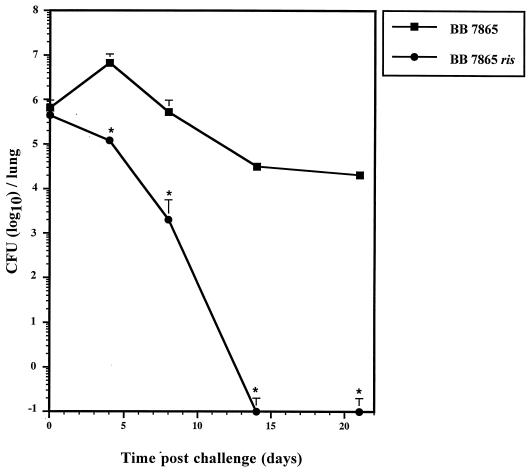

ris mutants exhibit an impaired capacity to persist in the lungs of infected mice.

The contribution of ris-regulated products to both bacterial resistance to oxidative stress and survival in vitro within different cell lines prompted us to investigate the capacity of ris mutants to infect and persist within the host. Mice were infected by the intranasal route with either BB7865 or its ris derivative, and the numbers of viable bacteria present in the lungs were determined at different time intervals (Fig. 7). While the number of microorganisms present in the lungs of mice challenged with BB7865 increased progressively during the first 4 days after infection, the clearance process of the ris mutant started immediately (with an approximately 1.7-order-of-magnitude difference evident after 4 days). Then, the number of CFU recovered from the lungs of mice infected with the parental strain slowly decreased, reaching a plateau at day 14 (approximately 4.5 log units). In contrast, the ris mutant was rapidly eliminated, with the lungs being free of bacteria at day 14 postchallenge.

FIG. 7.

In vivo persistence of BB7865 and BB7865 ris in the lungs. BALB/c mice were infected intranasally with 106 bacteria each. Animals were sacrificed and lungs were taken at 2 h and at 4, 8, 14, and 21 days after infection, and the numbers of viable bacteria per lung were determined. The results are averages of values for four mice; standard errors of the mean are indicated by vertical lines. Differences between animals infected with the wild type and those infected with the mutant strain were significant at P ≤ 0.05 (★).

DISCUSSION

Bacterial survival in a particular niche requires a continuous monitoring of external conditions and the ability to use this information to develop an adaptive response. This response is generally mediated by the up- and/or downregulation of appropriate genes (24, 47). This requirement is very stringent for pathogenic microorganisms whose transmission is not restricted to host-to-host contact, since their infection cycles are characterized by two phases, one within the host and another consisting of bacterial release into the environment (24). Intracellular pathogens should further distinguish between the extracellular and intracellular milieux, which are characterized by different biochemical and physical parameters (e.g., nutrient concentration, pH, osmolarity, etc.).

Many bacterial signal transduction pathways leading to adaptation require two regulatory proteins, a sensor and a transcriptional activator. The bvg locus of B. bronchiseptica encodes one such system, which is responsible for regulating the expression of many virulence factors required during the infection cycle (52, 72). However, the observation that the intracellular survival of B. bronchiseptica is bvg independent (33, 34, 61, 63) suggests that the expression of the required bacterial products is either bvg independent or bvg repressed. We have identified a novel two-component regulatory system (RisA-RisS) which appears to be required for B. bronchiseptica’s resistance to oxidative stress, production of a bvg-repressed acid phosphatase, and in vivo persistence in mice. The ris locus exhibits a high degree of homology to the E. coli ompR-envZ genes, which are involved in osmoregulation (14), and to the Salmonella typhimurium phoPQ genes, which are required for the intraphagosomal activation of virulence genes (6, 49).

There are contrasting results regarding the in vivo modulation of bvg and the overall contribution of bvg-repressed genes to the infection process (1, 2, 8, 15, 16). Beattie et al. reported that the inactivation of the bvg-repressed gene vrg-6 of B. pertussis results in an attenuation in mice and that B. bronchiseptica constitutively expressing bvg colonizes the respiratory tracts of guinea pigs less efficiently (8). In contrast, a recent report suggests that neither the Bvg− phase nor the vrg-6 locus is required for infection of mice by B. pertussis (45). Furthermore, experiments performed in rabbits, using a Bvg+ phase-locked mutant of B. bronchiseptica, showed that the Bvg+ phase is necessary and sufficient for infection and that bvg-repressed genes are downregulated during colonization (1, 2, 15). However, although antibodies against bvg-repressed flagella were not observed after B. bronchiseptica infection of rabbits (15), they were detected after infection of guinea pigs (3). These last data indicate that bvg might be repressed in certain niches within the host. The identification of a new class of bvg-regulated products in B. bronchiseptica also suggests that bvg-intermediate antigens might contribute to the bacterial infection cycle, affecting host responses (16). This would reflect a common feature of pathogenic bacteria, which after moving into a new environment adjust protein synthesis to avoid the extra energetic cost of synthesizing unnecessary products (24, 47). The PhoPQ system of S. typhimurium is inactive in extracellular bacteria, allowing transcription of PhoP-repressed genes that are required for entrance, and is active intracellularly, leading to the transcription of PhoP-activated genes that are important for intracellular survival (5, 6, 49).

The sequential appearance of antibodies against different bvg-regulated virulence factors during infection (32), the sequential activation of virulence genes under permissive conditions (62), and the temperature-dependent regulation of some bvg-repressed genes (46, 74) suggest that bvg is part of a regulatory network in which additional factors are required to fine-tune gene expression during the course of infection. Thus, it is likely that both bvg and additional regulators such as ris interact, influencing the expression of proteins required in the intracellular survival process. Interactions between two-component systems are widely distributed; e.g., in the Pho regulon of Bacillus subtilis, three such systems interact to coordinate the expression of phoPR (68). The results presented here show that ris activation is independent of bvg but that both regulatory systems act antagonistically on the expression of putative survival-relevant products. Temperature and ion (e.g., Mg2+ and SO4−) concentrations may allow B. bronchiseptica to distinguish between the external environment and specific niches within the host. A temperature of 37°C favors ris expression; additionally, in vivo expression of ris is modulated by the Mg2+ concentration, similarly to intracellularly expressed Salmonella genes (26, 27).

The physiopathogenesis of B. bronchiseptica survival within eukaryotic cells has yet to be completely elucidated. The work reported here demonstrates that the ris locus is conserved among all Bordetella spp. However, only B. bronchiseptica can survive within dendritic cells (33, 34), and in contrast to B. pertussis, survival is bvg independent (22, 23, 25, 60). Interestingly, recent studies by Banemann and Gross (7) provide evidence that bvg-negative strains may have a selective advantage to survive intracellularly in macrophages. Paraquat generates intracellular O2·−, which by further reduction and autooxidation can accumulate as toxic hydroxyl radicals, whereas H2O2 is an important component of the respiratory burst and can react with iron or copper ions to also generate hydroxyl radicals (12). The ris mutants are more susceptible to both compounds, suggesting that ris regulates a protein(s) required to survive accumulation of hydroxyl radicals, O2·−, and H2O2. Catalase and SOD production are not affected in the ris mutants (data not shown). This suggests that ris may also regulate the expression of an unknown oxidoreductase which mediates resistance against intracellular killing mechanisms.

Acid phosphatases have been recognized as virulence factors able to improve the intracellular survival capacities of several microorganisms (21, 56). The acid phosphatase produced by B. bronchiseptica also appears to be involved in the intracellular survival process (13). The ris-dependent expression of acid phosphatase further supports a role for the ris locus in the regulation of virulence-associated rather than metabolic genes. Acid phosphatase and resistance to paraquat were shown to be repressed by bvg and to be dependent on ris activation. Whether acid phosphatase is directly involved in the resistance to O2·−, or phosphatase production and resistance to O2·− are dependent on the same regulatory system, remains to be elucidated.

Interestingly, the expression of the ris locus was upregulated when bacteria were infecting eukaryotic cells (Fig. 4B), suggesting a role for ris-regulated products in this stage of the infection process. This hypothesis was further supported by the rapid clearance of the ris mutant observed in mouse colonization studies. These results indicate that ris-regulated products are required for persistent infection and resistance to the nonspecific clearance mechanisms of the innate immune response. Therefore, ris-regulated products may contribute to the persistence and chronic progression of B. bronchiseptica infections. The identification of other ris-dependent products would allow elucidation of the interplay between bvg-dependent and ris-dependent products and would contribute to the overall understanding of the strategies employed by B. bronchiseptica to survive in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge E. Medina for stimulating discussions and critical reading of the manuscript, A. Müller for outstanding technical assistance, and K. N. Timmis for generous support and encouragement.

This work was partially supported by grants from the Lower Saxony-Israel Cooperation Programme, founded by the Volkswagen Foundation (21.45-75/2), the DAAD Acciones Integradas Hispano-Alemanas Programme (314-AI-e-dr), and the Australian National Health and Medical Research council (930123). N.P.W. is the recipient of a University of Wollongong postgraduate research award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akerley B J, Cotter P A, Miller J F. Ectopic expression of the flagellar regulon alters development of the Bordetella-host interaction. Cell. 1995;80:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akerley B J, Miller J F. Understanding signal transduction during bacterial infection. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:141–146. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akerley B J, Monack D M, Falkow S, Miller J F. The bvgAS locus negatively controls motility and synthesis of flagella in Bordetella bronchiseptica. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:980–990. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.980-990.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexeyev M F, Shokolenko I N, Croughan T P. New mini-Tn5 derivatives for insertion mutagenesis and genetic engineering in gram-negative bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:1053–1055. doi: 10.1139/m95-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alpuche Aranda C M, Racoosin E L, Swanson J A, Miller S I. Salmonella stimulate macrophage macropinocytosis and persist within spacious phagosomes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:601–608. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alpuche Aranda C M, Swanson J A, Loomis W P, Miller S I. Salmonella typhimurium activates virulence gene transcription within acidified macrophage phagosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10079–10083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banemann A, Gross R. Phase variation affects long-term survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica in professional phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3469–3473. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3469-3473.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beattie D T, Shahin R, Mekalanos J J. A vir-repressed gene of Bordetella pertussis is required for virulence. Infect Immun. 1992;60:571–577. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.571-577.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bromberg K, Tannis G, Steiner P. Detection of Bordetella pertussis associated with the alveolar macrophages of children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4715–4719. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4715-4719.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brosius J. Plasmid vectors for the selection of promoters. Gene. 1984;27:151–160. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchmeier N, Bossie S, Chen C-Y, Fang F C, Guiney D G, Libby S J. SlyA, a transcriptional regulator of Salmonella typhimurium, is required for resistance to oxidative stress and is expressed in the intracellular environment of macrophages. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3725–3730. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3725-3730.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchmeier N A, Heffron F. Intracellular survival of wild-type Salmonella typhimurium and macrophage-sensitive mutants in diverse populations of macrophages. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.1-7.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chhatwal G S, Walker M J, Yan H, Timmis K N, Guzman C A. Temperature dependent expression of an acid phosphatase by Bordetella bronchiseptica: role in intracellular survival. Microb Pathog. 1997;22:257–264. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comeau D E, Ikenaka K, Tsung K, Inouye M. Primary characterization of the protein products of the Escherichia coli ompB locus: structure and regulation of synthesis of the OmpR and EnvZ proteins. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:578–584. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.578-584.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotter P A, Miller J F. BvgAS-mediated signal transduction: analysis of phase-locked regulatory mutants of Bordetella bronchiseptica in a rabbit model. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3381–3390. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3381-3390.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cotter P A, Miller J F. A mutation in the Bordetella bronchiseptica bvgS gene results in reduced virulence and increased resistance to starvation, and identifies a new class of Bvg-regulated antigens. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:671–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3821741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dassa E, Cahu M, Desjoyaux-Cherel B, Boquet P L. The acid phosphatase with optimum pH of 2.5 of Escherichia coli: physiological and biochemical study. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:6669–6676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis K N. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeShazer D, Bannan J D, Moran M J, Friedman R L. Characterization of the gene encoding superoxide dismutase of Bordetella pertussis and construction of a SOD-deficient mutant. Gene. 1994;142:85–89. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90359-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeShazer D, Wood G E, Friedman R L. Molecular characterization of catalase from Bordetella pertussis: identification of the katA promoter in an upstream insertion sequence. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:123–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dowling J N, Saha A K, Glew R H. Virulence factors of the family Legionellaceae. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:32–60. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.32-60.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewanowich C A, Melton A R, Weiss A A, Sherburne R K, Peppler M S. Invasion of HeLa 229 cells by virulent Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2698–2704. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.9.2698-2704.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ewanowich C A, Sherburne R K, Man S F P, Peppler M S. Bordetella parapertussis invasion of HeLa 229 cells and human respiratory epithelial cells in primary culture. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1240–1247. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1240-1247.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finlay B B, Falkow S. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:210–230. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.2.210-230.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman R L, Nordensson K, Wilson L, Akporiaye E T, Yocum D E. Uptake and intracellular survival of Bordetella pertussis in human macrophages. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4578–4585. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4578-4585.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia del Portillo F, Foster J W, Maguire M E, Finlay B B. Characterization of the micro-environment of Salmonella typhimurium-containing vacuoles within MDCK epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3289–3297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia Vescovi E, Soncini F C, Groisman E A. Mg2+ as an extracellular signal: environmental regulation of Salmonella virulence. Cell. 1996;84:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodnow R A. Biology of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Microbiol Rev. 1980;44:722–738. doi: 10.1128/mr.44.4.722-738.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graeff-Wohlleben H, Killat S, Banemann A, Guiso N, Gross R. Cloning and characterization of an Mn-containing superoxide dismutase (SodA) of Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2194–2201. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2194-2201.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray D F, Cheers C. The steady state in cellular immunity. II. Immunological complaisance in murine pertussis. J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1967;45:417–426. doi: 10.1038/icb.1967.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gross R, Rappuoli R. Pertussis toxin promoter sequences involved in modulation. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4026–4030. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.4026-4030.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gueirard P, Guiso N. Virulence of Bordetella bronchiseptica: role of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4072–4078. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4072-4078.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guzman C A, Rohde M, Bock M, Timmis K N. Invasion and intracellular survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica in mouse dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5528–5537. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5528-5537.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guzman C A, Rohde M, Timmis K N. Mechanisms involved in uptake of Bordetella bronchiseptica by mouse dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5538–5544. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5538-5544.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanada M, Shimoda K, Nakase Y, Nishiyama Y. Production of lesions similar to naturally occurring swine atrophic rhinitis by cell-free sonicated extract of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Jpn J Vet Sci. 1979;41:1–8. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.41.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hewlett E L, Urban M A, Manclark C R, Wolff J. Extracytoplasmic adenylate cyclase of Bordetella pertussis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:1926–1930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.6.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoch J A, Silhavy T J. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horiguchi Y, Matsuda H, Koyama H, Nakai T, Kume K. Bordetella bronchiseptica dermonecrotizing toxin suppresses in vivo antibody responses in mice. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;69:229–234. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90651-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kornfeld S, Mellman I. The biogenesis of lysosomes. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1989;5:483–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.05.110189.002411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leininger E, Ewanowich C A, Bhargava A, Peppler M S, Kenimer J G, Brennan M J. Comparative roles of the Arg-Gly-Asp sequence present in the Bordetella pertussis adhesins pertactin and filamentous hemagglutinin. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2380–2385. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2380-2385.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li J, Fairweather N F, Novotny P, Dougan G, Charles I G. Cloning, nucleotide sequence and heterologous expression of the protective outer-membrane protein P.68 pertactin from Bordetella bronchiseptica. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1697–1705. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-8-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liljestrom P, Laamanen I, Palva E T. Structure and expression of the ompB operon, the regulatory locus for the outer membrane porin regulon in Salmonella typhimurium LT-2. J Mol Biol. 1988;201:663–673. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90465-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez de Tejada G, Cotter P A, Heininger U, Camilli A, Akerley B J, Mekalanos J J, Miller J F. Neither the Bvg− phase nor the vrg6 locus of Bordetella pertussis is required for respiratory infection of mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2762–2768. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2762-2768.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McMillan D J, Shojaei M, Chhatwal G S, Guzman C A, Walker M J. Molecular analysis of the bvg-repressed urease of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Microb Pathog. 1996;21:379–394. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mekalanos J J. Environmental signals controlling expression of virulence determinants in bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.1-7.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller S I, Kukral A M, Mekalanos J J. A two-component regulatory system (phoP phoQ) controls Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5054–5058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller V L, Mekalanos J J. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2575–2583. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2575-2583.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mizuno T, Mizushima S. Signal transduction and gene regulation through the phosphorylation of two regulatory components: the molecular basis for the osmotic regulation of the porin genes. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1077–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monack D M, Arico B, Rappuoli R, Falkow S. Phase variants of Bordetella bronchiseptica arise by spontaneous deletions in the vir locus. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1719–1728. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Msadek T, Kunst F, Rapoport G. Two-component regulatory systems. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 729–745. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paglia P, Girolomoni G, Robbiati F, Granucci F, Ricciardi Castagnoli P. Immortalized dendritic cell line fully competent in antigen presentation initiates primary T cell responses in vivo. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1893–1901. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pearson W R. Rapid and sensitive sequence comparison with FASTP and FASTA. Methods Enzymol. 1990;183:63–98. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)83007-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Remaley A T, Kuhns D B, Basford R E, Glew R H, Kaplan S S. Leishmanial phosphatase blocks neutrophil O2− production. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:11173–11175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roop R M, II, Veit H P, Sinsky R J, Veit S P, Hewlett E L, Kornegay E T. Virulence factors of Bordetella bronchiseptica associated with the production of infectious atrophic rhinitis and pneumonia in experimentally infected neonatal swine. Infect Immun. 1987;55:217–222. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.217-222.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saukkonen K, Cabellos C, Burroughs M, Prasad S, Tuomanen E. Integrin-mediated localization of Bordetella pertussis within macrophages: role in pulmonary colonization. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1143–1149. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.5.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Savelkoul P H, Kremer B, Kusters J G, van der Zeijst B A, Gaastra W. Invasion of HeLa cells by Bordetella bronchiseptica. Microb Pathog. 1993;14:161–168. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scarlato V, Arico B, Prugnola A, Rappuoli R. Sequential activation and environmental regulation of virulence genes in Bordetella pertussis. EMBO J. 1991;10:3971–3975. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04967.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schipper H, Krohne G F, Gross R. Epithelial cell invasion and survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3008–3011. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.3008-3011.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith A M, Walker M J. Transfer of a pertussis toxin expression locus to isogenic bvg-positive and bvg-negative Bordetella bronchiseptica using an in vivo technique. Microb Pathog. 1996;20:263–273. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.tainer D W, Scholte M J. A simple chemically defined medium for the production of phase I Bordetella pertussis. J Gen Microbiol. 1970;63:211–220. doi: 10.1099/00221287-63-2-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steed L L, Setareh M, Friedman R L. Intracellular survival of virulent Bordetella pertussis in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;50:321–330. doi: 10.1002/jlb.50.4.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stock J B, Ninfa A J, Stock A M. Protein phosphorylation and regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:450–490. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.450-490.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sun G, Birkey S M, Hulett F M. Three two-component signal-transduction systems interact for Pho regulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:941–948. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.422952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Switzer W P, Farrington D O. Bordetellosis. In: Leman A D, Glock R D, Mengeling W L, Penny R H C, Scholl E, Straw B, editors. Diseases in swine. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1981. pp. 497–507. [Google Scholar]

- 70.von Hippel P H, Bear D G, Morgan W D, McSwiggen J A. Protein-nucleic acid interactions in transcription: a molecular analysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:389–446. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.002133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walker M J, Guzmán C A, Rohde M, Timmis K N. Production of recombinant Bordetella pertussis serotype 2 fimbriae in Bordetella parapertussis and Bordetella bronchiseptica: utility of Escherichia coli gene expression signals. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1739–1746. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.5.1739-1746.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weiss A A, Falkow S. Genetic analysis of phase change in Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1984;43:263–269. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.1.263-269.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weiss A A, Hewlett E L, Myers G A, Falkow S. Tn5-induced mutations affecting virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1983;42:33–41. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.33-41.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.West N P, Fitter J T, Jakubzik U, Rohde M, Guzman C A, Walker M J. Non-motile mini-transposon mutants of Bordetella bronchiseptica exhibit altered abilities to invade and survive in eukaryotic cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;146:263–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]