Abstract

CD8+ T cells play a crucial role in the control of infection with intracellular microbes. The mechanisms underlying the CD8+ T-cell-mediated clearance of the intracellular pathogen Toxoplasma gondii are, however, not completely understood. The effect of CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL)-mediated lysis of host cells on the viability of intracellular T. gondii was investigated. Quantitative competitive PCR of the gene encoding T. gondii major surface antigen (SAG-1) was combined with treatment of the parasites with DNase, which removed the DNA template of nonviable parasites. The induction by CD8+ CTLs of apoptosis in cells infected with T. gondii did not result in the reduction of live parasites, indicating that intracellular T. gondii remains alive after lysis of host cells by CTLs.

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite that infects all warm-blooded animals, including humans. After the primary infection in an immunocompetent individual, the immune response of the host limits the replication of tachyzoites, resulting in the formation of the bradyzoite form, a dormant stage of the parasite. Because of this effective immune reaction against parasites, chronic infection of an immunocompetent individual with T. gondii is usually asymptomatic (3). However, in patients with AIDS as well as other immunocompromised states, reactivation of chronic toxoplasmosis results in excessive cellular destruction, often leading to severe morbidity and mortality (10).

Protective immune responses against infection with T. gondii have been studied with experimental murine systems. Vaccination with an attenuated mutant (22, 24) or irradiated tachyzoites (18, 25) induces protective responses against subsequent infection with the virulent RH strain. CD8+ T-cell-mediated immunity is one of the major protective mechanisms. Mice primed with T. gondii succumb to lethal infection when depleted of CD8+ T cells prior to challenge infection, and host resistance can be adoptively transferred to naive animals by primed CD8+ T cells (22, 25) or by CD8+ T-cell clones specific for T. gondii major surface antigen (SAG-1) (8). However, the underlying mechanisms of CD8+ cell-mediated protective immunity are not completely understood. The protection depends on the presence of gamma interferon, which can be secreted by CD8+ as well as CD4+ cells (8, 23). T. gondii-specific CD8+ T cells also lyse parasite-infected target cells in a class I major histocompatibility complex-restricted manner (7, 11, 14, 21, 26). Lysis of host cells may directly damage intracellular microbes or simply release viable parasites into the extracellular space. Apoptosis of infected host cells induced either chemically (13) or by CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) (20) appears to be coupled to damage to intracellular mycobacteria. Little is known, however, about the fate of T. gondii parasites in host cells lysed by CD8+ CTL.

The present study was therefore designed to determine whether CD8+ CTL-mediated lysis of host cells is associated with the killing of intracellular T. gondii tachyzoites. We developed a novel method to determine the number of live T. gondii parasites within host cells undergoing apoptosis. We used a combination of DNase treatment of the samples prior to DNA extraction, which removed DNA within dead parasites, and quantitative competitive PCR (QC-PCR) of the T. gondii SAG-1 gene (12). The results indicated that CD8+ CTL-mediated apoptosis of target cells does not lead to the death of intracellular T. gondii tachyzoites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, parasites, and cell lines.

BALB/cAnNCrj and C57BL/6NCrj mice and Lewis/Crj rats were purchased from Charles River Japan (Kanagawa, Japan). Animals were housed in the Laboratory Animal Center for Biomedical Research at the Nagasaki University School of Medicine (Nagasaki, Japan) and were used at 8 to 10 weeks of age. T. gondii RH was maintained as previously described (16, 26). M12-neo-1 cells were generated by stable transfection of M12.4.1 cells (a gift from L. Glimcher, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass.) (9) with linearized Rc/CMV (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) by use of a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Transfectants were selected in culture medium containing G418 (0.5 mg/ml) (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) and cloned by a limiting-dilution method.

H-2d-specific CTL lines were established from nonadherent splenocytes of C57BL/6 mice by repeated stimulation with X-ray-irradiated (20 Gy) BALB/c splenocytes in RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco BRL), 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 50 μM mercaptoethanol, and 20 U of human recombinant interleukin 2 (Shionogi, Osaka, Japan) per ml. These T cells expressed the T-cell-receptor β chain and were of the CD3+ CD4− CD8+ phenotype (data not shown). The cytolytic activity of the T-cell lines was determined by a standard 51Cr release assay as described previously (1). The percentages of specific 51Cr release by M12.4.1 (H-2d), P815 mastocytoma (H-2d), and EL4 thymoma (H-2b) cells at an effector/target cell ratio of 2.5:1 were 74, 69, and 1%, respectively, indicating that these cell lines were specific for H-2d.

To induce CTL specific for T. gondii, BALB/c mice were primed twice by intraperitoneal inoculations with T. gondii RH tachyzoites (107/mouse) which had been inactivated by treatment with mitomycin C (200 μg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C. Two weeks after the final priming, mice were sacrificed and spleens were removed. After lysis of erythrocytes, spleen cells (4 × 106/ml) were cultured for 5 days in the presence of mitomycin C-treated T. gondii tachyzoites (106/ml) to induce CTL specific for T. gondii.

DNase treatment of killed T. gondii and DNA preparation.

Complement-mediated killing of free tachyzoites (105) was performed at 37°C for 30 min with rat anti-T. gondii serum prepared from a Lewis rat after priming with X-ray-irradiated (120 Gy) RH tachyzoites and with rabbit complement. The trypan blue dye exclusion test indicated that 100% of the parasites treated with antibody plus complement were dead after the treatment (data not shown). Cells were incubated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing DNase (50 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. After the cells were washed once with PBS, genomic DNA was prepared with DNAzol (Gibco BRL) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Glycogen (10 μg) (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was included in the DNAzol solution as a carrier.

Preparation of DNA from T. gondii-infected target cells after CD8+ T-cell-mediated cytolysis.

M12-neo-1 cells were infected with tachyzoites at a multiplicity of infection of 3:1 for 2 h at 37°C. Free tachyzoites were removed from infected cells by two rounds of low-speed centrifugation (70 × g for 10 min) followed by use of a magnetic cell separation system (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The infected cells were incubated with rat anti-T. gondii serum at 4°C for 10 min. After being washed with PBS, the cells were incubated with microbeads coated with mouse anti-rat immunoglobulins (20 μl of magnetic probes per 106 cells) in 1 ml of PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.1 mM EDTA at 8°C for 20 min. Free tachyzoites were subsequently removed in a magnet field of 0.6 T with an MS column (Miltenyi Biotec) in which the flowthrough fraction was collected. The number of contaminating free tachyzoites was less than 2% of M12-neo-1 cells, as determined by light microscopy. The proportion of the cells infected with T. gondii was 40 to 50%. After coculturing of infected M12-neo-1 cells (104) with CTL (105), samples were treated with DNase (50 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C and DNA was extracted. In some experiments (see Fig. 3), T. gondii-infected M12-neo-1 cells were passed through a 30-gauge needle several times to force the intracellular parasites out of the parasitophorous vacuoles as described previously (4). The materials were treated or not treated with anti-T. gondii serum and complement before DNase treatment.

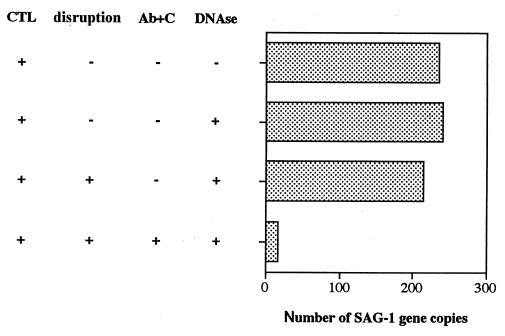

FIG. 3.

Resistance of the intracellular T. gondii to DNase treatment after CTL-mediated lysis of the host cells. M12-neo-1 cells (104) infected with tachyzoites for 15 h (infection rate, 40%) were cultured in the presence of an H-2d-specific CTL line at an effector/target cell ratio of 10:1 for 4 h. The samples were disrupted by repeated passage through a 30-gauge needle. One of the disrupted samples was treated with rat anti-T. gondii serum (Ab) and complement (C). Finally, the samples were treated or not treated with DNase, and DNA was extracted. QC-PCR of each DNA sample was performed, and the SAG-1 gene copy number was estimated as described in Materials and Methods. Mean data from one of two similar independent duplicate experiments are shown.

QC-PCR of SAG-1 and Neo genes.

The number of parasites was determined by QC-PCR of the SAG-1 gene as previously described (12). Briefly, genomic DNA (<1 μg) extracted from T. gondii or infected cells was coamplified with a constant amount of competitor DNA (i.e., approximately 90 copies of the truncated SAG-1 gene) by use of a set of SAG-1-specific primers for 36 cycles in a final volume of 50 μl in a TSR-300 thermal sequencer (IWAKI Glass Co. Ltd., Chiba, Japan). The amplified products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. The ratios of the staining intensities of the amplified target and competitor sequences were determined by densitometry (IPLab Gel densitometer; Signal Analytical Corp., Vienna, Va.). By comparing the ratio thus obtained to a standard curve, the copy number of SAG-1 DNA was calculated. The detection limit was seven copies of SAG-1 DNA per sample. Because SAG-1 is a single-copy gene, the copy number of SAG-1 DNA is equal to the number of T. gondii tachyzoites. The results were expressed as the mean parasite number per template DNA, corresponding to 100 input tachyzoites or 300 infected M12-neo-1 cells ± 1 standard deviation (SD). For statistical comparisons of two groups, an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

The number of live M12-neo-1 cells was determined by QC-PCR of the Neo gene. Heterologous competitor DNA was constructed by PCR with a BamHI/EcoRI fragment of the v-erbB gene as a template by use of a PCR MIMIC construction kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.). This DNA fragment was amplified with a pair of oligonucleotides (5′-GAGAGGCTATTCGGCTATGACTGGATCCCCGCAAGTGAAATCTC-3′ and 5′-ACTCGTCAAGAAGGCGATAGAAGTGATTCTGGACCATGGCAGT-3′) which contained 23-bp Neo gene sequences at the 5′ end of the v-erbB gene sequence, resulting in the generation of a 509-bp sequence within two Neo gene primers. The DNA within the Neo gene sequences was amplified with a pair of primers (5′-GAGAGGCTATTCGGCTATGACTG-3′ and 5′-ACTCGTCAAGAAGGCGATAGAAG-3′) (nucleotides 49 to 71 and 766 to 787, respectively) (19). The target and competitor sequences were 739 and 558 bp, respectively. A constant amount (approximately 2 × 10−3 amol) of competitor DNA was added to the 50-μl PCR mixture (38 cycles) containing template DNA. The amplified products were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and stained, and the ratios of the staining intensities of the target and competitor sequences were determined by densitometry. The results were expressed as the mean number of M12-neo-1 cells per template DNA, corresponding to 300 input target cells ± 1 SD.

RESULTS

Estimation of the number of live T. gondii organisms by QC-PCR.

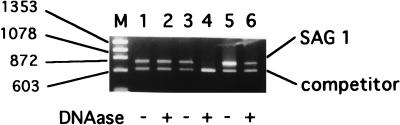

The number of intracellular T. gondii organisms can be quantitated by plotting the ratios of the sequence of the QC-PCR product of T. gondii SAG-1 and its competitor sequences against a standard curve (12). Initially, we examined whether this method can selectively amplify DNA of viable parasites. DNA extracted from free viable tachyzoites and those killed by anti-T. gondii serum plus complement was used to determine the number of T. gondii organisms by QC-PCR (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The ratios of the amplified target and competitor sequences did not differ significantly (Fig. 1, lanes 1 and 3; Table 1; P = 0.207), indicating that the DNA extracted from complement-killed T. gondii can become a template for PCR, like that extracted from viable T. gondii. Therefore, we modified this method by introducing DNase treatment to exclude DNA from dead parasites and determined whether the number of live parasites can be estimated by QC-PCR. Free T. gondii was treated with DNase to remove the DNA template within killed T. gondii, assuming that DNase can gain access to the DNA within dead but not viable cells. This pretreatment reduced the amount of the PCR product from dead parasites more than 100-fold (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 4; Table 1). This reduction was selective for dead parasites, because the same treatment did not significantly reduce the amount of the PCR product from live parasites (Fig. 1, lane 2; Table 1, P = 0.268). To determine that this method can be applied to a mixture of live and dead T. gondii, a sample containing a 1:1 mixture of live and dead parasites was treated with DNase, and the number of viable T. gondii parasites was quantitated by QC-PCR. As expected, the number of SAG-1 gene copies obtained from the DNase-treated samples (88 ± 2) was approximately half that in the untreated samples (163 ± 16) (Fig. 1, lanes 5 and 6; Table 1). In a separate experiment, we confirmed that the gene copy numbers estimated by this method had a linear relationship with the ratios of viable parasites within the mixture of dead and live T. gondii (data not shown). These results indicated that DNase treatment effectively eliminates the SAG-1 gene within dead T. gondii and that this method can be applied to the quantitation of live parasites in the presence of dead T. gondii and host tissue.

FIG. 1.

QC-PCR of DNA from cells treated with DNase. Free T. gondii organisms were untreated (lanes 1 and 2) or treated with anti-T. gondii serum and complement (lanes 3 and 4), or both untreated and treated T. gondii organisms were mixed at 1:1 (lanes 5 and 6). Cells were untreated (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or treated (lanes 2, 4, and 6) with DNase. DNA was extracted and amplified in the presence of competitor DNA with SAG-1 primers. Each lane represents QC-PCR of the DNA template corresponding to 100 tachyzoites. M, molecular size marker (φX174 HaeIII digest); sizes (in bases) are shown at left. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Similar results were obtained in four independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

Number of SAG-1 gene copies in live and dead T. gondii after DNase treatmenta

| DNase treatment | Results obtained with the following treatment of T. gondii prior to DNase treatment:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not treated (P = 0.268)b | Anti-T. gondii antibody + complement (P < 0.001) | Mixture of not treated plus anti-T. gondii antibody + complement (P = 0.01) | |

| − | 135 ± 8 | 149 ± 14 | 163 ± 16 |

| + | 128 ± 5 | <7 | 88 ± 2 |

Tachyzoites were not treated or were treated with anti-T. gondii serum and complement. Their viability was nearly 100% (not treated) or 0% (treated), as determined by the trypan blue dye exclusion test. These tachyzoites or their 1:1 mixture was treated (+) or not treated (−) with DNase. DNA was extracted and subjected to QC-PCR of the SAG-1 gene in triplicate. The results are expressed as the mean SAG-1 copy number per template DNA, corresponding to approximately 100 input tachyzoites ± 1 SD. The detection limit was seven copies.

Data are for Student’s t test between DNase-treated and untreated groups.

Viability of T. gondii in infected CTL target cells.

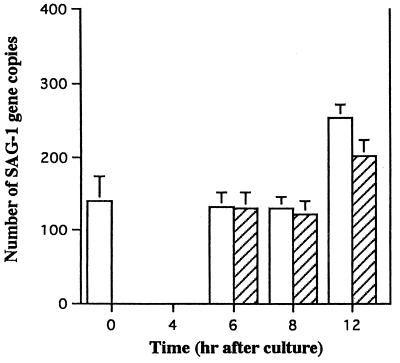

We applied this method to determine the fate of intracellular tachyzoites after the lysis of host cells by CD8+ CTL. An alloreactive CTL line specific for H-2d was generated by repeated stimulation of C57BL/6 lymphocytes with BALB/c spleen cells. The stable cell line M12-neo-1 was used as a target. The use of a neo transfectant cell line allowed quantitation of the number of viable target cells in the presence of CTL. M12-neo-1 cells were infected with T. gondii in vitro. After the removal of free T. gondii, the infected target cells were incubated with H-2d-specific CTL for 0 to 12 h. Cells were treated with DNase, and DNA was extracted and subjected to QC-PCR to determine the number of live T. gondii parasites within the target cells (Fig. 2). During the initial 8 h of coculturing, the number of tachyzoites within the target cells did not change significantly. After 8 h, the number increased, perhaps due to the DNA synthesis of T. gondii within the infected cells. Interestingly, this increase was observed even when the target cells were lysed by CTL. We speculate that some of the parasites within the apoptotic target cells infected and multiplied within effector CTL. Indeed, light microscopic inspection of the cells after 12 h of culturing revealed that approximately 8% of the effector T cells were infected by tachyzoites (data not shown). In the same experiment, 51Cr release by the target cells reached 84% during 6 h of culturing (Fig. 2). These results indicate that CTL-mediated lysis of cells infected with tachyzoites does not lead to the death of the intracellular parasites.

FIG. 2.

Kinetics of the number of viable tachyzoites after host cells were lysed by CTL. Ten thousand M12-neo-1 cells were infected with RH tachyzoites (infection rate, 45%) and cultured in the presence (hatched bars) or absence (open bars) of CTL at an effector/target cell ratio of 10:1. The reaction was terminated at the times indicated, and the number of viable tachyzoites was determined by QC-PCR. Results are shown as the mean parasite number per 300 M12-neo-1 cells initially placed in the culture ± 1 SD (four samples/group). In the same experiment, a portion of the infected M12-neo-1 cells was 51Cr labeled, and CTL activity was assessed by the 51Cr release assay. The percentages of specific 51Cr release by the target cells during 4 and 6 h of culturing were 76 and 84%, respectively. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments.

One caveat of this interpretation is that there remained a possibility that DNase might not be able to access DNA within cells lysed by CTL and therefore might be unable to digest DNA of intracellular T. gondii. To rule out this possibility, we determined whether DNase is able to reach the DNA within lysed target cells (Table 2). The M12-neo-1 cell line was used as a target for this purpose. Thus, the Neo gene is present in target and not in effector cells, enabling us to determine the number of viable target cells in the target cell-effector cell mixture. M12-neo-1 cells were incubated with alloreactive CTL, and QC-PCR of the Neo gene was performed with DNA extracted from these cells. Coculturing of M12-neo-1 cells with CTL resulted in the reduction of the Neo gene copy number in parallel with an increase in 51Cr release by the target cells. In contrast, M12-neo-1 cells cultured without CTL maintained the same copy number of the Neo gene after DNase treatment. The comparison of QC-PCR with 51Cr release suggested that permeability to DNase may be a more sensitive method than 51Cr release in determining CTL activity. Thus, DNase is able to access cellular DNA when target cells are lysed by CTL.

TABLE 2.

Number of Neo gene copies of M12-neo-1 cells after lysis by CTL and DNase treatmenta

| Time (h) | Neo gene copy no. with the following CTL/DNase treatment:

|

% Specific 51Cr release | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −/− | −/+ | +/− | +/+ | ||

| 0 | 195 ± 30 | 180 ± 17 | ND | ND | ND |

| 1 | ND | ND | 199 ± 24 | 64 ± 3 | 48 |

| 2 | ND | ND | 210 ± 36 | 26 ± 12 | 67 |

| 4 | ND | ND | 188 ± 35 | 4 ± 2 | 78 |

51Cr-labeled M12-neo-1 cells (104) were incubated or not incubated with alloreactive CTL cells (105) for 1 to 4 h, and treated or not treated with DNase. The number of Neo gene copies was determined by QC-PCR and is expressed as the mean copy number per template DNA, corresponding to 300 input M12-neo-1 cells ± 1 SD. The percent specific 51Cr release was determined by a standard method in the same experiment. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. ND, not done.

Intracellular T. gondii resides within parasitophorous vacuoles. It was thus still not clear whether DNase could reach the DNA of intracellular T. gondii after CTL-mediated lysis of host cells. Thus, we examined the viability of intracellular T. gondii after CTL-mediated lysis of host cells by an alternative method. We examined whether intracellular T. gondii within host cells lysed by CTL maintains an intact cell membrane. After coculturing with CTL, parasites were released from target cells by mechanical disruption. DNA was extracted from these samples after DNase treatment and subjected to QC-PCR (Fig. 3). To confirm that dead parasites were DNase accessible in this experiment, one of the disrupted samples was treated with anti-T. gondii antibody and complement prior to DNase treatment. The results indicated that T. gondii within CTL target cells was resistant to DNase treatment, supporting the conclusion that the parasites were alive.

Finally, to determine that intracellular T. gondii was indeed viable after the lysis of host cells by T. gondii-specific CTL, we determined the numbers of Neo and SAG-1 gene copies in T. gondii-infected M12-neo-1 cells after incubation with T. gondii-specific CTL and DNase treatment (Table 3). CTL were induced by coculturing of primed BALB/c spleen cells with mitomycin C-treated T. gondii tachyzoites. These CTL were specific for T. gondii because treatment of the T. gondii-infected target cells with DNase after coculturing with the CTL resulted in a 64% reduction in the Neo gene copy number (137 versus 60), while no significant reduction was observed when the target cells were not infected (124 versus 122). The same DNA samples were used to assess the viability of T. gondii within the target cells. The SAG-1 gene copy number did not change significantly after DNase treatment (102 versus 110), indicating that intracellular T. gondii was alive after lysis of the target cells by the T. gondii-specific CTL.

TABLE 3.

Effect of T. gondii-specific CTL on the viability of intracellular T. gondiia

| CTL | Infection of target cells with T. gondii | No. of copies of the following gene with the indicated DNase treatment:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neo

|

SAG-1

|

||||

| − | + | − | + | ||

| − | − | 136 ± 40 | 118 ± 30 | ND | ND |

| − | + | 148 ± 32 | 144 ± 20 | 110 ± 14 | 140 ± 52 |

| + | − | 124 ± 7 | 122 ± 25 | ND | ND |

| + | + | 137 ± 27 | 60 ± 19 | 102 ± 8 | 110 ± 9 |

M12-neo-1 cells (104) which were infected (+) or not infected (−) with T. gondii were incubated or not incubated with CTL specific for T. gondii for 4 h at an effector/target cell ratio of 50:1 prior to DNase treatment. The numbers of Neo and SAG-1 gene copies were determined by QC-PCR as described in Materials and Methods and are expressed as the mean copy number for triplicate experiments ± 1 SD. Fifty-one percent of the target cells were infected with T. gondii, as determined by light microscopy. ND, not done.

DISCUSSION

A novel method to selectively quantitate the number of live T. gondii parasites in a mixture of dead T. gondii and host tissue was developed. The quantitation of live T. gondii parasites was previously performed by determining their ability to grow intracellularly or lyse host cells by a 3H-uracil incorporation assay or a plaque assay, respectively (15). However, only 20 to 30% of the free tachyzoites lysed from hosts are infective for other cells, and these methods are difficult to apply in quantifying viable tachyzoites within apoptotic host cells, because individual tachyzoites cannot be segregated from the apoptotic cell, which tends to clump. Therefore, we used membrane permeability as a measure of cell viability and overcame these difficulties by a combination of DNase treatment and QC-PCR, which allowed simple and rapid quantitation of viable tachyzoites in the cell mixture. This method was applied to determine whether CD8+ CTL can kill intracellular tachyzoites when they lyse target cells. The results indicated that CTL specific for T. gondii are unable to kill intracellular T. gondii tachyzoites.

The induction of apoptosis in target cells by CD8+ CTL is mediated by perforin and granzyme B or the engagement of Fas on the target cells (7, 11). In our assay system, it is likely that the lysis of T. gondii-infected target cells was mediated by perforin and granzyme B, because the CTL used in our assay system are conventional CD8+ CTL and because M12-neo-1 target cells do not express Fas (reference 5 and unpublished data). Thus, we believe that the lysis of T. gondii-infected cells through the release of cytotoxic granules by CTL does not lead to the death of intracellular parasites. Indeed, perforin does not appear obligatory for protection against T. gondii infection, because T. gondii-primed perforin knockout mice retain resistance to challenge infection with the parasite (2). It is formally possible that Fas-mediated lysis of host cells has distinct effects on intracellular T. gondii. We think it is unlikely, however, because the induction of apoptosis in Fas+ A20 cells infected with T. gondii by anti-Fas monoclonal antibodies did not kill intracellular parasites (data not shown). Perforin- or granzyme-mediated lysis of infected macrophages by CTL has been shown to result in the death of intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis, whereas Fas-mediated lysis has not (20). The discrepancy between our study and theirs may be due to the differences in the pathogens used (T. gondii versus M. tuberculosis) and in the host species (mouse versus human). Alternatively, differences in host cells may explain this difference. We used a B-cell tumor which does not have the phagocytic ability of apoptotic cells, while they used macrophages as infected targets. Therefore, the possibility that the death of the intracellular bacteria was due to the phagocytosis of apoptotic macrophages by neighboring macrophages was not completely ruled out in their study. It is also possible that a subset of CD8+ CTL can kill intracellular T. gondii.

We previously demonstrated that protective immunity against a virulent strain of T. gondii can be transferred to naive animals by adoptive transfer of primed CD8+ cells (25). If CD8+ CTL are not themselves cytotoxic for intracellular T. gondii, how are tachyzoites cleared in vivo? The lysis of host cells by CTL may release tachyzoites from their sequestered environment into the extracellular space, where other effector molecules and cells are accessible. These include antibody, complement, NK cells, a population of CD8+ T cells which are directly parasitocidal (8), and macrophages (6). It is unclear which molecules and cells are the most critical for clearing tachyzoites after host cell lysis. Alternatively, tachyzoites may be cleared even prior to their release into the extracellular fluid after the induction of host cell apoptosis. Induction of apoptosis by CD8+ T lymphocytes may result in the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages (17), resulting in enzymatic digestion of the parasites in phagolysosomes. Thus, one of the roles of CTL may be to prepare infected cells for engulfment by macrophages. In our CTL assay, only target cells and CTL were mixed in vitro, and intracellular T. gondii survived the CTL-mediated lysis of the host cells. We believe that it is likely that macrophages are involved in the clearance of T. gondii in vivo. Our preliminary study indeed suggests that this mechanism may be operative.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Y. Imamura for help and Y. Hagisaka for technical assistance. We also thank G. Massey for editorial assistance and I. A. Khan for advice.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aosai F, Yang T H, Ueda M, Yano A. Isolation of naturally processed peptides from a Toxoplasma gondii-infected human B lymphoma cell line that are recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Parasitol. 1994;80:260–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denkers E Y, Yap G, Scharton-Kersten T, Charest H, Butcher B A, Caspar P, Heiny S, Sher A. Perforin-mediated cytolysis plays a limited role in host resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1997;159:1903–1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frenkel J K. Pathophysiology of toxoplasmosis. Parasitol Today. 1988;4:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(88)90018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gazzinelli R T, Hakim F T, Hieny S, Shearer G M, Sher A. Synergistic role of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in INF-gamma production and protective immunity induced by an attenuated Toxoplasma gondii vaccine. J Immunol. 1991;146:286–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahn S, Gehri R, Erb P. Mechanism and biological significance of CD4-mediated cytotoxicity. Immunol Rev. 1995;146:57–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1995.tb00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joiner K A, Fuhrman S A, Miettinen H M, Kasper L H, Mellman I. Toxoplasma gondii: fusion competence of parasitophorous vacuoles in Fc receptor-transfected fibroblasts. Science. 1990;249:641–646. doi: 10.1126/science.2200126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kagi D, Vignaux F, Ledermann B, Burki K, Depraetere V, Nagata S, Hengartner H, Golstein P. Fas and perforin pathways as major mechanisms of T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Science. 1994;265:528–530. doi: 10.1126/science.7518614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan I A, Smith K A, Kasper L H. Induction of antigen-specific parasiticidal cytotoxic T cell splenocytes by a major membrane protein (P30) of Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1988;141:3600–3605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim K J, Kanellopoulos-Langevin C, Merwin R, Sachs D, Asofsky R. Establishment and characterization of BALB/c lymphoma lines with B cell properties. J Immunol. 1979;122:549–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy R M, Bredesen D E, Rosenblum M L. Neurological manifestations of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): experience at UCSF and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1995;62:475–495. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.4.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowin B, Hahne M, Mattmann C, Tschopp J. Cytolytic T-cell cytotoxicity is mediated through perforin and Fas lytic pathways. Nature. 1994;370:650–652. doi: 10.1038/370650a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo W-T, Seki T, Yamashita K, Aosai F, Ueda M, Yano A. Quantitative detection of Toxoplasma gondii by competitive polymerase chain reaction of the surface specific antigen gene-1. Jpn J Parasitol. 1995;44:183–190. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molloy A, Laochumroonvorapong P, Kaplan G. Apoptosis, but not necrosis, of infected monocytes is coupled with killing of intracellular bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1499–1509. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montoya J G, Lowe K E, Clayberger C, Moody D, Do D, Remington J S, Talib S, Subauste C S. Human CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes are both cytotoxic to Toxoplasma gondii-infected cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:176–181. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.176-181.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roos D S, Donald R G, Morrissette N S, Moulton A L. Molecular tools for genetic dissection of the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;45:27–63. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61845-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabin A B. Toxoplasmic encephalitis in children. JAMA. 1941;116:801–807. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savill J. Phagocyte recognition of apoptotic cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24:1065–1069. doi: 10.1042/bst0241065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seah S K, Hucal G. The use of irradiated vaccine in immunization against experimental murine toxoplasmosis. Can J Microbiol. 1975;21:1379–1385. doi: 10.1139/m75-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Southern P J, Berg P. Transformation of mammalian cells to antibiotic resistance with a bacterial gene under control of the SV40 early region promoter. J Mol Appl Genet. 1982;1:327–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stenger S, Mazzaccaro R J, Uyemura K, Cho S, Barnes P F, Rosat J P, Sette A, Brenner M B, Porcelli S A, Bloom B, Modlin R L. Differential effects of cytolytic T cell subsets on intracellular infection. Science. 1997;276:1684–1687. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subauste C S, Koniaris A H, Remington J S. Murine CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes lyse Toxoplasma gondii-infected cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:3955–3959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki Y, Remington J S. Dual regulation of resistance against Toxoplasma gondii infection by Lyt-2+ and Lyt-1+, L3T4+ T cells in mice. J Immunol. 1988;140:3943–3946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki Y, Remington J S. The effect of anti-IFN-gamma antibody on the protective effect of Lyt-2+ immune T cells against toxoplasmosis in mice. J Immunol. 1990;144:1954–1956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waldeland H, Frenkel J K. Live and killed vaccines against toxoplasmosis in mice. J Parasitol. 1983;69:60–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamashita K, Ueda M, Yano A. CD8+ T-cell mediated protection against acute toxoplasmosis in mice induced with X-ray irradiated Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites. Jpn J Parasitol. 1996;45:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yano A, Aosai F, Ohta M, Hasekura H, Sugane K, Hayashi S. Antigen presentation by Toxoplasma gondii-infected cells to CD4+ proliferative T cells and CD8+ cytotoxic cells. J Parasitol. 1989;75:411–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]