Abstract

A series of related genes that are flanked at their 5′ ends by a conserved upstream sequence element called the upstream homology box (UHB) have been identified in Borrelia burgdorferi. These genes have been referred to as the UHB or erp gene family. We previously demonstrated that among a limited number of B. burgdorferi isolates, the UHB gene family is variable in composition and organization. Prior to this report the UHB gene family in other species of the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex had not been studied, and if this family is important in the pathogenesis or biology of the Lyme disease spirochetes, then a wide distribution among species and isolates of the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex would be expected. To assess this, we screened for the UHB element by Southern hybridization and determined its restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns. The UHB element was found to be carried by all B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex species tested (B. burgdorferi, B. garinii, B. afzelii, B. japonica, B. valaisiana sp. nov., and B. andersonii), but the RFLP patterns varied widely at both the inter- and intraspecies levels. Variation in both the number and size of the hybridizing restriction fragments was evident. PCR analyses also revealed the presence of polymorphic, ospE-related alleles in many isolates. Sequence analyses identified the molecular basis of the polymorphisms as being primarily insertions and deletions. Sequence variation and the insertions and deletions were found to be clustered in two distinct domains (variable domains 1 and 2). In many isolates variable domain 1 is flanked by direct repeat elements, some as long as 38 bp. Computer analyses of the deduced amino acid sequences encoded within variable domain 1 predict them to be hydrophilic, surface exposed, and antigenic. The analyses conducted here suggest that the UHB gene family, as evidenced by the variable UHB RFLP patterns, is not evolutionarily stable and that the polymorphic ospE alleles are derived from a common ancestral gene which has been modified through mutation or recombination events. The characterization of ospE-related genes of the UHB gene family among B. burgdorferi sensu lato species will prove important in attempts to construct a model for UHB gene family organization and in deciphering the role of the UHB gene family in the biology and pathogenesis of the Lyme disease spirochetes.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that the Borrelia burgdorferi genome carries repeated sequences, numerous gene families, and multiple copies of closely related plasmids (4–6, 9, 11, 20, 22, 24, 25, 29). B. burgdorferi B31T may carry as many as seven related 32-kb circular plasmids (cp32s) (20) that carry some members of the upstream homology box (UHB) gene family (also referred to as the erp gene family) (6, 20, 25). The UHB gene family is defined by the presence of a conserved upstream sequence called the UHB element (1, 14, 20, 25–27). Nucleotide sequence identity values for the UHB elements from different isolates and from different UHB gene family members range from 81 to 100% (20). The conservation of this putative control element may suggest that the gene family is responsive to common regulatory factors or environmental regulatory signals and could constitute a regulon.

ospE and ospF, the first UHB gene family members to be identified, were found to exist as an operon in B. burgdorferi N40 (14). However, in other B. burgdorferi isolates these genes are not linked (1, 20). Some of the ospE-related genes that have been described exist in operons with downstream genes distinct from ospF (25), and some isolates carry paralogs of ospF that exist independently of ospE (1, 20). The emerging picture is that the UHB gene family is highly variable and more complex than previously recognized. UHB gene family members that have been identified to date include ospEF (14), ospEi and ospFi (20), pG (27), bbk2.10 (1), the erp genes (6, 25), and p21 (26). These genes were identified in a variety of isolates; hence, it remains to be determined if all or just a subset of these genes are carried by individual isolates. Among the genes that are flanked at their 5′ ends by UHB elements, there is a subgroup which exhibits high homology to ospE. This UHB gene family subgroup includes ospEi, erpA, erpI, erpC, and p21. The nucleotide identity values of these genes with ospE range from 85 to 100% (a summary of sequence identities and other properties of these genes is presented in Table 1). We refer to these genes collectively as ospE-related genes or ospE paralogs.

TABLE 1.

Sequence accession numbers and features of UHB gene family members

| Accession number and gene name (reference) | Isolate of origina | Gene feature(s)b |

|---|---|---|

| L13924ospE (14) | N40 | First gene of the ospEF operon in B. burgdorferi isolate N40 |

| L13925ospF (14) | N40 | Second gene of the ospEF operon in isolate N40 |

| L78248ospEi (20) | B31 | 91% nt identity with N40 ospE but not 3′ flanked by ospF |

| L78250ospEi (20) | N40CH | 87% nt identity with N40 ospE, not 3′ flanked by a conserved ospF |

| U44912erpA (25) | B31T | Flanked 3′ by erpB in some isolates, 85% nt identity to ospE |

| U78764erpA2 | B31T | Identical in sequence to erpA but carried on a different cp32 in isolate B31 |

| U44912erpB (25) | B31T | Resides 3′ of erpA in some isolates, 36% nt identity to ospF |

| U44914erpC (25) | B31T | Flanked 3′ by erpD in some isolates, 88% nt identity to ospE |

| U44914erpD (25) | B31T | Resides 3′ of erpC in some isolates, 38% nt identity to ospF |

| U72996erpI (6) | B31T | Flanked 3′ by erpJ, 100% nt identity to erpA |

| U72997erpK (6) | B31T | Peripheral member of the UHB gene family exhibiting 54 and 68% nt identity with ospE and ospF, respectively |

| U72996erpJ (6) | B31T | Resides 3′ of erpI in isolate B31T, 100% nt identity to erpB |

| L78249ospEi (20) | 297CH | 86% nt identity with N40 ospE, not 3′ flanked by a conserved ospF |

| X82409pG (27) | ZS7 | Immediately upstream from the bapA (bapA is homologous to eppA [7]) |

| X82409bapA (27) | ZS7 | Downstream from pG, 80% amino acid similarity with eppA, not 5′ flanked by a UHB element |

| L32797p21 (26) | N40 | 86 and 84% nt identity to N40 ospE and B31 ospEi, respectively |

| U18292bbk2.10 (1) | 297 | 77% nt identity to ZS7 pG, 3′ flanked by bapA |

| U19754ospF (1) | 297 | 92 and 98% nt identity to N40 ospF and N40CH ospFi, respectively |

| L78245ospFi (20) | 297CH | 100% identity with N40CH ospFi, 5′ flanked by a UHB element, not preceded by ospE |

| L78251ospFi (20) | N40CH | 91% nt identity with N40 ospF, 5′ flanked by a UHB element, not preceded by ospE |

| L79960ospEF (20) | CA12 | Full-length ospEF operon, ospE and ospF exhibit 79 and 84% nt identity to N40 ospE and ospF, respectively |

| U30617bbk2.11 (1) | 297 | ospF variant |

All isolates are B. burgdorferi.

All genes or operons, unless otherwise indicated, are flanked at their 5′ ends by a highly conserved UHB element.

In this study we have characterized the restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns, distribution, and copy number of the UHB element and have assessed the genetic variability of ospE-related genes among isolates through PCR and DNA sequence analyses. Although UHB elements were detected in all B. burgdorferi sensu lato species tested, the composition of the gene family appears to vary among isolates. PCR, sequence, and Southern analyses of ospE paralogs have revealed that polymorphisms in these genes are localized in distinct domains which computer analyses predict to encode hydrophilic, surface-exposed, and antigenic amino acid sequences. Genetic rearrangement and recombination appear to have contributed to the variable organization of these evolutionarily unstable genes. It is our hypothesis that recombination in and among ospE-related genes could result in a continually evolving, antigenically variable group of surface-exposed proteins. It is conceivable that these proteins could influence the host-pathogen interaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial cultivation and DNA isolation.

Bacterial isolates (Table 2) were cultivated in BSK-H medium (Sigma) supplemented with 6% (vol/vol) rabbit serum (Sigma) at 32°C, harvested by centrifugation, and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.0). Two different B. burgdorferi B31 cultures were analyzed. B. burgdorferi B31T (a cloned isolate) was provided by Sherwood Casjens (University of Utah), and a second population, designated B31, was provided by Tom Schwan (Rocky Mountain Laboratories, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health). DNA was isolated from all isolates listed in Table 2 as previously described (18, 21).

TABLE 2.

Description of isolates utilized in this study and summary of PCR analyses

| Species and isolate(s) | Origina | In vitro passageb | PCR results with uhb(+)-E470(−) primer setc |

|---|---|---|---|

| B. burgdorferi | |||

| 297, 297CH | Human CSF, CT | U (I), 7 (I) | + (mp), + |

| N40,d N40CH, B31, B31Td | Ixodes scapularis, NY | L (I), 7 (I), L (I), L (I) | +, +, +, + |

| R100, T2, 25015 | I. scapularis, NY | 4 (I), 8, 6 (I) | + (p), + (mp), + |

| CA2, CA3, CA12 | Ixodes pacificus, CA | 11, 11, 25 | +, +, + |

| CA4, CA7, CA8, CA9 | I. pacificus, CA | 5, 7, 8, 3 | +, +, +, + |

| CA13 | Ixodes neotomae, CA | 9 | + |

| LP3, LP4, LP5, LP7 | Human, CT | 3, 3, 3, 3 | +, +, +, + |

| 272 | Human EM, USA | 28 | + (mp) |

| NY186 | Human EM, NY | 20 | + |

| HBNCd | Human blood, CA | 2 | + |

| JD1d | I. scapularis, MA | 4 (I) | + (p) |

| VS134, VS307 | Ixodes ricinus, Switzerland | 8, 7 | +/−, + |

| B. garinii | |||

| IP90, IP89 | Ixodes persulcatus, Russia | H, 4 | + (p), + |

| VS102, VSBP | I. ricinus, Switzerland | 9, 8 | +, − |

| G2 | Human CSF, Germany | H | − |

| 153 | I. ricinus, France | 11 | +/− |

| FRG, Pbi, N34 | I. ricinus, Germany | 11, U, H | −, −, +/− |

| G25 | I. ricinus, Sweden | H | +/− |

| B5-92, B4-91 | Human EM, Norway | L, L | +, + |

| B4-87, B6-91 | I. ricinus, Norway | L, L | +/−, + |

| B. valaisiana sp. nov. VS116 | I. ricinus, Switzerland | 9 | + |

| B. afzelii | |||

| J1 | I. persulcatus, Japan | U | + |

| Pbo | Human CSF, Germany | 3 | + |

| IP21, IP3 | I. persulcatus, Russia | H, H | + (p), + |

| Bo23, PGaud | Human EM, Germany | U, L | +, + (mp) |

| Pkod | Human EM, Switzerland | U | + |

| UMO1, ECM1, VS461 | Human skin, Sweden | U, U, 9 | + (p), +, +/− |

| B. andersonii | |||

| 21038d | Ixodes dentatus, NY | L | + (p) |

| 19857 | Rabbit kidney, NY | 22 | +/− |

| B. japonica IKA2, HO14 | Ixodes ovatus, Japan | U, U | + (mp), − |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EM, erythema migrans; CT, Connecticut; NY, New York; CA, California; USA, United States; MA, Massachusetts.

U, unknown passage history; L, passaged in vitro fewer than 15 times; H, passaged more than 30 times; I, confirmed to be infectious.

m, multiple bands were obtained; p, amplicons of a size different (polymorphic) from that predicted were obtained; +, strong amplification; +/−, weak amplification; −, no amplification.

The isolate was cloned by plating.

RFLP pattern determination and Southern blot hybridizations.

HaeIII-digested DNA was fractionated in 0.8% (wt/vol) GTG-agarose gels (United States Biochemical), vacuum blotted onto Hybond N membranes (Amersham), UV cross-linked by using a GS-Genelinker (Bio-Rad), and hybridized with the 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotides described in Table 3. Oligonucleotides were labeled at their 5′ OH groups by using polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci mmol−1; NEN-DuPont). Hybridizations with oligonucleotide probes were conducted at temperatures of 32 to 42°C in a Hybaid hybridization oven (Labnet). The hybridization buffer consisted of 0.2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin, 0.2% (wt/vol) polyvinyl-pyrrolidone (molecular weight, 40,000), 0.2% (wt/vol) Ficoll (molecular weight, 400,000), 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium pyrophosphate, 1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10% (wt/vol) dextran sulfate, 100 μg of herring sperm DNA ml−1, and 1 M NaCl. Two 10-min washes with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% SDS and a 1-h wash with 0.2× SSC–0.1% SDS were performed at temperatures ranging from 32 to 42°C, depending on the probe. A final 5-min wash was done at room temperature with 0.2× SSC–0.1% SDS with vigorous shaking.

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotide probe and primer sequences and target sitesa

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Intended target site positions |

|---|---|---|

| uhb(+) | GTTGGTTAAAATTACATTTGCG | −128 to −107 of the ospEF UHB elementb (B. burgdorferi N40) |

| uhb3(+) | TCCTCTCCTTGAAGGTGTTAC | −426 to −406 of the erpAB UHB element (B. burgdorferi B31) |

| E13(+) | ATGTTTATTATTTGTGCTGTTT | 13 to 40 of ospE (B. burgdorferi N40) |

| E46(+) | CTTATAGGTGCTTGCAAG | 46 to 63 of ospE (B. burgdorferi N40) |

| E46(−) | CTTGCAAGCACCTATAAG | 46 to 63 of ospE (B. burgdorferi N40) |

| E70(−) | ACTTCATATGATGAGCAAAGT | 70 to 90 of ospE (B. burgdorferi N40) |

| E310(−) | AAACTAGTTTTAAATGATCC | 310 to 327 of ospE (B. burgdorferi N40) |

| E470(−) | CTAGTGATATTGCATATTCAG | 470 to 490 of ospE (B. burgdorferi N40) |

| C241(−) | TGCGAATGTATCAGAGTCTCC | 241 to 261 of erpC (B. burgdorferi B31) |

| p21-105 (−) | CGCCATTGCTTTGCTTAACT | 105 to 124 of p21 |

| A468(−) | GTCTCCCCCCGCACTGTTA | 450 to 468 of erpA (B. burgdorferi B31) |

Primer designations are based on the numbering presented in the original descriptions of each individual gene (not on the alignments presented in this report). The data presented in this report demonstrate that several of the probes can hybridize with more than one ospE variant; hence, the probe designations themselves do not imply that the probes are absolutely variant specific. The designations (+) and (−) indicate that the primers are positive- or negative-strand primers, respectively. The sequences of the (−) primers are the inverse complement of the coding sequence.

A conserved binding site for this primer also resides upstream of other UHB gene family members at an analogous position.

PCR.

PCR amplification was performed with Taq polymerase (Promega) in 30-μl reaction volumes as previously described (19). Briefly, cycling conditions were 95°C for 3 min followed by 30 to 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min. Reaction mixtures were overlaid with light mineral oil (Rite-Aid Pharmacy). Primer and oligonucleotide probe sequences and their intended target sites are listed in Table 3. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1.2% GTG-agarose gels in TAE buffer (Tris-acetate [pH 8.5], 2 mM EDTA).

Cloning and DNA sequence analyses.

Selected PCR amplicons were cloned by using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) or the pGEM-T cloning vector (Promega) essentially as described by the manufacturers. PCR products or recombinant clones were purified by using Wizard columns (Promega) and directly sequenced by using end-labeled primers and the fmol DNA sequencing kit (Promega). Sequencing reactions were analyzed in 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gels at 85 W. The gels were transferred directly onto Whatman 3MM paper, wrapped in cellophane, and exposed to film for 1 to 3 h with intensifying screens. Sequences were analyzed by using the Wisconsin Sequence Analysis Package, version 9.0 (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.). To determine pairwise identity and similarity values, the GAP program was run with default parameters. Multiple sequence alignments were generated by using PILEUP and then manually refined. To conduct evolutionary analyses and construct phylograms, the multisequence alignments were used as the input files for the DISTANCES program, which generates a matrix of evolutionary distances. Uncorrected distances were determined. These distances were then used as input for the GROWTREE program to generate phylograms. The neighbor-joining method was used, and negative branch lengths were not allowed.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The PCR amplicons obtained with the uhb(+)-E470(−) primer set from various isolates were assigned accession numbers AF029901 through AF029912. The sequence of the amplicon from B. burgdorferi JD1 was submitted at a later date and was assigned the accession number AF059178.

RESULTS

RFLP pattern analysis of the UHB element.

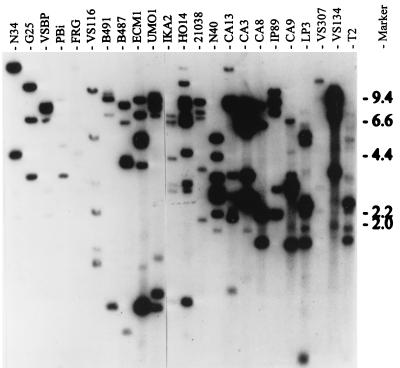

A previous analysis of six B. burgdorferi isolates demonstrated that UHB RFLP patterns are variable and suggested that the complement of UHB gene family members varies among B. burgdorferi isolates (20). To date, the presence and composition of the UHB gene family in other species of the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex have not been assessed. To address this and to further analyze genetic diversity within B. burgdorferi, we screened for the UHB element in other B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates by Southern hybridization and determined the UHB RFLP patterns by using HaeIII-digested DNA. To verify that the DNA had been completely digested, we performed Southern hybridization with a probe targeting the single-copy 16S rRNA gene (rrs) (23). All isolates yielded a single hybridizing band, indicating complete digestion (data not shown). To screen for the UHB element, two different probes were used; the uhb(+) oligonucleotide and a UHB element-targeting, PCR-generated probe (472 bp). Oligonucleotide probe binding sites are presented in Table 3. The PCR probe was generated from B. burgdorferi B31 by using the uhb3(+) and E46(−) primers. Both the uhb(+) oligonucleotide (Fig. 1) and the PCR-generated probe (data not shown) hybridized with DNAs from all B. burgdorferi sensu lato species (B. burgdorferi, B. garinii, B. afzelii, B. andersonii, B. japonica, and B. valaisiana). As with the oligonucleotide probe, no two isolates exhibited the same RFLP pattern when the PCR-generated probe was used. However, for each individual isolate these two probes yielded nearly identical RFLP patterns. When differences were observed, they were mainly in the form of differences in hybridization intensity of the probes with some bands. The two different UHB-targeting probes were used in these analyses because while oligonucleotide probes are best suited for copy number determination, it is possible that some UHB copies could go undetected as a result of sequence divergence within the oligonucleotide target site. Since the PCR probe carries an entire copy of the UHB element (i.e., that region extending from the 5′ end of ospE upstream to the start codon of the oppositely oriented ORF6 [6]), minor sequence divergence would not prevent its hybridization. For B. garinii isolates, identical hybridization profiles were obtained with both probes. This demonstrates that the low UHB copy number in this species, inferred from hybridization with the uhb(+) oligonucleotide, is accurate. Hence, it can be concluded that the copy number of the UHB element varies among isolates. The number of UHB elements detected in B. garinii isolates was lowest, ranging from one to three. In contrast, B. burgdorferi and B. afzelii isolates carry four or more UHB elements. Since the RFLP patterns differ in both the number and size of hybridizing restriction fragments, it can be concluded that the pattern differences are not due solely to loss of some plasmids, since this would only decrease the number of hybridizing bands. Since no discernible conservation of UHB RFLP patterns was observed among isolates of the same species, it can be concluded that the organization of these genes is not reflective of phylogenetic relationships. Hence, UHB gene family composition and organization appear to have been influenced by recent molecular events such as mutation and/or recombination and plasmid loss or acquisition.

FIG. 1.

RFLP patterns of the UHB element among B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex isolates. HaeIII-digested DNA was transferred onto a Hybond N membrane and hybridized with the uhb(+) oligonucleotide under conditions described in the text. The isolates analyzed are indicated above the lanes, and molecular size standards (in kilobases) are indicated on the right. Isolates N34, G25, VSBP, Pbi, FRG, B4-91, and B487 are B. garinii; VS116 is B. valaisiana; ECM1 and UMO1 are B. afzelii; IKA2 and HO14 are B. japonica; 21038 is B. andersonii; and N40, CA13, CA3, CA8, IP89, CA9, LP3, VS307, VS134, and T2 are B. burgdorferi.

PCR analyses of ospE-related genes.

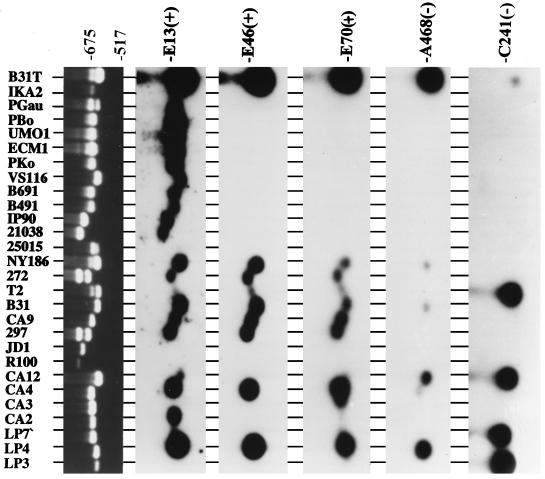

As one step towards assessing possible genetic heterogeneity in ospE-related genes, PCR analyses were performed on 56 B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates with the uhb(+)-E470(−) primer set (Table 2). PCR screening can reveal polymorphisms (insertions or deletions) that might not be evident by Southern blotting. The primers, E470(−) and uhb(+), have conserved binding sites in ospE, erpA, and erpI. Hence, if all three of these genes are present in the genome, each could be amplified by the primer set. It should be noted that a search of the database indicates that two separate but identical copies of erpA (designated erpA and erpA2; for accession numbers, see Table 1) are apparently carried by B. burgdorferi B31T. Since these alleles and erpI are identical in sequence, we did not attempt to differentiate between them. uhb(+)-E470(−) amplicons were obtained from 91% of the isolates tested (51 of 56), with some isolates yielding multiple bands (Table 2; representative data are also presented in Fig. 2). Many of the amplicons were polymorphic, being of a size not consistent with that predicted for ospE, erpA, erpI, or any other known ospE paralog, suggesting that there may be other polymorphic ospE-related genes carried by some B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates. Hybridization and DNA sequence analyses designed to identify the molecular basis of these possible gene polymorphisms are described in detail below.

FIG. 2.

PCR analyses of ospE and hybridization analyses of the amplicons with oligonucleotide probes targeting various ospE paralogs. PCR with the uhb(+)-E470(−) primer set was performed on various isolates. Ten microliters of each reaction mixture was analyzed in a 1.2% agarose gel and then stained with ethidium bromide. (Top panel) Representative PCR data; (lower panels) hybridization results with the amplicons from the top panel. The isolates analyzed are indicated at the top, and the oligonucleotide probes used are indicated at the right. Isolates LP3, LP4, LP7, CA2, CA3, CA4, CA12, R100, JD1, 297, CA9, B31, T2, 272, B31T, NY186, and 25015 are B. burgdorferi; 21038 is B. andersonii; IP90, B491, and B691 are B. garinii; VS116 is B. valaisiana; Pko, UMO1, ECM1, Pbo, and Pgau are B. afzelii; and IKA2 is B. japonica.

Southern hybridization analyses of uhb(+)-E470(−) PCR amplicons with probes targeting previously identified ospE-related genes.

Since many of the uhb(+)-E470(−) amplicons were polymorphic in size, the identity of the amplified genes could not be inferred based upon migration in agarose gels. In addition, since ospE and the ospE paralogs erpA and erpI possess uhb(+) and E470(−) binding sites at analogous positions and would yield amplicons of the same size, it remained to be determined which of these genes were amplified. To aid in the identification of the polymorphic amplicons and to determine specifically which genes were being amplified, hybridization analyses of the amplicons were conducted. To determine if erpA (or erpI) was amplified, we used the erpA (erpI)-specific A468(−) oligonucleotide as a probe. The A468(−) probe hybridized with amplicons derived from only a few B. burgdorferi isolates (Fig. 2). The absence of hybridization of this probe with the amplicons implies that erpA (both copies) and erpI are possibly absent from the genome. Alternatively, it is conceivable, although unlikely, that all three erpA-related alleles (both copies of erpA and erpI) exhibit sequence divergence at the probe binding site in all A468(−) hybridization-negative isolates and therefore do not hybridize with the probe. The possible absence of these 5′ UHB-flanked alleles from most isolates is indirectly supported by the lower UHB element copy number observed in most isolates compared to that in B. burgdorferi B31T (6, 9).

The blot probed with the A468(−) primer was stripped and sequentially probed with other ospE paralog-targeting probes. The E13(+) probe, which targets the relatively conserved putative leader peptide of all ospE-related genes (except erpC, which is divergent within the probe binding site), hybridized with amplicons from 23 of the 28 PCR products tested. Some amplicons did not hybridize even under low-stringency conditions, indicating sequence divergence at their 5′ termini. The E46(+) probe, which targets within the 5′ ends of ospE, erpI, and erpA, hybridized with amplicons derived from nine B. burgdorferi isolates but not with amplicons derived from other species, indicating that this region of the amplicons is variable among isolates, with divergence being pronounced across species lines. The C241(−) and p21-105(−) probes, which target erpC and p21, respectively, were not predicted to hybridize with the uhb(+)-E470(−) amplicons, since both the erpC and p21 genes lack an E470(−) binding site and therefore should not be amplified. However, hybridization was observed with several B. burgdorferi-derived amplicons (p21 data are not shown). It is possible either that some erpC or p21 genes possess an E470(−) binding site or that sequences thought to be unique to erpC or p21 are present in other ospE paralogs. These data raised the possibility that there may be ospE paralogs that are composite or mosaic genes.

Although the amplicons were screened by hybridization with probes targeting all of the identified ospE paralogs, some amplicons did not hybridize with this collection of probes. Examples of hybridization-negative amplicons include those derived from B. burgdorferi R100 and JD1 and the larger of the two bands from B. burgdorferi 297 and 272 (all of which were identical in size). The absence of hybridization with the collection of probes used suggests that the amplified genes are divergent in sequence from other ospE paralogs. It can be concluded from these analyses that the uhb(+)-E470(−) amplicons are derived from a variable gene or group of genes and that there are additional ospE paralogs carried by some isolates that have not yet been characterized and reported on in the literature. To assess the molecular variation in these amplicons, several were cloned or purified and their sequences were determined.

DNA sequence analyses of the uhb(+)-E470(−) amplicons.

Selected uhb(+)-E470(−) amplicons were purified and sequenced. The determined sequences extend from approximately 120 bases upstream of the translational start codons to within approximately 40 bases 5′ of the stop codon (as inferred from the location of the known stop codon of ospE). Thus, the determined sequences are partial and are missing a small segment of their 3′ ends. To assess the relatedness between the coding regions of the amplicons, we conducted pairwise sequence comparisons by using the GAP program (default parameters). These nucleotide identity values ranged from 67.25 to 100% (Table 4). Excluding the amplicon sequence from B. burgdorferi JD1, which was found to be the most peripheral of the nucleotide sequences, nucleotide identity values at the intraspecies level ranged from 83 to 100%. The average nucleotide identity value for these sequences compared with the corresponding coding sequences of ospE, erpA, p21, and erpC (from B. burgdorferi N40 or B31T) were 86.4, 87.6, 85.5, and 86.1%, respectively, indicating that the amplified genes are evolutionarily equidistant from each of the previously described ospE-related genes. As a consequence, most of the amplified genes could not be assigned with certainty a gene name designation. It appears instead that several genes in the ospE subfamily of the UHB gene family are in a somewhat gray area regarding nomenclature. Rather than assign a new gene name to each, and in an attempt to simplify the somewhat complicated nomenclature of ospE-related genes, we refer to them simply as ospE paralogs.

TABLE 4.

Nucleotide sequence identity and amino acid similarity values of the uhb(+)-E470(−) amplicons from B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates and comparison with other UHB-flanked genes

| Isolate or gene | % Nucleotide identity or amino acid similaritya to:

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21038 | B31 | CA2 | CA3 | CA4 | CA9 | erpA | erpC | IP90 | LP3 | LP4 | ospE | p21 | VS116 | IKA2c2 | IKA2c3 | PGau | JD1 | |

| 21038 | 78.42 | 76.86 | 76.02 | 77.87 | 77.87 | 80.28 | 73.36 | 71.54 | 72.69 | 80.28 | 80.05 | 76.57 | 74.51 | 73.82 | 77.22 | 75.96 | 84.40 | |

| B31 | 71.53 | 85.88 | 83.06 | 87.47 | 87.47 | 98.14 | 87.70 | 74.48 | 87.00 | 98.14 | 89.33 | 84.94 | 78.59 | 76.87 | 79.58 | 76.33 | 71.26 | |

| CA2 | 72.55 | 85.21 | 91.78 | 86.50 | 86.50 | 87.29 | 88.47 | 73.97 | 86.82 | 87.29 | 87.06 | 99.13 | 77.14 | 82.00 | 77.66 | 76.48 | 70.40 | |

| CA3 | 70.51 | 82.64 | 92.86 | 83.62 | 83.62 | 84.92 | 87.56 | 75.53 | 87.56 | 84.92 | 86.31 | 91.60 | 75.60 | 79.58 | 77.22 | 76.08 | 79.02 | |

| CA4 | 76.97 | 84.72 | 84.77 | 79.74 | 100.0 | 88.86 | 87.24 | 74.68 | 87.47 | 88.86 | 92.34 | 85.62 | 76.87 | 79.67 | 76.64 | 76.92 | 73.19 | |

| CA9 | 76.97 | 84.72 | 84.77 | 79.74 | 100.0 | 88.86 | 87.24 | 74.68 | 87.47 | 88.86 | 92.34 | 85.62 | 76.87 | 79.67 | 76.64 | 76.92 | 73.19 | |

| erpA | 73.61 | 97.92 | 87.32 | 84.72 | 86.81 | 86.81 | 89.10 | 76.33 | 88.86 | 100.0 | 91.18 | 86.35 | 80.00 | 78.74 | 81.44 | 77.73 | 73.13 | |

| erpC | 73.65 | 86.11 | 90.14 | 88.97 | 86.81 | 86.81 | 88.19 | 75.17 | 98.46 | 89.10 | 87.00 | 89.02 | 78.82 | 80.97 | 83.41 | 77.80 | 74.15 | |

| IP90 | 71.60 | 75.69 | 74.03 | 72.61 | 74.52 | 74.52 | 77.73 | 74.34 | 75.34 | 76.33 | 76.57 | 73.49 | 81.76 | 83.76 | 83.08 | 85.57 | 69.57 | |

| LP3 | 73.65 | 85.42 | 89.44 | 88.97 | 86.11 | 86.11 | 87.50 | 99.34 | 74.34 | 88.86 | 87.00 | 87.33 | 78.12 | 80.28 | 83.18 | 77.14 | 74.15 | |

| LP4 | 73.61 | 97.92 | 87.32 | 84.72 | 86.81 | 86.81 | 100.0 | 88.19 | 77.78 | 87.50 | 91.18 | 86.35 | 80.00 | 78.74 | 81.44 | 77.73 | 73.13 | |

| ospE | 76.39 | 87.50 | 85.92 | 85.42 | 89.58 | 89.58 | 89.58 | 86.11 | 77.08 | 86.11 | 89.58 | 86.12 | 78.35 | 77.80 | 81.68 | 78.19 | 71.69 | |

| p21 | 71.43 | 83.80 | 98.70 | 92.99 | 83.44 | 83.44 | 85.92 | 90.21 | 72.90 | 89.51 | 85.92 | 84.51 | 77.36 | 80.94 | 77.36 | 76.86 | 69.72 | |

| VS116 | 71.05 | 74.65 | 73.69 | 75.66 | 72.37 | 72.37 | 76.76 | 78.17 | 84.21 | 78.17 | 76.76 | 76.76 | 73.68 | 84.83 | 84.96 | 81.64 | 67.25 | |

| IKA2c2 | 61.22 | 74.65 | 75.00 | 73.43 | 73.24 | 73.24 | 76.76 | 78.32 | 76.92 | 79.02 | 76.76 | 71.13 | 74.48 | 77.14 | 88.34 | 86.78 | 69.98 | |

| IKA2c3 | 62.00 | 73.43 | 73.33 | 70.59 | 72.85 | 72.85 | 75.52 | 77.78 | 77.78 | 78.47 | 75.52 | 73.43 | 71.24 | 75.33 | 83.92 | 87.42 | 69.72 | |

| PGau | 58.82 | 67.83 | 71.52 | 70.13 | 69.54 | 69.54 | 69.93 | 68.21 | 79.50 | 68.87 | 69.93 | 68.53 | 70.13 | 73.33 | 81.82 | 81.70 | 75.32 | |

| JD1 | 68.99 | 62.68 | 60.26 | 61.69 | 65.10 | 65.10 | 67.69 | 67.91 | 60.71 | 69.01 | 64.79 | 70.00 | 59.21 | 60.26 | 65.97 | 66.00 | 58.82 | |

Percent nucleotide identity values are presented in the upper half of the table, and percent amino acid similarity values are given in the lower half of the table. The p21 and erp sequences analyzed were previously determined by others; their accession numbers are provided in Table 1.

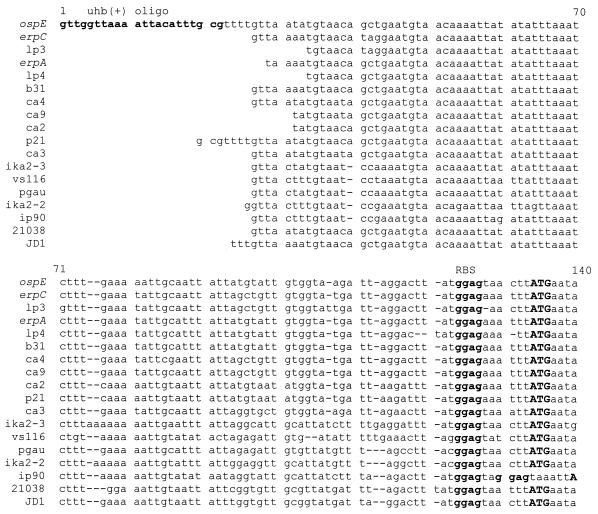

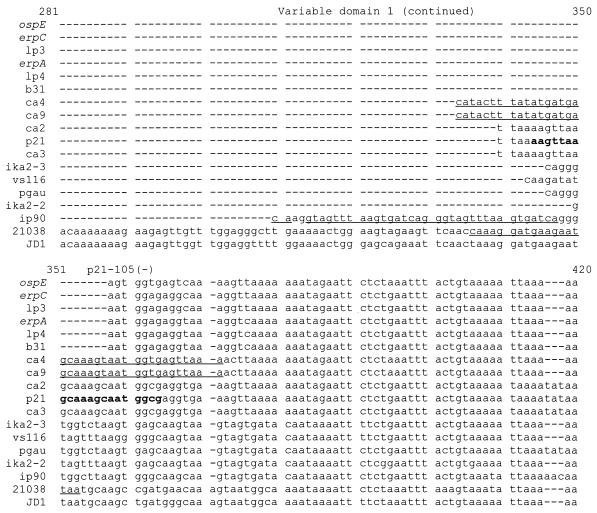

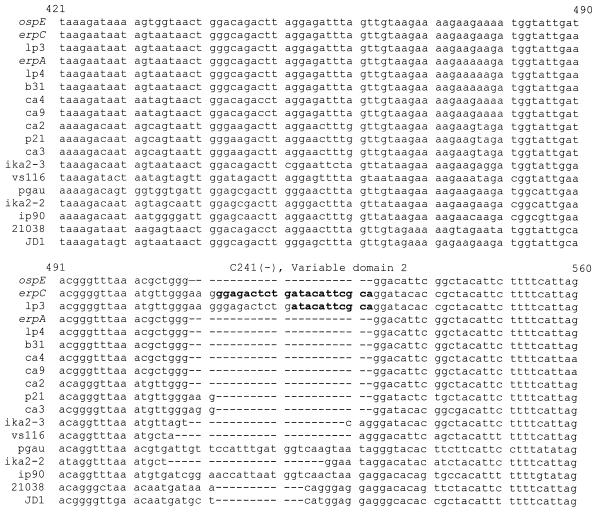

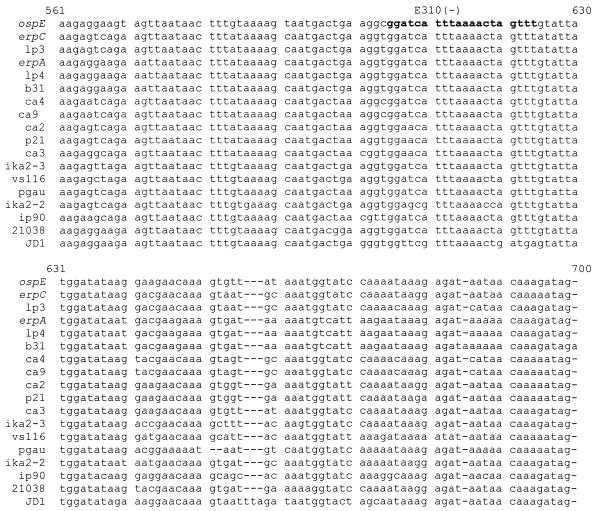

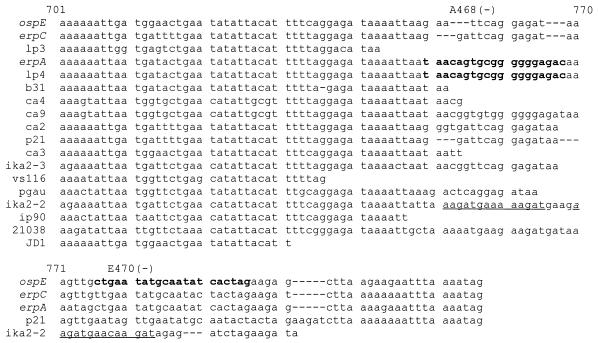

Alignment of the nucleotide sequences revealed a concentration of sequence variation between alignment positions 220 through 360 (variable domain 1). This domain is characterized by the presence of in-frame insertions and deletions, flanked in many isolates by direct repeat elements (Fig. 3). Some of the repeats are discussed here, while others are highlighted in Fig. 3. Relative to B. burgdorferi N40 ospE, the B. andersonii 21038 amplicon sequence carries an insertion of 102 nucleotides (nt) flanked by a 18-bp repeat containing three mismatches. At the same site in the CA4 and CA9 amplicons there is a 38-bp near-perfect repeat (37 of 38 nt) separated by 1 nt. In the IP90 amplicon this site carries a 34-bp repeat (32 of 34 nt) separated by 2 nt. A second interesting feature of the IP90 amplicon is a 6-nt tandem repeat in the 5′ end of the putative coding sequence which results in the presence of two potential ribosomal binding sites.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the uhb(+)-E470(−) amplicon nucleotide sequences. Sequences were aligned by using the PILEUP program with some manual adjustment. The isolates analyzed are indicated at the left. For comparative purposes some previously determined gene sequences (ospE, erpC, erpA, and p21) were included, and these are indicated by their designated gene names (for accession numbers, see Table 1). Gaps are indicated by dashes. The binding sites of some oligonucleotide probes and primers (indicated above the alignment) are in boldface. Repeat elements are indicated by underlining, and mismatches are indicated by capital letters. Putative ribosomal binding sites (RBS) and translational start codons are also indicated. Since some of these sequences are partial and lack their 3′ termini, stop codons are not shown for all sequences. The two different sequences from B. japonica IKA2 are the sequences determined for each of the two amplicons (ika2-2 and ika2-3) obtained from this isolate.

A second variable region occurs between positions 505 and 535 (variable domain 2). Diversity within this domain is significant yet is less pronounced than that seen in variable domain 1. At this site the B. burgdorferi LP3-derived amplicon carries a 24-nt insertion (relative to ospE of B. burgdorferi N40) identical in sequence to the insertion present in erpC of B. burgdorferi B31T. The B. burgdorferi CA3 and N40 amplicon sequences carry a 3-nt insertion at this position. B. afzelii PGau and B. garinii IP90 carry a similar 24-nt insertion (63% identity with each other) that is not related to the insertion observed in LP3. B. andersonii 21038 harbors a unique 12-bp insertion at this site. In contrast to domain 1, domain 2 is not flanked by repeat elements.

Sequence analysis of the amplicons that were hybridization negative with the various ospE paralog-targeting probes (as described above) revealed these sequences to be among the most divergent of the ospE paralogs. Near-complete sequences for the 297, 272, and R100 amplicons and a complete sequence for the JD1 amplicon were determined. These sequences were found to be identical to each other, and in light of this, we focus our discussion on the amplicon sequence from B. burgdorferi JD1. Of all ospE-related genes characterized thus far, this variant is most peripheral to the group in terms of sequence conservation. Its nucleotide identity with other ospE paralogs ranges from 67.25 to 84.40%. Like other ospE-related genes, it is polymorphic within variable domain 1. Relative to B. burgdorferi N40 ospE, it carries an insertion of 122 nt which is followed just downstream by a single-base insertion that restores the reading frame. Interestingly, the terminal 92 nt of the insertion exhibit 90% identity with the insertion present in the B. andersonii 21038 amplicon sequence. Particularly notable is the homology between the 5′ end of the insertion (and a small segment of its 5′ flanking sequence) and another member of the UHB gene family, erpK. The gene from which this amplicon was derived appears to be a composite gene carrying segments of at least two UHB gene family members.

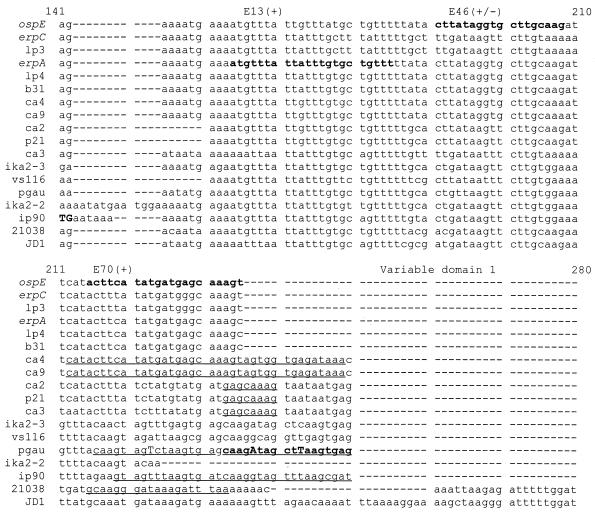

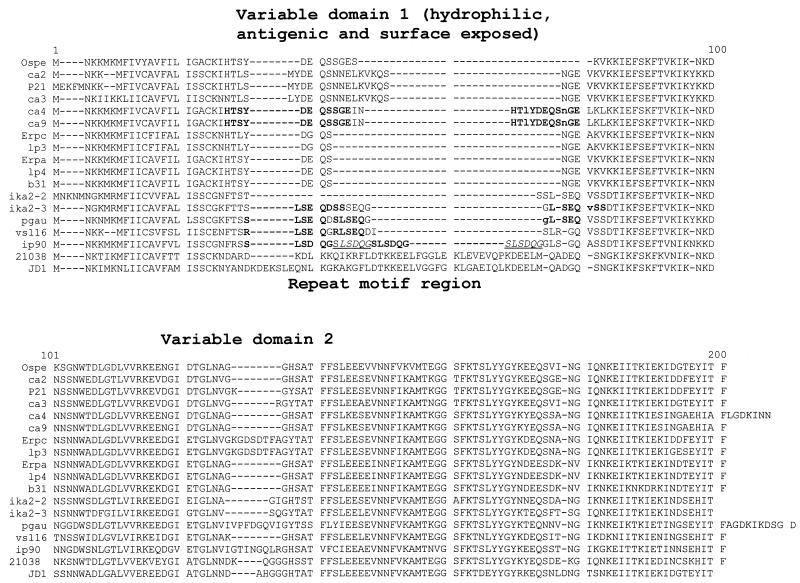

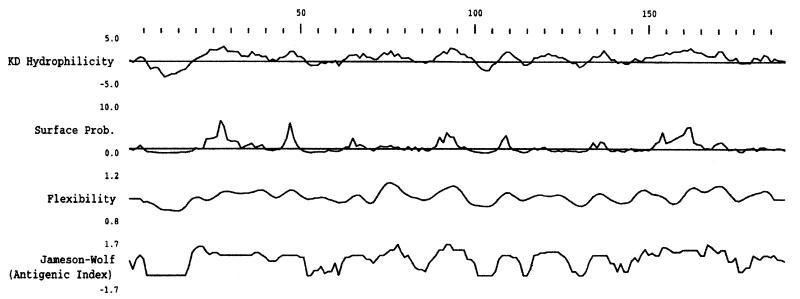

To compare the putative proteins encoded by the ospE amplicon sequences, the partial nucleotide sequences were translated and aligned (Fig. 4). To assess the relatedness of the translated sequences, pairwise sequence comparisons were performed (Table 4). These values ranged from 58.8% similarity to 100% identity, demonstrating that all are clearly members of a single gene family. Analysis of the deduced amino acid sequences revealed several noteworthy features. All carry a relatively conserved, hydrophobic putative leader peptide of 15 to 20 amino acids and an amino acid motif similar to the proposed signal peptidase II site of OspE (LIGAC) (14). Just downstream of the putative leader peptide within variable domain 1 of some isolates are amino acid repeat motifs of various lengths and sequences. It should be noted that not all sequences that carry repeats at the nucleotide level exhibit repeats at the amino acid level. In B. garinii IP90 the sequence SLSDQG is perfectly and tandemly repeated four times. To assess the physical properties of the deduced amino acid sequences, the sequences were analyzed for hydrophobicity-hydrophilicity, surface exposure, and antigenicity. Computer analyses (12, 13) predict variable domain 1 of each ospE variant to be hydrophilic, surface exposed, and potentially antigenic. The output from the analyses conducted for one representative amplicon sequence (that from B. burgdorferi JD1) is depicted in Fig. 5. The potential antigenicity of variable domain 1 may indicate an important functional role, perhaps in immune evasion.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences. The amino acid alignment was generated as described in the text with some manual adjustment. The isolate from which a sequence was obtained is indicated at the left. Some previously determined sequences (6, 8, 20, 25) were included in the alignment, and the corresponding protein names are indicated on the left. Repeat motifs are indicated by boldface. In cases where the repeats are tandem, alternating copies are indicated by italics and underlining. Mismatches among the repeat elements are indicated by lowercase letters.

FIG. 5.

Computer analysis of the possible physical properties of the deduced amino acid sequence of the B. burgdorferi JD1 ospE-related amplicon. The output from analyses conducted by using the Genetics Computer Group, Wisconsin, Sequence Analysis Package, version 9.0, as described in the text, is shown. In all cases default values were used. Variable domain 1 spans residues 20 through 75. KD, Kyte-Doolittle; Prob., probability.

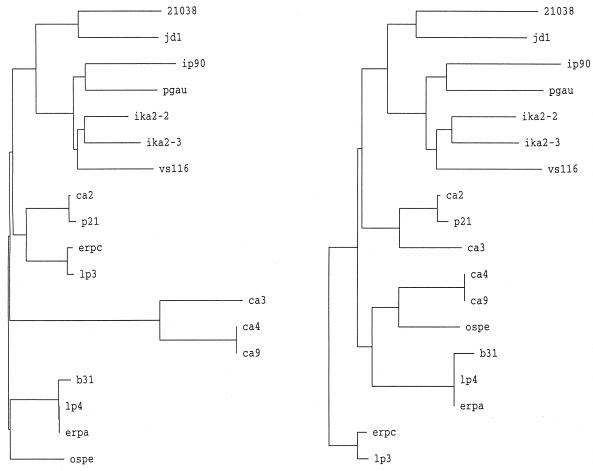

To further assess the relationships among the translated sequences, we constructed a series of phylograms. Two alignments were generated for this purpose. The first alignment included the entire sequences (as shown in Fig. 4, except that they were truncated at position 200 to have a common endpoint). In the second alignment, variable domains 1 and 2 were deleted. This was done to assess the influence of the putative insertions and deletions on the clustering patterns and branch lengths. Comparison of the phylograms obtained with these two alignments (Fig. 6) revealed that the variable domains influence the clustering patterns and, not surprisingly, the branch lengths. This observation indicates that the variable domains are not evolutionarily stable. Hence, while all of the analyzed sequences are clearly derived from a common ancestral gene, it is evident that the variable domains have been influenced by recent molecular events. Hence, the overall gene trees have been influenced by events that appear to have included rearrangements and recombination (i.e., insertions, deletions, and/or gene fusions). Consistent with this, we previously provided evidence for the existence of gene fusions between ospE and ospF in some B. burgdorferi isolates (20).

FIG. 6.

Phylograms of ospE-related genes. Phylograms were constructed by using the translated amplicon sequences determined in this study and other, previously determined sequences as described in Materials and Methods. The isolate from which a particular amplicon was obtained is indicated at the terminus of the branch. The designations p21 (26), ospE (14), and erpA and erpC (25) indicate gene names, and these sequences were previously determined by others. The phylogram on the left was constructed by using the alignment presented in Fig. 4, while the phylogram on the right was constructed by using the same alignment after deletion of variable domains 1 and 2. Note that some clustering relationships changed as a result of deletion of the variable domains.

DISCUSSION

In light of the putative role of members of the UHB gene family in adaptation to the mammalian environment or in virulence (1, 8, 26), an assessment of their genetic variability and distribution is an important step towards defining their potential biological role and true biological significance. Here we demonstrate that while the UHB gene family is universal among B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex species, there is significant variation in its composition and organization at both the inter- and intraspecies levels as evidenced by the observed RFLP patterns and polymorphic UHB gene family-derived PCR amplicons. The UHB RFLP patterns do not reflect patterns of phylogenetic divergence in the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex (2, 3, 15–17), suggesting that this gene family is evolutionarily unstable and that recombination in and among these genes has influenced their sequence and organization. As a result, the organization of this gene family as originally described for B. burgdorferi B31T (6, 25) may not serve as a universal model for its organization in other isolates.

The RFLP pattern and PCR analyses demonstrated that members of the ospE subfamily of the UHB gene family are polymorphic, and to identify the molecular basis for these polymorphisms, DNA sequence analyses were performed. Although the uhb(+)-E470(−) amplicons exhibit relatively high sequence identity values, defined domains of variability were identified. Variable domain 1 is characterized by the presence of variable-length direct repeat elements (some as long as 38 bp) and insertions (relative to the B. burgdorferi N40 ospE sequence). In light of the clustering of these repeats around variable domain 1, it is conceivable that the repeats have contributed to or resulted from mutation or recombination. Evidence for recent molecular rearrangements in variable domain 1 was obtained through the construction of phylograms. Computer analyses of the deduced amino acid sequences within variable domain 1 predict them to be hydrophilic and antigenic. Surface exposure of this region is predicted for all sequences except that from B. garinii IP90. It is conceivable that through the differential expression of these variable genes, the Lyme disease spirochetes might be able to vary their antigenic profiles. Recombination in the variable domains could represent a mechanism that allows for the continual modification of these surface-exposed proteins, and this in turn could influence the host-pathogen interaction.

The relatively high sequence identities of the uhb(+)-E470(−) amplicon sequences with ospE, erpA, erpC, and p21 imply that all of these genes are derived from a common ancestral gene. Most of the sequences determined here could not be definitively assigned any of the previously proposed gene name designations (i.e., erpA, erpC, erpI, and p21), since they are evolutionarily equidistant from each gene. In light of this, it is unclear if the designations that have been assigned to ospE-related genes are useful. While the cp32s of B. burgdorferi B31T, which carry some ospE-related genes, can be differentiated through complex restriction analyses and subsequent Southern blotting (6), the data presented here demonstrate that differentiation of the ospE paralogs themselves in other isolate populations would not be straightforward. In view of these considerations, we have opted not to assign new gene name designations for the novel ospE-related genes described in this report and instead refer to them only as ospE paralogs. The analyses presented here strongly suggest that ospE, p21, erpA, erpC, and erpI are genetically synonymous. In cases where the full complement of ospE paralogs within an isogeneic isolate are defined, numerical qualifiers could prove useful for their differentiation, e.g., ospE1 and ospE2, etc., as has been done for the B. burgdorferi vls genes (28).

The specific molecular mechanisms by which genetic diversity is generated in ospE-related genes remain to be determined. The presence of direct repeat elements in many of the sequences flanking variable domain 1 is intriguing. It is conceivable that diversity in defined domains of ospE-related genes could arise from transposition, mutation, or recombination or perhaps through the exchange of sequence cassettes. Suggestive evidence for gene mosaicism can be found in the sequence of the ospE-related amplicon from B. burgdorferi JD1, which harbors sequence blocks with high identity to segments of B. burgdorferi B31T erpK and the insertion element of the B. andersonii 21038 amplicon. Although the pressures that may drive putative gene mosiacism in the UHB gene family are undefined, it has been demonstrated that the exchange of sequence cassettes among related sequences plays a key role in the generation of antigenic diversity in the vls genes of B. burgdorferi (28) and the pil genes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (10). We have previously presented evidence for the lateral transfer of plasmids among species of the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex (19). If lateral transfer of UHB-flanked ospE variant-carrying plasmids also occurs, this could generate a source of ospE-related DNA that could participate in homologous recombination increasing the potential number of possible ospE paralogs. While evidence for direct recombination in the UHB gene family during in vitro cultivation has not yet been demonstrated, the data presented here suggest that in natural populations recombination or mutation has occurred and has been a contributing factor to the organization, composition, and sequence of the UHB gene family. Long-term studies are under way to assess the frequency of recombination or mutation in the ospE subfamily in isogeneic clones of B. burgdorferi during infection in mice. The significance of mutation and/or recombination in these genes and its influence on the biology of these important pathogens represents the next important area to be assessed in the study of the UHB gene family.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge our colleagues in the Molecular Pathogenesis group at Virginia Commonwealth University for their input and helpful discussions and the many individuals who contributed isolates which have made these analyses possible.

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (5R29AI37787) and the Jeffress Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akins D, Porcella S F, Popova T G, Shevchenko D, Baker S I, Li M, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Evidence for in vivo but not in vitro expression of a Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein F (OspF) homologue. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:507–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assous M V, Postic D, Paul G, Nevot P, Baranton G. Individualization of two new genomic groups among American Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baranton G, Postic D, Saint Girons I, Boerlin P, Piffaretti J-C, Assous M, Grimont P A D. Delineation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia garinii sp. nov., and group VS461 associated with Lyme borreliosis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:378–383. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbour A G, Carter C J, Bundoc V, Hinnebusch J. The nucleotide sequence of a linear plasmid of Borrelia burgdorferi reveals similarities to those of circular plasmids of other prokaryotes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6635–6639. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6635-6639.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlyon J A, LaVoie C, Sung S Y, Marconi R T. Analysis of the organization of multicopy linear and circular plasmid-carried open reading frames in Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolates. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1149–1158. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1149-1158.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casjens S, van Vugt R, Tilly K, Rosa P A, Stevenson B. Homology throughout the multiple 32-kilobase circular plasmids in Lyme disease spirochetes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:217–227. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.217-227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Champion C I, Blanco D R, Skare J T, Haake D A, Giladi M, Foley D, Miller J N, Lovett M A. A 9.0-kilobase-pair circular plasmid of Borrelia burgdorferi encodes an exported protein: evidence for expression only during infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2653–2661. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2653-2661.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das S, Barthold S W, Giles S S, Montgomery R R, Telford III S R, Fikrig E. Temporal pattern of Borrelia burgdorferi p21 expression in ticks and the mammalian host. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:987–995. doi: 10.1172/JCI119264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser C, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum K A, Dodson R, Hickey E K, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J F, Fleischman R D, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage A R, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams M D, Gocayne J, Weidman J, Utterback T, Watthey L, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Garland S, Cotton F C M C, Horst K, Roberts K, Hatch B, Smith H O, Venter J C. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagblom P, Segal E, Billyard E, So M. Intragenic recombination leads to leads to pilus antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;315:156–158. doi: 10.1038/315156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinnebusch J, Barbour A G. Linear plasmids of Borrelia burgdorferi have a telomeric structure and sequence similar to those of a eukaryotic virus. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7233–7239. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7233-7239.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopp T P, Woods K R. Prediction of protein antigenic determinants from amino acid sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:3824–3828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jameson B A, Wolf H. The antigenic index: a novel algorithm for predicting antigenic determinants. CABIOS. 1988;4:181–186. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/4.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam T T, Nguyen T-P K, Montgomery R R, Kantor F S, Fikrig E, Flavell R A. Outer surface proteins E and F of Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent of Lyme disease. Infect Immun. 1994;62:290–298. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.290-298.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marconi R T, Garon C F. Identification of a third genomic group of Borrelia burgdorferi through signature nucleotide analysis and 16S rRNA sequence determination. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:533–536. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-3-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marconi R T, Garon C F. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Borrelia: a comparison of North American and European isolates of B. burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:241–244. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.241-244.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marconi R T, Liveris D, Schwartz I. Identification of novel insertion elements, restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns, and discontinuous 23S rRNA in Lyme disease spirochetes: phylogenetic analyses of rRNA genes and their intergenic spacers in Borrelia japonica sp. nov. and genomic group 21038 (Borrelia andersonii sp. nov.) isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2427–2434. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2427-2434.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marconi R T, Samuels D S, Garon C F. Transcriptional analyses and mapping of the ospC gene in Lyme disease spirochetes. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:926–932. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.926-932.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marconi R T, Samuels D S, Landry R K, Garon C F. Analysis of the distribution and molecular heterogeneity of the ospD gene among the Lyme disease spirochetes: evidence for lateral gene exchange. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4572–4582. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4572-4582.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marconi R T, Sung S Y, Hughes C N, Carlyon J A. Molecular and evolutionary analyses of a variable series of genes in Borrelia burgdorferi that are related to ospE and ospF, constitute a gene family, and share a common upstream homology box. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5615–5626. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5615-5626.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marconi R T, Wigboldus J, Weissbach H, Brot N. Transcriptional start site and MetR binding sites on the Escherichia coli met H gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;175:1057–1063. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91672-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porcella S F, Popova T G, Akins D R, Li M, Radolf J R, Norgard M V. Borrelia burgdorferi supercoiled plasmids encode multicopy open reading frames and a lipoprotein gene family. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3293–3307. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3293-3307.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz J J, Gazumyan A, Schwartz I. rRNA gene organization in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3757–3765. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3757-3765.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson W J, Garon C F, Schwan T G. Analysis of supercoiled circular plasmids in infectious and non-infectious Borrelia burgdorferi. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevenson B, Tilly K, Rosa P A. A family of genes located on four separate 32-kilobase circular plasmids in Borrelia burgdorferi B31. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3508–3516. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3508-3516.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suk K, Das S, Sun W, Jwang B, Barthold S W, Flavell R A, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi genes selectively expressed in the infected host. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4269–4273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallich R, Brenner C, Kramer M D, Simon M M. Molecular cloning and immunological characterization of a novel linear-plasmid-encoded gene, pG, of Borrelia burgdorferi expressed only in vivo. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3327–3335. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3327-3335.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J-R, Hardham J M, Barbour A G, Norris A G. Antigenic variation in Lyme disease borreliae by promiscuous recombination of vmp like sequence cassettes. Cell. 1997;89:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zuckert W R, Meyer J. Circular and linear plasmids of Lyme disease spirochetes have extensive homology: characterization of a repeated DNA element. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2287–2298. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2287-2298.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]