Abstract

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a potent inflammatory stimulus derived from the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, has been implicated in septic shock. Plasma levels of adrenomedullin (AM), a potent vasorelaxant, are increased in septic shock and possibly contribute to the characteristic hypotension. As macrophages play a central role in the host response to LPS, we studied AM production by LPS-stimulated macrophages. When peritoneal exudate macrophages from C3H/OuJ mice were treated with protein-free LPS (100 ng/ml) or the LPS mimetic paclitaxel (Taxol; 35 μM), an ∼10-fold increase in steady-state AM mRNA levels was observed, which peaked between 2 and 4 h. A three- to fourfold maximum increase in the levels of immunoreactive AM protein was detected after 6 to 8 h of stimulation. While LPS-hyporesponsive C3H/HeJ macrophages failed to respond to protein-free LPS with an increase in steady-state AM mRNA levels, increased levels were observed after stimulation of these cells with a protein-rich (butanol-extracted) LPS preparation. In addition, increased AM mRNA was observed following treatment of either C3H/OuJ or C3H/HeJ macrophages with soluble Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoite antigen or the synthetic flavone analog 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid. Gamma interferon also stimulated C3H/OuJ macrophages to express increased AM mRNA levels yet was inhibitory in the presence of LPS or paclitaxel. In vivo, mice challenged intraperitoneally with 25 μg of LPS exhibited increased AM mRNA levels in the lungs, liver, and spleen; the greatest increase (>50-fold) was observed in the liver and lungs. Thus, AM is produced, by murine macrophages, and furthermore, LPS induces AM mRNA in vivo in a number of tissues. These data support a possible role for AM in the pathophysiology of sepsis and septic shock.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a potent inflammatory stimulus derived from the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. Release of LPS from dying bacteria can initiate a serious systemic inflammatory response to infection, resulting in septic shock. Septic shock is typified by fever, hypoglycemia, hypotension, disseminated intravascular coagulation, multiorgan failure, and shock that may result in death (5, 33, 34). Septic shock continues to have an associated mortality rate of 40 to 70% and remains the leading cause of death in intensive care units (1, 33, 34). The interaction of LPS with host cells initiates the production of a cascade of proinflammatory mediators that are responsible for its effects (25). The release of cytokines like tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-12, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), nitric oxide (NO·), and colony-stimulating factor from monocytes and macrophages elicits the physiologic changes observed during sepsis and septic shock (25, 30, 34, 40). The antitumor agent paclitaxel (Taxol) is an LPS mimetic in murine macrophages. Shared activities include the ability to activate murine macrophages to express a wide variety of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory genes, tyrosine phosphorylate mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), secrete cytokines, induce translocation of NF-κB, and upregulate autophosphorylation of Lyn kinase. In addition, paclitaxel provides a second signal to IFN-γ-primed murine macrophages to become tumoricidal and to produce NO· (8, 11, 22, 24, 36). Macrophage responsiveness to both LPS and paclitaxel is linked to the Lps gene. The C3H/HeJ mouse strain expresses a defective allele at this locus, and macrophages derived from this mouse strain are hyporesponsive not only to LPS (45) but also to paclitaxel (22, 24).

Adrenomedullin (AM) is a hypotension-causing peptide that was originally isolated from human pheochromocytoma cells (19). It induces vasorelaxation that leads to a persistent depression of blood pressure (15). In previous studies, AM mRNA was found to be expressed in various organs, including the cardiovascular system, lungs, adrenal glands, cultured endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, alveolar and endometrial macrophages, and virtually all of the tumor cell lines examined (19, 27, 29, 38, 43, 44, 48). Moreover, AM was recently demonstrated to exhibit direct antimicrobial activity (46). The concentration of AM in plasma is increased in patients with hypertension, septic shock, and heart failure, suggesting that AM may participate in the regulation of blood pressure and contribute to refractory hypotension in septic shock (14, 18). Given the plethora of bioactive peptides released by LPS-activated macrophages, we postulated that AM may also be produced by macrophages in response to LPS as a result of gram-negative infection and, perhaps, contribute to the hypotension associated with gram-negative sepsis and septic shock. In the present study, we demonstrated that LPS and paclitaxel, as well as other potent macrophage stimuli, induce AM mRNA and protein expression in murine peritoneal macrophages. Additionally, AM mRNA levels were upregulated in the lungs, liver, and spleen following LPS injection.

(This work was presented in part as a poster at the NCI Adrenomedullin Symposium, 3 to 5 September 1997, Bethesda, Md.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Phenol-water-extracted Escherichia coli K235 LPS (PW-LPS; <0.008% protein) was prepared by the method of McIntire et al. (28). Protein-rich, butanol-extracted E. coli K235 LPS (But-LPS; ∼18% protein) was prepared as described by Morrison and Leive (31). Paclitaxel was kindly provided by the Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch, Developmental Therapeutics Program, Division of Cancer Treatment, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md., and was stored at −70°C as a 20 mM stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide. A 1 mM stock of paclitaxel contained <0.03 endotoxin U/ml by the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay. 5,6-Dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (5,6-MeXAA) was synthesized by the Cancer Research Laboratory, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand (2, 37). A stock solution of 5,6-MeXAA was freshly prepared for each experiment by solubilizing the compound in sterile, endotoxin-free 5% NaHCO3 by vortexing. Once solubilized, the solution was diluted in supplemented RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% fetal calf serum to obtain a 10-mg/ml stock solution that was then diluted to the required concentration for macrophage stimulation. The endotoxin level of the highest concentration of 5,6-MeXAA used in these experiments was <0.0125 ng/ml as detected by the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay. A soluble extract of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites (STAg) was a gift from Alan Sher, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. Recombinant murine IFN-γ (1.3 × 107 U/ml) was kindly provided by Genentech, Inc. (South San Francisco, Calif.). Cycloheximide (CHX) was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.) and used at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml.

Mice.

For in vivo analysis of AM gene induction, 6- to 8-week-old C57BL/6J mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 25 μg of LPS. Four mice were used per time point per treatment. GKO mice were a gift from Genentech, Inc. (7).

Macrophage isolation and cell culture conditions.

Five- to 6-week-old female C3H/OuJ and C3H/HeJ mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine), maintained in a laminar-flow facility under 12-h alternating light-dark cycles, and fed standard laboratory chow and acid water ad libitum. Research was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (13a). Mice were injected i.p. with 3 ml of 3% fluid thioglycolate. Four days later, peritoneal exudate cells were extracted by peritoneal lavage. Cells were washed once with and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 100-U/ml penicillin, 100-μg/ml streptomycin, 10 mM HEPES, 0.3% sodium bicarbonate, and 2% fetal calf serum and added to six-well tissue culture plates (Falcon, Lincoln Park, N.J.) at ∼4.0 × 106 cells per well in a final volume of 2.0 ml. The plates were incubated at 37°C and 6% CO2. After a 12-h adherence period, nonadherent cells were washed off and the adherent macrophages were treated with 2.0 ml of medium or medium containing the indicated substances. For detection of AM in culture supernatants, macrophages were cultured at ∼6 × 106 cells per well in six-well tissue culture plates in a total volume of 3.0 ml, and supernatants were collected at the indicated times after stimulation with LPS or paclitaxel.

Isolation of total cellular RNA.

For in vitro experiments, culture supernatants were removed and the cells were solubilized in 1 ml of RNA Stat60 (Tel-Test ’B,’ Inc., Friendswood, Tex.). For in vivo experiments, the liver, lungs, and spleen were removed from individual mice and frozen at −70°C. Tissues were homogenized in RNA Stat60. Total cellular RNA was extracted from in vitro and in vivo samples in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions and quantified by spectrophotometric analysis.

Analysis of tissue mRNA by RT-PCR.

Relative quantities of mRNAs for hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and AM were determined by a coupled reverse transcription (RT)-PCR as detailed elsewhere (9). For the AM gene, the following oligonucleotide sequences were used: sense, 5′-AAGAAGTGGAATAAGTGGGCG; antisense, 5′-ACCAGATCTACCAGCTAACA; probe, 5′-CCCCCTACAAGCCAGCAATCAG.

Primer sequences for the detection of AM mRNA were chosen by analysis of the murine genomic sequence and amplify a 284-bp product. The probe sequence for AM was chosen in conjunction with the published murine cDNA sequences obtained from GenBank. Primer and probe sequences for the HPRT and GAPDH housekeeping genes have been reported (3). The PCR annealing temperatures were 54, 55, and 54°C for HPRT, GAPDH, and AM, respectively. The numbers of PCR cycles were 28 and 35 for in vitro and in vivo AM induction, respectively. The number of PCR cycles for both HPRT and GAPDH was 24. Amplified products were analyzed by electrophoresis, followed by Southern blotting and hybridization with the nonradioactive internal oligonucleotide probe. Chemiluminescence signals were quantified by using a scanning densitometer (Datacopy GS plus; Xerox Imaging Systems, Sunnyvale, Calif.). To determine the magnitude of change in gene expression, cDNA from a sample known to be positive for AM and HPRT or GAPDH was used to generate standard curves by serial twofold dilution of the positive control and simultaneous amplification. The signal of each band in the standard curve was plotted and subjected to linear regression analysis. The equation from this line was used to calculate the fold induction in test samples. Results were normalized for the relative quantity of mRNA by comparison to HPRT or GAPDH. In each in vitro experiment, means are expressed relative to medium controls. In vivo, means are expressed relative to saline-injected controls (t = 0), which were assigned a value of 1.

Detection of AM in macrophage culture supernatants.

Levels of immunoreactive AM were detected in macrophage culture supernatants by radioimmunoassay (RIA) as described previously (26).

Statistics.

Results were analyzed by using Student’s t test for comparisons between two groups.

RESULTS

AM mRNA and protein induced by PW-LPS or paclitaxel in murine macrophages.

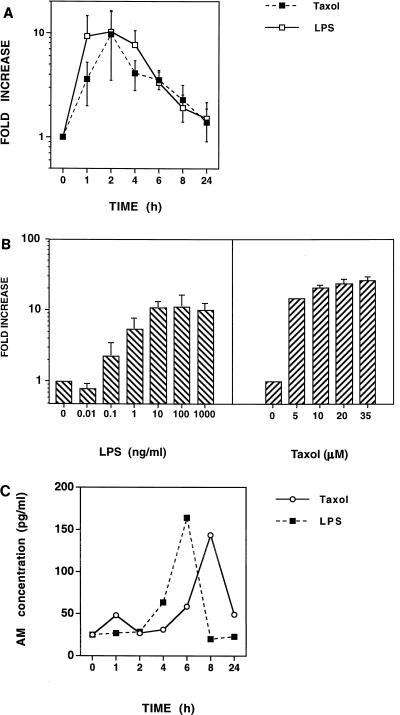

Previous studies have demonstrated that LPS induces AM mRNA and protein expression in cultured rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells (42) and in cultured endothelial cells (41). In the present study, we investigated if AM mRNA expression and protein secretion are modulated in murine macrophages by PW-LPS or by the LPS mimetic paclitaxel. Endotoxin-responsive C3H/OuJ macrophages were treated for 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h with medium alone, 100-ng/ml PW-LPS, or 35 μM paclitaxel. RNA was isolated, and AM and HPRT mRNAs were detected by RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 1A, the kinetics of AM gene induction by PW-LPS and paclitaxel were remarkably similar, with AM mRNA expression being induced by PW-LPS or paclitaxel as early as 1 h, peaking at 2 h (>10-fold over the baseline), and gradually returning to basal levels by 24 h. To assess the sensitivity of AM mRNA to induction by PW-LPS or paclitaxel, dose-response analyses were performed (Fig. 1B). Murine C3H/OuJ peritoneal macrophages were treated for 2 h, the time when AM mRNA expression had peaked, with various concentrations of PW-LPS or paclitaxel. RNA was isolated, and AM and HPRT mRNAs were detected by RT-PCR. As little as 0.1-ng/ml PW-LPS induced AM mRNA expression (>2-fold), while ≥10-ng/ml PW-LPS was necessary to induce maximal (>10-fold) AM mRNA expression. A comparable increase in AM gene expression was induced by 5 to 35 μM paclitaxel. Macrophage culture supernatants were also analyzed by RIA for the presence of immunoreactive AM. Figure 1C illustrates that both LPS and paclitaxel induce AM secretion several hours after the appearance of AM mRNA, with a maximal induction of three- to fourfold over the basal levels.

FIG. 1.

PW-LPS and paclitaxel induce AM mRNA and protein synthesis in C3H/OuJ macrophages. (A) Kinetics of PW-LPS- and paclitaxel-induced AM mRNA expression. C3H/OuJ macrophages were cultured for the indicated times with medium, 100-ng/ml PW-LPS, or 35 μM paclitaxel. mRNA was isolated, and AM and HPRT mRNAs were detected by RT-PCR. The data represent the arithmetic mean ± the standard error of the mean (seven separate experiments). (B) Dose-dependent induction of AM mRNA. C3H/OuJ macrophages were cultured for 2 h with medium or with the indicated concentrations of PW-LPS or paclitaxel. mRNA was isolated, and AM and HPRT mRNAs were detected by RT-PCR. The data represent the arithmetic mean ± the standard error of the mean (four separate experiments). (C) Kinetics of PW-LPS- and paclitaxel-induced AM secretion. C3H/OuJ macrophages were cultured for the indicated times with medium, 100-ng/ml LPS, or 35 μM paclitaxel. Macrophage culture supernatants were analyzed by RIA for the presence of immunoreactive AM. Data were derived from a representative of three experiments. When not visible, bars indicating the standard error of the mean are smaller than the symbol.

PW-LPS- or paclitaxel-induced AM mRNA requires a normal Lps gene product.

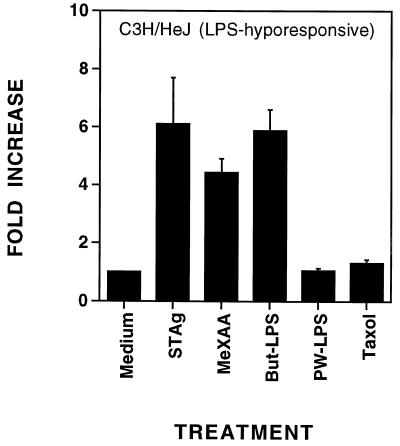

Previous studies in our laboratory have demonstrated the induction of an extensive panel of inflammatory genes (e.g., those for TNF-α, IL-1β, TNF receptor type 2, IFN-inducible protein 10, D3, and D8) by various LPS preparations or paclitaxel in macrophages derived from LPS-responsive (Lpsn) C3H/OuJ mice (22, 45). In contrast, macrophages derived from LPS-hyporesponsive (Lpsd) C3H/HeJ mice failed to express any of the above genes in response to either PW-LPS or paclitaxel. Despite their inability to respond to PW-LPS, C3H/HeJ macrophages are responsive to But-LPS, the product of a milder extraction process in which LPS remains associated with membrane proteins. Moreover, C3H/HeJ and C3H/OuJ macrophages exhibit comparable sensitivity to endotoxin-associated proteins isolated from protein-rich LPS preparations (12) and to STAg. Both protein-rich LPS and STAg result in tyrosine phosphorylation of MAPK and induce a subset of LPS-regulated genes (21). The antitumor agent 5,6-MeXAA is also active on both C3H/HeJ and C3H/OuJ macrophages (35). Therefore, we next investigated whether any of these agents would induce AM gene expression in C3H/HeJ macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages from C3H/HeJ mice were treated with medium alone, 50-μg/ml STAg, 10-μg/ml 5,6-MeXAA, 10-μg/ml But-LPS, 100-ng/ml PW-LPS, or 35 μM paclitaxel for 2 or 4 h. These concentrations were chosen based on optimal induction of gene expression by these agents in previous studies (12, 21, 35). RNA was isolated, and AM and HPRT mRNA levels were quantified. At 2 h, only STAg and But-LPS, but not 5,6-MeXAA, had significantly increased AM gene expression (sixfold or more; data not shown). As expected, neither PW-LPS nor paclitaxel induced AM mRNA in C3H/HeJ macrophages (Fig. 2). By 4 h, STAg, But-LPS, and 5,6-MeXAA had increased AM gene expression in C3H/HeJ macrophages greater than four- to sixfold over the baseline (Fig. 2). LPS-responsive macrophages from C3H/OuJ mice also responded to PW-LPS, paclitaxel, STAg, or 5,6-MeXAA by expressing heightened levels of AM mRNA (>10-fold) (data not shown). These data indicate that although the Lpsd allele precludes induction of AM mRNA by PW-LPS or paclitaxel, these cells respond to STAg, 5,6-MeXAA, and But-LPS with increased expression of AM mRNA.

FIG. 2.

Neither PW-LPS nor paclitaxel induced AM gene expression in LPS-hyporesponsive C3H/HeJ macrophages in vitro. C3H/HeJ macrophages were treated for 4 h with medium, 5-μg/ml STAg, 10-μg/ml MeXAA, 5-μg/ml But-LPS, 100-ng/ml PW-LPS, or 35 μM paclitaxel. The data represent the arithmetic mean ± the standard error of the mean of four experiments. When not visible, bars indicating the standard error of the mean are smaller than the symbol.

Expression of AM mRNA in macrophages treated with CHX.

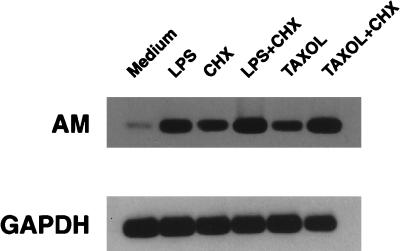

To determine whether induction of AM mRNA by LPS or paclitaxel requires de novo protein synthesis, C3H/OuJ macrophages were treated for 2 h with medium, 100-ng/ml PW-LPS, or 35 μM paclitaxel, in the absence or presence of a 5-μg/ml concentration of the protein synthesis inhibitor CHX. This concentration of CHX has been shown previously to inhibit the expression of other LPS-inducible genes in C3H/OuJ macrophages (3). RNA was isolated, and both AM and GAPDH mRNAs were detected by RT-PCR (Fig. 3). CHX alone induced accumulation of steady-state AM mRNA. In addition, higher steady-state AM mRNA levels were observed after macrophages were treated for 2 h either with PW-LPS and CHX or with paclitaxel and CHX (Fig. 3). Thus, accumulation of AM mRNA is not dependent on de novo protein synthesis.

FIG. 3.

De novo protein synthesis is not required for PW-LPS- or paclitaxel-induced AM mRNA production. C3H/OuJ macrophages were treated for 2 h with either medium, 100-ng/ml PW-LPS, 5-μg/ml CHX, both 100-ng/ml PW-LPS and 5-μg/ml CHX, 35 μM paclitaxel, or both 35 μM paclitaxel and 5-μg/ml CHX. RNA was isolated, and AM and GAPDH mRNAs were detected by RT-PCR. A representative of three Southern blots is shown.

IFN-γ upregulates AM mRNA expression and negatively regulates LPS- and paclitaxel-induced AM mRNA expression.

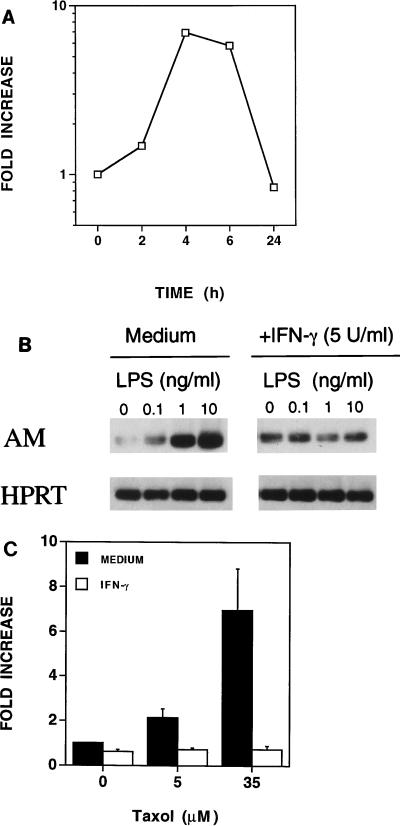

We next assessed the ability of a second potent macrophage-activating agent, IFN-γ, to regulate AM mRNA expression. C3H/OuJ peritoneal macrophages were treated with IFN-γ (5 U/ml) for 2, 4, 6, and 24 h. RNA was isolated, and AM and HPRT mRNAs were detected by RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 4A, AM mRNA expression was induced by IFN-γ as early as 2 h and peaked at 4 to 6 h (greater than sevenfold) and returned to basal levels by 24 h. In many instances, IFN-γ provides a “priming” signal that results in the synergistic induction of gene expression and secreted products (e.g., TNF-α, NȮ, IL-6) when provided with a second triggering signal such as LPS (13, 47). To ascertain whether IFN-γ would modulate the induction of AM by LPS, C3H/OuJ macrophages were cultured for 4 h with PW-LPS in the absence or presence of IFN-γ. As shown in Fig. 4B, IFN-γ (5 U/ml) down-regulated LPS-induced AM mRNA levels. Similar results were observed when the macrophages were stimulated simultaneously with both paclitaxel and IFN-γ (5 U/ml) (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Regulation of AM mRNA expression by IFN-γ in C3H/OuJ macrophages. (A) IFN-γ upregulates AM mRNA expression. C3H/OuJ macrophages were cultured for the indicated times with medium or 5-U/ml IFN-γ. These data were derived from a representative of two experiments. (B) IFN-γ down-regulates PW-LPS-induced AM mRNA expression. C3H/OuJ macrophages were cultured for 4 h in the presence of medium only or increasing concentrations of PW-LPS in the absence or presence of 5-U/ml IFN-γ. A representative of three Southern blots is shown. (C) IFN-γ down-regulates paclitaxel-induced AM mRNA expression. C3H/OuJ macrophages were cultured for 4 h in the presence of medium only, 5 μM paclitaxel, or 35 μM paclitaxel, in the absence or presence of 5-U/ml IFN-γ. These data represent the arithmetic mean ± the standard error of the mean of three separate experiments.

LPS-induced AM mRNA in vivo.

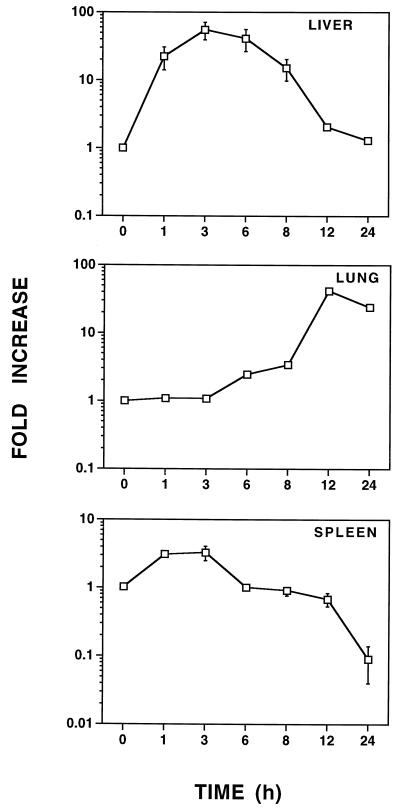

Previous studies in this laboratory have demonstrated that LPS elicits gene expression in vivo that is both organ and gene specific (39, 40). To assess whether LPS augments AM mRNA levels in vivo, C57BL/6 mice were challenged i.p. with 25 μg of LPS, and AM mRNA expression was assessed in the liver, lungs, and spleen. As shown in Fig. 5, AM mRNA expression was rapidly induced (by 1 h) in the liver. Hepatic AM mRNA remained at heightened levels (∼20- to 60-fold above the baseline) from 3 to 8 h after LPS challenge and then returned to nearly basal levels by 12 h. In contrast, increased AM mRNA expression was not observed in the lungs until 6 to 8 h after LPS challenge, and pulmonary AM mRNA peaked after 12 to 24 h (∼50-fold). In contrast to that in both the liver and the lungs, splenic AM mRNA expression was poorly modulated (∼4-fold in 3 h) by LPS, and by 24 h, splenic AM mRNA expression was substantially downregulated (∼10-fold below basal AM mRNA levels).

FIG. 5.

LPS augments AM mRNA expression in vivo. C57BL/6 mice were injected i.p. with 25 μg of LPS. These data are the mean fold increase in AM mRNA expression ± the standard error of the mean from four to eight individual mice at each time point. Means are expressed relative to that of the saline-injected control (t = 0), which was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1. When not visible, bars indicating the standard error of the mean are smaller than the symbol.

Endogenous IFN-γ regulates LPS-induced AM mRNA in vivo.

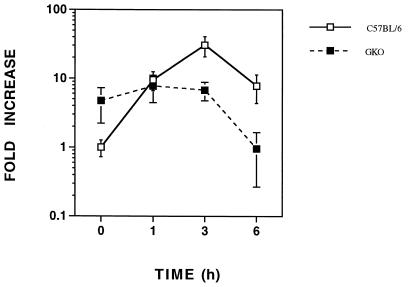

In vitro, IFN-γ suppressed LPS-induced AM mRNA in C3H/OuJ macrophages (Fig. 4B). To examine the role of IFN-γ in the in vivo regulation of AM mRNA by LPS, mice with a targeted disruption in the IFN-γ gene (GKO) (7) were utilized. The basal hepatic AM mRNA level was about fourfold higher in the livers of GKO mice than in those of C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 6). Interestingly, no increase in hepatic AM mRNA was observed after LPS challenge. In fact, by 6 h following LPS administration, AM mRNA levels had returned to the baseline levels exhibited by control C57BL/6 mice.

FIG. 6.

Endogenous IFN-γ regulates LPS-induced AM mRNA in vivo. GKO and C57BL/6 mice were injected i.p. with 25 μg of LPS, and LPS-induced AM mRNA was quantified in the liver. These data are the arithmetic mean ± the standard error of the mean for five to eight mice at each time point.

DISCUSSION

LPS, the endotoxic outer membrane component of gram-negative bacteria, has long been implicated in the pathophysiology of septic shock. The inflammatory syndrome that is associated with sepsis is characterized by hypotension and multiple organ dysfunction, which is felt to be initiated by the action of secondary inflammatory mediators released from LPS-stimulated cells. The systemic inflammatory response induced by LPS or gram-negative bacterial infection can be partially ameliorated by blocking either LPS itself or downstream endogenous mediators, such as IL-1 and TNF-α. Many of these mediators are produced by macrophages. However, in the clinical setting, blocking LPS itself is of limited value since the deleterious effects have already been initiated by the time the inflammatory syndrome is apparent (49). Based on preclinical data, the approach of blocking endogenous inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α, seemed promising; however, clinical trials have yet to demonstrate the efficacy of using this approach in septic shock (32). AM, originally identified in pheochromocytoma, is a ubiquitously expressed peptide that is a member of the calcitonin-related peptide superfamily (19). It possesses both potent vasodepressor (15, 19) and cardiodepressor (20, 38, 43) activities, and increased plasma AM levels have been reported in a variety of clinical conditions associated with blood pressure and hemodynamic alterations, suggesting that it participates in blood pressure regulation (14, 18). While LPS had been shown previously to induce AM gene transcription in endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells (41), it was not known whether LPS also induces AM in macrophages. The data presented herein demonstrate that LPS causes a rapid induction of AM gene transcription in peritoneal macrophages in vitro, peaking within 2 h and gradually subsiding within 24 h, a kinetic profile very similar to that of other LPS-inducible proinflammatory genes (21, 22, 35). Furthermore, AM gene induction is not dependent upon new protein synthesis, implying the existence of a preformed signal transduction apparatus. Moreover, the finding that CHX alone increased steady-state AM mRNA levels suggests that AM gene expression is maintained in a suppressed state due to the action of a CHX-sensitive suppression molecule. The increase in AM mRNA was followed by secretion of immunoreactive AM into the culture supernatants. Thus, our study lends support to the notion that AM, like TNF-α and IL-1, might serve as an endogenous mediator of the inflammatory syndrome associated with sepsis. This remains to be proven by blocking its action in vivo; however, blocking anti-AM antibodies are not available. More recently, AM has been shown to be directly microbicidal (46), suggesting that AM, like other cytokines and chemokines, can be stimulated by bacterial products, such as LPS, as a normal part of the macrophage’s innate response to infection. This hypothesis is strengthened by our findings that two other bacterial stimulants, STAg and endotoxin-associated proteins, were also found to be potent stimuli (Fig. 2).

It is also known that AM significantly enhanced NO· synthesis evoked by LPS and IFN-γ in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Thus, AM may contribute to circulatory failure during endotoxin shock, in part, by modulating NO· release (42). However, we were unable to activate C3H/OuJ macrophages with synthetic AM (up to 1 mM) to release NO·; and the presence of synthetic AM failed to modulate NO· release stimulated by LPS and/or IFN-γ (data not shown). Thus, it appears that the induction of each of these two vasodilatory substances by LPS is regulated independently.

We have previously shown that the antitumor chemotherapeutic agent paclitaxel mimics the effects of LPS on murine macrophages. Both are dependent upon the expression of a normal Lps allele, are blocked by the same LPS analog antagonists, cause tyrosine phosphorylation of MAPKs and autophosphorylation of Lyn kinase, induce translocation of NF-κB, and induce an indistinguishable pattern of cytokine gene expression and secretion (6, 25). Furthermore, the effect of paclitaxel appears to be independent of its well-characterized microtubule-binding activity, as evidenced by the failure of paclitaxel analogs with various microtubule-binding capacities to correlate with LPS-mimetic activity (17, 25, 45). The data presented herein demonstrate that, like LPS, AM is induced in murine macrophages by paclitaxel. Interestingly, paclitaxel causes hypotension in ∼10% of patients within 3 h of administration, and the mechanism of this side effect is unknown but the data are consistent with the possibility that paclitaxel-induced AM is a contributing endogenous mediator. AM has recently been shown to act as a local autocrine growth factor in a variety of human tumors (29). The antitumor activity of paclitaxel is believed to be due primarily to its antimitotic activity on tumor cells, although it has also been shown to activate tumoricidal macrophages (4, 24) and to inhibit angiogenesis. The role of paclitaxel-induced production of AM by neoplastic cells will be the focus of future studies.

In vivo, LPS induced an almost 100-fold increase in AM gene expression in the liver, reaching peak expression within a few hours, whereas later induction was observed in the lungs, with fundamentally no AM induction in the spleen. LPS has been shown to cause elevated AM levels in the plasma of rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells and in endothelial cell tissue from anesthetized rats (42), as well as to induce a two- to threefold increase in AM mRNA levels in a variety of organs, including the lungs and intestine (41). Plasma levels reflect local hemodynamic distribution, as well as production and secretion. Thus, studying protein levels may not be an accurate measure of secretion by a given organ. By studying the time course of gene induction directly, we could localize the liver as a major site of early AM production in response to LPS, with kinetics common to those of acute-phase reactants. The particular hepatic cell type (i.e., resident histiocytic Kupffer cells, hepatocytes, or others) that is responsible for this increase remains to be elucidated, as is the relative contribution of other parenchymal tissues not examined here.

The possible role of IFN-γ in the regulation of AM gene expression is another novel aspect of this study. IFN-γ alone is nearly as potent an inducer of AM gene expression as LPS in vitro, yet in contrast to many LPS-inducible genes, where IFN-γ and LPS synergize (e.g., those for TNF-α, inducible NO· synthase, etc.) (13, 47), AM gene expression was antagonized when both IFN-γ and LPS or paclitaxel were present simultaneously. This pattern of mitigated gene expression in the presence of both IFN-γ and LPS has been reported for several other LPS-inducible genes, including those for KC, IL-1β, the type 2 TNF receptor, and the secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (10, 16, 23). The molecular interaction that results in this antagonism is not understood. In vivo, IFN-γ has been implicated as a critical cytokine in LPS-induced toxicity (39). Mice with a targeted mutation of the IFN-γ gene (i.e., GKO mice) exhibited elevated basal AM expression that was down-regulated only after LPS injection. These data support the hypothesis that IFN-γ must necessarily interact with some additional LPS-inducible inflammatory mediator to maintain AM levels in the normal mouse.

Taken collectively, our data suggest that the gene for AM may be viewed as an additional immediate-early gene produced predominantly by the liver in response to LPS. The relative contribution of AM to hypotension and septic shock remains to be elucidated by blocking its secretion or action.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by USAMRDC DAMD17-96-1-6258 and NIH grant AI-18797.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

A very similar report has recently been published by A. Kubo, N. Mimamino, Y. Isumi, T. Katafuchi, K. Kangawa, K. Dohi, and H. Matsuo (J. Biol. Chem. 273:16730–16738, 1998).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham E, Wunderink R, Silverman H, Perl T M, Nasraway S, Levy H, Bone R, Wenzel R P, Balk R, Allred R. Efficacy and safety of monoclonal antibody to human tumor necrosis factor alpha in patients with sepsis syndrome. A randomized, controlled, double-blind, multicenter clinical trial. TNF-alpha MAb Sepsis Study Group. JAMA. 1995;273:934–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atwell G J, Rewcastle G W, Baguley B C, Denny W A. Potential antitumor agents. 60. Relationships between structure and in vivo colon 38 activity for 5-substituted 9-oxoxanthene-4-acetic acids. J Med Chem. 1990;33:1375–1379. doi: 10.1021/jm00167a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barber S A, Fultz M J, Salkowski C A, Vogel S N. Differential expression of interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1), IRF-2, and interferon consensus sequence binding protein genes in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-responsive and LPS-hyporesponsive macrophages. Infect Immun. 1995;63:601–608. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.601-608.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogdan C, Ding A. Taxol, a microtubule-stabilizing antineoplastic agent, induces expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1 in macrophages. J Leukocyte Biol. 1992;52:119–121. doi: 10.1002/jlb.52.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bone R C. A critical evaluation of new agents for the treatment of sepsis. JAMA. 1991;266:1686–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Courtois G, Whiteside S T, Sibley C H, Israel A. Characterization of a mutant cell line that does not activate NF-κB in response to multiple stimuli. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1441–1449. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalton D K, Pitts-Meek S, Keshav S, Figari I S, Bradley A, Stewart T A. Multiple defects of immune cell function in mice with disrupted interferon-gamma genes. Science. 1993;259:1739–1742. doi: 10.1126/science.8456300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding A H, Porteu F, Sanchez E, Nathan C F. Shared actions of endotoxin and taxol on TNF receptors and TNF release. Science. 1990;248:370–372. doi: 10.1126/science.1970196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fultz M J, Barber S A, Dieffenbach C W, Vogel S N. Induction of IFN-gamma in macrophages by lipopolysaccharide. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1383–1392. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.11.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton T A, Major J A. Oxidized LDL potentiates LPS-induced transcription of the chemokine KC gene. J Leukocyte Biol. 1996;59:940–947. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.6.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henricson B E, Carboni J M, Burkhardt A L, Vogel S N. LPS and Taxol activate Lyn kinase autophosphorylation in Lpsn, but not in Lpsd, macrophages. Mol Med. 1995;1:428–435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogan M M, Vogel S N. Lipid A-associated proteins provide an alternate “second signal” in the activation of recombinant interferon-gamma-primed, C3H/HeJ macrophages to a fully tumoricidal state. J Immunol. 1987;139:3697–3702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogan M M, Vogel S N. Production of tumor necrosis factor by rIFN-gamma-primed C3H/HeJ (Lpsd) macrophages requires the presence of lipid A-associated proteins. J Immunol. 1988;141:4196–4202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Research Council DHEW publication no. (NIH) 85-23. Washington, D.C: Institute of Laboratory Resources; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishimitsu T, Nishikimi T, Saito Y, Kitamura K, Eto T, Kangawa K, Matsuo H, Omae T, Matsuoka H. Plasma levels of adrenomedullin, a newly identified hypotensive peptide, in patients with hypertension and renal failure. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2158–2161. doi: 10.1172/JCI117573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishiyama Y, Kitamura K, Ichiki Y, Nakamura S, Kida O, Kangawa K, Eto T. Hemodynamic effects of a novel hypotensive peptide, human adrenomedullin, in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;241:271–273. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin F-Y, Nathan C, Radzioch D, Ding A. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor: a macrophage product induced by and antagonistic to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Cell. 1997;88:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81880-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirikae T, Ojima I, Kirikae F, Ma Z, Kuduk S D, Slater J C, Takeuchi C S, Bounaud P Y, Nakano M. Structural requirements of taxoids for nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor production by murine macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227:227–235. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitamura K, Ichiki Y, Tanaka M, Kawamoto M, Emura J, Sakakibara S, Kangawa K, Matsuo H, Eto T. Immunoreactive adrenomedullin in human plasma. FEBS Lett. 1994;341:288–290. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80474-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitamura K, Kangawa K, Kawamoto M, Ichiki Y, Nakamura S, Matsuo H, Eto T. Adrenomedullin: a novel hypotensive peptide isolated from human pheochromocytoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;192:553–560. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitamura K, Sakata J, Kangawa K, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Eto T. Cloning and characterization of cDNA encoding a precursor for human adrenomedullin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;194:720–725. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1881. . (Erratum, 202:643, 1994.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z Y, Manthey C L, Perera P Y, Sher A, Vogel S N. Toxoplasma gondii soluble antigen induces a subset of lipopolysaccharide-inducible genes and tyrosine phosphoproteins in peritoneal macrophages. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3434–3440. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3434-3440.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manthey C L, Brandes M E, Perera P Y, Vogel S N. Taxol increases steady-state levels of lipopolysaccharide-inducible genes and protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 1992;149:2459–2465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manthey C L, Perera P Y, Henricson B E, Hamilton T A, Qureshi N, Vogel S N. Endotoxin-induced early gene expression in C3H/HeJ (Lpsd) macrophages. J Immunol. 1994;153:2653–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manthey C L, Perera P Y, Salkowski C A, Vogel S N. Taxol provides a second signal for murine macrophage tumoricidal activity. J Immunol. 1994;152:825–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manthey C L, Vogel S N. The role of cytokines in host responses to endotoxin. Rev Med Microbiol. 1992;3:72–79. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez A, Elsasser T H, Muro-Cacho C, Moody T W, Miller M J, Macri C J, Cuttitta F. Expression of adrenomedullin and its receptor in normal and malignant human skin: a potential pluripotent role in the integument. Endocrinology. 1997;138:5597–5604. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.12.5622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez A, Miller M J, Unsworth E J, Siegfried J M, Cuttitta F. Expression of adrenomedullin in normal human lung and in pulmonary tumors. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4099–4105. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.9.7649118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McIntire F C, Sievert H W, Barlow G H, Finley R A, Lee A Y. Chemical, physical, biological properties of a lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli K-235. Biochemistry. 1967;6:2363–2372. doi: 10.1021/bi00860a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller M J, Martinez A, Unsworth E J, Thiele C J, Moody T W, Elsasser T, Cuttitta F. Adrenomedullin expression in human tumor cell lines. Its potential role as an autocrine growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23345–23351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minnard E A, Shou J, Naama H, Cech A, Gallagher H, Daly J M. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis is detrimental during endotoxemia. Arch Surg. 1994;129:142–147. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420260038004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrison D C, Leive L. Fractions of lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli O111:B4 prepared by two extraction procedures. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:2911–2919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohlsson K, Bjork P, Bergenfeldt M, Hageman R, Thompson R C. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist reduces mortality from endotoxin shock. Nature. 1990;348:550–552. doi: 10.1038/348550a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker M M, Shelhamer J H, Natanson C, Alling D W, Parrillo J E. Serial cardiovascular variables in survivors and nonsurvivors of human septic shock: heart rate as an early predictor of prognosis. Crit Care Med. 1987;15:923–929. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198710000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parrillo J E. Pathogenetic mechanisms of septic shock. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1471–1477. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perera P-Y, Barber S A, Ching L M, Vogel S N. Activation of LPS-inducible genes by the antitumor agent 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid in primary murine macrophages. Dissection of signaling pathways leading to gene induction and tyrosine phosphorylation. J Immunol. 1994;153:4684–4693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perera P-Y, Qureshi N, Vogel S N. Paclitaxel (Taxol)-induced NF-κB translocation in murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1996;64:878–884. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.878-884.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rewcastle G W, Atwell G J, Baguley B C, Calveley S B, Denny W A. Potential antitumor agents. 58. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of substituted xanthenone-4-acetic acids active against the colon 38 tumor in vivo. J Med Chem. 1989;32:793–799. doi: 10.1021/jm00124a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakata J, Shimokubo T, Kitamura K, Nakamura S, Kangawa K, Matsuo H, Eto T. Molecular cloning and biological activities of rat adrenomedullin, a hypotensive peptide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;195:921–927. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salkowski C A, Detore G, McNally R, van Rooijen N, Vogel S N. Regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase messenger RNA expression and nitric oxide production by lipopolysaccharide in vivo: the roles of macrophages, endogenous IFN-gamma, and TNF receptor-1-mediated signaling. J Immunol. 1997;158:905–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salkowski C A, Neta R, Wynn T A, Strassmann G, van Rooijen N, Vogel S N. Effect of liposome-mediated macrophage depletion on LPS-induced cytokine gene expression and radioprotection. J Immunol. 1995;155:3168–3179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shoji H, Minamino N, Kangawa K, Matsuo H. Endotoxin markedly elevates plasma concentration and gene transcription of adrenomedullin in rat. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;215:531–537. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.So S, Hattori Y, Kasai K, Shimoda S, Gross S S. Up-regulation of rat adrenomedullin gene expression by endotoxin: relation to nitric oxide synthesis. Life Sci. 1996;58:L309–L315. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugo S, Minamino N, Kangawa K, Miyamoto K, Kitamura K, Sakata J, Eto T, Matsuo H. Endothelial cells actively synthesize and secrete adrenomedullin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:1160–1166. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1827. . (Erratum, 203:1363, 1994.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugo S, Minamino N, Shoji H, Kangawa K, Kitamura K, Eto T, Matsuo H. Interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor and lipopolysaccharide additively stimulate production of adrenomedullin in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;207:25–32. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vogel S N. The Lps gene: insights into the genetic and molecular basis of LPS responsiveness and macrophage differentiation. In: Beutler B, editor. Tumor necrosis factors: the molecules and their emerging role in medicine. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1992. pp. 485–513. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walsh, T. J., A. Martinez, J. Peter, M. J. Miller, C. A. Lyman, J.-A. Bengoechea, T. Jacks, A. De Lucca, M. Rudel, T. H. Elsasser, E. J. Unsworth, and F. Cuttitta. Antimicrobial activities of adrenomedullin and its gene-related peptides. J. Biol. Chem., in press.

- 47.Zhang X, Laubach V E, Alley E W, Edwards K A, Sherman P A, Russell S W, Murphy W J. Transcriptional basis for hyporesponsiveness of the human inducible nitric oxide synthase gene to lipopolysaccharide/interferon-gamma. J Leukocyte Biol. 1996;59:575–585. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao Y, Hague S, Manek S, Zhang L, Bicknell R, Rees M C. PCR display identifies tamoxifen induction of the novel angiogenic factor adrenomedullin by a nonestrogenic mechanism in the human endometrium. Oncogene. 1998;16:409–415. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ziegler E J, Fisher C J J, Sprung C L, Straube R C, Sadoff J C, Foulke G E, Wortel C H, Fink M P, Dellinger R P, Teng N N. Treatment of gram-negative bacteremia and septic shock with HA-1A human monoclonal antibody against endotoxin. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The HA-1A Sepsis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:429–436. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102143240701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]