Abstract

The interactions of Nocardia asteroides GUH-2 with pulmonary epithelial cells of C57BL/6 mice and with HeLa cells were studied. Electron microscopy demonstrated that only the tips of log-phase cells penetrated pulmonary epithelial cells following intranasal administration, and nocardiae were recovered from the brain. Coccobacillary cells neither invaded nor disseminated. Serum from immunized mice (IMS) decreased attachment to and penetration of pulmonary epithelial cell surfaces by log-phase GUH-2 and inhibited spread to the brain. IMS was adsorbed against stationary-phase cells. Western immunoblots suggested that this adsorbed IMS was reactive primarily with 43- and 62-kDa proteins. Immunofluorescence showed that adsorbed IMS preferentially labeled the tips of log-phase GUH-2 cells. Since this IMS was reactive to culture filtrate antigens, several of these proteins were cut from gels, and mice were immunized. Sera against 62-, 55-, 43-, 36-, 31-, and 25-kDa antigens were obtained. The antisera against the 43- and 36-kDa proteins labeled the filament tips of GUH-2 cells. Only the antiserum against the 43-kDa antigen increased pulmonary clearance, inhibited apical attachment to and penetration of pulmonary epithelial cells, and prevented spread to the brain. An in vitro model with HeLa cells demonstrated that the tips of log-phase cells of GUH-2 adhered to and penetrated the surface of HeLa cells. Invasion assays with amikacin treatment demonstrated that nocardiae were internalized. Adsorbed IMS blocked attachment to and invasion of these cells. These data suggested that a filament tip-associated 43-kDa protein was involved in attachment to and invasion of pulmonary epithelial cells and HeLa cells by N. asteroides GUH-2.

Nocardia asteroides and related species are emerging as important primary and opportunistic pathogens in humans (11, 31, 42) and other animals (12, 28). Nocardiae are facultative intracellular pathogens capable of resisting the microbicidal activities of polymorphonuclear neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages (5, 18, 22, 26). In humans, the most frequent site for infection by members of the N. asteroides complex is the lung, which is often followed by dissemination to the brain (6, 30, 32, 36). The mechanisms whereby these nocardiae invade the lung and disseminate to the brain are not known.

Unlike most bacteria, all species of Nocardia grow by apical extension to form filaments (often with lateral branches) that divide into coccoid cells by fragmentation (6, 11). During the logarithmic phase of growth of N. asteroides in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth, more than 99% of the bacteria appear as filamentous cells (8). In contrast, during the stationary phase of the same culture, more than 99% of the nocardial cells appear as cocci, short rods, and coccobacilli (8). Morphologically homogeneous cell suspensions with few cellular aggregates can be prepared from these cultures at different stages of growth by differential centrifugation (8). Numerous studies have shown significant differences in the ultrastructural and biochemical compositions of the cell envelopes of log-phase nocardiae as compared to stationary-phase cells. Furthermore, these structural differences between log- and stationary-phase organisms appear to correspond with major alterations in host-pathogen interactions both in vitro and in vivo (5, 8, 9). Understanding the mechanisms for these interactions is a major focus for our research.

Certain strains of N. asteroides, in log phase, actively invade through capillary endothelial cells in specific regions of the murine brain (4, 10). In contrast, other strains of N. asteroides penetrate pulmonary epithelial cells but not endothelial cells in the brain (4). Log-phase cells of the model neuroinvasive strain N. asteroides GUH-2 invade both pulmonary epithelial cells and capillary endothelial cells. This organism also penetrates the surface of and becomes internalized in primary cultures of neonatal murine type II but not type I astroglia cells (14), the artery endothelial cell line CPAE, and human astrocytoma cell lines (15). Pretreatment with a microfilament inhibitor, cytochalasin, significantly reduces internalization of the nocardiae in some, but not all, cell lines. The microtubule inhibitor colchicine has little effect in any cell lines except the macrophage cell lines ATCC J-774 and P388D1 (15).

Log-phase and stationary-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2 bind longitudinally to the surfaces of host cells (14, 15), and both are readily internalized by phagocytic cells. However, only filamentous cells of GUH-2 attach by way of the tip, resulting in penetration and invasion of nonphagocytic cells (4, 10, 14, 15). All of these observations suggest multiple mechanisms for nocardial adherence to and internalization in host cells.

The purpose of this investigation was to determine whether specific proteins associated with the growing tips of log-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2 facilitated attachment to, penetration of, and invasion of pulmonary epithelial cells with spread to the brain. Preliminary observations suggested that spread of log-phase GUH-2 to the brain occurred more frequently in C57BL/6 mice than in BALB/c mice following intranasal (i.n.) administration (unpublished data). Therefore, our in vivo studies utilized C57BL/6 mice to investigate these nocardial properties. HeLa cells have been used extensively as a model for investigating mechanisms of invasion by a variety of pathogens (1, 35, 39, 40). Therefore, this epithelial cell-derived cell line was selected to study further the mechanisms of nocardial attachment and invasion in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms.

N. asteroides GUH-2 was isolated from a fatal human infection. It is highly virulent for animals and invasive for tissue culture cells. N. asteroides GUH-2 has been studied extensively as a model for nocardial pathogenesis (6). N. asteroides ATCC 19247 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.). This strain was originally isolated from the soil, and it has been designated the working type reference strain for the N. asteroides taxon (sensu stricto) (2). Strain 19247 shares many morphologic, structural, physiologic, and biochemical features with GUH-2, yet it is nonpathogenic for mice and does not invade cells (4, 14, 15). This strain has been utilized extensively as a negative control for studies on mechanisms of nocardial virulence (4, 19). The organisms were grown in BHI broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C on a rotary shaker. At specific stages of growth, standardized suspensions of single cells were prepared by differential centrifugation as previously reported (8, 9).

Antibodies specific for nocardial components.

Female specific-pathogen-free BALB/c mice (18 to 20 g) (Simonsen, Gilroy, Calif.) were sublethally infected with log-phase GUH-2 (105 CFU). After 1 month, they were boosted by an intraperitoneal injection with approximately 1 mg (wet weight) of formalin-killed log-phase cells in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2). Two weeks after the booster injection, the mice were sacrificed by ether overdose; the blood was removed, pooled (five mice per preparation), and allowed to clot, and the serum was collected. The antibody titer and specificity were measured by serologic analysis as described previously (29). This pooled serum was designated nonadsorbed immune mouse serum (IMS). Not all preparations of IMS were equally effective at blocking the interactions of log-phase GUH-2 with host cells. The IMS used in these studies was prepared against live log-phase GUH-2, and it was shown to have good blocking activity. To remove antibodies to surface epitopes shared by both log- and stationary-phase cells of GUH-2, portions of this IMS were adsorbed several times (up to 11 times for 30 min each at 37 and 4°C overnight) with whole stationary-phase cells (both live and formalin killed, with a cell mass equivalent to 108 CFU/ml). This adsorption process was continued until the IMS at a 1:2 dilution did not bind to stationary-phase nocardiae as detected by immunofluorescence analysis (see Fig. 1H). This serum was designated adsorbed IMS (ADS-IMS).

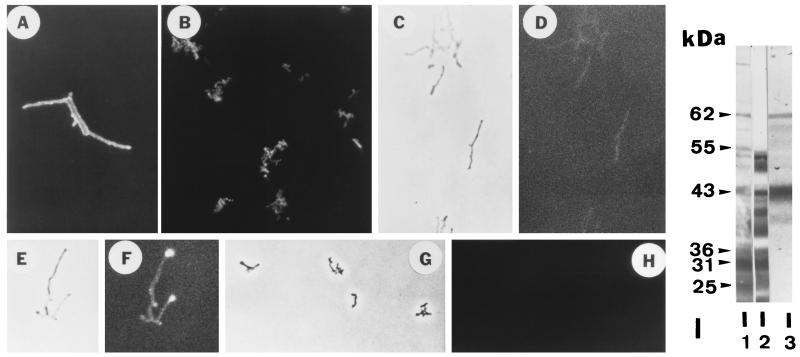

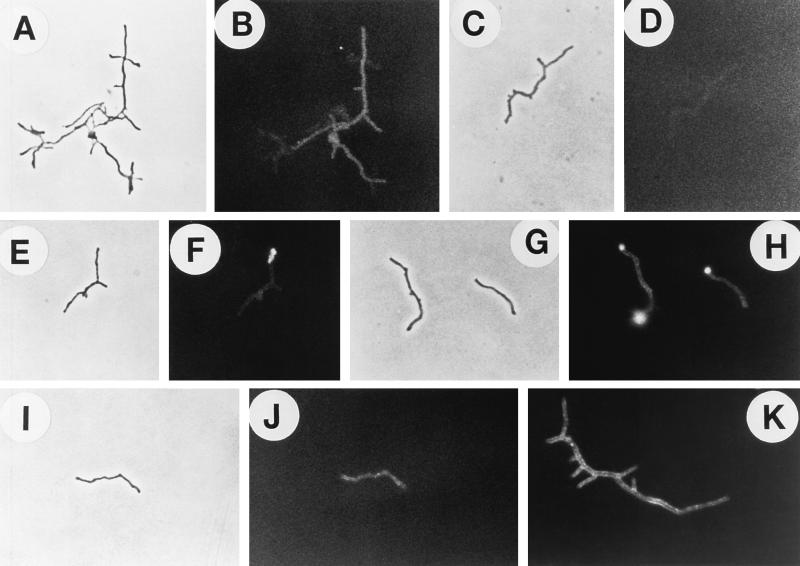

FIG. 1.

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy of N. asteroides GUH-2 treated with various murine antisera and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat antimouse immunoglobulin. Fluorescence was visualized by using epifluorescence illumination on a Ziess research microscope. (A) Log-phase (16-h) GUH-2 incubated with IMS. (B) Stationary-phase (120-h) GUH-2 incubated with IMS. (C) Phase-contrast micrograph of log-phase GUH-2 treated with NMS. (D) Immunofluorescence of the same bacteria shown in panel C. There was no specific reactivity (negative control), but slight autofluorescence was evident. (E) Phase-contrast micrograph of log-phase GUH-2 treated with ADS-IMS. (F) Immunofluorescence of the same bacterium shown in panel E. Note strong specific fluorescence localized at the filament tips. (G) Phase-contrast micrograph of stationary-phase GUH-2 treated with ADS-IMS. (H) Immunofluorescence of the same bacteria shown in panel G. Note the total absence of fluorescence. (I) Western immunoblot against SDS-soluble proteins of log-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2. Lane 1, culture filtrate antigens incubated with IMS; lane 2, SDS-solubilized cell walls incubated with IMS; lane 3, SDS-extracted proteins from live, log-phase GUH-2 incubated with ADS-IMS. Molecular mass markers are located relative to the migration of specific protein standards of known molecular mass.

To prepare antisera against specific culture filtrate antigens, N. asteroides GUH-2 was grown for 72 h at 37°C in defined mineral salts broth with 0.5% (wt/vol) glutamate as the carbon source. The proteins secreted into the medium were concentrated as previously described (29), and the final concentration of the culture filtrate proteins was adjusted to 3 mg/ml. Three milligrams of culture filtrate proteins was separated by preparative sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (12% polyacrylamide) (Bio-Rad Protean II Slab Cell); parallel portions of the gel were stained with Coomassie blue to localize proteins. The bands at 62, 55, 43, 36, 31, and 25 kDa were excised. These proteins were collected (electroeluted), and BALB/c mice were immunized. One week after the final booster, sera were collected. The specificities and reactivities were determined (29).

Immunofluorescence analysis.

Suspensions of single cells of N. asteroides GUH-2 and ATCC 19247 during the log and stationary phases of growth were prepared by differential centrifugation as described previously (9). The cells were washed three times with PBS (pH 7.2) and incubated with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) at 37°C for 30 min to block nonspecific binding of immunoglobulin G. The cells were then washed with PBS and incubated for 30 min at 37°C with twofold serial dilutions of either normal mouse serum (NMS), IMS, ADS-IMS, or anti-62-kDa, anti-55-kDa, anti-43-kDa, anti-36-kDa, anti-31-kDa, or anti-25-kDa antiserum as described above. Next, these cells were washed three or four times with PBS and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin for 30 min at 37°C. The labeled cells were washed three times in PBS and pelleted, and wet mounts were prepared on glass slides. The samples were observed with a Zeiss research microscope equipped with a mercury vapor epifluorescence illuminator and filters for fluorescein isothiocyanate. Photographs were made with a Nikon F4 camera and either Ectachrome 400 or 200 slide film (Kodak) (13).

Pulmonary interactions in mice.

Normal, pathogen-free C57BL/6 mice (from either Charles River or Jackson Laboratory; 5 to 10 mice/group) were infected i.n. with either late-stationary-phase (120-h) or log-phase (16-h) cells of N. asteroides GUH-2. The log-phase cells were incubated first with FCS, used as a blocking agent, and then with either NMS, adsorbed immune mouse serum ADS-IMS, or murine serum prepared against the 62-, 55-, 43-, or 36-kDa protein cut from gels as described by Kjelstrom and Beaman (29). Briefly, the bacteria were grown to mid-log phase (16 h). Suspensions of single cells were prepared by differential centrifugation and incubated for 30 min in 10% FCS. These samples were then washed in PBS-Tween (PBST). Aliquots containing 0.5 ml were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with either NMS, ADS-IMS, or anti-62-kDa, anti-55-kDa, anti-43-kDa, or anti-36-kDa antiserum. The final dilution for all sera was 1:10. The bacterial concentration was adjusted to an absorbance of 0.5 with a Beckman spectrometer at a wavelength of 580 nm. Samples were diluted and plated on tryptic soy agar (TSA) to determine CFU per sample. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (50 mg/kg of body weight), and 0.05 ml of the bacterial suspension in tissue culture medium containing sera (as described above) was placed onto the anterior nares. This suspension was aspirated into the lungs. Previous studies showed that these methods resulted in a reproducible delivery of bacteria into the lungs (4, 7). The mice were sacrificed by diethyl ether overdose. The thorax was opened, and the left lobe of the lung was exposed. The bronchus leading into this lobe was clamped with a hemostat, and then the right and left lobes from the same animal were separated. The left lobe was removed, placed in sterile water, and homogenized. The numbers of viable bacteria were determined by plating dilutions of the homogenate on BHI agar. The right lobes were perfused with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer and prepared for light and electron microscopy (4, 7).

Tissue culture.

The cell line HeLa CCL-2 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 10% calf serum. They were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cell monolayers were detached from tissue culture plates with fresh trypsin (0.25%) and centrifuged at 500 × g. This cell pellet was suspended in fresh medium. Aliquots containing 105 cells per 0.2 ml of medium were added to Lab-Tek eight-chamber slides (Miles Laboratories, Inc., Naperville, Ill.) and incubated for 24 h prior to infection with nocardiae.

Infection schedules for HeLa cells.

Suspensions of either coccobacillary cells from an early-stationary-phase culture (48 h) or filamentous cells from a log-phase culture (16 h) were prepared by differential centrifugation as described above. The bacterial cells were incubated for 30 min in 10% FCS (as a blocking step) and washed in PBS-Tween. They were then incubated for 30 min with either NMS, IMS, or ADS-IMS as described above. The density of the cell suspension was determined, and 0.5 ml was added to each well of an eight-well slide chamber containing approximately 105 HeLa cells/chamber (multiplicity of infection ≃ 10:1). These were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The bacterial suspensions were removed and washed twice with 1 ml of fresh Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS). Duplicate wells of each sample were prepared for scanning and transmission electron microscopy, viability determination (cell-associated CFU), and enumeration of intracellular organisms (CFU/sample after amikacin treatment). Scanning electron microscopy was used to visualize and quantitate penetration of HeLa cells by nocardiae in each of these preparations (14, 15).

Quantitative scanning electron microscopy.

HeLa cell cultures were grown in Lab-Tek chambered slides for 24 h at 37°C as described above. Suspensions of cells of either N. asteroides GUH-2 or N. asteroides ATCC 19247 at different stages of growth were preincubated with either FCS, NMS, IMS, or ADS-IMS (described above). These were added to the HeLa cells, and after 1 h, the samples were washed with HBSS to remove nonadherent bacteria. Each slide chamber was filled with chilled 2.5% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) and left overnight at 4°C. The samples were washed with fresh cacodylate buffer, and each chamber was cut out of the slide and dehydrated through a series of solutions of ethanol in buffer (from 25 to 100% absolute ethanol). They were then critical point dried with CO2, coated with gold, and examined with a Philips scanning electron microscope at 15 kV as described previously (4). Random, representative areas of each slide chamber were examined, and the number of HeLa cells per field was counted. The number of bacteria that were adherent to the background and the number of bacteria attached to HeLa cells were scored. The number of cellular tips per bacterial cell, the number of tips attached to the HeLa cell surface, and the number of bacterial cells showing evidence of penetration of the HeLa cell surface were then determined. By counting several hundred HeLa cells per sample, we determined the relative effects that different antibodies had on adherence to and penetration of these cells. We evaluated different strains of nocardiae during different stages of growth. Each experiment was repeated so that all values were presented as the means of at least three determinations.

Transmission electron microscopy.

The samples were fixed with chilled 2.5% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) overnight. They were washed in fresh buffer containing 1% (wt/vol) sucrose and postfixed for 1 h with 1% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer. The cells were scraped from the slides, treated with 0.5% uranyl acetate for 30 min, and dehydrated through an ethanol series to 100% propylene oxide. They were then embedded in Med-cast epoxy resin (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, Calif.). Gold to silver sections were cut and placed on copper grids. These sections were stained for 30 min with 0.5% uranyl acetate in 50% methanol-water, washed, and stained for 5 min in 0.1% lead citrate. The sections were photographed with a Philips 400 electron microscope operated at 80 kV as previously described (15).

Western blotting.

The bacteria were washed with PBS. The proteins were solubilized from whole, live organisms by boiling log-phase cells for 1 h in 1 ml of sample buffer. This buffer contained 10 ml of glycerol, 20 ml of 10% SDS, 5 ml of mercaptoethanol, 52.5 ml of water, 12.5 ml of 0.5 M Tris HCl at pH 6.8, and 0.05% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue (13). The rationale was that this treatment would remove surface proteins more readily than intracellular proteins. Four hundred microliters of this preparation, containing approximately 2 mg of protein/ml, was layered on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. The sample was electrophoresed (PAGE) and transferred for Western blot immunoanalysis as described previously (29). In separate studies, log-phase cells of GUH-2 were broken open mechanically with a Braun disintegrator and glass beads (0.1 μm-diameter; Glasperlen). The crude homogenate was centrifuged, and the cell wall fraction was collected as described previously by Beaman and Moring (9). A cell wall pellet was boiled in sample buffer with SDS as described above, and approximately 3 mg of protein/ml was layered onto a 10% polyacrylamide gel. This preparation was electrophoresed (PAGE) and transferred for Western blotting. The culture filtrate antigens were prepared from GUH-2 as described by Kjelstrom and Beaman (29). Three milligrams of protein/ml in SDS buffer was layered onto polyacrylamide gels (29), and blots were made.

Amikacin killing assays to determine intracellular localization.

Suspensions (1 ml) of log-phase cells (108 CFU/ml) of either N. asteroides GUH-2 or ATCC 19247 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 10% calf serum were added to Lab-Tek eight-chamber slides (Miles Laboratories, Inc.) without HeLa cells for 2 h. The medium was removed, and the plates were gently rinsed once with HBSS. Two milliliters of 0.1% Triton X was added to triplicate wells and left for 15 min, and the wells were scraped rigorously with a sterile, tapered applicator. Dilutions were plated in TSA. This showed that approximately 0.0025% of the cells of GUH-2 and 0.0015% of the cells of ATCC 19257 in the inoculum adhered to the Lab-Tek tissue culture slides. The susceptibilities of N. asteroides GUH-2 and ATCC 19247 to amikacin, which acts only on extracellular organisms, were determined (17). The same procedures outlined above were repeated except that prior to removal of the bacteria, dilutions of amikacin sulfate (Fort Dodge Lab Inc., Fort Dodge, Iowa) of 1 to 100 μg/ml were added to triplicate wells. These wells were incubated for 30, 60, and 120 min at 37°C. The antibiotic was removed, and the wells were washed once with HBSS. Then, 1 ml of 0.1% Triton X was added and left for 15 min, the wells were scraped, and cells were plated directly into TSA for viability determination. Plate counts showed that 100% of both GUH-2 and ATCC 19247 cells adherent to the plastic wells were killed by 100 μg of amikacin in 60 min. Next, monolayers of HeLa cells in Lab-Tek eight-chamber slides were incubated with approximately 107 CFU of log-phase cells of either N. asteroides GUH-2 or N. asteroides ATCC 19247 that had been previously incubated with either FCS, NMS, IMS, or ADS-IMS (as described above) for 2.5 h. They were then washed three times with fresh medium and incubated 30 min longer. The medium was replaced with either medium alone or medium containing 100 μg of amikacin per ml, and the samples were incubated for an additional 60 min. The antibiotic was removed, and the wells were washed three times with HBSS. They were treated with 0.1% Triton X and scraped with a sterile applicator, and dilutions were made in sterile distilled water. These were plated in TSA. All determinations were done in triplicate, and each experiment was repeated.

RESULTS

Antigenic differences between log- and stationary-phase nocardiae.

Mice were immunized with live, log-phase cells of GUH-2, and indirect immunofluorescence labeling was utilized to determine immunoreactivity (Fig. 1A and B). The sera from these mice were adsorbed several times with whole, live, stationary-phase cells to remove shared surface antigens. This ADS-IMS was then incubated with log-phase, filamentous cells prepared from the same culture. Immunofluorescence demonstrated that primarily the tips of the log-phase filamentous cells of GUH-2 exhibited bright fluorescence (Fig. 1F). Log-phase filaments (Fig. 1A) and stationary-phase coccobacilli (Fig. 1B) of GUH-2 were uniformly outlined by bright fluorescence when treated with the nonadsorbed IMS. Stationary-phase cells of GUH-2 were not visible with the ADS-IMS (Fig. 1H). The noninvasive N. asteroides ATCC 19247 showed minimal fluorescence with ADS-IMS, and the filament tips of 19247 were not preferentially labeled (data not shown). These data demonstrated that the filament apex of growing cells of the invasive N. asteroides GUH-2 possessed surface antigens that were not detectable on either stationary-phase organisms or the filament tips of noninvasive nocardiae (Fig. 1A to H).

Immunodominant proteins on the surface of log-phase cells.

Protein antigens that were dominant on the surface of log-phase but not stationary-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2 were determined. As reported previously (21), the IMS against log-phase GUH-2 was reactive with numerous culture filtrate antigens in Western immunoblot transfers (Fig. 1I, lane 1). However, SDS extracts from cell wall preparations of log-phase GUH-2 revealed a different protein pattern (Fig. 1I, lane 2). The ADS-IMS described above had significantly enhanced immunoreactivity for two dominant protein bands at 43 and 62 kDa (Fig. 1I, lane 3). The relative intensity of this adsorbed serum appeared to be decreased for all of the other protein bands compared to the 43-kDa protein.

Since this IMS was reactive for several culture filtrate antigens from GUH-2 (Fig. 1I, lane 1), these antigens (62, 55, 43, 36, 31, and 25 kDa) were used to immunize mice. The reactivities of the sera obtained were confirmed by Western blot analysis.

Since extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins serve as ligands for adherence to and invasion of epithelial cells by many pathogens (21, 33, 37, 38, 41), laminin, fibronectin, and type IV collagen were incubated with the Western blot transfers of the log-phase protein extracts as described above to determine whether any of them bound to ECM proteins. There were two reactive bands at approximately 36 to 31 kDa which bound laminin (data not shown). However, none of the ECM proteins tested reacted with either the 62-kDa protein or the 43-kDa protein.

Association of FTAAs of GUH-2 with pulmonary adherence and invasion.

Log-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2 incubated with either NMS or ADS-IMS was instilled i.n. into the lungs of C57BL/6 mice. At the same time, these bacteria were monitored by immunofluorescence to confirm that apical labeling occurred following treatment with ADS-IMS (Fig. 1F). After 6 h, nocardial filament tip-associated attachment to and penetration of pulmonary epithelial cells were determined by scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 2). The nocardial filaments treated with NMS adhered to and penetrated into Clara cells and other nonciliated epithelial cells within the bronchioles and alveoli (Fig. 2A and B). At 6 h there appeared to be minimal host responsiveness to these bacteria in the bronchioles, even though a polymorphonuclear leukocyte response was observed in some of the alveoli (data not shown). In contrast, nocardiae treated with ADS-IMS had greater association with ciliated epithelial cells and induced abundant mucus that embedded the nocardiae onto the mucociliary surface of the bronchioles (Fig. 2C). There was little evidence for tip-associated adherence to and penetration of the epithelial surfaces in the alveoli by ADS-IMS-treated nocardiae (Fig. 2C and D). Nevertheless, occasional bacterial filaments treated with ADS-IMS still showed some longitudinal association with the epithelial surface (Fig. 2D). The number of CFU recovered from the lungs 6 h after i.n. administration indicated enhanced clearance of GUH-2 treated with ADS-IMS compared to NMS-treated controls (Fig. 3). Most of this loss of nocardial CFU from the lungs of mice inoculated with GUH-2 treated with ADS-IMS was probably due to physical removal of the bacteria by mucociliary action. These data suggested that filament tip-associated antigens (FTAAs), especially 43- and 62-kDa proteins, of N. asteroides GUH-2 were involved in epithelial cell adherence and invasion.

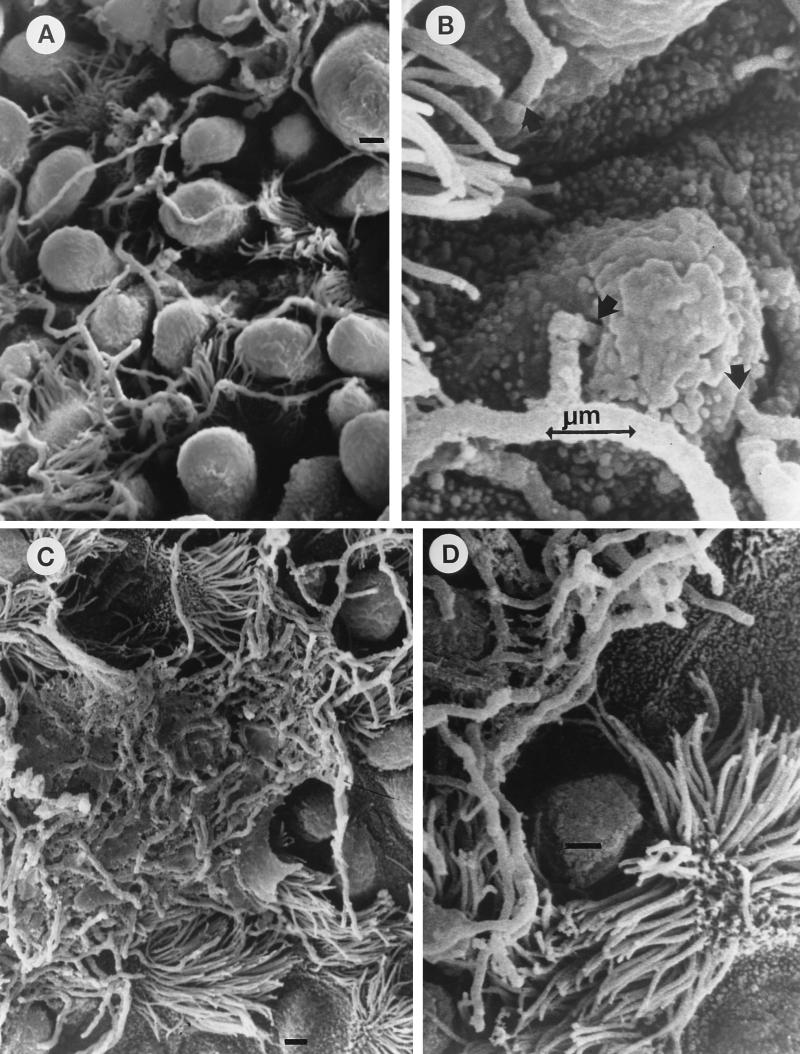

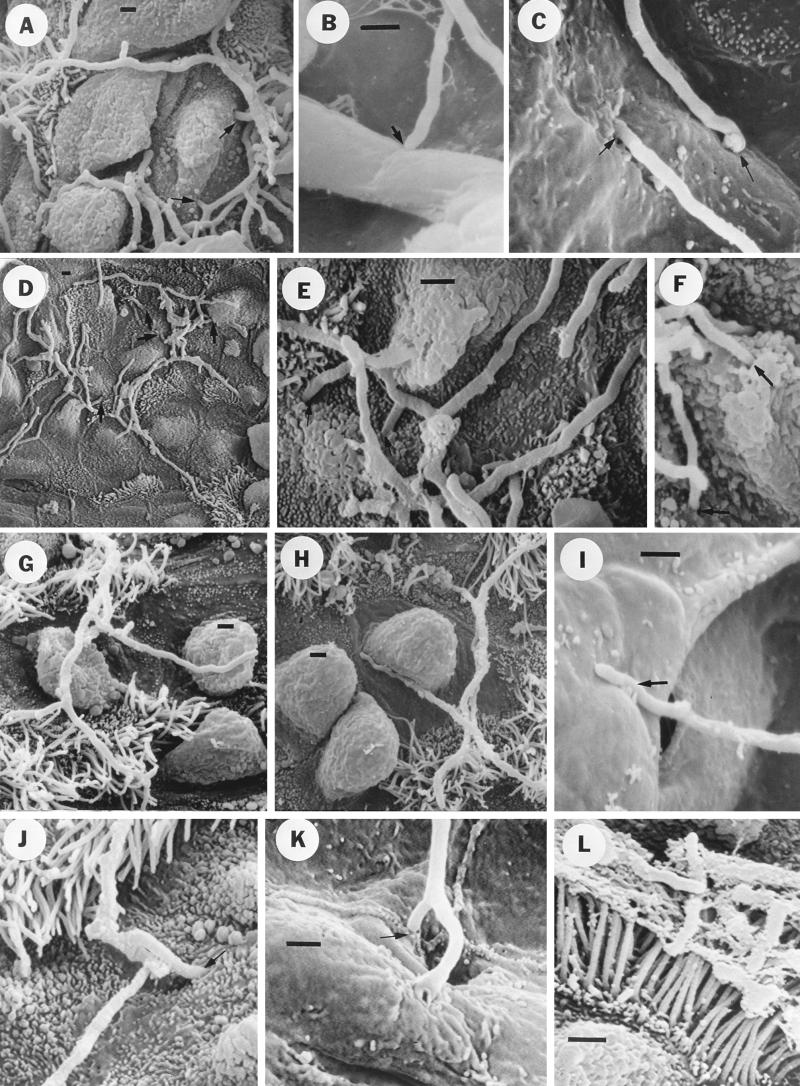

FIG. 2.

Scanning electron micrographs showing the effect of ADS-IMS on the invasion of nonciliated bronchiolar epithelial cells by log-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2 in C57BL/6 mice. Bars, 1 μm. (A) Low-magnification view showing nocardial filaments among the Clara cells and not specifically associated with ciliated cells (compare to panel C). Treatment was with NMS. (B) High-magnification view of an region adjacent to that in panel A, showing nocardial filaments penetrating into epithelial cells (arrows). Treatment was with NMS. (C) Low-magnification view showing nocardial filaments highly associated with ciliated cells on the bronchiolar surface (treatment was with ADS-IMS). Note that most of the filaments appear to be embedded in a material that may be mucus lying on the surface, whereas masses of nocardial filaments embedded in this mucous material were not observed in the lungs of NMS-treated controls (compare panels A and C). (D) High-magnification view showing nocardial filaments on the bronchiolar surface and associated with ciliated cells. Note that freely associated filaments appear to be only longitudinally adherent to the surface, and filament tips did not appear to be either adhering to or penetrating epithelial cells. Treatment was with ADS-IMS.

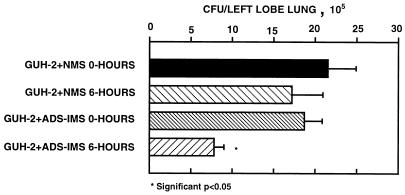

FIG. 3.

Pulmonary clearance of log-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2 following incubation with ADS-IMS, showing the effect of ADS-IMS 6 h after i.n. administration to C57BL/6 mice. Error bars represent standard errors (n = 5).

FTAAs of log-phase GUH-2.

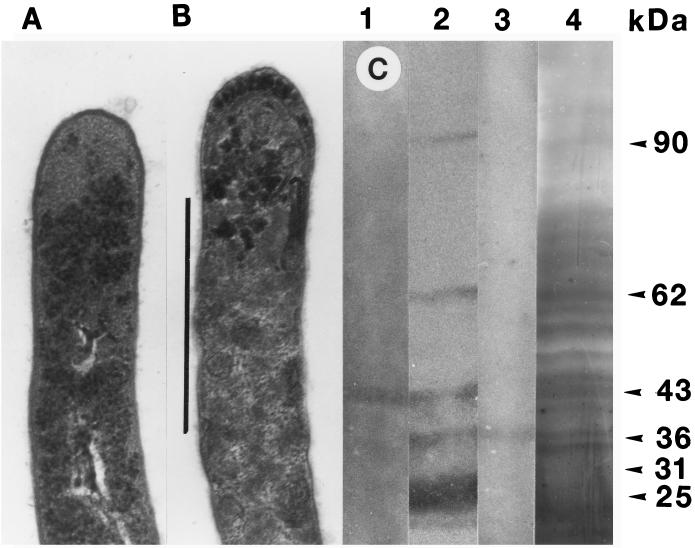

As described above, antibody to a 43-kDa protein was dominantly present in ADS-IMS which bound to the filament tips of log-phase N. asteroides GUH-2 cells (Fig. 1I, lane 3). The antigens used for these studies were prepared by boiling log-phase GUH-2 in 1% SDS for 1 h. The rationale was that this treatment would remove surface proteins more readily than intracellular proteins. To test this hypothesis, the SDS-extracted cells and the untreated cells were analyzed by electron microscopy (Fig. 4A and B). This SDS extraction did not lyse the bacteria; however, SDS significantly altered the surface of the nocardiae (Fig. 4B). Its effects were most pronounced at the filament tip (compare Fig. 4A and B). Silver staining after PAGE of the SDS-extracted material revealed numerous components, including 62-, 43-, and 36-kDa bands (Fig. 4C, lane 4). The locations of these bands were confirmed by Western blotting with IMS (Fig. 4C, lane 2) and with monospecific antisera against 43- and 36-kDa culture filtrate antigens (Fig. 4C, lanes 1 and 3, respectively).

FIG. 4.

Effect of SDS extraction on log-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2. (A) Electron microscopy of the tip of a log-phase GUH-2 cell grown in BHI broth without extraction. (B) Electron microscopy of the tip of a log-phase GUH-2 cell grown in BHI broth boiled in 1% SDS for 1 h. Bar, 1 μm. The cells in panels A and B are at the same magnification. (C) Western blot characterization of the SDS-extracted components. Lane 1, Western blot against the 43-kDa protein antigen (anti-43-kDa murine serum); lane 2, Western blot with IMS on the SDS extract; lane 3, Western blot against the 36-kDa protein antigen (anti-36-kDa murine serum); lane 4, silver stain after PAGE of the SDS extract from boiling log-phase GUH-2.

Sera with significant titers to specific protein bands from the culture filtrate were incubated with log- and stationary-phase GUH-2. The reactivity was visualized by indirect immunofluorescence labeling (Fig. 5). Antibodies reactive with the 43- and 36-kDa antigens (Fig. 4C, lanes 1 and 3) were the only ones that labeled the filament tips of log-phase GUH-2 cells as evidenced by very strong immunofluorescence (Fig. 5F and H). Both anti-31-kDa and anti-25-kDa (anti-superoxide dismutase [13]) antibodies bound to the surface of the entire filament exhibiting immunofluorescence, without increased intensity for the tip (Fig. 5J and K). Antibodies against the 55-kDa antigen did not label the bacterial filament (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, the antiserum reactive against the 62-kDa antigen labeled some of the filaments and not others in the same sample (Fig. 5A and B). The antiserum against the 62-kDa protein did not label the tip (Fig. 5A and B).

FIG. 5.

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy of N. asteroides GUH-2 treated with various murine antisera and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin. Fluorescence was visualized with epifluorescence illumination on a Ziess research microscope. (A) Phase-contrast micrograph of log-phase GUH-2 treated with anti-62-kDa antiserum. (B) Immunofluorescence of the same bacteria shown in panel A. Note the specific fluorescence localized along only portions of nocardial filaments, with no enhanced apical immunoreactivity. (C) Phase-contrast micrograph of log-phase GUH-2 treated with anti-55-kDa antiserum. (D) Immunofluorescence of the same bacteria shown in panel C. Only slight autofluorescence was evident. (E) Phase-contrast micrograph of log-phase GUH-2 treated with anti-43-kDa antiserum. (F) Immunofluorescence of the same bacterium shown in panel E. Note the strong specific fluorescence localized at the filament tip. (G) Phase-contrast micrograph of log-phase GUH-2 treated with anti-36-kDa antiserum. (H) Immunofluorescence of the same bacteria shown in panel G. Note the strong specific fluorescence localized at the filament tips. (I) Phase-contrast micrograph of log-phase GUH-2 treated with anti-31-kDa antiserum. (J) Immunofluorescence of the same bacterium shown in panel I. Note the specific fluorescence along the nocardial filament, with no enhanced apical immunoreactivity. (K) Immunofluorescence of log-phase GUH-2 treated with anti-25-kDa antiserum. (This 25-kDa protein appears to be nocardial superoxide dismutase [13].) Specific fluorescence was shown along the nocardial filament, with no enhanced apical immunoreactivity.

FTAAs of GUH-2 involved in pulmonary adherence and invasion.

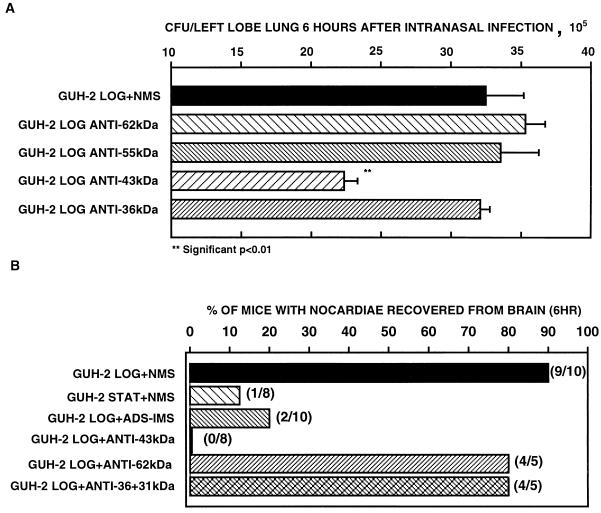

Log-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2 were incubated with either anti-62-kDa, anti-55-kDa, anti-43-kDa or anti-36-kDa serum and instilled into the lungs of C57BL/6 mice as described above. This experiment was to determine whether any of these proteins were involved in adherence to and penetration of the lung. Scanning electron microscopy confirmed that log-phase filaments of GUH-2 incubated with NMS penetrated bronchiolar epithelial cells (Fig. 6A), attached apically to alveolar septa (Fig. 6B), and penetrated the surface of alveolar epithelial cells (Fig. 6C). The attachment to and penetration of these cells within the lungs by nocardial filaments incubated with either anti-62-kDa, anti-55-kDa, or anti-36-kDa serum were not visibly altered (Fig. 6D, E, F, J, and K). In contrast, filaments incubated with anti-43-kDa serum exhibited only longitudinal association with pulmonary cells (Fig. 6G, H, and I). Very few bacterial cells were observed either adhering apically to or penetrating into pulmonary epithelial cells after incubation with antibody specific for the 43-kDa antigen. Stationary-phase bacilli of GUH-2 in NMS did not penetrate epithelial cells. Instead, they were embedded in a mucous layer on the surface of ciliated epithelial cells (Fig. 6L). Pulmonary clearance was enhanced only in the animals inoculated with GUH-2 pretreated with anti-43-kDa serum (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 6.

Scanning electron micrographs showing the effects of antisera against selected surface-associated protein antigens of N. asteroides GUH-2 on invasion of bronchiolar and alveolar epithelial cells. Bars, 1 μm. (A) Nocardial filaments incubated with NMS (control) among bronchiolar Clara cells, showing nocardial penetration into these epithelial cells (arrows). (B) Nocardial filament incubated with NMS (control), showing apical adherence to an alveolar septum (arrow). (C) Nocardial filaments incubated with NMS (control), showing both apical adherence to and penetration of the alveolar surface (arrows). (D) Low-magnification view showing nocardial filaments incubated with anti-62-kDa antiserum among the Clara cells and not specifically associated with ciliated cells (compare with Fig. 2A). (E) High-magnification view showing nocardial filaments (treated with anti-62-kDa antiserum) penetrating into epithelial cells (arrows) (compare to controls). (F) Nocardial filaments incubated with anti-55-kDa antiserum penetrating into bronchiolar epithelial cells (arrows), as observed for NMS controls (panel A). (G) Low-magnification view showing nocardial filaments incubated with anti-43-kDa antiserum among bronchiolar cells. Note the apparent association with cilia and possible longitudinal adherence to a Clara cell (compare to panel D). (H) Same as panel G, but a different region showing tighter longitudinal adherence of nocardial filament to a Clara cell. Note the absence of apical adherence to and penetration of bronchiolar epithelial cells. (I) Nocardial filament incubated with anti-43-kDa antiserum, exhibiting longitudinal adherence to an alveolar cell (arrow) (compare to panel B). (J) Nocardial filament incubated with anti-36-kDa antiserum penetrating into a bronchiolar epithelial cell (arrow), as observed for the NMS control (panel A). (K) A branched nocardial filament incubated with anti-36-kDa antiserum, showing apical penetration of the alveolar surface (arrow). (L) Stationary-phase cells of GUH-2 appear to be embedded in a mucous material lying on the surface of ciliated bronchiolar epithelial cells. Note that apical adherence to and penetration of pulmonary epithelial cells were not observed.

FIG. 7.

(A) Effects of selected antisera against individual secreted protein antigens of N. asteroides GUH-2 on pulmonary clearance 6 h after i.n. administration. (B) Effects of different antisera on the spread of N. asteroides GUH-2 to the brains of C57BL/6 mice 6 h after i.n. administration of approximately 2 × 106 CFU/left lobe of lung (positive mice/total mice studied). LOG, log phase; STAT, stationary phase.

Nocardial invasion of pulmonary epithelial cells with spread to the brain.

Previous studies showed that log-phase filaments of N. asteroides GUH-2 adhered to and penetrated epithelial cells in murine lungs (4). Frequently organisms were isolated from the brains of these mice (5a). This invasion of the lungs and spread to the brain were not observed following i.n. administration of stationary-phase cells of GUH-2. Therefore, log-phase cells of GUH-2 were instilled into the lungs of C57BL/6 mice by i.n. administration, and the numbers of bacteria in the brains were quantified. At different times, ranging from 3 h to 5 days, 63.6% (14 of 22) of the animals had nocardiae in the brain. It was important for the following studies to know the critical time to evaluate spread to the brain, because not all mice from each time period had nocardiae in the brain. Six hours after i.n. infection, a greater percentage of the mice had nocardiae in the brain than at any other time selected. These data suggested that 6 h was the optimal time for counting nocardiae in the brain. Most of the mice inoculated with nocardiae preincubated in either NMS or anti-62-kDa, anti-55-kDa, or anti-36-kDa serum had organisms recoverable from the brain 6 h after i.n. infection (Fig. 7B). In contrast, animals that received bacteria treated with either ADS-IMS or anti-43-kDa serum did not (Fig. 7B).

Interaction of nocardiae with the surface of HeLa cells.

Nocardiae incubated with ADS-IMS were typically embedded in mucus that prevented physical contact between the nocardial tip and host cells (Fig. 2C). Therefore, an in vitro assay with HeLa cells was utilized to clarify the relationship among apical adherence, host cell penetration, and internalization (invasion).

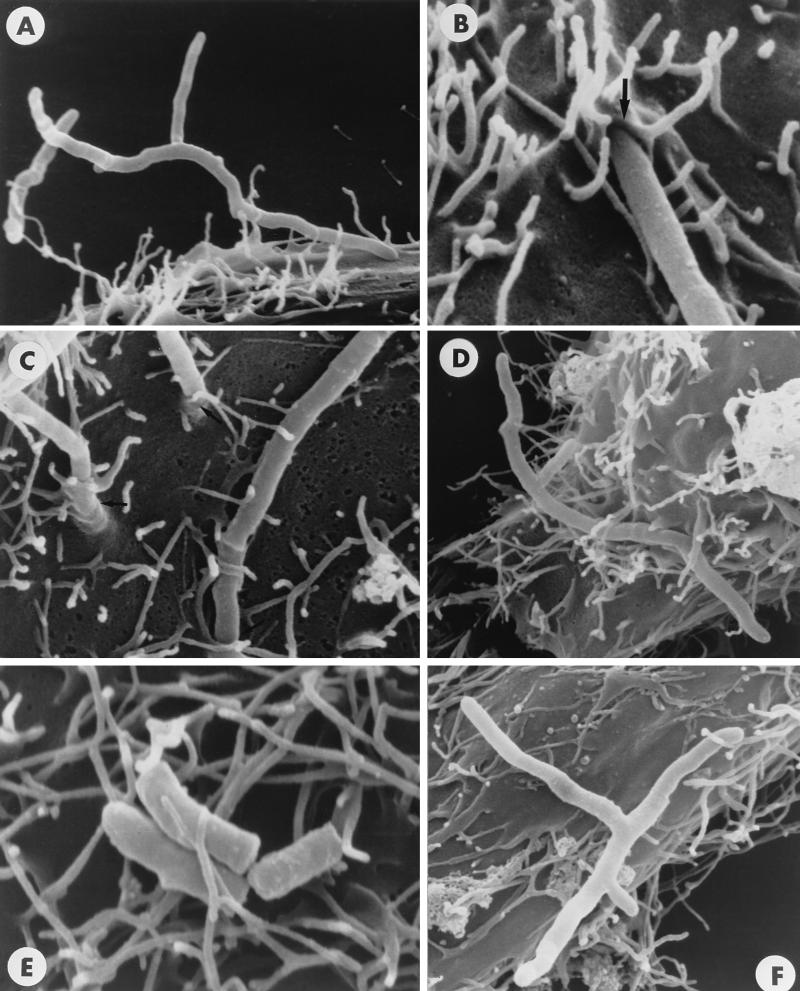

HeLa cell monolayers were incubated with either log-phase or stationary-phase N. asteroides GUH-2 for 1 h. The samples were washed with HBSS and prepared for scanning electron microscopy. Log-phase cells of GUH-2 attached apically (Fig. 8A) and penetrated the surface of HeLa cells (Fig. 8B and C). Both log-phase (Fig. 8D) and stationary-phase (Fig. 8E) cells adhered longitudinally to HeLa cells, but only log-phase nocardiae that were adherent at the tip of the filament penetrated the surface (compare Fig. 8A to D with F). These data suggest that there are at least two different attachment mechanisms. The apical attachment of log-phase cells was distinct from the longitudinal surface attachment of stationary-phase cells.

FIG. 8.

Scanning electron micrographs showing surface interactions of N. asteroides GUH-2 incubated with HeLa cells for 1 h. (A) Apical attachment of log-phase GUH-2 to the surface of a HeLa cell (incubated with FCS and NMS). (B) The arrow shows apical penetration of the HeLa cell surface by a log-phase filament of GUH-2 (incubated with FCS only). (C) Tips of three log-phase filaments of GUH-2 penetrating the surface of the HeLa cell (incubated with FCS and NMS). (D) Longitudinal attachment of a log-phase filament of GUH-2 (incubated with FCS and NMS). (E) Longitudinal attachment of stationary-phase GUH-2 to the surface of HeLa cells (incubated with FCS and NMS). Neither apical adherence nor penetration of the HeLa cell surface was observed. (F) Log-phase filament of GUH-2 incubated with FCS and ADS-IMS prior to incubation with HeLa cells. Few bacteria showed apical penetration. Magnifications are indicated by the nocardial filament diameter of approximately 0.5 μm.

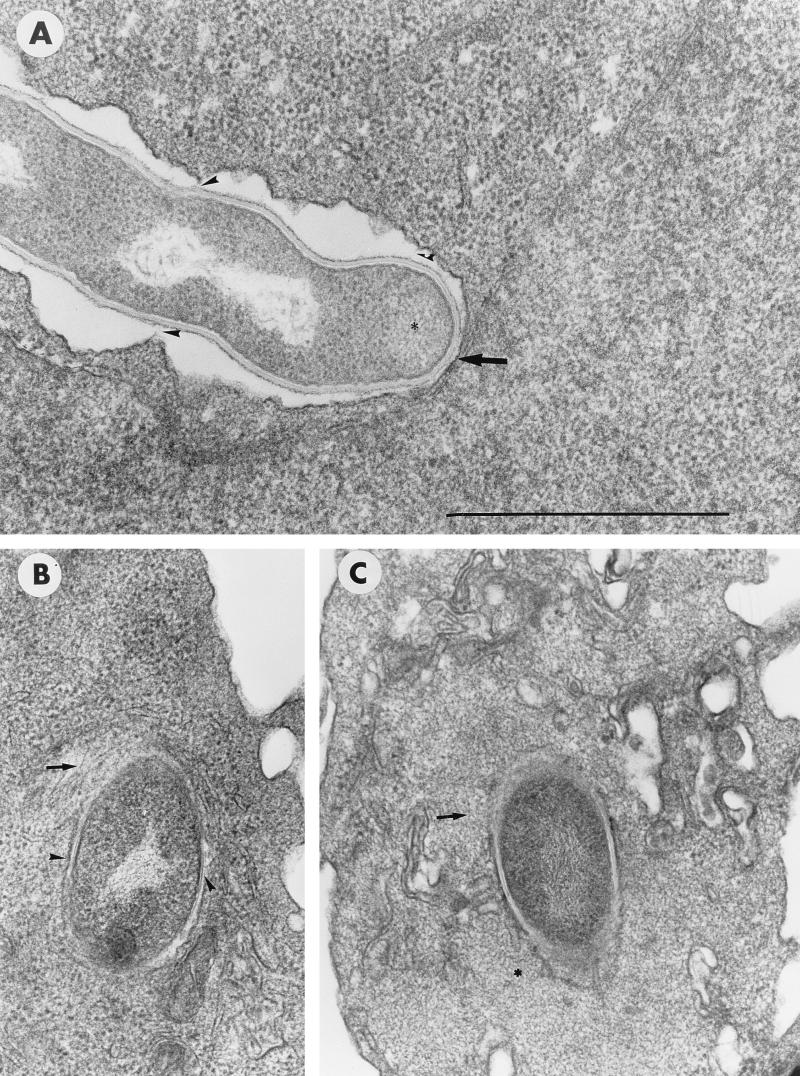

Ultrastructural analysis revealed that the outermost, electron-dense layer of the cell wall surrounding the growing tip of log-phase cells of GUH-2 was tightly adherent to the cytoplasmic membrane of the HeLa cell during penetration (Fig. 9A). As the nocardiae extended into the host cell, there were several places along the filament where the HeLa cell cytoplasmic membrane remained adherent to the cell wall (Fig. 9A). Nevertheless, most of the filament length was separated from the HeLa cell membrane by a space (Fig. 9A). Once the bacterial cell became totally intracellular (as determined by serial sections), it was enclosed in a tightly associated, membrane-bound vesicle (Fig. 9B and C) surrounded by an array of cytoplasmic microfilaments (Fig. 9B).

FIG. 9.

Transmission electron microscopy of log-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2 in FCS incubated for 1 h with HeLa cells. (A) Filament tip penetrating the surface of the HeLa cell as in Fig. 1B. The arrow indicates a tight association of electron-dense material on the filament apex with the cytoplasmic membrane of the HeLa cell. Arrowheads indicate apparent sites of attachment between the outer filament wall and the HeLa cell membrane. Bar, 1.0 μm. (B) Nocardial filament localized within the HeLa cell. The arrow indicates microfilaments surrounding the internalized nocardia, and the arrowhead indicates a tight association of the host cell membrane surrounding the nocardial cell. (C) A different preparation showing the same features of internalized log-phase cells of GUH-2 in HeLa cells as in panel B. The asterisks indicate the presence of a granular material. In panel A, the asterisk indicates activity seen with actively growing filament tip. In panel C, the asterisk indicates the host cell, showing a region of increased metabolic activity.

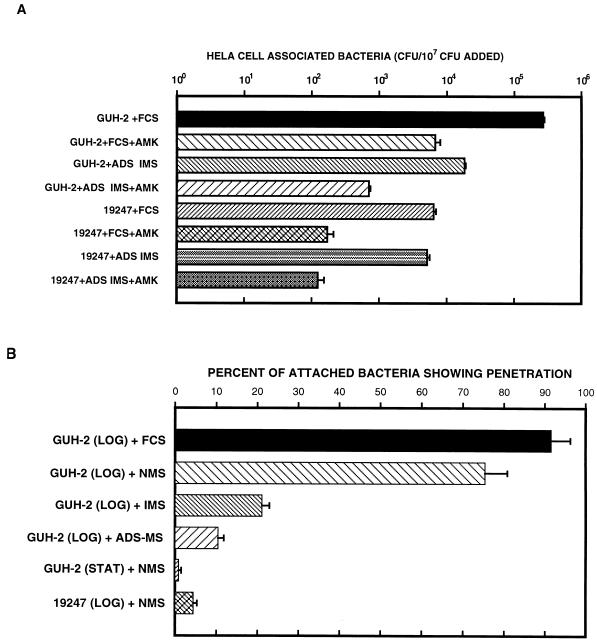

Adherence to and internalization of N. asteroides in HeLa cells.

HeLa cells were incubated with approximately 107 CFU of log-phase cells of either N. asteroides GUH-2 or 19247 (Fig. 10A). At 3 h, significantly more CFU of GUH-2 than of ATCC 19247 were adherent to HeLa cells (P < 0.001) (Fig. 10A). Incubation of the bacterial cells with adsorbed serum from immunized mice reduced the numbers of adherent GUH-2 cells by 93% (P < 0.001), whereas a nonsignificant decrease in adherence of only 19% (P < 0.05) was observed with strain ATCC 19247 (Fig. 10A). Amikacin treatment of the HeLa cells with nocardiae permitted quantitation of the totally internalized organisms. After 3 h of incubation of log-phase cells of GUH-2 with HeLa cells, 2.5% of the HeLa cell-associated CFU were intracellular (P < 0.001) (Fig. 10A). Approximately 40 times more GUH-2 cells than ATCC 19247 cells were internalized (P < 0.001). Pretreatment of GUH-2 with ADS-IMS resulted in a 96% reduction in internalization (P < 0.001). In contrast, there was no significant effect on the internalization of ATCC 19247 by ADS-IMS (Fig. 10A).

FIG. 10.

(A) Quantitation of the relative numbers (log10) of log-phase cells of an invasive strain (GUH-2) and a noninvasive strain (ATCC 19247) of N. asteroides adhering to and invading HeLa cells as determined with an amikacin (AMK) killing assay. Error bars indicate standard errors. (B) Quantitative scanning electron microscopy estimation of the effects of different murine sera on apical attachment to and penetration of HeLa cells by N. asteroides. The average percentage of attached nocardiae showing evidence of penetration of the HeLa cell surface (calculated as total number of tips showing penetration/total number of bacteria attached) is shown. Error bars indicate standard errors (three separate experiments). LOG, log phase; STAT, stationary phase (see Materials and Methods).

Quantitative scanning electron microscopic characterization of nocardial penetration of HeLa cells.

Adherence and internalization as determined by viability provided an analysis of a population. Quantification of CFU did not provide information on the interactions between the surface of the HeLa cells and the nocardiae. Therefore, quantitative scanning electron microscopy was utilized to characterize further the attachment to and penetration of HeLa cells by nocardiae (Fig. 10B). Cell suspensions of log- and stationary-phase nocardiae were divided into groups and incubated with the following (as described above): (i) FCS alone, (ii) FCS as a blocking agent followed by NMS, (iii) FCS followed by IMS, and (iv) FCS followed by ADS-IMS. The number of nocardiae showing either longitudinal or apical adherence to the surface of each HeLa cell was tabulated for each group. At the same time, the number of nocardial tips penetrating the surface of these HeLa cells in each preparation was determined (Fig. 10B). Several hundred HeLa cells were counted in order to obtain at least 100 adherent nocardial cells from each sample. The filament tips of log-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2 adhered significantly better to HeLa cells than either stationary-phase GUH-2 or log-phase ATCC 19247 (data not shown). Both IMS and adsorbed IMS prevented apical attachment of GUH-2. Approximately 80% of the adherent log-phase cells of GUH-2 in NMS penetrated the host cell surface (Fig. 8C and 10B). In contrast, fewer than 10% of the adherent log-phase cells of GUH-2 incubated with ADS-IMS showed evidence of penetration (Fig. 8F and 10B). Neither stationary-phase GUH-2 nor avirulent N. asteroides ATCC 19247 penetrated HeLa cells. These data suggested that the log-phase, filamentous cells of the invasive strain GUH-2 possessed surface antigens important for attachment to and penetration of HeLa cells. These same components were either diminished in amount or absent from the surfaces of both stationary-phase cells and avirulent nocardiae (Fig. 10B).

DISCUSSION

A variety of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria specifically adhere to and invade host cells (27). Numerous studies report that distinct bacterial surface proteins mediate both the attachment to and invasion of these cells. Furthermore, it appears that different proteins may be involved in these processes, depending on the type of pathogen (27). For example, Mycobacterium tuberculosis invasion of host cells is facilitated by different surface components than for either the gram-positive Listeria monocytogenes or the gram-negative Yersinia species (3, 16, 25). Nevertheless, the adherence and invasion proteins related to the virulence of most gram-negative pathogens appear to be interrelated and encoded on plasmids (27, 34). It is not known whether similar paradigms occur with invasive, gram-positive pathogens. Adherence to and invasion of cells by L. monocytogenes is one of the most characterized systems among gram-positive bacteria (20, 24, 25). Several distinct surface proteins, such as ActA, the products of the internalin multigene family (i.e., inlA, inlB, inlC, inlD, inlE, and inlF), and listeriolysin O, are implicated in listerial adherence to and invasion of host cells (20, 24, 25). Most of these proteins appear to be under coordinated chromosomal control by the virulence regulator gene product PrfA (23), and many of them are maximally expressed during the log phase of growth (24).

The complex nocardial cell envelope changes during the growth cycle, and log-phase filamentous cells of N. asteroides possess surface structures different from those of stationary-phase coccoid cells from the same culture. Many of these alterations appear to correspond with specific modifications in virulence and nocardial interactions with host cells (6, 7). Most strains of N. asteroides in the log phase of growth are significantly more virulent for mice than are stationary-phase cells. Thus, filamentous, log-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2 behave like invasive, primary pathogens, whereas coccobacillary cells of GUH-2 act more like opportunistic organisms (6).

Filamentous cells of virulent strains of N. asteroides attach to and invade a variety of host cells both in vitro and in vivo (4, 14, 15). This attachment and penetration appear to be mediated by components located on the apex of the growing nocardial filament (FTAAs). However, at the stationary phase of growth, the nocardial filaments have fragmented into pleomorphic, coccobacillary cells that do not exhibit either apical attachment to or penetration of these same host cells (14, 15). The data presented above suggested strongly that the FTAAs of log-phase cells of N. asteroides GUH-2 contained 43- and 36-kDa proteins. The 43-kDa protein was either absent or significantly diminished on the surface of stationary-phase cells from the same culture, whereas both 36- and 62-kDa antigens were visualized by immunofluorescence labeling. The tip-associated 43-kDa protein appeared to play a dominant role in adherence to and invasion of pulmonary epithelial cells followed by dissemination to the brain.

N. asteroides GUH-2 not only adheres to and invades pulmonary epithelial cells as described above but also adheres to and invades capillary endothelial cells within specific regions of the brain (10). In contrast, N. asteroides UC-63 (UC-63 is a highly virulent, clinical isolate from a human brain) invades capillary endothelial cells in the murine brain like GUH-2, but it neither binds apically to nor invades pulmonary epithelial cells (4). The sera from mice nonlethally infected with GUH-2 are strongly positive against 90-, 62-, 55-, 43-, 36-, 31-, and 25-kDa culture filtrate protein antigens in Western immunoblots (29). However, mice infected with a nonlethal dose of UC-63 demonstrate strong immunoreactivity only to 68-, 55-, 36-, 31-, and 25-kDa antigens from GUH-2 (29). There is no detectable immunoreactivity against the 43-kDa antigen of GUH-2 in mice infected with UC-63 (29). Indeed, the strongest response in these UC-63-infected mice was against the 36-kDa antigen (29). These observations support the hypothesis that at least two different nocardial surface components are involved in adherence to and invasion of endothelial cells in the brain compared to epithelial cells in the lungs. The data presented above suggest that the 43-kDa antigen is involved in nocardial attachment to and invasion of epithelial cells in the lung.

The epithelial cell surface receptors that facilitated FTAA adherence appeared not to be ECM proteins as reported with other invasive pathogens (21, 33, 37, 41). It is interesting that antibody to the 36-kDa protein labeled strongly the filament tips of log-phase GUH-2 cells. At the same time, it appeared that this 36-kDa protein bound to the ECM protein laminin. However, ECM binding proteins appeared to be present on stationary-phase GUH-2 cells, and they may be involved in the interactions of these organisms with host cells (data not shown). Clearly, additional research is needed to understand more completely the nature and roles of FTAAs in selective specificity for nocardial adherence, invasion, and dissemination.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Portions of this research were supported by Public Health Service grants RO1-AI20900 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and RO1-HL59821 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

We thank Judith A. Kjelstrom for preparing some of the murine antisera used in these studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arruda S, Bomfim G, Knights R, Huima-Byron T, Riley L W. Cloning of an M. tuberculosis DNA fragment associated with entry and survival inside cells. Science. 1993;261:1454–1456. doi: 10.1126/science.8367727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba T, Nishiuchi Y, Yano I. Composition of mycolic acid molecular species as a criterion in nocardial classification. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:795–801. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badger J L, Miller V L. Expression of invasion and motility are coordinately regulated in Yersinia enterocolitica. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:793–800. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.793-800.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaman B L. Differential binding of Nocardia asteroides in the murine lung and brain suggests multiple ligands on the nocardial surface. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4859–4862. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4859-4862.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaman B L. Interaction of Nocardia asteroides at different phases of growth with in vitro-maintained macrophages obtained from the lungs of normal and immunized rabbits. Infect Immun. 1979;26:355–361. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.1.355-361.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Beaman, B. L. Unpublished observations.

- 6.Beaman B L, Beaman L. Nocardia: host-parasite relationships. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:213–264. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaman B L, Goldstein E, Gershwin M E, Maslan S, Lippert W. Lung response of congenitally athymic (nude), heterozygous, and Swiss Webster mice to aerogenic and intranasal infection by Nocardia asteroides. Infect Immun. 1978;22:867–877. doi: 10.1128/iai.22.3.867-877.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaman B L, Maslan S. Virulence of Nocardia asteroides during its growth cycle. Infect Immun. 1978;20:290–295. doi: 10.1128/iai.20.1.290-295.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaman B L, Moring S E. Relationship among cell wall composition, stage of growth, and virulence of Nocardia asteroides GUH-2. Infect Immun. 1988;56:557–563. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.3.557-563.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaman B L, Ogata S A. Ultrastructural analysis of attachment to and penetration of capillaries in the murine pons, midbrain, thalamus, and hypothalamus by Nocardia asteroides. Infect Immun. 1993;61:955–965. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.955-965.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beaman B L, Saubolle M A, Wallace R J. Nocardia, Rhodococcus, Streptomyces, Oerskovia, and other aerobic actinomycetes of medical importance. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 329–399. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaman B L, Sugar A M. Nocardia in naturally acquired and experimental infections in animals. J Hyg. 1983;91:393–419. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400060447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beaman L, Beaman B L. Monoclonal antibodies demonstrate that superoxide dismutase contributes to protection of Nocardia asteroides within the intact host. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3122–3128. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.3122-3128.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beaman L, Beaman B L. Interactions of Nocardia asteroides with murine glia cells in culture. Infect Immun. 1993;61:343–347. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.343-347.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beaman L, Beaman B L. Differences in the interactions of Nocardia asteroides with macrophage, endothelial, and astrocytoma cell lines. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1787–1798. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1787-1798.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bermudez L E, Goodman J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis invades and replicates within type II alveolar cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1400–1406. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1400-1406.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bermudez L E, Young L S. Factors affecting invasion of HT-29 and HEp-2 epithelial cells by organisms of the Mycobacterium avium complex. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2021–2026. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.2021-2026.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black C M, Beaman B L, Donovan R M, Goldstein E. Intracellular acid phosphatase content and ability of different macrophage populations to kill Nocardia asteroides. Infect Immun. 1985;47:375–383. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.2.375-383.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Black C M, Paliescheskey M, Beaman B L, Donovan R M, Goldstein E. Acidification of phagosomes in murine macrophages: blockage by Nocardia asteroides. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:952–958. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.6.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun L, Dramsi S, Dehoux P, Bierne H, Lindahl G, Cossart P. InlB: an invasion protein of Listeria monocytogenes with a novel type of surface association. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:285–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4621825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byrd S R, Gelber R, Bermudez L E. Roles of soluble fibronectin and β1 integrin receptors in the binding of Mycobacterium leprae to nasal epithelial cells. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;69:266–271. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis-Scibienski C, Beaman B L. Interaction of alveolar macrophages with Nocardia asteroides: immunological enhancement of phagocytosis, phagosome-lysosome fusion, and microbicidal activity. Infect Immun. 1980;30:578–587. doi: 10.1128/iai.30.2.578-587.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domann E, Zechel S, Lingnau A, Hain T, Darji A, Nichterlein T, Wehland J, Chakraborty T. Identification and characterization of a novel PrfA-regulated gene in Listeria monocytogenes whose product, IrpA, is highly homologous to internalin proteins, which contain leucine-rich repeats. Infect Immun. 1997;65:101–109. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.101-109.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dramsi S, Dehoux P, Lebrun M, Goosens P L, Cossart P. Identification of four new members of the internalin multigene family of Listeria monocytogenes EGD. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1615–1625. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1615-1625.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drevets D A. Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors that stimulate endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:232–238. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.232-238.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filice G A, Beaman B L, Krick J A, Remington J S. Effects of human neutrophils and monocytes on Nocardia asteroides: failure of killing despite occurrence of the oxidative metabolic burst. J Infect Dis. 1980;142:432–438. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finlay B B, Falkow S. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:136–169. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.136-169.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kita J, Maciolek H. Nocardiosis in animals. Medyc Weterynar. 1996;52:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kjelstrom J A, Beaman B L. Development of a serological panel for recognition of nocardial infections in a murine model. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;16:291–301. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(93)90079-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee P Y C, Hillier C E M, Viagappan G M. Gingivitis, facial weakness, and focal seizures—brain abscess due to Nocardia asteroides. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73:327–328. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.73.860.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lerner P I. Nocardiosis: state-of-the-art article. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:891–905. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Machado C M, Macedo M C, Castelli J B, Ostronoff M, Silva A C, Zambon E, Massumoto C, Chamone D F, Dulley F L. Clinical features and successful recovery from disseminated nocardiosis after BMT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:81–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMahon J P, Wheat J, Sobel M E, Pasula R, Downing J F, Martin W J., II Murine laminin binds to Histoplasma capsulatum: a possible mechanism of dissemination. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1010–1017. doi: 10.1172/JCI118086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer D H, Mintz K P, Fives-Tayler P M. Models of invasion of enteric and periodontal pathogens into epithelial cells: a comparative analysis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1997;8:389–409. doi: 10.1177/10454411970080040301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mounier J, Bahrani F K, Sansonetti P J. Secretion of Shigella flexneri Ipa invasins on contact with epithelial cells and subsequent entry of the bacterium into cells are growth stage dependent. Infect Immun. 1997;65:774–782. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.774-782.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orsolon P, Bagni B, Talmassons G, Guerra U P. Evaluation of a patient with a brain abscess caused by Nocardia asteroides infection with Ga-67 and Tc-99m HMPAO leukocytes. Clin Nucl Med. 1997;22:407–408. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199706000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plotkowski M C, Tournier J M, Puchelle E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains possess specific adhesins for laminin. Infect Immun. 1996;64:600–605. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.600-605.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schorey J S, Li Q, McCourt D W, Bong-Mastek M, Clark-Curtiss J E, Ratliff T L, Brown E J. A Mycobacterium leprae gene encoding a fibronectin binding protein is used for efficient invasion of epithelial cells and Schwann cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2652–2657. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2652-2657.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sechi A S, Wehland J, Small J V. The isolated comet tail pseudopodium of Listeria monocytogenes: a tail of two actin filament subpopulations, long and axial and short and random. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:155–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tran van Nhieu G, Ben-Ze’ev A, Sansonetti P J. Modulation of bacterial entry into epithelial cells by association between vinculin and the Shigella Ipa invasin. EMBO J. 1997;16:2717–2729. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tronchin G, Esnault K, Renier G, Filmon R, Chabasse D, Bouchara J P. Expression and identification of a laminin-binding protein in Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. Infect Immun. 1997;65:9–15. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.9-15.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uttamchandani R B, Daikos G L, Reyes R R, Fischl M A, Dickinson G M, Yamaguchi E, Kramer M R. Nocardiosis in 30 patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection: clinical features and outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:348–353. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.3.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]