Abstract

This paper describes a new role for the cysteine-cysteine (CC) chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β on human macrophage function, which is the induction of nitric oxide (NO)-mediated trypanocidal activity. In a previous report, we showed that RANTES, MIP-1α and MIP-1β enhance Trypanosoma cruzi uptake and promote parasite killing by human macrophages (M. F. Lima, Y. Zhang, and F. Villalta, Cell. Mol. Biol. 43:1067–1076, 1997). Here we study the mechanism by which RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β activate human macrophages obtained from healthy individuals to kill T. cruzi. Treatment of human macrophages with different concentrations of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β enhances T. cruzi trypomastigote phagocytosis in a dose peak response. The optimal response induced by the three CC chemokines is attained at 500 ng/ml. The macrophage trypanocidal activity induced by CC chemokines can be completely inhibited by l-N-monomethyl arginine (l-NMMA), a specific inhibitor of the l-arginine:NO pathway, but not by its d-enantiomer. Culture supernatants of chemokine-treated human macrophages contain increased NO2− levels, and NO2− production is also specifically inhibited by l-NMMA. The amount of NO2− induced by these chemokines in human macrophages is comparable to the amount of NO2− induced by gamma interferon. The killing of trypomastigotes by NO in cell-free medium is blocked by an NO antagonist or a NO scavenger. This data supports the hypothesis that the CC chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β activate human macrophages to kill T. cruzi via NO, which is an effective trypanocidal mechanism.

As the role of the cysteine-cysteine (CC) family of chemokines in immunological processes continues to be defined, it is clear that their cellular influence and biological activities are broader and encompass more than simply chemoattraction. In fact, other functions beside chemotaxis, such as their participation in angiogenesis and neovascularization, resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), T-cell costimulatory activities (reviewed in references 2 and 46), and enhancement of NK-mediated cytolysis (45), have been reported. The mechanism by which CC chemokines activate human macrophages to exert cytotoxicity is unknown. In this study, we have explored the role of the CC chemokines RANTES, MIP1-α, and MIP-1β on human macrophage cytotoxic cell function against the human parasite Trypanosoma cruzi by examining their mechanism of trypanosome toxicity within macrophages.

T. cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas’ disease, is an obligate intracellular pathogen of several cells including cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage (4). This organism is now viewed as an emerging human pathogen of HIV-1-infected individuals, since it induces dramatic pathologic changes in the brain and results in earlier death when associated with HIV-1 infections (9, 39). The possible emergence of T. cruzi as an opportunistic infection of HIV-1-infected individuals in the United States has recently been considered (30). Inflammatory molecules have been postulated to play a role in the clearance of T. cruzi, since control of the acute phase of Chagas’ disease is critically dependent on cytokine-mediated macrophage activation. For instance, treatment of macrophages with gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (36), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (33, 37), or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (27) induces T. cruzi killing whereas transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) inhibit the trypanocidal action of IFN-γ-activated macrophages (14).

Chemokines mediate inflammatory reactions (3, 40–42) and show potential leukocyte activation and/or chemotactic activity (11). CC chemokines act primarily on monocytes but also have been shown to act on basophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes including Th2 cells, astrocytes, dendritic cells, fibroblasts, and hematopoietic cells (reviewed in references 2 and 46). CC chemokines include MIP-1α and MIP-1β (macrophage inflammatory proteins 1α and 1β), RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T expressed and secreted), MCP-1 through MCP-3 (7), I-309, Eotaxin, C10, HCC-1 (2, 46), and 6Ckine (16). The proinflammatory activities of CC chemokines overlap but are not identical (8); MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES bind to a common receptor, suggesting that there are structural similarities among them (8).

Chemokines play important roles in immunopathogenesis and may selectively recruit cells into sites of antigenic challenge (7). They are active on lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages upon binding to G-protein-coupled seven-transmembrane-domain surface receptors (13, 31). It was recently shown that HIV-1 entry into human macrophages is inhibited by MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES (6, 21) and that CCKR5, the RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β receptor, functions as a coreceptor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1 (1).

The objective of this study was to investigate the microbicidal mechanism induced by these inflammatory secreted proteins in human macrophages infected with infective trypomastigote forms of T. cruzi. In this work, we describe a new role for the CC chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β on human macrophage function, which is the induction of microbicidal activity of these cells via NO.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms.

Tulahuen strain trypomastigotes (the highly infective clone MMC 20A) of T. cruzi (23) were obtained as described previously (22, 53). Pure-culture trypomastigotes were washed with Dulbecco’s modified minimal essential medium containing 100 μg of streptomycin per ml and 100 U of penicillin per ml (DMEM) and resuspended at 107 organisms/ml in DMEM supplemented with 1% crystallized bovine albumin (DMEM-BSA) (Bayer Corp., Kankakee, Ill.).

Human macrophages.

Human monocytes isolated from anonymous healthy individuals (American Red Cross, Portland, Oreg.) by gradient centrifugation on Ficoll followed by Percoll gradient (Pharmacia Biotechnology, Piscataway, N.J.), as described previously (22), were washed in RPMI and resuspended in RPMI supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, Utah), 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Life Technology, Grand Island, N.Y.), 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 100 U of penicillin per ml. The monocytes were plated in Lab-Tek chambers (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, Ill.) at 2 × 105 cells/well. Purity was analyzed with OKM-1 monoclonal antibody. Mononuclear phagocytic cell monolayers consisted of >99% nonspecific esterase-positive cells. The monocytes were differentiated into macrophages for 4 weeks before CC chemokine treatments and T. cruzi infection assays. FACScan analysis of macrophage preparations showed 97 to 99% purity with the macrophage marker CD14.

Materials.

Purified recombinant human RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.). Purified recombinant human IFN-γ was obtained from ENDOGEN (Worburn, Mass.). l-N-monomethyl arginine (l-NMMA), d-NMMA, diethylamine nitric oxide (DEANO), 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide potassium salt (carboxy PTIO), and the Griess reagent kit were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oreg.).

Uptake of trypomastigotes by human macrophages.

The procedures for uptake of trypomastigotes by human macrophages have been described in detail previously (32, 49). The effect of CC chemokines on the uptake of T. cruzi trypomastigotes by human macrophages was initially evaluated by using different concentrations of CC chemokines ranging from 100 to 1,000 ng/ml at a 10:1 ratio of trypomastigotes to macrophages. After the optimal concentration of chemokines was selected, experiments were performed at a 10:1 ratio of trypomastigotes to macrophages and a final optimal concentration of 500 ng of chemokines/ml or in their absence. Briefly, macrophages were washed with DMEM and incubated with DMEM-BSA alone or supplemented with RANTES, MIP-1α, or MIP-1β. The cultures then received trypomastigotes in DMEM-BSA and were further incubated for 2 h. Under these conditions, cell-bound trypanosomes were ingested by macrophages (49, 52), as confirmed by electron microscopy (results not shown). Unbound trypomastigotes were removed by washing the cells with DMEM; after fixing and staining with Giemsa, the percentage of cells containing T. cruzi and the number of trypanosomes internalized per 200 cells were microscopically determined.

Treatment of human macrophages with NO inhibitors during uptake and killing of T. cruzi.

Human macrophages were pretreated with 1 mM l-NMMA or 1 mM d-NMMA for 4 h at 37°C in complete RPMI (12). The macrophages were then washed three times with RPMI and received the same concentration of drugs in RPMI in the absence of FBS and in the presence of 500 ng of CC chemokines/ml. After a 30 min preincubation, trypomastigotes were added to these cultures at a ratio of 10:1 trypomastigotes to macrophages. The mixture of parasites and macrophages was incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After this time, unbound trypomastigotes were removed by washing with DMEM and the percentage of cells containing T. cruzi and the number of trypanosomes internalized per 200 cells were microscopically determined as described above. To study the intracellular fate of trypomastigotes in macrophages, the same procedure was used, but after the unbound trypanosomes were removed, some monolayers were fixed and the remaining cultures received fresh complete RPMI supplemented with 500 ng of CC chemokines/ml and 1 mM l-NMMA or 1 mM d-NMMA. Each day for the next 3 days, the macrophages were treated with CC chemokines and inhibitors in complete medium. After 72 h, the macrophages were fixed and stained and the number of intracellular parasites was determined (32, 49). Control experiments were performed in the absence of inhibitors and CC chemokines, in the presence of inhibitors and the absence of CC chemokines, and in the presence of CC chemokines alone.

Determination of NO2−.

The NO2− concentration in culture supernatants of human macrophages was determined, as an indicator of NO production, by using the Griess reagent (29).

Treatment of trypomastigotes with released NO, a NO antagonist, and a NO scavenger in cell-free medium.

Trypomastigotes were washed four times in degassed phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) and resuspended in the same buffer. All the reagents used were dissolved in degassed PBS immediately before the assay. Parasites (107/ml) were incubated with 200 μM DEANO (a NO carrier that spontaneously releases NO in PBS) (25), 200 μM DEANO–400 μM carboxy PTIO (a NO antagonist that reacts with NO and inhibits the physiological effect mediated by NO) (35), 200 μM DEANO–1 mg of hemoglobin (a NO scavenger) per ml (15), 400 μM carboxy PTIO, 1 mg of hemoglobin per ml, or PBS. Triplicate samples were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Aliquots of samples were diluted in DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS, and the number of viable trypomastigotes was microscopically determined. In these assays, the NO2− concentration was determined in triplicate, as NO equivalent, with the Griess reagent as indicated above.

Presentation of results and statistical analysis.

The results obtained in this work were from triplicate determinations and represent three independent experiments, performed by identical methods, with macrophages obtained from different healthy donors. The results are expressed as the mean ± 1 standard deviation. Differences were considered to be statistically significant if P ≤ 0.05 by the Student t test.

RESULTS

Treatment of human macrophages with different concentrations of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β enhances T. cruzi trypomastigote phagocytosis by human macrophages in a peak dose response.

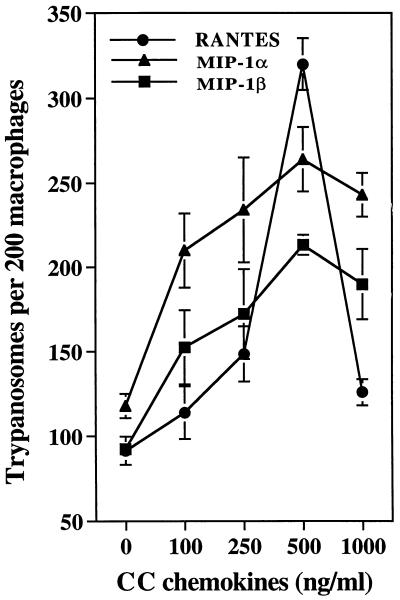

Figure 1 shows that the CC chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β enhance T. cruzi trypomastigote uptake by human macrophages in a concentration-dependent fashion. This was evidenced by a significant increase in both the number of macrophages containing trypomastigotes and the number of trypomastigotes ingested by these cells. The optimal concentration of CC chemokines that enhances trypomastigote phagocytosis by macrophages is 500 ng/ml. An early enhancing effect is seen at 100 ng/ml. The optimal CC chemokine concentration of 500 ng/ml was selected for the remaining experiments. The ability of these chemokines to increase trypanosome uptake by human macrophages was always chemokine concentration dependent and varied occasionally in experiments performed by similar methods but with cells from different healthy donors. However, a peak response at 500 ng/ml was always observed in the presence of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β.

FIG. 1.

Concentration-dependent effect of CC chemokines on the uptake of T. cruzi trypomastigotes by human macrophages. Several concentrations of CC chemokines were added to human macrophage monolayers in triplicate, and trypomastigote uptake was evaluated at 2 h, as described in Materials and Methods. This is a representative experiment of three experiments performed with similar results. Each bar represents the mean of triplicate determinations ± 1 standard deviation.

Inhibition of trypanocidal activity of CC chemokine-treated macrophages by l-NMMA.

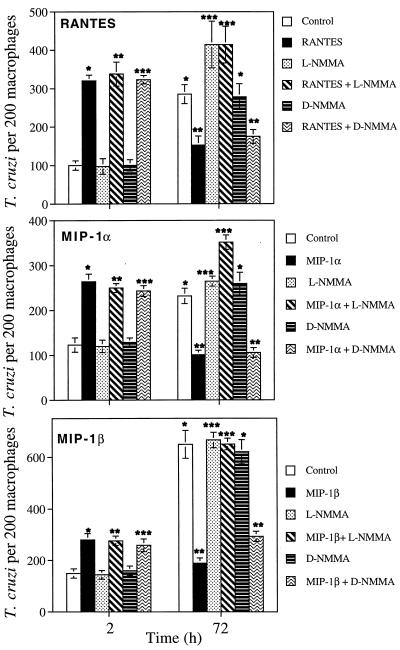

Since in a previous report we showed that RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β induce T. cruzi killing by human macrophages (24), we examined in this study the mechanism by which CC chemokine-activated human macrophages kill T. cruzi trypomastigotes. Accordingly, we investigated whether the intracellular fate of T. cruzi trypomastigotes within macrophages could be altered upon continuous exposure to CC chemokines in the presence of a nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor. Human macrophages were pretreated with 1 mM l-NMMA, a NOS inhibitor, or its inactive d enantiomer, d-NMMA, at the same concentration for 4 h, washed, and exposed to the same concentrations of l-NMMA or d-NMMA in the presence of 500 ng of CC chemokines/ml for 30 min, and then some cultures were infected with trypomastigotes and terminated at 2 h for parasite uptake evaluation. The remaining infected cultures were incubated for 72 h and received daily supplementation with fresh complete medium plus chemokines and inhibitors. l-NMMA and d-NMMA did not affect either the uptake of trypomastigotes or the enhancement of parasite uptake induced by RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β in human macrophages at 2 h (Fig. 2). Human macrophages incubated with RANTES and MIP-1α acquired strong trypanocidal activity. The cytotoxicity induced by MIP-1β was less intense. This effect was evident by the significant reduction in the number of intracellular parasites per macrophage induced by RANTES and MIP-1α at 72 h. MIP-1β caused a significant but slightly smaller reduction in the number of parasites, but under these conditions T. cruzi did not multiply within human macrophages, in contrast to control cultures at 72 h (Fig. 2). However, the ability of CC chemokine-treated macrophages to kill T. cruzi trypomastigotes was completed abrogated by 1 mM l-NMMA (Fig. 2). In contrast, the trypanocidal activity of CC chemokine-treated human macrophages was not affected by d-NMMA. Thus, the CC chemokine-induced human macrophage trypanocidal activity is completely inhibited by a specific inhibitor of the l-arginine NO pathway, indicating that this microbicidal activity is mediated by NO.

FIG. 2.

Effects of l-NMMA and d-NMMA on the trypanocidal activity of human macrophages induced by CC chemokines. Human macrophages were pretreated with RANTES, MIP-1α, or MIP-1β in the presence or absence of l-NMMA or d-NMMA and exposed to trypomastigotes at a ratio of 10 parasites/cell. Parasite uptake was evaluated at 2 h, and T. cruzi killing was evaluated at 72 h, as described in Materials and Methods. In trypanosome uptake at 2 h, ∗ represents a statistically significant change in trypanosome uptake compared to control in the presence of media. l-NMMA (∗∗) and d-NMMA (∗∗∗) do not affect the enhancement of uptake induced by CC chemokines in macrophages compared to their respective controls (P < 0.05). Differences between ∗ and ∗∗, P < 0.05, and differences between ∗∗ and ∗∗∗, P < 0.05, for in trypanosome killing at 72 h.

Production of NO2− by CC chemokine-treated human macrophages.

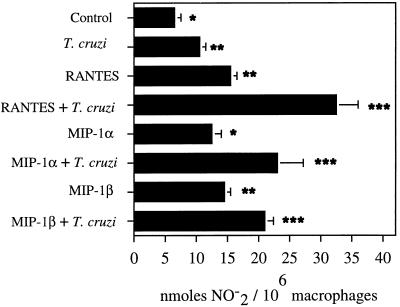

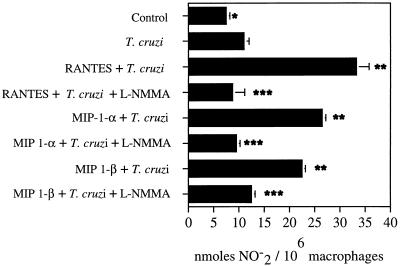

The ability of CC chemokine-treated human macrophages to kill T. cruzi intracellularly was accompanied by an increase in the NO2− concentration in culture supernatants (Fig. 3 and 4). T. cruzi is able to induce a modest increase in NO2− production by human macrophages when measured in culture supernatants (Fig. 3 and 4). Treatment of uninfected human macrophages with RANTES, MIP-1α, or MIP-1β caused an increase in the production of NO2− in macrophage culture supernatants. However, RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β were able to induce higher levels of NO2− in culture supernatants of T. cruzi-infected macrophages (Fig. 3 and 4). The level of NO2− was significantly decreased in culture supernatants of T. cruzi-infected human macrophages treated with l-NMMA and CC chemokines (Fig. 4). The levels of NO2− measured were indicative of NO production. Two different stimuli, chemokines (RANTES, MIP-1α, or MIP-1β) and T. cruzi, induced a significant increase in the production of NO2− in human macrophages after 24 or 42 h. The ability of these CC chemokines to increase NO2− production in uninfected or T. cruzi-infected macrophages varied occasionally in experiments performed by similar methods but with cells from different healthy donors. However, a significant increase in the NO2− concentration was always seen in both uninfected and T. cruzi-infected macrophages in the presence of these chemokines. Furthermore, NO2− production was always higher when macrophages were treated with CC chemokines in combination with T. cruzi than when the macrophages were treated only with these CC chemokines. This supports the notion that treatment of T. cruzi-infected human macrophages with CC chemokines increases NO production by these cells. Furthermore, we have compared the NO2− responses in human macrophages induced by these CC chemokines to those induced by IFN-γ (Table 1). Our results indicate that the amount of NO2− induced by these chemokines (RANTES, MIP-1α, or MIP-1β) in human macrophages is comparable to the amount of NO2− induced by IFN-γ (Table 1).

FIG. 3.

Effects of RANTES, MIP-1α and MIP-1β on the production of NO2− by human macrophages. Macrophage monolayers were incubated with CC chemokines that were or were not exposed to T. cruzi trypomastigotes, and levels of NO2− were evaluated in macrophage culture supernatants at 48 h, as described in Materials and Methods. This is a representative experiment of three performed by the same method, with similar results. Each column represents the mean of triplicate determinations, and each bar represents ± 1 standard deviation. Differences between ∗ and ∗∗, P < 0.05; differences between ∗∗ and ∗∗∗, P < 0.05.

FIG. 4.

Effect of l-NMMA on the production of NO2− by human macrophages treated with CC chemokines. Macrophage monolayers were incubated with CC chemokines and were or were not exposed to T. cruzi trypomastigotes. The levels of NO2− were evaluated in macrophage culture supernatants at 48 h, as described in Materials and Methods. This is a representative experiment of three performed by the same method, with similar results. Each column represents the mean of triplicate determinations, and each bar represents ± 1 standard deviation. Differences between ∗ and ∗∗, P < 0.05; differences between ∗∗ and ∗∗∗, P < 0.05.

TABLE 1.

Production of NO2− by human macrophages, induced by CC chemokines or IFN-γ

| Blood donor | Treatment | Amt (nmol) of NO2−/106 macrophagesa |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | RPMI | 6.3 ± 0.4 |

| RANTES | 49.5 ± 4.6b | |

| IFN-γ (500 U/ml) | 42.9 ± 6.0b | |

| IFN-γ (1,000 U/ml) | 33.0 ± 9.3b | |

| 2 | RPMI | 6.8 ± 0.3 |

| MIP-1α | 42.9 ± 4.6b | |

| IFN-γ (500 U/ml) | 62.7 ± 4.6b | |

| IFN-γ (1,000 U/ml) | 42.9 ± 4.7b | |

| 3 | RPMI | 6.7 ± 0.2 |

| MIP-1β | 29.7 ± 4.7b | |

| IFN-γ (500 U/ml) | 33.5 ± 0.7b | |

| IFN-γ (1,000 U/ml) | 29.2 ± 3.9b |

Mean ± standard deviation of triplicate determinations of NO2− levels produced by macrophages from blood donors after 24 h.

Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) with respect to the control (RPMI).

Killing of T. cruzi trypomastigotes by NO in macrophage cell-free medium is blocked by a NO antagonist or a NO scavenger.

The ability of l-NMMA to completely inhibit CC chemokine-induced macrophage trypanocidal activity and NO2− production by macrophages suggests that NO is necessary for the destruction of T. cruzi trypomastigotes. To obtain direct evidence for this contention, the effect of NO spontaneously released from DEANO, a NO carrier, in PBS (pH 7.4) on the viability of T. cruzi trypomastigotes was determined. When DEANO is dissolved in PBS (pH 7.4), it spontaneously and effectively released NO. NO spontaneously released from DEANO kills 97.5% of trypomastigotes compared to no killing in controls treated with degassed PBS alone (Table 2). Carboxy PTIO, a NO antagonist, which reacts stoichiometrically with NO and inhibits the physiologic effects mediated by NO (35), significantly inhibits trypomastigote killing when NO is spontaneously produced in PBS by DEANO. Hemoglobin, another scavenger of NO (15), inhibits trypomastigote killing. The NO scavengers carboxy PTIO and hemoglobin in PBS do not affect trypomastigote viability (Table 2). The effect of NO is not due to its oxidation product NO2−, because 1 mM NO2− did not affect parasite viability in this in vitro assay (results not shown). Under these in vitro conditions, 200 μM DEANO in PBS induced the production of 199 μM NO2− in 2 min at 37°C, as determined by the Griess reagent; this is equivalent to 199 μM released NO, since NO is oxidized to NO2−. Furthermore, carboxy PTIO or hemoglobin significantly inhibited the production of NO2− in this system (results not shown).

TABLE 2.

Killing of T. cruzi trypomastigotes by NO in cell-free medium is blocked by a NO antagonist or a NO scavengera

| Treatment | Trypomastigote concn (107 cells/ml)b | % Trypomastigote killing |

|---|---|---|

| PBS | 1.12 ± 0.1 | 0.0 |

| PBS + 200 μM DEANO | 0.03 ± 1.1c | 97.5 |

| PBS + 200 μM DEANO + 400 μM Carboxy PTIO | 1.01 ± 0.1 | 9.8 |

| PBS + 200 μM DEANO + 1 mg of hemoglobin per ml | 1.10 ± 0.1 | 1.8 |

| PBS + 400 μM carboxy PTIO | 1.11 ± 0.1 | 0.9 |

| PBS + 1 mg of hemoglobin per ml | 1.13 ± 0.2 | −0.8 |

This is a typical representative experiment of three separate experiments performed by the same method and with similar results.

Values are mean ± standard deviation for triplicate determinations.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from the PBS-incubated trypomastigotes control group as calculated by Student’s t test.

DISCUSSION

This study determined a new role for the CC chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β in macrophage function, i.e., the induction of trypanocidal activity of these cells via NO. Our findings showing that l-NMMA but not its enantiomer completely inhibited CC chemokine-induced macrophage trypanocidal activity, that CC chemokines enhance the production of NO2− by human macrophages, and that killing of T. cruzi trypomastigotes by NO in cell-free medium is blocked by a NO antagonist or a NO scavenger and the significant inhibition of NO2− production by NO scavengers in vitro support the notion that the trypanocidal activity induced by CC chemokines in human macrophages appears to be mediated via NO. The results of the experiments involving T. cruzi killing by NO generated from a NO donor, measured as NO2−, suggest that the concentration of NO equivalents required to kill 106 trypanosomes in vitro is approximately 20 nmol, which is comparable to the concentration present in CC chemokine-treated, T. cruzi-infected macrophage culture supernatants (Fig. 3 and 4) and which may be required to kill the parasite within macrophage monolayers. In two previous reports, the ability of S-nitroso-acetyl-penicillamine (SNAP) to kill T. cruzi was studied (34, 47); however, it was not clear if the toxicity was due to SNAP or the production of NO by SNAP, since toxicity was not blocked by a NO antagonist or a NO scavenger. The cell-free system we used was designed to investigate whether T. cruzi toxicity was due to NO and not to the derivative drug. Our in vitro system (Table 2) shows that indeed NO is responsible for T. cruzi trypomastigote killing.

The levels of NO2− produced in normal human macrophage culture supernatants as indicators of NO in our experiments are comparable to the levels of NO2− produced by normal human macrophages in previous studies by several investigators (12, 19, 24, 26). Furthermore, we found in this study that the levels of NO2− produced by human macrophages exposed to RANTES, MIP-1α, or MIP-1β are comparable to the levels of NO2− induced by IFN-γ, one of the major stimuli for the activation of macrophages, which has been shown to be a key activation factor for the killing of intracellular parasites. The analysis of the production of NO by human macrophages has been controversial (43), since initially the levels of NO produced by human macrophages were compared to the levels of NO produced by rodent macrophages. It became evident as a result of numerous reports that rodent macrophages produce NO at micromolar levels per 106 cells per day; recent reports indicate that human macrophages produce NO at nanomolar levels per 106 cells per day (12, 19, 26, 29). Production of NO by human macrophages has been documented upon stimulation of human macrophages with several agents such as other cytokines (10, 12, 20, 27), endothelin B (19), or CC chemokines (this report). We should point out that in this study we used human macrophages obtained from healthy donors and differentiated from human monocytes for 4 weeks. Whether the human macrophage differentiation time plays a role in NO production remains to be defined.

We also observed that CC chemokines differentially modulate the uptake of T. cruzi trypomastigotes. Our results indicate that the CC chemokine RANTES is more efficient in enhancing the uptake of invasive trypomastigotes by human macrophages than are MIP-1α and MIP-1β at the optimal concentration of 500 ng/ml. Interestingly, analysis of this parameter of macrophage function with cells obtained from several healthy donors appears to suggest that the efficiency of CC chemokine enhancement of T. cruzi uptake by human macrophages at the optimal chemokine concentration would be in the following order: RANTES > MIP-1α > MIP-1β. We previously found that RANTES also appears to induce a stronger trypanocidal effect in human macrophages than MIP-1α or MIP-1β does (24). Our group recently found that RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β act on human macrophages by enhancing the concentration of Ca2+ intermediates, cause tyrosine phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase, and induce the expression of certain macrophage surface molecules (54). It was also recently found that these CC chemokines induce different patterns of protein tyrosine phosphorylation in human macrophages from healthy donors (24).

NO has been shown to inhibit the growth and function of a diverse array of infectious-disease agents including bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and helminths (18). IFN-γ- and/or TNF-α-induced macrophage killing of T. cruzi has been reported to involve NO production (14, 27). This killing is inhibited by l-NMMA (14, 27) and is down regulated by TGF-β and IL-10 (14). The importance of this mechanism has been confirmed by in vivo studies with anti-TNF-α-treated mice, which showed a decreased capacity to kill T. cruzi and produce NO (44). Defective NO effector functions lead to extreme T. cruzi susceptibility in mice deficient in IFN-γ receptor or inducible NOS (17). Moreover, TNF-α- and IFN-γ-activated human macrophages have also been reported to kill T. cruzi via a similar mechanism involving NO (28). NO production by human macrophages has also been demonstrated after infection with live Mycobacterium avium but not gamma-irradiated or subcellular fractions of this organism (12). Furthermore, activation of inducible NOS in human macrophages has been found following direct interaction with microorganisms such as HIV-1 (5), Pneumocystis carinii, and Mycobacterium avium (12). Interestingly, our findings suggest that NO production by human macrophages occurs via direct stimulation with the CC chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β or when these chemokines are applied in combination with T. cruzi.

We show in this paper that the chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β induce the microbicidal capacity of human macrophages to kill the intracellular parasite T. cruzi, which normally multiplies within these cells via NO. Inflammatory cells including macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils, and T cells are present in chagasic lesions and have been postulated to play important roles in T. cruzi clearance (32, 48–51). Our results suggest that CC chemokines may stimulate the microbicidal capacity of macrophages present in inflammatory lesions in individuals infected with Chagas’ disease. Interestingly, a recent study has found high levels of expression of MIP-1α in cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions containing macrophages and different T-cell subsets (38). Our results suggest that the CC chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β may play a beneficial role in individuals infected with T. cruzi.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants AI 27767, G12 RR03032, HL03149, and 2S06GM08037 and by National Science Foundation grant HRD 9255157.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder C C, Feng Y, Kennedy P E, Murphy P M, Berger E A. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Human chemokines: an update. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:675–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baggiolini M B, Dewald B, Moser B. Interleukin-8 and related C chemotactic cytokines-CXC and CC-chemokines. Adv Immunol. 1994;55:97–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brener Z. Biology of Trypanosoma cruzi. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1973;27:347–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.27.100173.002023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukrinsky M I, Nottet H S L, Scmidtmayerova H, Dubrovsky L, Flanagan C R, Mullins M E, Lipton S A, Gendelman H E. Regulation of nitric oxide synthase activity in human immunodeficiency virus type (HIV-1)-infected monocytes: implications for HIV-associated neurological disease. J Exp Med. 1995;181:735–745. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cocchi F, DeVico A, Garzino-Demo A, Arya S K, Gallo R C, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1α and MIP-1β as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270:1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen M C, Cohen S. Cytokine function. A study in biologic diversity. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;105:589–598. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/105.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook D N. The role of MIP-1α in inflammation and hematopoiesis. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:61–66. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Castillo M. AIDS and Chagas’ disease with central nervous system tumor-like lesion. Am J Med. 1990;88:693–694. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90544-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denis M. Tumor necrosis factor and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor stimulate human macrophages to restrict growth of virulent Mycobacterium avium and to kill avirulent M. avium: killing effector mechanism depends on the generation of reactive nitrogen intermediates. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;49:380–387. doi: 10.1002/jlb.49.4.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixit V M, Greem S, Sarma V, Holzman L, Wolf F W, O’Rourke K, Ward P A, Prochwnik E V, Marks R M. Tumor necrosis factor alpha: induction of novel gene products in human endothelial cells including a macrophage-specific chemokine. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2973–2978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumarey C H, Labrousse V, Rastogi N, Vargatig B B, Bachelet M. Selective Mycobacterium avium-induced production of nitric oxide by human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:36–40. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao J L, Murphy P M. Human cytomegalovirus open reading frame US28 encodes a functional beta chemokine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28539–28542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gazzinelli R T, Oswald I P, Hieny S, James S L, Sher A. The microbicidal activity of interferon-gamma-treated macrophages against Trypanosoma cruzi involves an l-arginine-dependent, nitrogen oxide-mediated mechanisms inhibitable by interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor beta. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2501–2506. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green S J, Nacy C A, Meltzer M S. Cytokine-induced synthesis of nitrogen oxides in macrophages: a protective host response to Leishmania and other intracellular pathogens. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;50:93–103. doi: 10.1002/jlb.50.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedrick J A, Zlotnik A. Identification and characterization of a novel β-chemokine containing six conserved cysteins. J Immunol. 1997;159:1589–1593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holscher C, Kohler G, Muller U, Mossman H, Schaub G U, Brombacher F. Defective nitric oxide effect or functions lead to extreme susceptibility of Trypanosoma cruzi-infected mice deficient in gamma interferon receptor or inducible nitric oxide synthase. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1208–1215. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1208-1215.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James S L. Role of nitric oxide in parasitic infections. Microbiol Rev. 1995;50:533–547. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.533-547.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King J M, Srivastava K D, Stefano G B, Bilfinger T V, Bahou W F, Magazine H L. Human monocyte adhesion is modulated by endothelin B receptor-coupled nitric oxide release. J Immunol. 1997;158:880–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolb J P, Paul-Eugene N, Damias C, Yamaoka K, Drapier J C. Interleukin-4 stimulates cGMP production by INFN-γ-activated human macrophages. Involvement of the nitric oxide synthase pathway. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9811–9816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy J A, Marckewicz C E, Barker E. Controlling HIV pathogenesis: the role of the noncytotoxic anti-HIV response of CD8+ cells. Immunol Today. 1996;17:217–224. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lima M F, Villalta F. Host-cell attachment by Trypanosoma cruzi: identification of an adhesion molecule. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;188:256–262. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lima M F, Villalta F. Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigote clones differentially express a cell adhesion molecule. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;33:159–170. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lima M F, Zhang Y, Villalta F. β-chemokines that inhibit HIV-1 infection of human macrophages stimulate uptake and promote destruction of Trypanosoma cruzi by human macrophages. Cell Mol Biol. 1997;43:1067–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maragos C M, Morley D, Wink D A, Dunams T M, Saavedra J E, Hoffman A, Bove A A, Isaac L, Hrabie J A, Keefer L K. Complexes of NO with nucleophiles as agents for the controlled biological release of nitric oxide. Vasorelaxant effects. J Med Chem. 1991;34:3242–3247. doi: 10.1021/jm00115a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin J H, Edwards S W. Changes in mechanisms of monocyte/macrophage-mediated cytotoxicity during culture. Reactive oxygen intermediates are involved in monocyte-mediated cytotoxicity, whereas nitrogen intermediates are employed by macrophages in tumor killing. J Immunol. 1993;150:3478–3486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munoz-Fernandez M A, Fernandez M A, Fresno M. Synergism between tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma on macrophage activation for the killing of intracellular Trypanosoma cruzi through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:301–307. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munoz-Fernandez M A, Fernandez M A, Fresno M. Activation of human macrophages for the killing of intracellular Trypanosoma cruzi by TNF-α and IFN-γ through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Immunol Lett. 1992;33:35–40. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(92)90090-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray H W, Teitelbaum R F. l-Arginine-dependent reactive nitrogen intermediates and the antimicrobial effect of activated human mononuclear phagocytes. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:513–517. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Council News. 1996;5:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neote K, DiGregorio D, Mak J Y, Horuk R, Schall T J. Molecular cloning, functional expression, and signaling characteristics of a C-C chemokine receptor. Cell. 1993;72:415–425. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90118-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noisin E L, Villalta F. Fibronectin increases Trypanosoma cruzi amastigote binding and uptake by murine and human macrophages. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1030–1034. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1030-1034.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olivares-Fontt E, Vray B. Relationship between granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and Trypanosoma cruzi infection of murine macrophages. Parasite Immunol. 1995;17:135–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1995.tb01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petray P, Castanos-Velez M, Grinstein S, Orn A, Rottenberg M E. Role of nitric oxide in resistance and histopathology during experimental infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. Immunol Lett. 1995;47:121–126. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(95)00083-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pietraforte D, Mallozzi C, Scorza G, Minetti M. Role of thiols in the targeting of s-nitroso thiols to red blood cells. Biochemistry. 1995;34:7177–7185. doi: 10.1021/bi00021a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prata F, Wietzerbin J, Pons F G, Falcoff E, Eisen H. Synergistic protection by specific antibodies and interferon against infection by Trypanosoma cruzi in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 1984;14:930–933. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830141013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reed S G, Nathan C F, Phil D L, Rodricks P, Shanebeck K, Conlon P J, Grabstein K H. Recombinant granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor activates macrophages to inhibit Trypanosoma cruzi and release hydrogen peroxide: comparison with interferon gamma. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1734–1746. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.6.1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ritter U, Moll H, Laskay T, Brocker E, Velasco O, Becker I, Gillitzer R. Differential expression of chemokines in patients with localized and diffuse cutaneous American leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:699–709. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosemberg S, Chaves C J, Higuchi M L, Lopes M B, Castro L H, Machado L R. Fatal meningoencephalitis caused by reactivation of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in a patient with AIDS. Neurology. 1992;42:640–642. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schall T J. Biology of the RANTES/sis cytokine family. Cytokine. 1991;3:165–183. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(91)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schall T J, Bacon K, Camp R D D, Kaspari J W, Goeddel D V. Human macrophage inflammatory protein α (MIP-1α) and MIP-1β chemokines attract distinct populations of lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1993;177:821–826. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schall T J, Bacon K B. Chemokines, leukocyte trafficking and inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:865–873. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneemann M, Schoedom G, Hofer S, Blau N, Guerrero L, Schaffner A. Nitric oxide synthase is not a constituent of the antimicrobial armature of human mononuclear phagocytes. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1358–1363. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.6.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silva J S, Vespa G N, Cardoso M A, Aliberti J C, Cunha I Q. Tumor necrosis factor alpha mediated resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice by inducing nitric oxide production in interferon-activated macrophages. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4862–4867. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4862-4867.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taub D D, Sayers T J, Carter C R, Ortaldo J R. Alpha and beta chemokines induce NK cell migration and enhance NK-mediated cytolysis. J Immunol. 1995;155:3877–3888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vaddi K, Keller M, Newton R C. The chemokine facts book. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1997. pp. 21–141. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vespa G N R, Cunha F Q, Silva J S. Nitric oxide is involved in control of Trypanosoma cruzi-induced parasitemia and directly kills the parasite in vitro. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5177–5182. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5177-5182.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Villalta F, Kierszenbaum F. Role of polymorphonuclear cells in Chagas’ disease. I. Uptake and mechanisms of destruction of intracellular (amastigote) forms of Trypanosoma cruzi by human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1983;131:1504–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Villalta F, Kierszenbaum F. Role of inflammatory cells in Chagas’ disease. I. Uptake and mechanisms of destruction of intracellular (amastigote) forms of Trypanosoma cruzi by human eosinophils. J Immunol. 1984;132:2053–2058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Villalta F, Kierszenbaum F. Role of inflammatory cells in Chagas’ disease. II. Interactions of mouse macrophages and human monocytes with intracellular forms of Trypanosoma cruzi: uptake and mechanisms of destruction. J Immunol. 1984;133:3338–3343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villalta F, Kierszenbaum F. Effects of human colony-stimulating factor on the uptake and destruction of a pathogenic parasite (Trypanosoma cruzi) by human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1986;135:1703–1707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Villalta F, Lima M F, Howard S H, Zhou L, Ruiz-Ruano A. Purification of a Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigote 60-kilodalton surface glycoprotein that primes and activates murine lymphocytes. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3025–3032. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3025-3032.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Villalta F, Ruiz-Ruano A, Valentine A A, Lima M F. Purification of a 74 kDa surface glycoprotein from heart myoblasts that inhibits binding and entry of Trypanosoma cruzi into heart cells. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61:217–230. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Villalta, F., Y. Zhang, F. M. Hatcher, E. Motley, and M. F. Lima. Unpublished data.