Key Points

Question

Can ensitrelvir, an oral SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease inhibitor, shorten the duration of symptoms in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 irrespective of the presence of risk factors for severe disease?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 1821 patients with mild to moderate COVID-19, among 1030 patients randomized in less than 72 hours of disease onset, a statistically significant difference was observed in the time to resolution of 5 COVID-19 symptoms between those who received ensitrelvir, 125 mg, and those who received placebo.

Meaning

Treatment with 125 mg of ensitrelvir shortened time to resolution of key COVID-19 symptoms.

This randomized clinical trial assesses whether ensitrelvir reduces time to resolution of 5 common COVID-19 symptoms among patients with mild to moderate disease in less than 72 hours of disease onset.

Abstract

Importance

Treatment options for COVID-19 are warranted irrespective of the presence of risk factors for severe disease.

Objective

To assess the efficacy and safety of ensitrelvir in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This phase 3 part of a phase 2/3, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial was conducted from February 10 to July 10, 2022, with a 28-day follow-up period, at 92 institutions in Japan, Vietnam, and South Korea. Patients (aged 12 to <70 years) with mild to moderate COVID-19 within 120 hours of positive viral test results were studied.

Interventions

Patients were randomized (1:1:1) to receive 125 mg of once-daily ensitrelvir (375 mg on day 1), 250 mg of once-daily ensitrelvir (750 mg on day 1), or placebo for 5 days.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was the time to resolution of the composite of 5 characteristic symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron infection, assessed using a Peto-Prentice generalized Wilcoxon test stratified by vaccination history. Virologic efficacy and safety were also assessed.

Results

A total of 1821 patients were randomized, of whom 1030 (347 in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group, 340 in the 250-mg ensitrelvir group, and 343 in the placebo group) were randomized in less than 72 hours of disease onset (primary analysis population). The mean (SD) age in this population was 35.2 (12.3) years, and 552 (53.6%) were men. A significant difference was observed between the 125-mg ensitrelvir group and the placebo group (P = .04 with a Peto-Prentice generalized Wilcoxon test). The difference in median time was approximately 1 day between the 125-mg ensitrelvir group and the placebo group (167.9 vs 192.2 hours; difference, −24.3 hours; 95% CI, −78.7 to 11.7 hours). Adverse events were observed in 267 of 604 patients (44.2%) in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group, 321 of 599 patients (53.6%) in the 250-mg ensitrelvir group, and 150 of 605 patients (24.8%) in the placebo group, which included a decrease in high-density lipoprotein level (188 [31.1%] in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group, 231 [38.6%] in the 250-mg ensitrelvir group, and 23 [3.8%] in the placebo group). No treatment-related serious adverse events were reported.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial, 125-mg ensitrelvir treatment reduced the time to resolution of the 5 typical COVID-19 symptoms compared with placebo in patients treated in less than 72 hours of disease onset; the absolute difference in median time to resolution was approximately 1 day. Ensitrelvir demonstrated clinical and antiviral efficacy without new safety concerns. Generalizability to populations outside Asia should be confirmed.

Trial Registration

Japan Registry of Clinical Trials Identifier: jRCT2031210350

Introduction

COVID-19 rapidly spread worldwide, and in November 2021, the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant was declared a variant of concern.1 Patients infected with the Omicron variant generally experience mild symptoms2,3,4 but may have more absences from work.5 Despite the global administration of vaccinations, there has been emergence of Omicron BA.5*, XBB*, and BQ.1* sublineages, which can evade host immunity.6,7

Several antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2 infection are available worldwide, such as remdesivir,8 molnupiravir,9 and ritonavir-boosted nirmatrelvir.10 However, the clinical trials of these drugs were conducted in high-risk, unvaccinated patients and when the Delta or pre-Delta variant was dominant. Moreover, in vitro studies11,12,13 suggest that most therapeutic monoclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 are less efficacious against Omicron subvariants vs previous variants. Novel treatment options that can be used irrespective of the presence of risk factors for severe disease are warranted.

Ensitrelvir fumaric acid is an oral SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease inhibitor that has shown antiviral effects against multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, including Omicron subvariants, in in vitro and in vivo studies.14,15,16,17,18 As of September 2023, ensitrelvir (125-mg tablets) obtained emergency use approval in Japan and has been under Fast Track review by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). A seamless phase 2/3, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial is currently underway (Japan Registry of Clinical Trials identifier: jRCT2031210350). Ensitrelvir treatment demonstrated decreased viral load vs placebo in phases 2a and 2b19,20 and showed improvements in 4 respiratory symptoms (stuffy or runny nose, sore throat, shortness of breath, and cough) and the composite of the 4 respiratory symptoms and feverishness in phase 2b.20 The SCORPIO-SR trial, phase 3 of the phase 2/3 trial, assessed the efficacy and safety of ensitrelvir in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19.

Methods

Study Design

This randomized clinical trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki,21 Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and other applicable laws and regulations. The trial protocol (Supplement 1) was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions (the eAppendix in Supplement 2 gives a list of investigators). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legally acceptable representatives. This report followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

This trial was conducted from February 10 to July 10, 2022, across 92 institutions in Japan (65 sites), Vietnam (2 sites), and South Korea (25 sites). Patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 were randomized (1:1:1) to receive ensitrelvir, 125 mg; ensitrelvir, 250 mg; or placebo and were followed up until day 28.22 Considering that the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis in phase 2b of the trial did not show a difference in antiviral efficacy between the 2 ensitrelvir dose groups, the 125-mg group was chosen as the efficacy analysis population. Analyses between the 250-mg ensitrelvir and placebo groups were performed as a secondary comparison.22

The phase 2/3 study used a seamless design to maximize patient recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the current phase 3 trial was initiated with continuous patient enrollment after phase 2b. The phase 3 protocol (Supplement 1) was amended based on the phase 2b data and in view of the changes in clinical features of the pandemic when Omicron subvariants were dominant. All protocol amendments, including the changes in the primary end point, analysis populations, statistical tests, and sample size estimation, were made blinded to the phase 3 data and were finalized based on consultations with infectious disease experts and regulatory authorities.22

Patients

Eligible patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 were those aged 12 years to younger than 70 years who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 within 120 hours prior to randomization. Patients should have had a time of 120 hours or less from the onset of COVID-19 symptoms to randomization and at least 1 moderate or severe symptom or worsening of an existing moderate or severe symptom among the 12 COVID-19 symptoms defined based on FDA guidance.23 Key exclusion criteria included an awake oxygen saturation of 93% or less (room air), supplemental oxygen requirement, anticipated COVID-19 exacerbation within 48 hours of randomization, suspected active and systemic infections other than COVID-19 requiring treatment, current or long-term history of moderate or severe liver disease, known hepatic or biliary abnormalities (except for Gilbert syndrome or asymptomatic gallstones), and moderate to severe kidney disease (eMethods in Supplement 2). Patient characteristic data, including age and self-reported race and ethnicity, were collected as part of the baseline examination. Because phase 1 of the study suggested a small difference in ensitrelvir pharmacokinetics between Japanese and White healthy volunteers, we collected race and ethnicity data in this study. Ethnicity was categorized as Hispanic or Latino, non-Hispanic or Latino, not reported, or unknown. Race was categorized as American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, White, or other (no other information was available regarding other race).

Randomization, Blinding, and Treatment

Patient randomization was performed using an interactive response technology system and stratification by the time from onset of COVID-19 to randomization (<72 vs ≥72 hours) and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination history (at least 1 dose of vaccination: yes vs no). All patients and study staff were blinded to the treatment, and emergency unblinding per the investigator’s request was allowed in case of occurrence of adverse events to determine the appropriate therapy for the patient. Patients received ensitrelvir (375 mg on day 1 and 125 mg on days 2-5 [125-mg ensitrelvir group] or 750 mg on day 1 and 250 mg on days 2-5 [250-mg ensitrelvir group]) or matching placebo tablets, which were identical in appearance and packaging, without dose modification. Treatment was discontinued in case of COVID-19 exacerbation, serious or intolerable adverse events, and pregnancy (eMethods in Supplement 2).

End Points

The primary end point was the time to resolution of the composite of 5 COVID-19 symptoms (stuffy or runny nose, sore throat, cough, feeling hot or feverish, and low energy or tiredness) on the basis that they were the most commonly observed symptoms in the phase 2b study of the current phase 2/3 study that was conducted when the Omicron BA.1 variant was predominant.22 Key secondary end points were the change from baseline in SARS-CoV-2 RNA level on day 4 (key secondary end point 1) and time to first negative SARS-CoV-2 titer (key secondary end point 2). The time to resolution of 12 COVID-19 symptoms (the abovementioned 5 symptoms plus shortness of breath, muscle or body aches, headache, chills or shivering, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea), 14 COVID-19 symptoms (the abovementioned 12 symptoms plus anosmia and dysgeusia), and SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels and titers up to day 21 were assessed as other secondary end points. Resolution of 5, 12, and 14 COVID-19 symptoms was achieved when all the symptoms disappeared, improved, or were maintained after first administration of study intervention and symptom resolution was sustained for at least 24 hours in a patient. Each of the 12 COVID-19 symptoms was rated on a 4-point scale (with 0 indicating none; 1, mild; 2, moderate; and 3, severe), whereas anosmia and dysgeusia were rated on a 3-point scale (with 0 indicating same as usual; 1, less than usual; and 2, no sense of smell or taste) by the patient (eMethods in Supplement 2). The safety end point was the incidence of adverse events that emerged after treatment initiation.

Assessments

The severity of each COVID-19 symptom was recorded in a diary twice daily (morning and evening) until day 9 and once daily (evening) from days 10 to 21. SARS-CoV-2 titers and RNA levels were quantified using nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected on days 1 (before drug administration), 2 to 6 (days 3 and 5 as optional visits), and 9, 14, and 21 (or study discontinuation). Adverse events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 24.0 (eMethods in Supplement 2).

Statistical Analysis

Considering the main pathophysiology of COVID-19 (viral proliferation for several days followed by inflammatory reaction by the host immune system starting around 7 days after onset), antiviral treatment is expected to be most effective when initiated in the early phase of infection.22 On the basis of an epidemiologic analysis24 in Japan, 62% of patients with COVID-19 hospitalized during the Omicron BA.5 phase of the pandemic experienced disease progression within 3 days of onset. To evaluate the antiviral and clinical efficacy of ensitrelvir in the optimal patient population, the primary analysis population for the primary and key secondary end points was defined as patients randomized in less than 72 hours of disease onset in the intention-to-treat population (all patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA at baseline).22 The modified intention-to-treat population comprised all patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA and had a detectable SARS-CoV-2 titer at baseline. As reported previously,22 assuming a Weibull distribution in the time to resolution of the 5 COVID-19 symptoms, 230 patients per group were required to compare the survival distributions of the primary end point between the 125-mg ensitrelvir and placebo groups using the Peto-Prentice generalized Wilcoxon test, with 80% power and a 2-sided significance level of 0.05. Assuming a 10% dropout rate before enrollment, the final sample size for the primary analysis population was set to 260 patients per group (780 patients in total).22 Of note, patient enrollment was continued as originally planned to include 595 patients randomized within 120 hours of disease onset each in the 125-mg ensitrelvir, 250-mg ensitrelvir, and placebo groups.

The statistical significance of ensitrelvir vs placebo for the primary end point in the primary analysis population was tested using a Peto-Prentice generalized Wilcoxon test stratified by SARS-CoV-2 vaccination history (yes or no).25 A fixed-sequence hierarchical testing procedure was applied to control type I errors. The test was performed in the order of primary end point, key secondary end point 1, and key secondary end point 2 in the primary analysis population. The tests were repeated in the same order in patients randomized within 120 hours of disease onset until findings were no longer statistically significant (2-sided significance level of P ≥ .05).22 All statistical comparisons were performed at a 2-sided significance level of P < .05. No imputation was performed for missing data. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) (eMethods in Supplement 2).

Results

Patients

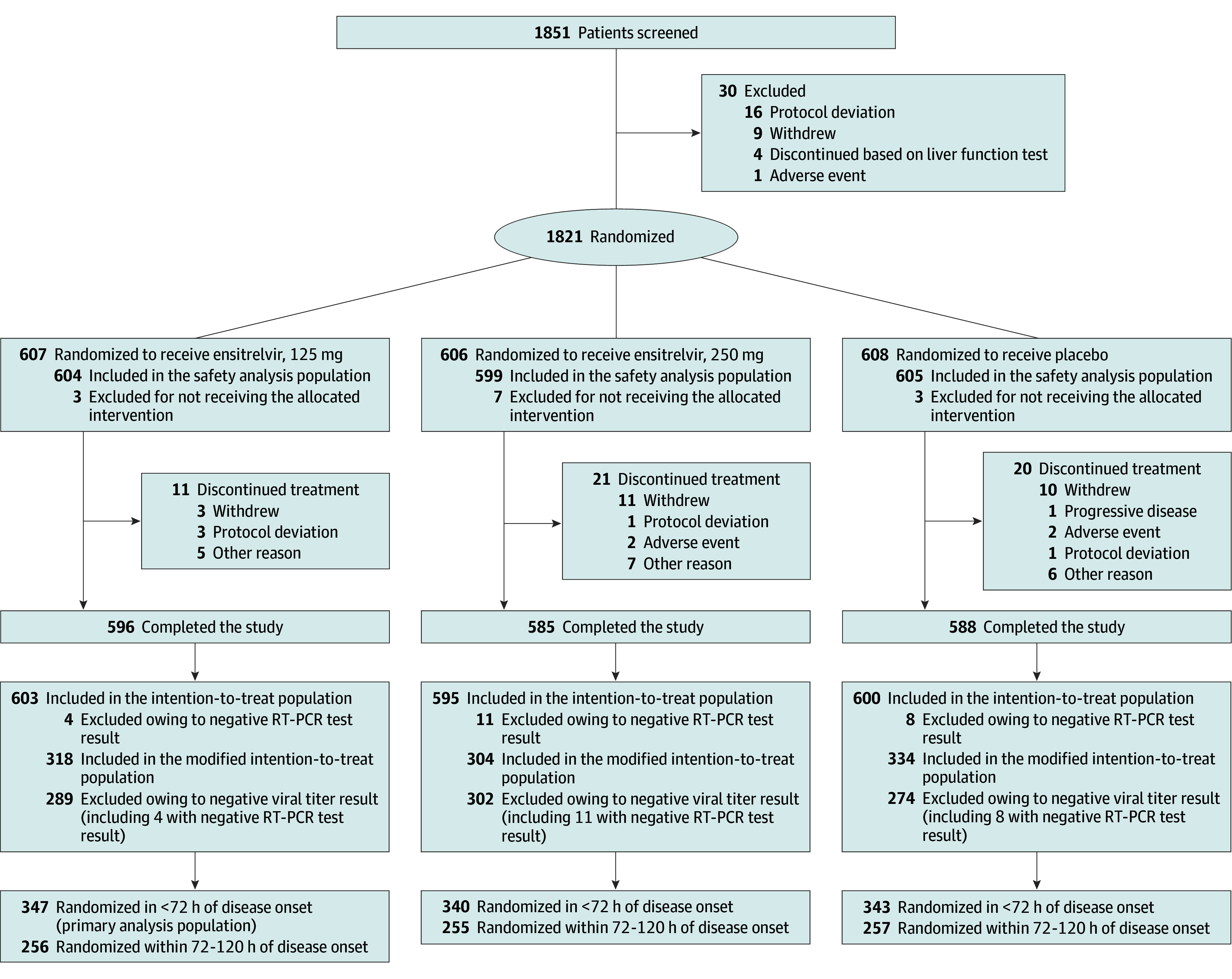

Among 1821 patients enrolled, 607 were randomized to receive 125 mg of ensitrelvir, 606 to receive 250 mg of ensitrelvir, and 608 to receive placebo (Figure 1). Of these patients, 1769 (97.1%) completed the study and 1030 (56.6%) were randomized in less than 72 hours of disease onset (primary analysis population). Patient characteristics were similar across the groups (Table 1 and eTable 1 in Supplement 2) and were largely representative of the expected patient population (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

The intention-to-treat population comprised all patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA at baseline, as confirmed by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing of a nasopharyngeal swab sample. The modified intention-to-treat population comprised all patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA and who had a detectable SARS-CoV-2 titer at baseline.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline in the Intention-to-Treat Populationa.

| Characteristic | Patients randomized <72 h after disease onset | Patients randomized within 120 h of disease onset | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ensitrelvir, 125 mg (n = 347)b | Ensitrelvir, 250 mg (n = 340) | Placebo (n = 343) | Total (n = 1030) | Ensitrelvir, 125 mg (n = 603) | Ensitrelvir, 250 mg (n = 595) | Placebo (n = 600) | Total (n = 1798) | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 154 (44.4) | 155 (45.6) | 169 (49.3) | 478 (46.4) | 285 (47.3) | 272 (45.7) | 289 (48.2) | 846 (47.1) |

| Male | 193 (55.6) | 185 (54.4) | 174 (50.7) | 552 (53.6) | 318 (52.7) | 323 (54.3) | 311 (51.8) | 952 (52.9) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 35.7 (12.5) | 35.3 (12.2) | 34.7 (12.2) | 35.2 (12.3) | 35.9 (12.7) | 35.9 (12.7) | 35.3 (12.6) | 35.7 (12.6) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 303 (87.3) | 299 (87.9) | 304 (88.6) | 906 (88.0) | 539 (89.4) | 538 (90.4) | 550 (91.7) | 1627 (90.5) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (0.9) | 4 (1.2) | 2 (0.6) | 9 (0.9) | 5 (0.8) | 4 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) | 11 (0.6) |

| Not reported | 24 (6.9) | 28 (8.2) | 22 (6.4) | 74 (7.2) | 34 (5.6) | 39 (6.6) | 30 (5.0) | 103 (5.7) |

| Unknown | 17 (4.9) | 9 (2.6) | 15 (4.4) | 41 (4.0) | 25 (4.1) | 14 (2.4) | 18 (3.0) | 57 (3.2) |

| Race | ||||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 345 (99.4) | 338 (99.4) | 341 (99.4) | 1024 (99.4) | 601 (99.7) | 593 (99.7) | 598 (99.7) | 1792 (99.7) |

| Black or African American | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| White | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Otherc | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 4 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) |

| COVID-19 vaccinations, No. | ||||||||

| ≥1 | 322 (92.8) | 313 (92.1) | 315 (91.8) | 950 (92.2) | 562 (93.2) | 551 (92.6) | 553 (92.2) | 1666 (92.7) |

| ≥2 | 316 (91.1) | 311 (91.5) | 310 (90.4) | 937 (91.0) | 554 (91.9) | 547 (91.9) | 545 (90.8) | 1646 (91.5) |

| ≥3 | 183 (52.7) | 185 (54.4) | 177 (51.6) | 545 (52.9) | 284 (47.1) | 295 (49.6) | 283 (47.2) | 862 (47.9) |

| SARS-CoV-2 RNA level, mean (SD), log10 copies/mLd | 6.98 (1.01) | 6.89 (1.01) | 6.93 (0.99) | 6.93 (1.00) | 6.83 (1.05) | 6.73 (1.08) | 6.77 (1.07) | 6.77 (1.07) |

| Any risk factor for severe diseasee | 107 (30.8) | 90 (26.5) | 89 (25.9) | 286 (27.8) | 174 (28.9) | 167 (28.1) | 152 (25.3) | 493 (27.4) |

| Prior acetaminophen use | 108 (31.1) | 90 (26.5) | 99 (28.9) | 297 (28.8) | 216 (35.8) | 191 (32.1) | 207 (34.5) | 614 (34.1) |

| Oxygen saturation, mean (SD), %f | 97.3 (1.1) | 97.2 (2.0) | 97.3 (1.2) | 97.3 (1.5) | 97.4 (1.1) | 97.3 (1.6) | 97.3 (1.1) | 97.3 (1.3) |

| SARS-CoV-2 variant | ||||||||

| BA.1/21K (Omicron) | 61 (17.6) | 57 (16.8) | 54 (15.7) | 172 (16.7) | 131 (21.7) | 130 (21.8) | 115 (19.2) | 376 (20.9) |

| BA.2/21L (Omicron) | 242 (69.7) | 232 (68.2) | 241 (70.3) | 715 (69.4) | 401 (66.5) | 376 (63.2) | 407 (67.8) | 1184 (65.9) |

| BA.1.1.529/21M (Omicron) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 4 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | 5 (0.3) |

| BA.4/22A (Omicron) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 2 (0.1) |

| BA.5/22B (Omicron) | 4 (1.2) | 5 (1.5) | 5 (1.5) | 14 (1.4) | 5 (0.8) | 7 (1.2) | 8 (1.3) | 20 (1.1) |

| BA.2.12.1/22C (Omicron) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 8 (0.4) |

| Recombinant | 30 (8.6) | 38 (11.2) | 33 (9.6) | 101 (9.8) | 52 (8.6) | 64 (10.8) | 50 (8.3) | 166 (9.2) |

| Not tested | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.5) | 7 (0.4) |

| No result | 4 (1.2) | 4 (1.2) | 6 (1.7) | 14 (1.4) | 8 (1.3) | 9 (1.5) | 13 (2.2) | 30 (1.7) |

| COVID-19 symptomsg | ||||||||

| Respiratory symptoms | ||||||||

| Stuffy or runny nose | 283 (83.5) | 248 (74.3) | 247 (75.8) | 778 (75.5) | 506 (86.1) | 468 (80.6) | 464 (80.0) | 1438 (80.0) |

| Sore throat | 300 (88.5) | 292 (87.4) | 286 (87.7) | 878 (85.2) | 520 (88.4) | 522 (89.7) | 512 (88.3) | 1554 (86.4) |

| Shortness of breath | 95 (28.0) | 90 (26.9) | 66 (20.2) | 251 (24.4) | 170 (28.9) | 158 (27.1) | 142 (24.5) | 470 (26.1) |

| Cough | 291 (85.8) | 280 (83.8) | 287 (88.0) | 858 (83.3) | 518 (88.1) | 512 (88.0) | 518 (89.3) | 1548 (86.1) |

| Systemic symptoms | ||||||||

| Low energy or tiredness | 265 (78.2) | 248 (74.3) | 229 (70.2) | 742 (72.0) | 446 (75.9) | 407 (69.9) | 408 (70.3) | 1261 (70.1) |

| Muscle or body aches | 207 (61.1) | 209 (62.6) | 189 (58.0) | 605 (58.7) | 341 (58.0) | 333 (57.2) | 315 (54.3) | 989 (55.0) |

| Headache | 219 (64.6) | 221 (66.2) | 213 (65.3) | 653 (63.4) | 376 (63.9) | 368 (63.2) | 367 (63.3) | 1111 (61.8) |

| Chills or shivering | 223 (65.8) | 172 (51.5) | 167 (51.2) | 562 (54.6) | 325 (55.3) | 276 (47.4) | 289 (49.8) | 890 (49.5) |

| Feeling hot or feverish | 247 (72.9) | 234 (70.1) | 235 (72.1) | 716 (69.5) | 378 (64.3) | 379 (65.1) | 385 (66.4) | 1142 (63.5) |

| Digestive symptoms | ||||||||

| Nausea | 49 (14.5) | 38 (11.4) | 37 (11.3) | 124 (12.0) | 81 (13.8) | 75 (12.9) | 76 (13.1) | 232 (12.9) |

| Vomiting | 18 (5.3) | 14 (4.2) | 12 (3.7) | 44 (4.3) | 33 (5.6) | 24 (4.1) | 24 (4.1) | 81 (4.5) |

| Diarrhea | 57 (16.8) | 49 (14.7) | 51 (15.6) | 157 (15.2) | 116 (19.7) | 104 (17.9) | 104 (17.9) | 324 (18.0) |

| Sensation disturbance | ||||||||

| Anosmia | 47 (13.9) | 54 (16.2) | 38 (11.7) | 139 (13.5) | 102 (17.3) | 102 (17.5) | 93 (16.0) | 297 (16.5) |

| Dysgeusia | 52 (15.3) | 50 (15.0) | 49 (15.0) | 151 (14.7) | 105 (17.9) | 91 (15.6) | 99 (17.1) | 295 (16.4) |

Data for all patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA at baseline are shown. Data are given as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Primary analysis population.

There was no information regarding other race.

Sample sizes were 345 for the ensitrelvir, 125 mg, group, 336 for the ensitrelvir, 250 mg, group, and 341 for the placebo group among patients randomized in less than 72 hours of disease onset. Sample sizes were 600 for the ensitrelvir, 125 mg, group, 589 for the ensitrelvir, 250 mg, group, and 597 for the placebo group in patients randomized within 120 hours of disease onset.

Age 65 years or older, body mass index of 30 or greater (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), cancer, cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic lung disease, chronic liver disease, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, disabilities, heart conditions, hypertension, dyslipidemia, HIV infection, mental health disorders, neurologic conditions, primary immunodeficiencies, smoking, solid organ or hematopoietic cell transplant, tuberculosis, and use of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive medications were considered risk factors for severe disease.

Sample sizes were 335 for the ensitrelvir, 125 mg, group, 327 for the ensitrelvir, 250 mg, group, and 322 for the placebo group among patients randomized in less than 72 hours of disease onset. Samples sizes were 584 for the ensitrelvir, 125 mg, group, 573 for the ensitrelvir, 250 mg, group, and 574 for the placebo group among patients randomized within 120 hours of disease onset.

Sample sizes were 339 for the ensitrelvir, 125 mg, group, 334 for the ensitrelvir, 250 mg, group, and 326 for the placebo group among patients randomized in less than 72 hours of disease onset. Sample sizes were 588 for the ensitrelvir, 125 mg, group, 582 (581 for stuffy or runny nose) for the ensitrelvir, 250 mg, group, and 580 for the placebo group among patients randomized within 120 hours of disease onset.

Among 1030 patients in the primary analysis population, the mean (SD) age was 35.2 years; 552 (53.6%) were men, and 478 (46.4%) were women. A total of 347 were in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group, 340 in the 250-mg ensitrelvir group, and 343 in the placebo group. Regarding race, 1024 (99.4%) were Asian; 1 (0.1%), Black or African American; 1 (0.1%), Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; and 4 (0.4%), other race. Regarding ethnicity, 9 (0.9%) were Hispanic or Latino, and 906 (88.0%) were not Hispanic or Latino; 74 (7.2%) did not report ethnicity, and 41 (4.0%) had unknown ethnicity. The majority (937 [91.0]%) of patients had received 2 or more doses of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Prior acetaminophen use was recorded for 297 patients (28.8%). Most patients were infected with the Omicron BA.1 (172 [16.7%]) or BA.2 (715 [69.4%]) subvariant. The most common COVID-19 symptoms across treatment groups were stuffy or runny nose, sore throat, cough, feeling hot or feverish, and low energy or tiredness (Table 1). A total of 744 patients (72.2%) did not have risk factors for severe disease (Table 1 and eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

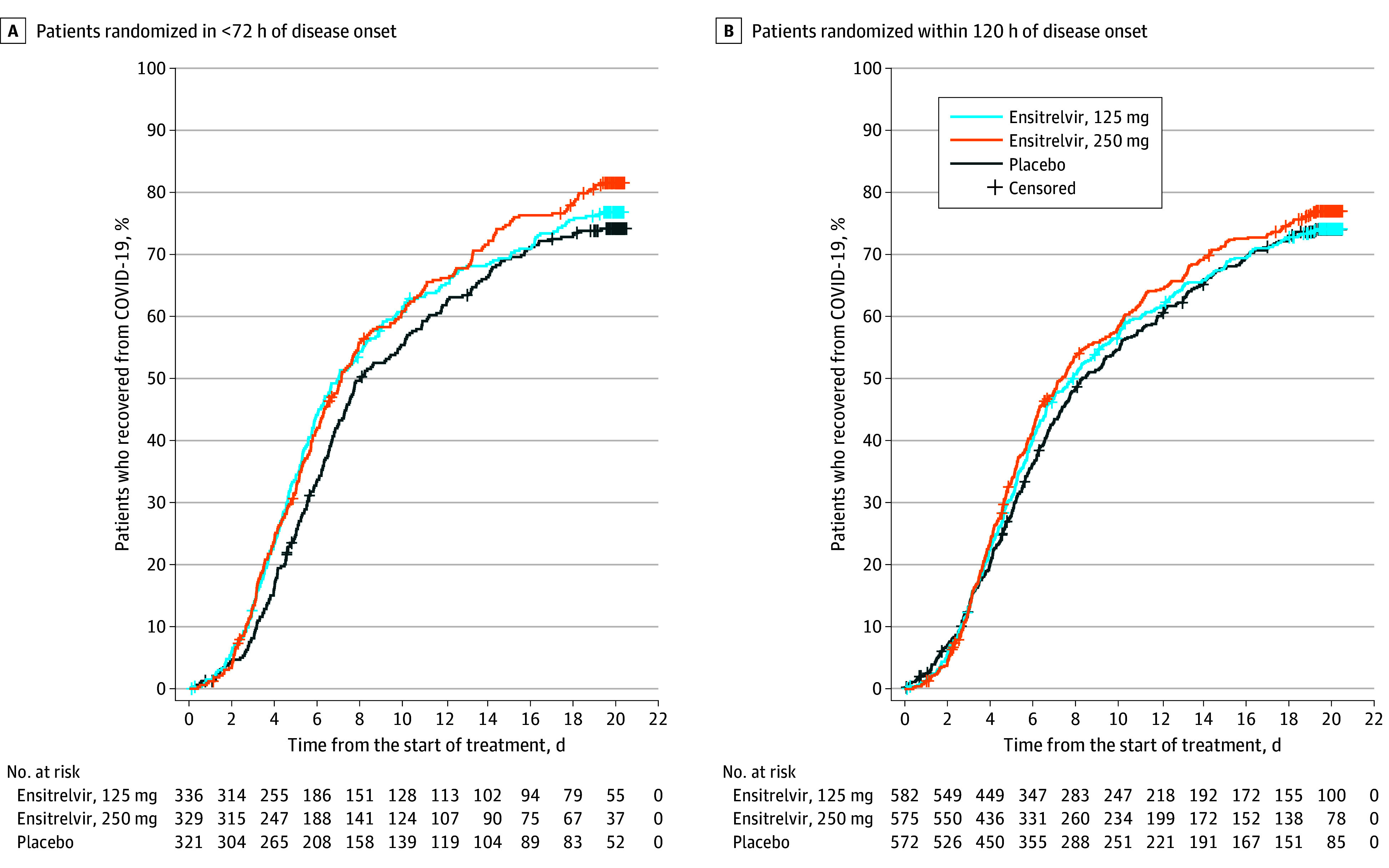

Primary End Point

A significant difference in the time to resolution of the 5 COVID-19 symptoms was observed between the 125-mg ensitrelvir and placebo groups in the primary analysis population (P = .04 with a Peto-Prentice generalized Wilcoxon test) (Figure 2A). The median time to symptom resolution was 167.9 hours (95% CI, 145.0-197.6 hours) in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group and 192.2 hours (95% CI, 174.5-238.3 hours) in the placebo group (difference in median, −24.3 hours; 95% CI, −78.7 to 11.7 hours). The primary analysis demonstrated a significant difference in the overall distribution of the time to symptom resolution among the groups, whereas the 95% CI of the difference in the median included 0 as a secondary analysis (Figure 2A). No significant difference in the time to resolution of the 5 COVID-19 symptoms was observed between the 125-mg ensitrelvir and placebo groups for patients randomized within 120 hours of disease onset (Figure 2B). A difference was observed between the 250-mg ensitrelvir and placebo groups for the primary analysis population (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Time to Resolution of 5 COVID-19 Symptoms in the Intention-to-Treat Population.

The analysis was performed for all patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA at baseline. Patients randomized in less than 72 hours of disease onset in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group were defined as the primary analysis population. A Peto-Prentice generalized Wilcoxon test was applied to test the statistical significance vs placebo. The test was stratified by SARS-CoV-2 vaccination history (yes or no) for patients randomized in less than 72 hours (A) and time from onset to randomization (<72 or ≥72 hours) and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination history (yes or no) for patients randomized within 120 hours (B). The 5 COVID-19 symptoms were stuffy or runny nose, sore throat, cough, feeling hot or feverish, and low energy or tiredness. In the primary analysis population (A), the median time to resolution of the 5 COVID-19 symptoms was 171.2 hours in the 250-mgensitrelvir group and 192.2 hours in the placebo group (difference, −21.0 hours; 95% CI, −73.8 to 7.2 hours). Among patients randomized within 120 hours of disease onset (B), the median difference in the time to resolution of the 5 COVID-19 symptoms between 125-mg ensitrelvir and placebo was −10.6 hours (95% CI, −56.9 to 21.3 hours).

Key Secondary End Points

The least-squares mean (SE) change from baseline in SARS-CoV-2 RNA level on day 4 in the primary analysis population was −2.48 (0.08) log10 copies/mL in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group compared with −1.01 (0.08) log10 copies/mL in the placebo group (P < .001) (Table 2). A significant difference was observed in the time to first negative SARS-CoV-2 titer in the primary analysis population between the 125-mg ensitrelvir (median, 36.2 hours; 95% CI, 23.4-43.2 hours) and placebo (median, 65.3 hours; 95% CI, 62.0-66.8 hours) groups (difference, −29.1 hours; 95% CI, −42.3 to −21.1; P < .001) (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Similar results were obtained for patients randomized within 120 hours of disease onset (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2).

Table 2. Change From Baseline to Day 4 in SARS-CoV-2 RNA Levels, Time to Resolution of 12 COVID-19 Symptoms, and Time to Resolution of 14 COVID-19 Symptomsa.

| Variable | Ensitrelvir, 125 mg (n = 347)b | Ensitrelvir, 250 mg (n = 340) | Placebo (n = 343) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change from baseline to day 4 in SARS-CoV-2 RNA level | |||

| Patients, No. | 340 | 333 | 337 |

| LS mean (SE), log10 copies/mLc | −2.48 (0.08) | −2.49 (0.08) | −1.01 (0.08) |

| Difference from placebo, LS mean (SE) [95% CI], log10 copies/mLc | −1.47 (0.08) [−1.63 to −1.31] | −1.48 (0.08) [−1.64 to −1.32] | NA |

| P valuec | <.001 | <.001 | NA |

| Time to resolution of 12 COVID-19 symptomsd | |||

| Patients, No | 336 | 330 | 321 |

| Median (95% CI), h | 179.2 (152.1 to 212.1) | 184.9 (168.9 to 226.2) | 213.2 (185.8 to 253.8) |

| Difference from placebo, median (95% CI), h | −34.0 (−85.9 to 8.3) | −28.3 (−72.8 to 14.7) | NA |

| P valuee | .07 | .08 | |

| Time to resolution of 14 COVID-19 symptomsf | |||

| Patients, No. | 336 | 330 | 321 |

| Median (95% CI), h | 187.8 (156.4 to 217.0) | 190.3 (171.4 to 244.0) | 231.8 (192.1 to 265.8) |

| Difference from placebo, median (95% CI), h | −44.1 (−95.3 to 4.5) | −41.5 (−81.2 to 27.3) | NA |

| P valuee | .03 | .05 | NA |

Abbreviations: LS, least-squares; NA, not applicable.

Results are for the intention-to-treat population of patients randomized in less than 72 hours of disease onset.

Primary analysis population.

Analysis of covariance using baseline SARS-CoV-2 RNA and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination history (yes or no) as covariates.

Low energy or tiredness, muscle or body aches, headache, chills or shivering, feeling hot or feverish, stuffy or runny nose, sore throat, cough, shortness of breath (difficulty breathing), nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Based on a Peto-Prentice generalized Wilcoxon test stratified by SARS-CoV-2 vaccination history (yes or no).

Low energy or tiredness, muscle or body aches, headache, chills or shivering, feeling hot or feverish, stuffy or runny nose, sore throat, cough, shortness of breath (difficulty breathing), nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anosmia, and dysgeusia.

Other Secondary End Points

No significant difference was observed in the time to resolution of the 12 COVID-19 symptoms in the primary analysis population between the 125-mg ensitrelvir and placebo groups. A difference was observed in the time to resolution of the 14 COVID-19 symptoms in the primary analysis population between the 125-mg ensitrelvir and placebo groups (Table 2).

No difference was observed between the 125-mg ensitrelvir and placebo groups in the time to resolution of the 12 and 14 COVID-19 symptoms among patients randomized within 120 hours of disease onset (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels and SARS-CoV-2 titers in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group were lower than those in the placebo group up to day 9 and day 6, respectively, irrespective of time to randomization (eFigures 2 and 3 in Supplement 2). None of the patients reported receiving mechanical ventilation or died, and only 1 patient each in the 125-mg ensitrelvir and placebo groups required COVID-19–related hospitalization or equivalent recuperation during the study period.

Safety

Adverse events were assessed in 604 patients in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group, 599 in the 250-mg ensitrelvir group, and 605 in the placebo group. Adverse events occurred in 267 patients in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group (44.2%), 321 in the 250-mg ensitrelvir group (53.6%), and 150 in the placebo group (24.8%); treatment-related adverse events occurred in 148 patients in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group (24.5%), 217 in the 250-mg ensitrelvir group (36.2%), and 60 in the placebo group (9.9%) (Table 3). Most of the adverse events were mild, and most treatment-related adverse events resolved without sequelae.

Table 3. Summary of Adverse Events in the Safety Analysis Populationa.

| Adverse events | Patients, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensitrelvir, 125 mg (n = 604) | Ensitrelvir, 250 mg (n = 599) | Placebo (n = 605) | |

| Any adverse event | 267 (44.2) | 321 (53.6) | 150 (24.8) |

| Any treatment-related adverse event | 148 (24.5) | 217 (36.2) | 60 (9.9) |

| Any serious adverse eventb | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Adverse events leading to death | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adverse events leading to treatment discontinuationc | 4 (0.7) | 6 (1.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Adverse events occurring in ≥2% of patients in either intervention group | |||

| Headache | 13 (2.2) | 20 (3.3) | 14 (2.3) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (1.0) | 9 (1.5) | 12 (2.0) |

| High-density lipoprotein level decreased | 188 (31.1) | 231 (38.6) | 23 (3.8) |

| Blood triglyceride levels increased | 49 (8.1) | 74 (12.4) | 32 (5.3) |

| Blood bilirubin level increased | 36 (6.0) | 56 (9.3) | 6 (1.0) |

| Blood cholesterol level decreased | 20 (3.3) | 28 (4.7) | 3 (0.5) |

| Bilirubin conjugated increased | 15 (2.5) | 20 (3.3) | 3 (0.5) |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase level increased | 14 (2.3) | 8 (1.3) | 11 (1.8) |

| Blood lactate dehydrogenase level increased | 6 (1.0) | 15 (2.5) | 6 (1.0) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase level increased | 4 (0.7) | 9 (1.5) | 12 (2.0) |

| Treatment-related adverse events occurring in ≥2% of patients in either intervention group | |||

| Headache | 4 (0.7) | 13 (2.2) | 2 (0.3) |

| High-density lipoprotein level decreased | 111 (18.4) | 157 (26.2) | 9 (1.5) |

| Blood triglyceride levels increased | 16 (2.6) | 37 (6.2) | 17 (2.8) |

| Blood bilirubin level increased | 17 (2.8) | 35 (5.8) | 3 (0.5) |

| Blood cholesterol level decreased | 8 (1.3) | 12 (2.0) | 1 (0.2) |

Data for all patients who received at least 1 ensitrelvir or placebo dose are shown.

Both serious adverse events were judged as not treatment related, and patients recovered with appropriate intervention.

Among the adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation, mild eczema and mild vomiting in 1 patient each in the ensitrelvir, 125 mg, group; mild rash and moderate rash in 1 patient each in the ensitrelvir, 250 mg, group; and moderate hypoesthesia and mild muscular weakness in 1 patient in the placebo group were judged as treatment related by the investigator. All treatment-related adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation were deemed to be resolving or resolved after study discontinuation.

Serious adverse events were observed in 2 patients (heavy menstrual bleeding in 1 patient in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group on day 14 and acute cholecystitis in 1 patient in the placebo group on day 9), both of which were judged as not treatment related. A decrease in high-density lipoprotein levels was the most frequently reported adverse event (188 [31.1%] in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group, 231 [38.6%] in the 250-mg ensitrelvir group, and 23 [3.8%] in the placebo group) and the most common treatment-related adverse event (111 [18.4%] in the 125-mg ensitrelvir group, 157 [26.2%] in the 250-mg ensitrelvir group, and 9 [1.5%] in the placebo group) in both ensitrelvir groups. A transient change in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride, total bilirubin, and iron levels was observed on day 6 in the ensitrelvir groups, which resolved without additional treatment (eFigure 4 in Supplement 2). None of the patients developed clinical jaundice.

Adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation were recorded in 12 patients. A total of 365 patients in the ensitrelvir groups had any treatment-related adverse events, and in 335 patients (91.8%), these adverse events were resolved by day 28 (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). No adverse events leading to death were reported (Table 3).

Discussion

This phase 3 randomized clinical trial was conducted during the Omicron BA.2 phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and involved 91.0% of patients who had received 2 or more doses of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and 72.2% of participants without risk factors for severe disease. There was a significant difference between ensitrelvir, 125 mg, once-daily treatment (375 mg on day 1) and placebo groups in the time to resolution of the 5 typical symptoms of Omicron variant infection among patients randomized in less than 72 hours of disease onset. In this population, ensitrelvir treatment shortened the symptom duration by approximately 1 day compared with placebo, from a median of 5 to 4 days. Moreover, a significant reduction compared with placebo was observed in the 2 key secondary end points representing antiviral efficacy. Ensitrelvir was generally well tolerated, and the most commonly observed adverse event, a decrease in high-density lipoprotein levels, is consistent with the findings of previous clinical studies of ensitrelvir.19,20,26

Previous clinical trials9,10 of oral antivirals for COVID-19 were conducted during the Delta phase of the pandemic in unvaccinated, high-risk adults and demonstrated a reduction in the risk of hospitalization or death as the primary end point. However, given the administration of COVID-19 vaccinations and the nature of the infection caused by the Omicron variant, these end points could no longer be a viable option. Indeed, published studies3,4,27 report a significant reduction in the risk of death, hospitalization, or severe disease associated with the Omicron vs Delta infection. Moreover, community-based studies28,29 suggest limited effectiveness of these antivirals for high-risk, vaccinated adults or patients infected with the Omicron variant in reducing the risk of severe COVID-19.

The guidance issued by the FDA in 2020 discusses approaches to measure common symptoms of COVID-19 in drug clinical trials, which include the use of patient-reported outcomes.23 The phase 2/3 EPIC-SR (Evaluation of Protease Inhibition for COVID-19 in Standard-Risk Patients) study used self-reported, sustained alleviation of all targeted COVID-19 symptoms for 4 days as a novel primary end point to assess the efficacy of ritonavir-boosted nirmatrelvir.30 Although a shortened time to sustained alleviation and resolution of COVID-19 signs and symptoms was demonstrated in nonhospitalized, high-risk adults with COVID-19 (EPIC-HR study),31 the EPIC-SR study did not show a meaningful difference in the time to sustained symptom alleviation through day 28.32 The current SCORPIO-SR study met the primary end point and demonstrated clinical efficacy of ensitrelvir in the resolution of COVID-19 symptoms (sustained for at least 24 hours) irrespective of the presence of risk factors for severe disease.

Ensitrelvir demonstrated clinical benefit for mild to moderate COVID-19 in terms of symptom resolution and virus reduction. To ensure its efficacy in various patient populations, additional clinical trials are being conducted, including SCORPIO-HR33 for patients regardless of presence of high-risk factors and STRIVE (Strategies and Treatments for Respiratory Infections & Viral Emergencies: Shionogi Protease Inhibitor)34 for inpatients, both of which are in collaboration with the National Institutes of Health, and 1 pediatric study.35

Limitations

The major limitation of this study is that it was conducted only in Asian countries, with a limited number of non-Asian patients. Also, ensitrelvir shortened the symptom duration, but the difference in median time was approximately 1 day compared with placebo. The efficacy and safety of ensitrelvir in various patient populations should be further assessed in daily clinical settings.

Conclusions

In this randomized clinical trial, ensitrelvir treatment, 125 mg, once daily demonstrated a reduction in the time to resolution of the 5 typical COVID-19 symptoms compared with placebo in patients treated in less than 72 hours of disease onset; the absolute difference in median time to resolution was approximately 1 day. The results also showed favorable antiviral efficacy of ensitrelvir. Although a transient decrease in high-density lipoprotein levels was observed, ensitrelvir was well tolerated.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eAppendix. List of Investigators

eMethods. Supplementary Methods

eFigure 1. Time to First Negative SARS-CoV-2 Viral Titer (Modified Intention-to-Treat Population)

eFigure 2. SARS-CoV-2 Viral RNA Levels up to Day 21 (Intention-to-Treat Population)

eFigure 3. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Titer up to Day 21 (Modified Intention-to-Treat Population)

eFigure 4. Levels of HDL Cholesterol, Triglycerides, Total Bilirubin, and Iron (Safety Analysis Population)

eTable 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline (Safety Analysis Population)

eTable 2. Representativeness of Trial Participants

eTable 3. Details of Risk Factors for Severe Disease at Baseline (Intention-to-Treat Population)

eTable 4. Change from Baseline to Day 4 in SARS-CoV-2 Viral RNA Levels, Time to Resolution of the 12 COVID-19 Symptoms, and Time to Resolution of the 14 COVID-19 Symptoms (Intention-to-Treat Population, Patients Randomized Within 120 Hours of Disease Onset)

eTable 5. Outcomes of Treatment-Related Adverse Events (Safety Analysis Population)

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern

- 2.Wolter N, Jassat W, Walaza S, et al. Early assessment of the clinical severity of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant in South Africa: a data linkage study. Lancet. 2022;399(10323):437-446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00017-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auvigne V, Vaux S, Strat YL, et al. Severe hospital events following symptomatic infection with Sars-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta variants in France, December 2021-January 2022: a retrospective, population-based, matched cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;48:101455. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nyberg T, Ferguson NM, Nash SG, et al. ; COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) consortium . Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022;399(10332):1303-1312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00462-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grøsland M, Reme BA, Gjefsen HM. Impact of Omicron on sick leave across industries: a population-wide study. Scand J Public Health. 2023;51(5):759-763. doi: 10.1177/14034948221123163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopsidas I, Karagiannidou S, Kostaki EG, et al. Global distribution, dispersal patterns, and trend of several Omicron subvariants of SARS-CoV-2 across the globe. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7(11):373. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed7110373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . TAG-VE statement on Omicron sublineages BQ.1 and XBB. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://www.who.int/news/item/27-10-2022-tag-ve-statement-on-omicron-sublineages-bq.1-and-xbb

- 8.Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. ; ACTT-1 Study Group Members . Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):1813-1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, et al. ; MOVe-OUT Study Group . Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(6):509-520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, et al. ; EPIC-HR Investigators . Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(15):1397-1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2118542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takashita E, Yamayoshi S, Simon V, et al. Efficacy of antibodies and antiviral drugs against Omicron BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5 subvariants. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(5):468-470. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2207519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamasoba D, Kosugi Y, Kimura I, et al. ; Genotype to Phenotype Japan (G2P-Japan) Consortium . Neutralisation sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants to therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(7):942-943. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00365-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng B, Abdullahi A, Ferreira IATM, et al. ; CITIID-NIHR BioResource COVID-19 Collaboration; Genotype to Phenotype Japan (G2P-Japan) Consortium; Ecuador-COVID19 Consortium . Altered TMPRSS2 usage by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron impacts infectivity and fusogenicity. Nature. 2022;603(7902):706-714. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04474-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unoh Y, Uehara S, Nakahara K, et al. Discovery of S-217622, a noncovalent oral SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease inhibitor clinical candidate for treating COVID-19. J Med Chem. 2022;65(9):6499-6512. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uraki R, Kiso M, Iida S, et al. ; IASO study team . Characterization and antiviral susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2. Nature. 2022;607(7917):119-127. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04856-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sasaki M, Tabata K, Kishimoto M, et al. S-217622, a SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor, decreases viral load and ameliorates COVID-19 severity in hamsters. Sci Transl Med. 2023;15(679):eabq4064. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq4064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawashima S, Matsui Y, Adachi T, et al. Ensitrelvir is effective against SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease mutants circulating globally. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2023;645:132-136. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2023.01.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uraki R, Ito M, Kiso M, et al. Antiviral and bivalent vaccine efficacy against an omicron XBB.1.5 isolate. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(4):402-403. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00070-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukae H, Yotsuyanagi H, Ohmagari N, et al. A randomized phase 2/3 study of ensitrelvir, a novel oral SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease inhibitor, in Japanese patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 or asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: results of the phase 2a part. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66(10):e0069722. doi: 10.1128/aac.00697-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukae H, Yotsuyanagi H, Ohmagari N, et al. Efficacy and safety of ensitrelvir in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19: the phase 2b part of a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 study. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(8):1403-1411. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yotsuyanagi H, Ohmagari N, Doi Y, et al. A phase 2/3 study of S-217622 in participants with SARS-CoV-2 infection (Phase 3 part). Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(8):e33024. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000033024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Food and Drug Administration . Assessing COVID-19-related symptoms in outpatient adult and adolescent subjects in clinical trials of drugs and biological products for COVID-19 prevention or treatment. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/assessing-covid-19-related-symptoms-outpatient-adult-and-adolescent-subjects-clinical-trials-drugs

- 24.Hiroshima Prefectural Health and Welfare Bureau . Findings from the analysis of J-SPEED (Surveillance in Post Extreme Emergencies and Disasters, Japan version) data: wave 7 analysis. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000975398.pdf

- 25.Freidlin B, Korn EL. Methods for accommodating nonproportional hazards in clinical trials: ready for the primary analysis? J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(35):3455-3459. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimizu R, Sonoyama T, Fukuhara T, Kuwata A, Matsuo Y, Kubota R. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of the novel antiviral agent ensitrelvir fumaric acid, a SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease inhibitor, in healthy adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022;66(10):e0063222. doi: 10.1128/aac.00632-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyams C, Challen R, Marlow R, et al. ; AvonCAP Research Group . Severity of Omicron (B.1.1.529) and Delta (B.1.617.2) SARS-CoV-2 infection among hospitalised adults: a prospective cohort study in Bristol, United Kingdom. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2023;25:100556. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butler CC, Hobbs FDR, Gbinigie OA, et al. ; PANORAMIC Trial Collaborative Group . Molnupiravir plus usual care versus usual care alone as early treatment for adults with COVID-19 at increased risk of adverse outcomes (PANORAMIC): an open-label, platform-adaptive randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10373):281-293. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02597-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Najjar-Debbiny R, Gronich N, Weber G, et al. Effectiveness of molnupiravir in high-risk patients: a propensity score matched analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(3):453-460. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ClinicalTrials.gov . Evaluation of Protease Inhibition for COVID-19 in Standard-Risk Patients (EPIC-SR). NCT05011513. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05011513

- 31.Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, et al. 1156. Sustained alleviation and resolution of targeted COVID-19 symptoms with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir versus placebo. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(suppl 2):ofac492.994. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac492.994 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Food and Drug Administration . Meeting of the Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee March 16, 2023: FDA Briefing Document. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/166197/download

- 33.ClinicalTrials.gov . A Study to Compare S-217622 With Placebo in Non-Hospitalized Participants With COVID-19 (SCORPIO-HR). NCT05305547. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05305547

- 34.ClinicalTrials.gov . Strategies and Treatments for Respiratory Infections &; Viral Emergencies (STRIVE): Shionogi Protease Inhibitor. NCT05605093. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05605093

- 35.ClinicalTrials.gov . A Phase 3 Study of S-217622 in Pediatric Participants Aged 6 to <12 With SARS-CoV-2 Infection. jRCT2031230140. Accessed October 2, 2023. https://jrct.niph.go.jp/en-latest-detail/jRCT2031230140

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eAppendix. List of Investigators

eMethods. Supplementary Methods

eFigure 1. Time to First Negative SARS-CoV-2 Viral Titer (Modified Intention-to-Treat Population)

eFigure 2. SARS-CoV-2 Viral RNA Levels up to Day 21 (Intention-to-Treat Population)

eFigure 3. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Titer up to Day 21 (Modified Intention-to-Treat Population)

eFigure 4. Levels of HDL Cholesterol, Triglycerides, Total Bilirubin, and Iron (Safety Analysis Population)

eTable 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline (Safety Analysis Population)

eTable 2. Representativeness of Trial Participants

eTable 3. Details of Risk Factors for Severe Disease at Baseline (Intention-to-Treat Population)

eTable 4. Change from Baseline to Day 4 in SARS-CoV-2 Viral RNA Levels, Time to Resolution of the 12 COVID-19 Symptoms, and Time to Resolution of the 14 COVID-19 Symptoms (Intention-to-Treat Population, Patients Randomized Within 120 Hours of Disease Onset)

eTable 5. Outcomes of Treatment-Related Adverse Events (Safety Analysis Population)

Data Sharing Statement