Abstract

Rationale

Indomethacin (INDO) is a widely utilized non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) with recognized effect on the central nervous system. Although previous reports demonstrate that prolonged treatment with indomethacin can lead to behavioral alterations such as anxiety disorder, the biochemical effect exerted by this drug on the brain are not fully understood.

Objectives

The aim of present study was to evaluate if anxiety-like behavior elicited by indomethacin is mediated by brains oxidative stress as well as if alpha-tocopherol, a potent antioxidant, is able to prevent the behavioral and biochemical alterations induced by indomethacin treatment.

Methods

Zebrafish were utilized as experimental model and subdivided into control, INDO 1 mg/Kg, INDO 2 mg/Kg, INDO 3 g/Kg, α-TP 2 mg/Kg, α-TP 2 mg/Kg + INDO 1 mg/Kg and α-TP + INDO 2 mg/Kg groups. Vertical distributions elicited by novelty and brain oxidative stress were utilized to determinate behavioral and biochemical alterations elicited by indomethacin treatment, respectively.

Results

Our results showed that treatment with indomethacin 3 mg/kg induces animal death. No changes in animal survival were observed in animals treated with lower doses of indomethacin. Indomethacin induced significant anxiogenic-like behavior as well as intense oxidative stress in zebrafish brain. Treatment with alpha-tocopherol was able to prevent anxiety-like behavior and brain oxidative stress induced by indomethacin.

Conclusions

Data presented in current study demonstrated for the first time that indomethacin induces anxiety-like behavior mediated by brain oxidative stress in zebrafish as well as that pre-treatment with alpha-tocopherol is able to prevent these collateral effects.

Keywords: NSAIDs, Indomethacin, Anxiety-like behavior, Oxidative stress, Zebrafish

Introduction

Indomethacin (INDO) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) with analgesic, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory properties (Hunskaar and Hole 1987; Lucas 2016; Panchal and Prince Sabina 2023). Previous studies have shown that indomethacin is utilized for treating important diseases such as osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (Crofford 2013; Graham 1993). Although this drug consists of a widely consumed medicine, a considerable number of reports describe significant collateral effects associated with prolonged treatment with indomethacin (El-Mashad et al. 2017; Lövgren and Allander 1964; Sawdy et al. 2003; Seideman and Arbin 1991; Yeh et al. 1982). The literature reports that abdominal pain, heartburn and diarrhea are the main side effects caused by the excessive use of NSAIDs. These effects result from the blockade of COX-1, which results in a reduction in the synthesis of prostaglandins and prostacyclin (PGE2 and PGD2) in the gastrointestinal mucosa. Furthermore, studies report that the hepatic system is also affected by the indiscriminate use of NSAIDs. Damage to hepatic tissue can be observed in two stages: The first is acute hepatitis, which is characterized by jaundice, fever, nausea, elevated transaminases and eosinophilia. The second stage is characterized by periportal inflammation, plasma and lymphocyte infiltration, culminating in active chronic hepatitis (Bessone 2010; Haag 2008; Lanza et al. 1979; Panchal and Prince Sabina 2023).

Previous studies demonstrate that the indiscriminate use of NSAIDs causes severe damage to the central nervous system. The main neuronal symptoms related to its use are drowsiness, confusion, blurred vision, diplopia, headache, various types of strokes and, consequently, cognitive damage, spatial memory and recognition deficits (McCulloch et al. 1982). Past reports demonstrate important cognitive impairment in patients treated with INDO (Clark and Ghose 1992; Hoppmann et al. 1991). In addition, previous articles also demonstrate that NSAIDs evoke severe brain dysfunction and intense behavior alterations such as anxiety in patients (Morgan and Clark 1998; Onder et al. 2004). In face of these effects, studies aimed to describe the neural mechanisms associated with brain toxicity elicited by INDO can be very useful to prevent the behavioral changes elicited by this drug.

It is well documented in the literature that the main effect of INDO on biological systems is the inhibition of cyclooxygenases (COX), particularly cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), which represents an important enzyme for controlling inflammatory response (Chauhan et al. 2018; Chan et al. 2016; Rouzer and Marnett 2009; Seibert et al. 1994). Although few studies have described the action mechanism of indomethacin on the brain, there are strong pieces of evidence demonstrating that treatment with indomethacin induces changes in neurotransmitter systems. Although few studies have described the action mechanism of indomethacin on the brain, there are strong pieces of evidence demonstrating that treatment with indomethacin induces changes in neurotransmitter systems. This drug use can reduce synaptic vesicle fusion events of the glutamatergic system, caused by activation of both purinergic and glutamatergic receptors. Furthermore, the indomethacin can induce the indirect activation of acetylcholine receptors and consequently the increase of glutamate release (Cali et al. 2014; Kanno et al. 2012; Phillis et al. 1994; Pitcher and Henry 1999; Li et al. 2009). Previous reports also showed that prolonged treatment with INDO can evoke oxidative stress in different biological systems like the in liver, kidney and brain tissues, and this phenomenon is associated with decreased activity of Glutathione (GSH), Superoxide dismutase (SOD) and Catalase (CAT) (Ahmad and Mondal 2018; Handa et al. 2014; Hegab et al. 2018; Khan et al. 2019).

Data from literature reports that oxidative stress acts as a molecular inductor of changes in the tissues homeostasis by altering macromolecules structures such as lipid membranes, DNA and proteins (Balmus et al. 2016; Hovatta et al. 2010; Lv et al. 2019; Malcon et al. 2020). According Fedoce et al. (2018) when this imbalance occurs in brain tissue it can leads to significant behavioral alterations such as panic disorder, depression and anxiety disorder. In this way, the current study aimed to evaluate the participation of oxidative stress as a mechanism of indomethacin-induced anxiety by utilization of a potent antioxidant. Alpha-tocopherol (α-TP) is one of the different isoforms of vitamin E and represents one of the most efficient antioxidants in biological systems (Kamal-Eldin and Appelqvist 1996; Na et al. 2021; Wallert et al. 2019). It is well documented that α-TP can easily cross the blood–brain barrier, having action on the CNS (Lee and Ulatowski 2019; Rigotti 2007). As previously demonstrated by our group, α-TP blocked the brain effects generated by high caffeine consumption even after systemic administration in zebrafish (De Carvalho et al. 2019).

Anxiety-like behavior is an evolutionarily conserved behavior observed in different species, including mammals and fish (Ausderau et al. 2023; Lang et al. 2000; Kysil et al. 2017). Several studies have demonstrated that Danio rerio (zebrafish) represents a powerful model to evaluate mechanisms controlling altered behavior such as anxiety (Assad et al. 2020; Kalueff et al. 2014; Maximino et al. 2011). In fact, it is well documented that molecules inducing anxiogenic effects on humans exert a similar effect on zebrafish (López-Patiño et al. 2008; Mathur and Guo 2011; Stewart et al. 2011). This species also presents brain regions analogous to those involved in the controlling of anxiety-like behavior in humans, as well as classical vertebrate neurotransmitters such as glutamate, GABA, and serotonin (Assad et al. 2020; Cognato et al. 2012; Kaslin and Panula 2001; Maximino et al. 2013a, b; Maximino et al. 2013a, b). In addition, several toxicological studies have already used the zebrafish to evaluate effect of drugs on redox homeostasis, suggesting this animal as promising model for the field of drug discovery that modulation oxidative stress (Mugoni et al. 2014). All these characteristics make these animals an excellent experimental model for studies aiming to describe neural events controlling altered behavior such as anxiety disorder. Therefore, the present study aims to evaluate the neuroprotective role of α-TP treatment against the behavioral and biochemical effects generated by the systemic administration of indomethacin in zebrafish.

Material and methods

Animals and housing

Eighty-six Danio rerio (zebrafish) long fin from 3–4 months old, weighing 0.4 g (± 0.2) from both sexes (50:50 ratio), were purchased from a local supplier (Belém-Pará). Fish were acclimated in 50 L tanks (50 × 35 × 30) at 25 ºC ± 2, pH 6.5, oxygenation, 14-h/10-h light/dark controlled photoperiod and fed once a day with commercial flocculated feed (Tetra, Germany) with density of 1 animal per liter and were acclimatized for a minimum period of 15 days, according to previous studies performed by our group. All experimental procedures were made in accordance with the National Council of Animal Experimentation Control (CONCEA) and previously approved by the Committee of Ethics in Research with Experimental Animals of the Federal University of Pará (CEPAE—UFPA: 213–14).

Drug administration

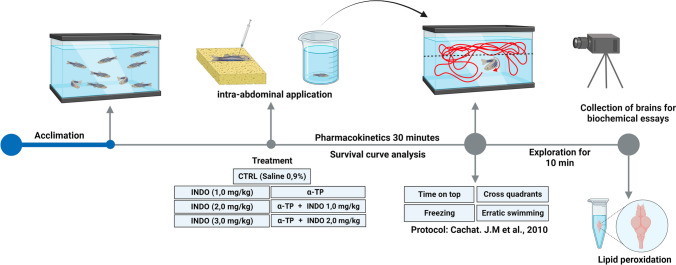

Drugs used in the current study were: Indomethacin (INDO) at concentrations of 1, 2 and 3 mg/kg; alpha-tocopherol (α-TP) at a concentration of 2 mg/kg, all diluted in 1% Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (Hoyberghs et al. 2021). For the biochemical assay, were used N-methyl-2 phenylindole (NMFI), fetal bovine serum (FBS), methanesulfonic acid, malondialdehyde (MDA) all were purchased from SIGMA-ALRICH Company. For drug administration, the animals were individually cryoanesthetized in cold water at 2ºC followed by the application intra-abdominally (i.a) using Hamilton® syringe as previously described by Assad et al (2020). After the procedure, the animals were relocated separately in acclimatization aquarium for 30 min before the tests (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Timeline of experiments, starting with acclimatization, pharmacological applications followed by behavioral tests and brain collection for biochemical assays. (Illustration produced using BioRender.com, free version)

Experimental design

A dose–response curve was performed to determine indomethacin toxicity the first 30 min after the drug injection, this evaluation was carried out by intra-abdominally (i.a) injection of 5 µl indomethacin at 1 mg/kg, 2 mg/kg and 3 mg/kg in zebrafish (n = 8 per group). The dose of indomethacin which evoked a decrease in the zebrafish survival rate was excluded from posterior experiments. Control and experimental groups were classified as follows: Control (CTRL—0.9% saline solution), Indomethacin (INDO—1 mg/kg, 2 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg), alpha-tocopherol (α-TP—2 mg/kg) and α-TP (2 mg/kg) + INDO (1 mg/kg or 2 mg/kg) (n = 8–10 per group). All behavioral tests were performed between 8:00 AM and 1:00 PM.

Novel-tank diving test (Geotaxis)

Animals were tested in the novel-tank diving test as previously described by Egan et al. (2009) and Cachat et al. (2010). Briefly, 30 min after injections of vehicle or drugs, zebrafish were individually transferred to behavioral apparatus which consisted of a glass aquarium (15 cm x 25 cm x 20 cm, width x length x height). The free exploration of the animal in the apparatus was recorded with a digital camera for 10 min, we have considered as the top zone the upper region of apparatus which consisted in 10 cm region measured from the middle of aquarium to the top of water column. The following variables were recorded: time on top (s): the time spent in the top third of the tank; number squares crossed (n): the values of squares crossed were determinate as the number of 5 cm2 squares crossed by the animal during the entire session; erratic swimming (n): the number of “erratic swimming” events, defined as a zig-zag, fast, unpredictable course of swimming of short duration (< 3 s); and freezing (s): the total duration of freezing events, defined as complete cessation of movements with the exception of eye and operculae movements, with the minimum duration of 5 s (Maximino et al. 2013a, b). Videos analyses were performed by double-blind evaluation using the software X-Plo-Rat 2005.

Biochemical assay

Brain oxidative stress in control and treated groups was measured by determining the malondialdehyde (MDA). This method consists in the quantification of molecular products caused by oxidative stress, allowing to indirectly infer the levels of lipid peroxidation in a tissue, using the colorimetric method described by Gérard-Monnier et al. (1998). After the cryoanesthesia, animals were quickly decapitated, and their brain tissue was dissected and stored in micro-tube containing 300 µL of TRIS–HCl buffer (pH 7.4) at -80ºC until the time of analysis. This step was followed by tissue sonication and homogenization as previously described by Pinheiro et al. (2022). The homogenate was then centrifuged at 5600 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. MDA levels in the samples were determined by reaction at 37 °C in the presence of 10 mM N-methyl-2 phenylindole (NMFI) and methanesulfonic acid solution. Lipid peroxidation in the brains was analyzed based on standard curve concentrations of malondialdehyde (MDA), measured by absorbance at λ = 570 nm. MDA concentration was quantified in nmol per milligram of protein, and protein levels were determined by the Bradford method. The values were expressed as a percentage of the control.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean and standard of mean error (S.E.M) for behavioral analysis and percentage of controls for biochemical analysis. The normal distribution of data was determined by the Shapiro–Wilk test. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test was applied to evaluate the biochemical and behavioral data. Log-rank Kaplan–Meier curve test was utilized to analyze the survival curve. All analyzes were performed using the GraphPad Prism software version 9.3.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), with a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

Indomethacin toxicity in zebrafish

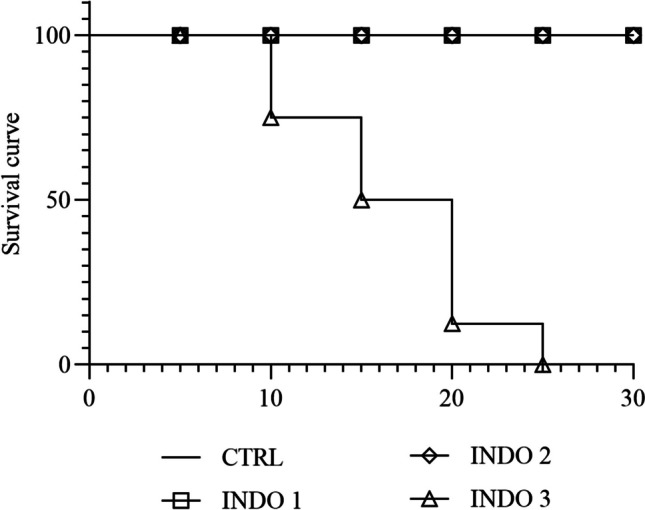

To address the effect of indomethacin toxicity at different doses, subjects received INDO 1 mg/kg, 2 mg/kg, and 3 mg/kg and CTRL (0.9% NaCl) intra-abdominally and were observed for 30 min. Survival data showed that treatment with indomethacin at 3 mg/kg promoted significant toxicity, inducing 100% of mortality after 10–25 min (Fig. 2). 1 mg/kg and 2 mg/kg of indomethacin did not exert alterations in the animal survive as observed in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Effect of indomethacin on zebrafish survive. Control Saline 0,9% = CTRL, Indomethacin 1 mg/Kg = INDO 1, Indomethacin 2 mg/Kg = INDO 2 and Indomethacin 3 mg/Kg = INDO 3. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. n = 8 animals/group

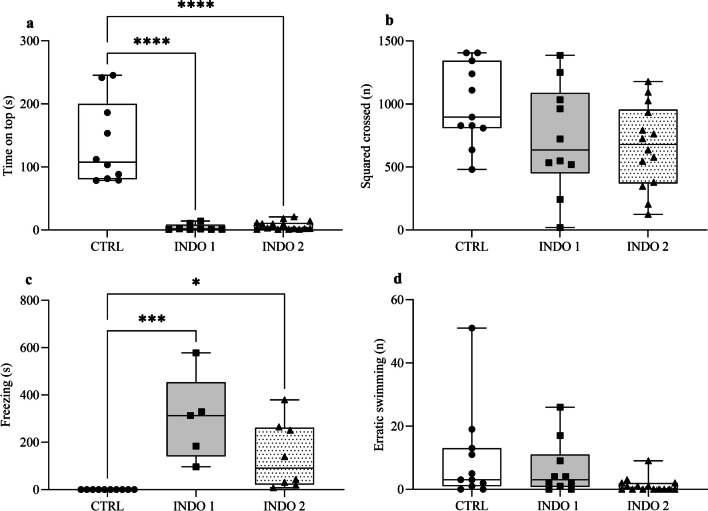

Indomethacin treatment induces anxiety-like behavior

Results of the novel tank diving test demonstrated that indomethacin induces anxiety-like behavior in zebrafish. The animals treated with indomethacin at 1 mg/kg and 2 mg/kg spent less time at the top of the apparatus (Fig. 3a: F (2, 30) = 44,61; CTRL = 136.8 ± 20.90 vs. INDO 1 = 3.98 ± 1.88 vs. INDO 2 = 7.06 ± 1.72; p < 0.0001). This data demonstrate that indomethacin induces more than 80% reduction in time spent in the top of apparatus suggesting a potent anxiogenic effect. Data of squares crossed evaluation showed that indomethacin had no significant effect on the locomotion of treated zebrafish when compared with control group (Fig. 3b). However, we also evidenced that animals treated with indomethacin at 1 mg/kg and 2 mg/kg had an increase freezing time compared to the control group (Fig. 3c: F (2, 20) = 11,35; CTRL = 0.06 ± 0.04 vs. INDO 1 = 300.20 ± 81.66 vs. INDO 2 = 141.70 ± 49.81; p = 0,0005). The erratic swimming values did not show significant differences between the groups treated with indomethacin and the control group (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Effect of indomethacin on (a) time on top, (b) squares crossed, (c) Freezing and (d) erratic swimming test. Control Saline 0,9% = CTRL (n = 10), Indomethacin 1 mg/Kg = INDO 1 (n = 8) and Indomethacin 2 mg/Kg = INDO 2 (n = 15). Graphs represent the mean ± S.E.M and comparisons were made using ANOVA one-way test followed by the Tukey test. ****p < 0,00001 vs. CTRL, ***p < 0,0001 vs. CTRL, *p < 0,001 vs. CTRL

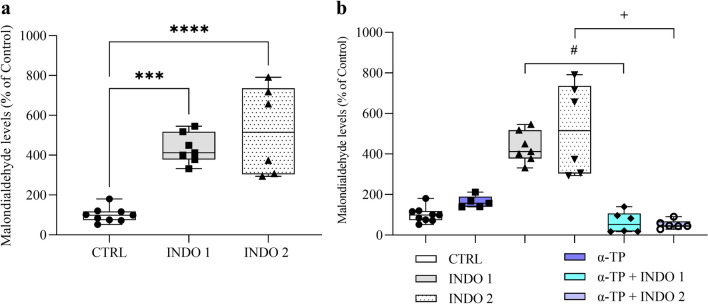

The oxidative stress induced by Indomethacin in zebrafish brain is prevented by the alpha-tocopherol

Indomethacin treatment induced an increase in MDA levels in the zebrafish brain after 30 min of exposure (Fig. 4a: F (2, 19) = 24,94; CTRL = 100.00 ± 12.43 vs. INDO 1 = 433.61 ± 28.83 vs. INDO 2 = 523.50 ± 91.10; p < 0,0001). As observed in Fig. 4, treatment with α-TP prevented MDA elevation induced by indomethacin at doses 1 mg/kg and 2 mg/kg in the zebrafish brain (Fig. 4b: F (5, 33) = 28,07; α-TP + INDO 1 = 62.42 ± 21.04 vs. INDO 1 = 433.61 ± 28.83; p = 0.0003 and α-TP + INDO 2 = 52.33 ± 8.58 vs. INDO 2 = 523.50 ± 91.10; p < 0,0001). α-TP treatment did not have a significant effect on MDA levels compared to the control group, as well as the groups pretreated with α-TP.

Fig. 4.

Lipid peroxidation in zebrafish brain (a, b). Control Saline 0,9% = CTRL (n = 9), Indomethacin 1mg/Kg = INDO 1 (n = 7) and Indomethacin 2mg/Kg = INDO 2 (n = 6). Data are expressed as percent of control ± S.E.M. Data were compared using ANOVA-one way test followed by the Tukey test. ****p < 0,00001 vs. CTRL, ***p < 0,0001 vs. CTRL, #p < 0,00001 vs. INDO 1, +p < 0,0001 vs. INDO 2

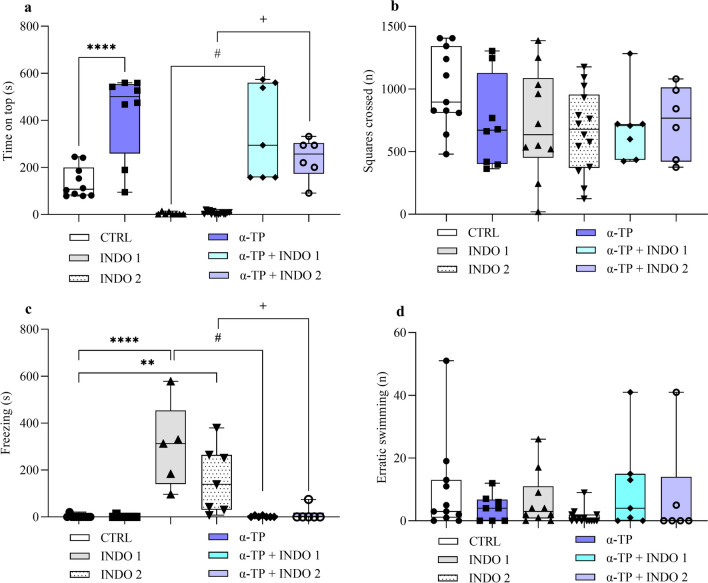

Alpha-tocopherol prevents indomethacin-induced anxiety-like behavior

Our data showed that alpha-tocopherol pre-treatment prevented the indomethacin-induced 1 mg/kg and 2 mg/kg decrease in exploration time on top: (Fig. 5a: F (5, 48) = 24,48; α-TP + INDO 1 = 338.79 ± 74.76 vs. INDO 1 = 3.98 ± 1.75; p < 0.0001 and α-TP + INDO 2 = 201.87 ± 38.87 vs. INDO 2 = 7.06 ± 1.72; p < 0,0001). In addition, we observed that pre-treatment with α-TP promoted a potent anxiolytic effect, with an increased exploration time at the top compared to the control group, both for individuals who received indomethacin or not: (Fig. 5a: F (5, 48) = 24,48; CTRL = 129.73 ± 19.25 vs. α-TP = 426,8 ± 63,91 vs. α-TP + INDO 1 = 338.79 ± 74.76 vs. α-TP + INDO 2 = 201.87 ± 38.8; p < 0,0001). Alpha-tocopherol also blocked indomethacin-induced freezing behavior at both doses: (Fig. 5c: F (5, 38) = 13,39; α-TP + INDO 1 = 1.94 ± 1.25 vs. INDO 1 = 300 ± 181.66; p < 0.0001 and α-TP + INDO 2 = 12.43 ± 12.43 vs. INDO 2 = 159.20 ± 53.82; p = 0,0227). However, there were no significant differences between the groups treated with α-TP and α-TP + INDO with the control (Fig. 5c). Analysis of the number of squares crossed (Fig. 5b) and erratic swimming (Fig. 5d) no showed a significant among the groups.

Fig. 5.

Effect of alpha-tocopherol on (a) time on top, (b) squares crossed, (c) Freezing and (d) erratic swimming in the geotaxy of zebrafish treated with indomethacin. Control Saline 0,9% = CTRL (n = 10), Indomethacin 1 mg/Kg = INDO 1 (n = 8), Indomethacin 2 mg/Kg = INDO 2 (n = 15), Alpha-Tocopherol = α-TP (n = 8), α-TP + INDO 1 (n = 7) and α-TP + INDO 2 (n = 6). Graphs represent the mean ± S.E.M. Data were compared using ANOVA-one way test followed by the Tukey test. ****p < 0,00001 vs. CTRL, **p < 0,001 vs. CTRL, #p < 0,0001 vs. INDO 1, +p < 0,0001 vs. INDO 2

Discussion

Data presented in the current study demonstrated for the first time that brain oxidative stress mediates indomethacin-induced anxiety-like behavior. These behavioral and oxidative changes were prevented by treatment with α-TP, which is a potent antioxidant with neuroprotective action against damage caused by redox desbalance. Our data are in agreement with previous studies demonstrating neuropsychological dysfunctions associated to adverse effect elicited by treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Adhikary et al. 2011; Bercik et al. 2010; Goodwin et al. 2013). In fact, animal models have emerged as an important tool for elucidating the toxicological events associated with indomethacin’s action in the brain (Benesová et al. 2001; Enos et al. 2013). Anterior studies already demonstrated that indomethacin amplifies the anxiety-like behavior in animals submitted to physical stress (Fernández-Guasti and Martínez-Mota 2003). Our study demonstrated that zebrafish displayed similar anxiogenic-like behavior when treated with different doses of indomethacin. Subjects treated with indomethacin spent less time in the upper portion of the apparatus when compared with controls. Data demonstrating that indomethacin treatment does not exert significant locomotor alterations, ratify our interpretation that indomethacin evoked anxiogenic behavior in zebrafish. In other words, the time spent by the subjects at the bottom of the apparatus is provoked by anxiety-like behavior, but not by motor impairment elicited by indomethacin treatment (Neelkantan et al. 2013; Rosemberg et al. 2012). This behavior is also observed in subjects submitted to classical anxiogenic compounds such as alarm substance (Lima-Maximino et al. 2020), sub-convulsant doses of pentylenetetrazol (Wong et al. 2010) or caffeine (De Carvalho et al. 2019). In this way, our finds ratify the literature demonstrating that zebrafish represent a powerful animal model to evaluate neurochemical and behavioral changes associated with drugs leading to a collateral effect on the central nervous system (Maximino et al. 2014; Mocelin et al. 2015; Li et al. 2015).

It has been described in the literature that indomethacin can modulate inflammation and oxidative stress in the CNS (Adhikary et al. 2011; Bercik et al. 2010) which may cause altered behavior such as anxiety (Hassan et al. 2014; Masood et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2019; Zheng et al. 2021). Our data have supported this hypothesis since animals treated with indomethacin showed intense oxidative stress in their brain. Although some studies point out that treatment with NSAIDs induces a decrease in anti-inflammatory cytokines, there is strong evidence demonstrating that long treatment with indomethacin can promote the overproduction of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress in different tissues (Ahmad and Mondal 2018; Farooq et al. 2007; Khan et al. 2019). We demonstrated in the present study the close relation between indomethacin-induced anxiety and oxidative stress in the zebrafish brain since treatment with alpha-tocopherol, a potent antioxidant, was able to prevent both anxiety-like behavior and oxidative stress in the brain of animals treated with indomethacin. Our data are aligned with previous studies describing that treatment with antioxidants such as vitamin C (Puty et al. 2014) and alpha-tocopherol (De Carvalho et al. 2019) can prevent anxiety-like behavior in zebrafish. In rodent models, several studies also have reported the involvement of oxidative stress in anxiety-like behaviors (Dhingra et al. 2014; Vollert et al. 2011). Desrumaux et al. (2018) demonstrated that decreased levels of alpha-tocopherol and increased levels of central oxidative stress markers, such as cholesterol oxides and cellular peroxides, result in anxiety-like behavior in mice. In addition, the increase in lipid peroxidation alters the levels of antioxidant defenses, such as glutathione, in addition to generating DNA damage and reducing the activity of antioxidant enzymes (Bouayed et al. 2009; Ferreira Mello et al. 2013; Jangra et al. 2014).

Conclusion

Indomethacin induces anxiety-like behavior and lipid peroxidation in brain tissue of zebrafish. Protective effect exerted by alpha-tocopherol treatment against indomethacin-induced behavioral and biochemical alterations let us to conclude that indomethacin evokes anxiety by generation of oxidative stress in zebrafish brain. These findings strongly suggest that generation of oxidative stress represents an important mechanism of generation of anxiety elicited by indomethacin treatment. Our data also support that utilization of antioxidants could be an efficient strategy to prevent the deleterious effects of indomethacin on the CNS.

Author contributions

A.M.H and J.P. wrote the main manuscript text and E.P. and G.R. prepared Figs. 1-5. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The authors declare that all data were generated in-house and that no paper mill was used.

Funding

This work was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Conselho, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico Number: 313872/2020–1.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethical approval

All experimental procedures were made in accordance with the National Council of Animal Experimentation Control (CONCEA) and previously approved by the Committee of Ethics in Research with Experimental Animals of the Federal University of Pará (CEPAE—UFPA: 213–14).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adhikary B, Yadav SK, Bandyopadhyay SK, Chattopadhyay S. Epigallocatechin Gallate Accelerates Healing of Indomethacin-Induced Stomach Ulcers in Mice. Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63(2):527–536. doi: 10.1016/S1734-1140(11)70519-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad MH, Mondal AC (2018) Determination of Potential Oxidative Damage , Hepatotoxicity , and Cytogenotoxicity in Male Wistar Rats : Role of Indomethacin. no. August: 1–8. 10.1002/jbt.22226 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Assad N, Luz WL, Santos-Silva M, Carvalho T, Moraes S, Picanço-Diniz DLW, Bahia CP, Oliveira Batista EJ, da Conceição Passos A, Oliveira KRHM, Herculano AM. Acute Restraint Stress Evokes Anxiety-Like Behavior Mediated by Telencephalic Inactivation and GabAergic Dysfunction in Zebrafish Brains. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5551. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62077-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausderau KK, Colman RJ, Kabakov S, Schultz-Darken N, Emborg ME. Evaluating depression- and anxiety-like behaviors in non-human primates. Front Behav Neurosci. 2023;16:1006065. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2022.1006065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmus IM, Ciobica A, Antioch I, Dobrin R, Timofte D. Oxidative Stress Implications in the Affective Disorders: Main Biomarkers, Animal Models Relevance, Genetic Perspectives, and Antioxidant Approaches. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:3975101. doi: 10.1155/2016/3975101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benesová O, Tejkalová H, Kristofiková Z, Husek P, Nedvídková J, Yamamotová A. Brain maldevelopment and neurobehavioural deviations in adult rats treated neonatally with indomethacin. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol: J Eur Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;11(5):367–373. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(01)00102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bercik P, Verdu EF, Foster JA, Macri J, Potter M, Huang X, Malinowski P, et al. Chronic Gastrointestinal Inflammation Induces Anxiety-Like Behavior and Alters Central Nervous System Biochemistry in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(6):2102–2112.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessone F. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: What Is the Actual Risk of Liver Damage? World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(45):5651. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i45.5651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouayed J, Rammal H, Soulimani R. Oxidative Stress and Anxiety: Relationship and Cellular Pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2009;2(2):63–67. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.2.7944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachat J, Stewart A, Grossman L, Gaikwad S, Kadri F, Chung KM, Nadine Wu, et al. Measuring Behavioral and Endocrine Responses to Novelty Stress in Adult Zebrafish. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(11):1786–1799. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cali C, Lopatar J, Petrelli F, Pucci L, Bezzi P. G-Protein Coupled Receptor-Evoked Glutamate Exocytosis from Astrocytes: Role of Prostaglandins. Neural Plast. 2014;2014:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2014/254574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho TS, De PB, Santos-Silva Cardoso M, Lima-Bastos S, Luz WL, Assad N, Kauffmann N, et al. Oxidative Stress Mediates Anxiety-Like Behavior Induced by High Caffeine Intake in Zebrafish: Protective Effect of Alpha-Tocopherol. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/8419810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P-C, Hsiao F-C, Chang H-M, Wabitsch M, Hsieh PS. Importance of Adipocyte Cyclooxygenase-2 and Prostaglandin E 2 -prostaglandin E Receptor 3 Signaling in the Development of Obesity-induced Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Insulin Resistance. FASEB J. 2016;30(6):2282–2297. doi: 10.1096/fj.201500127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan AK, Mittra N, Patel DK, Singh C. Cyclooxygenase-2 Directs Microglial Activation-Mediated Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Leading to Intrinsic Apoptosis in Zn-Induced Parkinsonism. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(3):2162–2173. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DWJ, Ghose K. Neuropsychiatric Reactions to Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): The New Zealand Experience. Drug Saf. 1992;7(6):460–465. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199207060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofford LJ. Use of NSAIDs in Treating Patients with Arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(S3):S2. doi: 10.1186/ar4174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cognato GP, Bortolotto JW, Blazina AR, Christoff RR, Lara DR, Vianna MR, Bonan CD. Y-Maze Memory Task in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio): The Role of Glutamatergic and Cholinergic Systems on the Acquisition and Consolidation Periods. Neurobiol Learn Memory. 2012;98(4):321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2012.09.00810.1016/j.nlm.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrumaux CM, Mansuy M, Lemaire S, Przybilski J, Le Guern N, Givalois L, Lagrost L. Brain Vitamin E Deficiency During Development Is Associated With Increased Glutamate Levels and Anxiety in Adult Mice. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12(December):1–7. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra MS, Dhingra S, Kumria R, Chadha R, Singh T, Kumar A, Karan M. Effect of Trimethylgallic Acid Esters against Chronic Stress-Induced Anxiety-like Behavior and Oxidative Stress in Mice. Pharmacol Rep. 2014;66(4):606–612. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan RJ, Bergner CL, Hart PC, Cachat JM, Canavello PR, Elegante MF, Elkhayat SI, et al. Understanding Behavioral and Physiological Phenotypes of Stress and Anxiety in Zebrafish. Behav Brain Res. 2009;205(1):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mashad A-R, El-Mahdy H, El Amrousy D, Elgendy M. Comparative Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Paracetamol, Ibuprofen, and Indomethacin in Closure of Patent Ductus Arteriosus in Preterm Neonates. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(2):233–240. doi: 10.1007/s00431-016-2830-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enos RT, Mark Davis J, McClellan JL, Angela Murphy E. Indomethacin in Combination with Exercise Leads to Muscle and Brain Inflammation in Mice. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2013;33(8):446–451. doi: 10.1089/jir.2012.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq N, Priyamvada S, Khan F, Yusufi ANK. Time Dependent Effect of Gentamicin on Enzymes of Carbohydrate Metabolism and Terminal Digestion in Rat Intestine. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2007;26(7):587–593. doi: 10.1177/09603271079544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedoce AdG, Ferreira F, Bota RG, Bonet-Costa V, Sun PY, Davies KJA. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Anxiety Disorder: Cause or Consequence? Free Radic Res. 2018;52(7):737–750. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2018.1475733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Guasti A, Martínez-Mota L. Orchidectomy Sensitizes Male Rats to the Action of Diazepam on Burying Behavior Latency: Role of Testosterone. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75(2):473–479. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(03)00142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gérard-Monnier D, Erdelmeier I, Régnard K, Moze-Henry N, Yadan JC, Chaudière J (1998) Reactions of 1-methyl-2-phenylindole with malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxyalkenals. Analytical applications to a colorimetric assay of lipid peroxidation. Chem Res Toxicol 11(10):1176–1183. 10.1021/tx9701790 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Goodwin RD, Talley NJ, Hotopf M, Cowles RA, Galea S, Jacobi F. A Link between Physician-Diagnosed Ulcer and Anxiety Disorders among Adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(4):189–192. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DY. Duodenal and Gastric Ulcer Prevention with Misoprostol in Arthritis Patients Taking NSAIDs. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(4):257. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-4-199308150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag MDM. Cyclooxygenase Selectivity of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Risk of Stroke. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(11):1219. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa O, Majima A, Onozawa Y, Horie H, Uehara Y, Fukui A, Omatsu T, Naito Y, Yoshikawa T. The Role of Mitochondria-Derived Reactive Oxygen Species in the Pathogenesis of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug-Induced Small Intestinal Injury. Free Radical Res. 2014;48(9):1095–1099. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2014.928411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan W, Silva CB, Mohammadzai IU, da Rocha JT, Landeira-Fernandez J. Association of Oxidative Stress to the Genesis of Anxiety: Implications for Possible Therapeutic Interventions. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2014;12(2):120–139. doi: 10.2174/1570159X11666131120232135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegab II, Abd-Ellatif RN, Sadek MT. The Gastroprotective Effect of N-Acetylcysteine and Genistein in Indomethacin-Induced Gastric Injury in Rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;96(11):1161–1170. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2017-0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann RA, Peden JG, Ober SK. Central Nervous System Side Effects of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: Aseptic Meningitis, Psychosis, and Cognitive Dysfunction. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(7):1309–1313. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1991.00400070083009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovatta I, Juhila J, Donner J. Oxidative Stress in Anxiety and Comorbid Disorders. Neurosci Res. 2010;68(4):261–275. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyberghs J, Bars C, Ayuso M, Van Ginneken C, Foubert K, Van Cruchten S. DMSO Concentrations up to 1% are Safe to be Used in the Zebrafish Embryo Developmental Toxicity Assay. Front Toxicol. 2021;3:804033. doi: 10.3389/ftox.2021.804033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunskaar S, Hole K. The Formalin Test in Mice: Dissociation between Inflammatory and Non-Inflammatory Pain. Pain. 1987;30(1):103–114. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jangra A, Lukhi MM, Sulakhiya K, Baruah CC, Lahkar M. Protective Effect of Mangiferin against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Depressive and Anxiety-like Behaviour in Mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740(October):337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalueff AV, Stewart AM, Gerlai R. Zebrafish as an Emerging Model for Studying Complex Brain Disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35(2):63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal-Eldin A, Appelqvist LÅ. The Chemistry and Antioxidant Properties of Tocopherols and Tocotrienols. Lipids. 1996;31(7):671–701. doi: 10.1007/BF02522884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno T, Yaguchi T, Nagata T, Nishizaki T. Indomethacin Activates Protein Kinase C and Potentiates Α7 ACh Receptor Responses. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;29(1–2):189–196. doi: 10.1159/000337600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslin J, Panula P. Comparative Anatomy of the Histaminergic and Other Aminergic Systems in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) J Comp Neurol. 2001;440(4):342–377. doi: 10.1002/cne.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Yusufi FNK, Yusufi ANK. Comparative Effect of Indomethacin (IndoM) on the Enzymes of Carbohydrate Metabolism, Brush Border Membrane and Oxidative Stress in the Kidney, Small Intestine and Liver of Rats. Toxicol Rep. 2019;6(March 2018):389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kysil EV, Meshalkina DA, Frick EE, Echevarria DJ, Rosemberg DB, Maximino C, Lima MG, et al. Comparative Analyses of Zebrafish Anxiety-Like Behavior Using Conflict-Based Novelty Tests. Zebrafish. 2017;14(3):197–208. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2016.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Davis M, Öhman A. Fear and Anxiety: Animal Models and Human Cognitive Psychophysiology. J Affect Disord. 2000;61(3):137–159. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00343-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza FL, Royer GL, Nelson RS, Chen TT, Seckman CE, Rack MF. The Effects of Ibuprofen, Indomethacin, Aspirin, Naproxen, and Placebo on the Gastric Mucosa of Normal Volunteers - A Gastroscopic and Photographic Study. Dig Dis Sci. 1979;24(11):823–828. doi: 10.1007/BF01324896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P, Ulatowski LM. Vitamin E: Mechanism of Transport and Regulation in the CNS. IUBMB Life. 2019;71(4):424–429. doi: 10.1002/iub.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R-S, Seto S-W, Alice Lai-Shan Au, Kwan Y-W, Chan S-W, Lee S-Y, Tse C-M, Leung G-H. Inhibitory Effect of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs on Adenosine Transport in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;612(1–3):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Lin J, Zhang Y, Liu X, Chen XQ, Ming Qing Xu, He L, Li S, Guo N. Differential Behavioral Responses of Zebrafish Larvae to Yohimbine Treatment. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232(1):197–208. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3656-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima-Maximino M, Pyterson MP, do Carmo Silva RX, Vidal Gomes GC, Rocha SP, Herculano AM, Rosemberg DB, Maximino C. Phasic and Tonic Serotonin Modulate Alarm Reactions and Post-Exposure Behavior in Zebrafish. J Neurochem. 2020;153(4):495–509. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Patiño MA, Lili Yu, Cabral H, Zhdanova IV. Anxiogenic Effects of Cocaine Withdrawal in Zebrafish. Physiol Behav. 2008;93(1–2):160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lövgren O, Allander E. Side-Effects of Indomethacin. BMJ. 1964;1(5375):118. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5375.118-a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas S. The Pharmacology of Indomethacin. Headache: J Head Face Pain. 2016;56(2):436–446. doi: 10.1111/head.12769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H, Zhu C, Ruolin W, Ni H, Lian J, Yunlong X, Xia Y, et al. Chronic Mild Stress Induced Anxiety-like Behaviors Can Be Attenuated by Inhibition of NOX2-Derived Oxidative Stress. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;114(January):55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcon LMC, Wearick-Silva LE, Zaparte A, Orso R, Luft C, Tractenberg SG, Donadio MVF, de Oliveira JR, Grassi-Oliveira R. Maternal Separation Induces Long-Term Oxidative Stress Alterations and Increases Anxiety-like Behavior of Male Balb/CJ Mice. Exp Brain Res. 2020;238(9):2097–2107. doi: 10.1007/s00221-020-05859-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masood A, Ahmed Nadeem S, Mustafa J, O’Donnell JM. Reversal of Oxidative Stress-Induced Anxiety by Inhibition of Phosphodiesterase-2 in Mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326(2):369–379. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.137208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur P, Guo Su. Differences of Acute versus Chronic Ethanol Exposure on Anxiety-like Behavioral Responses in Zebrafish. Behav Brain Res. 2011;219(2):234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximino C, da Silva AWB, Gouveia A, Herculano AM. Pharmacological Analysis of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Scototaxis. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatr. 2011;35(2):624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximino C, Lima MG, Oliveira KRM, de Jesus E, Batista O, Herculano AM. Limbic Associative and Autonomic Amygdala in Teleosts: A Review of the Evidence. J Chem Neuroanat. 2013;48–49:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximino C, Puty B, Benzecry R, Araújo J, Lima MG, De Jesus E, Batista O, Oliveira KRDM, Crespo-Lopez ME, Herculano AM. Role of Serotonin in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Anxiety: Relationship with Serotonin Levels and Effect of Buspirone, WAY 100635, SB 224289, Fluoxetine and Para-Chlorophenylalanine (PCPA) in Two Behavioral Models. Neuropharmacology. 2013;71:83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximino C, Da Silva AWB, Araujo J, Lima MG, Miranda V, Puty B, Benzecry R, et al. Fingerprinting of Psychoactive Drugs in Zebrafish Anxiety-like Behaviors. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch J, Kelly PAT, Grome JJ, Pickard JD (1982) Local Cerebral Circulatory and Metabolic Effects of Indomethacin. Am J Physiol – Heart Circulatory Physiol 12(3). 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.243.3.h416 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mello F, Stefânia B, Monte AS, McIntyre RS, Soczynska JK, Custódio CS, Cordeiro RC, Chaves JH, et al. Effects of Doxycycline on Depressive-like Behavior in Mice after Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Administration. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(10):1521–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocelin R, Herrmann AP, Marcon M, Rambo CL, Rohden A, Bevilaqua F, Abreu MSD, et al. N-Acetylcysteine Prevents Stress-Induced Anxiety Behavior in Zebrafish. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2015;139:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A, Clark D. CNS Adverse Effects of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: Therapeutic Implications. CNS Drugs. 1998;9(4):281–290. doi: 10.2165/00023210-199809040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugoni V, Camporeale A, Santoro MM. Analysis of Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish Embryos. J vis Exp. 2014;89:1–11. doi: 10.3791/51328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na Y, Woo J, Choi WI, Lee JH, Hong J, Sung D. α-Tocopherol-Loaded Reactive Oxygen Species-Scavenging Ferrocene Nanocapsules with High Antioxidant Efficacy for Wound Healing. Int J Pharm. 2021;596(January):120205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelkantan N, Mikhaylova A, Stewart AM, Arnold R, Gjeloshi V, Kondaveeti D, Poudel MK, Kalueff AV. Perspectives on Zebrafish Models of Hallucinogenic Drugs and Related Psychotropic Compounds. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2013;4(8):1137–1150. doi: 10.1021/cn400090q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onder G, Pellicciotti F, Gambassi G, Bernabei R. NSAID-Related Psychiatric Adverse Events: Who Is at Risk? Drugs. 2004;64(23):2619–2627. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464230-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchal NK, Prince Sabina E. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): A Current Insight into Its Molecular Mechanism Eliciting Organ Toxicities. Food Chem Toxicol. 2023;172(November 2022):113598. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2022.113598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillis JW, Smith-Barbour M, Perkins LM, O’Regan MH. Indomethacin Modulates Ischemia-Evoked Release of Glutamate and Adenosine from the Rat Cerebral Cortex. Brain Res. 1994;652(2):353–356. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro EF, Cardoso PB, Luz WL, Assad N, Santos-Silva M, Leão LKR, de Moraes SAS et al (2022) Putative activation of cannabinoid receptor type 1 prevents brain oxidative stress and inhibits aggressive-like behavior in zebrafish. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Res. 10.1089/can.2022.0146 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pitcher GM, Henry JL. Mediation and Modulation by Eicosanoids of Responses of Spinal Dorsal Horn Neurons to Glutamate and Substance P Receptor Agonists: Results with Indomethacin in the Rat in Vivo. Neuroscience. 1999;93(3):1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00192-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puty B, Maximino C, Brasil A, Luz WL, da Silva A, Gouveia KR, Oliveira M, De Jesus E, Batista O, Crespo-Lopez ME, Fernando AF, Rocha, and Anderson Manoel Herculano. Ascorbic Acid Protects Against Anxiogenic-Like Effect Induced by Methylmercury in Zebrafish: Action on the Serotonergic System. Zebrafish. 2014;11(4):365–370. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2013.0947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti A. Absorption, Transport, and Tissue Delivery of Vitamin E. Mol Aspects Med. 2007;28(5–6):423–436. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosemberg DB, Braga MM, Rico EP, Loss CM, Córdova SD, Ben HM, Mussulini RE, Blaser, , et al. Behavioral Effects of Taurine Pretreatment in Zebrafish Acutely Exposed to Ethanol. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63(4):613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzer CA, Marnett LJ. Cyclooxygenases: Structural and Functional Insights. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(SUPPL.):S29–34. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800042-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawdy RJ, Lye S, Fisk NM, Bennett PR. A Double-Blind Randomized Study of Fetal Side Effects during and after the Short-Term Maternal Administration of Indomethacin, Sulindac, and Nimesulide for the Treatment of Preterm Labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(4):1046–1051. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert K, Zhang Y, Leahy K, Hauser S, Masferrer J, Perkins W, Lee L, Isakson P. Pharmacological and Biochemical Demonstration of the Role of Cyclooxygenase 2 in Inflammation and Pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91(25):12013–12017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seideman P, Arbin M. Cerebral Blood Flow and Indomethacin Drug Levels in Subjects with and without Central Nervous Side Effects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31(4):429–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb05558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A, Nadine Wu, Cachat J, Hart P, Gaikwad S, Wong K, Utterback E, et al. Pharmacological Modulation of Anxiety-like Phenotypes in Adult Zebrafish Behavioral Models. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(6):1421–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollert C, Zagaar M, Hovatta I, Taneja M, Anthony Vu, Dao An, Levine A, Alkadhi K, Salim S. Exercise Prevents Sleep Deprivation-Associated Anxiety-like Behavior in Rats: Potential Role of Oxidative Stress Mechanisms. Behav Brain Res. 2011;224(2):233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallert M, Ziegler M, Wang X, Maluenda A, Xu X, Yap ML, Witt R, et al. α-Tocopherol Preserves Cardiac Function by Reducing Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Redox Biol. 2019;26(August):101292. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K, Stewart A, Gilder T, Nadine Wu, Frank K, Gaikwad S, Suciu C, et al. Modeling Seizure-Related Behavioral and Endocrine Phenotypes in Adult Zebrafish. Brain Res. 2010;1348(August):209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh TF, Wilks A, Singh J, Betkerur M, Lilien L, Pildes RS. Furosemide Prevents the Renal Side Effects of Indomethacin Therapy in Premature Infants with Patent Ductus Arteriosus. J Pediatr. 1982;101(3):433–437. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(82)80079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Kalueff AV, Song C. Minocycline Ameliorates Anxiety-Related Self-Grooming Behaviors and Alters Hippocampal Neuroinflammation, GABA and Serum Cholesterol Levels in Female Sprague-Dawley Rats Subjected to Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress. Behav Brain Res. 2019;363(018):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng ZH, Tu JL, Li XH, Hua Q, Liu WZ, Liu Y, Pan BX, Hu P, Zhang WH. Neuroinflammation Induces Anxiety- and Depressive-like Behavior by Modulating Neuronal Plasticity in the Basolateral Amygdala. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;91(July 2020):505–518. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.