Abstract

In this report, we show an age-related buildup of agglutinating activity as well as serum activity against rosette formation in children living in areas of Kenya and Gabon where malaria is endemic. Sera from Kenyans in general exhibited a stronger and wider immune response toward the epitopes, probably reflecting a difference in transmission patterns between the two areas. Thus, our results indicate that repeated malaria attacks in areas of endemicity, and consequently exposure to different isolate-specific antigens, will elicit an antibody-mediated response eventually enabling recognition of the majority of rosetting and agglutinating antigens. The correlation between antirosetting and agglutinating capacity was poor in individual cases, indicating that the rosetting epitopes are only a minor part of the highly diverse surface-exposed antigens (mainly PfEMP1) on the surface of parasitized erythrocytes toward which antibodies may react. These data together with our previous findings that the protection against cerebral malaria correlates with presence of antirosetting antibodies shed new light on our understanding of the gradual acquisition of immunity toward severe complications of malarial infection which children reared in areas of endemicity attain.

Acquired immunity to malaria develops in individuals exposed to the parasite, but only after repeated infection. Children are relatively protected during the first months of life, but thereafter rapidly increasing parasite rates have been noted. The mortality rate in areas of hyperendemicity is highest during the first years of life, and by school age a considerable degree of immunity has already developed, with a high prevalence of asymptomatic parasitemia (10, 31). However, persistence of immunity requires repeated infections, and previously immune individuals who have spent less than a year away from a malarious area have been found to be susceptible to the disease (16, 37). Thus, in areas of lower endemicity, with an unstable malaria situation, the immunity of the population is low, and clinical malaria as well as severe complications may occur in all age groups (54).

It is well established that humoral immunity, in addition to cell-mediated immunity, is important in malaria, and passive transfer of serum has been shown to have a protective or at least modifying effect on the disease (17). Antibodies are directed either against a number of identified proteins on the parasite itself or against parasite-derived proteins expressed on the surface of the infected erythrocyte (RBC) during intraerythrocytic development of the parasite (26). It has been suggested that antibodies may block the ligands involved in cytoadherence (47) and also hinder merozoite reinvasion by binding to the merozoite surface, resulting in agglutination or blocking of the surface receptors involved in the penetration of erythrocytes (36, 53).

Several studies have demonstrated a high degree of serological diversity of surface-exposed Plasmodium falciparum-induced antigens (19, 23, 27, 33), and antigenic variation has in fact been reported for several malarial species (9, 22, 25, 35). Surface-exposed antigens undergo a rapid clonal variation in vitro in the absence of immune pressure (41), and the PfEMP1 antigen, believed to play a major part in endothelial cytoadherence, contributes substantially to this antigenic variation (5, 6, 32). Recently it was established that PfEMP1 is closely linked with expression of members of the large and highly polymorphic family of var genes. Parasites of variable immunological and adhesive phenotypes have been shown to be correlated with switching events in this gene family (45), which is a large and diverse array of genes dispersed on several chromosomes, each gene encoding a 200- to 350-kDa protein. The rate of var switching has been estimated to be as high as 2.4% in P. falciparum (45).

Even though the antibody response to most parasite-derived antigens probably plays no part in host defense, a correlation between antibodies to surface-exposed antigens and protection against malarial infection has been demonstrated (34). Investigators have looked for a correlation between humoral immune response to P. falciparum antigens and protection from severe malarial disease but without success. Studies of Thai adults (8) and Gambian children (18) have revealed no differences in total antiparasite immunoglobulin G (IgG) titers between patients with cerebral malaria and those with uncomplicated malaria. Furthermore, the two groups were similar in the ability to agglutinate parasite isolates, suggesting that they had had similar exposures to malaria in the past (18).

We and others have previously described the rosetting phenomenon, i.e., the binding of uninfected RBC around infected ones (14, 20, 48, 50), and shown it to be a risk factor for the development of severe malarial disease, e.g., cerebral malaria (13, 29, 40, 43, 46). Our previous results also indicate that exposure to the rosetting epitopes and the resulting humoral immune response may confer protection against cerebral disease. For example, when serum from a patient was tested against the patient’s own parasites, 17% of the sera from children with cerebral malaria exhibited antirosetting activity, while as many as 93% of the sera from children with uncomplicated disease had the ability to disrupt rosettes in vitro (13, 46).

In this study, we investigated the occurrence of antirosetting antibodies in individuals living in areas holoendemic for P. falciparum malaria and their relation to age and the buildup of clinical immunity or semiimmunity in the population. In addition, we studied the ability of the sera to agglutinate parasitized RBC (PRBC) in order to confirm previous reports on a correlation between antibodies to surface-exposed antigens and immunity to malaria and to compare the expression of these two in vitro markers of immunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and sera. (i) Kenyan material.

Human sera were obtained during February to April from children aged 2 months to 15 years living in Saradidi, an area in western Kenya holoendemic for malaria (4). The clinical status of the children was assessed by physical examination at the Primary Health Care Station. Only children without signs and symptoms of malaria were included in the study. A small number of asymptomatic children had scanty P. falciparum parasitemia.

(ii) Gabonese material.

Human sera were obtained during April to June from children aged 2 months to 11 years attending Hôpital Albert Schweitzer, Lambaréné, Gabon, an area where malaria is predominantly hyperendemic (55). Only children without P. falciparum parasites in peripheral blood smears and with no history of recent malarial infection were included in the study. Sera were also obtained from 15 randomly chosen adults living in the area and without a recent history of fever or other signs of acute malarial infection.

In both areas, informed consent was obtained from the patients and/or their parents. Ethical clearance was given by appropriate bodies at the International Foundation of the Albert Schweitzer Hospital and the Kenya Medical Research Institute. Both Kenyan and Gabonese sera were stored in −70°C and heat inactivated at 56°C before use in the assays. Control sera were obtained from healthy Swedish blood donors. Hyperimmune serum from a Liberian donor (BD245) was also used.

Human serum IgG.

IgG was extracted from some of the patient sera by using protein A-Sepharose as described elsewhere (51).

Parasites.

Blood was drawn from the individuals included in the studies. Parasites were cultivated according to standard procedures as described elsewhere (14). Fifteen fresh and rosetting P. falciparum isolates were obtained from Gabonese patients with signs and symptoms of acute malaria. Assays were performed when the parasites had reached the trophozoite stage during the first cycle in culture. Gabonese isolate G168 was stored in liquid nitrogen before use in the second set of assays. In addition, two highly rosetting laboratory-propagated P. falciparum strains and clones were used for testing the Kenyan sera: FCR3S1, derived from strain FCR3 (formerly known as R+PA1) and TM284 (isolated in Thailand). Only blood group O RBC were used in the assays.

Rosette disruption assay.

Aliquots (12.5 to 25 μl) of parasite cultures (FCR3S1, TM284, and wild isolates) were mixed with equal amounts of human sera diluted in RPMI 1640 at end dilutions of 1:10 (Kenyan sera) and 1:5 (Gabonese sera) in a 96-well microtiter plate. After incubation for 30 min at 37°C, rosetting was assessed as described previously (14). In brief, the rosetting rate, expressed as the number of infected RBC in rosettes relative to the total number of late-stage-infected RBC, was compared to the rosetting rate of culture mixed with controls.

Agglutination assay.

Agglutination of PRBC was assayed as described by Aguiar et al. (1), with some modifications. PRBC cultured to late trophozoite and/or early schizont stages were washed three times in malaria culture medium (RPMI 1640-HEPES, 25 mM sodium bicarbonate, 10 μg of gentamicin per ml) and then resuspended at 20% hematocrit. Aliquots of 25 μl were dispensed in polystyrene round-bottom tubes. An equal volume of prediluted serum (end dilutions of 1:10 and 1:5) was added to the parasite culture. The PRBC-serum mixture was then incubated at 37°C for 1 h with constant rotation at 3 rpm. From each polystyrene tube, an aliquot mixed with a small amount of acridine orange was mounted on a glass slide and 50 consecutive fields of vision were counted diagonally, using a 40× lens and incident UV light microscopy as described elsewhere (14). Control sera from healthy Swedish blood donors or from a Liberian hyperimmune donor were used. Results of the agglutination assay were scored on a semiquantitative scale as negative (no agglutinates of ≥4 PRBC), 1+ (1 to 5 agglutinates of 4 to 10 PRBC), 2+ (>5 agglutinates of 4 to 10 PRBC or 1 to 5 agglutinates of 11 to 20 PRBC), 3+ (>5 agglutinates of 11 to 20 PRBC or 1 to 5 agglutinates of >20 PRBC), or 4+ (>5 agglutinates of >20 PRBC).

RESULTS

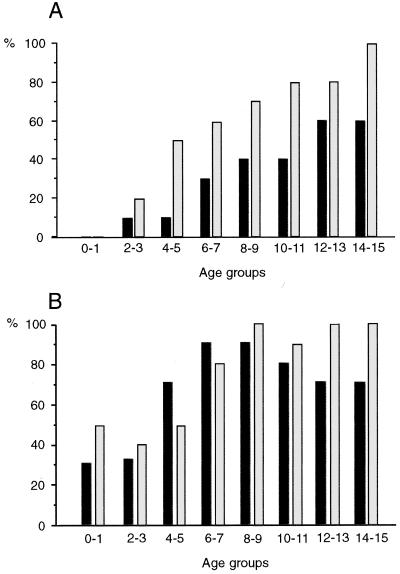

When sera from Kenyan children were tested against the two laboratory strains and clones, we found a significant correlation between various age groups of children and the occurrence of antirosetting serum activity in each group (FCR3S1, r = 0.98; TM284, r = 0.96 [Fig. 1A]). While no children below 2 years of age exhibited ≥50% antirosetting serum activity, a high percentage of children ≥14 years of age had such activity: 60% against strain FCR3S1 and 100% against TM284.

FIG. 1.

Percentage of Kenyan individuals in each age group exhibiting ≥50% antirosetting serum activity (A) and agglutination (≥1+ on the semiquantitative scale) (B) toward the P. falciparum laboratory strain FCR3S1 (■) or TM284 (░⃞). Sera from 22 to 24 individuals in each age group were tested in assays performed as indicated in Materials and Methods.

A positive agglutination activity, defined as ≥1+ on the semiquantitative scale, was found in many individuals in the lower age groups and increased to 75 to 80% (for FCR3S1) and 100% (for TM284) of individuals ≥12 years. When strain TM284 was tested, a strong and significantly positive correlation between age and the agglutinating ability of the sera was exhibited (r = 0.78 [Fig. 1B]). For strain FCR3S1, on the other hand, a steep increase of the number of sera with positive agglutinating activity was found in children up to 8 to 9 years of age, followed by a steady state of somewhat lower percentages at higher ages (10 to 15 years; [Fig. 1B]). Even though both phenomena were significantly correlated with age, only a weak or even no correlation was found between the expression of antirosetting activity and agglutination on an individual level (FCR3S1, r = 0.52; TM284, r = 0.36). Similarly, only a weak correlation was found between the responses of the two strains tested; i.e., a serum with high antirosetting activity toward TM284 did not necessarily react to FCR3S1, and vice versa. The same was true for agglutination (data not shown).

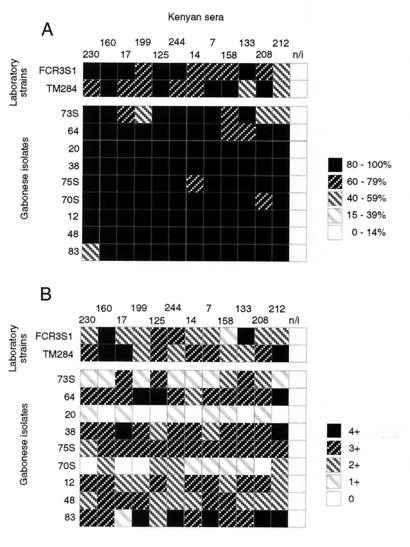

Twelve sera from Kenyan adolescents, selected for high antirosetting activity against any or both of the two laboratory strains and for a positive agglutinating response, were tested against Gabonese P. falciparum isolates. A similarly good and uniform recognition of rosetting epitopes in the Gabonese isolates was found, indicating extensive recognition by these sera of (all) rosetting epitopes in another geographical area of Africa (Fig. 2A). Also, the agglutinating activity was strong but more diverse, and two Gabonese isolates were poorly recognized by many Kenyan sera (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Sera from 12 Kenyan children selected for high antirosetting activity tested against nine Gabonese P. falciparum isolates for antirosetting (A) and agglutinating (B) activities. Antirosetting activity (percent inhibition of rosetting) and agglutinating activity (for semiquantitative scoring scale, see Materials and Methods) are depicted in a five-level grey scale as indicated. A serum obtained from a nonimmune Swede (n/i) was used as a control.

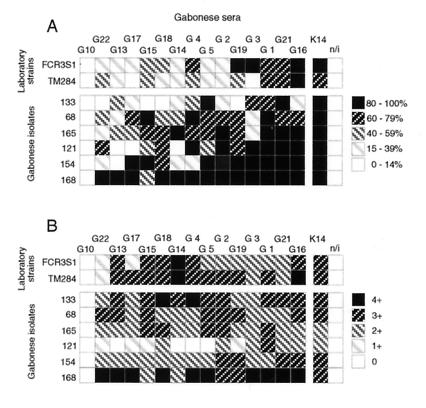

Similar but “reverse” crossover testing was done with 15 randomly selected Gabonese adults against the two laboratory strains used in Kenya (FCR3S1 and TM284) and against six wild isolates obtained in Gabon (Fig. 3). The antirosetting activity against the two laboratory strains was less intense than expected for similar groups in Kenya, while the agglutinating activity was more uniform and similar to the results obtained in Kenya. Fourteen of the fifteen Gabonese sera tested had an effect (≥15% rosette reversion) on most strains and isolates tested, and seven of the tested sera exhibited an antirosetting effect on all isolates. The different isolates varied in their recognition by the different sera, but in general the sera exhibited greater activity against the six wild isolates than against the two laboratory test strains. The agglutinating pattern was more uniform, with no significant differences between wild isolates and laboratory strains, nor was there any obvious correlation between antirosetting and agglutinating activities. One individual, an adult of Gabonese origin, was totally negative for both antirosetting and agglutinating activities toward all strains and isolates.

FIG. 3.

Sera from 15 Gabonese adults tested against the two laboratory strains FCR3S1 and TM284 and against six Gabonese P. falciparum isolates for antirosetting (A) and agglutinating (B) activities. Antirosetting activity (percent inhibition of rosetting) and agglutinating activity (for semiquantitative scoring scale, see Materials and Methods) are depicted in a five-level grey scale as indicated. A highly rosette disrupting and agglutinating Kenyan serum (K14) and serum obtained from a nonimmune Swede (n/i) were used as controls.

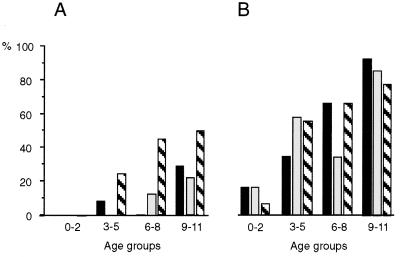

Finally, when a lower number of sera from Gabonese children were tested against the two laboratory strains and clones and against a Gabonese isolate (G168), the buildup of agglutinating activity was similar to that seen in the Kenyan samples (Fig. 4B). However, a much weaker buildup of antirosetting activity was found toward the two laboratory strains (Fig. 4A). In the highest age group, 9 to 11 years, only 30% of the children exhibited activity toward either of the two strains. However, when an isolate (G168) obtained in Gabon was used, more than 55% in the higher age groups exhibited high (≥50%) antirosetting activity, and there was no significant individual correlation between highly antirosetting activity and agglutinating activity (r = 0.48).

FIG. 4.

Percentage of Gabonese individuals in each age group

exhibiting ≥50% antirosetting serum activity (A) and agglutination

(≥1+ on the semiquantitative scale) (B) toward the P.

falciparum laboratory strain FCR3S1 (■) or TM284 (░⃞) and

toward the Gabonese isolate G168

( ). Sera

from 10 to 14 individuals in each age group were tested.

). Sera

from 10 to 14 individuals in each age group were tested.

Both the antirosetting activity and the ability to agglutinate PRBC were always contained in the immunoglobulin fraction when sera were fractionated on protein A-Sepharose.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have shown an age-related increase of agglutinating activity in sera from children living in areas of Africa where malaria is endemic. Even though only two laboratory strains were used for testing, our results correspond well with those of previous studies that established a correlation between antibodies to surface-exposed antigens and immunity to malaria (34). Even more interesting, however, is the age-related buildup of serum activity against rosette formation seen in children living in areas of both Kenya and Gabon where malaria is endemic. Since both the antirosetting activity and the ability to agglutinate PRBC were always contained in the immunoglobulin fraction when serum and plasma samples were fractionated on protein A-Sepharose, we believe the activity to be antibody mediated rather than an effect of other serum components.

In areas with relatively high malarial transmission such as Kisumu and (to a somewhat lesser extent) Lambaréné, severe anemia is a common complication among young children but decreases with age (7, 12, 28). In other areas, cerebral malaria is the dominating severe complication in childhood. We have previously shown an association between rosetting and cerebral malaria and that protection against cerebral malaria correlates with the presence of antirosetting antibodies in serum (13, 46). Recently a similar association between rosetting and anemia was reported (39). These data exhibiting an age-related buildup of antirosetting antibodies are thus well in accordance with previous reports on rosetting and consistent with the clinical situation where a gradual acquisition of immunity toward severe complications of P. falciparum infection is seen in children reared in areas of endemicity.

In Gabon, this buildup of humoral immunity could be seen only when a locally obtained wild isolate was used, and the response to the two laboratory strains was much less pronounced than in Kenya. This somewhat weaker response was confirmed when sera from Gabonese adults were tested against indigenous isolates. While the recognition of rosetting epitopes in some isolates was high, the response toward other isolates was weaker and more diverse. In addition, sera from Kenyans with high antirosetting activity also recognized all of the Gabonese strains against which they were tested. This discrepancy may reflect a difference in transmission patterns between the two areas. Malaria is holoendemic in the Kisumu area, with peak entomological inoculation rates of one infective bite per person every two nights (4) and 85 to 95% P. falciparum prevalence during the high-transmission season in April (3). The transmission in the Lambaréné area is less intense, with seasonal variations and peak P. falciparum prevalence of 50 to 60% in November (30, 55).

The difference in response between the various P. falciparum strains and isolates tested probably reflects the high degree of serotypical and cytoadherent hypervariability of surface-exposed P. falciparum induced antigens, in particular PfEMP1, known to exist (19, 23, 27, 33) as well as the variability in the expression of rosetting ligands (rosettins) previously described (14, 21, 24, 52).

Antigenic variation is, indeed, a feature of the parasite worldwide (1, 11, 38, 49). Our results indicate that repeated malaria attacks in areas of endemicity, and consequently exposure to different isolate-specific antigens, will elicit an antibody-mediated response eventually enabling recognition of the majority of rosetting and agglutinating antigens. This age-related immune response may contribute to protective immunity.

Interestingly, antirosetting activity correlated poorly with agglutinating activity in individual sera. Other investigators have found a weak correlation between the two activities among highly exposed adults (42). Recent in vitro findings indicate that both rosetting and cytoadherence properties may well be linked to the same family of molecules, PfEMP1 (2, 15, 44, 45). Though PfEMP1 was first ascribed importance only for cytoadherence and serotypical variation, very recent studies have reported evidence that PfEMP1 is also involved in rosetting. We have provided evidence that PfEMP1 can bind to heparan sulfate, an interaction that proved to be sensitive to disruption with heparin as well as with heparan sulfate but not with other glycosaminoglycans tested (15). In another study that ascribed to PfEMP1 importance for rosetting, it was found that complement receptor 1 constituted the ligand on noninfected RBC (44). The weak correlation, or even absence of correlation, between antirosetting activity and agglutinating capacity found in this (and other) studies is not necessarily in contrast with the in vitro findings but may well be explained by the fact that the rosetting epitopes are only part of the highly diverse PfEMP1 molecule and thus only a minor part of the highly diverse surface-exposed antigens on the surface of parasitized erythrocytes toward which antibodies may react.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all persons participating in this study, the staff at KEMRI, Kisumu, Kenya, and Laboratoire de Recherches, Hôpital du Docteur Albert Schweitzer, Lambaréné, Gabon, for invaluable help, L. Gregory for skillful technical assistance, and M. Schlichtherle for editorial comments.

This study was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council and the Swedish Society of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguiar J C, Albrecht G R, Cegielski P, Greenwood B M, Jensen K B, Lallinger G, Martinez A, McGregor I A, Minjas J N, Neequaye J, Patarroyo M E, Sherwood J A, Howard R J. Agglutination of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes from East and West African isolates by human sera from distinct geographic regions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:621–632. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baruch D I, Pasloske B L, Singh H B, Bi X, Ma X C, Feldman M, Taraschi T F, Howard R J. Cloning the P. falciparumgene encoding PfEMP1, a malarial variant antigen and adherence receptor on the surface of parasitized human erythrocytes. Cell. 1995;82:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beach R F, Ruebush T K, Sexton J D, Bright P L, Hightower A W, Breman J G, Mount D L, Oloo A J. Effectiveness of permethrin-impregnated bed nets and curtains for malaria control in a holoendemic area of Western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:290–300. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beier J C, Perkins P V, Onyango F K, Gargan T P, Oster C N, Whithmire R E, Koech D K, Roberts C R. Characterization of malaria transmission by Anopheles (Diptrea: Culicidae) in Western Kenya in preparation for malaria vaccine trials. J Med Entomol. 1990;27:570–577. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/27.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berendt A R, Ferguson D J P, Newbold C I. Sequestration in Plasmodium falciparummalaria: sticky cells and sticky problems. Parasitol Today. 1990;6:247–254. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(90)90184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biggs B-A, Gooze L, Wycherley K, Wollish W, Southwell B, Leech J H, Brown G V. Antigenic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9171–9174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branch O H, Udhayakumar V, Hightower A W, Oloo A J, Hawley W A, Nahlen B L, Bloland P B, Kaslow D C, Lal A A. A longitudinal investigation of IgG and IgM antibody responses to the merozoite surface protein-1 19-kiloDalton domain of Plasmodium falciparumin pregnant women and infants: association with febrile illness, parasitemia and anemia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:211–219. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brasseur P, Ballet J J, Druilhe P. Impairment of Plasmodium falciparum-specific antibody response in severe malaria. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:265–268. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.265-268.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown K N, Brown I N. Immunity to malaria: antigenic variation in chronic infections of Plasmodium knowlesi. Nature. 1965;208:1286–1288. doi: 10.1038/2081286a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruce-Chwatt L J. Malaria in African infants and children in southern Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1952;46:173–200. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1952.11685522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bull P C, Lowe B S, Kortok M, Molyneux C S, Newbold C I, Marsh K. Parasite antigens on the infected red cell surface are targets for naturally acquired immunity to malaria. Nat Med. 1998;4:358–360. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burchard G D, Radloff P, Philipps J, Knobloch J, Kremsner P G. Increased erythropoietin production in children with severe malarial anemia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:547–551. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson J, Helmby H, Hill A V, Brewster D, Greenwood B M, Wahlgren M. Human cerebral malaria: association with erythrocyte rosetting and lack of anti-rosetting antibodies. Lancet. 1990;336:1457–1460. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93174-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson J, Holmquist G, Taylor D W, Perlmann P, Wahlgren M. Antibodies to a histidine-rich protein (PfHRP1) disrupt spontaneously formed Plasmodium falciparumerythrocyte rosettes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2511–2515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Q, Barragan A, Fernandez V, Sundström A, Schlichtherle M, Sahlén A, Carlson J, Datta S, Wahlgren M. Identification of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) as the rosetting ligand of the malaria parasite P. falciparum. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen S, Lambert P H. Malaria. In: Cohen S, Warren D, editors. Immunology of parasitic infections. 2nd ed. London, England: Blackwell; 1982. pp. 422–438. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen S, McGregor I A, Carrington S. Gammaglobulin and acquired immunity to human malaria. Nature. 1961;192:733–737. doi: 10.1038/192733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erunkulu O A, Hill A V, Kwiatkowski D P, Todd J E, Iqbal J, Berzins K, Riley E M, Greenwood B M. Severe malaria in Gambian children is not due to lack of previous exposure to malaria. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;89:296–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forsyth K P, Philip G, Smith T, Kum E, Southwell B, Brown G V. Diversity of antigens expressed on the surface of the erythrocytes infected with mature Plasmodium falciparumparasites in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;41:259–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Handunnetti S M, David P H, Perera K L R L, Mendis K N. Uninfected erythrocytes from “rosettes” around Plasmodium falciparuminfected erythrocytes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:115–118. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Handunnetti S M, Gilladoga A D, van Schravendijk M-R, Nakomura K, Aikawa M, Howard R J. Purification and in vitro selection of rosette-positive (R+) and rosette-negative (R−) phenotypes of knob-positive Plasmodium falciparumparasites. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:371–381. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handunnetti S M, Mendis K N, David P H. Antigenic variation of cloned Plasmodium fragile in its natural host Macaca sinica. Sequential appearance of successive variant antigenic types. J Exp Med. 1987;165:1269–1283. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.5.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasler T, Handunetti S H, Aguiar J C, van Schravendijk M R, Greenwood B M, Lallinger G, Cegielski P, Howard R J. In vitro rosetting, cytoadherence, and microagglutination of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes from Gambian and Tanzanian patients. Blood. 1990;76:1845–1852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helmby H, Cavelier L, Petterson U, Wahlgren M. Rosetting Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes express unique antigens on their surface. Infect Immun. 1993;61:284–288. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.284-288.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hommell M, David P H, Oligino L D. Surface alterations of erythrocytes in Plasmodium falciparummalaria. Antigenic variation, antigenic diversity and the role of the spleen. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1137–1148. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.4.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hommel M, Semoff S. Expression and function of erythrocyte-associated surface antigens in malaria. Biol Cell. 1988;64:183–203. doi: 10.1016/0248-4900(88)90078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iqbal J, Perlmann P, Berzins K. Serologic diversity of antigens expressed on the surface of Plasmodium falciparuminfected erythrocytes in Punjab (Pakistan) Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:583–588. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90097-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitua A Y, Smith T A, Alonso P L, Urassa H, Masanja H, Kimario J, Tanner M. The role of low level Plasmodium falciparum parasitemia in anaemia among infants living in an area of intense and perennial transmission. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:325–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.1997.tb00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kun J, Schmidt-Ott R, Lehman L, Lell B, Luckner D, Greve B, Matousek P, Kremsner P. Merozoite surface antigen 1 and 2 genotypes and rosetting of Plasmodium falciparum in severe and mild malaria in Lambaréné, Gabon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:110–114. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)90979-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lell B, Luckner D, Ndjavé M, Scott T, Kremsner P. Randomised placebo-controlled study of atovaquone and proguanil for malaria prophylaxis. Lancet. 1998;351:709–713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucas A O, Hendrickse R G, Okubadejo O A, Richards W H G, Neal R A, Kofie B A K. The suppression of malarial parasitaemia by pyrimethamine in combination with dapsone or sulphormethoxine. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1969;63:216–229. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(69)90150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magowan C, Wollish W, Anderson L, Leech J. Cytoadherence by Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes is correlated with the expression of a family of variable proteins on infected erythrocytes. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1307–1320. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.4.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marsh K, Howard R J. Antigens induced on erythrocytes by P. falciparum: expression of diverse and conserved determinants. Science. 1986;231:150–153. doi: 10.1126/science.2417315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsh K, Otoo L, Hayes R J, Carson D C, Greenwood B M. Antibodies to blood stage antigens of Plasmodium falciparumin rural Gambians and their relation to protection against infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:293–303. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLean S A, Pearson C D, Phillips R S. Plasmodium chabaudi: evidence of antigenic variation during recrudescent parasitaemias in mice. Exp Parasitol. 1982;54:296–302. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(82)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller L H, Aikawa M, Dvorak J A. Malaria (Plasmodium knowlesi) merozoites: immunity and the surface coat. J Immunol. 1975;114:1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neva F A. Looking back for a view of the future: observations of immunity to induce malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1977;26:211–215. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1977.26.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newbold C I, Pinches R, Roberts D J, Marsh K. Plasmodium falciparum: the human agglutinating antibody response to the infected red cell surface is predominantly variant specific. Exp Parasitol. 1992;75:281–292. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90213-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newbold C I, Warn P, Black G, Berendt A, Craig A, Snow B, Msobo M, Peshu N, Marsh K. Receptor-specific adhesion and clinical disease in Plasmodium falciparum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:389–398. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ringwald P, Peyron F, Lepers J P, Rabarison P, Rakotomalala C, Razanamparany M, Rabodonirina M, Roux J, Le Bras J. Parasite virulence factors during falciparum malaria: rosetting, cytoadherence, and modulation of cytoadherence by cytokines. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5198–5204. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5198-5204.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts D J, Craig A G, Berendt A R, Pinches R, Nash G, Marsh K, Newbold C I. Rapid switching to multiple antigenic and adhesive phenotypes in malaria. Nature. 1992;357:689–692. doi: 10.1038/357689a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rogerson S J, Beck H P, Al-Yaman F, Currie B, Alpers M P, Brown G V. Disruption of erythrocyte rosettes and agglutination of erythrocytes infected with Plasmodium falciparum by the sera of Papua New Guineans. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:80–84. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90487-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rowe A, Obeiro J, Newbold C I, Marsh K. Plasmodium falciparumrosetting is associated with malaria severity in Kenya. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2323–2326. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2323-2326.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rowe J A, Moulds J M, Newbold C I, Miller L H. P. falciparumrosetting mediated by a parasite-variant erythrocyte membrane protein and complement-receptor 1. Nature. 1997;388:292–295. doi: 10.1038/40888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith J D, Chitnis C E, Craig A G, Roberts D J, Hudson-Taylor D, Peterson D S, Pinches R, Newbold C I, Miller L H. Switches in expression of Plasmodium falciparumvar genes correlate with changes in antigenic and cytoadherent phenotypes of infected erythrocytes. Cell. 1995;82:101–110. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90056-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Treutiger C J, Hedlund I, Helmby H, Carlson J, Jepson A, Twumasi P, Kwiatkowski D, Greenwood B M, Wahlgren M. Rosette formation in Plasmodium falciparumisolates and anti-rosette activity of sera from Gambians with cerebral or uncomplicated malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:503–510. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Udeinya I J, Miller L H, McGregor I A, Jensen J B. Plasmodium falciparumstrain-specific antibody blocks binding of infected erythrocytes to amelanotic melanoma cells. Nature. 1983;303:429–431. doi: 10.1038/303429a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Udomsangpetch R, Wåhlin B, Carlson J, Berzins K, Torii M, Aikawa M, Perlmann P, Wahlgren M. Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes form spontaneous erythrocyte rosettes. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1835–1840. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.5.1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Schravendijk M-R, Rock E P, Marsh K, Ito Y, Aikawa M, Neequaye J, Ofori-Adjei D, Rodriguez R, Patarroyo M E, Howard R J. Characterization and localization of Plasmodium falciparumsurface antigens on infected erythrocytes from West African patients. Blood. 1991;78:226–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wahlgren M. Doctoral thesis. Stockholm, Sweden: Karolinska Institutet; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wahlgren M, Carlson J, Ruangjirachuporn W, Conway D, Helmby H, Patarroyo M E, Martinez A, Riley E. Geographical distribution of Plasmodium falciparumerythrocyte rosetting and frequency of rosetting antibodies in human sera. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;43:333–338. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.43.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wahlgren M, Fernandez V, Scholander C, Carlson J. Rosetting. Parasitol Today. 1994;10:73–79. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wåhlin B, Wahlgren M, Perlmann H, Berzins K, Björkman A, Patarroyo M E, Perlmann P. Human antibodies to a Mr 155,000 Plasmodium falciparumantigen efficiently inhibiting merozoite invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:7912–7916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.24.7912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilding E, Winkler S, Kremsner P G, Brandts C, Jenne L, Wernsdorfer W H. Malaria epidemiology in the province of Moyen Ogooué, Gabon. Trop Med Parasitol. 1995;46:77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.World Health Organization. 1990. Severe and complicated malaria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 84:(Suppl. 2):1–65. [PubMed]