Abstract

Purpose:

Among patients with upper abdominal malignancies, intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) can improve dose distributions to critical dose-limiting structures near the target. Whether these improved dose distributions are associated with decreased toxicity when compared with conventional three-dimensional treatment remains a subject of investigation.

Methods and Materials:

46 patients with pancreatic/ampullary cancer were treated with concurrent chemoradiation (CRT) using inverse-planned IMRT. All patients received CRT based on 5-fluorouracil in a schema similar to Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 97–04. Rates of acute gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity for this series of IMRT-treated patients were compared with those from RTOG 97–04, where all patients were treated with three-dimensional conformal techniques. Chi-square analysis was used to determine if there was a statistically different incidence in acute GI toxicity between these two groups of patients.

Results:

The overall incidence of Grade 3–4 acute GI toxicity was low in patients receiving IMRT-based CRT. When compared with patients who had three-dimensional treatment planning (RTOG 97–04), IMRT significantly reduced the incidence of Grade 3–4 nausea and vomiting (0% vs. 11%, p = 0.024) and diarrhea (3% vs. 18%, p = 0.017). There was no significant difference in the incidence of Grade 3–4 weight loss between the two groups of patients.

Conclusions:

IMRT is associated with a statistically significant decrease in acute upper and lower GI toxicity among patients treated with CRT for pancreatic/ampullary cancers. Future clinical trials plan to incorporate the use of IMRT, given that it remains a subject of active investigation.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Intensity-modulated radiation therapy, Toxicity

INTRODUCTION

Treating pancreatic cancer remains a significant therapeutic challenge. Among the approximately 38,00 cases diagnosed in the United States each year, about 20% of patients are able to undergo the only known curative treatment: definitive surgical resection. Among the 20% of patients who undergo resection, the 5-year survival remains dismal, at approximately less than 20%.

Adjuvant therapy (radiation or chemotherapy) for pancreatic cancer has been the subject of intense clinical investigation for several decades. Although some controversy over the effectiveness of adjuvant chemoradiation (CRT) for pancreatic cancer exists in the literature, adjuvant CRT remains a standard of care for patients who have undergone surgical resection of pancreatic cancer in the United States. Patients with localized but unresectable disease are also offered CRT, with the goal of either rendering the tumor operable or improving local control. One of the major challenges of administering radiation to the upper abdomen in either the postoperative or neoadjuvant setting is the presence of multiple critical structures in the immediate vicinity of the pancreas, including the liver, kidneys, stomach, small bowel, and spinal cord. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) has been shown to reduce dose to critical dose-limiting structures in the upper abdomen. Whether these improved dose distributions are associated with decreased clinical toxicity when compared with conventional three-dimensional (3-D) treatment remains a subject of ongoing research.

This analysis evaluates acute toxicity outcomes at two university hospitals (the University of Maryland Medical Center and the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey) and compares these data with toxicity results from the recently reported US Intergroup adjuvant CRT trial (Radiation Therapy Oncology Group [RTOG] 97–04), where all patients were treated with conventional 3-D planning techniques (1).

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Data collection and analysis

Patient charts were retrospectively reviewed under a protocol approved by both departments’ institutional review boards. Information on toxicities was collected from a review of weekly physician under-treatment notes. Patients were asked a standard set of questions on a weekly basis, including the incidence and severity of nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and diarrhea. The use of antiemetics and antidiarrheal medication was documented on separate medication flowsheets that were updated weekly. Any use of intravenous fluids was also documented in the chart on separate physician order sheets. Patients were also weighed at least once per week during treatment. All patients had provided informed consent for treatment. Data was collected on patients’ weights at the beginning and end of treatment, total treatment time/requirement for treatment breaks, and the incidence and grade of gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity from the start of concurrent CRT until 1 month after completion of CRT. Toxicities were graded using the NCI Common Toxicity Criteria. The rate of toxicities among patients receiving IMRT-planned CRT was then compared with the rate of acute GI toxicities reported by the RTOG for patients treated under protocol 97–04 with 3-D conformal plans. Fisher’s exact test was used to determine if there was a statistically different incidence in acute GI toxicity between the patients treated with IMRT-based CRT and those treated using conventional 3-D planning. It was considered that p values ≤0.05 were statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to generate data on overall and progression-free survival.

Patient demographics

In all, 46 patients are included in this report: 53% were male, and the median age was 62 years (range, 35–83 years). As for treatment, 67% (n = 31) of patients were treated after undergoing definitive surgical resection; the remainder had nonmetastatic but locally advanced disease. Table 1 shows further details of patient demographics and staging.

Table 1.

Demographics and staging

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Sex | |

| M | 24 (52) |

| F | 22 (48) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Pancreas | 41 (89) |

| Ampulla | 5(11) |

| T stage | |

| T1 | 2 (4) |

| T2 | 10 (22) |

| T3 | 19 (41) |

| T4 | 15 (33) |

| N stage | |

| Node negative | 18 (39) |

| Node positive | 19 (41) |

| Unknown | 9 (20) |

Treatment regimen

All patients received 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)–based concurrent CRT therapy with either capecitabine (750–825 mg/m2, divided in twice-daily doses and given Monday through Friday with radiation treatment) or infusional 5-FU (250 mg/m2 daily throughout radiation treatments). The majority of patients received one to two cycles of gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2 weekly for 3 to 7 weeks) before beginning concurrent CRT in a schema similar to the recently reported adjuvant pancreas trial, RTOG 97–04. Patients received further treatment with gemcitabine after completing concurrent CRT at the discretion of the treating medical oncologist. Median radiation dose was 50.4 Gy given in 28 1.8-Gy fractions; patients with unresectable disease (n = 15) or positive margins (n = 8) received higher doses (54–59.4 Gy).

Radiation therapy planning

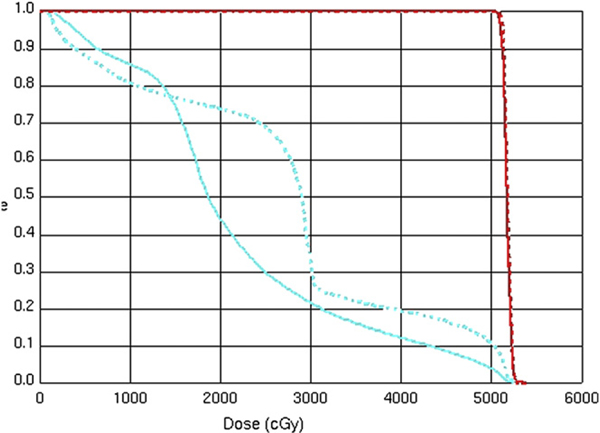

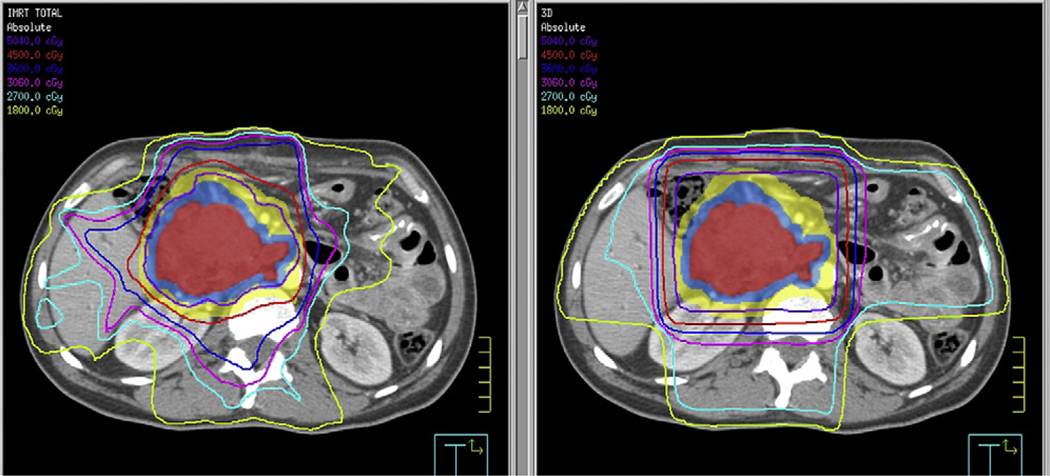

All patients underwent computed tomography (CT)-guided simulation with intravenous and oral contrast media. Four-dimensional CT planning techniques were not routinely used for the cohort of patients in this report. Preoperative CT scans were used to aid in the delineation of the tumor bed. Treatment volumes were constructed according to the same guidelines used to construct the 3-D fields used in RTOG 97–04. The initial treatment field was based on either gross tumor volume (unresectable patients) or clinical tumor volume (postoperative patients), including the celiac, peripancreatic, pancreatico-duodenal, portahepatic, and para-aortic lymph node basins extending from approximately T10 through L3. Margins of 1 to 1.5 centimeters were added in all dimensions, with the final planning target volume (PTV) modified clinically by the treating physician. This volume was prescribed 45 Gy. Inverse-planned IMRT was used to generate optimized treatment plans for each patient. Small field boosts were also designed using inverse planning and included either gross tumor volume or tumor bed plus a 1- to 1.5-cm margin and were treated to an additional 5.4–14.4 Gy. Small bowel volumes were generated by contouring individual loops of bowel with the aid of an orally administered iodine contrast agent. Table 2 shows the normal tissue constraints used for the IMRT plans. Figure 1 is a sample dose–volume histogram depicting the ability of IMRT to reduce total dose to critical structures in the upper abdomen. Figure 2 shows dose distributions in the axial plane for a representative IMRT plan compared with a conventional 3-D plan.

Table 2.

Dose constraints used in IMRT treatment planning

| Organ | Volume | Dose |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Ipsilateral kidney | 33% | <18 Gy |

| Contralateral kidney | 66% | <18 Gy |

| Bowel | 5% | <54 Gy |

| 10% | <50 Gy | |

| 15% | <45 Gy | |

| 50% | <20 Gy | |

| Spinal cord | Maximum dose | 45 Gy |

| Liver | 60% | <30 Gy |

Abbreviation: IMRT = intensity-modulated radiation therapy.

Fig. 1.

Representative dose–volume histogram comparing three-dimensional conformal and intensity-modulated radiation therapy plans.

Fig. 2.

Axial comparison of typical intensity-modulated radiation therapy (left) and three-dimensional (right) treatment plans.

RESULTS

Acute and late toxicity

Median treatment time was 39 days, with only 1 patient requiring a prolonged (>4-day) treatment break. Five patients required a treatment break; 3 patients required a 1-day break, 1 patient required a 4-day break, and another patient required a 7-day break. Median weight loss among IMRT patients was 3% (range, 0–10%). The overall incidence of severe (Grade 3–4) acute GI toxicity was low in patients receiving IMRT-based CRT. Within the entire cohort of patients, IMRT significantly reduced the incidence of Grade 3–4 nausea and vomiting (0% vs. 11%, p = 0.024) and diarrhea (3% vs 18%, p = 0.017). The incidence of Grade 3–4 anorexia was low (<5%) in both groups analyzed. Table 3 shows the rates of acute GI toxicity among patients in this series.

Table 3.

Incidence of acute Grade 3–4 gastrointestinal toxicity among patients treated with IMRT versus 3-D conformal treatment plans

| Toxicity | 3-D conformal n (%) | IMRT n (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Nausea/vomiting | |||

| Grade 0–2 | 402 (89) | 46 (100) | 0.016 |

| Grade 3–4 | 49 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| Diarrhea | |||

| Grade 0–2 | 373 (83) | 44 (96) | 0.02 |

| Grade 3–4 | 78 (17) | 2 (4) | |

| Anorexia | |||

| Grade 0–2 | 442 (98) | 44 (96) | > 0.05 |

| Grade 3–4 | 9 (2) | 2 (4) | |

Abbreviations: IMRT = intensity-modulated radiation therapy; 3-D = three dimensional.

Two late toxicities were observed in this cohort of patients. One patient developed an acute small bowel obstruction associated with an incarcerated intraabdominal hernia and peritoneal adhesions approximately 1 year after completing adjuvant CRT. The bowel obstruction was treated surgically and the patient recovered; however, she developed peritoneal carcinomatosis approximately 3 months after her bowel obstruction was treated. Another patient developed an acute small bowel obstruction approximately 2 months after completing CRT. This was successfully treated surgically, and the patient is currently alive without evidence of disease recurrence.

Survival

At a median follow-up of 22 months, median survival among resectable patients was 24.8 months and median progression-free survival was 17.5 months. Median overall survival for patients with unresectable disease was 9.7 months.

DISCUSSION

The primary advantage of IMRT when compared with 3-D conformal radiation treatment planning is its ability to generate highly conformal treatment plans, which can theoretically deliver a high tumor dose while sparing nearby critical structures. IMRT planning techniques have facilitated dose escalation in prostate cancer (2) and have been shown to improve toxicity profiles in head and neck cancer (3, 4). Limiting treatment-related toxicity is particularly important among patients with pancreatic cancer, given the historically poor survival outcomes in this disease; one of the major goals of treatment is optimizing quality of life in addition to maximizing tumor control.

The primary abdominal radiation dose-limiting structure is the bowel. The risk of toxicity rises with both total dose and total volume of small bowel radiation, although the exact dose–volume relationship is difficult to quantify. Acute toxicity involving the small bowel is related to radiation-induced epithelial damage and typically manifests primarily as diarrhea, whereas acute toxicity involving the stomach typically presents as nausea or vomiting. This toxicity is potentiated by 5-FU–based chemotherapy, and in severe cases may significantly prolong treatment times and/or prevent patients from completing their planned course of treatment. Late toxicities of small bowel irradiation include obstruction, stricture, and fistula formation related to radiation-induced small vessel damage and chronic ischemia, and also the formation of fibrotic scar tissue within the peritoneum. Rates of acute bowel toxicity seem to be similar among postoperative and unresected patients. For example, in the report by Ben-Josef et al. of 15 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma (7 adjuvant and 8 unresectable patients) who received concurrent gemcitabine and IMRT-planned radiation therapy, no difference in the rates of acute or late GI toxicity was reported among postoperative compared to intact-pancreas patients (8). Although this series is not directly comparable to our report in that gemcitabine rather than capecitabine was used as the chemotherapy agent, another series from M.D. Anderson, utilizing concurrent capecitabine and 3-D conformal radiotherapy for 88 patients (24 postoperative and 64 intact-pancreas) also did not report any difference in toxicity between the resected and unresectable patients. Similarly, our data do not show any difference in the incidence of acute GI toxicity between these two groups of patients. This served as a rationale for combining these two groups to increase the statistical power of our comparison with the RTOG 97–04 series.

Multiple single-institution reports discuss the ability of IMRT techniques to reduce dose to critical structures and report relatively low acute clinical toxicity in patients with upper abdominal malignancies. A recent article by van der Geld et al. compared a nonparallel (but coplanar) 3-D conformal beam arrangement with an IMRT plan in a group of 10 patients who underwent respiratory-gated CT simulation. The investigators found that IMRT significantly decreased dose to the small bowel, liver, stomach, and both kidneys (5). Landry et al. demonstrated a 21% reduction in small bowel dose with the use of IMRT (V33 = 38.5 Gy vs. 30.2 Gy) (6). Milano et al. published a series of 25 patients with pancreatic or bile duct primaries from the University of Chicago (7). In this series, patients were treated with continuous-infusion 5-FU and concurrent radiation to a median dose of 50.4 Gy. The IMRT plans were shown to significantly reduce radiation dose to the kidney and small bowel when compared with 3-D plans. Four Grade 3 and two Grade 4 acute GI toxicities were reported in this series, which did not have a 3-D arm for comparison. Ben-Josef et al. reported on 15 patients treated at the University of Michigan with concurrent capecitabine and IMRT-planned external beam radiation to a median dose of 54 Gy (8). A single patient developed Grade 3 toxicity (gastric ulcer); no patient in this series had a Grade 4 toxicity. In all these series, the theoretical concern of worsening toxicities secondary to larger volumes of bowel receiving low-dose radiation was not corroborated clinically. Mundt et al., in a single-institution retrospective series, reported acute and chronic GI toxicity among patients receiving whole pelvis radiation for gynecologic malignancies (9). Although not directly comparable to patients with upper abdominal cancers, patients undergoing whole pelvis radiation also receive a significant radiation dose to the bowel. In this series, IMRT reduced acute GI toxicity from 91% to 60% (p = 0.002) and reduced the need for antidiarrheal medications from 75% to 34% (p = 0.001). Late GI toxicities were also significantly reduced (54% vs. 11%, p = 0.02).

The series reported here is one of the largest to comparatively evaluate acute GI toxicity with use of IMRT versus 3-D in patients with pancreatic/ampullary cancers. The survival outcomes in this report compare favorably to the 20.5-month median overall survival among patients treated on the gemcitabine arm of RTOG 9704 and to the 22.1-month median overall survival reported in the chemotherapy-only trial CONKO-001 (10). Concurrent IMRT-based CRT was well tolerated in patients with both resected and unresectable pancreatic/ampullary cancers, and the use of this treatment technique successfully reduced the rates of acute severe GI toxicity. The relative uniformity of the treatment plan allowed comparison with a large group of patients treated under a multi-institutional national protocol, and it shows that the toxicity profile of IMRT compares favorably to that of conventional 3-D conformal therapy. An important limitation of the data reported here is that they were collected through a retrospective chart review. This may have led to an under-estimation of the rates of acute toxicity. However, Grade 3–4 GI toxicity typically warrants extended parenteral support and in many cases hospital admission, both of which would have been consistently documented in our data. This may reduce, but does not completely eliminate, the possibility of bias being introduced by the fact that toxicity was reviewed retrospectively.

It is also important to note that fields for pancreatic cancer are not standardized, leading to major differences in field size and dose to normal tissue among plans generated by different radiation oncologists. Smaller planning target volumes could theoretically improve acute toxicity profiles and thus dilute the potential benefit of IMRT. Conversely, the more conformal nature of IMRT plans means that inaccurate PTV definition increases the risk of underdosing the true target and may theoretically increase the risk of marginal treatment failures, especially as planning target volumes shrink. In our cohort of patients, the PTV was deliberately designed to encompass the same target volume as would a conventional 3-D plan, as used in RTOG 9704, aimed at treating a pancreatic tumor bed and the regional lymphatics.

The successor Phase III adjuvant trial to RTOG 9704 will be RTOG 0848. This will be a US Intergroup/EORTC trial evaluating the use of the addition of erlotinib to gemcitabine and also the addition of RT in the postoperative adjuvant setting. This will be the first large Phase III pancreatic cancer trial to allow the use of IMRT. As RTOG has done with use of IMRT in other sites, detailed guidelines inclusive of use of a reference Web-based atlas will facilitate education and quality assurance (QA) related to the use of IMRT. As was done in RTOG 9704, pre-CRT central QA review and approval will be required (11). This trial will also afford the opportunity to investigate the toxicity of IMRT in a prospective fashion. Additional advances in treatment planning techniques, such as the use of four-dimensional CT simulation (5), functional imaging, and magnetic resonance imaging (12), can also help to optimize the definition of target volumes in patients with pancreatic cancer.

CONCLUSIONS

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy is a powerful treatment planning tool, which, when applied carefully, can significantly improve the toxicity of concurrent upper abdominal CRT. This series adds to the existing literature regarding the ability of IMRT to reduce the acute toxicity of concurrent CRT to the upper abdomen. The improved tolerability of treatment not only can improve patients’ quality of life but also may allow for radiation dose escalation and intensification of chemotherapy regimens in an attempt to improve the cure rates of this devastating disease. Investigating the use of IMRT in future pancreatic cancer clinical trials is planned along with detailed QA and associated education of participating radiation oncologists.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Regine WF, Winter K, Abrams R, et al. Fluorouracil vs gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;299:1019–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollack A, Hanlon A, Horowitz EM, et al. Radiation therapy dose escalation for prostate cancer: A rationale for IMRT. World J Urol 2003;21:200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee N, Xia P, Quivey J, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy in the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: An update of the UCSF experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002;53:12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisbruch A, Ten Haken R, Kim H, et al. Dose, volume, and function relationships in parotid salivary glands following conformal and intensity-modulated irradiation of head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999;45:577–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van der Geld Y, van Triest B, Verbakel W, et al. Evaluation of four-dimensional computed-tomography-based intensity-modulated and respiratory-gated radiotherapy techniques for pancreatic carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;72: 1215–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landry JC, Yang GY, Ting JY, et al. Treatment of pancreatic cancer tumors with intensity-modulated radiation therapy using the volume at risk approach: Employing dose-volume histogram and normal tissue complication probability to evaluate small bowel toxicity. Med Dosim 2002;27:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milano M, Chmura S, Garofalo M, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy in treatment of pancreatic and bile duct malignancies: Toxicity and clinical outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;59:445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Josef E, Shields AF, Vaishampayan U, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy and concurrent capecitabine for pancreatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;59:454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mundt AJ, Lujan AE, Rotmensch J, et al. Intensity-modulated whole pelvic radiotherapy in women with gynecologic malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002;52:1330–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs. observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007;297:267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regine WF (RTOG 0848 co-investigator). Personal communication. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng M, Balter J, Normolle D, et al. Characterization of pancreatic tumor motion using cine MRI: Surrogates for tumor position should be used with caution. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;74:884–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]