Abstract

Background:

Women’s preferences for postabortion contraceptive care vary, and some may experience difficulties realizing their preferences owing to health systems-level barriers. We assessed Mississippi women’s interest in postabortion contraceptive counseling and method use and the extent to which their method preferences were met.

Methods:

In 2016, women ages 18 to 45 completed a self-administered survey at their abortion consultation visit in Mississippi and a follow-up phone survey 4–8 weeks later. Thirty-eight participants were selected for in-depth interviews. We computed the percentage of women who were interested in contraceptive counseling, initiating a method, and who obtained a method at the clinic. We also calculated the percentage who were using their preferred method after abortion and the main reasons they were not using this method. We analyzed transcripts using a theme-based approach.

Results:

Of 323 women enrolled, 222 (69%) completed the follow-up survey. Of those completing follow-up, more than one-half (58%) reported that their consultation or abortion visit was the best time for contraceptive counseling, and 69% wanted to initiate contraception at the clinic. Only 10% obtained a method on site, and in-depth interview respondents reported they could not afford or did not like the options available. At the follow-up survey, 23% of respondents were using their preferred method. Women cited cost or lack of insurance coverage and difficulties scheduling appointments with community clinicians as reasons for not using their preferred method.

Conclusions:

Mississippi women have a large unmet demand for postabortion contraception. Policies that support onsite provision of contraception at abortion facilities would help women to realize their contraceptive preferences.

Abortion care visits often are viewed as an opportune time to provide women with contraception so they can prevent future unintended pregnancies. Yet, women’s interest in contraception after abortion varies. Several large studies have found that the majority of women presenting for abortion care are interested in initiating a method after their procedure (Cansino et al., 2018; Goyal, Canfield, Aiken, Dermish, & Potter, 2017; Kavanaugh, Carlin, & Jones, 2011a). However, not all women want to start a method or discuss contraception at their visits, and some may experience contraceptive counseling and providers’ questions about method initiation as judgmental and coercive (Brandi, Woodhams, White, & Mehta, 2018; Cansino et al., 2018; Matulich, Cansino, Culwell, & Creinin, 2014; Purcell, Cameron, Lawton, Glasier, & Harden, 2016).

For women who do desire postabortion contraception, an array of cost and coverage barriers may prevent them from obtaining their preferred method. For example, the facility where a woman obtains care—particularly one specializing in abortion—may not accept commercial plans or Medicaid owing to insurers’ lack of abortion coverage, which in turn precludes women from using insurance for contraception (Kavanaugh, Jones, & Finer, 2011b; Thompson, Speidel, Saporta, Waxman, & Harper, 2011). Without insurance coverage, many women are unlikely able to afford the out-of-pocket costs for a method, in addition to their abortion (Biggs, Taylor, & Upadhyay, 2017). However, little is known about the extent to which women forego starting a method at the time of their abortion because of these financial and other structural barriers (Thompson et al., 2011).

The fact that not all programs or insurance plans cover the full range of methods at low or no cost also affects women’s use of highly effective contraception in the months after abortion (Goyal et al., 2017; Rocca, Thompson, Goodman, Westhoff, & Harper, 2016; Thompson et al., 2016). Yet, there has been limited study of women’s experiences navigating access to community family planning services after their abortion to address their contraceptive needs (Nielsen et al., 2019). Information about women’s experiences could inform discussions about approaches to facilitate the integration of contraception and abortion care that would help women to realize their contraceptive preferences.

Mississippi provides a useful case in which to examine access to postabortion contraception. In May 2016, the state’s legislature passed a law prohibiting organizations affiliated with abortion services from billing Medicaid for contraception; Mississippi is also one of many U.S. states that prohibits abortion coverage in most circumstances in both Medicaid and Affordable Care Act Marketplace plans (Dreher, 2016; Guttmacher Institute, 2018; Salganicoff & Sobel, 2018). Affordable contraceptive options in women’s communities after abortion also may be limited. Mississippi does not mandate contraceptive coverage without cost sharing in grandfathered private insurance plans (Dreher, 2017; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018). In recent years, the Mississippi Department of Health, which offers subsidized family planning services at community clinics, has experienced significant budget cuts that have led to stringent cost control measures (Pender, 2017). The purpose of this study was to assess Mississippi women’s interest in contraceptive counseling and method initiation at the time of their abortion and assess how well their postabortion contraceptive preferences were being met in the state’s policy and service environment. We hypothesized that the majority of women would be interested in counseling and starting a method at the clinic, but that use of their preferred method after abortion would be low.

Methods

We conducted a convergent parallel mixed methods study with women seeking abortion care at Mississippi’s only licensed abortion facility. The study consisted of a prospective cohort study, involving an in-person baseline survey and follow-up phone survey to assess women’s preferences for and access to postabortion contraception. We also used in-depth interviews to explore women’s preferences and experiences in greater detail.

Mississippi-resident women aged 18–45 years with no known fetal anomalies and who spoke English were eligible to participate. Between June and November 2016, clinic staff informed potentially eligible women attending the initial consultation visit (required ≥24 hours before their abortion) about the study, and then a female research assistant approached women after their ultrasound examination to screen them for eligibility. The research assistant asked eligible women who wanted to participate if they also would be willing to take part in an in-depth interview, which would be completed by phone after the follow-up survey; women were informed that they may not be selected for the interview even if they indicated their willingness to participate. The research assistant did not record the number of women approached who declined to be screened.

At the time of the study, women could purchase oral contraceptive pills and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections at the facility. Income-eligible women could obtain a free levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) from the manufacturer’s patient assistance program and have the device placed for an insertion fee. Women also could obtain a prescription from one of the clinic’s providers. Clinic staff informed women at all abortion-related visits about the methods available on site, and providers offered additional contraceptive counseling.

Baseline Survey

After providing informed written consent and before attending the one-on-one visits with the provider, women completed a 10-minute self-administered tablet-based survey. The baseline survey collected information about women’s demographic characteristics, obstetric history, and sources of reproductive health services. Additionally, women reported whether they had experienced difficulties accessing reproductive health services such as birth control and cervical cancer screening related to each of the following: finding a place that offers these services, finding a place that accepts her health insurance, paying for services, feeling comfortable with clinic nurses and doctors, getting an appointment when she wanted, taking time off work, getting transportation, lack of child care, and lack of partner/family support (Texas Policy Evaluation Project, 2015). We also asked women about their preferred method of contraception after their abortion, using questions from prior research about women’s contraceptive preferences and unmet demand for highly effective methods (Goyal et al., 2017; Potter et al., 2017; Potter et al., 2014).

Follow-up Survey

Four to 6 weeks after women’s baseline survey, research assistants began contacting women for the follow-up phone survey. Interviewers attempted to contact women at least three times by phone. For those who could not be reached after multiple attempts, the interviewers sent emails orprivate Facebook messages and called alternate contacts for those women who provided this information. When interviewers reached a woman for the follow-up survey, they asked if she had had an abortion or was still pregnant; women who were still pregnant did not complete the follow-up survey because the study focused on postabortion contraceptive use. The median time to complete the follow-up survey was 7 weeks (interquartile range, 6.0–8.5 weeks).

In the follow-up survey, we asked women about their interest in starting a method at the clinic after their abortion; whether they obtained contraceptive pills, an injection, or device on site; and at which abortion visit (if any) they believed was the best time to receive contraceptive counseling. Women also reported whether they had had sexual intercourse with a male partner since their abortion, their plans to have children in the future, their current contraceptive use, and which method they would prefer to use if they could get any method for free. Following prior studies (Goyal et al., 2017; Potter et al., 2016), women who were not using their preferred method were asked to select one option from the following list of reasons (or an open response) for not using this method: cannot afford it/not covered by insurance, could not get an appointment, provider does not offer the method, provider advised against using the method, worried provider would know she had an abortion, too much of a hassle to get it, does not know where to get it, and partner does not want her to use it. Additionally, we asked women what type of abortion they had and financial barriers paying for abortion care (Gerdts et al., 2016; Karasek, Roberts, & Weitz, 2016) because the latter may affect women’s ability to pay out of pocket for contraception. Interviewers read the questions and response options and entered women’s answers into an electronic database.

We aimed to recruit 250 women for the survey, anticipating 20% attrition and a final sample size of 200 women completing the follow-up survey. With an expected 30% of women using their preferred contraceptive method by the follow-up survey (Goyal et al., 2017), the margin of error for this sample size was 6.3%. We monitored participant retention during data collection and increased enrollment to 325 women to ensure at least 200 completed the follow-up survey. One woman presented for abortion care twice during the study period and was enrolled inadvertently on both occasions. We used her first survey only in these analyses.

In-Depth Interviews

We conducted in-depth interviews with a purposive sample of women to capture a range of experiences accessing care. Of the women who indicated at study enrollment they would be willing to participate in an in-depth interview (74.9%), we selected potential respondents based on their regular source for women’s health care and insurance status (all reported at the baseline interview) to further explore women’s experiences in different systems of care. To achieve thematic saturation, we planned to interview up to 40 women, with approximately one-half obtaining care from private physicians either through commercial insurance or Medicaid, and the other one-half obtaining care at publicly funded clinics (e.g., public health department, federally qualified health center) using Medicaid or who were uninsured. We also considered women’s county of residence in selecting potential participants to ensure geographic diversity, because women from across the state seek care at the facility and return to their communities for other women’s health services. At the end of the follow-up phone survey, interviewers confirmed whether women selected were still interested in taking part in the in-depth interview and scheduled a time for those interested to complete the interview by phone with a trained qualitative interviewer.

During the in-depth interviews, we asked women to describe their contraceptive use and experiences accessing reproductive health services in the 3 months before their pregnancy and since their abortion. We also asked women to elaborate on their responses from the follow-up survey about the reasons they were interested or not interested in contraceptive counseling and obtaining a method at the clinic. If women were not using their preferred method at the time of the interview, we asked them to discuss the reasons they were not using this method in order to explore women’s preferences further and other challenges obtaining care not reported in the survey. The interview guide was based on prior research on women’s experiences seeking contraceptive care and obtaining their preferred method (Hopkins et al., 2015; White, deMartelly, Grossman, & Turan, 2016). The in-depth interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes and were audio recorded with women’s permission. We reviewed transcripts of the recordings for accuracy and removed identifying information.

Participants received a $15 Visa card for completing the baseline survey and were mailed a $25 Visa card for the follow-up phone survey. Women who completed the in-depth interview were mailed a $30 Visa card. The institutional review board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham approved all study procedures.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

We analyzed data from women who completed the follow-up survey to examine the distribution of women’s preferred timing of contraceptive counseling (consultation, abortion visit, postabortion follow-up, not at all) and the percentage who were interested in initiating a method at the clinic. Givenprior research demonstrating few factors associated with women’s interest in contraceptive counseling and starting a method (Cansino et al., 2018; Kavanaugh et al., 2011a; Matulich et al., 2014), we compared differences across a limited set of characteristics using χ2: insurance status, source for women’s health care, future fertility intentions, any prior barriers accessing reproductive health services, and difficulty paying for abortion care. We also computed the percentage of women who obtained contraceptive pills, an injection, or a device at the clinic. Finally, we examined the distribution of women’s contraceptive method use and preferences at the time of the follow-up survey and the main reason women cited for not using their preferred method. To assess potential selection bias owing to attrition, we also compared the demographic characteristics of participants completing the baseline and follow-up surveys using χ2 tests. All analyses were conducted with Stata 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

We analyzed the in-depth interview transcripts using content and thematic analysis. Two of the authors and a qualitative research assistant developed a codebook based on our research questions, prior literature (Brandi et al., 2018; Purcell et al., 2016), and themes that emerged in the data. We independently coded five transcripts and met to compare coding consistency and reach consensus on coding definitions. After conducting a second round of coding with six transcripts, we divided the remaining transcripts and met to discuss any passages about which we were uncertain of the most appropriate code. We used NVivo 11 (QSR International, Burlington, MA) to code and manage the transcript data.

Finally, we compared the survey results and transcript themes to identify similarities between the data sources (i.e., convergence). We used quotations from the in-depth interviews to highlight our main survey findings and further describe women’s experiences.

Results

Of the 331 women who were screened, 324 women were eligible and enrolled in the study. We excluded one participant who completed the baseline survey before her ultrasound examination, which determined she was not pregnant. Overall, 239 women (74.0%) were recontacted for the follow-up survey. Eight of these women stated that they no longer wanted to participate and nine were still pregnant. Complete baseline and follow-up survey data were available for 222 participants (69%). Women who did not complete the follow-up survey were more likely to be White or multiracial and less likely to report prior barriers accessing reproductive health care (Appendix).

We invited a total of 56 follow-up survey respondents to participate in the in-depth interview; one woman declined and 17 could not be recontacted after multiple attempts. Of the 38 women who completed the in-depth interview, 18 reported private practice clinicians as their source for women’s health care and 20 relied on public health department clinics, federally qualified health centers or family planning clinics, or had no regular source of care.

The majority of follow-up survey participants were between the ages of 18 and 29, identified as Black, and wanted to delay having children for 3 or more years or did not want more children (Table 1). Most women had health insurance, including 29.9% who relied on Medicaid or Mississippi’s Medicaid family planning waiver program. Fifty percent of women reported private practice clinicians as their regular source for reproductive health care and 24.3% relied on public health department clinics for services. Nearly three-quarters of women reported previous barriers accessing reproductive health services and 70.0% reported that it was somewhat or very difficult to pay for their abortion.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Women Recontacted for the Follow-up Survey and In-depth Interviews

| Follow-up Survey (n = 222) |

In-depth Interview (n = 38) |

|

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age, years 18–24 |

84 (37.8) | 12 (31.6) |

| 25–29 | 69 (31.1) | 15 (39.5) |

| 30–34 | 42 (18.9) | 6 (15.8) |

| 35–45 | 27 (12.2) | 5 (13.2) |

| Race* Black |

192 (86.9) | 32 (84.2) |

| White | 25 (11.3) | 5 (13.2) |

| Other/multiracial | 4 (1.8) | 1 (2.6) |

| Educational attainment* High school or less |

61 (27.6) | 14 (36.8) |

| Some college | 118 (53.4) | 18 (47.4) |

| College degree | 42 (19.0) | 6 (15.8) |

| Number of children 0 |

57 (25.7) | 5 (13.2) |

| 1 | 70 (31.5) | 14 (36.8) |

| ≥2 Future fertility intentions* |

95 (42.8) | 19 (50.0) |

| Wants a child in ≤2 years, unsure | 51 (23.1) | 7 (18.4) |

| Wants a child in ≥3 years, does not want more | 170 (76.9) | 31 (81.6) |

| Prior abortion Yes |

93 (41.9) | 18 (47.4) |

| No | 129 (58.1) | 20 (52.6) |

| Insurance*

Commercial |

91 (41.2) | 6 (15.8) |

| Medicaid or Medicaid family planning waiver | 66 (29.9) | 19 (50.0) |

| None | 64 (29.0) | 13 (34.2) |

| Source for women’s health care Private doctor |

111 (50.0) | 17 (44.7) |

| Public health department | 54 (24.3) | 12 (31.6) |

| Federally qualified health center | 23 (10.4) | 2 (5.3) |

| Family planning clinic/other | 15 (6.8) | 3 (7.9) |

| No regular source | 19 (8.6) | 4 (10.5) |

| Prior barriers accessing reproductive health care Yes |

163 (73.4) | 28 (73.7) |

| No | 59 (26.6) | 10 (26.3) |

| Type of abortion Medication |

128 (57.7) | 22 (57.9) |

| Surgical <12 weeks | 56 (25.2) | 12 (31.6) |

| Surgical ≥12 weeks | 26 (11.7) | 4 (10.5) |

| Miscarriage | 12 (5.4) | 0 |

| Difficulty paying for abortion care† Somewhat/very easy |

63 (30.0) | 9 (23.7) |

| Somewhat/very difficult | 147 (70.0) | 29 (76.3) |

| Geographic residence Same county as clinic |

82 (36.9) | 11 (29.0) |

| Other county | 140 (63.1) | 27 (71.0) |

Information missing for one survey participant.

Not asked of women who reported having a miscarriage.

Interest in Contraceptive Counseling and Method Initiation at Abortion Visits

In the follow-up survey, 94% of women were interested in contraceptive counseling. More women preferred counseling at the consultation visit (43.0%) than at their abortion visit (15.4%) (Table 2). Many viewed counseling as an opportunity to learn about methods that would better enable them to avoid pregnancy. For example, a 24-year-old Black woman commented, “I don’t want to use pills since I ended up getting pregnant on the pill. So, I was asking for more information about the Mirena.” Some women’s comments also reflected a sense of shame around unintended pregnancy and stigma around abortion. These women noted that they were interested in information on contraception and starting a method “just to make sure I wouldn’t be back [in] that predicament again” and because “you’re not wanting to even think about having to come back to a clinic to do any kind of procedure.”

Table 2.

Women’s Preferences for the Timing of Contraceptive Counseling and Interest in Starting a Birth Control Method, by Select Characteristics

| Preferred Timing of Contraceptive Counseling* |

Interest in Method Initiation at Abortion Visit† |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consultation Visit |

Abortion Visit |

Postabortion Encounter |

p Value§ | Yes |

No |

p Value§ | |

| %‡ | %‡ | %‡ | %‡ | %‡ | |||

| All women | 42.8 | 15.8 | 35.6 | - | 69.5 | 30.5 | - |

| Insurance║

Commercial |

41.8 | 19.8 | 33.0 | .78 | 67.1 | 32.9 | .68 |

| Medicaid | 42.4 | 10.6 | 39.4 | 68.7 | 31.3 | ||

| None | 45.3 | 14.1 | 35.9 | 73.8 | 26.2 | ||

| Source for women’s health care Private doctor |

41.4 | 18.0 | 36.0 | .79 | 69.2 | 30.8 | .74 |

| Public health department | 44.4 | 14.8 | 33.3 | 64.7 | 35.3 | ||

| Federally qualified health center | 47.8 | 13.0 | 30.4 | 80.9 | 19.0 | ||

| Family planning clinic/other | 33.3 | 0 | 60.0 | 73.3 | 26.7 | ||

| No regular source | 47.4 | 21.0 | 26.3 | 68.4 | 31.6 | ||

| Future fertility intentions║ Wants a child in ≤2 years, unsure |

31.4 | 23.5 | 43.1 | .05 | 59.2 | 40.8 | .08 |

| Wants a child in ≥3 years, does not want more children | 46.5 | 12.9 | 33.5 | 72.5 | 27.5 | ||

| Prior barriers obtaining reproductive health care Yes |

44.8 | 19.0 | 32.5 | .01 | 75.8 | 24.2 | <.01 |

| No | 37.3 | 6.8 | 44.1 | 52.6 | 47.4 | ||

| Difficulty paying for abortion Somewhat/very easy |

33.3 | 15.9 | 41.3 | .28 | 58.7 | 41.3 | .03 |

| Somewhat/very difficult | 45.6 | 15.6 | 34.0 | 74.1 | 25.9 | ||

Results are not reported for the 13 women (5.9%) who were not interested in contraceptive counseling at any visit.

This question was not asked of women who reported having a miscarriage (n = 12).

Row percentages.

Pearson χ2 and Fischer’s exact p values for categorical variables with cell size of five or fewer.

Information missing for one participant.

However, not all women viewed their clinic visits as a good time to address contraception. In the follow-up survey, 35.8% preferred postponing contraceptive counseling until a visit or call after their procedure. Few in-depth interview participants mentioned feeling that discussions around contraception felt judgmental or coercive. More commonly, women noted that they considered contraceptive counseling important, but they were processing a lot of other information and emotions at their visits. A 29-year-old White woman described why she wanted to wait until after her abortion to get contraceptive counseling, saying, “I got the pill abortion, and it’s just, they’re giving you all these instructions, and they’re telling you all about this pill.” When clinic staff raised the topic of contraception afterwards she said, “I think it was just too much going on for me to [have] another conversation about it.” A 23-year-old Black woman who had a second trimester surgical abortion similarly explained, “It’s not like I wasn’t interested [in talking about birth control], I just was really focused on how does the abortion process work, and I was just thinking about that. I wasn’t thinking about getting on birth control.” Other women mentioned that they knew enough about contraception and the method they wanted or that they preferred discussing contraception with their regular provider. For example, a 36-year-old Black woman stated, “It’s better to talk with the physician that has known me for a while and knows what’s going on with me.”

The majority of participants (69.5%) were interested in starting a method at the clinic, regardless of their insurance status and source of women’s health care. Women who reported previous barriers accessing reproductive health services and difficulties paying for abortion care were more likely to be interested in obtaining a method at the clinic than those not experiencing these difficulties. Women thought it would be convenient to get a method at the clinic and avoid the hassle of scheduling other appointments. One of these women, a 32-year-old Black woman who typically relied on a public health department clinic for reproductive health care, stated, “I don’t want to be at the point where I’m trying to schedule with someone else, just to get birth control, so by me doing the procedure, and actually doing it [getting a method] that same day, [that] would help a lot.” Although source of care was not associated with interest in starting a method at the clinic, some women stated that if they went to their regular source of care they would be able to obtain a method using their insurance. A few women also were concerned about the safety of starting a method right after their abortion or wanted to avoid any side effects from hormonal contraception. A 20-year-old Black woman illustrated this point when she explained, “I really wasn’t ready for the side effects of it. Like irregular bleeding and nausea, because I had already been nauseated for a month.”

Among the 146 women who wanted to start a method at the clinic, only 14 (9.6%) did so; 12 obtained oral contraceptives and two started injectable contraception. Women who participated in the in-depth interviews reported that they were unable to afford the additional cost of contraception at the clinic after paying for their abortion. For example, a 30-year-old Black woman was interested in injectable contraception at her abortion visit but did not get the method, stating that the cost was “pretty steep.because I had just spent 600 and some dollars to get my procedure done.” Insured women and some eligible for subsidized services at health department clinics also wanted to avoid unnecessary out-of-pocket costs because they knew they could get a method at no cost through their regular source of care. A 33-year-old Black woman said she would have started injectable contraception at the clinic “if it was affordable,” but instead waited to get the method at the health department, saying it “was free because of the family planning thing [Medicaid] they have me on.” Others noted the limited range of options available and said they did not obtain a method at their abortion visit because the clinic did not offer their preferred method. A 25-year-old Black woman who was interested in the contraceptive implant described her circumstances, saying, “I did [want birth control], but, the only method that they had to offer was the pill. I live a pretty busy lifestyle, and, I didn’t want to have to be responsible for constantly remembering to take that because I knew that I would forget.”

Postabortion Contraceptive Use, Preferences, and Access to Community Services

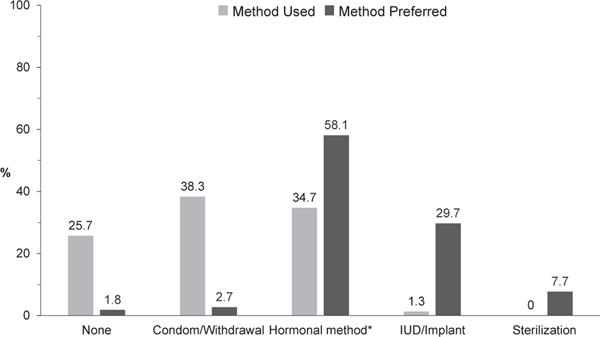

At the follow-up survey, 25.7% of women were not using contraception, 38.3% relied on condoms or withdrawal, and 34.7% used oral contraceptives, injectables, or other short-acting hormonal methods (Figure 1). Three women(1.3%) were using an IUD or implant. However, few reported condoms/withdrawal as their preferred method, whereas more than one-half said they wanted to use short-acting hormonal methods and more than one-third (37.4%) wanted an IUD, implant, or permanent method (i.e., female sterilization, vasectomy). Overall, 23% of women were using their preferred contraceptive method (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Women’s contraceptive method use and preferences 4–8 weeks after their abortion. *Hormonal methods include oral contraceptive pills, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections, the hormonal patch, and the vaginal ring.

The most common reason women gave for not using their preferred method, reported by 41.5% of survey respondents, was that they could not afford it or the method was not covered by their insurance (Table 3). A 29-year-old uninsured White woman wanted to use the levonorgestrel IUD, but had been using oral contraceptives since her abortion because they were less expensive. Staff at the health department told her that the IUD was “a little over $150, plus a doctor’s visit of $40 or something like that,” but she was hopeful that income from a new job might enable her to afford the method soon. Some women with Medicaid and commercial insurance also reported lack of coverage for the method they wanted. For example, a 33-year-old Black woman, who also wanted to use the levonorgestrel IUD after her abortion, was relying on condoms because she had heard that “Medicaid doesn’t pay for it [IUD] anymore” and “it costs $800,” which she was unable to afford. A 25-year-old Black woman with commercial insurance explained, “I don’t think they cover the implant, but they do cover the shot, so I actually recently got on it.”

Table 3.

Primary Reason Women Were Not Using Their Preferred Contraceptive Method by 4–8 Weeks after Abortion (n = 164)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Cannot afford it/not covered by insurance | 68 (41.5) |

| Had difficulties scheduling an appointment or is waiting for an appointment | 34 (20.7) |

| Not sexually active | 16 (9.8) |

| Needs more information about safety and side effects | 10 (6.1) |

| Getting to the clinic is a hassle | 8 (4.9) |

| Does not know where to get it | 4 (2.4) |

| Doctor advised her not to use it | 4 (2.4) |

| Doctor’s office or clinic does not offer it | 3 (1.8) |

| Other reason | 17 (10.4) |

Approximately 20% of women said that they were not using their preferred method because they had been unable to get an appointment at their regular source of care or were waiting for an appointment. Women who regularly relied on health department clinics for services frequently mentioned the long delays to get an appointment. A 26-year-old multiracial woman recounted her experience trying to schedule a visit at the health department for injectable contraception: “I had my abortion in October, [but] I wasn’t able to get [an appointment] until January. I set that appointment up when I first found out I was pregnant. That had to [have] been September, August … It’s always like that … the waiting list is ridiculous.” Although nearly one-half of women (45%) reported no sexual activity since their abortion, only 10% reported absence of sexual activity as their main reason for not using their preferred method. In the in-depth interviews, this often intersected with other barriers accessing contraception, including cost and scheduling conflicts. A 23-year-old Black woman who wanted to use the vaginal ring explained, “Well, when I first got the abortion I knew it was going to be a while before I had sex again, so I just figured I had a little time. Then when I did finally go back to work, it’s like I just didn’t have time . I’m at work all day. I’m only off on the weekends, and they’re [health department] not open on the weekends.”

Discussion

In this study, the majority of Mississippi women were interested in obtaining a contraceptive method at their abortion visit. This finding is consistent with other studies of women seeking abortion (Cansino et al., 2018; Kavanaugh et al., 2011a), which similarly reported that method initiation was acceptable to women from diverse backgrounds. In our sample, we also found that women who had experienced financial and logistical barriers accessing reproductive health services expressed greater interest than those who did not report such difficulties. Women’s comments in the in-depth interviews suggest that they welcome the opportunity to address their contraceptive needs at abortion visits owing in part to logistical barriers, as well as the challenges and stigma of accessing abortion care in a highly restrictive state like Mississippi.

Yet, despite high levels of interest, few actually obtained a method at the clinic, resulting in a large unmet need for postabortion contraception in this setting. Women noted that their preferred method was not available, which points to the difficulties abortion providing facilities face stocking and offering a wide range of contraceptives (Kavanaugh et al., 2011b; Thompson et al., 2011). Also, women’s inability to use insurance, including Medicaid, for contraception at the clinic meant they were unable to afford the additional out-of-pocket costs for methods available onsite after paying for their abortion. These challenges reflect how policies that place abortion facilities outside the network of authorized providers in Mississippi and other states contribute to a highly fragmented service environment for women’s comprehensive reproductive health care, which leads to delays in women obtaining contraception.

Women’s preferences related to contraceptive counseling, however, varied more widely than their interest in starting a method. As reported in other studies, we found that most women did not select their abortion visit as the preferred time to receive contraceptive counseling (Cansino et al., 2018; Matulich et al., 2014), although unlike others’ reports (Brandi et al., 2018), few participants in our study indicated that discussing contraception at that time felt coercive or judgmental. Preference for contraceptive counseling at the mandatory consultation visit was somewhat higher than at the abortion visit, but less than one-half of women considered this the best time to discuss method options. Many reasons reported by women in our study were similar to those noted elsewhere (Cansino et al., 2018; Matulich et al., 2014; Purcell et al., 2016), including women knowing what method they wanted, preferring to get information and services from their regular provider, and feeling overwhelmed by information. The latter finding may be particularly salient in Mississippi and other states where abortion providers are required to provide women with medically unnecessary and inaccurate information about the risks of abortion (Guttmacher Institute, 2019).

By asking women about their preferred contraceptive method and exploring their experiences accessing reproductive health services in the community, our study expands on other research showing that women continue to have an unmet need for contraception in the months after their abortion (Goyal et al., 2017; Nielsen et al., 2019; Rocca et al., 2016). As in these other studies, we found that the majority of women preferred to use a highly effective method, but a smaller percentage of our participants were doing so by the time of the follow-up survey. This difference may be related, in part, to financial and administrative barriers in Mississippi. State budget cuts (Pender, 2017) may have adversely affected low-income women’s ability to obtain timely appointments and access more costly methods like IUDs and implants. Commercially insured women’s accounts also suggest that some women still may be enrolled in older plans that do not meet the Affordable Care Act mandate to cover the full range of U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved methods. Women described many of these same challenges before their abortion, which indicates that Mississippi’s current family planning service and policy environment undermines many women’s efforts to access the services they need to prevent unintended pregnancy.

The findings from this study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. We were unable to contact 26% of women for the follow-up survey, and their experiences may be different than those of women we were able to reach. Although our follow-up rate was lower than expected, it is similar to or better than that of other recent prospective studies of abortion clients (Biggs et al., 2017; Goyal et al., 2017; Nielsen et al., 2019; Roberts, Turok, Belusa, Combellick, & Upadhyay, 2016). Additionally, we asked women about their interest in contraceptive counseling and starting a method in the follow-up survey, when they may have already experienced difficulties accessing care since their abortion; thus, their preferences may not reflect those at the time they obtained care. However, our results are similar to those reported elsewhere (Cansino et al., 2018; Kavanaugh et al., 2011a), and women’s comments from the in-depth interviews provide additional supporting information about their preferences at the time of their abortion. Finally, we have a limited view of women’s ability to access their preferred method given the relatively short interval between their baseline and follow-up surveys. Further research is needed to evaluate the extent to which women are able to obtain their preferred method in the community in subsequent months as more resume sexual activity and attempt to access services.

Implications for Policy and/or Practice

Patient-centered approaches to contraceptive counseling and method provision could address women’s diverse needs and preferences for care in abortion facility settings. In addition to asking women about whether they would like to discuss contraception at their visits, women could use a self-guided decision support tool to explore their birth control options and identify methods that meet their preferences for frequency and mode of use (Dehlendorf et al., 2017); this also could address misperceptions about the safety of postabortion contraception and allow women to tailor information to their specific needs. Women then could discuss their options with a provider at that visit or with their regular provider at a later time. This approach may facilitate shared decision making around contraception and has the potential to minimize the perception of contraceptive coercion.

Additionally, a wide array of changes are needed to reduce barriers to the integration of abortion and contraception and facilitate on-site access for the majority of women who are interested in initiating a method. A key strategy would be to eliminate insurance-related barriers to abortion and contraceptive coverage in commercial insurance plans and Medicaid (Kavanaugh et al., 2011b; Thompson et al., 2011). Abortion coverage remains highly restricted in Mississippi (Guttmacher Institute, 2018; Salganicoff & Sobel, 2018), although the state law prohibiting organizations affiliated with abortion services for billing Medicaid for contraception has since been overturned. However, it remains unclear if women will be able to use Medicaid (or other insurance) for contraception at the facility where we conducted this study. In addition to including abortion facilities in the provider network, insurance plans should ensure coverage and adequate reimbursement for all U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved contraceptive methods. Moreover, programs that enable facilities to stock methods in advance and support uninsured women’s access to the full range of options are needed so that all those seeking care can obtain their preferred birth control method. When these barriers are removed, the majority of women obtain an effective method on the day of their abortion (Biggs et al., 2017). Such changes, along with efforts to restore funding for publicly funded family planning services and make community-based services more robust, will help women to access care at the time that they desire.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. White had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This project was supported by a grant from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. The funders played no role in the design and conduct of the study; interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of this article for publication.

Biographies

Kari White, PhD, MPH, is an Associate Professor, Steve Hicks School of Social Work and Department of Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin. She studies the effect of policies on family planning service delivery and women’s access to reproductive health care.

Kaitlin J. Portz, PhD, is a Psychologist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital Center for Advanced Medicine. She is interested in sexual health promotion and transgender health.

Samantha Whitfield, MPH, is a Program Manager at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, School of Public Health. She is interested in minority population health, sexual health promotion, and infectious disease, including HIV and STI prevention.

Sacheen Nathan, MD, MPH, is the Medical Director at Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2020.01.004.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Biggs MA, Taylor D, & Upadhyay UD (2017). Role of insurance coverage in contraceptive use after abortion. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 130(6), 1338–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandi K, Woodhams E, White KO, & Mehta PK (2018). An exploration of perceived contraceptive coercion at the time of abortion. Contraception, 97(4), 329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cansino C, Lichtenberg ES, Perriera LK, Hou MY, Melo J, & Creinin M. (2018). Do women want to talk about birth control at the time of a firsttrimester abortion? Contraception, 98(6), 535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehlendorf C, Fitzpatrick J, Steinauer J, Swiader L, Grumbach K, Hall C, & Kuppermann M. (2017). Development and field testing of a decision support tool to facilitate shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Patient Education and Counseling, 100, 1374–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher A. (2016). Governor signs bill prohibiting Medicaid reimbursements for Planned Parenthood. Jackson Free Press. Available: www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2016/may/12/governor-signs-planned-parenthood-medicaid-reimbur/. Accessed: August 31, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dreher A. (2017).Keeping insurance rates stable despite congressional interference. Jackson Free Press. Available: www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2017/aug/02/keeping-insurance-rates-stable-despite-congression/. Accessed: August 31, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdts C, Fuentes L, Grossman D, White K, Keefe-Oates B, Baum SE, . Potter JE (2016). The impact of clinic closures on women obtaining services after implementation of a restrictive law in Texas. American Journal of Public Health, 106(5), 857–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal V, Canfield C, Aiken ARA, Dermish A, & Potter JE (2017). Postabortion contraceptive use and continuation when long-acting reversible contraception is free. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 129(4), 655–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute. (2018). State funding for abortion under Medicaid. Available: www.guttmacher.org/print/state-policy/explore/state-funding-abortion-undermedicaid. Accessed: August 31, 2018.

- Guttmacher Institute. (2019). Counseling and waiting periods for abortion. Available: www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/counseling-and-waiting-periods-abortion. Accessed: March 20, 2019.

- Hopkins K, White K, Linkin F, Hubert C, Grossman D, & Potter JE (2015). Women’s experiences seeking publicly funded family planning services in Texas. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 47(2), 63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2018). State requirements for insurance coverage of contraceptives. Available: www.kff.org. Accessed: August 31, 2018.

- Karasek D, Roberts SCM, & Weitz T. (2016). Abortion patients’ experience and perceptions of waiting periods: Survey evidence before Arizona’s two-visit 24-hour mandatory waiting period law. Women’s Health Issues, 26(1), 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh ML, Carlin EE, & Jones RK (2011a). Patients’ attitudes and experiences related to receiving contraception during abortion care. Contraception, 84(6), 585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh ML, Jones RK, & Finer LB (2011b). Perceived and insurance-related barriers to the provision of contraceptive services in U.S. abortion care settings. Women’s Health Issues, 21(3 Suppl), S26–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matulich M, Cansino C, Culwell KR, & Creinin MD (2014). Understanding women’s desires for contraceptive counseling at the time of firsttrimester surgical abortion. Contraception, 89(1), 36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen TC, Michel KG, White R, Wall KM, Christiansen-Lindquist L, Lathrop E, . Haddad LB (2019). Predictors of more effective contraceptive method use at 12 weeks post-abortion: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Women’s Health, 28(5), 591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pender G. (2017). Health department ponders what programs to scuttle, layoffs. The Clarion-Ledger. Available: www.clarionledger.com/story/news/politics/2017/05/21/health-department-cuts/328476001/. Accessed: June 16, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Potter JE, Coleman-Minahan K, White K, Powers DE, Dillaway C, Stevenson AJ, . Grossman D. (2017). Contraception following delivery among publicly insured women in Texas: Use compared with preferences. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 130(2), 393–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JE, Hopkins K, Aiken AR, Hubert C, Stevenson A, White K, & Grossman D. (2014). Unmet demand for highly effective postpartum contraception in Texas. Contraception, 90(5), 488–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JE, Hubert C, Stevenson AJ, Hopkins K, Aiken AR, White K, & Grossman D. (2016). Barriers to postpartum contraception in Texas and pregnancy within two years of delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 127(2), 289–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell C, Cameron ST, Lawton J, Glasier A, & Harden J. (2016). Contraceptive care at the time of medical abortion: Experiences of women and health professionals in a hospital or community sexual and reproductive health context. Contraception, 93(2), 170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SCM, Turok DK, Belusa E, Combellick S, & Upadhyay UD (2016). Utah’s 72-hour waiting period for abortion: Experiences among a clinic-based sampleofwomen.PerspectivesonSexualandReproductiveHealth,48(4),179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca CH, Thompson KMJ, Goodman S, Westhoff C, & Harper CC (2016). Funding policies and postabortion long-acting reversible contraception: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 214. 716.e711–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salganicoff A, & Sobel L. (2018). Abortion coverage in the ACA Marketplace Plans: The impact of proposed rules for consumers, insurers and regulators. San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Texas Policy Evaluation Project. (2015). Barriers to family planning access in Texas: Evidence from a statewide representative survey. Available: https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/txpep/_files/pdf/TxPEP-ResearchBrief_Barriers-to-Family-Planning-Access-in-Texas_May2015.pdf. Accessed: September 29, 2018.

- Thompson KMJ, Rocca CH, Kohn J, Goodman S, Stern L, Blum M, . Harper CC (2016). Public funding for contraception, provider training, and use of highly effective contraceptives: A cluster randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health, 160(3), 541–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson KMJ, Speidel JJ, Saporta V, Waxman NJ, & Harper CC (2011). Contraceptive policies affect post-abortion provision of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception, 83, 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K, deMartelly V, Grossman D, & Turan JM (2016). Experiences accessing abortion care in Alabama among women traveling for services. Women’s Health Issues, 26(3), 298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.