Abstract

Mycoplasmas are potent macrophage stimulators. We describe the isolation of macrophage-stimulatory lipopeptides S-[2,3-bisacyl(C16:0/C18:0)oxypropyl]cysteinyl-GQTDNNSSQSQQPGSGTTNT and S-[2,3-bisacyl(C16:0/C18:0)oxypropyl]cysteinyl-GQTN derived from the Mycoplasma hyorhinis variable lipoproteins VlpA and VlpC, respectively. These lipopeptides were characterized by amino acid sequence and composition analysis and by mass spectrometry. The lipopeptides S-[2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)propyl]cysteinyl-GQTNT and S-[2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)propyl]cysteinyl-SKKKK and the N-palmitoylated derivative of the latter were synthesized, and their macrophage-stimulatory activities were compared in a nitric oxide release assay with peritoneal macrophages from C3H/HeJ mice. The lipopeptides with the free amino terminus showed half-maximal activity at 3 pM regardless of their amino acid sequence; i.e., they were as active as the previously isolated M. fermentans-derived lipopeptide MALP-2. The macrophage-stimulatory activity of the additionally N-palmitoylated lipopeptide or of the murein lipoprotein from Escherichia coli, however, was lower by orders of magnitude. It is concluded that the lack of N-acyl groups in mycoplasmal lipoproteins explains their exceptionally high in vitro macrophage-stimulatory capacity. Certain features that lipopolysaccharide endotoxin and mycoplasmal lipopeptides have in common are discussed. Lipoproteins and lipopeptides are likely to be the main causative agents of inflammatory reactions to mycoplasmas. This may be relevant in the context of mycoplasmas as arthritogenic pathogens and their association with AIDS.

Mycoplasmas are small, cell wall-less, pliable bacteria which are associated with a number of diseases such as atypical pneumonia, nongonococcal urethritis, arthritis, and AIDS. These organisms reside at mucosal surfaces, e.g., of the lungs or the urogenital tract, and they encounter macrophages as the first line of host defense in this environment. The interactions of phagocytes with mycoplasmas in general have been recently reviewed (23). Specifically, macrophages react with mycoplasmas and their products by enhanced release of proinflammatory cytokines (13, 16, 20, 21, 33, 35, 39, 40, 42, 44) and, in the case of murine macrophages concomitantly treated with gamma interferon, the production of nitric oxide (27, 36). In addition, macrophages modulate the expression of their class II major histocompatibility complex molecules under the influence of mycoplasmal products (12, 41). There are also numerous reports on mycoplasma-mediated effects on B and T lymphocytes (reviewed in reference 37), but many of these effects were not immunologically well characterized and may be indirect and due primarily to cytokine release by macrophages and monocytes (see, e.g., reference 29). A notable exception is, of course, the working mechanism of a protein superantigen that appears to be restricted to Mycoplasma arthritidis and which, by definition, reacts with both T cells and macrophages (8).

There is ample evidence for macrophage-activating material in many species of the class Mollicutes (5, 13, 20, 39, 40, 42). Because of lack of sufficient starting material and/or difficulties in purification of the mostly lipophilic substances, rigorous biochemical identification of mycoplasma-derived effector molecules is difficult and was rarely achieved. However, the structure of a macrophage-stimulatory activity (MSA) from M. fermentans, formerly designated mycoplasma-derived high-molecular-weight material (MDHM) (28), was recently elucidated. Depending on the mycoplasma source and the method of preparation, this material can be isolated as a mixture of lipopeptides (27, 30) or a lipopeptide with a defined sequence such as we isolated from M. fermentans clone II 29-1 and named macrophage-activating lipopeptide of molecular mass 2 kDa (MALP-2) (31). The lipophilic, fatty acid-substituted S-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)-cysteine amino terminus is characteristic (30).

Bacterial lipoproteins have long been known to affect immune system cells through their MSA (1, 14, 19, 32) and may therefore be important “bacterial modulins,” comparable to endotoxin and likewise leading to the release of proinflammatory cytokines (reviewed in reference 15). However, there may be several important and surprising differences in the structure and specific biological activity of mycoplasmal lipoproteins with respect to those from other bacterial sources. (i) While “conventional” lipoproteins, with one exception (25), contain one N-terminal and two ester-bound long-chain fatty acid substituents (2), at least the lipopeptides isolated from M. fermentans do not contain this N-acyl group (31). (ii) As a consequence of N-acylation, much higher concentrations of “conventional” lipoproteins (micrograms per milliliter) than of M. fermentans-derived lipoproteins (picograms per milliliter) are required for in vitro macrophage activation. (iii) The prototype of a bacterial lipoprotein, Braun’s murein lipoprotein from Escherichia coli, is constitutively expressed. In contrast, the expression of mycoplasmal lipoproteins, which are dominant immunogens, is subject to phase and size variation (6, 43, 45, 46). This has led to their designation as variable lipoproteins (Vlp).

The evidence for lipoproteins or lipopeptides with exceptionally high macrophage-stimulatory potential has rested so far on the one example from M. fermentans. In this communication we describe the isolation and characterization of macrophage-stimulatory lipopeptides with an equally high specific activity, derived from Vlp from M. hyorhinis, a Mycoplasma species that is arthritogenic in swine (9). In addition, we present data obtained with synthetic analogues of bacterial lipopeptides and authentic murein lipoprotein from E. coli to show the negative influence of N-acylation on the specific activity of such lipopeptides in the in vitro macrophage activation assay. These studies should serve to explain the exceptionally high inflammatory capacities of mycoplasmas, organisms that, being wall-less and thus lacking the conventional macrophage activators, could a priori be expected to entirely lack such activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycoplasma cultures and isolation of clones.

M. hyorhinis BS was recovered from the same contaminated HL60 culture as our M. fermentans clones (31) and was first cultivated at 37°C in modified Hayflick’s medium with 20% horse serum and without thallium (11). Mycoplasmas were filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter and plated on 3% heart infusion agar (Difco) in this medium. As assessed by a colony-blotting assay with M. hyorhinis- and M. fermentans-specific antisera (a generous gift of M. Runge, Tierärztliche Hochschule Hannover, Hanover, Germany), only M. hyorhinis colonies evolved. Single colonies were picked with a Pasteur pipette under a stereo microscope and further propagated in liquid modified Hayflick’s medium. Larger volumes were then grown in GBF-3 medium equilibrated with a 7.5% CO2 atmosphere (31). Cultures were harvested in the middle of the growth phase and washed with pyrogen-free saline. Mycoplasmas were kept frozen at −20°C until use.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, Western immunoblotting, and determination of MSA in gel sections.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed by the method of Laemmli under reducing conditions with 15% polyacrylamide gels. For determination of the MSA, a lane from the fresh, wet gel was cut into 0.3-mm segments, which were extracted for 2 min with 0.3 ml of n-octyl β-d-glucopyranoside (octyl glucoside) in a boiling-water bath. The extracts were assayed in the nitric oxide release assay. For immunoblotting, 5 μg of mycoplasma protein was applied to each lane, one of which was gold stained after being electrotransferred to 0.2-μm-pore-size polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The other lanes were immunostained with Vlp-specific monoclonal antibodies (6) as indicated. The antibodies were used at a 1:1,000 dilution and detected with 1:1,000-diluted peroxidase-labeled rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Dako A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark), using 4-chloro-1-naphthol as the substrate.

Determination of MSA by the nitric oxide release assay.

MSA was determined by the nitric oxide release assay, as described previously (27), with peritoneal exudate cells from C3H/HeJ endotoxin-low-responder mice. These cells contain about 40% macrophages; the remaining cells are primarily B lymphocytes. One unit of MSA per milliliter is defined as the dilution of macrophage stimulator required to obtain half-maximal nitric oxide release. Often, several dilution steps are required before the substances are introduced into the culture. Unless indicated otherwise, the first dilution steps were made in the presence of 25 mM octyl glucoside, which was added as a carrier as well as a solubilizing agent. Then the solution was further diluted with culture medium. Finally, a series of 1:2 dilutions was made in medium to which the peritoneal cells are added. There was no influence of the detergent, which is present below the critical micellar concentration at the high final dilutions.

Detergent extraction and reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) of macrophage-activating lipoproteins.

A frozen mycoplasma suspension containing 50 mg of mycoplasma protein, determined by the method of Lowry et al. (22), was thawed in the presence of serine protease and metalloproteinase inhibitors and delipidated with chloroform-methanol (2:1) as described for M. fermentans (31). The remaining water phase was treated with Benzonase (Merck) and extracted for 5 min in 25 mM octyl glucoside at 95°C. The extract was then pressure dialyzed as was done with M. fermentans (31). This material, containing 5.6 mg of protein, was applied in 1 ml of 0.1 M ammonium acetate (pH 6.9) containing 25 mM octyl glucoside and 50 mM CaCl2 to an SP 250/10 Nucleosil 300-7 C18 column (Macherey & Nagel, Düren, Germany) and eluted in 6-ml fractions at 40°C with a linear water–2-propanol gradient at a pump rate of 3 ml/min (31) (see Fig. 2A).

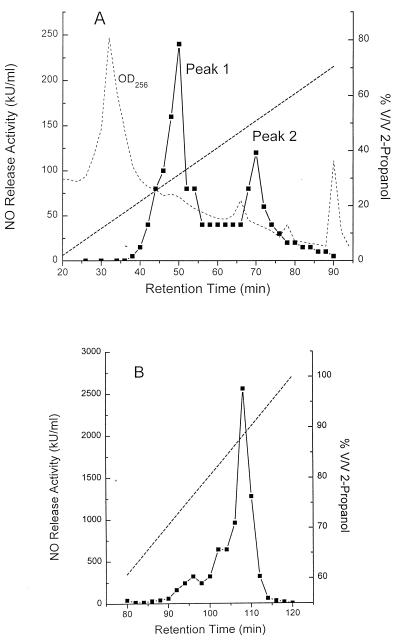

FIG. 2.

HPLC of octyl glucoside-extracted MSA from M. hyorhinis. MSA, as determined by the nitric oxide release assay (solid line), was eluted with a 2-propanol gradient (straight dashed line). The UV trace at 256 nm is shown as a fainter dashed line. (A) A sample from an octyl glucoside extract of M. hyorhinis clone VIII-23 containing 5.5 mg of protein with 2 × 107 U of MSA was applied to a 10- by 250-mm RP18 reversed-phase column. (B) Material eluting in peak 1 was treated with proteinase K and rechromatographed on a 4- by 250-mm RP18 column.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of Vlp in HPLC fractions.

Portions of 20 μl from HPLC fractions or aliquots containing 2 kU of MSA were dried in vacuo in Maxisorp enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). The plates were treated with commercial blocking buffer. Primary monoclonal antibodies (6) were used at a 1:2,000 dilution, and peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse Ig antibodies were used at a 1:1,000 dilution. The plates were developed with 2,2′-azino-di-[3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonate (6)] (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) as the chromogenic substrate.

Isolation of the macrophage-activating lipopeptide MALP-H.

The material eluting after 50 min and showing MSA (see Fig. 2A, peak 1) was freeze-dried in the presence of 0.5 mM octyl glucoside as carrier and taken up in 1 ml of 30 mM Tris HCl buffer (pH 8.8) containing 1 mM calcium lactate. A 20-μg portion of proteinase K (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C, after which time the reaction was stopped by heating for 2 min in a boiling-water bath. The reaction mixture was separated on an ET 250/4 Nucleosil 120-7 C18 HPLC column (Macherey & Nagel) at 40°C. MSA was eluted as one major peak with 87% 2-propanol (see Fig. 2B).

Peptide sequence analysis.

Aliquots of 2.5 to 10 μl were directly taken from HPLC fractions and applied to Biobrene-coated, precycled fiberglass filters of an Applied Biosystems 494A Procise sequencer and sequenced as specified by the manufacturer for standard gas-phase programs (17).

Amino acid composition analysis.

Amino acid analysis was carried out on an Applied Biosystems 420A/H amino acid analyzer with automated gas-phase hydrolysis (6 N HCl at 160°C for 75 min), and on-line analysis of the phenylthiocarbamoyl amino acid derivatives was performed on a 130A HPLC apparatus with a 920A data system.

Fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry.

Positive-mode fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry (FAB-MS) was performed on a JMS-HX/HX110A sector field instrument (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV and with a resolution of 1/3,000. The JEOL FAB gun was operated at 6 kV with xenon as the reactant gas. Thioglycerol served as matrix.

De-O-acylation of lipopeptides and lipoproteins.

Octyl glucoside (1 mM) was added as a carrier to 0.5-ml aliquots of the HPLC fractions containing lipoproteins or lipopeptides. The samples were adjusted with aqueous methylamine to 0.4 M base, left at 25°C overnight, and then taken to dryness over P2O5 in a desiccator. The residues were taken up in a minimum of 50% 2-propanol in water and used for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization MS (MALDI-MS).

MALDI-MS.

MALDI-MS was performed on a Bruker REFLEX instrument equipped with a nitrogen laser (337 nm, 3-ns pulse). Spectra were recorded at an acceleration voltage of 20 kV. The instrument was internally calibrated with bovine insulin. Octyl glucoside (final concentration, 8 mM) was added to aliquots from the HPLC for optimal signals (7). The samples were diluted 1:2 (vol/vol) with 100 mM α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 60% aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and allowed to dry on the stainless steel target.

Synthesis of lipopeptide analogues.

N-Fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl-S-2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)-(2-RS)-propyl-(R)-cysteine [Fmoc-Dhc(Pam2)-OH] was synthesized as previously described (24). The modified hexapeptide S-[2(RS),3-bis(palmitoyloxy)propyl]-(R)-cysteinyl-GQTNT was prepared by the Fmoc method for solid-phase synthesis on an Applied Biosystems model 433A automated synthesizer. A Wang-PHB resin loaded with tert-butyl-protected Fmoc-threonine residue was used as the solid support. Resin substitution was 0.6 mmol/g, and 0.1 mmol of amino acid was used for each coupling. The triphenylmethyl group was used to protect the side chain of asparagine and glutamine, and the tert-butyl group was used to protect threonine. The Fmoc-amino acid attached to the resin was deprotected by using piperidine. The amino acids were coupled with 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate and hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt). Fmoc-Dhc(Pam2)-OH was coupled in double excess to the resin-bound N-pentamer peptide with diisopropylcarbodiimide-HOBt in dimethylformamide-dichloromethane (1:2) for 12 h. The peptide and all protecting groups were cleaved from the resin with trifluoroacetic acid containing phenol (5%, vol/vol), thioanisole (5%, vol/vol), ethanedithiole (5%, vol/vol) and water (7%, vol/vol). The synthesis was monitored by electrospray ionization MS on a triple-quadrupole instrument API III TAGA X (PE Sciex, Thornhill, Ontario, Canada). The macrophage-activating lipopeptide analogue (MALP-A) S-[2(RS),3-bis(palmitoyloxy)propyl]-(R)-cysteinyl-SKKKK, with a free amino terminus and the corresponding N-palmitoylated lipopeptide, was prepared as described elsewhere (25). Stock solutions of lipopeptides were prepared in 25 mM octyl glucoside in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and further diluted with culture medium. The detergent had no effects on the cell cultures at the high dilutions used.

Bacterial lipoprotein from E. coli.

The water-soluble murein lipoprotein from E. coli was a generous gift of J. Gmeiner. The isolation and properties of this material are described in reference 26.

RESULTS

Isolation of macrophage-stimulatory lipoproteins from M. hyorhinis.

Macrophage stimulation by mycoplasma-derived products can be assayed by monitoring the release of cytokines, prostaglandins or—in the case of murine cells—nitric oxide. In earlier work with HPLC-purified but at that time unidentified mycoplasmal lipopeptides, these preparations gave similar dose-response curves, regardless of whether tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-6, or nitric oxide were determined (27). Assaying the decay products of nitric oxide, as described by us previously (27), yields reproducible quantitative data, is inexpensive and easy to perform, and thus is optimally suited to the processing of large numbers of samples over a wide range of concentrations.

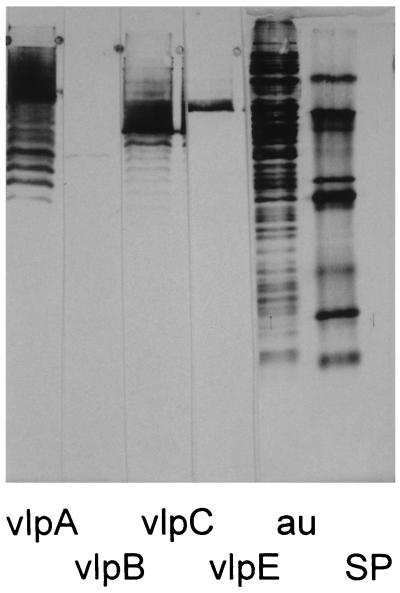

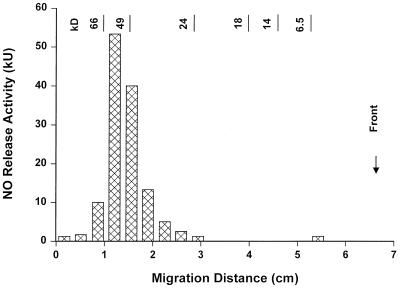

M. hyorhinis was accidentally discovered in some batches of a cell line from which we previously isolated our M. fermentans clones (31). Care was taken to separate this species from M. fermentans by agar cloning after filtration. Eleven M. hyorhinis clones were isolated from single colonies and propagated in liquid medium. The MSA in octyl glucoside extracts from these clones, as determined by the nitric oxide release assay and calculated per milligram of extracted protein, ranged between 300 and 600 kU/mg. This means that an extract from a mycoplasma suspension with a 1-mg/ml protein content could be diluted up to 6 × 105-fold and still yield a half-maximal response in the nitric oxide release assay. The MSA per milligram of mycoplasma protein of these clones was surprisingly high and uniform, while the previously isolated M. fermentans clones varied considerably in their activity, with their average activity being in the range of 50 kU/mg and below (31). M. hyorhinis clone VIII-23 expressed the typical ladder of M. hyorhinis Vlp antigens (Fig. 1), and was randomly chosen as a source for the isolation of macrophage-stimulatory material. To this end, mycoplasmas from this clone were grown and extracted with octyl glucoside by our previously published methods (31). The concentrated octyl glucoside extract was subjected to HPLC. MSA, monitored by the nitric oxide release assay, eluted in two peaks (Fig. 2A, peaks 1 and 2). A small portion of peak 1 was subjected to SDS-PAGE. The gel was sectioned, and the MSA in the extracted sections was determined (Fig. 3). The macrophage-stimulatory substance migrated as a broad peak of heterogeneous high-molecular-mass material of approximately 55 kDa. Silver staining of a parallel lane, to which the same amount of peak 1 material was applied, yielded only a faint yellowish stain at the position of maximal nitric oxide release activity (results not shown). According to the amino acid sequence determination of peak 1, this material consisted of a mixture of lipoproteins. These are characterized by an amino-terminal dihydroxy-(2-RS)-propyl-(R)-cysteine at position 1, which is not detected by routine procedures (30), followed by the sequence GQT(N/D)(N/D/T)(D/N)(K/S/L)SQ. This means that although the lipoproteins are closely related at their amino terminus, the amino acids at positions 5 through 8 differed in this mixture. Some of these sequences are compatible with the published DNA-derived amino-terminal sequences of VlpA (GQTDNNSSQ), VlpB (GQTNTDKSQ), and VlpC (GQTNTDKSQ) from M. hyorhinis (45). Peak 1 material was also tested in an ELISA with a set of monoclonal antibodies against VlpA, VlpB, VlpC, and VlpE (6). Peak 1 material reacted only with anti-VlpA and anti-VlpC antibody (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Western immunoblot of M. hyorhinis clone VIII-23. Four 3.5-μg samples, one 2.5-μg clone VIII-23 protein sample (au), and one sample containing molecular weight markers (SP) were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 15% polyacrylamide gel in the discontinuous system of Laemmli under reducing conditions. Proteins were electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The blot was cut into strips, which were immunostained with monoclonal antibodies specific for VlpA (F205C6A), VlpB (F206C1A), VlpC (F192C17a), and VlpE (F146C11B). The lanes on the right (au and SP) were gold stained.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE of peak 1 from the HPLC (Fig. 2A). A 75-kU portion of MSA was applied to a 15% polyacrylamide gel in the discontinuous system of Laemmli under reducing conditions. The gel was cut into 3-mm segments, which were extracted with 0.3 ml of hot octyl glucoside for subsequent determination of MSA by the nitric oxide release assay.

Structure elucidation of the lipopeptide eluting in peak 2 material.

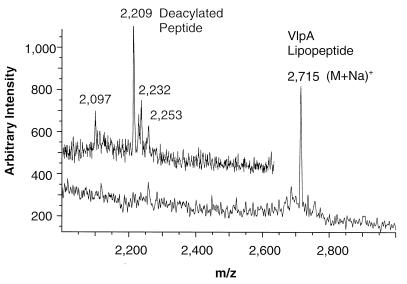

One way of identifying O-acylated lipoproteins is to determine their molecular mass before and after mild-alkali treatment which removes ester-bound fatty acids. The material in the smaller peak exhibiting MSA (peak 2 material, Fig. 2A) was subjected to MALDI-MS. The spectrum (Fig. 4) showed a prominent peak at a mass per charge (m/z) of 2,715, which shifted after mild-alkali treatment to an m/z of 2,209. The difference of 506 is consistent with the cleavage of two ester-bound fatty acids (e.g., C16:0 plus C18:0). The amino-terminal sequence of this material was GQTDNNSSQSQQPGSGTT (the amino terminal lipid-modified cysteine is not detected by routine amino acid sequencing). According to the peptide sequence, the amino acid composition and published DNA sequences (45), this material is a truncated form of VlpA. The m/z value could be explained by the sodium adduct of the lipopeptide S-[2,3-bisacyl(C16:0/C18:0)oxypropyl]cysteinyl-GQTDNNSSQSQQPGSGTTNT.

FIG. 4.

MALDI-MS spectrum of peak 2 from the HPLC (Fig. 2A). A portion of this material was subjected to mild deacylation in aqueous methylamine. The spectra of the native material and the deacylated (insert) material were recorded in the positive mode. The material corresponds to a truncated form of VlpA.

Proteinase K treatment of peak 1 material and structure elucidation of the resulting lipopeptide MALP-H.

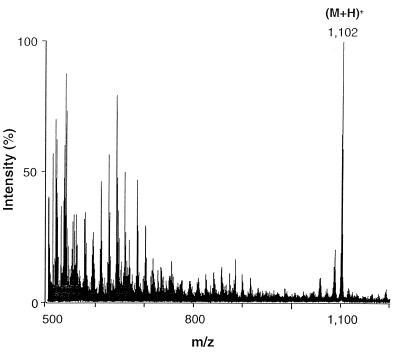

To obtain a homogeneous lipopeptide in sufficient amounts for subsequent studies, the lipoproteins eluting in peak 1 (Fig. 2A) were digested with proteinase K and the resulting macrophage-stimulatory lipopeptides were isolated by rechromatography. The major activity eluted at 87% 2-propanol (Fig. 2B). When subjected to positive-mode FAB-MS, this material showed a main peak at an m/z of 1,102, corresponding to the (M+H)+ ion (Fig. 5). This molecular mass, the amino acid composition, and the sequence are compatible with the structure S-[2,3-bisacyl(C16:0/C18:0)oxypropyl]cysteinyl-GQTN. We named this lipopeptide MALP-H, for macrophage-activating lipopeptide from M. hyorhinis.

FIG. 5.

Positive-mode FAB mass spectrum of HPLC-purified MALP-H. MALP-H was obtained from proteinase K-digested peak 1 material (Fig. 2A). Ions in the lower-mass region (m/z 500 to 800) are due to impurities of the thioglycerol matrix.

Comparison of specific activities of lipopeptides and lipoproteins in the nitric oxide release assay.

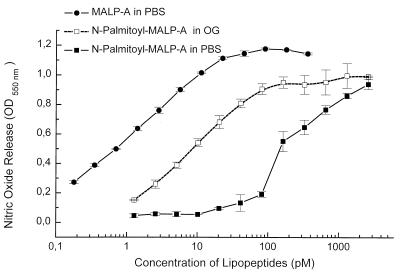

The dependence of nitric oxide release on the concentration of stimulatory compounds and the definition of 1 unit of stimulatory activity (27) (see Materials and Methods) allow one to define a specific activity per mole and thus to compare the relative MSA of various compounds on a molar basis. The peptide content was determined by amino acid analysis, and MSA was determined by serial dilutions. From such data, the molarity of a sample being diluted to yield half-maximal stimulation, defined as 1 U of activity per ml, can be derived and the number of units per mole can be calculated. For example, the lipohexapeptide MALP-A showed half-maximal response at a concentration of 3 pM (Fig. 6). It follows from this that 1 U/ml corresponds to 3 fmol/ml or that 1 U corresponds to 3 × 10−15 mol, and hence the specific activity of this lipopeptide is 3.3 × 1014 U/mol. The specific activity of MALP-H, as determined with the synthetic analogue S-[2(RS),3-bis(palmitoyloxy)propyl]-(R)-cysteinyl-GQTNT in the presence of octyl glucoside, was in the same range, with half-maximal activity around 3 pM (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Influence of N-acylation and solubility on the MSA of synthetic lipopeptide analogues. S-[2(RS),3-Bis(palmitoyloxy)propyl]-(R)-cysteinyl-SKKKK (MALP-A), with a free N terminus, and the corresponding N-palmitoylated derivative were compared in the nitric oxide release assay after initial solubilization in PBS or octyl glucoside (OG), with further dilution being made in culture medium. MALP-A gave the same dose response whether dissolved in octyl glucoside or PBS. The protein content of stock solutions was determined by amino acid analysis. Data are from triplicate determinations and are shown as means and standard deviations.

To estimate the specific activity of the naturally occurring truncated VlpA, samples from peak 2 (Fig. 2) containing 1.3 × 106 U were combined, taken to dryness in the presence of octyl glucoside as carrier, and redissolved in 1 ml of water. The lipopeptide content was determined by amino acid analysis to be 5 nmol. From these data, a specific activity of 2.6 × 1014 U/mol results for S-[2,3-bisacyl(C16:0/C18:0)oxypropyl[cysteinyl-GQTDNNSSQSQQPGSGTTNT. Although this value may be less accurate, since our other data were derived from assaying synthetic compounds, it is surprisingly close and certainly within the same order of magnitude.

The influence of amino-terminal acylation and of optimal solubilization on MSA is illustrated for the synthetic lipohexapeptide MALP-A and for its N-acylated form N-palmitoyl-MALP-A in Fig. 6. MALP-A was half-maximally active at 3 pM, regardless of whether it was dissolved in PBS or optimally solubilized with octyl glucoside. By contrast, the N-acylated MALP-A was 10 times less active than MALP-A, even when optimally solubilized (5 × 1013 U/mol), and 2 orders of magnitude less active when taken up in PBS (3 × 1012 U/mol).

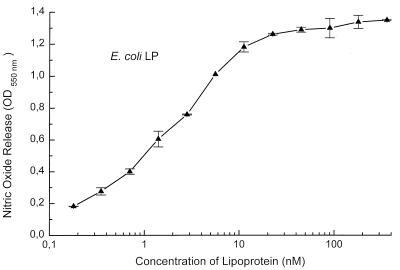

Finally, the specific MSA of authentic murein lipoprotein from E. coli was assayed after it was dissolved either directly in PBS or first in octyl glucoside. The lipoprotein was equally active under both conditions but distinctly less active than were mycoplasmal lipopeptides. From the data (Fig. 7), a specific activity of 3.3 × 1011 U/mol can be calculated.

FIG. 7.

Dose response of E. coli murein lipoprotein in the nitric oxide release assay. A stock solution of the lipoprotein was prepared, diluted 1:2 in 50 mM octyl glucoside or physiological saline, and further diluted in culture medium. The protein content of the stock solution was determined by amino acid analysis. Data are from duplicate determinations and are shown as means and standard deviations for the octyl glucoside-solubilized sample. The sample diluted in saline gave identical results.

DISCUSSION

After our earlier characterization of the highly active macrophage-stimulatory lipopeptide MALP-2 from M. fermentans, in this study we isolated similarly active compounds from M. hyorhinis. A trait common to both Mycoplasma species is their alleged (38) or proven (9) arthritogenicity in their respective hosts, humans and swine. Both species express lipoproteins with a characteristic di-O-acylated amino terminus, and both produce lipopeptides derived from these; hence, the M. fermentans-derived MALP-2 is a truncated form of a 48-kDa lipoprotein (4), and peak 2 material (Fig. 2A) from M. hyorhinis clone VIII-23 turned out to be a truncated VlpA. We do not know anything about the functions, if any, of such lipopeptides for the mycoplasmas. It is unlikely that they are artifacts, since great care was taken to prevent protease degradation during isolation.

The majority of macrophage-activating material that we extracted was heterogeneous and consisted of a mixture of more extended lipoproteins. The lipopeptide MALP-H obtained from this material by protease treatment had the structure S-[2,3-bisacyl(C16:0/C18:0)oxypropyl]cysteinyl-GQTN and is likely to be derived from VlpC. This follows from our peptide-sequencing data in conjunction with published DNA sequences for the gene encoding this Vlp (45) and the reactivity of the starting material of this lipopeptide in the ELISA with monoclonal antibodies.

A synthetic analogue of MALP-H, the truncated VlpA, and the synthetic di-O-acylated lipohexapeptide MALP-A all stimulated macrophages in the same picomolar (picogram-per-milliliter) concentration range as was previously observed for the natural M. fermentans-derived MALP-2 (31). This was the case regardless of the peptide sequence. In contrast, Braun’s murein lipoprotein from E. coli and lipoproteins from Treponema pallidum or Borrelia burgdorferi are commonly used in the microgram-per-milliliter range for macrophage/monocyte stimulations (14, 19, 32). Similar microgram-per-milliliter doses were recently reported for purified spiralin, a lipoprotein from Spiroplasma melliferum (3), an organism whose natural habitat is bees. Since other authors used assay systems different from ours, we measured the MSA of E. coli murein lipoprotein in our nitric oxide release test to compare it with that of mycoplasmal lipopeptides. In our experimental system, the E. coli lipoprotein was half-maximally active at 3 nM (20 ng/ml), which is 3 orders of magnitude higher than the activity of mycoplasmal lipopeptides.

Which chemical features could cause this pronounced difference in MSA between mycoplasmal and “conventional” bacterial lipoproteins? Our initial notion, after the demonstration of S-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)cysteine as a constituent of the macrophage stimulator MDHM and in ignorance of the lack of N-acylation, was to ascribe the unexpectedly high specific activity of MDHM to the unusual fatty acid content of an at the time unknown mycoplasmal lipopeptide (30). However, a comparison of the MSA of natural MALP-2 from M. fermentans carrying heterogeneous fatty acids (C16:0, C18:0, and C18:1) with that of the synthetic substance (C16:0 only) showed that the two compounds were equally active (31). Our earlier data obtained with M. fermentans (31) and the present data obtained with M. hyorhinis strongly suggest that the higher stimulatory potential of lipoproteins from the genus Mycoplasma than that of lipoproteins from other bacteria is due to the lack of N-acylation. The influence of N-acylation on the macrophage-stimulatory potential was further confirmed by comparing the activity of the synthetic water-soluble lipohexapeptide S-[2(RS),3-bis(palmitoyloxy)propyl]-(R)-cysteinyl-SKKKK (MALP-A) having a free amino terminus with that of the corresponding N-palmitoylated derivative. N-acylation lowered the specific activity by a factor of 10, even when the substances were optimally detergent solubilized, and by a further order of magnitude when the substances were dissolved without detergent. The expression of lipoproteins and lipopeptides with a free amino terminus may be a general characteristic of the genus Mycoplasma, because the gene coding for the specific fatty acid N-acyl transferase was not detected in the genome of M. pneumoniae (18).

In conclusion, we would like to draw attention to some surprising common features of the lipopolysaccharide endotoxin of gram-negative bacteria (reviewed in reference 34) and mycoplasmal lipoproteins. The salient property of both type of compounds in the context of infection is, of course, their pronounced capacity to stimulate macrophages to synthesize cytokines and other mediators and their ability to cause inflammatory reactions. Beyond that, there is a common general building principle: (i) the two classes of compounds are anchored in the outer and plasma membrane, respectively, by a lipid moiety; (ii) it is this lipid moiety, the lipid A of endotoxin and the O-acylated amino terminal portion of mycoplasmal lipoproteins, respectively, which carries the inflammatory potential; and (iii) both classes of compounds exhibit repeating units of antigenic oligosaccharides or peptides, respectively, which are responsible for their reaction with antibodies. It appears that the innate immune system has learned during evolution to react to the lipid moieties by inflammation, thus alerting the immune system, whereas the microbes have evolved tactics to evade a specific immune response by varying their antigens (see also reference 6). Thus, lipoproteins and lipopeptides are likely to be the main causative agents of inflammatory reactions to mycoplasmas. This may be relevant in the context of mycoplasmas as arthritogenic pathogens and their association with AIDS. The importance of inflammatory host factors for the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus-induced disease has been emphasized in a recent review (10).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank V. Beier, C. Kamp, and T. Mühlradt for excellent technical assistance; G. R. Adolf (Bender & Co. GmbH, Vienna, Austria) for generously supplying us with recombinant gamma interferon; and K. Sachse (Bundesinstitut für Gesundheitlichen Verbraucherschutz, Jena, Germany) and M. Runge (Tierärztliche Hochschule Hannover, Hanover, Germany) for competent help in identifying the mycoplasmas. We also thank K. S. Wise for helping us by providing a set of monoclonal antibodies against variable lipoproteins from M. hyorhinis.

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Mu 672/2-2 and SFB 323-C2Ju).

REFERENCES

- 1.Baschang G. Muramylpeptides and lipopeptides: studies towards immunostimulants. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:6331–6360. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun V, Wu H C. Lipoproteins, structure, function, biosynthesis and model for protein export. In: Ghuysen J-M, Hakenbeck R, editors. Bacterial cell wall. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science BV; 1994. pp. 319–341. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner C, Wroblewski H, le Henaff M, Montagnier L, Blanchard A. Spiralin, a mycoplasmal membrane lipoprotein, induces T-cell-independent B-cell blastogenesis and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4322–4329. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4322-4329.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calcutt M J, Kim M F, Mühlradt P F, Wise K S. Proceedings of the IOM Meeting. 1998. The MALP-2 modulin of M. fermentans: gene cloning and strain variable biogenesis by post-translational processing from a larger lipoprotein abstr. E21; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chelmonska-Soyta A, Miller R B, Rosendal S. Activation of murine macrophages and lymphocytes by Ureaplasma diversum. Can J Vet Res. 1994;58:275–280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Citti C, Kim M F, Wise K S. Elongated versions of Vlp surface lipoproteins protect Mycoplasma hyorhinis escape variants from growth-inhibiting host antibodies. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1773–1785. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1773-1785.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen S L, Chait B T. Influence of matrix solution conditions on the MALDI-MS analysis of peptides and proteins. Anal Chem. 1996;68:31–37. doi: 10.1021/ac9507956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole B C, Knudtson K L, Oliphant A, Sawatzke A D, Pole A, Manohar M, Benson L S, Ahmed E, Atkin C L. The sequence of the Mycoplasma arthritidis superantigen MAM: identification of functional domains and comparison with microbial superantigens and plant lectin mitogens. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1105–1110. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duncan J R, Ross R F. Experimentally induced Mycoplasma hyorhinis arthritis of swine: pathologic responses to 26th postinoculation week. Am J Vet Res. 1973;34:363–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fauci A S. Host factors and the pathogenesis of HIV-induced disease. Nature. 1996;384:529–534. doi: 10.1038/384529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freundt E A. Culture media for mycoplasmas. Methods Mycoplasmol. 1983;1:127. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frisch M, Gradehandt G, Mühlradt P F. Mycoplasma fermentans-derived lipid inhibits class II major histocompatibility complex expression without mediation by interleukin-6, interleukin-10, tumor necrosis factor, transforming growth factor-β, type I interferon, prostaglandins or nitric oxide. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1050–1057. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallily R, Salman M, Tarshis M, Rottem S. Mycoplasma fermentans (incognitus strain) induces TNFα and IL-1 production by human monocytes and murine macrophages. Immunol Lett. 1992;34:27–30. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(92)90023-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauschildt S, Bassenge E, Bessler W, Busse R, Mulsch A. l-Arginine-dependent nitric oxide formation and nitrite release in bone marrow-derived macrophages stimulated with bacterial lipopeptide and lipopolysaccharide. Immunology. 1990;70:332–337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henderson B, Poole S, Wilson M. Bacterial modulins: a novel class of virulence factors which cause host tissue pathology by inducing cytokine synthesis. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:316–341. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.316-341.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herbelin A, Ruuth E, Delorme D, Michel-Herbelin C, Praz F. Mycoplasma arginini TUH-14 membrane lipoproteins induce production of interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha by human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4690–4694. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4690-4694.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hewick R M, Hunkapiller M W, Hood L E, Dreyer W J. A gas-liquid solid phase peptide and protein sequenator. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:7990–7997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Himmelreich R, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Pirkl E, Li B-C, Herrmann R. Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4420–4449. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffmann P, Heinle S, Schade U F, Loppnow H, Ulmer A J, Flad H-D, Jung G, Bessler W. Stimulation of human and murine adherent cells by bacterial lipoprotein and synthetic lipopeptide analogues. Immunobiology. 1988;177:158–170. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(88)80036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kita M, Ohmoto Y, Hirai Y, Yamaguchi N, Imanishi J. Induction of cytokines in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by mycoplasmas. Microbiol Immunol. 1992;36:507–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loewenstein J, Rottem S, Gallily R. Induction of macrophage-mediated cytolysis of neoplastic cells by mycoplasmas. Cell Immunol. 1983;77:290–297. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(83)90029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall A J, Miles R J, Richards L. The phagocytosis of mycoplasmas. J Med Microbiol. 1995;43:239–250. doi: 10.1099/00222615-43-4-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metzger J W, Wiesmüller K-H, Jung G. Synthesis of N-Fmoc protected derivatives of S-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)-cysteine and their application in peptide synthesis. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1991;38:545–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1991.tb01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metzger J W, Beck-Sickinger A G, Loleit M, Eckert M, Bessler W G, Jung G. Synthetic S-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)-cysteinyl peptides derived from the N-terminus of the cytochrome subunit of the photoreaction centre of Rhodopseudomonas viridis enhance murine splenocyte proliferation. J Pept Sci. 1995;3:184–190. doi: 10.1002/psc.310010305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monner D A, Gmeiner J, Mühlradt P F. Evidence from a carbohydrate incorporation assay for direct activation of bone marrow myelopoietic precursor cells by bacterial cell wall constituents. Infect Immun. 1981;31:957–964. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.957-964.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mühlradt P F, Frisch M. Purification and partial biochemical characterization of a Mycoplasma fermentans-derived substance that activates macrophages to release nitric oxide, tumor necrosis factor, and interleukin-6. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3801–3807. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3801-3807.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mühlradt P F, Schade U. MDHM, a macrophage-stimulatory product of Mycoplasma fermentans, leads to in vitro interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, tumor necrosis factor, and prostaglandin production and is pyrogenic in rabbits. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3969–3974. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3969-3974.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mühlradt P F, Quentmeier H, Schmitt E. Involvement of interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-2, and IL-4 in generation of cytolytic T cells from thymocytes stimulated by a Mycoplasma fermentans-derived product. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3962–3968. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3962-3968.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mühlradt P F, Meyer H, Jansen R. Identification of S-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)cystein in a macrophage-activating lipopeptide from Mycoplasma fermentans. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7781–7786. doi: 10.1021/bi9602831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mühlradt P F, Kiess M, Meyer H, Süssmuth R, Jung G. Isolation, structure elucidation, and synthesis of a macrophage stimulatory lipopeptide from Mycoplasma fermentans acting at pico molar concentration. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1951–1958. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.11.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norgard M V, Arndt L L, Akins D A, Curetty L L, Harrich D A, Radolf J D. Activation of human monocytic cells by Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins and synthetic lipopeptides proceeds via a different pathway distinct from that of lipopolysaccharide but involves the transcriptional activator NF-κB. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3845–3852. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3845-3852.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quentmeier H, Schmitt E, Kirchhoff H, Grote W, Mühlradt P F. Mycoplasma fermentans-derived high molecular weight material induces interleukin-6 release in cultures of murine macrophages and human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1273–1280. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1273-1280.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raetz C R H. Biochemistry of endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:129–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rawadi G, Roman-Roman S. Mycoplasma membrane lipoproteins induce proinflammatory cytokines by a mechanism distinct from that of lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1996;64:637–643. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.637-643.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruschmeyer D, Thude H J, Mühlradt P F. MDHM, a macrophage-activating product from Mycoplasma fermentans, stimulates murine macrophages to synthesize nitric oxide and become tumoricidal. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1993;7:223–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1993.tb00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruuth E, Praz F. Interactions between mycoplasmas and the immune system. Immunol Rev. 1989;112:133–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1989.tb00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaeverbeke T, Renaudin H, Clerc M, Lequen L, Vernhes J P, De Barbeyrac B, Bannwarth B, Bébéar C, Dehais J. Systematic detection of mycoplasmas by culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) procedures in 209 synovial fluid samples. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:310–314. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sher T, Rottem S, Gallily R. Mycoplasma capricolum membranes induce tumor necrosis factor α by a mechanism different from that of lipopolysaccharide. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1990;31:86–92. doi: 10.1007/BF01742371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sher T, Yamin A, Rottem S, Gallily R. In vitro induction of tumor necrosis factor α, tumor cytolysis and blast transformation by Spiroplasma membranes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1142–1145. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stuart P M, Egan R M, Woodward J G. Characterization of MHC induction by Mycoplasma fermentans (incognitus strain) Cell Immunol. 1993;152:261–270. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uno K, Takema M, Hidaka S, Tanaka R, Konishi T, Kato T, Nakamura S, Muramatsu S. Induction of antitumor activity in macrophages by mycoplasmas in concert with interferon. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1990;32:22–28. doi: 10.1007/BF01741720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wise K S, Kim M F, Theiss P M, Lo S-C. A family of strain-variant surface lipoproteins of Mycoplasma fermentans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3327–3333. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3327-3333.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang G, Coffman F D, Wheelock E F. Characterization and purification of a macrophage-triggering factor produced in Mycoplasma arginini-infected L5178Y cell cultures. J Immunol. 1994;153:2579–2591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yogev D, Rosengarten R, Watson McKown R, Wise K S. Molecular basis of Mycoplasma surface antigen variation: a novel set of divergent genes undergo spontaneous mutations of periodic coding regions and 5′ regulatory sequences. EMBO J. 1991;10:4069–4079. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yogev D, Watson-McKown R, Rosengarten R, Im J, Wise K S. Increased structural and combinatorial diversity in an extended family of genes encoding Vlp surface proteins of Mycoplasma hyorhinis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5636–5643. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5636-5643.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]