Persistent tracheal stoma before and after operation.

Central Message.

In this case, a persistent tracheal stoma was closed using a simple pedicled circular flap that epithelializes the surface facing the trachea, preventing recurrence and granuloma formation.

Tracheostomy is a common, routine thoracic surgical procedure.1,2 A persistent stoma—a residual lumen connecting the external environment and the airway that persists 3 to 6 months after decannulation3—can occur in up to 29% in adults,4 and even 54% of children.5 Herein, we present a case of a successfully closed persistent tracheal stoma using a pedicled skin flap, using the method described by Grillo.3

Case Report

A 66-year-old male patient with history of traumatic C6 fracture complicated by paraplegia, hypoxemic respiratory failure, extended critical illness, and tracheostomy placement was admitted to the medical service with pneumonia. He had been decannulated for just over 5 months. The site never healed.

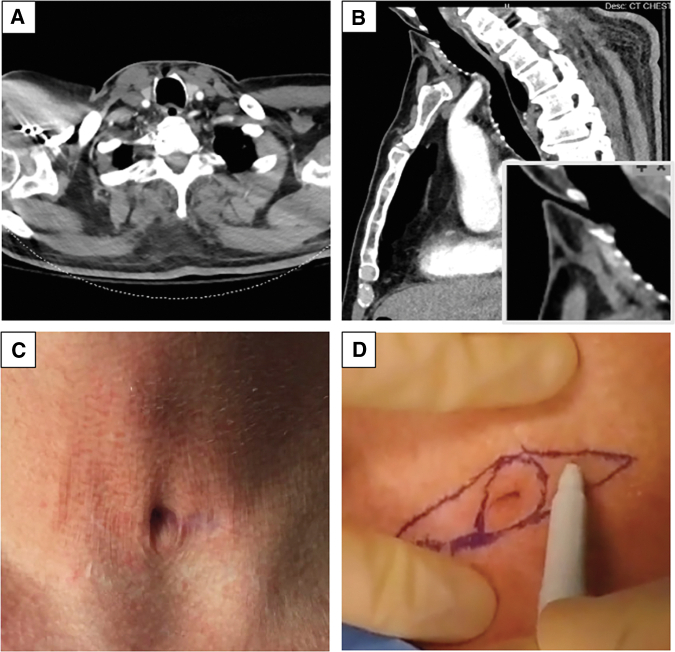

During admission, the thoracic surgery department was consulted to manage the patient's persistent stoma. The results of a computed tomography (CT) scan showed a tract of air from the anterior surface of the neck to the trachea (Figure 1, A and B). On examination, there was a stoma opening at the center of the previous trach cannula site (Figure 1, C). There was no surrounding erythema, tenderness, purulent drainage, or other signs of infection. There was no crepitus in the surrounding skin.

Figure 1.

Preoperative computed tomography (CT) and physical examination. A, Axial view showing a tracheocutaneous fistula. B, Sagittal view showing an oblique 3.5-mm wide, 2.5-cm long air-filled tract from the skin to the anterior trachea. C, Persistent tracheal stoma 5 months after decannulation and 2 nonsurgical closure attempts. D, Boundary markings of planned skin flap: circular marking immediately around stoma and transverse ellipse encompassing the circle.

In the operating room, a flexible bronchoscopy showed a pit in the anterior wall of the trachea, between the second and third tracheal rings. A well-epithelialized tract was visualized. The trachea appeared healthy in this area. There was no mass of granulation tissue, narrowing of the tracheal lumen, or tracheomalacia.

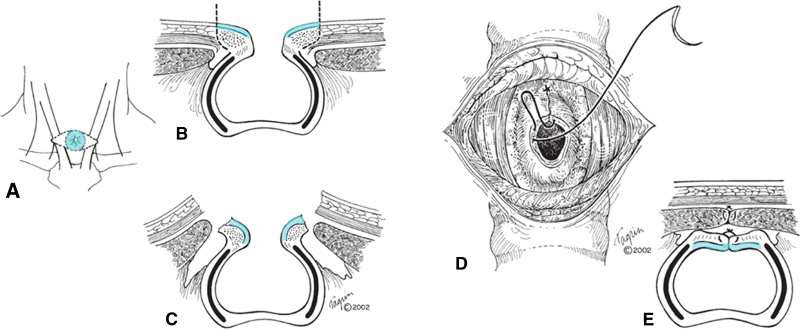

The anterior neck was prepped and draped in standard fashion. A circle was drawn immediately around the tracheal stoma, to indicate the boundaries of the planned pedicled skin flap, followed by a larger, transverse ellipse (Figure 1, D, and Figure 2, A). The skin was incised along the perimeter of the peristomal circle (Figure 2, B). The remaining areas of skin delineated by the boundaries of the ellipse were excised (Figure 2, C). The circular area of peristomal skin was undermined towards the stoma lumen, taking care to preserve the blood supply. The circle of skin was folded in half transversely, with the lumen of the stoma at the center and the 2 epidermal surfaces in contact with one another. The edges were secured with VICRYL stitches (Ethicon), with the epidermal surface facing the internal surface of the trachea (Figure 2, D). The strap muscles were approximated over the flap and the skin closed in layers (Figure 2, E). Skin glue was applied to create a water and air tight seal. The patient was discharged the following day. Twenty days later the incision had healed well. Six months following the operation, the patient's site of operation was well-healed with only a visible scar and no defects (Figure E1). The patient was diagnosed with left tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma 8 months after the operation and therefore has had many CT scans of the head and neck up to date. The CT image performed 2 years later (Figure E2, B) demonstrated no major difference from the CT image performed 3 months following surgery (Figure E2, A). A remaining defect in the anterior tracheal wall is still seen, but there is no extension of a tract to the cutaneous surface, proving successful and durable closure of the persistent tracheal stoma (Video 1).

Figure 2.

Figures from Grillo, describing the technique. Epidermis that is circumscribed as a pedicled flap and inverted over the tracheal opening is highlighted in blue. A, Location of pedicled peristomal skin flap, anterior view. B, Axial view of tracheal defect; dashed lines indicate lateral boundaries of skin flap, which will be incised. C, Axial view, with lateral edges of skin flap liberated from surrounding tissue, ready to be brought together over the defect. D, Edges of skin flap are brought together with absorbable suture. E, Final closure, with epidermis that was originally facing outward, now inverted, and providing closure over the tracheal defect.

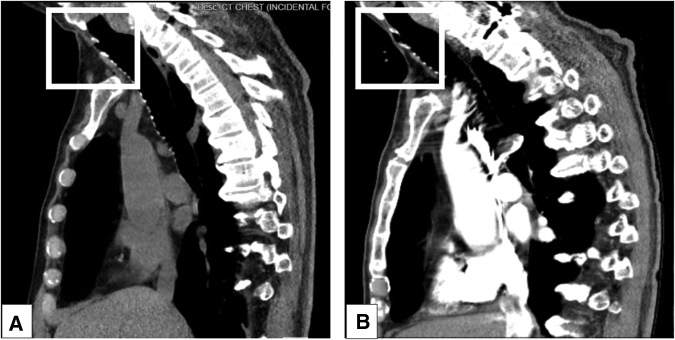

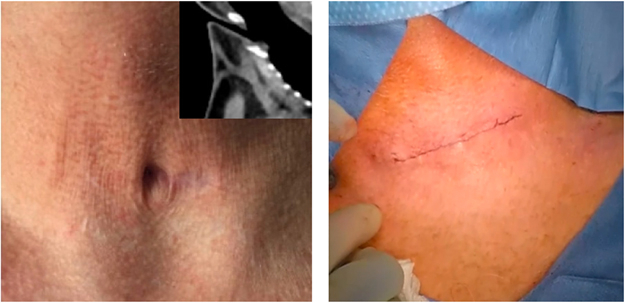

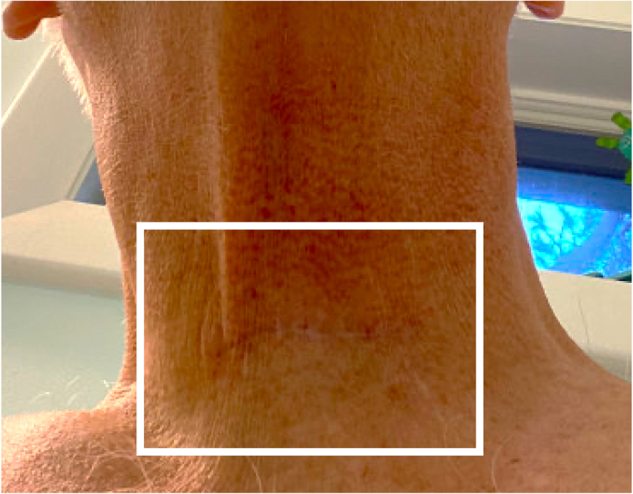

Figure E1.

Scar 6 months postoperatively after persistent tracheal stoma closure. Scar is visible, no defects.

Figure E2.

Postoperative computed tomography. A, Sagittal view 3 months' postoperatively showing a remaining defect in the anterior tracheal wall but no extension of a tract to the cutaneous surface. B, Sagittal view 2 years' postoperatively showing persistent anterior tracheal wall defect but still no tract to the cutaneous surface. Only a difference in the amount of soft tissue present anterior to the protrusion of the anterior airway seen.

This study is a review of medical records for a case report of one patient, not involving the formulation of a research hypothesis that is prospectively investigated, and therefore was exempt from Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board approval. The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of their data.

Discussion

Tracheostomy

An estimated 250,000 tracheostomies are performed annually in high-resource countries,E1 including approximately 10% of patients in the intensive care unit who require prolonged mechanical ventilation and 1.3% of all patients in the intensive care unit.E2 Median duration of tracheostomy is 16 daysE3 with 55% of patients decannulated before discharge.E3 At the peak of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, 8% of ventilated patients underwent tracheostomy; 34.9% of these patients were decannulated successfully, an average of 18 days after placement.E4 Compared with endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy reduces sedation needs; improves the ability of the patient to communicate with providers, family, and friends; increases mobility; and improves patient comfort.1

Persistent Tracheal Stoma/Tracheocutaneous Fistula

Tracheal stomas usually close without intervention after decannulation.E5 However, if squamous epithelium from the skin migrates along the stoma, toward the trachea, a persistent, nonhealing stoma may form.2,E6 Prolonged time in place, low nutritional status, and high-dose steroid use are risk factors for persistent stoma2,E7; 70% of tracheostomies in place longer than 16 weeks are associated with formation of a tracheocutaneous fistula. A persistent stoma increases the risk of aspiration, infection, and visible secretion of mucopurulent discharge, which impair patient quality of life.E3,E7

There are multiple methods to close persistent stomas,4,E8 including a rhomboid flap and Z-plasty,5,E3 a hinged skin flap,E9 a turnover flap,E10 and a pectoralis major musculocutaneous flap.E5 There is no standard method. Choice of method depends on surgeon experience and the size and complexity of the defect. Large amounts of scarring or decreased blood supply to the area can make closure more difficult. The method described by Shen and used here is a simple, one-stage method that closes the persistent tracheal stoma with a pedicled circular flap that epithelializes the surface facing the trachea.E7 This helps prevent the recurrence of a tracheocutaneous fistula and granuloma formation.3 Caution is taken while raising the margins of the circular flap to maintain adequate local blood supply,E7 which provides rapid healing postoperatively, minimal scarring, and nearly normal tissue fullness.E3

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they may have a conflict of interest. The editors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Data

Video of persistent tracheal stoma closure using a pedicled skin flap. Video available at: https://www.jtcvs.org/article/S2666-2507(23)00411-X/fulltext.

Appendix E1

References

- 1.Freeman B.D. Tracheostomy update: when and how. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33:311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe Y., Umehara T., Harada A., Aoki M., Tokunaga T., Suzuki S., et al. Successful closure of a tracheocutaneous fistula after tracheostomy using two skin flaps: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2015;1:2–4. doi: 10.1186/s40792-015-0045-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grillo H.C. Surgery of the Trachea and Bronchi. BC Decker; 2004. Tracheostomy, minitracheostomy, and closure of persistent stoma; pp. 499–506. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pignatti M., Sapino G., Alicandri-Ciufelli M., Canzano F., Presutti L., De Santis G. Treatment of recurrent tracheocutaneous fistulas in the irradiated neck with a two layers-two flaps combined technique. Indian J Plast Surg. 2020;53:423–426. doi: 10.1055/S-0040-1714769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernot S., Wadhera R., Kaintura M., Bhukar S., Pillai D.S., Sehrawat U., et al. Tracheocutaneous fistula closure: comparison of rhomboid flap repair with z plasty repair in a case series of 40 patients. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016;40:908–913. doi: 10.1007/s00266-016-0708-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

E-References

- Brenner M.J., Pandian V., Milliren C.E., Graham D.A., Zaga C., Morris L.L., et al. Global Tracheostomy Collaborative: data-driven improvements in patient safety through multidisciplinary teamwork, standardisation, education, and patient partnership. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:e104–e118. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischler L., Erhart S., Kleger G.R., Frutiger A. Prevalence of tracheostomy in ICU patients. A nation-wide survey in Switzerland. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1428–1433. doi: 10.1007/s001340000634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatekawa Y., Yamanaka H., Hasegawa T. Closure of a tracheocutaneous fistula by two hinged turnover skin flaps and a muscle flap: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito D.A., Bestourous D.E., Tong J.Y., Pasick L.J., Sataloff R.T. Tracheotomy in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weaning, decannulation, and survival. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;165:398–405. doi: 10.1177/0194599820984780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirakkal P., Al Hail A.N.I.H. Tracheocutaneous fistula—a surgical challenge. Clin Case Reports. 2021;9:1771–1773. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao C.N., Liu Y.W., Chang P.C., Chou S.H., Lee S.S., Kuo Y.R., et al. Decision algorithm and surgical strategies for managing tracheocutaneous fistula. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12:457–465. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2020.01.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen R., Mathisen D. Management of persistent tracheal stoma. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2003;13:369–373. doi: 10.1016/S1052-3359(03)00033-4. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q., Liu H., Lü S. A simple skin flap plasty to repair tracheocutaneous fistula after tracheotomy. Chin J Traumatol. 2015;18:46–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiyoshihara M., Nagashima T., Takeyoshi I. A novel technique for closing a tracheocutaneous fistula using a hinged skin flap. Surg Today. 2011;41:1166–1168. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4393-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.H., Zhao N., Lu J.W., Tang R.R., Liang C.N., Hou G. Large tracheocutaneous fistula successfully treated with bronchoscopic intervention and flap grafting: a case report and literature review. Front Med. 2020;7:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video of persistent tracheal stoma closure using a pedicled skin flap. Video available at: https://www.jtcvs.org/article/S2666-2507(23)00411-X/fulltext.