Abstract

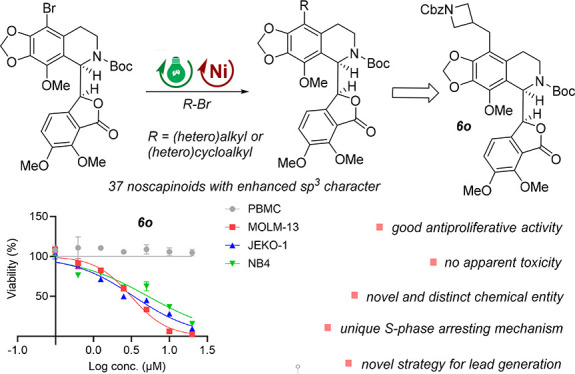

Herein, we disclose a powerful strategy for the functionalization of the antitumor natural alkaloid noscapine by utilizing photoredox/nickel dual-catalytic coupling technology. A small collection of 37 new noscapinoids with diverse (hetero)alkyl and (hetero)cycloalkyl groups and enhanced sp3 character was thus synthesized. Further in vitro antiproliferative activity screening and SAR study enabled the identification of 6o as a novel, potent, and less-toxic anticancer agent. Furthermore, 6o exerts superior cellular activity via an unexpected S-phase arrest mechanism and could significantly induce cell apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner, thereby further highlighting its potential in drug discovery as a promising lead compound.

Keywords: Noscapine, Photoredox/Nickel Dual Catalysis, Structure Modification, Anticancer Lead Compound, Drug Discovery

It is well-documented that increasing the number of sp3-hydridized carbons, and thus decreasing the planarity, is a strategy to enhance water solubility and improve druglike properties of compounds.1−4 Consequently, the degree of saturation tends to increase from the discovery through each stage of development to marketed drugs.1 In this context, the visible-light-induced photoredox/nickel dual catalysis, which enables the facile installation of sp3 character or alkyl groups onto aryl rings via the formation of a C(sp2)–C(sp3) bond under mild and environmentally benign conditions, has attracted great attention from both medicinal and synthetic chemists.5−8 Nonetheless, the application of this technology in parallel library synthesis and the pursuit of high-quality drug candidates are still relatively limited.

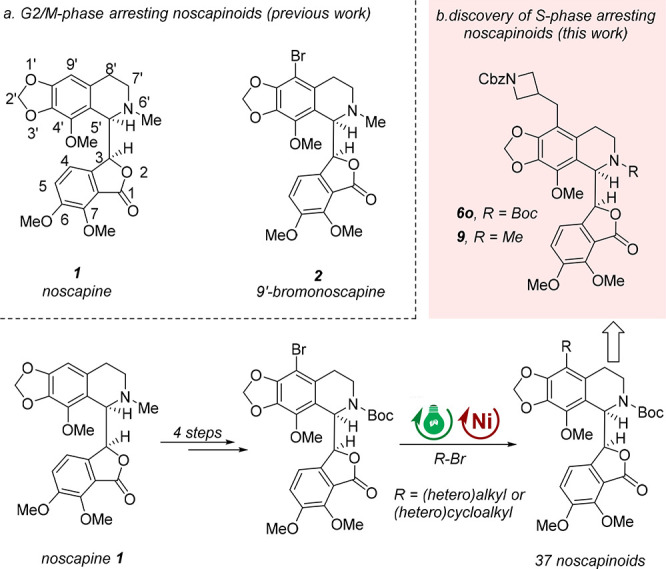

Noscapine 1, a phthalideisoquinoline alkaloid isolated from opium, has long been used orally in humans as an antitussive agent and has a favorable toxicity profile. In the late 1990s, it was discovered that noscapine also possesses weak anticancer activity against various cancer cell lines (IC50 = 25 μM in HeLa cells; IC50 = 42 μM in MCF-7 cells; IC50 = 39 μM in Renal cells 1983).9 It was found to cause cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase, induce apoptosis, and shrink tumors in vivo via the disruption of microtubule (MT) dynamics as a “kinder and gentler” tubulin-polymerization inhibitor (TPI) that does not cause any apparent toxicity.10−13 Since then, many structure modification campaigns have been performed. Among them, the chemical manipulation of the 9′-position on the isoquinoline ring system has shown significant improvement in therapeutic efficacy. A series of 9′-substituted noscapines, including 9′-nitronoscapine, 9′-aminonoscapine, 9′-azidenoscapine, 9′-arylnoscapine, 9′-alkynylnoscapine, and 9′-formylnoscapine, as well as halogenated (fluoro, chloro, bromo, and iodo) analogues, have displayed superior anticancer activity compared with the parent alkaloid noscapine in in vitro models (Figure 1a).14−22 In particular, the brominated analogue of noscapine, 9′-bromonoscapine 2, is highly potent against drug-resistant xenograft tumors without any detectable toxicity, thus displaying great potential for further drug discovery.23 It is worth noting that 9′-bromonoscapine 2 also functions as a G2/M phase arresting anticancer agent.24

Figure 1.

Structure modification of noscapine at the 9′-position.

However, the introduction of sp3-enriched (hetero)alkyl or (hetero)cycloalkyl groups, which are expected to enhance water solubility and improve druglike properties, has been less explored. This may be attributed to the limited accessibility of these valuable targets through classical cross-coupling technologies. Our group has been committed to the development and application of new and valuable photocatalytic transformations to streamline the drug discovery process.25−33 Herein, as part of our ongoing effort in this field, we wish to report the rapid derivatization of noscapine at the 9′-position using the novel photoredox/nickel dual-catalytic reductive coupling reaction starting from the readily accessible 9′-bromo-N-Boc-noscapine (Figure 1b).24,34,35 A small and focused library of noscapine analogues with diverse (hetero)alkyls or (hetero)cycloalkyls and enhanced sp3 character was thus synthesized. These analogues were then examined for their antiproliferative activity against representative cancer cell lines, including leukemia, lymphoma, lung, and cervical. Remarkably, hematological malignant cells demonstrated higher sensitivity to these analogues. Among them, the new analogues 6o and 9 with an N-Cbz-protected azetidine substituent showed superior activity in both leukemia and lymphoma cell lines, while no apparent toxicity against human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was observed. Interestingly, 6o exhibited an unexpected ability to induce S-phase arrest and caused significant apoptosis in human leukemia cells. This S-phase arresting mechanism is distinct from most reported noscapinoids, which typically induce the G2/M phase arrest. Therefore, the novel analogue 6o represents an attractive lead compound for further anticancer drug discovery.

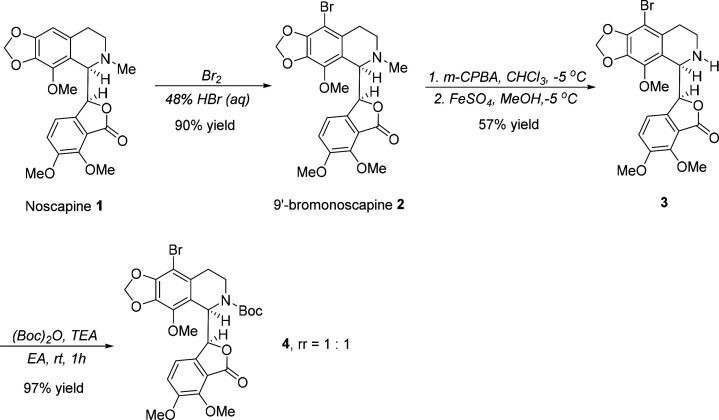

Amine groups are often not compatible with photoredox-catalyzed reactions because of its electron-rich and easily oxidized nature.36−39 Hence, a simple four-step procedure was explored for the synthesis of 9′-bromonoscapine analogue 4 (Scheme 1) where the Boc group was introduced on the nitrogen atom in place of the methyl group. As demonstrated, the bromination of noscapine 1 using bromine water in the presence of HBr (48%), as described previously, led to the generation of 9′-bromonoscapine 2 in an excellent yield. It was then converted to the corresponding N-oxide using a modified literature procedure, which employed more m-CPBA (4 equiv) at −5 °C. The resulting crude product was then treated with iron sulfate heptahydrate in methanol at the same temperature to afford 9′-bromo-N-nornoscapine 3 in an acceptable two-step yield. A Boc group was subsequently introduced to the nitrogen atom of 3 by using di-tert-butyl dicarbonate and triethylamine to provide the final product 9′-Br-N-Boc-noscapine 4 in a 97% yield. It should be noted that the presence of a Boc group at the nitrogen atom resulted in the generation of two rotamers with a ratio of 1:1, which was determined by 1H NMR analysis selecting a proton of the benzene ring for integration.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 9′-Br-N-Boc-noscapine 4.

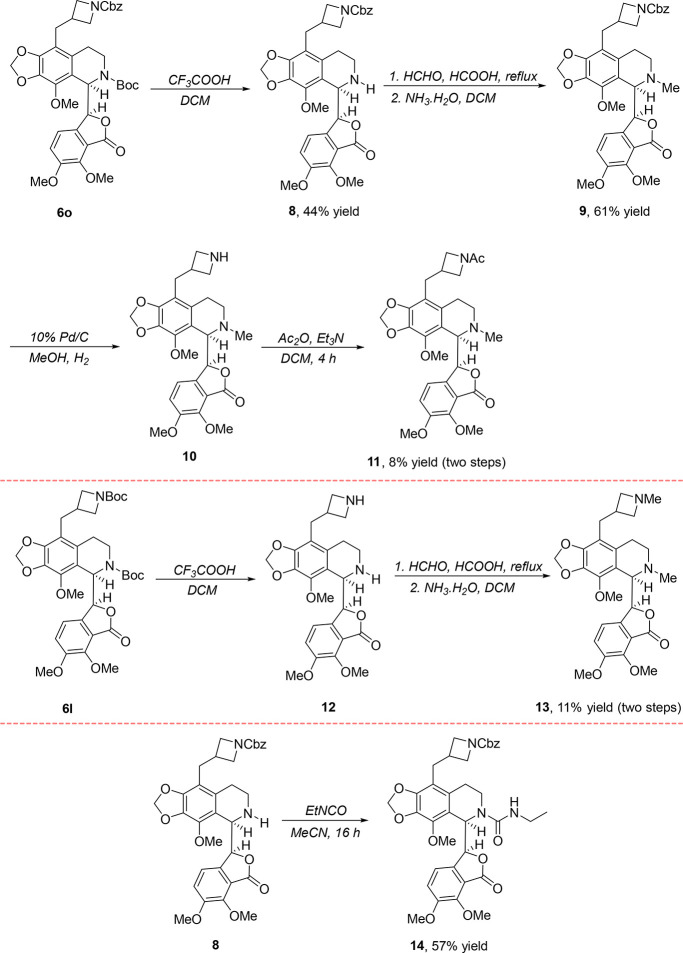

With 9′-bromo-N-Boc-noscapine 4 in hand, we then conducted a study to explore its application in photoredox/nickel dual-catalytic decarboxylative coupling reaction using tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-carboxylic acid 5a as the coupling partner, while only trace product was detected under a reported standard reaction condition (entry 1, Table 1).31 However, the reductive coupling of 4 and 4-bromotetrahydro-2H-pyran 5a′ using a described procedure resulted into the generation of desired product 6a in tractable yield (entry 1, 29% yield, Table S1), and the rotational selectivity (rr) was retained in the reaction.40 This outcome inspired us to systematically investigate the reaction. The screening of photocatalysts and nickel catalysts/ligands revealed that {Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)}PF6 (1 mol %) and NiCl2·glyme (5 mol %)/dtbbpy (5 mol %) were more favorable (entries 2–14, 13%–37% yields, Table S1). Switching the base from Na2CO3 to K2CO3, NaHCO3, and LiOH, which were commonly used in photoredox/nickel dual catalysis, could not further enhance the yield (entries 15–17, 29%–33% yields, Table S1).36,41,42 Further extensive screening of the reaction solvent and the amount of 5a′ led to further improvement of the reaction efficiency (entries 18–23, 27%–57% yields, Table S1). The optimal conditions were eventually identified as follows: in the presence of 34 W LEDs (light-emitting diodes), 1 mol % of {Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)}PF6, 5 mol % of NiCl2·glyme, 5 mol % of dtbbpy, 2 equiv of Na2CO3, and 1 equiv of tris(trimethylsilyl)silane (TTMMS), the reaction of 1 equiv of 4 with 2 equiv of 5a′ was conducted in DME for 16 h at 25 °C. Under these reaction conditions, the coupling product 6a was produced in high yield (entry 2, 57% yield, Table 1). However, as expected, 9′-bromonoscapine 2 was proved to be an ineffective reactant in the reaction (entry 3, Table 1).

Table 1. Investigation of the Cross-Coupling Reaction.

| entry | R′ | R″ | reaction conditions | product/yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Boc | CO2H | 34 W blue LED, 4CzIPN (5 mol %), NiBr2 (10 mol %), bpy (12 mol %), K2CO3 (2 equiv), 5a (1.5 equiv), DMF, 25 °C, N2, 16 h | 6a/trace30 |

| 2 | Boc | Br | 34 W blue LED, Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6 (1 mol %), NiCl2·glyme (5 mol %), dtbbpy (5 mol %), TTMSS (1 equiv), Na2CO3 (2 equiv), 5a′ (2.0 equiv), DME, N2, 25 °C, 16 h | 6a/57%39 |

| 3 | Me | Br | 34 W blue LED, Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6 (1 mol %), NiCl2·glyme (5 mmol %), dtbbpy (5 mmol %), TTMSS (1 equiv), Na2CO3 (2 equiv), 5a′ (2.0 equiv), DME, N2, 25 °C, 16 h | 6a′/n.d.39 |

Determined by 1H NMR analysis by selecting a Ar–H for integration.

n.d. = not detected.

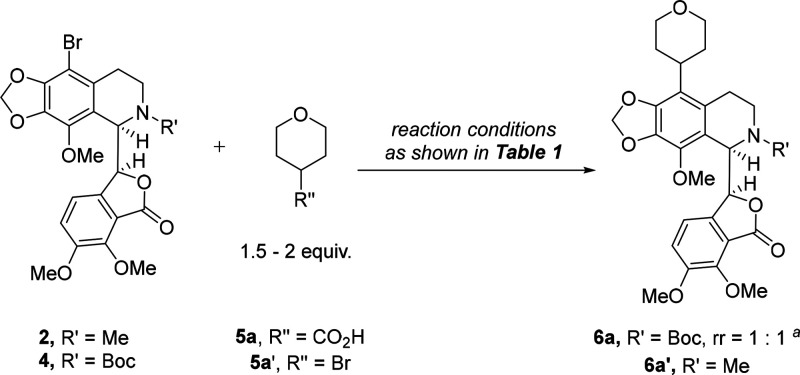

Having identified the optimal reaction conditions of the cross-coupling reaction (entry 2, Table 1), we next set out to synthesize N-Boc-noscapine derivatives with diverse (hetero)alkyl and (hetero)cycloalkyl groups at the 9′-position and to construct a focused library with enhanced sp3 character using the corresponding bromides, which are readily accessible in structural diversity (Scheme 2). As demonstrated, five- and four-membered oxygen-containing heterocycles could also be facilely introduced, which gave 6a–6c in comparable yields (44%–57%). However, oxygen-containing cycloalkylmethyl bromides typically displayed inferior reaction efficiency (6d–6e, 44%–48% yields). This can be explained by the fact that the secondary alkyl radical is more stable than the primary alkyl radical. Remarkably, nitrogen-containing cycloalkyl bromides and cycloalkylmethyl bromides are more reactive and provided 6f–6o in higher yields (40%–75%). Furthermore, the reactions of heteroalkyl bromides proceeded smoothly, albeit with diminished yields (6p–6v, 22%–60% yields). It is worth noting that various functional groups, such as cyano, silyl, methoxyl, trifluoromethyl, and phosphate groups, were well-tolerated, which further highlights the powerful capacity of photoredox/nickel dual catalysis for diverse chemical modifications of complex drug molecules. Finally, alkyl and cycloalkyl bromides were also proved to be suitable substrates, while lower yields were typically achieved (7a–7o, 7%–53% yields). Unexpectedly, lower yields were typically observed in the reaction of cycloalkyl bromides (7a–7h, 7%–22% yields).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Various 9′-(Hetero)alkyl- and 9′-(Hetero)cycloalkyl-N-Boc-noscapines.

See general procedure in the Supporting Information for details.

Determined by 1H NMR by selecting a Ar–H for integration.

Diastereoisomer ratio (dr) was determined by 1H NMR by selecting a Ar–H for integration, and the dr value of the products is about 1:1.

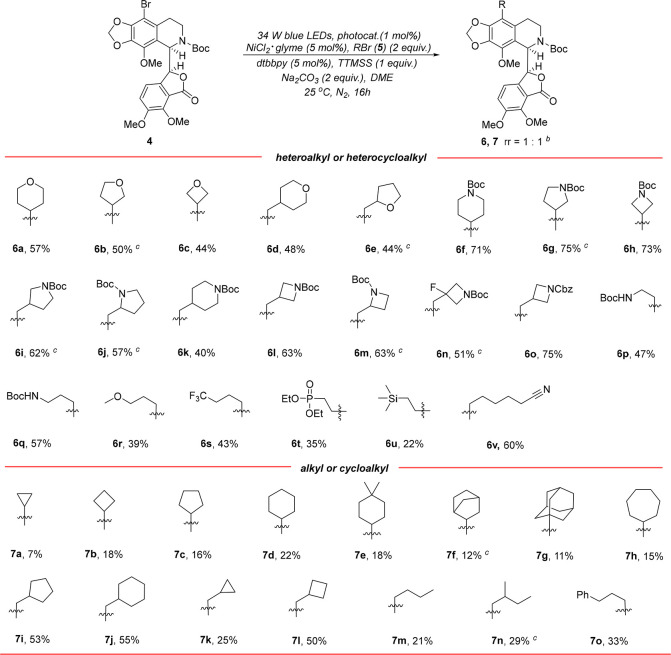

As shown in Table 2, an initial examination of antiproliferative activity of the newly synthesized compounds 6a–6v and 7a–7o against representative cancer cell lines revealed that compound 6o with an N-Cbz-protected azetidine substituent showed superior activity. Therefore, various analogues of 6o were designed and prepared to further investigate the structure–activity relationship (SAR) (Scheme 3). The treatment of 6o with TFA in DCM for 0.5 h enabled the formation of N-nornoscapine derivative 8 in moderate yield, which was then converted to compound 9 in 60% yield via a known methylation protocol.43 However, the removal of Cbz from the nitrogen atom of 9 did not proceed well, and most of the starting materials was recovered. As a result, the final product 11 was obtained in only an 8% two-step yield. Furthermore, starting from 6l, a similar two-step procedure for the synthesis of compound 13 was explored, and only 11% of a two-step yield was achieved because of the low reaction efficiency of the N-deprotection step. Finally, the treatment of 8 with isocyanatoethane resulted into the formation of compound 14 in 57% yield.

Table 2. Effect of N-Boc-Noscapine Analogues 6a–6v and 7a–7o on the Proliferation of Cancer Cellsa.

| compound | growth

inhibition (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB4 | MOLM-13 | Jeko-1 | A549 | HeLa | U251 | |

| 6a | 4.36 | 36.79 | 11.97 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6b | 23.32 | 43.61 | 20.77 | <5.00 | <5.00 | 32.15 |

| 6c | 9.21 | 11.66 | 13.35 | <5.00 | 14.94 | 12.29 |

| 6d | 4.77 | 48.35 | 20.38 | <5.00 | 22.96 | 13.15 |

| 6e | 7.48 | 44.86 | 15.64 | <5.00 | 24.72 | 29.75 |

| 6f | 21.17 | 62.85 | 22.28 | 14.67 | 17.47 | <5.00 |

| 6g | 22.11 | 54.78 | 14.92 | 17.74 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6h | 30.12 | 49.74 | 17.63 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6i | 23.18 | 52.46 | 7.92 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6j | 29.69 | 48.11 | 15.71 | <5.00 | 8.57 | <5.00 |

| 6k | 37.34 | 58.12 | 22.67 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6l | 63.14 | 58.97 | 47.97 | 10.57 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6m | 13.77 | 43.23 | 12.89 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6n | 42.50 | 61.53 | 43.94 | <5.00 | 8.57 | <5.00 |

| 6o | 60.52 | 79.83 | 74.32 | 56.96 | 62.73 | 37.14 |

| 6p | 29.92 | 43.46 | 14.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6q | 28.93 | 48.19 | 10.64 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6r | 27.20 | 30.35 | 23.26 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6s | 31.49 | 36.01 | 25.55 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6t | 6.64 | 31.05 | 12.10 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6u | 21.93 | 46.87 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 6v | 14.05 | 46.33 | 19.91 | <5.00 | 16.15 | 19.10 |

| 7a | 7.63 | 19.49 | 6.87 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 7b | 13.53 | 40.43 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 7c | 11.61 | 40.05 | 5.81 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 7d | 6.53 | 46.10 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 7e | 29.57 | 47.65 | 7.49 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 7f | 15.00 | 48.58 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 7g | <5.00 | 17.63 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 7h | <5.00 | 39.43 | 10.32 | <5.00 | <5.00 | 20.54 |

| 7i | 20.76 | 51.29 | 6.68 | <5.00 | <5.00 | 12.00 |

| 7j | <5.00 | 29.27 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 7k | 8.20 | 43.61 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 7l | 8.80 | 53.08 | 6.67 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 7m | 10.01 | 48.58 | 11.44 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 7n | 9.33 | 51.22 | 23.98 | <5.00 | 6.92 | <5.00 |

| 7o | 25.11 | 63.16 | 13.65 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 1 | 26.70 | 18.96 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 | <5.00 |

| 2 | 38.30 | 41.91 | 48.90 | 15.92 | 28.13 | <5.00 |

| gemcitinibine | 95.66 | 74.10 | 65.17 | 62.32 | 61.42 | 69.68 |

Inhibition rates were reported at a concentration of 10 μM.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of the Analogues of 6o.

The newly synthesized small collection of noscapinoids with diverse 9′-(hetero)alkyl or 9′-(hetero)cycloalkyl groups were then tested for their antiproliferative activity against six cancer cell lines using the CCK-8 assay, and the inhibition rates at a concentration of 10 μM were reported in Table 2. Noscapine 1 and 9′-bromonoscapine 2 were used as the reference standards. Gemcitabine was used as a positive control. The results demonstrated that most of these compounds exhibited higher activity against a panel of malignant hematological cell lines, such as NB4 (acute promyeloid leukemia cell line), MOLM-13 (acute myeloid leukemia cell line), and JEKO-1 (human mantle cell lymphoma cell line), compared with solid tumor cell lines, including A549 (human lung cancer cell line), HeLa (human cervical cancer cell line), and U251 (glioma cell line). Remarkably, the new noscapine derivatives with an N-Boc-containing cycloalkyl or alkyl at the 9′-position typically showed higher inhibitory activity against three representative malignant hematological cell lines (6f–6q) compared with other types of new derivatives. This result indicates that the N-Boc group may play an important role in determining the biological activity in cellular systems. In particular, the introduction of an extra CH2 between the N-Boc-protected azetidine (C3) and the benzene ring of N-Boc-noscapine led to a significant increase in antiproliferative ability (6l vs 6h). Nonetheless, both switching the substituted position from C3 to C2 and introducing an extra F at C3 resulted in diminished activity (6m–6n). Interestingly, the change of the N-protecting group from Boc to Cbz provided a more potent anticancer agent 6o. Furthermore, this new compound also exhibited high inhibitory activity against three solid tumor cell lines at the concentration of 10 μM. It is worth noting that 6o also displayed comparable antiproliferative activity to 9′-bromonoscapine 2, which is one of the most potent noscapine derivatives reported, and has displayed great potential for further drug discovery.23

To further validate the antiproliferative activity of 6o, the IC50 value (half-maximal growth inhibitory concentration) against malignant cancer cell line was determined. The results showed that 6o exhibited potent activity against the tested three malignant hematological cell lines (MOLM-13, NB4, and Jeko-1) with IC50 values ranging from 3.12 to 5.25 μM (Table 3). Further structure–activity relationship (SAR) study revealed that the removal of Boc from the nitrogen atom of 6o resulted into a slight decrease of activity (8, Table 3). Conversely, the replacement of Boc with a methyl group afforded compound 9 with comparable IC50 values in MOLM-13 and Jeko-1 cells. However, switching the protecting group of azetidine from Cbz to acyl and methyl was detrimental to the activity (11 and 13, Table 3). Furthermore, the installation of an ethylcarbamoyl group at the N6-position in place of Boc, which was shown to significantly enhance the anticancer potency, according to the work of Scammells et al.,44 failed to further improve the activity (14, Table 3). Overall, these findings suggest that 6o is a potent anticancer agent and demonstrates superior antiproliferative activity compared with 9′-bromonoscapine (6o vs 2). Additionally, the change of the N-protecting group (6′-position) has little effect on the outcome.

Table 3. IC50 Values of New Noscapinoids against Malignant Hematological Cell Lines.

| compounds | IC50 (μmol·L–1) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| NB4 | MOLM-13 | Jeko-1 | |

| 6o | 5.25 ± 0.61 | 3.12 ± 0.05 | 3.39 ± 0.04 |

| 8 | 13.24 ± 1.26 | 7.78 ± 1.14 | 7.57 ± 0.34 |

| 9 | 10.74 ± 0.007 | 4.37 ± 0.22 | 5.11 ± 0.12 |

| 11 | >20 | >20 | >20 |

| 13 | >20 | >20 | >20 |

| 14 | 10.41 ± 1.43 | 6.47 ± 0.22 | 6.97 ± 1.16 |

| 1 | >20 | >20 | >20 |

| 2 | 16.27 ± 0.98 | 15.28 ± 0.09 | 11.50 ± 0.11 |

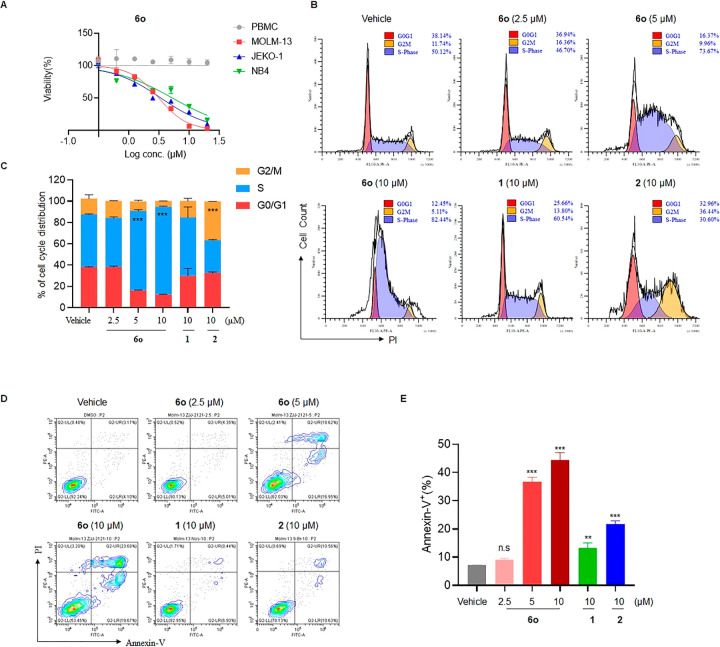

As mentioned above, 6o exhibited potent anticancer activity against several human cancer cell lines in vitro. In contrast, no significant cytotoxicity of compound 6o was observed against normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), thereby indicating its selectivity toward cancer cells (Figure 2A). To further elucidate the anticancer mechanism of action of 6o, the cell-cycle progression and the cell apoptotic behavior with 6o treatment were evaluated. Flow-cytometric analysis using the DNA-intercalating dye propidium iodide (PI) was employed to assess cell cycle distribution. As demonstrated in Figure 2B,C, treatment with 6o significantly induced S-phase arrest in MOML-13 cells in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, treatment with 9′-bromonoscapine 2 at 10 μM resulted in a substantial G2/M phase arrest, while noscapine treatment at the same dose induced only a marginal increase in the G2/M phase. This observation was in line with previous studies reporting that noscapine 1 and 9′-bromonoscapine 2 exerted anticancer activity by affecting tubulin polymerization and that 2 was more potent than noscapine 1 as a microtubule polymerization inhibitor.23 Moreover, our findings also suggest that 6o, as a novel noscapine derivative that preferentially induces S-phase arrest, may possess a unique mechanism of action distinct from noscapine 1 and 9′-bromonoscapine 2. It is noted that Anderson and co-workers have reported a class of S-phase arresting agents by structural modification of noscapine at the 7-position where a benzyl group was typically introduced in place of a methyl group at the oxygen atom.45,46 However, the structures of these O-benzylated noscapine derivatives are totally different from those of 6o, which suggests that these two classes of noscapinoids might function via different mechanisms of action to induce S-phase arrest. Further investigations of the underlying mechanism utilizing 6o as a probe are ongoing in our lab, which might not only contribute to the development of an innovative drug with potential new therapeutic target and mechanism but also facilitate a broader understanding of the structure–activity relationship (SAR) associated with noscapine modifications. Next, the Annexin-V/PI double-staining assay was used to assess cell apoptosis, and our result showed that 6o treatment significantly induced cell apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2D,E). It is noted that 6o demonstrated the highest potency in inducing apoptosis compared with noscapine 1 and 9′-bromonoscapine 2 at an equivalent dose of 10 μM, thereby demonstrating its stronger apoptosis-inducing potential.

Figure 2.

6o induced S phase arrest and promoted apoptosis. (A) Malignant hematopoietic cancer cell lines MOML-13, JEKO-1, NB4 cells, and normal PBMC cells were treated with 6o at different doses, and growth inhibition was evaluated by a CCK-8 assay. (B,C) MOML-13 cells were incubated with 6o at different doses and 10 μM of 1 and 2 for 24 h, and the cell cycle distribution was evaluated on the basis of analysis of cellular DNA content following cell staining with propidium iodide (B). Percentages of cell populations in G0/G1, G2/M, and S-phases of the cells are shown in (C). (D,E) MOML-13 cells were incubated with 6o at different doses and 10 μM of 1 and 2 for 48 h, and the apoptosis-inducing activity was evaluated by Annexin-V/PI staining (D). The percent of Annexin-V+ cells was quantified, including the early-stage apoptotic cell population (Annexin-V+ PI–) and late-stage apoptotic cell population (Annexin-V+ PI+) (E). Error bars represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples in an independent experiment. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed t test: P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), and P < 0.001 (***) against the vehicle-treated group. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the structure modification of natural antitumor alkaloid noscapine by utilizing the photoredox/nickel dual-catalytic reductive coupling technology. A small collection of noscapinoids with diverse 9′-(hetero)alkyl and 9′-(hetero)cycloalkyl and enhanced sp3 character and druglike properties was thus synthesized, which enabled the further identification of a novel, potent, and less toxic anticancer agent 6o via in vitro antiproliferative activity screening. Notably, cell cycle analysis and apoptosis assay revealed that 6o induced an unexpected S-phase arrest and significantly promoted apoptosis in vitro. These results suggest that this compound may possess a distinct mechanism of action in comparison with noscapine 1 and its brominated congener 2, thus representing a promising lead compound for anticancer drug discovery. Furthermore, it should be noted that the lead-generation approach embedded in this study is novel and useful and would find a broad application in drug discovery program.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21602060, 21871086, and 22171080, Y.Z.) and Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai Municipality (23ZR1417200, Y.Z.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PBMCs

human peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- LED

light-emitting diode

- TTMMS

tris(trimethylsilyl)silane

- PI

propidium iodide

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00462.

General procedures for the synthesis of target compounds, 1H and 13C NMR spectra, and other characterization data for all target compounds prepared (PDF)

Author Contributions

⊥ D.L., C.L., and T.G. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lovering F.; Bikker J.; Humblet C. Escape from flatland: Increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52 (21), 6752–6756. 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W.; Cherukupalli S.; Jing L.; Liu X.; Zhan P. Fsp3: A new parameter for drug-likeness. Drug Discovery Today 2020, 25 (10), 1839–1845. 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M.; Hashimoto Y. Improvement in aqueous solubility in small molecule drug discovery programs by disruption of molecular planarity and symmetry. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54 (6), 1539–1554. 10.1021/jm101356p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talele T. T. Opportunities for tapping into three-dimensional chemical space through a quaternary carbon. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (22), 13291–13315. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R.; Li G.; Wismer M.; Vachal P.; Colletti S. L.; Shi Z. C. Profiling and application of photoredox Csp3-Csp2 cross-coupling in medicinal chemistry. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9 (7), 773–777. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P. P.; Singh P. K.; Srivastava V. Visible light metallaphotoredox catalysis in the late-stage functionalization of pharmaceutically potent compounds. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 10 (1), 216–236. 10.1039/D2QO01582J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski A. W.; Gesmundo N. J.; Aguirre A. L.; Sarris K. A.; Young J. M.; Bogdan A. R.; Martin M. C.; Gedeon S.; Wang Y. Expanding the medicinal chemist toolbox: Comparing seven Csp2-Csp3 cross-coupling methods by library synthesis. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11 (4), 597–604. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins J. J.; Shurtleff V. W.; Johnson A. M.; El Marrouni A. Synthesis of C6-substituted purine nucleoside analogues via late-stage photoredox/nickel dual catalytic cross-coupling. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12 (4), 662–666. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye K.; Ke Y.; Keshava N.; Shanks J.; Kapp J. A.; Tekmal R. R.; Petros J.; Joshi H. C. Opium alkaloid noscapine is an antitumor agent that arrests metaphase and induces apoptosis in dividing cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95 (4), 1601–1606. 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomar V.; Kukreti S.; Prakash S.; Madan J.; Chandra R. Noscapine and its analogs as chemotherapeutic agent: Current updates. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016, 17 (2), 174–188. 10.2174/1568026616666160530153518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rida P. C.; LiVecche D.; Ogden A.; Zhou J.; Aneja R. The noscapine chronicle: A pharmaco-historic biography of the opiate alkaloid family and its clinical applications. Med. Res. Rev. 2015, 35 (5), 1072–1096. 10.1002/med.21357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudian M.; Rahimi-Moghaddam P. The anti-cancer activity of noscapine: A review. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discovery 2009, 4 (1), 92–97. 10.2174/157489209787002524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altinoz M. A.; Topcu G.; Hacimuftuoglu A.; Ozpinar A.; Ozpinar A.; Hacker E.; Elmaci İ. Noscapine, a non-addictive opioid and microtubule-inhibitor in potential treatment of glioblastoma. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44 (8), 1796–1806. 10.1007/s11064-019-02837-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneja R.; Vangapandu S. N.; Lopus M.; Viswesarappa V. G.; Dhiman N.; Verma A.; Chandra R.; Panda D.; Joshi H. C. Synthesis of microtubule-interfering halogenated noscapine analogs that perturb mitosis in cancer cells followed by cell death. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 72 (4), 415–426. 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma A. K.; Bansal S.; Singh J.; Tiwari R. K.; Kasi Sankar V.; Tandon V.; Chandra R. Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity of haloderivatives of noscapine. Biorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14 (19), 6733–6736. 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneja R.; Vangapandu S. N.; Joshi H. C. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a cyclic ether fluorinated noscapine analog. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14 (24), 8352–8358. 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneja R.; Vangapandu S. N.; Lopus M.; Chandra R.; Panda D.; Joshi H. C. Development of a novel nitro-derivative of noscapine for the potential treatment of drug-resistant ovarian cancer and T-cell lymphoma. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 69 (6), 1801–1809. 10.1124/mol.105.021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik P. K.; Chatterji B. P.; Vangapandu S. N.; Aneja R.; Chandra R.; Kanteveri S.; Joshi H. C. Rational design, synthesis and biological evaluations of amino-noscapine: A high affinity tubulin-binding noscapinoid. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2011, 25 (5), 443–454. 10.1007/s10822-011-9430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcù E.; Sipos A.; Basso G.; Hamel E.; Bai R.; Stempfer V.; Udvardy A.; Bényei A. C.; Schmidhammer H.; Antus S.; Viola G. Novel 9’-substituted-noscapines: Synthesis with Suzuki cross-coupling, structure elucidation and biological evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 84, 476–490. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoshi S.; Naik P. K.; Joshi H. C. Rational design of novel anti-microtubule agent (9-azido-noscapine) from quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR) evaluation of noscapinoids. J. Biomol. Screen. 2011, 16 (9), 1047–1058. 10.1177/1087057111418654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagireddy P. K. R.; Kommalapati V. K.; Manchukonda N. K.; Sridhar B.; Tangutur A. D.; Kantevari S. Synthesis and antiproliferative activity of 9-formyl and 9-ethynyl noscapines. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4 (14), 4092–4096. 10.1002/slct.201900666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagireddy P. K. R.; Sridhar B.; Kantevari S. Copper-catalyzed glaser-hey-type cross coupling of 9-ethynyl-α-noscapine leading to unsymmetrical 1,3-diynyl noscapinoids. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2019, 8 (8), 1495–1500. 10.1002/ajoc.201900316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi H. C.; Ye K.; Kapp J.; Landen J.; Archer D.; Armstrong C.; Liu F.. Delivery systems and methods for noscapine and noscapine derivatives, useful as anticancer agents. US 20020137762 A1, 2002.

- Zhou J.; Gupta K.; Aggarwal S.; Aneja R.; Chandra R.; Panda D.; Joshi H. C. Brominated derivatives of noscapine are potent microtubule-interfering agents that perturb mitosis and inhibit cell proliferation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 63 (4), 799. 10.1124/mol.63.4.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y.; Zhu J.; Yuan Q.; Wang W.; Zhang Y. Synthesis of β-silyl α-amino acids via visible-light-mediated hydrosilylation. Org. Lett. 2021, 23 (4), 1406–1410. 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Wan Y.; Yuan Q.; Wei J.; Zhang Y. Photocatalytic C-Si bond formations using pentacoordinate silylsilicates as silyl radical precursors: Synthetic tricks using old reagents. Org. Lett. 2023, 25 (9), 1386–1391. 10.1021/acs.orglett.3c00096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Liu C.; Guo S.; Wang W.; Zhang Y. Pifa-mediated cross-dehydrogenative coupling of N-heteroarenes with cyclic ethers: Ethanol as an efficient promoter. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 2021 (3), 411–421. 10.1002/ejoc.202001354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y.; Zhao Y.; Zhu J.; Yuan Q.; Wang W.; Zhang Y. Organophotocatalytic silyl transfer of silylboranes enabled by methanol association: A versatile strategy for C-Si bond construction. Green. Chem. 2023, 25 (1), 256–263. 10.1039/D2GC03577D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Liu A.; Zhang Y.; Wang W. Direct Cα-heteroarylation of structurally diverse ethers via a mild N-hydroxysuccinimide mediated cross-dehydrogenative coupling reaction. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 4044. 10.1039/C6SC05697K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K.; Ma Y.; Liu S.; Guo S.; Zhang Y. Highly stereoselective C-glycosylation by photocatalytic decarboxylative alkynylation on anomeric position: A facile access to alkynyl C-glycosides. Chin. J. Chem. 2022, 40, 681–686. 10.1002/cjoc.202100438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Liu S.; Xi Y.; Li H.; Yang K.; Cheng Z.; Wang W.; Zhang Y. Highly stereoselective synthesis of aryl/heteroaryl-C-nucleosides via the merger of photoredox and nickel catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 14657–14660. 10.1039/C9CC07184A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Pan P.; Fan H.; Li H.; Wang W.; Zhang Y. Photocatalytic C-H silylation of heteroarenes by using trialkylhydrosilanes. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 3817. 10.1039/C9SC00046A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J.; Wang Y.; Li Y.; Lu K.; Liu S.; Wang W.; Zhang Y. Graphitic carbon nitride polymer as a recyclable photoredox catalyst for decarboxylative alkynylation of carboxylic acids. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 3898. 10.1002/adsc.202000777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCamley K.; Ripper J. A.; Singer R. D.; Scammells P. J. Efficient N-demethylation of opiate alkaloids using a modified nonclassical polonovski reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68 (25), 9847–9850. 10.1021/jo035243z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal S.; Ghosh N. N.; Aneja R.; Joshi H.; Chandra R. A convenient synthesis of aryl-substituted N-carbamoyl/N-thiocarbamoyl narcotine and related compounds. Helv. Chim. Acta 2002, 85 (8), 2458–2462. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Z.; Ahneman D. T.; Chu L.; Terrett J. A.; Doyle A. G.; MacMillan D. W. C. Merging photoredox with nickel catalysis: Coupling of α-carboxyl sp3-carbons with aryl halides. Science 2014, 345 (6195), 437–440. 10.1126/science.1255525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahneman D. T.; Doyle A. G. C-h functionalization of amines with aryl halides by nickel-photoredox catalysis. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7 (12), 7002–7006. 10.1039/C6SC02815B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw M. H.; Shurtleff V. W.; Terrett J. A.; Cuthbertson J. D.; MacMillan D. W. C. Native functionality in triple catalytic cross-coupling: Sp3 C-H bonds as latent nucleophiles. Science 2016, 352 (6291), 1304–1308. 10.1126/science.aaf6635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey J. L.; Terrett J. A.; MacMillan D. W. C. O-h hydrogen bonding promotes H-atom transfer from α C-H bonds for C-alkylation of alcohols. Science 2015, 349 (6255), 1532–1536. 10.1126/science.aac8555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P.; Le C. C.; MacMillan D. W. C. Silyl radical activation of alkyl halides in metallaphotoredox catalysis: A unique pathway for cross-electrophile coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (26), 8084–8087. 10.1021/jacs.6b04818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu L.; Lipshultz J. M.; MacMillan D. W. C. Merging photoredox and nickel catalysis: The direct synthesis of ketones by the decarboxylative arylation of α-oxo acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (27), 7929–7933. 10.1002/anie.201501908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrett J. A.; Cuthbertson J. D.; Shurtleff V. W.; MacMillan D. W. C. Switching on elusive organometallic mechanisms with photoredox catalysis. Nature 2015, 524 (7565), 330–334. 10.1038/nature14875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederich M.; Nubbemeyer U. Synthesis of optically active nine-membered ring lactams by a zwitterionic aza-claisen reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34 (9), 1026–1028. 10.1002/anie.199510261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debono A. J.; Mistry S. J.; Xie J.; Muthiah D.; Phillips J.; Ventura S.; Callaghan R.; Pouton C. W.; Capuano B.; Scammells P. J. The synthesis and biological evaluation of multifunctionalised derivatives of noscapine as cytotoxic agents. ChemMedChem. 2014, 9 (2), 399–410. 10.1002/cmdc.201300395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. T.; Ting A. E.; Boozer S.; Brunden K. R.; Crumrine C.; Danzig J.; Dent T.; Faga L.; Harrington J. J.; Hodnick W. F.; Murphy S. M.; Pawlowski G.; Perry R.; Raber A.; Rundlett S. E.; Stricker-Krongrad A.; Wang J.; Bennani Y. L. Identification of novel and improved antimitotic agents derived from noscapine. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48 (23), 7096–7098. 10.1021/jm050674q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. T.; Ting A. E.; Boozer S.; Brunden K. R.; Danzig J.; Dent T.; Harrington J. J.; Murphy S. M.; Perry R.; Raber A.; Rundlett S. E.; Wang J.; Wang N.; Bennani Y. L. Discovery of S-phase arresting agents derived from noscapine. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48 (8), 2756–2758. 10.1021/jm0494220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.