Abstract

We have designed and developed novel and selective TLR7 agonists that exhibited potent receptor activity in a cell-based reporter assay. In vitro, these agonists significantly induced secretion of cytokines IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10, TNFa, IFNa, and IP-10 in human and mouse whole blood. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies in mice showed a significant secretion of IFNα and TNFα cytokines. When combined with aPD1 in a CT-26 tumor model, the lead compound showed strong synergistic antitumor activity with complete tumor regression in 8/10 mice dosed using the intravenous route. Structure–activity relationship studies enabled by structure-based designs of TLR7 agonists are disclosed.

Keywords: TLR7 agonist, tumor, immuno-oncology, cancer, PD1

Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint-blockade has transformed the field of immuno-oncology.1 Currently, there are 8 FDA-approved checkpoint inhibitors (Yervoy, Opdivo, Keytruda, Tecentriq, Bavencio, Imfinzi, Libtayo, and Opdualag). Despite clinical success, these agents are effective only in a small subset of immunologically inflamed “hot” tumors.2 To enhance the antitumor activity of checkpoint blockade agents, several rational drug combination studies are being explored in clinic that can turn immunologically cold tumor hot.3 Of particular note is the use of immune adjuvants such as toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, which induce a variety of proinflammatory cytokines to activate dendritic cells for efficient tumor antigen presentation to T-cells.4 As such, several TLR agonists are being used in the clinic as a single agent or in combination with checkpoint blockade agents such as aPD1.5

TLRs are pattern recognition receptors expressed on the surface or in the endosome of immune cells and are critical mediators of innate immunity. The immunostimulatory effect of TLR agonists has prompted the development of several small molecule TLR7 and TLR8 agonists for the treatment of cancers6,7 and TLR7 agonist imiquimod has been approved for the treatment of actinic keratosis and genital warts.8 In addition, the delivery of TLR agonists using antibody-drug conjugate technologies is currently being explored in the clinic.9−12 Among various TLR agonists, we have been particularly interested in developing TLR7 agonists because of their role in the production of type I interferon (IFN-α), which is regarded safer than proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α) primarily produced by the TLR8 pathway and can lead to cytokine release syndrome.13

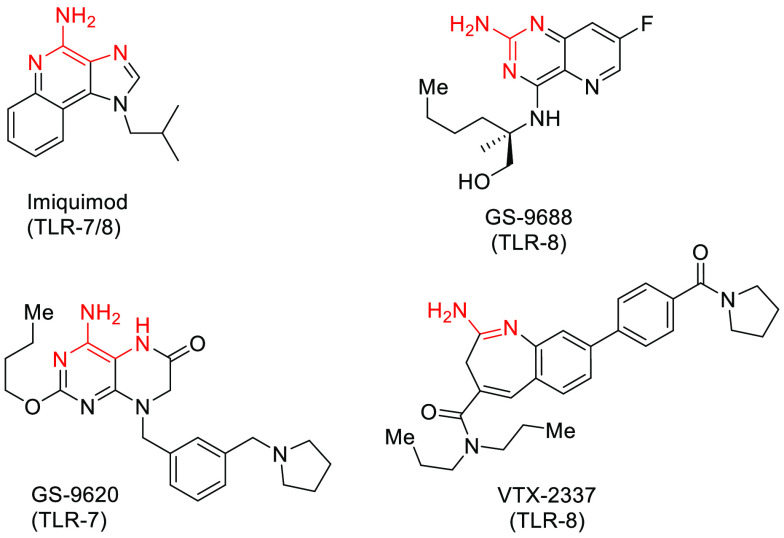

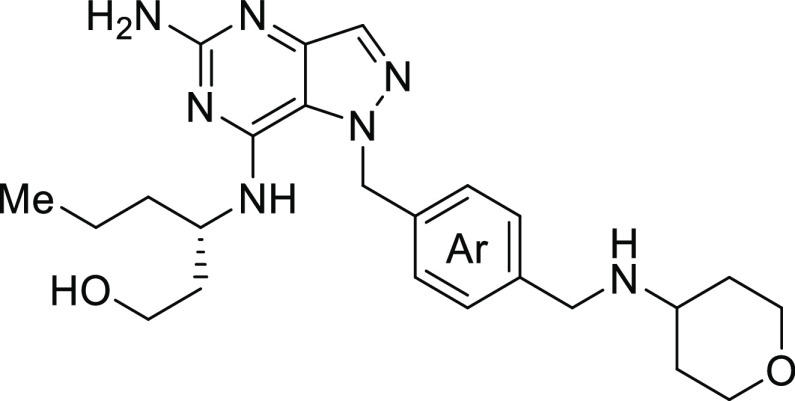

In this regard, we have developed a novel series of TLR7 agonists based on the pyrazolopyrimidine core.14 Based on the structures of several TLR7 and TLR8 agonists in the literature,15−17 we hypothesized that they all share a common minimum pharmacophore composed of a 2-aminopyridine or pyrimidine-based hydrogen bond donor–acceptor ring system, a hydrophobic aliphatic tail and a benzyl group at 120-degree orientation (Figure 1). In some cases, even a simpler system with a monocyclic aromatic core ring was shown to provide weak TLR7 activity (Figure 2, compound 1).18 We envisioned that the addition of a variety of aromatic groups as part of the bicyclic core would (1) provide more surface area for the core to interact with amino acid residues in the binding pocket19 and (2) reduce the free rotating conformers to allow for better fitting. As such, we introduced a series of five- membered heterocycles. Still most of them were inactive, including imidazole-pyrimidine 2 (Figure 2). Docking studies of compound 2 and other analogues with the TLR7 homology model showed that the pKa of the nitrogen atom at the 4-position is critical for TLR7 activity.19 Under the physiological acidic pH of the lysosome, N-4 must be protonated for a critical hydrogen bonding interaction with Asp555. In compounds like 2, the lower pKa of N-4 precludes its protonation, whereas for pyrazolo-pyrimidine 3, N-4 is protonated and forms interactions with Asp-555, which was later verified through the X-ray cocrystallization studies (vide infra). Encouraged by the micromolar potency of 3, we explored substitutions on the benzyl group. We identified that adding an ortho-methoxy group increased TLR7 potency by 4-fold to 384 nM (compound 4). While we did not initially understand the role of the methoxy group, structural studies later revealed that it forms an intramolecular hydrogen bond with N–H hydrogen at the 7-position (vide infra).

Figure 1.

Structures of clinical TLR agonist examples.

Figure 2.

Early core modification work.

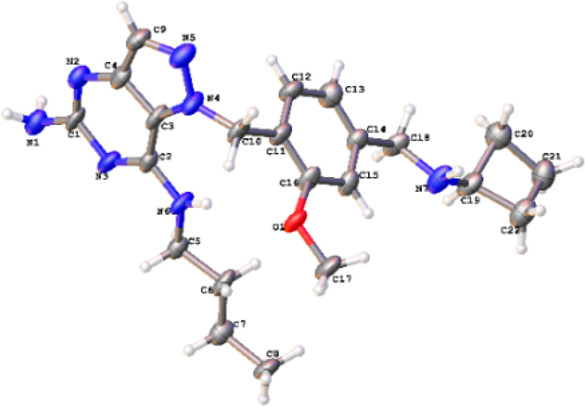

Since the TLR7 target is localized in the acidic environment of the endosome of immune cells, we believed that the presence of an amine would be beneficial for trapping the agonist in the lysosome for prolonged target engagement. A prototypical amine compound 5 was prepared by incorporating a cyclobutyl benzylamine developed previously in a separate series of agonists.20 As expected, this compound exhibited 6-fold higher potency in the human TLR7 reporter assay than 4. While the compound was 2-fold less potent in the mouse TLR7 reporter assay, it was completely selective for human TLR7 with no activation of TLR8 up to 5 μM. We obtained a single-crystal X-ray structure of compound 5 that showed the presence of an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the N–H at the C-7 position and the oxygen atom of the methoxy group (see Figure 3). This observation suggested the importance of the methoxy group in configuring the molecule’s overall orientation.

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal structure of compound 5.

In addition to being a potent TLR7 agonist, compound 5 possessed a reasonably safe profile including a low level of cytotoxicity toward T-cells as measured by PHA blast activity and micromolar CYP and hERG inhibition. However, the metabolic stability of compound 5 in human and mouse liver microsomes was low, and metabolite identification studies revealed significant oxidative metabolism, leading to the dealkylation of the cyclobutyl amine group. This poor metabolic stability may have resulted from the higher lipophilic nature of cyclobutyl amine group. Docking studies of compound 5 with published TLR7 structure showed that the pendant amine part of the molecule pointed toward the solvent-exposed region of the binding pocket and was amenable to further modification. As such, we replaced the cyclobutyl amine group with less lipophilic amines (Table 1), which led to some loss of TLR7 potency but showed increased metabolic stability. Interestingly, when the amine in compound 7 was replaced with the corresponding amide, a dramatic loss of potency was observed, highlighting the importance of the basic amine group for prolonged target engagement in the lysosomal compartment. Tertiary amines were equally as potent as secondary amines; however, there was no significant improvement in metabolic stability except for spirocyclic amine 13, which demonstrated excellent human and mouse metabolic stability but was much less potent, most likely due to the higher polarity and basicity of the spirocyclic amine group.21 Addition of another benzylamine group (compound 15) provided highly potent reporter activity at the cost of metabolic stability. While benzylamine SAR provided the types of amines tolerated in the solvent-exposed region, a general improvement in metabolic stability could not be achieved.

Table 1. Benzyl Amine Modifications.

Another metabolite identified from the metabolite identification studies on compound 5 was the oxidation of the n-butyl side chain. We next focused our SAR efforts on minimizing oxidation of the C-7 side chain (Table 2). Replacement of the n-butyl group with either 16 or N-methyl amine 17 completely abolished activity, which once again highlighted the necessity of the C-7 NH group for an intramolecular H-bond interaction. We hypothesized that oxidation of the n-butyl chain most likely occurs adjacent to the nitrogen atom at the 7 position, and we attempted to circumvent this by introducing a methyl group next to the N–H group. Although this modification led to a significant increase in potency, it did not improve metabolic stability. Replacement of the methyl group with hydroxymethyl in compound 19 led to a loss of activity but significantly improved metabolic stability in mouse liver microsomes. Next, we systematically explored different side chains appended to the α-carbon atom of C-7 substituents where we showed that a hydroxyethyl side chain (compound 20) provided balanced potency and metabolic stability. Shortening the side chain or replacement with isopropyl or cyclopropyl group significantly reduced potency but still maintained good metabolic stability. Interestingly, the replacement of the alcohol with acetamide (compound 25) was somewhat tolerated. While our primary goal during this SAR was to improve metabolic stability, we were also tracking some of the liabilities identified in 5, such as PHA blast, hERG, and CYP activities, which were eliminated upon using a hexanol C-7 side chain. By combining the SAR data focusing on the benzylamine and the C-7 side chain, we identified compound 20 to be that with the best potency and metabolic stability.

Table 2. Replacement of C7 Groups.

The CYP inhibition panel included eight isoforms and the most potent IC50 values are shown.

To further improve the metabolic stability of 20, we next focused on modifying the benzyl group to lower compound lipophilicity (Table 3). When the methoxy group was replaced with isosteric groups, such as in 26 and 27, potency was maintained without much improvement in metabolic stability. Interestingly, an intramolecular hydrogen bond was observed between C-7 N–H and nitrogen in the quinoline ring in compound 26 by NMR. Replacement of the methoxy group with hydrogen or fluorine led to a dramatic loss in potency, as expected, since these groups can not emulate the intramolecular hydrogen bonding interaction found in the X-ray crystal structure of compound 5. Pyridine analogue 30 was inactive in both TLR7 and TLR8, most likely due to lower permeability. The addition of the pyridine nitrogen on the methoxy series improved metabolic stability, but the activities of these compounds were quite variable, with 32 and 33 being inactive in mouse TLR7. Also, the activity seemed to depend on the position of nitrogen atom in the ring which is not fully understood. From the SAR work above, compound 20 displayed the best overall profile and was examined more extensively both in vitro and in vivo. While compound 20 showed potent activity in both human and mouse TLR7 reporter assay, it did not show any activities for TLR2, 3, 4, 8, and 9 up to five micromolar concentration. It also displayed potent activity in both human and mouse whole blood, as indicated by the secretion of cytokines and interferon-induced genes (Table 4). Compound 20 did not inhibit a panel of 221 kinases up to one micromolar concentration and displayed an IC50 of >30 μM for GPCRs, transporters and ion channels. Interestingly, this series of compounds exhibited low plasma protein binding with about 50% free fraction in human plasma. Compound 20 showed no CYP inhibition in a panel of eight CYP enzymes and was not cytotoxic toward cancer and immune cells. Physiochemically, compound 20 displayed decent permeability. In the hERG patch clamp assay, the compound 20 showed IC50 of 11 μM, which is considered safe given the potency of the compound and based on the maximum concentration of 20 at the efficacious dose (vide infra).

Table 3. Benzyl Group SAR.

Table 4. Detailed In Vitro Profiling of Compound 20.

| human EC50 (nM) | mouse EC50 (nM) | selectivity (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| TLR7 = 12 | TLR7 = 27 | hTLR2/3/4/8/9 > 5000 |

| TNF-α = 631 | TNF-α = 3.4 | Kinase panel >1000 |

| IP-10 = 0.13 | IP-10 = 0.32 | PXR > 50 |

| IFIT1 = 0.10 | IFIT1 = 0.19 | CT26 > 25000 |

| IFIT3 = 0.11 | IFIT3 = 0.13 | JURKAT > 25000 |

| MX1 = 0.09 | MX1 = 0.18 | THP1 > 25000 |

| protein binding | met. stability (t1/2 min) |

|---|---|

| (% free, H/M/C) = 50/41/31 | (H/M/C) = 43/85/16 |

| Caco (nM/s) | PAMPA (nM/s) |

|---|---|

| A-B/B-A = 14/109 | pH 5.5/7.4 = 9.5/15.8 |

A cocrystal structure of lead compound 20 with monkey TLR7 ectodomain showed that the small molecule sits in a dimeric interface making network of hydrogen bonding interactions (Figure 4). First, the pyrazolopyrimidine core and the benzyl side chain showed π–π interactions with Phe408 and Tyr356 respectively. The protonated nitrogen at the 4-position and the exocyclic amine at the 5-position make a bifurcated salt bridge with Asp555. This interaction of protonated N-4 nitrogen was predicted from our initial SAR, which suggested that it needed to be basic enough for protonation in the lysosomal pH. The n-butyl chain at C-7 position occupies a tight hydrophobic pocket, and as observed and a minor modification led to significant drop in potency. The hydroxyl group on the C-7 side chain makes a hydrogen bond interaction with Tyr264. As observed in the crystal structure of the small molecule alone, the cocrystal structure also showed the presence of an intramolecular hydrogen-bonding interaction between the C-7 N–H and methoxy group of the side chain, further validating the fact that removal of the methoxy group was not tolerated. Finally, the terminal amine on the benzylamine substituent is involved in another salt bridge with Gln354. This supports the observation that removing basic amine led to a loss of potency as observed in compound 8.

Figure 4.

X-ray cocrystal of compound 20 with monkey TLR7.

The synthetic route for compound 20 is outlined in Scheme 1. Amination of commercially available 34 using Boc-hydrazine followed by deprotection provided compound 36, which was condensed with 1-(dimethyl-amino)-2-nitro ethylene to provide substituted pyrazole 37 as a single isomer.22 The nitro group was reduced, and the resulting amine 38 was condensed with bismethyl carbamate thiourea, furnishing the pyrazolo-pyrimidine core with pendant benzyl ester 39. This compound served as a common intermediate for modifications at both C-7 and the benzylamine positions for the generation of compounds in Tables 1 and 2. The phenol 39 was coupled with amine 40 to install the C-7 side chain. Reduction of ester 41 to alcohol 42 followed by its conversion corresponding to benzyl chloride and displacement with the appropirate amine provided protected analogues. Finally deprotection of carbamate and TBDPS groups revealed compound 20. An analogue synthetic route was used to generate compounds that differ in the benzyl group in Table 3.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Route for Compound 20.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Boc-NHNH2, DIPEA, DMF (38%); (b) HCl-dioxane (84%); (c) (E)-N,N-dimethyl-2-nitroethen-1-amine, pyridine, DCM, ethyl 2-chloro-2-oxoacetate then 36 (70%); (d) Zn, NH4CO2, THF (98%); (e) 1,3-Bis(methoxycarbonyl)-2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea, AcOH, NaOH (80%); (f) BOP, DBU, dmso, 80 °C (64%) (g) LiBH4, MeOH, 0 °C, (82%); (i-1) SOCl2, THF; (ii-2) tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-amine, DMF, 80 °C; (i-3) Et3N.3HF; (i-4) NaOH, dioxane, 80 °C; (68% over 4 steps).

Based on the favorable potency, functional activity, ADME properties, and selectivity over other TLRs, compound 20 was advanced to PK/PD studies where it showed clearance higher than hepatic blood flow, which was considered favorable for a highly potent TLR7 agonist to mitigate potential cytokine release syndrome (Table 5). Pharmacodynamic studies (PD) in Balb-C female mice showed the elevation of several relevant cytokines, including IFNα (Figure 5). A dose dependent PD was observed at 0.15 and 0.5 mg/kg. However, a higher dose (2.5 mg/kg) did not led to corresponding induction of IFNα. This phenomenon is described as the hook effect and is characteristic of TLR agonists, which at higher concentrations lead to saturation of the target, resulting in lower PD.23 In an efficacy study in a CT-26 tumor model using the IV route, a weekly dose (QWx4) of 20 for 4 weeks in combination with aPD1 (IP route, Q4Dx7) displayed dose-dependent antitumor activity and led to 8 out of 10 mice being tumor-free at the 2.5 mg/kg dose level (Figure 6). On the other hand, lower doses of 20 and aPD1 alone were much less efficacious highlighting the potential of combining TLR7 agonists with checkpoint blockade inhibitors for cancer immunotherapy. For all the in vivo studies, a known TLR7 agonist gardiquimod (GDQ) (hTLR7 EC50 = 4 μM) was used as positive control, which has been thoroughly characterized in the literature.24

Table 5. PK Gardiquimod and Compound 20 in Female Balb/C Mice.

| PK parameters | GDQ | Compound 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg/kg) | 7.5 | 0.15 | 0.5 |

| C5 min (nM) | 4678 | 85 | 139 |

| AUC last (nM*h) | 9944 | 75 | 183 |

| Clearance (mL/min/kg) | NA | NA | 160 |

Figure 5.

PD of gardiquimod and compound 20 in female Balb/C mice.

Figure 6.

Efficacy of compound 20 in combination with aPD1.

In summary, we have developed a novel series of TLR7-selective agonists based on a pyrazolopyrimidine core. Starting from a suboptimal chemotype that lacked desired potency and possessed several liabilities surrounding metabolic stability and hERG and CYP inhibition, we were able to improve potency and address liabilities and physicochemical properties. In addition, the lead TLR7 agonist displayed favorable PK and PD in a mouse model. Finally, robust in vivo antitumor activity was observed in combination with aPD1 in a CT-26 tumor model, providing confidence in this particular chemotype. Further efforts to improve metabolic stability led to the discovery of new series of potent TLR7 agonists, which will be disclosed in the succeeding paper.25

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DIPEA

diisopropyl amine

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- TEA

triethylamine

- DCM

dichloromethane

- GDQ

gardiquimod

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00455.

Full experimental details for key compounds, biological assay protocols, and crystallography details (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Mellman I.; Coukos G.; Dranoff G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 2011, 480, 480–489. 10.1038/nature10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas A.; Wolchok J. D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 2018, 359, 1350–1355. 10.1126/science.aar4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Huang D.; Saw P. E.; Song E. Turning cold tumors hot: from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. Trends Immunol. 2022, 43, 523–545. 10.1016/j.it.2022.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O.; Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010, 140, 805–820. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczanowska S.; Joseph A. M.; Davila E. TLR agonists: our best frenemy in cancer immunotherapy. J. Leukoc Biol. 2013, 93, 847–863. 10.1189/jlb.1012501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Zhang J.; Wang J.; Hu X.; Ouyang L.; Wang Y. Small-Molecule Modulators Targeting Toll-like Receptors for Potential Anticancer Therapeutics. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 6437. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frega G.; Wu Q.; Le Naour J.; Vacchelli E.; Galluzzi L.; Kroemer G.; Kepp O. Trial Watch: experimental TLR7/TLR8 agonists for oncological indications. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9, 1–10. 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1796002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. L.; Gerster J. F.; Owens M. L.; Slade H. B.; Tomai M. A. Imiquimod applied topically: a novel immune response modifier and new class of drug. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1999, 21, 1–14. 10.1016/S0192-0561(98)00068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L.; Wang L.; Wang Z.; Li T.; Chen H.; Zhang Y.; Hu Z.; Dimitrov D. S.; Du J.; Liao X. Immune Modulating Antibody–Drug Conjugate (IM-ADC) for Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 15716–15726. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman S. E.; Pearson C. I.; Gregorio J. D.; Gonzalez J. C.; Kenkel J. A.; Hartmann F. J.; Luo A.; Ho P. Y.; LeBlanc H.; Blum L. K.; Kimmey S. C.; Luo A.; Nguyen M. L.; Paik J. C.; Sheu L. Y.; Ackerman B.; Lee A.; Li H.; Melrose J.; Laura R. P.; Ramani V. C.; Henning K. A.; Jackson D. Y.; Safina B. S.; Yonehiro G.; Devens B. H.; Carmi Y.; Chapin S. J.; Bendall S. C.; Kowanetz M.; Dornan D.; Engleman E. G.; Alonso M. N. Immune-stimulating antibody conjugates elicit robust myeloid activation and durable antitumor immunity. Nat. Cancer 2021, 2, 28–33. 10.1038/s43018-020-00136-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S.; Brems B. M.; Olawode E. O.; Miller J. T.; Brooks T. A.; Tumey L. N. Design and Characterization of Immune-Stimulating Imidazo[4,5-c]quinoline Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2022, 19, 3228–3241. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.2c00392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janku F.; Han S.-W.; Doi T.; Amatu A.; Ajani J. A.; Kuboki Y.; Cortez A.; Cellitti S. E.; Mahling P. C.; Subramanian K.; Schoenfeld H. A.; Choi S. M.; Iaconis L. A.; Lee L. H.; Pelletier M. R.; Dranoff G.; Askoxylakis V.; Siena S. Preclinical Characterization and Phase I Study of an Anti–HER2-TLR7 Immune-Stimulator Antibody Conjugate in Patients with HER2+ Malignancies. Cancer Immunol Res. 2022, 10, 1441–1461. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-21-0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender A. T.; Tzvetkov E.; Pereira A.; Wu Y.; Kasar S.; Przetak M. M.; Vlach J.; Niewold T. B.; Jensen M. A.; Okitsu S. L. TLR7 and TLR8 Differentially Activate the IRF and NF-κB Pathways in Specific Cell Types to Promote Inflammation. Immunohorizons 2020, 4, 93–107. 10.4049/immunohorizons.2000002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel Y. B.; Gangwar S.; He L.; Sivaprakasam P.; Broekema M.; Cox M.; Tragy C. M.; Zhang Q.. 1H-pyrazolo[4,3-d]pyrimidine compounds as toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) agonists and methods and uses therefor US2020/0038403A1, Feb 6, 2020.

- Roethle P. A.; McFadden R. M.; Yang H.; Hrvatin P.; Hui H.; Graupe M.; Gallagher B.; Chao J.; Hesselgesser J.; Duatschek P.; Zheng J.; Lu B.; Tumas D. B.; Perry J.; Halcomb R. L. Identification and Optimization of Pteridinone Toll-like Receptor 7 (TLR7) Agonists for the Oral Treatment of Viral Hepatitis. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 7324–7333. 10.1021/jm400815m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackman R. L.; Mish M.; Chin G.; Perry J. K.; Appleby T.; Aktoudianakis V.; Metobo S.; Pyun P.; Niu C.; Daffis S.; Yu H.; Zheng J.; Villasenor A. G.; Zablocki J.; Chamberlain J.; Jin H.; Lee G.; Suekawa-Pirrone K.; Santos R.; Delaney W. E. I. V.; Fletcher S. P. Discovery of GS-9688 (Selgantolimod) as a Potent and Selective Oral Toll-Like Receptor 8 Agonist for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 10188–10203. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H.; Dietsch G. N.; Matthews M. A.; Yang Y.; Ghanekar S.; Inokuma M.; Suni M.; Maino V. C.; Henderson K. E.; Howbert J. J.; Disis M. L.; Hershberg R. M. VTX-2337 is a novel TLR8 activates NK cells and augments ADCC. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 499–509. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan D. C.; Herschke F.; Pauwels F.; Stoops B.; Last S.; Pieters S.; Scholliers A.; Thoné T.; Van Schoubroeck B.; De Pooter D.; Mostmans W.; Khamlichi M. D.; Embrechts W.; Dhuyvetter D.; Smyej I.; Arnoult E.; Demin S.; Borghys H.; Fanning F.; Vlach J.; Raboisson P. Novel pyrimidine toll-like receptor 7 and 8 dual agonists to treat hepatitis B virus. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 7936–7949. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Ohto U.; Shibata T.; Krayukhina E.; Taoka M.; Yamauchi Y.; Tanji H.; Isobe T.; Uchiyama S.; Miyake K.; Shimizu T. Structural Analysis Reveals that Toll-like Receptor 7 Is a Dual Receptor for Guanosine and Single-Stranded RNA. Immunity 2016, 45, 737–748. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel Y. B.; He L.; Gangwar S.; Posy S. L.; Sivaprakasam P.. Preparation of 6-amino-7, 9-dihydro-8H-purin-8-one derivatives as immunostimulant Toll-like receptor 7 agonists WO2019/035968Al, Feb 21, 2019.

- Degorce S. L.; Bodnarchuk M. S.; Scott J. S. Lowering Lipophilicity by Adding Carbon: AzaSpiroHeptanes, a LogD Lowering Twist. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 1198–1204. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R.; Hong Z.; Wang B.; Kempson J.; Cornelius L.; Li J.; Li Y. X.; Mathur A. Regioselective synthesis of N1-substituted-4-nitropyrazole-5-carboxylates via the cyclocondensation of ethyl 4-(dimethylamino)-3-nitro-2-oxobut-3-enoate with substituted hydrazines. Org. Biomol Chem. 2022, 20, 9746–9752. 10.1039/D2OB02006H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins S. R.; Vasilakos J. P.; Deschler K.; Grigsby I.; Gillis P.; John J.; Elder M. J.; Swales J.; Timosenko E.; Cooper Z.; et al. Intratumoral immunotherapy with TLR7/8 agonist MEDI9197 modulates the tumor microenvironment leading to enhanced activity when combined with other immunotherapies. J. Immunother Cancer. 2019, 7, 244. 10.1186/s40425-019-0724-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F.; Zhang J.; Zhang J.; Zhang C. The TLR7 agonists imiquimod and gardiquimod improve DC-based immunotherapy for melanoma in mice. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2010, 7, 381–388. 10.1038/cmi.2010.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L.; Zhang M. Y.; Cox M.; Zhang Q.; Donnell A. F.; Zhang Y.; Tarby C. M.; Gill P.; Subbiah M. A. M.; Ramar T.; Reddy M.; Puttapaka V. K.; Li Y. X.; Sivaprakasam P.; Critton D.; Mulligan D.; Xie C.; Ramakrishnan R.; Nagar J.; Dudhgaonkar S.; Murtaza S.; Oderinde M. S.; Schieven G. L.; Mathur A.; Gavai A. V.; Vite G. D.; Gangwar S.; Poudel Y. B.. Identification and optimization of small molecule TLR7 agonists for applications in immuno-oncology. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.