Abstract

Objectives:

The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated increases in alcohol use and ushered in virtually-delivered healthcare, creating an opportunity to examine the impacts of telehealth on alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment. To understand these impacts, we explored perspectives on telehealth-delivered psychotherapy among individuals with AUD.

Methods:

This was a qualitative study using semi-structured interviews. Participants (N=31) were patients with AUD who had received telehealth-delivered AUD psychotherapy in the last two years (N=11) or had never experienced AUD psychotherapy (N=20), recruited from two large academically-affiliated healthcare systems in Michigan between July and August 2020. Participants were asked about perceived barriers and facilitators to AUD psychotherapy, benefits and drawbacks of telehealth-delivered AUD psychotherapy, and changes needed to improve psychotherapy delivery. Interviews were transcribed, coded, and analyzed iteratively using thematic analysis.

Results:

Participants identified factors relating to perceptions of and experience with telehealth-delivered AUD psychotherapy. Findings reflected four major themes: treatment accessibility, treatment flexibility, treatment engagement, and stigma. Perceptions about telehealth’s impact on treatment accessibility varied widely and included benefits (e.g., eliminating transportation challenges) and barriers (e.g., technology costs). Treatment flexibility and treatment engagement factors included the ability to use phone and video and perceptions of receiving care via telehealth, respectively. Telehealth impacts on treatment stigma was also a key theme.

Conclusions:

Overall, perceptions of telehealth treatment for AUD varied. Participants expressed the importance of options, flexibility, and collaborating on decisions with providers to determine treatment modality. Future research should explore who benefits most from telehealth and avenues to enhance implementation.

Keywords: telehealth, alcohol use disorder, COVID-19, qualitative

Introduction

Alcohol use is the third leading cause of preventable death in the United States (US), contributing to 140,000 alcohol-related deaths yearly.1,2 Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a highly prevalent chronic illness, characterized by impaired ability to cut down or stop using alcohol despite consequences,3 with a lifetime prevalence of ~1 in 4 US adults.4 Evidence-based psychotherapy treatments are supported by decades of studies showing efficacy for engaging patients and treating AUD.5,6 However, fewer than 10% of people with AUD receive treatment.7

In response to stressors related to the COVID-19 pandemic, alcohol consumption, risky alcohol use, incidences of AUD and AUD-related consequences increased among US adults.8-10.11 The pandemic also impacted healthcare delivery and produced innovations in virtually-delivered care, including increased telehealth.12 Telehealth includes phone and/or video visits.13-15 Multiple reviews, primarily focused on video-based visits, have examined the efficacy of real-time telehealth-delivered interventions for mental health and have conclusively shown that telehealth is no less effective for mental health than in-person options.16,17 Fewer studies have examined telehealth for AUD, though systematic reviews suggested that telehealth-delivered AUD treatment can potentially reduce alcohol use and improve mood and functioning.18,19

No prior qualitative studies have examined perceptions of telehealth with a focus on patients with AUD, including their interest in telehealth, how telehealth might address barriers to AUD care, and challenges with engagement or receipt of telehealth care. Further, considering the large treatment gap, little is known about how patients with untreated AUD, who constitute the majority of the AUD population, perceive how telehealth would affect their ability to receive care.

Understanding perceptions of telehealth-delivered AUD psychotherapy in a patient population receiving and not receiving AUD treatment can inform treatment engagement strategies and improve AUD care. Thus, we conducted semi-structure qualitative interviews, using an interview guide informed by the Andersen Aday Model of Health Utilization,20,21 which was developed to characterize access to and utilization of medical care.22 We explored patient perspectives on telehealth-delivered AUD treatment in real-world settings and to identify facilitators, barriers, and areas for improvement.

Methods

Between July and August 2020, we recruited adult participants from the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System (AAVA) and from Michigan Medicine (MM), both large academically-affiliated healthcare systems in Southeast Michigan. We used purposeful sampling to recruit participants with and without telehealth AUD psychotherapy experience to better understand perceptions of barriers and facilitators to initiating and engaging in telehealth AUD treatment across both groups. Herein, telehealth-delivered psychotherapy refers specifically to psychotherapy for AUD completed via phone or video and will be referred to as teletherapy, care, and treatment throughout the manuscript. We focused on psychotherapy because it is the most commonly used evidence-based treatment for AUD.23,24

To identify potential participants, we obtained electronic health record (EHR) data from both VA and MM for adult primary care patients with ICD codes indicating AUD (i.e., F10.1, F10.2, and F10.9). Second, we reviewed the EHR for these patients to confirm study inclusion and exclusion criteria. Specific inclusion criteria confirmed via EHR review were: 1) age 18 or older; 2) past-year outpatient or inpatient encounter (July 2019- June 2020) with diagnosis of AUD identified via ICD codes (above); 3) past-year receipt of telehealth AUD psychotherapy (July 2019- June 2020) OR no prior telehealth-delivered AUD psychotherapy (confirmed via clinic notes). Exclusion criteria were past 3-month psychiatric hospitalization and history of cognitive impairment.

The AAVA and MM Institutional Review Boards approved this study and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to interview. Informed by the Andersen Aday Behavioral Model of Health Utilization, which assesses predisposing, enabling, and need factors to measure treatment access 21,22 ,we developed semi-structured qualitative interview guides to explore patient perspectives on telehealth AUD treatment. We queried predisposing (e.g., demographics, social factors, attitudes towards AUD treatment), enabling (e.g., distance to treatment, preferences about where to receive treatment) and need factors (e.g., perceived need for treatment, limited community treatment availability). This framework guided questions on perceptions of current barriers to treatment and perceptions of telehealth as means of reducing barriers and helping patients stay in treatment. While experience with telehealth varied, we specifically inquired about how participants would feel about receiving AUD psychotherapy via telehealth.

To describe the sample, we measured severity of past-year alcohol consumption via an interviewer-administered Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C).20,25 Demographic information was collected, including self-reported age, sex, race, and ethnicity. The interview team was composed of two females who identified as White. Interviews were conducted one-on-one via phone, lasted approximately 30-40 minutes, were audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Participants received a $25 gift card as compensation.

Analysis

The qualitative data analysis team included a qualitative methodologist (JF), research staff (RG, EP), and the PI (LL). We used a rapid analysis approach concurrent with ongoing interviews to iteratively inform subsequent data collection and analysis.26,27 We used a summary template including domains informed by the Andersen and Aday Model. Qualitative team members (RG, AL, & EP) read early interview transcripts and independently created summaries of each transcript. Next, we assessed the usability of the summary template, using consensus to further refine domains, definitions, and summary procedures. Once consistency was established, we divided the interview transcripts across team members and completed the summaries, meeting regularly to refine domain definitions and discuss insights gained. We created a cross-case descriptive matrix to assess patterns and facilitate theme development. Then, using themes from the rapid analysis, members of the research team created a codebook and refined codes and definitions through independently coding and discussing transcripts. The team regularly met to discuss and establish consensus for discrepancies in coding. Once coding consensus was reached, a code report was created using NVivo software 28. The team developed findings through review and discussion of the code reports. Transcripts were double-coded and discrepancies were further discussed and resolved.

Results

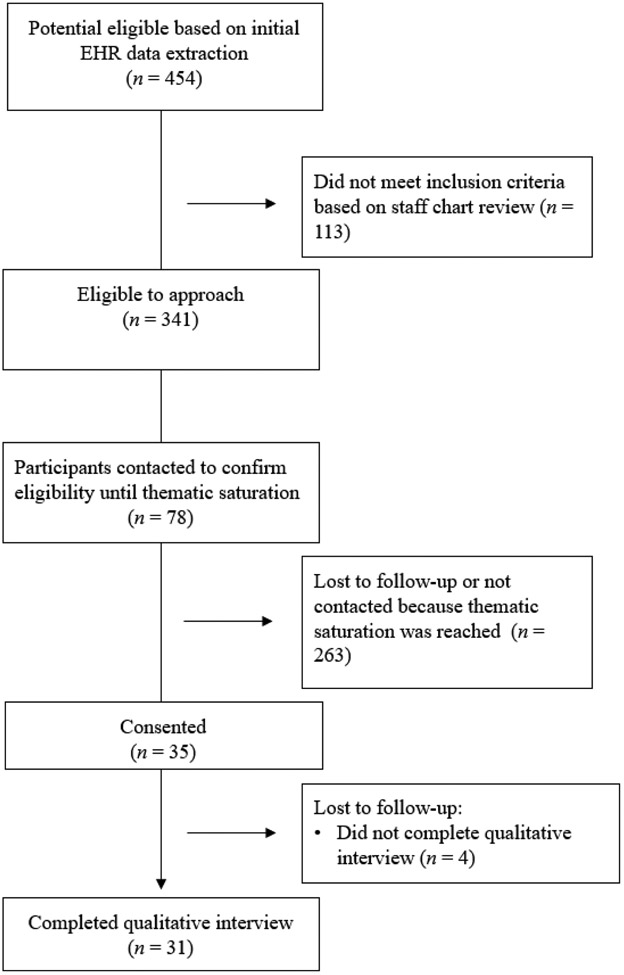

Based on ICD codes used to generate a list of potentially eligible patients, research staff reviewed N=454 patients’ EHRs. Of those, N=113 patients were ineligible to be contacted for study recruitment. We attempted to contact those eligible to approach and made contact with 78 individuals. Among those, we confirmed eligibility and consented 35 participants via telephone to complete a qualitative interview. We completed 31 interviews (N=4 did not respond after multiple contact attempts were made to complete the interview; N = 28 Veterans, N = 3 civilians). Of those interviewed, N=11 had experience with telehealth-delivered AUD treatment, and N=20 did not. See Figure 1 for a flowchart detailing recruitment.

Figure 1.

Screening and Recruitment Flow Chart

Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. The average AUDIT-C score was 9.97, indicating that, on average, the sample’s drinking fell in the “severe” range. Four key themes emerged, which are described below and in Table 2: treatment engagement, stigma, treatment accessibility, and treatment flexibility.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| N=31 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean | 49 | |

| Range | (28-76) | |

| Female (sex) | 6 | 19% |

| Male (sex) | 25 | 81% |

| Race | ||

| White | 25 | 81% |

| Black | 3 | 10% |

| Other | 1 | 3% |

| Unknown | 2 | 6% |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 2 | 6% |

| Veterans | 28 | 90% |

| Civilians | 3 | 10% |

| Telehealth Experience | ||

| Telehealth-experienced | 11 | 35% |

| Not telehealth-experienced | 20 | 65% |

| AUDIT-C Scores | ||

| Mean | 9.97 | |

| Range | (2-12) |

Table 2.

Summary of Themes and Subthemes from Patient Qualitative Interviews

| Themes | Subthemes | Patient Quotes (N= 31) |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment Engagement | “No excuse” to miss treatment |

“It created a zero, kind of a zero-tolerance mindset for me because now I have the avenue to be able to get everything done, make my meetings on time, you know that sort of thing and so that’s crucial when, you know when you’re in these programs with the court, that you know all the other mandates that are put in place almost seem like they’re, you know non-achievable.” (Telehealth-experienced)

“I do the Zoom thing…I enjoy that better than having to go to the buildings, like you know the whole logistics of getting there after work or something like that is just a nightmare and it, you know and now I don’t have an excuse why I don’t show up for them, right?” (Telehealth-experienced) |

| Telehealth “doesn’t feel the same” |

If I need to see somebody, I want live…I do not want it on camera, I do not want it on the phone, I want to talk to a human being face to face…that’s just me, I’m old-fashioned.” (Not telehealth-experienced)

“You know you take away a lot of being able to communicate with somebody when you aren’t face-to-face with them…you know regardless if you can see their face on that screen or not, you're not there with them and there’s nothing you're going to ever be able to do to replace that, ever, you know, it's just never, it'll never be the same.” (Not telehealth-experienced) |

|

| Psychological need to physically go to in-person treatment |

Reflect on therapy session: “After the meetings were over, you know, I had an hour-long drive home and just, you know more time to sit and dwell and think on it. Not really dwell, I shouldn’t say dwell but more time to think about what we had discussed and that’s what I always liked about it.” (Not telehealth-experienced)

Fulfill in-person social needs: “You know you actually were interacting with somebody you know and that’s what liked best about [in-person treatment].” (Not telehealth-experienced) |

|

| Adhere to treatment goals | ““I see [in-person treatment] as myself getting more involved, taking myself out of the current situation, putting myself in a better situation, because I’m not totally reliable…because I’m weak at times and make bad decisions” (Not telehealth-experienced). | |

| Stigma | Telehealth reduces stigma | “You probably want to let your people at work know that you know you’re going through a treatment or whatever, but it’s not like, “Okay Boss, remember I told you …” you know what I'm saying, because I can just grab my phone and so that, that saved face with me because you know I’m only a year into this job.” (Telehealth-experienced) |

| Phone delivery reduces stigma | “I would say that it would be the phone in some ways I feel better, it makes it easier. The actual non-contact is easier, not because of Covid, but just because it makes it easier to talk to somebody, because you can’t see if they’re judging you or not” (Telehealth-experienced) | |

| Treatment Accessibility | Overcomes transportation challenges |

“I don't even have a vehicle anymore, so it starts becoming a burden on my elderly father so who gets treatment all the time and stuff for different various things and stuff. So, it's very limited…I have to make sure my schedule or his schedule is open before I can do anything.”(10-not telehealth-experienced)

“I wouldn’t have to miss it. I mean sometimes I can’t get to an appointment, the transportation that they offer… the communication is all messed up” (Not telehealth-experienced) |

| Access to private space | “I think I still prefer to go in-person just because if I'm at home, my family’s there you know I don’t necessarily want them to hear everything I’m saying either.”(Not telehealth-experienced) | |

| Affordability of and access to technology | “You know I don't have a lot of money so sometimes the phone, I do the monthly minute thing you know so there were times when I was worried, I would just have enough minutes to cover the session, so I think that may be something that therapy you might want to take into account is they may not have minutes on their phone to have an hour-long session” (Telehealth-experienced) | |

| Access to reliable internet or cell reception | “When I first started telehealth we lived in the city, we didn’t realize what a wasteland it was out here, so it's been a challenge doing the videos…we don't have internet here and I don’t have very good cell reception either” (Telehealth-experienced) | |

| Technology literacy |

“A lot of this stuff is kind of convoluted, or just like holy cow, I have to be a rocket scientist.” (Not telehealth-experienced)

“I’ve never done it. I'm not real tech savvy…you know I don’t even own a computer.” (Not telehealth-experienced) |

|

| Treatment Flexibility | Convenience |

“I don’t have to leave my house, it’s convenient. I can get up, flip open a laptop or look at my phone or whatever the case may be and boom, I’ve got it going.” (Telehealth-experienced)

“It’s made it easier for me to stay in treatment because I’m a little bit more available than I would be if I was in the office.” (Telehealth-experienced) |

| Flexibility in telehealth modality |

“I can do it with my phone, I can do it with laptop, I can do it with the tablet, I can do it with anything.”(Telehealth-experienced)

“I was actually surprised how easy and simple and good it was through the phone too.”(Not telehealth-experienced) |

Theme 1: Treatment Engagement

We defined treatment engagement as factors relating to the likelihood that the patient would stay in treatment, particularly emotions and attitudes about treatment modality (i.e., phone, video, or in-person visits). Participants explained that the ease and convenience of telehealth gave them “no excuse” to miss treatment. One participant stated, “So it takes that excuse away, like, ‘Well I just don’t feel like driving,’ now you know, I can just turn the laptop on and login to one of the scheduled meetings and there you are on Zoom” (Telehealth-experienced).

In contrast, some participants believed therapy was something they needed to do in- person, for various reasons. First, talking to a therapist over the phone or video “didn’t feel the same” (Telehealth-experienced). One participant shared, “I’m old-fashioned, I need to see my doctor…It’s not my generation. I like to be with my doctor in a room” (Not telehealth-experienced). Another participant specified: “It’d be nice to be able to see someone in- person, I can gauge their comfortability so I could know how comfortable I am. It’s just a lot more that you can get done with human interaction” (Telehealth-experienced).

Second, several participants reported that physically going to in-person appointments was important for their mental health. One participant said that in-person visits were a more active way of engaging in treatment, which they deemed beneficial: “You go in the building, you see the counselor, you get your appointment…you’re engaged in something that you’re trying to make changes in your life…and maybe getting a phone call and sitting around in your pajamas doesn’t have the same mental impact, you know” (Telehealth-experienced). Other participants said leaving their house for treatment gave them time to themselves and away from their family: “I need to go somewhere where I’m just going to be by myself for a while and not see anybody, I have family, I have kids” (Not telehealth-experienced). For other participants, time spent commuting from treatment let them productively reflect on therapy sessions: “It gives you that extra hour or whatnot, whatever timeframe it is, to really let everything sink into what you guys had discussed” (Not telehealth-experienced). Going to treatment in-person gave participants who found it psychologically difficult to leave their home an opportunity to do so. One participant said having a routine that involved going to treatment made it easier to engage: “It was part of my routine, shall I say, to get up, get ready to go to my appointments. That initial change was difficult for me, I do better with a routine…and I don’t go out of the house very often, you know just for like groceries and stuff” (Telehealth-experienced). For some, going to in-person treatment helped fulfill social needs: “It was another way to get out of the house and be around people" (Telehealth-experienced).

A few participants shared that in-person treatment helped them accurately share about their alcohol use with their provider. For example, some felt that seeing a provider over a video or phone made it more likely that they would under-report their substance use. “But it’s harder…for me just to say I'm going to stay at home and then lie to somebody on the phone and say, ‘Yeah, I'm doing all this stuff,’ and when I’m really not” (Not telehealth-experienced). On adhering to treatment goals, a participant shared: “I’m not sure if I would necessarily have the self-control to not use while using telehealth. That’s why I always picked the most intensive therapy I can get” (Not telehealth-experienced).

Theme 2: Treatment stigma

We defined stigma as factors relating to perceived negative judgment of receiving AUD treatment. Some individuals reported that receiving treatment through telehealth reduced feelings of stigma related to AUD care, for example, via reducing opportunities to feel judged in the clinic waiting room by staff or other patients, or in the workplace when asking to take time off for an appointment. For example, one participant shared, “Just the fact that you don't have to like go into an office check-in and be in a waiting room with other people, you know so I guess there's like less anxiety involved in the process” (Telehealth-experienced).

Theme 3: Treatment Accessibility

The next theme focused on factors that affected participants’ ability to access AUD treatment. Telehealth helped some participants overcome transportation challenges involved in seeking care, including lack of access to a vehicle, needing others to provide transportation, commuting time, and financial costs of transportation. One participant shared: “You know a lot of people with a drinking problem, they ain’t exactly a person of means, so you know if I can, you know I might not have transportation that day…a phone call is much easier to schedule than a trip to an office and coming home” (Telehealth-experienced).

In contrast, participants also shared barriers to accessing teletherapy. Several participants who attended telehealth appointments from home described concerns regarding lack of private space with minimal distractions. For example, some participants who lived with family expressed discomfort with the potential that partners or children could overhear them discussing sensitive topics, including substance use. One participant stated: “The only barrier against [telehealth] is to make it the time when I have the house to myself” (Not telehealth-experienced). On distractions, one participant shared, “When I was going to see [my therapist] personally, there was no other distractions…you know the TV wasn’t on or the radio wasn’t on or…somebody talking about ‘What do you want for dinner?’, that kind of stuff” (Not telehealth-experienced).

Some participants described accessibility barriers related to technology. For example, several reported not being able to afford home internet or a mobile data plan that would allow them to access treatment remotely. Further, participants reported difficulty accessing the hardware needed to engage in a video visit; one participant shared, “I’d have to go to like a local library, I still have a flip phone” (Not telehealth-experienced) and another shared “I don’t have a computer, I don’t have internet, I just have my little flip top” (Not telehealth-experienced).

Lack of reliable internet or cell reception was also a barrier to accessing telehealth-delivered treatment. A few participants who lived in rural areas reported experiencing low-quality connections that would make it difficult to hear and/or see a therapist. One participant shared how these connectivity issues affected the therapeutic relationship, stating, “I think [telehealth] has impacted me negatively, that’s just me though, a lot of times I can barely hear my phone,” (Telehealth-experienced) and then specifically sharing, “The connectivity we have, there’s like a gap in what she hears me say…so it’s hard for me to stay on track with that, because I’ll be moving on to something else and she still hasn’t heard what I said thirty seconds ago, so it’s kind of fragmented.”

Lastly, across both groups, several participants reported potential low technology literacy. Specifically, some indicated that the instructions provided for telehealth were confusing because they did not have much experience with technology, and consequently because of their limited experience, following instructions seemed more complicated.

Theme 4: Treatment Flexibility

We defined flexibility as factors that allowed for telehealth treatment to meet the needs of the participant. For example, some participants reported that telehealth was more convenient because it provided flexibility in time and place of treatment (Table 2) and helped them maintain work and childcare responsibilities. One participant shared, “It didn’t put any strain, any constraints on the work and freeing up my time to get to anything because I could just look and turn my phone on and boom” (Telehealth-experienced). Another participant, who was receiving court-mandated treatment, said, “It allowed me to stay in compliance with all the other things that the court’s mandating me to get done” (Telehealth-experienced).

Flexibility in modality of telehealth-delivered care (e.g., video, phone) also allowed for greater ability to attend sessions. For example, participants shared how easy it was to sit in their car during their lunch break and use their phone to attend sessions, without needing to worry about access to internet or a strong data connection needed for a video session.

Telehealth-experienced vs. not telehealth-experienced

Although comparing the two groups (telehealth-experienced vs. not telehealth-experienced) was not the primary goal of the research, differences were sometimes noted in comfort level with telehealth based on history of telehealth receipt. Namely, participants who were already receiving telehealth-delivered AUD treatment were generally more open to using telehealth than participants who had never received AUD teletherapy.

Discussion

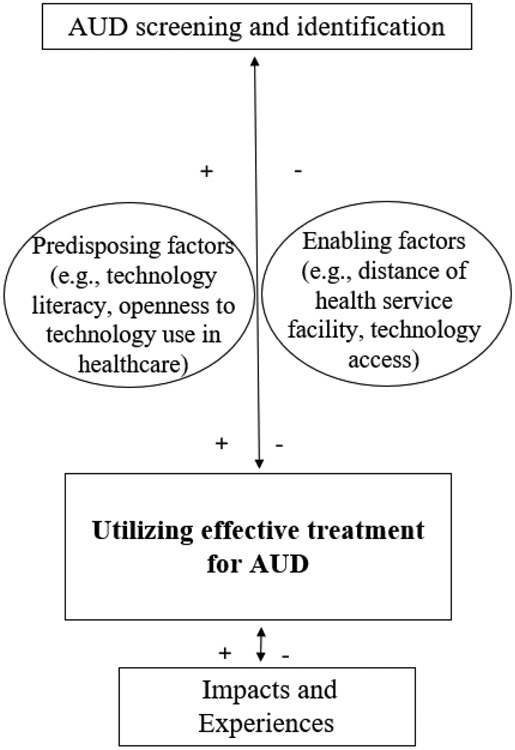

We found that participants’ perceptions of telehealth varied and reflected four key themes: treatment engagement, stigma, treatment accessibility, and treatment flexibility. Some of the identified subthemes (e.g., convenience, versatility, and eliminating transportation barriers) could be generalized to patients’ telehealth experiences across service delivery areas, but factors like stigma may be more unique to substance use treatment. Our conceptual model, adapted from Andersen Aday,21 guided our conceptualization of how dynamic factors may influence utilization of telehealth delivered psychotherapy for AUD (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual Model for Utilization of Telehealth Delivered Psychotherapy for AUD

+ indicates increasing likelihood, − indicates decreasing likelihood

For some, telehealth functioned as a facilitator to care by reducing barriers like stigma and transportation. These findings were consistent with prior studies in other substance use disorder (SUD) samples18 and general mental health treatment,29,30 which found that stigma may be reduced in participants accessing treatment via telehealth,, though this is under-studied in patients with AUD.31 Further work is needed to understand how telehealth might resolve stigma for patients with AUD. For example, for some, telehealth may serve as an alternative to traditional treatment models by potentially relieving the stigma associated with having to present in person at a treatment clinic waiting room32,33.

Participants also reported that telehealth reduced transportation challenges, primarily by decreasing costs and eliminating commute time. Considering disparities in AUD treatment access, particularly among historically marginalized and excluded groups, and for reasons often intertwined with socioeconomic and demographic differences, 34 relieving transportation barriers via telehealth for this vulnerable population is significant for patient care and should be explored further. Removing transportation requirements may also reduce the risk of patients driving while impaired to treatment.

Though telehealth may improve access to care for some, there are ongoing barriers to telehealth care including access to private space, broadband internet access, and low technology literacy. In prior work, providers identified lack of privacy as a barrier to receiving care via telehealth for their patients.35 Future research might explore additional spaces to participate in telehealth when privacy at home is compromised, such as using mobile health units, a strategy used in other treatment.36 Findings related to broadband internet access were particularly relevant. Lower income has been associated with lower levels of technology adoption; 40% of US adults with lower income did not have broadband access at home or own a laptop or computer, with cost cited as the most significant cause.37 Considering that telehealth can be accessed by phone or video, both modalities may need to be offered and covered by insurance to improve AUD treatment utilization and accessibility. Presently, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid and some insurance companies are temporarily reimbursing telephone visits for specific services including behavioral health, however the future of this and video visits is still uncertain and there remains debate on what phone services should be covered versus what needs to be done via video.38 Additionally, some participants reported poor technology literacy, including those age 65 and older. Although older patients are good candidates for telehealth, they may need more support with using the technology.35 Alongside existing efforts in some healthcare systems like the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) to distribute internet-connected tablets and provide technical assistance39, additional efforts to incorporate technology education sessions should continue to be utilized across settings.

Because our participants were recruited remotely and our interviews were completed early in the COVID-19 pandemic, several factors relating to telehealth engagement may have been influenced by the pandemic experience. Reductions in how frequently some participants left their homes may have facilitated a greater familiarity with telecommunications. Also, changes to in-person socialization may have influenced participants’ responses. Some participants referenced errands outside the home as a source of social support, which became less frequent during early phases of the pandemic. As such, some individuals’ positive perceptions of telehealth may have been affected because it provided social connection. Alternatively, some participants may experience fatigue from frequent remote activities and be reluctant to engage in psychotherapy virtually. Future work might consider utilizing both in-person and remote recruitment and interviews to see if any differences are found.

Lastly, patients’ preferences should be considered when determining which modalities to offer. Some patients may always prefer in-person visits, even with significant travel so efforts to increase accessibility of in-person AUD treatment must continue to be prioritized. Ultimately the decision to use telehealth may depend on a variety of factors, including patient preferences, symptoms, and treatment needs. Future research should examine which patients benefit more from telehealth and how choice in treatment modality may affect treatment outcomes.

There were some factors that may limit generalizability, including a predominately male, White, and Veteran sample. Future studies should sample from community and other healthcare settings. The VHA invested substantially in telehealth infrastructure prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic,40 which may lead to differences in patient experiences for those receiving care in other systems. Also, because interviews were completed during the early pandemic, we cannot disentangle the effects of in-person restrictions on perceptions of telehealth. Additionally, we did not explore SUD treatment history, which may have influenced participant’s overall willingness to do any AUD treatment. Finally, interviews may not have captured all perspectives related to AUD care delivered via telehealth. Future research might address these gaps by further exploring nuances of AUD care, including individual and group psychotherapy, across varied samples and inquiring about treatment history.

Conclusions

Ultimately, we found that patient perceptions of telehealth treatment for AUD varied across groups. These results highlight the importance of offering telehealth as an option for patients who may prefer receiving treatment through this modality or would be interested in trying telehealth. Considering the large gaps in AUD treatment, telehealth should be designed to function as a facilitator to care, not an additional barrier. In the words of one participant, “Once all the COVID-ness has passed…I think it would be a great thing to provide [telehealth] as an option, so that way you know that regardless of what your physical or mental state is, you can still get the treatment you need.”

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

This project was supported by Dr. Lin’s Career Development Award (CDA 18-008) from the US Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Service and funding from the VA Office of Connected Care (OCC 21-11). For the remaining authors none were declared.

References

- 1.CDC. Alcohol-Related Deaths. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published July 6, 2022. Accessed November 15, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/features/excessive-alcohol-deaths.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Report - Alcohol-Attributable Deaths, US, By Sex, Excessive Use. Published 2022. Accessed January 22, 2023. https://nccd.cdc.gov/DPH_ARDI/Default/Report.aspx?T=AAM&P=612EF325-9B55-442B-AE0C-789B06E3A8D5&R=C877B524-834A-47D5-964D-158FE519C894&M=DB4DAAC0-C9B3-4F92-91A5-A5781DA85B68&F=&D=

- 3.NIAAA. Understanding Alcohol Use Disorder ∣ National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Published 2021. Accessed April 26, 2022. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/understanding-alcohol-use-disorder [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMartini KS, Devine EG, DiClemente CC, Martin DJ, Ray LA, O’Malley SS. Predictors of Pretreatment Commitment to Abstinence: Results from the COMBINE Study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(3):438–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witkiewitz K, Heather N, Falk DE, et al. World Health Organization Risk Drinking Level Reductions Are Associated with Improved Functioning and Are Sustained Among Patients with Mild, Moderate, and Severe Alcohol Dependence in Clinical Trials in the United States and United Kingdom. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2020;115(9):1668–1680. doi: 10.1111/add.15011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olfson M, Blanco C, Wall MM, Liu SM, Grant BF. Treatment of Common Mental Disorders in the United States: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(3). doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez P, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Ye Y, et al. Mental health and drinking to cope in the early COVID period: Data from the 2019–2020 US National Alcohol Survey. Addict Behav. 2022;128:107247. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbosa C, Cowell AJ, Dowd WN. Alcohol Consumption in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. J Addict Med. 2021;15(4):341–344. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Da BL, Im GY, Schiano TD. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Hangover: A Rising Tide of Alcohol Use Disorder and Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease. Hepatol Baltim Md. 2020;72(3):1102–1108. doi: 10.1002/hep.31307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeo YH, He X, Ting PS, et al. Evaluation of Trends in Alcohol Use Disorder–Related Mortality in the US Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2210259. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.10259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin L (Allison), Fernandez AC, Bonar EE. Telehealth for Substance-Using Populations in the Age of Coronavirus Disease 2019: Recommendations to Enhance Adoption. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1209–1210. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill RD, Luptak MK, Rupper RW, et al. Review of Veterans Health Administration telemedicine interventions. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(12 Suppl HIT):e302–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, Edmonds N, Rossi MI. Creation of an Interprofessional Teledementia Clinic for Rural Veterans: Preliminary Data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092–1099. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flodgren G, Rachas A, Farmer AJ, Inzitari M, Shepperd S. Interactive telemedicine: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD002098. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002098.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, Johnston B, Callahan EJ, Yellowlees PM. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed J E-Health Off J Am Telemed Assoc. 2013;19(6):444–454. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, Pruitt LD, Luxton DD, Johnson K. Patient Perceptions of Telemental Health: Systematic Review of Direct Comparisons to In-Person Psychotherapeutic Treatments. Telemed J E-Health Off J Am Telemed Assoc. 2015;21(8):652–660. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruse CS, Lee K, Watson JB, Lobo LG, Stoppelmoor AG, Oyibo SE. Measures of Effectiveness, Efficiency, and Quality of Telemedicine in the Management of Alcohol Abuse, Addiction, and Rehabilitation: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(1):e13252. doi: 10.2196/13252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin LA, Casteel D, Shigekawa E, Weyrich MS, Roby DH, McMenamin SB. Telemedicine-delivered treatment interventions for substance use disorders: A systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;101:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(7):821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1973;51(1):95–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips KA, Morrison KR, Andersen R, Aday LA. Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. Health Serv Res. 1998;33(3 Pt 1):571–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadkarni A, Massazza A, Guda R, et al. Common strategies in empirically supported psychological interventions for alcohol use disorders: A meta-review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2023;42(1):94–104. doi: 10.1111/dar.13550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huebner RB, Kantor LW. Advances in Alcoholism Treatment. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;33(4):295–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beebe James. Rapid Assessment Process: An Introduction. AltaMira Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton Alison. Qualitative Methods in Rapid Turn-Around Health Services Research. VA HSR&D National Cyberseminar Series: Spotlight on Women’s Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.QSR International. Best Qualitative Data Analysis Software for Researchers ∣ NVivo. Published March 20, 2018. Accessed January 22, 2023. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home?creative=605555104699&keyword=nvivo&matchtype=b&network=g&device=c&gclid=CjwKCAiA2rOeBhAsEiwA2Pl7Q4DhtE_vJZ8Ht0Ma0z6_a8mTkEBliuLM0TZKafUl0iiivcgyoEZpSBoCP0QQAvD_BwE [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bashshur RL, Shannon GW, Bashshur N, Yellowlees PM. The Empirical Evidence for Telemedicine Interventions in Mental Disorders. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(2):87–113. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2015.0206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams SV, Mader MJ, Bollinger MJ, Wong ES, Hudson TJ, Littman AJ. Utilization of Interactive Clinical Video Telemedicine by Rural and Urban Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration Health Care System. J Rural Health Off J Am Rural Health Assoc Natl Rural Health Care Assoc. 2019;35(3):308–318. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magill M, Ray L, Kiluk B, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for alcohol or other drug use disorders: Treatment efficacy by contrast condition. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87(12):1093–1105. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammarlund R, Crapanzano KA, Luce L, Mulligan L, Ward KM. Review of the effects of self-stigma and perceived social stigma on the treatment-seeking decisions of individuals with drug- and alcohol-use disorders. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2018;9:115–136. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S183256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madras BK, Ahmad NJ, Wen J, Sharfstein JS. Improving Access to Evidence-Based Medical Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder: Strategies to Address Key Barriers within the Treatment System. NAM Perspect. 2020: 10.31478/202004b. doi: 10.31478/202004b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuzaki M, Vu QM, Gwadz M, et al. Perceived access and barriers to care among illicit drug users and hazardous drinkers: findings from the Seek, Test, Treat, and Retain data harmonization initiative (STTR). BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):366. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5291-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugarman DE, Horvitz LE, Greenfield SF, Busch AB. Clinicians’ Perceptions of Rapid Scale-up of Telehealth Services in Outpatient Mental Health Treatment. Telemed E-Health. 2021;27(12):1399–1408. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malone NC, Williams MM, Smith Fawzi MC, et al. Mobile health clinics in the United States. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-1135-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vogels E a. Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in tech adoption. Pew Research Center. Published June 22, 2021. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/06/22/digital-divide-persists-even-as-americans-with-lower-incomes-make-gains-in-tech-adoption/ [Google Scholar]

- 38.CMS Waivers, Flexibilities, and the Transition Forward from the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency ∣ CMS. Accessed March 28, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/cms-waivers-flexibilities-and-transition-forward-covid-19-public-health-emergency [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zulman DM, Wong EP, Slightam C, et al. Making connections: nationwide implementation of video telehealth tablets to address access barriers in veterans. JAMIA Open. 2019;2(3):323–329. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooz024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US Department of Veterans Affairs. Connecting Veterans to Telehealth Care.; 2021. https://connectedcare.va.gov/sites/default/files/telehealth-digital-divide-fact-sheet.pdf