Abstract

Background

Patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) are used to drive and evaluate unit and organisational-level healthcare improvement, but also at a population level, these measures can be key indicators of healthcare quality. Current evidence indicates that ethnically diverse communities frequently experience poorer care quality and outcomes, with PREMs data required from this population to direct service improvement efforts. This review synthesises evidence of the methods and approaches used to promote participation in PREMs among ethnically diverse populations.

Methods

A rapid evidence appraisal (REA) methodology was utilised to identify the disparate literature on this topic. A search strategy was developed and applied to three major electronic databases in July 2022 (Medline; PsycINFO and CINAHL), in addition to websites of health agencies in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries via grey literature searches. A narrative evidence synthesis was undertaken to address the review question.

Results

The review resulted in 97 included studies, comprised 86 articles from electronic database searches and 11 articles from the grey literature. Data extraction and synthesis identified five strategies used in PREM instruments and processes to enhance participation among ethnically diverse communities. Strategies applied sought to better inform communities about PREMs, to create accessible PREMs instruments, to support PREMs completion and to include culturally relevant topics. Several methods were used, predominantly drawing upon bicultural workers, translation, and community outreach to access and support communities at one or more stages of design or administration of PREMs. Limited evidence was available of the effectiveness of the identified methods and strategies. PREMs topics of trust, cultural responsiveness, care navigation and coordination were identified as pertinent to and frequently explored with this population.

Conclusions

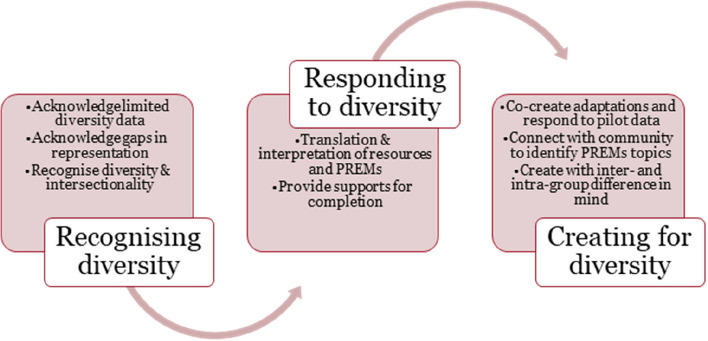

The findings provide a basis for a maturity model that may guide change to increase participation of ethnically diverse communities in PREMs. In the short-medium term, health systems and services must be able to recognise and respond to cultural and linguistic diversity in the population when applying existing PREMs. In the longer-term, by working in collaboration with ethnically diverse communities, systems and services may co-create adapted or novel PREMs that tackle the factors that currently inhibit uptake and completion among ethnically diverse communities.

Keywords: Patient reported experience measures, Multicultural health, Patient experience, Patient satisfaction, Rapid evidence appraisal, Diversity, Ethnicity

Background

Patient Reported Experience Measures (PREMs) are now among the key indicators of performance used to determine healthcare value [1]. PREMs produce local, service and system-level performance data that are essential to direct quality improvement and service development [1]. Inclusive PREMs that capture data from communities who have high healthcare utilisation and poor healthcare outcomes are therefore important to determine their experiences, and target for improvements [2]. Continued underrepresentation of people from ethnically diverse communities in PREMs data means that quality of care concerns from these communities are not identified and addressed.

People from ethnically diverse backgrounds, who speak a language other than a national language at home, have one or both parents born overseas, and/or have low proficiency in the national language/s, experience higher rates of healthcare-associated harm and preventable hospitalisations than the general population [3]. Understanding the experiences of people from ethnically diverse communities via PREMs provides an avenue to drive person-centric improvements to redress this inequity in service delivery and care outcomes. Yet limited accessibility of PREMs in terms of their structure, content and approaches to administration can prohibit their completion to improve care for people from ethnically diverse backgrounds, along with several other priority populations.

People from ethnically diverse backgrounds face specific barriers in accessing and completing PREMs that are subject to intra- and inter-group variation. Factors such as language proficiency, digital and health literacy [4], trust in government, culturally inappropriate content and limited resources to support participation create barriers for people from ethinically diverse backgrounds to participate in PREMs [5]. Widely used PREMs instruments are closed-item surveys, include technical and complex language and phrasing, and contain between 50–80 items [6, 7].

Targeted strategies and methods to increase uptake and completion of PREMs among ethnically diverse communities may contribute to reducing barriers to participation [8]. Synthesising evidence from existing studies that have captured patient-reported experiential data provides insight into the strategies and methods that have been used and may be effective in increasing participation of ethnically diverse communities in PREMs. This knowledge may inform population-based PREMs instruments and data collection approaches. Therefore, the aim of this review was to identify evidence in the peer-reviewed and grey literature of the strategies and methods employed in patient-reported experience measurement with people from ethnically diverse backgrounds to inform policy and practice.

Methods

A rapid evidence appraisal (REA) methodology was utilised to address the review objective because this project was undertaken to inform policy and practice for NSW Ministry of Health, Australia. REA is widely applied to answer policy-related questions that require expansive literature to be explored to answer a focused question within a limited timeframe [9]. REA rigorously follows established systematic review methodology to search and appraise existing evidence, limiting selected aspects of the review process to shorten the review timespan while still enabling the depth of current knowledge to be appraised [10]. In this REA, the search was limited to three electronic databases to enable a breadth of literature to be explored including grey material. The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) guideline for REAs was followed [10].

To ensure a search strategy that was both sensitive and specific, comprehensive search strategies were developed by a medical information specialist for the electronic databases of published literature and for use with grey literature. The search strategy was applied to the following electronic databases in June 2022 by the medical information specialist: Medline; PsycINFO and CINAHL. A research team member (MPI) applied the same search terms to the websites of health agencies in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in which understanding and improving patient experience has been identified as a key outcome in relation to value-based care. In addition, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—PRISMA statement—was used to guide the reporting of this REA [11].

Inclusion criteria

Articles were included if they met the following inclusion criteria:

Types of publication: Publications available in English, reporting original primary empirical or theoretical work, and published from the year 2000 onwards, which is contemporaneous with exploration of patient experience in health settings.

Types of settings: Any healthcare setting, including but not limited to public or private hospitals, day procedure centres, general practice or other primary/community care in OECD countries.

Types of study design: Conceptual, theoretical, quantitative, or qualitative studies of any research design.

Types of population: Health care consumers from ethnically diverse backgrounds who access health services were included; defined as born overseas or who have one or more parents born overseas in a country where English is not a national language, and/or who speak a language other than English at home; and/or who have low English language proficiency.

Interventions: Strategies or methods to increase uptake and/or completion of PREMs.

Outcomes: PREMs included any form of data “from patients on what happened to them in the course of care or treatment” were eligible for inclusion [12]. In this review, the focus was on experiences of a healthcare encounter or a service rather than general attitudes or perceptions of healthcare.

Exclusion criteria

Articles were excluded if they reported general beliefs or attitudes about healthcare rather than experiences of a care episode, along with those that did not meet the above criteria, or reported reviews, protocols, opinion, or editorial pieces.

Study identification and selection

Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) was used for study screening and management. Two reviewers (MPI, UC) screened the titles and abstracts in Covidence against the eligibility criteria. Full-text documents were obtained for all potentially relevant articles. The eligibility criteria were then applied to the articles by three reviewers (AC, MPI, UC). Four team members then met to finalise the eligible articles for inclusion across the published and grey literature (MPI, RH, RM, EM).

Data extraction and synthesis

A narrative evidence synthesis was undertaken to address the project aim of collating established experience measurement approaches and the impact of these methods on participation of ethnically diverse individuals [13]. Separate data extraction tools were developed for full-text articles and the grey literature and each tool was used to extract relevant information using a data extraction form created in MS Excel. Evidence synthesis occurred in stages and was conducted using a team-based approach involving seven members of the research team (RH, MPI, AC, CA, UC, RM and EM). Following the tabulation of initial descriptions of the included studies, their approaches and techniques, and the resulting impact on participation (where reported), team members individually reviewed the included articles. The group met to discuss key findings, to explore commonalities in current approaches and techniques that have been successfully applied, and to identify any challenges and mitigation strategies adopted. Through this group discussion, initial themes were generated and used to describe the evidence available. Two research team members developed the results content and shared this content with the wider group to further refine the identified themes.

Results

Search results

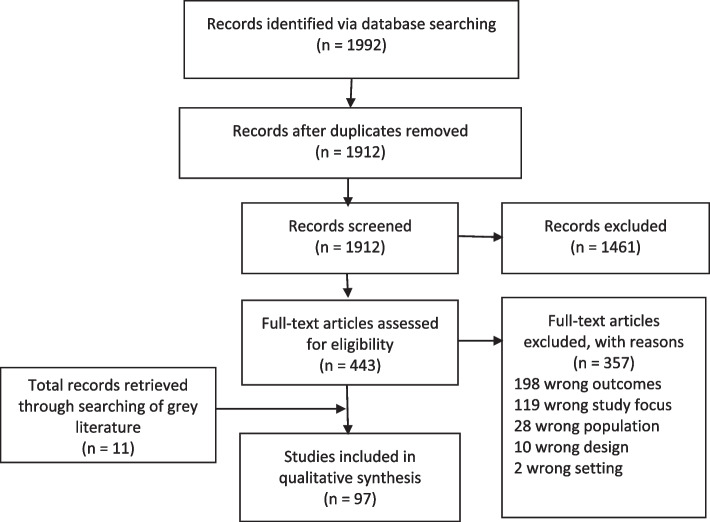

The systematic database search retrieved 1992 articles. After removal of 80 duplicates, 1912 articles remained. A total of 1461 articles were excluded after title and abstract screening. The remaining 443 articles underwent full-text review, of which 357 were excluded. A total of 97 documents were included, composed of 86 peer-reviewed journals and 11 documents from grey literature. Figure 1 demonstrates the search and selection process. Descriptions of eligible studies and results were tabulated. Tables 1, 2 and 3 show summaries of the included quantitative, mixed methods and qualitative articles from the electronic data search respectively. Table 4 shows the summary of grey literature articles.

Fig. 1.

Prisma flow diagram CALD report

Table 1.

Summary of included studies: quantitative N = 27

| Author | Year | Country | Setting | Aspect measured in the Patient Reported Experience measure: topics and relevant questions | Sample and population | Description of qualitative and quantitative data collection (i.e. survey) | Specific strategies employed to improve participation of CALD population | How were recruitment sites identified and examples of places | Evidence of effectiveness of strategy to increase CALD patient participation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Bockey | 2020 | Germany | Primary care | Integrated health care facility (ICF) | N = 102 patients |

Cross sectional study Quantitative study: Questionnaire with open and closed ended questions Questions derived from the validated German ZUF-8 client satisfaction |

• Questionnaire was translated into five key languages spoken including English, German, Arabic, French and Chinese • English and German language questionnaires were offered verbally as face-to-face interviews • peers were permitted to assist with the completion of questionnaires in other languages • The questions were pilot tested with the Integrated care facility staff members • Intra-method mixing, a technique that uses both open and closed ended items to achieve more comprehensive data |

Participants (asylum seekers and refugees) living in the Integrated care facility were recruited | Response rate -60% |

| 2. | Boutziona | 2020 | Greece | Hospital |

Emergency department experience Specific questions: Do you visit Albania looking for medical care? Do you think it is better to address a health problem in Greece than in Albania? |

Snowballing sampling- N = 167 adult patients of Albanian origin completed the questionnaire |

Cross sectional study Quantitative: Survey |

• A pilot questionnaire was initially developed and tested on a sample of 15 patients (Albanian immigrants), to determine its applicability and validity to the specific population • The questionnaire was cross translated from Greek into Albanian, and vice-versa, in order to ensure coherence between the Greek and Albanian versions • Eligible patients were asked if they would like to participate in the study while waiting for their test results |

adult patients of Albanian origin who visited the ED of a tertiary general hospital was invited to participate |

Response rate 83.5% (167/200 surveys completed) Although 75% of participants reported they had good knowledge of the Greek language and could use it to function in their daily lives, only 27.5% of them chose to complete the questionnaire in Greek |

| 3. | Cook | 2015 | USA | Primary care | Integrated care: health centre medical home care | N = 488 patients surveys |

Patient experience Quantitative Study: Clinician and Group Surveys Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CG-CAHPS) and the CG-CAHPS PCMH item set |

• As many surveyors were multi or bilingual, patients were surveyed in their chosen language of English, Spanish or Haitian Creole • Patients were advised that they would receive a $5 Wal-Mart gift card for completing the survey • The project team developed an initial question set. The final tool was pilot tested with four patients, which resulted in minor revisions to wording |

All surveys were conducted face-to-face at the Health Centres by faculty and students from a Master of Public Health program |

Response rate: 96.6% (488/505 surveys completed) |

| 4. | Cook | 2016 | USA | Primary Care | Integrated care: Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) | N = 351 patients |

cross-sectional study design Quantitative: 36 item questionnaire designed from previously validated questionnaires |

• The questionnaire was translated into Spanish and Haitian Creole by native language speakers to improve the cultural appropriateness of survey questions • Administered questionnaire online and face to face in different languages • Patients, if they asked, had access to a printout of the questions to follow along with the surveyor • Patients received a $5 gift card for completing the questionnaire |

At each of the four sites, surveyors had full access to screen and recruit patients from waiting rooms, using a convenience sampling approach. Surveyors approached adult patients who were not otherwise engaged (eg, talking on cell phone; sleeping) |

Estimated 90% |

| 5. | Detollenaere | 2018 | Europe | Primary care | Patient satisfaction with general practice | Patients completed the questionnaire Europe wide |

Cross-sectional study Quantitative questionnaire |

• Social groups were identified according to four patient characteristics: education, household income, ethnicity and gender (male/female) | Patients sitting in the waiting room of the GP were asked to participate | Response rate was 74.1% |

| 6. | Eskes | 2013 | USA | Primary care | Spanish Patient satisfaction with primary care | Consecutive sampling | Quantitative questionnaire |

• Spanish version of the survey used • Survey shortened in order to be completed in clinical setting • Participants were provided with a cover letter in Spanish explaining that their participation in the survey was voluntary |

Patients recruited from community care clinics | Not reported |

| 7. | Gurbuz | 2019 | Germany | Hospital | Patient satisfaction: Maternity care | N = 410 patients |

Quantitative questionnaire. A modified version of the Migrant Friendly Maternity Care Questionnaire (MFMCQ) |

• Questionnaire translated in in German, English, French, Spanish, Arabic and Turkish was used • Offering to complete the questionnaire in an interview |

Patient invited from sites where they had given birth |

The overall response rate of evaluable questionnaires was 58.4% (410 out of 701 women) |

| 8. | Henderson | 2018 | UK | Hospital | Patient satisfaction with Maternity Care |

Random sample N = 5332 patients |

Cross sectional study Quantitative questionnaire |

• Patients were mailed the questionnaire • Invitation to participate included a sentence in 18 different languages which encouraged them to call a Freephone number to enable them to complete the questionnaire by interview or through an interpreter if preferred |

none | 5332 women responded to the survey (a usable response rate of 54%) |

| 9. | LaGrandeur | 2018 | USA | Community setting | Patient experience with student directed free clinic for pediatric patients | N = 63 patients |

Quantitative questionnaire Parents of patients were surveyed using an instrument created by Commitment to Underserved People (CUP) students through small group discussion in 2017 for use in the TotShots program |

• Offered in English and Spanish |

Patients recruited using social media, and email communication with school district social workers, coaches, and nurses |

Response rate 95.4% |

| 10. | Lim | 2019 | Australia | Hospital | Care coordination and health literacy | N = 68 patients and n = 8 carers |

Cross sectional study Quantitative questionnaire Health Literacy and Cancer Care Coordination questionnaires |

• Chinese versions of both HLQ and CCCQ, which were translated using the forward‐backward procedure were used • Questionnaire pilot tested with leaders of Chinese community cancer support organisations in Sydney, Australia to ensure clarity and cultural appropriateness |

Participants recruited if they attended Chinese community cancer support organisations or cancer treatment centres across the wider Sydney region |

None reported |

| 11. | Lindberg | 2019 | Denmark | Hospital | Mental health treatment | n = 686 |

Cross sectional study Quantitative questionnaire- patient satisfaction questionnaire |

• Questionnaire developed after clinical experience with a multicultural patient population • The questionnaire was forward–backward translated from Danish to five additional languages: Arabic, Bosnian, English, Persian and Russian |

Participants received the questionnaire after the last treatment session and could complete it immediately or at home and return it by mail. If participants missed their last session, the questionnaire and a stamped return envelope were mailed to them | Response rate 76.6% |

| 12. | Mander | 2016 | Australia | Hospital | Maternity care | N = 655 women with CALD background |

Cross sectional study Quantitative questionnaire- Having a Baby in Queensland Survey 2012 |

• Multiple formats of the survey: The survey could be completed on paper (Returned via mail with provided reply-paid envelope) or online • Survey could also be completed over the telephone with a trained female interviewer and translator if required • Multiple language instructions: Instructions for survey participation and completion were provided in English and 19 other languages • Special questions to identify CALD population: (“Where were you born?” “Do you identify with any cultural group(s) or ethnicity?”; “What language(s) do you speak at home?”) |

None | None |

| 13. | Martino | 2022 | USA | Community setting | Integrated care: Healthcare experience | Hispanic patients living in rural residence experience with healthcare | Quantitative questionnaire- Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey |

• Multiple languages and multiple formats: The surveys were administered in English and Spanish by mail, with bilingual telephone follow-up of nonrespondents • Specific questions to identify race /ethnicity: Are you of Hispanic or Latino origin or descent? |

none | Response rate: 42–43% |

| 14. | Moroz | 2003 | USA | Community setting | Healthcare experience: convalescence care | N = 70 patients | Quantitative questionnaires |

• The survey available in Chinese language • Patients could be assisted in completing the survey |

Via patient brochures Outreach specialist visited 12 community sites Relevant doctors were provided with information about the program |

none |

| 15. | Nayfeh | 2021 | Canada | Hospital | End of life care for patients with diverse backgrounds | N = 1543 |

Quantitative questionnaires: End-of-Life Satisfaction Survey was used to measure satisfaction with the quality of inpatient end of-life care from the perspective of next-of-kin of recently deceased patients at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Ontario |

• The items included: patient race/ethnicity (Caucasian, Caucasian, Mediterranean, Black, East Asian, South Asian, Southeast Asian, Middle Eastern, Hispanic, First Nations, and other); patient religion [Atheist, Buddhist, Christian (all denominations), Hindu, Jehovah’s Witness, Jewish, Mormon, Muslim, Sikh, no religion, other]; level of religiosity/spirituality; and preferred spoken language • Invitation letter accompanying the survey explained the confidential and voluntary nature of the request. One reminder survey was sent three weeks after the initial mail-out to those who did not respond |

none | Response rate was 37.7% |

| 16. | Olausson | 2016 | Sweden | Public dental services | Dental services | Quantitative questionnaires: Dental Visit Satisfaction Scale (DVSS) |

• Multiple languages: The questionnaires were available in English, Swedish, Arabic and Farsi • At the clinics all patients aged 18 or older were asked to participate. Most completed the questionnaires in the waiting room prior to treatment, but five people answered the questionnaires at home and mailed them back • The participants were asked about the following background factors: Gender; Age; Education; Dental habits; Country of origin; Skills in Swedish language |

Two of the clinics were located in multicultural areas with a high proportion of foreign-born patients | response rate was 74% | |

| 17. | Parast | 2022 | USA | Hospital | Emergency department—racial/ethnic differences in the experience of care received during an ED visit |

N = 16,006 eligible patients discharged from the 50 hospitals were randomly sampled survey modes |

Quantitative questionnaires: Emergency Department Patient Experience of Care (EDPEC) DTC Survey |

• Different modes of survey administration: mail only, telephone only, or mixed mode (mail with telephone follow-up); the survey was conducted in English • Linear regression used to measure the differences in patient experiences based on racial /ethnic group |

None reported | response rate: 20.25% |

| 18. | Pinder | 2016 | UK | Hospital | Patients experiences of receiving care for cancer |

N = 138 878 responses from 155 hospital trusts across the National Health Service in England |

Quantitative questionnaires: National Cancer Patient Experience Survey (NCPES) | • Survey included questions related to: Sex, employment status and ethnicity | The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), the official composite measure of deprivation in England, was derived on the basis of patient postcode ascertained from the health record. This was done to ascertain whether the patient was categorised as deprived | Response rate of 63.9% |

| 19. | Platonova | 2016 | USA | Community Setting | Integrated care: Patient-centered medical home (PCMH) | N = 548 patients |

Cross sectional study Quantitative questionnaires: multi-item Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems scales developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

• Patients were approached by research staff while waiting for their appointments • Multiple languages: The survey was available in English and Spanish. Survey • items were translated from English into Spanish by professional translators and reviewed by Spanish-speaking healthcare professionals • Some screening questions were removed or rephrased to shorten the survey, reduce the complexity and to reduce the reading level |

Study conducted in 2 independent free clinics in a large metropolitan area in the Southeastern United States | Response rate 66% |

| 20. | Redshaw | 2018 | UK | Hospital | Maternity care: Care associated with stillbirth | N = 473 participated in the survey | Quantitative survey | • An information sheet in 18 non-English languages gave information regarding a contact number for the team | Response rate 30% | |

| 21. | Ryan | 2018 | USA | Community setting | Mental health: Promotion of mental health (Mindfulness) among Latina immigrant women | N = 24 women | Quantitative: pre and post test survey |

• Spanish version of the surveys used and demographic information was collected • Trained bilingual interviewers administered the surveys to participants in separate sessions before and after the intervention’s five sessions • Participants received a gift card in the amount of 20 dollars for each survey completed |

None | None reported |

| 22. | Schinkel | 2016 | Netherlands | Community Setting |

Integrated care: Exploration of patients’ preferred and perceived participation and doctor–patient concordance in preferred doctor–patient relationship on patient satisfaction |

N = 236 patients |

Quantitative questionnaires: Pre and post test design After signing the informed consent form in the waiting room, participants were given preconsultation questionnaire. Following the consultation with the GP, they were given a post consultation questionnaire |

• Recruitment in waiting rooms • Recruited both Dutch and bilingual Turkish-Dutch assistants for data collection • Multiple languages: questionnaires available in Dutch and Turkish • The patient questionnaires were pilot-tested twice among low-educated and low-literate Dutch and Turkish-Dutch people to ensure that all items were comprehensible to the targeted populations |

none | none |

| 23. | Schutt | 2020 | USA | Hospital | patient navigators and services for chronic illness | N = 157 patients before and N = 378 patients after |

Quantitative questionnaires: Pre and post test design Health care satisfaction surveys both before and after the program design |

• surveyed by phone both before and after the program design • Multiple languages: Questionnaires were translated into Spanish and Portuguese |

none | none |

| 24. | Sharif | 2019 | USA | Community care |

Integrated care: healthcare experiences of Cambodian American refugees and immigrants |

N = 308 patients |

Quantitative questionnaires: questionnaires and medical records from two community clinics in Southern California |

• A bilingual Khmer research assistant described the study to each patient, obtained informed consent from any interested patients and administered the baseline questionnaire • Data were collected on the respondents’ sociodemographic information, including gender current age, age at US entry, year of immigration to the US educational attainment, religious affiliation, employment status, participation in Food Stamps program, total annual household income and household size |

patients recruited from two community clinics (one which has 11 different locations and the other with one location) in Long Beach, California |

none |

| 25. | Shin | 2020 | USA | Hospital | Patient experience with clinical pharmacist services | N = 99 Patients |

Cross sectional study design Quantitative questionnaire: Oxford Patient Involvement and Experience Scale |

• Multiple languages: survey offered in English and Spanish • Clinical pharmacists read out loud a script which described the survey purpose (i.e., to get feedback about and improve pharmacist services), directions, and privacy procedures |

The patients completed surveys in a designated area in the clinic, but away from their clinical pharmacist, and surveys were inserted into a sealed box | none |

| 26. | Soo | 2013 | Canada | Hospital | Radiation therapy | N = 128 | Quantitative questionnaire: patient satisfaction survey |

• Multiple languages: Chinese version of the questionnaire • The survey was pre-tested on volunteers and staff members for construct validity |

No information | none |

| 27. | Yelland | 2015 | Australia | Hospital |

Maternity care—views and experiences of immigrant women of non-English speaking background (NESB) giving birth in Victoria, Australia |

N = 4516 | Quantitative questionnaire: |

• Multiple languages: survey available in Arabic, Vietnamese, Cantonese, Mandarin, Somali, Turkish • Women were posted a questionnaire six months following the birth, together with a covering letter, and a reply paid envelope for returning the completed questionnaire |

None | None |

Table 2.

Summary of included studies- Mixed methods N = 9

| Author | Year | Country | Setting | Aspect measured in the Patient Reported Experience measure: topics and relevant questions | Sample and population | Description of qualitative and quantitative data collection (i.e. survey) | Specific strategies employed to improve participation of CALD population | How were recruitment sites identified and examples of places | Evidence of effectiveness of strategy to increase CALD patient participation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Bains | 2021 | Norway | Hospital | Maternity care |

N = 401 international migrant women, ≤ 5 years length of residency in Norway (giving birth in urban Oslo) answered the questionnaire (87.6% response rate) |

Cross-sectional study Mixed methods: Face to face interviews and a modified version of the Migrant Friendly Maternity Care Questionnaire (MFMCQ) The original questionnaire was adapted to the health system setting of Norway and modified after inputs from pilot testing |

• Eligible women were recruited either on admission for delivery or at the postnatal ward • Interviews conducted face to face in the women’s own language of choice after birth, using an interpreter when needed • Written translations of the questionnaire were provided in nine languages: Arabic, Dari, English, French, Norwegian, Somali, Sorani, Tigrinya and Urdu • Training workshops for all the research personnel. The interviewers met regularly to discuss challenges and experiences • The user representatives (from non-governmental organisations and relevant migrant communities) gave feedback on readability, validity and cultural sensitivity of the questionnaire before data collection. After data collection, preliminary findings were presented, and interpretations were discussed with user representatives |

Interviews were conducted in the postnatal ward |

Response rate (87.6% response rate) |

| 2. | Damery | 2019 | UK | Hospital |

Mental health: Psychological difficulties (distress) in patients with end stage renal disease Specific questions included in the survey exploring the patient’s ethnicity |

Survey sent to N = 3730 eligible patients Purposive sampling for the interviews: N = 46 Patients with end stage renal disease (ENDS) interviewed |

Mixed methods: cross-sectional survey and semi -structured interviews |

• Postal survey developed for the project and included some validated measures to assess aspects of distress and emotional adjustment • Questions included in the survey explored: socio-demographic and clinical information (age, gender, ethnicity, time since diagnosis) • Patients could involve a carer/ family member to complete the survey and this could be indicated on the survey |

No specific information | Response rate 27/9% |

| 3. | Dang | 2017 | USA | Hospital | Patients’ experience with the mobile phone intervention for heart failure | N = 42 patients |

Randomised control trial and longitudinal measurement at 1 month and 3 months Mixed methods: Patient interviews and survey |

• A 31item survey was developed for the study • Multiple languages offered for the interviews: Spanish and English • Questions in the survey explored: sociodemographic information like age, gender, ethnicity |

Patients recruited from the hospital | None reported |

| 4. | Hyatt | 2018 | Australia | Hospital | Patients experience with a communication intervention package (comprising consultation audio-recordings and question prompt lists) especially designed for CALD patients | N = 18 patients completed the interview and N = 17 completed the survey |

Randomised control trial Mixed methods: Patient interviews and surveys |

• Consent to participate in the study was obtained in the patient’s predominant language | Patients recruited from the hospital | None reported |

| 5. | Kaltman | 2016 | USA | Primary care | Mental health: Latina immigrants experience with a mental health intervention |

Convenience sample of Latina immigrants (N = 28) with depression and/or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for primary care clinics that serve the uninsured |

Post-intervention data collection Mixed methods: survey and interviews |

• Multiple languages: Interviews conducted in Spanish • Bilingual staff members conducted the interviews and the analysis • $20 and $30 gift cards |

The intervention was conducted at a community primary care clinic in an area that serves low-income, uninsured patients, many of whom are Latino immigrants Recruitment was done via posted flyer, referral by clinic staff, and outreach screening in the waiting room | None reported |

| 6. | Liu | 2017 | USA | Hospital | Maternity care: Birth experience of immigrant women with an intervention designed for prenatal care | N = 39 Spanish women |

Post-intervention data collection Mixed methods: Interviews and surveys |

• Bilingual staff members conducted the interviews • Demographic information collected in the survey |

Patients recruited from the hospitals | None reported |

| 7. | McBride | 2017 | Australia | Community care | Patients experience with an integrated healthcare service for asylum seekers and refugees | Purposive sampling (N = 18) participated in the interviews and (N = 159) completed the surveys |

Patient experience Mixed methods: Interviews and survey |

• Bicultural workers with experience in cross-cultural research were involved throughout each stage of the project, including methodology design, the development of survey tools and interview guides, recruitment, and data collection • Participant Information and Consent Forms were available in community languages • Multiple languages- interviews conducted in the patient’s preferred language |

Interviews were conducted in a private room at Monash Health and were digitally recorded with permission from participants. Interviews were conducted in participants’ chosen language, and accredited interpreters were used Clients discharged attended a discharge information session. This meeting was used to administer a client feedback survey with consenting clients |

None reported |

| 8. | Mendoza | 2018 | USA | Community setting | Integrated care: Healthcare experience | N = 419 Latina women immigrants is associated with satisfaction with health care | Mixed: Qualitative interviews and surveys |

• A structured face-to-face interview conducted in Spanish, either in the respondent's home or a community-based site, based on the participant's preference • Respondents received $20 cash for their participation • Details on study procedures provided in Spanish • Spanish language translation methods of measures like Social mobility measures and satisfaction with care (the medical mistrust and acculturation scales already had a Spanish versions) |

Participants were recruited from various community sites in New York City, and by flyers posted in designated areas in the target communities (e.g., apartment buildings and community-based agencies and service facilities) |

None |

| 9. | Torres | 2020 | USA | Community setting | Health intervention to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in Latino immigrant men | N = 73 completed the survey and N = 20 completed the in-depth interview |

Randomised control trial Mixed methods: in depth interviews and surveys (pre and post-test) |

• Study participants received $30 for each survey and interview completed • Demographic information of the participants was collected in the survey • All surveys were interviewer administered by a promotor |

Participants in study were recruited from a community-based organization serving Latino immigrants in Seattle, WA. The organization served as a day labor worker center, and therefore many Latino immigrant men came to the organization seeking employment each day | None reported |

Table 3.

Summary of included studies- Qualitative (N = 50)

| Author | Year | Country | Setting | Aspect measured in the Patient Reported Experience measure | Sample and population | Description of qualitative data collection | Specific strategies employed to improve participation of CALD population | How were recruitment sites identified and examples of places | CALD Relevant topic/question areas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abuelmagd | 2019 | Norway | Community | Diabetes mellitus care |

N = 18 Immigrant Kurdish patient |

Focus group discussion |

• Patient recruited through Kurdish networks and common places where Kurdish population frequently visit like mosques and cafes • Research team-member who led FGD had a Kurdish background • Focus group discussion held in meeting room convenient for participant to attend |

Sites were places in Oslo that the general Kurdish population frequently visits (Kurdish mosques and cafes) | Interview guide was developed based on study aims and previous research on non-Western immigrants with T2DM |

| 2 | Ahrne | 2019 | Sweden | Community | Maternity care: specifically, Antenatal care |

N = 16 mothers N = 13 fathers Somali immigrants |

Focus group discussion |

• Focus group discussion held in locations where Somali migrants are present • Somali-speaking research assistant, interpreters and facilitators • Recruitment took place through existing networks within the Somali diaspora, public preschools and Child Health Centres • Data collection conducted in Somali language and translated to Swedish • Refreshments were offered |

Sites were identified because many Somali people migrated and lived in those locations. Also, a third site was identified by the mid-wives who had experience of working in that area | None |

| 3 | Alkhaled | 2022 | Norway | Hospital | General health care experience |

N = 20 Newly immigrated, Arabic speaking patients, Purposive sampling |

In-depth interviews |

• Participant information sheet and Consent form in Arabic language • According to the participants’ wishes, all interviews were conducted in their homes • Interviews conducted in Arabic • One Research team member had an Arab background and spoke Arabic. Other 3 researchers had an immigrant research focus |

Sites were five hospitals. There is no information on how they were selected | Interview guide addressed the themes of linguistic competencies during communication, cultural issues such as values and beliefs, experience of pain, the role of the patient’s family, meals, and their experience in dealing with the Norwegian health-care system |

| 4 | Bitar | 2020 | Sweden | Hospital | Maternity care: evaluation of a communication app |

N = 10 Arabic immigrant women who had used the App at least two times |

Telephone interviews |

• Participants had the choice of in-person or telephone interviews • Interviews were conducted during pregnancy in Arabic by the first author who had an Arabic background • Written informed consent in Arabic was obtained |

Sites were six antenatal clinics in southeast of Sweden where app was launched and used by participants |

• Demography questions included: • Ethnicity • Years of residence in Sweden • Ability to communicate in Swedish |

| 5 | Carlsson | 2016 | Sweden | Hospital |

Maternity care: Experiences and preferences of care following a prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart defect among Swedish immigrants |

N = 9 Pregnant immigrants and their partners were consecutively recruited following a prenatal diagnosis of a congenital heart defect in the foetus |

Interviews |

• Participants were given the option to either be interviewed together with their partner, or individually. All couples chose joint interviews • The second author, a female sociolinguistic researcher with previous experience of conducting face-to-face interviews and with no clinical contact with the participants, conducted all five interviews in Swedish. Four Interviews conducted with the aid of a professional interpreter |

Site was a tertiary referral centre for foetal cardiology. There is no information on how it was selected |

Demography questions included: • Country of birth |

| 6 | Cervantes | 2021 | USA | Hospital |

Hospital care: Experiences of Latinx individuals who were hospitalized with and survived COVID-19 |

Purposive sampling N = 60 Latinx adults |

Semi structured telephone interviews |

Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish according to participants’ preference |

Identified participants via a data query that provided the contact information for individuals who self-identified as Latinx and had been hospitalized for COVID-19, and had an interviewer call them |

Interview guide was developed based on a literature review of race disparities and the COVID-19 pandemic, with a particular focus on Latinx communities |

| 7 | Chu | 2005 | Australia | Hospital | Maternity care: Postnatal Care |

N = 55 Participants. Three Chinese immigrant groups (People’s Republic of China (PRC), Hong Kong and Taiwan) |

face-to face and telephone interviews of over 25 key informants in-depth face-to-face interviews (using an interviewing guide) with 30 women in their homes field visits to identified community organisations; and focus group discussions |

• The project team was multi-disciplinary and multi-lingual in nature • The author employed three research assistants, one each from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Mainland China • The informant had read and signed an informed consent form in the Chinese language |

Participants were recruited through referral by community organisations and the researchers’ own social networks The informants were first approached by telephone, and upon receiving their expressed willingness to participate, were followed up with a home visit at a time nominated by them |

Interview Guide questions included: • general background and migration history of informants • general health conditions before and after immigration; health beliefs and health utilisation behaviour • reproductive health beliefs, behaviour and experience in Australia |

| 8 | Decker | 2021 | USA, Mexico | Community, Hospitals | Maternity Care | N = 74 pregnant and/or parenting adolescents (Mexican origin) | Interviews, focus group discussion |

• A binational team of trained and experienced researchers from Mexico and the United States conducted all focus groups and interviews in the language preferred (Spanish or English) • In recognition of their time and input, respondents received a $20 gift certificate in California while in Mexico, participants received infant supplies, such as diapers, per local institutional recommendations |

• Guanajuato, Mexico, was identified as a traditional point of origin for migrants to California and Fresno, California, was identified as a primary point of arrival for Mexican immigrants • Youth in California were recruited from several community-based organizations serving pregnant and parenting youth • Study researchers used previously established relationships with clinics and organizations in both communities, and staff at these sites recruited youth to participate when they sought services at these sites |

None |

| 9 | England | 2003 | United Kingdom | Primary Care | Paediatric Care | N = 24 mothers, Kurdish and Turkish refugees | Focus group discussion |

• Consent form was provided in the appropriate language • Consent to record the sessions was obtained both in written form and verbally, as literacy levels for written Turkish are very variable among the mainly Kurdish patients • All groups were provided with crèche facilities and refreshments • ‘Health visitors’ and Turkish speaking ‘health advocates’ already working at the clinic. The focus groups were run by the health visitor and a health advocate, both of whom received focus group training prior to the study. In addition, another advocate acted as the interpreter |

Site is a general practice surgery in North London where 18% of the attending patients are Turkish speaking Kurdish refugees | None |

| 10 | Falbe | 2017 | USA | Primary care | AHF (Active and Healthy Families) program to reduce obesity disparities in Latino children | N = 23 parents (Latino immigrants) | In – depth interviews | Interviews conducted in the participant’s preferred language (Spanish or English) | Parents participating in AHF in two clinics in San Francisco Bay area were chosen to participate |

Interviews with AHF participants honed in specifically on “Promotora” qualities, actions, and relationship with patients (“Promotoras” in the trial were Spanish-speaking Latina mothers recruited to engage families, facilitate discussions and understanding of content) |

| 11 | Frahsa | 2020 | Switzerland | Community | Healthcare & social-services for chronic health conditions |

Purposive, priori-defined maximum-variation sampling strategy 1. N = 12 Turkish, N = 12Portuguese, N = 12 German Immigrant women with chronic health conditions 2. N = 12 Swiss women with chronic health conditions |

Multi-method qualitative Study: Semi-structured interviews, Focus Group Discussion Stakeholder Dialogues |

• Interviews were conducted in Turkish, German and Portuguese by 4 bilingual researchers based at Swiss and Turkish universities • Interviews conducted at venues convenient to participants • Interviewees had option to be accompanied by members of their family or acquaintances • Participants received a gift upon completion of the interview • FGD was conducted in the language most comfortable for the greatest number of participants. In addition, a translator was present during the FGDs upon request by the participants • FGD participants received cash incentive and travel costs were covered |

• Study took place at Swiss cantons of Bern and Geneva • Recruitment strategies to reach interviewees were: personal contacts via researchers’ professional and private networks, cultural associations, labor unions, associations for the elderly and retirement homes, academic institutes, hospitals, physiotherapists, and physicians or specialists known to have many immigrant patients and/or command of those patients’ native languages • Also recruited via public leaflets in shops, restaurants, pharmacies, churches etc., social media advertisements, and through snowballing by interviewees |

• Any discrimination faced while living in Switzerland? • Length of stay in in Switzerland? |

| 12 | Garcia-Jimenez | 2019 | USA | Primary Care | Telephone Interpreter Services (TIS) at urban community clinic |

Purposive Sampling N = 13 Spanish speaking immigrants who utilized TIS (N = 7 Ecuadorian, N = 2Columbian, N = 3 Dominican Republic) |

Focus group discussion |

• Focus group dates and times were varied in order to increase the number and diversity of participants • The focus groups were held in the clinic in order to minimize travel barriers to participation • The focus groups were facilitated in Spanish by the primary care resident physician on the research team (native speaker) • 2 research-team members were native speakers |

• Site was an adult primary care clinic at the urban community clinic affiliated with the institution that approved and funded the project • Eligible individuals were recruited by means of flyers, identification by primary care providers, and face-to-face and telephone-based encounters |

Focus Group Guide Barriers & Facilitators: 1.Using an interpreter telephone during a clinic visit makes me feel...... – Why? 2. Do you agree or disagree: Using an interpreter telephone is better than using my limited English. – Why? 3. What has been your experience with telephone interpreter use? 4. What makes it easy to use a telephone interpreter? 5. What makes it hard to use a telephone interpreter? 6. Do you like using the interpreter phone? – if YES, why – if NO, why 7. Do you agree or disagree: My doctor does a good job using the interpreter telephone. – How so? Cultural Barriers: 1. How does using the telephone interpreter affect your relationship with your doctor? 2. Does using a telephone interpreter make you feel differently about the care you receive? 3. Do you prefer your doctor speak Spanish, even if Spanish is their second language, to using the telephone interpreter? – if so, why – if not, why 4. Do you tell your doctor everything if you are using an interpreter phone? – if YES, why – if NO, why 5. What are your thoughts about the interpreter on the telephone? 6. How does the telephone interpreter services compare to other interpreter services? Using a clinic staff member? Using a family member? Baseline Questionnaire included: • Country of origin • English speaking ability • Year of immigration to USA • I have had providers who speak Spanish (Y/N) • My current provider uses an interpreter phone (Y/N) • If given the option, I would use a family-member instead of a telephone interpreter (Y/N) • In the past 12 months I have used an interpreter phone in _______ encounters |

| 13 | Garrett | 2008 | Australia | Hospital | Conceptions of cultural competency in acute health care |

N = 49 patients from non-English speaking backgrounds (NESB) N = 10 carers from NESB [Arabic, Italian Vietnamese, Mandarin, Cantonese] |

Focus group discussion |

• Participant candidates were invited by bilingual research officers to attend the language-appropriate focus group • PI and a bilingual research officer co-facilitated each FG, which was conducted in the relevant community language, with a professional healthcare interpreter formally interpreting proceeding |

The study was undertaken at a tertiary hospital serving a large multicultural community in the western suburbs of Sydney |

Focus groups topics included: • impact of limited English proficiency on hospital experience • access to interpreters |

| 14 | Gilbert | 2019 | Australia | Community | Australian healthcare system & transnational treatment options |

Purposive Sampling N = 34 Indian Immigrants |

Focus group discussion |

• FGD were conducted in various community spaces • They were usually run after-hours or on weekends, to best avoid conflicting with participants' work schedules • FG were facilitated by bilingual Hindi researcher • Participants each received A$20 compensation for their time, light refreshments provided • FG with older group was conducted in Hindi |

• Melbourne was chosen as the city of interest as it has the largest Indian population of any Australian city • Participants were recruited through advertisements placed in community spaces such as local libraries and community centres • Various community groups ran presentations introducing the study |

This study focuses on recent Indian migrants to Australia; their negotiation of the Australian healthcare system and their use of transnational treatment options. By exploring this through a framework of trust, researchers demonstrate how socio-cultural discrepancies in the ways trust is reached in the Indian and Australia healthcare systems respectively results in deficits of trust between Indian migrants and Australian healthcare professionals |

| 15 | Gronseth | 2006 | Norway | Community and primary care | Health and sickness as embedded in social life and cultural values |

Interviews N = 100 Tamil refugees (70 families and 30 single individuals) Observations 50 health consultations |

In-depth interviews, participant observations including healthcare consultations |

• The researcher was a consultant in the Psychosocial Team for Refugees in Northern Norway • In the early stages of the research project, the researcher worked with Tamil interpreters, Tamil refugees who had obtained reasonable skills in Norwegian • When researcher was left alone with informants, they often volunteered supplementary, which tended to include additional emotional and bodily expressed information • When conducting the second stage of research based on the full year of fieldwork, she made less use of interpreters in order to avoid the kind of formality caused by the situation. A methodological approach of ‘being with’ and sharing experiences, or ‘attending’ to the field, was emphasized. a Broader spectrum of data sources was used, including verbal and cognitive data based on interviews and observations, but also the informants’ (and her own) bodily expressions, sensations and perceptions She took part in daily activities like cooking, eating, celebrations and ceremonies, watching Tamil TV and interacting with children. Within this approach, the researcher relied on Norwegian as the language of communication. Some Tamils spoke the language fluently, others rather poorly, and some produced close to no Norwegian. For those who spoke poorly, family members would help out in conversations, and in some instances the author arranged for an interview in which she called upon an interpreter |

The site is a small fishing village in along the arctic coast of Norway with a Tamil refugee resettlement | Bi medicine vs Holistic medicine (Ayurveda) |

| 16 | Hadwiger | 2005 | USA | Community | How acculturation is manifested in illness narratives of diabetes |

Mexican/Mexican -American adults No information on numbers |

Ethnography involving formal interviews, participant observation and case-studies |

• A network sample was recruited through previous contacts in Hispanic community • The interview guide was translated into Spanish • Two bicultural research -assistants participated as interpreters during interviews • Most interviews were conducted in informant’s home • Significant others were allowed to be present at the preference of the informant • Informed consent was obtained through a Spanish consent form |

• This particular county in Midwest USA recorded a significant rise in Spanish-speaking population within 2 years following the establishment of a new agricultural plant • Primary field work included an internship with county health department’s bilingual bicultural health educator, participation in Hispanic religious affiliations, involvement with community Latino center, informal interviews with health providers in the community, & identification of community stake-holders |

Contextual Data: • Duration lived in USA • Generational Status • Language proficiency • Acculturation Ratings: Cuellar, Arnold and Maldonado’s 2nd Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans (ARSMA-2) |

| 17 | Herrero-Arias | 2021 | Norway | Community | Norwegian healthcare system | N = 20 Southern European immigrant parents | In-depth interviews and Focus group discussions |

• Interview locations were chosen by participants (home/office) • FGD were moderated by a Spanish researcher |

• Data was collected from 3 Norwegian municipalities with both rural and urban areas with high concentration of immigrants • Participants recruited through Facebook, RHA’s personal network, attendance of gatherings organized by immigrant communities in Norway and snowball sampling |

Demography questions included: • Country of origin • Years lived in Norway |

| 18 | Hogg | 2015 | United Kingdom | Primary care | Health-visiting service for families with young children |

Purposive sampling N = 16 Pakistani immigrant mothers N = 15 Chinese immigrant mothers |

Semi-structured interviews |

• Bilingual research assistants assisted in recruitment • Interviews were conducted at participants’ homes • Interviews conducted by bilingual research assistants, or with the help of interpreters |

No information provided |

• Experience of health visiting service including cultural sensitivity • Language • Generational Status • Experience of living with extended family |

| 19 | Jager | 2019 | Netherlands | Primary care | Dietetic care in Type 2 diabetes | N = 12 diabetic adults who are immigrants from Turkey, Morocco, Iraq and Caraco; and visit a dietician | In-depth semi-structured interviews |

• Recruitment done by dieticians and researchers in practices orally and by information leaflets in different languages • Interviews held in preferred language thorough interpreters who were specially trained • Interviews conducted in participants’ home • Family present in several cases |

Recruitment was done from nine Dutch dietetic practices in areas with a high proportion of migrant residents |

• Country of origin • Length of stay in Netherlands • Explanatory model of illness by Arthur Kleinman was one of the models on which topic list was based. It addresses the social and cultural influences on illness and health |

| 20 | Janevic | 2020 | USA | Hospital | Impact of perceived racial-ethnic discrimination on patient-provider communication | N = 16 Latina women who gave birth in a large hospital and had attended prenatal care at the same hospital’s clinic | Focus group discussion |

• Participants were offered a $100 gift card for their participation • All materials were translated into Spanish • Focus group was conducted in Spanish language • Moderators were of a similar racial—ethnic background as study participants and were trained in the content of the discussion guide |

A large hospital in New York. There is no information on why this site was selected |

• Patient-provider communication during childbirth among Latina women was investigated from the perspective of Critical Race Theory (CRT). CRT focuses on the social construction of race and recognizes the pervasiveness of structural racism • The research team developed a discussion guide containing a series of questions on the women’s experiences during their birth hospitalization, communication with providers, and if they perceived differential treatment for any reason • Examples of questions include: “Was there a doctor, nurse, or other health care provider during your time in the hospital with whom you felt uncomfortable asking questions? Tell me more about this experience.”; “Can you describe any time during your care you may have felt you were treated differently from other women? Why do you think you were treated differently?” |

| 21 | Jomeen | 2013 | United Kingdom | Community | Maternity care | N = 219 women who self-identified as coming from black, ethnic minority (BME)groups in a national survey of women who had given birth in the last 3 months | Telephone interviews |

• A leaflet in a wide range of languages with a Freephone number was mailed • Women could choose to participate by telephone interview or with the help of a Languageline interpreter |

Data collected by the Office for National Statistics using birth registration records | No information provided |

| 22 | Jonkers | 2011 | Netherlands | Hospital | Ethnicity-related factors contributing to sub-standard maternity care and its effects on severe maternal morbidity among immigrant women | N = 40 immigrant women | In-depth interviews |

• Most interviews conducted at participants’ homes 2-6 weeks after discharge, in hospital for those with prolonged hospitalisation • Interpreters were offered but accepted by a single participant only • Husbands, partners, relatives and friends involved during the complication participated in almost all interviews and added their perspectives. Sometimes they also acted as interpreters |

Recruitment was done from a bigger country-wide registration study | None |

| 23 | Jun | 2018 | USA | Community | Pre-natal genetic testing and decision-making process |

Referrals and Snowball sampling N = 10 Korean-American women |

Face-to face or phone interviews |

• Research team had three bilingual, bicultural scholars • Two bilingual research-team members translated interview-guide from English to Korean and conducted interviews in Korean language • Interviews were conducted either face-to-face or by phone, depending on where participants lived • Gif-cards were provided |

• Participants initially recruited by referrals from Korean community leaders in a Midwestern urban area • Subsequently, a snowball sampling technique was used to recruit additional participants • Due to snowball sampling, participants were dispersed geographically throughout US |

• No. of years living in USA |

| 24 | Kumar | 2018 | United Kingdom | Hospital | Satisfaction towards receiving information about biologics and future support preferences for Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) |

Purposive sampling N = 27 South Asian patients with RA |

Semi-structured interviews: Face-to-face or phone | Interviews conducted in preferred language (Punjabi/Hindi/English) by multilingual researcher | Sites were secondary care rheumatology clinics at 2 large hospitals | None |

| 25 | Kwok | 2017 | Australia | Community | Influence of cultural values and language on Treatment-decision making (TDM) process in Breast cancer | N = 23 Chinese-Australian women | Focus group discussions |

• FGD conducted in native languages (Mandarin or Chinese) by first author and a trained research assistant, both registered nurses with clinical oncology experience and fluent in English, Mandarin and Cantonese • FGD conducted in premises where cancer support groups met |

Participants were recruited from a cancer support group serving the Chinese community |

• Confucian philosophy was used as a conceptual framework. It powerfully influences and behaviour of Chinese people -central concepts include deep respect for authority figures and mutual dependence within families along with responsibility for individual family members • English proficiency • Years in Australia |

| 26 | LaManusco | 2016 | USA | Community, Primary Care | Maternity care (Perinatal Care) | N = 14 Karen (Burmese) refugee women | In-depth interviews |

• All documents were in Karen language • Interviews conducted at home, alone or in pairs according to participant preferences • Interviews were conducted in Karen with help of interpreter • Participants received $20 for participating |

• Buffalo, New York, where a community of 4000 Karen refugees continues to grow • Primary care site was community health centre for Karen refugees |

• Social contextual model (SCM): there are multiple psychosocial, population, and structural/environmental factors that influence health behaviours (Interview guide based on this and lit/rv) • Interviews with Karen perinatal patients focused on experiences during pregnancy, labour, and the postpartum period in Burma, Thailand, and/or Buffalo; women’s questions about and opinions of perinatal care in Buffalo; challenges faced during the perinatal period; and Karen perinatal traditions |

| 27 | Madden | 2017 | United Kingdom | Community | Healthcare experiences to understand barriers to engagement |

Purposive Sampling, Snowball Sampling N = 42 East European immigrants (¾ Polish) |

In-depth interviews (individual and small group), Focus-group discussion |

• Adverts in Polish & English • All recruitment materials (posters and leaflets), the participant information sheets and consent forms were translated into Polish by a native speaker • Gatekeepers and participants were asked if they would like these translated into other languages when interviews and focus groups were arranged, however, this was not requested • Face-to-face interviews were conducted at place of participants’ preference (including cafes and community centres) • To encourage open and easy conversation, in only one language, focus groups were conducted with participants who already knew each other • Participants assisted each other with translation during Focus group discussion |

• A medium town in North England • Recruitment done through local Polish and East European networks, general services like social housing providers, local authority services, recruitment agencies, a drug and alcohol service and libraries |

• Nationality |

| 28 | Maneze | 2016 | Australia | Community | Communication issues in interaction with healthcare practitioner (HCP) |

Purposive & Snowball sampling N = 58 Filipino immigrant adults with at least 1 chronic disease |

Focus group discussions | Focus-group discussions moderated by bilingual researcher |

• Recruitment was carried out in the Greater Western Sydney area where the Filipino migrant population was known to be the largest • Leaders and members of Filipino community organisations were invited to participate • Participants were asked to provide contact details of the researchers to friends and family members who they felt might be interested |

• Questions focused on the facilitators and barriers to health-seeking and communication issues experienced during clinical encounters |

| 29 | Markovic | 2004 | Australia | Hospital | Gynaecological cancer disclosure and treatment decision-making | N = 11 immigrant women (Europe, Asia & Pacific, Middle-East) with gynaecological cancer | In-depth interviews, Participant Observation in cancer support group and out-patients’ dept |

• Interpreters were offered for interviews where required but women preferred family interpreter for reasons of confidentiality • Richness of women’s responses indicated their general readiness to talk openly with the assistance of a family interpreter. The use of a family interpreter provided with the opportunity to explore gate-keeping with regard to cancer disclosure practice • An interview conducted with a professional interpreter, known to the woman through community networks, again demonstrated that she was not inhibited by the presence of ‘an outsider’ |

• A tertiary, public hospital in Melbourne, Australia. There is no information on how this site was selected • Rapport established with female inpatients by visiting them on the ward and attending outpatients’ clinic when they presented for follow-up appointments, participating in a hospital-based cancer support group |

• Continent of origin |

| 30 | McKinlay | 2015 | New Zealand | Primary care | Multimorbidity (MM)healthcare in a Very Low-Cost Access (VLCA) general practice | N = 5 patients of Cambodian origin, and N = 5 patients of Samoan origin | Interviews and focus-group discussions |

• A Pacific Navigator (a role designed to enable Pacific patients and family to access health services to improve health and wellbeing) individually approached and recruited Samoan patients, and similarly, a Cambodian interpreter approached and recruited Cambodian patients • Trained interpreters each facilitated language-specific focus groups (Cambodian & Samoan) • Individual patient interviews were undertaken in the patients’ homes and focus groups at a church near the general practice which is regularly used for health promotion activities |

• VLCC general practice in Wellington which manages a complex population with high levels of deprivation and a diverse ethnic mix | None |

| 31 | McLeish | 2005 | United Kingdom | Community | Maternity care |

Convenience & snowball sampling N = 33 refugee women |

Semi-structured Interviews | Women were interviewed either at home or in a neutral location such as a refugee/asylum support group, with an interpreter where necessary |

• No information provided • Recruitment done through refugee/asylum support groups, refugee agencies, asylum accommodation providers and health professionals |

None |

| 32 | Moxey | 2016 | United Kingdom | Community | Antenatal and intrapartum care in females exposed to genital mutilation |

Purposive, Convenience and snowball sampling N = 10 Somali women who had accessed antenatal care services within past 5 years |

Semi-structured interviews |

• Interviews were conducted in a private room, offering women privacy to discuss a potentially sensitive topic • A lay female interpreter, identified and trusted by the community, was present where required • All participants received an inconvenience allowance in the form of a £10 shopping voucher at the end of the interview |

• Participants recruited from 2 community centres in Birmingham, England • This location was identified due to the large resident Somali community and high numbers of Somali women with FGM accessing ANC services locally |

• No. of years in England |

| 33 | Muscat | 2018 | Australia | Hospital | Healthcare decision- making in Renal care |

Stratified, purposive sampling to represent dominant cultural & language groups N = 35 adults of CALD background receiving in-centre haemodialysis for advanced chronic kidney disease |

Semi-structured interviews | Arabic interviews were facilitated by bilingual facilitator who was research assistant trained in qualitative methods | Four large haemodialysis units in Greater Western Sydney, Australia where 38% of population is born overseas |

Interview Guide Experience of decision-making (renal replacement therapy and other); information and decision-making preferences, and; cultural values |

| 34 | Nadeau | 2017 | Canada | Primary care | Youth Mental Health Services in a collaborative care model |

N = 5 migrant young patients (12–17 years old) who received mental health services in a collaborative setting for at least 1 year N = 5 parents of migrant young patients |

F2F Semi-structured interviews |

• Interviews with youths or parents were conducted either at the family’s home or at the local service centres (called CLSCs), according to their preference, • One parent interview was conducted in presence of an interpreter as requested • Youth and family members were offered compensation for their time (a $10 gift certificate or $20, resp) |

Study site was primary-care, community based. health and social service center in Montreal that serves a multiethnic population and has three CLSCs.. These centres offer proximity services in multiple locations (such as the CLSCs themselves, schools, or patients’ homes) | • Ethnicity |

| 35 | Nguyen | 2022 | USA | Hospital | Outpatient telemedicine |

Purposive sampling N = 15 patients speaking Cantonese or Spanish [N = 6 were Asian/Pacific Islander/other, N = 11 were Hispanic/Latino] |

Semi-structured telephone interviews |

• In order to obtain a range of experiences, English, Spanish, and Cantonese-speaking patients who were scheduled for telemedicine visits were purposively sampled • Participants were interviewed by bilingual study staff in their preferred language • Demography data was collected by trained research-assistants, 2 of whom were bilingual • Participants were reimbursed for their time up to $40 |

Three clinics—general medicine, obstetrics, and pulmonary–within the San Francisco Health Network, which is the public healthcare delivery system in the city and county of San Francisco, California, serving almost exclusively Medicaid and other uninsured/publicly-insured patients |

• Preferred language • Self-identified race and ethnicity |

| 36 | Northridge | 2017 | USA | Community | Dental Care at 2 dental school clinics |

N = 69 Dominican immigrants (50 years and older) N = 53 Puerto Rican immigrants (50 years and older) |

Focus group discussion |

• Both field recruiters were bilingual in English and Spanish and had several years of experience working with racial/ethnic minority older adults and senior center directors in upper Manhattan • Group discussions were held two locations where participants did not need to travel far from their residential neighbourhoods • All participants were offered the services of a taxi driver to pick them up at their homes or at a senior center, bring them to the focus group, and take them home afterwards. This strategy was crucial for ensuring focus group attendance, particularly for older adults with mobility problems • Groups were conducted in Spanish by senior qualitative researcher who was fluent in Spanish, along with bilingual assistant moderator |

• Senior centres in upper Manhattan were chosen rather than places where older adults receive dental care in order to obtain a sample of individuals who did not necessarily have access to, or seek, dental care • Senior centres have been identified as important “third places” (as distinct from homes or “first places” and worksites or “second places”) where older adults may be targeted for health promotion activities |

• Race/ethnicity • Primary language |

| 37 | Peters | 2019 | Netherlands | Community | Maternity Care |

Purposive sampling, Snowball sampling N = 86 immigrant women |

Interviews |

• The locations of the focus group sessions were chosen by the participants • Assistance was available for respondents with a limited Dutch language proficiency. If needed, field experts and one of the moderators were available to interpret (languages: Papiamento, Turkish, Moroccan Berber, Portuguese and Moroccan Arabic) and further explain questions asked by the moderator |

• Rotterdam is the second-largest city of the Netherlands with relatively high proportion of low educated inhabitants, with relatively high levels of unemployment, income segregation and poverty compared to other large Dutch cities • Active recruitment methods, including by ‘verbal advertising’ and through social networks. (a) peer education meetings organised by the community health workers, (b) primary schools during coffee breaks, (c) secondary schools and a community college during health(care) educational lessons(d) neighbourhood community centres |

• Ethnicity • Years living in the Netherlands • Language proficiency level • Generational level |

| 38 | Ranji | 2012 | Sweden | Hospital | Ultrasound examination in second trimester of pregnancy | 9 Farsi speaking couples (N = 18) | Semi-structured individual interviews |

• Seven interviews took place at the parent’s home and the other two interviews were held in a room at the university • All of the parents were interviewed in the Farsi language by the first author who is a native Farsi-speaking midwife • Each woman and her partner/husband were interviewed separately in order to give them freedom to speak their true feelings in confidentiality |

A University hospital with southernmost region of Sweden as its catchment area. There is no information on how the site was identified | None |

| 39 | Rose | 2015 | Australia | Community | Self-management support from GPs | N = 28 ethnically diverse diabetes patients attending group diabetes education | Group interviews | A bilingual health worker who was knowledgeable in diabetes, acting as an interpreter for the Arabic-speaking and Vietnamese-speaking groups, was present during the interviews | Three community education groups for people with type 2 diabetes located in a culturally diverse region in Sydney | None |

| 40 | Semedo | 2020 | Sweden | Primary care | Multimodal pain rehabilitation (MMR) programme | N = 7 Somali women | Semi-structured interviews, focus group discussion |

• Invitation letter was written in Swedish and Somali • All individual interviews and FGD were conducted in the meeting room at the healthcare centre where the MMR programme took place • Somali interpreter was available |

The site was a healthcare centre in Northern Sweden where a group of Somalian women underwent an MMR programme | None |

| 41 | Shaw | 2016 | Australia | Hospital | Cancer care coordination |

N = 18 immigrant patients/carers [N = 8 Chinese, N = 5 Arabic N = 5 Macedonian] |

Telephone interviews, Focus group discussion |

• A letter of invitation together with information about the study in the patient’s own language and in English was mailed to all eligible patients • Patients were also invited to have their caregiver accompany them to the focus groups • Bi-lingual researchers telephoned potential participants who indicated an interest in the study after the mail-out to provide further study information • Participants were given the option of either a focus group or an interview • Written consent was obtained in patient’s own language • Researchers fluent in Cantonese, Mandarin, Arabic or Macedonian conducted interviews & FGDs • Bi-lingual researchers were experienced in health research, group facilitation and/or local community support group facilitation. They received training for the study and were supported by more experienced qualitative researchers who attended the focus groups and reviewed the interviews • Travel and associated costs of participation were covered • FGDs were conducted at a community library close to the hospitals, as this location was convenient for participants |