Abstract

Background:

This study evaluates the dementia care system in a local area and aimed to include all specialised services designed to provide health and social services to people with dementia or age-related cognitive impairment, as well as general services with a high or very high proportion of clients with dementia.

Methods:

The study used an internationally standardised service classification instrument called Description and Evaluation of Services and DirectoriEs for Long Term Care (DESDE-LTC) to identify and describe all services providing care to people with dementia in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT).

Results:

A total of 47 service providers were eligible for inclusion. Basic information about the services was collected from their websites, and further information was obtained through interviews with the service providers. Of the 107 services offered by the 47 eligible providers, 27% (n = 29) were specialised services and 73% (n = 78) were general services. Most of the services were residential or outpatient, with a target population mostly of people aged 65 or older, and 50 years or older in the case of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. There were government supports available for most types of care through various programmes.

Conclusions:

Dementia care in the ACT relies heavily on general services. More widespread use of standardised methods of service classification in dementia will facilitate comparison with other local areas, allow for monitoring of changes over time, permit comparison with services provided for other health conditions and support evidence-informed local planning.

Keywords: DESDE-LTC, dementia, health care system, service mapping, atlas of care

Introduction

Dementia is a significant health and aged care concern, with a substantial impact on the quality of life not just of those with dementia, but also their families and friends. Consequently, care providers play a crucial role in supporting patients and carers as the condition progresses. These services include a whole array of community-based settings, professionals and workers for individuals living at home, residential services for those requiring permanent care or short-term respite stays, and hospital services for those who need acute or subacute care. The types of services and professionals increases every year and now include short-term support worker, ongoing support worker, centre-based support, primary care management, specialist dementia clinics or home hospital care.1,2

In Australia, the expenses directly linked to the diagnosis, treatment, and care of individuals with dementia amounted to nearly $3.0 billion in health and aged care spending during 2018 to 19. Residential aged care services constituted the highest proportion of expenditure, accounting for 56% or $1.7 billion, trailed by community-based aged care services at 20% or $596 million, and hospital services at 13% or $383 million. 3 It’s notable that about 30% of individuals diagnosed with dementia reside in care accommodation. 3

Understanding service availability, capacity, gap analysis and analysis of unmet needs are crucial for supporting evidence-informed planning, prioritisation, and resource allocation/ expenditure within healthcare systems. Several international organisations have called for an integrated model of healthcare: one which includes specific interventions for different disorders and which also includes a complex array of service provision, such as homecare, community, hospital, and other residential settings. 4 The World Health Organization’s One Health model emphasises a holistic and collaborative approach to programmes, policies, legislation, and research; and the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing 2021-2030, and the WHO Framework for countries to achieve an integrated continuum of long-term care recommended that service provision should be person centred, multidisciplinary, accessible and affordable and ‘integrated and coordinated at all levels, from policymaking to workforce training, service delivery, and information systems, across public and private sectors, and health and social care systems’.5,6 In theory, these frameworks and recommendations should integrate the healthcare and social elements of long-term care provision, particularly for people with dementia, to boost efficient and equitable care provision. 7 However, this goal is confronted with significant challenges. Whilst there are international standards for the evaluation of care utilisation and quality (eg, InterRAI 8 ), the information on the actual care provision (services and settings) is mostly limited to narratives of good care examples and have often failed to provide standard comparisons across jurisdictions and over time useful for health planning.6,9,10 The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) report on international comparison of dementia care concluded that settings for dementia care come from a wide variety of sources, including social care as well as specific and non-specific services for dementia and the analysis of its care coordination is an issue that ‘is not an easy one to resolve’. 11 Differences in organisational structure and services as the differences in service provision for different target groups such as aged population, persons with mild cognitive impairment, persons after diagnosis of dementia and persons with Alzheimer disease or other specific conditions or comorbidities contribute to this challenge.

In addition, standard service assessment is confronted with serious methodological limitations in dementia care. Currently available classification systems of health providers, such as the System of Health Accounts (SHA 2.0), do not provide an ontology-based and comprehensive picture of local care provision. 12 This classification excludes sectors such as social services and demonstrates ambiguous terminology when classifying care providers (organisations and as professionals), care functions, and care interventions. Additionally, the routine practice of translating top-down national indicators to local evaluation and planning could be highly misleading due to the ‘ecological fallacy’, (ie, incorrect assumptions about a local area based on aggregate data on services, beds, and professionals relating to the whole country). 13 Hence, a standard assessment and coding system and a common method of data gathering is urgently needed for the harmonisation of service data, that could inform equitable allocation of care resources, programmes, and treatment across different jurisdictions and countries. 14 In addition, all health system approaches require the broader perspective of health care ecosystem analysis, which also takes into account the local social determinants of care, the natural and build environment, and the spatial–temporal variation across regions in the patterns of care and related impacts.15,16 Understanding the complex intersection of contextual factors is fundamental to implementation, provision, modelling, and improvement of services. 17

These issues in the analysis of service provision in local systems can be addressed using Integrated Atlases of Health based on an innovative service classification instrument called the Description and Evaluation of Services and DirectoriEs for Long Term Care (DESDE-LTC).18,19 The integrated Atlases of Health collect detailed local information from local service managers in a ‘bottom-up’ approach, and use Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to map the local socioeconomic and demographic context and geolocate service distribution. Following the approach previously used to map local provision in mental health,14,20 multiple sclerosis, 21 and chronic care. 22 An Integrated Atlas of Dementia Services could provide essential information on service availability, care capacity, social and demographic characteristics, and health-related needs, allowing policy planners and decision-makers to assess the strengths and gaps in the healthcare system and make informed decisions. 14

This study aims to utilise DESDE-LTC to fill the knowledge gap by demonstrating the practicality of a standardised approach to assess the service delivery system for dementia in a specific region: the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). Eventually, this approach could be implemented globally, as already done for mental healthcare. 23

Methods

This is a collective case study of the typology and characteristics of care for dementia in the ACT region. Collective case studies in healthcare analyse multiple individual cases or instances that share common characteristics or themes (in this case care organisations, beds and places and professionals providing dementia care in the ACT region). These entities are examined collectively to gain a comprehensive understanding of the broader issue at hand, exploring similarities, differences, and patterns of care provision to gain insights that can inform healthcare policies and quality improvement.24,25 This type of study design is especially useful in the analysis of complex systems in specific context conditions. 26

Study area

The ACT, a federal district of Australia covering an area of 2300 km2, had an estimated resident population of 445 110 individuals as of the 2022 census. Canberra, the territory’s sole city and the national capital, is home to roughly 90% of the ACT population. Of this population, approximately 30% are aged 50 years or older, and 14% are 65 years or older, resulting in an ageing index of approximately 66. 27 Furthermore, about 14% of those aged 65 and above have a profound or severe disability and reside in the community. 27 In the study area, there are about 48 aged care residential facilities (beds) per 1000 people aged 65 and over. 28

Inclusion criteria

The analysis included all services that offer direct care or support to individuals with dementia within the ACT boundaries. This includes specialised services that only provide care to people with dementia, and generalised aged care services that provide general services to older people including people with dementia. However, only those general services where more than 50% of clients (here termed ‘general-50’) and those where between 20% and 50% (here termed ‘general-20’) of clients are people with dementia were included in this study. It’s essential to clarify that the differentiation between specialised and ‘general-50’ and ‘general-20’ services is primarily based on the fact that specialised services exclusively serve individuals living with dementia. For example, there are residential facilities (nursing homes) that exclusively provide care to people with dementia, whereas there are others that cater to both clients with and without dementia. The former is categorised as specialised, and the latter as general-50 or 20, depending on the ratio of people with dementia. Nevertheless, general services with less than 20% of clients affected by dementia are not included. Despite contributing to the overall service capacity for individuals with dementia, the distinct nature of their services and the expertise of their team members warrant a separate evaluation, akin to the general atlas of social and health services.

This consideration encompassed all services, whether publicly or privately funded services. Additionally, services providing information and coordination to aid people with dementia or their caregivers to manage their illness were included, as long as they were stable in both temporal and administrative terms.

Instrument

The DESDE-LTC was the tool utilised to gather and evaluate the data. It is an internationally standardised instrument that has been validated in 6 different European countries from both the Western and Eastern regions. 19 The purpose of this tool is to describe and classify services across different sectors, enabling valid comparisons to be made between local areas and countries, despite differences in levels of care, units of analysis, and terminology.23,29,30 It uses a conceptual model based on a healthcare ecosystems research approach that takes a whole systems approach to healthcare, aiming to facilitate analysis of the complex environment and context of health systems and the translation of this knowledge into policy and practice. 18

The DESDE-LTC categorises and codes services that provide care or support based on 4 different axes, including target population, sector of care, the main type of care, and workforce. It provides a taxonomy of care types based on various criteria such as service acuity, mobility, availability to the service user, and whether it is health-related or not. This allows an accurate and meaningful comparison to be made with other regions. Each team providing care within an organisation is identified as a basic stable service team, and the main type of care (MTC) delivered by each service team is described according to 6 main branches of the taxonomy: (1) residential care, (2) day care, (3) outpatient care, (4) accessibility of care, (5) guidance with 2 sub-branches of information and evaluation, and (6) self-help and volunteer care. This standardised approach provides a highly granular and multiaxial final code that describes the care provided by a service team, and allows for an accurate comparison with other regions. For more details, refer to Appendix S1, and the eDESDE-LTC website (http://www.edesdeproject.eu).

Data collection

The following steps were taken for data collection:

Eligible services were identified through an initial search that involved scanning online, telephone and official directories for relevant services. Consultation was also made with experts in the field.

Information necessary for the description and classification of services, such as location, administration, temporal stability, governance, and financing mechanisms, was manually extracted from the webpages of identified service providers.

Relevant organisations were contacted directly to arrange interviews with their representatives to obtain details of services provided to people living with dementia.

Representatives from each identified organisation were interviewed using the DESDE-LTC service inventory questionnaire (Appendix S1) to collect data.

Service coding and analysis

Services identified through the above processes that met the inclusion criteria were given a DESDE-LTC code. Services which were eligible but not interviewed for any reason have been coded based on publicly available information on their website and characteristics in comparison to similar services in the same area. The analysis involved describing the number of service teams and their MTC, which were then evaluated based on their availability per 100 000 adult population in the study area. To display the distribution of the different MTCs and to show the combination of service types (ie, pattern of care) in the area, radar plots were used. Each point on the 24 radii of a radar plot represents the number of a particular MTC per 100 000 adult population in the study area.

Ethics approval for this study was granted by an institution Health Human Research Ethics Committee.

Results

General overview of MTC

A total of 71 service providers were initially identified as potential candidates for the study. However, 24 of them were excluded as fewer than 20% of their clients had dementia or age-related cognitive impairment based on information gathered from their websites or from direct communication with them. Therefore, there were 47 eligible service providers included in this study.

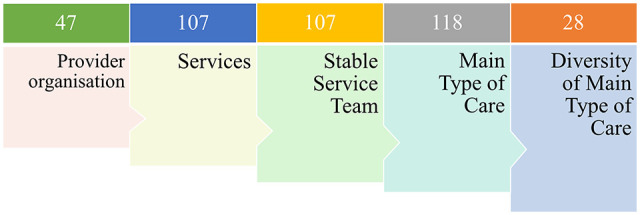

For additional information, service providers were contacted to arrange an online or in-person interview (conducted from December 2021 to January 2023). However, reaching out to some of services providers for interview were not successful due to the strain on the aged care workforce related to COVID-19. Therefore, the coding of these services was based solely on the information available publicly on their websites. A total of 107 services were provided by 107 stable service teams from the included 47 service providers. These teams delivered 118 MTCs. Twenty-eight different MTC codes were applied across these 118 main types of care (Figure 1). Of the 107 services, 62 services were coded based on face-to-face or online interviews and 45 services coded based on the information on their websites. Of the organisations not interviewed, 3 were not contactable, 2 did not agree to an interview, and the rest did not proceed with the interview request. Only 24 of the 107 services reported information about workforce capacity, making it impossible to provide an analysis of the workforce capacity of the dementia care system in the ACT (Supplemental Tables 1–3).

Figure 1.

Summary of services providing dementia care in the Australian Capital Territory region 2022.

Specialised versus general services

Overall, the contribution of general aged care services was higher than specialised care services in care provision for people with dementia/age-related cognitive impairment. However, in some categories of care, such as health-related day care services, self-help and volunteer care, and accessibility to care, there was a lack of services in both specialised and general aged care services (Table 1).

Table 1.

The number of main types of care (and beds for residential cares) in specialised and general services provided to people with dementia in ACT across different categories of care based on DESDE classification.

| Type of services | Specialised | General-50 | General-20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential care * | |||

| Hospital care with 24 h physician cover | 0 | 1 (52) | 0 |

| Non-hospital indefinite stays without 24 h physician cover | 15 (274 + ) | 10 (689) | 16 (1583) |

| Non-hospital limited stays without 24 h physician cover | 3 (19 + ) | 4 (9 + ) | 4 (21 ++ ) |

| Day care | |||

| Day care with structure | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Day care without structure (eg, social club) | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Outpatient care | |||

| Outpatient care at home | 5 | 5 | 17 |

| Outpatient care at centre | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Accessibility to care | |||

| Case finding, communication, physical mobility, and personal accompaniment | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Case coordination | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Other accessibility care | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Evaluation | |||

| Acute or one episode assessment | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Continuous assessment | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Information | |||

| Code void | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Interactive and non-interactive information | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Self-help and volunteer care | |||

| Any form | 0 | 0 | 0 |

General-50; general services that more than 50% of their clients are people with dementia, General-20; general services that more than 20% up to 50% of their clients are people with dementia.

Number of services and in bracket the total number of beds.

Number of beds from one service is not available.

Number of beds from 2 services is not available.

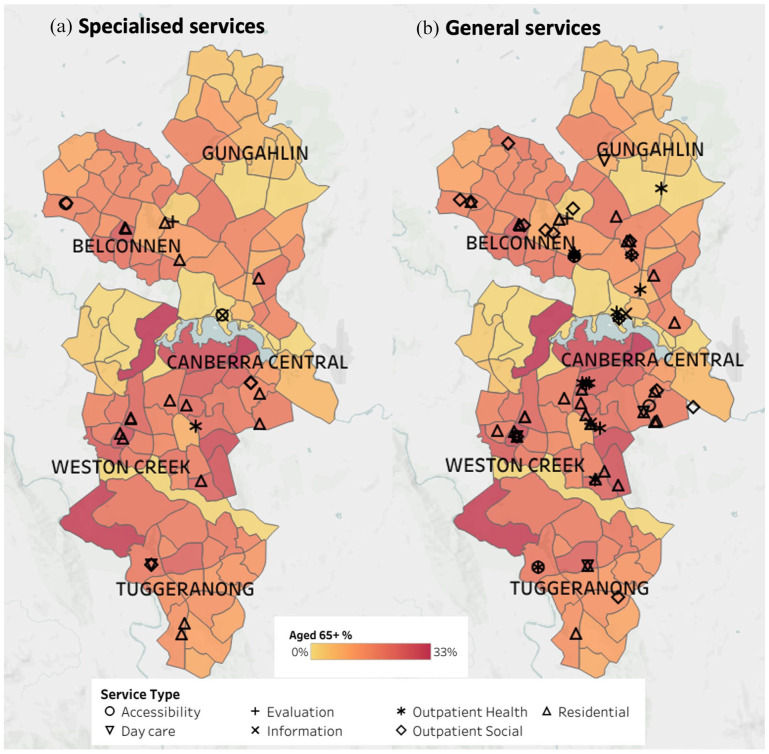

A total of 29 specialised service teams from 16 service providers offered 30 MTCs (across 13 different types of care) for individuals with dementia (Supplemental Table 1). The number of general services was higher than that of specialised services, with 27 general-50 service teams from 17 service providers offering 31 main types of care (Supplemental Table 2), and 51 general-20 service teams from 35 service providers offering 56 main types of care (Supplemental Table 3). Figure 2 shows the location of the specialised (A) and general (B) services. As the figure indicates, the majority of services are situated in the southern part of the city. Specifically, access to specialised non-residential care is significantly limited in the northern part of the city.

Figure 2.

The of services providing dementia care in the Australian Capital Territory region 2022: (A) specialised services, (B) general services.

In the category of specialised care, residential care was the most common type of care, providing 18 of the 30 main types of care, followed by outpatient care, which had 7 types of care (Table 1, Supplemental Table 1). Day care, accessibility to care, information care, and evaluation each had 1 or 2 services, and there were no specialised self-help or volunteer services available.

In the category of general-50 services, in which at least 50% of clients had dementia or age-related cognitive problems, residential and outpatient care were also the most common types of care, providing 15 and 8 of the 32 types of care, respectively (Table 1, Supplemental Table 2). Evaluation services were more prevalent in general than specialised services, with 5 of the 32 general-50 MTCs dedicated to evaluation. Three day-care services were available, but there were no accessibility to care, information services, or self-help and volunteer care services.

The diversity of types of care available (16 different types of care) was greater in general-20 services (those services supporting between 20% and 50% of clients with dementia or age-related cognitive problems) than that in general-50 services (11 different types of care). Outpatient care was the most common type of care, providing 26 of the 55 available types of care, followed by residential care, with 21 types of care. Day care, accessibility to care, and information services were also available, with 4, 3, and 2 services, respectively, but there were no evaluation or self-help and volunteer services available in this category (Table 1, Supplemental Table 3).

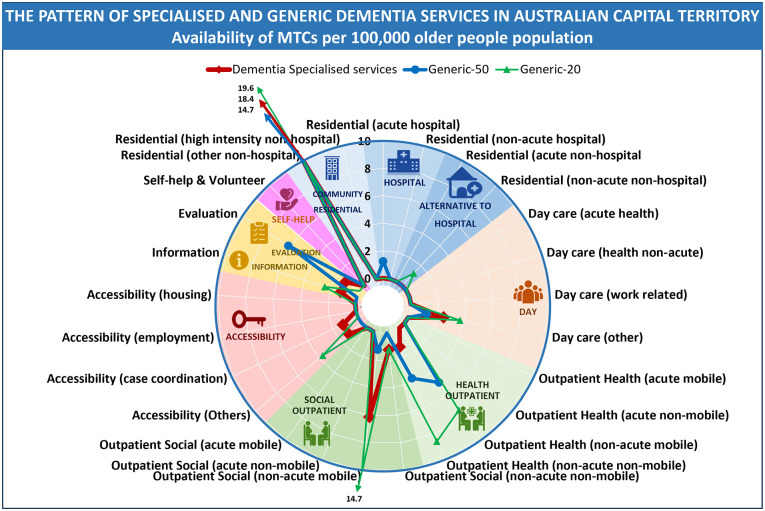

To illustrate the pattern of service types offered in the region, a radar tool was used to create a visual pattern of care. Figure 3 compared the patterns of specialised and general care in terms of the number of MTCs per 100 000 of the population in the ACT region in 2022. The brown line represents the pattern of specialised services, the blue line represents general-50 services, and the grey line represents general-20 services. The figure shows that the patterns of service types were similar across specialised and general services, but the capacity of services per 100 000 population was higher in general-20 services than in general-50 and specialised services for most types of care. Community residential services (ie, nursing homes) were the dominant service in all 3 categories.

Figure 3.

Availability of specialised dementia services (brown) and general-50 services (blue) and general-20 services (grey) MTCs per 100 000 adult population.

Capacity and the gap in the system

To identify the gap in dementia services, a content analysis 31 of the views and perceptions of 29 participants was conducted (to be reported separately). Briefly, participants identified several gaps in dementia services in the ACT region: a lack of dementia-specific services, poor quality of existing dementia care due to inadequate staff training, insufficient funding for dementia services, and poor public awareness of dementia leading to stigma and reluctance to access services.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first analysis of the regional case provision for dementia following a whole system approach and a validated coding tool. The collective case study approach allows in-depth, multi-faceted explorations of complex issues in their real-life settings. The value of the case study approach is well recognised in the fields of business, law and policy, but somewhat less so in health services research. This study aimed to provide a standardised systematic description of the availability, capacity, and diversity of dementia care services within a specified local area, the ACT, with a perspective of beginning a global process. The study encompassed both specialised health and social care, as well as general services that support a considerable number of clients with dementia or age-related cognitive decline. The findings revealed that specialised services are limited compared with general services. However, the diversity of types of care available is only slightly less in specialised than in general services.

Only a quarter of the available services for people with dementia were provided by specialised services. The remaining care was furnished by general services not tailored specifically to dementia care even though sometimes up to 80% of their clients are living with cognitive difficulties. Moreover, only a limited number of specialised services offered tailored care to individuals with dementia, considering the varying degrees of cognitive challenges and the severity of the condition. This is significant as people experiencing dementia demonstrate a range of cognitive difficulties, varying in severity, which directly influences the type and extent of care needed. It’s imperative for healthcare systems to prioritise care that meets the diverse needs of individuals with dementia, aligning with the severity of their conditions.

Special training is necessary when working with people who live with dementia.32,33 Training standards should be tailored to the needs of the consumer, worker, and regions. 34 Despite this, even specialised services may lack staff trained to care for people with dementia. These services are designed to cater to people with special needs, but their staff may not be specifically trained to provide dementia care. They are mainly designed to provide a suitable environment rather than specialised staff. However, this does not necessarily imply that the staff providing care are unqualified, and, in fact, some may be overqualified for their positions 35 For instance, a registered nurse may serve as a coordinator in an accessibility to care service, a role that may not require their level of expertise. 36 Unfortunately, only a small proportion of available services provided information about their workforce capacity, leading to an incomplete and imprecise picture of the entire system.

Dementia is a chronic condition, the provision of care for which requires an integrated, person-centred approach, as advised by the World Health Organization. 6 To achieve this, greater multidisciplinary involvement and a shift towards community-based services is necessary, as recognised in the Australian healthcare system.1,37 Indeed, the majority (about 75%) of people with dementia live in the community instead of moving to residential aged care. They mainly rely on informal care provided by their family members or friends to be able to remain living at home.38,39 The present study shows the availability of a relatively diverse range of services for people living with dementia, including community services. Additionally, there is a relatively similar pattern of care in both specialised and general services. Residential care, mainly in nursing homes, is the most prevalent, followed by outpatient care, including home care. Although day care, information and evaluation care, and access to care services are available, the availability of day care is limited compared to residential and outpatient care. When compared to mental health services for older adults and for people aged 18 years and above, dementia services demonstrate greater variation in the type of services provided.20,40 There are services available in 6 of the 7 categories of care, (although limited in some categories) for people living with dementia, while mental health services for older people and adults with mental health issues are limited to hospital and outpatient care.

This variation in service provision may be attributed to the superior financial support of the aged care system compared to the mental health system in Australia. Individuals with dementia receive government-subsidised support via the Aged Care System for both residential and community services. The Australian National Aged Care Classification (AN-ACC) provides a general aged care home subsidy for all aged care residents, and the Specialist Dementia Care Program (SDCP) caters to individuals with severe dementia symptoms. Community services are supported through the Home Care Package (HCP) and the Commonwealth Home Support Program (CHSP), as well as the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) for individuals under the age of 65. At the same time there is no specific governmental support for mental health issue for older people. Since the NDIS also supports mental health services for people less than65 years old the diversity of mental health services for people between 18 and 65 years old is better than that for mental health services for older people.

It is important to note that accessing dementia services in this study was considerably more challenging than accessing mental health services in the ACT. 41 There was no direct contact with manager level staff available for other service providers, researchers, or policy makers. Compared to that for mental health services, response rates to our interview requests were lower. Forty two percent of aged care providers did not respond or were not available for an interview compared to less than 10% non-respondents in mental healthcare sector in the same study area. 41 Non-respondent organisations have been coded based on the information publicly available on their websites considering the coding of similar services in the same local area.

Moreover, organisations often failed to provide supplementary information, such as workforce capacity data, in response to our follow-up inquiries, with response rates lower than those from mental health service providers. 42 Overall, service providers commonly offered website information alongside phone or email contact options for additional inquiries. However, they typically supplied a national number or email for all inquiries. This approach proved inconvenient for us and might not be user-friendly, especially for older individuals. National numbers posed challenges as respondents were often unfamiliar with local facilities. Emails, on the other hand, either garnered no response or, when received, lacked helpful information due to respondents’ limited knowledge.

An effective approach to caring for individuals with chronic conditions must encompass both healthcare and social services. 43 People living with dementia may have significant non-medical social needs that impact their health and quality of life, and these should be considered when developing individual management plans. 44 However, the integration of social services into healthcare can be challenging due to the financial incentives that prioritise health-related services. As a result, there is little motivation for health systems to develop comprehensive care systems that incorporate social services. 44

This assessment of dementia care is unique and unprecedented, with no comparable data available worldwide, including Australia. Although there is a noticeable variation among services in the ACT, service providers have identified some shortcomings in the system. It is uncertain whether these issues are specific to ACT, are prevalent throughout Australia, or are common worldwide due to the nature of service provision in this field. This may become evident if other regions in Australia and worldwide undergo similar evaluations, potentially revealing a nationwide concern.

One of the notable strengths of this study is its use of a consistent and uniform depiction of the regional service delivery system, taking into account all aspects. Standardised descriptions of this nature are crucial in ensuring clarity, facilitating planning, resource allocation, and guiding future service delivery, as previously demonstrated in mental health care. 45 It is important to note that this study solely focuses on the availability of care for individuals with dementia and does not address the entire aged care system. We have included only specialised services and general services that cater to clients with dementia or age-related cognitive challenges affecting at least 20% of their clientele. Our previous research on care provision for various conditions such as mental health, chronic care, Multiple Sclerosis, and disabilities indicates the importance of a separate analysis of specialised services and those general services that also cater to the target population.21,22,40 In the case of dementia, we have identified a significant proportion of general services with a substantial case load of people with dementia. This finding prompted us to include general services with over 50% and those with over 20% case load of dementia. The number of services falling into these categories highlights a major problem in the capacity of specialised care in this area. While general services with less than 20% of clients having dementia still contribute to the overall capacity for individuals living with dementia, it is crucial to note that, due to differences in the nature of services and the expertise of service team members, a separate evaluation for general services is warranted.

The current study has certain limitations. Firstly, the evaluation was restricted to specialised and general services that have a significant number of clients with cognitive impairments. The categorisation of services into specialised and general was based on their focus on individuals with dementia or on older adults, but the study lacks information on the level of workforce training in each group, as well as workforce details. Additionally, it is important to acknowledge that dementia is just one of several conditions that aged care services cater to. As a result, there may be competition for limited resources, but implementing tools like the DESDE-LTC can inform a fair allocation of resources. The DESDE-LTC was initially validated for chronic care coding in 6 Western and Eastern European countries and outperforms other global service assessment tools in terms of validation extent and psychometric depth. 46 Extending its validation to other parts of the world would be advantageous. The study’s methodology is replicable, allowing for follow-up assessments over time to track the impact of plans and changes, 47 such as the introduction of new services, particularly in tandem with evaluations of health-related quality of life and satisfaction with care provided to individuals with dementia.

As this study was the first to employ the DESDE method in evaluating the dementia care system, it introduced a novel experience. Among the most challenging aspects was accessing managers of organisations and arranging interviews, especially with residential facilities. Given that a substantial portion of dementia care is subsidised by local and national governments, many organisations had already reached their capacity. Consequently, they might have lacked the motivation to respond to or request interviews. This contrasted with our previous studies on mental health care, where organisations showed more enthusiasm, foreseeing potential benefits in terms of publicity.

Additionally, identification of the services was another challenge because most of the services were not available in national and local directories. This issue was also less problematic in other fields. Last but not least, the entire system designed for aged care, and indeed for people with dementia, needed to be utilised. Therefore, the number of services specifically designed for people with dementia was limited, and we had to include those with a high rate of clients with dementia, an issue which is not the case in mental health services.

Conclusions

Although governmental supports facilitated a variety of dementia care services in the ACT, the care system primarily relies on non-specialised aged care services. This lack of specialised services is especially evident in day care and respite care. Therefore, it is essential to establish further specialised services, specifically those currently absent to aid patients in living independently at home. Providing policy and service decision makers with the necessary tools and opportunities to make informed decisions regarding future planning and investments in dementia care is critical. This study has demonstrated the evaluation of dementia care in a local health system and serves as a resource for assessing how services will evolve over time, and whether the changes will result in improved care levels in areas of need identified locally.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-his-10.1177_11786329241232254 for The Integrated Atlas of Dementia Care in the Australian Capital Territory: A Collective Case Study of Local Service Provision by Hossein Tabatabaei-Jafari, Mary Anne Furst, Nasser Bagheri, Nathan M. D’Cunha, Kasia Bail, Perminder S. Sachdev and Luis Salvador-Carulla in Health Services Insights

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-his-10.1177_11786329241232254 for The Integrated Atlas of Dementia Care in the Australian Capital Territory: A Collective Case Study of Local Service Provision by Hossein Tabatabaei-Jafari, Mary Anne Furst, Nasser Bagheri, Nathan M. D’Cunha, Kasia Bail, Perminder S. Sachdev and Luis Salvador-Carulla in Health Services Insights

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Ms. Nicole O’Connor for her invaluable administrative support in this study and to Ms. Secil Yanik for her assistance in preparing the visual materials. Additionally, the authors wish to specially thank service providers, who participated in the project and provided invaluable comments regarding the dementia care in ACT.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Australian Dementia Network (ADNet) and the Centre for Healthy Brain Ageing (CHeBA), University of New South Wales Sydney, in partnership with University of Canberra.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: H. T-J. co-planned the study, interviewed participants, Coded the services, conducted the data analysis, and wrote the paper. M. F. supervised the coding and contributed to revising the paper. N. B., K. B. and P. S. S. helped to plan the study and to revise the manuscript. N. D. interviewed participants and revised the manuscript. L. S-C. co-planned the study, supervised the coding and revised the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Ethics approval for this study was granted by an institution Health Human Research Ethics Committee.

ORCID iDs: Hossein Tabatabaei-Jafari  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4871-1226

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4871-1226

Mary Anne Furst  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1906-2346

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1906-2346

Nathan M. D’Cunha  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4616-9931

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4616-9931

Kasia Bail  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4797-0042

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4797-0042

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Low LF, Gresham M, Phillipson L. Further development needed: models of post-diagnostic support for people with dementia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2023;36:104-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pouw MA, Calf AH, van Munster BC, et al. Hospital at home care for older patients with cognitive impairment: a protocol for a randomised controlled feasibility trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e020332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. AIHW. Dementia in Australia. 2022. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/dementia/dementia-in-aus/contents/summary#Common

- 4. World Health Organization. Integrated Care Models: An Overview. World Health Organisation; 2016. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://who-sandbox.squiz.cloud/en/health-topics/Health-systems/health-services-delivery/publications/2016/integrated-care-models-an-overview-2016 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Banerjee A, Jang H. Framework for Countries to Achieve an Integrated Continuum of Long-Term Care. World Health Organisation; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gauthier S, Webster C, Servaes S, Morais JA, Rosa-Neto P. Life After Diagnosis: Navigating Treatment, Care and Support. Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stansfield J, South J, Mapplethorpe T. What are the elements of a whole system approach to community-centred public health? A qualitative study with public health leaders in England’s local authority areas. BMJ. 2020;10:e036044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Almeida Mello J, Wellens NI, Hermans K, et al. The implementation of integrated health information systems - research studies from 7 countries involving the InterRAI assessment system. Int J Integr Care. 2023;23:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johri M, Beland F, Bergman H. International experiments in integrated care for the elderly: a synthesis of the evidence. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:222-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organisation. ATLAS Country Resources for Neurological Disorders. World Health Organisation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moïse P, Schwarzinger M, Um M-Y. Dementia Care in 9 OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis. OECD Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12. OECD. Classification of Health Care Providers (ICHA-HP). OECD; 2017. doi: 10.1787/9789264270985-8-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Whyatt D, Tenneti R, Marsh J, et al. The ecological fallacy of the role of age in chronic disease and hospital demand. Med Care. 2014;52:891-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salvador-Carulla L, Romero C, Weber G, et al. Classification, assessment and comparison of European LTC services. Development of an integrated system. Eurohealth. 2011;17:27-29. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dwyer-Lindgren L, Bertozzi-Villa A, Stubbs RW, et al. Trends and patterns of geographic variation in mortality from substance use disorders and intentional injuries among US counties, 1980-2014. JAMA. 2018;319:1013-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Snijder M, Calabria B, Dobbins T, Knight A, Shakeshaft A. A need for tailored programs and policies to reduce rates of alcohol-related crimes for vulnerable communities and young people: an analysis of routinely collected police data. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53:578-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davidoff F. Understanding contexts: how explanatory theories can help. J Implement Sci. 2019;14:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Furst MA, Bagheri N, Salvador-Carulla L. An ecosystems approach to mental health services research. BJPsych Int. 2021;18:23-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Salvador-Carulla L, Alvarez-Galvez J, Romero C, et al. Evaluation of an integrated system for classification, assessment and comparison of services for long-term care in Europe: the eDESDE-LTC study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Furst MA, Salinas-Perez J, Bagheri N, Salvador-Carulla L. 2020 Integrated Atlas of Mental Health Care in the Australian Capital Territory. Centre for Mental Health Research, Australian National University; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tabatabaei-Jafari H, Bagheri N, Lueck C, et al. Standardized systematic description of provision of care for multiple sclerosis at a local level: a demonstration study. Int J MS Care. 2023;25:124-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mendoza J, Bell T, Hopkins J, et al. Integrated Chronic Care Atlas of Dubbo and Coonamble. 2017. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.canberra.edu.au/content/dam/uc/documents/research/hri/atlas-of-health-and-social-care/nsw/The-Integrated-Mental-Health-Atlas-of-Western-NSW.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23. Romero-López-Alberca C, Gutiérrez-Colosía MR, Salinas-Pérez JA, et al. Standardised description of health and social care: A systematic review of use of the ESMS/DESDE (European Service Mapping Schedule/description and evaluation of services and DirectoriEs). Eur Psychiatry. 2019;61:97-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, et al. The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Paparini S, Green J, Papoutsi C, et al. Case study research for better evaluations of complex interventions: rationale and challenges. BMC Med. 2020;18:301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paparini S, Papoutsi C, Murdoch J, et al. Evaluating complex interventions in context: systematic, meta-narrative review of case study approaches. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21:225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population: Census. 2021. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/population-census/2021

- 28. Public Health Information Development Unit (PHIDU). Social Health Atlases of Australia. 2019. http://phidu.torrens.edu.au/social-health-atlases/data

- 29. Ala-Nikkola T, Pirkola S, Kaila M, et al. Identifying local and centralized mental health Services-The development of a new categorizing variable. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gutiérrez-Colosía MR, Salvador-Carulla L, Salinas-Pérez JA, et al. Standard comparison of local mental health care systems in eight European countries. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;28:210-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brodaty H, Draper B, Low L. Nursing home staff attitudes towards residents with dementia: strain and satisfaction with work. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44:583-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hazelhof TJ, Schoonhoven L, van Gaal BG, Koopmans RT, Gerritsen DL. Nursing staff stress from challenging behaviour of residents with dementia: a concept analysis. Int Nurs Rev. 2016;63:507-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pit SW, Horstmanshof L, Moehead A, et al. International standards for dementia workforce education and training: a scoping review. Gerontologist. 2024;64:1-15. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnad023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lukersmith S, Salvador-Carulla L, Chung Y, et al. A realist evaluation of case management models for people with complex health conditions using novel methods and tools-what works, for whom, and under what circumstances? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:4362. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20054362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brown P, Burton A, Ayden J, et al. Specialist dementia nursing models and impacts: a systematic review. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2023;36:376-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lukersmith S, Salvador-Carulla L, Sturmberg J, et al. Expert commentary: What is the State of the Art in Person-centred care? 2016. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344292950_Expert_Commentary_What_is_the_State_of_the_Art_in_Person-_centred_Care?channel=doi&linkId=5f63f8ff458515b7cf3bf499&showFulltext=true [Google Scholar]

- 38. Engel L, Loxton A, Bucholc J, et al. Providing informal care to a person living with dementia: the experiences of informal carers in Australia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;102:104742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Michalowsky B, Thyrian JR, Eichler T, et al. Economic analysis of formal care, informal care, and productivity losses in primary care patients who screened positive for dementia in Germany. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;50:47-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tabatabaei-Jafari H, Salinas-Perez JA, Furst MA, et al. Patterns of service provision in older people's mental health care in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:8516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Furst MAC, Salinas-Perez JA, Salvador-Carulla L. The Integrated Mental Health Atlas of the Australian Capital Territory Primary Health Network Region. 2018. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.18766.97606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Furst MA, Salinas-Perez JA, Gutiérrez-Colosia MR, Salvador-Carulla L. A new bottom-up method for the standard analysis and comparison of workforce capacity in mental healthcare planning: Demonstration study in the Australian Capital Territory. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0255350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Desborough J, Brunoro C, Parkinson A, et al. It struck at the heart of who I thought I was': A meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature examining the experiences of people with multiple sclerosis. Health Expect. 2020;23:1007-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Feinglass J, Norman G, Golden RL, et al. Integrating social services and home-based primary care for high-risk patients. Popul Health Manag. 2018;21:96-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Castelpietra G, Simon J, Gutiérrez-Colosía MR, Rosenberg S, Salvador-Carulla L. Disambiguation of psychotherapy: a search for meaning. Br J Psychiatry. 2021;219:532-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Furst MA, Gandré C, Romero López-Alberca C, Salvador-Carulla L. Healthcare ecosystems research in mental health: a scoping review of methods to describe the context of local care delivery. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fernandez A, Salinas-Perez JA, Gutierrez-Colosia MR, et al. Use of an integrated atlas of mental health care for evidence informed policy in Catalonia (Spain). Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2015;24:512-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-his-10.1177_11786329241232254 for The Integrated Atlas of Dementia Care in the Australian Capital Territory: A Collective Case Study of Local Service Provision by Hossein Tabatabaei-Jafari, Mary Anne Furst, Nasser Bagheri, Nathan M. D’Cunha, Kasia Bail, Perminder S. Sachdev and Luis Salvador-Carulla in Health Services Insights

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-his-10.1177_11786329241232254 for The Integrated Atlas of Dementia Care in the Australian Capital Territory: A Collective Case Study of Local Service Provision by Hossein Tabatabaei-Jafari, Mary Anne Furst, Nasser Bagheri, Nathan M. D’Cunha, Kasia Bail, Perminder S. Sachdev and Luis Salvador-Carulla in Health Services Insights