Abstract

Nonopsonic phagocytosis of Bacillus cereus by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) with particular attention to bacterial surface properties and structure was studied. Two reference strains (ATCC 14579T and ATCC 4342) and two clinical isolates (OH599 and OH600) from periodontal and endodontic infections were assessed for adherence to matrix proteins, such as type I collagen, fibronectin, laminin, and fibrinogen. One-day-old cultures of strains OH599 and OH600 were readily ingested by PMNs in the absence of opsonins, while cells from 6-day-old cultures were resistant. Both young and old cultures of the reference strains of B. cereus were resistant to PMN ingestion. Preincubation of PMNs with the phagocytosis-resistant strains of B. cereus did not affect the phagocytosis of the sensitive strain. Negatively stained cells of OH599 and OH600 studied by electron microscopy had a crystalline protein layer on the cell surface. In thin-sectioned cells of older cultures (3 to 6 days old), the S-layer was observed to peel off from the cells. No S-layer was detected on the reference strains. Extraction of cells with detergent followed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis revealed a major 97-kDa protein from the strains OH599 and OH600 but only a weak 97-kDa band from the reference strain ATCC 4342. One-day-old cultures of the clinical strains (hydrophobicity, 5.9 to 6.0%) showed strong binding to type I collagen, laminin, and fibronectin. In contrast, reference strains (hydrophobicity, −1.0 to 4.2%) as well as 6-day-old cultures of clinical strains (hydrophobicity, 19.0 to 53.0%) bound in only low numbers to the proteins. Gold-labelled biotinylated fibronectin was localized on the S-layer on the cell surface as well as on fragments of S-layer peeling off the cells of a 6-day-old culture of B. cereus OH599. Lactose, fibronectin, laminin, and antibodies against the S-protein reduced binding to laminin but not to fibronectin. Heating the cells at 84°C totally abolished binding to both proteins. Benzamidine, a noncompetitive serine protease inhibitor, strongly inhibited binding to fibronectin whereas binding to laminin was increased. Overall, the results indicate that changes in the surface structure, evidently involving the S-layer, during growth of the clinical strains of B. cereus cause a shift from susceptibility to PMN ingestion and strong binding to matrix and basement membrane proteins. Furthermore, it seems that binding to laminin is mediated by the S-protein while binding to fibronectin is dependent on active protease evidently attached to the S-layer.

Bacillus cereus is a gram-positive aerobic and facultative spore-forming rod. It has been regarded as a relatively nonpathogenic opportunist commonly associated with enterotoxin-mediated diarrheal food poisoning (2, 3, 6). This organism has been increasingly isolated from serious nongastrointestinal infections including endocarditis (44), wound infection (21), and osteomyelitis (42). Recently B. cereus has been found in the oral cavity associated with infected root canals and periodontal pockets (31).

A regularly ordered protein or glycoprotein layer (S-layer) has been detected as the outermost component of several gram-negative and gram-positive organisms (3, 30, 33). The functions of the S-layer in bacteria are not completely understood. It has been suggested that the S-layer mediates the adhesion to avian intestinal epithelial cells in Lactobacillus acidophilus (41) and to collagen in Lactobacillus crispatus (45). In Bacillus stearothermophilus DSM2358, the S-layer has been said to function as an adhesion site for high-molecular-weight amylase (13). Increased virulence and resistance to phagocytosis (5, 6, 35) have been associated with the presence of the S-layer in animal pathogens. Ellar and Lundgren (14) described the presence of an S-layer on the surface of B. cereus ATCC 4342. The present study was done to investigate the functional and morphological properties of the cell surface structures of two reference strains (ATCC 4342 and ATCC 14579T) and two clinical strains (OH599 and OH600) of B. cereus. In this connection, cell surface hydrophobicity, susceptibility to phagocytic ingestion, and adhesion to laminin, type I collagen, fibrinogen, and fibronectin were examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

B. cereus strains were received from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC 14579T and ATCC 4342) or isolated from an infected root canal and periodontal pocket (OH599 and OH600). The clinical strains were identified on the basis of colony morphology, Gram-stain reaction, spore formation, and biochemical tests with the BioMerieux database system. The bacterial strains were grown on brucella horse blood agar plates supplemented with menadione (10 μg/ml) and hemin (5 μg/ml) in an incubator containing 5% CO2 (water-jacketed incubators; Forma Scientific Inc.) at 37°C for 1 to 6 days.

Electron microscopy.

The samples for both thin-sectioning and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were prepared as described by Lounatmaa (29). Briefly, the samples for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were prefixed in phosphate-buffered (pH 7.2) 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h at room temperature (RT) and overnight at 4°C. The fixed cells were collected by centrifugation and washed three times with phosphate buffer. All samples were postfixed with phosphate-buffered 1% osmium tetroxide and dehydrated. For the SEM, the bacteria were critical point dried and sputter coated with platinum. For negative staining (TEM), the bacteria were collected from brucella horse blood agar plates, transferred into a small amount of phosphate buffer and stained with 1% (wt/vol) phosphotungstic acid (pH 6.5). The transmission electron micrographs were taken with a JEOL 1200-EX transmission electron microscope at 60 kV, and the scanning electron micrographs were taken with a Zeiss DSM 962 scanning electron microscope at 20 kV.

Hydrophobicity assay and extraction of surface proteins.

Bacterial cell surface hydrophobicities were measured by the hexadecane method as described previously (37). One- to 6-day-old cultured cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) before adjusting the cell suspensions to an optical density of 0.6 (λ = 450 nm, UltrospecII; LKB-Pharmacia) for hydrophobicity assay. Two parallel test tubes of the same samples were used for each measurement and all strains were tested three times, with new cultures being used each time.

For the examination of surface proteins, bacterial cells cultured for 1, 3, and 6 days were collected from the agar plates, washed once in PBS (pH 7.4), and suspended in the same buffer; the cell suspensions were adjusted to standard optical density. Equal volumes (4 ml) of the cell suspensions were centrifuged (3,000 × g, 6 min). The pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-Tris-HCl (pH 8) and shaken for 30 min at RT. After centrifugation, the supernatants were boiled for 5 min in sample buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl, 1% SDS, 10% glycerol, 1% mercaptoethanol, and 0.0005% bromophenol blue) and analyzed by SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) as described by Laemmli (27) (Mini Protean II; Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). Cells collected from the same experiments were boiled for 5 min in sample buffer, and the supernatants were used for the whole-cell protein profile analysis by SDS-PAGE.

Phagocytic ingestion.

The ingestion of B. cereus OH599, OH600, ATCC 14579T, and ATCC 4342 by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) was studied as described by Ding et al. (11). PMNs were separated from human blood by the modified dextran-Ficoll method (43). One-, 3- and 6-day-old cultures of B. cereus were collected from brucella blood agar plates, washed once with PBS (pH 7.4), and suspended in the same buffer. Bacterial cell concentrations (in colony-forming units per milliliter) in the experiments were calculated by serial 10-fold dilutions, and the number of PMN cells was counted by direct phase-contrast microscopy with a Bürker’s counting chamber (Hawksley, Lancing, England). The suspended cells were mixed with PMNs in the ratio 10:1 (3.9 × 107 to 5.5 × 107/3.3 × 106), and shaken gently at RT for 0, 30, or 60 min. Phagocytosis was stopped by cooling the samples on ice, and the phagocytosis was examined with a fluorescence microscope (FITC-filter, X400; Leitz, Germany). For determination of phagocytic ingestion, 1 ppm acridine orange (Gurr, London, England) in PBS was added to the samples (1:2). At least 50 PMNs were counted from the two parallel samples of each experiment, and experiments were repeated three or four times. The percentages of PMNs which ingested at least one bacterium and the average number of ingested bacteria per leukocyte were calculated. The clinical strain Porphyromonas gingivalis ES64 was used as a positive control, and Eubacterium yurii subsp. margaretiae ES4C was used as a negative control. The samples for thin sections were prepared for electron microscopy as previously described (29).

Antibody production.

The antiserum was raised in adult rabbits by subcutaneous injections with purified S-protein and formalinized whole cells of B. cereus OH599. For the isolation of the S-protein, the bacterial cells were harvested from brucella blood agar plates after 2 days of culturing, washed in PBS, and suspended in nonreducing sample buffer containing 0.06 M Tris-HCl, 1% SDS, 10% glycerol, and 0.0005% bromophenol blue. The samples were kept in water at 100°C for 5 min before SDS-PAGE was performed in 10% polyacrylamide gels at 200 V as described by Laemmli (27). The 97-kDa S-protein band was localized by means of a prestained high-range-molecular-mass protein standard (Bio-Rad) and detected by staining the gel with ice-cold KCl (0.25 M KCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). The protein band was cut from the gel and washed with distilled water, and the S-protein was eluted in the eluting buffer (0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM mercaptoethanol [pH 8]) overnight at RT. The protein solution was concentrated with a lyophilizer (Hetovac VR-1; Heto Lab Equipment A/S, Birkerød, Denmark). The S-layer protein (300 μg of protein in 500 μl of PBS) was mixed with complete Freund’s adjuvant (1:1) and used for subcutaneous immunization. The booster doses in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (125 μg of protein) were given after 3 and 6 weeks. The immune serum was collected 7 days after the last booster injection. Another rabbit was immunized by formalinized (48 h in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C) 1-day cultured whole cells of B. cereus OH599 (2 × 107 cells/injection). Immunoglobulin G (IgG) was purified from the immune sera by using an Econo-Pac Serum IgG Purification Kit (Bio-Rad) in accordance with the manufacturer’s directions and was stored at −20°C. The specificities of anti-S IgG (antibody against S-protein) and anti-W IgG (antibody against the whole cells) were tested by Western blotting, and the titers were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Binding to immobilized matrix proteins.

Bacterial adherence to human plasma fibrinogen (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), human plasma fibronectin (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals), mouse laminin (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.), and type I collagen from rat tail (Sigma) was studied by a previously described assay method in a slightly modified form (9, 26). Binding of 1-, 3- and 6-day-old cultures of B. cereus ATCC 14579T, ATCC 4342, OH599 and OH600 was tested. Chamber slides (Nunc Inc., Naperville, Ill.) were coated overnight at 37°C with fibrinogen (0.1 mg/ml), fibronectin (0.1 mg/ml), laminin (0.1 mg/ml), type I collagen (0.1 mg/ml), or 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma). After washing the chamber slides twice with TPBS (Tween 20 [50 μl] and PBS [100 ml]) and once with PBS, the slides were blocked with 3% BSA at 37°C for 3 h. The slides were rewashed as described earlier, and equal concentrations of bacterial cell suspensions were added to the chambers. After 2 h of incubation, the chamber slides were washed as described above, and the adhered bacteria were fixed for 10 min with 2.5% buffered glutaraldehyde (vol/vol) at RT and visualized by toluidine blue staining (1 g of Na2B4O7 · 10H2O and 1 g of toluidine blue in 200 ml of distilled H2O). The number of adhered bacteria was counted by phase-contrast microscopy with a magnification of 1,000× in at least six microscopic fields per sample. The experiments were carried out two to four times.

ELISA was used to test the adherence of the cells of B. cereus OH599 and cell-derived material to fibronectin. Microtiter plate wells (ELISA) were coated with fibronectin (0.1 mg/ml in PBS) and 3% BSA at 37°C overnight. The wells were washed twice with TPBS and once with PBS (pH 7.4) and blocked with 3% BSA for 2 h at 37°C. Bacterial cells (1- and 6-day-old cultures) were collected from brucella blood agar plates, washed once in PBS, and adjusted to equal concentrations in PBS before transfer to the ELISA wells. After 2 h of incubation, the attached bacterial cells were labelled with anti-S IgG (1:3,000 in 1% BSA-Tris-buffered saline [20 mM Tris, 0.5 M NaCl]) and with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000 in 1% BSA-TPBS; Sigma Immuno Chemicals), which was used as a secondary antibody. After addition of p-nitrophenylphosphate (Sigma) the binding of cells or cell-derived material was measured colorimetrically at 405 nm (Titertek Multiskan Plus; Elflab, Helsinki, Finland).

The binding of B. cereus OH599 to soluble fibronectin was examined by TEM with biotinylated fibronectin and gold-labelled ExtrAvidin (10 nm of colloidal gold-labelled ExtrAvidin in 50% glycerol; Sigma). Fibronectin was biotinylated by adding 2 μl of biotinamidocaproate N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (50 mg/ml dimethyl sulfoxide) to 1 ml of fibronectin solution. After 2.5 min, the reaction was stopped with Tris buffer (pH 8; final concentration, 100 mM). Biotin (2 μl of biotinamidocaproate N-hydroxysuccinimide ester in 1 ml of PBS) in Tris buffer without fibronectin was used in the control samples. One- and 6-day cultured cells (1.2 × 108 cell/ml) were collected from agar plates, washed once in PBS, and resuspended to the biotin-fibronectin (1 μg/ml) solution or biotin solution. After 2 h of incubation at RT, the bacterial cells were washed once in 20 mM Tris buffer. Gold-labelled ExtrAvidin (1:20 in PBS) was added, and the samples were prepared for TEM as described above.

Inhibition of binding to matrix proteins.

One-day-old cells of B. cereus OH599 were preincubated with 10 and 100 mM lactose, anti-S IgG (1:10 dilution in PBS), anti-W IgG (1:10 dilution in PBS), fibronectin (0.1 mg/ml in PBS), and laminin (0.1 mg/ml in PBS) for 1 h at RT. After incubation, the cells were repeatedly washed in PBS, adjusted to equal concentrations in the same buffer, and transferred to glass slide wells previously coated with fibronectin and laminin as described above. Adherence to fibronectin and laminin of heat-treated 1-day-old cultures of OH599 was also tested. The heat treatment was done by keeping the bacterial cell suspension at 84°C in a heat bloc (Grant Instruments Ltd., Cambridge, England) for 30 min before the attachment assay. The number of adhered bacteria was determined as described above and compared to those from assays of bacterial binding to fibronectin and laminin without any inhibition. The experiments were carried out at least three times with new cultures each time.

To determine the role of the proteinase activity of B. cereus in adhesion to matrix proteins, 100 mM benzamidine (final concentration) was used to inhibit the proteinase activity of B. cereus OH599. Effectiveness of protease inhibition by benzamidine was verified by Azocoll assay. One- and 6-day cultured cells of B. cereus OH599 were adjusted to equal concentrations in PBS. The bacterial cell suspension (0.3 ml) was incubated with 1.5 ml of Azocoll suspension (1 mg/ml in PBS) in the absence or presence of 100 mM benzamidine. After incubation for 3, 5, and 23 h, Azocoll degradation was measured spectrophotometrically and compared to positive (no inhibition) and negative (no bacteria) controls.

RESULTS

Surface properties and extraction of surface proteins.

Cells of 1-, 3- and 6-day-old cultures of both reference strains were hydrophilic. Young cells of the clinical strains were also hydrophilic, whereas 3- and 6-day-old cultures were hydrophobic, as measured by the hexadecane method (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Cell surface hydrophobicities of 1-, 3-, and 6-day-old cultures of B. cereus strains

| Length of culture (days) | % of hydrophobicity ± SD of B. cereus straina:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OH599 | OH600 | ATCC 14579T | ATCC 4342 | |

| 1 | 6.0 ± 2.3 | 5.9 ± 6.7 | 0.2 ± 4.7 | 3.3 ± 2.0 |

| 3 | 19.0 ± 11.6 | 21.0 ± 3.0 | −1.0 ± 1.6 | 1.1 ± 0.5 |

| 6 | 53.0 ± 5.3 | 38.0 ± 13.4 | 4.2 ± 9.7 | 3.5 ± 5.9 |

Values are the means ± SD of three separate experiments.

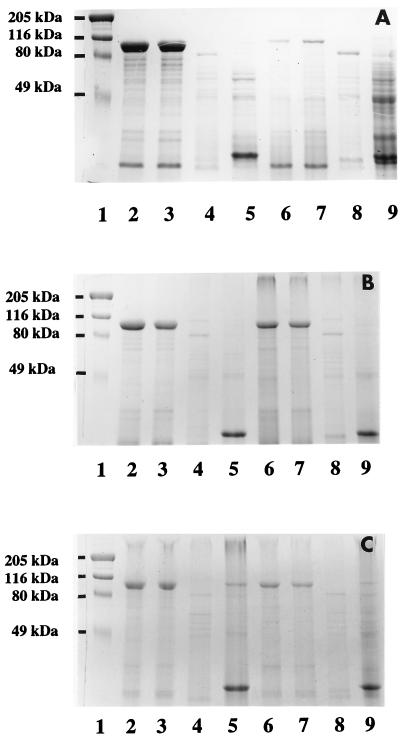

Whole cells of B. cereus cultured for 1, 3, and 6 days were extracted with 1% SDS to examine the protein profiles by SDS-PAGE. A major 97-kDa band was obtained from the two clinical strains of B. cereus. No corresponding band was detected in the reference strains; however, a weak 97-kDa band could be seen on SDS extract from 6-day-old cultures of strain ATCC 4342. Anti-whole cells and anti-S-layer antibodies detected the 97-kDa band in strains OH599 and OH600 as determined by Western blotting. A weak staining of the 97-kDa band of strain ATCC 4342 was also seen by treatment with anti-S-layer antibody. No differences in the relative intensities of the protein bands obtained from clinical strains of 1-, 3- or 6-day-old cultures in the whole-cell protein profiles could be seen (Fig. 1A, B, and C).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of cell surface proteins of B. cereus OH599, OH600, ATCC 14579T, and ATCC 4342. Whole-cell protein profiles (lanes 2 to 5) and 1% SDS extracts (lanes 6 to 9) of 1- (A), 3- (B), and 6- (C) day-old cultures are shown. Lane 1, prestained high-molecular-mass standard (myosin, 206 kDa; β-galactosidase, 117 kDa; BSA, 89 kDa; ovalbumin, 47 kDa). Lanes 2 and 6, OH599; lanes 3 and 7, OH600; lanes 4 and 8, ATCC 14579T; lanes 5 and 9, ATCC 4342.

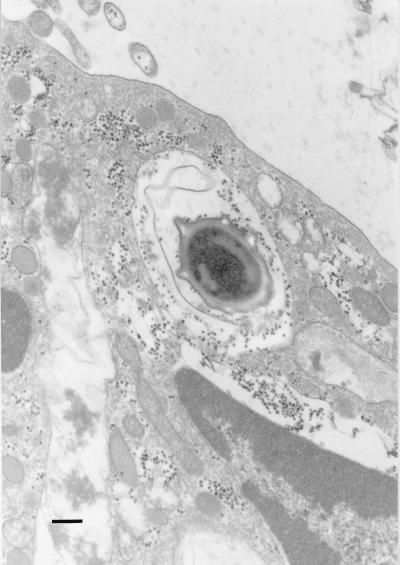

Ultrastructure of B. cereus.

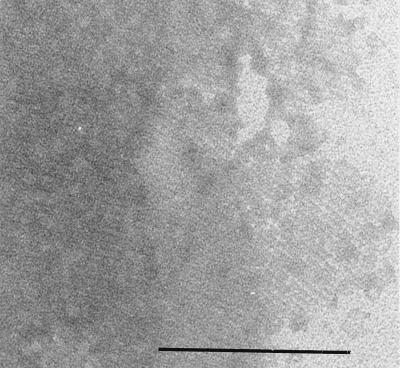

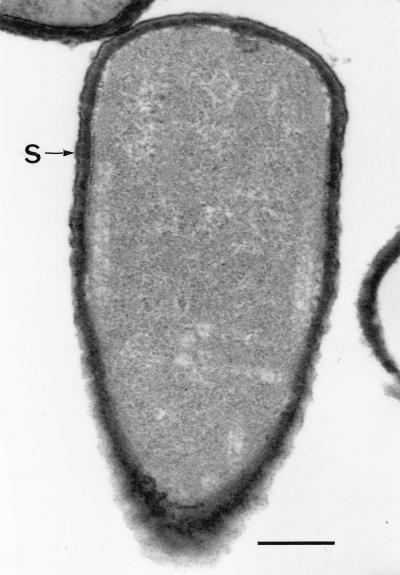

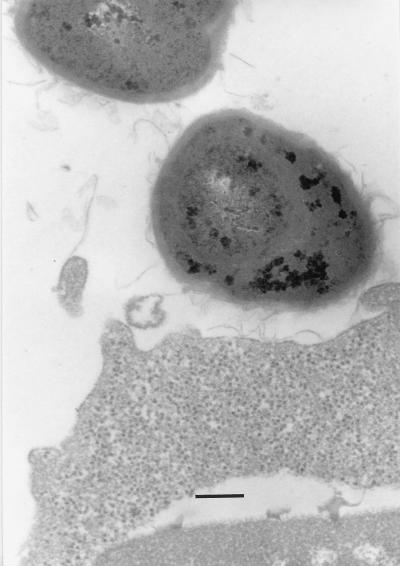

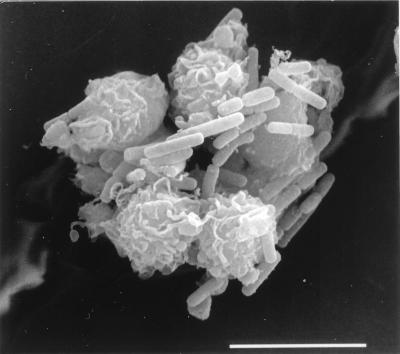

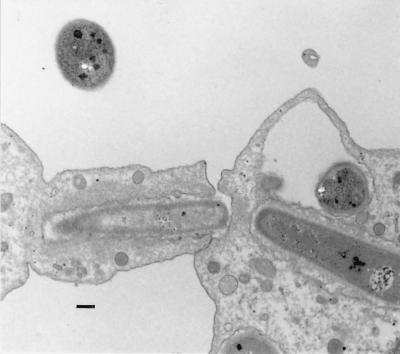

The ultrastructure of all strains was studied. A crystalline cell surface protein layer was observed by negative staining and by thin sectioning of the cells of the clinical isolates of B. cereus (Fig. 2 and 3). In 1-day-old cultures, the S-layer was covering the entire cell surface whereas in specimens from 6-day-old cultures, the S-layer was seen peeling off from the cells (see Fig. 9). No periodic cell surface structures were detected in B. cereus ATCC 14579T or ATCC 4342.

FIG. 2.

Negatively stained fragment of an S-layer of B. cereus OH599. The periodic structure is clearly seen. Bar, 0.2 μm.

FIG. 3.

Thin-sectioned cell of clinical isolate OH599 with an S-layer indicated (S). Bar, 0.2 μm.

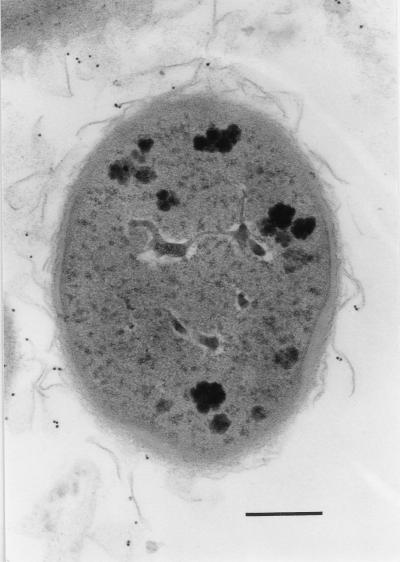

FIG. 9.

A pre-embedding immunoelectron micrograph showing (with gold particles) the localization of the biotinylated fibronectin on the S-layer (partly peeling off) of a 6-day cultured cell of B. cereus OH599. Bar, 0.2 μm.

Phagocytosis of B. cereus strains.

The susceptibilities to nonopsonic PMN-phagocytosis of 1-, 3-, and 6-day-old cultures of B. cereus were assessed by fluorescence microscopy. One-day-old cultures of the clinical strains were ingested in 30 min by human PMNs while the reference strains and 3- and 6-day-old cultures of the clinical strains were resistant (Table 2). Phagocytosis of the sensitive strain OH599 was not affected by 30 min of preincubation of PMNs with a 1-day-old culture of ATCC 14579T or a 6-day-old culture of OH599, which were resistant to phagocytosis (data not shown). The phagocytic ingestion of B. cereus cells and spores was also demonstrated by TEM and SEM, and thin sections made from 6-day cultured cells showed sheets of detached S-layer attached to PMN-cells (Fig. 4 through 7).

TABLE 2.

Phagocytic ingestion of B. cereus strains cultured for 1, 3, or 6 days

| Strain | Length of culture (days) | Phagocytic ingestion valuea after incubation for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None

|

30 min

|

60 min

|

|||||

| % PMN | B/PMN | % PMN | B/PMN | % PMN | B/PMN | ||

| OH599 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 94 | 6.48 | 100 | 8.48 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.07 | 36 | 1.33 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.05 | |

| OH600 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 94 | 6.30 | 100 | 8.40 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0.12 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.01 | |

| ATCC 4342 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ATCC 14579T | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.06 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.02 | 6 | 0.11 | |

At least 50 PMNs were counted in each assay and the average of two parallel samples is given. Representative results of one of the three separate experiments are shown here. % PMN, percentage of PMNs having ingested at least one bacterium; B/PMN, average number of bacteria ingested per PMN.

FIG. 4.

Numerous S-layer fragments (OH600) peeled off from the cell wall between a PMN and bacteria. Bar, 0.2 μm.

FIG. 7.

Scanning electron micrograph showing initiation of the phagocytosis (OH599). Bar, 10 μm.

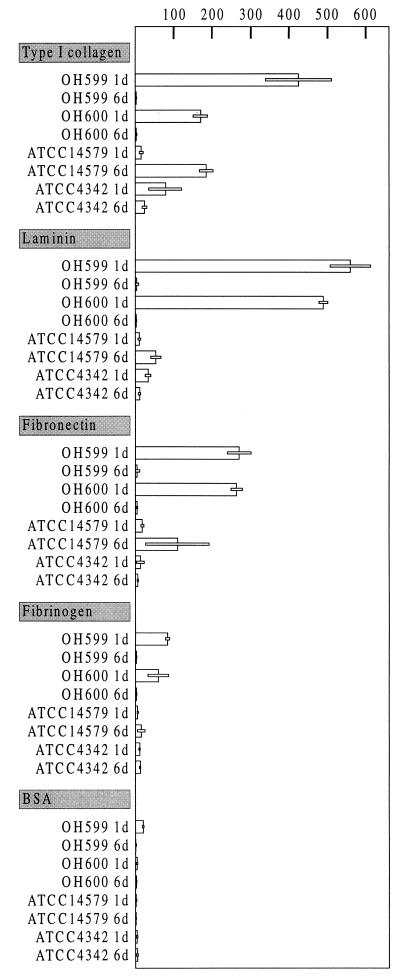

Adherence of B. cereus strains to matrix proteins.

The adherence of B. cereus strains to matrix proteins immobilized on glass slides was examined by direct counting by phase-contrast microscopy. One-day-old cultures of the clinical strains adhered efficiently to laminin, type I collagen, and fibronectin, while binding to fibrinogen was only slightly better than binding to BSA (Fig. 8). The number of attached cells was considerably lower when 3- and 6-day-old cultures of the clinical strain or 1-, 3-, and 6-day-old cultures of the reference strains were tested (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Adhesion of B. cereus OH599, OH600, ATCC 4342, and ATCC 14579T (1- and 6-day-old [1d and 6d] cultures) to the indicated matrix proteins. Bar lengths indicate the mean numbers of attached cells per microscopic field of two to four separate experiments. Inset bars shows standard deviations.

The adhesion of biotinylated fibronectin to the clinical strain of B. cereus OH599 was also detected by gold-labelled ExtrAvidin. Fibronectin adhered to the S-layer on the bacterial cell surface and to the S-layer which was peeling off from the cells of a 6-day-old culture (Fig. 9). No label was seen on the cell surfaces of the reference strain ATCC 14579T or on the control samples incubated without fibronectin. The IgG against purified S-protein of B. cereus OH599 was used as a primary antibody when the adherence of 1- and 6-day-old cultures of B. cereus OH599 was tested by the ELISA method. The binding of the cells or cell-derived material to fibronectin was equal in both young and old cultures. The average absorbances ± standard deviations as determined colorimetrically by ELISA (λ = 405 nm) were as follows: 1-day-old culture of OH599, 0.93 ± 0.12; 6-day-old culture of OH599, 1.13 ± 0.21; and BSA control, 0.36 ± 0.15 (averages of three separate experiments).

Binding of 1-day cultured cells of B. cereus OH599 to matrix proteins was inhibited by heat treatment of the cells at 84°C (Table 3). Pretreatment of the cells with antisera made against purified S-protein of OH599 did not inhibit the adhesion to fibronectin but reduced the number of cells attached to laminin by 32% (Table 3). Fibronectin (0.1 mg/ml), laminin (0.1 mg/ml), and lactose (10 and 100 mM) pretreatment reduced the bacterial cell adhesion to laminin but had no effect on adhesion to fibronectin. When the proteinase activity of B. cereus OH599 was inhibited by 100 mM benzamidine, the adherence to fibronectin was reduced by 69% and an increase was detected in the adhesion to laminin (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Inhibition of attachment of 1-day-old B. cereus OH599 cultures to fibronectin and laminina

| Pretreatment | % Binding to:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Fibronectin | Laminin | |

| None | 100 ± 5.5 | 100 ± 15.5 |

| Lactose, 10 mM | 93 ± 6.1 | 62 ± 19.8 |

| Lactose, 100 mM | 93 ± 0.6 | 72 ± 29.8 |

| Fibronectin | 89 ± 1.5 | 69 ± 10.0 |

| Laminin | 96 ± 6.4 | 60 ± 7.0 |

| Anti-S IgG | 100 ± 0.6 | 68 ± 10.7 |

| Anti-W IgG | 98 ± 2.6 | 85 ± 19.0 |

| Heating at 84°C for 1 h | 3 ± 2.3 | 8 ± 3.0 |

| Benzamidine, 100 mM | 31 ± 5.4 | 150 ± 4.6 |

Bacterial cells were treated with the substances indicated for 60 min before adherence assays. Results are the mean percentages of binding ± standard deviations compared to binding to fibronectin or laminin without any inhibitor (= 100%).

DISCUSSION

Crystalline cell surface protein, S-layer, has been detected in several bacterial species isolated from infections of the oral cavity (23, 24, 30, 34). In recent years, the involvement of the S-layer in bacterial adhesion and in bacteria-host interactions has attracted interest due to the potential association with bacterial virulence (6, 20).

Ellar and Lundgren (14) have previously described the presence of an S-layer on the surface of B. cereus ATCC 4342. In the present study, however, no S-layer was detected on the cell surface of reference strains ATCC 14579T and ATCC 4342. Obviously, several years of preservation and culturing in laboratories can suppress the S-protein expression of the reference strains (7). The S-layer of strain ATCC 4342 has earlier been shown to have tetragonal symmetry (14). The symmetry in our clinical isolates was periodic but not tetragonal. The observed structural differences of the S-layer protein may also result from differences in culture conditions. The synthesis of an S-layer protein with p6 (hexagonal) symmetry in B. stearothermophilus was shown to be inhibited, and this protein was replaced by a new type of S-layer protein with oblique lattice when the oxygen supply was increased and glucose was used as the sole carbon source (38, 39).

Different collagen types and glycoproteins, such as fibronectin and laminin, are constituents of the extracellular matrix, basement membrane, and body fluids acting in the cell anchorage and migration as well as in blood clot formation (15). Adherence to these proteins and other host molecules is an important step for bacteria to express their virulence (16, 25, 40). Recently, attachment to laminin and fibronectin in Aeromonas salmonicida (12), to avian intestinal epithelial cells in L. acidophilus (41), and to collagen in L. crispatus (45) has been shown to require a crystalline surface protein layer. In the present study, cells of 1-day-old cultures of the clinical strains OH599 and OH600, both with an S-layer, attached in high numbers to type I collagen, laminin, and fibronectin.

Three- and 6-day cultured cells of strains OH599 and OH600 showed low or practically no ability to attach to these matrix proteins as revealed by direct microscopy of toluidine blue-stained cells. However, when the adherence to fibronectin and laminin was examined by the ELISA method, we found no significant differences in binding between the 1- and 6-day-old cells of B. cereus OH599. Interestingly, samples from parallel cell cultures examined by electron microscopy showed that the S-layer was strongly peeling off of older cells but to only a minor extent from 1-day-old cultures. The results suggest that the detached crystalline surface protein from older cells adhered to the matrix proteins, and that this material was detected by anti-S antibodies as well as with whole-cell antibodies that were also produced mainly against the S-protein, but not by toluidine blue staining showing only whole cells.

Proteases of P. gingivalis and Treponema denticola have earlier been shown to have a role in the binding of these bacteria to fibronectin and hyaluronic acid, respectively (18, 22, 28). B. cereus possesses a strong pattern of proteases, including collagenolytic enzymes (32). Binding to laminin and fibronectin was slow as only <60% of the 1-day cultured cells of B. cereus OH599 had adhered after 30 min. Inhibition of binding to fibronectin by 100 mM benzamidine, a noncompetitive and noncovalent serine proteinase inhibitor, indicated that B. cereus proteinase is involved in binding to fibronectin. Binding to laminin was not, however, decreased but was increased by the presence of 100 mM benzamidine. Although not shown by the present study, it could be possible that the cell surface-associated serine-type proteinase of B. cereus processes the S-layer binding sites so that binding to laminin is decreased and binding to fibronectin is enhanced.

Pretreatment of B. cereus OH599 cells with laminin, fibronectin, lactose, or purified anti-S IgG or anti-W IgG of this strain also had different effects on attachment to fibronectin and laminin. Precoating the bacteria with specific antibodies did not affect the binding to fibronectin, but the adherence to laminin decreased by 32% when the bacteria were precoated with anti-S IgG and by 15% when they were precoated with anti-W IgG. This indicates the involvement of the S-protein in binding to laminin. The inhibition experiments indicate that the binding of B. cereus to fibronectin and laminin occurs by different mechanisms. The receptors mediating adherence to fibronectin seemed to be present in the S-layer sheets peeling off the cells from older cultures as shown by the ELISA method. Biotinylated fibronectin was also localized by electron microscopy in the S-layer by gold-labelled ExtrAvidin. It is thus possible that the proteinase involved in fibronectin binding is embedded in the S-layer. Inhibition of binding by over 90% to both matrix glycoproteins by heat treatment of B. cereus may also indicate the involvement of protein-glycoprotein structures.

Attachment to laminin was not totally inhibited by antibody made against S-protein, possibly because it did not block all receptors available for binding. Extraction of surface proteins with 1% SDS and by subsequent boiling could also lead to protein that raises an antiserum with limited affinity to native protein.

Fibronectin or laminin pretreatment of bacteria decreased their adhesion to laminin, but had little or no effect on the adhesion to fibronectin. This is in accordance with observations by Dawson and Ellen (10), who reported an enhanced binding of fibronectin-pretreated T. denticola cells to fibronectin. Fibronectin and laminin consist of multiple domains with distinct binding functions (19). It is possible that these proteins possess complementary receptors which affect the adherence to laminin but not to fibronectin to which the attachment was mediated by a proteolytic enzyme on the cell surface in the S-layer. It has also been presumed that immobilized and soluble fibronectins have differences in receptor conformations (17).

Bacterial surface properties and structures are important in the regulation of bacterium-phagocyte interactions. Blaser et al. (4) have reported phagocytosis resistance in Campylobacter fetus strains possessing an S-layer. We have earlier studied nonopsonophagocytosis of three subspecies of E. yurii, all hydrophobic and expressing S-protein. The results indicated that the S-layer of the only resistant subspecies, E. yurii subsp. margaretiae, lacked receptors necessary for leukocyte binding and phagocytosis (24). In the present study, we examined the susceptibility to phagocytosis of clinical and reference strains of B. cereus cultured for different time periods. Cells from 1- and 6-day-old cultures of the American Type Culture Collection reference strains were all resistant to PMN phagocytosis without the presence of opsonizing antibodies and complement proteins. However, young cultures of B. cereus OH599 and OH600 with an entire S-layer covering the cells were sensitive to nonopsonic PMN-phagocytosis, whereas cells from older cultures of the same strains were resistant. By TEM, sheets of S-layer in 3- and 6-day-old cultures of strains OH599 and OH600 were seen in contact with the PMNs, and only insignificant ingestion of the cells was detected. When 6-day-old cultured bacterial cells were preincubated with purified anti-S IgG or anti-W IgG, they were rapidly ingested by the PMNs. Resistance of bacterial cells to nonopsonophagocytosis by PMNs can in general be explained by a lack of specific receptors mediating the binding to PMNs or by a direct inhibitory effect by the bacteria on their function. Preincubation of PMNs with the phagocytosis-resistant strain ATCC 14579T or OH599 from 6-day-old cultures had no inhibitory effect on the subsequent phagocytosis of the sensitive OH599 from 1-day-old cultures. This strongly indicates that resistance to phagocytosis of B. cereus cells from old cultures was not due to inhibition of the PMN functions.

Cell surface hydrophobicity of the clinical strains of B. cereus increased with aging cultures. Hydrophobicity is important in nonopsonophagocytosis of several bacteria, and a high level of hydrophobicity facilitates phagocytosis (1, 8). However, in our earlier study with E. yurii, we found that high hydrophobicity alone without receptor mediated-binding resulted in low phagocytic ingestion (24). In the present study, hydrophobic cells from older cultures were resistant whereas hydrophilic strains from young cultures were sensitive to PMN phagocytosis. Increase of hydrophobicity and apparent loss of PMN-binding sites are probably both results of the detachment of the S-layer in older cells.

These results indicate that a protease, evidently attached to the S-layer, up-regulates the binding of B. cereus to fibronectin and on the other hand down-regulates laminin binding, reflecting matrix protein-specific actions in proteolytic virulence properties of B. cereus. Also, changes during aging of the cultures related to the S-layer expression and the cell wall conformation of the clinical isolates of B. cereus are followed not only by changes in hydrophobicity but also by changes in the binding sites available for PMN-attachment.

FIG. 5.

Two PMN-ingested bacteria (OH600). Notice that two PMNs are trying to phagocytize the same cell. Bar, 0.2 μm.

FIG. 6.

Transmission electron micrograph showing an ingested spore (OH600) inside a PMN. Bar, 0.2 μm.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financially supported by the Finnish Dental Society (to A.K.) and the Academy of Finland (to K.L.).

We thank Arja Strandell for preparing the samples for electron microscopy and Maire Holopainen for Azocoll assays.

REFERENCES

- 1.Absolom D R. The role of bacterial hydrophobicity in infection: bacterial adhesion and phagocytic ingestion. Can J Microbiol. 1988;34:287–298. doi: 10.1139/m88-054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beecher D J, Schoeni J L, Wong A C. Enterotoxic activity of hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4423–4428. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4423-4428.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beveridge T J. The response of S-layered bacteria to the Gram stain. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;20:101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaser M J, Smith P F, Repine J E, Joiner K A. Pathogenesis of Campylobacter fetus infections. Failure of encapsulated Campylobacter fetus to bind C3b explains serum and phagocytosis resistance. J Clin Investig. 1988;81:1434–1444. doi: 10.1172/JCI113474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaser M J. Role of the S-layer proteins of Campylobacter fetus in serum-resistance and antigenic variation: a model of bacterial pathogenesis. Am J Med Sci. 1993;306:325–329. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199311000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaser M J, Pei Z. Pathogenesis of Campylobacter fetus infections: critical role of high-molecular-weight S-layer proteins in virulence. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:372–377. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borinski R, Holt S C. Surface characteristics of Wolinella recta ATCC 33238 and human clinical isolates: correlation of structure with function. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2770–2776. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.2770-2776.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calvinho L F, Almeida R A, Oliver S P. Influence of Streptococcus dysgalactiae surface hydrophobicity on adherence to mammary epithelial cells and phagocytosis by mammary macrophages. Zentbl Vetmed Reihe B. 1996;43:257–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1996.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulot P, Bouchara J-P, Renier G, Annaix V, Planchenault C, Tronchin G, Chabasse D. Specific interaction of Aspergillus fumigatus with fibrinogen and its role in cell adhesion. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2169–2177. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2169-2177.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson J R, Ellen R P. Tip-oriented adherence of Treponema denticola to fibronectin. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3924–3928. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3924-3928.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding Y, Haapasalo M, Kerosuo E, Lounatmaa K, Kotiranta A, Sorsa T. Release and activation of human neutrophil matrix metallo- and serine proteinases during phagocytosis of Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:237–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doing P, Emödy L, Trust T J. Binding of laminin and fibronectin by the trypsin-resistant major structural domain of the crystalline virulence surface array protein of Aeromonas salmonicida. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egelseer E, Schocher I, Sára M, Sleytr U B. The S-layer from Bacillus stearothermophilus DSM 2358 functions as an adhesion site for a high-molecular-weight amylase. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1444–1451. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1444-1451.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellar D J, Lundgren D G. Ordered structure in the cell wall of Bacillus cereus. J Bacteriol. 1967;94:1778–1780. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.5.1778-1780.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engvall E, Ruoslahti E, Miller E J. Affinity of fibronectin to collagens of different genetic types and to fibrinogen. J Exp Med. 1978;147:1584–1595. doi: 10.1084/jem.147.6.1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster T J, McDevitt D. Surface-associated proteins of Staphylococcus aureus: their possible roles in virulence. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;118:199–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbons R J. Bacterial adhesion to oral tissues: a model for infectious diseases. J Dent Res. 1989;68:750–760. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680050101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haapasalo M, Hannam P, McBride B C, Uitto V-J. Hyaluronan, a possible ligand mediating Treponema denticola binding to periodontal tissue. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1996;11:156–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingham K C, Brew S A, Broekelmann T J, McDonald J A. Thermal stability of human plasma fibronectin and its constituent domains. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:11901–11907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kay W W, Trust T J. Form and functions of the regular surface array (S-layer) of Aeromonas salmonicida. Experientia. 1991;47:412–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kemmerly S A, Pankey G A. Oral ciprofloxacin therapy for Bacillus cereus wound infection and bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:189. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kontani M, Ono H, Shibata H, Okamura Y, Tanaka T, Fujiwara T, Kimura S, Hamada S. Cysteine protease of Porphyromonas gingivalis 381 enhances binding of fimbriae to cultured human fibroblasts and matrix proteins. Infect Immun. 1996;64:756–762. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.756-762.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotiranta A, Haapasalo M, Lounatmaa K, Kari K. Crystalline surface protein of Peptostreptococcus anaerobius. Microbiology. 1995;140:1065–1073. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-5-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotiranta A, Lounatmaa K, Kari K, Kerosuo E, Haapasalo M. Function of the S-layer of some Gram-positive bacteria in phagocytosis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;20:110–114. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kukkonen M, Raunio T, Virkola R, Lähteenmäki K, Mäkelä P H, Klemm P, Clegg S, Korhonen T K. Basement membrane carbohydrate as a target for bacterial adhesion: binding of type I fimbriae of Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli to laminin. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:229–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuusela P, Vartio T, Vuento M, Myhre E B. Attachment of staphylococci and streptococci on fibronectin, fibronectin fragments, and fibrinogen bound to a solid phase. Infect Immun. 1985;50:77–81. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.1.77-81.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lantz M S, Allen R D, Duck L W, Blume J L, Switalski L M, Hook M. Identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis components that mediate its interactions with fibronectin. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4263–4270. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4263-4270.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lounatmaa K. Electron microscopic methods for the study of bacterial surface structures. In: Korhonen T K, Dawes E A, Mäkelä P H, editors. Enterobacterial surface antigens: methods for molecular characterization. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1985. pp. 243–261. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lounatmaa K, Haapasalo M, Kerosuo E, Jousimies-Somer H. S-layer found on clinical isolates. In: Beveridge T J, Koval S F, editors. Advances in bacterial paracrystalline surface layers. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maiden M F J, Lai C-H, Tanner A. Characteristics of oral gram-positive bacteria. In: Slots J, Taubman M A, editors. Contemporary oral microbiology and immunology. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1992. pp. 342–372. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mäkinen K K, Mäkinen P L. Purification and properties of an extracellular collagenolytic protease produced by the human oral bacterium Bacillus cereus (strain Soc 67) J Biol Chem. 1987;262:12488–12495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Messner P, Sleytr U B. Crystalline bacterial cell-surface layers. Adv Microbiol Physiol. 1992;33:214–275. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nitta H, Holt S C, Ebersole J L. Purification and characterization of Campylobacter rectus surface layer proteins. Infect Immun. 1997;65:478–483. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.478-483.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noanao B, Trust T J. The synthesis, secretion and role in virulence of the paracrystalline surface protein layers of Aeromonas salmonicida and A. hydrophila. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;154:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ombui J N, Schmieger H, Kagiko M M, Arimi S M. Bacillus cereus may produce two or more diarrheal enterotoxins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;149:245–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenberg M, Gutnick D, Rosenberg E. Adherence of bacteria to hydrocarbons: a simple method for measuring cell-surface hydrophobicity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1980;9:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sára M, Sleytr U B. Comparative studies of S-layer proteins from Bacillus stearothermophilus strains expressed during growth in continuous culture under oxygen-limited and non-oxygen-limited conditions. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7182–7189. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7182-7189.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sára M, Kuen B, Mayer H F, Mandl F, Schuster K C, Sleytr U B. Dynamics in oxygen-induced changes in S-layer protein synthesis from Bacillus stearothermophilus PV72 and the S-layer-deficient variant T5 in continuous culture and studies of the cell wall composition. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2108–2117. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2108-2117.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidt K-H, Mann K, Cooney J, Köhler W. Multiple binding of type 3 streptococcal M protein to human fibrinogen, albumin and fibronectin. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1993;7:135–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1993.tb00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schneitz C, Nuotio L, Lounatmaa K. Adhesion of Lactobacillus acidophilus to avian intestinal epithelial cells mediated by the crystalline bacterial cell surface layer (S-layer) J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;74:290–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb03028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schricker M E, Thompson G H, Schreiber J R. Osteomyelitis due to Bacillus cereus in an adolescent: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:863–867. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.6.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Segal A W, Dorling J, Coade S. Kinetics of fusion of the cytoplasmic granules with phagocytic vacuoles in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Cell Biol. 1980;85:42–59. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steen M K, Bruno-Murtha L A, Chaux G, Lazar H, Bernard S, Sulis C. Bacillus cereus endocarditis: report of a case and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:945–946. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.4.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toba T, Virkola R, Westerlund B, Björkman Y, Sillanpää J, Vartio T, Kalkkinen N, Korhonen T K. A collagen-binding S-layer protein in Lactobacillus crispatus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2467–2471. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2467-2471.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]