Visual Abstract

Keywords: clinical trial, dialysis, electrolytes, peritoneal dialysis, ultrafiltration

Abstract

Background

Volume overload is common in patients treated with peritoneal dialysis (PD) and is associated with poor clinical outcome. Steady concentration PD is where a continuous glucose infusion maintains the intraperitoneal glucose concentration and as a result provides continuous ultrafiltration throughout the dwell. The primary objective of this study was to investigate the ultrafiltration rate and glucose ultrafiltration efficiency for steady concentration PD in comparison with a standard continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD) dwell, using the novel Carry Life UF device.

Methods

Eight stable patients treated with PD (six fast and two fast average transporters) were investigated four times: a standard 4-hour CAPD dwell with 2 L of 2.5% dextrose solution as control and three 5-hour steady concentration PD treatments (glucose dose 11, 14, 20 g/h, initial fill 1.5 L of 1.5% dextrose solution). All investigations were preceded by an overnight 2 L 7.5% icodextrin dwell.

Results

Intraperitoneal glucose concentration increased during the first 1–2 hours of the steady concentration PD treatments and remained stable thereafter. Ultrafiltration rates were significantly higher with steady concentration PD treatments (124±49, 146±63, and 168±78 mL/h with 11, 14, and 20 g/h, respectively, versus 40±60 mL/h with the control dwell). Sodium removal and glucose ultrafiltration efficiency (ultrafiltration volume/gram glucose uptake) were significantly higher with steady concentration PD treatments versus the control dwell, where the 11 g/h glucose dose was most efficient.

Conclusions

Steady concentration PD performed with the Carry Life UF device resulted in higher ultrafiltration rates, more efficient use of glucose (increased ultrafiltration volume/gram glucose absorbed), and greater sodium removal compared with a standard 2.5% dextrose CAPD dwell.

Clinical Trial registry name and registration number

A Performance Analysis of the Peritoneal Ultrafiltration (PUF) Achieved With the Carry Life® UF, NCT03724682.

Introduction

Today, more than 400,000 patients are treated with peritoneal dialysis (PD).1 Although PD utilization has grown and patient survival improved, the transfer rate to hemodialysis is still high,2,3 mainly due to peritonitis and inability to remove sufficient amounts of solutes, sodium, and fluid.4–6 In particular, adequate dialytic fluid and sodium removal is crucial in anuric patients treated with PD, and low fluid removal has been associated with increased mortality in such patients.7,8 Furthermore, volume overload and circulatory congestion is a common cause of hospitalization in patients treated with PD.9

To increase ultrafiltration and sodium removal, more hypertonic glucose-based PD solutions are often used resulting in increased glucose absorption up to 200 g/d (i.e., 70 kg/yr),10,11 which in turn contributes to metabolic side effects, including hyperinsulinemia, obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, insulin resistance, and new-onset diabetes, all part of the metabolic syndrome.11–14 Despite this, a large proportion of patients treated with PD remain volume overloaded.15,16 Studies using bioimpedance spectroscopy have reported a prevalence of volume overload of more than 50% in patients treated with PD,17–19 with 25% being severely overhydrated.17

A new treatment for acute episodes of fluid overload, steady concentration PD, was introduced by Pérez-Díaz et al.20 By infusing a 50% glucose solution at a constant rate of 40 mL/h during a 4-hour PD dwell, the intraperitoneal glucose concentration was kept relatively stable, and an average ultrafiltration volume of 653 mL per 4-hour steady concentration PD exchange was achieved in six patients who were treated between one and nine times. A detailed kinetic analysis was not performed. Theoretical modeling of steady concentration PD has been performed by Braide21 and Lee et al.22

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the ultrafiltration rate and the glucose ultrafiltration efficiency and to provide detailed peritoneal solute transfer data for steady concentration PD using the novel Carry Life UF (ultrafiltration) device at three different glucose doses (11, 14, and 20 g glucose/h) in comparison with a standard 2.5% dextrose continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD) dwell. A secondary aim was to compare steady concentration PD with a preceding overnight 7.5% icodextrin dwell.

Methods

Centers and Patients

This study was performed at the PD units in three centers in Sweden: Skåne University Hospital in Lund, Skåne University Hospital in Malmö, and Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm.

Inclusion criteria were clinically stable adult patients treated with PD (age ≥18 years), without clinical signs of volume depletion, treated at the clinic for at least 3 months and using icodextrin in their normal PD prescription.

Exclusion criteria were significant illness or active infection in the past 4 weeks, episodes of peritonitis during the past 2 months, active malignant disease, diabetes type 1, abdominal hernias, positive test for HIV and/or hepatitis within the last 3 months, pregnancy, breastfeeding, women of childbearing age without adequate contraception, other conditions deemed by investigator as inappropriate for participation, and participation in a clinical trial interfering with the present trial 1 month before inclusion.

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of Lund (2018/877 and 2018/1030) and by the Swedish Medical Products Agency (5.1-2018-83259). A written consent document was obtained from all participants. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03724682).

The Carry Life UF Device Used in the Study

The Carry Life UF (Triomed AB, Lund, Sweden) is a novel device using the concept of steady concentration PD, that is, glucose is added throughout the PD dwell to maintain the glucose concentration in the PD solution, thereby maintaining an efficient ultrafiltration throughout the dwell (Figure 1). The device connects to the PD catheter through the catheter extension set. After drainage of the peritoneal cavity, the treatment starts with an initial fill of PD solution. During the treatment with the Carry Life UF, a small part of the intraperitoneal fluid is repeatedly transferred to the device, in which it is mixed with a small amount of a 50% glucose solution (Glucose Fresenius Kabi 500 mg/mL, Fresenius Kabi AB, Uppsala, Sweden) and then returned to the patient. Dependent on the dose setting, 11–20 g of glucose is administered every hour. Intermittent drains are performed hourly to remove fluid from the system into a drain bag to avoid overfill. Additional drains can be performed if needed. Although the patient is connected to the device during the treatment, the device and the 50% glucose bag are quite small and can easily be carried by the patient in a small bag specifically developed for this purpose.

Figure 1.

Carry Life UF device used in the study.

Study Design

The clinical investigation was a controlled, multicenter, nonrandomized, clinical investigation of fluid and peritoneal solute transfer rates with steady concentration PD compared with a 4-hour CAPD dwell with a 2.5% dextrose solution (usually denoted as 2.27% anhydrous glucose solution in Europe).

The participants underwent four clinical investigation sessions, performed on all participants in the same order (Table 1).

Table 1.

Schedule of the four clinical investigation sessions

| Clinical Investigation Session | Dwell Time, h | PD Fill Volume, L | Dextrose Concentration of PD Fill, % | Continuous Glucose Infusion, g/h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline CAPDa | 4 | 2.0 | 2.5 | - |

| Carry Life UF 11 g/hb | 5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 11 |

| Carry Life UF 14 g/hb | 5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 14 |

| Carry Life UF 20 g/hb | 5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 20 |

The sessions were performed on all participants in the same order, as listed abovec. Each clinical investigation session was preceded by an overnight 2 L icodextrin dwell (Extraneal 7.5%) (Baxter Healthcare, Castlebar, Ireland), which was drained at the clinic before the clinical investigation session and dialysate samples were taken from the drained fluid. PD, peritoneal dialysis; CAPD, continuous ambulatory PD.

Baseline clinical investigation session, using an initial fill with Physioneal 40, glucose 22.7 mg/mL (n=6) (Baxter Healthcare, Castlebar, Ireland), or Balance 2.3% glucose, 1.25 mmol/L calcium (n=2) (Fresenius Medical Care, Bad Homburg, Germany), similar to a peritoneal equilibration test.

Carry Life UF clinical investigation sessions, using an initial fill with Physioneal 40, glucose 13.6 mg/mL (Baxter Healthcare, Castlebar, Ireland).

At least 5 days (range 5–29 days) between the sessions to enable a similar fluid status for all of the clinical investigation sessions.

After infusion of the dialysis solution, an initial dialysate sample was taken after 10 minutes. Thereafter, hourly dialysate samples were collected. Plasma samples were collected at the start of each session, after 2 hours, and at the end of the treatment sessions. Dialysate concentrations of glucose, sodium, potassium, calcium, phosphate, albumin, creatinine, and urea, together with plasma concentrations of glucose and creatinine, were analyzed using routine laboratory methods.

As this was a pilot study, the expected ultrafiltration volume with the Carry Life UF steady concentration PD concept was unknown; hence, there was a concern of potential overfill. Therefore, an initial fill volume of 1.5 L was selected to avoid overfill due to a potentially large ultrafiltration volume during the clinical investigation sessions. In addition, a small volume of dialysate was drained hourly. Concern about overfill was also the reason for selecting a nonrandomized order of the clinical investigation sessions.

Calculations

The removal of solutes present in the infused fluids (glucose, sodium, and calcium) was calculated by adding the amounts drained from the participant through the hourly drains and the final drain, and then subtracting the amounts administered with the infused PD fluid and the added glucose solution. For solutes not present in the infused fluids, the removal was calculated as the total amount drained (concentration multiplied with volume).

The concentration of sodium in the ultrafiltration volume was calculated from the total sodium removal divided by the ultrafiltration volume and is a theoretical concentration of sodium in the volume removed from the participant.

Residual kidney function was calculated as the mean of the residual kidney creatinine and urea clearances from a 24-hour urine collection.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean±SD. Normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way repeated measure ANOVA and post hoc tested using the Holm–Sidak test for normal distributed data (SigmaPlot for Windows version 14.0, Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). The icodextrin dwells preceding the baseline sessions were used in the statistical analysis (n=8).

Results

Eight clinically stable patients treated with PD were included in the study. The clinical characteristics of the participants are given in Table 2. Four participants had diabetes, two of whom were treated with insulin. The participants had relatively fast peritoneal solute transfer rates (six fast transporters and two fast average transporters). All participants underwent all four clinical investigation sessions without any significant device- or treatment-related adverse events. The first participant entered the study on February 4, 2019, and the study was completed on June 26, 2019.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants included in a clinical trial evaluating steady concentration peritoneal dialysis

| Age, yr | 60±14 (33–74) |

| Sex (male/female) | 6/2 |

| Body weight, kg | 94±20 (55–119) |

| Height, cm | 176±11 (160–192) |

| Time on PD, mo | 8.6±5.6 (3–20) |

| PET solute transfer rate classification | Six fast, two fast average |

| PET 4-h D/P creatinine ratio | 0.82±0.06 (0.69–0.90) |

| 24-h urine volume, mL | 1484±715 (350–2500) |

| Residual kidney function, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 5.7±3.6 (1.2–12.4) |

Data are presented as mean±SD (range) or numbers. Peritoneal equilibration test solute transfer rate classification on the basis of dialysate/plasma creatinine ratio. PD, peritoneal dialysis; PET, peritoneal equilibration test; D/P, dialysate/plasma concentration ratio.

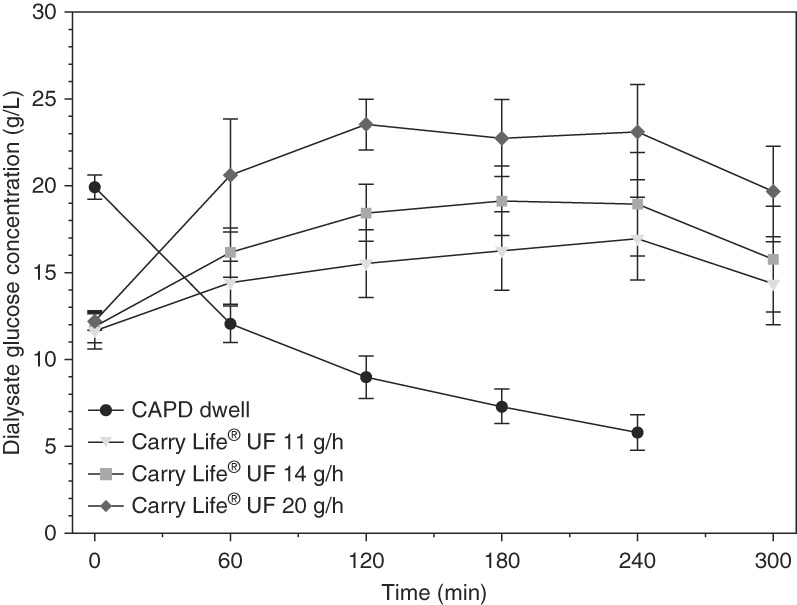

The dialysate glucose concentration decreased as expected during the CAPD dwell, whereas it increased during the first 1–2 hours of the three steady concentration PD sessions, to remain relatively stable thereafter at about 16, 19, and 23 g/L for the three different glucose doses, respectively (Figure 2). Plasma glucose increased slightly with all of the four clinical investigation sessions (32±40 mg/dL with the 2.5% dextrose CAPD dwell, 29±29 mg/dL with the 11 g/h glucose dose, 43±65 mg/dL with the 14 g/h glucose dose, and 40±83 mg/dL with the 20 g/h glucose dose). For the 2.5% dextrose CAPD dwell, the largest plasma glucose increase occurred at the 2-hour time point, whereas for the steady concentration PD sessions, the largest plasma glucose increase occurred at the end of the treatment. It should be noted that the participants were allowed to eat and drink during the clinical investigation sessions.

Figure 2.

Dialysate glucose concentration decreased with the 2.5% dextrose CAPD dwell, whereas it increased initially during 1–2 hours and then remained stable during the three steady concentration PD treatments. Data are presented as mean±SD. CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

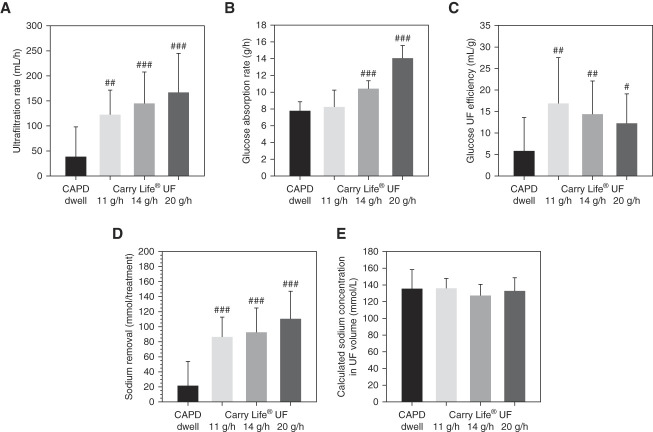

The ultrafiltration rate was 3–4 times higher with the steady concentration PD sessions compared with the CAPD dwell and increased with each higher glucose dose. The differences compared with the CAPD dwell were highly significant, but the differences between the three steady concentration PD glucose doses were relatively small (Figure 3A and Table 3). The glucose absorption rate was similar between the CAPD dwell and the steady concentration PD 11 g/h glucose dose but increased with the higher glucose doses (Figure 3B and Table 3). Compared with the CAPD dwell, the glucose ultrafiltration efficiency (defined as milliliter ultrafiltration volume per gram of glucose absorbed) was higher with the steady concentration PD treatments, being highest with the 11 g/h glucose dose and decreasing with increasing glucose doses (Figure 3C and Table 3).

Figure 3.

Ultrafiltration rate, glucose ultrafiltration efficiency, and sodium removal increased with the three different glucose doses of steady concentration PD, whereas glucose absorption rate only increased for the higher glucose doses. Ultrafiltration rate (A), glucose absorption rate (B), glucose ultrafiltration (UF) efficiency calculated as ultrafiltration volume in milliliter per gram glucose absorbed (C), sodium removal (D), and calculated sodium concentration in UF volume (E), with the 2.5% dextrose CAPD dwell and with the three steady concentration PD treatments. Data are presented as mean±SD. Significant differences are denoted #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus the CAPD dwell.

Table 3.

Results comparing the overnight icodextrin dwell, the continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis dwell, and the three different glucose doses of the steady concentration peritoneal dialysis treatments

| Treatment | Treatment Time, h | Ultrafiltration Volume, mL/Treatment | Ultrafiltration Rate, mL/h | Glucose Absorption Rate, g/h | Glucose Ultrafiltration Efficiency, mL Ultrafiltration/g Glucose Absorbed | Sodium Removal, mmol/Treatment | Albumin Loss, g/Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overnight icodextrin dwell (n=8) | 12.1±1.0a | 617±191a | 51±15 | NA | NA | 92±27a | 3.0±1.2a |

| CAPD dwell with 2.5% dextrose (n=8) | 4.1±0.1b | 162±242b | 40±60 | 7.8±1.1 | 5.9±7.8 | 21±33b | 1.1±0.4b |

| Carry Life UF 11 g/h (n=8) | 5.2±0.3a,b | 646±256a | 124±49c,d | 8.2±2.0 | 17.0±10.6d | 86±27a | 1.4±0.6b |

| Carry Life UF 14 g/h (n=8) | 5.1±0.3a,b | 739±312a | 146±63a,b | 10.4±1.0a | 14.5±7.7d | 92±33a | 1.3±0.5b |

| Carry Life UF 20 g/h (n=8) | 5.2±0.2a,b | 863±380a | 168±78a,b | 14.0±1.5a | 12.4±6.8e | 110±37a | 1.2±0.4b |

Data are presented as mean±SD. Note that the fill volume was 2 L with the icodextrin dwell and the continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis dwell, whereas the fill volume was 1.5 L with the Carry Life UF treatments. NA, not applicable; CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis.

Significant differences are denoted.

P < 0.001 versus the continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis dwell.

P < 0.001 versus the icodextrin dwell.

P < 0.01 versus the icodextrin dwell.

P < 0.01 versus the continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis dwell.

P < 0.05 versus the continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis dwell.

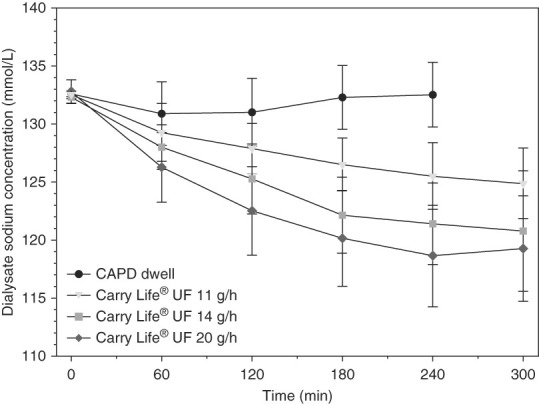

As expected, the sodium dip during the CAPD dwell was low, about 1 mmol/L, whereas the dialysate sodium concentration decreased continuously with all three steady concentration PD glucose doses (Figure 4). With higher glucose doses, the decline in dialysate sodium concentration was larger. Sodium removal was significantly higher with all three steady concentration PD glucose doses (4–5 times higher) compared with the CAPD dwell (Figure 3D, Table 3). Sodium removal tended to increase with increasing steady concentration PD glucose doses, but compared with the differences with the CAPD dwell, the differences were small because of the more pronounced decline in dialysate sodium with the higher steady concentration PD glucose doses. The calculated sodium concentration in the ultrafiltration volumes was similar in all four clinical investigation sessions (Figure 3E).

Figure 4.

Dialysate sodium concentration only had a small initial decline during the 2.5% dextrose CAPD dwell but decreased continuously during the three steady concentration PD treatments. Data are presented as mean±SD.

The preceding dwell with the 2 L icodextrin-based solution had a duration of 12.1±1.0 hours. The ultrafiltration rate with icodextrin was significantly lower compared with the steady concentration PD sessions, but owing to the longer duration, the total ultrafiltration volume was similar with icodextrin compared with the steady concentration PD sessions (Table 3). Total sodium removal was also similar with icodextrin compared with the steady concentration PD sessions. Owing to the longer duration of the icodextrin dwell, the albumin loss was significantly larger than during the steady concentration PD sessions (Table 3).

Removal of other solutes are presented in Table 4. As expected, the removed amounts of the solutes not present in the fresh dialysis fluid were to a large extent related to the drained volume. Calcium removal was markedly increased with the steady concentration PD sessions.

Table 4.

Removal of creatinine, urea, potassium, calcium, and phosphate with the overnight icodextrin dwell, the continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis dwell, and the three different glucose doses of the steady concentration peritoneal dialysis treatments

| Treatment | Creatinine Removal, mg/Treatment | Urea Removal, mg/Treatment | Potassium Removal, mmol/Treatment | Calcium Removal, mg/Treatment | Phosphate Removal, mg/Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overnight icodextrin dwell (n=8) | 199±59a | 3964±1081a | 10.8±1.8a | 4±18 | 503±95a |

| CAPD dwell with 2.5% dextrose (n=8) | 123±36b | 2943±841b | 7.8±1.1b | 13±13 | 285±66b |

| Carry Life UF 11 g/h (n=8) | 131±35b | 2943±721b | 7.4±0.7b | 36±11a,b | 285±76b |

| Carry Life UF 14 g/h (n=8) | 139±32b | 3003±961b | 8.1±1.9b | 38±15a,b | 294±104b |

| Carry Life UF 20 g/h (n=8) | 152±43b,c | 3243±1141b | 8.3±1.4b | 42±16a,b | 323±66b |

Data are presented as mean±SD. Note that the fill volume was 2 L with the icodextrin dwell and the continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis dwell, whereas the fill volume was 1.5 L with the Carry Life UF treatments. Removal of solutes was measured as mmol/treatment and was recalculated as mg/treatment for creatinine, urea, calcium, and phosphate using the following molecular weights: creatinine 113.12, urea 60.06, calcium 40.078, and phosphate 94.971. CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis.

Significant differences are denoted.

P < 0.001 versus the continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis dwell.

P < 0.001 versus the icodextrin dwell.

P < 0.05 versus the continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis dwell.

Discussion

Although volume management to achieve euvolemia is considered as a key component of PD prescription,23–25 volume overload is still very common in patients treated with PD. A prevalence of about 50% or more was found in recent large studies using multifrequency bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy to assess fluid status,16,17 demonstrating that present therapies, such as hypertonic dextrose PD solutions, icodextrin, and automated PD (APD), are insufficient in achieving euvolemia. Severe volume overload was associated with both increased mortality and increased transfer rate to hemodialysis in several studies.5,15,16,18,23,26 Thus, novel, innovative therapeutic options are needed to improve the management of volume overload in PD.

This study showed a significant increase in ultrafiltration rates and in sodium removal with the three steady concentration PD treatments compared with the 2.5% dextrose CAPD dwell. For the steady concentration PD 11 g/h glucose dose, the glucose absorption was similar to the 2.5% dextrose CAPD dwell, resulting in much higher glucose ultrafiltration efficiency for the steady concentration PD 11 g/h glucose treatment. The glucose absorption was increased during the two steady concentration PD treatments with the higher glucose doses (14 and 20 g/h) compared with the 2.5% dextrose CAPD dwell. However, the glucose ultrafiltration efficiency was significantly increased with all steady concentration PD glucose doses, but was highest with the 11 g/h glucose dose. The study by Pérez-Díaz et al. mainly used a 20 g/h glucose dose that resulted in a markedly increased ultrafiltration.20 However, glucose absorption was not reported in that study. It is important to note that the participants in the study had quite fast peritoneal solute transfer rates and consequentially were prone to volume overload;26–28 hence, steady concentration PD may be particularly useful in this patient group.

Compared with the icodextrin dwell preceding each session, steady concentration PD achieved similar total ultrafiltration volume and sodium removal, but in a much shorter period. As a consequence of the shorter treatment period, the albumin loss was much lower during the steady concentration PD treatments.

Interestingly, sodium removal was quite effective using steady concentration PD. In addition to the convective sodium removal accompanying the ultrafiltration through the small pore system,29 the high ultrafiltration through the ultrasmall pores (the aquaporins) resulted in marked dilution of the dialysate sodium concentration, in turn leading to an increased diffusive removal of sodium. Therefore, steady concentration PD allows for a more efficient sodium diffusion during the treatment compared with standard PD methods. The increased sodium removal with steady concentration PD enables a better balance between ultrafiltration volume and sodium removal than with APD where sodium sieving is pronounced, and the relatively short cycles do not allow for much diffusive removal of sodium before fresh dialysis fluid (with a higher sodium concentration) is infused in the next cycle. Therefore, APD is relatively inefficient for sodium removal compared with CAPD30,31 and theoretically also compared with steady concentration PD. Low sodium and fluid removal has been reported to be independently associated with poor clinical outcome.32 Sodium accumulation may lead to volume overload, and experimental studies suggest that sodium per se may exert direct toxicity on the peritoneal membrane by inducing local inflammation and angiogenesis.33

Calcium balance in PD is mainly determined by two factors: (1) the dialysate to plasma concentration difference and (2) the net ultrafiltration.34,35 As the calcium concentration in the PD solution used in this study was 2.5 mEq/L, it is close to the ionized plasma calcium concentration, and calcium balance will almost entirely be dependent on net ultrafiltration.34,35 Thus, when using steady concentration PD and a PD solution with a 2.5 mEq/L calcium concentration, a markedly negative calcium balance will be expected. If this is considered problematic for a given patient, a glucose solution with a higher calcium concentration should be prescribed.

This study is the first detailed clinical kinetic study to investigate the glucose ultrafiltration efficiency of steady concentration PD using different glucose doses. There are two previous theoretical simulations of steady concentration PD.21,22 In 2019, Braide presented theoretical simulations of steady concentration PD,21 which, compared with our study, resulted in longer time to achieve relatively stable dialysate glucose levels and also in markedly higher ultrafiltration rates. This is likely explained by the use of a higher initial fill volume and glucose concentration, as well as a slower peritoneal solute transfer rate and hence reduced glucose absorption. More similar to our study, Lee et al. presented computer simulations of steady concentration PD, using both 1.5% and 2.5% dextrose solutions, for patients with faster peritoneal solute transfer rates.22 However, they used a fill volume of 2 L for the modeling.

For the higher glucose doses in this study, ultrafiltration did not increase as expected from the model, and the glucose ultrafiltration efficiency was the highest with the 11 g/h glucose dose steady concentration PD treatment. The reason for the decrease in glucose ultrafiltration efficiency with higher doses of steady concentration PD is not completely clear, but there are several potential explanations for this. First, the pronounced ultrafiltration through the aquaporin pathway results in marked dilution of the dialysate sodium concentration, which results in loss of the osmotic force from sodium.29,36 Second, the hourly drain undertaken to avoid overfill will drain more glucose in the sessions with higher glucose doses. One may also speculate that the initial glucose absorption into the peritoneal capillaries results in local hyperglycemia in the peritoneal capillaries depending on the glucose concentration in the dialysate, resulting in a more pronounced local capillary hyperglycemia with higher glucose doses. This will result in a decreased glucose gradient between dialysate and plasma and thus in a lower glucose ultrafiltration efficiency.

As this was a pilot study, we used a fill volume of 1.5 L to avoid potential overfill; furthermore, a small volume of dialysate was drained hourly. The ultrafiltration volume was not excessive even with the 20 g/h glucose dose and a fill volume of 2 L is likely safe to use in patients with poor ultrafiltration and relatively fast peritoneal solute transfer rates. However, before studies are performed in patients with slower peritoneal solute transfer rates, and hence slower glucose absorption, some caution is needed when using steady concentration PD in these patients.

Regarding its clinical application, the frequency and period of steady concentration PD treatments will depend on the individual characteristics of patients treated with PD with volume overload to achieve euvolemia. For patients treated with CAPD, it could replace one exchange per day. Furthermore, steady concentration PD may theoretically also be useful in conjunction with APD, where relatively rapid cycling during APD results in sodium sieving and inefficient sodium removal in relation to the fluid removal.30,31 In such cases, adding a steady concentration PD treatment before or after the APD treatment would likely reduce the need for hypertonic dextrose solutions during APD. Furthermore, clinical studies comparing steady concentration PD with APD, as well as investigating the sustainability of the effects on ultrafiltration, are clearly needed.

As this study was a short-time “proof-of-concept” study, it has some limitations. First, we only included a small group of patients with relatively fast peritoneal solute transfer rates. The results may therefore not be representative for patients with slower peritoneal solute transfer rates. Second, we chose a single PD dwell for comparison of ultrafiltration and peritoneal solute transfer rates. The sustainability of the effects was therefore not evaluated; moreover, the comparison to APD treatment is theoretical. Furthermore, fluid status was not assessed in the patients, and it is possible that the results differ between patients with different degrees of volume overload. Pérez-Díaz et al. reported that the ultrafiltration with steady concentration PD correlated with the degree of fluid overload.20 Our study also has certain strengths. All participants were able to undergo all four treatment procedures, which were carefully standardized. Furthermore, frequent measurements of solute concentrations and fluid removal were performed, and the results were quite consistent in all participants.

In summary, compared with a 2.5% dextrose CAPD dwell, steady concentration PD performed with the Carry Life UF device resulted in higher ultrafiltration rates due to a maintained dialysate-to-plasma glucose gradient during the entire treatment; a more efficient use of glucose as an osmotic agent, shown as an increased ultrafiltration volume per gram glucose absorbed (glucose ultrafiltration efficiency); and a greater sodium removal due to high convective sodium removal in addition to a decreased intraperitoneal sodium concentration and hence an increased sodium diffusion. Steady concentration PD performed with the Carry Life UF system may be a feasible way to improve the quality of care of patients treated with PD by enabling higher ultrafiltration rates and increased sodium removal at a lower metabolic cost.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Triomed AB. Carry Life is a registered trademark owned by Triomed AB. The authors thank all participants and nurses involved in the study at the three centers. Without their participation, the study would not have been possible.

Footnotes

See related editorial, “Emerging Approaches for Optimizing Fluid Management with Peritoneal Dialysis: Going Steady,” on pages 148–150.

Disclosures

O. Carlsson and C. De Leon report employment with Triomed AB. J. Hegbrant reports employment with JBA Medical AB; consultancy for Triomed AB; ownership interest in Diaverum AB, LundaTec AB, NorrDia AB, Redsense Medical AB, and Triomed AB; and advisory or leadership roles for Board of Directors of NorrDia AB and Redsense Medical AB. O. Heimbürger reports research funding from AstraZeneca, Baxter, and Triomed; honoraria from AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Fresenius Medical Care, and Vifor for presentations at company-organized courses; speakers bureau for AstraZeneca; and other interests or relationships as Secretary of Swedish Society of Renal Medicine (2021); and role on Editorial Boards of Blood Purification, Clinical Nephrology, Peritoneal Dialysis International, and Turkish Journal of Nephrology. G. Martus reports research funding from The Swedish Kidney Foundation to Lunds University and from The Swedish Foundation for Kidney Disease to Lunds University and other interests or relationships from Triomed AB (Lund, Sweden) as a clinical study principal investigator. M. Wilkie reports consultancy for Triomed, research funding from Baxter, honoraria from Baxter and Fresenius, speakers bureau for Baxter, and other interests or relationships with International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Ola Carlsson, Charlotte De Leon, Jörgen Hegbrant, Martin Wilkie.

Data curation: Ola Carlsson.

Formal analysis: Ola Carlsson.

Investigation: Olof Heimbürger, Ann-Cathrine Johansson, Giedre Martus.

Methodology: Jörgen Hegbrant, Martin Wilkie.

Writing – original draft: Olof Heimbürger.

Writing – review & editing: Ola Carlsson, Charlotte De Leon, Jörgen Hegbrant, Olof Heimbürger, Martin Wilkie.

Data Sharing Statement

Data generated in this study can be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Fresenius Medical Care AG & Co. KGaA. Fresenius Medical Care Annual Report 2021 Table 2.20, page 38. 2021. Accessed November 7, 2023. https://www.freseniusmedicalcare.com/fileadmin/data/com/pdf/Media_Center/Publications/Annual_Reports/FME_Annual_Report_2021_EN.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perl J Davies SJ Lambie M, et al. The peritoneal dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (PDOPPS): unifying efforts to inform practice and improve global outcomes in peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2016;36(3):297–307. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2014.00288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrotra R, Devuyst O, Davies SJ, Johnson DW. The current state of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(11):3238–3252. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016010112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng JK Kwan BC Chow KM, et al. Asymptomatic fluid overload predicts survival and cardiovascular event in incident Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vrtovsnik F Verger C Van Biesen W, et al. The impact of volume overload on technique failure in incident peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(2):570–577. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfz175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambie M Zhao J McCullough K, et al. Variation in peritoneal dialysis time on therapy by country: results from the peritoneal dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17(6):861–871. doi: 10.2215/CJN.16341221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies SJ Brown EA Reigel W, et al. What is the link between poor ultrafiltration and increased mortality in anuric patients on automated peritoneal dialysis? Analysis of data from EAPOS. Perit Dial Int. 2006;26(4):458–465. doi: 10.1177/089686080602600410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies SJ, Brown EA. EAPOS: what have we learned? Perit Dial Int. 2007;27(2):131–135. doi: 10.1177/089686080702700205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang AY Sanderson JE Sea MM, et al. Handgrip strength, but not other nutrition parameters, predicts circulatory congestion in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(10):3372–3379. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heimbürger O, Waniewski J, Werynski A, Lindholm B. A quantitative description of solute and fluid transport during peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int. 1992;41(5):1320–1332. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burkart J. Metabolic consequences of peritoneal dialysis. Semin Dial. 2004;17(6):498–504. doi: 10.1111/j.0894-0959.2004.17610.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JT Chang TI Kim DK, et al. Metabolic syndrome predicts mortality in non-diabetic patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. Feb 2010;25(2):599–604. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heimbürger O. Special problems in caring for patients on peritoneal dialysis. In: Core Concepts in Dialysis and Continuous Therapies, Magee CC, Tucker JK, Singh AK, eds. Springer; 2016:155–167. Chapter 12. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-7657-4_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo WK. Metabolic syndrome and obesity in peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2016;35(1):10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.krcp.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ronco C Verger C Crepaldi C, et al. Baseline hydration status in incident peritoneal dialysis patients: the initiative of patient outcomes in dialysis (IPOD-PD study). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(5):849–858. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Biesen W Verger C Heaf J, et al. Evolution over time of volume status and PD-related practice patterns in an incident peritoneal dialysis cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(6):882–893. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11590918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Biesen W Williams JD Covic AC, et al. Fluid status in peritoneal dialysis patients: the European Body Composition Monitoring (EuroBCM) study cohort. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo Q, Yi C, Li J, Wu X, Yang X, Yu X. Prevalence and risk factors of fluid overload in Southern Chinese continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwan BC Szeto CC Chow KM, et al. Bioimpedance spectroscopy for the detection of fluid overload in Chinese peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 2014;34(4):409–416. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2013.00066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pérez-Díaz V Perez-Escudero A Sanz-Ballesteros S, et al. A new method to increase ultrafiltration in peritoneal dialysis: steady concentration peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2016;36(5):555–561. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2016.00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braide M. Steady concentration PD (SCPD)-A new concept with interesting opportunities. Perit Dial Int. 2019;39(6):496–501. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2018.00265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee KJ, Shin DA, Lee HS, Lee JC. Computer simulations of steady concentration peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2020;40(1):76–83. doi: 10.1177/0896860819878635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang AY, Dong J, Xu X, Davies S. Volume management as a key dimension of a high-quality PD prescription. Perit Dial Int. 2020;40(3):282–292. doi: 10.1177/0896860819895365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown EA Blake PG Boudville N, et al. International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis practice recommendations: prescribing high-quality goal-directed peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2020;40(3):244–253. doi: 10.1177/0896860819895364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teitelbaum I Glickman J Neu A, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2020 ISPD practice recommendations for prescribing high-quality goal-directed peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(2):157–171. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heimbürger O, Waniewski J, Werynski A, Tranaeus A, Lindholm B. Peritoneal transport in CAPD patients with permanent loss of ultrafiltration capacity. Kidney Int. 1990;38(3):495–506. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Biesen W Heimburger O Krediet R, et al. Evaluation of peritoneal membrane characteristics: clinical advice for prescription management by the ERBP working group. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(7):2052–2062. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morelle J Stachowska-Pietka J Oberg C, et al. ISPD recommendations for the evaluation of peritoneal membrane dysfunction in adults: classification, measurement, interpretation and rationale for intervention. Perit Dial Int. 2021;41(4):352–372. doi: 10.1177/0896860820982218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devuyst O, Rippe B. Water transport across the peritoneal membrane. Kidney Int. 2014;85(4):750–758. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borrelli S La Milia V De Nicola L, et al. Sodium removal by peritoneal dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nephrol. 2019;32(2):231–239. doi: 10.1007/s40620-018-0507-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tangwonglert T, Davenport A. Peritoneal sodium removal compared to glucose absorption in peritoneal dialysis patients treated by continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and automated peritoneal dialysis with and without a daytime exchange. Ther Apher Dial. 2021;25(5):654–662. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.13619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ates K Nergizoglu G Keven K, et al. Effect of fluid and sodium removal on mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2001;60(2):767–776. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060002767.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borrelli S De Nicola L Minutolo R, et al. Sodium toxicity in peritoneal dialysis: mechanisms and “solutions.” J Nephrol. 2020;33(1):59–68. doi: 10.1007/s40620-019-00673-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montenegro J, Saracho R, Aguirre R, Martinez I. Calcium mass transfer in CAPD: the role of convective transport. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1993;8(11):1234–1236. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a092339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simonsen O, Venturoli D, Wieslander A, Carlsson O, Rippe B. Mass transfer of calcium across the peritoneal membrane at three different peritoneal dialysis fluid Ca2+ and glucose concentrations. Kidney Int. 2003;64(1):208–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00055.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies S Haraldsson B Vrtovsnik F, et al. Single-dwell treatment with a low-sodium solution in hypertensive peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 2020;40(5):446–454. doi: 10.1177/0896860820924136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated in this study can be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.