Abstract

This work describes the unprecedented intramolecular cyclization occurring in a set of α-azido-ω-isocyanides in the presence of catalytic amounts of sodium azide. These species yield the tricyclic cyanamides [1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-5(4H)-carbonitriles, whereas in the presence of an excess of the same reagent, the azido-isocyanides convert into the respective C-substituted tetrazoles through a [3 + 2] cycloaddition between the cyano group of the intermediate cyanamides and the azide anion. The formation of tricyclic cyanamides has been examined by experimental and computational means. The computational study discloses the intermediacy of a long-lived N-cyanoamide anion, detected by NMR monitoring of the experiments, subsequently converting into the final cyanamide in the rate-determining step. The chemical behavior of these azido-isocyanides endowed with an aryl-triazolyl linker has been compared with that of a structurally identical azido-cyanide isomer, experiencing a conventional intramolecular [3 + 2] cycloaddition between its azido and cyanide functionalities. The synthetic procedures described herein constitute metal-free approaches to novel complex heterocyclic systems, such as [1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxalines and 9H-benzo[f]tetrazolo[1,5-d][1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a][1,4]diazepines.

Introduction

Isocyanides are versatile building blocks in organic chemistry.1 The unique properties of isocyanides come from their formally divalent carbon, which endow them with the ability to react with nucleophiles and electrophiles yielding respective α-adducts.2 Isocyanides have been extensively used in multicomponent reactions3−5 and transition-metal-catalyzed insertion processes.6−8 Azides are also valuable intermediates in organic synthesis.9 They have found new applications in peptide chemistry, combinatorial chemistry, and heterocyclic synthesis.10 Recently, the Staudinger ligation protocol based on the reactivity of azides with phosphanes has found a relevant place in the field of bioorthogonal chemistry.11

The inclusion of both isocyanide and azide functionalities in the same molecule allows to combine the reactivity of these two groups in an orthogonal manner. A good example is the tandem Ugi–Click sequence, useful to generate routes to complex heterocycles.12−14 Within this type of bifunctional compounds, 1-azido-2-isocyanoarenes are the most studied. Tungsten, molybdenum, chromium, ruthenium, and platinum complexes with 1-azido-2-isocyanoarenes as ligands have been used to prepare benzimidazole-derived carbenes.15−18 The reaction of 1-azido-2-isocyanoarenes with phenylacetaldehyde/DBU and further treatment with the Togni reagent yields [1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxalines.19 Benzimidazoles can also be synthesized from 1-azido-2-isocyanoarenes and diphenyl phosphine in the presence of manganese(II) acetate20 or by reaction with diazonium salts.20

Following our report on an easy entry into heterocyclic building blocks for drug discovery,21 we envisioned that a similar synthetic methodology could give us access to new scaffolds endowed with isocyanide and azide functionalities adequately placed for reacting one another in an intramolecular way, thus yielding complex nitrogenated heterocycles. To our knowledge, there is only one reported example of azido-isocyanides in which both functional groups participate in metal-free intramolecular reactions, the intramolecular cyclization of 2-[1-azidobenzyl]-1-isocyanobenzene in the presence of sodium hydride to give 4-phenylquinazoline.22 In order to discover new intramolecular cyclizations involving both functional groups, we designed azido-isocyanides 1 with an aryl-triazolyl moiety as the linker of both functionalities (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Putative Reaction Products Resulting from Alternative Intramolecular [3 + 2] or [3 + 1] Cyclizations of 1.

At the start of the present investigations, we envisaged two putative reaction paths between the azido and isocyano functions of compounds 1 (Scheme 1), either a [3 + 2] cyclization to give presumably unstable carbenes 2 or an alternative [3 + 1] cyclization by α-addition of the azido group to the carbon atom of the isocyanide to give fused triazetimines 3 or cyclic carbodiimides 4 by further N2 extrusion. These two reaction paths are unprecedented, as well as its reaction intermediates and products.

Before carrying out the synthetic experiments, we performed an exploratory computational study for testing the ability of compound 1a (R = H, Scheme 1) to undergo those cyclizations. The results of the computations showed that carbene 2a is highly unstable and we failed in all the attempts to locate the transition structure of the intramolecular [3 + 2] process. However, the alternative [3 + 1] cyclization to give 3a and its subsequent transformation into the carbodiimide 4a by loss of nitrogen seem to be feasible provided the reaction is conducted under strong thermal conditions (see the Supporting Information).

Herein, we disclose our results on the synthesis of azido-isocyanides 1 which proved to be not so simple as anticipated and that laterally led to novel complex heterocyclic systems.

Results and Discussion

The route toward azido-isocyanides 1 started with the synthesis of intermediates 7a–d by the reaction of 1-azido-2-isocyanoarenes 5a–d(19) with the α-ketophosphorane 6 (Table 1). This methodology for preparing 1,2,3-triazoles, originally described by Harvey,23 and L’Abbé,24 is based on the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of the azido group to the double bond of the betainic form of 6 and further elimination of triphenylphosphine oxide. By using this procedure, the resulting 1,5-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles 7a–d were obtained in medium to good yields (Table 1).

Table 1. Synthesis of 5-Chloromethyltriazoles 7 from 1-Azido-2-isocyanoarenes 5.

| entry | compound | R1 | R2 | yield (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7a | H | H | 55 |

| 2 | 7b | Me | Me | 99 |

| 3 | 7c | Me | H | 89 |

| 4 | 7d | Cl | Me | 95 |

After isolation by column chromatography.

Obviously we expected that the azido-isocyanide 1b (Scheme 2) would be readily available from the 5-chloromethyl triazole 7b by chloride substitution with the azido anion.10 However, when 7b was treated with sodium azide in dimethylformamide (DMF) at 60 °C for 24 h, thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis (silica gel, 1:2 AcOEt/hexane) showed the formation of a new main product but also apparently a residual spot of starting material. Hence, the reaction mixture was further stirred at 80 °C for an additional period of 48 h. Even though the conversion seemed still uncomplete by TLC, we proceeded to isolate the two species (work-up consisting of water addition and further extraction with AcOEt). The less polar compound turned out to be not the starting material but the pursued azidomethyl triazole 1b. Surprisingly, the 13C NMR spectrum of the second, more polar species showed the disappearance of the peak around 170 ppm attributable to the isocyanide carbon atom (172.2 ppm in 7b) and the rise of a new quaternary peak at 112.9 ppm. In its infrared (IR) spectrum, the lack of the typical bands assignable to the isocyanide and azide functions close to 2100 cm–1 as well as the appearance of a band at 2220 cm–1 gave us a first indication of the formation of a cyanamide fragment at the expense of the azido and isocyano groups, a hint that was confirmed by the unequivocal structural determination of this second product as 8b with the aid of X-ray crystallography (Scheme 2 and Figure 1).

Scheme 2. Thermal Treatment of 7b in the Presence of NaN3 Gives a Mixture of 1b and the Unexpected 8b.

Figure 1.

X-ray structure of the cyanamide 8b.

Afterward, under smoother reaction conditions (treatment of 7b with sodium azide in DMF at 25 °C), the 5-azidomethyl triazole 1b was obtained in 93% yield (Table 2, entry 2). This reaction is general for the 5-chloromethyltriazoles 7a–d, and thus, the azido-isocyanides 1a–d were obtained in yields ranging 52–93% (Table 2).

Table 2. Conversion of 5-Chloromethyltriazoles 7a–d into 5-Azidomethyltriazoles 1a–d.

| entry | compound | R1 | R2 | yield (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a | H | H | 60 |

| 2 | 1b | Me | Me | 93 |

| 3 | 1c | Me | H | 91 |

| 4 | 1d | Cl | Me | 52 |

After isolation by column chromatography.

Next, we studied the serendipitous formation of cyanamide 8b and the role of sodium azide in that process (Table 3). First, we checked the thermal stability of azido-isocyanide 1b by heating in DMF solution at 120 °C for 48 h. Under these conditions, the starting material was recovered unaltered (Table 3, entry 1), thus discarding our previous expectations summarized in Scheme 1. Afterward, we reacted 1b with one equivalent of sodium chloride, a secondary product in the reaction of 7b with sodium azide, in DMF at 60–80 °C for 48 h. Once again, no reaction took place (Table 3, entry 2). We conducted three more experiments in the presence of 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 equiv of sodium azide, thus obtaining cyanamide 8b in yields ranging 34–67% (Table 3, entries 3–5). These assays not only confirmed the key role of sodium azide in the formation of cyanamide 8b but also the advantage of using sub-stoichiometric amounts of this reagent to maximize the yield of the conversion 1b → 8b.

Table 3. Conversion of 5-Azidomethyltriazole 1b into Cyanamide 8b under Different Reaction Conditions.

| entry | reagent | equiv | T (°C) | t (h) | yield (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 120 | 48 | |||

| 2 | NaCl | 1 | 60/80 | 24/24 | |

| 3 | NaN3 | 0.5 | 80 | 48 | 67 |

| 4 | NaN3 | 1.0 | 80 | 48 | 46 |

| 5 | NaN3 | 1.5 | 80 | 48 | 34 |

After isolation by column chromatography.

To gain further insights into this process, we monitored the reaction of 1b in the presence of 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 equiv of sodium azide by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 2, Scheme 3, and Table 4). In the presence of 0.5 equiv of NaN3 (DMF-d7, 80 °C) the cyanamide 8b is neatly apparent in the reaction mixture (blue peaks) after 48 h (Figure 2). However, resonances for two new products also appear in this spectrum (red and green peaks). The red peaks weaken over time and totally disappeared after 7 days. These peaks were assigned to a long-lived intermediate (LLI) prior to the formation of 8b (Scheme 3). Remarkably, the resonances of the aromatic protons of LLI are considerably shifted to lower chemical shifts compared to those of 1b and 8b. The green-colored signals increase over time and become the most intense ones after 7 days (Figure 2 and Table 4, entry 2).

Figure 2.

1H NMR (400 MHz) monitoring of the reaction of 5-azidomethyltriazole 1b (black peaks) with NaN3 (0.5 equiv) in DMF-d7 at 80 °C. Color code: 1b (black), LLI (red), 8b (blue), and 9b (green). (*) Solvent residual peaks and (●) dichloromethane.

Scheme 3. Transformation of 5-Azidomethyltriazole 1b into 8b and 9b in the Presence of Sodium NaN3.

Table 4. Conversion Rates of 1b in the Presence of Different Amounts of NaN3 (DMF-d7, 80 °C) and Ratios of 8b and 9ba.

| entry | NaN3 (equiv) | t | conv. 1b (%)b | 8b/9b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.5 | 24 h | 52 | 86:14 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 7 d | 87 | 41:59 |

| 3 | 1.0 | 24 h | 65 | 72:27 |

| 4 | 1.0 | 7 d | 95 | 12:88 |

| 5 | 1.5 | 24 h | 73 | 66:33 |

| 6 | 1.5 | 7 d | >95 | <5:>95 |

Obtained from the 1H NMR spectra (400 MHz).

±5% of error.

These green-colored signals were assigned to the N-2 tautomer of the tetrazole 9b (see below), which presumably would form through a 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition between the azide anion and the cyano group of 8b followed by protonation.25,26 According to this hypothesis, the proportion of tetrazole 9b in the mixture increases when the reaction is conducted with greater amounts of sodium azide (Table 4, entries 3–5). In fact, 9b was the exclusive reaction product after 7 days in the presence of 1.5 equiv of this reagent (Table 4, entry 6) (for a complete picture of the three monitoring experiments see Figures S3–S5 in the Supporting Information).

Two additional experiments confirmed that tetrazole 9b formed by the reaction of 8b with NaN3 and not from a common precursor of both species 8b and 9b. Thus, 8b was heated at 80 °C in DMF-d7 in either lack or presence of sodium azide (1.0 equiv). In the first experiment, 8b was recovered unaltered, whereas in the second one tetrazole 9b quantitatively formed. At this point, we wondered why we neither detect 9b in the reaction media nor isolated it when conducting the reaction in a flask-scale (Scheme 2). We reasoned that due to the high acidity of tetrazole derivatives, with pKa values around 5,27,28 and without an acidic work-up (see above), 9b should remain in the aqueous phase in the form of its conjugated base, not being transferred into the organic phase and thus avoiding its detection in the TLC analyses of this phase.

The identity of 9b was confirmed by 2D NMR (HMBC, HSQC and NOESY, see the Supporting Information). Moreover, computational methods, combined with the experimental NMR data, allowed us to determine the tautomeric form of the tetrazole ring, N-1 or N-2, present in its DMSO-d6 solution (Scheme 3).29 Thus, the 1H and 13C NMR data of 9b were compared with those calculated from the corresponding geometry optimized structures of both tautomeric forms (Supporting Information).30 The best fit between theoretical and experimental data was found for the N-2 tautomer and the most revealing information is the chemical shift of the carbon atom at the tetrazole ring, 164.4 ppm (calculated) and 163.6 ppm (experimental), far enough from the calculated value for the N-1 tautomer, 155.3 ppm.31 Moreover, the observed chemical shift of this carbon atom agrees well with those found in the literature for 2H-tetrazole derivatives.32 Nevertheless, we cannot discard a fast equilibrium between the N-1 and N-2 tautomers with the N-2 one as the main component.33 In fact, evidence of fast proton exchange is revealed by the 1H NMR spectra, in which the tetrazole proton shows as a broad signal (9c) or was not observed (9a–b and 9d).

With all these data in our hands, the synthesis of cyanamides 8a–d and tetrazoles 9a–d was optimized. Thus, the treatment of 1a–d with a substoichiometric amount of sodium azide at 80 °C led to cyanamides 8a–d in yields ranging 25–67% (Table 5). From these data, it should be noted that the presence of a methyl group (R1) next to the isocyanide group provided the better yields. Alternatively, the same reaction in the presence of an excess of sodium azide and longer reaction times gave tetrazoles 9a–d (39–81%). Thus, either cyanamides 8a–d or tetrazoles 9a–d can be obtained from 1a–d just by tuning the amount of sodium azide. Overall, these routes allow the access to functionalized triazoloquinoxalines,34 compounds with interesting pharmacological properties,35−38 without the involvement of a transition-metal39−43 some of which are further decorated with a tetrazole ring.44

Table 5. Alternative Methodologies (A or B) for the Conversion of Compounds 1a–d into Cyanamides 8a–d and Tetrazolyl Derivatives 9a–d.

| entry | compound | R1 | R2 | yield 8 (%) | yield 9 (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | H | H | 31 | 39 |

| 2 | b | Me | Me | 67 | 80 |

| 3 | c | Me | H | 41 | 81 |

| 4 | d | Cl | Me | 25b | 57 |

After isolation by column chromatography.

The cyanamide 8d was impurified with a 10% of starting material (1d).

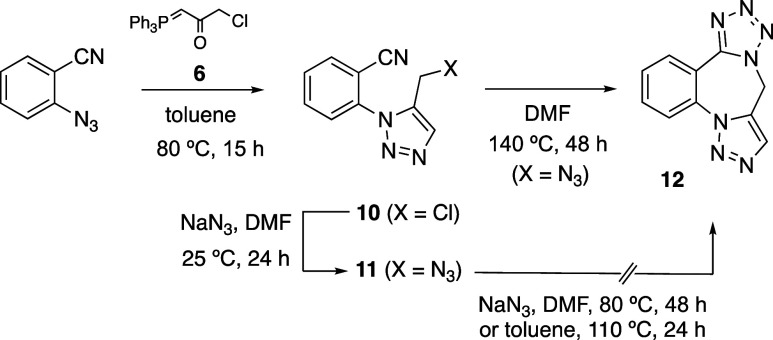

At this point, we were interested in comparing the behavior of isocyanide 1a with its isomeric cyanide (Scheme 4). Thus, 2-azidobenzonitrile was reacted with the α-ketophosphorane 6 under the usual reaction conditions to obtain the 5-chloromethyltriazole 10 in excellent yield (91%). The corresponding 5-azidomethyltriazole 11 was prepared by the reaction with sodium azide in DMF at 25 °C (82%). By contrast to what we observed for 1a, the reaction of 11 in the presence of sodium azide in DMF at 80 °C for 48 h, led to the recovery of the unchanged starting material. Heating at reflux a toluene solution of 11 for 24 h was also unsuccessful for converting this azido-cyanide into its [3 + 2] cycloadduct, the tetracyclic 1,4-diazepine 12,45−48 which however was obtained in 66% yield after heating 11 at 140 °C in DMF solution for 48 h.

Scheme 4. Three-Step Synthesis of 9H-Benzo[f]tetrazolo[1,5-d][1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a][1,4]diazepine (12) from 2-Azidobenzonitrile.

Plausible mechanistic pathways for explaining the formation of cyanamides 8 from 5-azidomethyltriazoles 1 and sodium azide are outlined in Scheme 5, with 1b as the model substrate. Initially, the addition of the azide anion to the isocyanide functionality of 1b would lead to the azidoimidoyl anion 13b.49,50 Alternatively, the [3 + 2] cycloaddition between the isocyanide moiety and the azide anion could afford the tetrazolide anion 14b.50 Both anionic species, 13b and 14b, could equilibrate through an electrocyclic ring closure/opening.51,52 The thermal activation of the experimental process (80 °C) should favor the loss of molecular nitrogen from 13b or 14b, thus leading to the carbodiimide anion 15b, which is more accurately represented as a resonance hybrid between structures 15b and the cyanamide anion 15b′. The intramolecular nucleophilic substitution of 15b with loss of the azide anion would bring about the formation of the final tricyclic cyanamide 8b. In fact, the ring fragmentation of 1-aryl-5-tetrazolyllithium derivatives at temperatures above −50 °C to give cyanamide anions has been previously reported.53,54 From this point, the formation of 9b is easily explained through a 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition between the azide anion and the cyano group of 8b with further protonation of the resulting tetrazolide anion 16b.25,26 Two experimental facts support this mechanistic proposal, (i) only substoichiometric amounts of the azide anion are necessary to form 8b from 1b, and (ii) the quantitative formation of the tetrazole 9b cannot take place unless one equivalent of azide anion is present in the reaction mixture.

Scheme 5. Putative Mechanism for the Conversion of 5-Azidomethyltriazole 1b into the Tetrazolyl Derivative 9b.

Additional alternative reaction paths leading from 13b/14b to the experimental products 8b and 9b are also summarized in Scheme 5. The intramolecular nucleophilic substitution of the azido group at the side-chain of 13b by its azidoimidoyl anionic carbon atom would afford the cyclized imidoylazide 17b, a plausible precursor of the imidoyl nitrene 18b after thermally activated loss of nitrogen. Ring expansion of this latter species by nitrene insertion would provide the cyclic carbodiimide 4b, which could also form by cyclization of 15b. A skeletal reorganization of 4b by 1,3-shift of the methylenic carbon atom could then lead to the final cyanamide 8b. Nevertheless, these latter alternative reaction pathways seem to be less plausible than that via 15b′. On the one hand, the reported formation of nitrenes from azides usually occur under FVT or photolytic conditions.55 Moreover, imidoyl nitrenes have been reported to rearrange into cyclic carbodiimides but also under photolytic conditions.55 On the other hand, the formation of cyanamides from the corresponding carbodiimides56 has exclusively been observed by photoisomerization or pyrolysis57,58

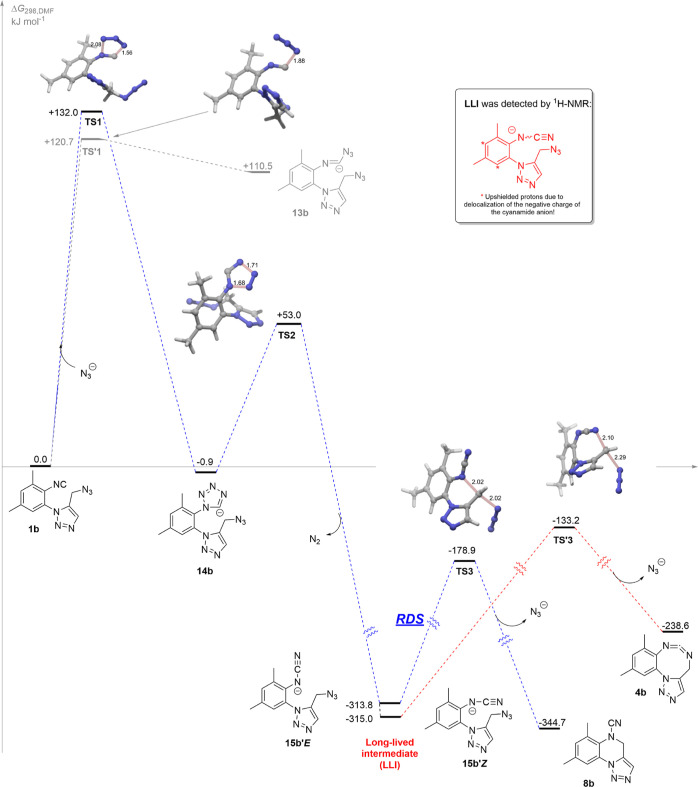

In order to get a deeper insight on the mechanism of the transformation of 1b into 8b, we conducted a computational study at the PCM(DMF)/WB97X-D/6-311++g(d,p)//PCM(DMF)/WB97X-D/6-31+g(d,p) theoretical level (Figure 3). Initially, the cycloaddition of the azide anion to 1b would lead to the tetrazolide anion 14b through the transition structure TS1 (ΔΔG = +132.0 kJ mol–1). Alternatively, 1b could transform through the less energetic TS′1 (ΔΔG = +120.7 kJ mol–1), in which only one bond between the C atom of the isocyanide and the terminal N atom of the azide anion is forming, thus leading to the azidoimidoyl anion 13b (+110.5 kJ mol–1). However, this latter scenario is reversible and thermodynamically disfavored with respect to the formation of 14b. Subsequently, 14b loses molecular nitrogen, via the easily surmountable TS2 (ΔΔG = +53.9 kJ mol–1), to the very stable cyanamide anion 15b. Two almost isoenergetic conformers were located for 15b, the rotamer 15b′Z being only 1.2 kJ mol–1 more stable than 15b′E (−313.8 kJ mol–1). Each one of these rotamers is pre-oriented to undergo an intramolecular SN2 reaction by linking either the internal N atom (15b′E) or the terminal N atom (15b′Z) of the anionic NCN fragment to the methylenic carbon atom at the side-chain, with displacement of the azide anion, respectively, leading to 8b or 4b. Thus, 15b′E would lead to the cyanamide 8b (blue dotted lines) via TS3 (ΔΔG = +134.9 kJ mol–1) in what is the rate-determining step of the whole reaction path going from 1b to 8b. We also located the higher energetic TS′3 (ΔΔG = +181.8 kJ mol–1) converting 15b′Z into the cyclic carbodiimide 4b (red dotted lines), consequently discarding the putative routes leading to 8b via 4b.

Figure 3.

Computed mechanism for the conversion of 5-azidomethyltriazole 1b into the cyanamide 8b.

The current computational study agrees well with the experimental observation of a long-lived intermediate (LLI) when the reaction was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy. In fact, the computed structures for 15b′E or 15b′Z, which possess a negative charge delocalized along the aromatic ring, are in accordance with the shifts to lower frequencies experienced by the aromatic protons of LLI, detected in an early stage of the reaction (Scheme 3 and Figure 2).

Conclusions

Herein, we have shown a novel reaction between the azide and isocyanide functions, when both are linked to an aryl-triazolyl moiety, triggered by the action of substoichiometric amounts of sodium azide. The result is an intramolecular cyclization leading to cyclic cyanamides, which could subsequently evolve to tetrazoles by a [3 + 2] cycloaddition between its cyano group and the azide anion, providing an excess of this latter reagent is present.

These processes constitute a new instance of the metal-free reactions between the azido and isocyanide functions, in this case as an approach to complex nitrogenated heterocycles. The uniqueness of this methodology lies in the catalytic role of the azide anion to promote the formation of cyanamide derivatives. Computational studies have corroborated our mechanistic proposal initiated by the addition of the azide anion to the isocyanide functionality. Moreover, the monitoring of the reaction by means of 1H NMR spectroscopy helped to postulate the respective cyanamide anions as the key intermediates of these processes. The chemical behavior of our azido-isocyanides has been also compared with that of one isomeric azido-cyanide which, in contrast, only cyclized through the well-known intramolecular [3 + 2] cycloaddition between its two functionalities. In our opinion, the present work contributes to a better understanding of the reactivity between azides and isocyanides in the absence of metals.

Experimental Section

General Methods

All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. HPLC grade solvents were nitrogen saturated and were dried and deoxygenated using an Innovative Technology Inc. Pure-Solv 400 Solvent Purification System. Column chromatography was carried out using silica gel (60 Å, 70–200 μm, SDS) as the stationary phase and TLC was performed on precoated silica gel on aluminum cards (0.25 mm thick, with fluorescent indicator 254 nm) and observed under UV light. All melting points were determined on a Kofler hot-plate melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer Spectrum 65 or JASCO FT/IR-4700 spectrometers, and data are quoted in wavenumbers (cm–1). The intensities of the absorption bands are indicated as vs (very strong), s (strong), m (middle), and w (weak). NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AVANCE 600 MHz or Bruker AVANCE 400 MHz instruments (for the latter, the operation frequency for 1H and 13C are 400.917 MHz and 100.82 MHz, respectively). 1H NMR chemical shifts are reported relative to Me4Si and were referenced via residual proton resonances of the corresponding deuterated solvent, whereas 13C NMR spectra are reported relative to Me4Si using the carbon signals of the deuterated solvent. Signals in the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the synthesized compounds were assigned with the aid of DEPT-135. Structural assignments were made with additional information from gCOSY, NOESY, gHSQC, and gHMBC experiments. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded on Agilent HPLC 1200/MS TOF 6220 or Agilent HPLC 1290 Infinity II/MS Q-TOF 6550 mass spectrometers with ESI sources. The preparation of α-ketophosphorane 6(23) and 1-azido-2-isocyanoarenes 5a–d(19) was carried out by experimental procedures previously described in the literature. Azides are potentially explosive, and all reactions should be carried out behind blast shields.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of 5-(Chloromethyl)-1-(2-isocyanoaryl)-1H-1,2,3-triazoles 7

To a solution of the corresponding 2-azidoisocyanobenzene 5 (1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in toluene (12 mL), the α-ketophosphorane 6 (0.353 g; 1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at 80° C in a block heater for 8 h. After complexion of the reaction, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography using 1:1 AcOEt/hexane as the eluent.

5-(Chloromethyl)-1-(2-isocyanophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (7a)

Yellow oil (120 mg, 55%); IR (solid, ATR, cm–1) ν: 2125 (m, N≡C), 1500 (m), 1445 (m), 1190 (m), 1121 (m), 724 (s), 698 (vs); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 7.90 (t, J = 0.5 Hz, 1H), 7.70–7.63 (m, 3H), 7.60–7.57 (m, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 0.5 Hz, 2H); 13C{1H} (100 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 171.5 (N≡C), 135.2 (C), 134.2 (CH), 131.9 (CH), 131.8 (C), 130.6 (CH), 129.0 (CH), 128.2 (CH), 123.8 (C), 32.0 (CH2); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C10H8ClN4 [M + H]+, 219.0432; found, 219.0432.

5-(Chloromethyl)-1-(2-isocyano-3,5-dimethylphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (7b)

Colorless prism (244 mg, 99%); mp 100–102 °C; IR (nujol, cm–1) ν: 2129 (s, N≡C), 1601 (w), 1493 (m), 1471 (m), 1442 (m), 1235 (m), 1101 (m), 986 (m), 884 (m), 855 (m), 710 (vs), 652 (m), 601 (w); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 7.88 (m, 1H), 7.34–7.33 (m, 1H), 7.20–7.19 (m, 1H), 4.56 (s, 2H), 2.50 (s, 3H), 2.44 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 172.1 (N≡C), 140.8 (C), 137.0 (C), 135.1 (C), 134.1 (CH), 133.6 (CH), 131.5 (C), 126.7 (CH), 121.1 (C), 32.1 (CH2), 21.3 (CH3), 18.9 (CH3); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C12H12ClN4 [M + H]+, 247.0745; found, 247.0753.

5-(Chloromethyl)-1-(2-isocyano-3-methylphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (7c)

Yellow prisms (207 mg, 89%); mp 91–92 °C; IR (solid, ATR, cm–1) ν: 2130 (m, N≡C), 1491 (m), 1469 (w), 1442 (w), 1235 (m), 1106 (m), 979 (m), 853 (m), 793 (s), 728 (m), 713 (vs); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 7.89 (s, 1H), 7.57–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.39 (m, 1H), 4.56 (s, 2H), 2.55 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 173.1 (N≡C), 137.5 (C), 135.1 (C), 134.1 (CH), 133.0 (CH), 131.8 (C), 129.8 (CH), 126.2 (CH), 123.8 (C), 32.0 (CH2), 19.0 (CH3); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C11H10ClN4 [M + H]+, 233.0589; found, 233.0591.

1-(3-Chloro-2-isocyano-5-methylphenyl)-5-(chloromethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (7d)

Yellow oil (254 mg, 95%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 7.88 (s, 1H), 7.57–7.56 (m, 1H), 7.31–7.30 (m, 1H), 4.58 (s, 2H), 2.49 (m, 3H), 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 175.5 (N≡C), 142.1 (C), 135.2 (C), 134.2 (CH), 132.80 (CH), 132.78 (C), 132.3 (C), 127.7 (CH), 120.5 (C), 31.9 (CH2), 21.4 (CH3); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C11H9Cl2N4 [M + H]+, 267.0199; found, 267.0190.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of 5-(Azidomethyl)-1-(2-isocyanoaryl)-1H-1,2,3-triazoles 1

To a solution of the corresponding 5-(chloromethyl)-1-(2-isocyanoaryl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole 7 (1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in DMF (16 mL) sodium azide (0.200 g; 3.00 mmol, 3.0 equiv) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 6 h at room temperature. After the complexion of the reaction, water (40 mL) was added and the reaction mixture extracted with AcOEt (3 × 25 mL). The organic layer was washed with brine (25 mL) and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. After removal of the solvent under reduced pressure, the residue was purified by column chromatography and eluted with 1:1 AcOEt/hexane to afford the desired product.

5-(Azidomethyl)-1-(2-isocyanophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (1a)

Yellow oil (118 mg, 60%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 7.90 (s, 1H), 7.70–7.62 (m, 3H), 7.57–7.55 (m, 1H), 4.43 (s, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 171.6 (N≡C), 133.9 (CH), 133.6 (C), 131.9 (CH + C), 130.7 (CH), 128.8 (CH), 128.2 (CH), 123.7 (C), 42.9 (CH2); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C10H8N7 [M + H]+, 226.0838; found, 226.0844.

5-(Azidomethyl)-1-(2-isocyano-3,5-dimethylphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (1b)

Colorless prisms (236 mg, 93%); mp 75–77 °C; IR (nujol, cm–1) ν: 2126 (vs, N≡C), 2101 (m, N3), 2077 (m, N3), 1237 (vs), 1215 (m), 1108 (m), 977 (m), 880 (s), 833 (m), 800 (m); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 7.86 (m, 1H), 7.34–7.33 (m, 1H), 7.16–7.15 (m, 1H), 4.40 (s, 2H), 2.49 (s, 3H), 2.43 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 172.2 (N≡C), 140.9 (C), 137.0 (C), 133.7 (CH), 133.53 (CH), 133.51 (C), 131.6 (C), 126.5 (CH), 121.0 (C), 42.9 (CH2), 21.3 (CH3), 18.8 (CH3); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C12H12N7 [M + H]+, 254.1149; found, 254.1145.

5-(Azidomethyl)-1-(2-isocyano-3-methylphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (1c)

Yellow prisms (218 mg, 91%); mp 60–62 °C; IR (nujol, cm–1) ν: 2125 (m, N≡C), 2090 (s, N3), 1493 (m), 1350 (m), 1256 (m), 1233 (m), 1097 (m), 980 (m), 870 (m), 804 (vs), 733 (m), 687 (w); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 7.88 (s, 1H), 7.56–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.36 (dd, J = 7.3, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 4.40 (s, 2H), 2.54 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 173.0 (N≡C), 137.5 (C), 133.8 (CH), 133.5 (C), 133.0 (CH), 131.9 (C), 129.8 (CH), 126.0 (CH), 123.7 (C), 42.8 (CH2), 19.0 (CH3); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C11H10N7 [M + H]+, 240.0992; found, 240.0986.

5-(Azidomethyl)-1-(3-chloro-2-isocyano-5-methylphenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (1d)

Colorless prisms (142 mg, 52%); mp 87–89 °C; IR (solid, ATR, cm–1) ν: 2125 (vs, N≡C), 2102 (m, N3), 2076 (m, N3), 1488 (m), 1463 (w), 1446 (m), 1238 (vs), 1206 (m), 1115 (m), 1089 (m), 1069 (w), 964 (m), 880 (s), 831 (m), 801 (m), 758 (m), 724 (m) 666 (m), 648 (m), 605 (w); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 7.88 (s, 1H), 7.56 (m, 1H), 7.28 (m, 1H), 4.44 (s, 2H), 2.49 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 175.5 (N≡C), 142.2 (C), 134.0 (CH), 133.6 (C), 132.9 (C), 132.8 (CH), 132.4 (C), 127.6 (CH), 120.4 (C), 42.9 (CH2), 21.4 (CH3); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C11H9ClN7 [M + H]+, 274.0602; found, 274.0599.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of [1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-5(4H)-carbonitriles 8

Sodium azide (0.033 g; 0.50 mmol, 0.5 equiv) was added to a solution of the corresponding 5-azidomethyl-1-(2-isocyanophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole 1 (1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in DMF (11 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C in a block heater for 48 h. After the complexion of the reaction, water (20 mL) was added, and the mixture was extracted with AcOEt (3 × 15 mL). The organic layer was then washed with water (15 mL) and dried over MgSO4. After removal of the solvent under reduced pressure, the residue was purified by column chromatography eluting with 1:1 AcOEt/hexane.

[1,2,3]Triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-5(4H)-carbonitrile (8a)

Colorless prisms (61 mg, 31%); mp 175–176 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 8.19 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.44–7.38 (m, 2H), 7.31 (ddd, J = 8.2, 6.7, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 5.11 (d, J = 0.5 Hz, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 130.1 (CH), 129.2 (CH), 126.7 (C), 125.6 (CH), 125.5 (C), 123.9 (C), 117.7 (CH), 117.0 (CH), 111.0 (C), 44.5 (CH2); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C10H8N5 [M + H]+, 198.0780; found, 198.0779.

6,8-Dimethyl-[1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-5(4H)-carbonitrile (8b)

Colorless prisms (151 mg, 67%); mp 190–192 °C; IR (solid, ATR, cm–1) ν: 2920 (m), 2852 (w), 2220 (m, CN), 1482 (vs), 1446 (m), 1369 (m), 1226 (m), 1108 (m), 985 (vs), 859 (vs), 695 (m); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 7.89 (s, 1H), 7.71 (s, 1H), 7.09–7.08 (m, 1H), 4.86 (d, J = 0.7 Hz, 2H), 2.49 (s, 3H), 2.42 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 138.4 (C), 131.9 (C), 131.8 (CH), 129.8 (CH), 127.6 (C), 127.4 (C), 122.6 (C), 116.2 (CH), 112.9 (C), 45.7 (CH2), 21.2 (CH3), 17.8 (CH3); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C12H12N5 [M + H]+, 226.1087; found, 226.1080.

6-Methyl-[1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-5(4H)-carbonitrile (8c)

Colorless prisms (87 mg, 41%); mp 149–150 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 8.08–8.06 (m, 1H), 7.72 (t, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (dm, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.90 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 2H), 2.54 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 132.2 (C), 131.2 (CH), 129.8 (CH), 127.84 (C), 127.82 (CH), 127.4 (C), 125.0 (C), 115.8 (CH), 112.7 (C), 45.7 (CH2), 18.0 (CH3); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C11H10N5 [M + H]+, 212.0931; found, 212.0937.

6-Chloro-8-methyl-[1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-5(4H)-carbonitrile (8d)

Colorless prisms (61 mg, 25%); mp 145–147 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 7.98–7.97 (m, 1H), 7.73 (t, J = 0.7 Hz, 1H), 7.31–7.30 (m, 1H), 4.93 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 2H), 2.46 (t, J = 0.7 Hz, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 139.5 (C), 130.6 (CH), 130.0 (CH), 128.5 (C), 127.6 (C), 127.5 (C), 121.5 (C), 117.0 (CH), 111.7 (C), 46.1 (CH2), 21.2 (CH3); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C11H9ClN5 [M + H]+, 246.0541; found, 246.0541.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of 5-(2H-tetrazol-5-yl)-4,5-dihydro-[1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxalines 9

To a solution of the corresponding 5-azidomethyl-1-(2-isocyanophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole 1 (1.00 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in DMF (8 mL) sodium azide (0.130 g; 2 mmol, 2.0 equiv) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C in a block heater for 7 days. After complexion of the reaction, the mixture was acidified to pH = 3–4 with an aqueous solution of 1 M HCl. Then, water (15 mL) was added and the aqueous phase extracted with AcOEt (3 × 20 mL). The organic extracts were dried with MgSO4. After removal of the solvent under reduced pressure, the residue was purified by column chromatography sequentially eluting with 9:1 chloroform/acetone, 7:3 chloroform/acetone and, finally, 4:1 chloroform/methanol.

5-(2H-Tetrazol-5-yl)-4,5-dihydro-[1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline (9a)

Colorless prisms (94 mg, 39%); mp > 300 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): δ 8.04 (dd, J = 8.0,1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (s, 1H), 7.34 (ddd, J = 8.6, 7.3, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (td, J = 7.7, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 5.25 (s, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): δ 161.4 (C), 132.0 (C), 129.7 (CH), 129.6 (C), 128.3 (CH), 123.6 (C), 121.8 (CH), 118.8 (CH), 116.4 (CH), 43.1 (CH2); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C10H7N8 [M – H]−, 239.0799; found, 239.0805.

6,8-Dimethyl-5-(2H-tetrazol-5-yl)-4,5-dihydro-[1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline (9b)

Colorless prisms (215 mg, 80%); mp 198–200 °C; IR (solid, ATR, cm–1) ν: 3208 (m, NH), 2922 (m), 1574 (m), 1478 (vs), 1437 (m), 1407 (m), 1223 (m), 1093 (m), 988 (m), 853 (m), 739 (m), 691 (m), 661 (s), 634 (s); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): δ 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.71 (m, 1H), 7.13 (m, 1H), 5.11 (s, 2H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 2.12 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): δ 163.6 (C), 135.1 (2×C), 131.2 (C), 130.6 (CH), 129.5 (CH), 129.4 (C), 128.5 (C), 114.5 (CH), 44.3 (CH2), 20.7 (CH3), 18.1 (CH3); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C12H13N8 [M + H]+, 269.1258; found, 269.1268.

6-Methyl-5-(2H-tetrazol-5-yl)-4,5-dihydro-[1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline (9c)

Colorless prisms (206 mg, 81%); mp 252–254 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): δ 16.0 (br s, 1H), 7.97 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (s, 1H), 7.49–7.41 (m, 2H), 5.27 (s, 2H), 2.18 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): δ 160.5 (C), 135.0 (C), 130.8 (C), 130.5 (CH), 130.0 (CH), 129.2 (C), 129.0 (C), 127.3 (CH), 114.8 (CH), 44.1 (CH2), 17.7 (CH3); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C11H11N8 [M + H]+, 255.1107; found, 255.1108.

6-Chloro-8-methyl-5-(2H-tetrazol-5-yl)-4,5-dihydro-[1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline (9d)

Colorless prisms (165 mg, 57%); mp > 300 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): δ 7.92 (m, 1H), 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.46–7.45 (m, 1H), 5.23 (s, 2H), 2.45 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): δ 161.8 (C), 137.7 (C), 130.9 (C), 129.9 (CH), 129.8 (C), 129.7 (C), 129.6 (CH), 127.0 (C), 116.1 (CH), 44.7 (CH2), 20.4 (CH3); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C11H10ClN8 [M + H]+, 289.0711; found, 289.0709.

Synthesis of 2-[5-(chloromethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]benzonitrile (10)

To a solution of 2-azidobenzonitrile (1.0 g, 7.7 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in toluene (40 mL) under a nitrogen-gas atmosphere was added α-ketophosphorane (6) (2.71 g, 7.7 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and the mixture was heated at 80 °C with stirring in a block heater for 15 h. After this time, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give a residue which was purified by column chromatography eluting with 7:3 AcOEt/hexane to give the title compound as a white solid after treatment with CH2Cl2/Et2O (1.53 g, 91%); mp 96–98 °C; FT-IR (solid, ATR, cm–1) ν: 2235 (w, CN), 1598 (w), 1504 (m), 1451 (m), 1258 (w), 1234 (m), 1168 (w), 1091 (m), 974 (m), 854 (m), 774 (vs), 721 (s), 698 (m), 670 (m), 649 (m); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 7.89 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (s, 1H), 7.84 (td, J = 7.9, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (td, J = 7.8, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (dd, J = 8.0, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 4.60 (s, 2H, CH2); 13C{1H} NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 137.2 (C), 135.1 (C), 134.3 (CH), 134.2 (CH), 134.1 (CH), 131.2 (CH), 128.2 (CH), 114.7 (CN), 111.3 (C), 32.0 (CH2); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C10H8ClN4 [M + H]+, 219.0432; found, 219.0436.

Synthesis of 2-[5-(Azidomethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]benzonitrile (11)

A mixture of 2-[5-(chloromethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]benzonitrile (10) (1.0 g, 4.6 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and sodium azide (0.89 g, 13.7 mmol, 3.0 equiv) in DMF (50 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. Water (100 mL) was added and the reaction mixture was extracted with AcOEt (3 × 50 mL). The organic layer was washed with brine (3 × 50 mL), dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and the solvent evaporated under reduced pressure. The obtained residue was purified by column chromatography eluting with 7:3 AcOEt/hexane to give the title compound as a yellow oil (0.85 g, 82%); FT-IR (solid, ATR, cm–1) ν: 2234 (w, CN), 2098 (s, N3), 1597 (w), 1502 (m), 1457 (m), 1345 (w), 1253 (m), 1234 (m), 1202 (w), 1114 (w), 1082 (m), 976 (m), 960 (m), 880 (w), 840 (w), 768 (vs), 700 (w), 650 (w); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 7.90–7.82 (m, 3H), 7.72 (td, J = 7.7, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.45 (s, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K): δ 137.3 (C), 134.2 (CH), 134.10 (CH), 134.07 (CH), 133.5 (C), 131.2 (CH), 128.1 (CH), 114.7 (CN), 111.1 (C), 42.7 (CH2); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C10H8N7 [M + H]+, 226.0836; found, 226.0838.

Synthesis of 9H-Benzo[f]tetrazolo[1,5-d][1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a][1,4]diazepine (12)

A solution of 2-[5-(azidomethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]benzonitrile (11) (1.0 g, 4.4 mmol) in DMF (100 mL) was heated at 140 °C in a block heater for 48 h. After warming to room temperature, the mixture was poured into iced water (150 mL). The resultant solid was filtered, dried under reduced pressure, and crystallized from ethanol to give the title compound as white prisms (0.66 g, 66%); mp 262–264 °C; IR (solid, ATR, cm–1) ν: 1614 (w), 1485 (m), 1446 (m), 1409 (w), 1264 (m), 1237 (w), 1146 (m), 1163 (w), 1096 (m), 1052 (w), 974 (m), 854 (m), 795 (m), 764 (vs), 742 (s), 695 (w), 641 (m); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): δ 8.27–8.23 (m, 2H), 8.05 (s, 1H), 7.93 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (s, 2H, CH2); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6, 298 K): δ 151.9 (C), 133.6 (C), 133.5 (CH), 133.1 (CH), 132.5 (C), 130.4 (CH), 129.7 (CH), 123.9 (CH), 114.9 (C), 39.5 (CH2); HRMS (ESI): calcd for C10H8N7 [M + H]+, 226.0836; found, 226.0837.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the MICINN (PID2020-113686GB-I00/MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) and Fundacion Seneca-CARM (project 21907/PI/22). G.C.-F. thanks Fundacion Seneca-CARM for his contract (21442/FPI/20).

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.3c00558.

Crystal data, data collection, and structure refinement for 8b; X-ray ORTEP figures; 1H NMR monitoring of the reaction of 5-azidomethyltriazole 1b with NaN3 in DMF-d7; computed structures and theoretical 13C NMR chemical shifts of both N-1 and N-2 tautomeric forms of 9b; NMR spectra of all new synthesized compounds; and computational methods and alternative mechanism initiated by an intramolecular [3 + 1] cycloaddition of the azido-isocyanide 1b (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lygin A. V.; de Meijere A. Isocyanides in the Synthesis of Nitrogen Heterocycles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9094–9124. 10.1002/anie.201000723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugi I.Isonitrile Chemistry; Academic Press: New York and London, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Dömling A.; Ugi I. Multicomponent Reactions with Isocyanides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3168–3210. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dömling A. Recent Developments in Isocyanide Based Multicomponent Reactions in Applied Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 17–89. 10.1021/cr0505728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neochoritis C. G.; Zhao T.; Dömling A. Tetrazoles via Multicomponent Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 1970–2042. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyarskiy V. P.; Bokach N. A.; Luzyanin K. V.; Kukushkin V. Y. Metal-Mediated and Metal-Catalyzed Reactions of Isocyanides. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2698–2779. 10.1021/cr500380d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B.; Xu B. Metal-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization Involving Isocyanides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1103–1123. 10.1039/c6cs00384b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giustiniano M.; Basso A.; Mercalli V.; Massarotti A.; Novellino E.; Tron G. C.; Zhu J. To Each His Own: Isonitriles for All Flavors. Functionalized Isocyanides as Valuable Tools in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1295–1357. 10.1039/c6cs00444j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scriven E. F. V.; Turnbull K. Azides: Their Preparation and Synthetic Uses. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 297–368. 10.1021/cr00084a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bräse S.; Gil C.; Knepper K.; Zimmermann V. Organic Azides: An Exploding Diversity of a Unique Class of Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5188–5240. 10.1002/anie.200400657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sletten E. M.; Bertozzi C. R. From Mechanism to Mouse: A Tale of Two Bioorthogonal Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 666–676. 10.1021/ar200148z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nenajdenko V. G.; Gulevich A. V.; Sokolova N. V.; Mironov A. V.; Balenkova E. S. Chiral Isocyanoazides: Efficient Bifunctional Reagents for Bioconjugation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 2010, 1445–1449. 10.1002/ejoc.200901326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova N. V.; Nenajdenko V. G. Azidoisocyanides, New Bifunctional Reagents for Multicomponent Reactions and Biomolecule Modifications. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2014, 50, 197–213. 10.1007/s10600-014-0914-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharova E. A.; Shmatova O. I.; Kutovaya I. V.; Khrustalev V. N.; Nenajdenko V. G. Synthesis of Macrocyclic Peptidomimetics via the Ugi-click-strategy. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 3433–3445. 10.1039/c9ob00229d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn F. E.; Langenhahn V.; Lügger T.; Pape T.; Le Van D. Template Synthesis of a Coordinated Tetracarbene Ligand with Crown Ether Topology. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3759–3763. 10.1002/anie.200462690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Figueroa A.; Kaufhold O.; Feldmann K.-O.; Hahn F. E. Synthesis of NHC Complexes by Template Controlled Cyclization of β-Functionalized Isocyanides. Dalton Trans. 2009, 9334–9342. 10.1039/b915033a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn F. E.; Langenhahn V.; Meier N.; Lügger T.; Fehlhammer W. P. Template Synthesis of Benzannulated N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands. Chem.—Eur. J. 2003, 9, 704–712. 10.1002/chem.200390079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumke A. C.; Pape T.; Kösters J.; Feldmann K.-O.; Schulte to Brinke C.; Hahn F. E. ., Metal-Template-Controlled Stabilization of β-Functionalized Isocyanides. Organometallics 2013, 32, 289–299. 10.1021/om301067v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Mao T.; Huang J.; Zhu Q. A One-Pot Synthesis of [1,2,3]Triazolo[1,5-a]Quinoxalines from 1-Azido-2-isocyanoarenes with High Bond-Forming Efficiency. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 1305–1308. 10.1039/c6cc08543a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Mao T.; Huang J.; Zhu Q. Denitrogenative Imidoyl Radical Cyclization: Synthesis of 2-Substituted Benzoimidazoles from 1-Azido-2-isocyanoarenes. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 3223–3226. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alajarin M.; Cabrera J.; Pastor A.; Villalgordo J. M. A New Modular and Flexible Approach to [1,2,3]Triazolo[1,5-a][1,4]benzodiazepines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 3495–3499. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.03.121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ezaki K.; Kobayashi K. A Novel Synthesis of Quinazolines by Cyclization of 1-(2-Isocyanophenyl)alkylideneamines Generated by the Treatment of 2-(1-Azidoalkyl)phenyl Isocyanides with NaH. Helv. Chim. Acta 2014, 97, 822–829. 10.1002/hlca.201300431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey G. R. The Reactions of Phosphorus Compounds. XII.1 A New Synthesis of 1,2,3-Triazoles and Diazo Esters from Phosphorus Ylids and Azides. J. Org. Chem. 1966, 31, 1587–1590. 10.1021/jo01343a063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ykman P.; Mathys G.; L’Abbe G.; Smets G. Reactions of vinyl azides with .alpha.-oxo phosphorus ylides. Synthesis of N1-vinyltriazoles. J. Org. Chem. 1972, 37, 3213–3216. 10.1021/jo00986a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan W. G.; Henry R. A.; Lofquist R. An Improved Synthesis of 5-Substituted Tetrazoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 3908–3911. 10.1021/ja01548a028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norris W. P. 5-Trifluoromethyltetrazole and Its Derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 1962, 27, 3248–3251. 10.1021/jo01056a062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst R. M.; Wilson K. R. Apparent Acidic Dissociation of Some 5-Aryltetrazoles. J. Org. Chem. 1957, 22, 1142–1145. 10.1021/jo01361a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McManus J. M.; Herbst R. M. Tetrazole Analogs of Amino Acids. J. Org. Chem. 1959, 24, 1643–1649. 10.1021/jo01093a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larina L. I. Tautomerism and Structure of Azoles: Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 2018, 124, 233–321. 10.1016/bs.aihch.2017.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calculation method: (GIAO,DMSO)B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p)//(PCM, DMF)wb97XD/6-31+g(d,p).

- Butler R. N.; Garvin V. C. A Study of Annular Tautomerism, Interannular Conjugation, and Methylation Reactions of ortho-Substituted-5-aryltetrazoles Using Carbon-13 and Hydrogen-1 N.M.R. Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1981, 390–393. 10.1039/p19810000390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M.; Harris R. K.; Rao R. C.; Apperley D. C.; Rodger C. A. NMR Study of Desmotropy in Irbesartan, a Tetrazole-containing Pharmaceutical Compound. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1998, 475–482. 10.1039/a708038g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trifonov R. E.; Alkorta I.; Ostrovskii V. A.; Elguero J. A Theoretical Study of the Tautomerism and Ionization of 5-Substituted NH-tetrazoles. J. Mol. Struct. 2004, 668, 123–132. 10.1016/j.theochem.2003.10.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y.-M.; Li H.-Y.; Zhang M.; Wang R.-X.; Zhou C.-G.; Ren Z.-X.; Ding M.-W. One-Pot Synthesis of [1,2,3]Triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxalin-4(5H)-ones by a Metal-Free Sequential Ugi-4CR/Alkyne–Azide Cycloaddition Reaction. Synlett 2020, 31, 73–76. 10.1055/s-0037-1610737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Morales T. G.; Ratia K.; Wang D.-S.; Gogos A.; Driver T. G.; Federle M. J. A Novel Chemical Inducer of Streptococcus Quorum Sensing Acts by Inhibiting the Pheromone-degrading Endopeptidase PepO. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 931–940. 10.1074/jbc.m117.810994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli L.; Biagi G.; Giorgi I.; Manera C.; Livi O.; Scartoni V.; Betti L.; Giannaccini G.; Trincavelli L.; Barili P. L. 1,2,3-Triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxalines: Synthesis and Binding to Benzodiazepine and Adenosine Receptors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 33, 113–122. 10.1016/s0223-5234(98)80036-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biagi G.; Giorgi I.; Livi O.; Scartoni V.; Betti L.; Giannaccini G.; Trincavelli M. L. New 1,2,3-Triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxalines: Synthesis and Binding to Benzodiazepine and Adenosine Receptors. II. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 37, 565–571. 10.1016/s0223-5234(02)01376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H. C.; Ding F.-X.; Deng Q.; Wilsie L. C.; Krsmanovic M. L.; Taggart A. K.; Carballo-Jane E.; Ren N.; Cai T.-Q.; Wu T.-J.; Wu K. K.; Cheng K.; Chen Q.; Wolff M. S.; Tong X.; Holt T. G.; Waters M. G.; Hammond M. L.; Tata J. R.; Colletti S. L. Discovery of Novel Tricyclic Full Agonists for the G-Protein-Coupled Niacin Receptor 109A with Minimized Flushing in Rats. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 2587–2602. 10.1021/jm900151e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J.; Zhou F.; Qin D.; Cai T.; Ding K.; Cai Q. Synthesis of [1,2,3]Triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxalin-4(5H)-ones through Copper-Catalyzed Tandem Reactions of N-(2-Haloaryl)propiolamides with Sodium Azide. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1262–1265. 10.1021/ol300114w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z.; Bae M.; Wu J.; Jamison T. F. Synthesis of Highly Functionalized Polycyclic Quinoxaline Derivatives Using Visible-Light Photoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 14451–14455. 10.1002/anie.201408522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Y.; He H.; Liu T.; Zhang Y.; Lu X.; Cai Q. Diversified Synthesis of 2-(4-Oxo[1,2,3]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxalin-5(4H)-yl)acetamide Derivatives through Ugi-4-CR and Copper-Catalyzed Tandem Reactions. Synthesis 2017, 49, 3863–3873. 10.1055/s-0036-1590791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Latyshev G.; Kotovshchikov Y.; Beletskaya I. P.; Lukashev N. V. Regioselective Approach to 5-Carboxy-1,2,3-triazoles Based on Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylation. Synthesis 2018, 50, 1926–1934. 10.1055/s-0036-1591896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Majeed K.; Wang L.; Liu B.; Guo Z.; Zhou F.; Zhang Q. Metal-Free Tandem Approach for Triazole-Fused Diazepinone Scaffolds via [3 + 2]Cycloaddition/C–N Coupling Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 207–222. 10.1021/acs.joc.0c02022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For applications of tetrazoles in medicinal chemistry, see:Herr R. J. , 5-Substituted-1H-tetrazoles as Carboxylic Acid Isosteres: Medicinal Chemistry and Synthetic Methods. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002, 10, 3379–3393. 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. A. S.; Clegg J. M.; Hall J. H. Synthesis of Heterocyclic Compounds from Aryl Azides. IV. Benzo-Methoxy-and Chloro-carbazoles. J. Org. Chem. 1958, 23, 524–529. 10.1021/jo01098a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garanti L.; Zecchi G. Thermochemical Behavior of o-Azidocinnamonitriles. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 4767–4769. 10.1021/jo01311a044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco R.; Garanti L.; Zecchi G. Intramolecular 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions of Aryl Azides Bearing Alkenyl, Alkynyl, and Nitrile Groups. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 1906–1909. 10.1021/jo00901a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worch M.; Wittmann V. Unexpected Formation of Complex Bridged Tetrazoles via Intramolecular 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of 1,2-O-cyanoalkylidene Derivatives of 3-Azido-3-deoxy-D-allose. Carbohydr. Res. 2008, 343, 2118–2129. 10.1016/j.carres.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaikate O.; Inthalaeng N.; Meesin J.; Kantarod K.; Pohmakotr M.; Reutrakul V.; Soorukram D.; Leowanawat P.; Kuhakarn C. Synthesis of Indolo- and Benzothieno[2,3-b]quinolines by a Cascade Cyclization of o-Alkynylisocyanobenzene Derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 15131–15144. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b02081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaikate O.; Soorukram D.; Leowanawat P.; Pohmakotr M.; Reutrakul V.; Kuhakarn C. Azide-Triggered Bicyclization of o-Alkynylisocyanobenzenes: Synthesis of Tetrazolo[1,5-a]quinolines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 2019, 7050–7057. 10.1002/ejoc.201901209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tišler M.: Some Aspects of Azido-Tetrazolo Isomerization. Synthesis, 1973; Vol. 1973, pp 123–136, 10.1055/s-1973-22145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cubero E.; Orozco M.; Luque F. J. Azidoazomethine–Tetrazole Isomerism in Solution: A Thermochemical Study. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2354–2356. 10.1021/jo971576i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer J. C.; Sheppard W. A. 1-Aryltetrazoles. Synthesis and Properties. J. Org. Chem. 1967, 32, 3580–3592. 10.1021/jo01286a064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raap R. Reactions of 1-Substituted 5-Tetrazolyllithium Compounds; Preparation of 5-Substituted 1-Methyltetrazoles. Can. J. Chem. 1971, 49, 2139–2142. 10.1139/v71-346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wentrup C. Nitrenes, Carbenes, Diradicals, and Ylides. Interconversions of Reactive Intermediates. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 393–404. 10.1021/ar700198z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simple heating of a N-benzyl-N′-allyl carbodiimide derivative affords the corresponding allyl cyanamide through a [3,3] sigmatropic rearrangement see:Yamamoto N.; Isobe M. Chem. Lett. 1994, 23, 2299–2302. 10.1246/cl.1994.2299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Nevertheless, this pathway can be completely discarded due to the structure of intermediate 4b

- Boyer J. H.; Frints P. J. A. Isomerization of Carbodiimides into Cyanamides. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968, 9, 3211–3212. 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)89526-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer J. H.; Frints P. J. A. The azomethine nitrene. I. Pyrolysis and photolysis of Δ2 1,2,4-oxadiazoline-5-ones. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1970, 7, 59–70. 10.1002/jhet.5570070109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.