Abstract

Central nervous system (CNS) accumulation of fibrillary deposits made of Amyloid β (Aβ), hyperphosphorylated Tau or α-synuclein (α-syn), present either alone or in the form of mixed pathology, characterizes the most common neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) as well as the aging brain. Compelling evidence supports that acute neurological disorders, such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and stroke, are also accompanied by increased deposition of toxic Aβ, Tau and α-syn species. While the contribution of these pathological proteins to neurodegeneration has been experimentally ascertained, the cellular and molecular mechanisms driving Aβ, Tau and α-syn-related brain damage remain to be fully clarified. In the last few years, studies have shown that Aβ, Tau and α-syn may contribute to neurodegeneration also by inducing and/or promoting blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption. These pathological proteins can affect BBB integrity either directly by affecting key BBB components such as pericytes and endothelial cells (ECs) or indirectly, by promoting brain macrophages activation and dysfunction. Here, we summarize and critically discuss key findings showing how Aβ, Tau and α-syn can contribute to BBB damage in most common NDDs, TBI and stroke. We also highlight the need for a deeper characterization of the role of these pathological proteins in the activation and dysfunction of brain macrophages, pericytes and ECs to improve diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic neurological disorders.

Keywords: Amyloid β, Tau, α-synuclein, Brain macrophages, Pericytes, Endothelial cells

Introduction

Amyloid β (Aβ), Tau and α-synuclein (α-syn) are amyloidogenic proteins forming insoluble fibrillary deposits with β-sheet structure in the brain of patients suffering from major neurodegenerative disorders (NDDs). Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most common among NDDs, is characterized by brain accumulation of extracellular Aβ aggregates known as plaques and intraneuronal Tau deposits called neurofibrillary tangles, that are also found in several other NDDs, including frontotemporal dementia, Pick's disease, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, argyrophilic grain disease as well as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a condition where neuronal loss results from repetitive blast or concussive injuries [125]. Intraneuronal and intraneuritic α-syn aggregates, referred to as Lewy bodies (LB) and Lewy neurites, are distinctive features of Parkinson's disease (PD) and LB dementia [50]. Moreover, α-syn fibrillary aggregates also accumulate in glial cytoplasmic inclusions, which are typically observed in oligodendrocyte cells in the brain of patients affected by multiple system atrophy.

Aging, genetic variants and/or environmental stressors are major risk factors for the deposition of Aβ, hyperphosphorylated Tau and α-syn aggregates, and consequently, for the onset of the associated NDDs. Moreover, acute brain injuries, such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) or ischemia, can also trigger the accumulation of these pathological proteins in the brain, potentially leading to the development of neurodegeneration [17, 25, 30, 74, 147].

Although the area affected by different proteinopathies, as well as the sites of neurodegeneration, can markedly vary among NDDs, TBI and stroke, it is worth considering that the coexistence of Aβ, Tau, and α-syn pathologies has been frequently observed in these conditions, including the LB variant of AD or the recurrent presence of tauopathy in PD and LB dementia. This suggests the possibility of a synergistic and toxic interplay of Aβ, Tau and α-syn in promoting central nervous system (CNS) damage [120].

Compelling evidence supports that the deposition of Aβ, hyperphosphorylated Tau and α-syn not only participates in neuronal damage but also in blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption, that is another main common manifestation of NDDs, TBI and stroke [11, 34, 37, 55, 130].

The BBB is a complex and finely regulated interface that protects CNS neurons by limiting the trafficking of blood components to the brain [45, 75]. In acute and chronic NDDs, it becomes more permeable to solutes, and allows an increase in lymphocyte trafficking and brain infiltration of innate immune cells [75]. Multiple rodent studies have shown that Aβ, Tau and α-syn pathology can disrupt brain vascular homeostasis either by directly interacting with BBB cell components or by promoting a neuroinflammatory state, that can severely perturb BBB permeability [11, 33, 34, 37, 77, 132]. The resulting BBB disruption can in turn contribute to brain damage by affecting brain homeostatic responses. As a representative example, cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) pathology, characterized by Aβ accumulation within cerebral blood vessels, has been correlated with cerebral atrophy and advancing cognitive deterioration and can also precipitate hemorrhagic stroke.

In this review, we summarize and discuss growing evidence supporting the hypothesis that Aβ, Tau and α-syn pathology disrupts BBB integrity in acute and chronic neurological disorders through three key cellular subtypes: brain macrophages, pericytes and endothelial cells (ECs) with the aim to open insightful perspectives for the identification of innovative disease biomarkers or therapeutic targets for these disabling conditions. Although astrocytes play a critical role in the maintenance of BBB integrity, they are outside the scope of this review.

Organization of the BBB

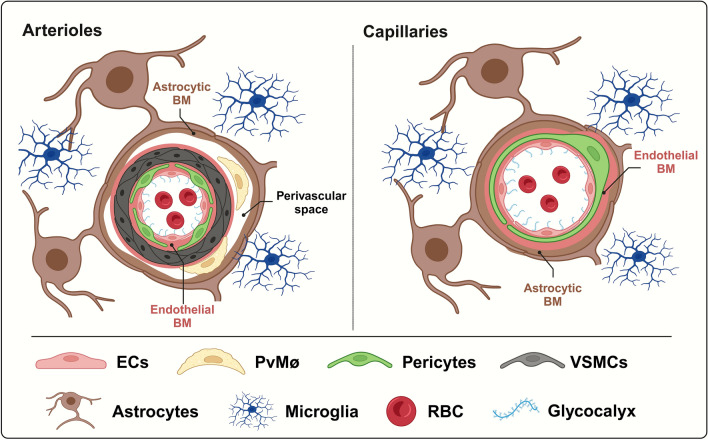

The BBB represents the main interface between the brain and the external environment, as it restricts the transportation of molecules and regulates the trafficking of immune cells between circulation and brain parenchyma. It is a specialized configuration of the cerebral vasculature, comprising ECs enclosed by the endothelial basement membrane, where pericytes, whose extensive cytoplasmic processes wrap around ECs, are embedded (Fig. 1). Astrocyte endfeet, which also secrete their own basement membrane, constitute the most external layer of the BBB [45] (Fig. 1). In arteries and arterioles, the pericytes embedded in the endothelial basement membrane are surrounded by the vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), that are distanced from astrocyte endfeet by the perivascular space, also known as Wirchow-Robin space, where perivascular macrophages (PvMΦ) reside (Fig. 1). A similar BBB organization can be found in veins, where VSMCs are organized in a thinner layer. In capillaries, the pericytes, embedded in the endothelial basement membrane closely interfaced with glia limitans, leave no perivascular space [122] (Fig. 1). PvMΦ, together with meningeal and choroid plexus macrophages, are commonly referred to as CNS (or border)-associated macrophages (CAMs) and can participate in maintaining BBB integrity by scavenging harmful molecules deriving from the bloodstream, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or CNS and promoting efficient immune surveillance [47].

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the different cellular components of the BBB at arterioles and capillaries

Altogether, the above-cited BBB components participate in protecting the CNS and in orchestrating the physiological functions of the BBB, including the regulation of cerebral blood flow (CBF) (Fig. 1).

Cerebrovascular ECs have distinctive characteristics when compared to their counterparts outside the brain as they are strictly joined by tight junctions, express low levels of leukocyte adhesion molecules, exhibit low rates of micropinocytosis and caveolar transcytosis, and possess a plethora of substrate-specific transport systems. These mechanisms regulate the influx of essential nutrients into the brain or the efflux of unwanted substances into the bloodstream [45, 71]. Moreover, these cells secrete a peculiar glycocalyx consisting of a closely knitted network of glycosaminoglycans that coat the luminal surface of blood vessels ensuring elevated luminal surface coverage and low permeability [45].

The endothelial and astrocyte basement membranes, crucial in determining BBB permeability to leukocytes, are composed of an extracellular highly organized amorphous matrix of structural proteins including collagen IV family proteins, nidogens, heparan sulfate proteoglycans and laminins [52]

Pericytes, originating from both the neural crest and mesoderm during development [40, 78], reside in the endothelial basement membrane within microvessel walls, including capillaries, veins, venules and arterioles. Studies indicated that 40–80% of brain ECs are covered by pericytes, varying with brain region, species, and analysis method [51, 107]. Pericytes are believed to play an important role in BBB maintenance, the regulation of capillary diameter, and angiogenesis [19]. VSMCs, situated in large-diameter vessels such as arteries and veins, serve similar functions to pericytes in stabilizing vasculature morphology and functions. Pericytes and ECs co-produce the basement membrane and establish adherens and gap junctions between each other [133]. Adherens junctions connect the cytoskeletons of the two cell types, mediating contact inhibition through contractile forces. Meanwhile, gap junctions interconnect their cytoplasms, facilitating the passage of metabolites and ionic currents.

Astrocyte endfeet interdigitates and overlaps, providing nearly complete coverage of the BBB and forming its outermost layer. Additionally, astrocytes produce substances that affect BBB integrity such as angiotensin II, angiopoietin-1 or sonic hedgehog, that in turn affect ECs homeostasis [140, 142].

Finally, it is worth mentioning that microglial cells, the most widespread brain macrophages derived from haematopoietic precursors that migrate from the yolk sac into the CNS parenchyma [49], serve as the brain’s primary line of defence past the BBB. They play a crucial role in innate immune responses within the CNS. Juxtavascular microglia also interact with vascular areas lacking astrocyte endfeet and can control vascular architecture and BBB permeability in both health and disease [93].

ECs, pericytes and macrophages in the maintenance of BBB integrity and regulation of CBF

Brain ECs are primarily involved in the development and maintenance of the BBB and interact with other cells of the so-called neurovascular unit, a specialized cluster of cellular and extracellular components including neurons, astrocytes, ECs, VSMCs, pericytes and extracellular matrix. The neurovascular unit detects the needs of neuronal supply and triggers necessary responses such as vasodilation or vasoconstriction, to regulate CBF and BBB function [96]. In particular, the interplay between ECs, pericytes, PvMΦ and microglia has a crucial role in regulating the BBB in both healthy and diseased brain [117].

Pericytes are critical for proper vascular development and stabilization by tightly wrapping around brain ECs and engaging in close functional interactions with them [19]. The depletion of pericytes, whether during development or in adulthood, has been observed to increase vascular permeability and disrupt barrier function at least partially by decreasing the expression of tight junction proteins (TJPs) and promoting leukocyte adhesion to ECs, thus highlighting the importance of pericytes in maintaining an intact BBB [4, 26]. Indeed, co-culturing ECs with pericytes in laboratory settings has been shown to enhance the expression of TJPs [26]. Additionally, pericyte contractility influences ECs sprouting and cell cycle progression, indicating their role in controlling endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis [36].

On the other hand, pericytes, like VSMCs, respond to vasoconstrictor and vasodilator signals, enabling them to contract and relax accordingly [51]. This dynamic behavior allows pericytes to control the diameter of capillaries although their role in CBF regulation has not been extensively corroborated. In summary, pericytes play a multifaceted role in vascular development, the maintenance of the BBB and the regulation of vascular functions through their interactions with ECs.

Brain macrophages are essential sentinels in the immune response as they become activated under brain injury or immunological stimuli [47] and the resulting neuroinflammation can contribute to neurodegeneration both directly as well as by impairing the BBB [56, 102, 118, 135]. Discerning the different roles of PvMΦ and vascular-associated microglia in BBB function has been challenging as they share cellular markers, such as Iba1 and CX3CR1, and produce similar inflammatory mediators. However, CAMs can be distinguished from microglia by their location in brain leptomeningeal and perivascular space and expression of the mannose receptor CD206, CD163 and Lyve1 [35]. Though the injection of clodronate liposomes in the ventricles and cisterna magna was reported to selectively deplete PvMΦ and meningeal macrophages, respectively [35, 106], technically it is difficult to achieve without affecting to some extent also parenchymal microglia or the other CAMs. More recently, the combination of single-cell RNA sequencing, time-of-flight mass cytometry and single-cell spatial transcriptomics with fate mapping and advanced immunohistochemistry has opened the possibility to identify distinctive transcriptomic profiles of CAMs [115].

It has long been known that cytokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by macrophages and microglia during inflammatory conditions can induce BBB damage and immune cell infiltration. Vessel-associated microglia, CAMs and ECs act in concert to regulate BBB tightness, angiogenesis and CBF in health and disease [27]. For instance, in the steady-state conditions PvMΦ can promote BBB integrity in vitro and in vivo [57]. Depletion of microglia/macrophages in the striatum decreases the integrity of blood vessels and increases the levels of inflammatory cytokines [53]. Both macrophages and parenchymal microglia have also been shown to promote angiogenesis, especially in tumor conditions [14]. Perivascular microglia play a detrimental role following stroke either indirectly, through the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines which in turn promote ECs activation, or directly by interacting with ECs and engulfing them, thus leading to vessel disintegration [69]. In contrast to macrophages, juxtavascular microglia have been reported to produce Claudin 5, a member of TJPs, to physically interact with ECs and promote vessel injury repair during systemic inflammation [56]. However, during sustained inflammation, activated microglia phagocytose astrocytic endfeet, thus contributing to BBB damage [56].

Much remains unknown regarding signalling pathways involved in the interaction between cerebral ECs and microglia/macrophages in various neurological disorders. Given the anatomical proximity of PvMΦ to ECs of brain vessels and the increasing evidence for the role of these cells in neurodegenerative diseases, it is worth speculating that they play an even superior role in BBB integrity. Therefore, more future studies on the interplay between PvMΦ and ECs in the brain are warranted.

Finally, a reciprocal modulatory interaction between pericytes and microglia has also been highlighted [94]. For instance, microglia can control pericyte maturation, number and apoptosis [48, 141]. On the other hand, pericytes can control microglial function, homeostasis and motility by releasing cytokines, such as interleukin 6, and chemokines including C-X3-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 1, Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, interleukin 8, and C–C Motif Chemokine Ligand 5 [124].

These findings support that the interplay between ECs, pericytes and microglia/macrophages plays a crucial role in maintaining BBB homeostasis and integrity and suggests that insults impacting these different cell populations, including the acute and progressive accumulation of pathological proteins, can perturb their reciprocal inter-regulatory function resulting in brain vascular damage.

The contribution of Aβ, Tau and α-syn to BBB damage in NDDs

Numerous studies have emphasized the effect of Aβ, Tau and α-syn pathology on BBB integrity. In particular, evidence from experimental models has highlighted that these pathological proteins not only cause BBB damage through the activation of brain macrophages that in turn promote neuroinflammation but also affect ECs and pericyte function. Below, we summarize the main findings describing the effect of Aβ, Tau and α-syn on the BBB through the modulation of the interplay between brain macrophages, ECs and pericytes.

Aβ, Tau and α-syn pathology as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) triggering brain macrophage activation

Since in the brain of patients affected by NDDs Aβ, Tau and α-syn are continuously generated, failure to remove them results in chronic neuroinflammation that, in addition to contributing to neuronal damage, further increases BBB permeability and vascular dysfunction [54, 102, 148]. Amyloidogenic proteins can initiate a sterile immune response by acting as DAMPs that activate pattern recognition receptors, such as toll-like receptors (TLRs), on cerebral myeloid cells [54, 148].

Soluble parenchymal Aβ (and other amyloids) can drain into the perivascular space [63], where it encounters PvMΦ. Macrophages, as the resident immune cells within the vasculature, are professional phagocytes and can efficiently engulf amyloid aggregates. High amyloid load and cellular stress can impair phagocytosis function, leading to macrophage cell death and exacerbating CAA pathology [143]. Moreover, a recent study has shown that PvMΦ regulates the flow rate of CSF, which decreases with aging, further reducing the rate of amyloid clearance [35].

The degree of the pro-inflammatory factor release depends on the receptors involved. Receptors like scavenger receptor (SR)-A, SR-BI and triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 promote the uptake of extracellular amyloid deposits without eliciting a significant inflammatory response, whereas TLR2/4 and CD36 stimulation induces the production of neurotoxic cytokines and ROS via nuclear factor κB (NFκB) and NLRP3-ASC-inflammasome pathways, thus promoting neuronal and vascular degeneration [54, 64, 131]. Reduction in SR-A and SR-BI impairs PvMΦ function and enhances CAA [83, 131], while CD36 deficiency in PvMΦ is protective in transgenic mouse models [135].

In addition, post-mortem and experimental studies have shown that neurons with Tau pathology are surrounded by reactive microglia/macrophages [8, 9], suggesting that intraneuronal pathological Tau also activates brain macrophages. Indeed, neurons with Tau filaments expose abnormally high levels of phosphatidylserine triggering opsonin milk-fat-globule EGF-factor-8-mediated phagocytosis by microglia, that in turn become hypofunctional [15, 16]. Phagocytosed Tau has also been reported to trigger inflammatory activation via polyglutamine binding protein 1 cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-Stimulator of interferon genes-NFκB pathway [66].

Other evidence supports that the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway can be induced by fibrillary α-syn or by α-syn-pathology-dependent dopaminergic failure, which results in the reduction of microglia dopamine D1 and D2 receptor stimulation and consequent microglia activation [105, 126].

By compromising BBB permeability and increasing the expression and binding affinity of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 on ECs, pathological protein-related neuroinflammatory cascades also contribute to the recruitment, activation and extravasation into the parenchyma of peripheral immune cells, including neutrophils and T cells, into the brain [104, 144, 145]. In turn, the accumulation of peripheral leukocytes in the blood vessels and perivascular space can decrease blood circulation and increase BBB leakage, thus further contributing to brain damage [10, 24].

In support of the key role of neuroinflammation in T cell recruitment there is evidence indicating that the brain areas exhibiting marked neuroinflammation and microglial activation in post-mortem PD brains frequently show the presence of leukocytes next to MHCII-positive astrocytes in proximity to blood vessels [61, 111]. Another study described that CAMs are localized in close proximity to T cells in post-mortem PD brains and showed that these cells act as the main antigen-presenting cells necessary to initiate a CD4 T cell recruitment and neuroinflammation in response to α-syn accumulation [118]. Similar findings have been described in post-mortem brains of AD and LB dementia patients, where significant T lymphocyte recruitment to both grey and white matter has been reported [3, 134].

Collectively, these observations support that Aβ, Tau and α-syn pathology act as main DAMPs for brain-macrophage activation-related BBB disruption.

Impact of Aβ, Tau and α-syn pathology on ECs

The exact origin of Aβ depositions in the vasculature is not fully understood yet, but evidence suggests that neurons and astrocytes are the main sources, with subsequent spreading or movement towards the vasculature for clearance [39]. However, recent findings also support that ECs may contribute to the production of Aβ and CAA [128].

Aβ exerts both direct or indirect effects on ECs within brain microvasculature by altering the distribution of TJPs, promoting ECs death, elevating oxidative stress and inducing proinflammatory cytokine production in glial cells [130, 145]. Aβ accumulation adversely affects brain vessel walls, leading to BBB damage and potential hemorrhage in CAA mouse models and human patients [42, 55]. In vitro studies have shown that Aβ exposure disrupts actin organization and induces apoptosis in ECs [129]. Furthermore, CAA patients and amyloid precursor protein (APP)-overexpressing mice exhibit decreased TJPs expression and increased levels of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [55]. The presence of Aβ also hampers endothelial nitric oxide synthase/heat shock protein 90 interaction [80] and promotes the formation of von Willebrand factor (VWF) fibers, which contribute to inflammatory and thrombogenic responses in brain vessels [121]. These findings highlight the detrimental effects of Aβ deposition on vessel walls, including ECs impairment, compromised BBB and alterations in inflammatory and thrombogenic responses. All these mechanisms can contribute to the impairment of neurovascular control.

The accumulation of Tau oligomers in cerebral microvessels has been reported in human AD, LB dementia and progressive supranuclear palsy patients [22]. Microbleeds have been detected in the brains of patients affected by frontotemporal dementia [28] and cerebrovascular inflammation has been associated with Tau pathology in Guam parkinsonism dementia and chronic bilirubin encephalopathy. In these cases, areas with significant accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles exhibited upregulation of adhesion molecules, disruption of TJPs, morphological alterations in brain microvessels, including thickening of the vessel wall, vessel lumen reduction as well as increased in collagen-type IV content per vessel [84]. Still, Tau pathology is associated with small vessel disease [70] and immune cells trafficking across the BBB also appears to be modulated by neurofibrillary pathology in Tauopathies [85]. In P301S transgenic mice, brain microvascular ECs uptake soluble pathogenic Tau oligomers from the extracellular space, which over time accumulate within ECs further leading to mitochondrial damage and ECs senescence [60]. Aged Tau-overexpressing mice were found to develop cortical blood vessel changes such as abnormal spiralling morphologies and reduced diameters in parallel to increased vessel density [10]. These changes were accompanied by alteration in cortical CBF and increased expression of angiogenesis-related genes such as Vegfa, Serpine1, and Plau in CD31-positive ECs [10], hinting that Tau pathological changes in neurons can impact brain ECs biology, thus altering the integrity of brain microvasculature. This observation is corroborated by the fact that other lines of Tau transgenic mice exhibit progressive BBB leakage with IgG, T cell, and red blood cell infiltration that is prevented by Tau depletion [11].

Numerous studies support that α-syn can differentially impact on ECs homeostasis as previously reviewed [13]. For instance, transgenic expression of the human A53T mutated form of the protein in mouse brains decreases the expression of TJPs resulting in increased vascular permeability and also leads to the accumulation of oligomeric α-syn in activated astrocytes that release vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A and nitric oxide [81], key regulators of ECs homeostasis. Moreover, toxic forms of α-syn can modulate ECs function by limiting the release of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules from their secretory granules or downregulating the expression of TJPs [72, 79]. This has been recently confirmed in an innovative human brain-on-a-chip model of the substantia nigra and containing dopaminergic neurons, astrocytes, microglia, pericytes, and microvascular brain ECs cultured under fluid flow and exposed to synthetic α-syn preformed fibrils [103]. By using this model, authors found that α-syn synthetic fibrils impair BBB permeability by directly interacting with ECs and altering the expression of vascular channels, TJPs and other key genes involved in BBB homeostasis, including extracellular proteases of the Serpin family and collagens.

Impact of Aβ, Tau and α-syn pathology on pericytes

Pericyte degeneration is associated with Aβ deposition [137], facilitating the progression of neurodegenerative pathology [114]. Consistently, a correlation between Aβ accumulation and pericyte loss in patients with NDDs and transgenic mouse models has been demonstrated [91, 114]. Interestingly, though Aβ42 is commonly considered more cytotoxic than Aβ40 due to its aggregation-prone nature, Aβ40 has been found to exert similar effects on pericytes. In patients with AD, a decreased population of NG2-positive pericytes in the hippocampus was observed, negatively correlating with Aβ40 levels. In vitro experiments revealed that exposure to Aβ40 monomers enhanced pericyte viability and proliferation while reducing caspase 3/7 activity. However, exposure to fibril-enriched Aβ40 resulted in decreased pericyte viability and proliferation, along with increased caspase 3/7 activity [119]. These findings suggest that Aβ40 may serve as a key regulator of the pericyte population in the brain, both in disease and in healthy conditions. The loss of pericytes reduces TJPs expression in ECs, compromising BBB integrity and increasing Aβ load in the brain [107].

Similarly, a study on a human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived BBB model comprising astrocytes, ECs and pericytes suggested that pericytes play a key role in the intravascular accumulation of Aβ [12].

Moreover, Aβ has been discovered to induce pericyte-mediated constriction of brain capillaries through the upregulation of endothelin-1 release, which is mediated by the overproduction of ROS [98]. In vitro studies further support that exposure to Aβ oligomers leads to the development of a hypercontractile phenotype in pericytes [58]. Increased constriction of brain microvessels by hypercontractile pericytes likely contributes to the reduction in CBF observed in NDDs.

Other evidence indicates that following repeated head trauma in mice both types of mural cells, pericytes and VSMCs, uptake recombinant human tau more efficiently as compared to astrocytes and ECs [100]. Interestingly, other studies support that VSMCs undergo significant phenotypic changes and acquire an inflammatory phenotype under AD-like conditions, coinciding with Tau hyperphosphorylation [2]. Although evidence regarding Tau pathology in pericytes is limited, it can be hypothesised that this pathological protein may similarly impact both mural cell types.

Finally, recent studies have shed light on the significant involvement of pericytes in α-syn pathology. In vitro investigations have demonstrated that pericytes can contribute to the clearance of α-syn aggregates by internalizing and degrading them [32, 127]. However, under conditions of additional cellular stress, this process can lead to increased production of ROS in pericytes, ultimately resulting in their apoptosis [127]. Other cell culture studies showed that monomeric α-syn can lead to BBB dysfunction through activated brain pericytes releasing inflammatory mediators such as interleukin 1β, interleukin 6, tumor necrosis factor-α, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and MMP-9 [34]. Additionally, studies utilizing primary brain pericytes obtained from individuals with PD have shown the formation of tunneling nanotubes, which are membranous channels composed of F-actin and facilitate the transfer and spread of α-syn between cells [31]. These findings highlight the complex involvement of pericytes in α-syn pathology, which appears to encompass both beneficial and detrimental effects.

The contribution of Aβ, Tau and α-syn to BBB damage in stroke

Stroke patients have a high risk of developing cognitive decline or parkinsonism, suggesting that pathological protein accumulation induced by brain ischemia can significantly contribute to neurodegeneration. Clinical studies highlighted a significant risk of developing dementia symptoms and progressive cognitive decline after ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes [89]. Post-stroke dementia commonly manifests in patients, particularly as they age, and post-mortem analysis of stroke patients' brain samples has revealed the presence of Aβ deposition [65]. Animal models have also shown increased Aβ deposition and CAA pathology following stroke, suggesting a potential role of Aβ in post-stroke dementia development [46]. One proposed mechanism is the disruption and dysfunction of the BBB after stroke, impairing the clearance of Aβ from the brain to the circulation [46]. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion dysregulates the expression of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 and receptor for advanced glycation endproducts, key mediators of Aβ transport across the BBB and out of the brain, thus leading to Aβ accumulation in the vessel walls and parenchyma [5]. Additionally, the glymphatic system, the brain’s waste disposal system [95] which can also mediate Aβ clearance, may also be affected after stroke, contributing to Aβ buildup [44]. However, a recent review integrating data from clinical and pre-clinical studies has revealed inconsistencies in the relationship between post-stroke Aβ deposition and cognitive impairment, observed in both human patients and rodent models [101].

Conversely, Aβ accumulation itself can increase the risk and severity of stroke [59, 110]. Deposits of Aβ in the vasculature can lead to VSMCs loss and destabilize vessel wall, elevating the risk of hemorrhagic stroke [138]. CAA pathology exacerbated ischemic damage in a mouse model [90]. More evidence is necessary to gain a better understanding of the relationship between Aβ accumulation and stroke, as well as how Aβ may influence the progression of both conditions.

Recent findings support that α-syn and hyperphosphorylated Tau accumulation mediates and promotes stroke-induced brain damage and possibly contributes to post-stroke cognitive impairment [73, 97, 116, 136]. Positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging studies have indeed shown that neurofibrillary tangles can form after ischemic stroke and spread in the peri-ischemic brain parenchyma, while total Tau levels in the CSF positively associate with measures of brain atrophy one-year post-stroke [62]. The levels of oligomeric and Ser129-phosphorylated α-syn, which are considered possible pathological biomarkers for PD, are increased in red blood cells from acute ischemic stroke patients [139]. Furthermore, it has been described that α-syn accumulation promotes glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β-mediated phosphorylation of Tau following transient focal ischemia in mice [87].

Reinforcing the relevance of Tau and α-syn in stroke, it has been observed that Tau and α-syn knockout mice exhibit significantly smaller brain damage after transient focal ischemia when compared to wild-type mice [73, 82, 87]. Moreover, reducing Tau hyperphosphorylation with GSK-3β inhibitors such as nimodipine or by the administration of glucosamine, which by promoting O-GlcNAcylation antagonizes phosphorylation, has shown neuroprotective effects in rodent models of ischemia [20, 87]. Additionally, task-specific training rehabilitation and an enriched environment improved functional deficits and reduced Tau-phosphorylation and neuroinflammation in the phototrombotic ischemia rat model [67], suggesting that brain plasticity mechanisms may modulate Tau pathology following brain ischemia. Finally, it has been described that chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in a rat model of post-stroke dementia aggravated cognitive impairment and Tau hyperphosphorylation by interfering with Tau clearance through the glymphatic system [6]. This aligns with previous findings showing that chronic cerebral hypoperfusion can enhance Tau hyperphosphorylation and impair autophagy in an AD mouse model [108], suggesting that ischemia may perturb the mechanisms of pathological Tau elimination.

Hence, though the exact contribution of Tau and α-syn accumulation to post-ischemic vascular damage remains to be determined, these findings indicate that α-syn accumulation and Tau hyperphosphorylation significantly contribute to post-stroke secondary brain damage and may be possibly considered novel therapeutic targets for stroke therapy. It can be inferred that given the significant role of these proteins in the modulation of microglia/macrophage and BBB cell activation, their accumulation can significantly impact vascular injury thus warranting further studies on this topic.

The contribution of Aβ, Tau and α-syn to BBB damage in TBI

TBI has immediate and devastating effects, often triggering long-term neurodegeneration involving proteins like Aβ, Tau, and α-syn. Studies support that a history of TBI is a risk factor for AD in males [43]. The pathological connection between TBI and AD is supported by the observation of increased Aβ plaques and soluble Aβ species in brain tissue following TBI [29]. Similar acute Aβ accumulations accompanied by neuronal death and memory impairment have been reported in APP-transgenic mice subjected to TBI [123].

Moreover, traumatic axonal injury, a common pathology seen after TBI, provides a potential mechanism for Aβ production. The prevailing hypothesis suggests that the abundant APP, which accumulates in damaged axons, undergoes aberrant cleavage to form Aβ, subsequently aggregating as Aβ plaques [68]. The accumulation of Aβ not only leads to axonal degeneration but also induces neuronal inflammation and neuronal death, thereby contributing to the progression of long-term neurodegenerative diseases.

Several research reports showed the occurrence of pathological hyperphosphorylated Tau accumulation and spreading following TBI, while the ratio between phosphorylated and total Tau in plasma serves as a peripheral biomarker of acute and chronic TBI [112]. In particular, it has been proposed that neuroinflammation and Tau pathology mutually participate in inducing cognitive decline following TBI [23]. Tau/Aβ-induced BBB damage is also believed to initiate a deleterious feed-forward loop contributing to TBI-associated vascular damage [109]. Indeed, markers of vascular injury have been associated with hyperphosphorylated Tau pathology in chronic traumatic encephalopathy [74]. Furthermore, post-mortem studies on the brain of a former professional boxer diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy and comorbid schizophrenia showed that areas with extensive accumulation of hyperphosphorylated Tau protein exhibited BBB damage with a decrease in Claudin 5 and enhanced extravasation of endogenous blood components such as fibrinogen and IgG [41]. This finding aligns with previous studies on patients affected by dementia pugilistica, which showed microvascular damage in association with Tau pathology [86].

It has been reported that α-syn is also increased in the post-mortem brain of subjects with TBI [1, 21] as well as in the CSF of TBI patients [92]. This increase in α-syn following TBI might explain the elevated risk of subsequently developing PD [1, 18] and has been corroborated by animal studies [21]. Evidence showing that lentivirus-mediated downregulation of α-syn reduces neuroinflammation and promotes functional recovery in rats with spinal cord injury [146] also supports that α-syn can contribute to inflammation-associated vascular damage in TBI.

Conclusions and authors’ perspectives

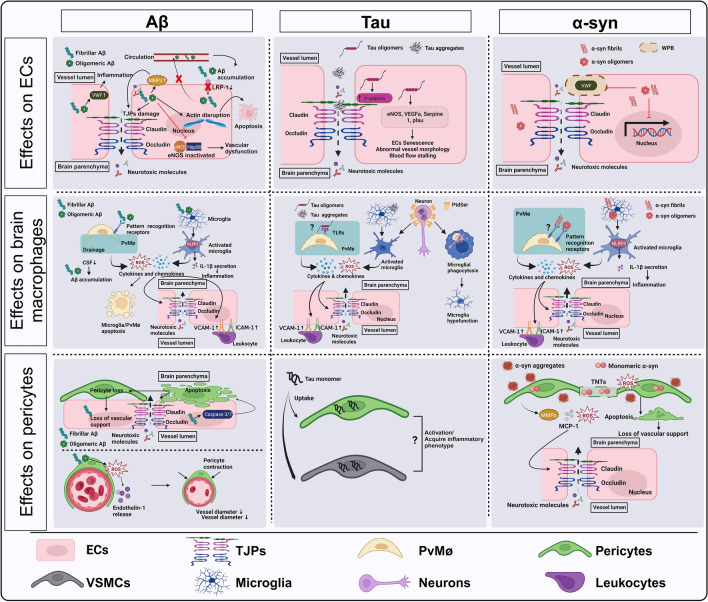

Impairment of the BBB occurs in many neurological disorders, including acquired brain injury conditions such as stroke or TBI, as well as NDDs such as amyloidosis, tauopathies and synucleinopathies. In these conditions, blood vessels are usually damaged secondary to the pathological insult as a result of the activation of the intrinsic cellular mechanisms of neuroinflammation. BBB damage mainly occurs as a result of alterations in TJPs expression, the activation state of ECs, pericytes and astrocytes or impaired angiogenesis [99]. These processes can be triggered by brain inflammation or can be directly initiated by the accumulation of pathological proteins. As highlighted in this review, Aβ, Tau and α-syn can contribute to brain vascular damage mainly by inducing brain macrophage activation or by affecting pericytes and ECs (Fig. 2). This is further supported by findings showing a correlation between vascular risk and Aβ and Tau load in individuals with cognitive decline [76]. Additionally, conditions like CAA can lead to diffuse ischemic brain injury and predisposes individuals to hemorrhagic stroke or intracranial and subarachnoid hemorrhage [59, 110].

Fig. 2.

Overview of the impact of Aβ, Tau and α-syn on ECs, brain macrophages and pericytes. Aβ oligomers and fibrils can enter in ECs producing their activation and damaging TJPs eventually resulting in ECs death. While extracellular Tau fibrillary aggregates can damage TJPs, Tau oligomers can also enter ECs and induce their activation that in turn can produce ECs senescence, thus altering vessel morphology and causing blood flow stalling. ECs can uptake α-syn fibrils and oligomers that can interfere with ECs function, including VWF release. Extracellular Aβ, Tau and α-syn fibrillary aggregates and oligomers have been found to activate brain macrophages mainly by acting as DAMPs. Intracellular Tau aggregates can also produce a peculiar neuronal pro-inflammatory phenotype with Phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) membrane exposure that stimulates their phagocytosis by microglial cells, which consequently become hypofunctional. Brain macrophage activation induced by Aβ, Tau, and α-syn leads to oxidative stress, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and producing pro-inflammatory cytokines. This cascade of events subsequently impacts ECs, contributing to compromised BBB integrity. Additionally, pro-inflammatory cytokines derived from activated brain macrophages and ECs may stimulate ECs expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), thus attracting leukocyte adhesion from circulation. Aβ, Tau and α-syn can also differentially affect pericytes. Aβ can induce pericyte degeneration with subsequent loss of vascular support. Aβ also stimulates pericyte contraction by promoting endothelin release, thus impacting CBF. Tau monomers can enter pericytes stimulating their activation and dysfunction following repeated head trauma. Pericytes can be activated by extracellular α-syn aggregates accumulation and by the uptake of high levels of monomeric α-syn, which can then be transmitted between pericytes through tunnelling nanotubes (TNTs). In turn, pericytes can become hypofunctional and there is a loss of their trophic support on ECs

Given the pivotal role exerted by the BBB in the maintenance of brain homeostasis and in CNS protection, it is predicted that BBB dysfunction can more or less severely contribute to the onset and progression of brain damage in neurological disorders. Consistently, BBB disruption has been associated with severe and detrimental outcomes in the context of many neurological disorders [99].

Since BBB injury is relevant in many CNS disorders, identifying novel therapeutic targets to counteract BBB dysfunction is crucial and compelling. In this framework, we propose that targeting Aβ, Tau and α-syn pathology constitutes an attractive therapeutic avenue to limit BBB damage in NDDs. From the manyfold studies on NDDs we know that using Aβ, Tau and α-syn immunotherapy or gene-silencing therapy raises concerns about potential protein-depleting detrimental effects and the risk of further vascular damage. In general, the re-establishment of the physiological function of these proteins may be more beneficial than clearing them from the brain, as this would also imply a loss of their physiological function. Nevertheless, targeting these proteins in the context of the acute phases of stroke or TBI may be evaluated as a possible option to attenuate vascular injury. For instance, though immunization may be problematic in the context of acute brain injury, gene silencing by antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) administration may be a valuable strategy to reduce the burden of toxic forms of Aβ, Tau and α-syn in stroke or TBI. Since some gene silencing approaches have reached clinical trial [38] and many other are in preclinical development, their repurposing may be easily achievable in the next few years.

Moreover, the levels of pathological proteins in the peripheral fluids of patients following acute brain injury may serve as potential prognostic biomarkers for these disabling conditions. This implies that current diagnostic assays allowing the assessment of Aβ, total and phosphorylated Tau or α-syn in amyloidosis, Tauopathies and synucleinopathies should also be re-evaluated in this context.

On the other hand, it may be feasible that some of the innovative therapeutic approaches proposed for acute brain injury, such as pro-angiogenic therapy, that is under evaluation in the treatment of stroke [113], may be useful to limit BBB damage in the context of neurodegenerative disorders with pathological protein accumulation. On this line, it has been found that VEGF therapy, which ameliorated post-ischemic brain damage following brain ischemia in gerbils [7] can also exert neuroprotective effects in PD models [88].

Though we need to deepen our understanding of the molecular underpinnings linking pathological Aβ, Tau or α-syn burden to BBB dysfunction, exploring their interplay may offer novel insightful perspectives for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic neurological disorders.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Brescia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This project has received funding from the European Union´s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 813294 (ENTRAIN).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ying-Chieh Wu and Tizibt Ashine Bogale have contributed equally.

References

- 1.Acosta SA, Tajiri N, de la Pena I, Bastawrous M, Sanberg PR, Kaneko Y, Borlongan CV. Alpha-synuclein as a pathological link between chronic traumatic brain injury and Parkinson’s disease. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:1024–1032. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilar-Pineda JA, Vera-Lopez KJ, Shrivastava P, Chávez-Fumagalli MA, Nieto-Montesinos R, Alvarez-Fernandez KL, Goyzueta Mamani LD, Davila Del-Carpio G, Gomez-Valdez B, Miller CL, Malhotra R, Lindsay ME, Lino Cardenas CL (2021) Vascular smooth muscle cell dysfunction contribute to neuroinflammation and Tau hyperphosphorylation in Alzheimer disease. iScience 24:102993. 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Amin J, Holmes C, Dorey RB, Tommasino E, Casal YR, Williams DM, Dupuy C, Nicoll JA, Boche D. Neuroinflammation in dementia with Lewy bodies: a human post-mortem study. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:267. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00954-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armulik A, Genové G, Mäe M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, He L, Norlin J, Lindblom P, Strittmatter K, Johansson BR, Betsholtz C. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature. 2010;468:557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature09522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashok A, Rai NK, Raza W, Pandey R, Bandyopadhyay S. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion-induced impairment of Aβ clearance requires HB-EGF-dependent sequential activation of HIF1α and MMP9. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;95:179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Back DB, Choi B-R, Han J-S, Kwon KJ, Choi D-H, Shin CY, Lee J, Kim HY. Characterization of tauopathy in a rat model of post-stroke dementia combining acute infarct and chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijms21186929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellomo M, Adamo EB, Deodato B, Catania MA, Mannucci C, Marini H, Marciano MC, Marini R, Sapienza S, Giacca M, Caputi AP, Squadrito F, Calapai G. Enhancement of expression of vascular endothelial growth factor after adeno-associated virus gene transfer is associated with improvement of brain ischemia injury in the gerbil. Pharmacol Res. 2003;48:309–317. doi: 10.1016/S1043-6618(03)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellucci A, Westwood AJ, Ingram E, Casamenti F, Goedert M, Spillantini MG. Induction of inflammatory mediators and microglial activation in mice transgenic for mutant human P301S tau protein. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1643–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63421-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellucci A, Bugiani O, Ghetti B, Spillantini MG. Presence of reactive microglia and neuroinflammatory mediators in a case of frontotemporal dementia with P301S mutation. Neurodegener Dis. 2011;8:221–229. doi: 10.1159/000322228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett RE, Robbins AB, Hu M, Cao X, Betensky RA, Clark T, Das S, Hyman BT. Tau induces blood vessel abnormalities and angiogenesis-related gene expression in P301L transgenic mice and human Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115:E1289–E1298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710329115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blair LJ, Frauen HD, Zhang B, Nordhues BA, Bijan S, Lin Y-C, Zamudio F, Hernandez LD, Sabbagh JJ, Selenica M-LB, Dickey CA. Tau depletion prevents progressive blood-brain barrier damage in a mouse model of tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:8. doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0186-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanchard JW, Bula M, Davila-Velderrain J, Akay LA, Zhu L, Frank A, Victor MB, Bonner JM, Mathys H, Lin Y-T, Ko T, Bennett DA, Cam HP, Kellis M, Tsai L-H. Reconstruction of the human blood-brain barrier in vitro reveals a pathogenic mechanism of APOE4 in pericytes. Nat Med. 2020;26:952–963. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0886-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogale TA, Faustini G, Longhena F, Mitola S, Pizzi M, Bellucci A. Alpha-synuclein in the regulation of brain endothelial and perivascular cells: gaps and future perspectives. Front Immunol. 2021;12:611761. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.611761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandenburg S, Müller A, Turkowski K, Radev YT, Rot S, Schmidt C, Bungert AD, Acker G, Schorr A, Hippe A. Resident microglia rather than peripheral macrophages promote vascularization in brain tumors and are source of alternative pro-angiogenic factors. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:365–378. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1529-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brelstaff J, Tolkovsky AM, Ghetti B, Goedert M, Spillantini MG. Living neurons with tau filaments aberrantly expose phosphatidylserine and are phagocytosed by microglia. Cell Rep. 2018;24:1939–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brelstaff JH, Mason M, Katsinelos T, McEwan WA, Ghetti B, Tolkovsky AM, Spillantini MG (2021) Microglia become hypofunctional and release metalloproteases and tau seeds when phagocytosing live neurons with P301S tau aggregates. Sci Adv 7:eabg4980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Brett BL, Gardner RC, Godbout J, Dams-O’Connor K, Keene CD. Traumatic brain injury and risk of neurodegenerative disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;91:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown EG, Goldman SM. Traumatic brain injury and α-synuclein. Neurology. 2020;94:335–336. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown LS, Foster CG, Courtney J-M, King NE, Howells DW, Sutherland BA. Pericytes and neurovascular function in the healthy and diseased brain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:282. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cardozo CF, Vera A, Quintana-Peña V, Arango-Davila CA, Rengifo J. Regulation of Tau protein phosphorylation by glucosamine-induced O-GlcNAcylation as a neuroprotective mechanism in a brain ischemia-reperfusion model. Int J Neurosci. 2023;133:194–200. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2021.1901695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson SW, Yan HQ, Li Y, Henchir J, Ma X, Young MS, Ikonomovic MD, Dixon CE. Differential regional responses in soluble monomeric alpha synuclein abundance following traumatic brain injury. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58:362–374. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-02123-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castillo-Carranza DL, Nilson AN, Van Skike CE, Jahrling JB, Patel K, Garach P, Gerson JE, Sengupta U, Abisambra J, Nelson P. Cerebral microvascular accumulation of tau oligomers in Alzheimer’s disease and related tauopathies. Aging Dis. 2017;8:257. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins-Praino LE, Corrigan F. Does neuroinflammation drive the relationship between tau hyperphosphorylation and dementia development following traumatic brain injury? Brain Behav Immun. 2017;60:369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cruz Hernández JC, Bracko O, Kersbergen CJ, Muse V, Haft-Javaherian M, Berg M, Park L, Vinarcsik LK, Ivasyk I, Rivera DA, Kang Y, Cortes-Canteli M, Peyrounette M, Doyeux V, Smith A, Zhou J, Otte G, Beverly JD, Davenport E, Davit Y, Lin CP, Strickland S, Iadecola C, Lorthois S, Nishimura N, Schaffer CB. Neutrophil adhesion in brain capillaries reduces cortical blood flow and impairs memory function in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:413–420. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0329-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cruz-Haces M, Tang J, Acosta G, Fernandez J, Shi R. Pathological correlations between traumatic brain injury and chronic neurodegenerative diseases. Transl Neurodegen. 2017;6:20. doi: 10.1186/s40035-017-0088-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daneman R, Zhou L, Kebede AA, Barres BA. Pericytes are required for blood-brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis. Nature. 2010;468:562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature09513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denes A, Hansen CE, Oezorhan U, Figuerola S, de Vries HE, Sorokin L, Planas AM, Engelhardt B, Schwaninger M (2023) Endothelial cells and macrophages as allies in the brain. Acta Neuropathol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.De Reuck JL, Deramecourt V, Cordonnier C, Leys D, Pasquier F, Maurage CA. Cerebrovascular lesions in patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a neuropathological study. Neurodegener Dis. 2012;9:170–175. doi: 10.1159/000335447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeKosky ST, Abrahamson EE, Ciallella JR, Paljug WR, Wisniewski SR, Clark RSB, Ikonomovic MD. Association of increased cortical soluble Aβ42 levels with diffuse plaques after severe brain injury in humans. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:541. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delic V, Beck KD, Pang KCH, Citron BA. Biological links between traumatic brain injury and Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8:45. doi: 10.1186/s40478-020-00924-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dieriks BV, Park TI-H, Fourie C, Faull RLM, Dragunow M, Curtis MA. α-synuclein transfer through tunneling nanotubes occurs in SH-SY5Y cells and primary brain pericytes from Parkinson’s disease patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42984. doi: 10.1038/srep42984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dieriks BV, Highet B, Alik A, Bellande T, Stevenson TJ, Low V, Park TI-H, Correia J, Schweder P, Faull RLM, Melki R, Curtis MA, Dragunow M. Human pericytes degrade diverse α-synuclein aggregates. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0277658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dietrich HH, Xiang C, Han BH, Zipfel GJ, Holtzman DM. Soluble amyloid-beta, effect on cerebral arteriolar regulation and vascular cells. Mol Neurodegener. 2010;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dohgu S, Takata F, Matsumoto J, Kimura I, Yamauchi A, Kataoka Y. Monomeric α-synuclein induces blood–brain barrier dysfunction through activated brain pericytes releasing inflammatory mediators in vitro. Microvasc Res. 2019;124:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drieu A, Du S, Storck SE, Rustenhoven J, Papadopoulos Z, Dykstra T, Zhong F, Kim K, Blackburn S, Mamuladze T. Parenchymal border macrophages regulate the flow dynamics of the cerebrospinal fluid. Nature. 2022;611:585–593. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05397-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durham JT, Surks HK, Dulmovits BM, Herman IM. Pericyte contractility controls endothelial cell cycle progression and sprouting: insights into angiogenic switch mechanics. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;307:C878–892. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00185.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elabi O, Gaceb A, Carlsson R, Padel T, Soylu-Kucharz R, Cortijo I, Li W, Li J-Y, Paul G. Human α-synuclein overexpression in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease leads to vascular pathology, blood brain barrier leakage and pericyte activation. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1120. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80889-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engelender S, Stefanis L, Oddo S, Bellucci A. Can we treat neurodegenerative proteinopathies by enhancing protein degradation? Mov Disord. 2022;37:1346–1359. doi: 10.1002/mds.29058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ernesto SJ, Hascup KN, Hascup ER. Alzheimer’s disease: the link between amyloid-β and neurovascular dysfunction. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020;76:1179–1198. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Etchevers HC, Vincent C, Le Douarin NM, Couly GF. The cephalic neural crest provides pericytes and smooth muscle cells to all blood vessels of the face and forebrain. Development. 2001;128:1059–1068. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farrell M, Aherne S, O’Riordan S, O’Keeffe E, Greene C, Campbell M. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction in a boxer with chronic traumatic encephalopathy and schizophrenia. Clin Neuropathol. 2019;38:51–58. doi: 10.5414/NP301130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher M, Vasilevko V, Passos GF, Ventura C, Quiring D, Cribbs DH. Therapeutic modulation of cerebral microhemorrhage in a mouse model of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke. 2011;42:3300–3303. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fleminger S. Head injury as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease: the evidence 10 years on; a partial replication. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:857–862. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.7.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaberel T, Gakuba C, Goulay R, De Lizarrondo SM, Hanouz J-L, Emery E, Touze E, Vivien D, Gauberti M. Impaired glymphatic perfusion after strokes revealed by contrast-enhanced MRI: a new target for fibrinolysis? Stroke. 2014;45:3092–3096. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galea I. The blood–brain barrier in systemic infection and inflammation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:2489–2501. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00757-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcia-Alloza M, Gregory J, Kuchibhotla KV, Fine S, Wei Y, Ayata C, Frosch MP, Greenberg SM, Bacskai BJ. Cerebrovascular lesions induce transient amyloid deposition. Brain. 2011;134:3697–3707. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gasull AD, Glavan M, Samawar SKR, Kapupara K, Kelk J, Rubio M, Fumagalli S, Sorokin L, Vivien D (2023) The niche matters: origin, function and fate of cns-associated macrophages during health and disease. Acta Neuropathol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Geranmayeh MH, Rahbarghazi R, Saeedi N, Farhoudi M. Metformin-dependent variation of microglia phenotype dictates pericytes maturation under oxygen-glucose deprivation. Tissue Barriers. 2022;10:2018928. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2021.2018928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S, Mehler MF, Conway SJ, Ng LG, Stanley ER, Samokhvalov IM, Merad M. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goedert M, Jakes R, Spillantini MG. The synucleinopathies: twenty years on. JPD. 2017;7:S51–S69. doi: 10.3233/JPD-179005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hall CN, Reynell C, Gesslein B, Hamilton NB, Mishra A, Sutherland BA, O’Farrell FM, Buchan AM, Lauritzen M, Attwell D. Capillary pericytes regulate cerebral blood flow in health and disease. Nature. 2014;508:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature13165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hallmann R, Horn N, Selg M, Wendler O, Pausch F, Sorokin LM. Expression and function of laminins in the embryonic and mature vasculature. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:979–1000. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Han X, Li Q, Lan X, El-Mufti L, Ren H, Wang J. Microglial depletion with clodronate liposomes increases proinflammatory cytokine levels, induces astrocyte activation, and damages blood vessel integrity. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56:6184–6196. doi: 10.1007/s12035-019-1502-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harms AS, Ferreira SA, Romero-Ramos M. Periphery and brain, innate and adaptive immunity in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2021;141:527–545. doi: 10.1007/s00401-021-02268-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartz AMS, Bauer B, Soldner ELB, Wolf A, Boy S, Backhaus R, Mihaljevic I, Bogdahn U, Klünemann HH, Schuierer G, Schlachetzki F. Amyloid-β contributes to blood-brain barrier leakage in transgenic human amyloid precursor protein mice and in humans with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke. 2012;43:514–523. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.627562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haruwaka K, Ikegami A, Tachibana Y, Ohno N, Konishi H, Hashimoto A, Matsumoto M, Kato D, Ono R, Kiyama H, Moorhouse AJ, Nabekura J, Wake H. Dual microglia effects on blood brain barrier permeability induced by systemic inflammation. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5816. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13812-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He H, Mack JJ, Güç E, Warren CM, Squadrito ML, Kilarski WW, Baer C, Freshman RD, McDonald AI, Ziyad S, Swartz MA, De Palma M, Iruela-Arispe ML. Perivascular macrophages limit permeability. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:2203–2212. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hibbs E, Love S, Miners JS. Pericyte contractile responses to endothelin-1 and Aβ peptides: assessment by electrical impedance assay. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:723953. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.723953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hostettler IC, Wilson D, Fiebelkorn CA, Aum D, Ameriso SF, Eberbach F, Beitzke M, Kleinig T, Phan T, Marchina S, Schneckenburger R, Carmona-Iragui M, Charidimou A, Mourand I, Parreira S, Ambler G, Jäger HR, Singhal S, Ly J, Ma H, Touzé E, Geraldes R, Fonseca AC, Melo T, Labauge P, Lefèvre P-H, Viswanathan A, Greenberg SM, Fortea J, Apoil M, Boulanger M, Viader F, Kumar S, Srikanth V, Khurram A, Fazekas F, Bruno V, Zipfel GJ, Refai D, Rabinstein A, Graff-Radford J, Werring DJ. Risk of intracranial haemorrhage and ischaemic stroke after convexity subarachnoid haemorrhage in cerebral amyloid angiopathy: international individual patient data pooled analysis. J Neurol. 2022;269:1427–1438. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10706-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hussong SA, Banh AQ, Van Skike CE, Dorigatti AO, Hernandez SF, Hart MJ, Ferran B, Makhlouf H, Gaczynska M, Osmulski PA. Soluble pathogenic tau enters brain vascular endothelial cells and drives cellular senescence and brain microvascular dysfunction in a mouse model of tauopathy. Nat Commun. 2023;14:2367. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37840-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iba M, Kim C, Sallin M, Kwon S, Verma A, Overk C, Rissman RA, Sen R, Sen JM, Masliah E. Neuroinflammation is associated with infiltration of T cells in Lewy body disease and α-synuclein transgenic models. J Neuroinflamm. 2020;17:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01888-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ihle-Hansen H, Hagberg G, Fure B, Thommessen B, Fagerland MW, Øksengård AR, Engedal K, Selnes P. Association between total-Tau and brain atrophy one year after first-ever stroke. BMC Neurol. 2017;17:107. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0890-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, Benveniste H, Vates GE, Deane R, Goldman SA, Nagelhus EA, Nedergaard M (2012) A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci Transl Med 4:147ra111. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Jaworski T, Lechat B, Demedts D, Gielis L, Devijver H, Borghgraef P, Duimel H, Verheyen F, Kügler S, Van Leuven F. Dendritic degeneration, neurovascular defects, and inflammation precede neuronal loss in a mouse model for tau-mediated neurodegeneration. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2001–2015. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jendroska K, Poewe W, Pluess J, Iwerssen-Schmidt H, Paulsen J, Barthel S, Schelosky L, Cervos-Navarro J, Daniel SE, DeArmond SJ (1995) Ischemic stress induces deposition of amyloid ? Immunoreactivity in human brain. Acta Neuropathol 90:461–466.10.1007/BF00294806 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Jin M, Shiwaku H, Tanaka H, Obita T, Ohuchi S, Yoshioka Y, Jin X, Kondo K, Fujita K, Homma H. Tau activates microglia via the PQBP1-cGAS-STING pathway to promote brain inflammation. Nat Commun. 2021;12:6565. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26851-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Joa K-L, Moon S, Kim J-H, Shin DW, Lee K-H, Jung S, Kim M-O, Kim C-H, Jung H-Y, Kang J-H. Effects of task-specific rehabilitation training on tau modification in rat with photothrombotic cortical ischemic damage. Neurochem Int. 2017;108:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Traumatic brain injury and amyloid-β pathology: a link to Alzheimer’s disease? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:361–370. doi: 10.1038/nrn2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jolivel V, Bicker F, Binamé F, Ploen R, Keller S, Gollan R, Jurek B, Birkenstock J, Poisa-Beiro L, Bruttger J, Opitz V, Thal SC, Waisman A, Bäuerle T, Schäfer MK, Zipp F, Schmidt MHH. Perivascular microglia promote blood vessel disintegration in the ischemic penumbra. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:279–295. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1372-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kapasi A, Yu L, Petyuk V, Arfanakis K, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Association of small vessel disease with tau pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2022;143:349–362. doi: 10.1007/s00401-021-02397-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Keaney J, Campbell M. The dynamic blood–brain barrier. FEBS J. 2015;282:4067–4079. doi: 10.1111/febs.13412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim KS, Park J-Y, Jou I, Park SM. Regulation of weibel-palade body exocytosis by α-synuclein in endothelial cells*. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21416–21425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.103499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim T, Mehta SL, Kaimal B, Lyons K, Dempsey RJ, Vemuganti R. Poststroke induction of synuclein mediates ischemic brain damage. J Neurosci. 2016;36:7055–7065. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1241-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kirsch D, Shah A, Dixon E, Kelley H, Cherry JD, Xia W, Daley S, Aytan N, Cormier K, Kubilus C, Mathias R, Alvarez VE, Huber BR, McKee AC, Stein TD. Vascular injury is associated with repetitive head impacts and tau pathology in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2023;82:127–139. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlac122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Knox EG, Aburto MR, Clarke G, Cryan JF, O’Driscoll CM. The blood-brain barrier in aging and neurodegeneration. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:2659–2673. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01511-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Köbe T, Gonneaud J, Pichet Binette A, Meyer P-F, McSweeney M, Rosa-Neto P, Breitner JCS, Poirier J, Villeneuve S, for the Presymptomatic Evaluation of Experimental or Novel Treatments for Alzheimer Disease (PREVENT-AD) Research Group (2020) Association of Vascular Risk Factors With β-Amyloid Peptide and Tau Burdens in Cognitively Unimpaired Individuals and Its Interaction With Vascular Medication Use. JAMA Network Open 3:e1920780–e1920780.10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Koizumi K, Wang G, Park L. Endothelial dysfunction and amyloid-β-induced neurovascular alterations. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016;36:155–165. doi: 10.1007/s10571-015-0256-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Korn J, Christ B, Kurz H. Neuroectodermal origin of brain pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells. J Comp Neurol. 2002;442:78–88. doi: 10.1002/cne.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kuan W-L, Bennett N, He X, Skepper JN, Martynyuk N, Wijeyekoon R, Moghe PV, Williams-Gray CH, Barker RA. α-Synuclein pre-formed fibrils impair tight junction protein expression without affecting cerebral endothelial cell function. Exp Neurol. 2016;285:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lamoke F, Mazzone V, Persichini T, Maraschi A, Harris MB, Venema RC, Colasanti M, Gliozzi M, Muscoli C, Bartoli M, Mollace V. Amyloid β peptide-induced inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide production involves oxidative stress-mediated constitutive eNOS/HSP90 interaction and disruption of agonist-mediated Akt activation. J Neuroinflamm. 2015;12:84. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0304-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lan G, Wang P, Chan RB, Liu Z, Yu Z, Liu X, Yang Y, Zhang J. Astrocytic VEGFA: an essential mediator in blood-brain-barrier disruption in Parkinson’s disease. Glia. 2022;70:337–353. doi: 10.1002/glia.24109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lohmann S, Grigoletto J, Bernis ME, Pesch V, Ma L, Reithofer S, Tamgüney G (2022) Ischemic stroke causes Parkinson’s disease-like pathology and symptoms in transgenic mice overexpressing alpha-synuclein. acta neuropathol commun 10:26. 10.1186/s40478-022-01327-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Lifshitz V, Weiss R, Levy H, Frenkel D. Scavenger receptor A deficiency accelerates cerebrovascular amyloidosis in an animal model. J Mol Neurosci. 2013;50:198–203. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9909-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Majerova P, Garruto RM, Kovac A. Cerebrovascular inflammation is associated with tau pathology in Guam parkinsonism dementia. J Neural Transm. 2018;125:1013–1025. doi: 10.1007/s00702-018-1883-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Majerova P, Michalicova A, Cente M, Hanes J, Vegh J, Kittel A, Kosikova N, Cigankova V, Mihaljevic S, Jadhav S. Trafficking of immune cells across the blood-brain barrier is modulated by neurofibrillary pathology in tauopathies. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0217216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, Hedley-Whyte ET, Gavett BE, Budson AE, Santini VE, Lee H-S, Kubilus CA, Stern RA. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:709–735. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mehta SL, Kim T, Chelluboina B, Vemuganti R. Tau and GSK-3β are critical contributors to α-synuclein-mediated post-stroke brain damage. NeuroMol Med. 2023;25:94–101. doi: 10.1007/s12017-022-08731-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Meng X-Y, Huang A-Q, Khan A, Zhang L, Sun X-Q, Song H, Han J, Sun Q-R, Wang Y-D, Li X-L. Vascular endothelial growth factor-loaded poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid nanoparticles with controlled release protect the dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s rats. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2020;95:631–639. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mijajlović MD, Pavlović A, Brainin M, Heiss W-D, Quinn TJ, Ihle-Hansen HB, Hermann DM, Assayag EB, Richard E, Thiel A, Kliper E, Shin Y-I, Kim Y-H, Choi S, Jung S, Lee Y-B, Sinanović O, Levine DA, Schlesinger I, Mead G, Milošević V, Leys D, Hagberg G, Ursin MH, Teuschl Y, Prokopenko S, Mozheyko E, Bezdenezhnykh A, Matz K, Aleksić V, Muresanu D, Korczyn AD, Bornstein NM. Post-stroke dementia—a comprehensive review. BMC Med. 2017;15:11. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0779-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Milner E, Zhou M-L, Johnson AW, Vellimana AK, Greenberg JK, Holtzman DM, Han BH, Zipfel GJ. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy increases susceptibility to infarction after focal cerebral ischemia in Tg2576 mice. Stroke. 2014;45:3064–3069. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Miners JS, Schulz I, Love S. Differing associations between Aβ accumulation, hypoperfusion, blood–brain barrier dysfunction and loss of PDGFRB pericyte marker in the precuneus and parietal white matter in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38:103–115. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17690761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mondello S, Buki A, Italiano D, Jeromin A. Synuclein in CSF of patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Neurology. 2013;80:1662–1668. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182904d43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mondo E, Becker SC, Kautzman AG, Schifferer M, Baer CE, Chen J, Huang EJ, Simons M, Schafer DP. A developmental analysis of juxtavascular microglia dynamics and interactions with the vasculature. J Neurosci. 2020;40:6503–6521. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3006-19.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morris GP, Foster CG, Courtney J, Collins JM, Cashion JM, Brown LS, Howells DW, DeLuca GC, Canty AJ, King AE. Microglia directly associate with pericytes in the central nervous system. Glia. 2023;71:1847–1869. doi: 10.1002/glia.24371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Munk AS, Wang W, Bèchet NB, Eltanahy AM, Cheng AX, Sigurdsson B, Benraiss A, Mäe MA, Kress BT, Kelley DH, Betsholtz C, Møllgård K, Meissner A, Nedergaard M, Lundgaard I. PDGF-B is required for development of the glymphatic system. Cell Rep. 2019;26:2955–2969.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Muoio V, Persson PB, Sendeski MM. The neurovascular unit—concept review. Acta Physiol. 2014;210:790–798. doi: 10.1111/apha.12250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Noll JM, Augello CJ, Kürüm E, Pan L, Pavenko A, Nam A, Ford BD. Spatial analysis of neural cell proteomic profiles following ischemic stroke in mice using high-plex digital spatial profiling. Mol Neurobiol. 2022;59:7236–7252. doi: 10.1007/s12035-022-03031-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nortley R, Korte N, Izquierdo P, Hirunpattarasilp C, Mishra A, Jaunmuktane Z, Kyrargyri V, Pfeiffer T, Khennouf L, Madry C, Gong H, Richard-Loendt A, Huang W, Saito T, Saido TC, Brandner S, Sethi H, Attwell D (2019) Amyloid β oligomers constrict human capillaries in Alzheimer’s disease via signaling to pericytes. Science 365:eaav9518. 10.1126/science.aav9518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.Obermeier B, Daneman R, Ransohoff RM. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Med. 2013;19:1584–1596. doi: 10.1038/nm.3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ojo J, Eisenbaum M, Shackleton B, Lynch C, Joshi U, Saltiel N, Pearson A, Ringland C, Paris D, Mouzon B, Mullan M, Crawford F, Bachmeier C. Mural cell dysfunction leads to altered cerebrovascular tau uptake following repetitive head trauma. Neurobiol Dis. 2021;150:105237. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ouyang F, Jiang Z, Chen X, Chen Y, Wei J, Xing S, Zhang J, Fan Y, Zeng J. Is cerebral amyloid-β deposition related to post-stroke cognitive impairment? Transl Stroke Res. 2021;12:946–957. doi: 10.1007/s12975-021-00921-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Park L, Uekawa K, Garcia-Bonilla L, Koizumi K, Murphy M, Pistik R, Younkin L, Younkin S, Zhou P, Carlson G. Brain perivascular macrophages initiate the neurovascular dysfunction of Alzheimer Aβ peptides. Circ Res. 2017;121:258–269. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pediaditakis I, Kodella KR, Manatakis DV, Le CY, Hinojosa CD, Tien-Street W, Manolakos ES, Vekrellis K, Hamilton GA, Ewart L, Rubin LL, Karalis K. Modeling alpha-synuclein pathology in a human brain-chip to assess blood-brain barrier disruption. Nat Commun. 2021;12:5907. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pietronigro E, Zenaro E, Bianca VD, Dusi S, Terrabuio E, Iannoto G, Slanzi A, Ghasemi S, Nagarajan R, Piacentino G, Tosadori G, Rossi B, Constantin G. Blockade of α4 integrins reduces leukocyte–endothelial interactions in cerebral vessels and improves memory in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12055. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48538-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pike AF, Longhena F, Faustini G, Van Eik J-M, Gombert I, Herrebout MAC, Fayed MMHE, Sandre M, Varanita T, Teunissen CE, Hoozemans JJM, Bellucci A, Veerhuis R, Bubacco L. Dopamine signaling modulates microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation: implications for Parkinson’s disease. J Neuroinflamm. 2022;19:50. doi: 10.1186/s12974-022-02410-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Polfliet MMJ, Goede PH, Van Kesteren-Hendrikx EML, Van Rooijen N, Dijkstra CD, Van Den Berg TK. A method for the selective depletion of perivascular and meningeal macrophages in the central nervous system. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;116:188–195. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(01)00282-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Procter TV, Williams A, Montagne A. Interplay between brain pericytes and endothelial cells in dementia. Am J Pathol. 2021;191:1917–1931. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2021.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Qiu L, Ng G, Tan EK, Liao P, Kandiah N, Zeng L. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion enhances Tau hyperphosphorylation and reduces autophagy in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23964. doi: 10.1038/srep23964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ramos-Cejudo J, Wisniewski T, Marmar C, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Fossati S. Traumatic brain injury and Alzheimer’s disease: the cerebrovascular link. EBioMedicine. 2018;28:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Reijmer YD, van Veluw SJ, Greenberg SM. Ischemic brain injury in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:40–54. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rostami J, Fotaki G, Sirois J, Mzezewa R, Bergström J, Essand M, Healy L, Erlandsson A. Astrocytes have the capacity to act as antigen-presenting cells in the Parkinson’s disease brain. J Neuroinflamm. 2020;17:119. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-01776-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rubenstein R, Chang B, Yue JK, Chiu A, Winkler EA, Puccio AM, Diaz-Arrastia R, Yuh EL, Mukherjee P, Valadka AB, Gordon WA, Okonkwo DO, Davies P, Agarwal S, Lin F, Sarkis G, Yadikar H, Yang Z, Manley GT, Wang KKW, the TRACK-TBI Investigators Comparing plasma phospho tau, total tau, and phospho tau-total tau ratio as acute and chronic traumatic brain injury biomarkers. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:1063–1072. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rust R, Gantner C, Schwab ME. Pro- and antiangiogenic therapies: current status and clinical implications. FASEB J. 2019;33:34–48. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800640RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sagare AP, Bell RD, Zhao Z, Ma Q, Winkler EA, Ramanathan A, Zlokovic BV. Pericyte loss influences Alzheimer-like neurodegeneration in mice. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2932. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]