Abstract

Background

The ability of digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) to reduce mental health disparities relies on the recruitment of research participants with diverse sociodemographic and self-identity characteristics. Despite its importance, sociodemographic reporting in research is often limited, and the state of reporting practices in DMHI research in particular has not been comprehensively reviewed.

Objectives

To characterise the state of sociodemographic data reported in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of app-based DMHIs published globally from 2007 to 2022.

Methods

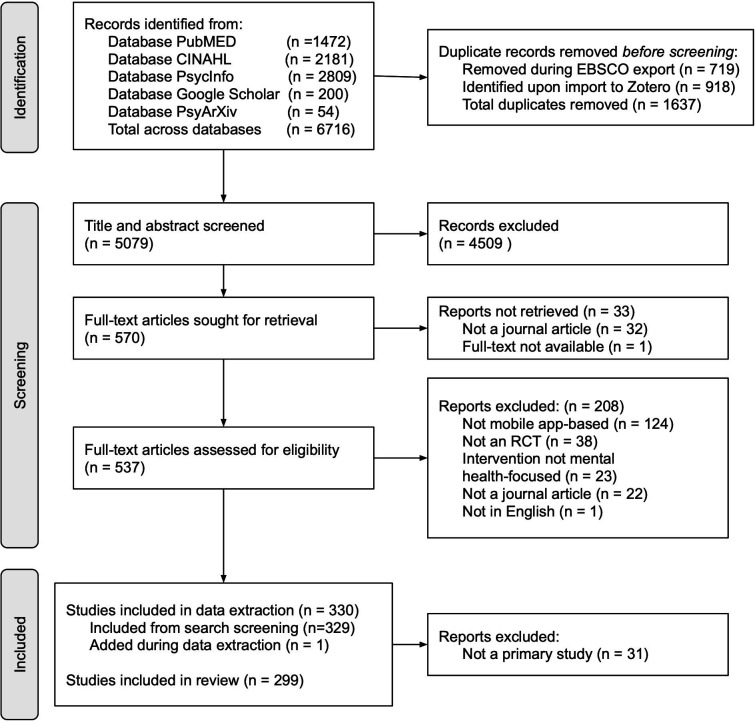

A scoping review of RCTs of app-based DMHIs examined reporting frequency for 16 sociodemographic domains (eg, gender) and common category options within each domain (eg, woman). The search queried five electronic databases. 5079 records were screened and 299 articles were included.

Results

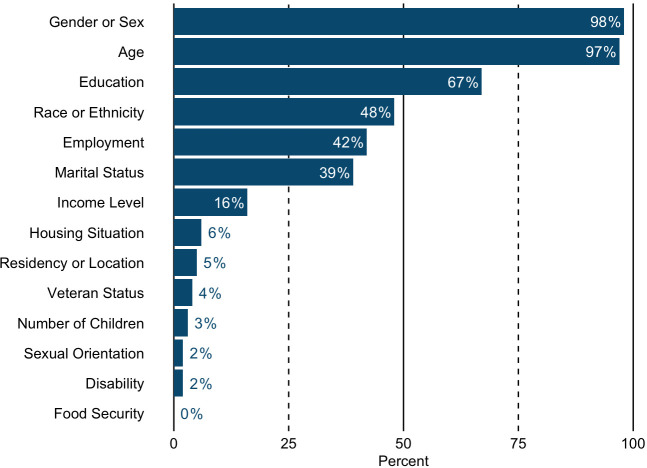

On average, studies reported 4.64 (SD=1.79; range 0–9) of 16 sociodemographic domains. The most common were age (97%) and education (67%). The least common were housing situation (6%), residency/location (5%), veteran status (4%), number of children (3%), sexual orientation (2%), disability status (2%) and food security (<1%). Gender or sex was reported in 98% of studies: gender only (51%), sex only (28%), both (<1%) and gender/sex reported but unspecified (18%). Race or ethnicity was reported in 48% of studies: race only (14%), ethnicity only (14%), both (10%) and race/ethnicity reported but unspecified (10%).

Conclusions

This review describes the widespread underreporting of sociodemographic information in RCTs of app-based DMHIs published from 2007 to 2022. Reporting was often incomplete (eg, % female only), unclear (eg, the conflation of gender/sex) and limited (eg, only options representing majority groups were reported). Trends suggest reporting has somewhat improved in recent years. Diverse participant populations must be welcomed and described in DMHI research to broaden learning and the generalisability of results, a prerequisite of DMHI’s potential to reduce disparities in mental healthcare.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, Health Equity, Systematic Review, Randomized Controlled Trial

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study assessed global sociodemographic reporting practices in randomised controlled trials of treatment outcomes research for app-based digital mental health interventions (DMHIs).

This review systematically screened over 5000 records, included nearly 300 articles spanning the entire lifespan of app-based DMHIs and extracted data for 16 sociodemographic domains.

Article inclusion criteria allowed for a broad range of DMHI studies, including populations with both clinical and subclinical conditions.

It was not feasible to report on the sociodemographic composition of each study sample due to the large number of studies included in the review and the breadth of domains evaluated.

This review is descriptive and did not formally assess statistical differences in reporting practices between different subgroups or time periods or provide any assessment of barriers, facilitators or solutions to the issues identified.

Background

Mental health problems, like physical health problems, can affect anyone, regardless of identity. However, marginalised individuals, including those who have been and/or are actively discriminated against and experience social, political and economic exclusion due to factors such as age, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, disability and socioeconomic status, are frequently impacted by mental health inequities.1–3 Such inequities may include experiencing higher acute and/or lifetime prevalence rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance use and suicide,4–14 as well as being more likely to be undiagnosed or underdiagnosed and less likely to receive treatment for their presenting mental health concern.9 15 16 It is widely acknowledged that clinical psychology research has played a vital role in not only facilitating our current understanding of mental health conditions, including their prevalence and course, but also in identifying and refining evidence-based mental health treatment protocols that can meaningfully improve patient symptoms and quality of life.17 Unfortunately, such research has a longstanding history of limited sociodemographic diversity among its samples.18–20

The impact of limited diversity in sample composition has substantial downstream effects. Homogenous research samples—those lacking in diverse ethnicities, races, ages, genders, sexual orientations, socioeconomic backgrounds, or data regarding these characteristics—limit opportunities to develop and test interventions of interest among such populations, thereby reducing both clinical research learning and the generalisability of findings. Over time, the chronic lack of diversity and inclusion in such research may further alienate underrepresented groups and inhibit them from participating in such studies, increase their wariness of the medical research system and diminish their opportunity to receive care via clinical research or healthcare ecosystems.21 22 Conversely, the purposeful and directed inclusion of participants from various backgrounds provides opportunities to identify similarities or differences in treatment response, utilisation, satisfaction, side effects and more. This, in turn, illuminates treatment adaptation opportunities when indicated23 and ultimately encourages the generation of scientific literature that is fundamentally more representative of all peoples. Growing knowledge of these issues has led to numerous calls to action, beginning in the early 1990s, to improve the representation of marginalised groups in clinical research from agencies around the globe such as the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the European Union’s International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH).24–28 Despite these efforts, one persistent barrier to a greater understanding of sample diversity is the limited reporting of sociodemographic information in clinical research.29–32 For example, in a cross-sectional study of sociodemographic reporting in a subselection of clinical randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published from 2014 to 2020 in five top medical journals, Orkin et al found that while age and descriptors of sex or gender were reported by nearly 99% of the 237 included studies, only 48.5% provided a descriptor of race or ethnicity, and all other sociodemographic domains assessed were reported in fewer than 15% of studies.33 Inconsistent reporting of sociodemographic characteristics of clinical research samples hampers efforts to improve the inclusivity and diversity of clinical research and risks harm to members of marginalised communities (eg, from misinterpretation of results).34

What might be driving these limitations in reporting? One possible reason for limited sociodemographic reporting may be researchers’ efforts to reduce participant’s assessment burden by limiting the number of questionnaire items pertaining to sociodemographic information.35 Another possible reason is a lack of standardised approaches to collecting sociodemographic information in mental health research. While several guidelines have been published, some are outdated and discordant with current cultural norms, few offer best practices for how to collect this information, and none are comprehensive enough to include all relevant sociodemographic factors.36–41 A third may be related to restrictions imposed by scientific journals on word count, table size or other formatting requirements, which may cause researchers to reduce or selectively report sociodemographic information that was actually collected. Finally, a fourth possible reason is researcher bias regarding how and what types of information to collect, such as offering a limited number of choices or requiring single-answer responses to self-identity questions.34 Such practices can inadvertently force participants to select categories that are not fully representative of their identity.34

Digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) present an opportunity to improve both structural (eg, cost, provider shortages, service inaccessibility, etc) and attitudinal (eg, perceived stigma) barriers to care.2 42–44 Indeed, DMHIs have enormous potential to improve service accessibility in marginalised communities; however, individuals from these populations may be consistently underrepresented in DMHI research,45–47 unfortunately, emulating the larger clinical research field. The ability for DMHIs to be optimally poised to minimise barriers contributing to mental health disparities is attenuated if DMHI research continues to analyse homogenous sociodemographic and self-identity samples. However, efforts to diversify samples rely on the comprehensive collection and reporting of sociodemographic information. To date, the state of sociodemographic reporting practices in DMHI research has not been comprehensively reviewed. Therefore, the present study aims to characterise sociodemographic and self-identity data reporting practices in DMHI outcome research. This review may provide a foundational component for the development of comprehensive sociodemographic and self-identity data reporting guidelines for future research.

Primary objectives

To investigate the common practices for reporting sociodemographic information in RCTs of app-based DMHIs published globally from 2007 to 2022. The authors sought to address this overarching aim via two research questions:

What are the common sociodemographic domains reported in RCTs of DMHIs and how frequently is each sociodemographic domain reported?

What are the commonly reported category options within each sociodemographic domain?

Exploratory objectives

Sociodemographic reporting practices are not internationally standardised, and different countries may develop unique practices suited to their context. As such, one of our exploratory objectives was to separate US and non-US studies in order to isolate reporting practices in the USA specifically. Additionally, previous research found a general increase in reporting of sociodemographic variables over the past four decades.29 Therefore, a second exploratory objective was to describe reporting practices over time. These exploratory objectives resulted in two additional research questions:

Does the reporting of sociodemographic domains appear to differ between US and non-US countries?

Does the reporting frequency of sociodemographic domains appear to change over time (ie, from 2007 to 2022)?

Methods

Protocol

The study protocol was developed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews48 and was preregistered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/rs3c4; see online supplemental file 1 for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) checklist). There were several deviations from the protocol. First, we did not conduct a search of all references within each included source of evidence as originally planned, as the original search returned more included studies than anticipated. Additional screening would have exceeded the research team’s bandwidth. Second, the protocol originally planned to assess the extent to which studies in the review allowed for self-expression; for example, by providing the ability to select multiple options for one sociodemographic domain, the ability to write in a response, as well as the phrasing of write-in options (eg, ‘other’). Unfortunately, studies did not provide consistent or clear information on these questions, and therefore, we were unable to code for their presence. Third, Google Sheets, rather than JBI SUMARI, was used to manage coding due to technical difficulties with JBI SUMARI. Fourth, exclusion reasons were not coded at the title and abstract review stages because this is not a PRISMA requirement. Fifth, after the publication of the protocol, the domain ‘residency/location’ was added in order to capture whether a sample was described as rural, urban, etc.

bmjopen-2023-078029supp001.pdf (67.9KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

None.

Eligibility criteria

Manuscripts that reported on RCTs of app-based DMHIs were included. As RCTs are considered the ‘gold standard’ of clinical research,49 data collection and reporting practices in RCTs are expected to be the most rigorous of any clinical research design. Therefore, all other study designs were excluded in alignment with this review’s objective to characterise sociodemographic data reporting practices for a relatively homogenous and rigorous set of studies. The DMHIs must have been primarily designed (1) to help patients with mental health disorders (eg, depression) or well-being concerns (eg, stress) and (2) for use on a personal mobile device delivered through a downloadable smartphone app (eg, in the App Store and Google Play) that could be used outside of a clinic setting. The articles must have been available in English and published in a peer-reviewed journal (ie, not a conference abstract or dissertation). No restrictions were placed on the country of study origin or RCT control group type. Articles published from 1 January 2007 onward were included in the review, reflecting the launch of the first major mobile app store in 2007. DMHIs with an adjunct or combined therapeutic intervention were included as long as the primary intervention remained the app-based component. We excluded studies not primarily focused on app-based DMHIs, including virtual reality, computer-delivered or video/phone-delivered psychotherapies and interventions delivered primarily through messaging-based apps (eg, WeChat and WhatsApp). To avoid double-counting studies that produced multiple papers, only primary studies were included in this review.

Information sources

The search queried five databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Google Scholar and PsyArXiv. A three-step search strategy was used to develop the keyword search string in this scoping review per JBI guidelines.48 First, a search of MEDLINE and CINAHL was conducted to identify articles on this topic. The keyword string for our initial search was developed by reviewing search strings used in systematic literature reviews cited within a recent meta-analysis of mobile DMHIs.50 Second, a comprehensive and non-repetitive list of relevant keywords, used inclusively in these studies,50 was used to develop the keyword search string for the preliminary search. Third, a preliminary search was conducted to identify additional keywords not included in the previous steps. Following recommendations by JBI48 to ensure a comprehensive keyword string, on 3 August 2022, the preliminary search was conducted in MEDLINE and CINAHL for the first three results meeting the inclusion criteria. Titles and abstracts from these first three citations were reviewed for relevant keywords. Modifications to the original search string from steps 1 and 2 incorporated terms found within the first three citations that were not included in the original search string. With the addition of new terms (psychological, psychology, behavioural, mindfulness, oppositional defiant disorder, fatigue and self-compassion), the keyword list for the full search string was considered final (see online supplemental file 2).

bmjopen-2023-078029supp002.pdf (52.3KB, pdf)

Search strategy

The search was conducted on 9 August 2022. Following recommendations from Haddaway and colleagues, Google Scholar results were limited to the first 200 citations due to the reduced quality and relevance of citations beyond this point.51 Citations from the full search were uploaded into individual Zotero folders based on the search database, with duplicates removed during the import process to Zotero (Zotero V.6.0.4, 2022) and export process (EBSCO). A flow diagram of the search results is reported in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of study inclusion.

Study selection process

Prior to commencing screening, two reviewers (LQ and JAK) conducted an exercise of title and abstract review to independently include or exclude the first 200 citations. Inter-rater agreement for citation inclusion was calculated using per cent agreement and 81% agreement was reached, meeting JBI recommendations48 of 75% needed to proceed to the next stage of the title and abstract review of all screened studies. No lower agreement calculations than reported here were observed during the process. Discrepancies were resolved with an additional reviewer (AKQ). Where a decision could not be made between the three reviewers (LQ, JAK and AKQ) to include or exclude a citation, the three reviewers and two arbitrators (AR and CJG) reviewed the citation together to reach a resolution. Following the completion of the title and abstract review, full-text articles were retrieved for all included citations. The full-text citations were subsequently assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria by two reviewers. Two reviewers (LQ and JAK) screened the first 100 full-text studies and reached 80% agreement.

Data items and data extraction process

For full-text articles meeting inclusion criteria, reviewers extracted data independently and reviewed discrepancies. Due to the quantity of citations meeting inclusion criteria, additional coders were added to the research team and received training equivalent to the original coders. Data charting was completed in duplicates by seven independent reviewers (LQ, JAK, MC, MP, RM, SP and SR), and discrepancies were resolved with an additional reviewer (AKQ or RM). The extracted variables were conceptualised with the intent of capturing the full breadth of sociodemographic identity domains (eg, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age, etc.) reported in the RCTs that met inclusion criteria. After reviewing several articles and guidelines for sociodemographic reporting to ensure we had considered a comprehensive set of domains,36 40 41 the authors aligned on the inclusion of a broad array of 16 sociodemographic domains for data extraction (see table 1). Citations that reported on secondary analysis of an RCT otherwise meeting inclusion criteria were excluded in this phase, and confirmation was subsequently provided that the primary citation was included for data extraction. A list of coded variables is provided in online supplemental file 3. The final dataset of all included studies is available in online supplemental file 4. Consistent with the guidance report developed by members of JBI and JBI Collaborating Centres, we did not conduct a critical appraisal of the methodological quality or risk of bias of the included citations.52

Table 1.

Number and percentage of studies that reported each sociodemographic domain

| Sociodemographic domain | Study count (%) ‘N’ possible=299 |

| Gender or sex | 293 (98%) |

| Gender only | 152 (51%) |

| Sex only | 85 (28%) |

| Gender and sex | 2 (<1%) |

| Gender/sex unspecified but reported | 54 (18%) |

| Age | 290 (97%) |

| Education | 200 (67%) |

| Race or ethnicity | 144 (48%) |

| Race only | 41 (14%) |

| Ethnicity only | 43 (14%) |

| Both race and ethnicity distinctly reported, ethnicity unspecified but reported | 31 (10%) |

| Race or ethnicity unspecified but reported | 29 (10%) |

| Employment | 127 (42%) |

| Marital status | 116 (39%) |

| Income level | 49 (16%) |

| Housing situation | 19 (6%) |

| Residency or location | 14 (5%) |

| Veteran status | 11 (4%) |

| Number of children | 8 (3%) |

| Sexual orientation | 7 (2%) |

| Disability status | 7 (2%) |

| Food security | 1 (<1%) |

Note: Gender, sex, race and ethnicity are each counted as a distinct domain, resulting in a total of 16 domains.

bmjopen-2023-078029supp003.pdf (47.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-078029supp004.xlsx (214.1KB, xlsx)

Results

Study characteristics

There were no included studies published in 2007 and 2008; thus, the 299 studies included in the review were published between 2009 and 2022, with over three-quarters published after 2018 (online supplemental table 1). Approximately 35% were conducted in the USA, and 59% of the studies recruited a sample of participants with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5 clinical diagnoses,53 with 16% including secondary medical or other physical diagnoses (eg, chronic pain, multiple sclerosis, etc) as part of the inclusion criteria. The vast majority (85%) presented sociodemographics separately for each treatment arm, but few studies presented separate sociodemographics for study dropouts (7%) or analysed the primary outcomes separately by different sociodemographic categories (12%).

bmjopen-2023-078029supp007.pdf (47.5KB, pdf)

Primary objectives

Primary objective 1

What are the common sociodemographic domains reported in RCTs of DMHIs and how frequently is each sociodemographic domain reported?

On average, across the 299 included studies, researchers reported 4.64 (SD=1.79; range 0–9) of the 16 sociodemographic domains assessed in this review (see table 1 and figure 2 for the number and percentage of studies that reported data for each of the 16 sociodemographic domains included in this review). The most commonly reported sociodemographic domains were age (97%, n=290 studies), education (67%, n=200) and gender (51%, n=152). The least common domains were housing situation (eg, living alone, with parents, homeless, etc; 6%, n=19), residency/location (eg, rural vs urban; 5%, n=14), veteran status (4%, n=11), number of children (3%, n=8), sexual orientation (2%, n=7), disability status (2%, n=7) and food security (<1%, n=1).

Figure 2.

Percentage of studies that reported each sociodemographic domain. Percentages were rounded to the nearest whole number; the domains of gender or sex and race or ethnicity were combined in the figure for visual clarity.

Reporting of gender/sex and race/ethnicity domains

Due to the observed common conflation of gender and sex, the domains of gender and sex were coded into the following buckets for clarity: ‘gender only’, ‘sex only’, ‘gender and sex’ and ‘gender/sex unspecified but reported’ (see online supplemental figure 1). ‘Gender or sex’ represents the combination of these categories. ‘Gender and sex’ reflects instances in which the publication reported both sociodemographic domains separately. ‘Gender/sex unspecified but reported’ represents instances in which publications reported categories reflecting gender or sex but did not specify which domain the category belonged to. For example, several of these studies included in their sociodemographic reporting the proportion of participants who were women but did not indicate whether this was intended to capture participants’ gender or their sex. Following the same logic, the domains of race and ethnicity were coded into the following buckets: ‘race only’, ‘ethnicity only’, ‘race and ethnicity’ and ‘race/ethnicity unspecified but reported’ (see online supplemental figure 2).

bmjopen-2023-078029supp005.pdf (156.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-078029supp006.pdf (164.6KB, pdf)

Unlisted sociodemographic domains

To ensure the breadth of sociodemographic domains was thoroughly captured, the present review also documented domains that were not included in the 16 domains reviewed (called ‘unlisted’). There were 35 studies (12%) that reported unlisted sociodemographic domains. Five main clusters emerged: there were 10 studies that documented ‘nationality’, six studies that documented ‘parental education’, five studies that documented ‘languages’, three studies that documented ‘religion’ and three studies that documented ‘subjective socioeconomic status’.

Primary objective 2

What are the commonly reported category options within each sociodemographic domain?

Descriptives for the two most common categories are provided in table 2 (eg, ‘high school’, ‘college/university degree’), reported within each sociodemographic domain (eg, education), as well as the highest and lowest reported number of category descriptors (range).

Table 2.

Number of categories reported per sociodemographic domain

| Sociodemographic domain | Range | Two most common categories |

| Education | 1–13 | ‘High school’ ‘College/university degree’ |

| Employment | 1–10 | ‘Employed’ ‘Unemployed’ |

| Marital status | 1–6 | ‘Married’ ‘Single’ |

| Income level* | 1–8 | NA |

| Housing situation | 1–7 | ‘Living alone’ ‘Living with others’ |

| Residency/location | 1–4 | ‘Urban’ ‘Rural’ |

| Veteran status | 1–6 | ‘Veteran’ |

| Number of children† | NA | Continuous number (eg, ‘3’) |

| Sexual orientation | 1–7 | ‘Heterosexual’ ‘Gay or lesbian’ |

| Disability status‡ | 1–3 | ‘Disability/disabled’ |

| Food security† | NA | Continuous percentage (eg, 30%) |

| Gender or sex | ||

| Gender only | 1–6 | ‘Male’ ‘Female’ |

| Sex only | 1–3 | ‘Male’ ‘Female’ |

| Gender/sex unspecified but reported | 1–2 | ‘Female’ ‘Male’ |

| Gender and sex | ||

| Gender | 2–3 | ‘Male’ ‘Female’ |

| Sex | 1–2 | ‘Male’ ‘Female’ |

| Race or ethnicity | ||

| Race only§ | 1–7 | ‘White’ ‘African American/Black’ |

| Ethnicity only | 1–9 | ‘White/Caucasian’ ‘Other’ |

| Both race and ethnicity distinctly reported¶ | ||

| Race | 1–6 | ‘Black/African American’ ‘White/Caucasian’ |

| Ethnicity | 1–3 | ‘Hispanic or Latino/a’ ‘Non-Hispanic or Latino/a’ |

| Race or ethnicity unspecified but reported | 1–9 | ‘White/Caucasian’ ‘African American/Black’ |

*For ‘income level’, nearly all category options included a numeric range of salary (eg, ‘less than $25 000’, ‘$25 001–$49 999’, etc); however, the particular cut-offs varied widely and were not easily interpretable for summarisation here.

†The range was not calculable (‘NA’) for ‘number of children’ and ‘food security’, as these domains were reported with a single continuous number or percentage.

‡For ‘disability status’, the most frequently reported option was a variation of ‘disability’ or ‘disabled’, though we are combining across several variations for simplicity of reporting due to the small sample size.

§For ‘race only’ and ‘race or ethnicity unspecified but reported’, for the category ‘African American/Black’, we combined across categories, including ‘African American’, ‘African’, ‘Black’ and ‘Black or African American’.

¶For ‘both race and ethnicity distinctly reported’, for category ‘Hispanic or Latino/a’, we combined across categories, including ‘Hispanic’, ‘Latino/a’ and ‘Latinx’.

Exploratory objective 1

Does the reporting of sociodemographic domains appear to differ between US and non-US countries?

Reporting of sociodemographic domains was fairly consistent across US-based and non-US-based studies (see online supplemental table 2). However, several domains appeared to differ, including race, ethnicity, employment and veteran status. Ninety per cent of US studies reported on race or ethnicity, whereas 25% of non-US studies did so. US studies appear to have reported more frequently than non-US studies for race only (31% vs 4%), both race and ethnicity (27% vs 2%) and race or ethnicity unspecified (24% vs 2%). However, US studies appear to have reported less frequently for ethnicity only (9% vs 18%). For employment, 46% of non-US studies reported, compared with 36% of US studies. Finally, veteran status was reported by 10% of US studies but less than 1% of non-US studies.

bmjopen-2023-078029supp008.pdf (37.5KB, pdf)

Exploratory objective 2

Does the reporting frequency of sociodemographic domains appear to change over time?

To determine whether there were possible changes in reporting of sociodemographic domains over time, studies were divided into three subgroups, each covering 4–5 years from 2009 to 2022, and the frequency of domains reported was described (online supplemental table 3). There was an increase in total publications across time, with five studies published between 2009 and 2013, 65 between 2014 and 2018 and 229 between 2019 and 2022. The average number of domains reported was M=3.00 (SD=2.12) in the first period, M=4.55 (SD=1.57) in the second and M=4.47 (SD=1.84) in the third, suggesting an initial modest increase after 2013 followed by a possible plateau in more recent years. Reporting prevalence over time also appears to have varied from domain to domain. Age and gender/sex have been consistently reported by nearly all studies over time; education notably increased (from 20% to approximately 70%); employment and race or ethnicity have been fairly stable around 40% and 50%, respectively, and most other domains were not reported at all in the first 5 years but began to appear at least occasionally after 2014. There also appears to be a decrease over time in both the proportion of studies that reported residency or location, ethnicity only (ie, not race) and those that reported but did not specify gender or sex. Overall, the descriptive trends suggest a modest increase in publications reporting sociodemographic domains in more recent years, though these should be interpreted cautiously due to variability and the different sample sizes of each period.

bmjopen-2023-078029supp009.pdf (42.9KB, pdf)

Discussion

The first primary research objective of this scoping review was to describe common sociodemographic domains and how frequently they were reported in DMHI research. Our comprehensive review of 299 RCTs of app-based DMHIs published from 2007 to 2022 found that this research underreported key sociodemographic data. Across the 16 sociodemographic domains reviewed, the average number of domains reported per study was 4.6, and no domains were consistently reported across studies. Only three domains (age, education and gender) were reported in greater than 50% of studies, and seven domains (housing situation, residency/location, veteran status, number of children, sexual orientation, disability and food security) were reported in fewer than 10% of studies. The remaining domains (sex, race, ethnicity, employment, marital status and income level) were reported between 10% and 42% of the time. Similar proportions of limited sociodemographic reporting have been described in reviews of the broader clinical research literature.29 30 For example, Orkin and colleagues found over 98% reporting of age and gender or sex, but only 48.5% for race or ethnicity,33 nearly identical to our findings here. Contrastingly, the DMHI literature surveyed here reported education (67%), employment (42%) and marital status (39%) at higher rates than those reported by Orkin et al (all below 15%).33

The second primary objective was to describe the commonly reported categories within the sociodemographic domains. Category reporting was often incomplete (eg, % female only), unclear (eg, the conflation of gender and sex and race and ethnicity) and limited (eg, only options representing majority groups were offered). In particular, reporting practices for the domains of gender, sex, and sexual orientation demonstrated widespread shortcomings, including limited reporting and apparent conflation across these domains. Gender and sex were commonly used interchangeably; however, these terms represent distinct definitions in contemporary science.54 Sex refers to the biologically assigned classification of male or female according to genetic, anatomical and hormonal characteristics.54 55 Gender identity refers to socially constructed roles, behaviours and identities generally (but not necessarily) associated with an individual’s sex.54 55 Importantly, gender may not align with an individual’s assigned sex at birth, and individuals may identify as transgender, genderqueer, non-binary or other genders that do not conform to traditional categories. Recognition of this is evident in only two studies that reported both sex and gender as separate, distinct domains. Moreover, the most frequently reported number of category options for gender and sex was two, and these were ‘male’ and ‘female’ for both, suggesting that researchers are regularly conflating gender and sex. Additionally, fewer than 1 in 20 studies reported options inclusive of the broader spectrum of gender identities, such as transgender man or woman, genderfluid or non-binary, indicating that the vast majority of researchers are omitting inclusive options. Finally, there was a near total absence of reporting on sexual orientation, with just 2% of studies reporting on this domain. The omission of reporting for marginalised sexual and gender identities has also been demonstrated by Kimber and colleagues30 in a review of psychological interventions for physical health and by Pachinkis and colleagues in a review of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ+) affirming mental healthcare.56 Despite these gaps in reporting and representation, it has become clear that the LGBTQ+ community experiences social stigma, rejection, violence and discrimination—all factors that contribute to high rates of depression, anxiety, substance use and suicidal ideation.4 57–59 Fortunately, these pressing issues are gaining wider recognition; for example, in 2021, the US Census Bureau attempted for the first time to collect data on LGBTQ+ Americans in a large real-time national survey.60 These efforts, while modest, are encouraging. The continued collection and reporting on sexual orientation and gender identity is essential to serving members of the LGBTQ+ community.

Race and ethnicity were also not widely reported, regularly conflated, and limited in their options for self-identification. Fewer than half of the studies reported on either race or ethnicity at all, and of those that did, reporting practices were varied and inconsistent. Following the most recent 2021 guidance published by Flanagin and colleagues,37 race and ethnicity are defined as social constructs that are not biologically based. Specifically, race typically refers to a social construct that categorises people based on physical characteristics, whereas ethnicity refers to a shared cultural heritage, geographical origin and ancestry. The lack of specificity observed in many studies appears to have resulted in a profusion of category options mixed indiscriminately across both domains, such as ‘white/caucasian’ (which typically refers to race) appearing under ethnicity and ‘Hispanic’ (which typically refers to ethnicity) appearing as an option under race. Nearly all of the studies that did distinctly report both race and ethnicity were published in the USA after 2018, which may reflect the influence of recent NIH, US Food and Drug Administration and US Census Bureau guidelines.39 61 62

Relatedly, our first exploratory objective was to explore potential differences in reporting patterns between US and non-US countries. While there were no obvious trends for most domains, we observed that reporting practices regarding race and ethnicity differed between the US and non-US countries. Studies published in the USA were 3.6 times more likely to report either race or ethnicity (90%; n=95/105) than non-US studies (25%; n=49/194). This may be due in part to international variations in racial and ethnic diversity, which may correspond to differing reporting practices, guidelines, and factors affecting the perception and influence of race and ethnicity cross-culturally.34 For example, guidelines published by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review recognise the possibility of barriers to the recruitment of diverse racial and ethnic samples in multinational trials and, as such, only apply racial and ethnic diversity ratings to US-based trials.63 Nonetheless, continued improvement in data collection and reporting practices regarding race and ethnicity is critical, especially in the USA where members of marginalised racial and ethnic groups show higher rates of being undiagnosed or underdiagnosed for mental health conditions64 and barriers such as stigma, discrimination, and lack of access to care further contribute to hesitancy in seeking mental healthcare.65–69

Our second exploratory objective described a potential change in sociodemographic reporting frequency over time. Consistent with other recent reviews,29 trends suggest that the frequency of reporting across sociodemographic domains has generally, if modestly, increased over time. A number of converging factors may play a role in this trend, including efforts put forth by advocacy and special interest groups, advances in social justice movements, growing awareness and emphasis on diversity in scientific conferences and educational curricula, as well as the publication of guidelines and funding requirements by organisations such as the NIH and ICH.

Future directions

Ongoing improvements in sociodemographic reporting are critical to studying and understanding DMHI’s impact across diverse populations. While there are many possible approaches to advancing this pursuit, including policy and advocacy, Call and colleagues note recommendations and questions for researchers to consider regarding the collection and analysis of demographic data in psychological research,34 such as the inclusion of evidence-based demographic questionnaires, avoidance of forced-choice answers and allowance of multiselect and open-ended answers. The authors also advocate for inviting those impacted by the research into dialogue with researchers regarding the use of study-derived data. Such recommendations, when used in combination with NIH, ICH, and other guidelines, may accelerate improved sociodemographic reporting.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths. It is the first of its kind to assess sociodemographic reporting practices in RCTs of app-based DMHIs and lays the foundation for the improvement of sociodemographic data collection and reporting in future studies. This review was both large and comprehensive, screening over 5000 article abstracts leading to the inclusion of nearly 300 articles spanning the entire lifespan of app-based DMHIs and extracting data for a wide array of 16 sociodemographic domains. Article inclusion criteria allowed for the review of a broad range of DMHI studies, including global populations with both clinical and subclinical conditions. There were also several limitations. This scoping review did not describe the actual composition of each study sample due to the large number of studies included in the review and the breadth of domains evaluated. This review was also merely descriptive; quantitative analyses such as formal assessment of statistical differences across reporting practices or time periods were beyond the review’s scope, and results should be interpreted accordingly.

Conclusion

In summary, the DMHI literature does not appear to be exempt from the sociodemographic reporting challenges that have been observed in other domains of clinical literature. This scoping review describes the widespread underreporting of sociodemographic information in RCTs of app-based DMHIs published globally from 2007 to 2022. No sociodemographic domain was consistently reported across all 299 studies and reporting was often incomplete, unclear and limited. Trends did suggest improvements in reporting in recent years, which may be a result of ongoing and growing efforts and awareness brought to issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion in science and healthcare.

All clinical research, including DMHI research, should optimally inquire about and study the personal, social, cultural, environmental, and economic variables that shape the lives of study participants. Doing so will help determine how such sociodemographic domains interact with, predict, and facilitate mental health outcomes and other key variables of interest (eg, treatment satisfaction). Thorough collection and reporting of these sociodemographic data will necessarily create opportunities for enhanced learning and understanding of diverse populations. Equipped with such knowledge and data, DMHI researchers may outline the potential generalisability of their results as well as create and study treatment adaptations as indicated. Ultimately, improved sociodemographic collection and reporting practices would enhance the diversity of DMHI literature overall and also better position DMHIs to facilitate reducing disparities in mental healthcare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Adam Platt, MSc, for coordinating scientific communications and facilitating the organization of the manuscript preparation and submission.

Footnotes

Contributors: AKQ in collaboration with AR, PW, AD, JK, LQ and CJG conceptualised and designed the study and drafted the protocol. JK and LQ, in coordination with AKQ, conducted the database search, title/abstract screening and full-text screening. AKQ, JK and LQ, with support from MC, MCP, RM, SP and SR, completed data extraction. AR and CJG moderated discrepancy resolution throughout. Data synthesis and analysis were completed by AKQ, RM and MC. MC, MCP, AR and CJG drafted the background section. JK drafted the methods section and completed Supplemental 2 (search strings/terms to identify included papers) and 3 (variable descriptions). JK, RM and AKQ created figure 1 and PRISMA-ScR requirements (online supplemental file 1). RM and MC drafted the results and discussion sections. MCP prepared the reference section, and RM prepared the final dataset (online supplemental file 4). All authors contributed to multiple draft revisions, with ownership for incorporation of all author edits and flow of overall manuscript championed by RM, MC and AR. All authors read and approved the submitted version. AR is acting as guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by Woebot Health. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Funding to publish this article as open access was provided by Woebot Health.

Competing interests: AKQ, MC, MCP, SR, SP, RM, AD and AR are all employees of Woebot Health. RM is a former employee of Twill. PW is an associate editor at the Journal of Medical Internet Research and is on the editorial advisory boards of BMC Medicine, The Patient and Digital Biomarkers. PW is employed by Wicks Digital Health Ltd, which has received funding from Ada Health, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bold Health, Corevitas, EIT, Endava, Happify, HealthUnlocked, Inbeeo, Kheiron Medical, Lindus Health, MedRhythms, Okko Health, PatientsLikeMe, Sano Genetics, The Learning Corp, The Wellcome Trust, THREAD Research, United Genomics, VeraSci and Woebot Health. PW and spouse are shareholders of WDH Investments, which owns stock in Avayl Gmbh, BlueSkeye AI, Earswitch, Lucida Medical, Sano Genetics and Una Health Gmbh. CJG is a consultant to Woebot Health. CJG would like to acknowledge support provided by the Center for Childhood Obesity Prevention funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20GM109096 (Arkansas Children’s Research Institute, PI: Weber) and by the Translational Research Institute funded by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1 TR003107 (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, PI: James). The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. JK and LQ are contractors to Woebot Health. JK is a former employee of PatientsLikeMe and has received funds as a consultant from PatientsLikeMe and EHIR.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. The dataset underlying the results of this study is published in online supplemental file 4.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Baah FO, Teitelman AM, Riegel B. Marginalization: conceptualizing patient vulnerabilities in the framework of social determinants of health-An integrative review. Nurs Inq 2019;26:e12268. 10.1111/nin.12268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schueller SM, Hunter JF, Figueroa C, et al. Use of digital mental health for marginalized and underserved populations. Curr Treat Options Psych 2019;6:243–55. 10.1007/s40501-019-00181-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson JW, Williams DR, VanderWeele TJ. Disparities at the intersection of marginalized groups. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2016;51:1349–59. 10.1007/s00127-016-1276-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu RT, Sheehan AE, Walsh RFL, et al. Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2019;74:101783. 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke LA, Chijioke S, Le TP. Gendered racial microaggressions and emerging adult Black women’s social and general anxiety: distress intolerance and stress as mediators. J Clin Psychol 2023;79:1051–69. 10.1002/jclp.23460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacIntyre MM, Zare M, Williams MT. Anxiety-related disorders in the context of racism. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2023;25:31–43. 10.1007/s11920-022-01408-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Leon AN, Woerner J, Dvorak RD, et al. An examination of discrimination on stress, depression, and oppression-based trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic and the racial awakening of 2020. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 2023;7:24705470231152953. 10.1177/24705470231152953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mongelli F, Perrone D, Balducci J, et al. Minority stress and mental health among LGBT populations: an update on the evidence. Minerva Psichiatr 2019;60:27–50. 10.23736/S0391-1772.18.01995-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey RK, Mokonogho J, Kumar A. Racial and ethnic differences in depression: current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2019;15:603–9. 10.2147/NDT.S128584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaniuka A, Pugh KC, Jordan M, et al. Stigma and suicide risk among the LGBTQ population: are anxiety and depression to blame and can connectedness to the LGBTQ community help? JGLMH 2019;23:205–20. 10.1080/19359705.2018.1560385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roohafza H, Sadeghi M, Shirani S, et al. Association of socioeconomic status and life-style factors with coping strategies in Isfahan healthy heart program, Iran. Croat Med J 2009;50:380–6. 10.3325/cmj.2009.50.380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benner AD, Wang Y. Adolescent substance use: the role of demographic marginalization and socioemotional distress. Dev Psychol 2015;51:1086–97. 10.1037/dev0000026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford JD, Grasso DJ, Elhai JD, et al. Social, cultural, and other diversity issues in the traumatic stress field. Posttraumatic Stress Disord 2015:503–46. 10.1016/B978-0-12-801288-8.00011-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorant V, Deliège D, Eaton W, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:98–112. 10.1093/aje/kwf182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watkins DC, Assari S, Johnson-Lawrence V. Race and ethnic group differences in comorbid major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and chronic medical conditions. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2015;2:385–94. 10.1007/s40615-015-0085-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maura J, Weisman de Mamani A. Mental health disparities, treatment engagement, and attrition among racial/ethnic minorities with severe mental illness: a review. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2017;24:187–210. 10.1007/s10880-017-9510-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization . World mental health report: transforming mental health for all. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polo AJ, Makol BA, Castro AS, et al. Diversity in randomized clinical trials of depression: a 36-year review. Clin Psychol Rev 2019;67:22–35. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mak WWS, Law RW, Alvidrez J, et al. Gender and ethnic diversity in NIMH-funded clinical trials: review of a decade of published research. Adm Policy Ment Health 2007;34:497–503. 10.1007/s10488-007-0133-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma A, Palaniappan L. Improving diversity in medical research. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021;7:74. 10.1038/s41572-021-00316-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, et al. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010;21:879–97. 10.1353/hpu.0.0323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau AS, Chang DF, Okazaki S. Methodological challenges in treatment outcome research with ethnic minorities. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2010;16:573–80. 10.1037/a0021371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naeem F, Phiri P, Rathod S, et al. Cultural adaptation of cognitive–behavioural therapy. BJPsych Advances 2019;25:387–95. 10.1192/bja.2019.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institutes of Health . NIH guidelines: inclusion of women and minorities. 2016. Available: https://grants.nih.gov/policy/inclusion/women-and-minorities/guidelines.htm

- 25.National Institutes of Health . NIH inclusion outreach Toolkit: how to engage, recruit, and retain women in clinical research. 2023. Available: https://orwh.od.nih.gov/toolkit/nih-policies-inclusion/guidelines

- 26.Naito C. Ethnic factors in the acceptability of foreign clinical data. Drug Information Journal 1998;32:1283S–1292S. 10.1177/00928615980320S121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Food and Drug Administration . Collection, analysis, and availability of demographic subgroup data for FDA-approved medical products. 2013. Available: https://www.fda.gov/files/about%20fda/published/Collection--Analysis--and-Availability-of-Demographic-Subgroup-Data-for-FDA-Approved-Medical-Products.pdf

- 28.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Policy and Global Affairs, Committee on Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Committee on Improving the Representation of Women and Underrepresented Minorities in Clinical Trials and Research . Policies to improve clinical trial and research diversity: history and future directions. In: Bibbins-Domingo K, Helman A, eds. Improving representation in clinical trials and research: building research equity for women and underrepresented groups. National Academies Press, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burnette CB, Luzier JL, Weisenmuller CM, et al. A systematic review of sociodemographic reporting and representation in eating disorder psychotherapy treatment trials in the United States. Int J Eat Disord 2022;55:423–54. 10.1002/eat.23699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimber JM, Ertl MM, Egli MR, et al. Psychotherapies for clients with physical health conditions: a scoping review of demographic reporting. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2022;59:209–22. 10.1037/pst0000397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madnick D, Spokas M. Reporting and inclusion of specific sociodemographic groups in the adult PTSD treatment outcome literature within the United States: a systematic review. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract 2022;29:311–21. 10.1037/cps0000067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner BE, Steinberg JR, Weeks BT, et al. Race/ethnicity reporting and representation in US clinical trials: a cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Am 2022;11:100252. 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orkin AM, Nicoll G, Persaud N, et al. Reporting of sociodemographic variables in randomized clinical trials, 2014-2020. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2110700. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Call CC, Eckstrand KL, Kasparek SW, et al. An ethics and social-justice approach to collecting and using demographic data for psychological researchers. Perspect Psychol Sci 2023;18:979–95. 10.1177/17456916221137350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dresser R. Silent Partners: Human Subjects and Research Ethics. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Psychological Association . Inclusive language guidelines. 2021. Available: https://www.apa.org/about/apa/equity-diversity-inclusion/language-guidelines

- 37.Flanagin A, Frey T, Christiansen SL, et al. Updated guidance on the reporting of race and ethnicity in medical and science journals. JAMA 2021;326:621–7. 10.1001/jama.2021.13304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Federal Register . Initial proposals for updating OMB’s race and ethnicity statistical standards. 2023. Available: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/01/27/2023-01635/initial-proposals-for-updating-ombs-race-and-ethnicity-statistical-standards

- 39.National Institutes of Health . Guidelines for the review of inclusion on the basis of sex/gender, race, ethnicity, and age in clinical research. 2019. Available: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/peer/guidelines_general/Review_Human_subjects_Inclusion.pdf

- 40.Commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Collection of race and Ethnicity data in clinical trials. 2016. Available: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/collection-race-and-ethnicity-data-clinical-trials

- 41.Park A. Data collection methods for sexual orientation and gender identity. 2016. Available: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/data-collection-sogi/

- 42.Friis-Healy EA, Nagy GA, Kollins SH. It Is Time to REACT: opportunities for digital mental health apps to reduce mental health disparities in racially and ethnically minoritized groups. JMIR Ment Health 2021;8:e25456. 10.2196/25456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lattie EG, Stiles-Shields C, Graham AK. An overview of and recommendations for more accessible digital mental health services. Nat Rev Psychol 2022;1:87–100. 10.1038/s44159-021-00003-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aboujaoude E, Gega L, Parish MB, et al. Editorial: digital interventions in mental health: current status and future directions. Front Psychiatry 2020;11. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heck NC, Mirabito LA, LeMaire K, et al. Omitted data in randomized controlled trials for anxiety and depression: a systematic review of the inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity. J Consult Clin Psychol 2017;85:72–6. 10.1037/ccp0000123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geller SE, Koch AR, Roesch P, et al. The more things change, the more they stay the same: a study to evaluate compliance with inclusion and assessment of women and minorities in randomized controlled trials. Academic Medicine 2018;93:630–5. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murray TM, Ware CMU. Addressing disparities by diversifying behavioral health research. 2022. Available: https://www.samhsa.gov/blog/addressing-disparities-diversifying-behavioral-health-research

- 48.Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI, 2020. Available: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flecha OD, Douglas de Oliveira DW, Marques LS, et al. A commentary on randomized clinical trials: how to produce them with a good level of evidence. Perspect Clin Res 2016;7:75–80. 10.4103/2229-3485.179432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldberg SB, Lam SU, Simonsson O, et al. Mobile phone-based interventions for mental health: a systematic meta-review of 14 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. PLOS Digit Health 2022;1:e0000002. 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, et al. The role of Google scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLOS ONE 2015;10:e0138237. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–6. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garofalo EM, Garvin HM. Chapter 4 - the confusion between biological sex and gender and potential implications of Misinterpretations. In: Klales AR, ed. Sex Estimation of the Human Skeleton. Academic Press, 2020: 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes PJ, et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet 2020;396:565–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pachankis JE. The scientific pursuit of sexual and gender minority mental health treatments: toward evidence-based affirmative practice. Am Psychol 2018;73:1207–19. 10.1037/amp0000357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hatchel T, Polanin JR, Espelage DL. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among LGBTQ youth: meta-analyses and a systematic review. Arch Suicide Res 2021;25:1–37. 10.1080/13811118.2019.1663329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, et al. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health 2013;103:943–51. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fish JN. Future directions in understanding and addressing mental health among LGBTQ youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2020;49:943–56. 10.1080/15374416.2020.1815207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carrazana C, Rummler O. The Census Bureau’s first ever data on LGBTQ+ people indicates deep disparities. 2021. Available: https://19thnews.org/2021/09/lgbtq-census-data-federal-collection-first-time/ [Accessed 10 Jul 2023].

- 61.US Census Bureau . Race. Available: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/note/US/RHI625222 [Accessed 28 Jun 2023].

- 62.Jensen E, Jones N, Orozco K, et al. Measuring racial and ethnic diversity for the 2020 census. 2021. Available: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2021/08/measuring-racial-ethnic-diversity-2020-census.html [Accessed 07 Jul 2023].

- 63.Agboola F, Whittington M, Pearson S. Advancing health technology assessment methods that support health equity [Institute for Clinical and Economic Review]. 2023. Available: https://icer.org/assessment/health-technology-assessment-methods-that-support-health-equity-2023/

- 64.Blue Cross Blue Shield . Racial disparities in diagnosis and treatment of major depression. 2022. Available: https://www.bcbs.com/the-health-of-america/reports/racial-disparities-diagnosis-and-treatment-of-major-depression [Accessed 28 Jun 2023].

- 65.McGuire TG, Miranda J. New evidence regarding racial and ethnic disparities in mental health: policy implications. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:393–403. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McGregor B, Belton A, Henry TL, et al. Improving behavioral health equity through cultural competence training of health care providers. Ethn Dis 2019;29:359–64. 10.18865/ed.29.S2.359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cokley K, Krueger N, Cunningham SR, et al. The COVID-19/racial injustice syndemic and mental health among Black Americans: the roles of general and race-related COVID worry, cultural mistrust, and perceived discrimination. J Community Psychol 2022;50:2542–61. 10.1002/jcop.22747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Henderson C, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G. Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. Am J Public Health 2013;103:777–80. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Knaak S, Mantler E, Szeto A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare. Healthc Manage Forum 2017;30:111–6. 10.1177/0840470416679413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-078029supp001.pdf (67.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-078029supp002.pdf (52.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-078029supp003.pdf (47.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-078029supp004.xlsx (214.1KB, xlsx)

bmjopen-2023-078029supp007.pdf (47.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-078029supp005.pdf (156.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-078029supp006.pdf (164.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-078029supp008.pdf (37.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-078029supp009.pdf (42.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. The dataset underlying the results of this study is published in online supplemental file 4.