Abstract

Introduction

Recent evidence supports the contribution of gut microbiota dysbiosis to the pathophysiology of rheumatic diseases, neuropathic pain, and neurodegenerative disorders. The bidirectional gut-brain communication network and the occurrence of chronic pain both involve contributions of the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis. Nevertheless, the current understanding of the association between gut microbiota and chronic pain is still not clear. Therefore, the aim of this study is to systematically evaluate the existing knowledge about gut microbiota alterations in chronic pain conditions.

Methods

Four databases were consulted for this systematic literature review: PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Embase. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to assess the risk of bias. The study protocol was prospectively registered at the International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO, CRD42023430115). Alpha-diversity, β-diversity, and relative abundance at different taxonomic levels were summarized qualitatively, and quantitatively if possible.

Results

The initial database search identified a total of 3544 unique studies, of which 21 studies were eventually included in the systematic review and 11 in the meta-analysis. Decreases in alpha-diversity were revealed in chronic pain patients compared to controls for several metrics: observed species (SMD= -0.201, 95% CI from -0.04 to -0.36, p=0.01), Shannon index (SMD= -0.27, 95% CI from -0.11 to -0.43, p<0.001), and faith phylogenetic diversity (SMD -0.35, 95% CI from -0.08 to -0.61, p=0.01). Inconsistent results were revealed for beta-diversity. A decrease in the relative abundance of the Lachnospiraceae family, genus Faecalibacterium and Roseburia, and species of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Odoribacter splanchnicus, as well as an increase in Eggerthella spp., was revealed in chronic pain patients compared to controls.

Discussion

Indications for gut microbiota dysbiosis were revealed in chronic pain patients, with non-specific disease alterations of microbes.

Systematic review registration

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD42023430115.

Keywords: microbiota, gut-brain axis, persistent pain, biomarker, gut composition, stool samples

1. Introduction

The gut microbiota refers to the dynamic community of microorganisms inhabiting the gastro-intestinal tract, whereby the genetic and functional profile of microbial species is denoted as the gut microbiome (1, 2). During the last decade, several studies pointed out associations between alterations in microbiota composition and diverse host disease conditions, among those gastrointestinal conditions [e.g., irritable bowel syndrome (3), gastroduodenal diseases (4)] as well as more physically remote conditions among which neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, or multiple sclerosis) (5), or neuropsychiatric disorders (6). To accomplish these complex involvements, neuro-immune-endocrine mediators underlie the bidirectional communication network between the gut and the central nervous system, i.e. the gut-brain axis (7). As such, the gut-brain crosstalk ensures the proper maintenance of gastrointestinal homeostasis, while it also connects the emotional and cognitive centers of the brain with peripheral intestinal functions and mechanisms through immune activation, intestinal permeability, and entero-endocrine signaling (8).

The hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis, as part of the limbic system, is the core stress efferent axis that reacts with secretion of corticotropin-releasing factor from the hypothalamus in response to stressors of any kind (e.g., emotion or stress), consecutively leading to adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion from the pituitary gland, which in turn leads to cortisol release from the adrenal glands (9). While chronically elevated cortisol levels negatively affect brain function (10), HPA axis activation also alters the composition of the gut microbiota and increases gastrointestinal permeability (11), triggering an inflammatory response (12). Additionally, the autonomic nervous system drives both efferent signals from the central nervous system to the intestinal wall, mainly through vagal efferent fibers, and afferent signals from the lumen through enteric, spinal, and vagal pathways to the central nervous system (8). Unless the intestinal epithelium integrity is affected, whereby gut microbiota can directly interact with the vagal nerve, enteroendocrine cells recognize bacterial products or bacterial metabolites (e.g., short-chain fatty acids) to facilitate an indirect communication with vagal afferents through synaptic connections (13, 14). Additionally, production of bacterial metabolites (15), interference with the kynurenine pathway (16), and neuroendocrine signaling (17) contribute to the communication between the gut and the central nervous system.

Bidirectional interactions and connections between the pain regulatory system and the autonomic nervous system have been revealed (18), as well as altered sensitivity of the HPA axis in relation to chronic pain and stress (19), which are both suggestive of the involvement of the gut-brain axis in chronic pain due to shared pathways. Therefore, the aim of this study is to systematically evaluate the existing knowledge about gut microbiota alterations across a spectrum of chronic pain conditions.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol registration

This systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses) (20). The protocol was a priori registered in PROSPERO under registration number CRD42023430115.

2.2. Search strategy

The search strategy was conducted in four databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Scopus on June 3rd, 2023. All authors contributed to the development of the search strategy. The research question was created according to the PICOS (Population-Intervention-Control-Outcome-Study design) framework (21) to investigate perturbations in gut microbiota (Outcome) in chronic pain patients (Population). The final search strategy was built by combining both free and MeSH terms. Between each part of the PICO question, the Boolean operator AND was used. Within the components, search terms were combined using the Boolean operator OR. No limits were applied to this search strategy. The complete search strategy for PubMed can be found in Supplementary Datasheet 1 . After building the search string in PubMed, it was individually adapted for the other three databases.

2.3. Eligibility criteria

Studies evaluating gut microbiota in chronic pain patients, in comparison to controls, were eligible. All types of chronic pain [pain > 3 months according to ICD-11 criteria (22)] were included, with the exception of functional intestinal disorders. As study designs, both observational and experimental designs were allowed, as long as a control group of patients without chronic pain was included. Only studies exploring gut microbiota were incorporated. Studies reporting in languages other than English, Dutch, or French were excluded. Full eligibility criteria are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

In-and exclusion criteria applied during screening for the systematic review.

| *Topic | *Inclusion | *Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | - Chronic pain | - All types of chronic pain will be included, except for patients with functional intestinal disorders among which are irritable bowel syndrome, chronic ulceritis, functional abdominal pain, etc. - Animal studies, computational models |

| Control | - Healthy controls (defined as no presence of chronic pain) | |

| Design | - Observational designs (e.g. case-controls, cross-sectional, cohort designs) with cases and controls - Interventional or longitudinal comparisons with a control group. |

- Reviews, case reports, letters to the editor, opinion articles, editorials - Interventional or longitudinal comparisons in the absence of a control group. |

| Outcome | - Measures of gut microbiota composition (alpha and beta diversity) and taxonomic findings at the phylum, family, and genus levels (relative abundance). | - Measures of the HPA axis, not related to the gut microbiome - Other microbiome than gut microbiome for example urinary microbiome or skin microbiome. |

| Language | - English, Dutch, French | - Other languages |

HPA, hypothalamic pituitary adrenal.

2.4. Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened all retrieved articles for title and abstract using online software Rayyan, after de-duplication in both EndNote X9 and Rayyan. During the next phase, two reviewers independently performed full text screening. In case of conflicts at each stage, they were resolved in a consensus meeting with a third reviewer.

2.5. Data extraction

The relevant data were selected by an a priori developed data extraction form with information on publication details, participant demographic and clinical characteristics, and methodological information. As outcomes of interest, community-level measures of gut microbiota composition (alpha- and beta-diversity) and taxonomic findings at the phylum, family, genus, and species levels (relative abundance) were extracted. The alpha-diversity refers to the variation within an individual sample (i.e. microbial community) with a differentiation between richness (i.e. number of species) and evenness (i.e. how well each species is represented), while beta-diversity refers to the variation between samples (2, 23). The data extraction table was composed by one reviewer and checked for correctness by another reviewer. Any sort of discrepancies were discussed in a consensus meeting between both reviewers.

2.6. Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), a tool developed for the purposes of evaluating nonrandomized studies used in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (24, 25). This scale is designed to assess the selection of participants (four items), comparability (one item), and exposure (three items) domains. A total NOS score ≤ 5 was considered as low quality, a score of 6 or 7 as moderate quality, and a score of 8 or 9 as high quality (26).

2.7. Data synthesis

Differences in alpha-diversity, beta-diversity, and relative abundance were qualitatively presented for patients with chronic pain, compared to controls. Additionally, random-effect meta-analyses were performed for alpha-diversity metrics (e.g. observed species, Chao1, abundance coverage estimator, Pielou, Shannon index, Simpson index, inverse Simpson index, and faith phylogenetic diversity) between chronic pain patients and controls in case ≥2 effect sizes were available for a specific metric. Standardized mean difference (SMD) was selected as metric for the meta-analyses, with the following interpretation: SMD ≤ 0.2 as trivial, < 0.2 < SMD < 0.5 as small, 0.5 ≤ SMD < 0.8 as moderate, and SMD ≥ 0.8 as large (23, 27). In case the necessary information could not be extracted adequately, the study authors were contacted to request it. When the median with the first and third quartile or interquartile range was provided, the mean and standard deviation were calculated manually, according to formulas provided by Wan et al. (2014) (28). In addition, if data were expressed only as a graph (rather than numerical data within the text), the software Engauge Digitizer 12.1 was used to extract numerical values. Heterogeneity was evaluated with I² statistic and publication bias with Egger’s test. All analyses were performed in R Studio version 2022.07.2. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

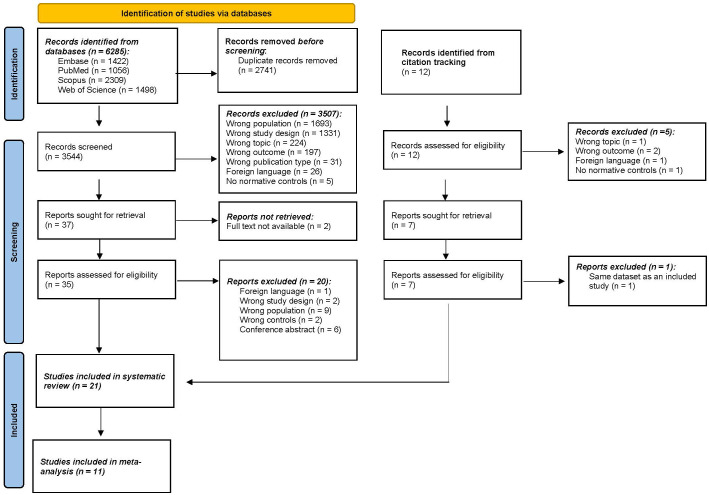

A total of 6285 articles were identified through the four selected databases ( Figure 1 ). After removing all duplicates, 3544 articles were selected for screening. After screening on title and abstract, 37 articles remained eligible for full screening. The percentage of agreement on title and abstract screening between both reviewers was 99.8% (7 conflicts). The reasons for exclusion were wrong population (n=1693), followed by wrong study design (n=1331), wrong topic (n=224), wrong outcome (n=197), and to a lesser extent wrong publication type, foreign language, and no controls. Afterward, 2 articles were excluded because there was no full text available. Citation screening identified 12 additional articles of which 7 were deemed suitable for full text screening. After full-text screening (N=42), 21 articles were included in this systematic review. The percentage of agreement on full text screening between both reviewers was 83.78%.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart. n, number.

3.2. Study characteristics

Characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 2 . Nine studies (42.8%) were conducted in the USA, four (19%) in Asian countries, four (19%) in European countries, one (4.8%) in Canada, one (4.8%) in Australia, one (4.8%) in Ukraine, and one in the USA, UK, and Australia (4.8%). In terms of chronic pain populations, 19 studies explored chronic primary pain syndromes (pain is conceived as a disease), while 2 evaluated chronic secondary pain syndromes (pain manifests as a symptom of another disease). Specifically, 9 (42.8%) studies evaluated myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), 4 (19%) studies included patients with migraine, and 3 (14.3%) studies evaluated patients with fibromyalgia. The following conditions were explored in only one study: axial spondyloarthritis (4.8%), interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (4.8%), Gulf War Illness (4.8%), complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) (4.8%), and chronic stable angina (4.8%). In total, data from 962 chronic pain patients and data from 1212 controls without chronic pain were included. Patients and controls were matched in 9 studies on the following variables: age (9 studies), sex (7 studies), BMI (5 studies), geographical site/environment (3 studies), race/ethnicity (2 studies), date of sampling (1 study), season of sampling (1 study), and general activity patterns (1 study). The NOS of the included studies ranged from 2-9, with 10 studies classified as low quality, 4 as moderate quality, and 7 as high quality ( Supplementary Table 1 ).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author | Country | Population | Sample size (with stool samples) | Age | Mean BMI | % Female | % Patients on medication | Matching variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bai et al., 2022 (29) | USA, UK, and Australia | Migraine (physician diagnosis) | P: 35 C: 341 |

11.5 ± 3.8 | 62.9% normal BMI; 21.0% underweight; 16.1% overweight/obese | 33.3% | NA | |

| Berlinberg et al., 2021 (30) | USA | Axial spondyloarthritis who met the 2009 Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society criteria | P: 21 C: 24 |

P: 44.92 ± 12.1 C: 45.16 ± 11.8 |

P: 43.5% C: 50.0% |

No antibiotics last 2 weeks, no aspirin or NSAIDs last 7 days, no anticoagulation. | NA | |

| Braundmeier-Fleming et al., 2016 (31) | USA | Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome | P: 18 C: 16 |

P: 35 ± 9 C: 35 ± 11 |

P: 100% C: 100% |

No antibiotics in previous 3 months | NA | |

| Chen et al., 2019 (32) | China | Migraine | P: 54 C: 54 |

P: 61.0 ± 8.4 C: 62.5 ± 9.6 |

P: 26.2 ± 4.6 C: 25.4 ± 3.35 |

P: 100% C: 100% |

Age and BMI | |

| Clos-Garcia et al., 2019 (33) | Spain | FM who met the 2016 diagnostic criteria | P: 105 C: 54 |

P: 52.52 ± 10.3 C: 53.5 ± 12.4 |

P: 69.52% C: 48.15% |

P: 70% painkillers; 55% antidepressants/benzodiazepines; 30% antiepiliptic drugs | Age and same environment | |

| Frémont et al., 2013 (34) | Belgium and Norway | ME/CFS who met Fukuda criteria | P Belgium: 18 P Norway: 25 C Belgium: 19 C Norway: 17 |

P Belgium: 38.5 (13) P Norway: 41 (12.5) C Belgium: 41 (12.6) C Norway: 45 (19) |

P Belgium: 83.3% P Norway: 88% C Belgium: 78.95% C Norway: 82.3% |

No use of antibiotics or probiotics for four weeks prior to sample collection. | NA | |

| Giloteaux et al., 2016 (35) | USA | ME/CFS who met Fukuda criteria | P: 49 C: 39 |

P: 50.2 (12.6) C: 45.5 (9.9) |

P: 25.5 (4.9) C: 27.1 (6.1) |

P: 77.5% C: 76.9% |

NA | |

| Guo et al., 2023 (36) | USA | ME/CFS cases who met 1994 CDC and 2003 Canadian consensus criteria | P: 106 C: 91 |

P: 47.8 ± 13.7 C: 47.0 ± 14.1 |

P: 26.1 ± 5.2 C: 25.2 ± 4.7 |

P: 70.8% C: 75.8% |

P: 22.6% painkillers, 12.3% antibiotics and 38.7% antidepressants C: 2.2% painkillers, 5.5% antibiotics and 13.2% antidepressants |

geographical/clinical site, sex, age, race/ethnicity, and date of sampling ( ± 30 days) |

| Janulewicz et al., 2019 (37) | USA | Gulf War Illness fulfilling Kansas GWI case criteria | P: 3 C: 5 |

P: 63.2 ± 15.5 C: 52.8 ± 6.7 |

P: 31.9 ± 0.7 C: 28.6 ± 2.5 |

P: 33.3% C: 0% |

NA | |

| Kitami et al., 2020 (38) | Japan | ME/CFS who met Fukuda criteria in 1994, International Consensus Criteria, and Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease criteria | P: 48 (28 microbiome data) C: 52 (39 microbiome data) |

P: 37 (33-42) C: 40 (34-45) |

P: 21 (19-23) C: 20 (19.8-22) |

P: 85.4% C: 90.4% |

Age, gender, and BMI | |

| Kopchak et al., 2022 (39) | Ukraine | Chronic and Episodic forms of migraine | P+C: 100 | P+C: 38.6 ± 8 | P+C: 85.3% | NA | ||

| Lupo et al., 2021 (40) | Italy | ME/CFS who met Fukuda criteria | P: 35 C: 35 |

P: 46.4 (16.1) C: 55.2 (18) |

P: 23.1 (4.4) C: 23.5 (4.7) |

P: 74.3% C: 74.3% |

No use of antibiotics, cortisone and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, inhibitors of proton pump inhibitors and probiotic drugs in the two months before the study. | Age, sex and BMI |

| Mandarano et al., 2018 (41) | USA | ME/CFS who met Fukuda criteria in 1994 | P: 17 (11 for alpha and beta diversity) C: 17 (10 for alpha and beta diversity) |

P: 52 (11.9) C: 44.6 (10.9) |

P: 26.8 (4.7) C: 27.4 (4.5) |

P: 76.47% C: 94.12% |

NA | |

| Minerbi et al., 2019 (42) | Canada | FM who met the 2016 diagnostic criteria | P: 77 C: 79 |

P: 46 ± 8 | P: 100% | No antibiotics in previous 2 months | NA, however, controls include first-degree relatives, household members, and unrelated women. | |

| Nagy-Szakal et al., 2017 (43) | USA | ME/CFS who met the 1994 CDC Fukuda and the 2003 Canadian consensus criteria | P: 50 C: 50 |

P: 51.081 SEM± 1.607 C: 51.320 SEM± 1.620 |

P: 56% BMI < 25kg/m² and 44% <25 kg/m² C: 44% BMI < 25kg/m² and 56% <25 kg/m² |

P: 82% C: 82% |

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, geographic/clinical site and season of sampling | |

| Reichenberger et all., 2013 (44) | USA | CRPS who met IEASP criteria (87.5% Type 1) | P: 11 (no GI symptoms) C: 16 |

P: 40.45 C: 35.63 |

P: 25.70 ± 1.65 C: 23.68 ± 0.70 |

P: 100% C: 100% |

No antibiotics or narcotics previous 3 months. P: 63% Antiepileptics; 57% antidepressants; 31% antianxiolytics. | NA |

| Sheedy et al., 2009 (45) | Australia | CFS who met Holmes, Fukuda and Canadian Definition Criteria | P: 108 C: 177 |

NA | ||||

| Shukla et al., 2015 (46) | USA | ME/CFS who met Fukuda criteria in 1994 | P: 10 C: 10 |

P: 48.6 ± 10.5 C: 46.5 ± 13.0 |

P: 23.9 ± 4.3 C: 24.6 ± 3.3 |

P: 80% C: 80% |

No opioids or immunomodulatory medications, antibiotics, probiotics. | Age, gender, BMI, and self-reported general activity patterns |

| Weber et al., 2022 (47) | Austria | FM who met the 2016 American College of Rheumatology criteria | P: 25 C: 26 |

P: 49.8 ± 8.6 C: 50.0 ± 8.0 |

P: 25.6 ± 5.6 C: 23.8 ± 4.0 |

P: 88% C: 81% |

P: 68% NSAID, 36% antidepressants, 20% antihypertensive drugs; 24% proton pump inhibitors; 12% antibiotics; 40% tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol C: 31% NSAID, 8% antidepressants, 8% antihypertensive drugs; 8% proton pump inhibitors |

Age and sex |

| Yong et al., 2023 (48) | Korea | Episodic migraine (P1) and Chronic migraine (P2) who fulfilled ICHD-3 criteria of EM (code 1.1 or 1.2) or CM (code 1.3) |

P1: 42 P2: 45 C: 43 |

P1: 39.6 ± 11.4 P2: 40.8 ± 12.5 C: 43.2 ± 11.7 |

P1: 22.8 ± 2.5 P2: 22.7 ± 3.5 C: 22.1 ± 3.6 |

P1: 78.6% P2: 91.1% C: 81.4% |

P1: 47.6% anti-epileptic medication, 26.2% beta blockers, 4.8% anti-depressant, 2.4% calcium-channel blocker. P2: 51.1% anti-epileptic, 17.8% beta blockers, 2.2% anti-depressant. |

Age, sex, BMI |

| Zhao et al., 2021 (49) | China | Chronic stable angina who met American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association criteria | P: 30 C: 10 |

P: 62 (Q1-Q3: 41-80) C: 60 (Q1-Q3: 40-76) |

P: 22.5 (Q1-Q3: 18.4-24.1) C: 22.3 (Q1-Q3: 20.8-23.5) |

P: 43.33% C: 50% |

P: 100% beta-blockers; 100% long-lasting nitrates; 3.3% ACE inhibitors; 20% calcium channel blockers; 6.7% angiotensin receptor blockers | NA |

BMI, body mass index; C: controls; ME/CFS, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome; NA, not applicable; P, patients.

3.3. Microbiome characteristics

After collection of samples, 14 studies (66.7%) froze the samples at -80°C until further use, 1 study (4.8%) at -70°C, 2 studies (9.5%) at -20°C, and it was not reported for 4 studies (19%). In terms of stool processing, a broad variety was observed ( Supplementary Table 2 ). Only one study explored eukaryotes (41). In terms of sequencing, 14 studies conducted 16S sequencing, 3 studies shotgun metagenomics, 1 study paired-end metagenomic sequencing, 1 study 18S sequencing, and 2 studies did not report the sequencing. The 18S sequencing was performed at region V9, while the 16S sequencing was performed at regions V1-V2 (1 study), V2 (1 study), V3-V4 (4 studies), V3-V5 (1 study), V4 (4 studies), and V5-V6 (2 studies).

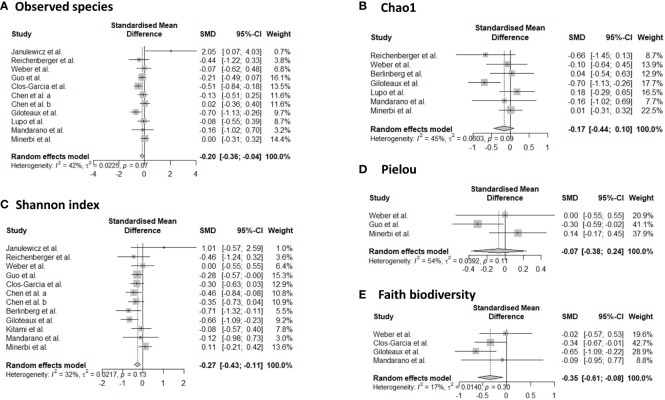

3.3.1. Alpha-diversity

Sixteen studies provided data for alpha-diversity, evaluated through 8 different metrics. When evaluating richness through observed species, non-significant differences were revealed for patients with axial spondyloarthritis (30), ME/CFS (36, 40, 41), migraine (32), and fibromyalgia (33, 47) compared to controls. For patients with ME/CFS, only one study found significant differences with higher richness in controls compared to patients (35). Significantly increased values for observed species were found for patients with Gulf War Illness (37), while significantly decreased values for patients with CRPS (44) in relation to controls. Based on pooled estimates, a significant SMD of -0.201 (95% CI from -0.04 to -0.36, p=0.01, I²=41.9%, 11 effect sizes) was revealed, classified as a small effect size, pointing towards lower observed species numbers in chronic pain patients compared to controls ( Figure 2 ). Egger’s test did not reveal indications for funnel plot asymmetry (t=0.9, df=9, p=0.39). For Chao1, significantly reduced values were obtained in patients with CRPS (44) and in one study with ME/CFS patients (35), while the other studies did not reveal significant differences between chronic pain patients and controls (30, 33, 40, 41, 47, 48). Non-significant results were revealed for the abundance coverage estimator (33, 47), as confirmed with a meta-analysis (SMD of -0.17 (95% CI from -0.44 to 0.10), p=0.22). For evenness, the Pielou metric resulted in significantly lower values in patients with ME/CFS compared to controls (36), while other reports did not reveal significant differences (29, 47). For richness/evenness, 15 studies explored the Shannon index with significant differences in favor of chronic pain patients (37), in favor of controls (29, 32, 35, 36, 44), and no significant difference between controls and chronic pain patients (30, 33, 34, 38, 41, 42, 47, 48). A random-effect meta-analysis resulted in a significantly decreased index in chronic pain patients compared to controls (p<0.001) with a small effect size (SMD -0.27, 95% CI from -0.11 to -0.43, 12 effect sizes, Egger’s Test t=0.25, df=10, p=0.81). Non-significant results were revealed for the Simpson index between chronic pain patients and controls (30, 33, 38, 40, 48), as was the case for the inverse Simpson index (42, 47). Faith phylogenetic diversity indicated increased values in controls in three studies (29, 33, 35), while two other studies revealed no significant differences (41, 47) between chronic pain patients and controls. A random-effect meta-analysis resulted in a significantly decreased index in chronic pain patients compared to controls (p=0.01) with a small effect size (SMD -0.35, 95% CI from -0.08 to -0.61, 4 effect sizes, Egger’s Test t=0.71, df=2, p=0.55). The meta-analysis for Chao1 and Pielou did not reveal significant differences between controls and chronic pain patients. The study of Zhao et al. (49) provided mean values for observed species, Chao1, abundance coverage, Shannon index, and Simpson index for patients with chronic stable angina compared to controls, however, it was not clear whether the results were significant. Therefore, these results were not qualitatively discussed, however, they are incorporated into the meta-analyses.

Figure 2.

Forest plots of α-diversity metrics observed species (A), Chao1 (B), Shannon index (C), Pielou (D), and faith phylogenetic diversity (E). Standardized mean differences were used as effect sizes whereby a negative point estimate denotes a higher value in controls and a positive estimate a higher value in chronic pain patients.

3.3.2. Beta-diversity

Ten studies explored beta-diversity with the aid of three different metrics (Bray-Curtis, Weighted UniFrac, and Unweighted UniFrac) (29, 30, 35, 36, 41–44, 48, 49). In patients with migraine, inconsistent results were revealed with significant differences in beta-diversity according to Bai et al. (Bray-Curtis and Weighted UniFrac) (29) and non-significant results by Yong et al. (Bray-Curtis, Weighted UniFrac, and Unweighted UniFrac) (48). In patients with ME/CFS, two studies pointed towards significant differences in β-diversity, measured with Bray-Curtis, compared to healthy participants (36, 43), and two other studies did not reveal differences (35, 41). For patients with fibromyalgia (42), CRPS (44), and chronic stable angina (49), significant differences in beta-diversity were revealed, by one study for each condition. A non-significant result was revealed for patients with axial spondyloarthritis (30).

3.3.3. Differentially abundant microbes

Twenty out of twenty-one studies explored the relative abundance of gut microbes in chronic pain patients compared to controls ( Table 3 ). Differences were found in 8 phyla, 14 families, 52 genera, and 73 species. An overview of the differences between the populations can be found in Table 4 . At the phylum level, four main taxa were explored namely Actinobacteria (29, 33, 46), Bacteroidetes (29, 33, 40, 46), Firmicutes (29, 32, 33, 35, 40, 44, 46, 49), and Proteobacteria (29, 35, 44, 49). For Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes both increases and decreases were revealed in chronic pain patients compared to controls, pointing towards inconsistent results. For Proteobacteria, a decrease was revealed in chronic pain patients compared to controls in all four studies (29, 35, 44, 49). Four fungal phyla were explored as well, with an increase in abundance in controls in Ascomycotae and decreased abundances in Basidiomycotae, Stramenopiles, and Zygomycota (41). At the family level, Lachnospiraceae were most often explored whereby 5 out of 6 studies indicated a decrease in relative abundance in chronic pain patients, compared to controls (29, 33, 37, 40, 43). At the genus level, Faecalibacterium spp. were most often explored, followed by Dorea spp., Eggerthella spp., and Roseburia spp. A decrease was found in Faecalibacterium spp. in patients with migraine (32, 48), ME/CFS (35, 38, 43) and chronic angina (49). For Dorea spp., inconsistent results were revealed for migraine patients (29, 48), an increase in patients with FM (33), and a decrease in patients with ME/CFS compared to controls (43). For Roseburia spp., 3 out of 4 studies revealed an increased relative abundance in controls (34, 43, 48), while one study revealed an increase in patients with fibromyalgia (33). In the genus Eggerthella, an increased relative abundance was found in patients with migraine (29, 48) and ME/CFS (35, 38). At the species level, a decrease in the relative abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was revealed for patients with migraine (32), ME/CFS (36, 43), fibromyalgia (42), and bladder pain syndrome (31). Odoribacter splanchnicus had a lower abundance in patients with migraine (32), ME/CFS (43), and bladder pain syndrome (31). Clostridium asparagiforme and Clostridium symbiosum increased in patients with migraine and ME/CFS, while Coprococcus catus and Ruminococcus obeum decreased in these patients (32, 43). Flavonifractor plautii had an increased abundance in patients with migraine and fibromyalgia (32, 42). Finally, Eggerthella lenta also increased in patients with migraine (32, 39).

Table 3.

Composition analysis of the included studies.

| Author | OTU | Chao1 | Abundance coverage |

Evenness | Shannon | Simpson | Inverse Simpson |

Faith | Beta Diversity |

Relative abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bai et al., 2022 (29) | NS | C higher than P | C higher than P | Bray-Curtis: S Weighted UniFrac: S |

Phylum level: Higher Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Probacteria in P. Firmicutes also higher in C. Family level: Higher unidentified family Lachnospiraceae, unidentified family Erysipelotrichaceae in P than C. Higher unidentified family Christensenellaceae, unidentified family Lachnospiraceae, and unidentified family Ruminococcaceae in C. Genus level: Higher Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, and Odoribacter, Eggerthella and Varibaculum, SMB53, Lachnospira, Dorea, Veillonella, Anaerotruncus, Butyricicoccus, Eubacterium, Coprobacillus, Sutterella in P than C. Higher Anaerostipes and Oribacterium in C. |

|||||

| Berlinberg et al., 2021 (30) | NS | NS | NS | NS | Bray-Curtis: NS | Species level: Higher Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Porphyromonas bennonis in P. Higher Streptococcus anginosus and Bacteroides dorei in C. |

||||

| Braundmeier-Fleming et al., 2016 (31) | Species level: lower E. sinensis, C. aerofaciens, F. prausnitzii, O. splanchnicus, and L. longoviformis in P. | |||||||||

| Chen et al., 2019 (32) | NS at genus and species level | Decreased in P compared to C | Phylum level: higher Firmicutes in P. Genus level: lower Faecalibacterium in P. Species level: higher Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bifidobacteriumadolescentis, and Methanobrevibacter smithii in C. Higher Blautia hydrogenotrophica, Clostridium asparagiforme, Clostridium clostridioforme, Clostridium bolteae, Clostridium citroniae, Clostridium hathewayi, Clostridium ramosum, Clostridium spiroforme, Clostridium symbiosum, Eggerthella lenta, Flavonifractor plautii, Lachnospiraceae bacterium, and Ruminococcus gnavus in P. Higher Bacteroides clarus, Bacteroides intestinalis, Bacteroides salyersiae, Bacteroides stercoris, Butyrivibrio crossotus, Clostridium sp. L2_50, Coprococcus catus, Eubacterium hallii, Eubacterium ramulus, Odoribacter splanchnicus, Peptostreptococcaceae noname unclassified, Prevotella copri, Ruminococcus callidus, Ruminococcus champanellensis, Ruminococcus obeum, and Sutterella wadsworthensis in C. |

|||||||

| Clos-Garcia et al., 2019 (33) | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | P lower than C | Phylum level: Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes both increased and decreased, Actinobacteria reduced in P. Family level: Higher Rikenellaceae in P. Lower unassigned genus in Bacteroidaceae and Lachnospiraceae families, Bifidobacteriaceae and Erysipelotichaceae in P. Genus level: Lower Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Eubacterium and Clostridium in P. Higher Dorea, Roseburia and Alistipes in P. |

|||

| Frémont et al., 2013 (34) | NS | Genus level: Higher Lactonifactor and Alistipes in Norwegian P. Higher Roseburia, Syntrophococcus, Holdemania and Dialister in Norwegian C. Higher Lactonifactor in Belgian P. Higher Asaccharobacter in Belgian C. | ||||||||

| Giloteaux et al., 2016 (35) | C: 1486.5 (456.5) P: 1204.3 (351.2) S |

C: 2918.4 (884.9) P: 2363.5 (705) S |

C: 5.9 (0.9) P: 5.3 (0.9) S |

C: 73.4 (19.0) P: 61.7 (16.7) S |

Weighted UniFrac: NS Unweighted UniFrac: NS |

Phylum level: lower Firmicutes in P. Higher Proteobacteria in P. Family level: higher Enterobacteriaceae, Prevotellaceae in P. Lower Ruminococcaceae, Bacteroidaceae, Rickenellaceae, Bifidobacteriaceae in P. Genus level: Higher Oscillospira, Lactococcus, Anaerotruncus, Coprobacillus and Eggerthella in P. Higher Faecalibacterium and Bifidobacterium in C. |

||||

| Guo et al., 2023 (36) | NS | P lower then C | P lower then C | Bray-Curtis: S | Species level: Lower F. prausnitzii, E. rectale, and C. secundus in P. Higher R. lactatiformans, C. bolteae, R. gnavus, E. ramosum, C. scindens, Blauti sp. N6H1.15, S. intestinalis, T. nexilis, and Lachnoclostridium sp. YL32 in P. |

|||||

| Janulewicz et al., 2019 (37) | P: 576 (SD: 12.9) C: 415 (SD: 83.1) S |

P: 4.03 (SD: 0.15) C: 3.79 (SD: 0.23) S (family level) |

Phylum level: NS Family level: higher Lachnispiracae in C compared to P. Genus level: Higher Dialister in C than P. Ruminococcus higher in P than C. |

|||||||

| Kitami et al., 2020 (38) | NS | NS | Genus level: Higher Blautia, Coprobacillus, Eggerthella in P. Higher Collinsella, Faecalibacterium and Lachnospira in C. | |||||||

| Kopchak et al., 2022 (39) | Species level: higher frequency of Alceligenes spp, Clostridium coccoides, Clostridium propionicum, Eggerthella lenta, Pseudonocardia spp, Rhodococcus spp, Micromycetes spp (campesterol and sitosterol), Herpes simplex for P than C. | |||||||||

| Lupo et al., 2021 (40) | P: 215.6 (78) C: 221.4 (60.8) NS |

P: 453.4 (194.7) C: 422 (151.2) NS |

P: 17.7 (11.1) C: 13.3 (7.3) NS |

Phylum level: Higher Bacteroidetes in P. Higher Firmicutes in C. Class level: Higher Bacteroidia in P. Higher Clostridia in C. Order level: Higher Clostridiales in C. Higher Bacteroidales in P. Family level: Lower Lachnospiraceae in P. Higher Bacteroidaceae, Barnesiellaceae in P. Genus level: Lower Anaerostipes in P. Higher Bacteroides and Phascolarctobacterium in P. Species level: Higher Bacteroides ovatus and Bacteroides uniformis in P. |

||||||

| Mandarano et al., 2018 (41) | C: 18.1 (SE: 6.9) P: 14.1 (SE: 7.8) NS |

C: 26.6 (SE: 10.7) P: 20.6 (SE: 10.9) NS |

C: 2.8 (SE: 1.2) P: 2.3 (SE: 1.2) NS |

C: 6.7 (SE:2.1) P: 6.0 (SE:2.4) NS |

Weighted UniFrac: NS Unweighted UniFrac: NS |

Phylum level fungi: lower Ascomycota in P. Higher Basidiomycota, Stramenopiles and Zygomycota in P. Class level: higher Agaricomycetes, Tremellomycetes in P. Order level: lower Saccharomycetales in P. Higher Agaricales, Boletales, Polyporales, Tremellomycetes unknown, Malasseziales, Entomophthorales, Mucorales, Pleurosigma, Eustigmatales, Peronosporales, Cystofilobasidiales in P. Tremellales, Sporidiobolales and Ustilaginales only observed in C. Species level: Higher Blastocystis in P. |

||||

| Minerbi et al., 2019 (42) | NS | NS | Bray-Curtis: S | Species level: Lower F. prausnitzii and B. uniformis in P. Higher Intestinimonas butyricipro ducens, Flavonifractor plautii, Butyricoccus desmolans, Eisenber giella tayi, and Eisenbergiella massiliensis in P. | ||||||

| Nagy-Szakal et al., 2017 (43) | Bray-Curtis: C lower than P. | Family level: lower Lachnospiraceae and Porphyromonadaceae in P, while higher Clostridiaceae. Genus level: lower Dorea, Faecalibacterium, Coprococcus, Roseburia, and Odoribacter in P, while higher Clostridium and Coprobacillus. Species level: lower Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Faecalibacterium cf., Roseburia inulinivorans, Dorea longicatena, Dorea formicigenerans, Coprococcus catus, Odoribacter splanchnicus, Ruminococcus obeum, and Parabacteroides merdae in P, while higher Clostridium asparagiforme, Clostridium symbiosum, and Coprobacillus bacterium in P. |

||||||||

| Reichenberger et all., 2013 (44) | P: mean 280.45 (195-392 range) C: mean 328.63 (145-591 range) S |

P: 520.76 (SE: 44.18) C: 651.75 (SE: 54.12) S |

P: 3.89 (SE: 0.15) C: 4.12 (SE: 0.12) S |

Unweighted UniFrac matrix: S (since clustering is successful based on disease state) | Phylum level: Firmicutes 64.8% in C and 44% in P, Proteobacteria 0.078% in C and 5.1% in P. | |||||

| Sheedy et al., 2009 (45) | Species level: Higher E. Coli in C. Higher E. faecalis, S. sanguinis in P. | |||||||||

| Shukla et al., 2015 (46) | Phylum level: Higher Bacteroidetes (P 27.71% vs C 22.43%), lower Firmicutes (P 58.40% vs 65.29%) and lower Actinobacteria (P 0.58% vs C 1.06%) in P. | |||||||||

| Weber et al., 2022 (47) | P: 194.85 (SD: 42.98) C: 197.99 (SD: 49.69) NS |

P: 183.37 (50.84) C: 187.96 (44.04) NS |

P: 212.46 (139.9) C: 185.53 (41.58) NS |

P: 0.73 (0.05) C: 0.73 (0.05) NS |

P: 5.58 (0.56) C: 5.58 (0.56) NS |

P: 0.15 (0.04) C: 0.14 (0.05) NS |

P: 16.07 (SD:2.71) C: 16.13 (2.98) NS |

|||

| Yong et al., 2023 (48) | NS | NS | NS | Weighted UniFrac: NS Unweighted UniFrac: NS Bray-Crutis: NS |

Phylum level: no difference. Class level: Higher Tissierellia in P1 and P2 than C. Order level: Higher Tissierellales in P1 and P2 than C. Family level: Higher Peptoniphilaceae and Eubacteriaceae in P1 than C. Higher Peptoniphilaceae in P2 than C. Genus level: Higher Olsenella in P1 than C. Higher Hungatella, Clostridium_g6, Eggerthella and Longicatena in P2 than C. Higher Catenibacterium, PAC000195_g, Fusicantenibacter, Agathobacter, Eubacterium_g4, Roseburia, Lachnospiraceae_uc, Eubacterium_g21 in C than P1. Higher PAC001134_g, Catenibacterium, PAC000692_g, Holdemanella, PAC001137_g, PAC000195_g, Agathobacter, Eubacterium_g4, Roseburia, Frisingicoccus, Faecalibacterium, Dorea and Lachnospira in C than P2. |

|||||

| Zhao et al. (49) | P: 323.05 C: 321.9 |

P: 327.86 C: 327.51 |

P: 336.72 C: 335.62 |

P: 5.26 C: 5.84 |

P: 0.91 C: 0.96 |

Weighted UniFrac: S | Phylum level: lower Firmicutes in P, and higher Probacteria in P. Genus level: higher Anaerostipes, Erysipelatoclostridium, Holdemanella, Sarcina, Streptococcus, and Weissella in P. Lower Faecalibacterium, Romboutsia, and Subdoligranulum in P. |

C, controls; NA, not applicable; NS, non-significant; P, patients; S, significant.

Table 4.

Changes in relative abundance of microbes in chronic pain patients compared to controls at phylum, family, genus and species level.

| Migraine | ME/CFS | FM | Axial spondy-oarthritis | Bladder pain syndrome | Gulf-war | CRPS | Chronic angina | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum level | ||||||||

| Actinobacteria | Higher P (29) | Higher C (46) | Higher C (33) | |||||

| Bacteroidetes | Higher P (29) | Higher P (46) Higher P (40) |

Higher P (33) Higher C (33) |

|||||

| Firmicutes | Higher C (29) Higher P (29) Higher P (32) |

Higher C (46) Higher C (35) Higher C (40) |

Higher P (33) Higher C (33) |

Higher C (44) | Higher C (49) | |||

| Proteobacteria | Higher P (29) | Higher C (35) | Higher P (44) | Higher P (49) | ||||

| Ascomycota | Higher C (41) | |||||||

| Basidiomycota | Higher P (41) | |||||||

| Stramenopiles | Higher P (41) | |||||||

| Zygomycota | Higher P (41) | |||||||

| Family level | ||||||||

| Bacteroidaceae | Higher C (35) Higher P (40) |

Higher C (33) | ||||||

| Barnesiellaceae | Higher P (40) | |||||||

| Bifidobacteriaceae | Higher C (35) | Higher C (33) | ||||||

| Christensenellaceae | Higher C (29) | |||||||

| Clostridiaceae | Higher P (43) | |||||||

| Erysipelotrichaceae | Higher P (29) | Higher C (33) | ||||||

| Enterobacteriaceae | Higher P (35) | |||||||

| Eubacteriaceae | Higher P (48) | |||||||

| Lachnospiraceae | Higher P (29) Higher C (29) |

Higher C (43) Higher C (40) |

Higher C (33) | Higher C (37) | ||||

| Peptoniphilaceae | Higher P (48) | |||||||

| Porphyromonadaceae | Higher C (43) | |||||||

| Prevotellaceae | Higher P (35) | |||||||

| Rikenellaceae | Higher C (35) | Higher P (33) | ||||||

| Ruminococcaceae | Higher C (29) | Higher C (35) | ||||||

| Genus level | ||||||||

| Agathobacter | Higher C (48) | |||||||

| Alistipes | Higher P (34) | Higher P (33) | ||||||

| Anaerostipes | Higher C (29) | Higher C (40) | Higher P (49) | |||||

| Anaerotruncus | Higher P (29) | Higher P (35) | ||||||

| Asaccharobacter | Higher C (34) | |||||||

| Bacteroides | Higher P (29) | Higher P (40) | Higher C (33) | |||||

| Bifidobacterium | Higher C (35) | Higher C (33) | ||||||

| Blautia | Higher P (38) | |||||||

| Butyricicoccus | Higher P (29) | |||||||

| Catenibacterium | Higher C (48) | |||||||

| Clostridium | Higher P (48) | Higher P (43) | Higher C (33) | |||||

| Collinsella | Higher C (38) | |||||||

| Coprobacillus | Higher P (29) | Higher P (43) Higher P (38) |

||||||

| Coprococcus | Higher C (43) Higher P (35) |

|||||||

| Dialister | Higher C (34) | Higher C (37) | ||||||

| Dorea | Higher C (48) Higher P (29) |

Higher C (43) | Higher P (33) | |||||

| Eggerthella | Higher P (29) Higher P (48) |

Higher P (38) Higher P (35) |

||||||

| Erysipelatoclostridium | Higher P (49) | |||||||

| Eubacterium | Higher C (48) Higher P (29) |

Higher C (33) | ||||||

| Faecalibacterium | Higher C (48) Higher C (32) |

Higher C (43) Higher C (38) Higher C (35) |

Higher C (49) | |||||

| Frisingicoccus | Higher C (48) | |||||||

| Fusicantenibacter | Higher C (48) | |||||||

| Holdemanella | Higher C (48) | Higher P (49) | ||||||

| Holdemania | Higher C (34) | |||||||

| Hungatella | Higher P (48) | |||||||

| Lachnospira | Higher P (29) Higher C (48) |

Higher C (38) | ||||||

| Lachnospiraceae_uc | Higher C (48) | |||||||

| Lactococcus | Higher P (35) | |||||||

| Lactonifactor | Higher P (34) | |||||||

| Longicatena | Higher P (48) | |||||||

| Odoribacter | Higher P (29) | Higher C (43) | ||||||

| Olsenella | Higher P (48) | |||||||

| Oribacterium | Higher C (29) | |||||||

| Oscillospira | Higher P (35) | |||||||

| PAC000195_g | Higher C (48) | |||||||

| PAC000692_g | Higher C (48) | |||||||

| PAC001134_g | Higher C (48) | |||||||

| PAC001137_g | Higher C (48) | |||||||

| Parabacteroides | Higher P (29) | |||||||

| Phascolarctobacterium | Higher P (40) | |||||||

| Romboutsia | Higher C (49) | |||||||

| Roseburia | Higher C (48) | Higher C (43) Higher C (34) |

Higher P (33) | |||||

| Ruminococcus | Higher P (37) | |||||||

| Sarcina | Higher P (49) | |||||||

| SMB53 | Higher P (29) | |||||||

| Streptococcus | Higher P (49) | |||||||

| Subdoligranulum | Higher C (49) | |||||||

| Sutterella | Higher P (29) | |||||||

| Syntrophococcus | Higher C (34) | |||||||

| Varibaculum | Higher P (29) | |||||||

| Veillonella | Higher P (29) | |||||||

| Weissella | Higher P (49) | |||||||

| Species level | ||||||||

| Alceligenes spp | Higher P (39) | |||||||

| B. Uniformis | Higher C (42) | |||||||

| Bacteroides clarus | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| Bacteroides dorei | Higher C (30) | |||||||

| Bacteroides intestinalis | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| Bacteroides ovatus | Higher P (40) | |||||||

| Bacteroides salyersiae | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| Bacteroides stercoris | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| Bacteroides uniformis | Higher P (40) | |||||||

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis | Higher C (32) | Higher P (30) | ||||||

| Blastocystis | Higher P (41) | |||||||

| Blauti sp. N6H1.15 | Higher P (36) | |||||||

| Blautia hydrogenotrophica | Higher P (32) | |||||||

| Butyricoccus desmolans | Higher P (42) | |||||||

| Butyrivibrio crossotus | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| C. aerofaciens | Higher C (31) | |||||||

| C. bolteae | Higher P (36) | |||||||

| C. scindens | Higher P (36) | |||||||

| C. secundus | Higher C (36) | |||||||

| Clostridium asparagiforme | Higher P (32) | Higher P (43) | ||||||

| Clostridium bolteae | Higher P (32) | |||||||

| Clostridium citroniae | Higher P (32) | |||||||

| Clostridium clostridioforme | Higher P (32) | |||||||

| Clostridium coccoides | Higher P (39) | |||||||

| Clostridium hathewayi | Higher P (32) | |||||||

| Clostridium propionicum | Higher P (39) | |||||||

| Clostridium ramosum | Higher P (32) | |||||||

| Clostridium sp. L2_50 | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| Clostridium spiroforme | Higher P (32) | |||||||

| Clostridium symbiosum | Higher P (32) | Higher P (43) | ||||||

| Coprobacillus bacterium | Higher P (43) | |||||||

| Coprococcus catus | Higher C (32) | Higher C (43) | ||||||

| Dorea formicigenerans | Higher C (43) | |||||||

| Dorea longicatena | Higher C (43) | |||||||

| E. coli | Higher C (45) | |||||||

| E. faecalis | Higher P (45) | |||||||

| E. ramosum | Higher P (36) | |||||||

| E. rectale | Higher C (36) | |||||||

| E. sinensis | Higher C (31) | |||||||

| Eggerthella lenta | Higher P (32) Higher P (39) |

|||||||

| Eisenber giella tayi | Higher P (42) | |||||||

| Eisenbergiella massiliensis | Higher P (42) | |||||||

| Eubacterium hallii | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| Eubacterium ramulus | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| Faecalibacterium cf. | Higher C (43) | |||||||

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Higher C (32) | Higher C (36) Higher C (43) |

Higher C (42) | Higher C (31) | ||||

| Flavonifractor plautii | Higher P (32) | Higher P (42) | ||||||

| Herpes simplex | Higher P (39) | |||||||

| Intestinimonas butyricipro ducens | Higher P (42) | |||||||

| L. longoviformis | Higher C (31) | |||||||

| Lachnoclostridium sp. YL32 | Higher P (36) | |||||||

| Lachnospiraceae bacterium | Higher P (32) | |||||||

| Methanobrevibacter smithii | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| Micromycetes spp (campesterol and sitosterol) | Higher P (39) | |||||||

| Odoribacter splanchnicus | Higher C (32) | Higher C (43) | Higher C (31) | |||||

| Parabacteroides merdae | Higher C (43) | |||||||

| Peptostreptococcaceae | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| Porphyromonas bennonis | Higher P (30) | |||||||

| Prevotella copri | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| Pseudonocardia spp | Higher P (39) | |||||||

| R. gnavus | Higher P (36) | |||||||

| R. lactatiformans | Higher P (36) | |||||||

| Rhodococcus spp | Higher P (39) | |||||||

| Roseburia inulinivorans | Higher C (43) | |||||||

| Ruminococcus callidus | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| Ruminococcus champanellensis | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| Ruminococcus gnavus | Higher P (32) | |||||||

| Ruminococcus obeum | Higher C (32) | Higher C (43) | ||||||

| S. intestinalis | Higher P (36) | |||||||

| S. sanguinis | Higher P (45) | |||||||

| Streptococcus anginosus | Higher C (30) | |||||||

| Sutterella wadsworthensis | Higher C (32) | |||||||

| T. nexilis | Higher P (36) | |||||||

C, controls; P, patients.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated alterations in gut microbiota composition in chronic pain patients compared to controls. In terms of alpha-diversity, the richness metric observed species indicated a significantly decreased number of unique operational taxonomic units in chronic pain patients. Additionally, a lower Shannon index and faith phylogenetic diversity were revealed in patients compared to controls. For beta-diversity, inconclusive results were revealed. Finally, there was a decreased relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae in 83% of studies that evaluated this family in chronic pain patients compared to controls. A decreased abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Odoribacter splanchnicus species was demonstrated in patients compared to controls. Based on this systematic review, with complementary meta-analyses, there are indications for dysbiosis of gut microbiota in chronic pain patients.

The interest in gut microbiota as a potential underlying factor of disease maintenance has drastically increased during the last decade. Gut dysbiosis is expected to contribute to the etiology of, e.g., inflammatory bowel disease (50, 51), type 2 diabetes (52), colorectal cancer (53, 54), hypertension (55), and rheumatic diseases (23), besides its modulating role in chronic pain (56). The mechanisms by which acute infectious pain becomes chronic are very diverse and can include, among others, molecular mimicry (structural similarity between microbial and host molecules which could induce autoimmune responses), bystander activation, or microbe invasion (57, 58). Specific microbes such as Borrelia species and Mycobacterium leprae or viruses (e.g., HIV, SARS-Cov-2) are associated with a high incidence of chronic pain (57). A cross-disease meta-analysis was previously performed, whereby consistent patterns characterizing disease-associated microbiome changes were revealed (59). Some diseases were characterized by the presence of potentially pathogenic microbes, whereas others revealed a depletion of health-associated bacteria (59). About half of the genera associated with individual studies were bacteria that respond to more than one disease, supporting the hypothesis of non-disease-specific alterations but shared alterations (i.e. non-specific response) to health and disease (59). Based on this hypothesis, the current systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in patients with chronic pain, regardless of the underlying disease condition.

Gut microbiome alpha-diversity has been associated with human health, whereby reduced levels are indicative of acute and chronic diseases (60). Alpha-diversity metrics provide summary statistics that focus on summarizing the breadth of diversity present in an environment (61). The current study indicated a decrease in alpha-diversity in patients with chronic pain compared to controls, as reflected in several metrics namely, a decreased number of unique operational taxonomic units, a decreased Shannon index [which is a popular diversity index in the ecological field to reflect the richness of bacterial community (62)], and a decreased Faith’s phylogenetic diversity in chronic pain patients. Faith’s phylogenetic diversity accounts for the phylogenetic relatedness of community members and has been denoted as more sensitive to distinguishing disease factors relative to other alpha diversity metrics (63). Despite the small effect sizes, these alpha-diversity metrics all point towards a decreased richness in chronic pain patients, which may point out the need for nutritional interventions in patients with chronic pain. The gut microbiota produces polyamines, which in turn excites N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, a crucial factor of central nervous system sensitization (64), which is common in patients with chronic pain (65).

A reduction in the relative abundance of the Lachnospiraceae family was found in patients with chronic pain. All Lachnospiraceae members are anaerobic, fermentative and chemoorganotrophic, and are already present in early infancy (66). Aging is associated with increases in Lachnospiraceae abundance (67). The genera Blautia and Roseburia, belonging to the Lachnospiraceae family, are often associated with a healthy state (68). These genera are the main short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) producers [whereby SCFA activity modulates the surrounding microbial environment and interacts with the host immune system (69)] and are involved in the control of gut inflammatory processes, and maturation of the immune system (66, 70). A higher relative abundance of Roseburia ssp. was revealed in controls compared to chronic pain patients, highlighting the value of this genus in health states. Additionally, a decrease in the relative abundance of Odoribacter splanchnicus, another common SCFA-producing member of the human intestinal microbiota (71), was found in chronic pain patients. This finding was previously also described in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (72, 73).

Another finding was a decreased relative abundance of the Faecalibacterium genus, belonging to the family Ruminococcaceae, which comprises only one validated species, namely Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (74). A decrease in Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was observed in chronic pain patients, a species known to play a crucial role in host wellbeing and gut physiology (75). It is one of the main butyrate producers in the intestine (76), whereby butyrate is involved in maintaining mucosal integrity, alleviating inflammation (via macrophage function as well as a reduction in proinflammatory cytokines), and increasing anti-inflammatory mediators (77). Thus, this species is known for its anti-inflammatory properties (75). In murine models, it was revealed that Faecalibacterium prausnitzii cells could reduce the severity of both acute, chronic, and chemical-induced inflammation (78–80). Faecalibacterium prausnitzii depletion has been reported in adults with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and colorectal cancer (81–84), as well as in patients with rheumatic disorders (23, 85) and is proposed as a biomarker to discriminate between gut disorders and healthy subjects (75). This alteration may not be specific to inflammatory diseases and may be a more generic phenomenon of disease states since it is also revealed in chronic pain patients.

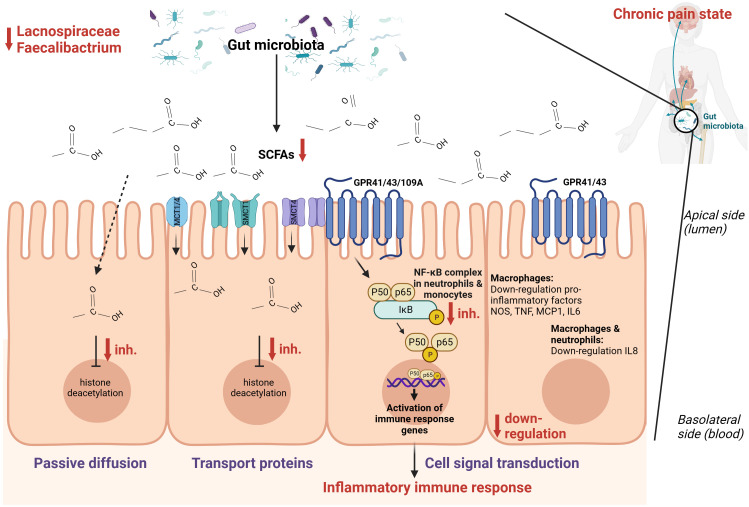

Combining these findings, it seems that SCFAs [mainly composed of acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid (86)] play an important role in the context of chronic pain ( Figure 3 ). There are two main mechanisms through which SCFAs can enter cells and consequently alter inflammation, namely cell signal transduction and passive diffusion combined with transport proteins. The latter functions through sodium-coupled monocarboxylate transport 1/2 (SMCT1/2), Na+ coupled transporters in the apical membrane of colonic epithelium, and monocarboxylate transporter 1/4 (MCT1/4), H+ coupled transporters mainly expressed in the apical and basolateral membrane of the colonic epithelium (89). Once SCFAs enter the cell through passive diffusion or transporters, they inhibit histone deacetylation (86). In dendritic cells and macrophages, inhibition of histone deacetylation is the main pathway to exert anti-inflammatory effects, while in neutrophils and monocytes, SCFAs inhibit tumor necrosis factor expression, the NF-κB signaling pathway, and histone deacetylase in addition to promoting interleukin-10 production as an anti-inflammatory cytokine. Cell signal transduction is realized by SCFAs through G protein-coupled cell membrane receptors GPR109A, GPR43, and GPR41 (90, 91). In macrophages, butyrate activates GPR41 to down-regulate pro-inflammatory factors among which are nitric oxide synthase, tumor necrosis factor, interleukin 6, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (92). In macrophages and neutrophils, SCFAs down-regulate interleukin 8 expression through activation of GPR43 and GPR41 (93). Finally, SCFAs can also regulate inflammation by activating anti-inflammatory signaling pathways by inhibiting histone deacetylase (86). Besides the role of SCFAs in inflammation, they also regulate the differentiation of T cells and B cells and regulate the function of innate immune cells among which are macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (86).

Figure 3.

Hypothesized schematic representation of the role of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in the regulation of gut and systemic immunity in relation to chronic pain (86–88). SCFAs can regulate inflammation through cell signal transduction by binding at G-protein coupled receptors GPR109A, GPR43, and GPR41 and down-regulate the NOS, TNF, MCP-1, IL-6, IL-8, and the NF-κB signaling pathway. Through passive diffusion and transport proteins (MCT1, MCT4, SMCT1, SMCT2), SCFAs can inhibit histone deacetylase. This is a simplified representation of the pathways involved in inflammation with the pathways expected to be relevant in the setting of chronic pain.

This study evaluated gut microbiome alterations in chronic pain patients compared to controls without chronic pain. Studies from different parts of the world were included among which were the USA, Europe, Asia, and Australia. There is no universal healthy gut microbiota (94, 95), since nationality and food preferences, among other factors, induce an influence on the gut microbiota. For example, the gut microbiome of a healthy European (including Slavic nationality) is characterized by the dominance of the phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia, while the gut microbiome of Asians is very diverse and rich in members of the genera Prevotella, Bacteroides Lactobacillus, Faecalibacterium, Ruminococcus, Subdoligranulum, Coprococcus, Collinsella, Megasphaera, Bifidobacterium, and Phascolarctobacterium (96). Therefore, this study only included studies that compared gut microbiota to a control group to limit the influence of local differences in gut microbiota composition.

The field of chronic pain and gut microbiota composition is still in its infancy, wherefore condition-specific alterations remain to be elucidated when more research is available, in case the hypothesis of shared alterations is not valid in pain settings. The majority of studies explored chronic primary pain syndromes, wherefore gut dysbiosis in chronic secondary pain syndromes still needs to be explored in more detail. When interpreting the results of this study, it should be taken into account that medication was previously denoted as an important covariate, and more specifically antibiotics, osmotic laxatives, inflammatory bowel disease medication, female hormones, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, and antihistamines (60). Recently, a multi-omics analysis elaborated on the concept of opioid-induced dysbiosis in gut microbiota (97), which further supports the hypothesis of addressing the gut-brain axis in patients with chronic pain, especially in those patients who take opioids as pain medication. Medication use was reported for every individual study, however, it was not possible to take a numerical output for medication use into account in the conducted meta-analysis. As revealed by this review, there is no common pipeline to conduct laboratory analyses, statistical evaluations, or quality assurance for gut microbiome data. Future steps should be conducted towards harmonization of processing gut microbiome data to ensure better comparability of the results.

5. Conclusions

This review pointed towards the potential value of dysbiosis in chronic pain patients, with non-specific disease alterations of microbes.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TD: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. JP: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MB: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MR: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. PR: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jonas Callens for serving as the second reviewer during the screening of titles and abstracts.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

LG is a postdoctoral research fellow funded by the Research Foundation Flanders FWO, Belgium project number 12ZF622N. JP received grant support from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott, NIH 2R01CA166379-06, NIH R01EB030324, NIH Blueprint 3U54EB015408 and NIH U44NS115111. She is part of the Board of Directors of Facial Pain Association, Board of Directors at Large of International Neuromodulation Society, President Elect of American Society of Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery and President of North American Neuromodulation Society. PR reports grants from Medtronic, Abbott and Boston Scientific and consultant fees and payments for lectures from Medtronic and Boston Scientific, outside the submitted work. MM has received speaker fees from Medtronic, Saluda and Nevro. STIMULUS received independent research grants from Medtronic.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1342833/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Ursell LK, Metcalf JL, Parfrey LW, Knight R. Defining the human microbiome. Nutr Rev (2012) 70 Suppl 1:S38–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00493.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Al Bander Z, Nitert MD, Mousa A, Naderpoor N. The gut microbiota and inflammation: an overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020) 17(20):7618. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhao Y, Zou DW. Gut microbiota and irritable bowel syndrome. J Dig Dis (2023) 24(5):312–20. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.13204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sharma P, Phatak SM, Warikoo P, Mathur A, Mahant S, Das K, et al. Crosstalk between Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal microbiota in various gastroduodenal diseases-A systematic review. 3 Biotech (2023) 13:303. doi: 10.1007/s13205-023-03734-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yadav H, Jaldhi, Bhardwaj R, Anamika, Bakshi A, Gupta S, et al. Unveiling the role of gut-brain axis in regulating neurodegenerative diseases: A comprehensive review. Life Sci (2023) 330:122022. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.122022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anand N, Gorantla VR, Chidambaram SB. The role of gut dysbiosis in the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders. Cells (2022) 12(1):54. doi: 10.3390/cells12010054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Montagnani M, Bottalico L, Potenza MA, Charitos IA, Topi S, Colella M, et al. The crosstalk between gut microbiota and nervous system: A bidirectional interaction between microorganisms and metabolome. Int J Mol Sci (2023) 24(12):10322. doi: 10.3390/ijms241210322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carabotti M, Scirocco A, Maselli MA, Severi C. The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann Gastroenterol (2015) 28:203–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farzi A, Fröhlich EE, Holzer P. Gut microbiota and the neuroendocrine system. Neurotherapeutics (2018) 15:5–22. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0600-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu B, Liu J, Wang M, Zhang Y, Li L. From serotonin to neuroplasticity: evolvement of theories for major depressive disorder. Front Cell Neurosci (2017) 11:305. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Punder K, Pruimboom L. Stress induces endotoxemia and low-grade inflammation by increasing barrier permeability. Front Immunol (2015) 6:223. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kelly JR, Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G, Hyland NP. Breaking down the barriers: the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability and stress-related psychiatric disorders. Front Cell Neurosci (2015) 9:392. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Han Y, Wang B, Gao H, He C, Hua R, Liang C, et al. Vagus nerve and underlying impact on the gut microbiota-brain axis in behavior and neurodegenerative diseases. J Inflammation Res (2022) 15:6213–30. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S384949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Silva YP, Bernardi A, Frozza RL. The role of short-chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in gut-brain communication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2020) 11:25. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Masse KE, Lu VB. Short-chain fatty acids, secondary bile acids and indoles: gut microbial metabolites with effects on enteroendocrine cell function and their potential as therapies for metabolic disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2023) 14:1169624. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1169624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G. Kynurenine pathway metabolism and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Neuropharmacology (2017) 112:399–412. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu Y, Yang W, Li Y, Cong Y. Enteroendocrine cells: sensing gut microbiota and regulating inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis (2020) 26:11–20. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Forte G, Troisi G, Pazzaglia M, Pascalis V, Casagrande M. Heart rate variability and pain: A systematic review. Brain Sci (2022) 12(2):153. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12020153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nees F, Löffler M, Usai K, Flor H. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis feedback sensitivity in different states of back pain. Psychoneuroendocrinology (2019) 101:60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ (2009) 339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O'Sullivan D, Wilk S, Michalowski W, Farion K. Using PICO to align medical evidence with MDs decision making models. Stud Health Technol Inform (2013) 192:1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain (2015) 156:1003–7. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Y, Wei J, Zhang W, Doherty M, Zhang Y, Xie H, et al. Gut dysbiosis in rheumatic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 92 observational studies. EBioMedicine (2022) 80:104055. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JP. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol (2007) 36:666–76. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wells G, Shea B, O'connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. Quality assessment scales for observational studies. Ottawa Health Res Institute (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bechard LJ, Rothpletz-Puglia P, Touger-Decker R, Duggan C, Mehta NM. Influence of obesity on clinical outcomes in hospitalized children: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr (2013) 167:476–82. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nikolova VL, Smith MRB, Hall LJ, Cleare AJ, Stone JM, Young AH. Perturbations in gut microbiota composition in psychiatric disorders: A review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry (2021) 78:1343–54. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol (2014) 14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bai J, Shen N, Liu Y. Associations between the gut microbiome and migraines in children aged 7-18 years: an analysis of the american gut project cohort. Pain Manage Nurs (2023) 24:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2022.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berlinberg AJ, Regner EH, Stahly A, Brar A, Reisz JA, Gerich ME, et al. Multi 'Omics analysis of intestinal tissue in ankylosing spondylitis identifies alterations in the tryptophan metabolism pathway. Front Immunol (2021) 12:587119. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.587119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Braundmeier-Fleming A, Russell NT, Yang W, Nas MY, Yaggie RE, Berry M, et al. Stool-based biomarkers of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Sci Rep (2016) 6:26083. doi: 10.1038/srep26083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen J, Wang Q, Wang A, Lin Z. Structural and functional characterization of the gut microbiota in elderly women with migraine. Front Cell Infect Microbiol (2019) 9:470. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clos-Garcia M, Andrés-Marin N, Fernández-Eulate G, Abecia L, Lavín JL, van Liempd S, et al. Gut microbiome and serum metabolome analyses identify molecular biomarkers and altered glutamate metabolism in fibromyalgia. EBioMedicine (2019) 46:499–511. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.07.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frémont M, Coomans D, Massart S, De Meirleir K. High-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing reveals alterations of intestinal microbiota in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Anaerobe (2013) 22:50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Giloteaux L, Goodrich JK, Walters WA, Levine SM, Ley RE, Hanson MR. Reduced diversity and altered composition of the gut microbiome in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome (2016) 4:30. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0171-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guo C, Che X, Briese T, Ranjan A, Allicock O, Yates RA, et al. Deficient butyrate-producing capacity in the gut microbiome is associated with bacterial network disturbances and fatigue symptoms in ME/CFS. Cell Host Microbe (2023) 31:288–304.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2023.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Janulewicz PA, Seth RK, Carlson JM, Ajama J, Quinn E, Heeren T, et al. The gut-microbiome in gulf war veterans: A preliminary report. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2019) 16(19):3751. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kitami T, Fukuda S, Kato T, Yamaguti K, Nakatomi Y, Yamano E, et al. Deep phenotyping of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome in Japanese population. Sci Rep (2020) 10:19933. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77105-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kopchak OO, Hrytsenko OY, Pulyk OR. Peculiarities of the gut microbiota in patients with migraine comparing to healthy individuals. Wiad Lek (2022) 75:2218–21. doi: 10.36740/WLek202209207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lupo GFD, Rocchetti G, Lucini L, Lorusso L, Manara E, Bertelli M, et al. Potential role of microbiome in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelits (CFS/ME). Sci Rep (2021) 11:7043. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86425-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mandarano AH, Giloteaux L, Keller BA, Levine SM, Hanson MR. Eukaryotes in the gut microbiota in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. PeerJ (2018) 6:e4282. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Minerbi A, Gonzalez E, Brereton NJB, Anjarkouchian A, Dewar K, Fitzcharles MA, et al. Altered microbiome composition in individuals with fibromyalgia. Pain (2019) 160:2589–602. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nagy-Szakal D, Williams BL, Mishra N, Che X, Lee B, Bateman L, et al. Fecal metagenomic profiles in subgroups of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome (2017) 5:44. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0261-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Reichenberger ER, Alexander GM, Perreault MJ, Russell JA, Schwartzman RJ, Hershberg U, et al. Establishing a relationship between bacteria in the human gut and complex regional pain syndrome. Brain Behav Immun (2013) 29:62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sheedy JR, Wettenhall RE, Scanlon D, Gooley PR, Lewis DP, McGregor N, et al. Increased d-lactic Acid intestinal bacteria in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. In Vivo (2009) 23:621–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shukla SK, Cook D, Meyer J, Vernon SD, Le T, Clevidence D, et al. Changes in gut and plasma microbiome following exercise challenge in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). PloS One (2015) 10:e0145453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Weber T, Tatzl E, Kashofer K, Holter M, Trajanoski S, Berghold A, et al. Fibromyalgia-associated hyperalgesia is related to psychopathological alterations but not to gut microbiome changes. PloS One (2022) 17:e0274026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yong D, Lee H, Min HG, Kim K, Oh HS, Chu MK. Altered gut microbiota in individuals with episodic and chronic migraine. Sci Rep (2023) 13:626. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-27586-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhao X, Chen Y, Li L, Zhai J, Yu B, Wang H, et al. Effect of DLT-SML on chronic stable angina through ameliorating inflammation, correcting dyslipidemia, and regulating gut microbiota. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol (2021) 77:458–69. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Morgan XC, Tickle TL, Sokol H, Gevers D, Devaney KL, Ward DV, et al. Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biol (2012) 13:R79. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mottawea W, Chiang CK, Mühlbauer M, Starr AE, Butcher J, Abujamel T, et al. Altered intestinal microbiota-host mitochondria crosstalk in new onset Crohn's disease. Nat Commun (2016) 7:13419. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kootte RS, Levin E, Salojärvi J, Smits LP, Hartstra AV, Udayappan SD, et al. Improvement of insulin sensitivity after lean donor feces in metabolic syndrome is driven by baseline intestinal microbiota composition. Cell Metab (2017) 26:611–619.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen W, Liu F, Ling Z, Tong X, Xiang C. Human intestinal lumen and mucosa-associated microbiota in patients with colorectal cancer. PloS One (2012) 7:e39743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang T, Cai G, Qiu Y, Fei N, Zhang M, Pang X, et al. Structural segregation of gut microbiota between colorectal cancer patients and healthy volunteers. Isme J (2012) 6:320–9. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yang T, Santisteban MM, Rodriguez V, Li E, Ahmari N, Carvajal JM, et al. Gut dysbiosis is linked to hypertension. Hypertension (2015) 65:1331–40. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Liu L, Wu Q, Chen Y, Ren H, Zhang Q, Yang H, et al. Gut microbiota in chronic pain: Novel insights into mechanisms and promising therapeutic strategies. Int Immunopharmacol (2023) 115:109685. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.109685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cohen SP, Wang EJ, Doshi TL, Vase L, Cawcutt KA, Tontisirin N. Chronic pain and infection: mechanisms, causes, conditions, treatments, and controversies. BMJ Med (2022) 1:e000108. doi: 10.1136/bmjmed-2021-000108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rojas M, Restrepo-Jiménez P, Monsalve DM, Pacheco Y, Acosta-Ampudia Y, Ramírez-Santana C, et al. Molecular mimicry and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun (2018) 95:100–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Duvallet C, Gibbons SM, Gurry T, Irizarry RA, Alm EJ. Meta-analysis of gut microbiome studies identifies disease-specific and shared responses. Nat Commun (2017) 8:1784. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01973-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Falony G, Joossens M, Vieira-Silva S, Wang J, Darzi Y, Faust K, et al. Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation. Science (2016) 352:560–4. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Armstrong G, Cantrell K, Huang S, McDonald D, Haiminen N, Carrieri AP, et al. Efficient computation of Faith's phylogenetic diversity with applications in characterizing microbiomes. Genome Res (2021) 31:2131–7. doi: 10.1101/gr.275777.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yin L, Wan YD, Pan XT, Zhou CY, Lin N, Ma CT, et al. Association between gut bacterial diversity and mortality in septic shock patients: A cohort study. Med Sci Monit (2019) 25:7376–82. doi: 10.12659/MSM.916808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Youngblut ND, de la Cuesta-Zuluaga J, Ley RE. Incorporating genome-based phylogeny and functional similarity into diversity assessments helps to resolve a global collection of human gut metagenomes. Environ Microbiola (2022) 24(9):3966–84. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]