Abstract

Introduction

The burden of multimorbidity is recognised increasingly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), creating a strong emphasis on the need for effective evidence-based interventions. A core outcome set (COS) appropriate for the study of multimorbidity in LMIC contexts does not presently exist. This is required to standardise reporting and contribute to a consistent and cohesive evidence-base to inform policy and practice. We describe the development of two COS for intervention trials aimed at the prevention and treatment of multimorbidity in LMICs.

Methods

To generate a comprehensive list of relevant prevention and treatment outcomes, we conducted a systematic review and qualitative interviews with people with multimorbidity and their caregivers living in LMICs. We then used a modified two-round Delphi process to identify outcomes most important to four stakeholder groups with representation from 33 countries (people with multimorbidity/caregivers, multimorbidity researchers, healthcare professionals, and policy makers). Consensus meetings were used to reach agreement on the two final COS. Registration: https://www.comet-initiative.org/Studies/Details/1580.

Results

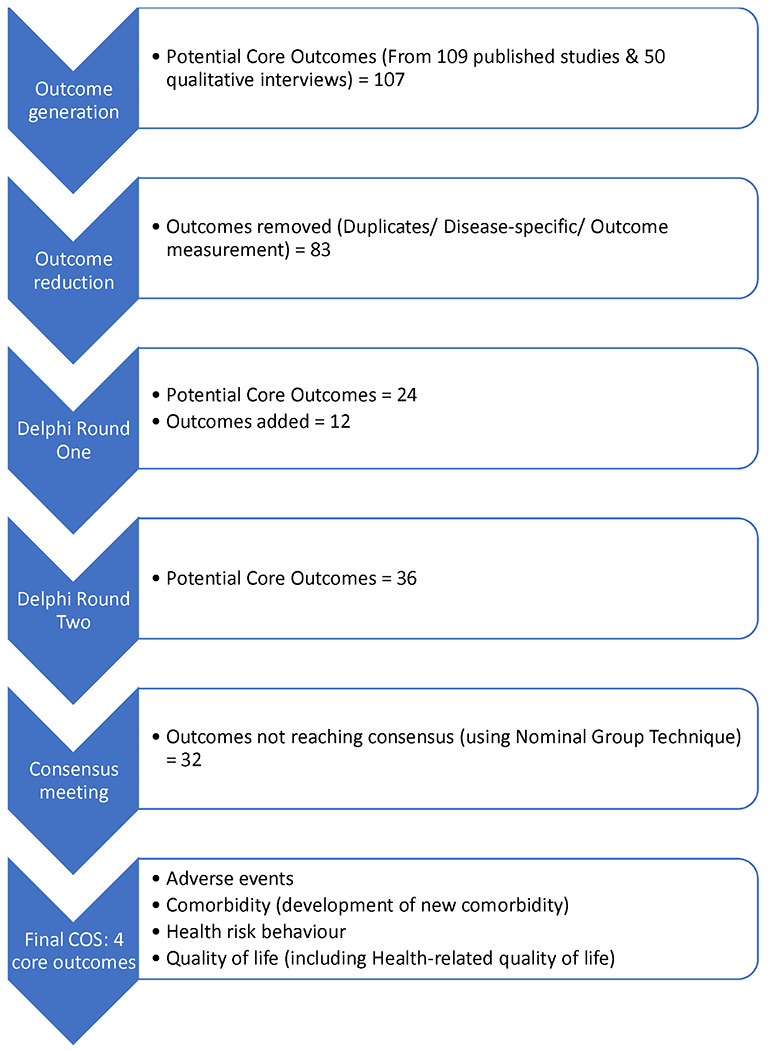

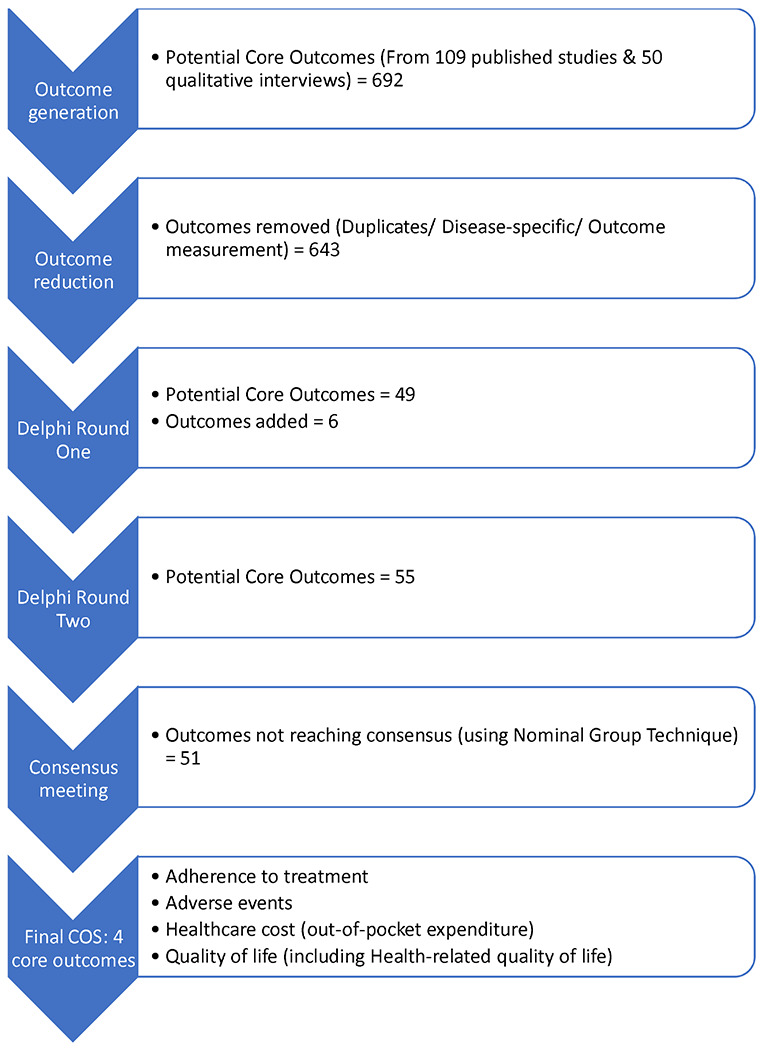

The systematic review and qualitative interviews identified 24 outcomes for prevention and 49 for treatment of multimorbidity. An additional 12 prevention, and six treatment outcomes were added from Delphi round one. Delphi round two surveys were completed by 95 of 132 round one participants (72.0%) for prevention and 95 of 133 (71.4%) participants for treatment outcomes. Consensus meetings agreed four outcomes for the prevention COS: (1) Adverse events, (2) Development of new comorbidity, (3) Health risk behaviour, and (4) Quality of life; and four for the treatment COS: (1) Adherence to treatment, (2) Adverse events, (3) Out-of-pocket expenditure, and (4) Quality of life.

Conclusion

Following established guidelines, we developed two COS for trials of interventions for multimorbidity prevention and treatment, specific to LMIC contexts. We recommend their inclusion in future trials to meaningfully advance the field of multimorbidity research in LMICs.

Keywords: Multimorbidity, Core outcome sets, Prevention, Treatment, LMICs

INTRODUCTION

Multimorbidity, defined as living with two or more long-term health conditions (1–3), is a growing public health challenge across the world (4–6). In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the pooled prevalence of multimorbidity in community settings is estimated to be around 30% (7). It is associated with considerable financial burden (8) and healthcare utilisation that creates strain on often poorly-resourced health systems (9). In addition, multimorbidity occurs at younger ages in LMICs, reducing quality of life, productivity, and life expectancy (10).

To prevent and improve the treatment of multimorbidity, evidence-based interventions are needed. However, the current heterogeneity of outcomes reported in trials and uncertainty about what should be measured hamper research efforts and limit the ability to compare and synthesise evidence of effectiveness across studies and settings (11). Also, the choice of outcomes tends to be driven by researchers’ interests, leading to concerns that the measured outcomes are more important to certain stakeholders, notably researchers and health professionals, people with lived experience of multimorbidity (12). This may be particularly the case in LMICs, where the patient and carer voice in health research and representation in research processes are often limited (13, 14), or can be marginalised due to challenges such as limited health literacy, low socioeconomic status, cultural stigma, and uncertain roles (15).

Core Outcome Sets (COS) are a minimum set of outcomes (i.e., measurements or observations used to capture the effect of interventions (16)) agreed by a range of stakeholders to be the most important for measuring and reporting in all studies relating to a specific health condition (17). The Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) Initiative has developed rigorous methods for COS identification that are continuously updated (18, 19). For studies addressing multimorbidity, a COS has been previously developed (20). However, it focused only on treatment and did not include prevention outcomes. Importantly, its preparatory work to identify candidate outcomes drew on published research mainly from North America (21). Further, the Delphi panel used to achieve consensus on the final COS did not have representation from LMIC contexts. These gaps are important to address, given that both health and economic data pertaining to multimorbidity suggest that prevention may be the best course of action (22). In addition, there are marked differences between high-income countries (HIC) and LMIC contexts in populations, healthcare systems, resources, the prevalence and presentation of health conditions, and the roles of family members and caregivers (23, 24). Outcomes identified as important in HICs may not be as relevant in LMIC contexts. Therefore, we aimed to develop two COS for future intervention studies relating to i) prevention and ii) treatment of multimorbidity among adults residing in LMICs.

METHODS

We followed best practices for COS development, as set out in the COMET guidelines (16). We report our steps using the Core Outcome Set-STandards for Reporting (COS-STAR) statement (25) (Appendix 1). The COSMOS project is registered with the COMET Initiative (https://www.comet-initiative.org/Studies/Details/1580).

Our COS development involved two main stages: (i) outcome generation stage (identifying a long-list of potential outcomes that have been or could be measured in trials) through systematic review and qualitative interviews, followed by (ii) an agreement stage on the relative importance of identified outcomes for inclusion in the COS, through Delphi surveys and consensus meetings. Outcomes relevant to the prevention and treatment of multimorbidity were considered separately at each of the stages. The overall study was guided by an expert group, which included global health multimorbidity researchers, clinicians, experts in COS development methods, as well as people from LMICs with lived experience of multimorbidity and carer representatives. The main steps of the different stages are described below, and the published protocol provides further details (26).

Outcome generation stage

Systematic review

We conducted a systematic review with a pre-registered protocol (PROSPERO: CRD42020197293) to identify outcomes reported in published trials and trial registrations of interventions for the prevention and treatment of multimorbidity in LMICs. Randomised (individual, cluster, and cross-over) studies of interventions (pharmacological, non-pharmacological, simple, and complex) for multimorbidity in adults (≥18 years) at risk of, or living with multimorbidity, in community, primary care, and hospital settings in LMICs were eligible for inclusion.

The search strategy was developed by an information specialist (JW) with inputs from research experts on multimorbidity in LMICs. It included terms for multimorbidity, trial design, and terms and names of LMICs, defined according to the 2019 World Bank classification (27). We searched 15 electronic databases, including trial registries, and LMIC-specific databases, from 1990 to July 2020 (Appendix 2). Each record was independently screened by two researchers, first by title and abstract, then by full texts of potentially relevant studies. Any discordance was resolved by discussion or consultation with a third researcher when required. Data on study characteristics, outcomes, and outcome measures were extracted from included studies by one researcher, with 10% of extractions cross-verified by a senior researcher. The objective of the review was to compile a list of previously studied outcomes rather than to summarise intervention effect; therefore study quality was not assessed (26).

Separate outcome lists were generated for prevention and treatment of multimorbidity, and outcomes were removed or combined based on the following criteria: duplicates, disease-specific (rather than relevant to multimorbidity), or outcome measurement metrics/tools rather than an outcome itself (e.g., biochemical measures such as lipid profile, HbA1c, etc., and questionnaires such as Short Form Health Survey (SF-36, SF-12, etc.)).

Qualitative interviews

To identify outcomes of importance to people with lived experience, qualitative interviews were conducted by enrolling consenting individuals (≥18 years), either living with or caring for someone with multimorbidity. Participants were selected from across a range of LMICs in diverse geographic locations. We used our existing research networks and partnerships to identify in-country research teams with experience of conducting interviews and available to perform data collection. Eligible participants were purposely recruited by these teams to achieve optimal variation according to age (over/under 65 years), sex (male/female), and type of healthcare utilisation (community or primary care/secondary or specialist care).

An information sheet written in plain language was provided to all participants to clarify concepts of outcomes and COS. Informed consent (written or recorded) in the local language was obtained prior to conducting interviews. A semi-structured interview guide was used, which was developed in English and translated into the appropriate local languages using standard forward and back translation techniques. The main topics included participants’ experience of living with [or caring for someone living with] multimorbidity and their view on what matters as the result of interventions to prevent or treat and/or care for their conditions. The interview schedule was published as part of the protocol (26). Interviews were conducted in-person by qualified interviewers in local languages and either audio-recorded or if not possible (because of technology limitations or the participant withholding consent), recorded in detailed interviewer notes. Sections of the recordings pertaining to health outcomes were transcribed manually by the local teams and translated into English. Anonymised transcripts were sent to the COSMOS team in York for analysis. Three team members (HK, JRB, RA) reviewed the extracted statements and identified individual multimorbidity prevention and treatment outcomes from them following iterative discussion.

Outcomes identified by the systematic review and interviews were assigned to either prevention or treatment lists or both as appropriate. Lay descriptions were constructed for each outcome and reviewed before finalisation to ensure understanding across all stakeholder groups. Lastly, the prevention and treatment outcomes were categorised for presentation to the Delphi panels, using Dodd’s outcome taxonomy comprising 38 categories across five core areas, namely death, physiological/clinical, life impact, resource use, and adverse events (28).

Agreement stage

Delphi surveys

We conducted two rounds of online Delphi surveys to reach consensus on the importance of each outcome identified by the outcome generation stage; separate surveys were conducted for prevention and treatment outcomes. Participants were purposively sought from across four stakeholder groups, namely (i) people living with multimorbidity and their caregivers, (ii) healthcare professionals, (iii) policy makers, and (iv) multimorbidity researchers. The identification and recruitment of participants used multiple strategies such as broadcasting through a project Twitter account, patient and public involvement groups, and COSMOS team networks (including other global health research groups, professional societies, non-government organisations relevant to multimorbidity, and government ministries). Additional strategies to recruit healthcare professionals and multimorbidity researchers included personalised emails sent to corresponding authors of studies included in our systematic review and flyers posted in partner research organisations.

We used the DelphiManager 5.0 platform, developed and maintained by the COMET Initiative (University of Liverpool) (18), to administer all surveys. The order of presenting outcome domains (based on Dodd’s taxonomy) was randomised to reduce bias. A lay description for each outcome was provided. Survey participants were asked to score the importance of each outcome for inclusion in the prevention and treatment COS, without considering its feasibility or measurability. For scoring, the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluations) 9-point Likert scale was used, with the following categories (16): ‘Not Important’ (scores 1-3), ‘Important but Not Critical’ (4–6), and ‘Critical for Inclusion’ (7–9). There was also an ‘Unable to Score’ response option, as well as the opportunity to suggest additional outcomes. For Delphi round one, for each outcome, we determined the proportion of scores in each of the GRADE categories, both overall and for each stakeholder group. All additional outcomes suggested by survey participants were reviewed for duplication and relevance by the research team, and those eligible (new distinct outcomes relevant to multimorbidity studies) were included in the Delphi round two surveys.

For Delphi round two, participants received their own round one scores, as well as the summary scores (overall and for each stakeholder group), with visual representation using histograms of the proportion of scores in each GRADE category. Participants were asked to re-score the importance of each outcome using the same 9-point Likert scale and to provide free-text reasons for any changes. Reminder emails were sent for both Delphi rounds until a minimum acceptable level of participation was achieved (70% overall, as advised by COS experts). Ratings from round two were analysed and summarised as for round one under the GRADE categories. Outcomes were then grouped according to the consensus definitions recommended by COMET (see Table 1) (11). To aid understanding of the findings and indicate clearly where there was consensus across stakeholder groups (or its absence), outcomes were presented in colour-coded tables (Table 1).

Table 1.

Criteria for categorisation of outcomes in the Delphi surveys

| Green | Outcomes scored ‘Critical for Inclusion’ (7-9) by ≥70% of respondents in all 4 stakeholder groups. |

| Purple | Outcomes scored ‘Critical for Inclusion’ (7-9) by ≥70% of respondents in 3 of 4 stakeholder groups. |

| Blue | Outcomes scored ‘Critical for Inclusion’ (7-9) by ≥70% of respondents in 2 of 4 stakeholder groups. |

| Yellow | Outcomes scored ‘Critical for Inclusion’ (7-9) by ≥70% of respondents in 1 of 4 stakeholder group. |

| Red | Outcomes scored ‘Critical for Inclusion’ (7-9) by <70% of the respondents in all 4 stakeholder groups. |

Consensus meetings

All Delphi participants were sent electronic invitations for the consensus meetings. A modified nominal group technique was used to discuss findings from the Delphi surveys and to develop agreements on critical outcomes for inclusion in the COS (16, 29, 30). Separate meetings were held for prevention and treatment outcomes, using the Zoom online platform (31) to maximise participation from multiple countries. Two pre-meeting sessions were held to orientate attendees to the purpose of the consensus meetings, scope of the COS, and the use of Zoom. In addition, an information pack describing the processes followed in the study and presenting results from the Delphi surveys using colour-coded tables (as described above), were sent to all participants before the meetings. Those participants unable to attend the virtual meetings were invited to send in their views by email.

At the start of each meeting, we reminded participants of the aim (i.e., developing consensus on the inclusion of outcomes in the COS), and outlined the meeting structure and process to ensure inclusive discussions. Meetings were facilitated by experts with extensive experience in COS development (JK, LR). Results from the Delphi surveys were presented. Outcomes scored as ‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% of Delphi respondents in all 4 stakeholder groups (colour-coded green, see Table 1) were included in the COS if they met the consensus meeting threshold of ≥80% voting for inclusion; otherwise, they underwent further discussion. Outcomes scored as ‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% of Delphi respondents in only one or no stakeholder groups (colour-coded yellow/red) were excluded without further discussion unless nominated to be ‘saved’ and supported by voting above a threshold of ≥80% by meeting participants. All outcomes scored as ‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% of Delphi respondents in two or three stakeholder groups (colour-coded blue/purple), were discussed further. Views shared by email by individuals unable to attend meetings were also fed into the meeting. Iterative rounds of whole-group and small-group discussions, facilitated by Google Jamboard, were used to categorise the outcomes for discussion into ‘Critical’ ‘Good to include’ and Not Important’. Discussions were followed by voting to include or exclude outcomes in the COS.

Following the consensus meetings, participants were emailed for a further vote on any outcomes for which consensus was not reached during the meetings, and for feedback on the wording and descriptions of outcomes voted for inclusion. The two final COS for prevention and treatment were compiled and sent to all consensus meeting participants for final endorsement.

Ethics and permission for data collection

Ethics approval for the research was obtained from the Health Sciences Research Governance Committee at the University of York (HSRGC/2020/409/D: COSMOS). Approvals were also obtained from relevant in-country ethics committees for all participating interview sites (Appendix 3). Informed consent (written or audio-recorded) in the local language was obtained from all participants prior to conducting interviews. All Delphi panellists and consensus meeting attendees also provided consent before participation.

Patient and public involvement

Four members of the steering committee overseeing the study were people living with multimorbidity and their caregivers. The study also benefited from advice from the NIHR IMPACT in South Asia Group (https://www.impactsouthasia.com/impact-group/) Community Advisory Panels and from the NCD Alliance (https://ncdalliance.org/), a civil society network, advocating for people with non-communicable diseases.

RESULTS

Outcome generation stage

Figures 1a & 1b show the steps of outcome generation related to the prevention and treatment of multimorbidity, respectively.

Figure 1a.

Development of COS for trials of interventions to prevent multimorbidity in LMICs.

Figure 1b.

Development of COS for trials of interventions to treat multimorbidity in LMICs.

Systematic review

Our searches yielded 17,267 records, with 16,949 remaining after removing duplication publications (Appendix 2). Following title and abstract screening, 16,705 records were excluded, and the remaining 243 papers were obtained. Full-text screening resulted in the exclusion of a further 134 records (Appendix 2). The remaining 109 randomised intervention studies on the prevention and treatment of multimorbidity conducted in at least 25 LMICs were included.

From these papers, 92 prevention and 236 treatment outcomes were extracted and reduced to 19 prevention and 38 treatment outcomes after removing duplicate outcomes, disease-specific outcomes, and outcome measurement metrics.

Qualitative interviews

The interviewees included five participants from each of the following ten countries: Afghanistan and Burkina Faso (low-income), Bangladesh, Ghana, Nepal, Nigeria, and Pakistan (lower-middle income), and Mexico, Peru, and Suriname (upper-middle income), totalling 50 interviewees. They comprised 37 people living with multimorbidity and 13 family caregivers. The distribution of socio-demographic characteristics was as follows: sex (46% male and 54% female), age (80% under 65 and 20% 65+ years), and type of healthcare utilisation (34% community/primary care and 66% secondary/specialist care). Participants reported having from two to five co-existing conditions, including tuberculosis, asthma, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, HIV, cancer, stroke, COPD, mental health disorders and others.

The interviews generated five further outcomes for prevention and 11 for treatment of multimorbidity (see Appendix 4 for example coding of qualitative data). Combining these outcome lists with the corresponding lists generated from the systematic review resulted in 24 outcomes for prevention and 49 for treatment of multimorbidity, which were classified according to Dodd’s taxonomy and presented in the Delphi round one surveys (Appendix 5).

Agreement stage

Table 2 summarises the characteristics of participants in the Delphi surveys and consensus meetings; Table 3 shows the outcomes scored as critical for inclusion at each of the agreement stages.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants in Delphi surveys and consensus meetings

| Name of survey/ meeting | Stakeholder group, n (%) | Age group, n (%) | Female, n (%) | Region, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delphi round 1, prevention survey (N = 132) | People living with multimorbidity/Caregivers = 29 (22.0) Healthcare professionals = 27 (20.4) Policy makers = 12 (9.1) Multimorbidity researchers = 64 (48.5) |

18-24 = 4 (3.0) 25-34 = 34 (25.7) 35-44 = 34 (25.7) 45-54 = 26 (19.7) 55-64 = 24 (18.2) 65+ = 10 (7.6) |

68 (51.5) | Low income = 6 (4.5) Lower middle income = 74 (56.1) Upper middle income = 15 (11.4) High income = 37 (28.0) |

| Delphi round 1, treatment survey (N = 133) | People living with multimorbidity/Caregivers = 30 (22.5) Healthcare professionals = 24 (18.0) Policy makers = 13 (9.8) Multimorbidity researchers = 66 (49.6) |

18-24 = 3 (2.2) 25-34 = 36 (27.0) 35-44 = 35 (26.3) 45-54 = 26 (19.5) 55-64 = 22 (16.5) 65+ = 11 (8.4) |

70 (52.6) | Low income = 4 (3.0) Lower middle income = 78 (58.6) Upper middle income = 17 (12.8) High income = 34 (25.6) |

| Delphi round 2, prevention survey (N = 95) | People living with multimorbidity/Caregivers = 24 (25.3) Healthcare professionals = 14 (14.7) Policy makers = 8 (8.4) Multimorbidity researchers = 49 (51.6) |

NA | 49 (51.6) | Low income = 5 (5.3) Lower middle income = 45 (47.4) Upper middle income = 10 (10.5) High income = 35 (36.8) |

| Delphi round 2, treatment survey (N = 95) | People living with multimorbidity/Caregivers = 22 (23.1) Healthcare professionals = 16 (16.8) Policy makers = 10 (10.5) Multimorbidity researchers = 47 (49.5) |

NA | 51 (53.7) | Low income = 5 (5.3) Lower middle income = 48 (50.5) Upper middle income = 11 (11.6) High income = 31 (32.6) |

| Consensus meeting, prevention (N = 19) | People living with multimorbidity/Caregivers = 3 (15.8) Healthcare professionals = 4 (21.0) Policy makers = 1 (5.3) Multimorbidity researchers = 11 (57.9) |

NA | 10 (52.6) | Low income = 1 (5.3) Lower middle income = 11 (57.9) Upper middle income = 1 (5.3) High income = 6 (31.6) |

| Consensus meeting, treatment (N = 14) | People living with multimorbidity/Caregivers = 1 (7.1) Healthcare professionals = 4 (28.6) Policy makers = 1 (7.1) Multimorbidity researchers = 8 (57.1) |

NA | 7 (50.0%) | Low income = 0 (0.0) Lower middle income = 6 (42.8) Upper middle income = 4 (28.6) High income = 4 (28.6) |

Table 3.

Critical outcomes selected in Delphi surveys and consensus meetings.

| Delphi round 1 | Delphi round 2 | Delphi results | Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention outcomes | |||

| ‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% of all participants | Voted ‘Critical for Inclusion’ (7-9) by ≥70% of all participants | ‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% in 4 (green), 3 (purple), and 2 (blue) stakeholder groups | Prevention COS |

| 1. Adherence to treatment 2. Adverse events 3. Cardiovascular event 4. Cardiovascular risk 5. Cognitive function 6. Comorbidity 7. Cost effectiveness 8. Death 9. Health-related quality of life 10. Obesity 11. Organ damage 12. Prevention of hypertension 13. Psychological wellbeing 14. Quality of life 15. Timely screening |

1. Adherence to treatment 2. Adverse events 3. Cardiovascular event 4. Cardiovascular risk 5. Chronic disease self-management* 6. Comorbidity 7. Cost effectiveness 8. Death 9. Health risk behaviour* 10. Health-related quality of life 11. Obesity 12. Organ damage 13. Prevention of hypertension 14. Psychological wellbeing 15. Quality of life 16. Timely screening |

Green-coded outcomes: 1. Adverse events 2. Cardiovascular event 3. Chronic disease self-management* 4. Comorbidity 5. Prevention of hypertension 6. Quality of life Purple-coded outcomes: 1. Cost effectiveness 2. Death 3. Obesity 4. Organ damage 5. Pain 6. Psychological wellbeing 7. Timely screening Blue-coded outcomes: 1. Adherence to treatment 2. Cardiovascular risk 3. Cognitive function 4. Diet 5. Early detection* 6. Health risk behaviour* 7. Health-related quality of life 8. Treatment satisfaction |

1. Adverse events 2. Comorbidity (development of new comorbidity) 3. Health risk behaviour* 4. Quality of life (including Health-related quality of life) |

| Other outcomes | Other outcomes | ‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% in 1 (yellow), or none (red) of the stakeholder groups | Not in COS, but suggested as additional outcome |

| 1. Diet 2. Exercise tolerance 3. Fatigue 4. Health literacy 5. Healthcare use 6. Pain 7. Reduced medication 8. Treatment satisfaction 9. Weight |

1. Carer burden* 2. Cognitive function 3. Diet 4. Early detection* 5. Exercise tolerance 6. Fatigue 7. Functioning/ADL* 8. Health anxiety* 9. Health literacy 10. Health seeking behaviour* 11. Healthcare use 12. Income* 13. Loneliness* 14. Pain 15. Perceived health* 16. Reduced medication 17. Self-efficacy* 18. Social functionality* 19. Treatment satisfaction 20. Weight |

Yellow-coded outcomes: 1. Carer burden* 2. Health literacy 3. Self-efficacy* 4. Weight Red-coded outcomes: 1. Exercise tolerance 2. Fatigue 3. Functioning/ADL* 4. Health anxiety* 5. Health seeking behaviour* 6. Healthcare use 7. Income* 8. Loneliness* 9. Perceived health* 10. Reduced medication 11. Social functionality* |

1. Healthcare use (including cost effectiveness) |

| Treatment outcomes | |||

| ‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% of all participants | ‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% of all participants | ‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% in 4 (green), 3 (purple), and 2 (blue) stakeholder groups | Treatment COS |

| 1. Adherence to treatment 2. Adverse events 3. Cardiovascular event 4. Cognitive function 5. Comorbidity 6. Cost effectiveness 7. Death 8. Healthcare access 9. Healthcare cost 10. Healthcare quality 11. Health-related quality of life 12. Increase in symptoms 13. Psychological wellbeing 14. Quality of life 15. Treatment satisfaction |

1. Adherence to treatment 2. Adverse events 3. Cardiac event risk 4. Cardiovascular event 5. Cognitive function 6. Comorbidity 7. Cost effectiveness 8. Death 9. Healthcare access 10. Healthcare cost 11. Healthcare quality 12. Health-related quality of life 13. Hospital admission 14. Illness under control 15. Psychological wellbeing 16. Quality of life 17. Treatment satisfaction |

Green-coded outcomes: 1. Adherence to treatment 2. Death 3. Healthcare access 4. Healthcare cost 5. Healthcare quality Purple-coded outcomes: 1. Adverse events 2. Cardiovascular event 3. Comorbidity 4. Cost effectiveness 5. Health-related quality of life 6. Healthcare staff communication 7. Increase in symptoms 8. Pain 9. Psychological wellbeing 10. Quality of life 11. Treatment burden** 12. Treatment satisfaction Blue-coded outcomes: 1. Cardiovascular risk 2. Cognitive function 3. Continuity of care** 4. Falls risk 5. Health risk behaviour 6. Healthcare use 7. Hospital admission 8. Hypertension 9. Illness under control 10. Obesity 11. Perceived health 12. Physical activity |

1. Adherence to treatment 2. Adverse events 3. Healthcare cost (out-of-pocket cost of treatment) 4. Quality of life (including Health-related quality of life) |

| Other outcomes | Other outcomes | ‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% in 1 (yellow), or none (red) of the stakeholder groups | Not in COS, but suggested as additional outcome |

| 1. Acceptance of illness 2. Aggression 3. Agitation 4. Appetite 5. Balance 6. Cardiac event risk 7. Carer burden 8. Diet 9. Domestic violence 10. Emotional regulation 11. Falls risk 12. Fatigue 13. Functioning/ADL 14. Health anxiety 15. Health literacy 16. Health risk behaviour 17. Healthcare staff communication 18. Healthcare use 19. Hospital admission 20. Hypertension 21. Illness resolution 22. Illness stigma 23. Illness under control 24. Income 25. Loneliness 26. Nausea 27. Obesity 28. Pain 29. Perceived health 30. Physical activity 31. Reduced medication 32. Self-management 33. Sleep quality 34. Weight |

1. Acceptance of illness 2. Aggression 3. Agitation 4. Appetite 5. Balance 6. Carer burden 7. Continuity of care** 8. Diet 9. Domestic violence 10. Emotional regulation 11. Falls risk 12. Fatigue 13. Frailty** 14. Functioning/ADL 15. Health anxiety 16. Health literacy 17. Health risk behaviour 18. Healthcare staff communication 19. Healthcare use 20. Hypertension 21. Illness resolution 22. Illness stigma 23. Income 24. Increase in symptoms 25. Loneliness 26. Nausea 27. Obesity 28. Pain 29. Perceived health 30. Physical activity 31. Polypharmacy** 32. Reduced medication 33. Self-esteem** 34. Self-management 35. Sleep quality 36. Social functionality** 37. Treatment burden** 38. Weight |

Yellow-coded outcomes: 1. Functioning/ADL 2. Illness resolution 3. Income 4. Polypharmacy** 5. Self-management 6. Sleep quality 7. Social functionality** Red-coded outcomes: 1. Acceptance of illness 2. Aggression 3. Agitation 4. Appetite 5. Balance 6. Carer burden 7. Diet 8. Domestic violence 9. Emotional regulation 10. Fatigue 11. Frailty** 12. Health anxiety 13. Health literacy 14. Illness stigma 15. Loneliness 16. Nausea 17. Reduced medication 18. Self-esteem** 19. Weight |

N/A |

Additional prevention outcomes suggested during Delphi round 1;

Additional treatment outcomes suggested during Delphi round 1 (see Appendix 5 for help text)

Delphi surveys

The Delphi round one prevention and treatment surveys were completed by 132 and 133 participants, respectively, with 127 completing both. The distribution of stakeholders was similar in both groups, with multimorbidity researchers making up almost half the sample, followed by people living with multimorbidity/caregivers (~22%), healthcare professionals (18-20%), and policy makers (<10%). Over half of the participants in both groups were 25-44 years old and women. The largest geographical representation in both groups was from lower middle-income countries (56-58%), followed by high income (25-28%), upper middle income (~12%), and low-income countries (<5%). The Delphi round two surveys were completed by 95 participants, for prevention (72.0% of round one) and treatment outcomes (71.4% of round one). By stakeholder groups, round two completions were >70% of round one participants for all groups, except healthcare professionals (66.7% in prevention and treatment surveys) and policymakers (51.8% in prevention survey).

Of the outcomes presented in Delphi round one, 15 (of 24) prevention and 15 (of 49) treatment outcomes were rated as ‘Critical for Inclusion’ (scores 7-9) by ≥70% of all participants (Table 3). Thirty-eight additional outcomes were proposed for prevention with 12 of them included in Delphi round two after reviewing for duplication, and relevance to multimorbidity. For treatment, six of 24 proposed additional outcomes were taken forward to Delphi round two. Overall, 36 prevention (24 generated from the review and interviews, and 12 additional suggestions by Delphi round one respondents) and 55 treatment outcomes (49 generated and 6 additional suggestions) were presented for rating in the Delphi round two surveys.

In the Delphi round two surveys, 16 (of 36) prevention and 17 (of 55) treatment outcomes were rated as ‘Critical for Inclusion’ (scores 7-9) by ≥70% of all participants (Table 3). Categorising by stakeholder groups, in the prevention list, six outcomes were coded green (‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% in all stakeholder groups), 15 were coded blue/purple (‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% in any three or two stakeholder groups), and 15 were coded yellow/red (‘Critical for Inclusion’ by ≥70% in one or none of the stakeholder groups); the treatment list included five (green), 31 (blue/purple), and 19 (yellow/red) outcomes, following the same categorisation (Table 3).

Consensus meetings

Prevention

The consensus meeting for prevention had 17 in-meeting and two email participants (Table 2), including 11 (57.9%) multimorbidity researchers, three people living with multimorbidity/caregivers (15.8%), four healthcare professionals (21.0%), and one policy maker (5.3%). Following the nominal group technique discussions, 32 of the 36 outcomes were excluded; there was consensus on the four outcomes presented below for inclusion in the prevention COS (Table 3).

‘Comorbidity’ and ‘Quality of life’ (both green-coded outcomes) received 93% of votes in the consensus meeting, but both outcomes were recommended for further discussion regarding their wording. Following these discussions, for the prevention COS, it was agreed ‘Comorbidity’ referred to the prevention of development of a new illness alongside the existing health condition being examined in a trial; the wording of this outcome was therefore amended as ‘Comorbidity (development of new comorbidity)’. Similarly, ‘Quality of life’ was reworded as ‘Quality of life (including Health-related quality of life)’, to reflect the consensus that the two outcomes should be combined (with researchers free to choose the most appropriate measure for their trial).

‘Adverse events’ (green-coded) did not initially reach the voting threshold of ≥80%, with those opposing its inclusion suggesting that measuring such events would be common practice across studies. However, it was included following further discussion and consensus among meeting participants, who considered it incorporated a range of negative outcomes for research teams to decide as appropriate for the multimorbidity prevention intervention being implemented.

The outcome ‘Health risk behaviours’ (blue-coded), proposed for the prevention COS during the Delphi round one survey, was similarly included following consensus discussions. The term was understood to include the range of behaviours considered to be risk factors for chronic conditions such as tobacco use, physical inactivity, and unhealthy diet.

The outcome ‘Healthcare use’ (including cost-effectiveness) generated considerable debate. While it was considered very important, it was argued that it might not be relevant to all trials. ‘Healthcare use’ did not reach the voting threshold for inclusion in the COS for this reason, but the meeting consensus was that it should be recommended as an important outcome to consider in relevant trials.

Treatment

The treatment consensus meeting comprised 12 in-meeting and two email participants (Table 2), including 8 (57.1%) multimorbidity researchers, four healthcare professionals (28.6%), one person living with multimorbidity/caregiver (7.1%), and one policy maker (7.1%). There was consensus on the following four outcomes as critical for inclusion (Table 3).

‘Adherence to treatment’ and ‘Healthcare costs’ (both green-coded outcomes) received 90% and 100% of votes respectively; additional clarification was added to the latter, stipulating it was specifically ‘out-of-pocket expenditure’ that was considered critical in LMIC studies, and as such this should be specified in the COS. The outcomes ‘Adverse events’ and ‘Quality of life’ (including Health-related quality of life) (both purple-coded) were included after further discussion and consensus. While it was agreed that death should be reported as an adverse event where relevant, the outcome ‘Death’ or ‘Mortality’ did not reach the threshold for inclusion separately (60% votes).

DISCUSSION

The COSMOS study followed rigorous participatory methods as recommended by COMET with representation from diverse geographies and stakeholder groups to develop two COS for use in future trials of interventions to prevent and to treat multimorbidity among adults living in LMICs. The two COS included four outcomes each, with ‘Adverse events’ and ‘Quality of life (including Health-related quality of life)’ featured in both sets. In addition, the prevention COS included ‘Development of new comorbidity’ and ‘Health risk behaviour’, whereas the treatment COS included ‘Adherence to treatment’ and ‘Out-of-pocket expenditure’ outcomes.

A previously developed COS for multimorbidity (COSmm) (20) with inputs from a systematic review of studies (21) and an expert panel, both solely from HICs, also included ‘Health-related quality of life’ among their highest-scoring outcomes. Our consensus panels voted to combine this outcome with the broader ‘Quality of life’ both in the prevention and treatment COS. This similarity between COSmm and our results suggests that the outcome ‘Quality of life’ may be relevant to multiple stakeholders and well-suited across diverse contexts to capture the impacts of living with multimorbidity. Nonetheless, further work on differentiating these constructs and their operationalisation will be necessary to translate this finding into actionable research and clinical practice (32, 33). The inclusion of ‘Adherence to treatment’ and ‘Healthcare costs’ are further similarities between COSmm and our treatment COS. However, while costs are only presented as a broad health systems outcome in COSmm, we specify its scope as covering out-of-pocket treatment costs to people living with multimorbidity, given that this can be an important source of catastrophic health expenditures and impoverishment in many LMICs (13, 34, 35).

‘Healthcare use’ was included in COSmm but did not reach a consensus for inclusion in our LMIC COS. This likely reflects differences across LMICs in the use of healthcare services (36). Additionally, the outcome may be severely limited in some LMICs due to lack of access to services (37). Nevertheless, it was considered an important outcome, which should be included (with or without cost-effectiveness) in some prevention studies, where appropriate. We considered it particularly important to develop a separate COS for the prevention of multimorbidity, given that the targets for prevention and treatment interventions are often different. In addition, as non-communicable diseases (with amenable risk factors) form a large proportion of the multimorbidity burden, a COS for prevention trials that will help build the evidence base is critical. With clear opportunities for implementing prevention strategies targeting risk factors (38), it is noteworthy that ‘Health risk behaviour’ has been included in our prevention COS.

Currently, most COS reflect priorities from HIC perspectives only, with very few including participants from LMICs and even fewer initiated in LMICs (13, 39, 40). Given that there are important differences in populations, disease patterns and healthcare systems between HIC and LMIC contexts (23, 24), our two COS for intervention studies to prevent and treat multimorbidity specifically in LMICs are likely to be more context-relevant, with greater applicability and adoptability in these settings (41). Another advantage of the COS will be more consistent and aligned outcome reporting in future multimorbidity trials, leading to systematic reviews that are more meaningful, as like-for-like outcomes can be combined in meta-analyses.

Having agreed COS for LMIC multimorbidity trials, further work is needed to review the evidence base and develop consensus on validated metrics or tools, which should be used to capture these outcomes. This was beyond the scope of the current study, but we have collated from our systematic review the measures and tools used to assess the six outcomes included in the two multimorbidity COS (see Appendix 6). Also, the large difference in the number of potential outcomes identified for prevention trials (N=107) and treatment trials (N=692) illustrates the need for more research on (and implementation of) of preventive interventions.

The strengths of our study include adherence to the recommended COMET guidelines (16) at both the outcome generation and agreement stages. We used a combination of rigorously conducted approaches (systematic review and qualitative interviews) to generate the initial lists of prevention and treatment outcomes, and multi-stage consensus building exercises involving a wide range of stakeholders across backgrounds, professions, and countries.

There are three key limitations to consider. First, unlike the interviews conducted in local languages, the Delphi surveys were administered in English, using the DelphiManager online platform, thereby limiting participation to individuals who could read or speak English and had a degree of confidence in using online tools. To mitigate the impact of this, support was provided by in-country research partners, but this was challenging to do consistently for Delphi round two, which led to higher than anticipated attrition. Nonetheless, the study achieved a satisfactory response rate in the round two surveys (>70.0% of round one participants for both prevention and treatment rounds), with representation from across 33 countries, which may not have been possible without using online tools.

Another limitation was that multimorbidity researchers were the largest stakeholder group in the agreement stages, with the risk that the consensus and final COS might largely reflect their views. Policymakers, on the other hand, had the least representation. However, our approach ensured that views were included from all four stakeholder groups at all consensus-building stages (Table 2). Delphi survey responses were summarised by stakeholder group, with agreement across groups being a key consideration in identifying outcomes as important. The selection of outcomes for the COS in consensus meetings also took account of their importance for all stakeholder groups.

Lastly, methods for COS development are evolving (42). While our approach adheres to the currently recommended steps and represents an advance over the previous COS for multimorbidity, the evidence base for developing consensus is limited (43) (for example, on the optimum way to present results in Delphi surveys, or to conduct discussions and achieve equitable, inclusive ranking or voting on outcomes). We further acknowledge that continued efforts are needed to understand the uptake and impact of COS, as demonstrated in other areas of health (44).

In addition, the definition of an intervention to prevent and/or treat multimorbidity might itself need further development (45). Repeatedly identified issues in the management of multimorbidity are the lack of integrated care and inadequate considerations of cross-treatment interactions, complications, and consequences (46). Interventions that consider these issues might be ones which have a planned positive impact on one or more conditions, while considerations are undertaken to minimise, reduce or avoid negative impacts from the presence of multimorbidity. Future efforts may be needed to include this broader scope.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the COSMOS study has developed two COS specifically for LMICs, to include in all intervention studies focusing on the prevention and treatment of multimorbidity. The two COS comprise four outcomes each, carefully selected using recommended standards, and therefore likely to be relevant and meaningful to a wide range of LMIC stakeholders, including people living with multimorbidity, their caregivers, multimorbidity researchers, healthcare professionals, and policy makers. Future research should identify and develop consensus on validated measures to assess these outcomes. Uptake of COS in future trials will promote consistency in outcome selection and reporting and thereby ensure the comparability of effectiveness across different studies on multimorbidity in LMICs.

Supplementary Material

KEY MESSAGES.

What is already known on this topic?

Although a Core Outcome Set (COS) for the study of multimorbidity has been previously developed, it does not include contributions from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Given the important differences in disease patterns and healthcare systems between high-income country (HIC) and LMIC contexts, a fit-for-purpose COS for the study of multimorbidity specific to LMICs is urgently needed.

What this study adds

Following rigorous guidelines and best practice recommendations for developing COS, we have identified four core outcomes for including in trials of interventions for the prevention and four for the treatment of multimorbidity in LMIC settings.

The outcomes ‘Adverse events’ and ‘Quality of life (including Health-related quality of life)’ featured in both prevention and treatment COS. In addition, the prevention COS included ‘Development of new comorbidity’ and ‘Health risk behaviour’, whereas the treatment COS included ‘Adherence to treatment’ and ‘Out-of-pocket expenditure’ outcomes.

How this study might affect research, practice, or policy

The multimorbidity prevention and treatment COS will inform future trials and intervention study designs by helping promote consistency in outcome selection and reporting.

COS for multimorbidity interventions that are context-sensitive will likely contribute to reduced research waste, harmonise outcomes to be measured across trials, and advance the field of multimorbidity research in LMIC settings to enhance health outcomes for those living with multimorbidity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding for the DelphiManager software licence was provided by the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases (GACD). We also thank the GACD for publicising the Delphi exercises across their networks.

We thank all the patient advisers and caregivers for their participation at different stages of the study. We also thank all the researchers, healthcare professionals, and policy makers who participated in the Delphi surveys and consensus meetings.

FUNDING

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Grants 17/63/130 NIHR Global Health Research Group: Improving Outcomes in Mental and Physical Multimorbidity and Developing Research Capacity (IMPACT) in South Asia and Grant NIHR203248 Global Health Centre for Improving Mental and Physical Health Together using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK government. Oscar Flores-Flores is supported by the Fogarty International Center and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), United States under Award Number K43TW011586. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This work was also supported by the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases (GACD) Multimorbidity Subgroup and by members of the World Psychiatric Association Comorbidity Section. The GACD also part funded the DelphiManager software.

The NCD Alliance provided advice on engaging people with multimorbidity and publicised the study.

Members of the ‘COSMOS collaboration’ (collective authorship), in alphabetical order:

1. Afaq, Saima; Khyber Medical University, Institute of Public Health and Social Sciences; Imperial College London, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics

2. Agarwal, Gina; McMaster University Faculty of Health Sciences, Family Medicine

3. Aguilar-Salinas, Carlos; Salvador Zubiran National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition, Endocrinology and Metabolism

4. Akinroye, Kingsley; Nigerian Heart Foundation

5. Akinyemi, Rufus Olusola; University of Ibadan, Neuroscience and Ageing Research Unit, Institute for Advanced Medical Research and Training

6. Ali, Syed Rahmat; Khyber Medical University

7. Aman, Rabeea; Foundation University Islamabad

8. Appuhamy, Koralagamage Kavindu; University of York, Department of Health Sciences

9. Baldew, Se-Sergio; Anton de Kom University of Suriname, Physical Therapy Department

10. Barbui, Corrado; University of Verona, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement Sciences, Section of Psychiatry

11. Barrios, Niels Victor Pacheco; Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, CRONICAS Center of Excellence in Chronic Diseases

12. Bich, Phuong Tran; University of Antwerp, Department of Family Medicine and Population Health

13. Caamaño, María del Carmen; Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, School of Natural Sciences

14. Del Castillo Fernández, Darwin; Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, CRONICAS Center of Excellence in Chronic Diseases

15. Haidar, Asiful; ARK foundation, Bangladesh,

16. Praveen, Devarsetty; The George Institute for Global Health India

17. Downey, Laura; UNSW; Imperial College London

18. Teixeira, Noemia; University of York, Department of Health Sciences

19. Flores-Flores, Oscar; Universidad de San Martin de Porres Facultad de Medicina Humana, Centro de Investigacion del Envejecimiento (CIEN); Universidad Cientifica del Sur Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud

20. Gomez, Gerardo Zavala; University of York, Department of Health Sciences

21. Holt, Richard; University of Southampton, Human Development and Health, Faculty of Medicine

22. Huque, Rumana; ARK Foundation, Research and Development; University of Dhaka, Department of Economics

23. Kabukye, Johnblack; Uganda Cancer Institute; Stockholm University, SPIDER, Department of Computer and Systems Sciences

24. Kanan, Sushama; ARK foundation, Bangladesh

25. Khalid, Humaira; Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning

26. Koly, Kamrun; International Centre for Diarrheal Diseases Research, Bangladesh

27. Kwashie, Joseph Senyo; Community and Family Aid Foundation

28. Levitt, Naomi S.; University of Cape Town

29. Lopez-Jaramillo, Patricio; Universidad de Santander, Masira Research Institute, Medical School

30. Mohan, Sailesh; Public Health Foundation of India

31. García, Olga P.; Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, School of Natural Sciences

32. Prasad-Muliyala, Krishna; National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences

33. Naz, Qirat; Benazir Bhutto Hospital, Institute of Psychiatry

34. Odili, Augustine; University of Abuja College of Health Sciences, Circulatory Health Research Laboratory

35. van Olmen, Josefien; University of Antwerp, Department of Primary and Interdisciplinary Care

36. Oyeyemi, Adewale; Arizona State University, College of Health Solutions; University of Maiduguri, Department of Physiotherapy

37. Purgato, Marianna; University of Verona, Neurosciences, Biomedicine and Movement Sciences

38. Zafra-Tanaka, Jessica; Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, CRONICAS Center of Excellence in Chronic Diseases

39. Anza-Ramírez, Cecilia; Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, CRONICAS Centre of Excellence in Chronic Diseases

40. Rodrigues Batista, Sandro Rogerio; Universidade Federal de Goiás, Family Medicine and Primary Health Care

41. Ronquillo, Dolores; Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, School of Natural Sciences

42. Siddiqi, Kamran; University of York, Department of Health Sciences; Hull York Medical School

43. Singh, Rakesh; KIST Medical College, Department of Public Health

44. Tufail, Pervaiz; University of York, Department of Health Sciences

45. García Ulloa, Ana Cristina; Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Medicas y Nutricion Salvador Zubiran, CAIPaDi

46. Uphoff, Eleonora; University of York, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

47. Verhey, Ruth; University of Zimbabwe, Research Support Centre, College of Health Sciences

48. Wright, Judy; University of Leeds Leeds Institute of Health Sciences

49. Zhao, Yang; Peking University Health Science Centre, The George Institute for Global Health; WHO, Collaborating Centre on Implementation Research for Prevention & Control of NCDs

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

None declared.

Contributor Information

Aishwarya Lakshmi Vidyasagaran, University of York, Department of Health Sciences.

Rubab Ayesha, Rawalpindi Medical University; Foundation University School of Science and Technology.

Jan Boehnke, University of Dundee, School of Health Sciences; University of York, Department of Health Sciences.

Jamie Kirkham, The University of Manchester, Centre for Biostatistics; Manchester Academic Health Science Centre.

Louise Rose, King’s College London Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing Midwifery & Palliative Care.

John Hurst, University College London, Department of Respiratory Medicine.

J. Jaime Miranda, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, CRONICAS Center of Excellence in Chronic Diseases; The George Institute for Global Health.

Rusham Zahra Rana, The Healing Triad Pakistan.

Rajesh Vedanthan, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Section for Global Health, Department of Population Health.

Mehreen Faisal, University of York, Department of Health Sciences.

Najma Siddiqi, University of York, Department of Health Sciences; Hull York Medical School.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston MC, Crilly M, Black C, Prescott GJ, Mercer SW. Defining and measuring multimorbidity: a systematic review of systematic reviews. European journal of public health. 2019;29(1):182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho IS, Azcoaga-Lorenzo A, Akbari A, Davies J, Khunti K, Kadam UT, et al. Measuring multimorbidity in research: Delphi consensus study. BMJ medicine. 2022;1(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Academy of Medical Sciences. Multimorbidity: a priority for global health research. London, UK: Academy of Medical Sciences; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Y, Atun R, Oldenburg B, McPake B, Tang S, Mercer SW, et al. Physical multimorbidity, health service use, and catastrophic health expenditure by socioeconomic groups in China: an analysis of population-based panel data. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(6):e840–e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chowdhury SR, Das DC, Sunna TC, Beyene J, Hossain A. Global and regional prevalence of multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen H, Manolova G, Daskalopoulou C, Vitoratou S, Prince M, Prina AM. Prevalence of multimorbidity in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Journal of comorbidity. 2019;9:2235042X19870934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagstaff A, Eozenou P, Smitz M. Out-of-pocket expenditures on health: a global stocktake. The World Bank Research Observer. 2020;35(2):123–57. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JT, Hamid F, Pati S, Atun R, Millett C. Impact of noncommunicable disease multimorbidity on healthcare utilisation and out-of-pocket expenditures in middle-income countries: cross sectional analysis. PloS one. 2015;10(7):e0127199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basto-Abreu A, Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Wade AN, Oliveira de Melo D, Semeão de Souza AS, Nunes BP, et al. Multimorbidity matters in low and middle-income countries. Journal of multimorbidity and comorbidity. 2022;12:26335565221106074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, Devane D, Gargon E, et al. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials. 2012;13(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schünemann HJ, Tunis S, Nieuwlaat R, Wiercioch W, Baldeh T. Controversy and Debate Series on Core Outcome Sets: The SOLAR (Standardized Outcomes Linking Across StakeholdeRs) system and hub and spokes model for direct core outcome measures in health care and its relation to GRADE. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2020;125:216–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee A, Davies A, Young AE. Systematic review of international Delphi surveys for core outcome set development: representation of international patients. BMJ open. 2020;10(11):e040223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phuong Bich Tran AA, Lall Dorothy, Ddungu Charles, Pinkney-Atkinson Victoria J., Ayesha Rubab, Boehnke Jan R., van Olmen Josefien, on behalf of the COSMOS collaboration. An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the lived experience of people with multimorbidity in low- and middle-income countries. Accepted at BMJ Global Health. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janic A, Kimani K, Olembo I, Dimaras H. Lessons for patient engagement in research in low-and middle-income countries. Ophthalmology and Therapy. 2020;9:221–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, Barnes KL, Blazeby JM, Brookes ST, et al. The COMET handbook: version 1.0. Trials. 2017;18:1–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prinsen CA, Vohra S, Rose MR, Boers M, Tugwell P, Clarke M, et al. How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set”–a practical guideline. Trials. 2016;17(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.COMET Initiative. Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials 2011. [Available from: www.comet-initiative.org.

- 19.Gargon E, Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Tunis S, Clarke M. The COMET Initiative database: progress and activities update (2015). Trials. 2017;18(1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith SM, Wallace E, Salisbury C, Sasseville M, Bayliss E, Fortin M. A core outcome set for multimorbidity research (COSmm). The Annals of Family Medicine. 2018;16(2):132–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith SM, Wallace E, O’Dowd T, Fortin M. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McPhail SM. Multimorbidity in chronic disease: impact on health care resources and costs. Risk management and healthcare policy. 2016:143–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu X, Mishra GD, Jones M. Mapping the global research landscape and knowledge gaps on multimorbidity: a bibliometric study. Journal of global health. 2017;7(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurst JR, Agarwal G, van Boven JF, Daivadanam M, Gould GS, Huang EW-C, et al. Critical review of multimorbidity outcome measures suitable for low-income and middle-income country settings: perspectives from the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases (GACD) researchers. BMJ open. 2020;10(9):e037079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, Devane D, et al. Core outcome set–STAndards for reporting: the COS-STAR statement. PLoS medicine. 2016;13(10):e1002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boehnke JR, Rana RZ, Kirkham JJ, Rose L, Agarwal G, Barbui C, et al. Development of a core outcome set for multimorbidity trials in low/middle-income countries (COSMOS): study protocol. BMJ open. 2022;12(2):e051810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups [Internet]. 2019.

- 28.Dodd S, Clarke M, Becker L, Mavergames C, Fish R, Williamson PR. A taxonomy has been developed for outcomes in medical research to help improve knowledge discovery. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2018;96:84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harvey N, Holmes CA. Nominal group technique: an effective method for obtaining group consensus. International journal of nursing practice. 2012;18(2):188–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manera K, Hanson CS, Gutman T, Tong A. Consensus methods: nominal group technique. 2019.

- 31.Zoom Video Communications Incorporation. Zoom Privacy Statement. 2022.

- 32.Mayo NE, Figueiredo S, Ahmed S, Bartlett SJ. Montreal accord on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) use series–paper 2: terminology proposed to measure what matters in health. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2017;89:119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costa DS, Mercieca-Bebber R, Rutherford C, Tait M-A, King MT. How is quality of life defined and assessed in published research? Quality of Life Research. 2021;30:2109–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reid E, Ghoshal A, Khalil A, Jiang J, Normand C, Brackett A, et al. Out-of-pocket costs near end of life in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLOS Global Public Health. 2022;2(1):e0000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sum G, Hone T, Atun R, Millett C, Suhrcke M, Mahal A, et al. Multimorbidity and out-of-pocket expenditure on medicines: a systematic review. BMJ global health. 2018;3(1):e000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonfrer I, Van de Poel E, Grimm M, van Doorslaer E. Does health care utilization match needs in Africa? Challenging conventional needs measurement. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anselmi L, Lagarde M, Hanson K. Health service availability and health seeking behaviour in resource poor settings: evidence from Mozambique. Health economics review. 2015;5(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Head A, Fleming K, Kypridemos C, Pearson-Stuttard J, O’Flaherty M. Multimorbidity: the case for prevention. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75(3):242–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karumbi J, Gorst SL, Gathara D, Gargon E, Young B, Williamson PR. Inclusion of participants from low-income and middle-income countries in core outcome sets development: a systematic review. BMJ open. 2021;11(10):e049981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis K, Gorst SL, Harman N, Smith V, Gargon E, Altman DG, et al. Choosing important health outcomes for comparative effectiveness research: an updated systematic review and involvement of low and middle income countries. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0190695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gargon E, Gurung B, Medley N, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, et al. Choosing important health outcomes for comparative effectiveness research: a systematic review. PloS one. 2014;9(6):e99111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chevance A, Tran V-T, Ravaud P. Controversy and debate series on core outcome sets. paper 1: improving the generalizability and credibility of core outcome sets (COS) by a large and international participation of diverse stakeholders. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2020;125:206–12.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humphrey-Murto S, Crew R, Shea B, Bartlett SJ, March L, Tugwell P, et al. Consensus building in OMERACT: recommendations for use of the Delphi for core outcome set development. The Journal of rheumatology. 2019;46(8):1041–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tugwell P, Boers M, Brooks P, Simon L, Strand V, Idzerda L. OMERACT: an international initiative to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology. Trials. 2007;8(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skou ST, Mair FS, Fortin M, Guthrie B, Nunes BP, Miranda JJ, et al. Multimorbidity. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2022;8(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moffat K, Mercer SW. Challenges of managing people with multimorbidity in today’s healthcare systems. BMC family practice. 2015;16(1):1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.