Evidence maps illustrate connections between racism and social and structural determinants of health exposures, and nine outcome domains of maternal health and morbidity.

Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To identify the social–structural determinants of health risk factors associated with maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States during the prenatal and postpartum periods.

DATA SOURCES:

We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Social Sciences Citation Index through November 2022 for eligible studies that examined exposures related to social and structural determinants of health and at least one health or health care–related outcome for pregnant and birthing people.

METHODS OF STUDY SELECTION:

After screening 8,378 unique references, 118 studies met inclusion criteria.

TABULATION, INTEGRATION, AND RESULTS:

We grouped studies by social and structural determinants of health domains and maternal outcomes. We used alluvial graphs to summarize results and provide additional descriptions of direction of association between potential risk exposures and outcomes. Studies broadly covered risk factors including identity and discrimination, socioeconomic, violence, trauma, psychological stress, structural or institutional, rural or urban, environment, comorbidities, hospital, and health care use. However, these risk factors represent only a subset of potential social and structural determinants of interest. We found an unexpectedly large volume of research on violence and trauma relative to other potential exposures of interest. Outcome domains included maternal mortality, severe maternal morbidity, hypertensive disorders, gestational diabetes, cardiac and metabolic disorders, weathering depression, other mental health or substance use disorders, and cost per health care use outcomes. Patterns between risk factors and outcomes were highly mixed. Depression and other mental health outcomes represented a large proportion of medical outcomes. Risk of bias was high, and rarely did studies report the excess risk attributable to a specific exposure.

CONCLUSION:

Limited depth and quality of available research within each risk factor hindered our ability to understand underlying pathways, including risk factor interdependence. Although recently published literature showed a definite trend toward improved rigor, future research should emphasize techniques that improve the ability to estimate causal effects. In the longer term, the field could advance through data sets designed to fully ascertain data required to robustly examine racism and other social and structural determinants of health, their intersections, and feedback loops with other biological and medical risk factors.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW REGISTRATION:

PROSPERO, CRD42022300617.

Despite spending more on maternity care than any other country, maternal deaths have risen in the United States since 2000, and risk of death from complications related to pregnancy and childbirth exceeds that of any other high-income country.1 This becomes more alarming considering that maternal morbidity and mortality serve as key indicators of the health and well-being of a country. Furthermore, risk of maternal morbidity and mortality is unevenly distributed in the United States, with Black and Indigenous women three to four times more affected than their White counterparts.2,3 Efforts to explain such high rates of maternal morbidity and mortality along with pronounced inequities in maternal outcomes have fallen short, because research has focused mainly on birth and infant outcomes, with limited consideration of the multiple factors that broadly affect maternal health.1,3

To better understand racism and the social–structural determinants of health that underlie maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States, the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Office of Disease Prevention requested this systematic review as part of a planned Pathways to Prevention workshop cosponsored by the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities; and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The NIH Office of Disease Prevention anticipated that risk of postpartum maternal morbidity and mortality would be influenced by the complex interplay between individual, family, community, and social–structural factors that drive health. Our objective for this review was to identify the social–structural determinants of health risk factors associated with maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States during the prenatal and postpartum periods.

SOURCES

The methods for this systematic review followed the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews,4 modified for risk factor research. We report in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) and the ROSES (Reporting Standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses) flow diagram.5,6 The final protocol was posted online on December 9, 2021 (https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/maternal-morbidity-mortality/protocol). Additional review details, including our risk of bias assessment tool, can be found as part of the full systematic review posted on the AHRQ and Pathways to Prevention websites (https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/maternal-morbidity-mortality/research; prevention.nih.gov/P2P-PostpartumHealth). Our key questions were, 1) From a pregnant person’s potential entry into prenatal care, what combinations of risk indicators have the greatest prediction of poor postpartum health outcomes? And 2) Immediately before or immediately after delivery and before release from birthing-related hospitalization or clinical care, what combinations of risk indicators to the birthing person have the greatest prediction of poor postpartum health outcomes?

STUDY SELECTION

We selected studies if they were published in English in a peer-reviewed journal between 2000 and 2022 (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/D538). Pregnant study participants needed to have been pregnant for 20 or more weeks (we based this inclusion criteria on obstetric terminology and convention, which informs many disease definitions, such as preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, and on categorization of loss of pregnancy before 20 weeks of gestation as miscarriage). We selected observational studies that were designed to be comparative, included some method to control for selection bias (eg, propensity scores, instrumental variables, multivariate regression), and examined the effect of at least one risk factor indicative of social determinants of health. We included studies that examined factors that acted interpersonally. Additional exclusion and inclusion criteria are summarized in Appendix 2 (available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/D538). During the screening period, each full text review was conducted independently and, if there was any question about whether factors were interpersonal, the reviewers would meet to discuss and resolve. If unable to resolve, a third investigator would be included.

We searched for literature in the following databases: MEDLINE (via Ovid), CINAHL (via EBSCOHost), and Social Sciences Citation Index (via Web of Science) through November 2022. The searches included controlled vocabulary terms (eg, MeSH or CINAHL headings), along with free-text words related to maternal mortality and morbidity, pregnancy, prenatal care, postpartum care, health disparities, and measures of risk indices (Appendix 2, http://links.lww.com/AOG/D538). We searched reference lists of relevant existing systematic reviews for additional eligible studies.

Search results were screened using PICO Portal (www.picoportal.org). Two trained, independent investigators screened titles and abstracts based on Appendix 1 (http://links.lww.com/AOG/D538) framework and study design. Two independent investigators then performed full-text screening to determine whether studies met inclusion criteria. Differences in screening decisions were resolved by consultation between investigators, and, if necessary, consultation with a third investigator. We documented the inclusion and exclusion status of citations at full-text screening, noting reasons for exclusion. Throughout the screening process, team members met regularly to ensure consistency of inclusion criteria application. Given the unexpectedly large number of eligible studies after full-text screening along with the complexity of the topic and the heterogeneity of exposure domains captured in the studies, we performed an additional full-text appraisal to focus on the studies best designed, including analytical approaches, to answer the key questions. That is, we focused on the research that attempted to explain the mechanisms underlying the disparities. Our research team subjectively prioritized studies according to study design and rigor of analytic approaches to address selection bias based on the ROBINS-E tool.7 We determined that all included studies were at high risk of bias from a causal standpoint. Therefore, we continued with the review from the perspective of supporting future researchers in generating hypotheses for risk factors as the basis for potential interventions.

Evidence tables and full reference lists of included studies are provided in Appendices 3 and 4 (available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/D538). The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board does not review systematic reviews, and this review does not include individual data or information; therefore, it was determined that institutional review board exemption or review was not needed.

RESULTS

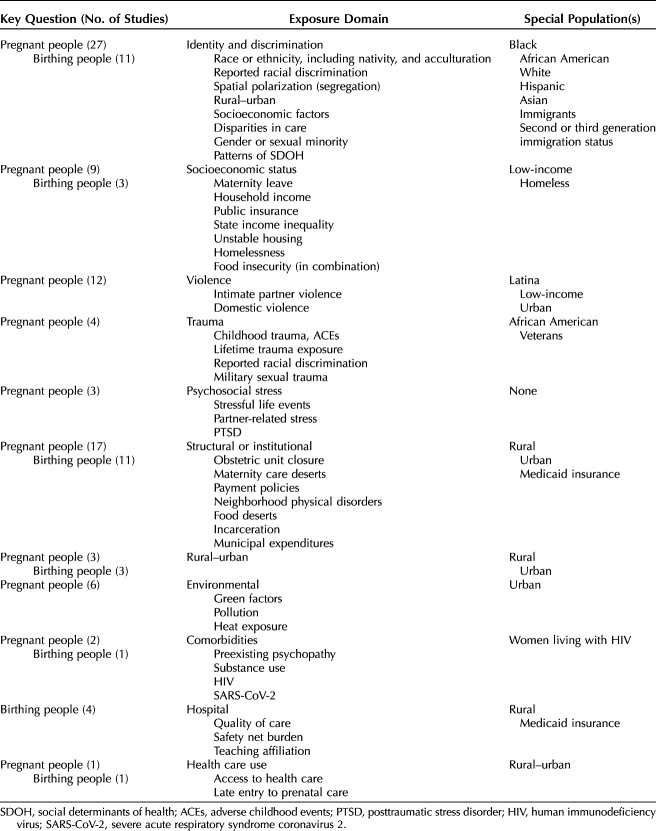

Our search identified 8,378 unique publications for screening. Based on inclusion criteria, we identified 118 eligible studies that were published between 2000 and 2022 (Appendix 5, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/D538). The studies contained 221 specifically named exposures or factors of interest. Although many of these exposures or factors of interest are comparable or overlap, the studies used various language and operational definitions for them. Using the named exposures, we categorized the studies into 11 broad exposure domains based on the main or primary social–structural determinants of health as indicated by study authors in their stated study aim. We then aggregated the studies into the themes that were empirically developed by looking at the entire literature set. Table 1 presents the number of included studies by key question, exposure domain, and population. The exposure domains are illustrated by examples of named exposure or factor of interest.

Table 1.

Identified Eligible Studies by Major Exposure Domain and Key Question

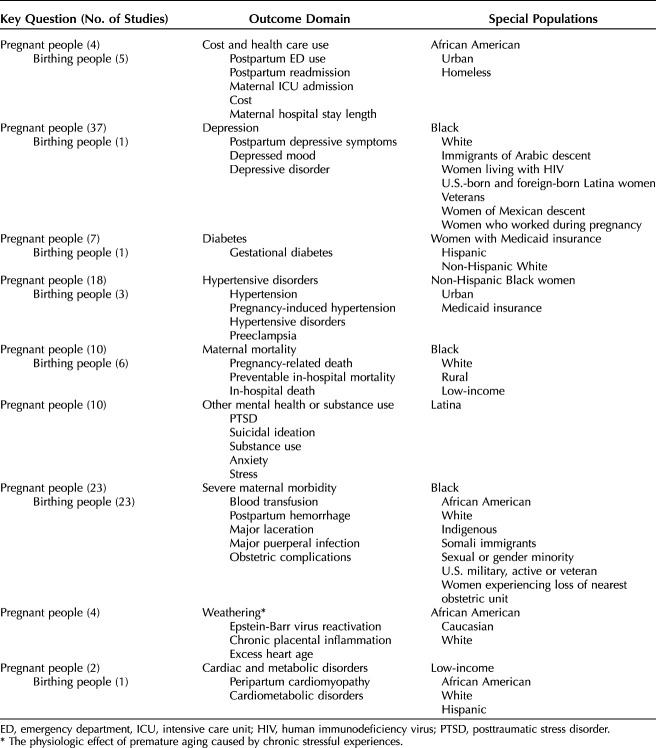

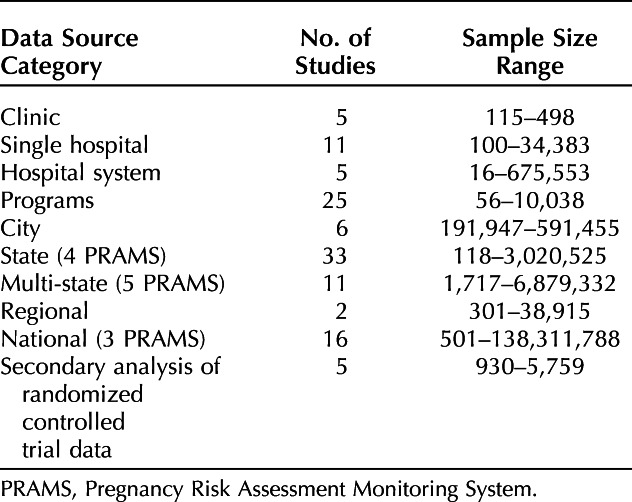

Table 2 presents the number of included studies by key question, outcome domain, and special populations for those outcomes. The outcome domains are illustrated by examples of named outcome variables from included studies. Categories of data sources are provided in Table 3. Included data varied widely in sample sizes, and sources varied widely across studies, ranging from as small as 16 women, whose deaths were examined for potential preventability, to several million pregnant or birthing people.

Table 2.

Identified Eligible Studies by Outcome Domain and Key Question

Table 3.

Data Sources, Number of Studies, and Sample Size Ranges

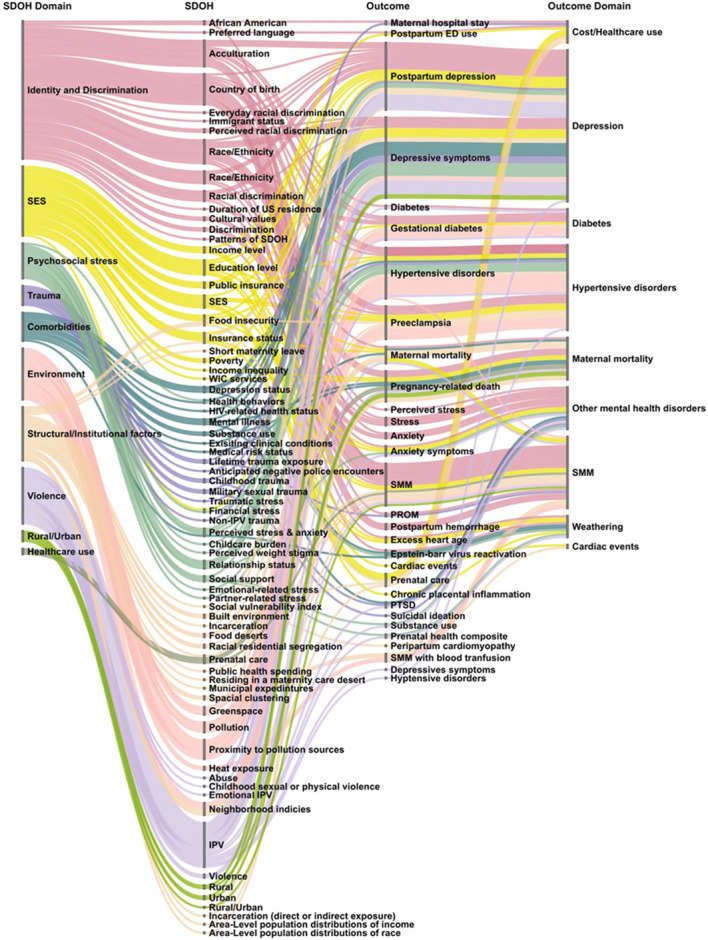

Overall, 65 unique studies addressed the combination of risk indicators that predict poor postpartum health outcomes for pregnant people on their potential entry into prenatal care (key question 1). Figure 1 illustrates the complex connections between social–structural determinants of health (10 exposure domains) and nine outcome domains with alluvial or colored paths. Depression was the most commonly examined outcome domain. Other highly studied outcome domains included hypertensive disorders, maternal mortality, and severe maternal morbidity. Weathering, physiologic changes, and premature aging caused by extended exposure to stressful experiences, was a smaller, less studied outcome domain.8

Fig. 1. Reported exposures and outcomes for pregnant people. Colored paths connect risk factor and outcome domains. Each outcome domain is represented by a different color; by following the colors from left to right from the social–structural determinants of health (SDOH) domain, a reader can see which outcomes an SDOH is affecting. The outer two columns display the SODH and outcome domains categorized in this review. The inner two columns give more detailed information about the specific exposure or outcome measures named in the studies. The unit of display is the individual risk factor or outcome; therefore, the total number of individual risk factors, or individual outcomes, may be greater than the total number of studies. Thicker lines indicate that more studies examined a given risk factor or outcome; thinner lines indicate fewer studies. SES, socioeconomic status; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IPV, intimate partner violence; ED, emergency department; SMM, severe maternal morbidity; PROM, prelabor rupture of membranes; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Neerland. Determinants for Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Obstet Gynecol 2024.

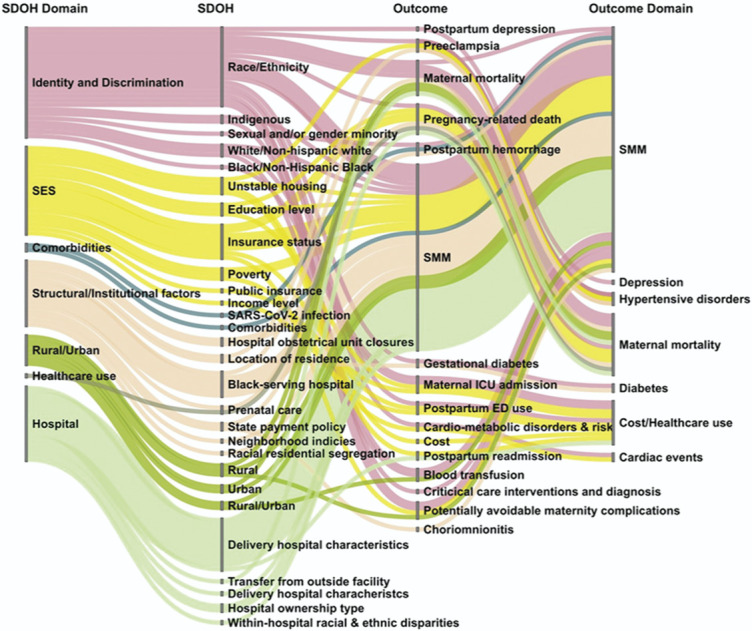

We identified 31 unique studies that addressed the combination of risk indicators that predict poor postpartum health outcomes for birthing people (key question 2). Figure 2 uses alluvial colored paths to show connections between social–structural determinants of health and outcome domains. Seven risk-factor domains mapped to seven outcome domains, with all risk-factor domains mapping to severe maternal morbidity, and all but environmental factors mapping to maternal mortality. Less commonly examined outcome domains included cardiac and metabolic disorders, diabetes, hypertension disorders, depression, and cost per health care use, all of which connected to four or fewer risk factor domains.

Fig. 2. Reported exposures and outcomes for birthing people. Colored paths connect risk factor and outcome domains. Each outcome domain is represented by a different color; by following the colors from left to right from the social–structural determinants of health (SDOH) domain, a reader can see which outcomes an SDOH is affecting. The outer two columns display the SDOH and outcome domains categorized in this review. The inner two columns give more detailed information about the specific exposure or outcome measures named in the studies. The unit of display is the individual risk factor or outcome; therefore, the total number of individual risk factors, or individual outcomes, may be greater than the total number of studies. Thicker lines indicate that more studies examined a given risk factor or outcome; thinner lines indicate fewer studies. SES, socioeconomic status; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SMM, severe maternal morbidity; ICU, intensive care unit; ED, emergency department.

Neerland. Determinants for Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Obstet Gynecol 2024.

Very few studies reported the excess risk attributable to a specific social–structural determinant of health. One study reported that, for pregnant women, income inequality was associated with a 14% increase in excess risk of death for Black pregnant women relative to White pregnant women in Virginia; prolonged income inequality was associated with a 20% increase.9 In one study, Hispanic birthing women were more likely to deliver at hospitals with higher risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity, contributing up to 37% of ethnic disparity in severe maternal morbidity in New York City.10 Another found an association between combined race and income segregation and increased severe maternal morbidity in birthing women in New York City; of the attributable risk, 35% was accounted for by delivery hospitals, and 50% by comorbidities (including prepregnancy body mass index [BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared], diabetes, hypertension, cardiac disease, renal disease, pulmonary disease, musculoskeletal disease, blood disorders, mental disorders, central nervous system disorders, rheumatic heart disease, anemia, and asthma).11 Finally, if rural Indigenous birthing women experienced severe maternal morbidity and mortality at the same rate as urban White women, they would see a 49% reduction in cases.12

We found one study that investigated patterns of intersecting social–structural determinants of health that is an exemplar of new approaches to risk factor research.13 The study, restricted to people without significant comorbidities before pregnancy, conducted a latent class analysis to identify six subgroups of people, or phenotypes, based on their interrelated social determinants of health. These six subgroups were then used to predict maternal health. Two subgroups in particular predicted worse scores of a composite postpartum maternal morbidity measure: young people living close to the federal poverty level with lower levels of educational attainment (subgroup 6) and people with limited English language proficiency who have lived in the United States for the shortest time (subgroup 2).

DISCUSSION

This systematic review sought to provide a broad overview of research that examined exposures related to social–structural determinants of health and at least one health or health care–related outcome affecting postpartum health.

Our review identified 118 studies categorized to nine outcome domains and 11 domains related to social–structural determinants of health representing 221 exposures of interest. A large proportion of studies examined depression and other mental health outcomes for both pregnant and birthing people, second only to mortality and other severe maternal morbidity outcomes.

Overall, study exposures broadly covered the social–structural determinants of health for pregnant and birthing people, partially addressing our two research questions. Included exposures represent only a subset of potential social–structural determinants that might affect the health and care of pregnant and birthing people, and no studies examined interdependencies with biological or medical risk factors. Limited depth and quality of research within each risk factor domain made it difficult to understand connections between social–structural determinants of health and maternal health outcomes. An unexpectedly large volume of research (relative to other domains of social structural determinants of health for pregnant people) addressed violence and trauma. Likely, this is, in part, because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention added violence-related questions to PRAMS (Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System).14

An overwhelming majority of studies (across all domains related to social–structural determinants of health) used correlational study designs. Fewer studies used analytic approaches (ie, experimental designs or quasi-experimental designs or analytic methods) that would allow for untangling causal relationships. Experimental studies were lacking because randomizing pregnant and birthing people to different levels of a social–structural determinant of health is unethical. Only a handful of studies used analytic methods to explore cause-and-effect relationships by using approaches such as propensity score methods, difference-in-difference, and instrumental variable methods. Even fewer studies attempted to break differences in a particular outcome into separate risk components for pregnant and birthing people who experience different levels of a social–structural determinant of health. Most of the studies that did use analytic methods that allow reporting the excess risk attributable to a specific exposure were conducted during the past 3 years, and our findings point to the need for more of this approach. Such increased rigor would help us better understand the potential mechanisms through which social determinants of health—including racism—work, and thereby design effective interventions.

We provided an evidence map of the research connecting racism and social determinants of health exposures to maternal health and morbidity. We focused on factors acting interpersonally to capture literature most likely to address this intersection. Such high-level mapping offers researchers a wider perspective on the breadth of literature within their area of practice and advocacy and helps to break down siloed approaches to research. Strengths of our report include a comprehensive search and inclusion of observational studies most relevant to the topic, high-level mapping of the research on social–structural determinants and outcome domains identified from the studies, and suggestions for new research.

This review does not address biomedical conditions as risk factors for maternal health. We excluded many studies that examined comorbidities and medical approaches as risk factors to inform the delivery of perinatal care. These excluded studies used patient demographics as control or confounder variables and lacked exposures indicative of social determinants of health. This siloed approach to risk factor research ignores the interdependencies, intersections, and feedback loops that can compound risks.

Our study should be considered in the context of several limitations. Our wide scope focused on quantitative epidemiologic studies and similar research, where publication bias remains possible, because papers with statistically significant results would be viewed as interesting to publish. Also, registering a protocol before conducting a secondary analysis of a data set remains uncommon. Included studies did not fit cleanly into discrete groups, which required us to categorize exposures subjectively. Likewise, the extreme heterogeneity in exposures and designs led to a subjective risk of bias assessment; however, we tested our approach by identifying the most rigorous study designs and analytic approaches for deeper assessments to confirm that subjecting the full literature set to formal assessment lacked value. Further, the included studies addressed only observed pregnancies.

Although each pregnant or birthing person will confront their own unique situation and risks, individuals can benefit when research identifies themes and patterns at the population level that suggest opportunities for strategy or treatment interventions to address social and structural determinants of health, not just social needs. Our review overall identified a large number of potentially eligible studies. However, even after narrowing the included literature to only the studies better designed to address our key questions, we remain unable to draw strong conclusions due to the study design, conduct, and dispersion reasons. Deeper investigation of an individual risk factor and its mechanisms would require more study designs than we were able to include here. Such a mixed-studies review would be best approached through targeted reviews of specific scope. Although studies within the past 3 years showed a definite trend toward improved rigor, much remains to be addressed. For complete recommendations for future research, and in concert with standards recently suggested for publishing research on racial health inequities,15 please refer to the AHRQ full systematic review and the companion NIH Pathways to Prevention Panel report (https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/maternal-morbidity-mortality/research; prevention.nih.gov/P2P-PostpartumHealth),16 where future research areas that could inform research, practice, and policy are outlined. This includes qualitative research, which fell outside of this review, but would be valuable to explore.

Identifying the risk factors faced by pregnant and birthing people is vitally important. Limited depth and quality of available research within each social–structural determinant of health impeded our ability to understand underlying mechanisms. The most recent studies demonstrate a definite trend toward improved rigor, but future research could emphasize techniques that improve the ability to estimate causal effects. Improved reporting in studies, along with organized and curated catalogs of maternal health exposures and their recognized mechanisms, could make it easier to examine exposures in the future. Longer term, future research needs data sets designed to more fully capture the data required to robustly examine racism and other social–structural determinants of health and their intersections with other biological or medical risk factors.

Footnotes

This work was supported under Contract No. 75Q80120D00008 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The National Institutes of Health funded the report.

Financial Disclosure Huda Bashir receives funding from African American Babies Coalition. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Presented at the National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Program workshop, “Identifying Risks and Interventions to Optimize Postpartum Health,” held virtually November 29, 2022–December 3, 2022.

The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors, who are responsible for its contents; the content does not necessarily represent the official views of or imply endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality retains a license to display, reproduce, and distribute the data and the report from which this manuscript were derived under the terms of the agency's contract with the author.

The authors thank the many partners from the following institutions for reviewing the report: the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; the National Institutes of Health Office of Disease Prevention; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; and the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities. The authors also thank Jeannine Ouellette for her editorial services.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal's requirements for authorship.

Peer reviews and author correspondence are available at http://links.lww.com/AOG/D539.

Figure.

No available caption

REFERENCES

- 1.Chinn JJ, Eisenberg E, Artis Dickerson S, King RB, Chakhtoura N, Lim IAL, et al. Maternal mortality in the United States: research gaps, opportunities, and priorities. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;223:486–92.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Ko JY, Farr SL, Tong VT, Bruce FC, et al. Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States: where are we now? J Womens Health 2014;23:3–9. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacDorman MF, Thoma M, Declcerq E, Howell EA. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal mortality in the United States using enhanced vital records, 2016‒2017. Am J Public Health 2021;111:1673–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews. Accessed January 24, 2023. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/collections/cer-methods-guide [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haddaway NR, Macura B, Whaley P, Pullin AS. ROSES Reporting Standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses: pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environ Evid 2018;7:7. doi: 10.1186/s13750-018-0121-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ROBINS-E Development Group, Higgins J, Morgan R, Rooney A, Taylor K, Thayer K, Silva R, et al. Risk of bias in non-randomized studies - of exposures (ROBINS-E). Launch version. Accessed July 10, 2022. https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/robins-e-tool [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geronimus AT. The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: evidence and speculations. Ethn Dis 1992;2:207–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kavanaugh VM, Fierro MF, Suttle DE, Heyl PS, Bendheim SH, Powell V. Psychosocial risk factors as contributors to pregnancy-associated death in Virginia, 1999-2001. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:1041–8. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Janevic T, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Severe maternal morbidity among Hispanic women in New York city: investigation of health disparities. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:285–94. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janevic T, Zeitlin J, Egorova N, Hebert PL, Balbierz A, Howell EA. Neighborhood racial and economic polarization, hospital of delivery, and severe maternal morbidity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39:768–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozhimannil KB, Interrante JD, Tofte AN, Admon LK. Severe maternal morbidity and mortality among Indigenous women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2020;135:294–300. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erickson EN, Carlson NS. Maternal morbidity predicted by an intersectional social determinants of health phenotype: a secondary analysis of the NuMoM2b dataset. Reprod Sci 2022;29:2013–29. doi: 10.1007/s43032-022-00913-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is PRAMS? Accessed January 26, 2023. www.cdc.gov/prams/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson KW, Terry MB, Braveman P, Reis PJ, Timmermans S, Epling JW, Jr. Maternal mortality: a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Panel report. Obstet Gynecol 2024;143:e78–e85. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]