Abstract

Background

Screening for cardiovascular disease is currently recommended before kidney transplantation. The present study aimed to validate the proposed algorithm by the American Heart Association (AHA‐2022) considering cardiovascular findings and outcomes in kidney transplant candidates, and to compare AHA‐2022 with the previous recommendation (AHA‐2012).

Methods and Results

We applied the 2 screening algorithms to an observational cohort of kidney transplant candidates (n=529) who were already extensively screened for coronary heart disease by referral to cardiac computed tomography between 2014 and 2019. The cohort was divided into 3 groups as per the AHA‐2022 algorithm, or into 2 groups as per AHA‐2012. Outcomes were degree of coronary heart disease, revascularization rate following screening, major adverse cardiovascular events, and all‐cause death. Using the AHA‐2022 algorithm, 69 (13%) patients were recommended for cardiology referral, 315 (60%) for cardiac screening, and 145 (27%) no further screening. More patients were recommended cardiology referral or screening compared with the AHA‐2012 (73% versus 53%; P<0.0001). Patients recommended cardiology referral or cardiac screening had a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (hazard ratio [HR], 5.5 [95% CI, 2.8–10.8]; and HR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.2–3.9]) and all‐cause death (HR, 12.0 [95% [CI, 4.6–31.4]; and HR, 5.3 [95% CI, 2.1–13.3]) compared with patients recommended no further screening, and were more often revascularized following initial screening (20% versus 7% versus 0.7%; P<0.001).

Conclusions

The AHA‐2022 algorithm allocates more patients for cardiac referral and screening compared with AHA‐2012. Furthermore, the AHA‐2022 algorithm effectively discriminates between kidney transplant candidates at high, intermediate, and low risk with respect to major adverse cardiovascular events and all‐cause death.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, kidney transplantation, revascularization, screening

Subject Categories: Computerized Tomography (CT), Cardiovascular Disease, Risk Factors

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AHA

American Heart Association

- ISCHEMIA‐CKD

International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness With Medical and Invasive Approaches–Chronic Kidney Disease

- MACE

major adverse cardiovascular event

- PKTC

potential kidney transplant candidate

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

The American Heart Association (AHA‐2022) algorithm refers more kidney transplant candidates for cardiac referral or cardiac screening compared with AHA‐2012.

The AHA‐2022 algorithm identifies kidney transplant candidates of highest risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and all‐cause death more specifically than AHA‐2012.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

The optimal pre‐ and posttransplant management of cardiovascular high‐risk patients remains to be established, but AHA‐2022 will identify patients who may benefit from specific attention to cardiovascular disease and patient‐centered medical and possible interventional therapies.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among kidney transplant recipients 1 , 2 ; hence, cardiovascular screening is currently recommended with the aim to identify potential kidney transplant candidates (PKTCs) (1) who may benefit from intensified cardioprotective interventions (medical or invasive) and (2) who may not benefit from transplantation due to a high risk of early, posttransplant, serious cardiovascular events.

In a new scientific consensus statement, 3 the American Heart Association (AHA) proposes a new approach (AHA‐2022) to cardiovascular screening before kidney transplantation in light of the ISCHEMIA‐CKD (International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness With Medical and Invasive Approaches–Chronic Kidney Disease) study. 4 The previous AHA screening recommendation (AHA‐2012) 5 was a practical guideline recommending screening of all patients with ≥3 risk factors. The AHA‐2022 algorithm proposes cardiology referral for PKTCs with known coronary heart disease (CHD), symptomatic cardiac disease, non‐CHD findings on echocardiography (eg, valve disease or pulmonary hypertension), or ejection fraction <40%. Based on the presence of at least 1 of an additional 4 risk criteria, the remaining PKTCs are divided into an intermediate‐risk group, which should undergo screening with noninvasive functional or anatomic testing, and a low‐risk group with no need for further cardiac screening.

Neither AHA‐2022 nor AHA‐2012 were prospectively evaluated before being published. Prior studies have evaluated the diagnostic and prognostic ability of risk factors with conflicting results. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 So far, evidence is lacking regarding the clinical consequence and impact on patients' management of the AHA‐2022 algorithm. To provide such external validation, we applied the AHA‐2022 algorithm to an observational cohort of PKTCs. The cohort was systematically referred to anatomic evaluation using cardiac computed tomography (CT), which allowed for evaluation of CHD in all PKTCs 10 and correlated findings with the classification according to both the AHA‐2022 and AHA‐2012 algorithms. In addition, we characterized the cohort with respect to the number of PKTCs undergoing revascularization after initial screening as well as risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and all‐cause death depending on the classification.

Methods

Study Design

In an observational cohort study design, all PKTCs aged >40 years, with diabetes or with need for dialysis >5 years, and who were referred for a kidney transplantation at Aarhus University Hospital, were included in the study. Aarhus University Hospital is a tertiary hospital and the only adult kidney transplantation facility for the Central Denmark and North Denmark regions. The population of the regions is ≈1.9 million.

PKTCs were identified through 3 sources as previously described. 10 The PKTCs were followed from the day of cardiovascular screening, which was performed between March 1, 2014, and September 30, 2019. End of follow‐up was December 31, 2021, or time of death. Central Denmark Region Committees on Health Research Ethics approved the data collection (3‐3013‐2724/1) without need for informed consent, as the research project could not have been conducted otherwise due to significant selection bias (eg, deceased patients).

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement was used as reporting guideline. 11 The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Cardiovascular Screening

The PKTCs were systematically referred to screening by cardiac CT, ECG, and echocardiography according to the regional screening protocol. Cardiac CT (coronary artery calcium score and coronary CT angiography) was the primary screening modality for obstructive CHD. Based on the referral and medical history (eg, known cardiovascular disease) or on a high coronary artery calcium score, some PKTCs were redirected by the cardiologist for invasive coronary angiography or functional imaging test instead of coronary CT angiography.

Coronary artery calcium score was determined using the Agatston method. 12 A diameter reduction of 50% to 100% denoted obstructive coronary artery disease, which was categorized as 1‐vessel, 2‐vessel, or 3‐vessel/left main artery disease.

Data Collection

Data were collected retrospectively from patient records and the Western Denmark Heart Registry. 13 CHD was defined as prior myocardial infarction and prior revascularization. 3 Nonchronic kidney disease–related risk factors for CHD included diabetes, cerebrovascular disease (stroke or transient ischemic attack), and peripheral artery disease (ankle pulse deficit, amputation due to ischemic disease, claudication, or nonhealing wounds). 3 Evidence of silent myocardial infarction was defined as a significant Q wave.

The outcomes were revascularization rate following initial cardiovascular screening, MACEs, and all‐cause death. Revascularization included percutaneous intervention and coronary artery bypass grafting. The indication for revascularization was either a perceived improved survival or relief of anginal symptoms. The revascularizations were performed according to standard clinical practice. MACEs were defined as cardiac death, cardiac arrest with successful resuscitation, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction, elective revascularization, stroke, and transient ischemic attack (see Data S1 for definitions).

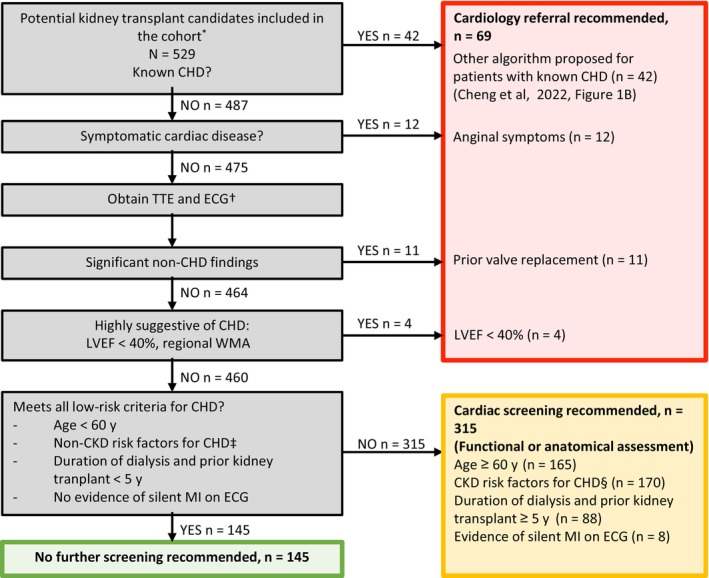

Classifications According to Algorithms

The proposed AHA‐2022 algorithm for kidney transplant candidates without known CHD (Cheng et al, 3 Figure 1) was applied to the cohort of PKTCs. In case data from echocardiography or ECG were not available, the results of these examinations were regarded as normal. The PKTCs were divided into 3 groups (Figure 1): (1) cardiology referral recommended; (2) cardiac screening recommended; and (3) no further screening recommended. All PKTCs with known CHD (n=42) were included in the group for cardiology referral.

Figure 1. Flowchart of AHA‐2022.

Algorithm from Cheng et al. 3 *Inclusion criteria included age >40 years, diabetes, or need for dialysis >5 years. †TTE or ECG results not available (n=192). Information on WMA was not available. ‡Diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral artery disease. CHD indicates coronary heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram; and WMA, wall motion abnormality.

For the AHA‐2012 algorithm, the PKTCs were divided into 2 groups on the basis of the number of cardiovascular risk factors: (1) screening recommended (≥3 risk factors) and (2) no screening recommended (<3 risk factors).

Statistical Analysis

Dichotomous data are presented as number (percentage). Continuous data are presented as mean±SD (if normally distributed) or median (interquartile range). McNemar's test for paired data was used to compare the number of PKTCs referred for cardiac evaluation using the AHA‐2022 compared with the AHA‐2012 algorithm. Outcomes are compared between groups using Pearson's chi‐squared test. Annual event rates are presented with 95% CIs. Unadjusted Cox regression was performed for time‐to‐first‐event analyses (MACEs and all‐cause death, respectively). Hazard ratios (HRs) are presented with 95% CIs and robust SE. All‐cause death was considered a competing risk for MACEs. The results were graphed using the Aalen–Johansen method for MACEs to account for all‐cause death as a competing risk and Kaplan–Meier analysis for all‐cause death with up to 5 years of follow‐up. Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) and Microsoft Excel for Mac version 16.72 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) were used for statistical analyses and figures.

Results

Need for Cardiac Evaluation

A total of 529 PKTCs were included in the cohort, which was divided into 3 groups using the proposed AHA‐2022 algorithm (Figure 1). An indication for cardiac referral was identified in 69 (13%) PKTCs using the AHA‐2022 algorithm on the basis of known CHD or suspicion thereof (Figure 1). Of the remaining PKTCs, 315 (60%) were categorized as intermediate risk with need for cardiac screening while 145 (27%) met the low‐risk criteria for CHD needing no further cardiac testing (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of the 3 groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Potential Kidney Transplant Candidates Divided in 3 Groups

| Patient characteristics (n=529) | AHA‐2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology referral recommended n=69 | Cardiac screening recommended n=315 | No further screening recommended n=145 | |

| Sex, male | 56 (81) | 202 (64) | 89 (61) |

| Age, y | 59±9 | 58±12 | 48±8 |

| Dialysis treatment | |||

| Hemodialysis | 19 (28) | 74 (23) | 22 (15) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 7 (10) | 34 (11) | 12 (8) |

| Hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Preemptive | 43 (62) | 206 (66) | 111 (77) |

| eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2)* | 12 (11–15) | 12 (9–15) | 13 (10–15) |

| Previous kidney transplantation | 11 (16) | 74 (23) | 7 (5) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Age >60 y | 35 (51) | 165 (52) | 0 |

| Diabetes | 27 (39) | 121 (38) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 66 (96) | 284 (90) | 127 (88) |

| Dyslipidemia | 53 (77) | 156 (50) | 41 (28) |

| Smoking, active | 25 (36) | 67 (21) | 33 (23) |

| Dialysis treatment >1 y | 20 (29) | 88 (28) | 13 (9) |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 6 (9) | 17 (5) | 5 (3) |

| Prior cardiovascular disease | 53 (77) | 53 (17) | 0 |

| Number of cardiovascular risk factors | 4 (4–5) | 3 (2–4) | 1 (1–2) |

| Number of patients with ≥3 risk factors | 61 (88) | 208 (66) | 14 (10) |

Values are presented as n (%), mean±SD, or median (interquartile range). AHA indicates American Heart Association; and eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Only preemptive patients (4 samples missing).

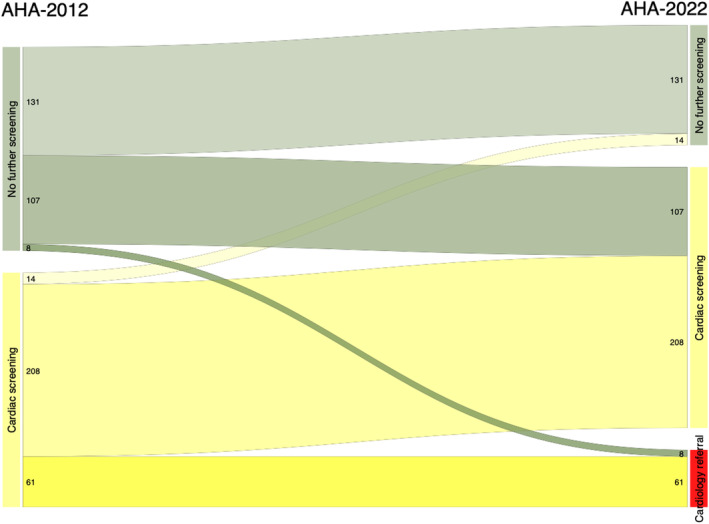

In total, based on the AHA‐2022 algorithm, 73% of the PKTCs were recommended cardiology referral or cardiac screening. Based on the AHA‐2012 algorithm, only 53% of PKTCs with ≥3 risk factors were recommended for screening. 5 Thus, the AHA‐2022 algorithm increases the number of PKTCs referred for cardiac investigation (P<0.0001) (Figure 2). The proportion of patients with ≥3 risk factors was 66% among those recommended for cardiac screening by the AHA‐2022 algorithm and 10% among those recommended no further screening.

Figure 2. Need for cardiac evaluation.

Sankey diagram showing the need for cardiac evaluation according to AHA‐2012 (53%) and AHA‐2022 (73%). AHA indicates American Heart Association.

Differences in Classification

Almost half (n=115) of the PKTCs who were not recommended for screening by the AHA‐2012 algorithm were reclassified with a recommendation for referral (n=8) or screening (n=107) by the AHA‐2022 algorithm (Figure 2). In contrast, only 14 PKTCs recommended for screening by the AHA‐2012 algorithm were reclassified as “screening not recommended” by the AHA‐2022 algorithm. The baseline characteristics and outcomes of PKTCs depending on the reclassification are shown in Table S1. Among the PKTCs reclassified with a recommendation for cardiology referral or cardiac screening by the AHA‐2022 algorithm, the initial revascularization in relation to the screening rate was 6%.

Results of Cardiac CT

Due to the systematic screening of all PKTCs, a cardiac CT was performed in 142 (98%) of PKTCs not recommended for screening by the AHA‐2022 algorithm and in 290 (92%) recommended for screening (Table 2). In PKTCs not eligible for cardiac CT, alternative screening modalities were performed (Table 2). The number of PKTCs with a coronary artery calcium score ≥400 was higher among PKTCs classified as recommended for cardiac screening when compared with PKTCs recommended for no further screening (35% versus 7%). Similarly, more PKTCs recommended for cardiac screening had multivessel coronary artery disease when compared with PKTCs recommended for no further screening (32% versus 9%).

Table 2.

Imaging Characteristics of Coronary Artery Calcium Score and Coronary CTA

| Imaging characteristics | AHA‐2022 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology referral recommended n=69 | Cardiac screening recommended n=315 | No further screening recommended n=145 | P value | |

| Cardiac CT performed | n=41 (59) | n=290 (92) | n=142 (98) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery calcium score | n=38 (55) | n=270* (85) | n=130 (90) | |

| Coronary artery calcium score | 547 (55–1780) | 196 (55–746) | 0 (0–38) | <0.001 |

| 0 | 3 (8) | 46 (17) | 79 (61) | |

| >0 and <400 | 14 (37) | 129 (48) | 42 (32) | |

| ≥400 | 21 (55) | 94 (35) | 9 (7) | <0.001 |

| Coronary CTA † | 27 (39) | 247 (78) | 137 (94) | |

| 1‐vessel disease | 6 (15) | 41 (17) | 14 (10) | |

| 2‐vessel disease | 6 (15) | 46 (19) | 6 (4) | |

| 3‐vessel or left main disease | 6 (15) | 33 (13) | 7 (5) | <0.001 |

| ICA (no cardiac CT performed)†,‡ | 19§ (28) | 16 (5) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| 1‐vessel disease | 8 (42) | 1 (6) | NA | |

| 2‐vessel disease | 2 (11) | 2 (13) | NA | |

| 3‐vessel or left main disease | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | NA | 0.25 |

| MPI (no cardiac CT or ICA performed) | 2§ (3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0.07 |

| Perfusion defect | 1 | 0 | NA | NA |

| No cardiac screening performed | 7 (10) | 7 (2) | 3 (2) | |

| Recently performed ICA/MPI | 7 (100) | 5 (71) | 3 (100) | NA |

Values are presented as n (%) or median [interquartile range].

AHA indicates American Heart Association; CACS, coronary artery calcium score; CT, computed tomography; CTA, computed tomographic angiography; ICA, invasive coronary angiography; MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging; NA, not applicable; PKTC, potential kidney transplant candidate.

1 PKTC's CACS was not analyzed.

Significant stenoses ≥50%.

Prior revascularization is not counted as vessel disease.

Two PKTCs underwent both ICA and MPI.

Revascularization Following Initial Screening

The revascularization rate following screening was higher in PKTCs recommended for cardiology referral or cardiac screening by the AHA‐2022 algorithm compared with PKTCs not recommended for screening (20%, 7%, and 0.7%, respectively; P<0.001; Table 3). Similarly, when using the AHA‐2012 algorithm, the revascularization rate was higher in PKTCs recommended for cardiac screening when compared with PKTCs recommended for no further screening (10% versus 3%; P<0.001; Table 3). The indications for revascularization were not different between groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Invasive Coronary Angiography and Revascularization

| AHA‐2022 | AHA‐2012 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology referral recommended (n=69) | Cardiac screening recommended (n=315) | No further screening recommended (n=145) | P value | Screening recommended (n=283) | Screening not recommended (n=246) | P value | |

| Invasive coronary angiography performed | 39 (57) | 113 (36) | 12 (8) | <0.001 | 124 (44) | 40 (16) | <0.001 |

| PCI performed | 13 (19) | 20 (6) | 1 (0.7) | <0.001 | 26 (9) | 8 (3) | 0.01 |

| Prognostic indication | 12 (17) | 18 (6) | 1 (0.7) | 24 (8) | 7 (3) | ||

| Left main artery disease | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 0 | ||

| 3‐vessel disease | 2 (3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 4 (1) | 0 | ||

| 2‐vessel disease including proximal LAD | 7 (10) | 9 (3) | 1 (0.7) | 13 (5) | 4 (2) | ||

| Other | 3 (4) | 6 (2) | 0 | 6 (2) | 3 (1) | ||

| Symptomatic indication | 1 (1) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| CABG performed | 1 (1) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0.26 | 2 (0.7) | 0 | 0.19 |

| Revascularization rate | 14 (20) | 21 (7) | 1 (0.7) | <0.001 | 28 (10) | 8 (3) | <0.001 |

Number of invasive coronary angiographies and revascularizations performed. Results are presented in groups for both the AHA‐2022 algorithm and AHA‐2012 algorithm. Values are presented as n (%).

AHA indicates American Heart Association; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; LAD, left artery disease; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

MACEs and All‐Cause Death

During a median follow‐up period of 4.7 years, the risk of MACEs was higher among PKTCs recommended for cardiology referral by the AHA‐2022 algorithm when compared with PKTCs recommend for cardiac screening or for no further screening (annual event rates of 10.2% [6.8–15.2], 4.0% [3.1–5.2], and 1.9% [1.1–3.3], respectively; Figure 3). Similar results were observed with respect to all‐cause death (annual event rates of 8.5% [5.7–12.7], 3.8% [2.9–4.9], and 0.7% [0.3–1.7], respectively; Figure 3). The AHA‐2012 ≥3 risk factors were also associated with both MACEs (HR, 2.09 [95% CI, 1.35–3.23]) and all‐cause death (HR, 4.44 [95% CI, 2.54–7.76]) as previously reported. 10

Figure 3. Risk of MACEs and all‐cause death.

Time‐to‐event analyses for (A) MACEs and (B) all‐cause death. Illustrated are unadjusted HRs, CIs, and SE. Red: Cardiology referral recommended. Orange: Cardiac screening recommended. Green: No further screening recommended. HRs indicates hazard ratios; and MACEs, major adverse cardiovascular events.

Discussion

Among PKTCs in this study, more patients would be recommended for referral to a cardiologist or cardiac screening when applying the proposed AHA‐2022 algorithm compared with the previous AHA‐2012 algorithm. 5 Based on the subsequent risk of MACEs and all‐cause death, the AHA‐2022 algorithm is able to discriminate PKTCs into a higher‐risk subpopulation recommended for cardiology referral, an intermediate‐risk subpopulation recommended for cardiac screening, and a lower‐risk subpopulation not recommended any further screening. Thus, the AHA‐2022 algorithm allows for identification of PKTCs who may also have a greater awareness with respect to cardiovascular symptoms and follow‐up. Whether such classification by screening will translate into better outcomes, however, remains to be established, as to date no studies have documented improvement in MACE outcomes following intensified screening in PKTCs. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17

Classification by the AHA‐2012 algorithm by ≥3 risk factors was also associated with both MACEs and all‐cause death. 10 This extends findings from a prior prospective study including a smaller cohort (n=154) of PKTCs from February 2011 to February 2014 showing that ≥3 risk factors were associated with increased risk of all‐cause death but not MACEs. 7 , 8

Using the AHA‐2022 algorithm, the PKTCs in the cardiology referral group were much more likely to undergo revascularization (of which >90% were performed on the basis of a presumed prognostic benefit) following cardiac screening, when compared with the subpopulation recommended no further screening. In comparison, the difference in revascularization rates was much smaller between the groups using the AHA‐2012 algorithm. The AHA‐2022 algorithm highlights cardiology referral for PKTCs with known CHD or suspicion thereof, whereas the previous recommendation was less specific, with an arbitrary cutoff at 3 risk factors for need for cardiovascular screening before kidney transplantation. 5

The clinical benefits and consequences of pretransplantation cardiovascular screening in asymptomatic patients remain controversial. 15 , 18 , 19 Our study design does not allow any conclusion as to whether the screening or the revascularization provided benefit with respect to outcomes or whether optimized medical management may have offered similar or better benefits to revascularization. The ISCHEMIA‐CKD trial showed no effect of revascularization compared with optimized medical management alone among patients with chronic kidney disease and moderate or severe myocardial perfusion defects on noninvasive functional imaging test. 4 A post hoc analysis on patients waitlisted for kidney transplantation revealed similar findings. 20 Thus, with the available evidence, revascularization is currently not indicated in asymptomatic patients and carries a risk of both side effects and delay of transplantation. 21 In our observational study, some asymptomatic patients were revascularized. The impact on outcome with respect to MACEs or all‐cause death is unknown.

In addition to revascularization or intensified medical management, cardiac screening could also assist the assessment of kidney transplant eligibility on the basis of the risk of MACEs and all‐cause death in combination with other known comorbidities.

The strengths of the study include the wide inclusion criteria and systematic screening by cardiac imaging of a large proportion of PKTCs, which allowed us to assess the degree of CHD among all patients independent of the classification using the AHA‐2022 or AHA 2012 algorithms, including 47% with <3 risk factors. A limitation is the exclusion of PKTCs aged ≤40 years, without diabetes, or dialysis for ≤5 years, as they were not referred to cardiac CT. This would presumably constitute a low‐risk group, and thus, the number of patients recommend for no further screening would be larger if all PKTCs were included. Also, some PKTCs in the “no further screening” group may have been wrongly allocated due to missing data on ECG and echocardiography (31% and 12% of all PKTCs, respectively), which may have increased the risk of MACEs and all‐cause death in that group.

In conclusion, the proposed AHA‐2022 algorithm resulted in a greater proportion of PKTCs being recommended for cardiology referral or cardiac screening compared with the previous AHA recommendation (AHA‐2012). The algorithm provides a good discrimination between PKTCs at higher, intermediate, and lower risk with respect to MACEs and all‐cause death. The PKTCs recommended no further screening had a low revascularization rate and low risk of MACEs and all‐cause death.

Sources of Funding

Dr Nielsen received financial support from Aarhus University and Augustinus Foundation.

Disclosures

Dr Birn has received a research grant from Glaxo Smith Kline and Vifor Pharma (paid to institution) and has received consulting fees or speaker honoraria from Vifor Pharma, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Galapagos, Alexion, MSD, and Novo Nordisk, as well as support for attending meetings from Novartis and AstraZeneca. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Data S1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the head consultants of collaborating departments for data transmission: Birgitte Bang Pedersen, Aalborg University Hospital; Henning Danielsen, Regional Hospital Central Jutland; and Nikolai Hoffmann‐Petersen, Regional Hospital West Jutland. Furthermore, the authors thank Malene Stoltenberg Iversen, Amal Derai, and Rasmus Laursen for help with data collection, and cardiologist Lone Andersen for providing feedback on the manuscript.

This manuscript was sent to Kori S. Zachrison, MD, MSc, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.031150

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 8.

References

- 1. Meier‐Kriesche H‐U, Schold JD, Srinivas TR, Reed A, Kaplan B. Kidney transplantation halts cardiovascular disease progression in patients with end‐stage renal disease. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1662–1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00573.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gill JS, Ma I, Landsberg D, Johnson N, Levin A. Cardiovascular events and investigation in patients who are awaiting cadaveric kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:808–816. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheng XS, VanWagner LB, Costa SP, Axelrod DA, Bangalore S, Norman SPA, Herzog C, Lentine KL. Emerging evidence on coronary heart disease screening in kidney and liver transplantation candidates: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;146:e299–e324. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bangalore S, Maron DJ, O'Brien SM, Fleg JL, Kretov EI, Briguori C, Kaul U, Reynolds HR, Mazurek T, Sidhu MS, et al. Management of Coronary Disease in patients with advanced kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lentine KL, Costa SP, Weir MR, Robb JF, Fleisher LA, Kasiske BL, Carithers RL, Ragosta M, Bolton K, Auerbach AD, et al. Cardiac disease evaluation and management among kidney and liver transplantation candidates. Circulation. 2012;126:617–663. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823eb07a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lindley EM, Hall AK, Hess J, Abraham J, Smith B, Hopkins PN, Shihab F, Welt F, Owan T, Fang JC. Cardiovascular risk assessment and management in prerenal transplantation candidates. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Winther S, Svensson M, Jørgensen HS, Rasmussen LD, Holm NR, Gormsen LC, Bouchelouche K, Bøtker HE, Ivarsen P, Bøttcher M. Prognostic value of risk factors, calcium score, coronary CTA, myocardial perfusion imaging, and invasive coronary angiography in kidney transplantation candidates. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:842–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Winther S, Svensson M, Jørgensen HS, Bouchelouche K, Gormsen LC, Pedersen BB, Holm NR, Bøtker HE, Ivarsen P, Bøttcher M. Diagnostic performance of coronary ct angiography and myocardial perfusion imaging in kidney transplantation candidates. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Doukky R, Fughhi I, Campagnoli T, Wassouf M, Kharouta M, Vij A, Anokwute C, Appis A, Ali A. Validation of a clinical pathway to assess asymptomatic renal transplant candidates using myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2018;25:2058–2068. doi: 10.1007/s12350-017-0901-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nielsen MB, Dahl JN, Laursen R, Jespersen B, Ivarsen PR, Winther S, Birn H. In a real‐life setting, risk factors, coronary artery calcium score and coronary stenosis at computed tomography angiography are associated with MACE and all‐cause mortality among kidney transplant candidates. Am J Transplant. 2023;23:1194–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.ajt.2023.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Detrano R, Beach M, Beach L. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schmidt M, Maeng M, Madsen M, Sørensen HT, Jensen LO, Jakobsen CJ. The Western Denmark heart registry: its influence on cardiovascular patient care. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1259–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nimmo A, Forsyth JL, Oniscu GC, Robb M, Watson C, Fotheringham J, Roderick PJ, Ravanan R, Taylor DM. A propensity score–matched analysis indicates screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease does not predict cardiac events in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2021;99:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deak AT, Ionita F, Kirsch AH, Odler B, Rainer PP, Kramar R, Kubatzki MP, Eberhard K, Berghold A, Rosenkranz AR. Impact of cardiovascular risk stratification strategies in kidney transplantation over time. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:1810–1818. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheng XS, Liu S, Han J, Stedman MR, Baiocchi M, Tan JC, Chertow GM, Fearon WF. Association of pretransplant coronary heart disease testing with early kidney transplant outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183:134–141. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dunn T, Saeed MJ, Shpigel A, Novak E, Alhamad T, Stwalley D, Rich MW, Brown DL. The association of preoperative cardiac stress testing with 30‐day death and myocardial infarction among patients undergoing kidney transplantation. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0211161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sharif A. Routine cardiac stress testing in potential kidney transplant candidates is only appropriate in symptomatic individuals: PRO. Kidney360. 2022;3:2008–2012. doi: 10.34067/KID.0007592020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hu J‐R, Sugeng L. Routine cardiac stress testing in kidney transplant candidates is only appropriate in symptomatic individuals: CON. Kidney360. 2022;3:2013–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Herzog CA, Simegn MA, Xu Y, Costa SP, Mathew RO, El‐Hajjar MC, Gulati S, Maldonado RA, Daugas E, Madero M, et al. Kidney transplant list status and outcomes in the ISCHEMIA‐CKD trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:348–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Halvorsen S, Mehilli J, Cassese S, Hall TS, Abdelhamid M, Barbato E, De Hert S, de Laval I, Geisler T, Hinterbuchner L, et al. 2022 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular assessment and management of patients undergoing non‐cardiac surgery. Developed by the task force for cardiovascular assessment and management of patients undergoing non‐cardiac surgery of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3826–3924. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.