Abstract

Objective

To assess the prevalence and clinical correlates of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) identified by computed tomography (CT) in the general population compared with ultrasonography (US).

Methods

Four hundred and fifty-eight subjects who received health checkups at Meijo Hospital in 2021 and underwent CT within a year of US in the past decade were analyzed. The mean age was 52.3±10.1 years old, and 304 were men.

Results

NAFLD was diagnosed in 20.3% by CT and in 40.4% by the US. The NAFLD prevalence in men was considerably greater in subjects 40-59 years old than in those ≤39 years old and in those ≥60 years old by both CT and US. The NAFLD prevalence in women was substantially higher in the subjects 50-59 years old than in those ≤49 years old or those ≥60 years old on US, while no significant differences were observed on CT. The abdominal circumference, hemoglobin value, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, albumin level, and diabetes mellitus were independent predictors of NAFLD diagnosed by CT. The body mass index, abdominal circumference, and triglyceride level were independent predictors of NAFLD diagnosed by the US.

Conclusion

NAFLD was found in 20.3% of CT cases and 40.4% of US cases among recipients of health checkups. An “inverted U curve” in which the NAFLD prevalence rose with age and dropped in late adulthood was reported. NAFLD was associated with obesity, the lipid profile, diabetes mellitus, hemoglobin values, and albumin levels. Our research is the first in the world to compare the NAFLD prevalence in the general population simultaneously by CT and US.

Keywords: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, computed tomography, ultrasonography, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a primary cause of liver disease globally and develops non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (1,2). NAFLD is diagnosed by the presence of fatty liver (FL) without secondary causes, including significant alcohol consumption, prolonged use of a steatogenic medication, or monogenic hereditary disorders. The global prevalence of NAFLD is 25% and varies geographically from 13% in Africa to 32% in the Middle East (3).

Ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) are employed for the detection of NAFLD, and the NAFLD prevalence is influenced by these techniques (4,5). US is the most extensively accessible and most commonly used for analyzing NAFLD prevalence in the general population. In Japan, the NAFLD prevalence in the general population detected by US was stated to be 25-57% (6-13). However, there have been no reports of NAFLD prevalence detected by CT in the general population, although an NAFLD prevalence of 10-22% on CT has been reported for the general populations of other countries (14-18).

To our knowledge, no studies have examined the NAFLD prevalence in the general population by both CT and US simultaneously. We therefore assessed the NAFLD prevalence by both CT and US among attendees of health checkups at our hospital to clarify the advantages of the two methods. Furthermore, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) has recently been proposed as a term to describe FL associated with known metabolic dysfunction (19,20). We therefore also determined the prevalence and clinical correlates of MAFLD.

Materials and Methods

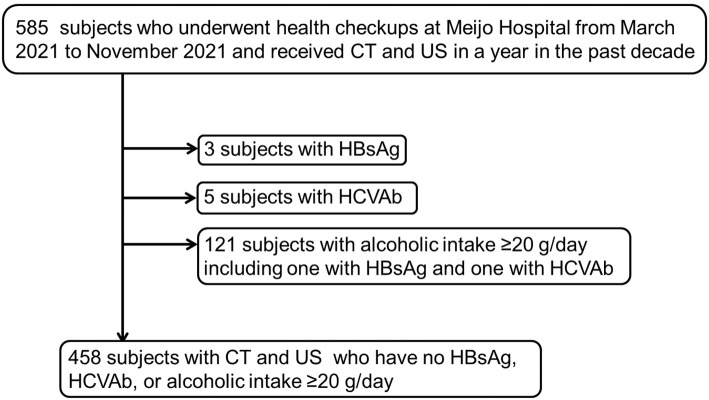

Among the health checkup participants at Meijo Hospital from March to November 2021, 585 had received CT within 1 year of US in the past decade. Three participants with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), 5 with hepatitis C virus antibody (HCVAb), and 121 with an alcoholic intake ≥20 g/day (1 with HBsAg and 1 with HCVAb) were excluded. Four hundred and fifty-eight subjects with CT and US who had no HBsAg, HCVAb, or alcoholic intake ≥20 g/day were thus incorporated in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of subject selection. Among the participants who underwent health checkups at our hospital from March to November 2021, 585 subjects had undergone CT within 1 year of US in the past decade. Three participants with HBsAg, 5 with HCVAb, and 121 with alcoholic intake ≥20 g/day (1 with HBsAg and 1 with HCVAb) were excluded. In the study, 458 individuals with CT and US who did not have HBsAg or HCVAb or consume ≥20 g of alcohol per day were included. CT: computed tomography, HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen, HCVAb: hepatitis C virus antibody, US: ultrasonography

The research was performed following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federation of National Public Service Personnel Mutual Aid Associations Meijo Hospital (Approval No. 185). Because the data were analyzed anonymously using stored information in the hospital database, the need for written informed consent was waived.

Abdominal CT examinations

Non-enhanced CT was conducted using either a 16-section multidetector scanner (Aquilion 16; Canon Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan), a 64-section multidetector scanner (Aquilion 64; Canon Medical Systems), or an 80-section multidetector scanner (Aquilion Prime SP/iEdition; Canon Medical Systems). CT was carried out for screening tests of lung cancer in 243 participants at health checkups, for the close evaluation of abnormal outcomes at health checkups in 191 participants, and for the assessment of symptoms in the abdomen or chest in 24 participants. Nine and three regions of interest were placed at the liver or spleen, respectively, to avoid macroscopic vessels. The median hepatic or splenic attenuation values were obtained, and “hepatic attenuation minus splenic attenuation (CTL−-S) ≤1 Hounsfield unit” was considered FL (21).

Detection of FL by US

A group of trained technicians and hepatologists performed US and diagnosed FL using an ARIETTA 65 ultrasound device (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), an Aplio MX ultrasound device (Toshiba Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan), and Aplio300 and a450 ultrasound devices (Canon Medical Systems). FL was diagnosed and graded following guidelines for the ultrasonic diagnosis of FL by the Japan Society of Ultrasonics in Medicine (22). Semiquantitative grades are labeled as 0-3 (with 0 being normal). Grade 1 is denoted by only bright liver (liver-to-kidney contrast). Grade 2 is denoted by bright liver with either vessel blurring or deep attenuation. Grade 3 is denoted by bright liver with both vessel blurring and deep attenuation.

Statistical analyses

The differences in continuous variables between the two groups were analyzed by Student's t-test. The chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was employed to compare categorical data. Multiple logistic regression was conducted to identify the independent factors linked to the presence of NAFLD or MAFLD. p values <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were conducted with the StatFlex software program, version 6.0 for Windows (StatFlex, Osaka, Japan).

Results

NAFLD prevalence

Using CT and US, 93 (20.3%) and 185 (40.4%) of 458 subjects were diagnosed with NAFLD, respectively (Table 1). Based on the grade of FL diagnosed by US, 92 (20.1%) had mild FL, 66 (14.4%) had moderate FL, and 27 (5.9%) had severe FL.

Table 1.

Demographics of Subjects.

| Variables | All (n=458) | Fatty liver detected by CT (n=93) | Non-fatty liver detected by CT (n=365) | p value | Fatty liver detected by US (n=185) | Non-fatty liver detected by US (n=273) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Male/Female) | 304/154 | 81/12 | 223/142 | <0.001 | 141/44 | 163/110 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 52.3±10.1 | 52.0±8.7 | 52.4±10.5 | ns | 52.4±8.9 | 52.3±10.9 | ns |

| Height (cm) | 165.5±8.7 | 168.1±7.5 | 164.8±8.9 | 0.001 | 167.1±8.5 | 164.4±8.7 | 0.001 |

| Body weight (kg) | 63.7±13.2 | 75.4±13.5 | 60.7±11.3 | <0.001 | 71.3±13.4 | 58.5±10.3 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.1±3.8 | 26.6±4.2 | 22.2±3.1 | <0.001 | 25.4±3.9 | 21.5±2.8 | <0.001 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 83.0±10.4 | 93.0±10.4 | 80.5±8.8 | <0.001 | 89.4±10.5 | 78.7±7.9 | <0.001 |

| White blood cells (/μL) | 5,207±1,356 | 5,954±1,451 | 5,017±1,265 | <0.001 | 5,658±1,368 | 4,901±1,262 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.3±1.4 | 15.3±1.09 | 14.1±1.4 | <0.001 | 14.6±1.5 | 14.1±1.3 | <0.001 |

| Platelets (104/μL) | 23.1±6.0 | 23.4±6.2 | 23.0±6.0 | ns | 24.0±7.0 | 22.4±5.1 | 0.003 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.39±0.27 | 4.45±0.28 | 4.38±0.27 | 0.013 | 4.40±0.29 | 4.39±0.26 | ns |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.02±0.39 | 1.06±0.38 | 1.01±0.39 | ns | 1.00±0.41 | 1.02±0.38 | ns |

| ALP (U/L) | 156.6±79.4 | 161.1±76.4 | 155.3±80.3 | ns | 155.6±75.8 | 157.3±81.9 | ns |

| AST (U/L) | 23.2±10.2 | 32.0±16.8 | 21.0±5.8 | <0.001 | 26.6±13.5 | 20.9±6.1 | <0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 25.6±19.9 | 47.3±30.5 | 20.1±10.5 | <0.001 | 34.9±26.4 | 19.4±9.8 | <0.001 |

| GGT (U/L) | 33.5±29.3 | 49.8±39.1 | 29.3±24.6 | <0.001 | 43.2±35.2 | 26.9±22.2 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.83±0.19 | 0.89±0.19 | 0.81±0.18 | <0.001 | 0.86±0.18 | 0.81±0.19 | 0.011 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 72.6±15.0 | 71.5±16.0 | 72.9±14.8 | ns | 71.9±15.2 | 73.0±14.9 | ns |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 207±33 | 205±36 | 208±32 | ns | 209±36 | 206±31 | ns |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 65±18 | 53±12 | 69±18 | <0.001 | 57±15 | 71±18 | <0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 104±67 | 150±95 | 93±51 | <0.001 | 134±81 | 84±45 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 126±29 | 130±32 | 125±28 | ns | 132±31 | 122±26 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.7±0.7 | 6.1±0.8 | 5.6±0.6 | <0.001 | 5.9±0.9 | 5.6±0.4 | <0.001 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 102±19 | 110±24 | 100±16 | <0.001 | 107±23 | 99±14 | <0.001 |

| FIB-4 index | 1.20±0.56 | 1.18±0.69 | 1.20±0.52 | ns | 1.14±0.57 | 1.24±0.54 | 0.047 |

| Cerebrovascular accident (%) | 15 (3.3%) | 4 (4.3) | 11 (3.0) | ns | 4 (2.2) | 11 (4.1) | ns |

| Cardiovascular disease (%) | 13 (2.8) | 3 (3.2) | 10 (2.7) | ns | 2 (1.1) | 11 (4.0) | 0.062 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 74 (16.2) | 32 (34.4) | 42 (11.5) | <0.001 | 46 (24.9) | 28 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 79 (17.2) | 27 (29.0) | 52 (14.2) | <0.001 | 40 (21.6) | 39 (14.3) | 0.041 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 30 (6.6) | 16 (17.2) | 14 (3.8) | <0.001 | 20 (10.8) | 10 (3.7) | 0.002 |

| Malignant neoplasm (%) | 32 (7.0) | 7 (7.5) | 25 (6.8) | ns | 11 (5.9) | 21 (7.7) | ns |

| Smoking (%) | 62 (13.5) | 17 (18.3) | 45 (12.3) | ns | 34 (18.4) | 28 (10.3) | 0.013 |

| US grade of fatty liver (0/1/2/3) | 273/92/66/27 | 7/21/39/26 | 266/71/27/1 | <0.001 | |||

| Hepatic attenuation of CT | 57.1±12.3 | 38.4±13.8 | 61.9±5.3 | <0.001 | 49.1±15.0 | 62.6±5.1 | <0.001 |

| Splenic attenuation of CT | 50.9±4.2 | 51.3±5.0 | 50.8±3.9 | ns | 50.4±4.4 | 51.3±4.0 | 0.019 |

| CTL-S | 6.2±12.2 | -13.0±13.1 | 11.1±5.0 | <0.001 | -1.3±15.3 | 11.3±5.1 | <0.001 |

| Fatty liver detected by CT | 93 (20.3) | 86 (46.5) | 7 (2.6) | <0.001 | |||

| Interval between CT and US (months) | 1.6±2.8 | 1.3±2.9 | 1.7±2.8 | ns | 1.7±2.9 | 1.5±2.7 | ns |

Values are expessed as mean±SD. Statistical analysis are conducted using the chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test, or Student's t test. ALP: alkaline phosphatase, ALT: alanin aminotransferase, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, BMI: body mass index, CT: computed tomography, CTL-S: hepatic attenuation minus splenic attenuation of computed tomography, eGFR: estimated glomelular filtration rate, GGT: gamma glutamyl transpeptidase, FIB-4 index: fibrosis-4 index, HDL cholesterol: high density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL cholesterol: low density lipoprotein cholesterol, US: ultrasonography

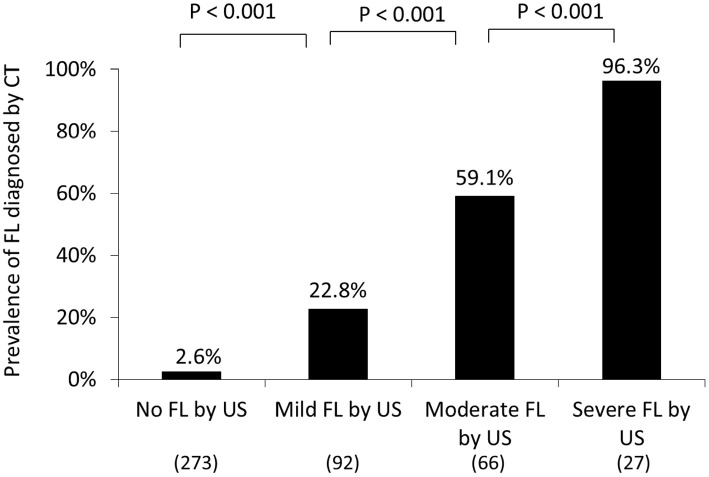

The association between FL diagnosed by US and CT was evaluated (Fig. 2). Among the subjects diagnosed by US with no, mild, moderate, and severe FL, FL was detected by CT in 7 of 273 (2.6%), 21 of 92 (22.8%), 39 of 66 (59.1%), and 26 of 27 (96.3%), respectively. The occurrence of FL diagnosed by CT was thus significantly greater in the subjects with more severe FL than in those with more mild FL diagnosed by US (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

The association between FL diagnosed by US and CT. Among the subjects diagnosed by US with no, mild, moderate, and severe FL, FL was identified by CT in 7 of 273 (2.6%), 21 of 92 (22.8%), 39 of 66 (59.1%), and 26 of 27 (96.3%), respectively. The prevalence of FL identified by CT was considerably higher in the subjects with more severe FL than in those with more mild FL diagnosed by US (p<0.001). CT: computed tomography, FL: fatty liver, US: ultrasonography

Association of NAFLD diagnosed by CT with gender and age

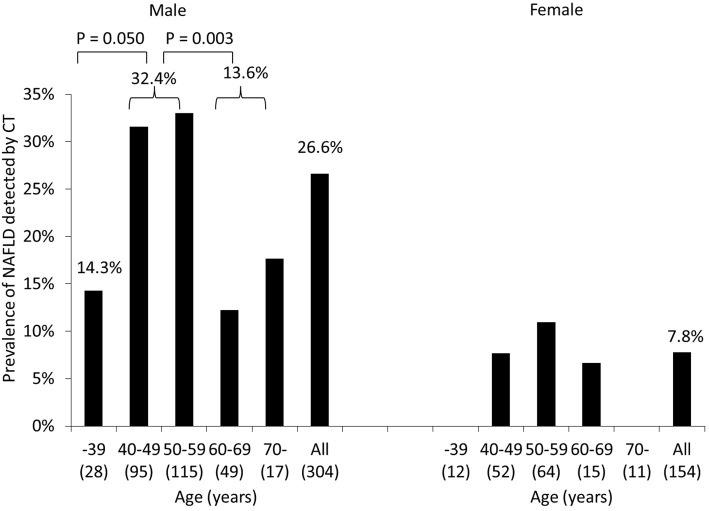

The NAFLD prevalence determined by CT was significantly higher in men (26.6%) than in women (7.8%) (p<0.001) (Table 1, Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of NAFLD diagnosed by CT in groups stratified by gender and age. The NAFLD prevalence was significantly higher in men (26.6%) than in women (7.8%) (p<0.001). The NAFLD prevalence in men tended to be or was considerably higher in the subjects 40-59 years old than in those ≤39 or ≥60 years old (p=0.050 and p=0.003). Age categories did not significantly affect the prevalence of NAFLD in women. CT: computed tomography, NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

There was no marked difference in the mean age between subjects with and without NAFLD diagnosed by CT (Table 1). However, when stratified by gender and age, the NAFLD prevalence in men tended to be or was significantly higher in the subjects 40-59 years old (32.4%) than in those ≤39 years old (14.3%, p=0.050) and those ≥60 years old (13.6%, p=0.003) (Fig. 3). The NAFLD prevalence by CT did not significantly differ among age groups in women.

Association of NAFLD diagnosed by US with gender and age

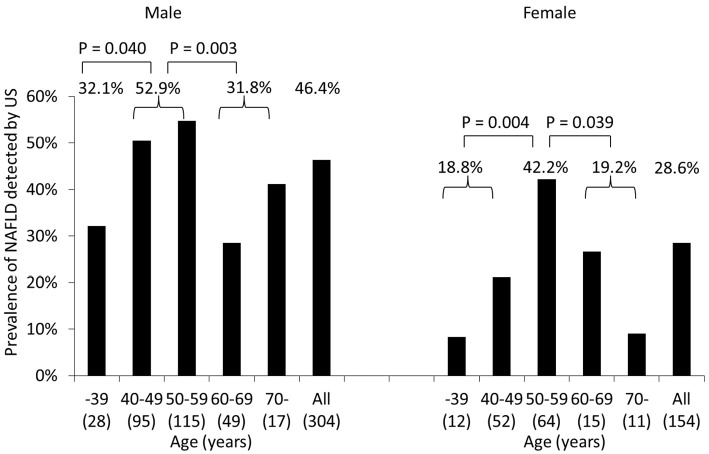

The NAFLD prevalence determined by US was significantly higher in men (46.4%) than in women (28.6%) (p<0.001) (Table 1, Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Prevalence of NAFLD diagnosed by US in groups stratified by gender and age. The prevalence of NAFLD was considerably higher in men (46.4%) than in women (28.6%) (p<0.001). Men 40-59 years old had a substantially greater prevalence of NAFLD than did those ≤39 or ≥60 years old (p=0.040 and p=0.003). The prevalence of NAFLD in women was significantly higher in the subjects 50-59 years old than in those ≤49 or ≥60 years old (p=0.004 and p=0.039). NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, US: ultrasonography

There was no marked difference in the mean age between subjects with and without NAFLD diagnosed by US (Table 1). However, the NAFLD occurrence in men was significantly higher in the subjects 40-59 years old (52.9%) than in those ≤39 years old (32.1%, p=0.040) and those ≥60 years old (31.8%, p=0.003) (Fig. 4). The NAFLD prevalence in women was significantly higher in the subjects 50-59 years old (42.2%) than in those ≤49 years old (18.8%, p=0.004) and those ≥60 years old (19.2%, p=0.039).

Factors correlated with the diagnosis of NAFLD by CT

The diagnosis of NAFLD by CT was considerably closely related to the gender, height, body weight, body mass index (BMI), abdominal circumference, white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin (Hb) level, albumin level, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) level, creatinine level, high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol level, triglyceride (TG) level, HbA1c value, fasting blood glucose (FBS) level, and presence of dyslipidemia, hypertension, or diabetes mellitus (DM) (Table 1).

A multivariate study for variables correlated with NAFLD was conducted with the gender, age, BMI, abdominal circumference, WBC count, Hb level, albumin level, creatinine level, HDL-cholesterol level, TG level, hypertension, and DM. A wider abdominal circumference [odds ratio (OR)=1.120; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.080-1.161], higher Hb level (OR=1.553; 95% CI: 1.180-2.044), lower HDL-cholesterol level (OR=0.959; 95% CI: 0.937-0.982), higher albumin level (OR=5.036; 95% CI: 1.525-16.628), and the presence of DM (OR=3.261; 95% CI: 1.203-8.837) were selected as independent predictors of NAFLD on CT (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis for Factors Associated with Fatty Liver Detected by CT.

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal circumference | 1.120 | 1.080-1.161 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin | 1.553 | 1.180-2.044 | 0.002 |

| HDL cholesterol | 0.959 | 0.937-0.982 | <0.001 |

| Albumin | 5.036 | 1.525-16.628 | 0.008 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.261 | 1.203-8.837 | 0.020 |

CT: computed tomography, HDL cholesterol: high density lipoprotein cholesterol

Factors correlated with the diagnosis of NAFLD by US

The diagnosis of NAFLD by US was considerably closely or tended to be related to the gender, height, body weight, BMI, abdominal circumference, WBC count, Hb level, platelet count, AST level, ALT level, GGT level, creatinine level, HDL-cholesterol level, TG level, low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol level, HbA1c value, FBS level, fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4 index), and presence of cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, DM, and smoking (Table 1).

A multivariate study for variables related to NAFLD was performed with the gender, age, BMI, abdominal circumference, WBC count, Hb level, platelet count, creatinine level, HDL-cholesterol level, TG level, LDL-cholesterol level, and presence of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, DM, and smoking. A higher BMI (OR=1.226; 95% CI: 1.072-1.402), wider abdominal circumference (OR=1.058; 95% CI: 1.008-1.111), and higher TG level (OR=1.010; 95% CI: 1.005-1.015) were selected as independent predictors of NAFLD on US (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis for Factors Associated with Fatty Liver Detected by US.

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 1.226 | 1.072-1.402 | 0.003 |

| Abdominal circumference | 1.058 | 1.008-1.111 | 0.021 |

| Triglyceride | 1.010 | 1.005-1.015 | <0.001 |

BMI: body mass index, US: ultrasonography

Prevalence and clinical correlates of MAFLD

The prevalence of MAFLD was assessed among all the subjects, including those with alcohol consumption or hepatitis virus infection, although the insulin resistance score and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein values were not determined.

MAFLD was diagnosed in 106 of 585 subjects (18.1%) by CT. A wider abdominal circumference (OR=1.142; 95% CI: 1.102-1.184), higher WBC count (OR=1.000; 95% CI: 1.000-1.000), higher Hb level (OR=1.550; 95% CI: 1.185-2.028), lower HDL-cholesterol level (OR=0.952; 95% CI: 0.932-0.973), higher albumin level (OR=3.873; 95% CI: 1.256-11.942), and presence of DM (OR=3.125; 95% CI: 1.192-8.192) were selected as independent predictors of MAFLD by CT.

MAFLD was diagnosed in 197 of 585 subjects (33.7%) by US. A higher BMI (OR=1.375; 95% CI: 1.180-1.602), wider abdominal circumference (OR=1.103; 95% CI: 1.043-1.166), higher TG level (OR=1.010; 95% CI: 1.006-1.015), lower HDL-cholesterol level (OR=0.980; 95% CI: 0.962-0.997), and lower creatinine level (OR=0.245; 95% CI: 0.061-0.993) were selected as independent predictors of MAFLD by US.

Discussion

The current research demonstrated that the NAFLD occurrence in the general population is 20.3% according to CT and 40.4% according to US. The NAFLD prevalence on CT in the general population was not previously detailed in Japan but was described to be 10-22% in other countries (14-18), which is in line with our findings. In Japan, the NAFLD prevalence in the overall population by US has been noted to be 25-57% (6-13), which is also in line with our findings.

The detection rate of FL by CT was greater in patients with more severe FL diagnosed by US than in milder cases. Tobari et al. reported that the detection rates of mild, moderate, and severe steatosis by CT vs. US were 10% vs. 53%, 28% vs. 64%, and 71% vs. 98%, respectively (23). The superior detection capability of US to CT and the higher detection rate in more severe steatosis by both US and CT are in line with our results. Our study is the first in the world to compare the NAFLD prevalence in the general population simultaneously by CT and US.

Seven subjects were diagnosed with NAFLD by CT but not by US. The mean CTL-S value in these cases was -1.9±2.1 Hounsfield units, which was significantly higher than in cases diagnosed with NAFLD by both CT and US (-13.9±13.2 Hounsfield units; p=0.018; data not shown). This indicates that the FL in these cases was mild and not detectable by US.

The NAFLD prevalence by CT and US was substantially higher in men than in women. Gender differences in NAFLD prevalence have been noted. The incidence was higher in men than in women in most reports (24), while some reported a comparable occurrence in women and men (14,25).

The NAFLD prevalence in men tended to be or was considerably higher in the subjects 40-59 years old than in those ≤39 or ≥60 years old by both CT and US. The NAFLD occurrence in women was substantially higher in the subjects 50-59 years old than in those ≤49 or ≥60 years old by US. An “inverted U curve,” in which the NAFLD prevalence rises with age and drops in late adulthood, has been reported (10,26,27). Our results correspond to these observations. However, a meta-analysis revealed a consistent rise in NAFLD occurrence across all age groups (3), and notably, the NAFLD prevalence was reported to surge in women after menopause (10,28-31). The highest NAFLD prevalence in women 50-59 years old in the present investigation corresponds to those prior reports.

The NAFLD prevalence declined in the subjects ≥60 years old in both genders. The Japanese National Health and Nutrition Survey stated that the occurrence of a BMI ≥25 was highest in those 40-59 years old among men and in those 60-69 years old among women (32). The age distribution of obesity accounts for the age prevalence of NAFLD in the current study. The reduction of the BMI in the elderly may be because of changes in their nutritional status (33), as a poor nutritional status is more frequent in the elderly than in younger individuals (34). Age-related alterations in the appetite, health problems, and social problems predispose the elderly to less food intake. The low NAFLD prevalence in the elderly may be ascribed to changes in the nutritional status.

NAFLD identified by CT was associated with a wider abdominal circumference, higher Hb levels, lower HDL-cholesterol levels, higher albumin levels, and the presence of DM. NAFLD detected by US was related to a higher BMI, wider abdominal circumference, and higher TG levels. The difference in the associated factors between CT and US is probably due to differences between the two methods in the ability to detect mild FL.

NAFLD has been noted to be linked to obesity, which is evaluated by the BMI and abdominal circumference, lipid profile, and DM (10,35,36). The current findings correspond to those in prior reports.

In the present study, Hb levels were linked to NAFLD prevalence perceived by CT. The association between Hb and NAFLD has already been reported (37-39). Several potential mechanisms underlying this association have been proposed. First, high Hb levels may trigger insulin resistance and then lead to NAFLD (40). Second, high Hb levels are associated with iron accumulation, which results in oxidative stress and leads to NAFLD (41). Third, NAFLD leads to sinusoidal distortion and hypoxia, which may induce compensatory erythropoiesis and high Hb levels (42).

The current research showed that increased albumin is associated with an increased NAFLD prevalence. Increased albumin was reported to be associated with NAFLD, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome (43,44). Our results correspond to those of previous studies.

Fifty of 93 subjects with FL by CT (53.8%) and 134 of 185 subjects with FL by US (72.4%) had normal AST and ALT levels (data not shown). These results indicate that a substantial portion of NAFLD subjects had normal AST and ALT levels. A meta-analysis reported that the proportion of NAFLD patients with normal ALT levels was 25% among overall NAFLD patients (45).

MAFLD has been proposed as a term to describe FL associated with known metabolic dysfunction (19,20). The criteria of MAFLD are FL with overweight/obesity, type 2 DM, or metabolic dysregulation, regardless of alcohol consumption or other concomitant liver diseases. The definition of MAFLD has been reported to be useful for selecting anti-HCC drugs (46) and assessing the risk of hepatic fibrosis (47), reflux esophagitis (48), and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (49). MAFLD was diagnosed in 18.1% of cases by CT and 33.7% of cases by US in the present study. The factors correlated with MAFLD were higher WBC counts and lower creatinine levels in addition to the factors associated with NAFLD. WBC counts have been previously reported to be associated with NAFLD (50), but another study conversely reported that higher creatinine levels were associated with FL (51). Further studies are thus needed to clarify the association between creatinine levels and MAFLD.

Several limitations associated with the present study warrant mention. First, this was a cross-sectional study demonstrating a decline in the NAFLD incidence among the elderly. However, to validate the remission of NAFLD in the elderly, prospective cohort studies are necessary. Second, NAFLD was diagnosed by CT or US in this research. A liver biopsy, the gold standard for diagnosing NAFLD, is invasive and carries a risk of severe complications. Therefore noninvasive modalities, including CAP, US, CT, and MRI, have been widely employed to detect NAFLD. MRI is expensive and scarce. The comparison between CAP and US for the ability to detect NAFLD was inconclusive (5). CAP is not generally available in Japan. The shortcoming of US is its subjective nature, although US is easily available in Japan. However, the high liver iron content increases the CT Hounsfield units and may confound the diagnosis of NAFLD, so the sensitivity of CT is less than that of US. Nevertheless, CT is extensively accessible in Japan, and the diagnosis is objective. Thus CT and US are promising methods for the detection of NAFLD. We can use CT when US is difficult to perform, such as in cases with obesity or excessive bowel gas, or when CT findings are already available. Third, the current investigation was carried out in a single hospital. The NAFLD prevalence and its associated factors should be reexamined in additional research from other centers.

In summary, NAFLD was found in 20.3% of CT cases and 40.4% of US cases among recipients of health checkups. An “inverted U curve” in which the NAFLD prevalence rose with age and dropped in late adulthood was reported. NAFLD was associated with obesity, the lipid profile, diabetes mellitus, hemoglobin values, and albumin levels. Our research is the first in the world to compare the NAFLD prevalence in the general population simultaneously by CT and US.

Author's disclosure of potential Conflicts of Interest (COI).

Kentaro Yoshioka: Consulting, Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho.

References

- 1. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 67: 328-357, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetologia 59: 1121-1140, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease - meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 64: 73-84, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee SS, Park SH, Kim HJ, et al. Non-invasive assessment of hepatic steatosis: prospective comparison of the accuracy of imaging examinations. J Hepatol 52: 579-585, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Castera L, Friedrich-Rust M, Loomba R. Noninvasive assessment of liver disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 156: 1264-1281.e4, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kojima S, Watanabe N, Numata M, Ogawa T, Matsuzaki S. Increase in the prevalence of fatty liver in Japan over the past 12 years: analysis of clinical background. J Gastroenterol 38: 954-961, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jimba S, Nakagami T, Takahashi M, et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with impaired glucose metabolism in Japanese adults. Diabet Med 22: 1141-1145, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Itoh Y, et al. The severity of ultrasonographic findings in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease reflects the metabolic syndrome and visceral fat accumulation. Am J Gastroenterol 102: 2708-2715, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kogiso T, Moriyoshi Y, Shimizu S, Nagahara H, Shiratori K. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein as a serum predictor of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease based on the Akaike Information Criterion scoring system in the general Japanese population. J Gastroenterol 44: 313-321, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eguchi Y, Hyogo H, Ono M, et al. Prevalence and associated metabolic factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the general population from 2009 to 2010 in Japan: a multicenter large retrospective study. J Gastroenterol 47: 586-595, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iwasaki T, Hirose A, Azuma T, et al. Correlation between ultrasound-diagnosed non-alcoholic fatty liver and periodontal condition in a cross-sectional study in Japan. Sci Rep 8: 7496, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yoshioka N, Ishigami M, Watanabe Y, et al. Effect of weight change and lifestyle modifications on the development or remission of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: sex-specific analysis. Sci Rep 10: 481, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nagaoki Y, Sugiyama A, Mino M, et al. Prevalence of fatty liver and advanced fibrosis by ultrasonography and FibroScan in a general population random sample. Hepatol Res 52: 908-918, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Foster T, Anania FA, Li D, Katz R, Budoff M. The prevalence and clinical correlates of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in African Americans: the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Dig Dis Sci 58: 2392-2398, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim NH, Park J, Kim SH, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome and subclinical cardiovascular changes in the general population. Heart 100: 938-943, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pickhardt PJ, Hahn L, Muñoz del Rio A, Park SH, Reeder SB, Said A. Natural history of hepatic steatosis: observed outcomes for subsequent liver and cardiovascular complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol 202: 752-758, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. VanWagner LB, Wilcox JE, Colangelo LA, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with subclinical myocardial remodeling and dysfunction: a population-based study. Hepatology 62: 773-783, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zeb I, Li D, Budoff MJ, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and incident cardiac events: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 67: 1965-1966, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol 73: 202-209, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kawaguchi T, Tsutsumi T, Nakano D, Eslam M, George J, Torimura T. MAFLD enhances clinical practice for liver disease in the Asia-Pacific region. Clin Mol Hepatol 28: 150-163, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Park YS, Park SH, Lee SS, et al. Biopsy-proven nonsteatotic liver in adults: estimation of reference range for difference in attenuation between the liver and the spleen at nonenhanced CT. Radiology 258: 760-766, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The Japan Society of Ultrasonics in Medicine Guidelines for ultrasonic diagnosis of fatty liver https://www.jsum.or.jp/committee/diagnostic/pdf/fatty_liver.pdf20212222021(in Japanese)

- 23. Tobari M, Hashimoto E, Yatsuji S, Torii N, Shiratori K. Imaging of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: advantages and pitfalls of ultrasonography and computed tomography. Intern Med 48: 739-746, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lonardo A, Nascimbeni F, Ballestri S, et al. Sex differences in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: state of the art and identification of research gaps. Hepatology 70: 1457-1469, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alam S, Fahim SM, Chowdhury MAB, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Bangladesh. JGH Open 2: 39-46, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koehler EM, Schouten JN, Hansen BE, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the elderly: results from the Rotterdam study. J Hepatol 57: 1305-1311, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alqahtani SA, Schattenberg JM. NAFLD in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging 16: 1633-1649, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Park SH, Jeon WK, Kim SH, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among Korean adults. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 21: 138-143, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wong VW, Chu WC, Wong GL, et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and advanced fibrosis in Hong Kong Chinese: a population study using proton-magnetic resonance spectroscopy and transient elastography. Gut 61: 409-415, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang Z, Xu M, Hu Z, Hultström M, Lai E. Sex-specific prevalence of fatty liver disease and associated metabolic factors in Wuhan, south central China. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 26: 1015-1021, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Long MT, Pedley A, Massaro JM, et al. A simple clinical model predicts incident hepatic steatosis in a community-based cohort: the Framingham Heart Study. Liver Int 38: 1495-1503, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. The National Health and Nutrition Survey Japan, 2019 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000687163.pdf (in Japanese)

- 33. Maeda K, Ishida Y, Nonogaki T, Mori N. Reference body mass index values and the prevalence of malnutrition according to the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition criteria. Clin Nutr 39: 180-184, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Volkert D. Malnutrition in older adults - urgent need for action: a plea for improving the nutritional situation of older adults. Gerontology 59: 328-333, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shima T, Uto H, Ueki K, et al. Clinicopathological features of liver injury in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and comparative study of histologically proven nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases with or without type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Gastroenterol 48: 515-525, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hazlehurst JM, Woods C, Marjot T, Cobbold JF, Tomlinson JW. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes. Metabolism 65: 1096-1108, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jiang Y, Zeng J, Chen B. Hemoglobin combined with triglyceride and ferritin in predicting non-alcoholic fatty liver. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 29: 1508-1514, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ding Q, Zhou Y, Zhang S, Liang M. Association between hemoglobin levels and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with young-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr J 67: 1139-1146, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yamane R, Yoshioka K, Hayashi K, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with age in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J Hepatol 14: 1226-1234, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Facchini FS, Carantoni M, Jeppesen J, Reaven GM. Hematocrit and hemoglobin are independently related to insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia in healthy, non-obese men and women. Metabolism 47: 831-835, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Delli Bovi AP, Marciano F, Mandato C, Siano MA, Savoia M, Vajro P. Oxidative stress in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. An updated mini review. Front Med (Lausanne) 8: 595371, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Farrell GC, Teoh NC, McCuskey RS. Hepatic microcirculation in fatty liver disease. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 291: 684-692, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cho HM, Kim HC, Lee JM, Oh SM, Choi DP, Suh I. The association between serum albumin levels and metabolic syndrome in a rural population of Korea. J Prev Med Public Health 45: 98-104, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bae JC, Seo SH, Hur KY, et al. Association between serum albumin, insulin resistance, and incident diabetes in nondiabetic subjects. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 28: 26-32, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ma X, Liu S, Zhang J, et al. Proportion of NAFLD patients with normal ALT value in overall NAFLD patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 20: 10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shimose S, Hiraoka A, Casadei-Gardini A, et al. The beneficial impact of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease on lenvatinib treatment in patients with non-viral hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res 53: 104-115, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Inamine S, Kage M, Akiba J, et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease directly related to liver fibrosis independent of insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and alcohol intake in morbidly obese patients. Hepatol Res 52: 841-858, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fukunaga S, Nakano D, Tsutsumi T, et al. Lean/normal-weight metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease is a risk factor for reflux esophagitis. Hepatol Res 52: 699-711, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tsutsumi T, Eslam M, Kawaguchi T, et al. MAFLD better predicts the progression of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk than NAFLD: generalized estimating equation approach. Hepatol Res 51: 1115-1128, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lee YJ, Lee HR, Shim JY, Moon BS, Lee JH, Kim JK. Relationship between white blood cell count and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis 42: 888-894, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ma J, Wei Z, Wang Q, et al. Association of serum creatinine with hepatic steatosis and fibrosis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol 22: 358, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]