Abstract

Hidden bow hunter's syndrome (HBHS) is a rare disease in which the vertebral artery (VA) occludes in a neutral position but recanalizes in a particular neck position. We herein report an HBHS case and assess its characteristics through a literature review. A 69-year-old man had repeated posterior-circulation infarcts with right VA occlusion. Cerebral angiography showed that the right VA was recanalized only with neck tilt. Decompression of the VA successfully prevented stroke recurrence. HBHS should be considered in patients with posterior circulation infarction with an occluded VA at its lower vertebral level. Diagnosing this syndrome correctly is important for preventing stroke recurrence.

Keywords: hidden bow hunter's syndrome, bow hunter's syndrome, posterior circulation infarction, stroke causes

Introduction

Hidden bow hunter's syndrome (HBHS) is an extremely rare disease in which the vertebral artery (VA) occludes in a neutral position but recanalizes in a particular neck position (1). Such occlusion of the involved VA in the neutral neck position makes the diagnosis difficult. However, as it can cause repeated infarctions, it is quite important to diagnose this syndrome correctly (2).

We herein report a case of HBHS in a 69-year-old man and additionally describe the characteristics of HBHS based on a literature review.

Case Report

A 69-year-old man was admitted to our hospital complaining of sudden-onset vertigo and nausea. He denied any recent trauma history, headache or neck pain. He had a history of hypertension and was taking eplerenone, valsartan, amlodipine and trichlormethiazide. He had a 40-pack-year history of smoking.

On admission, his vital signs were within normal limits except for blood pressure 165/57 mmHg. On a physical examination, he was alert but had slight thermal hypoalgesia on the left side of his body and right homonymous superior quadrantanopia. Apart from these pathological changes, he had no other focal neurological deficits. On blood tests, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and D-dimer levels were 50.1 pg/mL and 0.8 μg/mL, respectively. Other laboratory data, including transaminase levels, the renal function, electrolytes, complete blood count and coagulation tests, such as the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT), were within normal limits.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed infarctions in the right cerebellar hemisphere and left occipitotemporal lobe with right VA occlusion (Fig. 1a-c). No hyperintense vessel signs, obvious old infarction of the posterior circulation or VA dilatation were observed (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the first and second admission. a, b: Diffusion-weighted MRI revealed infarctions in the right cerebellar hemisphere and left occipitotemporal lobe. c: Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showed occlusion of the right vertebral artery (VA) (arrow). d: No dilatation of the VA was seen on basi-parallel anatomical scanning. e: MRA of the neck showed no recanalization of the right VA. f, g: A new infarction in the right cerebellar hemisphere with right PCA occlusion (arrow) was shown on MRI on the day of the second admission. h: Follow-up MRI on the day after the second admission showed a new infarction in the right PCA territory.

Aspirin and heparin were prescribed at first to address possible VA dissection or atherothrombotic in situ occlusion. Duplex ultrasound showed a systolic notch without end-diastolic flow velocity in the right VA, suggesting distal VA occlusion. Holter monitoring, echocardiography and a duplex ultrasound examination of the lower extremities did not reveal any embolic source of stroke. Neck magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) eight days after admission showed no recanalization of the right VA (Fig. 1e), after which treatment was switched to aspirin and clopidogrel, assuming atherothrombotic in situ occlusion.

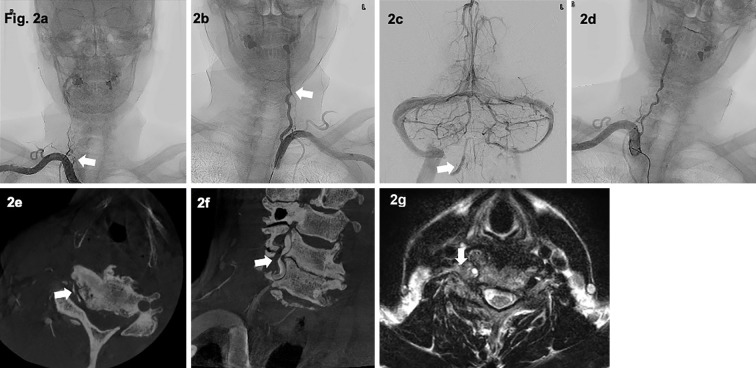

However, 4 months later, he was readmitted to our hospital with infarction recurrence (Fig. 1f-h). For a further evaluation, we performed cerebral angiography (Fig. 2). A right subclavian angiogram (SCAG) showed abrupt occlusion of the right VA at the C6 vertebral level, without antegrade reconstruction of the distal VA via anastomoses from other arteries, which is often seen in patients with chronic extracranial VA occlusion. A left SCAG showed stenosis of the left VA at the same level, and the left vertebral angiogram showed pooling of the contrast agent in the intracranial portion of the right VA, which also suggested nonchronic occlusion. Reversible obstruction of the right VA associated with the neck position was considered. We again performed right SCAG with the neck tilted to the left. The right VA was then recanalized with residual severe stenosis, which was consistent with the diagnosis of HBHS.

Figure 2.

Cerebral angiography and neck magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). a: A right subclavian angiogram (SCAG) showed abrupt occlusion of the right VA at the C6 vertebral level (arrow), with no antegrade reconstruction of the distal portion of the occluded right VA via anastomoses from other arteries originating from ipsilateral cervical or occipital arteries. b, c: A left SCAG showed stenosis of the left VA at the C6 level (arrow in b), and a left vertebral angiogram showed pooling of the contrast agent in the intracranial portion of the right VA (arrow in c). d: A right SCAG when the patient’s neck was tilted to the left showed that the right VA was recanalized. e, f: Contrast-enhanced cone beam CT (CBCT) with the neck tilted to the left showed severe stenosis of the right VA at the C5/6 level (arrows). g: T2-weighted MR imaging of the neck showed abnormal growth of the soft tissues and osteophytes compressing the VA from the anterolateral side at that level (arrow).

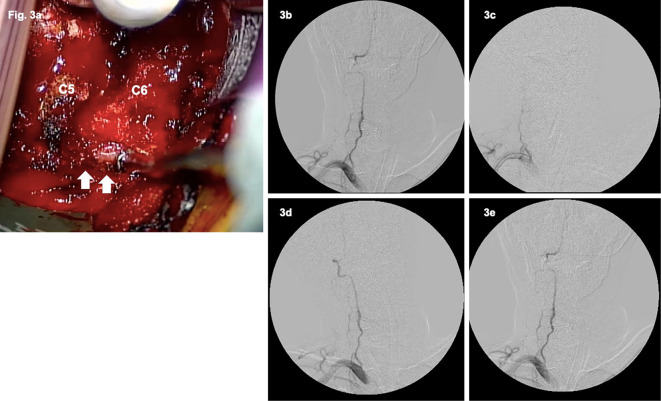

Contrast-enhanced cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) and MRI showed severe stenosis of the right VA compressed by the abnormal growth of soft tissues and osteophytes at the C5/6 vertebral levels (Fig. 2). Because ischemic stroke recurred even under dual antiplatelet treatment, we decided to perform surgical treatment (Fig. 3a). Cerebral angiography was performed at the beginning of the surgical intervention to check the position of the neck, in which the right VA remained open (Fig. 3b). We performed anterior cervical decompression and fusion with the removal of an osteophyte at the C5/6 uncovertebral joint that was compressing the right VA. Intraoperative angiography was used to ensure revascularization of the right VA in all neck positions (Fig. 3d, e).

Figure 3.

Surgical view and intraoperative angiography. a: At the C5/6 level, the VA (arrows) was compressed with soft tissues and osteophytes. b, c: Intraoperative angiography showed disappearance of occlusion of the right VA in the neutral position (b), but it remained occluded in the right lateral neck flexion position (c). d, e: Finally, intraoperative angiography showed a fully recanalized right VA without any residual stenosis in all neck positions (d: right lateral flexion, e: neutral position).

Without any perioperative complications, antiplatelets were discontinued three months after the surgery, and no recurrent strokes were observed during six months of follow-up.

Discussion

HBHS is a rare cause of embolic ischemic stroke in the posterior circulation area. A thrombus forms while the affected VA remains occluded and moves to distal arteries when the VA recanalizes in a particular neck position (1). Only six cases, including our own, have been reported for HBHS or its equivalent in the English and Japanese literature (1-5).

The characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table. Although HBHS is thought to be a subtype of Bow Hunter's syndrome (BHS), there are many differences between the two conditions. HBHS tends to involve lower cervical vertebral (C5-7) levels (5/6, 87%), while the C1/2 levels are typically affected in BHS (6,7). Transient vertebrobasilar insufficiency symptoms associated with neck rotation, typically seen in BHS (6), are uncommon in HBHS (1/5, 20%), and HBHS causes stroke recurrence (5/6, 86%), which may be refractory to antiplatelet therapy (3/5, 60%). Unlike BHS, the affected VA is occluded in the neutral neck position in HBHS, which leads to blood flow arrest and thrombus formation in the occluded vessel. Thromboembolic events occur when the affected VA recanalizes with a particular neck movement. Therefore, embolism, not hemodynamic failure, is the main mechanism underlying HBHS. This mechanism of embolism indicates the possible beneficial effect of anticoagulation over antiplatelet agents. The nondominant VA seems to be involved in HBHS, since occlusion of the dominant side can cause the prompt vertebrobasilar insufficiency seen in BHS (8). This explains why the right side, usually nondominant (9), is more likely to be affected in the HBHS than left VA.

Table.

Summary of Hidden Bow Hunter's Syndrome Cases.

| Reference | Age/Sex | Stroke symptoms | Transient symptoms associated with neck rotation | First-line treatment | History of stroke in the same area | Stroke Recurrence after the first-line treatment | Side of the affected VA | Compressed portion of the affected VA | Second-line treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2) | 74M | Visual defect | Yes | Antiplatelets | Yes | Yes | Right | C5/6 | Decompressive surgery | NA |

| (1) | 78M | Dizziness, gait disturbance, motor ataxia | NA | Antiplatelets +argatroban | Yes | Yes | Right | C6/7 | PAO | No recurrence for 9 months |

| (3) | 52M | Gait disturbance, hand dexterity disorder | None | Antiplatelets +heparin | Yes | No | Left | C6 | Decompressive surgery | No recurrence for 6 months |

| (5) | 74M | Hemianopia | None | Antiplatelets | No | NA | Right | C5 | None | NA |

| (4) | 57M | Dizziness, left hemiparesis | None | Antiplatelets, and restriction of neck movement | Yes | No | Left | C1/2 | None | No recurrence for 3 months |

| Present case | 69M | Dizziness and dysarthria | None | Antiplatelets +heparin | Yes | Yes | Right | C5/6 | Decompressive surgery | No recurrence for 6 months |

NA: not assessed, PAO: parent artery occlusion, VA: vertebral artery

Treatment

Treatment options for HBHS include conservative treatment with antithrombotic drugs, parent artery occlusion of the affected VA and spinal surgery to decompress the affected VA (1-5), similar to BHS (7). Spinal surgery for HBHS (3 in 6 cases) appears to be safe and effective since recurrent stroke was prevented in all surgery cases without any perioperative complications. In the present case, we hesitated to perform parent artery occlusion due to contralateral VA stenosis, so spinal surgery was performed. We also performed intraoperative angiography to prevent intraoperative stroke and confirm the effectiveness of decompression. The position of the neck during surgery was determined while considering the results of vertebral angiography in such a way that the affected VA remained open and therefore thrombus formation would not occur. Intraoperative angiography was also able to reveal insufficient decompression intraoperatively, which led to adequate decompression.

Conclusion

We experienced a case of HBHS and assessed the characteristics of this rare disease through a review of the literature. HBHS can be easily misdiagnosed as mere chronic occlusion on conventional MRA or cerebral angiography. However, it is important to diagnose this condition correctly, as it is refractory to antiplatelet treatment but might be treatable with surgical or endovascular treatment. Given our literature review, when encountering a patient with posterior circulation ischemia due to occlusion of the right VA at a lower vertebral level, we should consider the possibility of HBHS. Spine surgery for HBHS with intraoperative angiography is a safe and effective method of preventing stroke recurrence.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Alexander Zaboronok of the University of Tsukuba, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Neurosurgery for the professional and language revision and Dr. Thomas Mayers of the University of Tsukuba Medical English Communications Center for the language revision.

References

- 1. Mori K, Ishikawa K, Fukui I, et al. A subtype of bow hunter's syndrome requiring specific method for detection: a case of recurrent posterior circulation embolism due to “hidden bow hunter's syndrome”. J Neuroendovasc Ther 12: 295-302, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yagi K, Nakagawa H, Mure H, et al. Cryptic recanalization of chronic vertebral artery occlusion by head rotation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 26: e60-e1, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takai S, Kuga Y, Matsuoka R, et al. A case of rotational vertebral artery occlusion syndrome with a rare mechanism. Jpn J Neurosurg 29: 506-511, 2020. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xia J, Pan H, Jiang X, Liu P. Hidden Bow Hunter's syndrome combined with ossified left obliquus capitis superior. Ann Vasc Surg Brief Rep Innovations 2: 100074, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kano Y, Sato C, Uchida Y, et al. A case of posterior circulation embolism due to a subtype of bow hunter's syndrome diagnosed by non-invasive examination. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 31: 106178, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Regenhardt RW, Kozberg MG, Dmytriw AA, et al. Bow hunter's syndrome. Stroke 53: e26-e29, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schulz R, Donoso R, Weissman K. Rotational vertebral artery occlusion (“bow hunter syndrome"). Eur Spine J 30: 1440-1450, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Montano M, Alman K, Smith MJ, Boghosian G, Enochs WS. Bow Hunter's Syndrome: a rare cause of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Radiol Case Rep 16: 867-870, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cagnie B, Petrovic M, Voet D, Barbaix E, Cambier D. Vertebral artery dominance and hand preference: is there a correlation? Man Ther 11: 153-156, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]