Highlights

-

•

Influenza-like illness/severe acute respiratory illness surveillance can be leveraged to encompass viruses including respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

-

•

RSV found in 16.2% of children aged under 5 years with influenza-like illness and sever acute respiratory illness in Ethiopia.

-

•

Younger aged children are more affected by RSV than the older ones.

-

•

RSV infections are significantly associated with age of children and season.

Keywords: Epidemiology, RSV, SARI/ILI, Surveillance, Ethiopia

Abstract

Objectives

Acute respiratory infections because of respiratory syncytial viruses (RSVs) are among the major leading causes of morbidity and mortality in children worldwide. RSV prevalence and its contributing factors among children aged under 5 years in Ethiopia are not well studied. To assess the prevalence and associated factors of RSV infection in children aged under 5 years using influenza sentinel surveillance sites in Ethiopia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study design was used utilizing influenza-like illness/sever acute respiratory illness surveillance data from January 2021 to December 2022 at the Ethiopian Public Health Institute.

Results

In total, 2234 cases were included, with an overall RSV positivity rate of 16.2%. The RSV positivity rate was high in children aged under 1 year (22.8%) and during fall season (24.8%). The RSV positivity rate was significantly associated with ages under 1 year (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.8, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.89-4.15) and 1-2 years (AOR 1.9, 95% CI: 1.26-2.73) and the fall season (AOR 1.67, 95% CI: 1.17-2.38).

Conclusion

The study revealed that a considerably high RSV positivity rate was detected in children aged under 5 years. The age of children and season have a significant association with RSV positivity rate. Further studies of RSV viral genotype, clinical characteristics, and disease outcome need to be conducted for a better understanding of the virus and disease outcome.

Introduction

Acute respiratory tract infection (ARTI) is one of the major health issues in infants and children in the world causing morbidity and mortality and it is the most common reason for consultation and hospitalization in children and adults [1]. The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was first isolated in 1955 from chimpanzees with a respiratory illness at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in the United States. Later on in 1960, the virus was also detected in infants with severe lower respiratory illness [2].

Worldwide, the RSV is responsible for about 60,000 annual in-hospital deaths in children under 5 years and a leading viral cause of severe respiratory disease and hospitalization in young children [3]. Approximately 45% of the hospitalizations and deaths are caused by RSV-associated acute respiratory tract infection in infants aged under 6 months. In 2015 alone, 33.1 million new episodes of RSV-associated ALRI occurred worldwide in children aged less than 5 years, with at least 3.2 million hospitalizations and 59,600 in-hospital deaths [4].

The RSV results in clinical syndromes that include upper and lower respiratory tract disease [5]. Moreover, respiratory viral infections, including RSV infections, increase the risk of secondary bacterial infections, pneumonia, and sepsis [6]. The RSV virus is highly contagious transmitted by aerosol, contact with contaminated surface, and direct contact with infected individuals. Moreover, the occurrence of RSV transmission has seasonal patterns and as in many African countries of the tropics, such as Madagascar, Burkina Faso, and Mozambique, it occurs year-round and peaks during rainy seasons, although this may not true across other countries of African regions [7].

Most RSV infections present with nonspecific symptoms, and a definitive diagnosis for RSV primarily depends on laboratory investigation [2]. Currently, there are no effective treatment or vaccine available for RSV, except the Arexvy vaccine, which is manufactured by Fizzer Pfizer and recently approved by US Food and Drug Administration to be used for elderly people aged >60 years [8]. The RSV immunoprophylaxis called palivizumab is also approved for use in high-risk pediatric populations; thus, the reduction of morbidity and mortality in the general population is mainly relied on preventive measures [2].

Study reports from different parts of the world showed different RSV test positivity rates. A systematic review report conducted in Europe, Asia, and other regions in 2015 in those aged under 5 years with community-acquired pneumonia showed a 17.5% RSV positivity [9], whereas a 24.4% RSV positivity was reported in the Middle East and North Africa in 2020 [10]. A study of 2363 study participants from Malawi by Peterson et al. [11] showed an RSV positivity of 11.9% and had a strong association with severe acute respiratory illness (SARI) cases with warning signs. A surveillance data report from 2009-2012 from Kenya showed positivity rates of 11.9% and 10.4% for SARI and influenza-like illness (ILI) cases of those aged under 5 years, respectively [12].

Acute respiratory tract infections are among the major public health problems in Ethiopia. In the 2019 health and health-related indicator report by the Ministry of Health, Ethiopia showed that upper respiratory tract infections and pneumonia are among the top five causes of morbidity and mortality, respectively [13]. In Ethiopia, most acute respiratory illness (ARI) cases are treated empirically and overuse and inappropriate use of antibiotics for the relief of ARI is common [14].

There are no sufficient data showing the prevalence and associated factors of RSV infection in children under 5 years of age with acute respiratory infections in Ethiopia. As one of the major contributors for the acute respiratory infection–related morbidity and mortality, the RSV infection prevalence and associated factors need to be investigated and analyzed to better support the prevention and case management process. Thus, this study aimed to assess the prevalence and associated factors of RSV infection in children under 5 years with ILI and SARI in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study setting

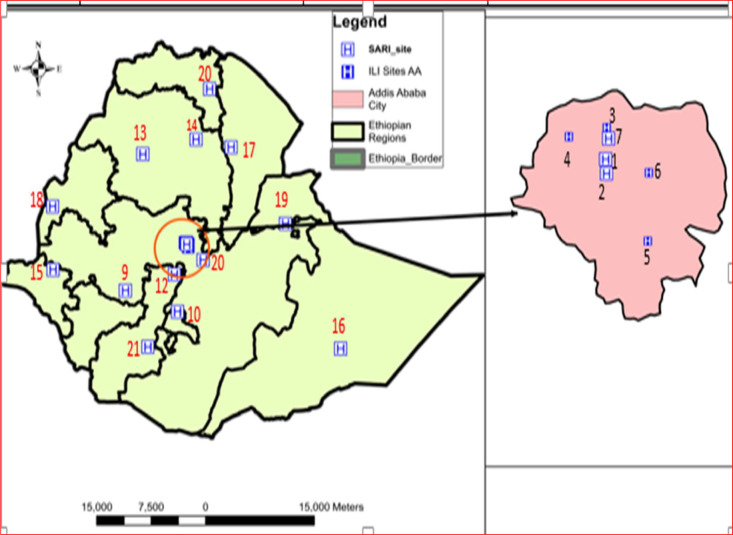

In Ethiopia, the Ethiopian Public Health Institute started the influenza sentinel surveillance in 2008 using two sentinel surveillance sites: one ILI and one SARI site located in Addis Ababa, the capital city. The sentinel surveillance was then expanded to include additional sites in Addis Ababa and across regions of Ethiopia. Currently, there are 21 influenza sentinel surveillance sites in the country, which are designated as ILI (all in Addis Ababa) and SARI sites, distributed across Addis Ababa and regional administrative states. Furthermore, four regional influenza and other respiratory virus molecular testing laboratories were established in Addis Ababa, Oromia, Amhara, and Southern Nation, Nationalities, and Peoples Region in August 2022 to build regional molecular testing capacities and decentralize the ILI/SARI testing system, which, in turn, can strengthen the surveillance and outbreak detection system.

This study included data from 19 actively working facilities and excluded two sites. There were no surveillance data received from sites in Mekele, Tigray owing to security issues and from Jinka, Southern Nation, Nationalities, and Peoples Region because the site was not operation in 2021-2022 (Figure 1, Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of study sites across the regions and Addis Ababa. The numbers indicated from the map are the name of the facility as listed in Supplemental Table 1.

ILI, influenza like illness; SARI, severe acute respiratory illness.

Data collection tools, procedure, and data quality assurance procedure

Data collected form the influenza sentinel surveillance system were used to conduct the RSV prevalence study. The data were collected by trained nurses, surveillance experts, laboratory technicians, or doctors at each sentinel sites. The sentinel sites used uniform and standardized case reporting formats adopted from the World Health Organization for ILI and SARI sentinel surveillance purposes. This standardized case investigation format consists of laboratory, clinical, and epidemiological information of each case. The samples from the sentinel sites and regional laboratories were transported to the testing laboratories on weekly and biweekly schedules. The laboratory testing for RSV was done by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), along with influenza and SARS-CoV-2, according to the kit manufacturer's standard operating procedure instructions.

Data analysis

All the demographic and test result data from Excel were coded and was exported to IBM SPSS version 20 for statistical analysis. Descriptive summary measures, such as frequencies and proportions, were computed to characterize the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics with the RSV test results. The association of each independent variable with the dependent variable was assessed using the binary logistic regression. The odds ratio (OR) along with the 95% confidence interval [CI] was used to assess the strength of association between the RSV positivity rate and the independent risk factors. Variables with P-value below 0.05 in the multivariable analysis were considered to have a statistically significant association.

Results

Demographic profile of the study participants

The total number of children under 5 years of age with completed RSV polymerase chain reaction test result enrolled by the ILI/SARI surveillance system during 2021-2022 were 2234 and of these, 1311 (59%) were males. The majority of the study participants were below 2 years of age (63%) and the average age of study participants was 1 year and 4 months and had an SD of 1.22. Moreover, the majority of study participants were SARI cases (1919 [86%]). About half of the study participants were residents of the capital city, Addis Ababa (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic description of the study participants.

| Variable | Category | Number of cases | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 923 | 41.3 |

| Male | 1311 | 58.7 | |

| Age (in years) | <1 | 604 | 27.0 |

| 1-2 | 848 | 38.0 | |

| 2-3 | 396 | 17.7 | |

| 3-5 | 386 | 17.3 | |

| Case classification | Influenza like illness (Outpatient) | 315 | 14.1 |

| Sever acute respiratory illness (Inpatient) | 1919 | 85.9 | |

| Region | Addis Ababa | 1072 | 48.0 |

| Other regions | 1162 | 52.0 | |

| Influenza test result | Positive | 179 | 8.0 |

| Negative | 2055 | 92.0 | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Positive | 74 | 3.3 |

| Negative | 2160 | 96.7 | |

| Year | 2021 | 332 | 14.9 |

| 2022 | 1902 | 85.1 | |

| Season | Winter | 742 | 33.2 |

| Spring | 641 | 28.7 | |

| Summer | 396 | 17.7 | |

| Autumn | 455 | 20.4 |

RSV positivity rate

Of all the 2234 tested children, 362 (16.2%) were positive for RSV by RT-PCR. RSV positivity rates of 15.9% in male and 16.7% in female study participants were detected. The RSV was detected across all age groups, with the highest positivity rate (22.8%) in infants and the lowest positivity rate (9.8%) in children older than 3 years of age. The RSV positivity in children with ILI was 15.2% (48), whereas the RSV positivity rate in children with SARI was 16.4% (314). A fairly higher positivity rate (17.2%) was also detected in children living in Addis Ababa compared with the 15.3% positivity rate outside of Addis Ababa (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors association with respiratory syncytial virus infection among under 5 children with severe acute respiratory and influenza like illness, 2021-2022, Ethiopia.

| Variable | Respiratory syncytial virus polymerase chain reaction result |

COR (95% confidence interval) | P-value | AOR | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (%) | Negative (%) | ||||||

| Sex | Female | 154(16.7) | 768(83.3) | 1.06(.85-1.33) | 0.60 | ||

| Male | 208(15.9) | 1103(84.1) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Age (in years) | <1 | 138(22.8) | 466(77.2) | 2.712(1.85-3.99 | <.001a | 2.53(1.71-3.73) | <0.001b |

| 1-<2 | 140(16.5) | 708(83.5) | 1.811(1.24-2.65) | 0.002a | 1.78(1.21-2.61) | 0.003b | |

| 2-<3 | 46(11.6) | 350(88.4) | 1.204(.76-1.90) | 0.424 | 1.18(.75-1.87) | 0.469 | |

| 3<-=5 | 38(9.8) | 348(90.2) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Case classification | Influenza like illness (outpatient) | 48(15.2) | 267(84.8) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Severe acute respiratory illness (outpatient) | 314(16.4) | 1604(83.6) | 1.098(.79-1.53) | 0.580 | |||

| Type of Specimen | Nasopharyngeal | 135(14.2) | 816(85.8) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Throat swab | 22717.7) | 1056(82.3) | 1.310(1.04-1.65) | 0.022a | 1.170(.91-1.50) | 0.215 | |

| Region | Addis Ababa | 184(17.2) | 888(82.8) | 1.145(.92-1.44) | 0.237 | ||

| Other region | 178(15.3) | 984(84.7) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Influenza test result | Positive | 21(13.3) | 137(86.7) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Negative | 341(16.6) | 1714(83.4) | 1.49(0.94-2.39) | 0.092 | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 | Positive | 15(20.3) | 59(79.7) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Negative | 34716.1) | 1813(83.9) | 0.75(0.42-1.34) | 0.34 | |||

| Year | 2021 | 82(24.7) | 250(75.3) | 1.9(1.44-2.51) | <0.001a | 1.170(.79-1.73) | 0.434 |

| 2022 | 280(14.7) | 1622(85.3) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Season | Spring(Mar-May) | 79(12.3) | 562(87.7) | 0.83(0.61-1.14) | 0.25 | .81(.59-1.12) | 0.204 |

| Summer(Dec-Feb) | 63(15.9) | 333(84.1) | 1.12(0.80-1.58) | 0.50 | 1.12(.79-1.58) | 0.516 | |

| Autumn(Sep-Nov) | 113(24.8) | 342(75.2)) | 1.96(1.46-2.63) | <0.001 | 1.67(1.17-2.38) | 0.005b | |

| Winter(Jun-Aug) | 107(14.4) | 635(85.6) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

Key: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; COR, crude odds ratio.

Significant association in COR

Significant association in AOR.

Distribution of RSV across the sentinel sites and month

The RSV was detected across all sentinel sites, except the Gambella, Gode, and Shiromeda sites. The highest RSV positivity was detected in cases enrolled in the Akaki health center (29 [31%]), followed by Adare (58 [23%]) and Felegehiwot hospitals (18 [20.0%]). Nearly a quarter of the detected RSV cases were from the Yekatit 12 hospital sentinel site (91 [18.1%]) (Supplemental Figure 1).

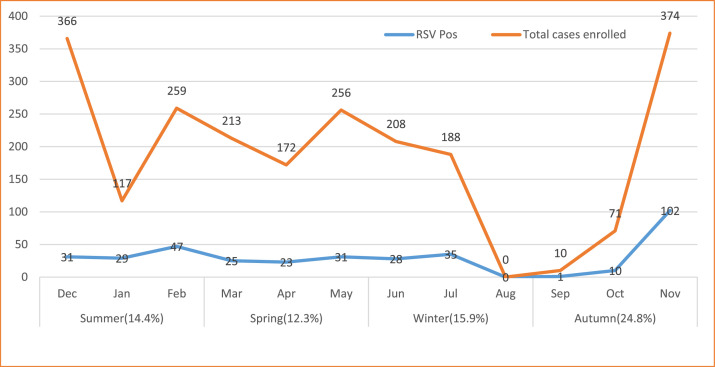

The RSV was detected in all four seasons, with highest positivity rate in fall (113 [24.8%]), followed by the rainy season of winter (63 [15.9%]). It was circulating year-round, with highest positivity rate in the month of November, followed by January, July, and February. Laboratory testing of the RSV was interrupted in the August owing to a shortage of laboratory detection kits (Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of total enrolled cases and RSV positivity by season, Ethiopia. The percent in brackets of the seasons represent the RSV positivity rate of each season. RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Factors associated with RSV infections

The age category of children, type of samples collected, and seasonality were significantly associated with RSV positivity rate in the bivariable logistic regression. However, the type of specimen collected was not significantly associated in the multivariable logistic regression. In the multivariable analysis, the age of the study participants was significantly associated with the RSV positivity rate (adjusted OR [AOR] 2.8, 95% CI 1.9-4.1) for age <1 year and (AOR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3-2.7) for the age category of 1-<2 years) compared with the age category of 3-5 years. In addition, RSV test positivity was significantly associated with the fall season (AOR 1.67 95% CI 1.17-2.38). Although, sex, residential region of cases, and case classification, influenza or SARS-CoV-2 result status had no statistically significant association in the overall RSV infection in the study participants (Table 2).

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the prevalence of RSV in children aged under 5 years across the influenza sentinel surveillance sites in Ethiopia. The overall RSV positivity was 16.2%. The prevalence was higher in younger aged children and during the season of fall.

Our study finding revealed that RSV is one of the major contributing agents in children aged under 5 years with ARI. The 16.2% RSV positivity rate is, by far, higher than the influenza test positivity rate reports of 6.7% in 2018 [15] and 5.9% in 2020 [16] that were conducted in Ethiopia. In addition, the RSV positivity rate from our study is higher than the influenza positivity rate of 8.0% and SARS-CoV-2 (3.3%) during the same study period and setting for the same age category (unpublished influenza sentinel surveillance data from the Ethiopian Public Health Institute). This indicates that the RSV accounts for a large share of ARI in children under 5 years of age, which needs a huge emphasis in disease prevention, control, and management by concerned bodies.

The epidemiology of RSV-associated ARI has not been explored well in Ethiopia previously. In a previous study by Weldetsadik et al. [17] by enrolling 117 children from a single tertiary hospital, the positivity rate was 22.2%, which is in agreement with our age disaggregated report of a 22.8% positivity rate in children aged under 1 year [17]. Compared with studies in other countries, our overall positivity rate of 16.2% was also similar with that of the 15.5% in Senegal [18], 14% in Kenya [19], and 18% and 16.0% in China [20]. However, our study finding was lower than that of the study reports of 20.7% in Kenya [21], 40.5% [22] in Morocco, and 46.1% in Kashmir India [23]. The higher positivity rate from previous studies other than ours might be owing to a single densely populated slummy study site in Kenya and the use of combined oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal specimen testing and a shorter date of disease onset during study participant enrollment in Morocco. The lower positivity rate of our study finding compared with the 24.4% of South Africa [24] might be owing to the study participant characteristics, which included HIV-positive cases and the majority of them were children under 1 year of age, in whom underlying health conditions and age play a role in RSV infection risk in many other studies. Moreover, the shorter date of sample collection from date disease onset and the very young age (>3 months) of study participants, the majority of whom have underlying health conditions, included in the study from India might also be a reason for the higher positivity rate than ours. Moreover, the time of COVID-19 pandemic also may play great role because the infection prevention and control practice during the pandemic and before the pandemic might be different. Our study was conducted during 2021-2022, when the infection prevention and control measures were more practiced, in line with the COVID-19 pandemic prevention and response directives/guidance. On the other hand, our finding showed a higher positivity rate than the 13.5% in Gabon [25] and 11.8% in the Philippines [26]; in the case of Gabon, this may be because the study participants included were mainly ambulatory (ILI) cases, and, in the case of the study in the Philippines, RSV test results from samples that were archived for a long time were used; both cases could contribute to the lower RSV test positivity difference.

In the present study, children below the age of 2 years were more affected than the other age group, and similarly higher RSV positivity rates for lower age groups were reported in Congo and Pakistan [27,28]. This higher positivity rate might be owing to the higher rate of nosocomial spread of the RSV virus in the pediatric groups and, of course, owing to the immature level of immunity against the RSV infection. This study also indicated that the RSV positivity rate was the highest in fall season, especially in month of November. The RSV seasonal distribution is more common in fall (24.8%), followed by the rainy season (15.9%), which revealed a similar seasonal distribution of RSV [17] and influenza virus in Ethiopia [15,16]. Reports from other countries in the tropics and subtropics presented a higher RSV test positivity during the rainy seasons [25,[28], [29], [30]. The difference may be owing to the length/season of the study, distribution of study participants across all months of seasons, and other factors.

Strength and limitation of the study

Fairly, nationally representative, large data collected from 19 study sites in Ethiopia were used. The gold-standard and reliable RT-PCR testing was used to ensure the quality of the RSV test results. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study finding produced from the analysis of fresh specimens collected from such a large number of study sites across Ethiopia. This study has also limitations which include the absence of clinical features of the study participants and the sample distribution was not proportionally allocated to each month of the study period, which may affect the seasonal distribution of the RSV in the study.

Conclusion

The study revealed that the RSV positivity rate was 16.2% in children aged under 5 years in Ethiopia. The RSV positivity was highest in children under 2 years of age. The highest prevalence was observed during the season of fall, followed by the rainy season of summer. Age and seasonality were strongly associated with RSV positivity.

Because the RSV circulation in cases under the age of 5 years was considerably high, it should be considered in the prevention and control of infection and case management procedures. The data quality needs to be improved to successfully meet the surveillance objectives. Further studies on the RSV viral genotype, clinical characteristics, and additional factors, including underlying health conditions and disease outcome, need to be conducted for a better understanding of the virus and epidemiology of infection and to design a better intervention mechanism.

Declarations of competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was conducted through the analysis of ILI/SARI surveillance data, which was supported through the financial, technical, and logistic support from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under Strengthening Ownership and Sustainable Provision of Comprehensive COVID-19 Services by the Ethiopian Public Health Institute of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia under the CARES Project. The surveillance program also received logistic, technical, and financial supports from the OSU-GOHi and World Health Organization. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of any of these organizations.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of Addis Continental Institute of Public Health (Ref. No: ACIPH-MPH/006/15). Permission was also obtained from the Ethiopian Public Health Institute to access and use these surveillance data. The privacy and confidentiality of cases from the data are maintained during the whole stages of study, and unique and anonymous identifier were used for analysis and future dissemination.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, OSU-GOHi, and the World Health Organization for funding and supporting this project and the Ethiopian Public Health Institute and RHBs for technical support and overall guidance of the surveillance implementation. The authors would like to acknowledge the tremendous technical support provided by the experts from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Ethiopia in conducting the surveillance work. The authors are also grateful to ACIPH for the review, approval of the proposal, and subsequent technical support of this study. Finally, the authors would like to acknowledge the participating study sites and clients for their participation in this work.

Author contributions

AT conceptualized, designed, and drafted the manuscript. GT, AG, and FW involved in conceptualize the study idea. AT, AG, EG, and YG conducted the data quality control and analysis. AT, WS, AA, MG, AH, and FE performed the laboratory analysis. AT, GT, AG, WS, MB, LC, TB, ET, LG, AA, MG, AH, AW, AA, YG, LL, KY, EA, AA, YG, MW, MH, and FW reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijregi.2024.01.004.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Divarathne MVM, Ahamed RR, Noordeen F. The impact of RSV-associated respiratory disease on children in Asia. J Pediatr Infect Dis. 2019;14:79–88. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1637752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chatterjee A, Mavunda K, Krilov LR. Current state of respiratory syncytial virus disease and management. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10:5–16. doi: 10.1007/s40121-020-00387-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham BS. Vaccine development for respiratory syncytial virus. Curr Opin Virol. 2017;23:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi T, McAllister DA, O'Brien KL, Simoes EA, Madhi SA, Gessner BD, et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2015: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet. 2017;390:946–958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30938-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drysdale SB, Green CA, Sande CJ. Best practice in the prevention and management of paediatric respiratory syncytial virus infection. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2016;3:63–71. doi: 10.1177/2049936116630243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azar MM, Landry L. Detection of influenza A and B viruses and respiratory. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;1988:1–13. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00367-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenmoe S, Bigna JJ, Well EA, Simo FB, Penlap VB, Vabret A, et al. Prevalence of human respiratory syncytial virus infection in people with acute respiratory tract infections in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2018;12:793–803. doi: 10.1111/irv.12584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Food Drug Administration US . 2023. FDA news release. FDA approves first respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine (May 2023) [accessed; 18 September 2023] [Google Scholar]; https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-vaccine.

- 9.Wang M, Cai F, Wu X, Wu T, Su X, Shi Y. Incidence of viral infection detected by PCR and real-time PCR in childhood community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Respirology. 2015;20:405–412. doi: 10.1111/resp.12472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yassine HM, Sohail MU, Younes N, Nasrallah GK. Systematic review of the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) prevalence, genotype distribution, and seasonality in children from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Microorganisms. 2020;8:713. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8050713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson I, Bar-Zeev N, Kennedy N, Ho A, Newberry L, SanJoaquin MA, et al. Respiratory virus-associated severe acute respiratory illness and viral clustering in Malawian children in a setting with a high prevalence of HIV infection, malaria, and malnutrition. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1700–1711. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emukule GO, Khagayi S, McMorrow ML, Ochola R, Otieno N, Widdowson MA, et al. The burden of influenza and rsv among inpatients and outpatients in rural western Kenya, 2009–2012. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health Ethiopia. Health & health-related indicators 2018/19. 2019. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.Ministry of Health Ethiopia. Health & health-related indicators 2018/19. 2019.

- 14.Gebeyehu E, Bantie L, Azage M. Inappropriate use of antibiotics and its associated factors among urban and rural communities of Bahir Dar city administration, northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woyessa AB, Mengesha M, Belay D, Tayachew A, Ayele W, Beyene B, et al. Epidemiology of influenza in Ethiopia: findings from influenza sentinel surveillance and respiratory infection outbreak investigations, 2009–2015. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:449. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tadesse M, Mengesha M, Tayachew A, Belay D, Hassen A, Woyessa AB, et al. Burden and seasonality of medically attended influenza like illness (ILI) in Ethiopia, 2012 to 2017. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:148. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-4827-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weldetsadik AY, Riedel F. Respiratory syncytial virus in severe lower respiratory infections in previously healthy young Ethiopian infants. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21:201. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02675-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fall A, Dia N, Hadj E, Kader A, Kiori DE, Sarr FD, Sy S, et al. Epidemiology and molecular characterization of human respiratory syncytial virus in Senegal after four consecutive years of surveillance, 2012–2015. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose EB, Nyawanda BO, Munywoki PK, Murunga N, Bigogo GM, Otieno NA, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus seasonality in three epidemiological zones of Kenya. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2021;15:195–201. doi: 10.1111/irv.12810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Y, Wei D, Gong X, Shen Y, Zhu Y, Wang J, et al. Initial use of voriconazole positively affects outcome of Candida parapsilosis bloodstream infection: a retrospective analysis. Transl Pediatr. 2020;9:480–486. doi: 10.21037/tp-20-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breiman RF, Cosmas L, Njenga MK, Williamson J, Mott JA, Katz MA, et al. Severe acute respiratory infection in children in a densely populated urban slum in Kenya, 2007–2011. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:95. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0827-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bimouhen A, El Falaki F, Ihazmad H, Regragui Z, Benkerroum S, Barakat A. Circulation of respiratory syncytial virus in Morocco during 2014–2016: findings from a sentinel-based virological surveillance system for Influenz nflue–2016. East Mediterr Heal J. 2016;22:483–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koul PA, Saha S, Kaul KA, Mir H, Potdar V, Chadha M, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus among children hospitalized with severe acute respiratory infection in Kashmir, a temperate region in northern India. J Glob Health. 2022;12 doi: 10.7189/jogh.12.04050. 04050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moleleki M, du Plessis M, Ndlangisa K, Reddy C, Hellferscee O, Mekgoe O, et al. Pathogens detected using a syndromic molecular diagnostic platform in patients hospitalized with severe respiratory illness in South Africa in 2017. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;122:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lekana-Douki SE, Nkoghe D, Drosten C, Ngoungou EB, Drexler JF, Leroy EM. Viral etiology and seasonality of influenza-like illness in Gabon, March 2010 to June 2011. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:373. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calaor-Morin J, Arguelles VL, Foronda JL, Tan A, Lagamayo E, Dapat C, et al. Genotyping of respiratory syncytial virus among influenza-like illness and severe acute respiratory infection cases of children in the Philippines from 2006 to 2016. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2022;16:942–951. doi: 10.1111/irv.12986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapandji M, Kavunga-membo H, Nkwembe E, Ahuka S, Muyembe JJ. 16 March 2022. Seasonality and prevalence of respiratory syncytial virus in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Research Square. [accessed 12 May 2023] [Google Scholar]; https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-1342925/v1.

- 28.Ali A, Yousafzai MT, Waris R, Jafri F, Aziz F, Abbasi IN, et al. RSV associated hospitalizations in children in Karachi, Pakistan: implications for vaccine prevention strategies. J Med Virol. 2017;89:1151–1157. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghia C, Rambhad G. Disease burden due to respiratory syncytial virus in Indian pediatric population: a literature review. Clin Med Insights Pediatr. 2021;15 doi: 10.1177/11795565211029250. 11795565211029250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang JW, Loh TP. Correlations between climate factors and incidence–a contributor to RSV seasonality. Rev Med Virol. 2014;24:15–34. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.