Abstract

Numerous investigations have characterized the oscillatory dynamics serving working memory in adults, but few have probed its relationship with chronological age in developing youth. We recorded magnetoencephalography during a modified Sternberg verbal working memory task in 82 youth participants aged 6–14 years old. Significant oscillatory responses were identified and imaged using a beamforming approach and the resulting whole-brain maps were probed for developmental effects during the encoding and maintenance phases. Our results indicated robust oscillatory responses in the theta (4–7 Hz) and alpha (8–14 Hz) range, with older participants exhibiting stronger alpha oscillations in left-hemispheric language regions. Older participants also had greater occipital theta power during encoding. Interestingly, there were sex-by-age interaction effects in cerebellar cortices during encoding and in the right superior temporal region during maintenance. These results extend the existing literature on working memory development by showing strong associations between age and oscillatory dynamics across a distributed network. To our knowledge, these findings are the first to link chronological age to alpha and theta oscillatory responses serving working memory encoding and maintenance, both across and between male and female youth; they reveal robust developmental effects in crucial brain regions serving higher order functions.

1. Introduction

Working memory improves from childhood to adolescence as youth become more skilled at briefly holding and manipulating information for better learning and planning (Gathercole et al., 2004b). These behavioral improvements are thought to reflect increasing functional specialization of brain regions supporting stimulus encoding and maintenance during working memory, with mature levels of processing requiring efficient functional integration of information across these neural regions (Scherf et al., 2006). Such developmental changes in the prefrontal cortex have been widely reported (Blakemore and Choudhury, 2006, Kwon et al., 2002, O'Hare et al., 2008, Rosenberg et al., 2020), and this region’s involvement in working memory processing has been suggested to aid in information transfer across multiple cortical regions, especially in cases where more than one cognitive operation is required (Ramnani and Owen, 2004). As part of the fronto-parietal network, the left inferior parietal cortex also undergoes structural and functional changes with age and has been associated with processes such as phonological encoding (Andre et al., 2016, Attout et al., 2019, Østby et al., 2011, Ravizza et al., 2004).

While our understanding of the key brain regions involved in working memory processing has grown considerably, the inherent dynamics within these neural regions remain poorly understood. Neural processing during discreet stages of working memory can be studied using the Sternberg task, which requires individuals to encode stimuli into memory stores and briefly maintain these representations for eventual retrieval and differs from the N-back task which elicits parallel encoding and maintenance operations (Rottschy et al., 2012). Numerous magnetoencephalography (MEG) studies have reported stronger alpha oscillations (8–12 Hz; decreases in power) during encoding in bilateral occipital cortices, which tends to gradually move anteriorly during maintenance into left-lateralized language regions, like the left temporal, supramarginal, and prefrontal cortices (Embury et al., 2018, Embury et al., 2019, Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson, 2015, McDermott et al., 2016, Proskovec et al., 2016, Wilson et al., 2017). Concurrently, during maintenance, MEG studies have shown that the initial alpha response in bilateral occipital cortices progressively weakens and becomes an increase in alpha power within parieto-occipital regions (Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson, 2015, Proskovec et al., 2016, Wiesman et al., 2016). In addition, multiple EEG (Cavanagh and Frank, 2014, Fellrath et al., 2016, Klimesch, 1999) and MEG (Brookes et al., 2011, Jensen and Tesche, 2002) studies have reported increased frontal theta during maintenance that scales with task difficulty, suggesting a possible role in attention and/or executive function.

To characterize developmental changes in the oscillatory dynamics serving working memory, one MEG study used a six-load version of the Sternberg task in a sample of typically developing 9-to-14-year-olds (Embury et al., 2019). Aside from the improvements in performance expected with increased age, this study did not find significant main effects of age (i.e., across both sexes). Instead, they found age-by-sex interactions with older females exhibiting significantly stronger alpha oscillations during encoding in the right inferior frontal cortex than younger females, while older males showed stronger increases in alpha during maintenance compared to younger males in right occipital, right cerebellar, and parietal cortices. They suggested that the prefrontal and posterior cortices that support top-down executive control and storage during working memory have developmental trajectories that briefly diverge in a sex-specific manner before converging later in young adulthood (Embury et al., 2019).

Although MEG working memory studies have been conducted in child and adolescent samples (Embury et al., 2019, Heinrichs-Graham et al., 2021, Heinrichs-Graham et al., 2022, Killanin et al., 2022), only one has probed age-related changes in a typically developing sample (Embury et al., 2019). In the current investigation, we examined a younger (6–14 years-old), and larger, sample of typically developing youths and focused on the neural oscillatory activity that supports the encoding and maintenance phases of verbal working memory. By examining a younger sample than previous studies, we hoped to capture unique developmental patterns that emerge as networks become more refined during adolescence. For example, as children learn to read, verbal rehearsal becomes more reliable, enabling them to recode visual stimuli more readily into their phonological forms for maintenance (Gathercole et al., 2004a). We hypothesized that alpha oscillatory activity would become stronger in older participants, during both encoding and maintenance periods, in left-lateralized language regions. We also hypothesized that we would identify significant sex differences in these patterns of developmental change in the neural oscillatory dynamics serving working memory.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 106 participants between the ages of 6 and 14 years old (M = 10.07 years, SD = 2.53; 50 females; 11 left-handed) were recruited from the community, as part of the Developmental Multimodal Imaging of Neurocognitive Dynamics (Dev-MIND) study, an NIH supported project employing an accelerated longitudinal design to investigate brain and cognitive development (R01-MH121101). Of note, due to the accelerated longitudinal design of the study, 10-year-olds were not enrolled. The current investigation utilizes cross-sectional data collected exclusively during year one of the study. Participants were all typically developing primary English speakers and did not have diagnosed psychiatric or neurological conditions, previous head trauma, learning disability, or non-removable ferromagnetic material (e.g., orthodonture). After a complete description of the study, written informed assent and consent was obtained from the child and child’s parent or legal guardian, respectively. All procedures were completed at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) and approved by the UNMC Institutional Review Board (IRB).

2.2. MEG experimental paradigm

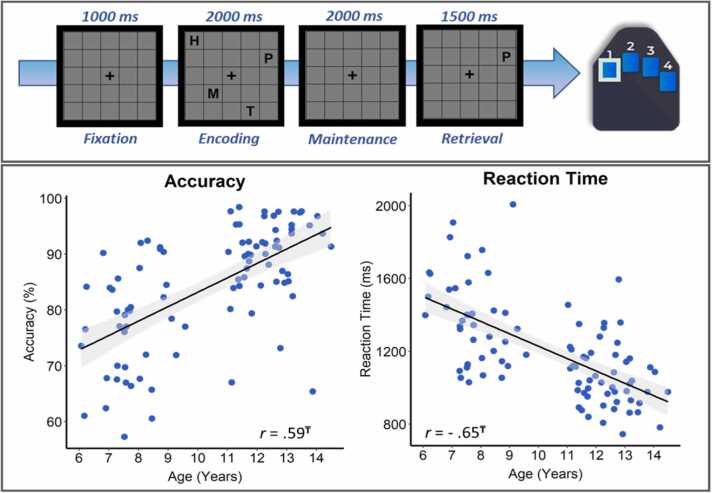

Participants completed a modified Sternberg verbal working memory task similar to those used in several previous studies of adults (Embury et al., 2018, Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson, 2015, Proskovec et al., 2018, Proskovec et al., 2019, Wilson et al., 2017) and youths (Embury et al., 2019). Participants rested their right hand on a custom five-finger button response pad directly connected to the MEG system so that each button press sent a TTL pulse to the acquisition computer in real-time, enabling behavioral responses to be temporally synced with the MEG data. Accuracy and reaction time were calculated offline. Participants were shown a centrally presented fixation cross embedded in a 5 × 5 grid for 1000 ms (i.e., baseline period). An array of four consonants then appeared at fixed locations within the grid for 2000 ms (i.e., encoding period). The letters disappeared from the array leaving an empty grid shown for 2000 ms (i.e., maintenance period), during which participants had to maintain the encoded letters from the previous phase. A probe letter then appeared on the grid for 1500 ms (i.e., retrieval period), and participants were instructed to respond with their right index if the probe letter was found in the previous array of letters or with their middle finger if it was not. Participants completed 128 trials, split equally and pseudorandomized between in- and out-of-set trials, for a total run time of about 15 min (see Fig. 1). Thus, our task design involved participants completing the same encoding and maintenance processes, but different retrieval processes depending on the probe set (i.e., in-set versus out-of-set). Given this and the fact that reaction times robustly differed with age, we focused our MEG analyses on the encoding and maintenance periods. Visual stimuli were presented using the E-Prime 2.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA), and back-projected onto a semi-translucent nonmagnetic screen at an approximate distance of 1.07 m, using a Panasonic PT-D7700U-K model DLP projector with a refresh rate of 60 Hz and a contrast ratio of 4000:1.

Fig. 1.

Modified Sternberg verbal working memory task and behavior. (Top) Example trial of the modified Sternberg working memory task along with the corresponding correct response. (Bottom) Accuracy and reaction time were significantly correlated with chronological age. ₸ p < .001.

2.3. MEG data acquisition

Prior to MEG data acquisition, four head-position indicator (HPI) coils were attached to each participant’s head and localized, along with the three fiducial points and scalp surface, using a 3-D digitizer (Fastrak, Polhemus Navigator Sciences, Colchester, VT). Participants were then seated in a nonmagnetic chair within a one-layer magnetically shielded room with active shielding engaged. Neuromagnetic responses were sampled continuously at 1 kHz with an acquisition bandwidth of 0.1–330 Hz using an MEG system with 306 magnetic sensors (MEGIN, Helsinki, Finland). Throughout the recording, an electric current with a unique frequency label was fed to each of the HPI coils, inducing a measurable magnetic field such that each coil could be localized in reference to the sensors. Since these coil locations were also known in head coordinates, all MEG measurements could be transformed into a common coordinate system. MEG data from each subject were individually corrected for head motion (MaxFilter v2.2; MEGIN) and subjected to noise reduction using the signal space separation method with a temporal extension (Taulu and Simola, 2006, Taulu et al., 2005).

2.4. Structural MRI data acquisition and MEG Co-registration

A 3 T Siemens Prisma scanner equipped with a 32-channel head coil was used to collect high-resolution structural T1-weighted MRI data from each participant (TR: 24.0 ms; TE: 1.96 ms: field of view: 256 mm; slice thickness: 1 mm with no gap; in-plane resolution: 1.0 ×1.0 mm). Structural volumes were aligned parallel to the anterior and posterior commissures and transformed into standardized space. Each participant’s MEG data were co-registered with their MRI data using BESA MRI (Version 2.0). After source imaging (beamformer), each subject’s functional images were also transformed into standardized space using the transform previously applied to the structural MRI volume, and spatially resampled.

2.5. MEG time-frequency decomposition and statistical analysis

For a more detailed description of our methodological approach, see Wiesman and Wilson (2020). Cardiac and ocular artifacts were visually inspected and removed from the data using signal-space projection, which was accounted for during source reconstruction (Uusitalo and Ilmoniemi, 1997). The continuous magnetic time series was divided into 5900 ms epochs, with stimulus presentation (i.e., 5 × 5 grid containing four consonants) defined as 0 ms and the baseline defined as the − 400 to 0 ms time window (i.e., fixation period; Fig. 1). Only correct trials were used for analysis. Epochs containing artifacts were rejected based on a fixed threshold method, which was supplemented with visual inspection. Briefly, the distributions of amplitude and gradient values per participant were computed using all correct trials, and the highest amplitude/gradient trials relative to the total distribution were excluded. Notably, individual thresholds were set for each participant for both amplitude (M = 2145.88 fT/cm, SD = 909.0) and gradient (M = 539.34 fT/(cm*ms), SD = 258.4) due to differences among individuals in head size and sensor proximity, which strongly affect MEG signal amplitude. Note that an average of 87.20 (SD: 12.1) trials per participant remained for further analysis and the number of accepted trials was not significantly correlated with age and did not differ between sexes (see Results).

Artifact-free epochs were then transformed into the time-frequency domain using complex demodulation with a resolution of 1.0 Hz and 50 ms, between 4 and 30 Hz (Kovach and Gander, 2016, Papp and Ktonas, 1977). The resulting spectral power estimations per sensor were averaged over trials to generate time-frequency plots of mean spectral density. These sensor-level data were then normalized per frequency bin using the mean power during the –400 to 0 ms baseline period. The specific time-frequency windows used for imaging were determined by statistical analysis of the sensor-level spectrograms across the entire array of gradiometers. Each data point in the spectrogram was initially evaluated using a mass univariate approach based on the general linear model. To reduce the risk of false-positive results while maintaining reasonable sensitivity, a two-stage procedure was followed to control for Type 1 error. In the first stage, paired-sample t-tests against baseline were conducted on each data point and the output spectrogram of t-values was threshold at p < .05 to define time-frequency bins containing potentially significant oscillatory deviations across all participants. In stage two, time-frequency bins that survived the threshold were clustered with temporally and/or spectrally neighboring bins that were also below the (p < .05) threshold, and a cluster value was derived by summing all of the t-values of all data points in the cluster. Nonparametric permutation testing was then used to derive a distribution of cluster-values, and the significance level of the observed clusters (from stage one) was tested directly using this distribution (Ernst, 2004, Maris and Oostenveld, 2007). For each comparison, 10,000 permutations were computed to build a distribution of cluster values. Based on these analyses, time-frequency windows that contained a significant oscillatory event relative to the permutation testing null were subjected to the beamforming analysis.

2.6. MEG source imaging and statistics

Cortical oscillatory activity was imaged through an extension of the linearly constrained minimum variance vector beamformer (Gross et al., 2001, Hillebrand et al., 2005) using the Brain Electrical Source Analysis (BESA 7.0) software. This approach, commonly referred to as dynamic imaging of coherent sources (DICS), applies spatial filters to time-frequency sensor data to calculate voxel-wise source power for the entire brain volume. The single images are derived from the cross-spectral densities of all combinations of MEG gradiometers averaged over the time-frequency range of interest, and the solution of the forward problem for each location on a 4.0 × 4.0 × 4.0 mm grid specified by input voxel space. Following convention, we computed noise-normalized, source power per voxel in each participant using active (i.e., task) and passive (i.e., baseline) periods of equal duration and bandwidth. Such images are typically referred to as pseudo-t maps, with units (pseudo-t) that reflect noise-normalized power differences (i.e., active vs. passive) per voxel. This generated participant-level pseudo-t maps for each time-frequency-specific response identified in the sensor-level permutation analysis, which was then transformed into standardized space using the transform previously applied to the structural MRI volume and spatially resampled.

Resultant pseudo-t maps were averaged within participants across the time windows used to image neural activity during encoding and maintenance periods, separately. The averaged source maps did not include segments representative of time windows spanning two different phases of the task (e.g., encoding and maintenance). Developmental associations with neural activity were examined via whole-brain voxel-wise correlations with chronological age across the entire sample. Whole-brain correlation maps were then computed separately for males and females, followed by whole-brain bivariate correlation coefficient comparisons computed via Fisher’s Z-transformation. Resultant voxel-wise maps of z-scores represented the normalized difference between males and females in the development-by-oscillatory power (pseudo-t units) relationship. To account for multiple comparisons, a significance threshold of p < .005 was used in all statistical maps to identify significant clusters, in addition to a cluster threshold of 8 contiguous voxels.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and behavioral results

Of the 106 participants who completed the modified Sternberg verbal working memory task, we excluded 15 for poor accuracy (<60 % total trials completed correctly) and 9 for MEG artifacts. Therefore, the final sample analyzed consisted of 82 participants (M = 10.38 years, SD = 2.50; 38 females; 9 left-handed), and age did not significantly differ by sex (t(80) = −.77, p = .44). To ensure that the MEG data of the final sample was not biased by age, we tested for a relationship between age and the number of trials retained for analysis. The number of trials retained was not significantly correlated with age (r = .15, p = .17) and did not significantly differ by sex (t(80) = .69, p = .49). Average accuracy on the verbal working memory task was 84.10 % (SD = 10.24) and average reaction time was 1191.08 ms (SD = 248.15). Accuracy was significantly positively correlated with age such that older participants performed significantly better than younger participants on the task (r = .59, p < .001). Reaction time was significantly negatively correlated with age such that older participants responded significantly faster than younger participants (r = −.65, p < .001; Fig. 1). An independent samples t-test showed that males and females did not significantly differ in accuracy (t(80) = 0.29, p = .77) or reaction time (t(80) = 1.48, p = .14).

3.2. MEG sensor-level and source-level results

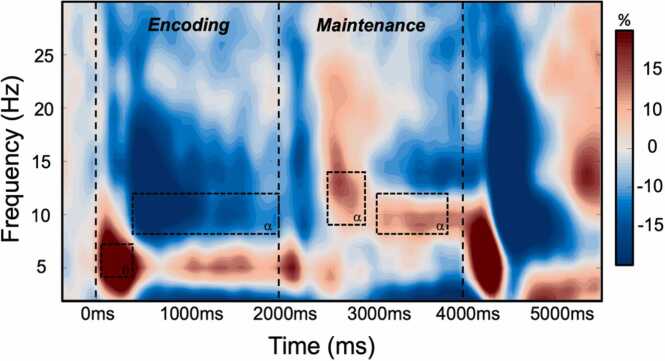

Statistical examination of sensor-level time-frequency spectrograms showed two responses during the encoding period. A significant increase in theta (4–7 Hz; p < .0001, corrected) power relative to baseline began 100 ms after encoding onset and extended until about 500 ms, before gradually dissipating until 2200 ms. A significant decrease in alpha (8–12 Hz; p < .0001, corrected) began 400 ms after encoding onset and extended until 2000 ms. During the maintenance period there was a significant increase in alpha (9–14 Hz) during early maintenance, which began 550 ms after the encoding grid off-set and lasted for about 350 ms (p < .0001, corrected). A narrower alpha response (8–12 Hz) emerged during late maintenance and this lasted until near the end of the maintenance period (Fig. 2; p < .0001, corrected). These alpha and theta responses were divided into 400 ms non-overlapping time bins, with source reconstruction performed on the resultant time-frequency windows of interest. Specifically, we applied a beamformer to the following windows: 4–7 Hz from 100 to 500 ms, 8–12 Hz from 400 to 2000 ms, 9–14 Hz from 2550–2900 ms, and 8–12 Hz from 3100–3900 ms.

Fig. 2.

Grand-averaged MEG sensor-level spectrogram. Grand-averaged time-frequency spectrogram taken from a representative posterior sensor (MEG2043) near parieto-occipital cortices. Time is denoted on the x-axis (0.0 s = encoding onset) and frequency (Hz) is shown on the y-axis. The time-frequency windows used for subsequent beamforming are denoted by the dashed black boxes. The spectrogram is shown in percent power change from baseline, with the color scale shown to the right of the spectrogram.

Average beamformer images across all participants revealed that the early theta response was strongest in bilateral occipital cortices, while the alpha response during encoding began in bilateral occipital regions and extended anteriorly to include left temporal regions as.

encoding progressed. During maintenance, increases in alpha (9–14 Hz) were mainly seen in right parieto-occipital cortices.

3.3. Developmental changes in neural oscillatory responses

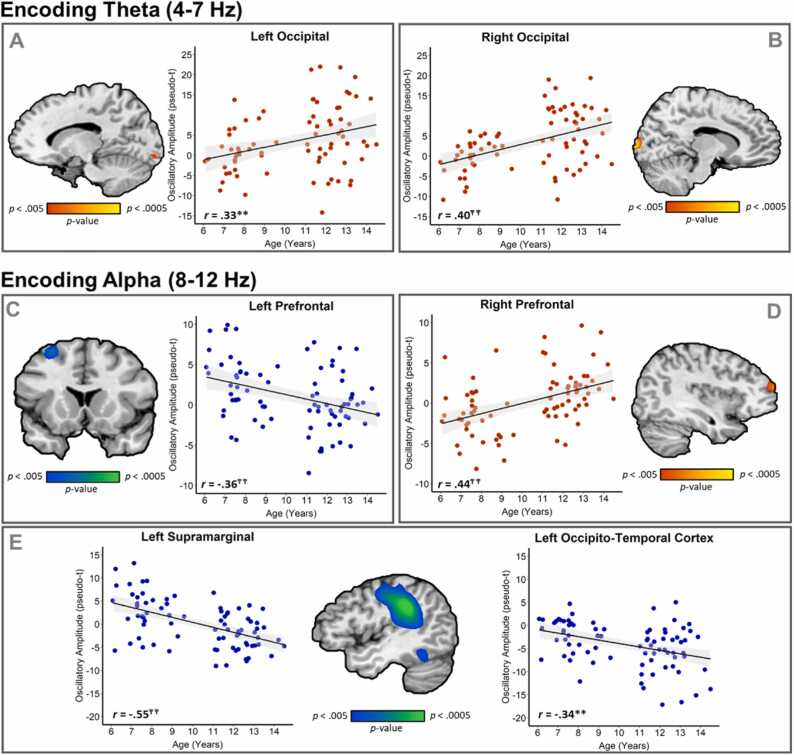

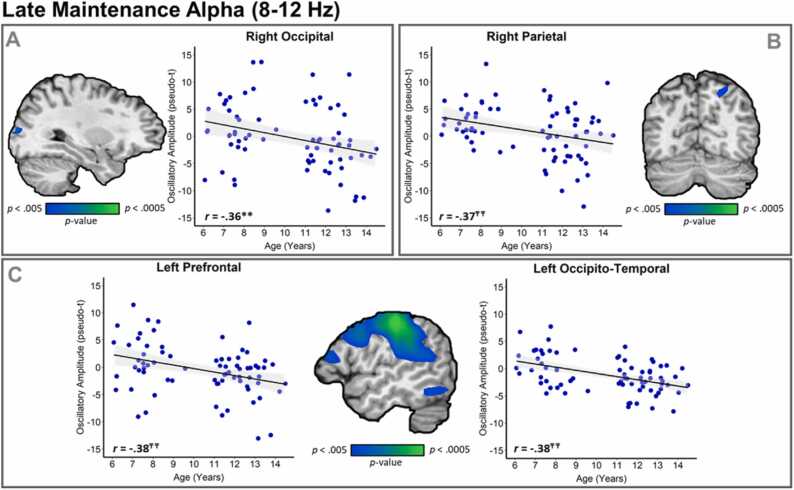

Whole-brain, voxel-wise correlations indicated that theta responses during encoding were positively correlated with age in left (r = .33, p < .005; Fig. 3A) and right (r = .40, p < .001; Fig. 3B) occipital cortices, indicating that older youth had stronger theta responses than their younger peers. Also, during encoding, alpha (8–12 Hz) oscillations became stronger (i.e., more negative) with increasing age in left dorsal prefrontal (r = −.36, p < .001; Fig. 3C), supramarginal (r = −.55, p < .001; Fig. 3E), and occipito-temporal cortices (OTC; r = −.34, p < .005; Fig. 3E). Conversely, alpha oscillations during encoding became weaker with increasing age in the anterior right prefrontal cortex (r = .44, p < .001; Fig. 3D). During late maintenance (3100–3900 ms), alpha oscillations became stronger with increasing age within the right occipital cortices (r = −.36, p < .005; Fig. 4A), right parietal cortices (r = −.37, p < .001; Fig. 4B), left prefrontal cortices (r = −.38, p < .001; Fig. 4C), and left OTC (r = −.38, p < .001; Fig. 4C). Finally, a significant effect of age was also found in the motor cortex, but since the current study was focused on working memory processing, we did not extract peak voxel values or otherwise interpret this finding.

Fig. 3.

Developmental alterations in the neural oscillations serving working memory encoding. Whole-brain correlation maps and associated scatterplots showing the relationship at the peak voxel, with age in years on the x-axes and oscillatory amplitude in pseudo-t units on the y-axes. (A-B) Theta oscillations became stronger with increasing age in the bilateral occipital cortices. (C-E) Alpha oscillations became stronger with increasing age in the left dorsal prefrontal cortices, left supramarginal, and left occipito-temporal cortices, while the opposite pattern was observed in the right anterior prefrontal cortices. **p < .005; ₸ ₸p < .001.

Fig. 4.

Developmental alterations in the neural oscillations serving working memory maintenance. Whole-brain correlation maps and associated scatterplots showing the relationship at the peak voxel, with age in years on the x-axes and oscillatory amplitude in pseudo-t units on the y-axes. (A–C) Alpha oscillations became stronger with increasing age in the right occipital cortices, right parietal, left prefrontal, and left occipito-temporal cortices. **p < .005; ₸ ₸p < .001.

3.4. Sexually-divergent developmental changes in oscillatory strength

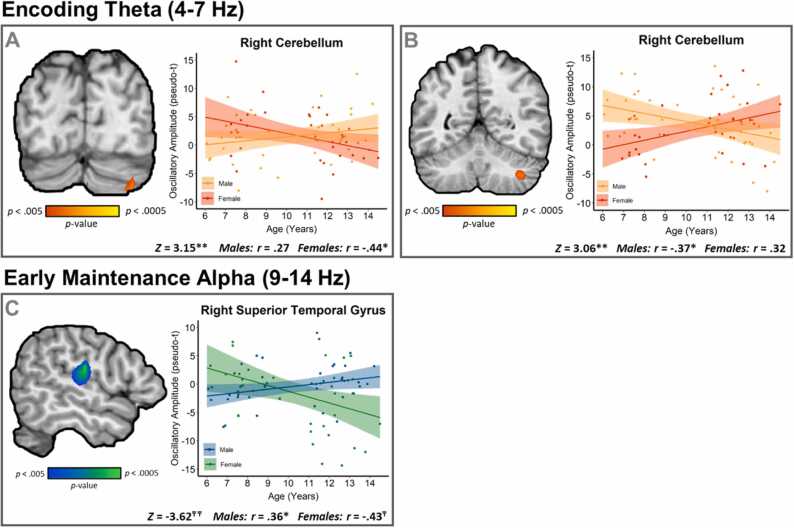

Age-by-sex interaction effects on theta power during encoding were found in two distinct regions of the right cerebellum. More posteriorly, theta oscillations became weaker with increasing age in females, whereas males exhibited the opposite pattern (Z = 3.15, p < .005; Fig. 5A). Anterior to this effect, there was a patch of right cerebellar cortices where theta power became weaker with increasing age in males, with the opposite pattern in females (Z = 3.06, p < .005; Fig. 5B). In addition, age-by-sex interactions were detected in the right superior temporal gyrus during the early maintenance phase, with females exhibiting stronger alpha oscillations with increasing age and males showing the reverse pattern (Z = −3.62, p < .005; Fig. 5C). This same pattern of interactions was also detected in left cerebellar (Z = −3.36, p < .001) and left occipital cortices (Z = −2.91, p < .005).

Fig. 5.

Sexually divergent developmental patterns of neural oscillations serving working memory encoding and maintenance. Whole-brain Fisher-r-to-Z correlation maps and associated scatterplots showing the relationship at the peak voxel, with age in years on the x-axes and oscillatory amplitude in pseudo-t units on the y-axes. (A-B) Theta oscillations became weaker with increasing age in posterior cerebellar cortices among females, and weaker with increasing age in anterior cerebellar cortices among males. (C) Alpha oscillations became stronger with increasing age in right superior temporal cortices among females, but weaker with increasing age among males. *p < .05; ₸p < .01; **p < .005; ₸ ₸p < .001.

4. Discussion

In this study, we used high-density MEG to probe the relationship between chronological age and oscillatory activity supporting working memory, in a sample of 6-to-14-year-old youth. During encoding, we found that age was significantly associated with increased theta power in bilateral occipital cortices and decreased theta in regions of right cerebellar cortices that differed by sex. Also, during encoding, age was associated with stronger alpha oscillations (i.e., decreases in power) in left-lateralized language and executive function regions, such as the left prefrontal, supramarginal, and OTC. Interestingly, the opposite relationship was seen in the right prefrontal cortex, with alpha oscillations becoming weaker with increasing age. During the maintenance phase, alpha oscillations became stronger with increasing age across multiple cortical regions, including occipital, parietal, OTC, and prefrontal cortices. Additionally, in the right supramarginal cortex, males and females showed different developmental trajectories of alpha oscillations during the maintenance phase of working memory. Below, we discuss the implications of these results for our understanding of verbal working memory processing during child and adolescent development.

First, our behavioral findings indicated that older youth performed significantly faster and more accurately than younger youth, which has been reported by previous studies of verbal working memory in developing youth (Embury et al., 2019, Killanin et al., 2022). It is well known that developmental improvements in working memory are non-linear, with rapid gains occurring between late childhood and early adolescence (Blakemore and Choudhury, 2006, Diamond, 2013, Theodoraki et al., 2020). Results from a large-scale study examining executive function from late childhood to early adulthood suggested that a general component of executive function may be the predominant driving force behind age-related, longitudinal changes in working memory and other executive functions (Tervo-Clemmens et al., 2023). Although there were no significant correlations between neural and behavioral data once chronological age was covaried out, our behavioral results may be explained by general improvements in executive function with age that may be implemented across multiple regions and networks that may not directly serve working memory function per se, although future work is needed to fully substantiate this hypothesis.

Regarding our neural data, we found that alpha oscillations during encoding became stronger with increased age in the left dorsal prefrontal, left supramarginal, and left OTC, and these effects extended into the maintenance phase in several brain regions, including the left frontal and left OTC. This aligns with, and extends, previous adult studies (Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson, 2015, Proskovec et al., 2016, Wiesman et al., 2016), which have reported left prefrontal and supramarginal alpha oscillations, beginning during encoding and lasting throughout most of the maintenance phase. This particular pattern of activity has been described within the framework of Baddeley’s multicomponent working memory model (Baddeley, 1992, Baddeley, 2012), where left prefrontal alpha oscillations may reflect activity of the central executive component, responsible for coordinating efforts of various neural regions and allocating attentional resources to relevant stimuli (Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson, 2015, Rottschy et al., 2012, Wiesman et al., 2016). Further, alpha oscillations in the left supramarginal gyrus have been proposed to reflect the activity of the phonological loop, engaging in subvocal rehearsal to refresh stimulus representations from memory decay (Embury et al., 2019, Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson, 2015, Rottschy et al., 2012). Surprisingly, our results also showed that alpha oscillations became weaker in right anterior prefrontal cortices with increased chronological age. These results may indicate increased cortical specialization for verbal working memory processing, with less involvement of right hemispheric prefrontal cortices and increased activity in left hemispheric homologs being more specialized for verbal stimuli (Embury et al., 2019, Proskovec et al., 2016).

The phonological loop is believed to permit short-term maintenance of verbal information via a phonological store that holds speech-related information for a very short time, after which sub-vocal rehearsal is initiated by articulatory control processes to refresh the contents of the phonological store (Baddeley, 1992, Baddeley, 2012). Considering the significant association between age and alpha oscillations in the left supramarginal and OTC, in addition to those in the left prefrontal cortices, our results align with the development of a distributed verbal working memory network. The left supramarginal gyrus has long been known as a critical hub for language processing, including phonological decoding and articulatory rehearsal (Price, 2012, Wilson et al., 2005a, Wilson et al., 2005b, Wilson et al., 2007). Further, the OTC houses the visual word form area (Dehaene and Cohen, 2011), an area central to visual processing during reading which has been shown to be preferentially activated in response to printed words as opposed to symbols or checkerboard patterns (Di Pietro et al., 2023). Taking the extant adult MEG and fMRI working memory literature into account, we can see that the observed changes in alpha activity within this sample align with the maturation of integral components of the working memory network with increasing age, across males and females.

Properly encoding visual stimuli necessitates involvement of the early visual cortices, thus the increased bilateral occipital theta power with age may suggest maturation of early visual processing among older youth. Adult studies reporting increased occipital theta activity have suggested that it is associated with attentional exploration, as a necessary component of early visual processing (Dugué and VanRullen, 2017, Muthukumaraswamy et al., 2010, Wiesman et al., 2017, Wiesman et al., 2018, Wiesman and Wilson, 2019). Increased occipital theta activity during a visuospatial task has also been associated with increased age in a sample of youth (Killanin et al., 2020). Beyond visual cortices, we also found sex-by-age interactions in theta oscillatory responses in the cerebellum, with males showing decreases with age in more anterior regions of the right cerebellum, and females showing decreases with age in more posterior cerebellar cortices. This may reflect the density of sex steroid receptors in the cerebellum, especially during this developmental stage (Lenroot and Giedd, 2010, McEwen and Milner, 2017), as estrogens have been shown to play a role in Purkinje cell dendritic growth, spine and synapse development in the cerebellum (Abel et al., 2011, Hedges et al., 2012). Previous work studying the cerebellum’s functional role in working memory has suggested that it aids in computing the difference between actual and intended phonological rehearsal, eventually updating communications to frontal cortices that will aid the phonological loop (Desmond et al., 1997). At least one study has reported load-dependent increases in cerebellar activation, suggesting that it reflected increased input from prefrontal cortices that were involved in the articulatory control system of the phonological loop (O'Hare et al., 2008). Previous MEG studies have reported right cerebellar alpha oscillations during the maintenance phase of working memory in adults (Heinrichs‐Graham and Wilson, 2015, Proskovec et al., 2016, Wilson et al., 2017) and sex differences in right cerebellar alpha power during maintenance in developing youth (Embury et al., 2019), emphasizing its importance for maintaining stimuli.

During maintenance, increased age was significantly associated with stronger alpha oscillations (i.e., more negative) in the right occipital and right parietal cortices, which was surprising because the adult literature has shown the opposite pattern (i.e., alpha inhibition) in parieto-occipital regions. Some have suggested that such alpha responses reflect the inhibition of visual pathways that acts to block visual input when there is a greater chance of memory decay (Bonnefond and Jensen, 2012, Händel et al., 2011, Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson, 2015, Jensen, 2002). Further, one analysis in adults focused on the time course of parieto-occipital alpha, and found that increased alpha power strongly dissipated during the final time bin before retrieval, which the authors suggested may reflect decreased inhibition as the processes needed for retrieval are initiated (Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson, 2015). In our sample, most of the younger participants exhibited increased alpha power relative to baseline (i.e., alpha inhibition), but among the older youth some displayed increased alpha power while others exhibited decreased alpha relative to baseline. We suggest that the older participants who displayed decreased alpha power across this time span of 800 ms preceding retrieval may have initiated their retrieval processing earlier, thus releasing their inhibitory processes early in the 800 ms imaging window. Being that this task was four-load, it is likely that older youths found this task to be less difficult and were able to release their inhibitory processing earlier. Future work should probe the effects of alpha power latency in parieto-occipital cortices and its relationship to behavioral performance and memory load, as previous studies using a six-load task have reported a sustained alpha increase in adults (Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson, 2015, Wilson et al., 2017).

Before closing, we must acknowledge a few limitations of our study. This analysis utilized data from only one time point of an accelerated longitudinal sample, without significant representation of 9- and 10-year-old participants. Thus, we were unable to conduct within-subjects analyses or have a continuous age range from 6 to 14 years old. Additionally, because we did not find behavioral correlations with alpha or theta power in regions that exhibited significant associations with age, we were unable to definitively say that patterns of change directly contributed to improved performance with age. Future studies would benefit from utilizing multiple time points in a longitudinal design with participants at every age in the range of interest, as this may offer a wider view of the developmental processes at play. Future studies will also benefit from probing the association between age and oscillatory activity within other frequency ranges. For example, studies have reported developmental changes in gamma activity during maintenance (McKeon et al., 2023), and interactions between alpha/beta and gamma oscillations have been proposed in models of working memory (Miller et al., 2018), but the developmental trajectory of such interactions are poorly understood. Overall, with our use of high-density MEG and dynamic functional mapping, we have identified developmentally sensitive regions of a distributed network supporting working memory processing. We identified age-related changes in theta and alpha signatures of encoding and maintenance and provided a foundation for the further delineation of developmental changes in verbal working memory-related oscillatory activity. While our findings were consistent with adult and developmental accounts, findings in youth as young as six years old have not been previously described, which therefore further extend our understanding of this critical cognitive function toward early childhood.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Julia M. Stephen: Data curation, Funding acquisition. Tony W. Wilson: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Giorgia Picci: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision. Elizabeth Heinrichs-Graham: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision. Thomas W. Ward: Formal analysis. Christine M. Embury: Conceptualization, Supervision. Abraham Killanin: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Vince D. Calhoun: Funding acquisition, Data curation. Yu-Ping Wang: Funding acquisition, Data curation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments and funding support

This research was supported by grants R01-MH121101 (TWW), P20-GM144641 (TWW), and F30-MH130150 (ADK) from the National Institutes of Health of the United States of America. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The data presented in this manuscript have not been published or presented elsewhere.

Data statement

The data used in this article will be made publicly available through the COINS framework at the completion of the study (https://coins.trendcenter.org/).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abel J.M., Witt D.M., Rissman E.F. Sex differences in the cerebellum and frontal cortex: roles of estrogen receptor alpha and sex chromosome genes. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;93(4):230–240. doi: 10.1159/000324402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre J., Picchioni M., Zhang R., Toulopoulou T. Working memory circuit as a function of increasing age in healthy adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Neuroimage Clin. 2016;12:940–948. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attout L., Ordonez Magro L., Szmalec A., Majerus S. The developmental neural substrates of item and serial order components of verbal working memory. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2019;40(5):1541–1553. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A. Working memory. Science. 1992;255(5044):556–559. doi: 10.1126/science.1736359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A. Working memory: theories, models, and controversies. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012;63(1):1–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore S.-J., Choudhury S. Development of the adolescent brain: implications for executive function and social cognition. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2006;47(3-4):296–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefond M., Jensen O. Alpha oscillations serve to protect working memory maintenance against anticipated distracters. Curr. Biol. 2012;22(20):1969–1974. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes M.J., Wood J.R., Stevenson C.M., Zumer J.M., White T.P., Liddle P.F., Morris P.G. Changes in brain network activity during working memory tasks: a magnetoencephalography study. NeuroImage. 2011;55(4):1804–1815. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh J.F., Frank M.J. Frontal theta as a mechanism for cognitive control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014;18(8):414–421. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S., Cohen L. The unique role of the visual word form area in reading. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011;15(6):254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond J.E., Gabrieli J.D., Wagner A.D., Ginier B.L., Glover G.H. Lobular patterns of cerebellar activation in verbal working-memory and finger-tapping tasks as revealed by functional MRI. J. Neurosci. 1997;17(24):9675–9685. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.17-24-09675.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro S.V., Karipidis I.I., Pleisch G., Brem S. Neurodevelopmental trajectories of letter and speech sound processing from preschool to the end of elementary school. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2023;61 doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2023.101255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A. Executive functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013;64(1):135–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugué L., VanRullen R. Transcranial magnetic stimulation reveals intrinsic perceptual and attentional rhythms. Front. Neurosci. 2017;11:154. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embury C.M., Wiesman A.I., Proskovec A.L., Heinrichs-Graham E., McDermott T.J., Lord G.H., Brau K.L., Drincic A.T., Desouza C.V., Wilson T.W. Altered brain dynamics in patients with type 1 diabetes during working memory processing. Diabetes. 2018;67(6):1140–1148. doi: 10.2337/db17-1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embury C.M., Wiesman A.I., Proskovec A.L., Mills M.S., Heinrichs-Graham E., Wang Y.-P., Calhoun V.D., Stephen J.M., Wilson T.W. Neural dynamics of verbal working memory processing in children and adolescents. NeuroImage. 2019;185:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M.D. Permutation methods: a basis for exact inference. Stat. Sci. 2004;19(4):676–685. doi: 10.1214/088342304000000396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fellrath J., Mottaz A., Schnider A., Guggisberg A.G., Ptak R. Theta-band functional connectivity in the dorsal fronto-parietal network predicts goal-directed attention. Neuropsychologia. 2016;92:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole S.E., Pickering S.J., Ambridge B., Wearing H. The structure of working memory from 4 to 15 years of age. Dev. Psychol. 2004;40(2):177–190. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole S.E., Pickering S.J., Knight C., Stegmann Z. Working memory skills and educational attainment: evidence from national curriculum assessments at 7 and 14 years of age. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2004;18(1):1–16. doi: 10.1002/acp.934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J., Kujala J., Hamalainen M., Timmermann L., Schnitzler A., Salmelin R. Dynamic imaging of coherent sources: studying neural interactions in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98(2):694–699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Händel B.F., Haarmeier T., Jensen O. Alpha oscillations correlate with the successful inhibition of unattended stimuli. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2011;23(9):2494–2502. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges V.L., Ebner T.J., Meisel R.L., Mermelstein P.G. The cerebellum as a target for estrogen action. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33(4):403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs-Graham E., Wilson T.W. Spatiotemporal oscillatory dynamics during the encoding and maintenance phases of a visual working memory task. Cortex. 2015;69:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs-Graham E., Walker E.A., Eastman J.A., Frenzel M.R., Joe T.R., McCreery R.W. The impact of mild-to-severe hearing loss on the neural dynamics serving verbal working memory processing in children. Neuroimage Clin. 2021;30 doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs-Graham E., Walker E.A., Eastman J.A., Frenzel M.R., McCreery R.W. Amount of hearing aid use impacts neural oscillatory dynamics underlying verbal working memory processing for children with hearing loss. Ear Hear. 2022;43(2):408–419. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000001103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs‐Graham E., Wilson T.W. Spatiotemporal oscillatory dynamics during the encoding and maintenance phases of a visual working memory task. Cortex. 2015;69:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillebrand A., Singh K.D., Holliday I.E., Furlong P.L., Barnes G.R. A new approach to neuroimaging with magnetoencephalography. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2005;25(2):199–211. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O. Oscillations in the alpha band (9-12 Hz) increase with memory load during retention in a short-term memory task. Cereb. Cortex. 2002;12(8):877–882. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.8.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O., Tesche C.D. Frontal theta activity in humans increases with memory load in a working memory task. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2002;15(8):1395–1399. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killanin A.D., Wiesman A.I., Heinrichs-Graham E., Groff B.R., Frenzel M.R., Eastman J.A., Wang Y.P., Calhoun V.D., Stephen J.M., Wilson T.W. Development and sex modulate visuospatial oscillatory dynamics in typically-developing children and adolescents. NeuroImage. 2020;221 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killanin A.D., Embury C.M., Picci G., Heinrichs-Graham E., Wang Y.-P., Calhoun V.D., Stephen J.M., Wilson T.W. Trauma moderates the development of the oscillatory dynamics serving working memory in a sex-specific manner. Cereb. Cortex. 2022 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhac008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: a review and analysis. Brain Res. Rev. 1999;29(2-3):169–195. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach C.K., Gander P.E. The demodulated band transform. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2016;261:135–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H., Reiss A.L., Menon V. Neural basis of protracted developmental changes in visuo-spatial working memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99(20):13336–13341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162486399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenroot R.K., Giedd J.N. Sex differences in the adolescent brain. Brain Cogn. 2010;72(1):46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris E., Oostenveld R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2007;164(1):177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott T.J., Badura-Brack A.S., Becker K.M., Ryan T.J., Khanna M.M., Heinrichs-Graham E., Wilson T.W. Male veterans with PTSD exhibit aberrant neural dynamics during working memory processing: an MEG study. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016;41(4):251–260. doi: 10.1503/jpn.150058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B.S., Milner T.A. Understanding the broad influence of sex hormones and sex differences in the brain. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017;95(1-2):24–39. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeon S.D., Calabro F., Thorpe R.V., de la Fuente A., Foran W., Parr A.C., Jones S.R., Luna B. Age-related differences in transient gamma band activity during working memory maintenance through adolescence. NeuroImage. 2023;274 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2023.120112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E.K., Lundqvist M., Bastos A.M. Working memory 2.0. Neuron. 2018;100(2):463–475. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumaraswamy S.D., Singh K.D., Swettenham J.B., Jones D.K. Visual gamma oscillations and evoked responses: variability, repeatability and structural MRI correlates. NeuroImage. 2010;49(4):3349–3357. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hare E.D., Lu L.H., Houston S.M., Bookheimer S.Y., Sowell E.R. Neurodevelopmental changes in verbal working memory load-dependency: an fMRI investigation. NeuroImage. 2008;42(4):1678–1685. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østby Y., Tamnes C.K., Fjell A.M., Walhovd K.B. Morphometry and connectivity of the fronto-parietal verbal working memory network in development. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(14):3854–3862. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp N., Ktonas P. Critical evaluation of complex demodulation techniques for the quantification of bioelectrical activity. Biomed. Sci. Instrum. 1977;13:135–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price C.J. A review and synthesis of the first 20 years of PET and fMRI studies of heard speech, spoken language and reading. NeuroImage. 2012;62(2):816–847. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proskovec A.L., Heinrichs‐Graham E., Wilson T.W. Aging modulates the oscillatory dynamics underlying successful working memory encoding and maintenance. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2016;37(6):2348–2361. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proskovec A.L., Wiesman A.I., Heinrichs-Graham E., Wilson T.W. Beta oscillatory dynamics in the prefrontal and superior temporal cortices predict spatial working memory performance. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26863-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proskovec A.L., Wiesman A.I., Heinrichs-Graham E., Wilson T.W. Load effects on spatial working memory performance are linked to distributed alpha and beta oscillations. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2019;40(12):3682–3689. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramnani N., Owen A.M. Anterior prefrontal cortex: insights into function from anatomy and neuroimaging. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5(3):184–194. doi: 10.1038/nrn1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravizza S.M., Delgado M.R., Chein J.M., Becker J.T., Fiez J.A. Functional dissociations within the inferior parietal cortex in verbal working memory. NeuroImage. 2004;22(2):562–573. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M.D., Martinez S.A., Rapuano K.M., Conley M.I., Cohen A.O., Cornejo M.D., Hagler D.J., Jr, Meredith W.J., Anderson K.M., Wager T.D., Feczko E., Earl E., Fair D.A., Barch D.M., Watts R., Casey B.J. Behavioral and neural signatures of working memory in childhood. J. Neurosci. 2020;40(26):5090–5104. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2841-19.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottschy C., Langner R., Dogan I., Reetz K., Laird A.R., Schulz J.B., Fox P.T., Eickhoff S.B. Modelling neural correlates of working memory: a coordinate-based meta-analysis. NeuroImage. 2012;60(1):830–846. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherf K.S., Sweeney J.A., Luna B. Brain basis of developmental change in visuospatial working memory. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2006;18(7):1045–1058. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.7.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taulu S., Simola J. Spatiotemporal signal space separation method for rejecting nearby interference in MEG measurements. Phys. Med Biol. 2006;51(7):1759–1768. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/7/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taulu S., Simola J., Kajola M. Applications of the signal space separation method. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2005;53(9):3359–3372. doi: 10.1109/tsp.2005.853302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tervo-Clemmens B., Calabro F.J., Parr A.C., Fedor J., Foran W., Luna B. A canonical trajectory of executive function maturation from adolescence to adulthood. Nat. Commun. 2023;14(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42540-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoraki T.E., McGeown S.P., Rhodes S.M., Macpherson S.E. Developmental changes in executive functions during adolescence: a study of inhibition, shifting, and working memory. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2020;38(1):74–89. doi: 10.1111/bjdp.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusitalo M.A., Ilmoniemi R.J. Signal-space projection method for separating MEG or EEG into components. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 1997;35(2):135–140. doi: 10.1007/bf02534144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesman A.I., Wilson T.W. The impact of age and sex on the oscillatory dynamics of visuospatial processing. NeuroImage. 2019;185:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesman A.I., Wilson T.W. Attention modulates the gating of primary somatosensory oscillations. NeuroImage. 2020;211 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesman A.I., Heinrichs-Graham E., McDermott T.J., Santamaria P.M., Gendelman H.E., Wilson T.W. Quiet connections: reduced fronto-temporal connectivity in nondemented Parkinson's Disease during working memory encoding. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2016;37(9):3224–3235. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesman A.I., Heinrichs‐Graham E., Proskovec A.L., McDermott T.J., Wilson T.W. Oscillations during observations: Dynamic oscillatory networks serving visuospatial attention. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017;38(10):5128–5140. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesman A.I., O'Neill J., Mills M.S., Robertson K.R., Fox H.S., Swindells S., Wilson T.W. Aberrant occipital dynamics differentiate HIV-infected patients with and without cognitive impairment. Brain. 2018;141(6):1678–1690. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T.W., Leuthold A.C., Lewis S.M., Georgopoulos A.P., Pardo P.J. Cognitive dimensions of orthographic stimuli affect occipitotemporal dynamics. Exp. Brain Res. 2005;167(2):141–147. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0011-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T.W., Leuthold A.C., Lewis S.M., Georgopoulos A.P., Pardo P.J. The time and space of lexicality: a neuromagnetic view. Exp. Brain Res. 2005;162(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-2099-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T.W., Leuthold A.C., Moran J.E., Pardo P.J., Lewis S.M., Georgopoulos A.P. Reading in a deep orthography: neuromagnetic evidence for dual-mechanisms. Exp. Brain Res. 2007;180(2):247–262. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0852-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T.W., Proskovec A.L., Heinrichs-Graham E., O'Neill J., Robertson K.R., Fox H.S., Swindells S. Aberrant neuronal dynamics during working memory operations in the aging HIV-infected brain. Sci. Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep41568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.