Abstract

Many bacterial pathogens, including pathogenic neisseriae, can use heme as an iron source for growth. To study heme utilization by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, two heme biosynthetic mutants were constructed, one with a mutation in hemH (the gene encoding ferrochelatase) and one with a mutation in hemA (the gene encoding γ-glutamyl tRNA reductase). The hemH mutant failed to grow without an exogenous supply of heme or hemoglobin, whereas the hemA mutant failed to grow unless heme, hemoglobin, or heme precursors were present. Growth of the mutants with hemoglobin required expression of the hemoglobin receptor (HpuAB) and was TonB dependent. However, growth with heme required neither HpuAB nor TonB. An fbpA mutant grew normally when either heme or hemoglobin was present in the medium. The heme biosynthetic mutants showed reduced intracellular survival, compared to the parent strain, within A-431 endocervical epithelial cell cultures. These studies demonstrate that in addition to synthesizing their own heme, N. gonorrhoeae strains are able to internalize and utilize exogenous heme independently of FbpA but appear unable to obtain heme from within epithelial cells for growth.

Gonorrhea, a sexually transmitted disease caused by the human pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae, primarily infects columnar epithelial mucosal surfaces including the urethra, endocervix, rectum, and oropharynx. It is a major cause of pelvic inflammatory disease in women and acts as a cofactor for the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (23, 41). Gonococci can grow within epithelial cells and are capable of invading the epithelial barrier and disseminating via the bloodstream to multiple sites, including the cerebrospinal fluid, skin, and joints (32). Therefore, N. gonorrhoeae must be able to obtain nutrients from a diverse range of environments.

Nearly all bacteria require iron as a nutrient for growth, and the ability of pathogens to obtain iron from their host is a major virulence determinant (33, 43). Gram-negative bacteria, including N. gonorrhoeae, have evolved elaborate iron assimilation systems involving outer membrane receptor proteins that are capable of recognizing and binding different sources of iron (19). These receptors are usually TonB dependent and are upregulated by low intracellular levels of iron through the repressor protein ferric uptake regulator (Fur) (2, 7, 53).

Many bacteria synthesize and secrete siderophores that chelate iron from the environment. Receptors bind iron-containing siderophores, which are transported through the periplasm and inner membrane by specific transporter systems (44, 47). Gonococci are unable to synthesize siderophores but take advantage of extracellular iron transport proteins made by their host (11). They utilize iron from human transferrin and lactoferrin through the TonB-dependent receptors transferrin binding receptor (TbpAB) and lactoferrin binding receptor (LbpAB), respectively (5, 11).

Although soluble transport proteins and siderophores provide a means of obtaining iron for pathogens, heme remains the largest potential source of iron from the host (38, 42). Heme is bound in hemoproteins to form cytochromes, catalase, hemoglobin (in erythrocytes), myeloperoxidase (in granulocytes), and myoglobin (in myocytes). Hemoproteins and heme also enter the extracellular space following increased cell turnover and breakdown, especially when inflammation and cell damage are present (38). In addition to providing a source of iron, heme is essential for several aerobic processes in bacteria (54). It acts as a cofactor for many of the cytochromes required for oxidative phosphorylation and, in the form of catalase, provides a defense against hydrogen peroxide, a by-product of this process (59). Accordingly, many pathogens, including gonococci, have retained the ability to make heme while developing means of acquiring heme from their host. Pathogenic neisseriae can utilize exogenous heme, hemoglobin, and hemoglobin-haptoglobin as the sole iron source in vitro (9, 30, 36, 50).

Gram-negative pathogens have adopted different strategies for obtaining heme. Some secrete hemophores, which are analogous to siderophores but specifically bind heme or heme-hemopexin (10, 18). Alternatively, heme or heme bound to carrier proteins can be utilized via heme receptors, as occurs with Yersinia spp., Plesiomonas shigelloides, Shigella dysenteriae, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and Vibrio cholerae (12, 21, 22, 39). Hemoglobin is a rich source of iron and heme, since there are four heme moieties contained within a single hemoglobin molecule. Some pathogens, including Haemophilus influenzae, H. ducreyi, N. meningitidis, and N. gonorrhoeae, have TonB-dependent receptors that recognize hemoglobin (9, 16, 49).

It is unclear whether pathogenic neisseriae internalize the heme ring intact (14, 50). One model has suggested that iron may be stripped from heme and transported to the inner membrane by the periplasmic ferric iron binding protein (FbpA) (14). FbpA is used to shuttle iron from transferrin and lactoferrin through the periplasmic space, where it is transported to the cytoplasm by an inner membrane permease/nucleotide binding protein complex (FbpBC) (1, 8, 37). However, a hitA (fbpA) nonpolar isogenic mutant of H. influenzae can still grow with heme as the sole source of iron (26). The fbpABC genes of N. gonorrhoeae and the analogous hitABC genes of H. influenzae are all located on a single operon (1, 26).

The pathways for heme synthesis in both nonplant eukaryotes and members of the beta and gamma subdivisions of the Proteobacteria (e.g., E. coli) are well characterized (3). The main difference occurs with the initial step of synthesizing δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA). Mitochondria use succinyl coenzyme A and glycine as the substrates for the enzyme ALA synthetase to make ALA, whereas members of the beta- and gamma-Proteobacteria use γ-glutamyl tRNA as substrate for the enzyme γ-glutamyl tRNA reductase (HemA) to make glutamate-1-semialdehyde. Glutamate-1-semialdehyde transferase (HemL) converts glutamate-1-semialdehyde to ALA. The remaining steps of heme synthesis are similar, including the final step of inserting iron into the protoporphyrin IX ring by the enzyme ferrochelatase (HemH) to make heme.

Among E. coli K-12 strains, which lack a heme receptor, hemH isogenic mutants grow poorly because they are unable to utilize exogenous heme or heme precursors for aerobic growth. However, E. coli hemA isogenic mutants grow well when rescued by exogenous ALA, which bypasses the block in ALA synthesis. In fact, a E. coli hemA mutant has been used successfully as a model to demonstrate the function of heterologous heme and hemoglobin receptors, by recombinant expression, to restore growth aerobically in the presence of heme or hemoglobin (50).

For this study, we created mutants with mutations in the heme biosynthetic pathway (hemA and hemH) and in the periplasmic iron transporter (fbpA). Characterization of these mutants enabled us to determine whether exogenous heme can be utilized as a source of both iron and heme and to better elucidate the pathway for entry of heme. The heme mutants were also used to determine whether intracellular heme (from epithelial cells) could support the growth of gonococci.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used for this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria broth (LB) medium containing appropriate antibiotics for selection. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml, kanamycin, 60 μg/ml; and spectinomycin, 80 μg/ml. Chloramphenicol was used at 30 μg/ml for E. coli and at 1 and 10 μg/ml for gonococcal strains FA1090 and MS11, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and Phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| N. gonorrhoeae strains | ||

| FA1090 | 13 | |

| MS11 | 35 | |

| FA6973 | FA1090 hemH::CAT (Cmr) | This study |

| FA6974 | FA1090 hemA::Ω (Smr Spr) | This study |

| FA6976 | MS11 hemA::Ω (Smr Spr) | This study |

| FA6977 | MS11 hemH::CAT (Cmr) | This study |

| FA6978 | FA1090 fbpA::Ω (Smr Spr) | This study |

| FA6979 | FA1090 fbpA::aphA-3 (Kmr) | This study |

| FA6982 | FA1090 hpuA::Ω (Smr Spr) | 9 |

| FA7006 | FA1090 tonB::Ω (Smr Spr) | This study |

| FA7007 | FA7006 but hemH::CAT (Cmr) | This study |

| FA7008 | FA6982 but hemH::CAT (Cmr) | This study |

| E. coli strain | ||

| DH5αMCR | Bethesda Research Laboratories | |

| Plasmid | ||

| pCRII | Vector for inserting PCR product | Invitrogen Corp. |

| pUC18K | Source for aphA-3 (Kmr) cassette | 34 |

| pHP45Ω | Source for Ω (Spr Smr) cassette | 45 |

| pNC40 | Source for CAT (Cmr) cassette | 52 |

| pUC9GCU | Contains gonococcal uptake sequence | 17 |

| PUNCH173 | Plasmid containing tonB::Ω | 4 |

| pUNCH1303 | pCRII with hemH PCR insert | This study |

| pUNCH1304 | pUNCH1303 with CAT cassette from pNC40 | This study |

| pUNCH1305 | pCRII with hemA PCR insert | This study |

| pUNCH1306 | pUNCH1305 with Ω cassette from pHP45Ω | This study |

| pUNCH1322 | pUC9GCU with fbpA PCR insert | This study |

| pUNCH1323 | pUNCH1322 with aphA-3 cassette from pUC18K | This study |

| pUNCH1324 | pUNCH1322 with Ω cassette from pHP45Ω | This study |

N. gonorrhoeae was cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 on gonococcal base (GCB) agar medium (Difco Laboratories) containing Kellogg’s supplement I (24). Additional heme, hemoglobin, ALA, or Kellog’s supplement II (iron nitrate) was added where appropriate. Stock solutions of hemin (5 mg/ml) and hemoglobin (10 mg/ml) were prepared by dissolving hemin (Sigma) in 0.1 N NaOH and human hemoglobin (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline PBS (pH 7.4), respectively. For iron-limiting conditions, desferrioxamine B (Desferal; Ciba-Geigy) was added to a final concentration of 50 μM.

The growth phenotype was assessed by spreading 100 μl of a gonococcal suspension in GCB broth, diluted 1/100 from an initial optical density at 600 nm of 0.4, onto GCB agar (with and without desferal). Wells (0.6 cm in diameter) were cut into the agar, and 60 μl of the following substrates were added: 2 mg of protoporphyrin IX per ml, 25 mg of human transferrin (30% iron saturated) per ml, 10 mM iron citrate, 10 mM iron chloride, 1 mg of heme per ml, and 10 mg of hemoglobin per ml. All the reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. unless otherwise stated. For growth experiments in broth, gonococcal strains were resuspended in 10 ml of GCB broth (with and without various amounts of heme) to a Klett reading of 20 and incubated at 37°C in a shaker incubator under 5% CO2.

One consideration for characterizing a hemH mutant was that excessive buildup of protoporphyrin IX could have a deleterious effect on its phenotype (60). In gonococci, the potential for porphyrin toxicity may be limited if exogenous heme is internalized, leading to feedback inhibition of porphyrin synthesis by reducing the levels of HemA (58). Nevertheless, manipulations of the gonococcal mutants were performed with colonies less than 24 h old and under reduced light conditions unless absolutely necessary.

PCR.

The design of the hemH and hemA PCR primers was based on analysis of sequencing contiguities released from the University of Oklahoma Gonococcal Genome Sequencing Project Web site (46). Part of the hemH gene was amplified with primers HEMH1 (5′CGCAAACCGCATTACCTGAT3′) and HEMH2 (5′ATTGGCTTTGGAACGATACG3′). The hemA gene was amplified with primers HEMA1 (5′AATCAAACCTGCCAATCCT3′) and HEMA2 (5′TCTTCTTCCCCCGCCTTAT3′). For PCR amplification of fbpA, primers containing incorporated restriction sites for BamHI or EcoRI (underlined) were used: FBP1 (5′CGGGATCCTATGAAAACATCTATCCGATACGCACTG3′) and FBP2 (5′GGAATTCAGGCAGGGTAAGCGGCAGGGCGATCAG3′). The template for PCR was chromosomal DNA extracted from strain FA1090 (genomic DNA kit; Qiagen) (13). The PCR conditions were as follows: 94°C at 3 min for 1 cycle; 94°C for 45 s, 58°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 3 min for 30 cycles; and 72°C for 3 min for 1 cycle. Genotypic confirmation of the plasmid constructs and isogenic mutants was obtained by analysis of PCR products from appropriate purified plasmid DNA (plasmid midi-prep kit; Qiagen) and phenol-chloroform extracted chromosomal DNA (see Fig. 1 and 2).

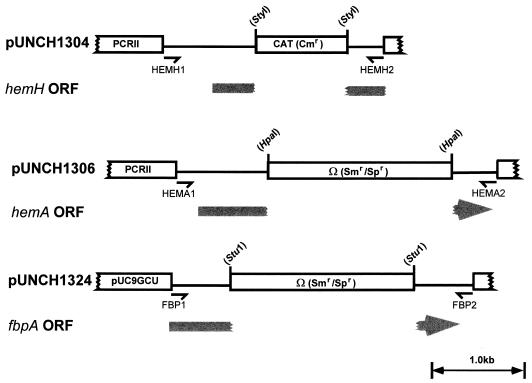

FIG. 1.

Construction of pUNCH1304, pUNCH1306, and pUNCH1324. A single line indicates a PCR product, and a box represents either the antibiotic cassette or plasmid vector. Only part of the plasmid vector is shown. The open reading frame (ORF) and direction of transcription for the relevant gonococcal gene, interrupted by insertion of the antibiotic cassette, are indicated in gray. The PCR fragment for hemH contains only a portion of the hemH gene. The restriction sites used to linearize the plasmid and insert the antibiotic cassette are shown in parentheses.

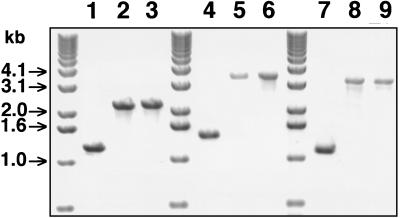

FIG. 2.

Ethidium bromide-stained 0.7% agarose gel showing the PCR products from plasmid and gonococcal chromosomal DNA following electrophoresis. Lanes: 1, FA1090; 2, pUNCH1304; 3, FA6973 (FA1090 hemH::CAT); 4, FA1090; 5, pUNCH1306; 6, F6974 (FA1090 hemA::Ω); 7, FA1090; 8, pUNCH1324; 9, FA6978 (FA1090 fbpA::Ω). Oligonucleotide primers for PCR were HEMH1 and HEMH2 for lanes 1 to 3, HEMA1 and HEMA2 for lanes 4 to 6, and FBP1 and FBP2 for lanes 7 to 9. DNA molecular size markers are shown in kilobases.

Mutagenesis and gonococcal transformation.

Plasmids containing gonococcal DNA insert were constructed as follows (Table 1; also see Fig. 1). The hemH and hemA PCR products were ligated into plasmid vector PCRII to generate pUNCH 1303 and pUNCH 1305, respectively (TA cloning kit; Invitrogen). To generate pUNCH1322, PCR-amplified DNA from fbpA and DNA from the gonococcal uptake sequence vector pUC9GCU were double digested with BamHI and EcoRI, gel purified, and directionally ligated (17). All the plasmids were transformed into competent E. coli DH5α MCR cells (Bethesda Research Laboratories), and positive clones were selected either by growth on LB ampicillin medium (pUNCH1322) or by the presence of a white phenotype on isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopy-ranoside (IPTG/X-Gal) LB medium containing ampicillin and kanamycin (pUNCH1303 and pUNCH1305).

DNA cassettes containing antibiotic resistance genes were prepared as follows. pHP45Ω was digested with SmaI to release a 2-kb Ω DNA fragment (Smr Spr), which was isolated by gel purification (45). Similarly, a 1-kb cassette containing the gene for chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) was isolated from pNC40 after digestion with BglII (52). A 1-kb aphA-3 (Kmr) cassette was obtained from pUC18K by double digestion with EcoRI and BamHI followed by gel purification (34). Both the aphA-3 and CAT fragment were treated with Klenow enzyme and deoxynucleoside triphosphates to blunt the 5′ and 3′ ends.

The antibiotic resistance gene cassettes were inserted into the PCR-derived, cloned gonococcal DNA by linearizing the plasmids as follows. pUNCH1303 was linearized with StyI (partial digest), pUNCH1305 was linearized with HpaI, and pUNCH1322 was linearized with StuI (see Fig. 1). Since StyI digestion did not produce blunt ends, linearized pUNCH1303 was treated with Klenow enzyme plus deoxynucleoside triphosphates to blunt the ends. The Ω cassette was ligated to linearized pUNCH1305 and pUNCH1322 to generate pUNCH1306 and pUNCH1324, respectively. The CAT cassette was ligated to pUNCH1303 to generate pUNCH1304. The 1-kb aphA-3 cassette was inserted into the StuI-digested pUNCH1322 to generate pUNCH1323. The orientation of the aphA-3 cassette was confirmed by restriction endonuclease analysis. All ligation reactions were performed in the presence of T4 DNA ligase. Plasmids pUNCH1304, pUNCH1306, pUNCH1323, and pUNCH1324 (containing the antibiotic cassette inserts) were transformed into E. coli DH5α and selected on LB agar containing appropriate antibiotics. The orientation and size of the cloned DNA were confirmed by restriction endonuclease analysis before transformation into N. gonorrhoeae.

The plasmids were used to transform and construct N. gonorrhoeae mutants by allelic exchange as follows. A GCB plate containing 16 μM heme was inoculated with a single colony of the parent strain to yield further single colonies after 24 h of incubation. To an area circumscribed with a permanent marker and anticipated to contain single colonies, 10 μl of a 10 mM Tris (pH 8.5) solution containing 1 to 2 μg of plasmid DNA was added. After 24 h of incubation, the area containing the spotted plasmid DNA was swept with a cotton-tipped swab, and the contents of the swab were spread on a GCB plate containing 16 μM heme and appropriate antibiotic for selection. Transformants growing on the antibiotic- and heme-containing medium were passed two more times onto selective medium containing heme and stored frozen at −70°C in freezing medium (20).

Transformation and antibiotic selection of plasmid DNA into strains FA1090, MS11, and FA6982 (FA1090 hpuA::Ω) generated strains FA6973 (FA1090 hemH::CAT), FA6974 (FA1090 hemA::Ω), FA6976 (MS11 hemA::Ω), FA6977 (MS11 hemH::CAT), FA6978 (FA1090 fbpA::Ω), FA6979 (FA1090 fbpA::aphA-3), FA7006 (FA1090 tonB::Ω), FA7007 (FA7006 hemH::CAT), and FA7008 (FA6982 hemH::CAT).

Southern blot analysis and preparation of hybridization probes.

Phenol-chloroform-extracted DNA from FA6973 (FA1090 hemH::CAT), FA6974 (FA1090 hemA::Ω), and FA6978 (FA1090 fbpA::Ω) was digested with ClaI-HincII, ClaI, and HincII, respectively. FA1090 DNA was digested with ClaI-HincII, ClaI, or HincII. Following electrophoresis, Southern blotting, alkali denaturation, and prehybridization, the restriction enzyme-digested gonococcal DNA was probed with an antibiotic cassette probe (CAT or Ω) or PCR-derived DNA with the HEMA1-HEMA2, HEMH1-HEMH2, or FBP1-FBP2 primers. The antibiotic cassette probe was labelled with the DIG High Prime kit (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals), and the PCR products were labelled with the PCR DIG labelling mix (Boehringer Mannheim).

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blots.

Western blot analysis was performed on whole-cell lysates prepared from gonococci grown on GCB agar with 10 μM heme. To create iron-limiting conditions, Desferal was added to the medium. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was carried out in the discontinuous buffer system of Laemmli with a 4.5% stacking and a 12.5% resolving gel (27). Transfer and detection were performed as described previously (55). The anti-Fbp polyclonal antibody was a gift from T. Mietzner (University of Pittsburgh) and was used at a dilution of 1/5,000.

Intracellular growth assays.

The intracellular growth assays were performed under similar conditions to those described previously, with minor modifications (32). Briefly, gonococcal strains MS11, FA6977 (MS11 hemH::CAT) and FA6976 (MS11 hemA::Ψ) were grown for 16 to 18 h on GCB plates containing 10 μM heme (35). Since phase variation may have affected the ability of gonococci to attach to and invade cells, all the strains were passed fewer than six times and checked for lipooligosaccharide and opacity protein (Opa) type. The lipooligosaccharide type was checked by analysis of silver-stained polyacrylamide gels, and the Opa type was checked by Western blotting of transparent colonies probed with anti-Opa monoclonal antibody 4B12 (6). A-431 cells (derived from a human endocervical columnar epithelial line) were seeded onto 24-well plates (Falcon) and grown to 80% confluency (5 × 105 cells/well) (32). A 250-μl volume of Opa-negative, pilus-positive gonococci in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10 μg of transferrin per ml (saturation, 30%) was added to each well at 2.5 × 106 CFU/well (multiplicity of infection, 5), and the wells were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2.

After 12 h of incubation, the cell culture medium was removed and replaced for 100 min with fresh DMEM containing 10 μg of transferrin per ml and 50 μg of gentamicin per ml. Thereafter, the cell culture medium was replaced every 2 h with 1 ml of fresh DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum until the wells were ready for harvesting. Throughout the whole experiment, all the wells were washed six times with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) before addition of fresh cell culture medium, to remove any viable non-cell-associated gonococci (32).

Intracellular bacteria were recovered by lysing the A-431 cells with 0.5 ml of 0.5% saponin in GCB broth for 15 min at 37°C. Serial 10-fold dilutions of lysate (100 μl) were plated onto GCB agar containing 10 μM heme and incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 36 to 48 h. Cell-associated counts were measured before the addition of gentamicin, by lysing the cells with GCB containing 0.5% saponin as above. Non-cell-associated counts were measured by pooling the cell culture medium with 0.75 ml of fresh DMEM (used to rinse the wells once) and plating it onto GCB agar plus 10 μM heme. Each strain was assayed in triplicate at each time point, and all the counts were measured in duplicate.

RESULTS

The gonococcal hemH (encoding ferrochelatase) and hemA (encoding γ-glutamyl tRNA reductase) open reading frames were identified by TBLASTN searches of the N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 sequencing project with known HemH and HemA sequences from E. coli (40, 46, 57). The predicted amino acid sequence of FA1090 HemH had a size of 38 kDa with 41% identity and 62% similarity to HemH of E. coli. Similarly, the predicted amino acid sequence of FA1090 HemA had a size of 45 kDa with 48% identity and 65% similarity to HemA of E. coli (40, 57). Further analysis of the FA1090 sequencing database showed putative transcriptional terminator sequences located immediately downstream of both genes, with the gene downstream of hemH being in the opposite orientation. Furthermore, none of the downstream genes appear to be involved in heme biosynthesis. This is consistent with the arrangement of the corresponding hemH and hemA genes in E. coli (3). Thus, it is unlikely that interruption of hemH or hemA would lead to a polar effect on downstream genes.

To determine if exogenous heme is internalized intact and utilized for growth, we created gonococcal mutants with mutations in the two putative heme biosynthetic genes (hemH and hemA) and in a periplasmic iron transporter gene (fbpA) (Fig. 1). The general strategy was to clone the open reading frames of the genes by PCR, mutagenize them, and return the mutation to the gonococcal chromosome by allelic exchange. The insertions of the Ω and aphA-3 antibiotic cassettes in the fbp operon were designed to create polar and nonpolar mutations, respectively (34, 45). Since the hemH and hemA isogenic mutants were constructed to generate a heme auxotrophic phenotype, gonococcal transformants were recovered by antibiotic selection on heme-containing medium.

Confirmation that the hemH, hemA, and fbpA genes had been successfully cloned was obtained by PCR, restriction analysis, and Southern hybridization (Fig. 2 and data not shown). The PCR products obtained with either the hemH, hemA, or fbpA primers on template DNA from the isogenic mutants were similar in size to the PCR products from the plasmids that had transformed them, suggesting that allelic exchange had occurred (Fig. 1 and 2). Also, the difference in size between the PCR products from the parent strains and their isogenic mutants were compatible with a DNA fragment, of the length of the antibiotic cassette, being inserted into the open reading frames of hemH, hemA, and fbpA (Fig. 1 and 2). Full confirmation of allelic exchange was obtained by Southern blotting with digoxigenin-labelled DNA probes of the antibiotic cassettes and hemH, hemA, and fbpA PCR products (data not shown).

Growth phenotypes of the heme biosynthetic mutants.

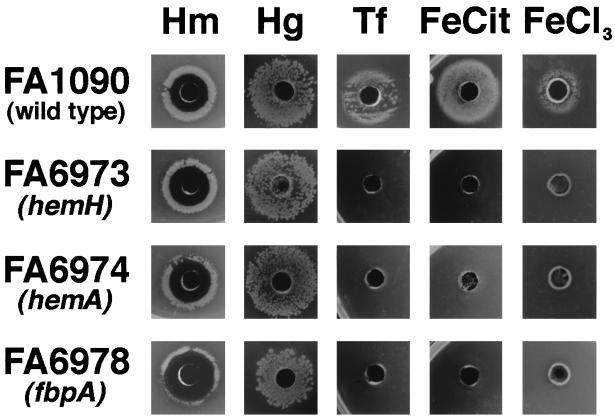

The heme biosynthetic mutants (containing the hemA and hemH mutations) grew on GCB agar containing 4 to 16 μM heme. Addition of Desferal, to create iron-limiting conditions, had no effect on growth. Interestingly, the hemH mutant turned reddish brown after prolonged incubation (36 to 48 h). Excessive accumulation of heme precursors, particularly protopophyrin IX, which could not be converted to heme in a ferrochelatase mutant may explain this phenomenon (3). Despite the color change, there was no obvious evidence of toxicity in the hemH mutant. However, when more than 16 μM heme was incorporated into the agar, neither the parent strain nor the heme mutants grew. Similarly, all strains showed a zone of inhibition around wells containing heme in a diffusion assay (Fig. 3). A possible explanation for the lack of growth around higher concentrations of heme was that sodium hydroxide (used to solubilize the heme) exerted an inhibitory effect. However, growth of the parent strains were unaffected around a control well containing 60 μl of 0.1 M NaOH on GCB agar (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Growth phenotypes of FA1090, FA6973 (FA1090 hemH::CAT), FA6974 (FA1090 hemA::Ω), and FA6978 (FA1090 fbpA::Ω) around 0.6-cm wells cut in GCB agar with 50 μM Desferral. The wells were filled with 60 μl of one of the following: heme, 1 mg/ml (Hm); hemoglobin, 10 mg/ml (Hg); transferrin, 25 mg/ml (Tf); iron citrate, 10 mM (FeCit); and iron chloride, 10 mM (FeCl3). All the plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h in 5% CO2.

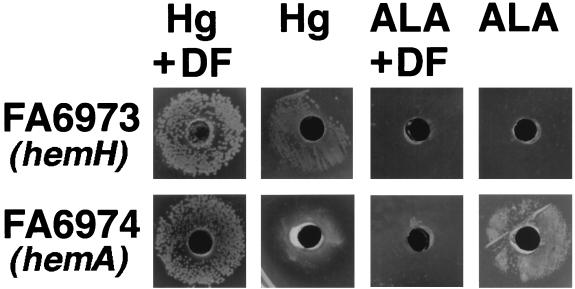

The hemA mutant grew well in the presence of ALA (≥100 μM), provided that a source of iron was available, but grew poorly around a well containing protoporphyrin IX (Fig. 4 and data not shown). The hemH mutant failed to grow around wells containing either ALA or protoporphyrin IX. Both the parent strain and hemA mutant turned pink-red following prolonged incubation on GCB agar with ALA. This color change may have resulted from loss of feedback inhibition of heme synthesis (56). Overproduction of heme and porphyrins can occur with exogenous ALA, since heme synthesis is regulated by HemA, and continues when ALA is added (58). As anticipated, growth of both the hemA and hemH mutants did not occur around wells containing a nonheme iron source, consistent with their dependence on a supply of exogenous heme for growth (Fig. 3).

FIG. 4.

Growth phenotypes of FA6973 (FA1090 hemH::CAT) and FA6974 (FA1090 hemA::Ω) around 0.6-cm wells cut in GCB agar both with and without 50 μM Desferral (DF). The wells contain 60 μl of either 10-mg/ml hemoglobin (Hg) or 10 mM ALA. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h in 5% CO2.

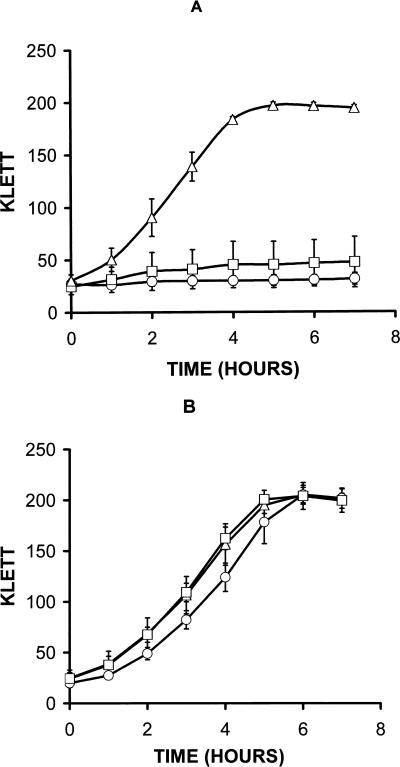

The hemH and hemA mutants were examined for growth characteristics in GCB broth, both with and without additional heme, to determine the effects of heme starvation and requirements for exogenous heme. The heme mutants grew very poorly in standard GCB broth, achieving less than two doublings (based on Klett readings) over a 7-h period (Fig. 5A). To achieve growth comparable to the parent strain, the addition of at least 1 μM heme was required (Fig. 5B). There was, however, a slight lag in the growth of the hemH mutant, compared to the hemA mutant and the parent strain. No discernible difference in growth rates was observed when between 1 and 16 μM heme was added to the broth (Fig. 5B and data not shown). The MS11-derived heme mutants (FA6977 and FA6976) showed identical growth phenotypes in the broth and well diffusion assays to those of the FA1090-derived heme mutants (FA6973 and FA6974) (Table 1 and data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Growth of MS11(Δ), FA6976 (MS11 hemA::Ω) (□), and FA6977 (MS11 hemH::CAT) (○) in GCB broth with and without additional heme. (A) Strains grown in GCB broth without heme; (B) strains grown in GCB broth with 1 to 3 μM heme. The results are based on three independent experiments, and the vertical bars represent one standard deviation. Similar results were obtained with FA6973 (FA1090 hemH::CAT) and FA6974 (FA1090 hemA::Ω), respectively (data not shown).

Growth with hemoproteins as a heme source.

The heme biosynthetic mutants were tested for the ability to grow in the presence of various hemoproteins, including hemoglobin, myoglobin, catalase, and cytochrome c. No detectable growth occurred around wells containing these heme sources, with the exception of hemoglobin (data not shown). Growth of the heme biosynthetic mutants with hemoglobin (>0.3 μM) as the sole heme and iron source was comparable to growth of the parent strain, provided that the HpuAB receptor was expressed (Fig. 3). However, after 24 h on GCB plus hemoglobin, the colony size of the heme biosynthetic mutants was reduced compared with that of the mutants on the same medium containing Desferal (Fig. 4). The essential role of the HpuAB receptor in the hemoglobin-utilizing biosynthetic mutants was demonstrated by generating hemH and hemA mutants from HpuB-expressing and -nonexpressing strains of FA1090. These strains were tested for growth on GCB agar containing either 2.4 μM hemoglobin or 8 μM heme. Outer membranes of colonies picked from hemoglobin plates were probed with polyclonal antibody to HpuB on Western blots and showed the expected 85-kDa band (data not shown) (9). Furthermore, a double isogenic mutant containing antibiotic cassette insertions in hpuA and hemH, FA7008 (FA1090 hemH::CAT hpuA::Ω), grew well on GCB agar with heme after 24 h but not on GCB agar with hemoglobin even after 48 h (9). Heme utilization from hemoglobin was also TonB dependent, since an HpuAB-expressing, TonB isogenic mutant, FA7007 (FA1090 hemH::CAT tonB::Ω), grew with heme but not with hemoglobin (reference 4 and data not shown).

Characterization of the fbp mutants.

Since heme can be internalized and used by gonococci as an iron source for growth, an attempt was made to construct two isogenic fbp mutants of FA1090 and rescue them on GCB agar containing heme or hemoglobin (1). The construction of the fbp mutants was designed to create both a nonpolar (FA1090 fbpA::aphA-3) mutation and a polar (FA1090 fbpA::Ω) mutation in the fbp operon (fbpABC) (34, 45).

Rescue of the fbp mutants on heme proved successful, and (with the exception of antibiotic selection) no discernible difference in phenotype between FA6978 (FA1090 fbpA::Ω) and FA6979 (FA1090 fbpA::aphA-3) was observed on further characterization. The fbp mutants were unaffected in their ability to grow on heme or hemoglobin but were unable to utilize transferrin, ferric citrate, or ferric chloride as the sole iron source (Fig. 3). Thus, the fbp mutants were actually dependent on heme or hemoglobin for growth. Although the fbp mutants showed a similar phenotype to the hemH mutant, requiring similar amounts of heme or hemoglobin for growth, they did not turn reddish brown after prolonged incubation on GCB agar containing heme. Like the heme biosynthetic mutants, growth with hemoglobin was dependent on expression of the HpuAB receptor, but unlike the heme biosynthetic mutants, the addition of Desferal to GCB-hemoglobin agar had no observable effect on the size of the colonies at 24 h (Fig. 3 and data not shown).

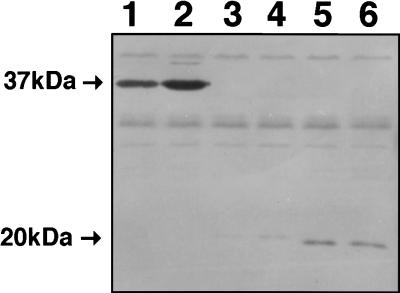

Western blots of whole-cell lysates from FA1090, probed with a polyclonal antibody to FbpA, showed an iron-regulated band of approximately 37 kDa, consistent with expression of FbpA (Fig. 6). The 37-kDa band was not present in whole-cell lysates of FA6978 (FA1090 fbpA::Ω) under both iron-replete and iron-limiting conditions. However, an additional band of about 21 and 19 kDa was present for FA6978 (FA1090 fbpA::Ω) and FA6979 (FA1090 fbpA::aphA-3), respectively, which could represent N-terminal partial protein products of FbpA (Fig. 6). The size differences can be reconciled by comparing the predicted size of the truncated open reading frames from both constructs.

FIG. 6.

Western blot of gonococcal whole-cell lysates from FA1090, FA6978 (FA1090 fbpA::Ω), and FA6979 (FA1090 fbpA::aphA-3) probed with polyclonal antibody against FbpA. Lanes: 1, FA1090 (iron replete); 2, FA1090 (iron limited); 3, FA6979 (iron replete); 4, FA6979 (iron limited); 5, FA6978 (iron replete); 6, FA6978 (iron limited).

Heme auxotrophs fail to grow inside epithelial cells.

Most heme is found within the cytoplasm and mitochondria of cells in the form of hemoproteins, providing a potential source of heme and iron for growth. Since little is known about how gonococci can utilize iron or heme from within cells, the heme auxotrophs were tested for the ability to survive and grow within an endocervical epithelial cell line. MS11 was chosen as the parent strain, because it has been characterized in attachment, invasion, and intraepithelial cell growth assays (32, 35).

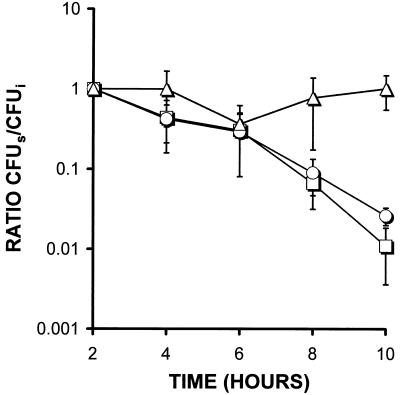

The hemH and hemA mutants invaded cells at the same rate as MS11 (data not shown). The ratio of cell-associated to non-cell-associated counts for MS11 and the hemH mutant 12 h postinoculation (immediately before addition of gentamicin) was 46 and 37%, respectively. The intracellular counts for MS11 and the hemH mutant 14 h after inoculation (2 h after addition of gentamicin) were also similar: 1.3 × 104 for MS11 and 2.5 × 104 for the hemH mutant. The differences in the ratio of cell-associated to non-cell-associated counts and in the absolute intracellular counts were not statistically significant at these time points. The intracellular survival of the hemH mutants, however, was markedly reduced 22 h postinoculation compared with that of MS11 (Student t test, P < 0.01) (Fig. 7). Similarly, 12 h postinoculation, non-cell-associated bacterial counts of the hemH mutant in cell culture medium were reduced more than 100-fold (Student t-test, P < 0.05) compared with MS11 counts (data not shown). The hemA mutant gave similar results to the hemH mutant (Fig. 7 and data not shown). Thus, the heme biosynthetic mutants attached and invaded A-431 cells normally but failed to grow in the cell culture medium and showed reduced survival within A-431 epithelial cells.

FIG. 7.

Intracellular growth and survival of MS11 (Δ), FA6976 (MS11 hemA::Ω) (□) and FA6977 (MS11 hemH::CAT) (○) inside epithelial cell line A-431. Gentamicin was added 12 h postinoculation to allow time for attachment and invasion. Time refers to the time after addition of gentamicin. The results are standardized to give a ratio by dividing the number of surviving colonies (CFUs) at various time points between 2 and 10 h after addition of the gentamicin by the number of initial colonies (CFUi) at 2 h after addition of the gentamicin. Thus, CFUs/CFUi at 2 h gives a ratio of 1 for all three strains. Results are based on three independent experiments, each with three wells per strain, and the vertical bars represent one standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

We constructed gonococcal hemA, hemH, and fbpA isogenic mutants and confirmed their genotype by PCR and Southern hybridization. Although a polar effect downstream of hemA and hemH cannot be completely excluded, analysis of DNA sequences surrounding the hemH and hemA open reading frames released from the University of Oklahoma gonococcal sequencing project suggests that neither of these genes form part of an operon for heme synthesis.

The hemH mutant was predicted to lack the enzyme ferrochelatase, necessary for inserting iron into the porphyrin ring of protoporphyrin IX to make heme, whereas the hemA mutant was predicted to lack γ-glutamyl tRNA reductase, necessary for synthesis of ALA, which is an early substrate in heme synthesis (3). The phenotypes of both mutants were consistent with these predictions. Concern that the hemH mutant would fail to grow, due to an inability to internalize heme, proved to be unfounded, since the mutant grew well when either exogenous heme or hemoglobin was present. The hemA mutant also grew in the presence of ALA, provided that an iron source was available, consistent with an inability to synthesize ALA.

Utilization of exogenous heme by gonococci is advantageous, since a large proportion of the iron requirement is likely to be directed to endogenous heme synthesis. Exogenous heme can reduce heme biosynthesis by feedback inhibition and serve as substrate for synthesis of hemoproteins (3, 56, 58). In addition to providing heme for synthesis of hemoproteins, exogenous heme fulfills the iron requirements in gonococci. How this occurs is unclear; eukaryotic cells contain heme oxygenase enzymes (HO1 and HO2) which mobilize iron from heme, but only one heme oxygenase homolog has been found in proteobacteria (HmuO in Corynebacterium diphtheriae) (48). Searches of the Oklahoma genomic sequencing and National Center for Biotechnology Information GeneBank databases with HO1, HO2, and HmuO failed to show any significant prokaryotic homology.

We demonstrated that in addition to serving as an iron source, exogenous heme could be utilized as a heme source by gonococci. However, excess heme inhibited growth, possibly due to lipid peroxidation of membranes (28). The heme biosynthetic mutants were able to utilize heme from hemoglobin in a TonB-dependent manner, provided that the hemoglobin receptor (HpuAB) was expressed. Growth at 24 h with hemoglobin as the sole heme and iron source was better than growth on hemoglobin with additional iron in the medium, suggesting that iron limitation enhances heme utilization from hemoglobin. The most likely explanation for this observation is that more hemoglobin receptor is expressed under iron-limiting conditions (9). In contrast, iron limitation had no observable effect on heme utilization from free heme, which, like iron utilization from heme, was TonB independent (4).

There is circumstantial evidence for a gonococcal heme receptor, based on growth experiments in broth, in which a monoclonal antibody that recognizes a 97-kDa heme affinity-purified total membrane protein appeared to inhibit iron utilization from heme (29). Characterization of a putative heme receptor, even with an isogenic mutant, may prove difficult. Heme is a relatively small (660-Da), poorly soluble, hydrophobic molecule, thereby presenting potential difficulties in differentiating receptor-mediated utilization from nonspecific utilization. It is quite possible that gonococci do not express a heme receptor and that heme is internalized by nonspecific mechanisms, such as entry through a porin protein channel. Nonspecific uptake of heme by gonococci would account for the apparent lack of a TonB phenotype and the lack of inhibition of heme-dependent growth by free iron in the medium (4, 50). The inability of gonococci to utilize iron from heme-hemopexin and heme-albumin is also consistent with absence of a heme receptor (15). The available evidence is insufficient to settle the question of whether gonococci express a heme receptor.

Complementation of a hemA E. coli mutant with a cosmid containing meningococcal tonB, exbB, and exbD genes and a plasmid for the meningococcal hemoglobin receptor gene (hmbR) demonstrated growth with hemoglobin as a porphyrin source (50). This suggests that heme is internalized in this system. Since the E. coli outer membrane is normally impervious to heme, it is unclear how heme may be internalized through the periplasm and inner membrane into the cytoplasm. E. coli is not known to have a heme-specific transporter system as occurs in Yersinia enterocolitica and Y. pestis (22, 31, 51).

Western blot analysis of the fbpA mutants showed that the full-length product (37 kDa) was not made, but a smaller band (about 20 kDa), which could represent a partial protein product, was seen. However, it is unlikely that this product could retain functional iron-binding activity, since the fbpA mutant was unable to utilize iron from transferrin, ferric citrate, and ferric chloride. Lactoferrin was not tested as an iron source for the fbpA mutant because the parent strain FA1090 does not have a complete lactoferrin receptor.

One possible route for transporting iron from heme is via FbpA. This may occur if iron can be stripped from the heme ring before entering the cytoplasm. Liberated iron could bind to FbpA in the periplasm and be transported into the cytoplasm by the inner membrane FbpBC complex. Based on one uptake study of 14C- and 59F-radiolabelled heme, iron appeared to be stripped from heme and transported to the inner membrane by FbpA (14). However, iron reentering the periplasm from the cytoplasm or nonspecific binding may have contributed to this effect. We found that FbpA was not necessary for heme utilization in gonococci, because the fbpA isogenic mutants grew normally with heme or hemoglobin as the sole source of iron. We cannot exclude the possibility that FbpA plays a role in heme utilization, but it was clearly not necessary for growth of the fbpA mutants, as it was for iron uptake from transferrin and ferric citrate.

The gonococcal fbpA mutant phenotype was similar to that of an H. influenzae fbpA mutant, which was unable to utilize iron from transferrin but could still utilize iron from heme and hemoglobin (26). Following submission of this manuscript, an N. meningitidis fbpABC mutant which also showed a similar phenotype to the gonococcal fbpA mutant was described (25). This mutant grew with heme and hemoglobin as an iron source but was unable to utilize iron from transferrin, lactoferrin, and iron chelates.

The heme biosynthetic auxotrophs were able to attach to and invade A-431 cells but, unlike the parent strain, failed to survive inside the cells. No clear difference in intracellular survival was observed between the heme biosynthetic mutants. An inability to assimilate heme or heme precursors from within epithelial cells seems the most likely reason for this observation. One possible explanation is that gonococci are unable to utilize heme from hemoproteins, other than hemoglobin, which form the largest source of intracellular heme (15, 38). Also, many of the heme precursors and hemoproteins are synthesized and located within mitochondria, making it difficult for gonococci to obtain these substrates for growth. It remains unclear how gonococci acquire iron during growth within epithelial cells.

In summary, gonococci can utilize heme and hemoglobin as a heme source. Within epithelial cells, heme sources do not appear able to support the survival or growth of heme auxotrophic mutants. Internalization of heme probably occurs independently of FbpA. Further studies to investigate and characterize possible heme receptors and heme transport systems are under way.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant 044338/Z/95/Z to P. C. Turner) and the National Institutes of Health (grants AI 26837 and AI 31496 to P. F. Sparling and AI 32493 to M. So).

We thank D.A Ala’Aldeen, M. So, C. J. Chen, and all the members of the Sparling laboratory for helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank W. Westhoff for help in preparing the A-431 cell lines, A. Rountree for expert technical assistance, T. Mietzner for the polyclonal antibody against FbpA, M. S. Blake for the monoclonal antibody 4B12 against Opa, C. J. Chen for the polyclonal antibody to HpuB, and C. Cornelissen for the fbpA primers.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adhikari P, Berish S A, Nowalk A J, Veraldi K L, Morse S A, Mietzner T A. The fbpABC locus of Neisseria gonorrhoeae functions in the periplasm-to-cytosol transport of iron. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2145–2149. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2145-2149.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagg A, Neilands J B. Ferric uptake regulation protein acts as a repressor, employing iron (II) as a cofactor to bind the operator of an iron transport operon in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1987;26:5471–5477. doi: 10.1021/bi00391a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beale S I. Biosynthesis of hemes. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 731–748. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biswas G D, Anderson J E, Sparling P F. Cloning and functional characterization of Neisseria gonorrhoeae tonB, exbB and exbD genes. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:169–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3421692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biswas G D, Sparling P F. Characterization of lbpA, the structural gene for a lactoferrin receptor in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2958–2967. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.2958-2967.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blake M S, Porat N, Qi H, Apicella M A. Presented at the Neisseria 94 Conference, 26 to 30 September 1994, Winchester, England. 1994. Several of the gonococcal Opa proteins share a common epitope and functional features with host cell proteins such as LOS binding and 4B12 reactivity. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun V. Energy-coupled transport and signal transduction through the Gram-negative outer membrane via TonB-ExbB-ExbD-dependent receptor proteins. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1995;16:295–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1995.tb00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C, Berish S A, Morse S A, Mietzner T A. The ferric iron-binding protein of pathogenic Neisseria spp. functions as a periplasmic transport protein in iron acquisition from human transferrin. Mol Microbiol. 1993;1993:311–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen C J, Elkins C E, Sparling P F. Phase variation of hemoglobin utilization in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1998;66:987–993. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.987-993.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cope L D, Thomas S E, Latimer J L, Slaughter C A, Muller-Eberhard U, Hansen E J. The 100kDa haem:haemopexin-binding protein of Haemophilus influenzae: structure and localization. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:863–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornelissen C N, Sparling P F. Iron piracy: iron acquisition from transferrin by bacterial pathogens. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:843–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daskaleros P A, Stoebner J A, Payne S M. Iron uptake in Plesiomonas shigelloides: cloning of the genes for heme-iron uptake system. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2706–2711. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2706-2711.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dempsey J F, Litaker W, Madhure A, Snodgrass T L, Cannon J G. Physical map of the chromosome of Neisseria gonorrhoeae FA1090 with locations of genetic markers, including opa and pil genes. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5476–5486. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5476-5486.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai P J, Nzeribe R, Genco C A. Binding and accumulation of hemin in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4634–4641. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4634-4641.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyer D W, West E P, Sparling P F. Effects of serum carrier proteins on the growth of pathogenic neisseriae with heme-bound iron. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2171–2175. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2171-2175.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elkins C. Identification and purification of a conserved heme-regulated hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein from Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1241–1245. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1241-1245.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elkins C, Thomas C E, Seifert H S, Sparling P F. Species-specific uptake of DNA by gonococci is mediated by a 10-base-pair sequence. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3911–3913. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.12.3911-3913.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghigo J, Letoffe S, Wandersman C. A new type of hemophore-dependent heme acquisition system of Serratia marcescens reconstituted in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3572–3579. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3572-3579.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guerinot M L. Microbial iron transport. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:743–772. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunn J S, Stein D C. Use of a non-selective transformation technique to construct a multiply restriction/modification-deficient mutant of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Gen Genet. 1983;251:509–517. doi: 10.1007/BF02173639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson D P, Payne S M. Characterization of the Vibrio cholerae outer membrane heme transport protein HutA: sequence of the gene, regulation of expression, and homology to the family of TonB-dependent proteins. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3269–3277. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3269-3277.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hornung J M, Jones H A, Perry R D. The hmu locus of Yersinia pestis is essential for utilization of free haemin and haem-protein complexes as iron sources. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:725–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jossens M O, Eskenazi B, Schachter J, Sweet R L. Risk factors for pelvic inflammatory disease. A case control study. Sex Transm Dis. 1996;23:239–247. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199605000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kellogg D S, Jr, Peacock W L, Jr, Deacon W E, Brown L, Pirkle C I. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. I. Virulence genetically linked to clonal variation. J Bacteriol. 1963;85:1274–1279. doi: 10.1128/jb.85.6.1274-1279.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khun H H, Kirby S D, Lee B C. A Neisseria meningitidis fbpABC mutant is incapable of using nonheme iron for growth. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2330–2336. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2330-2336.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirby S D, Gray-Owen S D, Schryvers A B. Characterization of a ferric-binding protein mutant in Haemophilus influenzae. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:979–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee B C. Quelling the red menace: haem capture by bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:383–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee B C, Levesque S. A monoclonal antibody directed against the 97-kilodalton gonococcal hemin-binding protein inhibits hemin utilization by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2970–2974. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2970-2974.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis L A, Dyer D D. Identification of an iron-regulated outer membrane protein of Neisseria meningitidis involved in the utilization of hemoglobin complexed to haptoglobin. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1299–1306. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1299-1306.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lillard J W, Fetherston J D, Pedersen L, Pendrak M L, Perry R D. Sequence and genetic analysis of the hemin storage (hms) system of Yersinia pestis. Gene. 1997;193:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin L, Ayala P, Larson J, Mulks M, Fukuda M, Carlsson S R, Enns C, So M. The Neisseria type 2 IgA1 protease cleaves LAMP1 and promotes survival in bacteria within epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1083–1094. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4191776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Litwin C M, Calderwood S B. Role of iron in regulation of virulence genes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:137–149. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menard R, Sansonetti P J, Parsot C. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5899–5906. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5899-5906.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer T F, Mlawer N, So M. Pilus expression in Neisseria gonorrhoeae involves chromosomal rearrangement. Cell. 1982;30:45–52. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mickelsen P A, Sparling P F. Ability of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Neisseria meningitidis, and commensal Neisseria species to obtain iron from transferrin and iron compounds. Infect Immun. 1981;33:555–564. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.2.555-564.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mietzner T A, Barnes R C, JeanLouis Y A, Shafer W M, Morse S A. Distribution of an antigenically related, iron-regulated protein among the Neisseria spp. Infect Immun. 1986;51:60–68. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.1.60-68.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mietzner T A, Morse S A. The role of iron-binding proteins in the survival of pathogenic bacteria. Annu Rev Nutr. 1994;14:471–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.14.070194.002351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mills M, Payne S M. Genetics and regulation of heme iron transport in Shigella dysenteriae and detection of an analogous system in Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3004–3009. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3004-3009.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyamato K, Kanaya S, Morikawa K, Inokuchi H. Overproduction, purification, and characterization of ferrochelatase from Escherichia coli. J Biochem. 1994;115:545–551. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moss G B, Overbaugh J, Welch M, Reilly M, Bwayo J, Plummer F A, Ndinya-Achola J O, Malisa M A, Kreiss J K. Human immunodeficiency virus DNA in urethral secretions in men: association with gonococcal urethritis and CD4 cell depletion. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1469–1474. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.6.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Otto B R, Verweij-van Vught A M, MacLaren D M. Transferrins and heme-compounds as iron sources for pathogenic bacteria. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1992;18:217–233. doi: 10.3109/10408419209114559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Payne S M. Iron and virulence in the family Enterobacteriaceae. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1988;16:81–111. doi: 10.3109/10408418809104468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poole K, Neshat S, Krebes K, Heinrichs D E. Cloning and nucleotide sequence analysis of the ferripyoverdine receptor gene fpvA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4597–4604. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4597-4604.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prentki P, Kirsch H M. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roe B A, Lin S P, Song L, Yuan X, Clifton S, Ducey T, Lewis L, Dyer D W. The Gonococcal Genome Sequencing Project. Norman and Oklahoma City, Okla: University of Oklahoma; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rutz J M, Abdullah T, Singh S P, Kalve V I, Klebba P E. Evolution of the ferric enterobactin receptor in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5964–5974. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.5964-5974.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmitt M P. Utilization of a gene whose product is homologous to eukaryotic heme oxygenases and is required for acquisition of iron from heme and hemoglobin. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:838–845. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.838-845.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stojiljkovic I, Hwa V, de Saint Martin L, O’Gaora P, Nassif X, Heffron F, So M. The Neisseria meningitidis haemoglobin receptor: its role in iron utilization and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:531–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stojiljkovic I, Srinvisan N. Neisseria meningitidis tonB, exbB, exbD genes: Ton-dependent utilization of protein-bound iron in neisseriae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:805–812. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.805-812.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stojilkovic I, Hantke K. Transport of haemin across the cytoplasmic membrane through a haemin-specific periplasmic binding protein-dependent transport system in Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:719–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas C E, Carbonetti N H, Sparling P F. Pseudo-transposition of a Tn5 derivative in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:371–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas C E, Sparling P F. Isolation and analysis of a fur mutant of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4224–4232. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4224-4232.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thony-Meyer L. Biogenesis of respiratory cytochromes in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:337–376. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.337-376.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Towbin J, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedures and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verderber E, Lucast L J, Van Dehy J A, Cozart P, Etter J B, Best E A. Role of the hemA gene product and delta-aminolevulinic acid in regulation of Escherichia coli heme synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4583–4590. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4583-4590.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verkamp E, Chelm B K. Isolation, nucleotide sequence, and preliminary characterization of the Escherichia coli K-12 hemA gene. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4728–4735. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.4728-4735.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang L Y, Brown L, Elliott M, Elliott T. Regulation of heme biosynthesis in Salmonella typhimurium: activity of glutamyl-tRNA reductase (HemA) is greatly elevated during heme limitation by a mechanism which increases abundance of the protein. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2907–2914. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2907-2914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weinberg E D. Iron withholding: a defense against infection and neoplasia. Physiol Rev. 1984;64:65–102. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1984.64.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang H, Inokuchi H, Adler J. Phototaxis away from blue light by an Escherichia coli mutant accumulating protoporphyrin IX. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7332–7336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]