Dear editor,

I read with interest the publication by Domai et al. in The Lancet Regional Health on measles outbreak in the Philippines in 2016–2019. The authors emphasized that routine immunization needs to be strengthened to prevent further outbreaks, especially their analysis showed that 41% of deaths occurred in children aged less than nine months; with 23% occurring between 6 and 9 months. They also added that further research should be undertaken to identify the health system and cultural factors associated with vaccination hesitancy in the Philippines.1 In relation to this, I would like to flesh their claims, especially with another impending measles outbreak in the country for this current year, 2023–2024. I also aim to reiterate the basic information of the disease and propose some interventions that can help the country in the prevention of measles outbreak in the future.

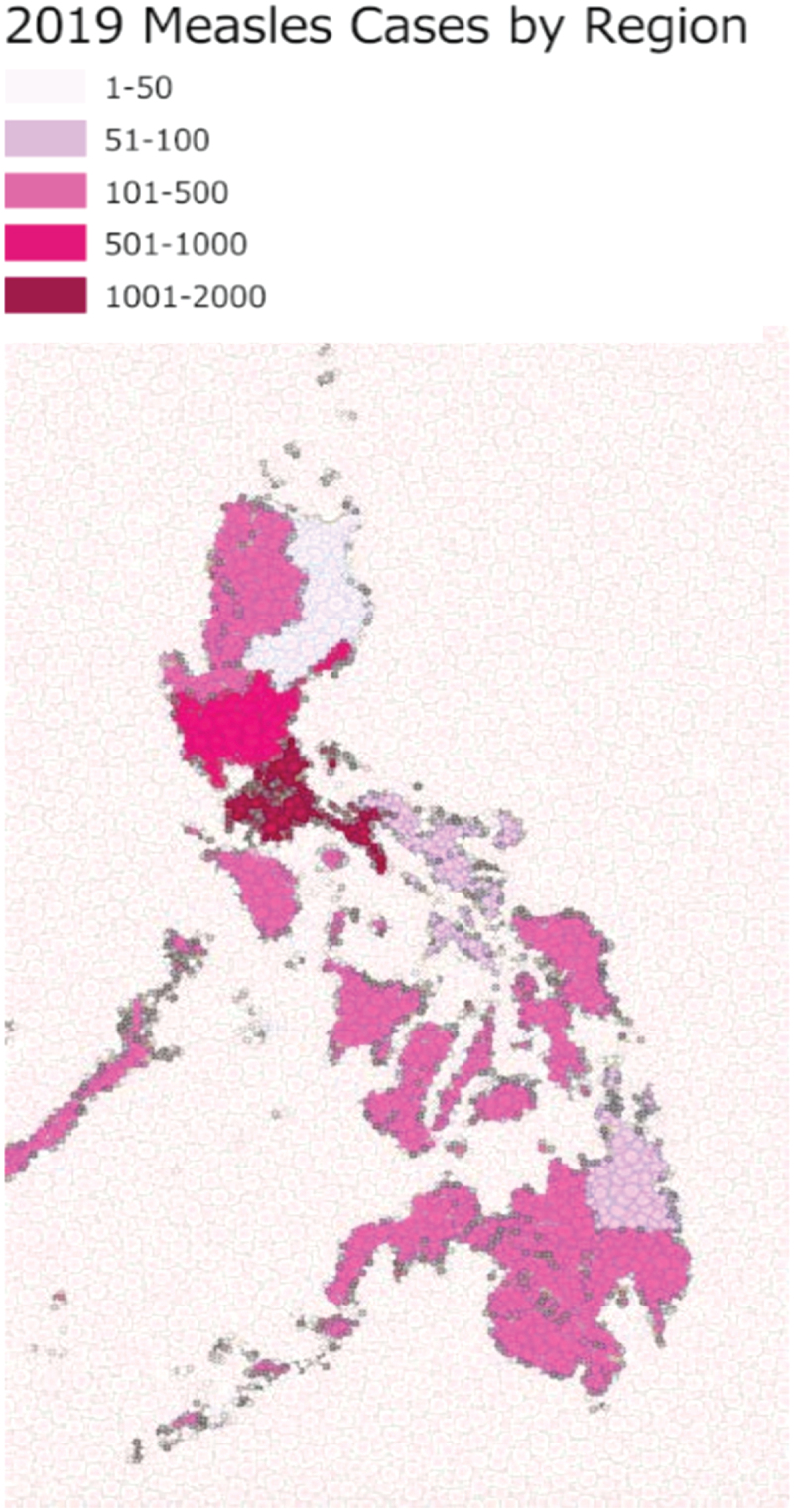

It is important to note that the largest measles outbreak in the World Health Organization Western Pacific region occurred in the Philippines, with reported cases increasing from 2,428 in 2017 to 20,827 in 2018 and 48,525 toward the end of 2019.2 There were 338 deaths reported in the early months of 2019 nationwide. The Philippine map below as shown in Figure 1 displays the regions where a measles outbreak has been officially declared by the Department of Health (DOH) in 2019:

Figure 1.

2019 Philippines measles outbreak.

Source: International Federation of Red Cross (IFRC) using data from DOH - Measles

Surveillance report, Feb 2020

The 2019 measles outbreak is attributed to lower vaccination rates, allegedly caused by the Dengvaxia vaccine controversy. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund’s (UNICEF) latest global report, some 67 million children partially or fully missed routine vaccines globally between 2019 and 2021 because of lockdowns and healthcare disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Philippines is the second highest in East Asia and the Pacific Region and the fifth highest globally in the number of children who missed out on routine vaccines, estimated to be 1,048,000.3 On another note, the Dengvaxia controversy in 2017 is an allegation thrown at the dengue vaccine, Dengvaxia, which was developed by the pharmaceutical giant Sanofi. The vaccine has been used in a widespread school vaccination program and was linked to the deaths of some children in the Philippines. This issue caused a lot of vaccine hesitancy among many parents. It paved the way for doubts about the efficacy and usefulness of all other vaccines, including measles.

In 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic started to cause serious effects globally, the suspension of immunization services and declines in immunization rates and surveillance across the globe left millions of children vulnerable to preventable diseases like measles. No country is exempt from measles, and areas with low immunization encourage the virus to circulate, increasing the likelihood of outbreaks and putting all unvaccinated children at risk,4 especially the Philippines. In a recent report by the DOH, measles cases in the Philippines have surged by nearly 300% from January 1 to October 14, 2023. This figure posted a 186% increase as compared to 2021.5 This continuous increase alarmed the government, which launched an extended or “catch-up” vaccination campaign for children under two years of age, particularly vulnerable to the disease. The campaign aimed to significantly increase the country’s vaccination intake to almost nine million children.

Measles is a highly contagious, airborne disease caused by the measles virus, an RNA paramyxovirus of the genus Morbillivirus6 that can lead to severe complications and death. It spreads quickly when an infected person breathes, coughs, or sneezes. It can affect anyone but is most common in children. It infects the respiratory tract and then spreads throughout the body. The symptoms include a high fever, cough, runny nose, and a rash all over the body. Vaccination is the best way to prevent or spread it to others. The vaccine is safe and helps your body fight off the virus.3 Experts believed that these measles vaccines have a “high efficacy” rate, which could provide up to 90 to 95% protection for children.

Health experts emphasize that there is no specific treatment for measles. Aside from vaccination, they usually give recommendations to relieve symptoms until the immune system defeats the virus. This is why it is essential to strengthen the immune system by maintaining proper hygiene, keeping our hands clean, covering our nose and mouth when coughing or sneezing, and, most of all, drinking enough water and eating healthy food. In addition to community-wide vaccination and these health protocols, other preventive measures include isolation of suspected or confirmed cases and a massive information campaign about the disease. Both public and private healthcare professionals, like doctors and nurses, down to the barangay health workers, must exert effort in disseminating essential information about the disease, like signs and symptoms, prevention, treatment, etc., for public awareness and preparedness. Another important way is establishing a community-based surveillance initiative being performed by trained volunteers to monitor the total number of cases and the detailed condition of those infected.

Measles is another health problem that can incapacitate the public healthcare system and, thus, seriously affect any nation’s public health. The unfortunate situation can always be prevented if a high rate of vaccination is achieved and there is mutual cooperation among all the residents and following the well-planned programs of the government. We are all in this battle, and let us defend everyone else, especially our children.

Acknowledgments

I thank De La Salle University for the continuously supporting my research endeavor.

References

- 1.Domai FM, Agrupis KA, Han SM, Sayo AR, Ramirez JS, Nepomuceno R, Suzuki S, Villanueva AMG, Salva EP, Villarama JB, et al. Measles outbreak in the Philippines: epidemiological and clinical characteristics of hospitalized children, 2016–2019. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2021;19:100334. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system. 2020 global summary. 2020. [accessed 2024 Jan 14]. https://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/countries?countrycriteria%5Bcountry%5D%5B%5D=PHL.

- 3.Austria KS. DOH extends ‘Chikiting Ligtas’ supplemental immunization program. Philippine Information Agency; 2023. [accessed 2024 Jan 9]. https://pia.gov.ph/news/2023/06/02/doh-extends-chikiting-ligtas-supplemental-immunization-program.

- 4.World Health Organization . Measles. 2023. [accessed 2024 Jan 10]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles?gclid=CjwKCAiA-vOsBhAAEiwAIWR0TXVQlfYSU1C2xoeEbQBSlKIWInXFVO-MzKR2EGY-2PbQpxs2-a1hWhoCf30QAvD_BwE.

- 5.Navalta SM. Measles cases in PH surge by 299% this year – DOH. Philippine Information Agency; [accessed 2024 Jan 12]. https://pia.gov.ph/news/2023/11/10/measles-cases-in-ph-surge-by-299-this-year-doh#:~:text=QUEZON%20CITY%20(PIA)%20%2D%2D%20According,measles%20cases%20from%20last%20year.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 2021. [accessed 2024 Jan 10]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/index.html.