Abstract

Four frozen dumplings were prepared using air-frying, microwaving, pan-frying, and steaming for consumer acceptability and texture perception measure. Cluster analysis was performed and two groups resulted. Neutral consumers who generally rated ‘like slightly’ and ‘neither like nor dislike’ were influenced by the combinations of dumpling and cooking methods. Dumpling likers who rated higher than ‘like moderately’ were influenced by cooking methods. When divided into clusters, each effect was significant. For dumplings, consumers preferred three products over one. Regarding cooking methods, neutral consumers preferred pan-frying and air-frying. However, dumpling likers preferred pan-frying. Chewy, soft, crisp, and sticky characteristics positively influenced on acceptability. In addition, dumpling shells and fillings were analyzed to measure crispness and firmness, respectively, using a texture analyzer. Cooking methods influenced skin crispness but dumplings influenced filling firmness. Although correlation was very low between consumer texture perception and analytical measure, using both would be beneficial in further understanding.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10068-023-01389-9.

Keywords: Acceptability, Texture perception, CATA-penalty, Pan-frying, Air-frying, Microwaving, Steaming

Introduction

Dumplings have been an important food source for Koreans since the Goryeo Dynasty, and have been recorded as being an exemplary food of the Joseon Dynasty (Kim et al., 1999; Jeong, 2008). The Korean Food Standards Codex indicates that dumplings are “made by molding a mixture of meat and vegetables into dumpling skins, etc.” (MFDS, 2021). Various dumpling stuffings are put in the dumpling skin, and different types of dumplings are produced and sold (Bok, 2008).

In the late 1980s, with the participation of large corporations such as Haitai Confectionery & Goods Co., Ltd; Jeil Freeze Co., Ltd; and Lotte, the demand for frozen dumplings expanded with the development of various products to meet consumer needs through diversification, differentiation, and a premium for frozen dumpling products (Bae, 2008; Lee, 1991). The names of dumplings vary depending on the food put in them, but they are usually called boiled dumplings, steamed dumplings, grilled dumplings, fried dumplings, etc., depending on the cooking method (Kim et al., 2013).

While dumplings are considered a staple food, they are also loved as a snack food by people of all ages, regardless of the season (Lee, 1991) and many consumers buy frozen dumplings because of the simplicity of cooking (Kim et al., 2009). Convenience food is preprocessed and processed using a simple cooking process (Lim et al., 2005). Frozen processed food in Korea began to be sold in the 1980s, starting with frozen dumplings, and many frozen cooked foods were launched. In recent years, convenience foods have become a new trend in dietary habits (Nam et al., 2021). For the first time in the domestic food industry, single-item sales exceeded 1 trillion KRW (Roh, 2021) accounting for 33.6% of frozen foods.

In the past, there were not many different cooking methods other than steaming or frying for dumplings, but with the diversification of cooking equipment, cooking methods for dumplings have also diversified. Additionally, a number of products that use the convenience of microwave cooking are available in the market (Seo, 2016). Although there are various methods, such as steaming, baking, boiling, and frying in recipes, there have been few studies on verifying quality indicators according to the cooking methods of frozen dumplings in the market. The main research focus has been to identify the quality characteristics of dumplings with soybean flour (Baeket al., 2021), rice flour (Mun et al., 2020), or green tea powder (June, 2016) substitution in dumpling shells, or aged kimchi in the filling (Lee et al., 2012). Most studies have added special ingredients and cooked dumplings using various methods such as steaming, baking, boiling, and deep-frying (Bishop, 1995). Few studies have been conducted on verifying quality indicators according to the cooking methods of frozen dumplings in the market (Kim et al., 2009) or temperature changes during cooking (Kim and Kim, 2013). More than a decade ago, consumer preference for dumpling cooking methods was reported to be pan-fried dumplings > steamed dumplings > boiled dumplings > dumpling soup, and this preference for cooking methods was similar for all age groups (Bae, 2008).

Studies on consumer preferences for dumplings have yet to be conducted. However, according to a sensory survey of pond-snail dumpling products, taste was the most important attribute determining the purchase of dumpling products, followed by hygienic quality, nutritional value, and price. It was found that the brand was not a very important purchasing attribute of dumplings (Chang et al., 2006).

The purposes of this study were to determine consumers’ acceptability of commercially available frozen dumplings when cooked using various cooking methods and to analyze texture properties analytically.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

Among the frozen dumplings sold at large marts and convenience stores, four types of dumplings with a high market share that can be purchased anywhere were selected. These were: CJ Bibigo Wanggyoja (sold at supermarkets) labeled in the manuscript as WBC, CJ Bibigo Jjin dumplings (sold at convenience stores) labeled as JBC, Haitai Gohyang dumplings (available at both supermarkets and convenience stores) labeled as GH, and Haitai Gohyang Shaolong dumplings (sold at convenience stores) labeled as SGH. The dumplings were stored in a freezer maintained at − 18 °C until evaluation. Cooking methods suggested by the manufacturer were tested with some modifications (Supplementary Table 1). For cooking, steaming, microwave, and air fry functions, a lightwave oven (ML32AW1, LG Electronics, Seoul, Korea), which has a power consumption of 2800 W, was used. An electric frying pan (EMP-503, Loving Home, Seoul, Korea) (power consumption 1600 W) was used for pan-frying.

Test design

The evaluation was conducted in two sessions with similar dumpling textures according to the cooking method. In the first session, the dumpling samples were evaluated using steaming and a microwave oven. In the second session, a week later, the samples were cooked using the frying pan and air fryer functions and evaluated. Eight different dumplings were provided monadically. One dumpling was placed on each plate, and the sample was cooled down to the normal consumption temperature of 60 °C on a small white 14 cm paper plate (Cleanlab, Seoul, Korea) before serving. The samples were marked using random three-digit numbers (Kim et al., 2008).

Instrumental measurements

To check the crispiness of the surface of the dumplings and the firmness of the insides, different probes were used and measured using a texture analyzer (TA-XTplusC, Godalming, United Kingdom). Crispiness was measured by penetrating the surface with a blade set (Jo, 2014a). The count peak and the linear distance were also measured using a blade set. The area, which is the total amount of energy used for cutting, and the mean, which is the average strength, were measured. Pre-test speed was set at 2mm/sec, test speed at 4 mm/sec, and post-test speed at 10mm/sec. Target mode was 95% strain with trigger force 5g as applied force. To measure the firmness of the dumplings, 34g of the dumpling filling was placed in a 50 ml beaker. The peak force, which indicates the degree of hardening according to the amount of oil, was measured using a Mini Ottawa cell, which is a method measuring firmness while compressing and extruding samples of non-uniform foods and may indicate cooking quality (Jo, 2014b; Wang et al, 2012). Additionally, the total energy used for extrusion (area) and the mean and average of the forces used during extrusion and gradient were also measured. Test condition with Mini Ottawa cell was pre-test speed 2 mm/sec, test speed 2 mm/sec, and post-test speed 10 mm/sec. Target mode was distance of 20 mm and trigger force was 5g. Crispness or firmness values were determined by averaging three replication measurements per sample. Depending on the sample, up to nine measurements were performed per replication.

Participants

The panel consisted of 86 consumers in Pusan selected using an online survey. Recruiting criteria were people aged 19 to 65 without any disease or food allergies, who were not currently on restrictive diets (thus non-vegetarian, non-pregnant), and those who had consumed dumplings at least once within the previous month. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB/2022_55_HR). Accordingly, all consumers voluntarily signed a consent form before participating in the evaluation, and monetary compensation was provided to all participants.

Questionnaire

When all the subjects in one group were seated, quick response codes were provided following the test design to access the acceptability survey questionnaire. Consumers used their own mobile devices, and paper ballots were available to those who did not wish to answer the online questionnaires. Consumers inputted their identification number and sample number each time and evaluated dumpling samples for overall acceptability, liking for appearance, and liking for texture using a nine-point hedonic scale (1 = “dislike very much” and 9 = “like very much”) (Peryam et al., 1952, 1957). The intensity of the color and the texture of the dumpling skins were measured using a nine-point intensity scale anchored as 1 being “none” and 9 being “very strong”.

A list of 51 words was provided to evaluate the texture of the dumplings. Participants checked suitable texture terms using check-all-that-apply (CATA). Participants were asked to select all attributes they considered appropriate (Adams et al., 2007; Jaeger et al., 2015; Meyners et al., 2013). At the end of the questionnaire, subjective opinions on improving the cooking method were gathered.

Data analysis

A two-way analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA) was conducted to investigate the effects of cooking methods, dumpling variety (product), and their interaction on acceptability, intensity perception, and instrumental data. When significance was found, Fisher’s least significant difference test was conducted as a post-hoc test at a significance level of 0.05. Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted on the instrumental data analysis using SAS® software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

To determine whether consumer segmentation occurred, cluster analysis using Ward’s method was conducted based on acceptability scores using PROC CLUSTER on SAS® software. Additionally, agglomerative hierarchical clustering (AHC) with center option to avoid scaling effects was run separately using XLStat® software package (version 2020.2.1., Addinsoft 167 SARL, New York, NY, USA). Demographic information is presented in a frequency table (Table 1).

Table 1.

Consumer’ demographic information

| Variables | Total (n = 86) |

Cluster 1 (n = 46) |

Cluster 2 (n = 40) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 69 | 80.2 | 39 | 84.8 | 30 | 75.0 |

| Male | 17 | 19.8 | 7 | 15.2 | 10 | 25.0 |

| Age | ||||||

| 19–25 | 46 | 53.5 | 20 | 43.5 | 26 | 65.0 |

| 26–35 | 22 | 25.6 | 14 | 30.4 | 8 | 20.0 |

| 36–45 | 15 | 17.4 | 9 | 19.6 | 6 | 15.0 |

| 46–55 | 2 | 2.3 | 2 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 56–65 | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Number of consumption of dumpling per month | ||||||

| Twice | 15 | 17.4 | 31 | 67.4 | 4 | 10.0 |

| 3–4 times | 46 | 53.5 | 12 | 26.1 | 20 | 50.0 |

| 5–8 times | 25 | 29.1 | 3 | 6.5 | 14 | 35.0 |

| Over than 8 times | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 5.0 |

| Dumplings cooking method you use (CATA) | ||||||

| MWO | 70 | 81.4 | 33 | 71.7 | 38 | 95.0 |

| Gas ovens | 73 | 84.9 | 38 | 82.6 | 35 | 87.5 |

| Air fryer | 50 | 58.1 | 31 | 67.4 | 19 | 47.5 |

| Steamer | 26 | 30.2 | 16 | 34.8 | 10 | 25.0 |

| Lightwave oven | 7 | 8.1 | 4 | 8.7 | 3 | 7.5 |

| Qooker | 2 | 2.3 | 2 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Toaster | 2 | 2.3 | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 2.5 |

| How to cook dumplings that are mainly eaten (CATA) | ||||||

| MWO | 26 | 30.2 | 9 | 19.6 | 17 | 42.5 |

| Steam | 28 | 32.6 | 16 | 34.8 | 12 | 30.0 |

| Broiling | 32 | 37.2 | 15 | 32.6 | 17 | 42.5 |

| Frying pan | 56 | 65.1 | 27 | 58.7 | 29 | 72.5 |

| Air fryer | 31 | 36.0 | 20 | 43.5 | 11 | 27.5 |

| Fryer | 6 | 7.0 | 4 | 8.7 | 2 | 5.0 |

| Things to consider when buying dumpling (CATA) | ||||||

| Price | 46 | 53.5 | 22 | 47.8 | 24 | 60.0 |

| Dumpling package size | 9 | 10.5 | 2 | 4.3 | 7 | 17.5 |

| Shape of dumplings | 36 | 41.9 | 19 | 41.3 | 17 | 42.5 |

| Ingredients of dumplings | 58 | 67.4 | 30 | 65.2 | 28 | 70.0 |

| Brand | 60 | 70.0 | 34 | 73.9 | 26 | 65.0 |

| Sale (bundle sale, 2 + 1 Discount) | 53 | 61.6 | 25 | 54.3 | 28 | 70.0 |

| Quantity (Large volume) | 16 | 18.6 | 9 | 19.6 | 7 | 17.5 |

| Serving size (1 Serving) | 13 | 15.1 | 5 | 10.9 | 8 | 20.0 |

| Sauce | 2 | 2.3 | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Packaging (can be sealed) | 10 | 11.6 | 4 | 8.7 | 6 | 15.0 |

| Cooking example (photo) | 8 | 9.3 | 4 | 8.7 | 4 | 10.0 |

| How to cook | 28 | 32.6 | 13 | 28.3 | 15 | 37.5 |

| Cooking time | 5 | 5.8 | 3 | 6.5 | 2 | 5.0 |

| Where to buy dumplings (CATA) | ||||||

| Convenience store | 33 | 38.4 | 11 | 23.9 | 22 | 55.0 |

| Small supermarket | 39 | 45.3 | 23 | 50.0 | 16 | 40.0 |

| Large retailer | 81 | 94.2 | 44 | 95.7 | 37 | 92.5 |

| Food mart | 25 | 29.1 | 11 | 23.9 | 14 | 35.0 |

| Warehouse type whole-sale discount store | 20 | 23.3 | 11 | 23.9 | 9 | 22.5 |

| Online | 42 | 48.8 | 21 | 45.7 | 21 | 52.5 |

| Early morning delivery | 17 | 19.8 | 9 | 19.6 | 8 | 20.0 |

Correspondence analysis (CA) was conducted using texture CATA frequency data to show the texture characteristics of the dumpling samples. RV coefficient was calculated between the CA biplot and the PCA. Additionally, CATA-penalty (Ares and Jaeger, 2023) was run to learn what texture attributes contribute liking or disliking of the dumplings. The XLStat® software package was used for the CATA data analysis.

Results and discussion

Consumers’ demographic information

A total of 86 consumers participated, of whom 69 were women and 46 (53.5%) were aged 19 to 25 years, and the frequency of eating dumplings 3 to 4 times a month was 53.5%. The consumer consumption behaviors are shown in Table 1. Dumpling cooking equipment utilized was microwave ovens (81.4%) and gas ovens (84.9%), followed by air fryers (58.1%) and steamers (30.2%). Pan-frying was the main cooking method used, followed by boiling, air-frying, steaming, and microwaving at similar percentages (37.2–30.2%). When purchasing dumplings, consumers considered the brand (70.0%) the most, followed by the ingredients (67.4%) and sale of dumplings (61.6%). Approximately 94% purchased dumplings from large retailers.

Dumpling acceptability

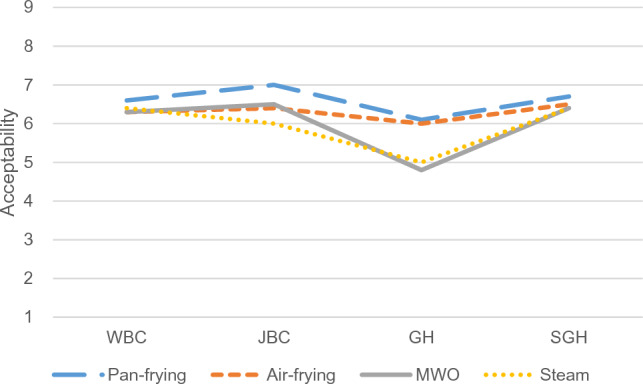

The interaction between the dumpling sample and cooking method was significant (p = 0.0069) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). GH dumplings were liked more when pan-fried or air-fried than when cooked using microwaving or steaming. JBC dumplings were liked more when cooked using pan-frying than steaming. SGH dumplings had similar properties such as oily, creamy, liquid and flexible, regardless of the cooking method. For the other dumpling samples, cooking methods did not significantly influence acceptability. The overall acceptability was similar at 6.4 points scored, except for GH dumplings, and pan-frying had the highest preference at a 6.6-point score (Fig. 1). Although acceptability was not evaluated, research on internal temperature change during cooking (Kim and Kim, 2013) compared boiling, steaming, pan-frying, and deep fat frying, and reported that there was a significant interaction effect between dumpling size and cooking time on the internal temperature change of dumplings. Because cooking temperature depends on cooking methods, it influences the internal temperature of dumplings differently, resulting in differently cooked dumplings. For steamed dumplings with juice development, sensory testing with female consumers in their 30 and 40s resulted in a taste and aroma liking of 5.4 for the control sample purchased from a popular Chinese restaurant and 6.2 for the testing sample using a 9-point hedonic scale (Nam et al., 2018). When air-fried dumplings with rice flour substitution were evaluated (Mun, Baek, and Lee, 2020), they received between 3.3 and 4.3 on a 7-point scale, where 4 was neither liked nor disliked. There were no significant differences among the samples, which may indicate a small number of participants. The somewhat lower liking score may be due to the temperature of the samples served. The dumplings were cooled to ambient temperature for 1 min before serving. However, their later study with soybean flour substitution in dumpling shells (Baek, Mun, and Lee, 2021) resulted in slightly higher acceptability scores between 4.6 and 4.9 on a 7-point scale with the same dumpling fillings and serving conditions. Specific participant groups may give different acceptability scores. Culinary workers evaluated boiled dumpling shells with different levels of Spirulina powder added, and acceptability ranged between 3.9 and 7.9 on a 9-point hedonic scale (Nam and Yoo, 2022).

Table 2.

P-values of 2-way analysis of variance of dumpling acceptability evaluations

| Effect of dumplings | Effect of cooking methods | Effect of interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 86) | |||

| Appearance liking | 0.0002a | < 0.0001 | 0.0745 |

| Overall liking | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0069 |

| Texture liking | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Degree of cooking liking | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0016 |

| Cluster 1 (n = 46): neutral consumers | |||

| Appearance liking | 0.0882 | 0.0004 | 0.1317 |

| Overall liking | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0616 |

| Texture liking | 0.0015 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Degree of cooking liking | 0.0026 | < 0.0001 | 0.0004 |

| Cluster 2 (n = 40): dumpling likers | |||

| Appearance liking | < 0.0001 | 0.0105 | 0.5073 |

| Overall liking | < 0.0001 | 0.0015 | 0.0643 |

| Texture liking | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.1238 |

| Degree of cooking liking | < 0.0001 | 0.0016 | 0.6759 |

ap-value in bold indicates significant effect of treatment or interaction

Fig. 1.

Interaction effect of dumplings sample and cooking methods on acceptability MWO means microwaving. Dumpling samples are abbreviated taking the first alphabets from product and manufacturers’ names. WBC is Wanggyoja (Bibigo, CJ CheilChedang, Seoul, Korea); JBC is Jjin (Bibigo, CJ CheilChedang, Seoul, Korea); GH is Gohyang (Haitai Confectionary Co., Ltd, Seoul, Korea); and SH is Shaolong (Haitai Confectionary Co., Ltd, Seoul, Korea)

Cluster analysis of consumers

Cluster analysis was performed using consumers’ liking scores, and there were two clusters with different acceptability (Table 3). There were no scaling effects, meaning using the original acceptability score and the standardize resulted the same clustering. When consumers were divided, dumpling samples and cooking method interactions were not significant for overall liking (Table 2), and the effects of cooking methods and dumpling types were significant. Cluster 1 (n = 46) had acceptance scores generally in ‘like slightly’ and ‘neither like nor dislike’. In the overall liking evaluation, SH, JBC, and WBC were liked better than GH dumplings. Pan-frying and air-frying were preferred over microwaved or steamed dumplings. Cluster 2 (n = 40) was composed of dumpling likers. JBC, SGH, and WBC dumplings were liked moderately, and GH dumplings were slightly liked. Pan-frying was preferred over air-frying, microwaving, and steaming.

Table 3.

Effect of dumpling products and cooking methods by clusters on dumpling acceptability

| Cluster 1 (n = 46) Neutral consumers |

Cluster 2 (n = 40) Dumpling likers |

|

|---|---|---|

| Dumplings effects | ||

| WBC | 5.6a1 | 7.4a |

| JBC | 5.6a | 7.5a |

| GH | 4.7b | 6.3b |

| SGH | 5.7a | 7.4a |

| LSD | 0.3673 | 0.2979 |

| p-value | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Cooking effects | ||

| Air frying | 5.6a | 7.1b |

| Pan frying | 5.9a | 7.5a |

| MWO | 5.2b | 7.0b |

| Steam | 5.1b | 7.0b |

| LSD | 0.3673 | 0.2979 |

| p-value | < 0.0001 | 0.0015 |

1a, b indicate significant differences between samples for each treatment

Correspondence analysis of texture perception using CATA

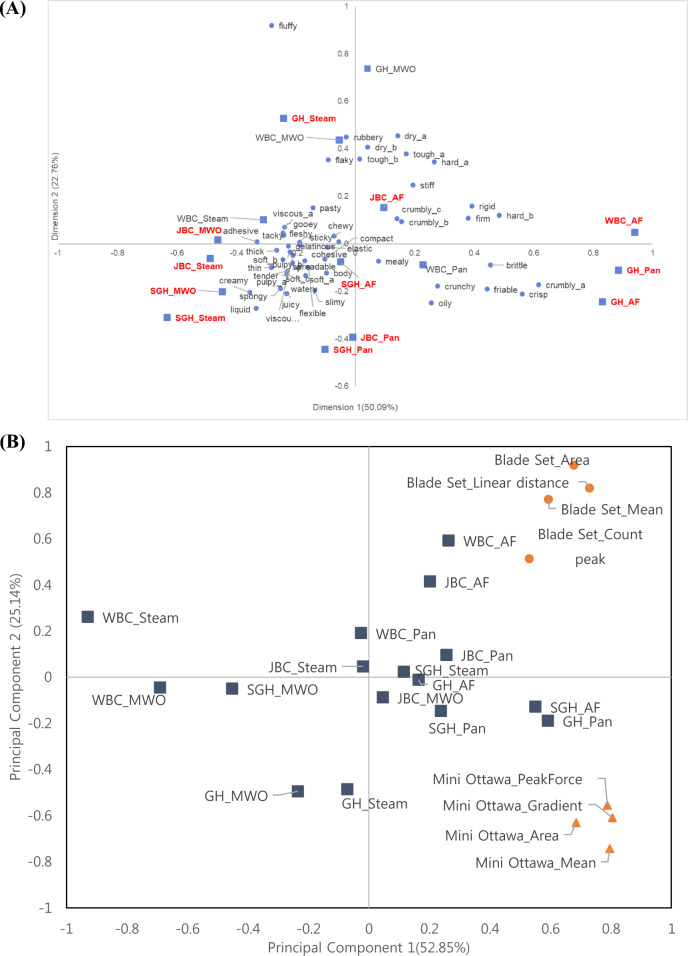

The dumpling samples and CATA terms were visually shown through correspondence analysis (Fig. 2a). Dimensions 1 and 2 account for 72.85% of the variance. Dimension 1 was positively associated with crunch, oily, crumble, crisp, firm, dry, tough, and friable attributes, and negatively related to creamy, spongy, juicy, liquid, soft, viscous, sticky, and thick attributes. Dimension 2 could be explained positively by fluffy, flaky, rubbery, dry, tough, hard, and crumbly attributes and negatively by slimy, oily, spongy, and creamy attributes. In Dimension 1, pan-frying and air-frying had similar characteristics, and steam and microwaving had similar characteristics. SGH dumplings were positioned in quadrant 3, which was positioned near the juicy and creamy attributes. A small amount of oil was placed in n a pan-frying, and the frying pan was heated by conduction, while air-frying was heated by radiant heat and convection. There was a difference between the steam method generated by condensation and convection of steam and the microwave method to vibrate molecules of moisture in food based on the characteristics of texture perception. Dumplings cooked by pan-frying, and air-frying have a crumbly, crisp, and hard texture, while dumplings cooked by steam and microwave have a soft and moist texture. SGH dumplings have oily, creamy, liquid and flexible properties regardless of the cooking method. The most frequently mentioned terms were crisp and soft. These are representative terms mentioned as a difference according to the two cooking methods, in other words, crisp for pan-frying and air-frying and soft for steaming and microwaving.

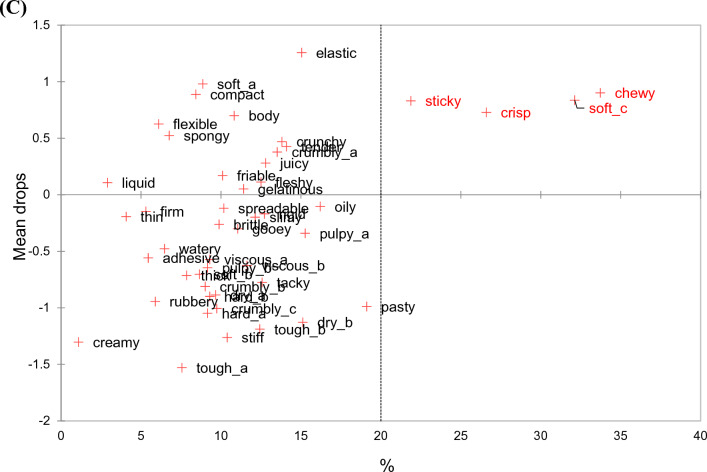

Fig. 2.

Texture evaluation biplots a correspondence analysis using CATA questionnaire on texture perception evaluation, b principal component analysis (PCA) of crispness and firmness measures by texture analyzer values of dumplings cooked using four different cooking methods, and c CATA-penalty analysis demonstrating mean drops and percentage of consumers chose particular terms. MWO means microwaving. Dumpling samples are abbreviated taking the first alphabets from product and manufacturers’ names. WBC is Wanggyoja (Bibigo, CJ CheilChedang, Seoul, Korea); JBC is Jjin (Bibigo, CJ CheilChedang, Seoul, Korea); GH is Gohyang (Haitai Confectionary Co., Ltd, Seoul, Korea); and SH is Shaolong (Haitai Confectionary Co., Ltd, Seoul, Korea). Words following product abbreviation and underscore (_) indicates cooking methods. Steam indicates steaming, MWO indicates microwaving, AF indicates air-frying, and PAN indicates pan-frying

Texture characteristics influencing consumer acceptability of dumplings

CATA-penalty analysis (Fig. 2c) was conducted to determine texture characteristics influencing acceptability (Ares et al., 2014; Ares and Jaeger, 2023). Chewy, soft_c, crisp, and sticky characteristics positively influenced on acceptability (p-value < 0.0001). Percentage of selecting these terms were higher than 20% and mean impact comparing when these texture characteristics were present versus absent ranged between 0.73 to 0.9 on the 9-point hedonic scale. These attributes are “must have.” Attributes located in the negative coordinate of the Y axis are ‘must not have’ and could be product penalties for consumers (Yang and Lee, 2020), however, none of these demonstrated significant impact on disliking. In addition, it is unclear whether these texture was perceived from dumpling shells or fillings, or as a whole.

Instrumental texture analysis

The area, count peak, linear distance, and mean were measured to determine the crispness of the surface of the dumplings (Table 4). Area refers to the energy used to cut dumplings. The interaction between the dumplings and cooking methods was significant (p < .0001). The effects of the dumpling sample and cooking method differed depending on the combination. Overall, pan-frying and air-frying used more energy than microwave and steaming for cutting, except for the SGH dumplings. The value of the count peak was significant in the interaction between the dumplings and cooking method (p < .0001). The effects of the dumpling sample and cooking method differed depending on the combination. Pan-frying and air-frying had more peaks than microwave and steaming. Linear distance was significant in the interaction between dumplings and cooking methods (p < .0001). The linear distance between pan-frying and air-frying was greater than between microwave and steaming. The mean, which indicates average strength, was also significant in the interaction according to dumpling and cooking methods (p < .0001). The average strength of air-frying was generally the highest. The SGH dumplings changed the mean strength differently from the other samples.

Table 4.

Crispness of dumpling shells and firmness of dumpling stuffing measured by texture analyzer TA.XTPlusC measured

| Cooking method | WBC | JBC | GH | SGH | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | ||

| Crispness | |||||||||

| Microwaving | Area (g.sec) | 1073.6 | 203.2 | 2909.8 | 714.3 | 709.8 | 228.3 | 1661.2 | 379.8 |

| Count peak (g.sec) | 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 1.4 | |

| Linear distance (g) | 999.8 | 196.3 | 1982.5 | 620.2 | 925.2 | 242.6 | 1335.3 | 591.6 | |

| Mean (g) | 151.1 | 23.5 | 509.7 | 132.0 | 123.0 | 34.4 | 262.2 | 111.8 | |

| Steaming | Area (g.sec) | 1331.1 | 350.0 | 2921.9 | 830.8 | 1217.7 | 511.7 | 3590.1 | 591.8 |

| Count peak (g.sec) | 4.7 | 4.0 | 15.6 | 19.9 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 1.1 | |

| Linear distance (g) | 1300.4 | 420.5 | 2695.6 | 507.8 | 1412.7 | 255.7 | 1933.8 | 259.7 | |

| Mean (g) | 155.3 | 69.9 | 256.7 | 232.2 | 181.7 | 91.9 | 609.1 | 124.7 | |

| Air-frying | Area (g.sec) | 4530.5 | 1306.4 | 4610.7 | 1277.9 | 2300.5 | 483.4 | 3795.4 | 1040.8 |

| Count peak (g.sec) | 25.4 | 13.6 | 5.6 | 4.9 | 21.3 | 10.8 | 9.6 | 8.6 | |

| Linear distance (g) | 5183.8 | 2252.7 | 4449.8 | 1908.6 | 3492.6 | 1181.0 | 3398.6 | 1319.8 | |

| Mean (g) | 558.3 | 204.6 | 682.5 | 318.5 | 279.8 | 159.7 | 529.9 | 296.7 | |

| Pan-frying | Area (g.sec) | 3583.1 | 587.1 | 3649.3 | 674.0 | 2762.3 | 731.8 | 3091.1 | 684.0 |

| Count peak (g.sec) | 8.4 | 3.4 | 7.8 | 3.2 | 20.8 | 7.2 | 10.9 | 7.1 | |

| Linear distance (g) | 2989.6 | 915.6 | 3169.9 | 1057.1 | 4218.2 | 2082.3 | 2798.8 | 624.1 | |

| Mean (g) | 437.4 | 135.9 | 619.9 | 197.6 | 304.4 | 200.8 | 335.3 | 213.8 | |

| Firmness | |||||||||

| Microwaving | Area (g.sec) | 2864.9 | 700.1 | 4052.7 | 863.3 | 4288.0 | 1016.4 | 3051.1 | 799.1 |

| Mean (g) | 594.9 | 112.2 | 837.6 | 144.6 | 856.1 | 202.6 | 648.1 | 170.2 | |

| Gradient (g.sec) | 237.9 | 27.5 | 322.9 | 48.2 | 310.1 | 84.7 | 282.1 | 38.8 | |

| Peak force (g) | 1135.4 | 129.5 | 1560.3 | 255.0 | 1559.0 | 424.9 | 1335.2 | 168.5 | |

| Steaming | Area (g.sec) | 2124.2 | 992.9 | 3602.2 | 580.5 | 4090.6 | 674.1 | 3641.7 | 1027.8 |

| Mean (g) | 431.5 | 197.7 | 753.1 | 59.7 | 937.2 | 135.1 | 788.9 | 215.4 | |

| Gradient (g.sec) | 183.2 | 49.7 | 316.3 | 31.7 | 310.1 | 32.9 | 360.5 | 61.9 | |

| Peak force (g) | 904.9 | 245.2 | 1505.5 | 169.6 | 1557.9 | 163.7 | 1660.5 | 234.6 | |

| Air-frying | Area (g.sec) | 3646.0 | 573.9 | 3745.1 | 760.9 | 4091.5 | 1188.3 | 4386.4 | 732.9 |

| Mean (g) | 739.3 | 94.2 | 749.3 | 150.8 | 818.2 | 237.5 | 919.6 | 113.6 | |

| Gradient (g.sec) | 265.4 | 34.9 | 287.8 | 47.0 | 324.6 | 21.6 | 430.2 | 50.6 | |

| Peak force (g) | 1312.4 | 203.3 | 1444.2 | 236.9 | 1628.8 | 107.5 | 2043.1 | 224.7 | |

| Pan-frying | Area (g.sec) | 3990.1 | 1955.3 | 4186.0 | 407.6 | 3669.5 | 819.4 | 4224.7 | 835.6 |

| Mean (g) | 694.5 | 190.5 | 854.1 | 92.7 | 930.2 | 480.2 | 905.9 | 149.8 | |

| Gradient (g.sec) | 260.4 | 77.2 | 323.3 | 26.1 | 431.4 | 181.4 | 361.6 | 48.3 | |

| Peak force (g) | 1482.1 | 743.3 | 1591.8 | 131.7 | 2585.7 | 1668.1 | 1682.7 | 217.0 | |

Crispness value was measured with Blade Set probe

Firmness value was measured with Mini Ottawa cell probe

The area, mean, gradient, and peak force were measured to determine the firmness of the filling inside the dumplings (Table 4). The area refers to the total amount of energy used for pressing. The interaction between dumplings and the cooking method was not significant (p = 0.0669). The effects of the dumpling sample and cooking method did not differ depending on the combination. There was a significant difference between the dumplings (p = 0.003). The mean, which is the average force, was also the same as that of the area. The gradient indicates the degree of hardness of the oil, and the interaction between the dumplings and cooking methods was significant (p = 0.0014). The effects on the dumpling sample of the cooking method differed depending on the combination. WBC exhibited the lowest firmness. Peak force refers to the maximum force, and the interaction between the dumplings and cooking methods was significant (p = 0.0341). The four values of each of the crispness and firmness values were highly correlated with each other, but there was no correlation between the crispness and firmness values. Crispness was mainly determined by the dumpling shell, which would have been influenced by the four different cooking methods. Because firmness was measured on dumpling fillings without the shell, dumplings influenced it independent of the cooking methods (Fig. 2b). Other dumpling shell studies have evaluated boiled dumpling shell using texture profile analysis (TPA) measuring characteristics such as hardness, springiness, cohesiveness, chewiness, stickiness (Nam and Yoo, 2022; Baek, Mun, and Lee, 2021; Mun, Baek, and Lee, 2020) and brittleness. Similarly, for gnocchi, only boiling method was used for TPA (Merlino et al, 2022). Therefore, a direct comparison with the current research would be difficult.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of dumpling samples and texture analyzer values

Each of the four values measuring crispness and firmness had many values that were correlated with each other. Highly correlated values for crispness were the mean and area, area and linear distance, linear distance, and count peak. Highly correlated values for firmness were the mean and area, mean and peak force, peak force and gradient, and gradient and mean. There was little correlation between crispness and firmness, as they measured different parts of the dumplings. Texture analyzer values were distributed on the positive side of PC1 (Fig. 2b). Pan-frying and air-frying were located on the positive side of PC1. Steaming and MWO were located on the negative side of PC1. WBC air-frying and JBC dumpling air-frying correlated with crispness.

Similarity between sensory evaluation results and PCA

The RV coefficient showing the similarity between the CA of the consumer texture perception and the PCA of analytical texture data was very low of 0.055 (Fig. 2a & b). The similarity is low, which could be because analytical texture measurement was separated between the dumpling shell and fillings, whereas consumers chew dumplings as a whole. Although correlation shown as RV coefficient was very low between consumer texture perception and analytical measure, using both would be beneficial in further understanding.

A study on consumer acceptability of frozen dumplings was conducted by varying the four dumpling products and four cooking methods: pan-frying, air-frying, steaming, and microwaving. An interaction between dumpling type and cooking methods was found in overall liking, texture liking, and degree of cooking liking. Consumers can be clustered into neutral consumers or dumpling likers. However, their preferences for dumpling products were very similar between consumer clusters. When divided, the effects of both cooking methods and dumpling products were significant. Neutral consumers liked both pan-frying and air-frying better than steaming and microwaving, whereas dumpling likers preferred pan-frying over all other cooking methods. Texture characteristics were clearly differentiated between dumpling products and cooking methods. The limitation of this study is that it did not evaluate texture perception for dumpling shells and fillings separately, making it difficult to know where the texture derived from. Other characteristics of samples, such as dumpling shell thickness and dumpling shell-to-filling weight ratio could be helpful in understanding consumers’ data. In contrast to previous research on dumpling dough texture, dumpling shells and fillings were analyzed using a texture analyzer after cooking, and the crispness and firmness of each of the four values measuring crispness and firmness were correlated with each other. In future, consumer texture perception measure could consider separating dumpling shells and fillings and further study the relationship between consumer preferences for sensory characteristics other than cooking methods.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any funding. Authors would like to thank Yejin Kim and Woojeong Gim, who helped conducting consumer tests.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The first author currently works at LG Electronics, and one of the items of cooking equipment is made by LG Electronics. However, this study compares cooking methods rather than cooking devices.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at Pusan National University (PNU IRB/2022_55_HR).

Consent to participate

Received.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adams J, Williams A, Lancaster B, Foley M. Advantages and uses of check-all-that-apply response compared to traditional scaling of attributes for salty snacks. Pangborn Sensory Science Symposium. 2007;12:16. [Google Scholar]

- Ares G, Dauber C, Fernández E, Giménez A, Varela P. Penalty analysis based on CATA questions to identify drivers of liking and directions for product reformulation. Food Quality and Preference. 2014;32A:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2013.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ares G, Jaeger SR. Check-all-that-apply (CATA) questions with consumers in practice: Experimental considerations and impact on outcome. In: Delarue J, BenLawlor J, editors. Rapid sensory profiling techniques. Woodhead Publishing; 2023. pp. 257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Bae EJ. Current status and prospect of dumpling industry. Seoul: East Asian Dietary Society Conference; 2008. pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Baek M, Mun S, Lee KA. Physicochemical and sensory attributes of dumpling shells with soybean flour substitution. Korean Journal of Food Cookery Science. 2021;37(2):164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop J. How to make Asian dumplings. Natural Health. 25: 46+ (1995, March-April). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A16650987/AONE?u=keris204&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=c67073a0. Accessed 31 Jul 2023

- Bok HJ. The literary investigation on mandu (dumpling)-types and cooking methods of mandu (dumpling) during the Joseon era (1400–1900’s) Korean Journal of Dietary Culture. 2008;23(2):273–292. [Google Scholar]

- Chang HJ, Whang YK. Product development and market testing of ready-to-eat mandu with pond-snail as a health food. Korean Journal Community Nutrition. 2006;11(5):650–660. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger SR, Beresford MK, Paisley AG, Antúnez L, Vidal L, Cadena RS, Giménezb A, Ares G. Check-all-that-apply (CATA) questions for sensory product characterization by consumers: Investigations into the number of terms used in CATA questions. Food Quality and Preference. 2015;42:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2015.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong HK. A historical study of dumpling culture. Journal of the East of Asian Dietary Life. 2008;1:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- June DT. Quality characteristics of dumpling shell with addition of green tea powder. Sejong: Sejong University; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim GO, Lee YC. Sensory evaluation of food. Seoul: Hakyeon Publishers; 2008. pp. 133–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kim JG, Kim JS. Changes of internal temperature during the cooking process of dumpling (mandu) Korean Journal of Human Ecology. 2013;22(3):485–492. doi: 10.5934/kjhe.2013.22.3.485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Kim KBB, Park IS. Perceptions of mandu and usage behaviors by mandu type. Journal of the East of Asian Dietary Life. 2009;15(9):690–702. [Google Scholar]

- Kim KS, Lee MJ, Han BJ. A study of the types of mandoo and its cooking methods in the old cooking books – Focused on the old cooking books issued in 1600 to 1950. Journal of the East of Asian Dietary Life. 1999;9(1):3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lee TH. Current status and prospects of the frozen food industry. Food Science and Industry. 1991;24(3):3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ, Jung HO, Lee MY, Chang HC. Characteristics of Mandu with ripened Korean cabbage Kimchi. Korean Journal of Food Preservation. 2012;19(2):209–215. doi: 10.11002/kjfp.2012.19.2.209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YS, Park HR, Han GJ. Comparison of preference for convenience and dietary attitude in college students by sex in Seoul and Kyunggi-do area. Journal of the Korean Dietetic Association. 2005;11(1):11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Merlino J, Tripodi G, Cincotta F, Prestia O, Miller A, Gattuso A, Verzera A, Condurso C. Technological, nutritional, and sensory characteristics of Gnocchi enriched with hemp seed flour. Foods. 2022;11(18):2783. doi: 10.3390/foods11182783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyners M, Castura JC, Carr BT. Existing and new approaches for the analysis of CATA data. Food Quality and Preference. 2013;30(2):309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2013.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Food Code 2022-76 23-3: 324 (2021) https://various.foodsafetykorea.go.kr/fsd/#/ext/Document/FC?searchNm=%EB%A7%8C%EB%91%90&itemCode=FC0A006001002A048. Accessed 11 Dec 2022

- Mun S, Baek M, Lee KA. Effects of rice flour substitution levels on the gluten formation, textural properties and sensory attributes of dumpling shell. Korean Journal of Food Cookery Science. 2020;36(5):492–497. doi: 10.9724/kfcs.2020.36.5.492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nam DH, Ku YA, Ahn AA. A study on strategic proposals to improve purchase behavior of home meal replacement(HMR): based on the Importance Performance Analysis. The Academy of Customer Satisfaction Management. 2021;23(3):1–19. doi: 10.34183/KCSMA.23.3.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nam PS, Yoo SS. Quality characteristics of dumpling shell with addition of Spirulina powder. Culinary Science and Hospitality Research. 2022;28(7):23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nam S, Yeo I, Lee S, Cho J, Min YJ, Go HM, Kim HS (2018) Dumpling production methods with high juiciness. Patent KR10-2018-0090239A

- Peryam DR, Pilgrim FJ. Hedonic scale method of measuring food preferences. Food Technology. 1957;11:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Peryam DR, Girardot NF. Advanced taste-test method. Food Engineering. 1952;24(7):58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Roh TW, Choi JH, Kim JG, Lee KM. Bibigo wang gyoja, the center of the K-food craze in the US: The case of CJ CheilJedang’s acquisition of Schwan’s company. Korea Business Review. 2021;25(3):35–60. doi: 10.17287/kbr.2021.25.3.35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seo YH. Current status and prospects of the frozen dumpling market. Food Preservation and Processing Industry. 2016;15(2):8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Smewing J. Texture analysis in action: The blade set (2014a) https://textureanalysisprofessionals.blogspot.com/2014/12/texture-analysis-in-action-blade-set.html. Accessed Mar 05, 2023

- Smewing J, Texture analysis in action: The Miniature Kramer/Ottawa Cell (2014b) https://textureanalysisprofessionals.blogspot.com/2014/11/texture-analysis-in-action-miniature.html. Accessed Mar. 05, 2023

- Wang N, Panozzo J, Wood J, Malcolmson L, Arganosa G, Baik B-K, Driedger D, Han J. AACCI Approved methods technical committee report: Collaborative study on a method for determining firmness of cooked pulses (AACCI Method 56-36.01) Cereal Foods World. 2012;57:230. doi: 10.1094/CFW-57-5-0230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J-E, Lee J. Consumer perception and liking, and sensory characteristics of blended teas. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2020;29:63–74. doi: 10.1007/s10068-019-00643-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.