Abstract

Introduction

Birth asphyxia is a leading cause of neonatal mortality in sub‐Saharan Africa. The relationship to grand multiparity (GM), a controversial pregnancy risk factor, remains largely unexplored, especially in the context of large multinational studies. We investigated birth asphyxia and its association with GM and referral in Benin, Malawi, Tanzania and Uganda.

Material and methods

This was a prospective cross‐sectional study. Data were collected using a perinatal e‐Registry in 16 hospitals (four per country). The study population consisted of 80 663 babies (>1000 g, >28 weeks’ gestational age) delivered between July 2021 and December 2022. The primary outcome was birth asphyxia, defined by 5‐minute appearance, pulse, grimace, activity and respiration score <7. A multilevel and stratified multivariate logistic regression was performed with GM (parity ≥5) as exposure, and birth asphyxia as outcome. An interaction between referral (none, prepartum, intrapartum) and GM was also evaluated as a secondary outcome. All models were adjusted for confounders. Clinical Trial: Pan African Clinical Trial Registry 202006793783148.

Results

Birth asphyxia was present in 7.0% (n = 5612) of babies. More babies with birth asphyxia were born to grand multiparous women (11.9%) than to other parity groups (≤7.6%). Among the 76 850 cases included in the analysis, grand multiparous women had a 1.34 times higher odds of birth asphyxia (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.17–1.54) vs para one to two. Grand multiparous women referred intrapartum had the highest probability of asphyxiation (13.02%, 95% CI 9.34–16.69). GM increased odds of birth asphyxia in Benin (odds ratio [OR] 1.37, 95% CI 1.13–1.68) and Uganda (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.02–1.64), but was non‐significant in Tanzania (OR 1.44, 95% CI 0.81–2.56) and Malawi (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.67–1.44).

Conclusions

There is some evidence of an increased risk of birth asphyxia for grand multiparous women having babies at hospitals, especially following intrapartum referral. Antenatal counseling should recognize grand multiparity as higher risk and advise appropriate childbirth facilities. Findings in Malawi suggest an advantage of health systems configuration requiring further exploration.

Keywords: high‐risk, low‐income country, obstetrics, pregnancy, pregnancy birth

Babies of grand multiparous women who are referred intrapartum for hospital delivery had the highest odds of birth asphyxia. These findings confirm that grand multiparas are a high‐risk group in low‐income countries and should be counseled to seek hospital birth.

Abbreviations

- ALERT

Action leveraging evidence to reduce perinatal mortality and morbidity

- ANC

antenatal care

- Apgar

appearance, pulse, grimace, activity and respiration

- CI

confidence interval

- CS

cesarean section

- GM

grand multiparity

- OR

odds ratio

- SD

standard deviation

- SSA

sub‐Saharan Africa

Key message.

Babies of grand multiparous women who were referred intrapartum for hospital birth had the highest odds of birth asphyxia. These findings suggest they are a high‐risk group in low‐income countries and should seek hospital birth to avoid intrapartum referral.

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2020, there were 1.1 million neonatal deaths in sub‐Saharan Africa (SSA). 1 A leading cause was neonatal encephalopathy due to birth asphyxia and trauma. 1 The World Health Organization defines birth asphyxia as the failure to initiate and maintain breathing at birth. 2 A 5‐minute appearance, pulse, grimace, activity and respiration (Apgar) score <7 has been used by the World Health Organization to assess perinatal hypoxia‐ischemia 2 and is a useful predictor of long‐term outcomes for asphyxiated newborns. 3

Obstetric risk factors for birth asphyxia in low‐ and middle‐ income countries include hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, 4 , 5 operative vaginal delivery and cesarean section (CS), 5 , 6 and antepartum hemorrhage. 4 , 6 Distal influencing factors are low maternal literacy 4 , 5 , 6 and poor access to care. 4 , 5 These factors are also often associated with grand multiparity (GM) (parity greater than or equal to five). 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Its association with pregnancy complications has been debated 9 , 11 , 12 since Bethel Solomons cited the dangers of multiparous labor in 1934. 13 Contradictory findings may stem from variations in setting and study population.

Referrals, which link different levels of care in SSA, 14 may modify the relationship between parity and asphyxia. Referrals to higher‐level of care should take place as complications surpass an institution's treatment capabilities. 14 , 15 GM women often have low antenatal care (ANC) attendance and facility‐based birth rates. 10 , 12 , 16 As a result, referrals are made late in the pregnancy course. Referral delays negatively impact birth outcomes, especially in emergencies 17 and could exacerbate the risk for birth asphyxia among GM women.

Most studies assessing odds of birth asphyxia for GM women in SSA are small‐sample, single center experiences. Given the high prevalence of GM—as high as 27% in some regions 18 —and high mortality of birth asphyxia, 1 it is important to examine this relationship as interventions can improve maternal and child health outcomes. Our aims were (1) to assess birth asphyxia incidence, (2) to evaluate the associations between birth asphyxia and GM by referral status and across the four study countries, and (3) to determine whether there is an interaction between GM and referral status. We hypothesized that complications, including birth asphyxia, would be common among the small group of high parity women who utilized hospitals for childbirth, especially among women who were referred.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study used cross‐sectional clinical data collected in a prospective manner as part of the Action Leverage Evidence to Evidence to Reduce Perinatal MorTality and Morbidity (ALERT) trial e‐Registry. A detailed description of the study protocol has been published. 19 To ensure transparent reporting, we followed the STROBE guidelines in conducting and reporting this prospective cross‐sectional study.

Our study included 16 hospitals in Benin, Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda. Country characteristics are described (Table S1). Hospitals were purposely recruited into the ALERT trial in March 2020 to reflect a range of typical hospitals in SSA, including both private and private‐not‐for‐profit hospitals, and to improve generalizability. Other hospital selection criteria included availability of CS and blood transfusion—to ensure capture of the full range of obstetric services—and more than 2500 annual births—for adequate data collection. This is explained in more detail in our protocol paper. 19 Hospitals are not named to protect the privacy of the participants. Data used for this analysis were collected between July 2021 and December 2022. All women between 13 and 49 years of age who gave birth to a baby weighing over 1000 g in any of the hospitals were included in the study. Women who did not give birth but received care at these sites afterward were excluded.

2.1. Study variables

The primary outcome was birth asphyxia as defined by a 5‐min Apgar score less than seven, 20 a well‐established core outcome also used within the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases. 21

The two primary exposure variables were parity and referral status. Parity includes all previous stillbirths and live births past 28 weeks gestational age. It excludes the current pregnancy, miscarriages, and abortions. Referral status indicated whether a woman was referred to the hospital for birth and at what stage (not referred, referred prepartum, referred intrapartum). Referrals from lower‐level facilities and other hospitals were counted. The reason for referral was not captured. Referral status was also evaluated as part of an interaction term.

Confounders included maternal age, ANC attendance, prepartum complications, intrapartum complications, mode of delivery, presentation, multiple gestation, birthweight, and gestational age, and were selected based on their theorical relationship to the outcome (Figure 1). Maternal age extremes have been linked to obstetric complications that increase the odds for birth asphyxia 22 and older age is common among GM women. ANC attendance reflects access to medical care during pregnancy. Limited ANC, or less than four visits, has been shown to affect pregnancy outcomes. 23 Prepartum complications include hypertensive disorders, cardiac/renal disease, gestational diabetes, diabetes mellitus, malaria, hemoglobin less than 7 g/L, syphilis reactivity, and HIV reactivity. If any complications were present, the variable was coded as “yes.” Intrapartum complications include premature rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, antepartum hemorrhage, ruptured uterus, and fetal distress. These complications were grouped to maintain power. Gestational age and infant birthweight were defined according to World Health Organization standards. 21 Variable categorization is described (Table S2).

FIGURE 1.

Directed acyclic graph depicting independent and dependent study variables.

2.2. Data collection and management

Data collectors were trained by ALERT personnel, and the data collection period followed a piloting and supervision period of 4–6 months. Data were abstracted from national, standardized, paper‐based clinical files including the antenatal card, hospital admission book, clinical notes, and postnatal registries. Abstracted data was entered into a Research Electronic Data Capture registry after birth and/or discharge depending on the hospital. Data collection was performed by trained ALERT midwifery staff, with contracts and compensation varying between countries. Data ranges and branching logic in the e‐Registry were present. Other quality assurance included checks of core process data, cross‐checks with health management information data, continuous standardized data cleaning procedures, and weekly team meetings.

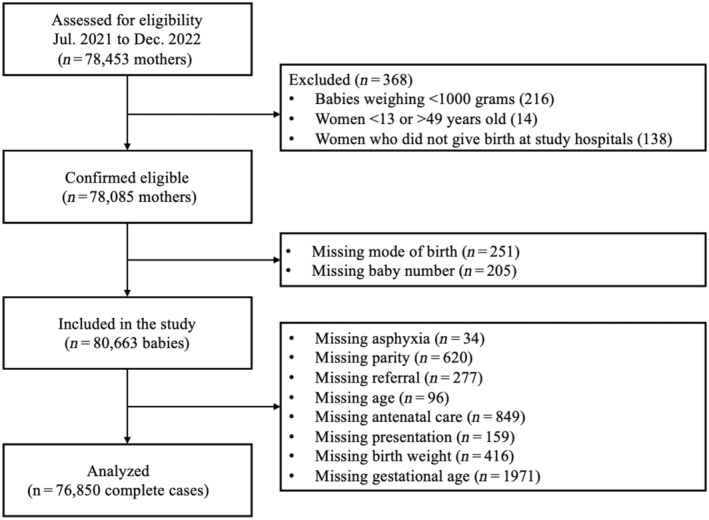

We used STATA BE 17.0 software (StatCorp, College Station, TX, USA) for data processing and analysis. There were 78 453 mothers in the original database prior to enforcing eligibility criteria (368 dropped). Multiple births (eg twins and triplets) were treated as independent observations resulting in a final study population consisting of 80 663 babies (Figure 2). Variables reporting complementary information were cross‐checked and adjusted according to level of evidence. Values outside of predetermined registry ranges were recoded as missing (Table S2).

FIGURE 2.

Flowchart to arrive at analyzed population.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Characteristics of the study population were summarized with respect to country and parity: categorical variables using frequencies, proportions expressed as a percent, and Pearson's Chi‐squared test; discrete continuous variables using mean, standard deviation (SD), and analysis of variance. The following variables were included in all logistic regression models: birth asphyxia, GM, referral, and all confounders (maternal age, ANC attendance, prepartum complications, intrapartum complications, mode of delivery, presentation, multiple gestation, birthweight, and gestational age).

A multilevel model was used to evaluate odds of birth asphyxia and account for clustering of data originating from different hospitals and countries; all covariates listed above were used at both levels of the multilevel model. The multilevel model was a better fit for the data than a simple logistic model according to a likelihood ratio test (p = 0.0111). A bivariate analysis was run first, followed by a multivariate analysis. Covariates significant at p < 0.05 in the bivariate model were tested for collinearity using Spearman's correlation coefficient for non‐parametric (ordinal) data and considered for removal if |r| > 0.6. 24 Although there was collinearity between parity and age (r = 0.749), age was kept because it is independently associated with complications also related to high parity. 25 , 26 Multivariate analysis was performed to produce adjusted odds ratios (OR) and confidence intervals (CI). A second multilevel analysis was run with the addition of an interaction term between referral and parity. The probability of asphyxia for each combination of parity and referral was evaluated with a marginal analysis. A stratified logistic regression was performed to compare data between countries. Multivariate logistic regression for each of the four countries included all covariates. Interaction analysis was not performed on a country level due to insufficient data among women referred prepartum.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Birth asphyxia incidence

Birth asphyxia was present in 5612/80663 (7.0%) babies. There were 4762 (5.9%) deliveries to GM women. More babies with birth asphyxia were born to GM women (11.9%) compared to other parity groups (≤7.6%). GM women tended to be older (35.3, SD 4.8) and attended fewer ANC appointments (3.6, SD 1.7) than less parous women. GM women also had the most pre‐ (27.1%) and intrapartum complications (23.0%), preterm labor (9.8%), and malpresentation (10.4%). Proportions of CS (26.5%) were comparable for nulliparous women and GM women, but lower than for other multiparous women (>28%). Average time from admission to birth for GM women was 21.1 h, almost double the time it took for less parous groups, which ranged from 10.5 to 11.3 h (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics and obstetric risks by parity of 80 663 babies born in 16 hospitals births across Benin, Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda. Percentages are a proportion of the total births for each parity group.

| Parity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nullipara | Para 1–2 | Para 3–4 | Grand Multipara | Missing | p | |

| Total births | 30 997 | 30 205 | 14 079 | 4762 | <0.1% | — |

| Birth asphyxia | 6.7% | 6.1% | 7.6% | 11.9% | <0.1% | <0.001 |

| Prepartum referrals | 2.9% | 2.3% | 2.5% | 3.6% | 0.3% | <0.001 |

| Intrapartum referrals | 19.1% | 14.3% | 18.8.3% | 27.7% | 0.3% | <0.001 |

| Facility referrals | 20.3% | 14.9% | 19.2% | 27.6% | 0.3% | <0.001 |

| Prepartum complications | 15.7% | 20.1% | 25.3% | 27.1% | None | <0.001 |

| Intrapartum complications | 19.7% | 16.5% | 19.1% | 23.0% | None | <0.001 |

| Preterm labor | 7.1% | 7.1% | 8.3% | 9.8% | <0.1% | <0.001 |

| Cesarean sections | 26.2% | 29.8% | 28.2% | 26.5% | None | <0.001 |

| Operative vaginal deliveries | 1.5% | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.5% | None | <0.001 |

| Malpresentation | 3.6% | 5.6% | 8.1% | 10.4% | 0.2% | <0.001 |

| Multiple gestations | 1.9% | 3.9% | 5.2% | 6.2% | None | <0.001 |

| Male infants | 51.3% | 51.3% | 51.3% | 50.6% | 0.1% | 0.85 |

| Apgar score (mean [SD]) | 9.2 (2.0) | 9.2 (2.1) | 9.0 (2.4) | 8.6 (2.9) | 0.2% | <0.001 |

| Maternal age | 20.2 (3.4) | 25.9 (4.6) | 31.9 (4.9) | 35.3 (4.8) | 0.1% | <0.001 |

| ANC visits | 4.2 (1.7) | 4.1 (1.7) | 4.0 (1.7) | 3.6 (1.7) | 1.1% | <0.001 |

| Admission to birth (h) | 11.3 (19.4) | 10.5 (20.9) | 10.9 (21.8) | 21.1 (23.4) | 8.4% | <0.001 |

| Birthweight (g) | 2877 (523) | 2983 (562) | 2995 (600) | 2999 (632) | 0.5% | <0.001 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 37.9 (2.2) | 38.1 (2.1) | 38.1 (2.2) | 38.0 (2.4) | 2.4% | <0.001 |

Abbreviation: Apgar, appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration.

3.2. Parity and birth asphyxia

We examined 76 850 complete cases. Aside from ANC appointments (1.1%) and gestational age (2.4%), no covariate had more than 1% individual missingness. In the multilevel model, differences between hospitals (interclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = 0.063) accounted for more variation than differences between countries (ICC = 0.017). In the unadjusted bivariate model, GM women had 1.70 (95% CI 1.53–1.89) times higher odds of having a baby with birth asphyxia compared to para one to two women. In the adjusted model, GM women were 1.34 times more likely to have a baby with birth asphyxia (95% CI 1.17–1.54) and no other parity groups had significantly increased odds for birth asphyxia. Women referred prepartum were 2.35 times more likely to have a baby with birth asphyxia compared to non‐referred women (95% CI 2.03–2.72). Intrapartum referrals increased odds for birth asphyxia 2.54 times (95% CI 2.35–2.73). The odds of birth asphyxia increased as ANC visits decreased. Higher odds of birth asphyxia were also seen in women of the highest age group (OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.06–1.38), operative vaginal delivery (OR 2.35, 95% CI 1.93–2.85), and malpresentation (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.29–1.60) when compared to the referents and controlling for other factors (Table 2). Multiple gestation was found to be protective (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.42–0.57).

TABLE 2.

Bivariate and multivariate multilevel logistic regression analysis for birth asphyxia evaluating 76 850 births (complete cases) in 16 hospitals across Benin, Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda.

| Unadjusted model | Adjusted model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Parity index at birth | ||||

| Nullipara | 1.17*** | 1.09–1.25 | 1.02 | 0.94–1.12 |

| Para 1–2 | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Para 3–4 | 1.19*** | 1.10–1.29 | 1.06 | 0.96–1.17 |

| Grand multipara | 1.70*** | 1.53–1.89 | 1.34*** | 1.17–1.54 |

| Referral status | ||||

| Not referred | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Referred prepartum | 3.63*** | 3.17–4.15 | 2.35*** | 2.03–2.72 |

| Referred intrapartum | 3.05*** | 2.84–3.27 | 2.54*** | 2.35–2.73 |

| Maternal age | ||||

| 13–19 | 1.08 | 0.99–1.18 | 0.99 | 0.90–1.09 |

| 20–24 | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| 25–29 | 0.96 | 0.89–1.04 | 1.04 | 0.95–1.14 |

| 30–34 | 1.01 | 0.92–1.10 | 1.05 | 0.93–1.17 |

| 35–50 | 1.30*** | 1.18–1.43 | 1.21** | 1.06–1.38 |

| ANC visits | ||||

| None | 1.95*** | 1.51–2.51 | 1.90*** | 1.46–2.47 |

| 1–3 | 1.53*** | 1.44–1.63 | 1.22*** | 1.14–1.30 |

| 4–7 | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| 8–12 | 0.64*** | 0.52–0.80 | 0.81 | 0.65–1.01 |

| Prepartum complications | ||||

| No | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Yes | 1.48*** | 1.39–1.58 | 1.05 | 0.97–1.13 |

| Intrapartum complications | ||||

| No | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Yes | 4.46*** | 4.20–4.75 | 3.03*** | 2.81–3.26 |

| Mode of birth | ||||

| Spontaneous vaginal | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Cesarean section | 1.15*** | 1.08–1.23 | 0.94 | 0.87–1.00 |

| Operative vaginal | 3.77*** | 3.18–4.47 | 2.35*** | 1.93–2.85 |

| Baby presentation | ||||

| Cephalic | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Malpresentation | 2.06*** | 1.88–2.25 | 1.43*** | 1.29–1.60 |

| Multiple gestation | ||||

| Singleton | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Multiple | 1.01 | 0.88–1.16 | 0.49*** | 0.42, 0.57 |

| Birthweight (g) | ||||

| Small | 3.17*** | 2.98–3.38 | 1.70*** | 1.56, 1.85 |

| Normal | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Large | 1.12 | 0.89–1.41 | 1.07 | 0.84, 1.36 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | ||||

| 28–32 | 7.56*** | 6.84–8.36 | 2.31*** | 2.03, 2.61 |

| 33–37 | 1.53*** | 1.43–1.63 | 0.96 | 0.89, 1.03 |

| 38–41 | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| 42–44 | 1.23* | 1.04–1.44 | 1.13 | 0.96–1.34 |

| Country variance | — | — | 0.06 | 0.01–0.68 |

| Hospital variance | — | — | 0.16 | 0.07–0.38 |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

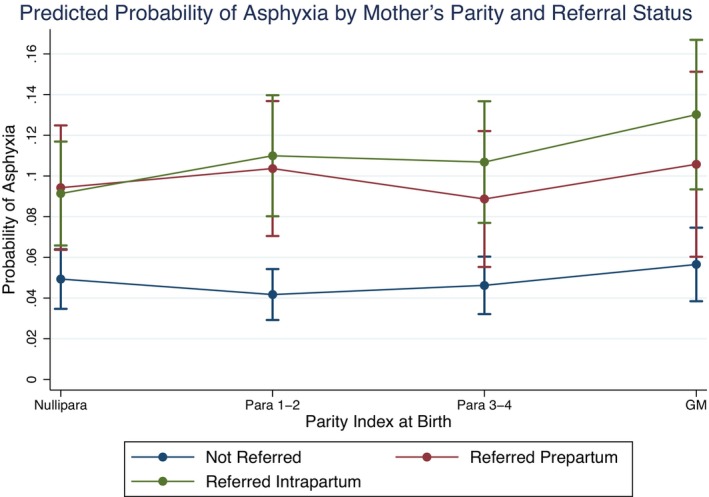

3.3. Parity and referral

GM women had the highest prepartum (3.6%) and intrapartum (27.7%) referral proportions, with prepartum and intrapartum referrals in other parity groups ranging from 2.3% to 2.9% and 14.3% to 19.1% respectively (Table 1). Among women referred prepartum, 23.1% (n = 40/173) of babies born to GM women were asphyxiated compared to 13.8% (n = 123/892) among nulliparous women. For women referred intrapartum, 21.9% (n = 289/1318) of babies born to GM women were asphyxiated compared to 13.0% (n = 773/5932) among nulliparous women. Prepartum and intrapartum referred women, regardless of parity, had predicted rates of birth asphyxia around twice as high as all women who were not referred (Figure 3). GM women who were referred intrapartum had the highest predicted probability of having a baby with birth asphyxia (13.02%, 95% CI 9.34–16.69) among all women. GM women also had the highest probability of birth asphyxia within the other two referral groups: 10.58% (95% CI 6.03–15.12) among women referred prepartum and 5.65% (95% CI 3.84–7.46) among women who were not referred. Para one to two women who were not referred had the lowest predicted probability of having a baby with birth asphyxia (4.17%, 95% CI 2.92–5.43) (Table S3).

FIGURE 3.

Predicted probability of birth asphyxia by referral status and parity using margins of multilevel logistic regression for 76 850 births (complete cases) in 16 hospitals across Benin, Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda.

3.4. Parity and birth asphyxia by country

Birth asphyxia incidence was highest in Benin (n = 1997, 11.6%) and Uganda (n = 1979, 8.8%), and lowest in Malawi (n = 1250, 4.6%) and Tanzania (n = 386, 2.9%). Benin and Uganda had more GM women in their study population (>7.6%) than the other countries (≤3.8%). Benin and Uganda also had higher proportions of other risk factors than Malawi and Tanzania including intrapartum referrals (>15.7% vs. <8.6%), intrapartum complications (>20.1% vs. <12.1%), preterm labor (>6.8% vs. <4.5%), and malpresentation (>4.8% vs. <2.8%) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Demographic characteristics and obstetric risks by country of 80 663 babies born in 16 hospitals births across Benin, Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda. Percentages are a proportion of the total births for each parity group.

| Country | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | Malawi | Tanzania | Uganda | Missing | p | |

| Total births | 17 280 | 27 499 | 13 381 | 22 503 | None | — |

| Birth asphyxia | 11.6% | 4.6% | 2.9% | 8.8% | <0.1% | <0.001 |

| Grand multiparas | 9.2% | 3.8% | 3.2% | 7.6% | 0.8% | <0.001 |

| Prepartum referrals | 6.9% | 2.1% | 1.1% | 1.0% | 0.3% | <0.001 |

| Intrapartum referrals | 46.1% | 8.6% | 3.9% | 15.7% | 0.3% | <0.001 |

| Facility referrals | 47.2% | 10.6% | 4.6% | 14.6% | 0.3% | <0.001 |

| Prepartum complications | 38.8% | 11.9% | 14.4% | 17.8% | None | <0.001 |

| Intrapartum complications | 33.6% | 12.1% | 10.1% | 20.1% | None | <0.001 |

| Preterm labor | 16.2% | 4.5% | 3.6% | 6.8% | <0.1% | <0.001 |

| Cesarean sections | 44.4% | 17.6% | 28.7% | 27.9% | None | <0.001 |

| Operative vaginal deliveries | 1.7% | 2.0% | 0.9% | 0.7% | None | <0.001 |

| Malpresentation | 13.8% | 2.4% | 2.8% | 4.8% | 0.2% | <0.001 |

| Multiple gestation | 7.5% | 1.7% | 2.0% | 3.6% | None | <0.001 |

| Male infants | 52.1% | 51.6% | 50.9% | 50.3% | 0.1% | 0.004 |

| Apgar score (mean [SD]) | 8.6 (2.7) | 9.5 (1.7) | 9.7 (1.5) | 8.7 (2.4) | 0.2% | <0.001 |

| Maternal age | 27.1 (6.1) | 23.9 (6.3) | 26.3 (7.2) | 25.2 (5.9) | 0.1% | <0.001 |

| ANC visits | 4.4 (1.8) | 3.6 (1.6) | 5.2 (1.4) | 3.8 (1.5) | 1.1% | <0.001 |

| Admission to birth (h) | 15.9 (24.9) | 7.7 (19.1) | 8.4 (16.5) | 12.5 (19.9) | 8.4% | <0.001 |

| Birthweight (g) | 2777 (584) | 2940 (495) | 2931 (501) | 3087 (616) | 0.5% | <0.001 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 37.9 (2.5) | 37.6 (1.6) | 38.5 (2.3) | 38.3 (2.3) | 2.4% | <0.001 |

Abbreviation: Apgar, appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration.

After adjustment for confounders, the association between GM and asphyxia was significant in Benin and Uganda (Table S4). In Benin, babies born to GM women were 1.37 times more likely to have birth asphyxia compared to the reference (95% CI 1.13–1.68). In Uganda, the odds were 1.29 (95% CI 1.02–1.64). In Tanzania (OR 1.44, 95% CI 0.81–2.56) and Malawi (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.67–1.44) odds were not significant (Figure 4). Intrapartum referrals increased the odds for birth asphyxia in all countries (p < 0.001), but least in Malawi. Prepartum referrals were a significant risk factor in all countries except Malawi (OR 1.37, 95% CI 0.95–1.96). Malawi was also the only country where multiple gestation was not found to be protective (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.74–1.50).

FIGURE 4.

Odds of asphyxia for each country by parity and referral status using multivariate logistic regression of 76 850 births (complete cases) in 16 hospitals across Benin, Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda.

4. DISCUSSION

We believe this is the first prospective, multinational study to analyze the association between GM and birth asphyxia in SSA. We report that across 76 850 hospital births in Benin, Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda, GM women were 1.34 times more likely to have babies with birth asphyxia compared to para one to two women. Babies of GM women referred intrapartum had the highest predicted probability of asphyxiation at 13.02%, over three times higher than that of non‐referred para one to two women. The odds of birth asphyxia for GM women ranged from 0.98 in Malawi to 1.37 in Benin. Results were only significant in Benin and Uganda, where asphyxia and referral rates were higher (>8%, >15% respectively) compared to Malawi and Tanzania (<5%, <9%). We will examine these findings with respect to the unique biological, sociodemographic, and health system factors associated with GM women in SSA.

We found some evidence that GM is associated with poor neonatal outcomes when compared to other parity groups. Most small, hospital‐based studies from low‐income countries support our findings, 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 28 , 29 with the exception of a Nigerian study that refutes risk in GM given sufficient antenatal and intrapartum care. 7 However, their exclusion of women without ANC limits external validity and may disproportionately affect GM women at highest risk for poor outcomes. We found limited ANC to be an independent risk factor for birth asphyxia, and most common among GM women. GM women are also at risk for uterine rupture secondary to strong uterine contractions. 30 Strong uterine contractions may cause fetal distress during labor and lead to poor outcomes if not intervened upon. 31 Average GM labor times of 21.1 h, twice those of lower parity women, and a CS rate of only 26.5% indicate that these physiologic complexities in GM women may not have been addressed in time to prevent birth asphyxia in neonates.

GM women had the highest proportion of intrapartum referrals relative to other parity groups. A two‐fold increase in predicted rates of birth asphyxia among women who were referred, with the worst outcomes among GM women referred intrapartum, underscores the impact of care delays, especially in the GM group. Although there are policy guidelines for GM women on giving birth in higher level facilities, 32 , 33 the risk factor is poorly recognized by women, their families, and health care providers. 15 GM is linked to poverty; the complex interaction of having large families and limited economic means further results in limited proportions of women using hospitals for childbirth unless labor complications arise. 16 As early medical intervention during labor is critical to preventing severe birth asphyxia, 34 delayed hospital arrival increases risk for having an asphyxiated newborn. This also means that the GM population in our study is likely more complicated than the GM population who does not attend the hospital for childbirth. An ANC policy shift in the early 2000s probably plays a role in risk perception related to GM. Transitioning away from a goal of risk stratification to service delivery (eg malaria prevention and provision of iron supplementation), 35 , 36 may have removed emphasis from identifying certain pregnancy risks and initiating timely referrals. While all women should be encouraged to give birth in facilities, we believe that refocusing ANC on risk identification—with advice to give birth in a higher level facility for women at higher risk (for example in GM)—can improve outcomes. Notably, outcomes for the small cohort of women referred prepartum were only slightly better. For similar reasons listed above, referral in this cohort was probably only initiated after the onset of complications.

Findings in Benin, Uganda, and Tanzania generally mirrored the combined analysis, though CIs in Tanzania were large owing to the small number of GM women in the dataset. Malawi was the outlier: multiple gestation was not protective, intrapartum referral only marginally increased odds of birth asphyxia, and there was substantial overlap in CIs for odds of birth asphyxia among GM women and nulliparas. Although Malawi has the weakest economy and largest rural population—factors associated with poor health outcomes 37 —it also has relatively generous healthcare funding and large external donor programs. 38 These contextual differences may enable more women to attend ANC, follow referral advice, and seek out hospital birth than in other low‐income countries, and perhaps even on a level more comparable to high‐income countries. Evidence of increased and earlier healthcare utilization is reflected in the high institutional birth rate of 91%, the highest among countries in this study, 39 and improved outcomes among referred women. As healthcare access improves and care delays become less important factors, it is possible that the inherent biological risks of nulliparity and multiple gestation outweigh those of GM. However, it should also be noted that both Tanzania and Malawi had lower proportions of referral and other risk factors (complications, preterm labor, and malpresentation). It is difficult to say whether GM women in Malawi are at lower risk and preventative actions are better, or whether high‐risk women do not reach hospitals for childbirth. This would make sense in Tanzania, where care is often provided in health centers—additional structures that are better equipped. Further and more robust study of country differences is needed but beyond the scope of this paper.

There were several other notable findings. We found multiple pregnancy to be protective for birth asphyxia in our population. This was surprising because multiple pregnancy is associated with well‐known complications. 36 We suspect that risk stratification at ANC, early referral, and community acceptance of associated risk permitted preventative intervention for our hospital‐based population. Whereas policy guidelines consider GM “medium risk” with advice for continued ANC and birth at a health center or hospital, multiple gestation is “high risk” and immediate referral to specialty care and birth at a facility with comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care services are advised. 32 , 33

The high odds for birth asphyxia among GM women, but not nulliparous women, were also unexpected, as there is typically a j‐shaped risk distribution described for parity. 40 Nulliparous women more often see cephalopelvic disproportion, which contributes to their birth risk. While CS rates were comparable to GM women for this group at 26.2%, the average labor time for nulliparous women was only 11.3 h. Our data do not differentiate between primary and emergency CS, but it is possible that nulliparas were prioritized for primary CS in our hospital population, thereby preventing sequelae of emergency complications associated with birth physiology. These patterns are probably attributable to an international agenda that places major emphasis on mitigating the dangers of adolescent and first‐time pregnancy, often leaving the risk in old age and high parity forgotten. 23 , 35 , 41

Finally, there was a significant difference in odds for asphyxia between GM women and nulliparas in Benin. This might be because the difference in CS rates between these two groups was largest in Benin, with nulliparas receiving 8% more CS than GM women, further highlighting the protective effect of primary CS and risk stratification.

Our study had several important strengths. We used rigorous data collection to measure the relationship between parity, referral, and birth asphyxia. Inclusion of 16 public and private‐not‐for‐profit hospitals in four countries overcomes significant weakness of single‐institution studies. Furthermore, minimal methodological variations between sites allowed for more direct comparison of the socio‐cultural, economic, and healthcare contexts of each country, especially as outcomes were measured according to international standard indicators. While several conditions can cause low Apgar scores, our results indicate that babies of GM women are vulnerable, especially when delays are present.

Some weaknesses are present too. Non‐differential misclassification of parity and Apgar scores would mildly attenuate the observed effect if present. Furthermore, inability to adjust for unknown confounders and cross‐sectional data prevented inference of causality. Data quality limitations also prevented inclusion of confounders like active labor time (high missingness) and uterotonic use (unknown timing of administration). Hospital‐based studies are inherently prone to selection bias and should not be generalized to all GM women. Finally, obstetric care policies are different in each country studied and could be confounders creating unexpected results. Unexpected findings can also be due to large CIs in smaller risk groups. Thus, we cannot exclude chance as an explanation for any of the results obtained, especially when comparing countries.

5. CONCLUSION

In this multi‐country, cross‐sectional analysis, babies of GM women who reached hospitals for childbirth had increased risk of birth asphyxia, especially following intrapartum referrals. Results in Benin and Uganda mirrored the overall findings, while the association was non‐significant in Malawi and Tanzania. After generating context‐specific data on birth asphyxia, GM, and referral patterns, we conclude that efforts should be made to increase awareness that GM women constitute a higher‐risk group in low‐income countries. By promoting ANC attendance among GM women and reinforcing guidelines to give birth at childbirth facilities capable of managing complications, we hope to reduce birth asphyxia rates and avoid the need for intrapartum referral in case complications arise. Further exploration of Malawi, where findings suggest an advantage of health systems configuration, is needed.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Greta Handing was involved in all phases of literature search, data management, design of tables and figures, interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. Manuela Straneo and Claudia Hanson assisted with all these processes, with specific emphasis on data interpretation and writing of the manuscript. Christian Agossou and Phillip Wanduru assisted the statistical analyses. Phillip Wanduru, Bianca Kandeya, Christian Agossou, Muzdalifat S. Abeid, Kristi S. Annerstedt, Claudia Hanson were involved in design and conducting of data collection. For this manuscript, they acted as supervisors and were therefore actively involved in the interpretation and writing of the paper.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study is part of the ALERT‐project which is funded by the European Commission's Horizon 2020 (No 847824) under a call for Implementation research for maternal and child health. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the views of the European Union. This study proposal has been independently peer‐reviewed by the European Union. Open Access funding was provided by Karolinska Institutet.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

ETHICS STATEMENT

ALERT is registered in the Pan African Clinical Trial Registry at 202006793783148. 27 The trial was registered on June 17, 2020, and recruitment started on January 1, 2021. Ethical approval for ALERT was obtained from local and national institutional review boards in Benin, Malawi, Tanzania, Uganda, Sweden, and Belgium: 19 Comité National d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Santé, Cotonou, Bénin (83/MS/DC/SGM/CNERS/ST) (July 20, 2020). College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee, Malawi (COMREC P.04/20/3038) (July 20, 2020). Muhimbili University of Health And Allied Sciences Research and Ethics Committee, Tanzania (MUHAS‐REC‐04‐2020‐118) & The Aga Khan University Ethical Review Committee, Tanzania (AKU/2019/044/fb) (March 21, 2020). School of Public Health research and Ethics Committee (HDREC 808) & Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS1324ES) (August 4, 2020). Karolinska Institutet, Sweden (DNR/2020/01587) (October 18, 2020). The Institutional Review Board at the Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp and The Ethics Committee at the University Hospital Antwerp, Belgium (ITG 1375/20. B3002020000116) (June 29, 2020). Ethics approval from all countries exempted the study from informed individual consent from women, given that data would be de‐identified before incorporation into the e‐Registry. All study procedures were in accordance with respective national ethical standards on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration.

Supporting information

Table S1.

Table S2.

Table S3.

Table S4.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the coordinated efforts of doctors, midwives, and nurses at the recruitment hospitals made this study possible and we are very grateful for their time. We would also like to credit the World Health Organization for artwork used in the graphical abstract. Images were adapted from two infographics published in 2023 titled “Without a change of course, 30 million preventable deaths from childbirth are projected to occur by 2030” and “Every 7 seconds, a woman or newborn dies, or a baby is lost to stillbirth.” 42 The World Health Organization is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this adaptation.

Handing G, Straneo M, Agossou C, et al. Birth asphyxia and its association with grand multiparity and referral among hospital births: A prospective cross‐sectional study in Benin, Malawi, Tanzania and Uganda. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2024;103:590‐601. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14754

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study will be available after December 31st, 2027 at https://alert.ki.se/. Any person wishing to view or use the data prior to this date will need to place a request to use the data to the ALERT steering committee.

REFERENCES

- 1. UN Inter‐Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation . Child Mortality and Stillbirth Estimates [Internet]. ChildMortality.org. https://childmortality.org/

- 2. World Health Organization . Guidelines on Basic Newborn Resuscitation [Internet]. 2012. Geneva: World Health Organization. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/75157

- 3. Casey BM, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. The continuing value of the Apgar score for the assessment of newborn infants. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:467‐471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Igboanugo S, Chen A, Mielke JG. Maternal risk factors for birth asphyxia in low‐resource communities. A systematic review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;40:1039‐1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ahmed R, Mosa H, Sultan M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with birth asphyxia among neonates delivered in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PloS One. 2021;16:e0255488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Desalew A, Semahgn A, Tesfaye G. Determinants of birth asphyxia among newborns in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Health Sci. 2020;14:35‐47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Njoku CO, Abeshi SE, Emechebe CI. Grand multiparity: obstetric outcome in comparison with multiparous women in a developing country. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;7:707‐718. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Geidam AD, Audu BM, Oummate Z. Pregnancy outcome among grand multiparous women at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital: a case control study. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31:404‐408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Agrawal S, Agarwal A, Das V. Impact of grandmultiparity on obstetric outcome in low resource setting. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:1015‐1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alsammani MA, Jafer AM, Khieri SA, Ali AO, Shaaeldin MA. Effect of grand multiparity on pregnancy outcomes in women under 35 years of age: a comparative study. Med Arch. 2019;73:92‐96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Toohey JS, Keegan KA, Morgan MA, et al. The “dangerous multipara”: fact or fiction? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:683‐686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mgaya AH, Massawe SN, Kidanto HL, Mgaya HN. Grand multiparity: is it still a risk in pregnancy? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Solomons B. The dangerous multipara. Lancet. 1934;224:8‐11. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Campbell OMR, Calvert C, Testa A, et al. The scale, scope, coverage, and capability of childbirth care. Lancet. 2016;388:2193‐2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pembe AB, Urassa DP, Darj E, Carlstedt A, Olsson P. Qualitative study on maternal referrals in rural Tanzania: decision making and acceptance of referral advice. Afr J Reprod Health Rev Afr Santé Reprod. 2008;12:120‐131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Straneo M, Beňová L, van den Akker T, Pembe AB, Smekens T, Hanson C. No increase in use of hospitals for childbirth in Tanzania over 25 years: accumulation of inequity among poor, rural, high parity women. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2:e0000345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tukur J, Lavin T, Adanikin A, et al. Quality and outcomes of maternal and perinatal care for 76,563 pregnancies reported in a nationwide network of Nigerian referral‐level hospitals. eClinicalMedicine. 2022;47:101411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ajong AB, Agbor VN, Simo LP, Noubiap JJ, Njim T. Grand multiparity in rural Cameroon: prevalence and adverse maternal and fetal delivery outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Akuze J, Annerstedt KS, Benova L, et al. Action leveraging evidence to reduce perinatal mortality and morbidity (ALERT): study protocol for a stepped‐wedge cluster‐randomised trial in Benin, Malawi, Tanzania and Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Committee Opinion No. 644: The Apgar score. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(126):e52‐e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organization . International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, Fifth Edition. 2015. World Health Organization.

- 22. Londero AP, Rossetti E, Pittini C, Cagnacci A, Driul L. Maternal age and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization . WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience [Internet]. 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; Accessed May 3, 2023. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250796 [PubMed]

- 24. Laerd Statistics Group . Spearman's Correlation in Stata – Procedure, Output and Interpretation of the Output Using a relevant Example [Internet]. Laerd Statistics. Accessed March 9, 2023] https://statistics.laerd.com/stata‐tutorials/spearmans‐correlation‐using‐stata.php#procedure

- 25. Chan BCP, Lao TTH. Effect of parity and advanced maternal age on obstetric outcome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet off Organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102:237‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Simonsen SME, Lyon JL, Alder SC, Varner MW. Effect of grand multiparity on intrapartum and newborn complications in young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:454‐460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. PACTR . PACTR: Pan African Clinical Trials Registry [Internet]. PACTR. Accessed August 31, 2023] https://pactr.samrc.ac.za/

- 28. Muniro Z, Tarimo CS, Mahande MJ, Maro E, Mchome B. Grand multiparity as a predictor of adverse pregnancy outcome among women who delivered at a tertiary hospital in northern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dasa TT, Okunlola MA, Dessie Y. Effect of grand multiparity on adverse maternal outcomes: a prospective cohort study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:959633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Holdcroft A, Snidvongs S, Cason A, Doré CJ, Berkley KJ. Pain and uterine contractions during breast feeding in the immediate post‐partum period increase with parity. Pain. 2003;104:589‐596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leathersich SJ, Vogel JP, Tran TS, Hofmeyr GJ. Acute tocolysis for uterine tachysystole or suspected fetal distress. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2018:CD009770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare . Reproductive and Child Health Card Number 4 (RCHC‐4). Dar es Salaam, the United Republic of Tanzania: Ministry of Health and Social Welfare 2006.

- 33. Ministry of Health . Essential Maternal and Newborn Clinical Care Guidelines for Uganda. R.A.C.H. Department; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Low JA, Pickersgill H, Killen H, Derrick EJ. The prediction and prevention of intrapartum fetal asphyxia in term pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:724‐730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jahn A, Kowalewski M, Kimatta SS. Obstetric care in southern Tanzania: does it reach those in need? Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:926‐932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hanson C, Munjanja S, Binagwaho A, et al. National policies and care provision in pregnancy and childbirth for twins in eastern and southern Africa: a mixed‐methods multi‐country study. PLoS Med. 2019;16:e1002749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1091‐1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. World Health Organization . Global Health Observatory: Data Repository [Internet]. World Health Organization https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main

- 39. UNICEF . UNICEF Data: Monitoring the situation of Children and Women [Internet]. UNICEF: for every child. Accessed December 13, 2022. https://data.unicef.org/resources/resource‐type/datasets/

- 40. Bai J, Wong FWS, Bauman A, Mohsin M. Parity and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:274‐278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gabrysch S, Campbell OM. Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. World Health Organization . WHO Multimedia [Internet]. World Health Organization. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.who.int/multi‐media

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Table S2.

Table S3.

Table S4.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be available after December 31st, 2027 at https://alert.ki.se/. Any person wishing to view or use the data prior to this date will need to place a request to use the data to the ALERT steering committee.