Abstract

Background

Interventions incorporating meditation to address stress, anxiety, and depression, and improve self‐management, are becoming popular for many health conditions. Stress is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and clusters with other modifiable behavioural risk factors, such as smoking. Meditation may therefore be a useful CVD prevention strategy.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of meditation, primarily mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) and transcendental meditation (TM), for the primary and secondary prevention of CVD.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, three other databases, and two trials registers on 14 November 2021, together with reference checking, citation searching, and contact with study authors to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of 12 weeks or more in adults at high risk of CVD and those with established CVD. We explored four comparisons: MBIs versus active comparators (alternative interventions); MBIs versus non‐active comparators (no intervention, wait list, usual care); TM versus active comparators; TM versus non‐active comparators.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methods. Our primary outcomes were CVD clinical events (e.g. cardiovascular mortality), blood pressure, measures of psychological distress and well‐being, and adverse events. Secondary outcomes included other CVD risk factors (e.g. blood lipid levels), quality of life, and coping abilities. We used GRADE to assess the certainty of evidence.

Main results

We included 81 RCTs (6971 participants), with most studies at unclear risk of bias.

MBIs versus active comparators (29 RCTs, 2883 participants)

Systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure were reported in six trials (388 participants) where heterogeneity was considerable (SBP: MD ‐6.08 mmHg, 95% CI ‐12.79 to 0.63, I2 = 88%; DBP: MD ‐5.18 mmHg, 95% CI ‐10.65 to 0.29, I2 = 91%; both outcomes based on low‐certainty evidence). There was little or no effect of MBIs on anxiety (SMD ‐0.06 units, 95% CI ‐0.25 to 0.13; I2 = 0%; 9 trials, 438 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), or depression (SMD 0.08 units, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.24; I2 = 0%; 11 trials, 595 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). Perceived stress was reduced with MBIs (SMD ‐0.24 units, 95% CI ‐0.45 to ‐0.03; I2 = 0%; P = 0.03; 6 trials, 357 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). There was little to no effect on well‐being (SMD ‐0.18 units, 95% CI ‐0.67 to 0.32; 1 trial, 63 participants; low‐certainty evidence). There was little to no effect on smoking cessation (RR 1.45, 95% CI 0.78 to 2.68; I2 = 79%; 6 trials, 1087 participants; low‐certainty evidence). None of the trials reported CVD clinical events or adverse events.

MBIs versus non‐active comparators (38 RCTs, 2905 participants)

Clinical events were reported in one trial (110 participants), providing very low‐certainty evidence (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.37 to 2.42). SBP and DBP were reduced in nine trials (379 participants) but heterogeneity was substantial (SBP: MD ‐6.62 mmHg, 95% CI ‐13.15 to ‐0.1, I2 = 87%; DBP: MD ‐3.35 mmHg, 95% CI ‐5.86 to ‐0.85, I2 = 61%; both outcomes based on low‐certainty evidence). There was low‐certainty evidence of reductions in anxiety (SMD ‐0.78 units, 95% CI ‐1.09 to ‐0.41; I2 = 61%; 9 trials, 533 participants; low‐certainty evidence), depression (SMD ‐0.66 units, 95% CI ‐0.91 to ‐0.41; I2 = 67%; 15 trials, 912 participants; low‐certainty evidence) and perceived stress (SMD ‐0.59 units, 95% CI ‐0.89 to ‐0.29; I2 = 70%; 11 trials, 708 participants; low‐certainty evidence) but heterogeneity was substantial. Well‐being increased (SMD 0.5 units, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.91; I2 = 47%; 2 trials, 198 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). There was little to no effect on smoking cessation (RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.86 to 2.13; I2 = 0%; 2 trials, 453 participants; low‐certainty evidence). One small study (18 participants) reported two adverse events in the MBI group, which were not regarded as serious by the study investigators (RR 5.0, 95% CI 0.27 to 91.52; low‐certainty evidence).

No subgroup effects were seen for SBP, DBP, anxiety, depression, or perceived stress by primary and secondary prevention.

TM versus active comparators (8 RCTs, 830 participants)

Clinical events were reported in one trial (201 participants) based on low‐certainty evidence (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.49). SBP was reduced (MD ‐2.33 mmHg, 95% CI ‐3.99 to ‐0.68; I2 = 2%; 8 trials, 774 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), with an uncertain effect on DBP (MD ‐1.15 mmHg, 95% CI ‐2.85 to 0.55; I2 = 53%; low‐certainty evidence). There was little or no effect on anxiety (SMD 0.06 units, 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.33; I2 = 0%; 3 trials, 200 participants; low‐certainty evidence), depression (SMD ‐0.12 units, 95% CI ‐0.31 to 0.07; I2 = 0%; 5 trials, 421 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), or perceived stress (SMD 0.04 units, 95% CI ‐0.49 to 0.57; I2 = 70%; 3 trials, 194 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). None of the trials reported adverse events or smoking rates.

No subgroup effects were seen for SBP or DBP by primary and secondary prevention.

TM versus non‐active comparators (2 RCTs, 186 participants)

Two trials (139 participants) reported blood pressure, where reductions were seen in SBP (MD ‐6.34 mmHg, 95% CI ‐9.86 to ‐2.81; I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence) and DBP (MD ‐5.13 mmHg, 95% CI ‐9.07 to ‐1.19; I2 = 18%; very low‐certainty evidence). One trial (112 participants) reported anxiety and depression and found reductions in both (anxiety SMD ‐0.71 units, 95% CI ‐1.09 to ‐0.32; depression SMD ‐0.48 units, 95% CI ‐0.86 to ‐0.11; low‐certainty evidence). None of the trials reported CVD clinical events, adverse events, or smoking rates.

Authors' conclusions

Despite the large number of studies included in the review, heterogeneity was substantial for many of the outcomes, which reduced the certainty of our findings. We attempted to address this by presenting four main comparisons of MBIs or TM versus active or inactive comparators, and by subgroup analyses according to primary or secondary prevention, where there were sufficient studies. The majority of studies were small and there was unclear risk of bias for most domains. Overall, we found very little information on the effects of meditation on CVD clinical endpoints, and limited information on blood pressure and psychological outcomes, for people at risk of or with established CVD.

This is a very active area of research as shown by the large number of ongoing studies, with some having been completed at the time of writing this review. The status of all ongoing studies will be formally assessed and incorporated in further updates.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Anxiety, Anxiety/prevention & control, Anxiety Disorders, Cardiovascular Diseases, Meditation, Primary Prevention, Primary Prevention/methods, Secondary Prevention

Plain language summary

Does meditation help prevent people from developing cardiovascular disease or from worsening cardiovascular disease?

Key messages

· We looked primarily at two main types of meditation, mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) and transcendental meditation (TM), compared to receiving something else or nothing else (referred to as active and inactive comparison groups, respectively). We found inconsistent results for many of the outcomes of interest.

· Compared to inactive comparators, MBIs probably reduce stress, and may also reduce anxiety and depression and blood pressure. TM may reduce blood pressure when compared to either active or inactive comparators, with few studies reporting psychological outcomes. Results will be more certain with the addition of further well‐conducted studies.

What is cardiovascular disease?

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) includes several different diseases of the heart and blood vessels, some of which are caused by problems like high cholesterol, physical inactivity, stress, poor diet, being overweight, smoking, or drinking alcohol. Overall, CVDs are the world’s leading cause of death.

How can meditation help?

Meditation may help to reduce people’s stress levels, which could benefit them directly (for example, by lowering blood pressure), and indirectly by helping them to avoid unhealthy ways of coping with stress (for example, smoking, drinking alcohol, or making poor food choices).

What types of meditation did we look at?

We looked at two main types of meditation for this study:

· mindfulness‐based interventions (MBI);

· transcendental meditation (TM).

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out if meditation helped to:

· reduce the risk of CVD clinical events, such as death, heart attack, stroke, or chest pain;

· reduce blood pressure;

· improve stress, depression, anxiety, and well‐being;

· improve blood measures like cholesterol and blood glucose levels;

· reduce weight;

· reduce smoking;

· improve quality of life and people’s ability to cope.

What did we do? We searched for studies that looked at meditation compared with no intervention (inactive comparators) or another non‐pharmacological intervention (active comparators), in people at high risk of developing CVD and people who already had established CVD. We assessed outcomes for the totality of the participants and separately for these two groups.

We compared and summarised the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We found 81 studies that involved 6971 people either at high risk of or who already had CVD. The studies lasted between 12 weeks and five years.

Only one MBI study and one TM study reported CVD clinical events, and we found that either type of meditation may have little to no effect, but we are very uncertain about the results.

Six studies (388 people) that compared MBIs to active comparators suggest that it may have little to no effect on blood pressure, but we are uncertain about the results. Results from eight studies (774 people) found that TM probably reduces systolic blood pressure compared to active comparators, but the evidence for diastolic blood pressure was less certain.

When compared to inactive comparators, people who practised mindfulness (nine studies, 379 people) may have reductions in blood pressure, but results were inconsistent. When comparing TM to inactive comparators (2 studies, 154 people) we found that TM may reduce blood pressure.

We found that there was probably little or no difference in anxiety, depression, or well‐being between MBIs and active comparators. Six studies (357 people) reported that stress probably improved more in people who practised mindfulness. Five studies (421 people) reported little to no effect on depression among people who practised TM compared with another intervention. We are very uncertain about the effect of TM on anxiety or stress.

When compared to inactive comparators, people who practised mindfulness may have reductions in anxiety (nine studies, 533 people), depression (15 studies, 912 people), and stress (11 studies, 708 people), but results were inconsistent. Two trials (198 people) reported a probable increase in well‐being among people who practised mindfulness, compared to no intervention. We found no differences in the results for blood pressure, anxiety, depression, and stress, where we had enough studies to compare people at risk of CVD with those with established CVD.

One small study reported two unwanted/adverse effects of MBI when compared to inactive comparators. One participant had transitory vertigo during head rolling in mindful movement and in another the MBI caused resurfacing of repressed traumatic memories and depression. This participant received counselling and continued with MBI, which they found beneficial.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Even though we tried to group studies by the type of meditation intervention and by comparison groups, so they were more similar for the analyses, there was still a lot of inconsistency in the findings that remains unexplained.

Most of the studies were small in size, and we are uncertain as to how well they were carried out, mainly due to poor reporting.

The search cut‐off date of November 2021 is a limitation of the review. However, in May 2023 we revisited the status of the 74 ongoing studies and provided details of these. Nine studies were found to have been completed in this time and will be formally assessed in an update of this review.

How up‐to‐date is this evidence?

The evidence is up‐to‐date to November 2021.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) compared to active comparators for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

| Mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) compared to active comparators for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: people at high risk of or withcardiovascular disease Setting: community Intervention: MBIs Comparison: active comparators | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with active comparators | Risk with MBIs | |||||

| Clinical CVD events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), change from baseline Follow‐up (range): 3 to 18 months |

The mean systolic blood pressure change from baseline ranged from ‐7.0 to 0.2 mmHg | MD 6.08 lower (12.79 lower to 0.63 higher) | ‐ | 388 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | Three small trials reported large beneficial effects of the MBIs compared to active comparators, whereas the remaining three with larger sample size showed little or no effect of the intervention. |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), change from baseline Follow‐up (range): 3 to 18 months |

The mean diastolic blood pressure change from baseline ranged from ‐3.4 to 3.2 mmHg | MD 5.18 lower (10.65 lower to 0.29 higher) | ‐ | 388 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,c | Three small trials reported large beneficial effects of the MBIs compared to active comparators, whereas the remaining three with larger sample size showed little or no effect of the intervention. |

| Anxiety, change from baseline Follow‐up (range): 3 to 9 months |

SMD 0.06 lower (0.25 lower to 0.13 higher) | ‐ | 438 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEd | We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Depression, change from baseline Follow‐up (range): 3 to 9 months |

SMD 0.08 higher (0.08 lower to 0.24 higher) | ‐ | 595 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEd | We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Perceived stress, change from baseline Follow‐up (range): 4 to 7 months |

SMD 0.24 lower (0.45 lower to 0.03 lower) | ‐ | 357 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEe | We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Well‐being Follow‐up: 9 months |

SMD 0.18 lower (0.67 lower to 0.32 higher) | ‐ | 63 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWf | We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| Smoking cessation Follow‐up (mean): 6 months |

Study population 151 per 1000 |

218 per 1000 (117 to 403) | RR 1.45 (0.78 to 2.68) | 1087 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWg,h | Two studies showed large beneficial effects of the MBI, and the remaining four showed little or no effect of MBIs on smoking cessation. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CVD: cardiovascular disease; MBI: mindfulness‐based intervention; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: one study was at high risk of attrition bias and all other studies were at unclear risk for this domain; one study was at high risk of selection bias and three were at unclear risk for this domain. bDowngraded by one level for inconsistency: I2 = 88%. cDowngraded by one level for inconsistency: I2 = 91%. dDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: all but two studies at unclear or high risk of attrition bias. eDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: one study was at high risk of attrition bias and three other studies were at unclear risk for this domain; one study was at unclear risk of selection bias. fDowngraded by two levels for imprecision: very small sample size and the CI includes both appreciable benefit and harm. gDowngraded by one level for inconsistency: I2 = 79%. hDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: all but three studies at unclear or high risk of attrition bias and two studies at unclear risk of selection bias.

Summary of findings 2. Mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) compared to non‐active comparators for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

| Mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) compared to non‐active comparators for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: people at high risk of or withcardiovascular disease Setting: community Intervention: MBIs Comparison: non‐active comparators | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐active comparators | Risk with MBIs | |||||

| Clinical CVD events (CVD mortality and non‐fatal MI) Follow‐up: 36 months |

Study population | RR 0.94 (0.37 to 2.42) | 110 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWa,b | ‐ | |

| 140 per 1000 | 132 per 1000 (52 to 340) | |||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), change from baseline Follow‐up (range): 3 to 9 months |

The mean systolic blood pressure change from baseline ranged from ‐9.7 to 9.47 mmHg | MD 6.62 lower (13.15 lower to 0.1 lower) | ‐ | 379 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWc,d | Three trials reported beneficial effects of the MBIs compared to non‐active comparators, whereas the remaining six showed little or no effect of the intervention. |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), change from baseline Follow‐up (range): 3 to 9 months |

The mean diastolic blood pressure change from baseline ranged from ‐7.7 to 4.1 mmHg | MD 3.35 lower (5.86 lower to 0.85 lower) | ‐ | 379 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWc,e | Three trials reported beneficial effects of the MBIs compared to non‐active comparators, whereas the remaining six showed little or no effect of the intervention. |

| Anxiety, change from baseline Follow‐up (range): 3 to 9 months |

SMD 0.78 lower (1.09 lower to 0.47 lower) | ‐ | 533 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWf,g | Six trials reported beneficial effects of the MBIs compared to non‐active comparators, whereas the remaining three showed little or no effect of the intervention. We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Depression, change from baseline Follow‐up (range): 3 to 12 months |

SMD 0.66 lower (0.91 lower to 0.41 lower) | ‐ | 912 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWh,i | Eleven trials reported beneficial effects of the MBIs compared to non‐active comparators, whereas the remaining four showed little or no effect of the intervention. We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Perceived stress, change from baseline Follow‐up (range): 3 to 12 months |

SMD 0.59 lower (0.89 lower to 0.29 lower) | ‐ | 708 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWj,k | Six trials reported beneficial effects of the MBIs compared to non‐active comparators, one reported beneficial effects of the non‐active comparator, and the remaining four showed little or no effect of the intervention. We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Well‐being Follow‐up (range): 5 to 9 months |

SMD 0.5 higher (0.09 higher to 0.91 higher) | ‐ | 198 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEl | We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Adverse events | There were 2/9 participants with an adverse event in the MBI group and 0/9 in the control group. | RR 5.0 (0.27 to 91.52) | 18 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWm | Calculation of anticipated absolute effects is not possible due to 0 events in the control arm. Adverse events reported were not serious. | |

| Smoking cessation Follow‐up (mean): 6 months |

Study population | RR 1.36 (0.86 to 2.13) | 453 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWn,o | ‐ | |

| 129 per 1000 | 175 per 1000 (111 to 274) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CVD: cardiovascular disease; MBI: mindfulness‐based intervention; MD: mean difference; MI: myocardial infarction; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: the study is at unclear risk in all domains. bDowngraded by two levels for imprecision: very small sample size, and CI wide enough to include the possibility of no benefit, no difference, and a large benefit. cDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: all but two studies at unclear or high risk of attrition bias. dDowngraded by one level for inconsistency: I2 = 87%. eDowngraded by one level for inconsistency: I2 = 61%. fDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: four studies at unclear or high risk of attrition bias and one study each at high risk or unclear risk of selection bias. gDowngraded by one level for inconsistency: I2 = 61%. hDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: the majority of studies at unclear or high risk of attrition bias and four studies at unclear risk of selection bias. iDowngraded by one level for inconsistency: I2 = 67%. jDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: four studies at unclear risk and one at high risk of attrition bias. kDowngraded by one level for inconsistency: I2 = 70%. lDowngraded by one level for imprecision: small sample size. mDowngraded by two levels for imprecision: very small sample size and CI includes the possibility of no difference as well as harm. nDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: one study at high risk of attrition bias.

Summary of findings 3. Transcendental meditation (TM) compared to active comparators for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

| Transcendental meditation (TM) compared to active comparators for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: people at high risk of or with cardiovascular disease Setting: community Intervention: TM Comparison: active comparators | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with active comparators | Risk with TM | |||||

| Clinical CVD events (CVD mortality, non‐fatal MI and stroke, revascularisations) Follow‐up: 5.4 years |

Study population | RR 0.91 (0.56 to 1.49) | 201 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa | ‐ | |

| 255 per 1000 | 232 per 1000 (143 to 380) | |||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), change from baseline Follow‐up (median): 9 months; (range): 3 months to 5.4 years |

The mean systolic blood pressure change from baseline ranged from ‐7.49 to 4.88 mmHg | MD 2.33 mmHg lower (3.99 lower to 0.68 lower) | ‐ | 774 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEb | ‐ |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), change from baseline Follow‐up (median): 9 months; (range): 3 months to 5.4 years |

The mean diastolic blood pressure change from baseline ranged from ‐6.6 to 0.3 mmHg | MD 1.15 mmHg lower (2.85 lower to 0.55 higher) | ‐ | 774 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,c | Beneficial effects of TM on diastolic blood pressure were seen in one trial, possible benefits of TM in two, possible benefits of the active comparator in two, and little or no effect of TM in the remaining three trials. |

| Anxiety, change from baseline Follow‐up (range): 4 to 9 months |

SMD 0.06 higher (0.22 lower to 0.33 higher) |

‐ | 200 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWd,e | We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Depression, change from baseline Follow‐up (median): 7 months; (range): 4 months to 5.4 years |

SMD 0.12 lower (0.31 lower to 0.07 higher) | ‐ | 421 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEf | We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Perceived stress, change from baseline Follow‐up (range): 6 to 7 months |

SMD 0.04 higher (0.49 lower to 0.57 higher) | ‐ | 194 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOWd,g,h | One study favoured the active comparator and the remaining two showed little or no effect of TM on depression. We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Well‐being | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| Adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| Smoking cessation | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CVD: cardiovascular disease; MD: mean difference; MI: myocardial infarction; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; TM: transcendental meditation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by two levels for imprecision: CI includes the possibility of a negative effect, no effect, or a positive effect; small sample size. bDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: six studies were at unclear risk of attrition bias and one study was at high risk of attrition bias; one study was at unclear risk of selection bias. cDowngraded by one level for inconsistency: I2 = 53%. dDowngraded by one level for imprecision: small sample size. eDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: one study at unclear risk of selection bias. fDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: three studies were at unclear risk and one study at high risk of attrition bias, and one study at unclear risk of selection bias. gDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: two studies were at unclear risk of attrition bias. hDowngraded by one level for inconsistency: I2 = 70%.

Summary of findings 4. Transcendental meditation (TM) compared to non‐active comparators for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

| Transcendental meditation (TM) compared to non‐active comparators for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: people at high risk of or withcardiovascular disease Setting: community Intervention: TM Comparison: non‐active comparators | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with non‐active comparators | Risk with TM | |||||

| Clinical CVD events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), change from baseline Follow‐up: mean 3 months | The mean systolic blood pressure change from baseline ranged from 1.3 to 1.85 mmHg | MD 6.34 mmHg lower (9.86 lower to 2.81 lower) | ‐ | 139 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ‐ |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), change from baseline Follow‐up: mean 3 months | The mean diastolic blood pressure change from baseline ranged from 1.2 to 2.26 mmHg | MD 5.13 mmHg lower (9.07 lower to 1.19 lower) | ‐ | 139 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWa,b | ‐ |

| Anxiety, change from baseline Follow‐up: 3 months | SMD 0.71 lower (1.09 lower to 0.32 lower) | ‐ | 112 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,c | We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Depression, change from baseline Follow‐up: 3 months | SMD 0.48 lower (0.86 lower to 0.11 lower) | ‐ | 112 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,c | We interpret an SMD of 0.2 to represent a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect. | |

| Perceived stress | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| Well‐being | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| Adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| Smoking cessation | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CVD: cardiovascular disease; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; TM: transcendental meditation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: one study at high risk of attrition bias and one study at unclear risk of selection bias. bDowngraded by one level for imprecision: small sample size. cDowngraded by one level for risk of bias: study at high risk of attrition bias.

Background

Description of the condition

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are a group of disorders of the heart and blood vessels, which include CVDs due to atherosclerosis (coronary heart disease (CHD), cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease) and other CVDs (rheumatic heart disease, congenital heart disease, cardiomyopathies, and cardiac arrhythmias). Atherosclerosis is a complex process that occurs in the walls of blood vessels over many years, where fatty material and cholesterol deposit and form plaques, which narrow and stiffen arteries and reduce blood flow. Ruptured plaques can cause the formation of blood clots, which trigger heart attacks if they develop in the coronary arteries and strokes if clots develop in the brain (WHO 2011).

CVDs are the world's leading cause of death and caused 17.9 million deaths in 2019; this represented 32% of all global deaths that year, over three‐quarters of which occurred in low‐ and middle‐income countries (WHO 2021). Of these 17.9 million deaths, 85% were due to heart attack and stroke (WHO 2021).

Many CVDs are preventable by addressing behavioural cardiovascular risk factors, the most important of which are unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, tobacco use, and harmful use of alcohol, which in turn can affect markers of increased CVD risk such as raised blood pressure, raised blood glucose, raised blood lipids, and overweight and obesity (WHO 2021). Population‐wide strategies to address these behavioural risk factors and health policies to create environments where healthy options are available and affordable are recommended (WHO 2021). Other determinants of atherosclerotic CVD include advancing age, hereditary factors, gender, poverty, and psychological factors including stress and depression (WHO 2011). Psychosocial stress has been shown to be a risk factor for CVD (Dimsdale 2008; Merz 2002; O’Donnell 2010; Rosengren 2004; Yusuf 2004), and clusters with other behavioural risk factors such as smoking and increased consumption of alcohol and unhealthy foods. As many of these risk factors are related to lifestyle choices and are modifiable, they have become the focus of CVD prevention strategies. It is estimated that as much as 90% of the population‐attributable risk for CHD (specifically myocardial infarction) and stroke worldwide is accounted for by contributions from nine modifiable risk factors: abnormal cholesterol, raised blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, smoking, excessive alcohol intake, unhealthy diet, psychosocial stress, abdominal obesity, and lack of physical activity (O’Donnell 2010; Yusuf 2004).

CHD, high blood pressure, and diabetes mellitus are also major risk factors for heart failure. Heart failure occurs when there is insufficient oxygen to meet the metabolic demands of the body, resulting from a reduced ability of the heart to pump or fill with blood, or both (DHDSP 2016; Fox 2001). Heart failure is a growing public health burden, where it is estimated that over 26 million people worldwide are affected, and the prevalence is increasing (Savarese 2017). Mortality and morbidity associated with heart failure are high even with advances in treatment and prevention, and quality of life is poor (Savarese 2017). Reducing cardiovascular risk thus also impacts the numbers affected by heart failure.

Description of the intervention

Interventions incorporating meditation to address stress, anxiety, and depression, and self‐management of chronic conditions, are becoming popular for many health complaints and to enhance well‐being, yet the benefits of meditation were understood thousands of years ago. Meditation is a contemplative practice that originates from the world's wisdom traditions, but interventions are now commonly delivered in a secular context. There are many types of meditation practice, but the most researched interventions are mindfulness‐based interventions (MBIs) and transcendental meditation (TM).

MBIs in health care originate from the work of Jon Kabat Zinn in the late 1970s and the development of his eight‐week programme of mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR) (Kabat‐Zinn 1990). This programme has been evaluated for a number of conditions, for example chronic pain (Kabat‐Zinn 1986) and anxiety (Kabat‐Zinn 1992). MBSR has been informed by Buddhist teachings but is taught in a secular context. MBSR has also informed another well‐researched intervention, mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy (MBCT), developed by Segal 2013 for the treatment of depression. Mindfulness is most commonly defined as "paying attention, in a particular way, on purpose, in the present moment and non‐judgementally" (Kabat‐Zinn 1994). Mindfulness has also been described by a UK Mindfulness All Party Parliamentary Group in the following way: “Mindfulness is best considered an inherent human capacity akin to language acquisition; a capacity that enables people to focus on what they experience in the moment, inside themselves as well as in their environment, with an attitude of openness, curiosity and care” and has been defined as "live in the moment, notice what is happening and make choices in how you respond to your experience rather than being driven by habitual reactions" (Breathworks 2019). Simply, it means being aware of our experience moment to moment, and with this awareness comes choice. Other key aspects of many MBIs are compassion practices for self and others, and in this respect mindfulness has also been described as heartfulness: it is as much of the heart as it is of the mind (Kabat‐Zinn 1994; Williams 2007). Mindfulness courses are typically eight weeks long, delivered by trained teachers from their own mindfulness practice, and cover a series of formal meditation practices including body scanning, mindfulness of breathing, compassion practices, and informal practices of mindfulness of daily living, including mindful movement (Burch 2013; Hennessey 2016; Kabat‐Zinn 1990; Segal 2013). The essential components of MBIs, including teachers' training and characteristics, have been reviewed (Crane 2017). The expectation of participants is home practice daily, starting at a minimum of 10 minutes twice a day, which increases over the course of eight‐week programmes, with continued practice thereafter.

TM is described as a technique for inner peace and wellness, an effortless practice that enables the mind and body to access a special quality of rest (Transcendental Meditation® 2018). Transcending means to go beyond the steps of the meditation practice itself to an inner stillness. The technique is delivered by certified teachers, trained in the techniques of the founder Maharishi Mahesh. It is based on ancient Vedic teachings from India, which were popularised and brought to the west by Maharishi Mahesh in the late 1950s. Practitioners receive a personal mantra to repeat silently to settle the mind inward; this is practised for 15 or 20 minutes twice a day. Training in TM takes four days, personal instruction on day one and small group sessions days two to four to consolidate the practice. TM distinguishes itself from other forms of meditation that train the mind in some way, for example, in the case of mindfulness, to be in the present moment. TM liberates rather than trains the mind, allowing it to settle effortlessly into a silence more profound than the present moment (Meditation Trust). There is a considerable volume of research on the potential benefits of TM and its standardised format has allowed comparisons between studies. A meta‐analysis, for example, found beneficial effects of TM for trait anxiety compared to alternative treatments and care as usual, with larger effect sizes for those with higher levels of anxiety at baseline (Orme‐Johnson 2014).

How the intervention might work

There is extensive evidence to show a link between psychosocial stress and CVD. Whilst psychosocial stress clusters with other behavioural risk factors for CVD, independent associations are seen for perceived stress (Richardson 2012), stress at work (general work stress (Rosengren 2004), specifically job strain (Kuper 2003), and an imbalance between effort and reward (Dragano 2017)), stress at home, financial stress, stressful life events, and depression (Rosengren 2004). Rosengren 2004 was a case control study conducted over 52 countries, which found that these differences were consistent across different regions, in different ethnic groups, and in both men and women. It is clear that stress is a trigger for CVD, but less clear are the mechanisms by which this operates and these may be complex and multifactorial (Dimsdale 2008; Merz 2002; Rozanski 1999; Vale 2005).

There is evidence from systematic reviews to show that MBIs are effective at reducing stress, anxiety, and depression (Fjorback 2011; Janssen 2018; Khoury 2013; Khoury 2015), with modest results for studies employing active control groups (Goyal 2014). There is also a developing body of research demonstrating that MBIs could have beneficial effects on other CVD risk factors (Fulwiler 2015). For example, mindfulness training has been used for smoking cessation (Brewer 2011), weight loss (Fulwiler 2015), and to reduce blood pressure (Blom 2014). The possible mechanisms by which MBIs could influence cardiovascular risk include attention control, emotional regulation, and self‐awareness (Fulwiler 2015). Few studies have been conducted in patients with established CVD. The effects of MBSR and MBCT have been examined in a systematic review of patients with vascular disease including hypertension, heart disease, and stroke. Some improvements were seen in psychological outcomes in vascular disease patients, but the effects on physical outcomes were mixed (Abbott 2014). Another review of MBIs in patients following transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or stroke found very few studies and could draw no firm conclusions (Lawrence 2013).

Similarly, there is evidence of beneficial effects of TM on psychological distress (Orme‐Johnson 2014), but positive effects are less apparent in studies using active control groups (Goyal 2014). There are a large number of studies looking at the effects of TM on blood pressure. Overall beneficial effects have been seen in systematic reviews (e.g. Anderson 2008), but positive effects of TM on blood pressure have been attributed to important methodological weaknesses and bias (Canter 2004). An overview of eight systematic reviews and meta‐analyses finds a clear trend of increasing evidence to support reductions in blood pressure with TM but cautions that there are some conflicting findings and potential risk of bias in many of the included RCTs (Ooi 2017). The effects of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) and non‐ABPM have been examined in response to both TM and other forms of meditation (non‐TM) where both interventions showed reductions in blood pressure and smaller effect sizes with ABPM (Shi 2017). Components of the metabolic syndrome, including blood pressure, have been examined in a trial of TM compared to health education as an active control in patients with stable CHD. TM was found to lead to beneficial changes in systolic blood pressure, insulin resistance, and heart rate variability compared to health education (Paul‐Labrador 2006). A trial with long‐term follow‐up has shown reduced clinical events (composite of total mortality, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, and stroke) and improvements in psychological outcomes compared to health education in Black patients with CHD (subjects were identified from the African American Heart Health Registry) (Schneider 2012).

Two recent Cochrane reviews have examined a range of psychological interventions for CHD (Richards 2017) and for diabetes distress in adults with type 2 diabetes (Chew 2017). Richards 2017 looked at psychological interventions compared to usual care, delivered by trained staff and with a minimum follow‐up of six months. Only two of the 35 included studies examined meditation. Chew 2017 looked at a range of psychological interventions, and none of these focused on meditation (Chew 2017). Two further systematic reviews have looked at mixed mind‐body interventions for cardiac disease, including meditation. Younge 2015 found promising results in quality of life measures, psychological measures, and blood pressure but reported overall low‐quality studies. Similarly, in heart failure patients, small to moderate effects were seen in quality of life, exercise capacity, anxiety, depression, blood pressure, and heart rate variability (Gok Metin 2018). Anxiety and depression often co‐exist with long‐term conditions such as CVD, type 2 diabetes, and heart failure. Meditation could be effective in addressing these co‐morbidities, as well as potentially affecting risk factors for CVD.

Why it is important to do this review

The 2017 scientific statement from the American Heart Association (AHA) highlights the potential benefits of meditation on CVD risk factors including psychosocial stress, blood pressure, smoking, insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome, subclinical atherosclerosis, endothelial function, exercise capacity, and the primary and secondary prevention of CVD (AHA 2017). Their findings suggest possible benefits of meditation, although the overall quality and sometimes quantity of studies is poor. Research recommendations include use of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), blinded outcome assessment, adequate power of studies, longer and more complete follow‐up, and studies performed by investigators without financial or intellectual bias (AHA 2017). This Cochrane review will update these findings and will focus on evidence from RCTs and assess risk of bias and overall quality of contributing research. This is a rapidly expanding field and it is important to synthesise the evidence of these potentially useful interventions in a format that can be updated to further inform guideline development and end‐user choice.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of meditation techniques, primarily MBIs and TM, for the primary and secondary prevention of CVD in adults at high risk and with established CVD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included parallel‐arm and cluster‐RCTs. We also included cross‐over RCTs but analysed only the first phase as a parallel‐group design. We did not include quasi‐RCTs. We included studies reported as full‐text, those published as abstract only, and unpublished data.

Types of participants

We included adults (defined as ≥ 18 years of age) both at high risk of, and with established CVD, to examine both primary and secondary prevention.

Primary prevention

Adults identified as being at increased risk of CVD exhibiting one or more of the following risk factors as defined by the trial authors: hypertension, abnormal cholesterol levels, overweight/obesity, smoking, impaired glucose control/type 2 diabetes.

Secondary prevention

Adults diagnosed with CVD as defined by the trial authors, including the following: experienced a myocardial infarction (MI); undergone a revascularisation procedure (coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)); people with angina; people with angiographically defined CHD, cerebrovascular disease including stroke and TIA, or peripheral vascular disease (PVD). We also included patients with heart failure that has developed as a consequence of CVD where these can be identified from other forms of heart failure, or form the majority in mixed populations.

For studies involving only a subset of relevant participants, we included only studies where participants of interest formed the majority of the sample if stratified data were not reported separately.

We explored the effects of primary and secondary prevention on outcomes in subgroup analyses (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Types of interventions

We included trials of meditation interventions, predominantly MBIs and TM using methods/elements as illustrated previously (see Description of the intervention), or as defined/described by study investigators. We also included other types of meditation where the methods were adequately described. Multifactorial interventions were only included where meditation was the main focus. We excluded interventions that comprised predominantly physical practices as well as meditation such as yoga, tai chi, and qigong to avoid the confounding effects of physical activity on CVD outcomes. We included trials with any comparison group, for example no intervention/wait list, usual care (inactive comparators), or attention control, or alternative interventions (active comparators). Trials where the comparison was another form of meditation or different levels of intensity of the intervention of interest were excluded. We excluded trials where meditation was delivered alongside co‐interventions unless the comparison group also received the co‐intervention, so the effects of meditation alone could be determined.

We included studies with follow‐up periods of 12 weeks or more, defined as the intervention period plus post‐intervention follow‐up.

We did not combine different meditation interventions and comparators in the main analysis as this would make interpretation of the results difficult due to heterogeneity. Instead, we undertook four main analyses:

MBIs versus active comparators;

MBIs versus non‐active comparators;

TM versus active comparators;

TM versus non‐active comparators.

Other meditation interventions that met the inclusion criteria but did not fit the above categories were described narratively.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

CVD clinical events:

cardiovascular mortality;

myocardial infarction;

coronary artery bypass graft (CABG);

percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI);

angina;

angiographically defined coronary heart disease (CHD);

stroke;

transient ischaemic attack (TIA);

peripheral vascular disease (PVD);

-

Blood pressure:

systolic blood pressure;

diastolic blood pressure.

Validated measures of psychological distress (e.g. Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck 1988) and Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1996), Centre for Epidemiological Studies ‐ Depression Scale (CES‐D; Radloff 1977), Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9; Spitzer 1999), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond 1983), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD‐7; Spitzer 2006)) and well‐being (e.g. the Warwick‐Edinburgh Mental Well‐being Scale (WEMWBS; Tennant 2007)).

Adverse events (number of patients affected).

Secondary outcomes

-

Individual CVD risk factors other than blood pressure including:

lipid levels (total cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) and high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, measured separately);

glycaemic control (measures such as fasting blood glucose and HbA1c, and the incidence of type 2 diabetes);

body weight or body mass index (BMI), or both;

smoking rates.

Validated measures of quality of life (QoL) (e.g. 36‐item short‐form health survey (SF‐36; Ware 1992)), any validated QoL scale, generic or disease‐specific.

Validated measures of coping, resilience, mastery (e.g. the Self‐Efficacy Scale (Sherer 1982) and the Self‐Management Screening (SeMaS) tool (Eikelenboom 2015)).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials through systematic searches of the following bibliographic databases on 14 November 2021:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2021, Issue 11) (Cochrane Library).

Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, MEDLINE Daily and MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 12 November 2021).

Embase (Ovid, 1980 to week 45, 2021).

PsycINFO (Ovid, 1806 to November week 1, 2021).

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (EBSCO, 1937 to 14 October 2021).

AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database) (Ovid, 1985 to November 2021).

The RCT filter for MEDLINE is the Cochrane sensitivity‐maximising RCT filter, and for Embase, terms as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions have been applied (Lefebvre 2019). For the other databases, except CENTRAL, an adaptation of the Cochrane RCT filter has been applied. Search strategies for all databases are presented in Appendix 1.

We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov and WHO ICTRP on 15 November 2021 for ongoing or unpublished trials.

We searched all databases from their inception to the present, and we imposed no restriction on language of publication or publication status.

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of interventions. We considered adverse effects described in the included studies only.

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of included studies and any relevant systematic reviews identified for additional references to trials. We also examined any relevant retraction statements and errata for included studies. We contacted authors for missing information and details of ongoing trials where necessary.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (of KR, AT, RC) independently screened titles and abstracts of all the potential studies identified as a result of the search and coded them as either 'retrieve' (eligible or potentially eligible/unclear) or 'do not retrieve'. We resolved any disagreements through discussion. We retrieved the full‐text study reports/publication and two review authors (of KR, AT, RC, LK) independently screened the full text and identified studies for inclusion, and identified and recorded reasons for exclusion of the ineligible studies. We resolved any disagreements through discussion. We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, is the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram and 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Data extraction and management

We used a data collection form for study characteristics and outcome data, which we piloted. Two review authors (of KR, AT, RC, LK, LH) extracted study characteristics from included studies. We extracted the following study characteristics:

Methods: study design, total duration of study, number of study centres and location, study setting, and date of study.

Participants: N randomised, N lost to follow‐up/withdrawn, N analysed, mean age, age range, gender, primary or secondary prevention (at increased risk of CVD, or established CVD), inclusion criteria, and exclusion criteria.

Interventions: intervention, comparison, concomitant treatments/medications.

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, and time points reported.

Notes: funding for trial, and notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

Two review authors (of KR, AT, RC, LK, LH) independently extracted outcome data from included studies. We resolved disagreements by consensus. One review author (KR) transferred data into the Review Manager 5 file (RevMan 2020). We double‐checked that data were entered correctly by comparing the data presented in the systematic review with the data extraction form. A second review author (AT) spot‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the trial report.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (of KR, AT, RC, LK, LH) independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). We resolved any disagreements by discussion. We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias.

We assessed each potential source of bias as either high, low, or unclear and provided a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the risk of bias table. We summarised the risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed. We expected blinding of participants and personnel to be difficult to achieve and unlikely for trials of meditation interventions, and so we have not recorded this as high risk but as unclear. Where information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with a trial author, we noted this in the risk of bias table.

Where we found cluster‐randomised trials that met the inclusion criteria, we followed the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017), and explored the following: recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters, incorrect analysis, and comparability with individually randomised trials.

When considering treatment effects, we took into account the risk of bias for the studies that contribute to that outcome.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review according to the published protocol (Rees 2019a), and report any deviations from it in the Differences between protocol and review section of the systematic review.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed dichotomous data (e.g. CVD clinical events, smoking rates) as risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous variables (e.g. blood pressure, lipid levels, glycaemic control, weight), we compared net changes (i.e. intervention group minus control group differences) and calculated mean differences (MD) and 95% CIs for each study. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) where different scales have been used to measure the same outcome, e.g. psychological distress, well‐being, quality of life, and tested the robustness of using this and MD using sensitivity analyses. We interpreted the SMD in accordance with Cohen's 'rule of thumb' described in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions as follows: an SMD of 0.2 represents a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect (Schünemann 2022). We planned to, where possible, calculate the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial or harmful outcome (NNTB or NNTH) to aid the interpretation of findings. We entered data presented as a scale with a consistent direction of effect and labelled these clearly.

We narratively described skewed data reported as medians and interquartile ranges.

Unit of analysis issues

Where cluster‐randomised trials met the inclusion criteria of the review, we analysed these in accordance with guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022). For trials with multiple arms, we divided the control group N by the number of intervention arms to avoid double‐counting in meta‐analyses. We analysed outcomes at the longest period of follow‐up where multiple measurements had been taken, unless there was significant (> 30%) attrition. We planned to explore the effects of short‐term (12 to 26 weeks) and longer‐term (greater than 26 to 52 weeks, greater than 52 weeks) follow‐up in subgroup analyses if there were sufficient data.

Dealing with missing data

We planned to contact investigators or study sponsors in order to verify key study characteristics and obtain missing numerical outcome data where necessary (e.g. when a study is identified as abstract only). Where standard deviations (SD) for outcomes were not reported, other variance measures, such as standard errors and CIs, were unavailable to derive SDs from, and we were unable to obtain information from study authors, we imputed these following the methods presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2021). Where studies did not report results as change from baseline for continuous outcomes, we calculated this and the SD differences following the methods presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for imputing these (Higgins 2021), and assumed a correlation of 0.5 between baseline and follow‐up measures, as suggested by Follman 1992.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (50% to 90%; Deeks 2022), we reported it and explored possible causes by pre‐specified subgroup analysis (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). If we were unable to conduct subgroup analyses to explore this or where heterogeneity remained unexplained, we presented individual studies in forest plots to show the direction of effect of individual studies but described narratively our uncertainty around pooled effect estimates.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we were able to pool more than 10 trials, we created and examined a funnel plot to explore possible small study biases for the primary outcomes (Primary outcomes).

Data synthesis

We undertook meta‐analyses only where this was meaningful, i.e. if the treatments, participants, and the underlying clinical question were similar enough for pooling to make sense.

We used a random‐effects model as we cannot assume that all studies in the meta‐analyses are estimating the same intervention effect, but rather are estimating intervention effects that follow a distribution across studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed the following subgroup analysis for two comparisons: MBIs versus non‐active comparators and TM versus active comparators.

By types of subpopulation: primary prevention (those at high risk of CVD) and secondary prevention (those with established CVD).

We assessed the following outcomes in subgroup analysis.

Blood pressure.

Validated measures of psychological distress and well‐being.

We used the formal test for subgroup interactions in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2020).

Where there are sufficient studies in future updates, we will explore heterogeneity for the subgroups below for all comparisons:

Nature and intensity of the meditation intervention.

Nature and intensity of the comparator.

Length of follow‐up (12 to 26 weeks, greater than 26 to 52 weeks, and greater than 52 weeks).

Setting of the intervention (e.g. group, individual, online, community, inpatient).

Sensitivity analysis

At the protocol stage, we planned to carry out the following sensitivity analyses.

Only including studies with a low risk of bias. We defined this as: low risk in at least four domains, but not including blinding of participants and personnel, which is difficult and therefore unlikely in the trials of interest. For most outcomes of interest, important domains are adequate randomisation and concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, attrition, and selective reporting.

Only including studies where there are no conflicts of interest, e.g. funding source of trials.

Restricting the analyses to published peer‐reviewed trials.

Testing the robustness of using SMD or MD where appropriate.

Testing the robustness of the results by repeating the analyses using different statistical models (fixed‐effect and random‐effects models).

Note that we only reported these where there were sufficient studies to do so. We did not perform the sensitivity analyses including studies at low risk of bias, as risk of bias was rated as unclear for most domains for the majority of studies. Similarly, few conflicts of interest were reported, and all but one trial was published in a peer‐reviewed journal.

Where we pooled data and found possible effects of the interventions, we tested the robustness of these by exploring differences between random‐effects and fixed‐effect models and using MD instead of SMD where appropriate.

Reaching conclusions

We based our conclusions only on findings from the quantitative and narrative synthesis of included studies for this review. We avoided making recommendations for practice and our implications for research suggest priorities for future research and outline what the remaining uncertainties are in the area.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created summary of findings tables using the following outcomes:

CVD clinical events (cardiovascular mortality and non‐fatal endpoints reported separately and described in a narrative synthesis);

systolic and diastolic blood pressure;

validated measures of psychological distress (anxiety, depression, perceived stress) and well‐being;

adverse events;

smoking rates.

We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of a body of evidence as it relates to the studies that contribute data to the meta‐analyses for the prespecified outcomes. We used methods and recommendations described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2021), and used GRADEpro software (GRADEPro GDT 2015). We created a separate summary of findings table for each comparison (MBI versus active control, MBI versus non‐active control, TM versus active control, TM versus non‐active control). We justified all decisions to downgrade the certainty of the evidence using footnotes and made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review where necessary.

Two review authors (KR, AT) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence. We resolved any disagreements through discussion. Judgements were justified, documented, and incorporated into the reporting of results for each outcome.

We extracted study data, formatted our comparisons in data tables, and prepared a summary of findings table before writing the results and conclusions of our review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Searching medical databases and clinical trial registries to November 2021 and other sources, we identified 6993 references, which reduced to 4019 after de‐duplication. Of the 4019 references screened, 644 went forward for formal full‐text assessment based on our pre‐defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Following full‐text assessment and collation of multiple papers for individual studies, 81 studies (156 references) were included. We also identified 74 ongoing trials and categorised 14 studies as awaiting classification due to insufficient information.

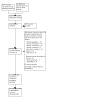

In May 2023, we revisited the status of the 74 ongoing studies. Of these, nine studies that were ongoing back in November 2021 were re‐categorised as awaiting classification because results had become available (Table 5). This brings us to a total of 23 studies awaiting classification (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification) and 65 ongoing studies (Characteristics of ongoing studies). The flow of study selection is presented in the PRISMA diagram in Figure 1.

1. Status updates of ongoing studies identified in November 2021.

| Study ID and citation details | Status updates as of May 2023 |

|

ACTRN12618000844246 ImpleMENTing meditatiOn into heart disease clinical settings (The MENTOR Study). https://anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?ACTRN=12618000844246 (first received 18 May 2018). |

Status still recruiting, registry last updated 5 June 2019. |

|

ACTRN12618001247268 Compassion Focused Therapy as a Treatment for Body Weight Shame Associated with Obesity. https://anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?ACTRN=12618001247268 (first received 24 July 2018). |

Status still recruiting, registry last updated 13 December 2019. |

|

ACTRN12620000105943 Support After Stroke with group‐based classeS: The SASS study. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=ACTRN12620000105943 (first received 5 February 2020). |

Status still recruiting, registry last updated 21 November 2022. |

|

ACTRN12621000445875 Investigating the effect of cognitive, behavioural and mindfulness‐based interventions on smoking rates in lower socio‐economic groups. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=ACTRN12621000445875 (first received 19 April 2021). |

Status recruiting, registry last updated 19 September 2022. |

|

ACTRN12621000580875 Self‐compassion for weight management: an online intervention for adults seeking to manage weight. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=ACTRN12621000580875 (first received 17 May 2021). |

Status completed, no results, registry last updated 24 January 2022. |

Asfar 2021

|

Status recruiting, registry last updated 27 October 2022. |

|

Chandra 2020 Chandra M, Raveendranathan D, Pradeep RJ, Patra S, Rushi, Prasad K, et al. Managing Depression in Diabetes Mellitus: A Multicentric Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Effectiveness of Fluoxetine and Mindfulness in Primary Care: Protocol for DIAbetes Mellitus ANd Depression (DIAMAND) Study. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 2020;42(6 Suppl):S31‐S38. [DOI: 10.1177/0253717620971200] |

Cannot access registry to check status but described as ongoing in a cross‐sectional analysis of baseline data published in 2023 (Patra, Suravi; Patro, Binod Kumar1; Padhy, Susanta Kumar; Mantri, Jogamaya. Relationship of Mindfulness with Depression, Self‐Management, and Quality of Life in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Mindfulness is a Predictor of Quality of Life. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry 39(1):p 70‐76, Jan–Mar 2023. | DOI: 10.4103/ijsp.ijsp_436_20) |

Chung 2019

|

Status recruiting, registry last updated 7 July2020. Protocol published in full in 2022. |

|

DRKS00021412 Self‐Compassion, Eating Behavior & Dieting Success. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=DRKS00021412 (first received 15 April 2020). |

Status recruitment suspended, registry last updated on 14 November 2022. |

|

Forman 2021 Forman EM, Chwyl C, Berry MP, Taylor LC, Butryn ML, Coffman DL, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of mindfulness and acceptance‐based treatment components for weight loss: Protocol for a multiphase optimization strategy trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials 2021;110:106573. [DOI: 10.1016/j.cct.2021.106573] Project Activate: Mindfulness and Acceptance Based Behavioral Treatment for Weight Loss. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04337619. |

Status active not recruiting, expected completion 24 May 2024. Registry last updated on 25 March 2022. |

|

Guerrini Usubini 2021 Guerrini Usubini A, Cattivelli R, Giusti EM, Riboni FV, Varallo G, Pietrabissa G, et al. The ACTyourCHANGE study protocol: promoting a healthy lifestyle in patients with obesity with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy‐a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2021;22(1):290. [DOI: 10.1186/s13063‐021‐05191‐y] NCT04474509. ACTyourCHANGE Study Protocol. Promoting Healthy Lifestyle With ACT for Obesity. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04474509 (first received 4 July 2020). |

Status recruiting, expected completion 30 September 2024. Registry last updated 1 March 2023. |

|

Hemenway 2021 NCT03734666. Development of a Mindfulness‐Based Treatment for the Reduction of Alcohol Use and Smoking Cessation. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03734666 (first received 4 July 2020). Hemenway M, Witkiewitz K, Unrod M, Brandon KO, Brandon TH, Wetter DW, et al. Development of a mindfulness‐based treatment for smoking cessation and the modification of alcohol use: A protocol for a randomized controlled trial and pilot study findings. Contemporary clinical trials 2021;100:106218. [DOI: 10.1016/j.cct.2020.106218] |

Status active not recruiting, registry last updated 26 January 2023. Results submitted 27 February 2023 and returned 22 March 2023 after quality control review. |

|

IRCT20150519022320N14 Comparative investigating the effect of relaxation and meditation techniques on quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=IRCT20150519022320N14 (first received 28 October 2018). |

Same. Status still recruiting, registry last updated 14 January 2019. |

|

IRCT2015122825739N1 Psychological interventions in weight loss. http://www.who.int/trialsearch/trial2.aspx?Trialid=IRCT2015122825739N1 (first received 1 September 2017). |

Same. Status still recruiting, expected end date 3 November 2018, registry last updated February 2018. |

| IRCT2016070126600N1 Effectiveness of mindfulness‐based stress reduction on Perceived Stress and blood pressure in high blood pressure patients. http://www.who.int/trialsearch/trial2.aspx?Trialid=IRCT2016070126600N1 (first received 23 July 2014). |

Results published ‐ re‐categorised as study awaiting classification (Khosravi 2016). |

| IRCT20190410043230N1 The Effect of Mindfulness Meditation, when Compared to routine education on Mental Health in Patients with Hypertension. https://trialsearch.who.int/?TrialID=IRCT20190410043230N1 (first received 23 July 2018). |

Results published ‐ re‐categorised as study awaiting classification (Babak 2022). |

|

IRCT20190804044436N1 Effect of mindfulness‐based stress management therapy on the emotion regulation, anxiety, depression and food addiction in obese people. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=IRCT20190804044436N1 (first received 21 September 2019). |

Same. Status complete, no results posted. Registry last updated February 2020. |

| IRCT20190924044866N1 Effect of an acceptance, mindfulness and compassionate‐based group intervention in overweight and obese women. https://trialsearch.who.int/?TrialID=IRCT20190924044866N1 (first received 22 October 2017). |

Results published ‐ re‐categorised as study awaiting classification (Pirmoradi 2022). |

| IRCT20200210046451N1 The Comparison of the effectiveness of mindfulness cognitive group psychotherapy and schema therapy on weight, body image and self‐esteem of people with obesity. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=IRCT20200210046451N1 (first received 6 March 2020). |

Results published ‐ re‐categorised as study awaiting classification (Bahadori 2022). |

|

IRCT20200225046618N1 Comparing the compassion‐focused therapy and dialectical behavior therapy training on state and trait anxiety symptoms and impulsivity in patients with coronary heart disease. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=IRCT20200225046618N1 (first received 15 December 2019). |

Same. Registry last updated 12 April 2020, recruitment complete. No results posted. |

|

IRCT20200226046625N1 Comparison of the Effectiveness of Cognitive‐Behavioral Therapy Based on Mindfulness and Education on Health Promoting Lifestyle in In treatment of diabetes. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=IRCT20200226046625N1 (first received 15 December 2019). |

Same. Registry last updated 24 March 2020, recruitment complete. No results posted. |

|

IRCT20200305046699N1 The Effectiveness of Group Therapy Based on Mindfulness and cognitive‐behavioral therapy (CBT) in the anxiety, metabolic control and quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=IRCT20200305046699N1 (first received 7 January 2020). |

Registry last updated 18 May 2020, status recruiting. |

| IRCT20200919048767N1 Effect of mindfulness training on weight loss. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=IRCT20200919048767N1 (first received 22 October 2020). |

Results published ‐ re‐categorised as study awaiting classification (Jassemi Zergani 2021). |

|

JPRN‐jRCT1030200197 Online Mindfulness‐Based Eating Awareness Training for obesity. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=JPRN‐Jrct1030200197 (first received 12 November 2020). |

Status recruiting, registry last updated 10 January 2022 |

|

JPRN‐UMIN000030444 Effects of a mindfulness‐based intervention versus cognitive behavioral therapy on weight loss and weight maintenance for women with overweight or obesity: a randomized controlled trial. https://trialsearch.who.int/?TrialID=JPRN‐UMIN000030444 (first received 19 December 2017). |

Status recruiting, registry last updated 10 October 2022 |

|

JPRN‐UMIN000042260 Effects of a Mindfulness‐Based Eating Awareness Training online intervention in adults of obesity: a randomized controlled trial. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=JPRN‐UMIN000042260 (first received 28 October 2020). |

Status recruitment pending, registry last updated 6 April 2022 |

|

JPRN‐UMIN000042626 An exploratory study of the Mindfulness App for Weight loss in metabolic syndrome. https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=JPRN‐UMIN000042626 (first received 31 March 2021). |

Status complete, follow‐up continuing. Registry last updated 6 July 2022 |

|

Martorella 2021 Martorella G, Hanley AW, Pickett SM, Gelinas C. Web‐ and Mindfulness‐Based Intervention to Prevent Chronic Pain After Cardiac Surgery: Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Research Protocols 2021;10(8):e30951. [DOI: /10.2196/30951] |

Same. Published protocol only, no trial registration found. Status recruiting (delays due to COVID pandemic). |

|

Mason 2019 Mason AE, Saslow L, Moran PJ, Kim S, Wali PK, Abousleiman H, et al. Examining the Effects of Mindful Eating Training on Adherence to a Carbohydrate‐Restricted Diet in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes (the DELISH Study): Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Research Protocols 2019;8(2):e11002. NCT03207711. Delish Study: Diabetes Education to Lower Insulin, Sugars, and Hunger (Delish). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03207711 (first received 5 July 2017). |

Same. Registry last updated 30 June 2021 when status is study complete, no results posted. Citation of analyses of lipid levels combining both groups so not relevant to this review. |

|

NCT00224835 Mindfulness‐Based Stress Reduction and Myocardial Ischemia. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00224835 (first received 23 September 2005). |