Abstract

Bovine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) continues to cause mortality in piglets and newborn calves. In an effort to develop a safe and effective vaccine for the prevention of F5+ ETEC infections, a balanced lethal asd+ plasmid carrying the complete K99 operon was constructed and designated pMAK99-asd+. Introduction of this plasmid into an attenuated Salmonella typhimurium Δaro Δasd strain, H683, resulted in strain AP112, which stably expresses E. coli K99 fimbriae. A single oral immunization of BALB/c and CD-1 mice with strain AP112 elicited significant mucosal immunoglobulin A (IgA) titers that remained elevated for >11 weeks. IgA and IgG responses in serum specific for K99 fimbriae were also induced, with a prominent IgG1, as well as IgG2a and IgG2b, titer. To assess the derivation of these antibodies, a K99 isotype-specific B-cell ELISPOT analysis was conducted by using mononuclear cells from the lamina propria of the small intestines (LP), Peyer’s patches (PP), and spleens of vaccinated and control BALB/c mice. This analysis revealed elevated numbers of K99 fimbria-specific IgA-producing cells in the LP, PP, and spleen, whereas elevated K99 fimbria-specific IgG-producing cells were detected only in the PP and spleen. These antibodies were important for protective immunity. One-day-old neonates from dams orally immunized with AP112 were provided passive protection against oral challenge with wild-type ETEC, in contrast to challenged neonates from unvaccinated dams or from dams vaccinated with a control Salmonella vector. These results confirm that oral Salmonella vaccine vectors effectively deliver K99 fimbriae to mucosal inductive sites for sustained elevation of IgA and IgG antibodies and for eliciting protective immunity.

Of the enteric diseases afflicting newborn calves, bovine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) infection remains a contributing cause of mortality in piglets and newborn calves (30, 43) and, in one survey, one of the leading causes of diarrhea in calves and piglets (43). The expression of K99 fimbriae (or F5+ ETEC) accounts for nearly all cases of ETEC infection found in newborn calves (2, 29, 30). E. coli becomes enterotoxigenic upon acquisition of a plasmid or plasmids containing the heat-stable enterotoxin (ST) (16, 30) and/or the heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) (7, 30, 41), both of which induce fluid loss and electrolyte imbalance. ETEC virulence is also dependent on the expression of fimbrial colonization factor antigens, which mediate the colonization of the gastrointestinal tract (25, 26, 30). This heterogeneous group of fimbrial adhesins also dictates host specificity (1, 3, 25, 26), and antibodies against these fimbriae have been implicated in protective immunity against ETEC infection in a number of animal and human systems (1, 15, 25, 26, 30, 32).

Conventional vaccines against bovine ETEC have been shown to provide varied immunity, and the effectiveness of these vaccines has been described only in anecdotal reports (30). Limited protection with purified K99 fimbriae or formalin-inactivated ETEC has been demonstrated (1, 15, 32), but the need for an efficacious vaccine against bovine ETEC still exists (30). The previously described variability in levels of protective immunity may have been due to the lack of stimulation of appropriate mucosal immunity, since these vaccines were delivered parenterally. As such, the development of a bacterium-vectored oral vaccination strategy prepared against ETEC fimbrial antigens has advantages. Oral bacterial vaccine vectors are inexpensive to manufacture, stable in storage, and simple to administer. Furthermore, these vectors permit vaccination against several antigens in a single oral administration. Finally, we have shown that Salmonella vectors effectively deliver ETEC fimbriae to mucosal inductive sites in the gut-associated lymphoreticular tissue (34–36, 48), a process which in previous studies by others has met with limited success (1, 13, 32) or has proven unsuccessful with purified ETEC fimbriae (15, 39). The uniqueness of this system relies on the capacity of attenuated Salmonella to be limited in growth and pathogenicity while retaining the ability to stimulate passenger antigen-specific responses in the host’s mucosal and systemic compartments by sustaining antigen production (6, 17).

Consequently, various Salmonella vaccine vectors have been employed for delivery of antigens to mucosal inductive tissues (5, 6, 20, 31, 36, 38, 44, 48). Recently, we showed that oral immunization of mice with a Salmonella vector that expressed human ETEC colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I) stimulated increases in immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG antibodies specific for CFA/I fimbriae (48). This finding supported the principle that Salmonella vectors provide a powerful means to induce mucosal and systemic responses against ETEC fimbriae. Interestingly, an analogous E. coli-CFA/I fimbria construct failed to induce increases in CFA/I fimbria-specific antibodies (48).

In this report, we confirm the capacity of Salmonella vectors to deliver ETEC fimbriae to mucosal inductive tissues by using a balanced lethal stabilized Salmonella-K99 construct that expresses K99 fimbriae on the surface of the vector. Moreover, we show distinct antibody response patterns that developed in the mucosal and systemic compartments following a single oral vaccination with the Salmonella-K99 vaccine construct. These immune responses against K99 fimbriae provided protective immunity in pups challenged with wild-type F5+ ETEC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, plasmids, and antisera.

ETEC B41, a wild-type F5+ strain (which expresses K99 and F41 fimbriae and StaP), was kindly provided by Richard E. Issacson, Department of Veterinary Pathology, University of Illinois, Urbana. E. coli NADC 2323, containing plasmid pFK99, and the rabbit anti-K99 fimbria antiserum were kindly provided by Thomas A. Casey, Enteric Diseases Research Unit, United States Department of Agriculture, Ames, Iowa. E. coli H681, a Δasd mutant strain, and S. typhimurium H683, a Δaro Δasd mutant strain (48), were used as recipient strains for transformations of the recombinant asd+ plasmid carrying the K99 genetic determinants. S. typhimurium H647, an isogenic, non-fimbria-expressing strain, was used as a control for immunogenicity studies (48). All strains were cultured by using both Luria-Bertani (LB) and Minca (8) media with or without antibiotics. NADC 2323 was grown in both media containing carbenicillin (100 μg/ml). The host strains H681 and H683 were grown in both media supplemented with diaminopimelic acid (50 μg/ml). Neither H681 nor H683 grows on these media unless the asd+ allele is supplied in trans. The control strain, H647, was grown in the media without diaminopimelic acid supplementation. Plasmid pFK99, containing the entire operon for expression of K99 fimbriae, and plasmid pYA292 (17), containing the asd gene, were used. All strains used for development of K99 fimbriae constructs are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Salmonella and E. coli constructs used for development of K99 fimbria vaccines

| Bacterial strain | Parent strain | Attenuation | Plasmid | K99 fimbriae | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. typhimurium | |||||

| SL 7207 | SL 1344 | ΔaroA | None | None | 48 |

| H683 | SL 7207 | ΔaroA Δasd | None | None | 17, 48 |

| H647 | H683 | ΔaroA Δasd | pJRD184-asd+ | None | 48, this study |

| AP112 | H683 | ΔaroA Δasd | pMAK99-asd+ | Present | This study |

| E. coli | |||||

| H681 | χ6212 | Δasd | None | None | 17, 48 |

| AP111 | H681 | Δasd | pMAK99-asd+ | Present | This study |

| NADC 2323 | C600 | thr leu-6 thi-1 supE44 lacY1 tonA21 | pFK99 | Present | 9 |

Salmonella vaccine construction.

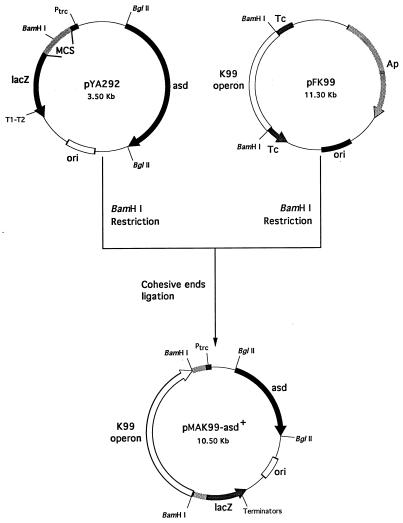

Plasmid pMAK99-asd+ was constructed by subcloning the K99 operon, fanABCDEFGH (9, 21, 24), from plasmid pFK99 as a 7.0-kb BamHI fragment into plasmid pYA292. By using a Gene Pulser set at 129Ω, 25F, and 1.5 kV (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California), plasmid pMAK99-asd+ was electroporated into E. coli H681, an asd-negative strain, to obtain the balanced lethal strain, E. coli AP111. The purified plasmid obtained from strain AP111 was then electroporated into S. typhimurium H683, an asd-negative strain, to obtain the balanced lethal Salmonella construct, strain AP112. Selection for transformants was achieved by growth on LB agar plates without diaminopimelic acid supplementation. Clones containing the pMAK99-asd+ construct were detected by colony immunoblotting, plasmid minipreps, and slide agglutination protocols.

Purification of K99 fimbriae.

Since K99 fimbrial expression is regulated by growth rate, alanine concentration, and catabolite repression system, strains producing K99 fimbriae were cultured primarily in Minca medium (45). Strains expressing K99 fimbriae were cultured for 20 h at 37°C and rocked at 200 rpm. K99 fimbriae were purified and adapted by using a previously described protocol (8, 23). After the cell concentration was adjusted to 108 CFU/ml, the cell suspension (same volume) was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g, and the pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The bacteria were subjected to heat shock at 65°C for 30 min to obtain K99 fimbriae. This procedure was shown to remove most of the K99 fimbriae (>90%) from the cells. The bacteria were pelleted at 12,000 × g for 5 min, and the K99 fimbriae were precipitated from the supernatant by adding ammonium sulfate (60% saturation) and stirring for 2 h at 4°C. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 15,000 × g, resuspended in 1.0 ml of PBS, and dialyzed against the same buffer for 16 h at 4°C. The dialyzed K99 fimbrial suspension was then concentrated to 1.0 ml, and the purity of the isolated K99 fimbriae was evaluated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The protein concentration was determined by using the Lowry method (Bio-Rad).

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Comparative SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis of K99 fimbriae from S. typhimurium AP112, E. coli AP111 and NADC 2323, and the E. coli wild type, B41, were performed by using standard procedures. For Western blot analysis, proteins were transferred from the SDS-PAGE (15% [wt/vol] polyacrylamide) gel to 0.2-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). The membranes were probed first with the rabbit polyclonal K99 fimbrial antiserum and then with a goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc. [SBA], Birmingham, Ala.). Detection of K99 fimbriae was achieved upon development with the substrate 4-chloro-1-naphthol chromogen and H2O2 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.).

Immunizations.

An isolated colony of either S. typhimurium AP112 or H647 was grown on Minca agar plates for 24 h at 37°C. Bacteria were harvested from the plates in 5 ml of PBS. Bacterial suspensions were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 4 min, and the bacterial pellets were resuspended in 1.0 ml of PBS. The density of the bacteria was adjusted by optical density measurement at 600 nm and confirmed by serial dilutions on LB agar plates. Groups of BALB/c and CD-1 mice, pretreated with a 50% saturated sodium bicarbonate solution, received a single oral dose of 5 × 109 CFU (contained in 0.2 ml) of S. typhimurium AP112 vaccine or strain H647. This AP112 construct was found to stably express K99 fimbriae, as demonstrated by the ability to agglutinate the bacteria with K99 fimbria-specific antiserum and by SDS-PAGE analysis of the recovered Salmonella between 2 and 3 weeks following oral immunization.

Antibody ELISA.

Antibody titers in serum and fecal samples were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) adapted from previously described methods (44, 48). Briefly, K99 fimbriae (1.0 μg/ml) in sterile PBS, pH 7.2, were used to coat Maxisorp Immunoplate II microtiter plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) at 100 μl/well, and the plates were incubated overnight at room temperature. Various dilutions of immune mouse serum or fecal extracts were diluted in ELISA buffer (PBS, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 0.05% Tween 20) and incubated overnight at 4°C. Specific reactivities to K99 fimbriae were determined with horseradish peroxidase conjugates of the following detecting antibodies (1.0 μg/ml): goat anti-mouse IgA, IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibodies (SBA). Following 90 min of incubation at 37°C and a washing step, the specific reactivity was determined by the addition of an enzyme substrate, ABTS [2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline 6-sulfonic acid)diammonium; Moss, Inc., Pasadena, Calif.] at 100 μl/well, and absorbance was measured at 415 nm on a Kinetics Reader model EL312 (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, Vt.). End point titers were expressed as the reciprocal log2 of the last sample dilution giving an absorbance of ≥0.1 optical density units above negative controls after 1 h of incubation.

B-cell ELISPOT.

Splenic lymphocytes were isolated by conventional methods by passage through sterile mesh wire screens (48). Mononuclear cell suspensions were obtained from Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient (Lympholyte M; Accurate Chemical, Westbury, N.Y.) centrifugation. Lymphocytes from Peyer’s patches (PP) and the lamina propria (LP) were released from tissue stroma by enzymatic digestion as previously described (48). Greater than 95% viability was noted for lymphocytes isolated from the spleen, PP, and LP, as determined by trypan blue exclusion. The PP, splenic, and small-intestine LP mononuclear cells were resuspended in complete medium (RPMI 1640; Bio-Whittaker, Walkersville, Md.) containing 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone, Logan, Utah) plus the supplements (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.), HEPES buffer (10 mM), l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). K99 fimbria-specific and total IgA and IgG spot-forming cells (SFC) were enumerated in cell suspensions by using the ELISPOT method (46, 48). Briefly, 96-well nitrocellulose bottom-based plates (Milltiter, HA; Millipore Corporation, Belford, Mass.) were coated with 1.0 μg of K99 fimbriae per ml diluted in PBS for the enumeration of K99-specific SFC and with 5 μg of goat anti-mouse IgG or IgA antibodies (SBA) per ml diluted in PBS for examination of total IgG or IgA SFC. Between 5 × 104 and 5 × 105 mononuclear cells were added to K99 fimbria-coated wells, and between 1 × 104 and 5 × 104 mononuclear cells were added to antibody-coated wells. Samples were done in triplicate, and cells were incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. Following washing, peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse IgG or IgA antibodies (1 μg/ml; SBA) in ELISA buffer were added and cells were incubated overnight at 4°C. After the wells were washed, spots were visualized upon addition of the chromogenic substrate 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Moss, Inc.). Spots were enumerated with the aid of a dissecting microscope (Stereozoom 5 microscope; Leica, Buffalo, N.Y.).

Neonatal challenge with wild-type ETEC.

The Duchet-Suchaux neonatal ETEC challenge model (10, 11) was adapted for our studies. Briefly, CD-1 female mice were orally immunized with either S. typhimurium AP112 or the isogenic H647 construct (lacks K99 fimbriae), and an unvaccinated control group was also used. After 3 weeks, the mice were mated. Pups were allowed to receive colostrum and milk for 24 h following birth and then were challenged with 103 bovine ETEC B41 bacteria in a 10-μl volume. Pups were monitored for 10 days for their survival.

Statistical analysis.

The Student t test and the Tukey one-way analysis of variance test were used to show differences in K99 fimbria-specific antibody responses.

RESULTS

Development of a balanced lethal stabilized Salmonella construct, AP112.

Passenger antigen stability is a critical parameter that dictates immunogenicity. Since it is inappropriate to use antibiotic resistance markers for candidate human or livestock live vaccine vectors, we chose to construct a balanced lethal plasmid in which a plasmid-based asd+ allele complemented the lethal chromosomal asd mutant allele in the recipient Salmonella strain, for stable expression of K99 fimbriae. This construct, designated pMAK99-asd+ (Fig. 1), was introduced into the host, S. typhimurium H683 (asd mutant), to allow the development of a stable Salmonella-K99 construct, AP112. To remain viable, the AP112 construct is required to maintain the pMAK99-asd+ plasmid in the absence of diaminopimelic acid, since this construct carries a null genomic asd allele. As such, pMAK99-asd+ allowed for the stable expression of K99 fimbriae.

FIG. 1.

Construction of pMAK99-asd+. A BamHI fragment containing the fanABCDEFGH operon from plasmid pFK99 was subcloned into the BamHI site of pYA292. The derived plasmid, pMAK99-asd+, stably expresses K99 fimbria antigen in the asd-negative strains S. typhimurium H683 and E. coli H681.

Expression of K99 by S. typhimurium AP112.

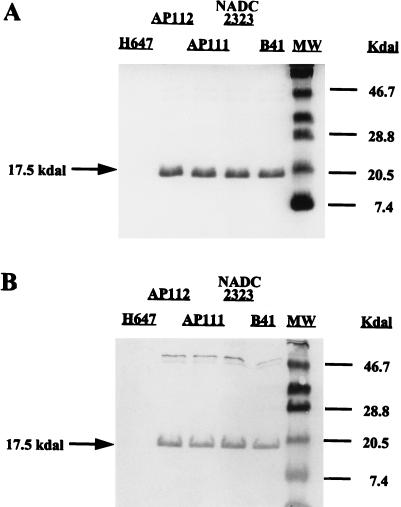

Expression of the K99 operon is highly regulated by three separate gene clusters (21, 24): region I, containing fanA to fanD; region II, containing fanE and fanF; and region III containing fanG and fanH. Each region is regulated independently by the global regulators cyclic AMP-cyclic AMP receptor protein and Lrp (leucine-responsive protein), indicating that each region is probably expressed from a different promoter. By using Minca medium, optimal regulation and expression of K99 fimbriae can be obtained (5, 45). The expression of K99 fimbriae derived from the Salmonella construct was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis. As depicted in Fig. 2, AP112, E. coli AP111, NADC 2323, and the wild-type ETEC strain, B41, expressed similar levels of K99 fimbriae under these conditions. The functional characteristics of the results with Salmonella-expressed K99 fimbriae were confirmed by horse erythrocyte hemagglutination (47) to demonstrate ligand binding (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE (A) and Western blot analysis (B) of isolated K99 fimbriae derived from S. typhimurium and E. coli K99 fimbria-expressing strains. Lanes (left to right): isogenic S. typhimurium H647 without K99 operon; S. typhimurium-K99 fimbria construct, strain AP112; E. coli-K99 fimbria construct, strain AP111; E. coli NADC 2323 with plasmid pFK99; the wild-type E. coli K99+ strain, B41; molecular size (MW) markers in kilodaltons (Kdal) (ovalbumin, 46.7; soybean trypsin inhibitor, 28.8; lysozyme, 20.5; and aprotinin, 7.4). To demonstrate that the isolated protein obtained from the various strains was K99 fimbria, the nitrocellulose-transferred proteins were reacted with K99 fimbria-specific rabbit antiserum. The AP111 and AP112 constructs were shown to express the K99 fimbriae when compared to the K99+ E. coli strains producing the fimbriae of the expected 17.5 kDa, whereas no fimbriae were obtained from the K99− asd+ S. typhimurium strain, H647.

Oral immunization of BALB/c and CD-1 mice with the AP112 construct elicits elevated K99 fimbria-specific IgA and IgG antibodies.

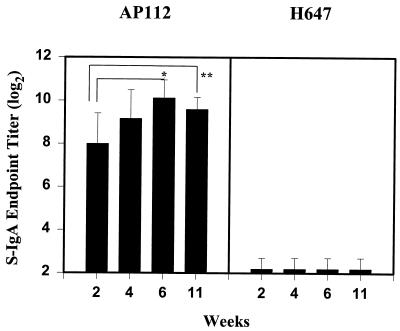

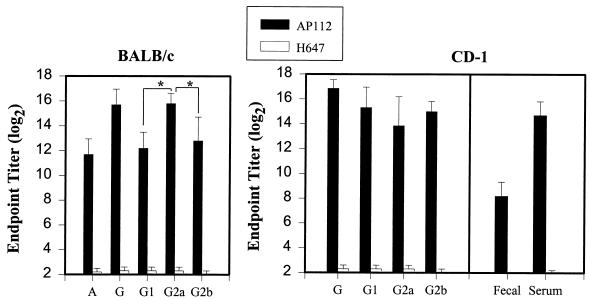

Previous studies suggest that mucosal immunity is required for protection against ETEC infection (25, 26). However, oral immunization with ETEC fimbriae has been problematic due to the sensitivity of these antigens to natural host defenses (15, 39). To assess the effectiveness of AP112 in delivering K99 fimbriae to mucosal inductive tissues, two different strains of mice were used: inbred BALB/c mice and outbred CD-1 mice. BALB/c mice were used to assess the immune responsiveness of this strain to AP112 for future T-cell studies. The outbred CD-1 mice were used due to their utility in challenge studies, since CD-1 newborn pups are susceptible to bovine ETEC infections. BALB/c mice (n = 8) and CD-1 mice (n = 7) received a single oral dose of AP112 (5 × 109 CFU). Measurements of mucosal IgA antibodies specific for K99 fimbriae in fecal pellets from BALB/c and CD-1 mice were made at 2, 4, 6, and 11 weeks and at 4 weeks, respectively, following the initial oral immunization (Fig. 3 and 4). For BALB/c mice, elevated IgA titers to the K99 fimbriae in fecal pellets were obtained within 2 weeks. Log2 IgA titers in fecal pellets averaged 8 ± 1.4 (mean ± standard deviation), and this value increased maximally between 4 and 6 weeks, to titers of 9.2 ± 1.3 and 10.1 ± 0.8, respectively (Fig. 3). Likewise, similar increases in IgA responses in fecal pellets were obtained for the CD-1 mice, to titers of 8.2 ± 1.1 at 4 weeks postimmunization (Fig. 4). There was no significant difference between the two mouse strains in their mucosal IgA anti-K99 fimbria titers at this time point. Furthermore, 11 weeks after the original immunization, the IgA titers in fecal pellets remained elevated (9.6 ± 0.6) (Fig. 3). BALB/c mice (n = 8) orally immunized with the Salmonella vector control, S. typhimurium H647, did not induce measurable secretory IgA (S-IgA) antibodies against K99 fimbriae. For both mouse strains, elevations in IgA titers in serum were noted at 4 weeks: BALB/c mice produced a titer of 11.7 ± 1.3, and CD-1 mice produced a titer of 14.7 ± 1.1 (Fig. 4), which represented an eightfold greater response than that of the BALB/c mice (P < 0.001).

FIG. 3.

K99 fimbria-specific IgA responses in fecal pellets were induced after oral immunization of mice with a single dose of S. typhimurium AP112 and not with the Salmonella vector control, strain H647. Depicted are the means plus standard deviations of the K99 fimbria-specific IgA log2 end point titers in fecal pellets that developed after 2, 4, 6, and 11 weeks of oral immunization of mice with 5 × 109 CFU. Mucosal IgA antibody titers to K99 fimbriae were determined by ELISA. ∗, significantly different between 2 and 6 weeks (P = 0.003); ∗∗, significantly different between 2 and 11 weeks (P = 0.036). S-IgA, secretory IgA.

FIG. 4.

K99 fimbria-specific IgA and IgG responses after oral immunization of BALB/c mice and CD-1 mice with a single dose of strain AP112. Depicted are the means plus standard deviations of the K99 fimbria-specific IgA and IgG subclass log2 end point titers in serum that developed at 4 weeks after oral immunization of mice with 5 × 109 CFU. IgA, IgG, and IgG subclass antibody titers in serum and fecal pellets were determined by standard ELISA methods. Both strains of mice produced elevated antibody titers, but the CD-1 mice exhibited higher IgA (P < 0.001) and IgG (P = 0.046) titers in serum than BALB/c mice did. For BALB/c mouse results, an asterisk indicates that K99 fimbria-specific IgG2a titers were significantly different from K99 fimbria-specific IgG1 and IgG2b titers (P < 0.001). IgG1 and IgG2b titers were not significantly different from each other. For CD-1 mice, the IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibody titers were not statistically different from each other; however, the IgG1 (P = 0.001), IgG2a (P = 0.046), and IgG2b (P = 0.015) titers were statistically different between mouse strains.

In previous studies, while Salmonella vectors have been effective in eliciting IgG responses in serum, these responses were generally dominated by IgG2a. This subclass pattern is thought to reflect an underlying Th1-driven response. It was of interest to examine IgG antibody and IgG subclass responses to K99 fimbriae in serum. As shown in Fig. 4, the IgG antibody titers in serum peaked 4 weeks after oral immunization in BALB/c (15.7 ± 1.25) and CD-1 mice (16.9 ± 0.69). Upon examination of K99 fimbria-specific IgG subclass responses in serum from BALB/c mice, IgG2a antibody titers represented the dominant IgG subclass phenotype response (15.8 ± 0.84), followed by IgG2b (12.8 ± 1.92) and IgG1 (12.2 ± 1.3). There were significant differences between K99-specific IgG2a responses and K99-specific IgG1 (P < 0.001) and IgG2b (P < 0.001) responses. In contrast, for CD-1 mice, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibody titers were not statistically different in their magnitudes. In addition, when antibody titers within subclasses were compared, it was found that the CD-1 mice produced significantly higher antibody titers than the BALB/c mice did (Fig. 4). Collectively, these data provide further evidence of the effectiveness of oral immunization with a single dose of this Salmonella-K99 construct. Moreover, it is important to note that these IgG1 antibody titers were markedly elevated in both murine strains, which is unusual for Salmonella-delivered passenger antigens.

Elevations in antibodies to K99 fimbriae in serum are derived from host mucosal and systemic compartments.

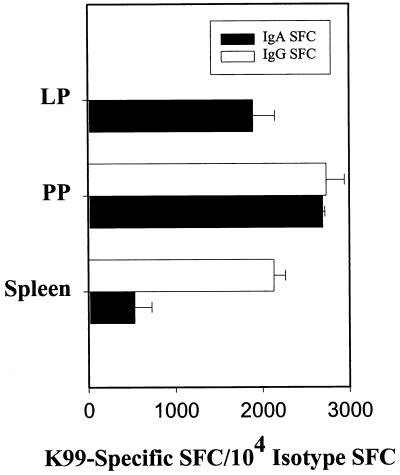

In light of the elevated K99 fimbria-specific IgA and IgG antibody responses that were evident in mucosal secretions and serum, it was important to establish the origin of the K99 fimbria-specific antibody responses. To this end, small-intestine LP, PP, and splenic mononuclear cells from AP112-immunized BALB/c mice were examined by a B-cell ELISPOT assay. Elevations in K99 fimbria-specific SFC were observed in all tested mononuclear cell populations 4 weeks after oral immunization (Fig. 5). The predominant SFC response was of the IgA isotype in the PP and LP, where between 1,900 and 2,700 IgA SFC/104 IgA+ cells were K99 fimbria-specific. In contrast, fewer IgA anti-K99 fimbria SFC were detected in the spleen (529 ± 338 IgA SFC/104 IgA+ cells). Surprisingly, though, similar numbers of IgG SFC were detected in PP and splenic mononuclear cells (2,735 ± 336 and 2,130 ± 230 IgG SFC/104 IgG+ cells, respectively). These results imply that the origin of the IgA and IgG antibodies was primarily the gut-associated lymphoreticular tissue.

FIG. 5.

K99 fimbria-specific IgA and IgG SFC responses after oral immunization of mice with strain AP112. K99 fimbria-specific and total IgA and IgG SFC responses in LP, PP, and splenic mononuclear cells were measured by ELISPOT at 4 weeks after oral immunization. Depicted are the means plus standard deviations of K99 fimbria-specific IgA and IgG SFC per 104 IgA+ and IgG+ SFC, respectively, that developed.

Oral immunization with AP112 provides protective passive immunity to neonates orally challenged with wild-type bovine ETEC.

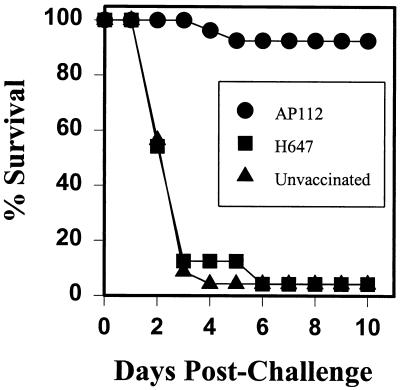

The Duchet-Suchaux model of testing neonatal outbred mice against challenge with wild-type K99+ ETEC (10) provides a rapid means to determine whether AP112 can provide adequate protective immunity. From the evidence provided thus far, it is clear that AP112 can stimulate sustained, elevated mucosal IgA responses to K99 fimbriae. To test whether the antibodies induced via passive immunity can prevent attachment of ETEC to the neonatal intestinal epithelium, CD-1 female mice were used in these studies since it has been shown previously that outbred mice are susceptible to bovine B41 ETEC (10) whereas BALB/c mice are not (11). CD-1 female mice were orally immunized with strain AP112 or the Salmonella vector control strain, H647, or were left unvaccinated. Following oral immunization, the mice were rested; this was done to ensure that the Salmonella vector-induced bacteremia, which could interfere with gestation, had been resolved. Subsequently, females were mated and allowed to come to parturition. Neonates from each group were allowed to obtain colostrum and milk for the first 24 h subsequent to their birth and then were orally challenged with 103 wild-type ETEC, from strain B41. The neonates were allowed to remain with their respective dams and were monitored for survival. Pups (n = 27) from the AP112-vaccinated group showed greater than 92% survival for more than 10 days (Fig. 6). In contrast, both unvaccinated and H647-vaccinated dams were unable to provide passive protective immunity to their respective pups (Fig. 6). Most pups died within 4 days postchallenge, and only one pup in each control group (H647-vaccinated group, n = 24 pups; unvaccinated control group, n = 23 pups), or only approximately 4%, survived beyond 10 days. These data suggest that humoral immunity, be it IgA, IgG, or both, can provide passive immunity to prevent infection with wild-type ETEC in this neonatal challenge model.

FIG. 6.

Oral immunization of CD-1 female mice with AP112 provides passive immunity to pups orally challenged with B41, the wild-type ETEC strain. AP112- and H647-vaccinated as well as unvaccinated dams were mated. Pups from each group were allowed to receive colostrum and milk for the first 24 h after birth, after which the pups were orally challenged with 103 K99 fimbria-positive cells of wild-type ETEC, strain B41, and monitored for survival for 10 days. Oral immunization with AP112 provided passive immunity to wild-type ETEC-challenged mice, as demonstrated by the survival of 25 of 27 pups. In contrast, pups from dams vaccinated with Salmonella vector only (n = 24) or unvaccinated (n = 23) died.

DISCUSSION

Since the initial proposal to use Salmonella organisms to deliver fimbrial antigens (3, 31, 42, 50), construction of such recombinants that stably express high levels of CFA/I, K88, and K99 fimbriae has evolved from the utilization of antibiotic-based vectors (3, 50) and nonantibiotic-based vectors (for plasmid retention and antigen expression) (4, 42) to the present well-established balanced lethal stabilization system in Salmonella (17, 36, 48). Here we report the construction of a balanced lethal stabilized Salmonella-K99 vaccine construct, AP112, which is capable of expressing K99 fimbriae and eliciting strong antibody responses in mice against K99 fimbriae after a single oral immunization. Likewise, in previous work (48), this balanced lethal stabilization system was used for the generation of the Salmonella-CFA/I strain, H683(pJGX15C-asd+), that is capable of stably expressing CFA/I fimbriae in the absence of cfaR. The obvious advantage of this system is that this new Salmonella-K99 fimbria construct can stably express the K99 fimbriae in vivo for appropriate stimulation of the mucosal inductive tissues. Although others have used Salmonella strains with the nonantibiotic thyA system to express ETEC fimbriae and good IgG responses were obtained (4, 31), the thyA system is not 100% stable. The thyA system is not a lethal mutation and has the potential to produce a reversion to a wild-type phenotype.

The results clearly demonstrate that oral immunization of BALB/c and CD-1 mice with the Salmonella-K99 construct, AP112, was sufficient to elicit elevated IgA responses in serum and mucosal tissues as well as increases in systemic IgG antibody responses to the K99 fimbriae. Moreover, the derivation of mucosal IgA antibodies was generated locally in the small-intestine LP and PP. A significant portion of the IgG response was also derived from the PP, suggesting that a portion of the IgG response in serum was derived mucosally. In contrast, the isogenic Salmonella K99-negative control strain, H647, failed to elicit specific antibody responses to K99 fimbriae in serum or mucosal tissues. Similar results were obtained when the Salmonella-CFA/I construct, H683(pJGX15C-asd+), was used (48).

These data show that appropriate stimulation of mucosal inductive tissues by using Salmonella vaccine vectors can elicit both mucosal and systemic immunity. Simply administering antigens orally may not be sufficient unless such antigen can be directed to the small-intestine mucosal inductive sites, i.e., PP, as in the case for cholera toxin (22, 49) or microspheres (14). Alternatively, live-vector delivery systems with propensities to enter or target mucosal inductive sites are more likely to effectively stimulate the appropriate T- and B-cell subsets (36). This was substantiated with our attenuated E. coli construct expressing CFA/I fimbriae, by which very weak anti-CFA/I fimbria responses were obtained after a single oral immunization (48). Again this evidence suggests that appropriate targeting to the PP is important.

While we observed increases in IgG2a and IgG2b antibody responses in serum, dramatic increases in IgG1 K99 fimbria-specific antibody titers were also noted and were similar to the increases in IgG2b antibody titers. Such increases in IgG1-specific titers have not been noted with other Salmonella constructs (19, 40, 44) until recently (12, 18, 34–36). This observation would suggest that T helper 2 (Th2) cell mechanisms may be contributing to this immune response since work to date has shown that CD4+ Th1-type responses are elicited predominantly after oral immunization with Salmonella (27, 37, 44). This idea of Th2-type involvement is further suggested by the sustained increases in IgA antibody responses (36). Although it has been shown that Salmonella can stimulate S-IgA responses presumably via an alternate pathway, presumably by the induction of other Th2-type cytokines, e.g., interleukin 6 (IL-6) and IL-10 (33, 44), IgA responses are optimally supported by IL-4 and IL-5 (28). Studies to determine which CD4+-Th-cell phenotype is induced as a consequence of oral immunization with strain AP112 are in progress. Understanding how Th-cell subsets are induced following vaccine delivery will aid in future designs of Salmonella vaccine vectors.

The K99 fimbriae expressed by strain AP112 appeared to be similar to those expressed by wild-type K99+ ETEC. They did retain their immunogenicity, as evident in this study, and were recognized by a polyclonal rabbit anti-K99 fimbria antibody developed outside our laboratory. This retention of immunogenicity is important since passive immunity could be demonstrated by the ability of immunized dams to provide immune protection to orally challenged pups with the wild-type ETEC strain, B41. Greater than 90% of these pups survived challenge with wild-type ETEC, in comparison to only a 4% survival rate for pups that were either immunized with a control Salmonella vector or unimmunized.

In conclusion, this work has described the construction of a balanced lethal stabilized Salmonella-K99 fimbria construct and has demonstrated that this construct is capable of eliciting elevated antibodies in both mucosal and systemic compartments. The data suggest that antibodies can mediate protective immunity to ETEC. It will be of interest to determine whether antibody responses of such magnitude and segregation in IgG subclass responses are also obtained following oral immunization in cows.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by USDA grant 960-2195; in part by the USDA Animal Health Formula Funds; in part by the Montana Agricultural Station (D.W.P.); by NIH grants AI 42603 and AI 41914 (D.M.H.); and in part by the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust.

We thank Peter Hillemeyer and Matt Rognlie for their expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acres S D, Isaacson R E, Babiuk L A, Kapitany R A. Immunization of calves against enterotoxigenic colibacillosis by vaccinating dams with purified K99 antigen and whole-cell bacterins. Infect Immun. 1979;25:121–126. doi: 10.1128/iai.25.1.121-126.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acres S D. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infections in newborn calves: a review. J Dairy Sci. 1985;58:229–256. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(85)80814-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attridge S R, Hackett J, Morona R, Whyte P. Towards a live oral vaccine against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli of swine. Vaccine. 1988;6:387–389. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(88)90134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attridge S R, Davies R, LaBrooy J T. Oral delivery of foreign antigens by attenuated Salmonella: consequences of prior exposure to the vector strain. Vaccine. 1997;15:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertram E M, Attridge S R, Kotlarski I. Immunogenicity of the Escherichia coli fimbrial antigen K99 when expressed by Salmonella enteritidis 11RX. Vaccine. 1994;12:1372–1378. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatfield S, Roberts M, Londono P, Cropley I, Douce G, Dougan G. The development of oral vaccines based on live attenuated Salmonella strains. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1993;7:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1993.tb00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clements J D, Finkelstein R A. Demonstration of shared and unique immunologic determinants in enterotoxins from Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1978;22:709–713. doi: 10.1128/iai.22.3.709-713.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Graaf F K, Klemm P, Gaastra W. Purification, characterization, and partial covalent structure of Escherichia coli adhesive antigen K99. Infect Immun. 1981;33:877–883. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.3.877-883.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Graaf F K, Krenn B E, Klaasen P. Organization and expression of genes involved in the biosynthesis of K99 fimbriae. Infect Immun. 1984;43:508–514. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.508-514.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duchet-Suchaux M. Protective antigens against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli O101:K99,F41 in the infant mouse diarrhea model. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1364–1370. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1364-1370.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duchet-Suchaux M, Le Maitre C, Bertin A. Differences in susceptibility of inbred and outbred infant mice to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli of bovine, porcine, and human origin. J Med Microbiol. 1990;31:185–190. doi: 10.1099/00222615-31-3-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunstan S J, Simmons C P, Strugnell R A. Comparison of the abilities of different attenuated Salmonella typhimurium strains to elicit humoral immune responses against a heterologous antigen. Infect Immun. 1998;66:732–740. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.732-740.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelman R, Russell R G, Losonsky G, Tall B D, Tacket C O, Levine M M, Lewis D H. Immunization of rabbits with enterotoxigenic E. coli colonization factor antigen (CFA/I) encapsulated in biodegradable microspheres of poly (lactide-co-glycolide) Vaccine. 1993;11:155–158. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90012-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eldridge J H, Staas J K, Meulbroek J A, McGhee J R, Tice T R, Gilley R M. Biodegradable microspheres as a vaccine delivery system. Mol Immunol. 1991;28:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(91)90076-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans D G, Graham D Y, Evans D J, Opekun A. Administration of purified colonization factor antigens (CFA/I, CFA/II) of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli to volunteers. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:934–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Field M, Graf L H, Laird W J, Smith P L. Heat-stable enterotoxin of Escherichia coli: in vitro effects on guanylate cyclase activity, cyclic GMP concentration and ion transport in the small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:2800–2804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galan J E, Nakayama K, Curtiss R., III Cloning and characterization of the asd gene of Salmonella typhimurium: use in stable maintenance of recombinant plasmids in Salmonella vaccine. Gene. 1990;94:29–35. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90464-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harokopakis E, Hajishengallis G, Greenway T E, Russell M W, Michalek S. Mucosal immunogenicity of a recombinant Salmonella typhimurium-cloned heterologous antigen in the absence or presence of coexpressed cholera toxin A2 and B subunits. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1445–1454. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1445-1454.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hohmann E L, Oletta C A, Loomis W P, Miller S I. Macrophage-inducible expression of a model antigen in Salmonella typhimurium enhances immunogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2904–2908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hone D, Attridge S, van der Bosh L, Hackett J A. Chromosomal integration system for stabilization of heterologous genes in Salmonella-based vaccine strains. Microb Pathog. 1988;5:407–418. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue O J, Lee J H, Isaacson R E. Transcriptional organization of the Escherichia coli pilus adhesin K99. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:607–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson R J, Fujihashi K, Xu-Amano J, Kiyono H, McGhee J R. Optimizing oral vaccines: induction of systemic and mucosal B-cell and antibody responses to tetanus toxoid by use of cholera toxin as an adjuvant. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4272–4279. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4272-4279.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karkhanis Y D, Bhogal B S. A single-step isolation of K99 pili from B-44 strain of Escherichia coli. Anal Biochem. 1986;155:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J H, Isaacson R E. Expression of the gene cluster associated with the Escherichia coli pilus adhesin K99. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4143–4149. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4143-4149.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levine M, Morris J G, Losonsky G, Boedeker E C, Rowe B. Fimbriae (pili) adhesins as vaccine. In: Lark D L, Normark S, Uhlin B E, Wolf-Watz H, editors. Protein-carbohydrate interactions in biological systems: molecular biology of microbial pathogenicity. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press Ltd.; 1986. pp. 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine M M, Giron J A, Noriega F R. Fimbrial vaccines. In: Klemm P, editor. Fimbriae: adhesins, biogenics, genetics, and vaccines. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1994. pp. 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mastroeni P, Villarreal-Ramos B, Hormaeche C E. Role of T cells, TNF-α and IFN-γ in recall of immunity to oral challenge with virulent Salmonella in mice vaccinated with live attenuated aro− Salmonella vaccines. Microb Pathog. 1992;13:477–491. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90014-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McIntyre T M, Kehry M R, Snapper C M. Novel in vitro model for high-rate IgA class switching. J Immunol. 1995;154:3156–3161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moon H W. Colonization factor antigens of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in animals. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;151:147–167. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74703-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moon H W, Bunn T O. Vaccines for preparing enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infections in farm animals. Vaccine. 1993;11:213–219. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(93)90020-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morona R, Morona J K, Considine A, Hackett J A, van den Bosh L, Beyer L, Attridge S R. Construction of K88- and K99-expressing clones of Salmonella typhimurium G30: immunogenicity following oral administration to pigs. Vaccine. 1994;12:513–517. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagy B. Vaccination of cows with a K99 extract to protect newborn calves against experimental enterotoxic colibacillosis. Infect Immun. 1980;27:21–24. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.1.21-24.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okahashi N, Yamamoto M, VanCott J L, Chatfield S N, Roberts M, Bluethmann H, Hiroi T, Kiyono H, McGhee J R. Oral immunization of interleukin-4 (IL-4) knockout mice with a recombinant Salmonella strain or cholera toxin reveals that CD4+ Th2 cells producing IL-6 and IL-10 are associated with mucosal immunoglobulin A responses. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1516–1525. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1516-1525.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pascual D W, Hone D M, Hall S, van Ginkel F W, Yamamoto M, Fujihashi K, Powell R J, Wu S, VanCott J L, Kiyono H, McGhee J R. Mode of vaccine expression by Salmonella dictates Th cell response: Th2 precedes Th1 cell anti-enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) fimbriae responses. FASEB J. 1996;10:A1082. . (Abstract 480.) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pascual D W, Powell R, Lewis G K, Hone D M. Oral bacterial vaccine vectors for the delivery of subunit and nucleic acid vaccines to the organized lymphoid tissue of the intestine. Behring Inst Mitt. 1997;98:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pascual D W, Walters N, Hillemeyer P, Loetterle L, Powell R J, Hone D M. Placement of vaccine antigen onto surface of Salmonella typhimurium alters the Th cell phenotype from Th1 to Th2 type response following oral immunization. J Allerg Clin Immunol. 1997;99(Part 2):S34. . (Abstract 141.) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramarathinam L, Niesel D W, Klimpel G R. Salmonella typhimurium induces IFN-γ production in murine splenocytes: role of natural killer cells and macrophages. J Immunol. 1993;150:3973–3981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts M, Chatfield S N, Dougan G. Salmonella as carriers of heterologous antigens. In: O’Hagen D T, editor. Novel delivery systems for oral vaccines. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1994. pp. 27–58. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt M, Kelley E P, Tseng L Y, Boedeker E C. Towards an oral E. coli pilus vaccine for travelers’ diarrhea: susceptibility to proteolytic digestion. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:A1575–A1582. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schodel F, Kelly S M, Peterson D L, Milich D R, Curtiss R. Hybrid hepatitis B virus core-pre-S proteins synthesized in avirulent Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella typhi for oral vaccination. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1669–1676. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1669-1676.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spangler B D. Structure and function of cholera toxin and the related Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:622–647. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.622-647.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stevenson G, Manning P A. Galactose epimerase (galE) mutant G30 of Salmonella typhimurium is a good potential oral vaccine carrier for fimbrial antigens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1985;28:317–320. [Google Scholar]

- 43.U.S. Department of Agriculture. DxMonitor: animal health report. Fort Collins, Colo: Veterinary Service, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 44.VanCott J L, Staats H F, Pascual D W, Roberts M, Chatfield S N, Yamamoto M, Coste M, Carter P B, Kiyono H, McGhee J R. Regulation of mucosal and systemic antibody response by T helper cell subsets, macrophages, and derived cytokines following oral immunization with live recombinant Salmonella. J Immunol. 1996;156:1504–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Woude M W, Arts P A, Bakker D, van Verseveld H W, de Graaf F K. Growth-rate-dependent synthesis of K99 fimbrial is regulated at the level of transcription. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:897–903. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-5-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Ginkel F W, Liu C-G, Simecka J, Dong J-Y, Greenway T, Frizzell R A, Kiyono H, McGhee J R, Pascual D W. Intratracheal gene delivery with adenoviral vector induces elevated systemic IgG and mucosal IgA antibodies to adenovirus and β-galactosidase. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:895–903. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.7-895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willemsen P T J, de Graaf F K. Multivalent binding of K99 fimbriae to the N-glycolyl-GM3 ganglioside receptor. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4518–4522. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4518-4522.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu S, Pascual D W, VanCott J L, McGhee J R, Maneval D R, Jr, Levine M M, Hone D M. Immune responses to novel Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium vectors that express colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I) of enterotoxigenic E. coli in the absence of the CFA/I positive regulator cfar. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4933–4938. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4933-4938.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu-Amano J, Kiyono H, Jackson R J, Staats H F, Fujihashi K, Burrows P D, Elson C O, Pillai S, McGhee J R. Helper T cell subsets for immunoglobulin A responses: oral immunization with tetanus toxoid and cholera toxin as adjuvant selectively induces Th2 cells in mucosa associated tissues. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1309–1320. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto T, Tamura Y, Yokota T. Enteroadhesion fimbriae and enterotoxin of Escherichia coli: genetic transfer to a streptomycin-resistant mutant of the galE oral-route live-vaccine Salmonella typhi Ty21a. Infect Immun. 1985;50:925–928. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.3.925-928.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]