Abstract

Several studies have shown that γδ T cells influence granuloma development after infection with intracellular pathogens. The role of γδ T cells in controlling the influx of inflammatory cells into the lung after Mycobacterium avium infection was therefore examined with gene-disrupted mice (K/O). The mice were infected with either M. avium 724, a progressively replicating highly virulent strain of M. avium, or with M. avium 2-151 SmT, a virulent strain that induces a chronic infection. γδ-K/O mice infected with M. avium 2-151 SmT showed early enhanced bacterial growth within the lung compared to the wild-type mice, although granuloma formation was similar in both strains. γδ-K/O mice infected with M. avium 724 showed identical bacterial growth within the lung compared to the wild-type mice, but they developed more-compact lymphocytic granulomas and did not show the extensive neutrophil influx and widespread tissue necrosis seen in wild-type mice. These data support the hypothesis that isolates of M. avium that induce protective T-cell-specific immunity are largely unaffected by the absence of γδ T cells. Whereas with bacterial strains that induce poor protective immunity, the absence of γδ T cells led to significant reductions in both the influx of neutrophils and tissue damage within the lungs of infected mice.

Mycobacterium avium is the most common cause of disseminated bacterial infection among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals in the United States and Europe (2, 8, 13). Infection typically occurs late in the course of the AIDS disease, when CD4+-T-cell counts are below 100/mm3 (7, 25). Successful treatment of M. avium infection is difficult, not only because of the suppressed state of the host’s immune system but also because of a lack of effective antibiotics to treat the infection and the concurrent development of resistance to currently available drugs (17, 18, 22).

Infection of HIV-positive individuals with M. avium is thought to occur through the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract, with systemic spread being a common feature of this disease (7, 19). In the HIV-negative population M. avium generally presents as a pulmonary disease, and both systemic and pulmonary infection cause disabling disease in infected individuals (9, 15). M. avium infection typically leads to the generation of large, diffuse granulomatous lesions within infected tissue, such as the lung and lymph nodes. Characteristically, these lesions are filled with foamy macrophages, neutrophils, and a smaller percentage of lymphocytes. Tissue necrosis and fibrosis are common features of pulmonary M. avium infections (11, 20).

Recent studies in mice have suggested that the inflammatory response generated after infection with several intracellular pathogens, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is controlled in part by γδ T cells (10, 27, 29). While they constitute only a minor T-cell population (1 to 5%) within lymphoid organs, γδ T cells are a predominant T-cell population within epithelial tissues, including the skin, gut, and airways (16). They accumulate in infected tissue, including lesions from leprosy patients, and in vitro they produce an extensive array of cytokines and chemokines after antigenic stimuli (3, 6). γδ T cells recognize a range of mycobacterial proteins in vitro, including low-molecular-weight proteins and nonprotein ligands, often without the need for previous antigen processing and presentation (4, 6, 30). In addition, γδ T cells taken from patients with AIDS that are infected with mycobacteria recognize mycobacterial antigens in vitro (28). A recent epidemiological study found that γδ T-cell numbers were increased in HIV-M. avium- coinfected individuals but not in patients with HIV-M. tuberculosis coinfections, thus suggesting a role for γδ T cells in response to M. avium infection in patients with AIDS (24).

To investigate the hypothesis that γδ T cells control the influx of inflammatory cells into the lung after M. avium infection, gene-disrupted (γδ-K/O) mice were infected with M. avium, and the disease progression was monitored. In these experiments the mice were infected with either M. avium 724 or a smooth transparent isolate of M. avium 2-151 (2-151 SmT). Strain 724 is a highly virulent M. avium isolate that grows progressively within mice (12). Strain 2-151 SmT is also a virulent isolate, which induces strong protective immunity resulting in a chronic infection (12). Mice were infected by aerosol exposure to a low bacterial dose in order to mimic one of the natural routes of infection in humans. We report here that the contribution of γδ T cells to immunity to M. avium varies depending upon the infective strain used. Infection of γδ-K/O mice with M. avium, while having only a transient influence upon the growth of bacteria, significantly affected the inflammatory response generated within the lungs. γδ-K/O mice developed lesions containing a higher proportion of lymphocytes and, in the case of infection with M. avium 724, they did not show the extensive neutrophil influx nor the development of caseated lesions seen in wild-type-infected mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Breeding pairs of T-cell receptor Cγ gene mutant mice (C57BL/6J-Tcrdtm/mom and JR2120) (23) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) and bred in the Laboratory Animal Resources Center at Colorado State University. Wild-type controls (C57BL/6J) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories as required. Age- and sex-matched mice were kept under barrier conditions in the ABL-3 biohazard facility throughout the experiment. The specific-pathogen-free nature of each colony was shown by testing sentinel animals; these were determined to be negative for 12 known mouse pathogens.

Bacteria and infection.

M. avium 724 and 2-151 SmT were grown from laboratory stocks in Proskauer-Beck liquid medium to mid-log phase, aliquoted, and then frozen at −70°C. Mice were infected with approximately 500 bacteria by using a Middlebrook Airborne Infection apparatus (Middlebrook, Terre Haute, Ind.) as previously described (26). The numbers of viable bacteria in the lung, spleen, and liver were determined at various time points by plating serial dilutions of organ homogenates on nutrient Middlebrook 7H11 agar and counting the bacterial colonies after 14 days of incubation at 37°C. The data are expressed as the log10 value of the mean number of bacteria recovered per organ (n = four animals).

Histology.

Tissues from four mice per experimental group were infused with fresh 10% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. Sections made from paraffin blocks were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Consecutive sections were stained for acid-fast bacilli by the Kinyoun staining procedure. Sections were examined by a veterinary pathologist without prior knowledge of the experimental groups.

Statistical analysis.

Differences between the mean of experimental groups were analyzed by using the Student t test. Differences were considered significant when P was <0.05.

RESULTS

Variation in the growth of two strains of M. avium in γδ-K/O mice.

Strains 724 and 2-151 SmT are virulent serotype-2 strains of M. avium that have been extensively studied in this laboratory. Both generate protective T-cell immunity early during the course of the infection, and as a result the growth of 2-151 SmT is restrained, giving rise to a chronic disease state. In contrast, however, mice infected with 724 gradually lose their expression of acquired immunity (9a), for reasons as yet completely unknown, allowing the infection to grow progressively.

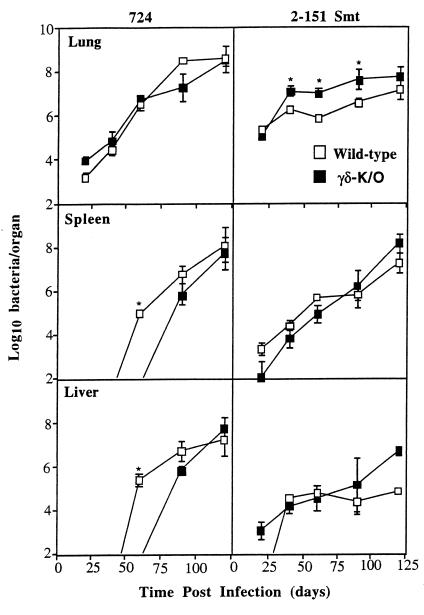

To test the hypothesis that γδ T cells are involved in these mechanisms, we examined the course of infection with these two bacterial strains in mice lacking this cell population. Wild-type mice infected with M. avium 724 showed progressive bacterial growth within the lung and dissemination to the liver and spleen (Fig. 1). γδ-K/O mice showed identical bacterial growth in the lung, although dissemination into these organs was significantly delayed (P < 0.05).

FIG. 1.

Bacterial growth in γδ-K/O mice infected with M. avium 724 or 2-151 SmT. γδ-K/O mice and their wild-type littermate controls were infected with approximately 500 bacilli via aerosol. Bacterial load was assessed up to 120 days postinfection. Data are expressed as the mean ± the standard deviation (n = 4). ∗, P < 0.05.

Mice infected with M. avium 2-151 SmT developed a chronic bacterial infection, with bacilli initially growing to a number 1 log higher in the lungs of the γδ-K/O mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). By day 120, however, the differences in bacterial loads between the two mouse strains were no longer significant. Moreover, no differences were seen in the pattern of dissemination of M. avium 2-151 SmT between the wild-type and the γδ-K/O mice.

Differences in the inflammatory response generated in γδ-K/O mice.

The lungs of wild-type and γδ-K/O mice infected with M. avium had significant differences in lesion type, with the severity differing between the two bacterial strains (Table 1). Wild-type mice infected with M. avium 724, while showing progressive bacterial growth, did not mount a strong inflammatory response to the invading bacteria during the first 60 days of infection. There was some thickening of the alveolar septae by lymphocytes and macrophages along with scattered small foci of lymphocytes, but no large rafts of macrophages or lymphocytes were present (Fig. 2A). By day 90, the lungs of the wild-type mice had extensive granulomas with severe caseation surrounded by a thick wall of degenerative neutrophils that were in turn surrounded by a rim of epithelioid macrophages (Fig. 2C, enlarged in Fig. 3A to C). Acid-fast staining of consecutive lung sections revealed extensive numbers of bacilli within the epithelioid macrophage layer surrounding the wall of degenerative neutrophils (Fig. 3D).

TABLE 1.

Lung histology in wild-type and γδ-K/O mice infected aerogenically with M. avium 724 or 2-151 SmT

| Time postinfection (days) | Lung histology in mice infected with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

M. avium 2-151 SmT

|

M. avium 724

|

|||

| Wild type | γδ-K/O | Wild type | γδ-K/O | |

| 40 | Minimal granulomatous pneumonia with few lymphocytic cells | Minimal granulomatous pneumonia with few lymphocytic cells | Minimal lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia | Minimal lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia |

| 60 | Mild granulomatous pneumonia with few lymphocytic cells | Mild granulomatous pneumonia with increased number of lymphocytic cells | Minimal lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia | Minimal lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia |

| 90 | Mild to moderate granulomatous pneumonia with increased number of lymphocytic cells | Moderate granulomatous pneumonia with markedly increased number of lymphocytic cells | Severe granulomatous pneumonia with caseation and few lymphocytic cells | Marked granulomatous pneumonia with increased number of lymphocytic cells |

| 120 | Moderate granulomatous pneumonia with increased number of lymphocytic cells | Moderate to marked granulomatous pneumonia with markedly increased number of lymphocytic cells | Severe granulomatous pneumonia with caseation and few lymphocytic cells | Severe granulomatous pneumonia with increased number of lymphocytic cells |

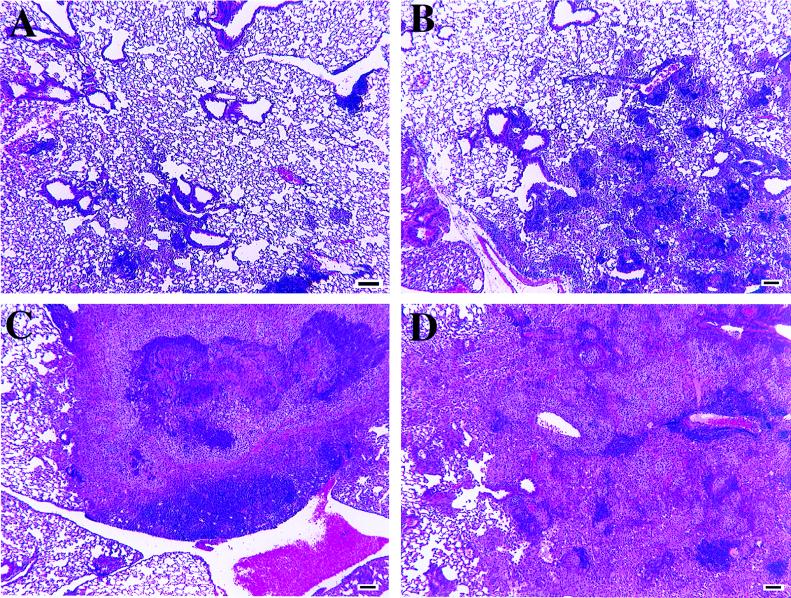

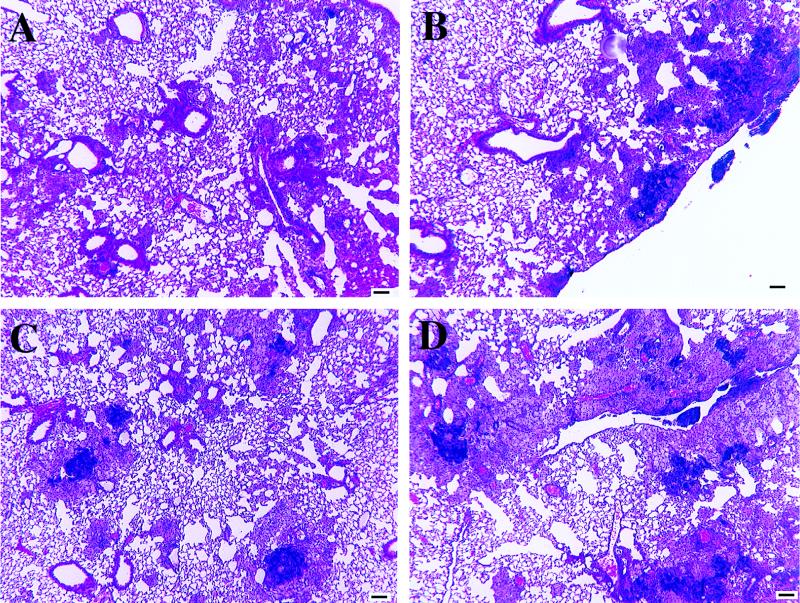

FIG. 2.

Representative low-magnification photomicrographs of lung tissue from wild-type and γδ-K/O mice infected with M. avium 724. (A) Wild-type mice at 60 days postinfection. Note the limited cellular infiltrates composed of scattered lymphocyte foci, including apparent bronchial alveolar lymphatic tissue expansion. The lungs of γδ-K/O mice were similar in appearance at this time point. (B) γδ-K/O mice at 90 days postinfection. There are multiple small granulomas composed predominantly of macrophages and lymphocytes with few neutrophils. (C) Wild-type mice at 90 days postinfection. A large focus of necrosis with central caseation can be seen, with lesions surrounded by neutrophils and then cuffed with macrophages (enlarged in Fig. 3). (D) γδ-K/O mice at 120 days postinfection. Large granulomatous lesions composed primarily of macrophages with a few foci of neutrophils are evident. Lymphocyte numbers appear to have waned since day 90. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used. Bar, 100 μm.

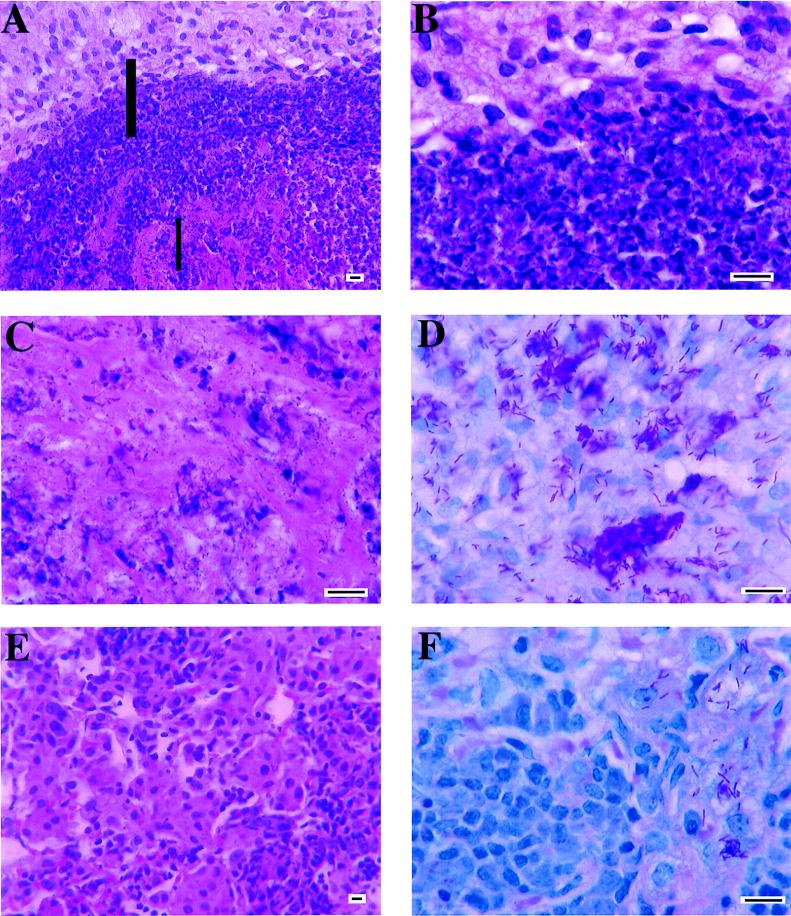

FIG. 3.

Representative high-magnification photomicrograph of lung tissue from mice infected with M. avium 724. (A) Section of a caseated lesion in a wild-type mouse at 90 days postinfection. Note the concentrated laminated rings of degenerative neutrophils (middle) and epithelioid macrophages (top) surrounding the central caseation (bottom). The thick-bar area is magnified in panel B; the thin-bar area is magnified in panel C. (B) Higher magnification of the neutrophilic lamina (bottom) with the epithelioid macrophages (top). (C) The center of the caseated area contains amorphous debris. (D) Acid-fast bacilli in macrophages. This is a magnification of the area of panel A just above the thick bar. (E) Section of a noncaseated lesion in a γδ-K/O mouse at 90 days postinfection. Note that the lesion is composed primarily of macrophages and lymphocytes. (F) Acid-fast bacilli in macrophages from a γδ-K/O mouse at 90 days postinfection. The panel is a magnification from an area similar to that shown in panel E. Panels A, B, C, and E were stained with hematoxylin and eosin; panels D and F were stained with Kinyoun’s stain. Bar, 10 μm.

In contrast, γδ-K/O mice developed a markedly different granulomatous response to infection with M. avium 724. Although the initial response was similar to that seen in the controls, the γδ-K/O mice failed to develop the caseous lesions prominent in the wild-type mice. Granulomas in the K/O mice were composed primarily of lymphocytes and macrophages, with only small pockets of neutrophils present (Fig. 2B, enlarged in Fig. 3E). Acid-fast staining showed the bacilli within the macrophages (Fig. 3F). At 120 days postinfection, granulomatous involvement in the lungs of the γδ-K/O mice had increased, but granulomas were still composed primarily of lymphocytes and macrophages with only small numbers of neutrophils (Fig. 2D).

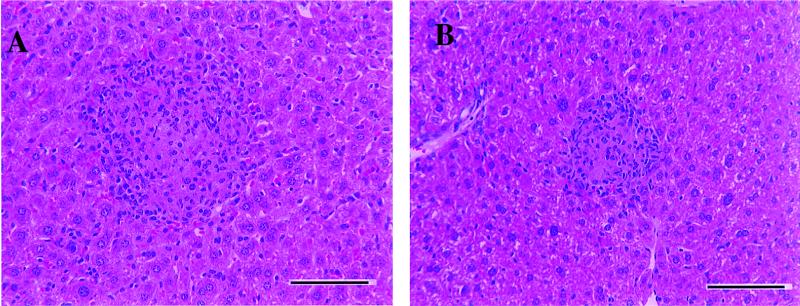

The significant differences seen in granuloma formation in the lungs of wild-type and γδ-K/O mice were not evident in the other organs investigated. Examination of the liver revealed that both mouse strains developed multifocal granulomatous hepatitis (Fig. 4). Granuloma formation in the spleen and kidney also did not differ significantly between the two mouse strains (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Representative moderate-magnification photomicrograph of liver tissue from M. avium 724-infected mice. (A) Wild-type mice at 120 days postinfection. Cellular infiltrates resulting in the formation of multifocal granulomatous hepatitis are shown. (B) γδ-K/O mice at 120 days postinfection. This image is similar to panel A, with cellular infiltrates resulting in the formation of multifocal granulomatous hepatitis. Panels were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Bar, 100 μm.

While wild-type mice infected with M. avium 724 clearly showed evidence of caseation and necrosis, such was not the case in mice infected with M. avium 2-151 SmT. Thickening of the alveolar septae by macrophages and lymphocytes was visible earlier in these mice, often by 20 days postinfection, and small granulomas composed primarily of lymphocytes and macrophages began to form by around day 40. These granulomas continued to increase in size throughout the infection, but caseation was never observed (Fig. 5). γδ-K/O mice infected with M. avium 2-151 SmT developed granulomas with a higher lymphocytic proportion than those seen in the wild-type mice, and these differences were especially apparent by 90 days postinfection, when the lymphocyte influx into the lungs appeared to peak (Fig. 5D). Neutrophil influx into the lungs of wild-type and γδ-K/O mice was only minor over the 120-day time course examined, with no major differences apparent in response to M. avium 2-151 SmT infection between the two mouse strains.

FIG. 5.

Representative low-magnification photomicrographs of lung tissue from M. avium 2-151 SmT-infected mice. (A) Wild-type mice at 60 days postinfection. Cellular infiltrates resulting in the formation of primary granulomas composed predominantly of macrophages with few lymphocytes are shown. This response was prominent earlier than the one shown in Fig. 2. (B) γδ-K/O mice at 60 days postinfection. The lesions are similar to those in Fig. 4A, but the proportion of lymphocytes is higher than in the wild type. (C) Wild-type mice at 90 days postinfection. The lymphocytic granulomas are larger than at 60 days postinfection (Fig. 4A). (D) γδ-K/O mice at 90 days postinfection. The γδ K/O mice also showed an increase in granuloma formation. These are composed predominantly of macrophages and lymphocytes, with the proportion of lymphocytes being higher than in the wild type (Fig. 4C). Panels were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Bar, 100 μm.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that, when bacterial growth remains unchecked, as in the M. avium 724 infection, the presence of γδ T cells in the host can be detrimental and appears to accelerate the destructive pathogenic response. If, however, the bacterial infection remains chronic, as in the 2-151 SmT infection, then the γδ T cells appear to play no significant role in disease progression.

The key observation reported here concerns the necrotic nature of the lesions in strain 724-infected mice. In M. avium-infected individuals a high bacterial burden within the lungs is usually accompanied by extensive tissue necrosis and fibrosis (2, 11, 13, 15, 20). Like the lesions seen in humans, wild-type mice infected with M. avium 724 developed lesions composed predominantly of neutrophils and macrophages. Perhaps as a consequence of the high bacterial numbers in this animal model, extensive tissue necrosis was also seen, with some necrotic lesions progressing to a caseated state.

An indication of the mechanism involved in the generation of this pathogenic response is provided by the observations reported here. Specifically, while the bacterial loads in the wild-type and γδ-K/O mice were equivalent, the lesion development was significantly different. In contrast to the extensive degenerating lesions seen in the wild-type mice, the lung lesions of the γδ-K/O mice infected with strain 724 consisted of small granulomas containing mixtures of macrophages and lymphocytes. By comparing histological samples from different time points it was evident that progression of the pathogenic response was slower in the γδ-K/O mice. By day 120 of the experiment, lung lesions in the K/O mice had increased to a size similar to those of the wild-type mice 1 month earlier. However, the lesions were composed of vast fields of epithelioid macrophages, with a few scattered aggregates of lymphocytes and with no overt necrosis evident.

While the absence of γδ T cells diminished the necrosis and tissue damage seen within the strain 724-infected mice, this was not the case in M. avium 2-151 SmT-infected animals. Both wild-type and γδ-K/O mice infected with 2-151 SmT developed similar lymphocytic lesions, which were composed predominantly of macrophages and lymphocytes, except that lesions in the γδ-K/O mice appeared to be more lymphocytic in nature.

One possible explanation for the differences in lesion formation induced by the two strains of M. avium may be in the immune response each one induces. Protective immunity to M. avium requires an inflammatory cell influx to surround and contain infected macrophages and a protective T-cell response to activate macrophages to kill infecting bacilli. M. avium 2-151 SmT induces both the influx of inflammatory cells to surround infected macrophages and, as previously shown, a strong acquired immune response (14) that controls bacterial growth such that a chronic disease state then ensues. Mice aerogenically infected with strain 724 show no ability to contain bacterial growth. Early in the infection only a mild interstitial pneumonia was seen within the lungs of infected mice, and cells were not recruited to surround infected macrophages. It appears, therefore, that a protective acquired immune response was not generated. Indeed M. avium 724 grows identically in both CD4 K/O and wild-type mice (28a). Studies in this laboratory (9a) found that intravenous infection with 724 does appear to generate acquired immunity during the early course of the infection but, for reasons that are currently unclear, this specific resistance is then gradually lost, thus allowing the infection to grow progressively and eventually kill the animal.

We postulate that in mice aerogenically infected with strain 724, once the bacterial load reaches a critical threshold, γδ T cells, driven by recognition of mycobacterial antigens (4, 5, 31) and/or recognition of damaged or infected self (21), produce a cytokine-chemokine response that stimulates the influx of inflammatory cells, particularly macrophages into infected tissue. These macrophages are detrimental to the mouse since they serve as host cells for the pathogen and, because of the absence of protective αβ T cells, they remain inactivated and gradually degenerate, causing local tissue damage and an influx of neutrophils. In the absence of γδ T cells, this inflammatory cell influx is diminished and less tissue damage is seen.

In M. avium 2-151 SmT-infected mice, where a protective gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-producing αβ T-cell response is generated (1), macrophages entering infected tissues become activated and are able to control bacterial growth. In the absence of γδ T cells, more lymphocytes were seen in lesions in the lung, suggesting that the presence of γδ T cells dampens the recruitment of lymphocytes to the infected tissue. In 2-151 SmT-infected mice, because of the presence of a protective acquired immune response, the macrophages recruited by γδ T cells become activated and are able to control bacterial growth. As the bacterial growth is controlled the amount of tissue damage and mycobacterial debris is also reduced. In this situation therefore, unlike in the strain 724-infected tissue, there was a much lower stimulus for the recruitment of neutrophils and the development of necrosis and caseation.

In support of this hypothesis, studies investigating the role of γδ T cells in other infections have shown repeatedly that γδ T cells, while often not directly affecting the growth of the infective pathogen, still control inflammatory processes in response to infection (10, 27, 29). In the absence of γδ T cells, infected mice generally developed larger more-diffuse lesions, with an increase in tissue necrosis and abscess formation being common.

Indeed, in M. tuberculosis infection the absence of γδ T cells led to the development of a pyogranulomatous inflammatory response with lesions containing increased numbers of neutrophils and large foamy macrophages, distinct from the lymphocytic granulomas formed in the wild-type mice (10). While this data appears to contradict our data, we would contend that it is the recruitment of macrophages by γδ T cells into a nonimmune site that leads to the potential for larger more necrotic lesions. Thus, in strain 724-infected mice, γδ T cells stimulate a macrophage influx, but no protective αβ T-cell response is present to activate these macrophages, and as a result bacterial growth continues and the macrophages degenerate, stimulating a neutrophil influx which increases the tissue damage seen. In contrast, in M. tuberculosis-infected mice, γδ T cells still stimulate a macrophage influx; however, these cells are activated by the protective αβ T-cell response, and bacterial growth is controlled. In the absence of γδ T cells, macrophage recruitment is diminished and so we see the rapid growth of M. tuberculosis in a low macrophage environment which results in rapid tissue damage and the subsequent recruitment of neutrophils.

Finally, this animal model, if extrapolated, may have implications for HIV-positive patients infected with M. avium. The implication here is that a failure of acquired cellular immunity expressed by CD4 T cells allows an opportunistic M. avium infection to disseminate and grow. Meanwhile, the γδ T-cell response inadvertently promotes this process by amplifying the recruitment of macrophages into lesions, but the absence of IFN-γ-secreting CD4 T cells results in astronomic bacterial loads and pathogenic lesions. This model is therefore similar to the disease progression in HIV-positive patients with disseminated M. avium infections and may be useful in identifying mechanisms of pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David Ealy and staff of the Laboratory Animal Center, Colorado State University, for animal care.

This work was supported by National Institute Health grants AI40488 and AI41922.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appelberg R, Castro A G, Pedrosa J, Silva R A, Orme I M, Minoprio P. Role of gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha during T-cell-independent and -dependent phases of Mycobacterium avium infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3962–3971. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3962-3971.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson, C. A. 1994. Disease due to the Mycobacterium avium complex in patients with AIDS: epidemiology and clinical syndrome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 18(Suppl. 3):S218–S222. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Boismenu R, Havran W L. An innate view of γδ T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boom W. The role of T-cell subsets in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect Agents Dis. 1996;5:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandler P, Frater A J, Douek D C, Viney J L, Kay G, Owen M J, Hayday A C, Simpson E, Altmann D M. Immune responsiveness in mutant mice lacking T-cell receptor alpha beta+ cells. Immunology. 1995;85:531–537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chein Y, Jores R, Crowley M P. Recognition by γ/δ T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:511–532. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin D P, Hopewell P C, Yajko D M, Vittinghoff E, Horsburgh C R, Hadley W K, Stone E N, Nassos P S, Ostroff S M, Jacobson M A, Matkin C C, Reingold A L. Mycobacterium avium complex in the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract and the risk of M. avium complex bacteremia in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:289–295. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin D P, Reingold A L, Stone E N, Vittinghoff E, Horsburgh C R, Simon E M, Yajko D M, Hadley W K, Ostroff S M, Hopewell P C. The impact of Mycobacterium avium complex bacteremia and its treatment on survival of AIDS patients—a prospective study. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:578–584. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Contreras M A, Cheung O T, Sanders D E, Goldstein R S. Pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:149–152. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Cooper, A. M. Unpublished observations.

- 10.D’Souza C D, Cooper A M, Frank A A, Mazzaccaro R J, Bloom B R, Orme I M. An anti-inflammatory role for gamma delta T lymphocytes in acquired immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1997;158:1217–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farhi D C, de Mason U G, Horsburgh C R. Pathologic findings in disseminated Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection. A report of 11 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1986;85:67–72. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/85.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Florido M, Appelberg R, Orme I M, Cooper A M. Evidence for a reduced chemokine response in the lungs of beige mice infected with Mycobacterium avium. Immunology. 1997;90:600–606. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.French A L, Benator D A, Gordin F M. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81:361–379. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70522-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furney S K, Skinner P S, Farrer J, Orme I M. Activities of rifabutin, clarithromycin, and ethambutol against two virulent strains of Mycobacterium avium in a mouse model. Antimocrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:786–789. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffith D E. Nontuberculous mycobacteria. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1997;3:139–145. doi: 10.1097/00063198-199703000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas W, Pereira P, Tonegawa S. Gamma/delta cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:637–685. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.003225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heifets L, Mor N, Vanderkolk J. M. avium strains resistant to clarithromycin and azithromycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2364–2370. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heifets L B. Clarithromycin against Mycobacterium avium complex infections. Tubercle Lung Dis. 1996;77:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(96)90070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horsburgh C R. Mycobacterium avium complex infection in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1332–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105093241906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalayjian R C, Toossi Z, Tomashefski J F J, Carey J T, Ross J A, Tomford J W, Blinkhorn R J J. Pulmonary disease due to infection by Mycobacterium avium complex in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1186–1194. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.5.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallick-Wood C A, Lewis J M, Richie L I, Owen M J, Tigelaar R E, Hayday A C. Conservation of T cell receptor conformation in epidermal γδ cells with disrupted primary Vγ gene usage. Science. 1998;279:1729–1732. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masur H. U.S. Public Health Service task force on prophylaxis and therapy for M. avium complex. Recommendations on prophylaxis and therapy for disseminated M. avium complex disease in patients infected with HIV (special report) N Engl J Med. 1993;329:898–904. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309163291228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mombaerts P, Arnoldi J, Russ F, Tonegawa S, Kaufmann S H E. Different roles of alpha beta and gamma delta T cells in immunity against an intracellular bacterial pathogen. Nature. 1993;365:53–56. doi: 10.1038/365053a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreau J F, Taupin J L, Dupon M, Carron J C, Ragnaud J M, Marimoutou C, Bernard N, Constans J, Texier-Maugein J, Barbeau P, Journot V, Dabis F, Bonneville M, Pellegrin J L. Increases in CD3+ CD4+ CD8− T lymphocytes in AIDS patients with disseminated Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infection. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:969–976. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nightingale S D, Byrd L T, Southern P M, Jockusch J D, Cal S X, Wynne B A. Incidence of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex bacteremia in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:1082–1085. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.6.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orme I M. The kinetics of emergence and loss of mediator T lymphocytes acquired in response to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1987;138:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts S J, Smith A L, West A B, Wen L, Findly R C, Owen M J, Hayday A C. T-cell alpha beta+ and gamma delta+ deficient mice display abnormal but distinct phenotypes toward a natural, widespread infection of the intestinal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11774–11779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruiz P, Geraldino N. Peripheral gamma delta T-cell populations in HIV-infected individuals with mycobacterial infection. Cytometry. 1995;22:211–216. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990220308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28a.Saunders, B. M., and I. M. Orme. Unpublished data.

- 29.Thoma-Uszynski S, Ladel C H, Kaufmann S H. Abscess formation in Listeria monocytogenes-infected gamma delta T-cell-deficient mouse mutants involves alpha beta T cells. Microb Pathog. 1997;22:123–128. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsukaguchi K, Balaji K N, Boom W H. CD4+ alpha beta T cell and gamma delta T cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Similarities and differences in Ag recognition, cytotoxic effector function, and cytokine production. J Immunol. 1995;154:1786–1796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wesch D, Marx S, Kabelitz D. Comparative analysis of alpha beta and gamma delta T cell activation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and isopentenyl pyrophosphate. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:952–956. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]