Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this systematic review is to fill the gap in a critical understanding of peer-reviewed empirical research on self-care practices to identify structural, relational, and individual-level facilitators and barriers to self-care practices in social work.

Method:

We followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis for this systematic review of peer-reviewed quantitative and qualitative empirical research articles focusing on self-care in social work among adult social work practitioners and students.

Results:

Twenty-one articles related to empirical studies of self-care were identified in the systematic review process with samples of social work practitioners (n = 15), social work students (n = 3), and social work educators (n = 3).

Discussion:

Social workers engaged in self-care practices are more likely to be healthy, work less, be White, and have higher socioeconomic professional status and privilege, indicating current conceptualizations of self-care may not be accessible and contextually and culturally relevant for many social workers.

Conclusion:

Overwhelmingly, results indicated social workers reporting greater sociostructural, economic, professional, and physical health privilege engaged in more self-care. No articles directly assessed institutional factors that may drive distress among social workers and clients. Rather, self-care was framed as a personal responsibility without integration of feminized and racialized inequities in a sociopolitical and historical context. Such framings may replicate rather than redress unsustainable inequities experienced by social workers and clients.

Keywords: Self-care, compassion fatigue, social work, self-compassion

Self-care, or intentional actions people and organizations take to promote wellness and reduce stress (Bloomquist et al., 2016), is thought to buffer the incessant demands and under-resourced feminized professions, such as social work. The National Association of Social Worker’s (National Association of Social Workers, 2021) code of ethics compels integration of self-care into social work practice and states: “Professional self-care is paramount for competent and ethical social work practice. Professional demands, challenging workplace climates, and exposure to trauma warrant that social workers maintain personal and professional health, safety, and integrity” (Purpose of NASW Code section). Though self-care gains primacy, barriers make its practice inaccessible for many social workers (National Association of Social Workers, 2021; Weinberg, 2014). Social workers have always navigated contexts of high-stress and demanding situations increasingly marked by incessant business, information overload, and an “always on” mentality, often across work and home life (Author[s], 2021; Pyles, 2020).

Social work is a feminized profession characterized by high percentages of women in the workforce, yet they are underpaid and occupy fewer leadership roles than their male counterparts (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). Around 90% of Master of Social Work (MSW) graduates between 2017 and 2019 are women (Salsberg et al., 2020). Women are more likely than men to be flooded and overburdened by exposure to structural sexism (Homan, 2019) in the forms of disparities in the home-life balance, underpayment, violence, trauma, and role strain (WHO, 2021). Structural sexism targeting feminized work is evident given research examining longitudinal data from 1960–2010; data demonstrate that when women enter a profession, wages fall, on average, 9% for men and 13% for women (Harris, 2022). This feminization of the workforce and associated devaluation of “women’s work” bears out in occupational status and concomitant pay.

Background: facilitators and barriers to self-care

The state of empirical research investigating ecological barriers and facilitators to self-care remain in its infancy. Empirical knowledge of self-care facilitators and barriers is a relatively recent area for inquiry, with most research from the last decade (Ashley-Binge & Cousins, 2020; Griffiths et al., 2019; Lizano, 2015; McFadden et al., 2015; Mor Barak et al., 2001). Prior to conducting this review, the five systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and narrative literature reviews that could be located were reviewed; yet none focused on facilitators and barriers to self-care practices (Ashley-Binge & Cousins, 2020; Griffiths et al., 2019; Lizano, 2015; McFadden et al., 2015; Mor Barak et al., 2001). One review evaluated self-care interventions (Griffiths et al., 2019), whereas the remaining four systematic reviews focused on vicarious trauma (n = 1) and burnout (n = 3) among child welfare and human services professionals (Ashley-Binge & Cousins, 2020; Lizano, 2015; McFadden et al., 2015; Mor Barak et al., 2001).

Potential facilitators to self-care have included compassion satisfaction, whereas barriers to self-care have included burnout, secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue (Bloomquist et al., 2016). Bloomquist et al. (2016) wrote, “Compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout are potential consequences of these emotional demands and can lead to feelings of exhaustion and incompetence, turnover intention, and actual turnover from one’s organization” (p. 292). Compassion satisfaction is the positive feelings one experiences from doing one’s work well, whereas compassion fatigue is the negative response to caring for people who experience trauma and encompasses secondary traumatic stress and burnout (Bloomquist et al., 2016; Bride, 2007; Figley, 1995, 2002). Secondary traumatic stress can manifest as intrusive thoughts, disturbed sleep, avoidance of triggering people and activities, forgetfulness, and spillover from professional to personal lives (Bloomquist et al., 2016; Bride, 2007; Figley, 1995, 2002). Burnout is the sense of exhaustion, reduced personal feelings of accomplishment, and feeling depersonalized, typically as a result of experiencing highly stressful work environments (Bloomquist et al., 2016; Bride, 2007; Figley, 1995, 2002). Self-compassion is a positive and nurturing relationship, including feelings of warmth and care toward oneself (Miller, Lee, et al., 2019). Given the structural, under-resourced, and underpaid conditions social workers find themselves in, it is no wonder 20%–70% experience burnout (Bressi & Vaden, 2017; Pyles, 2020). Demographic factors and status (e.g.; marital status, education, income, and employment type) may also differentially facilitate or pose barriers to self-care practices; however, these factors to our knowledge, have not systematically been assessed.

Purpose

The purpose of this systematic review is to fill the gap in a critical understanding of the current state of empirical research on self-care practices in social work. Because empirical self-care research is a relatively new area of inquiry, the purpose of this review is to provide a broad overview of the state of existing research. This overview takes primacy over deep examination of study design or methodological rigor, which may be more appropriate for more established fields of study. The scope of empirical research as defined for this review is limited to published peer-reviewed journal articles reporting results from primary data collected on outcomes or topics directly assessing self-care practices as they relate to social work students, educators, and professionals. We identify empirical research to answer the overarching question, “What are the ecological facilitators and barriers to self-care practices in social work?” Facilitators are factors positively associated with or identified as promotive, whereas barriers are negatively associated or potential risks for engagement with self-care practices.

Materials and methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA, 2023) guidelines for systematic reviews. The scope of this systematic review is peer-reviewed quantitative and qualitative empirical research articles focusing on self-care in social work among adult social work practitioners and students. Empirical articles are defined here as those qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methodology peer-reviewed journal articles that collect primary data. Because self-care as an intervention is a relatively recent topic in scholarly literature, articles were not restricted by year. Final articles for inclusion were published in 2016–2022.

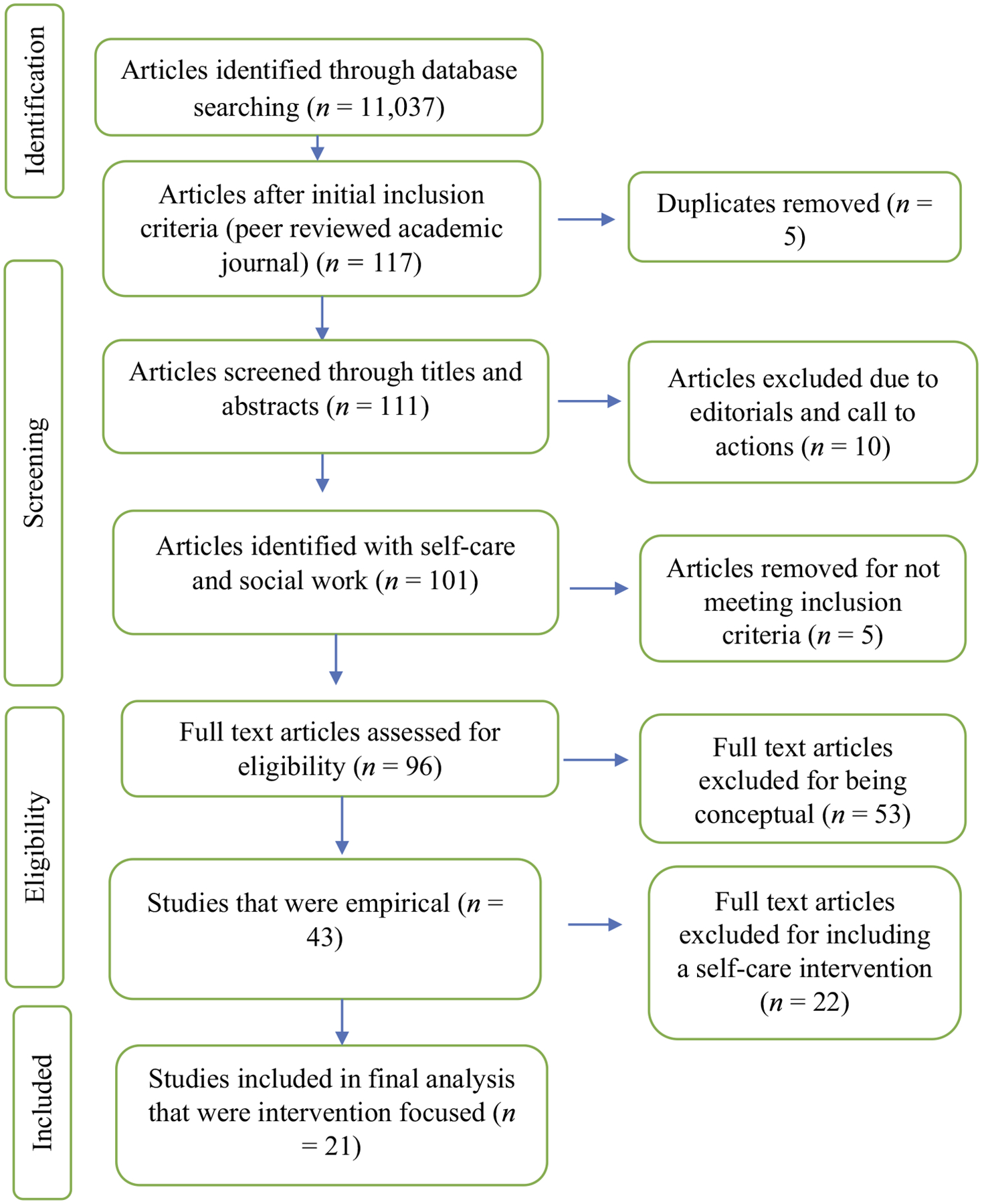

Only empirical peer-reviewed journal articles that collected primary data and included outcomes related to self-care social work students or professionals were included. The following search terms were used to identify peer-reviewed articles “social work” AND “self-care.” Two individuals independently searched a variety of social science and health-related databases for relevant articles, including EBSCO, Social Work Abstracts, Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Collection, SocINDEX with Full Text, ProQuest – Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, ProQuest – Sociological Abstracts, Springer Link, The Educational Resource Information Center (ERIC), Academic Search Complete, PubMed, JSTOR, APA PsycInfo, and APA PsycArticles. These 13 databases were searched from May 2022 to July 2022, and articles were entered into Excel spreadsheets. Manual searches of reference lists of relevant studies, based on eligibility criteria, were also conducted to locate additional published literature. Inclusion criteria delimited the search to articles that: (a) were empirical (collected primary data), (b) were peer reviewed journal articles, (c) addressed self-care and social work as primary outcomes, (d) had explicit attention to self-care in the findings and outcomes, and (d) did not evaluate or test a self-care intervention. Articles that included related factors, such as compassion fatigue, burnout, or secondary traumatic stress but did not include self-care as an explicit focus were included. Figure 1 provides a flow chart of the study selection process. All authors and three external reviewers independently reviewed all articles and ensured the inclusion criteria for being empirical were properly upheld.

Figure 1.

Empirical self-care study selection flow chart.

The aforementioned search strategies yielded a total of 11,037 articles (see Figure 1). After applying the inclusion criteria of being empirical and appearing in peer-reviewed academic journals, 117 articles were identified and screened for duplicates based on the titles and abstracts, resulting in 111 eligible articles. Two external reviewers excluded 10 articles for being editorials and calls to action (n = 101). In addition, five articles were excluded for not being related to self-care and the inclusion criteria (n = 96). The conceptual articles that did not include primary data collection were excluded (n = 53). The resultant 43 articles were divided into (a) empirical articles with outcomes with explicit attention to self-care in the findings and outcomes (n = 21) and (b) empirical articles that tested or focused on a self-care intervention (n = 22). Given an in-depth understanding of self-care interventions warrants a separate inquiry with distinct evaluation criteria, the scope of this systematic review was limited to the 21 empirical articles with outcomes on self-care. Because the articles focused on samples of practitioners, students, and educators whose professional lives and outcomes varied, results are organized based on focal samples (i.e., practitioners, students, educators).

Results

As indicated in Table 1, 21 articles related to empirical studies of self-care were identified in the systematic review process. Studies assessed self-care among samples of social work practitioners (n = 15), social work students (n = 3), and social work educators (n = 3). The majority of these studies were cross-sectional survey research (n = 17), with the remaining being pre/posttest (n = 1; Miller & Reddin Cassar, 2021), qualitative (n = 2; Diebold et al., 2018; Newcomb et al., 2017), or mixed-methods design (n = 1; Myers et al., 2022).

Table 1.

Preliminary ecological facilitators and barriers to self-care.

| Reference | Level | Barriers (−) and Facilitators (+) to Self-Care Practices | Type | Demographics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practitioners | ||||

| (1) Bloomquist et al. (2016) | Structural | — | Sample | Practitioners |

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 786 | |

| Individual | +Greater post-MSW experience | Setting | United States | |

| + Emotional, Spiritual, and Professional Self-care, Compassion Satisfaction, Positive Perceptions of Self-Care, Professional Quality of Life | ||||

| −Burnout, Compassion Fatigue, Psychological self-care | ||||

| (2) Cuartero and Campos-Vidal (2019) | Structural | — | Sample | Practitioners |

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 270 | |

| Individual | + Compassion Satisfaction; −Compassion Fatigue | Setting | Spain | |

| (3) Loeffler et al. (2018) | Structural | + Identifying as White, Female, Greater Financial Stability, For Profit Employers (vs. non-Profit), Working in Micro or Meso (in comparison with Macro level practice) | Size (n) | 348 |

| Relational | +Married | Setting | Rural United States | |

| Individual | +Older | Sample | Practitioners | |

| −Self-Reported Health, Greater Number of Hours Worked | ||||

| (4) Miller, Barnhart, et al. (2021) | Structural | +ldentifying as Heterosexual and Greater Financial Stability | Sample | Practitioners |

| Relational | +Married | Size (n) | 1,568 | |

| Individual | + Self-Reported Physical and Mental Health, and Engagement in Self-Care Predicted Lower COVID-19 Related Distress | Setting | SE United States | |

| (5) Miller, Donohue Dioh, et al. (2019) | Structural | + Greater Financial Stability and Belonging to Professional Organization | Sample | Practitioners |

| Relational | +Married | Size (n) | 623 | |

| Individual | + Greater Self-Reported Health | Setting | United States | |

| (6) Miller, Donohue Dioh, Larkin, et al. (2018) | Structural | + Identifying as White, Female, Greater Financial Stability, For Profit Employers (vs. non-Profit), Working in Micro or Meso (in comparison with Macro level practice) | Sample | Practitioners |

| Relational | +Married | Size (n) | 222 | |

| Individual | +Older-Self-Reported Health, Greater Number of Hours Worked, | Setting | SE United States | |

| (7) Miller, Grise-Owens, et al. (2020) | Structural | +ldentifying as White, Greater Financial Stability, and Licensed, Supervised others, Belonging to Professional Organization, Residing in Eastern South Central (−Western North Central Scored lowest), Working in Micro or Meso (in comparison with Macro level practice) | Sample | Practitioners |

| Relational | +Married | Size (n) | 2,934 | |

| Individual | +Older and Greater Experience, Educational Attainment, Self-Reported Health | Setting | United States | |

| (8) Miller, Lee, et al. (2019) | Structural | — | Sample | Practitioners |

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 831 | |

| Individual | +Older and Greater Experience, Belonging to Professional Organization, Self-Reported Health, Reported More Self-Compassion | Setting | Southeastern United States | |

| (9) Miller et al. (2017) | Structural | +Greater Financial Stability and Licensed | Sample | Practitioners |

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 138 | |

| Individual | +Greater Self-Reported Health | Setting | United States | |

| (10) Miller, Poklembova, et al. (2020) | Structural | −Greater Number of Hours Worked | Sample | Practitioners |

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 138 | |

| Individual | +Greater Self-Reported Health | Setting | Slovakia | |

| (11) Miller, Poklembova, et al. (2021) | Structural | +Greater Educational Attainment | Sample | Practitioners |

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 250 | |

| Individual | +Greater Self-Reported Health | Setting | Poland | |

| (12) Miller and Reddin Cassar (2021) | Structural | +Greater Financial Stability and Licensed | Sample | Practitioners |

| Relational | +Married | Size (n) | 2,460 | |

| Individual | +Greater Self-Reported Health and Working In-Person | Setting | Southeastern United States | |

| (13) Salloum et al. (2019) | Structural | — | Sample | Child Welfare Practitioners |

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 177 | |

| Individual | −Self-care practices, burnout, secondary trauma, and less years of experience associated with impaired mental health symptoms. | Setting | United States | |

| (14) Salloum et al. (2015) | Structural | — | Sample | Practitioners |

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 107 | |

| Individual | −Self-care practices predicted lower burnout and higher compassion satisfaction but not secondary trauma. | Setting | United States | |

| (15) Xu et al. (2019) | Structural | +Masters/Doctoral Students (−Bachelors) for Burnout and Compassion Satisfaction | Sample | Practitioners |

| −Self-Care Barriers risk for Burnout and Secondary Traumatic Stress but not Compassion Satisfaction | ||||

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 61 | |

| Individual | +Self-Care Practices inversely related to Burnout but not associated with Secondary Traumatic Stress or Compassion Satisfaction | Setting | United States | |

| Students | ||||

| (1) Diebold et al. (2018) | Structural | −Institutional Supports, Demands, and Expectations | Sample | Students |

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 209 | |

| Individual | +Holistic, Balance-Limited time and competing expectations and responsibilities | Setting | United States | |

| (2) Newcomb et al. (2017) | Structural | −Lack of Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills on Self-Care | Sample | Students |

| Relational | −Experiencing Adverse Childhood Experiences | Size (n) | 20 | |

| Individual | — | Setting | Australia | |

| (3) O’Neill et al. (2019) | Structural | — | Sample | Students |

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 90 | |

| Individual | +Daily (not weekly or monthly) Self-Care Practices Predicted Lower Academic Stress | Setting | United States | |

| Educators | ||||

| (1) Miller, Donohue Dioh, Larkin, et al. (2018) | Structural | +For Profit Employers (vs. non-Profit), Licensed | Sample | Educators |

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 127 | |

| Individual | — | Setting | United States | |

| (2) Miller, Grise-Owens, et al. (2018) | Structural | +Greater Academic Rank, Licensure Status, and Experience | Sample | Educators |

| Relational | — | Size (n) | 124 | |

| Individual | — | Setting | SE United States | |

| (3) Myers et al. (2022) | Structural | +Positive and Healthy Activities and Flexible Schedules, −Workload | Sample | Educators |

| Relational | +Supervision, Collegial Relationships, Family, Social Support | Size (n) | 81 | |

| −Role Overload Across Professional, Interpersonal, and Familial Relations | ||||

| Individual | — | Setting | United States |

+ indicates potential facilitating and − indicates barriers for self-care practices. — indicates no outcomes were present.

Self-care among social work practitioners

Fifteen studies focused on self-care practices among social work practitioners. Study designs were primarily cross-sectional exploratory (n = 15; Bloomquist et al., 2016; Cuartero & Campos-Vidal, 2019; Diebold et al., 2018; Loeffler et al., 2018; Miller & Reddin Cassar, 2021; Miller et al., 2017; Miller, Barnhart, et al., 2021; Miller, Donohue Dioh, Niu, et al., 2018; Miller, Donohue Dioh, et al., 2019; Miller, Grise-Owens, et al., 2020; Miller, Lee, et al., 2019; Miller, Poklembova, et al., 2020, 2021; Salloum et al., 2015, 2019). The focus now turns to summarizing key themes identified in research.

Self-care practices and socioeconomic, professional, and physical power and privilege

Drawing on data from cross-sectional survey research with social work practitioners (n = 270) in Spain, Cuartero and Campos-Vidal (2019) assessed the relationship of self-care practices as measured by the 10-item Self-Care Behaviors Scale for Clinical Psychologists (Guerra et al., 2008) as they related to satisfaction and compassion fatigue. This article identified support for engagement with self-care practices as negatively associated with compassion fatigue and positively associated with compassion satisfaction (Cuartero & Campos-Vidal, 2019). Miller, Lee, et al. (2019) assessed how self-compassion was associated with self-care practices among (n = 831) clinical social workers for a Southeastern state. Overall, social workers engaged in moderate self-care practices and self-compassion (Miller, Lee, et al., 2019). Miller, Lee, et al. (2019) identified that self-compassion was positively associated with engagement in self-care practices as measured by an 18-item self-care practices survey (SCPS; Lee et al., 2020), which assessed the frequency of engagement with personal and professional self-care practices (from 0 = never to 4 = very often). Results indicated greater engagement with self-care practices was associated with those who were older practitioners with more years of experience, who were members of professional organizations, who reported more self-compassion, and who had greater self-reported health (Miller, Lee, et al., 2019).

Xu et al. (2019) also assessed how self-care practices and barriers were associated with professional quality of life (i.e., as measured by compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout). Self-care barriers were measured through social workers’ perceptions of barriers related to workload, family, community, and social life (Bloomquist et al., 2016), and self-care. Xu et al. (2019) examined results from a random sample taken from a list of bachelor’s level graduates from a mid-Atlantic state (n = 61), a majority of who were female (92%) and White (54%). Xu et al. (2019) reported that (a) higher self-care behaviors and lower self-care barriers predicted lower levels of burnout; (b) higher self-care barriers predicted lower levels of secondary traumatic stress, yet self-care practices were not associated with secondary traumatic stress; and (c) neither self-care practices nor behaviors predicted compassion satisfaction. Bachelor-level social work students reported lower compassion satisfaction and burnout levels than master’s and doctoral degree holders. Those working in direct social work practice reported lower compassion satisfaction and higher burnout than social workers not working in direct practice.

Miller, Poklembova, et al. (2020) focused on assessing social workers’ self-care practices in Slovakia. Cross-sectional survey research among predominantly female (85%) Slovakian social workers (n = 138) focused on the amount of time social workers spent on self-care as measured by SCPS (Lee et al., 2020). Overall, engagement in self-care practices was low, with most participants only engaging in such practices sometimes (Miller, Poklembova, et al., 2020). These findings are congruent with other studies indicating a low level of engagement with self-care among social workers (Bloomquist et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2017). Results indicated an inverse relationship between self-care activities and hours worked; Miller, Poklembova, et al. (2020) reported that as average hours worked per week decreased, the time engaged in self-care practice increased. Moreover, self-reported health status meaningfully differentiated or moderated the relationships between self-care (Miller, Poklembova, et al., 2020).

Parallel to Miller, Poklembova, et al. (2020), Miller et al. (2017) replicated similar findings in the United States. Using cross-sectional survey research to assess self-care with the SCPS (Lee et al., 2020) among mostly female (90%) healthcare social workers in a Southeastern state (n = 138) among healthcare social work practitioners. Social workers reporting higher self-reported health, financial stability, and licensure status engaged in more self-care. Miller et al. (2017) findings suggest social work healthcare practitioners moderately engage in self-care practices.

Loeffler et al. (2018) replicated demographic facilitators of self-care practices among 348 rural social workers indicating that older, married, and female-identifying social workers who are White, female, experience greater financial stability, and work in for-profit agencies who engage in and in micro-or meso- social work practice engaged in more self-care practices than those working in macro practice. Working longer hours was a barrier to self-care and interestingly, those with poor health engaged in more self-care practices. Miller, Poklembova, et al. (2021) went on to conduct cross-sectional survey research evaluating self-care practices using the SCPS (Lee et al., 2020) among predominantly female (92%) social work practitioners in Poland (n = 250).

Parallel with other research (Miller et al., 2017; Miller, Poklembova, et al., 2020), self-care seemed to be a stand in or place holder for broader measures of social privilege among feminized professionals; social workers self-reporting higher health status, and those with higher academic degrees also reported more engagement in self-care practices (Miller, Poklembova, et al., 2021). Like other research, social workers only engaged in self-care practices “sometimes” (Miller et al., 2017; Miller, Poklembova, et al., 2020, 2021). Bloomquist et al. (2016) assessed the perceptions and practices related to self-care among social work practitioners (n = 786, of whom 88% were female) as they related to professional quality of professional life. Measures of professional quality of life included burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction. Bloomquist et al. (2016) reported participants valued self-care but rarely engaged in self-care practices. Positive perceptions of self-care were associated with lower secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and a higher number of post-MSW years in practice. Practitioners who engaged in more professional, emotional, and spiritual self-care practices reported lower burnout, whereas those engaging in more psychological self-care practices reported higher levels of burnout (Bloomquist et al., 2016). Professionals reported more compassion satisfaction when they had positive perceptions of self-care, practiced more emotional and professional self-care practices, and had a greater number of post-MSW professional experiences (Bloomquist et al., 2016). Overall, emotional, spiritual, and professional self-care activities were predictive of higher professional quality of life. All dimensions assessed were personal rather than relational or institutional. Miller, Barnhart, et al. (2021) focused on predictors of distress, which included self-care practices using the SCPS (Lee et al., 2020) among mental health social work practitioners in the southeastern United States during the COVID-19 global pandemic (n = 1,568). Miller, Barnhart, et al. (2021) found that 46% of practitioners reported mild or severe distress. Identifying as married, heterosexual, and those reporting higher financial stability, self-reported physical and mental health, and self-care practices reported lower pandemic-related distress.

Miller, Donohue Dioh, et al. (2019) assessed self-care practices using the SCPS (Lee et al., 2020) among social work practitioners (87% female and 83% White) employed in child welfare across 41 states (n = 623). Like other research, practitioners engaged in minimal self-care. Miller, Donohue Dioh, et al. (2019) showed those identifying as White, married, with higher education, more years of experience, licensure, supervision, self-reported health status, and financial stability, engaged in more self-care, along with those belonging to a professional organization. In contrast, working more hours per week was associated with lower reported self-care practices. Miller, Donohue Dioh, Niu, et al. (2018) also used the SCPS among 222 child welfare workers in the Southeast an identified being married, belonging to a professional organization, having greater financial security, and being healthier as those more likely to engage in self-care practices. Salloum et al. (2015) examined trauma informed self-care (TISC) among 104 social workers. They found that workers who engaged in higher TISC also reported higher compassion satisfaction and lower levels of burnout, although there was no relationship with secondary trauma. Salloum et al. (2019) examined predictors of mental health symptoms among 177 child welfare social workers and identified lower use of TISC self-care practices and years of experience, and greater burnout and secondary trauma to be associated with greater mental health symptoms.

Miller and Reddin Cassar’s (2021) study focused on assessing the impact COVID-19 had on social workers’ self-care practices in healthcare (n = 2,460) in one southeastern state using a pre – posttest design. Data from the Professional Self-Care Scale (Dorociak et al., 2017) were analyzed with a sample of predominantly White women (90% for both) were compared before and after COVID-19. Miller and Reddin Cassar’s (2021) results reported that social workers’ self-care practices decreased significantly from pre-COVID-19 to post-COVID-19. Participants who identified as married, financially stable, working in-person, and with higher self-reported health were engaged in more self-care practices at the post-COVID-19 time point.

Miller, Grise-Owens, et al. (2020) used the SCPS (Lee et al., 2020) to assess self-care practices in a cross-national U.S. sample of social work practitioners who were predominantly White (83%) and female (86%). Participants who were older, who had a greater number of years in practice, and who self-reported health reported greater engagement in self-care practices (Miller, Grise-Owens, et al., 2020). Moreover, self-care practices varied by U.S. region, namely those residing in the West North Central (i.e., Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North and South Dakota) scored the lowest, and those in the Eastern South Central region scored the highest (e.g., Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee) in self-care practices. People identifying as White, with greater educational attainment, who held professional membership, and who were licensed scored higher than social workers without licensure (Miller, Grise-Owens, et al., 2020). Social workers working in macro-level practice engaged in less self-care practices than those working in micro-level practice or mezzo-level practice (Miller, Grise-Owens, et al., 2020). Finally, those who were married and financially stable reported higher self-care practices (Miller, Grise-Owens, et al., 2020).

Self-care among social work students

Three studies examined self-care practices among social work students (n = 3; Diebold et al., 2018; Newcomb et al., 2017; O’Neill et al., 2019). First, O’Neill et al. (2019) studied the correlation between students’ stress levels and self-care practices. Students included in the study represented a sample (n = 90) of 82% female and 51% White (18% Latinx, 7% Black, 4% Native American) bachelor of social work and MSW students. Data were analyzed across both educational program years while incorporating the amount of time spent on self-care and students’ stress levels associated with academics. O’Neill et al. (2019) reported that daily self-care practices (i.e., as measured by single items for spiritual, physical, and social self-care) were associated with significantly lower self-care – regardless of the type of self-care reportedly practiced; practicing self-care on a weekly or monthly basis was not significantly associated with academic stress (O’Neill et al., 2019). As students moved through the program during the semester, their stress levels continued to decrease.

Second, Newcomb et al. (2017) assessed self-care abilities using qualitative interviews with social work students reporting histories of childhood adversity. As part of a larger mixed methods study (n = 20; 75% female), participants shared they received little education or training in understanding self-care to better prepare for their future professional work (Newcomb et al., 2017). Newcomb et al. reported that students felt their family upbringing and a lack of training played a role in their ability to self-care or inability to care for themselves. Students reported several self-care strategies: physical activities, reading, journaling, and breathing techniques. Qualitative findings reported that self-care programming and training are needed in social work education.

Third, Diebold et al. (2018) qualitatively analyzed survey data from two open-ended questions among MSW from a mid-Atlantic university (n = 209). Questions inquired about students’ perceptions of what self-care meant to them and their needs related to self-care. Diebold et al. (2018) qualitative themes clustered around health, time, activities, balance, and professionalism. Students tended to think of self-care holistically, encompassing mind and body; physical, spiritual, social, and emotional needs; and the ability to manage stress (Diebold et al., 2018). Limited time and bandwidth were frequently mentioned as barriers to self-care activities, which were considered those that rejuvenated them (Diebold et al., 2018). Balance was mentioned as something to strive for among multiple competing roles, expectations, and stressors, or being pulled in multiple directions (Diebold et al., 2018). Finally, self-care was expressed as important for self-awareness and high-quality professional care (Diebold et al., 2018). Diebold et al. (2018) reported students expressed the need for changes in program expectations, access to self-care tools, and teachers modeling healthy self-care practices.

Self-care among social work educators

Self-care practices among social work educators were focal to the remaining three studies (n = 3; Miller, Donohue Dioh, Larkin, et al., 2018; Miller, Grise-Owens, et al., 2018; Myers et al., 2022). First, Miller, Donohue Dioh, Larkin, et al. (2018) assessed self-care practices using the SCPS (Lee et al., 2020) among social work field placement professors (81% White, 85% female) in a southeastern state (n = 127). Miller, Donohue Dioh, Larkin, et al. (2018) reported that field practicum professors “sometimes” engage in self-care practices on professional and personal levels. Miller, Donohue Dioh, Larkin, et al. (2018) reported that licensed social workers and those working in for-profit (versus nonprofit) institutions engaged in significantly more self-care practices than their counterparts.

Second, Miller, Grise-Owens, et al. (2018) used cross-sectional survey research and the Professional Self-Care Scale (Dorociak et al., 2017) to examine self-care practices among social work professors (n = 124) in the southeastern United States. Participants were largely female (80%), heterosexual (94%), and White (87%; Miller, Grise-Owens, et al., 2018). Educators tended to engage in self-care on a frequent basis, with those holding a professional license (past or present) or who were at the associate or full professor levels (i.e., in comparison with Assistant level rank) reporting significantly higher scores. Life and professional support were the highest subdomain promoting higher self-care scores, and Miller, Grise-Owens, et al. (2018) reported those with longer field experience had higher self-care scores than those with less experience.

Myers et al. (2022) used a mixed methods design to assess self-care practices among social work professors (i.e., n = 81; 78% White, 81% female) institutional and personal risk and promotive factors for self-care. Study results focused on self-care activities, modeling self-care, educational support, barriers, and supports of self-care (Myers et al., 2022). Five dimensions of self-care management focused on psychological, physical, social, spiritual, and professional self-care activities. Myers et al. identified psychological, physical, and social variables as the top three activities that support self-care. Qualitative data suggested that professors model self-care to their students by implementing healthy boundaries, expectations of timelines, and providing self-care resources to students (Myers et al., 2022). Myers et al. indicated a lack of institutional support. For those who indicated support, this included supervisory support and collegial relationships with colleagues, along with events, flexible schedules, and available health activities (Myers et al., 2022). Barriers to engaging in self-care included high workloads, competing demands, and an overburden of personal and professional responsibilities; family and social support were facilitators for self-care (Myers et al., 2022).

Discussion

Overwhelmingly, social workers who reported greater sociostructural, economic, professional, and physical health privilege engaged in more self-care. Results from this systematic review indicate relatively few examination factors related to self-care in the last decade, indicating the relative recency of its empirical investigation. Among the 21 articles identified, 17 were based in the United States, and 11 were first authored by Miller. Most studies measured self-care using the SCPS (Lee et al., 2020), assessing the frequency of personal and professional self-care practices. Samples tended to reflect current demographics of MSW graduates, who are predominantly female (i.e., 90%) and often White (Salsberg et al., 2020). These demographics reflect broader patterns in social work. When examining ecological facilitators and barriers to self-care, all outcomes were assessed at the individual level, and most were individually focused. Studies focused on samples of practitioners (n = 15), students (n = 3), and educators (n = 3), and largely used cross-sectional research methods. The focus now turns to a summary of results according to structural, relational, and individual facilitators and barriers for self-care practices (see Table 1).

Structural and institutional facilitators and barriers to self-care practices

Among structural factors that affected self-care practices among practitioners, the following predicted greater self-care practices: (a) identifying as heterosexual, (b) identifying as White, (c) having greater financial stability, (d) being licensed, (e) belonging to a professional organization, (f) providing supervision, and (g) living in certain regions (see Table 1). For students seeking a Master’s or doctorate beyond the bachelor’s degree, lack of support and unrealistic demands and expectations were self-care barriers. For educators, being an associate professor (i.e., instead of assistant), working for a for-profit institution, and being licensed were self-care practice facilitators.

Relational facilitators and barriers to self-care practices

Although few relational factors were assessed (see Table 1), being married was associated with greater self-care practices among practitioners, and experiencing adverse childhood experiences was a barrier for child-welfare workers to engage in self-care practices. For educators, having positive and healthy events and activities, collegial relationships, supervision and mentorship, and family and social support were self-care facilitators. Role overloads across personal and professional spheres were barriers to self-care practices.

Individual-level facilitators and barriers to self-care practices

Although all factors were individually assessed, individually focused facilitators for self-care practices among practitioners tended to include (a) a greater post-MSW experience, (b) compassion satisfaction and positive perceptions of self-care, (c) working in-person, (d) positive self-reported physical and mental health, (e) higher educational attainment, (f) being older, and (g) having greater self-compassion and compassion satisfaction. Although healthier people tended to engage in more self-care practices, Loeffler et al. (2018) indicated that rural social workers reporting, poorer health engaged in greater self-care practices. Women and those with poorer health may be socialized to engage in more self-care and may require more self-care practices to sustain and survive their workplaces, in contrast with those with greater gender and health status privilege. In one study (i.e., Bloomquist et al., 2016), psychological self-care was negatively associated with burnout; it is possible social workers’ already high affective and emotional load may cause imbalances, and it is best to focus on other areas of self-care (e.g., spiritual, physical, social) to enhance balance across wellness dimensions. Self-care barriers for practitioners included burnout and compassion fatigue, lower COVID-19 distress, and working longer hours. Among students, engagement in daily engagement in self-care practices predicated lower academic stress. Weekly or monthly engagement levels were not significantly associated with lower academic stress. Students perceived the importance of an integrated approach to self-care, whereas role strain, responsibility overload, and time restrictions were barriers to self-care practices (Diebold et al., 2018). No individual-focused facilitators or barriers were reported among studies with samples of educators.

Limitations

The scope of this article is limited to social workers; though aspects may translate to other helping professions, the focus of this review was not comparative with nurses or other helping professions. Thus, comparative implications may not be gleaned from this review. This article was limited to published, peer-reviewed journal articles. Other sources of information outside this scope contains important information, including theses, books, and policy briefs, and new articles. Moreover, much research on the interrelationships between related factors (e.g., compassion fatigue, burnout) may be found and were not included in this review as its scope was limited to articles with self-care as an explicit focus and outcome. This article did not focus on self-care interventions. As such, information on these related factors and topics may not be gleaned from this article. Because of the nascent state of the literature, this review did not place primacy on methodological rigor, but rather, focused on identifying the state of empirical self-care research, or “what is known].”

Conclusion

What information can be gleaned from the extant state of empirical research on facilitators and barriers to self-care practices? The research is relatively preliminary and largely focused on demographic factors. People engaged in self-care practices are more likely to be healthy, work less, be White, and have higher socioeconomic professional status and privilege (e.g., Miller, Barnhart, et al., 2021; Miller, Donohue Dioh, et al., 2019) indicating current conceptualizations of self-care may not be accessible and contextually and culturally relevant to all social workers. No articles focused on structural or institutional factors – or downstream factors affecting self-care – despite role overload and situations of high stress, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout driving the need for self-care (Bride, 2007; Figley, 1995, 2002; Pyles, 2020). Investigated without the sociopolitical and historical context, these positive areas of growth have been used to blame people who are experiencing the consequences of centuries of sociostructural oppression for distress and psychosocial challenges.

O’Neill et al. (2019) remarked about the current approach to self-care and stated, “Ultimately, it is up to each person to develop his or her own evidence for what works” (p. 149). The framing of self-care placed sole responsibility on the individual rather than resetting the lens on how agencies, organizations, and educational institutions can support their students, faculty, and staff to engage and maintain self-care practices in response to burnout, secondary trauma, and work – life balance (Cuartero & Campos-Vidal, 2019). Among social workers, the number of hours worked consistently was inversely related to engagement with self-care practices. Such findings indicated that overall bandwidth, or accessibility to self-care as measured by time available to engage in self-care was the only significant predictor of self-care (Miller, Poklembova, et al., 2020). This positive association indicated that the higher social workers rated their self-reported health, the more engagement in self-care practices (Miller, Poklembova, et al., 2020). Given extant conceptualizations tend to center physical self-care, it is unsurprising that physical health and self-care are related.

Self-care and focalized conceptualizations of strengths without attendance to the context ignore and perpetuate a lack of awareness and consciousness of a sociopolitical affording access to these resources to those privileged by Western European thought (e.g., White, able-bodied, heterosexual, male; Yakushko & Blodgett, 2021). Given self-care is framed as individualistic personal responsibility (Pyles, 2020), it can do little to address the downstream stressful structural conditions that drive the secondary traumatic stress, compassion fatigue, burnout, job turnover, and structural inequalities in the first place (Bressi & Vaden, 2017; Griffiths et al., 2019). Too often, the altruism and care of social workers has been twisted into neoliberal and neocolonial efforts to extract as much work out of feminized and overburdened professionals as a tool of social control that abdicates collective, institutional, and sociostructural responsibilities to care for historically marginalized peoples (Yakushko & Blodgett, 2021). Self-care, like other attributes of positive psychology, such as resilience and posttraumatic growth, are positive constructs that have been manipulated for neoliberal gain at the expense of social workers and their clients (Yakushko & Blodgett, 2021). As Weinberg (2014) explained, social workers experience ethical dilemmas and conflicting roles in maintaining wellness and self-care while subordinating their needs and exceeding job expectations – all while upholding high-quality services in under neoliberal and insurance-driven contexts that place pressure to see more clients amid incessant demands, severe sociopolitical limitations, and high workloads. Under such conditions, self-care often becomes backgrounded (Weinberg, 2014).

Bloomquist et al. (2016) conceptualized and assessed self-care practices across physical (e.g., healthy eating, exercise, sleeping, and recreation), professional (e.g., chatting with colleagues, setting limits, taking breaks, protecting time, and gaining support), emotional (e.g., laugh, spend time with people they enjoy, play with children, affirm self, allow to cry, take social action, read, and watch movies), psychological (e.g., mindfulness, self-reflection, set limits, self-care plan, write in journal, and engage in personal therapy), and spiritual (e.g., meditate, pray, sing, spend time in nature, read inspirational books, spend time in spiritual community, and yoga) self-care domains (Bloomquist et al., 2016). In all the examples, the impetus is on the social worker to find the time to engage in leisure activities. In almost all the professional examples, the social worker is required to increase their time spent at work.

While serving an important component of striving for sustainability as social workers, like other gendered forms of self-improvement, self-care has become a burgeoning industry and concept within social work and is framed in individualistic terms that place sole responsibility on the overburdened workers (Pyles, 2020; Yakushko & Blodgett, 2021). The sole systematic review on the topic focused on self-care interventions, which included a mere four studies, all of which were mindfulness interventions (Griffiths et al., 2019). Although mindfulness may help with clinical stress and managing distress, it does little to address structural injustices. It has been described as a billion dollar industry of neoliberal “McMindfulness” that places personal responsibility at the height of self-care and wellness; it promotes hyper-consumerism, personal and client surveillance, regulation and control, and unsustainable productively that dehumanizes workers and clients who work in under-resourced conditions amid ever-increasing business, corporate, and institutional settings (Doran, 2018). Though these self-care practices may be helpful, time remains finite, and no assessment of competing demands and role overload that may prevent these practices from occurring were identified. For example, given the number of hours worked is associated with the ability to complete self-care practices, an employer may consider decreasing the workload of a social worker and, thus, allow time for these personal and professional self-care practices.

The COVID-19 global pandemic has clarified that structural sexism pervades the underpaid and undervalued feminized professions, such as social work (Dhatt & Keeling, 2021; Gutierrez-Rodriguez, 2014). Outsourcing domestic reproductive, caregiving, emotional, and affective labor is a fundamental attribution of settler colonialism, capitalism, and the neo-liberal context (Gutierrez-Rodriguez, 2014). Both function to build and care for society with the littlest resources and support possible and rely on the underpayment and unpaid labor of women caregiving, at home and in feminized professions (Dhatt & Keeling, 2021; Gutierrez-Rodriguez, 2014). Extant self-care approaches absent the sociopolitical context may ultimately ignore factors driving burnout and place self-care as a sole responsibility on practitioners to take personal responsibility for their own fatigue and competing demands at work (Cuartero & Campos-Vidal, 2019). Cuartero and Campos-Vidal (2019) repeatedly discussed how social worker self-care practices are important for the “improvement of service performance and client satisfaction” (p. 286). The application of business language such as “service performance” to the field of social work has been widely critiqued as perpetuating neoliberal social work (Bressi & Vaden, 2017; Lee & Miller, 2013; Pyles, 2020; Stuart, 2021). The imperative for social workers to combat their own compassion fatigue as a way to improve their “performance” at work instead of for their personal health and wellness dehumanizes and objectifies social workers as an instrument or mechanism (Stuart, 2021; Weinberg, 2014) instead, as indicated by social work value, of as a human being with inherent dignity and worth.

Moreover, extant self-care assessments construct a binary between the personal and professional selves while reflecting and replicating Western Europe and White middle-class values while treating them as universal practices (Yakushko & Blodgett, 2021). Typical self-care practices include socioeconomic and status privilege (e.g., taking vacations, and taking time for yourself [e.g., Bloomquist et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2020]). Such strategies assume a certain sociopolitical value orientation and are not accessible to people without disposable incomes or like a majority of social workers overburdened in underpaid feminized professions and juggling incessant home-life demands amid a context of structural sexism (Dhatt & Keeling, 2021; Gutierrez-Rodriguez, 2014; Homan, 2019; Pyles, 2020). More relational and inclusive frameworks redefine the self to a relational model instead of creating rigid boundaries between professional or personal spheres (Bressi & Vaden, 2017). From this intersubjective and dialogic self-care perspective, activities may offer professional and personal transformation opportunities as the client and social worker move through uncertainties (Bressi & Vaden, 2017). As such, rather than a focalized aim to reduce distress and anxiety, people learn to tolerate the ambiguity that necessarily precludes wisdom, transcendence, and post-transformative growth (Bressi & Vaden, 2017).

Hillock and Profitt (2007) recommend critical and structural self-care discourses and approaches that not only focus on sustaining the self but also on transformation systems of domination and oppression that drive distress. Accordingly, culturally relevant meaning making self-care activities can facilitate personal and collective connection and change the structural inequalities that drive distress among social workers and clients (Bressi & Vaden, 2017). Hillock and Proffit identified congruent self-care practices, including (a) fostering critical thinking, (b) being reflexive about one’s positionality and how it affects bias, (c) becoming aware and dismantling internalized oppression, (d) understanding and preventing complicity in perpetuating structural disadvantage, (e) acknowledging a tendency toward Western European epistemology for social work models, (f) developing more inclusive frameworks, (g) creating safe spaces for critical dialogue and reflection, and (h) collaborative and collective growth and learning opportunities.

Funding

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health - U.S. [R01AA028201].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ashley-Binge S, & Cousins C (2020). Individual and organisational practices addressing social workers’ experiences of vicarious trauma. Practice, 32(3), 191–207. 10.1080/09503153.2019.1620201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomquist KR, Wood L, Friedmeyer-Trainor K, & Kim H (2016). Self-care and professional quality of life: Predictive factors among MSW practitioners. Advances in Social Work, 16(2), 292–311. 10.18060/18760 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bressi SK, & Vaden ER (2017). Reconsidering self-care. Clinical Social Work Journal, 45(1), 33–38. 10.1007/s10615-016-0575-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bride BE (2007). Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work, 52 (1), 63–70. 10.1093/sw/52.1.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuartero ME, & Campos-Vidal JF (2019). Self-care behaviours and their relationship with satisfaction and compassion fatigue levels among social workers. Social Work in Health Care, 58 (3), 274–290. 10.1080/00981389.2018.1558164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhatt R, & Keeling A (2021). Delivered by women, led by men: The future of global health leadership. Leader to Leader, 2021(100), 43–47. 10.1002/ltl.20568 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diebold J, Kim W, & Elze D (2018). Perceptions of self-care among MSW students: Implications for social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(4), 657–667. 10.1080/10437797.2018.1486255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doran P (2018). McMindfulness: Buddhism as sold to you by neoliberals. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/mcmindfulness-buddhism-as-sold-to-you-by-neoliberals-88338 [Google Scholar]

- Dorociak KE, Rupert PA, Bryant FB, & Zahniser E (2017). Development of a self-care assessment for psychologists. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(3), 325–334. 10.1037/cou0000206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figley CR (Ed.). (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Figley CR (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self-care. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(11), 1433–1441. 10.1002/jclp.10090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths A, Royse D, Murphy A, & Starks S (2019). Self-care practice in social work education: A systematic review of interventions. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(1), 10.1080/10437797.2018.1491358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra C, Rodríguez K, Morales G, & Betta R (2008). Preliminary validation of the self-care behaviors scale for clinical psychologists. Psykhe (Santiago), 17(2), 67–68. 10.4067/S0718-22282008000200006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Rodriguez E (2014). Domestic work–affective labor: On feminization and the coloniality of labor. Women’s Studies International Forum, 46, 45–53. 10.1016/j.wsif.2014.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J (2022). Do wages fall when women enter an occupation? Labour Economics, 74, 0927–5371, 102102. 10.1016/j.labeco.2021.102102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hillock S, & Profitt NJ (2007). Developing a practice and andragogy of resistance: Structural praxis inside and outside the classroom. Revue Canadienne de Service Social [Canadian Social Work Review], 39–54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41669859 [Google Scholar]

- Homan P (2019). Structural sexism and health in the United States: A new perspective on health inequality and the gender system. American Sociological Review, 84(3), 486–516. 10.1177/0003122419848723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ, & Miller SE (2013). A self-care framework for social workers: Building a strong foundation for practice. Families in Society, 94(2), 96–103. 10.1606/1044-3894.4289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ, Miller SE, & Bride BE (2020). Development and initial validation of the self-care practices scale. Social Work, 65(1), 21–28. 10.1093/sw/swz045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizano LE (2015). Examining the impact of job burnout on the health and well-being of human service workers: A systematic review and synthesis. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 39(3), 167–181. 10.1080/23303131.2015.1014122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler D, Miller JJ, & Pachner TM (2018). Self-care among social workers employed in rural settings: A cross-sectional investigation. Contemporary Rural Social Work Journal, 10(1), 1–20. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/csw_facpub/13 [Google Scholar]

- McFadden P, Campbell A, & Taylor B (2015). Resilience and burnout in child protection social work: Individual and organisational themes from a systematic literature review. British Journal of Social Work, 45(5), 1546–1563. 10.1093/bjsw/bct210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Barnhart S, Robinson TD, Pryor MD, & Arnett KD (2021). Assuaging COVID-19 peritraumatic distress among mental health clinicians: The potential of self-care. Clinical Social Work Journal, 49(4), 505–514. 10.1007/s10615-021-00815-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Donohue Dioh J, Larkin S, Niu C, & Womack R (2018). Exploring the self-care practice of practicum supervisors: Implications for field education. The Field Educator, 8(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/2237495364 [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Donohue Dioh J, Niu C, Grise-Owens E, & Poklembova Z (2019). Examining the self-care practices of child welfare workers: A national perspective. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 240–245. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.02.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Donohue Dioh J, Niu C, & Shalash N (2018). Exploring the self-care practices of child welfare workers: A research brief. Children and Youth Services Review, 84, 137–142. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.11.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Grise-Owens E, Owens L, Shalash N, & Bode M (2020). Self-care practices of self-identified social workers: Findings from a national study. Social Work, 65(1), 55–63. 10.1093/sw/swz046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Grise-Owens E, & Shalash N (2018). Investigating the self-care practices of social work faculty: An exploratory study. Social Work Education, 37(8), 1044–1059. 10.1080/02615479.2018.1470618 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Lee J, Niu C, Grise-Owens E, & Bode M (2019). Self-compassion as a predictor of self-care: A study of social work clinicians. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47(4), 321–331. 10.1007/s10615-019-00710-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Lianekhammy J, Pope N, Lee J, & Grise-Owens E (2017). Self-care among healthcare social workers: An exploratory study. Social Work in Health Care, 56(10), 865–883. 10.1080/00981389.2017.1371100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Poklembova Z, Grise-Owens E, & Bowman A (2020). Exploring the self-care practice of social workers in Slovakia: How do they fare? International Social Work, 63(1), 30–41. 10.1177/0020872818773150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Poklembova Z, Podkowińska M, Grise-Owens E, Balogová B, & Maria Pachner T (2021). Exploring the self-care practices of social workers in Poland. European Journal of Social Work, 24(1), 84–93. 10.1080/13691457.2019.1653828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, & Reddin Cassar J (2021). Self-care among healthcare social workers: The impact of COVID-19. Social Work in Health Care, 60(1), 30–48. 10.1080/00981389.2021.1885560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor Barak ME, Nissly JA, & Levin A (2001). Antecedents to retention and turnover among child welfare, social work, and other human service employees: What can we learn from past research? A review and metanalysis. Social Service Review, 75(4), 625–661. 10.1086/323166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myers K, Martin E, & Brickman K (2022). Protecting others from ourselves: Self-care in social work educators. Social Work Education, 41(4), 577–586. 10.1080/02615479.2020.1861243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers. (2021). Read the Code of Ethics. https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

- Newcomb M, Burton J, & Edwards N (2017). Childhood adversity and self-care education for undergraduate social work and human services students. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 37(4), 337–352. 10.1080/08841233.2017.1345821 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill M, Yoder Slater G, & Batt D (2019). Social work student self-care and academic stress. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(1), 141–152. 10.1080/10437797.2018.1491359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA. (2023). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis. http://prisma-statement.org/

- Pyles L (2020). Healing justice, transformative justice, and holistic self-care for social workers. Social Work, 65(2), 178–187. 10.1093/sw/swaa013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A, Choi MJ, & Stover CS (2019). Exploratory study on the role of trauma informed self-care on child welfare workers’ mental health. Children and Youth Services Review, 101, 299–306. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.04.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum A, Kondrat DC, Johnco C, & Olson KR (2015). The role of self-care on compassion satisfaction, burnout and secondary trauma among child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 49, 54–61. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.12.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salsberg E, Quigley L, Richwine C, Sliwa S, Acquaviva K, & Wyche K (2020). The social work profession: Findings from three years of surveys of new social workers. A Report to the Council on Social Work Education and the NASW. Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity, The George Washington University. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart H (2021). Professional inefficacy is the exact opposite of the passionate social worker: Discursive analysis of neoliberalism within the writing on self-care in social work. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 32(1), 1–16. 10.1080/10428232.2020.1790715 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg M (2014). The ideological dilemma of subordination of self versus self-care: Identity construction of the ethical social worker. Discourse & Society, 25(1), 84–99. 10.1177/0957926513508855 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Gender and Health. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/gender-and-health

- Xu Y, Harmon Darrow C, & Frey JJ (2019). Rethinking professional quality of life for social workers: Inclusion of ecological self-care barriers. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 29(1), 11–25. 10.1080/10911359.2018.1452814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yakushko O, & Blodgett E (2021). Negative reflections about positive psychology: On constraining the field to a focus on happiness and personal achievement. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 61 (1), 104–131. 10.1177/0022167818794551 [DOI] [Google Scholar]