Abstract

Liver transplantation (LT) is the second most common solid organ transplantation worldwide. LT is considered the best and most definitive therapeutic option for patients with decompensated chronic liver disease (CLD), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), acute liver failure (ALF), and acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). The etiology of CLD shows wide geographical variation, with viral hepatitis being the major etiology in the east and alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) in the west. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is on an increasing trend and is expected to be the most common etiology on a global scale. Since the first successful LT, there have been radical changes in the indications for LT. In many circumstances, not just the liver disease itself but factors such as extra-hepatic organ dysfunction or failures necessitate LT. ACLF is a dynamic syndrome that has extremely high short-term mortality. Currently, there is no single approved therapy for ACLF, and LT seems to be the only feasible therapeutic option for selected patients at high risk of mortality. Early identification of ACLF, stratification of patients according to disease severity, aggressive organ support, and etiology-specific treatment approaches have a significant impact on post-transplant outcomes. This review briefly describes the indications, timing, and referral practices for LT in patients with CLD and ACLF.

Keywords: liver transplant, CLD, ACLF, timing for LT, LT referral

Graphical abstract

Liver transplantation in chronic liver disease- indication and timings.

Highlights

-

•

liver transplant success for cirrhosis and ACLF increased over time with improved quality of life.

-

•

LT domain has expanded with consideration of MELD exceptions, special indication, and better critical care hepatology.

-

•

Prioritisation for urgent, emergent conditions and optimization of sick patients including ACLF during the transplant window, are unmet needs.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) accounts for approximately 2 million deaths per year worldwide.1 Liver transplantation (LT) is considered the best therapeutic option for all types of liver failure and liver cancer, as 1-year post-transplant survival exceeds 90% for chronic liver disease and 80% for acute-on-chronic liver failure(ACLF).2, 3, 4 Over the past five decades, the indications for LT have progressively evolved. Decompensated cirrhosis is the most common indication for LT in Europe and the United States of America (USA), accounting for more than half in Europe and 3/4th in the USA.5,6 ACLF as an indication for LT is gaining steady momentum. Currently, 19.2% of the transplanted patients in Europe and approximately 2% of the patients listed for LT in the United States have ACLF.4,7 The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score is the universal organ allocation system for LT.8 As patients with a MELD score ≤14 have a higher actuarial probability of 1-year survival than that after LT, those with a MELD score ≥15 are considered for LT listing.9,10 Although ACLF as an indication for LT is growing, the traditional allocation with the MELD score has limitations for patients with ACLF as it does not reflect their short-term mortality. Newer scores for ACLF (EASL CLIF-C ACLF, APASL AARC, and NACSELD ACLF score) seem to outperform MELD in predicting short-term mortality.11, 12, 13 This review outlines LT indications, timing, and referral practices in adult patients with CLD and ACLF. LT for acute liver failure (ALF), nonliver failure etiologies, and hepatobiliary malignancies are not discussed in this review.

INDICATIONS FOR LIVER TRANSPLANT IN CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE PATIENTS

Cirrhosis and its ensuing complications like hepatic encephalopathy (HE), refractory ascites, hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), HCC, variceal bleeding, porto-pulmonary hypertension (POPH), and hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) are the most common indications for LT. The indications for LT in patients with CLD are presented in Table 1. Recent data from the United States shows that the most common etiology in adult LT recipients is an alcoholic liver disease (35.2%), followed by other/unknown etiologies primarily representing patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (34.6%), and HCC (12.6%). Other etiologies of LT were cholestatic disease (8.3%), hepatitis C virus (6.7%), and ALF (2.5%).6 In the European data collected between 2002 and 2016, cirrhosis (50%) was the most frequent indication for LT (viral infection 22%, and alcohol-related 19%). Cirrhosis was followed by HCC (15%), cholestatic disease (10%), and ALF (9.1%).5 Most countries/regions have organ allocation policies based on the MELD score, which has undergone significant revisions over time to address the observed disparities in organ allocation.

Table 1.

The Indications for LT in Patients With Liver Disease.

| Complications of portal hypertension | Refractory ascites |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | |

| Refractory hepatic hydrothorax | |

| Spontaneous bacterial pleuritis | |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | |

| Refractory or recurrent variceal bleeding | |

| Porto pulmonary hypertension | |

| Hepatopulmonary syndrome | |

| Liver failure (Synthetic dysfunction) | Jaundice |

| Coagulopathy | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | |

| Acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) | |

| End stage liver disease (ESLD) | |

| Indications in cholestatic liver disease | Recurrent bacterial infection/cholangitis |

| Significant impairment of quality of life | |

| (i.e. intractable pruritus, repeated | |

| hospitalizations) | |

| Severe fatigue | |

| Secondary biliary cirrhosis | |

| Hepatobiliary malignancies | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Hilar and intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma | |

| Haemangioendothelioma | |

| Colorectal liver metastasis | |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | |

| Hepatoblastoma | |

| Metabolic liver diseases | Wilson disease |

| Hemochromatosis | |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | |

| Primary hyperoxaluria | |

| Familial hyperlipidemia | |

| Miscellaneous liver diseases | Budd–Chiari syndrome |

| Veno-occlusive disease | |

| NCPF with parenchymal extinction | |

| Nodular regenerative hyperplasia | |

| Familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy | |

| Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia | |

| Polycystic liver disease | |

| Congenital hepatic fibrosis |

ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; ESLD, end-stage liver disease; LT, liver transplantation.

Although the MELD score is a widely used tool for organ allocation, it does not accurately reflect the risk of death in some groups of patients (i.e. refractory ascites, HE, variceal bleeding) and thus may underserve these patients. For this reason, the addition of serum sodium to the MELD equation (MELD-Na) and other prioritization rules (MELD exceptions) were implemented.14,15 MELD exceptions [Table 2] are used to reflect patients' medical urgency, which is not represented by the MELD score alone, to prioritize patients for organ allocation according to their mortality risk. There are several MELD exceptions, including complications such as portal hypertension, HCC, and primary hyperoxaluria. Over time, audits of organ allocation systems based on the MELD score have shown that some groups of patients are particularly disadvantaged (Figure 1). To further refine the disparity in organ allocation, MELD 3.0 was recently developed. MELD 3.0 has been proposed as an improved MELD model considering gender, serum albumin, and the upper bound for creatinine fixed at 3 mg/dL. This model addresses gender inequity in the liver transplant waitlist as it credits an extra 1.3 points to women.16 Some of the common MELD-exception scenarios (Table 2) are discussed below.

Table 2.

MELD Exception Indication for LT.

| Exceptions to MELD score |

|---|

| Manifestations of cirrhosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Miscellaneous liver diseases |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Malignancy |

|

|

|

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LT, liver transplantation; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

Figure 1.

MELD score modification over time.

Refractory Ascites

Refractory ascites occur in 5–10% of patients with portal hypertension and are associated with more than 50% mortality within a year.17 Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) and intra-abdominal devices have been recently proposed for these patients; however, LT remains superior in terms of survival, quality of life (QoL), and cost.18, 19, 20 Therefore, most allocation systems have accepted refractory ascites as a MELD exception.

Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is the most common infection in patients with cirrhosis, and poor survival was observed in one-third of patients from a recent prospective multi-center study.21 It is known that patients with SBP have a high mortality rate between 53.9% and 78% over the next 12 months.22,23 Thus, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommends that patients who survive SBP should be considered for LT.20

Acute Kidney Injury or Hepatorenal Syndrome

In cirrhotic patients, an absolute increase of serum creatinine by > 0.3 mg/dL from baseline in 48 h or a rise of >50% from baseline within 3 months confers the diagnosis of AKI based on the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO).24 Every attempt should be made to determine the type and etiology of AKI in patients with cirrhosis, including pre-renal, HRS, intrinsic causes, particularly acute tubular necrosis, and post-renal causes.25 HRS-AKI is defined by the International Club of Ascites criteria as no improvement of creatinine levels to diuretic withdrawal and albumin infusion of 1 g/kg for 2 days.26 Vasoconstrictors, particularly terlipressin and albumin 20–40 g/day, are recommended in patients with HRS-AKI with intensive monitoring and response evaluation.20,27 LT is the best therapeutic option for patients with HRS-AKI, regardless of their response to therapy.28 In addition, simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation (SLK) is considered in patients with sustained AKI, defined as either the need for sustained renal replacement therapy for at least 4 weeks or an estimated glomerular filtration rate of <25 mL/min persistently for at least 6 weeks.28

THE UNMET NEED AREAS FOR MELD EXCEPTION

Hepatic Encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) has been associated with increased mortality, independent of the MELD score.29 Refractory and recurrent HE is an indication for LT; however, most allocation systems do not recommend it as a MELD exception because of a lack of objective assessment methods for HE severity [Table 2].30,31

Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia affects the physical disability, QoL, morbidity, and mortality in patients with CLD. The prevalence of sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis was 55.4%, with higher prevalence rates in patients with advanced cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class B or C) compared to those with Child-Pugh class A.32 Another meta-analysis showed that sarcopenia prevalence was higher in men than in women.33 Diagnostic criteria are based on muscle mass, muscle strength, and function according to the cut-off values from the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP),34 Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS),35 and the Japan Society of Hepatology (JSH).36 The gold standard for measuring muscle mass is computed tomography (CT) of the L3 vertebral-level abdominal muscle, which is calculated using the skeletal muscle index (SMI). Sarcopenia adds to the MELD score for a better prediction of 3-month and 1-year mortality, especially in patients with low MELD scores and refractory ascites.37 In an external validation study, the MELD-Sarcopenia (MELD score + 10.35 × sarcopenia) added value in patients with a MELD score ≤15 for predicting survival outcome as well as the transplant-related complications.38 Hand grip strength (HGS), which is easier to use in clinical practice and perform better than MELD-Sarcopenia.39 Recently, the Liver Frailty Index (LFI), comprising of HGS, balance, and chairs stand in addition to MELD-Na had a better predictability for wait list mortality.40

The association of sarcopenia with post-LT mortality is getting more recognition by clinicians in decision-making. A comprehensive assessment of this relationship was highlighted.27 The 1-year and 5-year post-LT survival were 59% and 54% among sarcopenic compared to 94% and 80%, respectively, in their nonsarcopenic counterparts (P < 0.001). The presence of pretransplant sarcopenia, increases the risk of posttransplant mortality by a factor of 4.8, elucidating the need of this entity in LT referral and prioritization.41

In addition to sarcopenia, evaluating the frailty is a must for every transplant candidate.42 Even after a wealth of data proving the undeniable role of sarcopenia on mortality in patients with cirrhosis, current transplant practices do not allow for earlier listing or any MELD exception points in these patients’ mortality.

Hepatic Hydrothorax

Hepatic hydrothorax (HH) is the pleural effusion occurring in the context of cirrhosis with portal hypertension and is characterized by its transudative profile (serum-pleural fluid albumin gradient >1.1 g/dL). The mainstay of treatment is salt restriction, diuretic therapy, and on-demand thoracocentesis.20,27 Refractory or recurrent HH should be treated by TIPS or LT.43,44 HH and a mean MELD score of 14 had far higher actuarial 90-day mortality (26%) than that predicted by the MELD score (11%).45 Therefore, LT should be considered in the MELD exception for patients with recurrent or refractory HH.46

Porto-Pulmonary Hypertension

Pulmonary hypertension developing in the context of portal hypertension is called POPH and is graded by the mean pulmonary artery pressure as mild (25–34 mmHg), moderate (35–44 mmHg), and severe (≥45 mmHg).47 Patients with mild and moderate POPH are considered for MELD exception points as any further progression in pulmonary pressure portends poor survival post-LT, and LT is contraindicated in severe POPH.48 A narrow window exists for this group of patients, requiring early detection and transplant.

Hepatopulmonary Syndrome

HPS is associated with a two-fold increased risk of mortality compared to those patients without HPS after transplant. Additionally, patients with severe HPS have a significantly poor functional status and impaired QoL in the absence of LT.49 The severity of HPS is determined by the degree of hypoxemia; partial arterial oxygen tension (PaO2) less than 60 mmHg is considered a MELD exception. Patients with a PaO2 less than 45–50 mm Hg have been associated with an increased risk of post-transplant mortality and morbidity.47 These patients should be considered for liver transplants early in the course of the disease and be promptly listed. The MELD exception and additional points in follow-up have been there for HPS.

Special Consideration in Patients With Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis and Secondary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) or secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC) may have recurrent bacterial infection or cholangitis (two or more times within a year) that is not responsive to medical, radiologic, or endoscopic interventions. Although many disease-specific prognostic models, such as the Mayo risk score, have been developed for these patients. LT consideration in these patients needs a different approach than that for other CLDs. Recurrent bacterial infection or cholangitis, persistent and/or intractable pruritus, which is not controlled by medications and other therapeutic interventions, is associated with significantly decreased QoL. Intractable pruritus is a MELD exception for LT in Europe but not in the United States, as there is inadequate evidence of increased pretransplant mortality.50

TIMING AND/OR REFERRAL FOR LIVER TRANSPLANTATION IN LIVING DONOR LIVER TRANSPLANTATION (LDLT) AND DECEASED DONOR LIVER TRANSPLANT (DDLT) SCENARIO

Minimal Listing Criteria

While managing patients with CLD, it is crucial to identify those at risk of deterioration and death related to liver disease complications who will benefit from timely LT. Patients with an expected survival of less than a year without LT or an unacceptable QoL due to liver disease should be selected for LT (Table 3). A MELD score of 15 or higher indicates that the patient has advanced liver disease and requires an LT. Patients with absolute contraindications for an LT do not qualify for listing even after meeting the minimal MELD criteria (Table 4). The list of contraindications is exhaustive but generally includes active uncontrolled infection, active substance abuse, and certain types of cancer. Compliance with medical therapy and adequate social support are other important aspects that should be adequately explored and intervened with if needed.51, 52, 53, 54

Table 3.

Minimal Listing Criteria for LT.

| Minimal listing criteria for LT |

|---|

| Broad concept |

|

|

|

| Listing criteria |

| Child-Pugh score of ≥7, i.e. class B or C |

| Presence of portal hypertensive gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Single episode of SBP, irrespective of their Child-Pugh score |

| Ascites-refractory |

| Liver cancer-BCLC A/B |

| Synthetic dysfunction |

| Also included other disease specific aetiologies |

BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; LT, liver transplantation; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Table 4.

Liver Decompensating Events in Cirrhosis and Survival.

| Event | Median survival |

|---|---|

| No decompensation | 8.9 years |

| Any decompensation | 1.6–2 years |

| SBP | <1 year |

| Refractory ascites | 6 months |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 1 year |

| HRS | Weeks to months |

HRS, hepatorenal syndrome; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Risk During Liver Transplant Waiting

According to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), as of August 2022, there are 17,306 patients on the waiting list for LT in the United States. In contrast, only 10,970 LT could be performed in 2021, leaving many patients waiting for an extended period, with the median waiting time being 1.8 years.55 This underpins the fact that there is a huge unmet need and organ shortage. Patients on the LT waitlist thus face not just morbidity but significant mortality, which can be as high as 52% in patients with MELD 30 or higher.56

The waiting time for LT can cause a significant psychological and financial burden for patients and their families. Patients on the waiting list often experience anxiety, depression, and uncertainty about their future. The waiting period is financially challenging, as patients may face health care costs, lost income, and other expenses.57,58 Therefore, improving donor availability and reducing waiting times are critical to improving patient outcomes.

Need, Urgency and Practices for Liver Transplant in Chronic Liver Disease

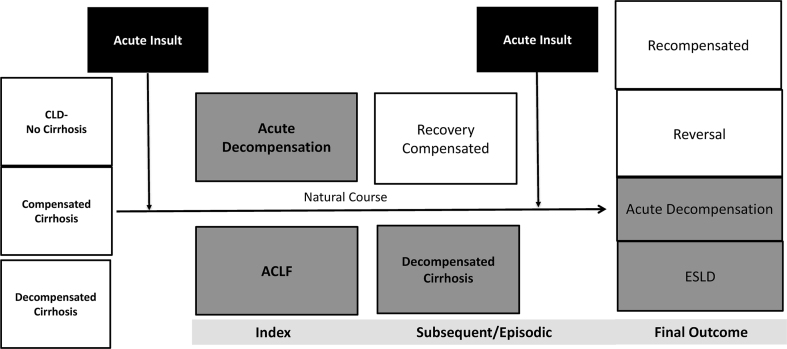

The timing of the referral of CLD patients to the liver transplant units is crucial. Efforts should be made early i.e. as soon as they are eligible according to the listing criteria. This gives the transplant team a timeframe for the required pretransplant evaluation. Additionally, patients would have time to review all options. Late referral may increase posttransplant hospital stay and mortality due to unoptimized pretransplant status (e.g. frailty, sarcopenia, malnutrition).59,60 The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommends referral to transplant centers at the first decompensation (e.g. ascites, HE, or variceal hemorrhage) or MELD score ≥ 15.61 The EASL recommends that a patient be referred to a transplant center when major complications of cirrhosis, such as variceal hemorrhage, ascites, HRS, and HE, occur (Figure 2).62

Figure 2.

Natural course of CLD and ACLF (Shaded area suggest the need for liver transplant). ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; CLD, chronic liver disease; ESLD, end stage liver disease.

However, the AASLD guidelines in 2005 and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF) recommendations in 2018 suggest that all patients with cirrhosis without cholestatic liver disease should be referred to an LT center if the MELD score ≥10 and/or Child-Pugh score ≥ 7.63,64 Patients with primary biliary cholangitis with portal hypertension-driven complications or refractory pruritus should be referred for LT evaluation.62 Patients with moderate-to-severe HPS need referral and expedited for LT. Patients who have been diagnosed with mild or moderate POPH should be discussed with a liver transplant unit regarding their suitability for LT. HIV-positive patients with cirrhosis should be referred early for transplant assessment if their CD4 count is more than 100–150/mm3, the antiviral regimen is stable, and they have no AIDS-defining illness.65 Patients with absolute contraindications to LT should not be referred (Table 4).

Living Donor Liver Transplantation Favors Early Transplant Rather Than Listing

Due to the prolonged waiting time, there is significant mortality on the deceased donor liver transplant (DDLT) list and a financial and psychological burden.57,58 Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) circumvents these issues and results in comparable or better posttransplant survival with reduced resource utilization. Additionally, there is certainty about timing, and the graft quality can be assured.66,67 In fact, a recent study showed that an LDLT is associated with a substantial survival benefit for patients with end-stage liver disease, even at MELD-Na scores as low as 11.68 Furthermore, the Korean study reported encouraging survival rates for 190 ACLF patients who underwent LDLT. The survival rates at 1-, 3-, and 5-years posttransplant were found to be 79.5%, 73.6%, and 72.1%, respectively, showcasing the efficacy of LDLT in ACLF patient management.69 Early LDLT (eLDLT) among patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis associated with 72% survival at a median follow up of 551 days70 with low risk for relapse or problem drinking after LDLT.71

Indications, Timing, and Referral for Liver Transplantation in Patients With Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure

ACLF is an acute deterioration of known or unknown CLD with the development of multiorgan failure and carries a high short-term mortality.72,73 The 28-day reported mortality rate in patients with ACLF without LT is between 30% and 51%.73,74 LT is the only curative option for patients with ACLF. Recent studies have shown a 1-year post-LT survival rate between 70% and 80% in ACLF patients and were comparable to other indications.4,75 Therefore, all patients with ACLF should be evaluated for LT (Figure 1) at presentation, and the therapy for the precipitating event and supportive treatment for failing organs should continue simultaneously.

ACLF definitions, prognostic markers, and LT indications vary among the three major societies.11,72,76 However, there has been a consensus across these societies that the MELD score poorly predicts outcomes in ACLF patients.11,12,77 Table 5 summarizes the definitions and grades of ACLF in these major societies. The EASL CLIF-C ACLF score provided an estimate of the risk of death than the MELD, MELD-Na, and Child-Pugh scores. The APASL ACLF Research Consortium (AARC) developed a prognostic score (AARC score), including total bilirubin, HE grades, INR, lactate, and serum creatinine, ranging from 5 to 15. The AARC score performed better than the Child-Pugh, MELD, Sequential Organ Failure Assesment (SOFA), and CLIF-SOFA scores in predicting 28-day mortality. In both scoring systems, the evolution of the score and the grade of ACLF during the first week predict the outcome of patients. The North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease (NACSELD) ACLF score could predict better survival in short-term inpatients than MELD and Child-Pugh scores.11,12, Also the timing decision, and proposal for a structured, protocolized care were suggested.

Table 5.

Summary of Definitions for OF and Grades of ACLF.

| Failing organs | APASL AARC |

EASL-CLIF |

NACSELD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | |||

| Liver | Total bilirubin ≥5 mg/dL and INR ≥1.5 | Bilirubin level of >12 mg/dL | - |

| Kidney | Acute kidney injury network criteria | Creatinine level of ≥2.0 mg/dL or renal replacement | Need for dialysis or other forms of renal replacement therapy |

| Brain | West-Haven HE grades 3–4 | West-Haven HE grades 3–4 | West-Haven HE grades 3–4 |

| Coagulation | INR ≥1.5 | INR ≥2.5 | - |

| Circulation | – | Use of vasopressor (terlipressin and/or catecholamines) |

Presence of shock defined by mean arterial pressure <60 mm Hg or a reduction of 40 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure from baseline, despite adequate fluid resuscitation and cardiac output |

| Respiration | – | PaO2/FiO2 of ≤200 or SpO2/FiO2 of ≤214 or need for mechanical ventilation |

Need for mechanical ventilation |

|

AARC grades |

EASL-CLIF ACLF grades |

NACSELD ACLF grades |

|

| AARC model: Bilirubin, INR, lactate, creatinine, HE grades. ACLF grades according to AARC model: Grade 1: 5-7 Grade 2: 8-10 Grade 3: 11-15 |

Grade 1:

Grade 3: ≥3 OF |

Grade 0: No OF Grade 1: Single OF Grade 2: Two OF Grade 3: Three OF Grade 4: Four or more OF |

|

AARC-APASL AARC, Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver ACLF Research Consortium; EASL-CLIF, European Association for the Study of Liver-Chronic Liver Failure; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; NACSELD, North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease; OF, organ failure.

Liver Transplant in Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure is Urgent or Emergent

All patients admitted with ACLF should be evaluated for LT because of its unpredictable natural history, potential for rapid deterioration, high short-term mortality, and narrow therapeutic window.12 Patients who have recovered from ACLF may worsen in subsequent follow-up,78 and it has been shown that they could have a higher 180-day mortality rate (, 40 %–50 %).74 Thus, patients with ACLF may benefit from evaluation and listing for LT, even if they are not transplanted. Patients with ACLF grades 1 and 2 should be listed for LT. According to APASL, a baseline MELD score >30, an AARC score >10, and advanced HE in the absence of overt sepsis or multiorgan failure can be considered for early LT.12 These scores should be reassessed after the diagnosis in 3–7 days to predict the outcome of patients.72, 73, 74 Patients with ACLF grade 3 should be considered for early LT if they are suitable candidates, as the results are favorable in selected cases.12,76,77 But patients with ACLF-3 experience a higher rate of complications and a longer hospital stay.79, 80, 81 A recent meta-analysis showed that ACLF grade had the strongest association with posttransplant survival, and patients with ACLF grade 3 had worse outcomes than those with grades 1 and 2.82

Contraindications and Ineligibility for Liver Transplant in Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure

Contraindications for LT in patients with ACLF have been poorly described. However, many studies have shown favorable outcomes, which should be interpreted with caution as most of them lack granularity and possible selection bias with retrospective registries. The EASL-CLIF Consortium highlighted that the presence of ≥4 OFs or a CLIF-C ACLF score of >64 on days 3–7 after diagnosis could indicate futility.73,74 APASL recommends that the presence of a bilirubin level >22 mg/dL, HE grade 3 or 4, INR >2.5 with either a creatinine level >1 mg/dL or lactate >1.5 mmol/L at baseline, and persistent derangement at days 4 or 7 could indicate the futility of care.12 The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines suggested that patients with cirrhosis and ACLF and being in mechanical ventilation due to Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) or brain-related conditions despite optimal therapy should not be listed for LT.83 LDLT is the better option once indicated in ACLF patients. Recently, Kulkarni et al.84 showed that delay in LT is associated with high health care resource utilization and financial burden with no appreciable survival benefit.

Due to the lack of structured national/regional DDLT programs in Asian countries, LDLT gives patients a ray of hope and, indeed, is the most frequent type of liver transplant conducted in Asia. With a focus on the Asian cohort, Choudhury et al. have proposed a concept of “ineligibility for LT and Liver Transplant Window” based on the analysis of a large AARC database. There are four basic principles of this concept: i) As patients with ACLF have an unpredictable course and high mortality, nearly all should be evaluated for LT at the presentation; ii) in the presence of ACLF, transplant outcome may not be optimal, so resource utilization is a particular concern; iii) optimizing patients with ACLF over one week with close monitoring can provide differentiation into the best candidates for transplant or for futility; and iv) high-grade ACLF should not be viewed as a contraindication, but at a certain time point, the patient may be ineligible or unsuitable. In summary, the following should be considered “ineligibility for liver transplant”.

Ineligibility for Liver Transplantation

-

I.

Septic shock

-

II.

Sepsis with two or more organ failures

-

III.

Uncontrolled sepsis

-

IV.

Four or more organ failures at a time point

-

V.Renal failure as defined by

-

a.Serum creatinine > 4 mg/dL

-

b.Increase in creatinine by 300% from baseline

-

c.Need for renal replacement therapy

-

a.

-

VI.

Respiratory failure or HE requiring ventilatory support >72 h

Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure: Liver Transplant Window, Optimization, and Timeframe for Liver Transplantation Decision

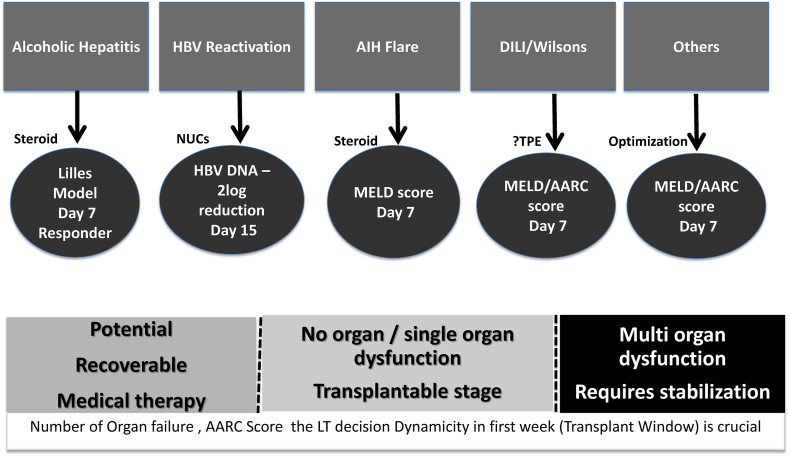

The basic principles of management of patients with ACLF include: i) treatment of the ongoing acute insult (antivirals in the case of hepatitis B virus-related ACLF, steroids for autoimmune hepatitis flare, and severe alcoholic hepatitis); ii) prevention of complications (albumin, diuretic, nutrition, antibiotic); iii) and supportive organ measures (Figure 3). Nearly two-thirds develop systemic inflammatory response syndrome SIRS or sepsis by the end of the first week. Nearly one-fourth of patients with ACLF succumb in the first week; thus, the first week is crucial for the transplant window for the sick ACLF cohort.4 With supportive measures, some of these sick patients may recover. However, nearly half of the patients continue to worsen and may develop multiorgan failure, leading to short-term mortality in the absence of LT (Figure 3).5

Figure 3.

Decision and time frame of liver transplant in patients of ACLF. ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure.

Patients with ACLF develop SIRS and sepsis within 7 days of hospitalization.85 Nearly two-third, of ACLF patients had SIRS with or without sepsis at presentation, and nearly half of them stabilized by the end of the first week on supportive management.85 On the other side of the spectrum, the rapid progression of liver failure and the onset of multiorgan failure result in only a fraction of patients being eligible for transplantation by the end of the first week.74 In the presence of ≥4 organ failures at admission and persistence of the same at 3–7 days leads to 100% mortality by 28 days in the absence of liver transplantation.65 Timely LT can achieve excellent one and 5-year survival in ACLF, close to 90%.6,75

Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure: Transplant Evaluation, Expedition, and Prioritization

In patients with ACLF, the transplantation need is immediate and dynamic. Existing prediction models such as CTP, MELD, and MELD-Na scores do not reflect the risk of death in these patients and are thus unsuitable for use. Currently, CLIF SOFA and CLIF C ACLF scores are being used as guides to detect futility and, thus, indirectly, the need for LT. Currently, results from ACLF Grade 3 are shown to be transplanted in the LDLT scenario with an acceptable result.82ACLF patient and often sick from an Eastern perspective, particularly in an Indian scenario, the decision for LT is often perceived by the relatives only after the failed medical therapies. These lead to increased resource utilization, average outcome, and more financial implication.86 The AARC score is another alternative approach that is dynamic in nature. A recent abstract by Choudhury et al. suggested the AARC score and its dynamic change to consider for transplant needs.87 A MELD-Na score of 35 is used for organ allocation on priority in cirrhosis across the USA. A study from Canada showed that ACLF patients with a MELD-Na score of 40 or more behave like status 1a, and in the absence of LT, they had extremely poor outcomes.79 So, selected patients with ACLF should be prioritized for LT.86, 87, 88, 89, 90 The ACLF has controversies with definitions; however, the patient profile is also different as far as the ACLF is concerned between East and West, as we mentioned in Table 6 in details for clarity of the patient as far as the ACLF diagnosis for therapy consideration. There is currently no guidance, so the following suggestions should be considered expert opinion/recommendations.

-

I.

Patients diagnosed with ACLF, irrespective of the Eastern or Western definition, should be considered for LT evaluation.

-

II.

For DDLT, early evaluation and listing are required. As a guide, a MELD score above 30 or an AARC score of 10 or more should trigger a transplant workup.

-

III.

DDLT priority in the absence of society guidance should be based upon the prevailing allocation policy based on the MELD score.

-

IV.

In the LDLT scenario, simultaneous donor and recipient evaluation and optimization of patients from the beginning, when they have a MELD score of 30 or more or an AARC score of 10, should commence.

-

V.

A MELD-Na score of more than 30 beyond 7 days or new-onset encephalopathy or its persistence should be an indication for urgent/emergent LT.

-

VI.

Plasma exchange as a bridge may help selected patients by reducing SIRS and should be considered.

Table 6.

Identifying a Patient of ACLF – East Versus West.

| EASL | NASCELD | APASL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Acutely decompensated cirrhosis, with or without prior episode(s) of decompensation | Acutely decompensated cirrhosis, with or without prior episode(s) of decompensation | Compensated cirrhosis (diagnosed or undiagnosed) or noncirrhotic chronic liver disease, who had a first episode of acute liver deterioration due to an acute insult directed to the liver |

| Precipitant | Intrahepatic (alcoholic hepatitis), extra hepatic (infection, gastrointestinal hemorrhage), or both | Extra hepatic (infection) | Intrahepatic |

| Major organ systems considered | 6: liver, kidney, brain, coagulation, circulation and respiration | 4: kidney, brain, circulation and Intrahepatic (HBV reactivation), extra hepatic (bacterial infection) or both. Liver and coagulation are not considered |

Liver dysfunction is central |

| Basis of the definition | The definition of ACLF is based on the existence of the failure of 1 of the 6 major organ systems. The failure of each organ system is assessed using the CLIF-C organ failure scale |

The definition of ACLF is based on the existence of 2 organ system failures or more (maximum 4) | The definition of ACLF is based on the presence of liver dysfunction. Extra hepatic organ failures may subsequently develop but are not included in the definition |

| Short-term mortality rate | By 28 days: Grade 1: 20% Grade 2: 30% Grade 3: 80% |

By 30 days: 2 organ failures: 49% 3 organ failures: 64% 4 organ failures: 77% |

By 28 days: Grade 1: 13% Grade 2: 45% Grade 3: 86% |

ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; APASL, Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver ACLF Research Consortium; CLIF, Chronic Liver Failure; EASL, European Association for the Study of Liver; NACSELD, North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease; OF, organ failure.

SUMMARY

To conclude, LT is an established therapeutic option for individuals with end-stage liver disease and is being increasingly used in patients with ACLF. The present data indicates that LT should be offered early in the course of ACLF before the onset of sepsis and multiorgan failure to improve outcomes. Despite the increasing need for LT, organ shortages remain an issue. Hence, it is crucial for healthcare providers to be up-to-date on the indications and contraindications for LT, both for living and diseased donors, to start a timely transplant assessment. Early referral for LT in the living donor dominant program and listing at the first decompensating event, particularly in cadaveric transplant programs, may help to improve the outcome.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Ashok Choudhury: Conceptualization, Writing - Original Draft, Supervision, Project administration.

Gupse Adali: Methodology, Resources, Writing - Original Draft, Visualization.

Rahul Kumar: Software, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision.

Apichat Kaewdech: Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft.

Suprabhat Giri: Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Funding

None.

Disclosure

None.

References

- 1.Mokdad A.A., Lopez A.D., Shahraz S., et al. Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med. 2014 Sep 18;12:145. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0145-y. PMID: 25242656; PMCID: PMC4169640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adam R., Karam V., Delvart V., et al. For All contributing centers (www.eltr.org); European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA). Evolution of indications and results of liver transplantation in Europe. A report from the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR) J Hepatol. 2012 Sep;57:675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.015. Epub 2012 May 16. PMID: 22609307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trebicka J., Sundaram V., Moreau R., Jalan R., Arroyo V. Liver transplantation for acute-on-chronic liver failure: science or fiction? Liver Transplant. 2020 Jul;26:906–915. doi: 10.1002/lt.25788. PMID: 32365422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belli L.S., Duvoux C., Artzner T., et al. Liver transplantation for patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) in Europe: results of the ELITA/EF-CLIF collaborative study (ECLIS) J Hepatol. 2021;75:610–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adam R., Karam V., Cailliez V., et al. For all the other 126 contributing centers (www.eltr.org) and the European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA). 2018 Annual Report of the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR) - 50-year evolution of liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2018 Dec;31:1293–1317. doi: 10.1111/tri.13358. PMID: 30259574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwong A.J., Ebel N.H., Kim W.R., et al. OPTN/SRTR 2020 annual data report: liver. Am J Transplant. 2022 Mar;22(suppl 2):204–309. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16978. PMID: 35266621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laique S.N., Zhang N., Hewitt W.R., Bajaj J., Vargas H.E. Increased access to liver transplantation for patients with acute on chronic liver failure after implementation of Share 35 Rule: an analysis from the UNOS database. Ann Hepatol. 2021 Jul-Aug;23 doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2020.100288. Epub 2020 Nov 18. PMID: 33217586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamath P.S., Wiesner R.H., Malinchoc M., et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001 Feb;33:464–470. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. PMID: 11172350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merion R.M., Schaubel D.E., Dykstra D.M., Freeman R.B., Port F.K., Wolfe R.A. The survival benefit of liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005 Feb;5:307–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00703.x. PMID: 15643990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaubel D.E., Sima C.S., Goodrich N.P., Feng S., Merion R.M. The survival benefit of deceased donor liver transplantation as a function of candidate disease severity and donor quality. Am J Transplant. 2008 Feb;8:419–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02086.x. Epub 2008 Jan 7. PMID: 18190658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jalan R., Saliba F., Pavesi M., et al. For CANONIC study investigators of the EASL-CLIF Consortium. Development and validation of a prognostic score to predict mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2014 Nov;61:1038–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.012. Epub 2014 Jun 17. PMID: 24950482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choudhury A., Jindal A., Maiwall R., Sharma M.K., Sharma B.C., et al. for APASL ACLF Working Party Liver failure determines the outcome in patients of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF): comparison of APASL ACLF research consortium (AARC) and CLIF-SOFA models. Hepatol Int. 2017 Sep;11:461–471. doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9816-z. Epub 2017 Aug 30. PMID: 28856540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Leary J.G., Reddy K.R., Garcia-Tsao G., et al. NACSELD acute-on-chronic liver failure (NACSELD-ACLF) score predicts 30-day survival in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2018 Jun;67:2367–2374. doi: 10.1002/hep.29773. Epub 2018 Apr 19. PMID: 29315693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim W.R., Biggins S.W., Kremers W.K., et al. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the liver-transplant waiting list. N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 4;359:1018–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801209. PMID: 18768945; PMCID: PMC4374557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman R.B., Jr., Gish R.G., Harper A., et al. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) exception guidelines: results and recommendations from the MELD Exception Study Group and Conference (MESSAGE) for the approval of patients who need liver transplantation with diseases not considered by the standard MELD formula. Liver Transplant. 2006 Dec;12(12 suppl 3):S128–S136. doi: 10.1002/lt.20979. Erratum in: Liver Transpl. 2008 Sep;14(9):1386. PMID: 17123284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim W.R., Mannalithara A., Heimbach J.K., et al. Meld 3.0: the model for end-stage liver disease updated for the modern Era. Gastroenterology. 2021 Dec;161:1887–1895.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.050. Epub 2021 Sep 3. PMID: 34481845; PMCID: PMC8608337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salerno F., Guevara M., Bernardi M., et al. Refractory ascites: pathogenesis, definition and therapy of a severe complication in patients with cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2010 Aug;30:937–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02272.x. Epub 2010 May 21. Erratum in: Liver Int. 2010 Sep;30(8):1244. PMID: 20492521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bureau C., Thabut D., Oberti F., et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts with covered stents increase transplant-free survival of patients with cirrhosis and recurrent ascites. Gastroenterology. 2017 Jan;152:157–163. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.016. Epub 2016 Sep 20. Erratum in: Gastroenterology. 2017 Sep;153(3):870. PMID: 27663604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bureau C., Adebayo D., Chalret de Rieu M., et al. Alfapump® system vs. large volume paracentesis for refractory ascites: a multicenter randomized controlled study. J Hepatol. 2017 Nov;67:940–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.010. Epub 2017 Jun 21. Erratum in: J Hepatol. 2018 Jan 29;: Erratum in: J Hepatol. 2020 Mar;72(3):595-596. PMID: 28645737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Association for the Study of the Liver Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018 Aug;69:406–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024. Epub 2018 Apr 10. Erratum in: J Hepatol. 2018 Nov;69(5):1207. PMID: 29653741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piano S., Singh V., Caraceni P., et al. For international Club of ascites global study group. Epidemiology and effects of bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis worldwide. Gastroenterology. 2019 Apr;156:1368–1380.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.005. Epub 2018 Dec 13. PMID: 30552895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furey C., Zhou S., Park J.H., et al. Impact of bacteria types on the clinical outcomes of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2023 May;68:2140–2148. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-07867-8. Epub 2023 Mar 7. PMID: 36879176; PMCID: PMC10133085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdel-Razik A., Abdelsalam M., Gad D.F., et al. Recurrence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: novel predictors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun;32:718–726. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001578. PMID: 31651658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levey A.S., Eckardt K.U., Dorman N.M., et al. Nomenclature for kidney function and disease: report of a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) consensus conference. Kidney Int. 2020 Jun;97:1117–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.02.010. Epub 2020 Mar 9. PMID: 32409237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cullaro G., Kanduri S.R., Velez J.C.Q. Acute kidney injury in patients with liver disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022 Nov;17:1674–1684. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03040322. Epub 2022 Jul 28. PMID: 35902128; PMCID: PMC9718035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angeli P., Gines P., Wong F., et al. For International Club of Ascites. Diagnosis and management of acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis: revised consensus recommendations of the International Club of Ascites. Gut. 2015 Apr;64:531–537. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308874. Epub 2015 Jan 28. PMID: 25631669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biggins S.W., Angeli P., Garcia-Tsao G., et al. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome: 2021 practice guidance by the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2021 Aug;74:1014–1048. doi: 10.1002/hep.31884. PMID: 33942342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nair G., Nair V. Simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation. Clin Liver Dis. 2022 May;26:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2022.01.011. PMID: 35487613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerbert A.J.C., Reverter E., Verbruggen L., et al. Impact of hepatic encephalopathy on liver transplant waiting list mortality in regions with different transplantation rates. Clin Transplant. 2018 Nov;32 doi: 10.1111/ctr.13412. Epub 2018 Oct 8. PMID: 30230613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gadiparthi C., Cholankeril G., Yoo E.R., Hu M., Wong R.J., Ahmed A. Waitlist outcomes in liver transplant candidates with high MELD and severe hepatic encephalopathy. Dig Dis Sci. 2018 Jun;63:1647–1653. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5032-5. Epub 2018 Apr 2. PMID: 29611079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montano-Loza A.J., Meza-Junco J., Prado C.M., et al. Muscle wasting is associated with mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Feb;10:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.08.028. 173.e1. Epub 2011 Sep 3. PMID: 21893129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tandon P., Ney M., Irwin I., et al. Severe muscle depletion in patients on the liver transplant wait list: its prevalence and independent prognostic value. Liver Transplant. 2012 Oct;18:1209–1216. doi: 10.1002/lt.23495. PMID: 22740290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cruz-Jentoft A.J., Bahat G., Bauer J., et al. Writing group for the European working group on sarcopenia in older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the extended group for EWGSOP2. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019 Jan 1;48:16–31. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy169. Erratum in: Age Ageing. 2019 Jul 1;48(4):601. PMID: 30312372; PMCID: PMC6322506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L.K., Liu L.K., Woo J., Assantachai P., Auyeung T.W., et al. Sarcopenia in asia: consensus report of the asian working group for sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014 Feb;15:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025. PMID: 24461239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishikawa H., Shiraki M., Hiramatsu A., Moriya K., Hino K., Nishiguchi S. Japan Society of Hepatology guidelines for sarcopenia in liver disease (1st edition): recommendation from the working group for creation of sarcopenia assessment criteria. Hepatol Res. 2016 Sep;46:951–963. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12774. PMID: 27481650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng H., Zhang Q., Luo L., et al. A prognostic model of acute-on-chronic liver failure based on sarcopenia. Hepatol Int. 2022 Aug;16:964–972. doi: 10.1007/s12072-022-10363-2. Epub 2022 Jun 30. PMID: 35771410; PMCID: PMC9349113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Vugt J.L.A., Alferink L.J.M., Buettner S., et al. A model including sarcopenia surpasses the MELD score in predicting waiting list mortality in cirrhotic liver transplant candidates: a competing risk analysis in a national cohort. J Hepatol. 2018 Apr;68:707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.11.030. Epub 2017 Dec 6. PMID: 29221886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sinclair M., Chapman B., Hoermann R., et al. Handgrip strength adds more prognostic value to the model for end-stage liver disease score than imaging-based measures of muscle mass in men with cirrhosis. Liver Transplant. 2019 Oct;25:1480–1487. doi: 10.1002/lt.25598. Epub 2019 Aug 18. PMID: 31282126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lai J.C., Covinsky K.E., Dodge J.L., et al. Development of a novel frailty index to predict mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2017 Aug;66:564–574. doi: 10.1002/hep.29219. Epub 2017 Jun 28. PMID: 28422306; PMCID: PMC5519430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai J.C., Sonnenday C.J., Tapper E.B., et al. Frailty in liver transplantation: an expert opinion statement from the American society of transplantation liver and intestinal community of practice. Am J Transplant. 2019 Jul;19:1896–1906. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15392. Epub 2019 May 8. PMID: 30980701; PMCID: PMC6814290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golse N., Bucur P.O., Ciacio O., et al. A new definition of sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2017 Feb;23:143–154. doi: 10.1002/lt.24671. Epub 2017 Jan 6. PMID: 28061014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaido T., Ogawa K., Fujimoto Y., et al. Impact of sarcopenia on survival in patients undergoing living donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013 Jun;13:1549–1556. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12221. Epub 2013 Apr 19. PMID: 23601159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dhanasekaran R., West J.K., Gonzales P.C., et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for symptomatic refractory hepatic hydrothorax in patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Mar;105:635–641. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.634. Epub 2009 Nov 10. PMID: 19904245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osman K.T., Abdelfattah A.M., Mahmood S.K., Elkhabiry L., Gordon F.D., Qamar A.A. Refractory hepatic hydrothorax is an independent predictor of mortality when compared to refractory ascites. Dig Dis Sci. 2022 Oct;67:4929–4938. doi: 10.1007/s10620-022-07522-8. Epub 2022 May 9. PMID: 35534742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romero S., Lim A.K., Singh G., et al. Natural history and outcomes of patients with liver cirrhosis complicated by hepatic hydrothorax. World J Gastroenterol. 2022 Sep 21;28:5175–5187. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i35.5175. PMID: 36188717; PMCID: PMC9516676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liver review board guidance - OPTN. Accessed February 5, 2023. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/professionals/by-topic/guidance/liver-review-board-guidance/.

- 47.Sendra C., Carballo-Rubio V., Sousa J.M. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension: management in liver transplantation in the horizon 2020. Transplant Proc. 2020 Jun;52:1503–1506. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2020.02.057. Epub 2020 Apr 9. PMID: 32278579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krowka M.J., Fallon M.B., Kawut S.M., et al. International liver transplant society practice guidelines: diagnosis and management of hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension. Transplantation. 2016 Jul;100:1440–1452. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001229. PMID: 27326810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tokushige K., Kogiso T., Egawa H. Current therapy and liver transplantation for portopulmonary hypertension in Japan. J Clin Med. 2023 Jan 10;12:562. doi: 10.3390/jcm12020562. PMID: 36675490; PMCID: PMC9867251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DiMartini A., Dew M.A., Javed L., Fitzgerald M.G., Jain A., Day N. Pretransplant psychiatric and medical comorbidity of alcoholic liver disease patients who received liver transplant. Psychosomatics. 2004 Nov-Dec;45:517–523. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.6.517. PMID: 15546829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gedaly R., McHugh P.P., Johnston T.D., et al. Predictors of relapse to alcohol and illicit drugs after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Transplantation. 2008 Oct 27;86:1090–1095. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181872710. PMID: 18946347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathurin P., Moreno C., Samuel D., et al. Early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2011 Nov 10;365:1790–1800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105703. PMID: 22070476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grover S., Sarkar S. Liver transplant-psychiatric and psychosocial aspects. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2012 Dec;2:382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2012.08.003. Epub 2012 Dec 16. PMID: 25755459; PMCID: PMC3940381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Organ procurement and transplantation Network. Data. 2022 https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/# [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiesner R., Edwards E., Freeman R., et al. United Network for organ sharing liver disease severity score committee. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology. 2003 Jan;124:91–96. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50016. PMID: 12512033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Santos G.G., Gonçalves L.C., Buzzo N., et al. Quality of life, depression, and psychosocial characteristics of patients awaiting liver transplants. Transplant Proc. 2012 Oct;44:2413–2415. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.07.046. PMID: 23026609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miyazaki E.T., Dos Santos R., Jr., Miyazaki M.C., et al. Patients on the waiting list for liver transplantation: caregiver burden and stress. Liver Transplant. 2010 Oct;16:1164–1168. doi: 10.1002/lt.22130. PMID: 20879014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fox R.K. When to consider liver transplant during the management of chronic liver disease. Med Clin. 2014 Jan;98:153–168. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2013.09.007. Epub 2013 Oct 31. PMID: 24266919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duong N., Sadowski B., Rangnekar A.S. The impact of frailty, sarcopenia, and malnutrition on liver transplant outcomes. Clin Liver Dis. 2021 May 1;17:271–276. doi: 10.1002/cld.1043. PMID: 33968388; PMCID: PMC8087926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martin P., DiMartini A., Feng S., Brown R., Jr., Fallon M. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American association for the study of liver diseases and the American society of transplantation. Hepatology. 2014 Mar;59:1144–1165. doi: 10.1002/hep.26972. PMID: 24716201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.European Association for the Study of the Liver Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2016 Feb;64:433–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.10.006. PMID: 26597456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murray K.F., Carithers R.L., Jr., AASLD AASLD practice guidelines: evaluation of the patient for liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2005 Jun;41:1407–1432. doi: 10.1002/hep.20704. PMID: 15880505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burra P., Giannini E.G., Caraceni P., et al. Specific issues concerning the management of patients on the waiting list and after liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2018 Aug;38:1338–1362. doi: 10.1111/liv.13755. Epub 2018 May 16. PMID: 29637743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blumberg E.A., Rogers C.C. American society of transplantation infectious diseases community of practice. Solid organ transplantation in the HIV-infected patient: guidelines from the American society of transplantation infectious diseases community of practice. Clin Transplant. 2019 Sep;33 doi: 10.1111/ctr.13499. Epub 2019 Apr 21. PMID: 30773688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sarin S.K., Choudhury A., Sharma M.K., et al. for APASL ACLF Research Consortium (AARC) for APASL ACLF working Party Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver (APASL): an update. Hepatol Int. 2019 Jul;13:353–390. doi: 10.1007/s12072-019-09946-3. Epub 2019 Jun 6. Erratum in: Hepatol Int. 2019 Nov;13(6):826-828. PMID: 31172417; PMCID: PMC6728300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wong T.C.L., Ng K.K.C., Fung J.Y.Y., et al. Long-term survival outcome between living donor and deceased donor liver transplant for hepatocellular carcinoma: intention-to-treat and propensity score matching analyses. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019 May;26:1454–1462. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07206-0. Epub 2019 Feb 8. PMID: 30737669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jackson W.E., Malamon J.S., Kaplan B., et al. Survival benefit of living-donor liver transplant. JAMA Surg. 2022 Oct 1;157:926–932. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.3327. PMID: 35921119; PMCID: PMC9350845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xia L., Qiao Z.Y., Zhang Z.J., et al. Transplantation for EASL-CLIF and APASL acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) patients: the TEA cohort to evaluate long-term post-Transplant outcomes. E Clinical Medicine. 2022 Jun 4;49 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101476. PMID: 35747194; PMCID: PMC9167862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moon D.B., Lee S.G., Kang W.H., et al. Adult living donor liver transplantation for acute-on-chronic liver failure in high-model for end-stage liver disease score patients. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1833–1842. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kulkarni A.V., Reddy R., Arab J.P., et al. Early living donor liver transplantation for alcohol-associated hepatitis. Ann Hepatol. 2023 Apr 6;28 doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2023.101098. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37028597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Falari SS, Mohapatra N, Patil NS, et al. Incidence and predictors of alcohol relapse following living donor liver transplantation for alcohol related liver disease. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2023 Aug;30(8):1015–1024. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.1325. Epub 2023 Mar 15. PMID: 36866490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moreau R., Jalan R., Gines P., et al. CANONIC Study Investigators of the EASL–CLIF Consortium. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013 Jun;144:1426–1437. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.042. 1437.e1-1437. Epub 2013 Mar 6. PMID: 23474284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gustot T., Fernandez J., Garcia E., et al. For CANONIC Study Investigators of the EASL-CLIF Consortium. Clinical Course of acute-on-chronic liver failure syndrome and effects on prognosis. Hepatology. 2015 Jul;62:243–252. doi: 10.1002/hep.27849. Epub 2015 May 29. PMID: 25877702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maiwall R, Pasupuleti SSR, Choudhury A, et al. AARC score determines outcomes in patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis: a multinational study. Hepatol Int. 2023 Jun;17(3):662–675. doi: 10.1007/s12072-022-10463-z. Epub 2022 Dec 26. PMID: 36571711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sundaram V., Patel S., Shetty K., et al. For multi-organ dysfunction and evaluation for liver transplantation (MODEL) consortium. Risk factors for post transplantation mortality in recipients with grade 3 acute-on-chronic liver failure: analysis of a North American consortium. Liver Transplant. 2022 Jun;28:1078–1089. doi: 10.1002/lt.26408. Epub 2022 Feb 9. PMID: 35020260; PMCID: PMC9117404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bajaj J.S., O'Leary J.G., Reddy K.R., Wong F., et al. For North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease (NACSELD). Survival in infection-related acute-on-chronic liver failure is defined by extrahepatic organ failures. Hepatology. 2014 Jul;60:250–256. doi: 10.1002/hep.27077. Epub 2014 May 29. PMID: 24677131; PMCID: PMC4077926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hernaez R., Liu Y., Kramer J.R., Rana A., El-Serag H.B., Kanwal F. Model for end-stage liver disease-sodium underestimates 90-day mortality risk in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2020 Dec;73:1425–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.06.005. Epub 2020 Jun 10. PMID: 32531416; PMCID: PMC10424237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thuluvath P.J., Thuluvath A.J., Hanish S., Savva Y. Liver transplantation in patients with multiple organ failures: feasibility and outcomes. J Hepatol. 2018 Nov;69:1047–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.07.007. Epub 2018 Jul 31. PMID: 30071241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sundaram V., Jalan R., Wu T., et al. Factors associated with survival of patients with severe acute-on-chronic liver failure before and after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2019 Apr;156:1381–1391.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.007. Epub 2018 Dec 18. PMID: 30576643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Singh S.A., Pampaniya H., Mehtani R., et al. Living donor liver transplant in acute on chronic liver failure grade 3: who not to transplant. Dig Liver Dis. 2024 Jan;56:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2023.07.024. Epub 2023 Aug 6. PMID: 37550101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Artru F., Louvet A., Ruiz I., Levesque E., et al. Liver transplantation in the most severely ill cirrhotic patients: a multicenter study in acute-on-chronic liver failure grade 3. J Hepatol. 2017 Oct;67:708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.009. Epub 2017 Jun 21. PMID: 28645736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Choudhury A., Vijayaraghavan R., Maiwall R., et al. for APASL ACLF Research Consortium (AARC) for APASL ACLF Working Party 'First week' is the crucial period for deciding living donor liver transplantation in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatol Int. 2021 Dec;15:1376–1388. doi: 10.1007/s12072-021-10206-6. Epub 2021 Oct 4. PMID: 34608586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sarin S.K., Choudhury A. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: terminology, mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Mar;13:131–149. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.219. Epub 2016 Feb 3. PMID: 26837712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Choudhury A., Kumar M., Sharma B.C., et al. For APASL ACLF working party. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome in acute-on-chronic liver failure: relevance of 'golden window': a prospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Dec;32:1989–1997. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13799. PMID: 28374414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Humar A., Ganesh S., Jorgensen D., et al. Adult living donor versus deceased donor liver transplant (LDLT versus DDLT) at a single center: time to change our paradigm for liver transplant. Ann Surg. 2019 Sep;270:444–451. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003463. PMID: 31305283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kulkarni AV, Reddy R, Sharma M, et al. Healthcare utilization and outcomes of living donor liver transplantation for patients with APASL-defined acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatol Int. 2023 Oct;17(5):1233–1240. doi: 10.1007/s12072-023-10548-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Choudhury, A.Kumar M.R., Sarin S.K., et al. for APASL ACLF working Party, ACLF Research Consortium (AARC) APASL ACLF research consortium (AARC) liver failure score defines the time-frame for liver transplant in ACLF patients. Hepatology. 2019 Oct;70:141–142. Abstract-217 AASLD. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu Y., Xu M., Duan B., Li G., Chen Y. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: clinical course and liver transplantation. Expet Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Mar;17:251–262. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2023.2180630. Epub 2023 Feb 19. PMID: 36779306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Heise M., Weiler N., Iken S., et al. Liver transplantation in acute-on-chronic liver failure: considerations for a systematic approach to decision making. Visc Med. 2018;34:291–294. doi: 10.1159/000492137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mahmud N. Selection for liver transplantation: indications and evaluation. Curr Hepat Rep. 2020;19:203–212. doi: 10.1007/s11901-020-00527-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]