Abstract

Tumour cell dormancy is critical for metastasis and resistance to chemoradiotherapy. Polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs) with giant or multiple nuclei and high DNA content have the properties of cancer stem cell and single PGCCs can individually generate tumours in immunodeficient mice. PGCCs represent a dormant form of cancer cells that survive harsh tumour conditions and contribute to tumour recurrence. Hypoxic mimics, chemotherapeutics, radiation and cytotoxic traditional Chinese medicines can induce PGCCs formation through endoreduplication and/or cell fusion. After incubation, dormant PGCCs can recover from the treatment and produce daughter cells with strong proliferative, migratory and invasive abilities via asymmetric cell division. Additionally, PGCCs can resist hypoxia or chemical stress and have a distinct protein signature that involves chromatin remodelling and cell cycle regulation. Dormant PGCCs form the cellular basis for therapeutic resistance, metastatic cascade and disease recurrence. This review summarises regulatory mechanisms governing dormant cancer cells entry and exit of dormancy, which may be used by PGCCs, and potential therapeutic strategies for targeting PGCCs.

Keywords: cell cycle arrest, dormancy, endoreduplication, polyploid giant cancer cells

1. PGCCs have emerged as a key regulator of tumour dormancy and reactivation.

2. Abnormal cell cycle regulation in PGCCs enables them to enter a reversibly dormant state and evade cancer therapy.

3. PGCCs achieve dormancy through endoreduplication and cell cycle arrest.

4. PGCCs can exit dormancy and recur via asymmetric division, thereby generating aggressive diploid progeny.

1. INTRODUCTION

Cancer dormancy is closely associated with metastasis. In this work ‘The Spread of Tumors in the Human Body’, Rupert A. Willis was the first to use the term, dormancy, to refer to cells that disseminate but are in growth arrest. 1 Later, Hadfield defined the dormant cancer cell as ‘malignant cells, although remaining alive for relatively long periods, show no evidence of proliferation during this time, yet retain all their former and vigorous capacity to proliferate’. 2 Dormant cancer cells are characterised by cell cycle arrest, indicating that they do not actively divide or proliferate. 3 , 4 , 5 Dormant cancer cells are usually in the non‐proliferative G0 or G1 phases. This state of cell cycle arrest allows dormant cancer cells to evade detection and destruction by the immune system, and traditional cancer treatment. 6 However, under certain conditions (such as changes in the microenvironment or immune system), dormant cells can reactivate and proliferate, leading to metastasis and recurrence. 7 , 8 , 9

Polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs) contribute to tumour heterogeneity and play essential roles in tumour progression. 10 The number of PGCCs is relevant to tumour grade, lymph node metastasis, recurrence, chemoresistance and poor prognosis. 11 PGCCs are also known as polyploid aneuploid cancer cells (PACC), 12 multinucleated giant cancer cells, 13 osteoclast‐like giant cells and cancer‐associated macrophage‐like cells. 14 PGCCs have either a single giant or multiple nuclei. Multinuclear PGCCs are more likely to occur when nuclear replication and separation is complete, and cytoplasmic separation fails. PGCCs with single giant nuclei appear when nuclear and cytoplasmic separation fail simultaneously. 15 , 16 , 17 PGCCs usually develop and enter a dormant state in response to stress, such as chemotherapy, radiation and hypoxia microenvironment. 11 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 The features of dormant PGCCs are abnormal cell cycle‐related protein expression and proliferative arrest, 25 resulting in an increase to the number of unbalanced chromosomal copies. 26 , 27 Since dormant PGCCs are usually in a non‐proliferative state, the toxic effects of systemic therapies are evaded and residual PGCCs later reactivate and proliferate, leading to tumour recurrence. 19 PGCCs are the driving force behind tumour recurrence and are a new focus in cancer research. Understanding the dormant characteristics of PGCCs and the biological mechanisms underlying reactivation are crucial to prevent metastatic growth and recurrence. In this review, we introduce the molecular mechanisms behind cancer cell entry and exit from dormancy and comprehensively describe why PGCCs are dormant. In addition, the abnormal cell cycle and pro‐cancer mechanisms of PGCCs after reactivation from dormancy are explored. We also discuss the potential treatment strategies for eliminating PGCCs.

2. DORMANCY AND CANCER

Tumour cell dormancy is an important stage of tumour metastasis. 28 , 29 , 30 Highly motile cell populations exist in early lesions and can enter dormancy at distant sites. 31 , 32 To maintain dormancy, tumour cells suppress genes required for DNA synthesis or cell division and promote expression of anti‐apoptotic, anti‐aging and anti‐differentiation genes. 33 , 34 Dormant cancer cells share several identical characteristics and signalling pathways with cancer stem cells, including recurrence, the ability to metastasize and evade the immune system. 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 Dormancy is defined by two important cellular characteristics: (1) growth arrest and (2) dissemination, which provide cancer cells the ability to leave the primary tumour. 1 Growth arrest allows dormant cancer cells to retain their proliferative capacity, which can be reversed by a series of intrinsic and cell‐extrinsic factors. 40 Proliferation occurs only after dormancy is disrupted, leading to the formation of tumours. 41

Growth arrest can allow disseminated cancer cells (DCCs) undergo different cellular states (migration, quiescence and proliferation) 42 , 43 , 44 and evade anticancer therapy and immune surveillance. 45 , 46 During dissemination, DCCs must overcome physical barriers by degrading the extracellular matrix (ECM) to invade the matrix, migrating along the ECM to leave the tumour and undergoing intravasation then extravasation by degrading the vascular basement membrane. 47 After the initiation of migration, DCCs reach various niches and actively settle into the new organ environment to establish dormancy. 48 , 49 , 50 After signals arising from the microenvironment, DCCs can switch from their dormant state and reemerge to proliferative growth. 8 Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is crucial gene expression program associated with cell quiescence and metastasis. 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 EMT is a key mechanism for initiating cell migration and maintaining the dormancy phenotype by utilizing mesenchymal programs that promote invasiveness and reduce proliferation. In contrast, epithelial programs reactivate cells from dormancy and induce metastatic growth. 46 Cytokines such as transforming growth factor‐β (TGF‐β), 55 interferon‐γ 56 and interleukin‐8 (IL‐8) 57 help maintain cell quiescence at distant metastatic sites.

3. MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF CANCER CELL ENTRY AND EXIT FROM DORMANCY

Regulatory mechanisms in dormant cancer cells can be divided into two categories: intracellular and extracellular. Intracellular regulatory mechanisms are influenced by cell cycle arrest, 58 redox signalling, 59 metabolic reprogramming 60 and autophagy. 61 Extracellular regulatory mechanisms are influenced by factors such as the microenvironment 62 and immune system. 63 For example, intracellular factors including CD133, Sox‐2 and E‐cadherin are used to assess the dormancy state of colorectal cancer cells in the liver, whereas vimentin, Ki‐67, c‐Myc, cyclin D1 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are used to assess the cell‐awakening state. 64 Regulation of the dormant cancer cell cycle involves multiple factors and pathways, such as cyclin‐dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors, which inhibit CDK activity and promote quiescence by preventing retinoblastoma protein (Rb) phosphorylation, which is required for G1/S transition. 65 P53 and cell cycle‐related proteins, TGF‐β signalling and p38/mitogen‐activated protein kinases (MAPK) signalling pathways can also promote quiescence by inhibiting CDK/cyclin and regulating cell growth, survival and differentiation. Many transcription factors, including P53, 66 Foxo family 67 and Myc, 68 , 69 nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group F, member 1 70 are involved in the regulation of quiescence and dormancy. Extracellular factors mediates dormancy including angiogenic (such as VEGF, 71 Angiostatin 72 ), immune (such as IL‐3, 73 interferon‐γ, 74 growth arrest‐specific protein 6, 75 leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor 76 ), ECM (such as TGF‐β1, 77 TGF‐β2, 35 insulin‐like growth factor 1, 78 E‐selectin, 79 bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7) 80 ) and stress‐induced factors (such as p38 MAPK 81 ). Cancer cell quiescence is a self‐protective mechanism that prevents destruction from hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, immune surveillance and chemotherapy. 82

3.1. P53 and cell cycle‐related proteins are involved in the dormancy of cancer cells

P53 and cell cycle‐related proteins are primary markers of cancer cell dormancy. 83 , 84 P53 activity in quiescent cells is higher than it in proliferating cells. 85 , 86 High expression of P53 regulates the activation of ubiquitin ligase anaphase‐promoting complex responding to 5‐fluorouracil‐induced dormancy in non‐small cell lung cancer. 52 P53 expression inhibits the CDK/cyclin complex, blocking cell cycle transition from the G1/S or G2/M phase. 87 CDK support the maintenance and escape of dormancy. Signals of dormancy typically increase the expression levels of CDK inhibitors or phosphorylation of Rb. 45 , 88 Various growth factors and signalling pathways can affect CDK activity and the proliferation/quiescence outcomes of cancer cells. 65 Ki67 and the CDK inhibitor (p27) are often used as markers of dormant tumour cells. 69 In gallbladder cancer (GBC), the expression of F‐box/WD repeat‐containing protein 7 and p27 is up‐regulated and associates with reduced GBC cell proliferation and entry into dormancy. 89 Moreover, CDK4 is down‐regulated and DCCs is dormant in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. 90 P53 and cell cycle‐related proteins are key factor regulating dormant cancer cells via influencing cell cycle.

3.2. TGF‐β signalling pathway is involved in the dormancy of cancer cells

TGF‐β signalling with various cellular functions are essential in tumour dormancy. TGF‐β signalling can disrupt persistent proliferation signals in cancer cells and maintain the quiescent state of dormant cells. 91 , 92 TGF‐β and other growth inhibitory signals can suppress the proliferation of DCCs. 93 , 94 Reactive oxygen species (ROS) stimulate TGF‐β2 on tumour cell membranes and activate p38, leading to cancer cell dormancy. 95 In addition, TGF‐β2 signalling, Rho‐Associated Coiled‐Coil Kinase (ROCK), α5β1 integrin (mainly distributed in fibroblasts, and its ligand is fibronectin) and αvβ3 integrin supports cancer cell of dormancy. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 release reactivates dormant cancer cells to proliferate. 96 In the lung, TGF‐β promotes niche settlement by inducing angiopoietin‐like 4 (a pro‐inflammatory factor), a mediator that helps cancer cells penetrate tissue. 97 TGF‐β2 combined with TGF‐β‐receptor‐I, TGF‐β‐receptor‐III and SMAD1/5 activation can induce the dormancy of lung metastatic foci of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. 90 The activity of TGF‐β signalling plays a critical role in the dormancy of lung metastatic cells by down‐regulating stimulators of interferon genes and C motif chemokine 5 (CCL5) expression. 98 TGF‐β signalling play a pivotal role in cellular dormancy.

3.3. p38/MAPK signalling pathway is relevant to the dormancy of cancer cells

As a tumour suppressor, p38/MAPK promotes cancer dormancy. 81 , 99 For example, Regucalcin can promote the dormancy of cancer cells by inducing p38 MAPK activation and forkhead box M1 (FOXM1) inhibition. 100 Glypican‐3 can induce tumour dormancy through the activation of p38 MAPK signalling pathway. 81 In cancer cells, the quiescence program of dormancy is induced by p38/MAPK activation, 81 extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK) 101 and phosphoinositide 3‐kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) inactivation, 102 as well as by decreasing glycolysis 103 and glucose uptake. 104 , 105 A high ratio of p38/ERK induces cells to enter dormancy, whereas a high ratio of ERK/p38 induces dormant cells to grow and proliferate. 5 , 101 , 106 Moreover, p38 signalling regulates stress associated protein promoting survival and resistance of dormant cells. p38 up‐regulate endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone BiP and the activation of ER stress‐activated eukaryotic translation initiator factor 2alpha kinase RNA‐dependent protein kinase‐like ER kinase protect dormant cancer cells from chemotherapy‐induced stress. 107 Targeting the p38/MAPK signalling pathway may be a therapeutic strategy to inhibit drug resistance mediated by dormancy.

3.4. Cell autophagy and dormancy of cancer cells

Autophagy indirectly regulates the cell cycle and participates in modulating the dormancy of cancer cells. 108 , 109 Inactivation of PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway promotes autophagy. 110 3‐Hydroxy butyrate dehydrogenase 2 overexpression induced autophagy, regulating intracellular ROS levels to inhibit the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, thereby inhibiting growth of gastric cancer. 111 Aplasia Ras homolog member I induce autophagy via inhibiting mTOR and PI3K signalling, up‐regulating ATG4 (autophagy protein), contributing to survival of dormant ovarian tumour cells. 112 Down‐regulation of polo‐like kinase 4 (PLK4) induces autophagy to maintain tumour cell dormancy. In PLK4 knockdown colorectal cancer cells, the expression of autophagy‐related molecules: autophagy protein 5, beclin1 and microtubule‐associated protein light chain 3B (LC3B‐II) drastically are up‐regulated. The mRNA expression of dormancy signalling molecules, including leucine‐rich α−2 glycoprotein 1, p15, p27, BMP7 and p16 were up‐regulated. the expression of CDK4, CDK6 and cell proliferation markers such as proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and Ki67 were down‐regulated. 113 Autophagy promotes dormancy of cancer cells and protects them from apoptosis under environmental stress.

3.5. ER stress signalling pathway regulates the dormancy of cancer cells

ER stress signalling maintains a stable quiescent‐like phenotype, ensuring cell survival under chronic ER stress. Slow‐cycling/dormant cancer cells (SCCs) adapt to ER stress under hypoxic and low‐glucose conditions. 114 ER stress facilitates the unfolded protein response to control the survival, growth arrest and death of stressed cells, which depends on the duration and severity of stress. 115 , 116 , 117 Regulator of G protein signalling 2 (RGS2) expression allows SCCs to increase their survival ability in ER stress‐induced apoptosis by degradation of activating transcription factor 4 and eukaryotic initiation factor 2 phosphorylation. RGS2 negatively regulates the expression of genes encoding cell proliferation factors (such as Ki67, cyclin D1, CDK4, PCNA and CDK2) and positively regulates the expression of genes encoding CDK inhibitors to maintain cell cycle arrest in dormant cancer cells. 118

3.6. Cdc42 GTPase regulate the dormancy of cancer cells

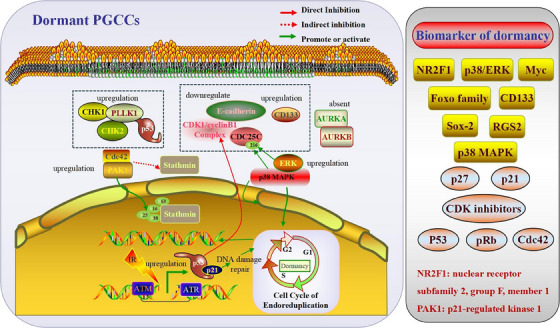

The GTPase cell division cycle 42 (Cdc42) play important roles in the regulation of cancer cell dormancy. Increased ECM stiffness leads to Cdc42 translocation to the nucleus, promoting hydroxymethylating enzyme Tet2 expression, leading to hydroxymethylation of p21 and p27, and stimulating melanoma cells into dormancy. 119 Cdc42 takes an action on regulating cell division and migration. The up‐regulation of Cdc42 may promote dormancy of prostate cancer cells 120 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Molecular regulatory mechanism of dormant cancer cells. Regulatory mechanisms in dormant cancer cells can be divided into two categories: intracellular and extracellular. The dormancy of cancer cells is regulated by different molecules and signalling pathways, mainly involving: P53 and cell cycle‐related proteins, TGF‐β signalling pathway, p38/MAPK signalling pathway, cell autophagy, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress signalling and Cdc42 GTPase cycle.

4. PGCCS HAVE THE PROPERTIES OF DORMANT CANCER CELLS

PGCCs possess two major characteristics of dormant cancer cells: cell cycle arrest, and high migration and invasion capabilities. PGCCs deviate from the typical G1‐S‐G2‐M cell cycle. (Table 1 shows the different terms and explanations related to cell cycle arrest in PGCCs). 121 Several studies have reported cell cycle arrest in PGCCs. 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 , 126 In current reports, terminologies related to cell cycle arrest of PGCCs include G2 cell cycle arrest, GAlert/spG0/G0 cells, arrested in the G0/G1 phase, quiescence, slow‐cycling states, dormant state and proliferative arrest. Alhaddad L et al. discussed the radioresistance related to the proportion of dormant PGCCs by the Ki‐67/EdU staining features enriching in three subpopulations (GAlert, spG0, G0). In the three subpopulations, GAlert cells are in a quiescence‐like state with moderate Ki‐67 expression, indicating that they were ready to re‐enter the cell cycle. The spG0 cells remain in a quiescent state, but with low level of Ki‐67 expression, indicating that they were in a deeper state of dormancy. G0 cells without Ki‐67 expression are fully quiescent. The GAlert, spG0, G0 states in quiescence‐ and/or senescence‐like may be an adaptive response of PGCCs to radiation stress. 127 , 128

TABLE 1.

Terminologies and explanations of their reference cell cycle arrest of PGCCs.

| Terminologies relate to cell cycle arrest of PGCCs | Explanation | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cell cycle arrest (Quiescence) | Cancer cell dormancy is a process whereby cells enter reversible cell cycle arrest (including G0/G1, G0, G1, G2 and G2/M arrest), termed quiescence. | 58 |

| Growth arrest | Cancer cell dormancy typically presents as growth arrest while retaining proliferative capacity and can be induced or reversed by a wide array of cell‐intrinsic and cell‐extrinsic factors. | 40 |

| Slow‐cycling | SCCs are a subpopulation of cancer cells that are relatively quiescent and exist in the G0/G1 cell‐cycle phase. SCCs are considered dormant cancer cells. | 129 |

| Non‐proliferation | Cellular dormancy refers to restricting proliferation at the cell level. | 130 |

| Non‐dividing | Most metastatic lesions are micro metastases that have the capacity to remain in a non‐dividing state called ‘dormancy’ for months or even years. | 131 |

| Dormant state | Dormant state is a relatively broad concept that includes various dormant cells | 131 , 132 , 133 |

Abbreviation: SCCs, slow‐cycling cells.

Mallin et al. 12 showed that PACC (PGCCs) exhibit increased motility and deformability mediated by increased mesenchymal‐related protein expression, and that PACC show increased metastatic potential. PGCCs have thicker and longer actin fibres with an abnormal overexpression of actin components compared with the diploid cancer cells, which confers PGCCs a slow yet persistent migratory phenotype. The actin network and dysregulated RhoA–ROCK1 pathway are potential mechanisms for PGCCs cytoplasmic biophysical changes. 134 A recent study reported that up‐regulation of Cdc42 and p21‐regulated kinase 1 down‐regulates stathmin and increases the protein level of phosphorylated stathmin. Phosphorylated stathmin, existed in the nucleus of PGCCs and daughter cells, promotes microtubule aggregation and regulates cytoskeletal remodelling. Cdc42 overexpression takes a part in the invasion and migration of PGCCs and daughter cells. 123 In summary, PGCCs maintain cell cycle arrest and exhibit high migration and invasion rates when dormant.

4.1. PGCCs‐related signalling pathways are consistent with the molecular characteristics of dormant cells

A previous proteomic analysis indicates that PGCCs are associated with dormancy. (1) Alteration in several cell cycle‐related proteins (FOXM1, cyclin E, cyclin D1, CDK6, checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1), cyclin A2, Checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2), S100 calcium‐binding protein A10 (S100A10), S100A6 and S100A4) may be involved in the formation of PGCCs. (2) Up‐regulation of proteins (Heat Shock Protein Family A Member 1B, Heat Shock Protein Family A Member 1A and annexin A1) protects cells from stress, whereas down‐regulation of stress‐induced phosphoprotein 1 inhibits proliferation. (3) Cell motility‐related proteins (cathepsin D, cathepsin B, vimentin, high mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1), annexin A2, integrin β2 and Ezrin) were increased in PGCCs and their daughter cells. (4) PGCCs may undergo different metabolic processes (up‐regulation of lactate dehydrogenase A and enolase 1) and are more adaptable to stress than diploid cells. 135 In summary, PGCCs share molecular characteristics and regulatory mechanisms with dormant cancer cells, including cell cycle arrest, high migratory ability and adaptation to adverse microenvironments.

4.2. PGCCs achieve dormancy through endoreplicative cell cycle

Fluorescence imaging revealed that PGCCs undergo endoreplicative cycles with alternating S and G phases, accumulating DNA and enlarging the cell/nucleus without dividing. 22 Endoreduplication is a cell‐cycle variation in which the nuclear genome replicates without mitosis, resulting in polyploidy. 136 Abnormal karyotypes and polyploid programs of PGCCs are attributed to endoreplication. 26 , 137 Aurora kinase A/B (AURKA/B), which abnormally regulates cytokinesis in PGCCs, accounts for the functional differences between normal mitosis and endoreplication in PGCCs. 138 , 139 , 140 Endoreduplication and polyploidisation are survival strategies adopted by dormant PGCCs to adapt to harsh environmental conditions. The cell cycle of PGCCs can be classified into four stages. (1) Initiation: Multiple stressors can induce endoreplicative cell cycles in cancer cells, leading to the formation of PGCCs for survival after anti‐mitotic treatments. 139 , 141 When treated with cisplatin, carboplatin or paclitaxel, the number of PGCCs (>4N) increases rapidly, while the number of diploid (2N) cancer cells decreases through apoptosis. 26 , 142 , 143 (2) Self‐renewal: Polyploid cells enter the endoreplication cell cycle via the endomitosis or endocycle, which allows tumour cells to grow in a polyploid state. 139 , 141 (3) Termination: PGCCs generate diploid cells via budding, fragmentation, fission and cytofission. PGCCs generate diploid progeny, which may be related to changes in AURKA/B. 139 , 140 (4) Stability: Diploid daughter cells have acquired new genomes and resume mitosis. 139 , 141 Study of Richards et al. 140 indicated that the explosive growth of PGCCs at day 21 coincided with a transition from slow to rapid growth in xenograft tumours. The initiation and self‐renewal stages of PGCCs are similar to the cell cycle arrest of dormant cancer cells, whereas the termination and stability stages resemble the reactivation stage.

The disruption of cell cycle checkpoints mediated by CDK is necessary for the endoreplication of PGCCs. The p16/pRb and P53/p21 pathways can regulate the expression of CDK. Severe DNA damage from chemotherapy or hypoxia induces P53 up‐regulation and cells with mutant P53 become aneuploid. 127 Endoreduplication increases the cell size, DNA content and nuclear heterogeneity in response to various stressors. 144 , 145 In PGCCs, CDK1 and cyclin B1 expression is down‐regulated, whereas the expression of P53 is up‐regulated. 124 , 126 , 146 P53 drives cells into a safer and more favourable dormant state, enhancing the adaptability and survival of PGCCs to irradiation stress. 66 , 147 The CHK1, CHK2–pCDC25C‐Ser216–cyclin B1–CDK1 and AURKA–Polo‐like kinase 1 (PLK1)–pCDC25C‐Ser198–cyclin B1–CDK1 signalling pathways are participant of PGCCs formation. 25 , 126 ataxia telangiectasia‐mutated gene (ATM)/ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3‐related (ATR)‐P53‐p21 axis induces cell dormancy and cell cycle arrest. 147 In addition, the subcellular localisation of cell cycle‐related proteins (cyclin B1, CDC25C, CDK1) is also correlated with the formation of PGCCs. 146 These proteins play crucial roles in maintaining PGCCs dormancy and in restoring cell proliferation (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Molecular regulatory mechanisms of dormant PGCCs. Cancer cells enter a dormant state and resist various stressors by maintaining a cell cycle arrest. PGCCs possess major characteristics of dormant cancer cells, including cell cycle arrest. PGCCs represent a dormant form of the stress‐induced cancer cell cycle. PGCCs‐related signalling pathways were consistent with the molecular characteristics of dormant cells. Alterations in several cell cycle‐related proteins (PLK1, AURKA/B, P53, CHK1, CHK2, Cdc42, PAK1, Stathmin, p21, ATM, ATR, p38MAPK, ERK, CDK1, cyclinB1 and CD133) may maintain PGCCs dormancy.

4.3. The endoreplicative feature endows PGCCs drug resistance

Under stress, cells respond in various ways to maintain balance. 139 , 141 Polyploidy can also be used to achieve greater functionality and independence. Polyploidy exhibit enhanced stress resistance and resist chemotherapeutic drugs (doxorubicin, vincristine, paclitaxel, etc.) at extreme doses. 18 , 121 , 134 , 138 , 139 , 148 , 149 PGCCs survive at high docetaxel concentrations and may undergo EMT to survive in regions with high drug concentrations. 150 Nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC) is an Epstein–Barr Virus (EBV)‐related squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. EBV can promote EMT in dormant PGCCs to enhance stemness. 21 The dormancy of PGCCs can be reactivated by specific signals, causing late‐stage relapse of NPC and other malignancies. 23 Continuous staurosporine treatment induces PGCCs formation and maintains quiescence in A549 cells for several months. 151

In addition, polyploidy allows short‐term metabolic changes to cope with oxidative stress. 152 Once cancer cells obtain this ability, they also have the ability to survive and respond to stress in tumour microenvironment (TME). 17 , 150 , 153 After paclitaxel causes mitotic crisis and cancer cell death, the remnant cells undergo genomic shock, activating emergency survival mechanisms. 154 Dormant cancer cells allow for energy conservation and distribution under poor environmental conditions. 155 PGCCs are rich in mitochondria, which support the survival of cancer cells by producing ATP. Adibi et al. 156 reported increased lipid droplet formation has been observed in PGCCs. Lipids likely serve as energy stores that help PGCCs endure stress. 157 The increased lipid droplets may serve as energy storage reservoirs that enable cancer cells to effectively endure long‐term stress conditions. In PGCCs‐enriched samples, glucose‐1‐phosphate and glutamine were significantly differentially abundant. 158 Increasing the volume of DNA without division during dormancy is advantageous when energy is limited or growth is rapid, allowing PGCCs to reserve more energy (lipids, proteins and carbohydrates) and survive extended periods of dormancy. 159 , 160 It also protects against toxins and oxidative stress by increasing the expression of RNA and proteins involved in protection pathways. 17 Third, polyploidy allows cell‐cycle arrest and genetic modifications with whole‐genome doubling. 17

5. REACTIVATION OF DORMANT PGCCs PROMOTES TUMOUR INVASION AND METASTASIS

Dormant PGCCs can be activated by external signals such as growth factors and cytokines. These signals promote cell proliferation, causing dormant tumour cells to re‐enter the cell cycle and initiate metastasis. 65

5.1. PGCCs exit dormancy and produce daughter cells via asymmetric division

After treatment, PGCCs require a latency period (dormancy) to restore viability and produce daughter cells. 18 The length of the dormant period depends on the chemotherapy dose and radiotherapy intensity. 11 , 125 PGCCs can exit dormancy and resume proliferation after restoring favourable conditions. Gilbertson et al. 137 described the manner of PGCCs producing progeny cells as ‘neosis’. Asymmetric division leads to the loss of genetic material in the mononuclear daughter cells, thereby increasing their genetic instability and heterogeneity. 10 Extracellular HMGB1 enhances the asymmetric division of PGCCs during tumour regrowth. Moreover, overexpression of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), p‐p38 and p‐ERK in PGCCs suggests the involvement of HMGB1/RAGE/p38 and ERK pathways in asymmetric division of PGCCs. 19 , 121 , 159 In addition, S‐phase kinase‐associated protein 2, stathmin, cyclin E, CDK2, cyclin B1, p‐AKT, phosphoglycerate kinase 1, protein kinase C, p38 and MAPK are also up‐regulated in daughter cells produced by PGCCs via asymmetric division. 161

Acid ceramidase (ASAH1) is a lysosomal enzyme that plays an essential role in the survival of PGCCs by hydrolysing ceramide to sphingosine. This enables the PGCCs to produce progeny via lysosome‐mediated cell division. 137 High levels of C16‐ceramide inhibit PGCCs progeny formation. However, this inhibition can be prevented by inhibiting ASAH1 or by expressing functional P53. In contrast, P53 loss and low C16 ceramide levels, due to altered sphingolipid metabolism, promote PGCCs progeny formation. 162

5.2. PGCCs‐derived daughter cells have strong abilities of proliferation, migration and invasion

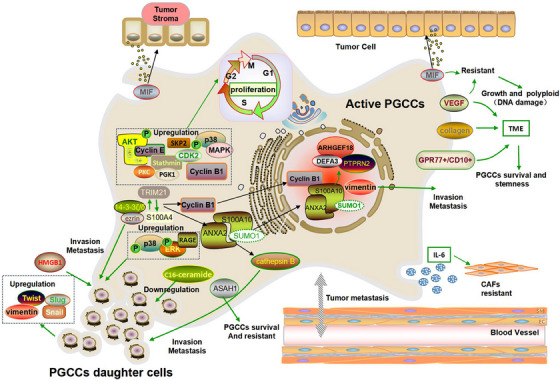

The highly invasive and migratory characteristics of PGCCs‐derived daughter cells have been demonstrated in many studies. 24 , 123 , 134 , 149 , 163 , 164 , 165 , 166 PGCCs‐derived daughter cells can easily metastasize to the lymph nodes or distant organs by expressing EMT‐related proteins (Snail, Slug and Twist). 167 Ezrin, S100A4 and 14‐3‐3ζ/δ are involved in the migration and invasion of PGCCs‐derived daughter cells via cytoskeletal constructions. 165 The nuclear localisation of S100A10 modified by SUMOylation is associated with the high proliferation and migration of PGCCs‐derived daughter cells by regulating the expression of neutrophil defensin 3, receptor‐type tyrosine‐protein phosphatase N2 and rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 18. 164 PGCCs‐derived daughter cells express high levels of vimentin which enhances the migration and invasion. 24 P62‐dependent SUMOylation of vimentin locates in the nuclear and acts as a transcription factor that regulates Cdc42, cathepsin B and cathepsin D to promote PGCCs‐derived daughter cells invasion and migration 168 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

PGCCs dormancy and activation pattern diagram. PGCCs achieve dormancy via an endoreplicative cell cycle. Endoreduplication is a cell‐cycle variation in which the nuclear genome replicates without mitosis, resulting in polyploidy. The abnormal karyotype and polyploidy of PGCCs have been attributed to endoreplication. Polyploid cells continue their endoreplicative cell cycle through endocycles or endomitosis, generating mono‐ and multi‐nucleated PGCCs. PGCCs retain their proliferative potential during dormancy and stimulate tumour cell proliferation through asymmetric division. Active PGCCs, dormant PGCCs is reactivated and re‐enter cell cycle via asymmetric cell division.

5.3. Cross‐talk between cytokines and PGCCs

Crosstalk between cytokines and PGCCs plays a critical role in cancer progression. Growth factors and cytokines derived from PGCCs, including macrophage migration inhibitory factors (MIF) and VEGF, can promote resistance to chemotherapy. 169 , 170 MIF derived from PGCCs may allow cancer cells to grow and proliferate. Ahmad et al. 171 reported a relationship between high‐risk human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) strains, PGCCs and cytokines in breast cancer. Both TGF‐β and IL‐6 can activate signalling pathways in EMT and drive cancer progression. HCMV may utilise cytokines like IL‐10 and TGF‐β to create a tumour‐supportive microenvironment and modulate pathways controlling PGCCs formation and their stem‐like properties. 171 In addition, paclitaxel treatment can induce an ‘inflammatory storm’ dominated by IL‐6 production during PGCCs formation. IL‐6 acts in an autocrine manner to facilitate the acquisition of stemness properties and survival of PGCCs. The PGCCs‐derived IL‐6 stimulates fibroblasts to increase collagen production, enrichment of the GPR77+/CD10+ cancer‐associated fibroblasts (CAFs) subpopulation and VEGF expression. 26 , 172 PGCCs also utilise IL‐6 as a paracrine molecule to reprogram normal fibroblasts into CAFs. Reprogrammed CAFs maintained PGCCs stemness, promoted angiogenesis and metastasis and modified the TME to favour the survival of PGCCs after chemotherapeutic drug treatment. 172 PGCCs can increase the cell‐cell interactions with surrounding cancer cells. They express high levels of surface markers such as N‐cadherin, and OB‐cadherins, as well as integrin alpha 5 and fibronectin, which likely contribute to their interactions with other cells in the TME 173 (Figure 4 and Table 2).

FIGURE 4.

Reactivation of dormant PGCCs via asymmetric division promotes tumour invasion and metastasis. PGCCs retain their proliferative potential during dormancy and stimulate tumour cell proliferation through asymmetric division to produce daughter cells. PGCCs can exit dormancy and recur, thereby generating aggressive diploid progeny. Daughter cells exhibited EMT features as well as high invasion and migration capabilities. Tumour microenvironment (TME) is a dynamic network of diploid cells, PGCCs, daughter cells, stromal cells, blood vessels and vasculogenic mimics. PGCCs can be activated by external signals such as growth factors and cytokines. These signals promote cell proliferation, causing dormant PGCCs to re‐enter the cell cycle and initiate metastasis.

TABLE 2.

Main similarities and differences between dormant PGCCs and cancer cells.

| Feature | Dormant PGCCs | Dormant cancer cells |

|---|---|---|

| Same point | ||

| Origin | Response to stress, including chemotherapy, ionising radiation and hypoxia 170 | Due to hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, immune surveillance and chemotherapy 82 |

| Cell cycle status | Static 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 174 | Cell cycle arrest in the G0 or G1 phase 175 |

| Proliferative arrest 25 | Growth arrest 58 | |

| Arrested in the G0/G1 phase 26 | ||

| Drug resistance | Prevent the toxic effects of systemic therapy 19 | Driving treatment resistance 118 |

| Proliferation | Asymmetric division (neosis) 15 | Reactivate to promote cell proliferation 175 |

| Recurrence and metastasis | Driving recurrence and promote metastasis 162 | Re‐enter the cell cycle and initiate the metastasis 65 |

| Microenvironmental signals | Adaptable to the harsh microenvironments 135 | Adaptation to tumour microenvironment of tumour hypoxia and nutrient limitation 176 |

| Unique characteristics of PGCCs | ||

| Stemness and differentiation | Characteristics of stem cells, such as self‐renewal and differentiation ability 18 , 157 | |

| Expression of the embryonic stem cell markers OCT4, NANOG, SOX2 and SSEA1 138 | ||

| Can differentiate into adipose, cartilage and bone 18 | ||

| Express embryonic haemoglobin with strong oxygen binding ability, promoting survival of tumour cells in a hypoxic microenvironment 20 | ||

| Nuclear heterogeneity | PGCCs have single giant or multiple nuclei. Multinuclear PGCCs are more likely to be produced when nuclear replication and separation are completed, and cytoplasmic separation fails. Single giant nuclear PGCCs would appear if both nuclear and cytoplasmic separation fails at the same time. 15 , 16 , 17 | |

| EMT | Daughter cells derived from PGCCs undergo EMT phenotype changes 149 , 177 | |

| Cell division mode | Asymmetric division 135 | |

6. POTENTIAL THERAPEUTIC STRATEGY FOR TARGETING PGCCs

In clinical practice, most chemotherapeutic drugs are designed to disrupt mitosis and rapidly divide the cancer cells. Common antimitotic drugs such as aclitaxel, docetaxel, vinorelbine, vinblastine, the PLK1 inhibitor BI‐6727 (Volasertib), CENPE inhibitor (GSK923295), EG5 inhibitors (Ispinesib) and VS‐83, inhibit tumour cell growth and division by interfering with mitosis. 178 However, PGCCs is resistant to antimitotic drugs. Moreover, these drugs can damage normal tissues, leading to nephrotoxicity, bone marrow suppression and peripheral neuropathy. 179 Currently, drugs targeting PGCCs are still in preclinical stages. The development of drugs targeting PGCCs may be an important strategy for reducing the occurrence of drug‐resistant progeny. Small molecular chemical reagents targeting PGCCs including: (1) reduced the number of PGCCs (mTOR inhibitor and poly ADP ribose polymerase [PARP] inhibitor, hydroxychloroquine, nelfinavir, rapamycin, paclitaxel and ganciclovir). In tumours with cyclin E1 amplification, PGCCs highly expressed CHK2 and co‐stained with the DNA damage marker, gamma histone H2AX, indicating that these proteins take part in maintaining the survival of PGCCs. Dual treatment with an mTOR inhibitor and a PARP inhibitor significantly reduced the number of PGCCs. 180 Two autophagy inhibitors, hydroxychloroquine and nelfinavir, reduced the number of progeny generated from PGCCs in high‐grade serous carcinoma (HGSC), thereby inhibiting their growth and proliferation, which prevents PGCCs from repopulating tumours. Rapamycin also prevented PGCCs colony outgrowth. Clinical trials using hydroxychloroquine, nelfinavir and/or rapamycin after chemotherapy may be important for targeting PGCCs. 181 Attempts to reduce the number and proliferation of PGCCs and limit their formation using paclitaxel and ganciclovir have shown some effectiveness. However, the efficacy of the drug combinations may vary depending on the cell line used. 157 (2) Prevented formation of PGCCs (tocilizumab, apigenin, mifepristone and PARP inhibitors, BML‐275, PRL3‐zumab). Tocilizumab and Apigenin block IL‐6 and reduce PGCCs formation, thereby inhibiting tumour growth. 172 Zhang et al. 22 targeted PGCCs in ovarian cancer and found that mifepristone could synergistically work with PARP inhibitors to promote apoptosis of cells undergoing endoreplication, thereby blocking PGCCs formation and enhancing the therapeutic effect of PARP inhibitors. Chemotherapy can induce nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells to form dormant PGCCs. Use of the autophagy inhibitor BML‐275, an AMP‐activated protein kinase inhibitor, before chemotherapy can prevent PGCCs formation and reduce nasopharyngeal carcinoma relapse and metastasis. 23 Overexpression of phosphatase in regenerating liver 3 (PRL3) in PGCCs causes abnormal cell division. PRL3+ PGCCs can tolerate the genotoxic stress induced by chemotherapy by inhibiting the ATM DNA damage signalling pathway, which increases their survival and drug resistance. PRL3‐zumab is a humanised antibody that targets the PRL3 oncogene and reduces tumour metastasis and recurrence by targeting PRL3+ PGCCs. PRL3‐zumab is considered a potential ‘adjuvant immunotherapy’ that can be used after tumour removal surgery to eliminate PRL3+ PGCCs and prevent tumour metastasis and recurrence. 182 IL‐1β is involved in regulating the resistance of docetaxel chemotherapy, which is achieved by regulating the formation of PGCCs. Thus, treatments targeting IL‐1β may help improve the efficacy of chemotherapy drugs by reducing the formation of PGCCs. 122 (3) Reduced lipid droplets and cholesterol levels in PGCCs. Zoledronic acid (ZA) is used to treat various cancers, including breast, bladder, renal and lung. PGCCs undergo changes in lipid metabolism, thereby increasing lipid droplets and cholesterol levels. Lipids serve as energy storage agents, enabling cancer cells to endure long‐term stressful conditions. ZA significantly reduced lipid droplets and cholesterol levels in PGCCs. This indicates that targeting lipid metabolism in PGCCs may represent a promising strategy for overcoming chemoresistance and improving the success rate of cancer treatment. 156 (4) Induced‐differentiation. PGCCs cultured in medium containing 3‐isobutyl‐1‐methylxanthine, insulin, dexamethasone and rosiglitazone can be induced to transdifferentiate into mature functional adipocytes. Ishay‐Ronen et al. 183 reported that invasive and metastatic breast cancer cells can be differentiated into adipocytes by MEK inhibitors and rosiglitazone, and invasion and metastasis abilities were inhibited in breast cancer (Tables 3 and 4).

TABLE 3.

Published literature about PGCCs across different cancer types.

| Cancer type | Cell lines | Chemical reagents | The roles of PGCCs in cancer | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian cancer | High‐grade serous carcinoma and MDA‐HGSC‐1 (patient source), HEY, SKOv3, OVCAR3, CAOV3, IGROV1, OVCA‐432, OVCAR8, OVCAR5, PEO‐1, A2780, SCOV‐3, NIHOVCAR3, COV318, OVCAR4 | Paclitaxel, cobalt chloride, triptolide, HA15 (Selleckchem, Zurich, Switzerland), thapsigargin (Enzo LifeSciences, Lausen, Switzerland), tunicamycin (Enzo LifeSciences), carboplatin, docetaxel, olaparib, cisplatin, mTOR inhibitor |

Associated with poor prognosis Chemoresistance and cancer stem cell characteristics Promote invasion and migration. Contributes to the evolution and remodelling of cancer Associated with the formation of vasculogenic mimics |

18 , 22 , 25 , 126 , 138 , 139 , 161 , 166 , 172 , 180 , 181 , 184 , 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 |

| Breast cancer | MCF‐7, MDA‐MB‐231, MDA‐MB‐453, SKBR‐3, BT‐549, 4T1, HMECs | Cisplatin, docetaxel, cobalt chloride, triptolide, irradiation, human cytomegalovirus, paclitaxel, olaparib |

Chemoresistance Promote invasion, metastatic dissemination and migration Cancer stem cells characteristics Associated with the malignant grade of breast tumour |

10 , 18 , 19 , 24 , 25 , 126 , 149 , 156 , 157 , 158 , 171 , 189 , 190 , 191 |

| Colorectal cancer | LoVo, HCT116, Caco‐2 | Cobalt chloride, arsenic trioxide, capecitabine, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, irradiation |

Daughter cells derived from PGCCs have strong proliferation, invasion and migration abilities Contributed to expansion of a cell subpopulation with cancer stem cells characteristics Associated with the differentiation of colorectal cancer Associated with the formation of vasculogenic mimics Chemoresistance |

11 , 20 , 121 , 164 , 165 , 168 , 177 , 192 , 193 , 194 , 195 |

| Glioma | A172, C6, U251, Hs683 | Cobalt chloride, paclitaxel, puromycin |

Enhanced the polarisation of tumour‐associated macrophages into an M2 phenotype with relevance to immunosuppression and malignancy in GBM Associated with the formation of vasculogenic mimics, as well as the malignancy and prognosis of tumours Enhanced temozolomide resistance |

15 , 166 , 196 , 197 |

| Lung cancer | A549, H1299, NSCLC, HBEC | Docetaxel, staurosporine, SB 328437, SB 297006 (CCR3 antagonists), aurora kinase inhibitors |

Chemoresistance Enhanced migration and proliferation abilities Promote the recurrence |

122 , 178 , 193 |

| Prostatic cancer | PC3, PPC1 | PRL3 overexpression induction, cisplatin, docetaxel, irradiated | Promote the recurrence and metastasis | 12 , 137 , 182 |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | 5–8F, CNE2, C666‐1 | Paclitaxel |

Correlate with the recurrence and metastases of NPC EBV promotes VM formation by PGCCs in vitro and in vivo which correlates with the growth of NPC cells |

21 , 23 |

| Laryngeal cancer | TU212 | Paclitaxe | Associated with poor prognosis of patients | 143 |

| Prostate cancer | Prostate epithelial cells infected by human cytomegalovirus | Human cytomegalovirus | PGCCs with the poor prognosis of prostate cancer | 198 |

| Leukaemia | K562 | 5‐Azacytidine | Resistant to chemotherapeutic agent and serum starvation stress | 159 |

| Oral cancer | Cal33, FaDu | Cisplatin | Chemoresistance | 199 |

TABLE 4.

Current/proposed therapies that may inhibit the formation of PGCCs.

| Current/proposed therapies for PGCCs | Mechanisms | Advantages | Disadvantages | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combination therapies | ||||

| mTOR inhibitor and PARP inhibitor |

Inhibiting the mTOR signalling pathway Blocking the activity of PARP enzymes |

Reduced the number of PGCCs | Not reported | 180 |

| Mifepristone and PARP inhibitors |

Mifepristone promotes apoptosis of cells undergoing endoreplication. PARP inhibitors target the DNA repair pathway in cancer cells |

Blocking PGCCs formation and enhancing the therapeutic effect of PARP inhibitors | 22 | |

| Paclitaxel and Ganciclovir | Inhibit tumour cell mitosis and induce cell apoptosis; inhibit virus growth and replication | Reduce the number and proliferation of PGCCs | The therapeutic efficacy may vary depending on different cell lines | 157 |

| Autophagy inhibitors | ||||

| Hydroxychloroquine, rapamycin, nelfinavir | Regulatory autophagy | Reduced the number of PGCCs | Not reported | 181 |

| BML‐275 | AMP‐activated protein kinase inhibitor | Prevent PGCCs formation and reduce nasopharyngeal carcinoma relapse and metastasis | 23 | |

| Induced differentiation | ||||

| 3‐Isobutyl‐1‐methylxanthine + insulin+ dexamethasone+ rosiglitazone | PGCCs can be induced to transdifferentiate into mature functional adipocytes | Not reported | 124 , 183 | |

| Other therapies | ||||

| Tocilizumab, apigenin | Block interleukin‐6 | Reduce PGCCs formation | Not reported | 172 |

| PRL3‐zumab | Targets the PRL3 oncogene | Eliminate PRL3+ PGCCs and prevent tumour metastasis and recurrence | 182 | |

| Zoledronic acid | Induce apoptosis of osteoclasts | Reduced lipid droplets and cholesterol levels in PGCCs | 156 | |

7. CONCLUSION

PGCCs have emerged as key regulators of tumour dormancy and reactivation. Abnormal cell cycle regulation in PGCCs enables them to enter a reversibly dormant state and evade cancer therapy. Specifically, PGCCs achieve dormancy through endoreduplication cycles mediated by CDK inhibitors and tumour suppressors like P53. Polyploidy allows PGCCs to increase their DNA content and cell size, thereby enhancing their resistance to stress. Furthermore, PGCCs can exit dormancy and recur via asymmetric division, thereby generating aggressive diploid progeny. Daughter cells exhibit EMT features, as well as high invasion and migration capabilities. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms underlying PGCCs dormancy and reawakening holds great promise for the better management of tumour recurrence, metastasis and drug resistance. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the complex molecular events driving PGCCs behaviour. Developing clinical interventions targeting PGCCs survival and division may help to overcome cancer relapse after therapy .

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Writing – original draft: Yuqi Jiao. Writing – original draft: Yongjun Yu. Writing – review and editing: Minying Zheng. Writing – review and editing: Man Yan. Writing – review and editing: Jiangping Wang. Conceptualisation and Supervision: Yue Zhang. Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing: Shiwu Zhang. All authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in this work to take public responsibility for the content. All authors have read the journal's authorship agreement, reviewed and approved the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not Applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge Editage for the language editing of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (#82173283 and #82103088), the Foundation of the committee on science and technology of Tianjin (#21JCZDJC00230 and 21JCYBJC00190) and 2021 Annual Graduate Students Innovation Fund, School of Integrative Medicine, Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin, China (#ZXYCXLX202105).

Jiao Y, Yu Y, Zheng M, et al. Dormant cancer cells and polyploid giant cancer cells: The roots of cancer recurrence and metastasis. Clin Transl Med. 2024;14:e1567. 10.1002/ctm2.1567

Yuqi Jiao and Yongjun Yu equally contributed to this paper.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not available.

REFERENCES

- 1. Willis RA. The Spread of Tumours in the Human Body. London, J. & A. Chuchill; 1934. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hadfield G. The dormant cancer cell. Br Med J. 1954;2(4888):607‐610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saad N, Alberio R, Johnson AD, et al. Cancer reversion with oocyte extracts is mediated by cell cycle arrest and induction of tumour dormancy. Oncotarget. 2018;9(22):16008‐16027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vitetta ES, Tucker TF, Racila E, et al. Tumor dormancy and cell signaling. V. Regrowth of the BCL1 tumor after dormancy is established. Blood. 1997;89(12):4425‐4436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guo F, Yuan D, Zhang J, et al. Silencing of ARL14 gene induces lung adenocarcinoma cells to a dormant state. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019;7:238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baldominos P, Barbera‐Mourelle A, Barreiro O, et al. Quiescent cancer cells resist T cell attack by forming an immunosuppressive niche. Cell. 2022;185(10):1694‐1708. e1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lawson MA, McDonald MM, Kovacic N, et al. Osteoclasts control reactivation of dormant myeloma cells by remodelling the endosteal niche. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fane ME, Chhabra Y, Alicea GM, et al. Stromal changes in the aged lung induce an emergence from melanoma dormancy. Nature. 2022;606(7913):396‐405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perego M, Tyurin VA, Tyurina YY, et al. Reactivation of dormant tumor cells by modified lipids derived from stress‐activated neutrophils. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(572):eabb5817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang S, Mercado‐Uribe I, Liu J: Generation of erythroid cells from fibroblasts and cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2013;333(2):205‐212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fei F, Zhang M, Li B, et al. Formation of polyploid giant cancer cells involves in the prognostic value of neoadjuvant chemoradiation in locally advanced rectal cancer. J Oncol. 2019;2019:2316436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mallin MM, Kim N, Choudhury MI, et al. Cells in the polyaneuploid cancer cell (PACC) state have increased metastatic potential. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2023;40(4):321‐338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mirzayans R, Andrais B, Scott A, Wang YW, Kumar P, Murray D. Multinucleated giant cancer cells produced in response to ionizing radiation retain viability and replicate their genome. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2):360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adams DL, Martin SS, Alpaugh RK, et al. Circulating giant macrophages as a potential biomarker of solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(9):3514‐3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu Y, Shi Y, Wu M, et al. Hypoxia‐induced polypoid giant cancer cells in glioma promote the transformation of tumor‐associated macrophages to a tumor‐supportive phenotype. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2022;28(9):1326‐1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. White‐Gilbertson S, Voelkel‐Johnson C. Giants and monsters: Unexpected characters in the story of cancer recurrence. Adv Cancer Res. 2020;148:201‐232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pienta KJ, Hammarlund EU, Brown JS, Amend SR, Axelrod RM. Cancer recurrence and lethality are enabled by enhanced survival and reversible cell cycle arrest of polyaneuploid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118(7):e2020838118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang S, Mercado‐Uribe I, Xing Z, Sun B, Kuang J, Liu J. Generation of cancer stem‐like cells through the formation of polyploid giant cancer cells. Oncogene. 2014;33(1):116‐128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang Z, Feng X, Deng Z, et al. Irradiation‐induced polyploid giant cancer cells are involved in tumor cell repopulation via neosis. Mol Oncol. 2021;15(8):2219‐2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li Z, Zheng M, Zhang H, et al. Arsenic trioxide promotes tumor progression by inducing the formation of PGCCs and embryonic hemoglobin in colon cancer cells. Front Oncol. 2021;11:720814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheng T, Zhang S, Xia T, et al. EBV promotes vascular mimicry of dormant cancer cells by potentiating stemness and EMT. Exp Cell Res. 2022;421(2):113403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang X, Yao J, Li X, et al. Targeting polyploid giant cancer cells potentiates a therapeutic response and overcomes resistance to PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer. Sci Adv. 2023;9(29):eadf7195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. You B, Xia T, Gu M, et al. AMPK‐mTOR‐mediated activation of autophagy promotes formation of dormant polyploid giant cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2022;82(5):846‐858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xuan B, Ghosh D, Jiang J, Shao R, Dawson MR. Vimentin filaments drive migratory persistence in polyploidal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(43):26756‐26765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu K, Lu R, Zhao Q, et al. Association and clinicopathologic significance of p38MAPK‐ERK‐JNK‐CDC25C with polyploid giant cancer cell formation. Med Oncol. 2019;37(1):6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen J, Niu N, Zhang J, et al. Polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs): the evil roots of cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2019;19(5):360‐367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Braune EB, Tsoi YL, Phoon YP, et al. Loss of CSL unlocks a hypoxic response and enhanced tumor growth potential in breast cancer cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2016;6(5):643‐651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rhodes A, Hillen T. Implications of immune‐mediated metastatic growth on metastatic dormancy, blow‐up, early detection, and treatment. J Math Biol. 2020;81(3):799‐843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kareva I. Primary and metastatic tumor dormancy as a result of population heterogeneity. Biol Direct. 2016;11(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wheeler SE, Clark AM, Taylor DP, et al. Spontaneous dormancy of metastatic breast cancer cells in an all human liver microphysiologic system. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(12):2342‐2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hosseini H, Obradovic MMS, Hoffmann M, et al. Early dissemination seeds metastasis in breast cancer. Nature. 2016;540(7634):552‐558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Borgen E, Rypdal MC, Sosa MS, et al. NR2F1 stratifies dormant disseminated tumor cells in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matson JP, House AM, Grant GD, Wu H, Perez J, Cook JG. Intrinsic checkpoint deficiency during cell cycle re‐entry from quiescence. J Cell Biol. 2019;218(7):2169‐2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Coller HA, Sang L, Roberts JM. A new description of cellular quiescence. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(3):e83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nobre AR, Risson E, Singh DK, et al. Bone marrow NG2(+)/Nestin(+) mesenchymal stem cells drive DTC dormancy via TGFbeta2. Nat Cancer. 2021;2(3):327‐339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang L, Peng Q, Xie Y, et al. Cell‐cell contact‐driven EphB1 cis‐ and trans‐ signalings regulate cancer stem cells enrichment after chemotherapy. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(11):980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Murayama T, Takeuchi Y, Yamawaki K, et al. MCM10 compensates for Myc‐induced DNA replication stress in breast cancer stem‐like cells. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(3):1209‐1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saijoh S, Nakamura‐Shima M, Shibuya‐Takahashi R, et al. Discovery of a chemical compound that suppresses expression of BEX2, a dormant cancer stem cell‐related protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;537:132‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Trotter TN, Dagotto CE, Serra D, et al. Dormant tumors circumvent tumor‐specific adaptive immunity by establishing a Treg‐dominated niche via DKK3. JCI Insight. 2023;8(22):e174458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Damen MPF, van Rheenen J, Scheele C. Targeting dormant tumor cells to prevent cancer recurrence. FEBS J. 2021;288(21):6286‐6303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Townson JL, Chambers AF. Dormancy of solitary metastatic cells. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(16):1744‐1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Massague J, Obenauf AC. Metastatic colonization by circulating tumour cells. Nature. 2016;529(7586):298‐306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1423‐1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bravo‐Cordero JJ, Hodgson L, Condeelis J. Directed cell invasion and migration during metastasis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24(2):277‐283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sosa MS, Parikh F, Maia AG, et al. NR2F1 controls tumour cell dormancy via SOX9‐ and RARbeta‐driven quiescence programmes. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nobre AR, Dalla E, Yang J, et al. ZFP281 drives a mesenchymal‐like dormancy program in early disseminated breast cancer cells that prevents metastatic outgrowth in the lung. Nat Cancer. 2022;3(10):1165‐1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mukherjee A, Bravo‐Cordero JJ. Regulation of dormancy during tumor dissemination: the role of the ECM. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023;42(1):99‐112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liu Y, Zhang P, Wu Q, et al. Long non‐coding RNA NR2F1‐AS1 induces breast cancer lung metastatic dormancy by regulating NR2F1 and DeltaNp63. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sun D, Singh DK, Carcamo S, et al. MacroH2A impedes metastatic growth by enforcing a discrete dormancy program in disseminated cancer cells. Sci Adv. 2022;8(48):eabo0876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lim PK, Bliss SA, Patel SA, et al. Gap junction‐mediated import of microRNA from bone marrow stromal cells can elicit cell cycle quiescence in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71(5):1550‐1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Han Y, Villarreal‐Ponce A, Gutierrez G, Jr. , et al. Coordinate control of basal epithelial cell fate and stem cell maintenance by core EMT transcription factor Zeb1. Cell Rep. 2022;38(2):110240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dai Y, Wang L, Tang J, et al. Activation of anaphase‐promoting complex by p53 induces a state of dormancy in cancer cells against chemotherapeutic stress. Oncotarget. 2016;7(18):25478‐25492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Meng X, Xiao W, Sun J, et al. CircPTK2/PABPC1/SETDB1 axis promotes EMT‐mediated tumor metastasis and gemcitabine resistance in bladder cancer. Cancer Lett. 2023;554:216023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dou R, Liu K, Yang C, et al. EMT‐cancer cells‐derived exosomal miR‐27b‐3p promotes circulating tumour cells‐mediated metastasis by modulating vascular permeability in colorectal cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11(12):e595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tejero R, Huang Y, Katsyv I, et al. Gene signatures of quiescent glioblastoma cells reveal mesenchymal shift and interactions with niche microenvironment. EBioMedicine. 2019;42:252‐269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Correia AL, Guimaraes JC, Auf der Maur P, et al. Hepatic stellate cells suppress NK cell‐sustained breast cancer dormancy. Nature. 2021;594(7864):566‐571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lenk L, Pein M, Will O, et al. The hepatic microenvironment essentially determines tumor cell dormancy and metastatic outgrowth of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2017;7(1):e1368603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Recasens A, Munoz L. Targeting cancer cell dormancy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019;40(2):128‐141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fox DB, Garcia NMG, McKinney BJ, et al. NRF2 activation promotes the recurrence of dormant tumour cells through regulation of redox and nucleotide metabolism. Nat Metab. 2020;2(4):318‐334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kutay M, Gozuacik D, Cakir T. Cancer recurrence and omics: metabolic signatures of cancer dormancy revealed by transcriptome mapping of genome‐scale networks. OMICS. 2022;26(5):270‐279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Brunel A, Hombourger S, Barthout E, et al. Autophagy inhibition reinforces stemness together with exit from dormancy of polydisperse glioblastoma stem cells. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13(14):18106‐18130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bakhshandeh S, Werner C, Fratzl P, Cipitria A. Microenvironment‐mediated cancer dormancy: Insights from metastability theory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119(1):e2111046118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chernosky NM, Tamagno I. The role of the innate immune system in cancer dormancy and relapse. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(22):5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhu X, Wang F, Wu X, et al. FBX8 promotes metastatic dormancy of colorectal cancer in liver. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(8):622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Weston WA, Barr AR. A cell cycle centric view of tumour dormancy. Br J Cancer. 2023;129(10):1535‐1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pustovalova M, Blokhina T, Alhaddad L, et al. CD44+ and CD133+ non‐small cell lung cancer cells exhibit DNA damage response pathways and dormant polyploid giant cancer cell enrichment relating to their p53 status. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):4922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pellicano F, Scott MT, Helgason GV, et al. The antiproliferative activity of kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia cells is mediated by FOXO transcription factors. Stem Cells. 2014;32(9):2324‐2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dhimolea E, de Matos Simoes R, Kansara D, et al. An embryonic diapause‐like adaptation with suppressed Myc activity enables tumor treatment persistence. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(2):240‐256. e211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. La T, Chen S, Guo T, et al. Visualization of endogenous p27 and Ki67 reveals the importance of a c‐Myc‐driven metabolic switch in promoting survival of quiescent cancer cells. Theranostics. 2021;11(19):9605‐9622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wu R, Roy AM, Tokumaru Y, et al. NR2F1, a tumor dormancy marker, is expressed predominantly in cancer‐associated fibroblasts and is associated with suppressed breast cancer cell proliferation. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(12):2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Haldar R, Berger LS, Rossenne E, et al. Perioperative escape from dormancy of spontaneous micro‐metastases: A role for malignant secretion of IL‐6, IL‐8, and VEGF, through adrenergic and prostaglandin signaling. Brain Behav Immun. 2023;109:175‐187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. O'Reilly MS, Holmgren L, Chen C, Folkman J. Angiostatin induces and sustains dormancy of human primary tumors in mice. Nat Med. 1996;2(6):689‐692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Katayama N, Clark SC, Ogawa M. Growth factor requirement for survival in cell‐cycle dormancy of primitive murine lymphohematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 1993;81(3):610‐616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Qiu Y, Qiu S, Deng L, et al. Biomaterial 3D collagen I gel culture model: A novel approach to investigate tumorigenesis and dormancy of bladder cancer cells induced by tumor microenvironment. Biomaterials. 2020;256:120217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Decker AM, Decker JT, Jung Y, et al. Adrenergic blockade promotes maintenance of dormancy in prostate cancer through upregulation of GAS6. Transl Oncol. 2020;13(7):100781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Clements ME, Holtslander L, Edwards C, et al. HDAC inhibitors induce LIFR expression and promote a dormancy phenotype in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2021;40(34):5314‐5326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Tivari S, Lu H, Dasgupta T, De Lorenzo MS, Wieder R. Reawakening of dormant estrogen‐dependent human breast cancer cells by bone marrow stroma secretory senescence. Cell Commun Signal. 2018;16(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rajbhandari N, Lin WC, Wehde BL, Triplett AA, Wagner KU. Autocrine IGF1 signaling mediates pancreatic tumor cell dormancy in the absence of oncogenic drivers. Cell Rep. 2017;18(9):2243‐2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Winkler IG, Barbier V, Nowlan B, et al. Vascular niche E‐selectin regulates hematopoietic stem cell dormancy, self renewal and chemoresistance. Nat Med. 2012;18(11):1651‐1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kobayashi A, Okuda H, Xing F, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 7 in dormancy and metastasis of prostate cancer stem‐like cells in bone. J Exp Med. 2011;208(13):2641‐2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Guereno M, Delgado Pastore M, Lugones AC, et al. Glypican‐3 (GPC3) inhibits metastasis development promoting dormancy in breast cancer cells by p38 MAPK pathway activation. Eur J Cell Biol. 2020;99(6):151096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Soureas K, Papadimitriou MA, Panoutsopoulou K, Pilala KM, Scorilas A, Avgeris M. Cancer quiescence: non‐coding RNAs in the spotlight. Trends Mol Med. 2023;29(10):843‐858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nagayama Y, Shigematsu K, Namba H, Zeki K, Yamashita S, Niwa M. Inhibition of angiogenesis and tumorigenesis, and induction of dormancy by p53 in a p53‐null thyroid carcinoma cell line in vivo. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(4):2723‐2728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Holmgren L, Jackson G, Arbiser J. p53 induces angiogenesis‐restricted dormancy in a mouse fibrosarcoma. Oncogene. 1998;17(7):819‐824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Itahana K, Dimri GP, Hara E, et al. A role for p53 in maintaining and establishing the quiescence growth arrest in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(20):18206‐18214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. La T, Liu GZ, Farrelly M, et al. A p53‐responsive miRNA network promotes cancer cell quiescence. Cancer Res. 2018;78(23):6666‐6679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Roberson RS, Kussick SJ, Vallieres E, Chen SY, Wu DY. Escape from therapy‐induced accelerated cellular senescence in p53‐null lung cancer cells and in human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 2005;65(7):2795‐2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yu‐Lee LY, Yu G, Lee YC, et al. Osteoblast‐secreted factors mediate dormancy of metastatic prostate cancer in the bone via activation of the TGFbetaRIII‐p38MAPK‐pS249/T252RB pathway. Cancer Res. 2018;78(11):2911‐2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Sailo BL, Banik K, Girisa S, et al. FBXW7 in cancer: what has been unraveled thus far? Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(2):246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Bragado P, Estrada Y, Parikh F, et al. TGF‐beta2 dictates disseminated tumour cell fate in target organs through TGF‐beta‐RIII and p38alpha/beta signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(11):1351‐1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Prunier C, Baker D, Ten Dijke P, Ritsma L. TGF‐beta family signaling pathways in cellular dormancy. Trends Cancer. 2019;5(1):66‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Salm SN, Burger PE, Coetzee S, Goto K, Moscatelli D, Wilson EL. TGF‐beta maintains dormancy of prostatic stem cells in the proximal region of ducts. J Cell Biol. 2005;170(1):81‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Singh DK, Carcamo S, Farias EF, et al. 5‐Azacytidine‐ and retinoic‐acid‐induced reprogramming of DCCs into dormancy suppresses metastasis via restored TGF‐beta‐SMAD4 signaling. Cell Rep. 2023;42(6):112560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Mao W, Peters HL, Sutton MN, et al. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor, interleukin 8, and insulinlike growth factor in sustaining autophagic DIRAS3‐induced dormant ovarian cancer xenografts. Cancer. 2019;125(8):1267‐1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Li B, Huang Y, Ming H, Nice EC, Xuan R, Huang C. Redox control of the dormant cancer cell life cycle. Cells. 2021;10(10):2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Barney LE, Hall CL, Schwartz AD, et al. Tumor cell‐organized fibronectin maintenance of a dormant breast cancer population. Sci Adv. 2020;6(11):eaaz4157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Padua D, Zhang XH, Wang Q, et al. TGFbeta primes breast tumors for lung metastasis seeding through angiopoietin‐like 4. Cell. 2008;133(1):66‐77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hu J, Sanchez‐Rivera FJ, Wang Z, et al. STING inhibits the reactivation of dormant metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2023;616(7958):806‐813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Sharma S, Xing F, Liu Y, et al. Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) mediates metastatic dormancy of prostate cancer in bone. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(37):19351‐19363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Sharma S, Pei X, Xing F, et al. Regucalcin promotes dormancy of prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2021;40(5):1012‐1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Aguirre‐Ghiso JA, Liu D, Mignatti A, Kovalski K, Ossowski L. Urokinase receptor and fibronectin regulate the ERK(MAPK) to p38(MAPK) activity ratios that determine carcinoma cell proliferation or dormancy in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12(4):863‐879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Keeratichamroen S, Lirdprapamongkol K, Svasti J. Mechanism of ECM‐induced dormancy and chemoresistance in A549 human lung carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2018;39(4):1765‐1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Sunderland A, Williams J, Andreou T, et al. Biglycan and reduced glycolysis are associated with breast cancer cell dormancy in the brain. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1191980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Valcourt JR, Lemons JM, Haley EM, Kojima M, Demuren OO, Coller HA. Staying alive: metabolic adaptations to quiescence. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(9):1680‐1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Ameri K, Jahangiri A, Rajah AM, et al. HIGD1A regulates oxygen consumption, ROS production, and AMPK activity during glucose deprivation to modulate cell survival and tumor growth. Cell Rep. 2015;10(6):891‐899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Aguirre‐Ghiso JA, Estrada Y, Liu D, Ossowski L. ERK(MAPK) activity as a determinant of tumor growth and dormancy; regulation by p38(SAPK). Cancer Res. 2003;63(7):1684‐1695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ranganathan AC, Zhang L, Adam AP, Aguirre‐Ghiso JA. Functional coupling of p38‐induced up‐regulation of BiP and activation of RNA‐dependent protein kinase‐like endoplasmic reticulum kinase to drug resistance of dormant carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1702‐1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Esposito A, Ferraresi A, Salwa A, Vidoni C, Dhanasekaran DN, Isidoro C. Resveratrol contrasts IL‐6 pro‐growth effects and promotes autophagy‐mediated cancer cell dormancy in 3D ovarian cancer: role of miR‐1305 and of its target ARH‐I. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(9):2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Han B, Chen Y, Song C, et al. Autophagy modulates the stability of Wee1 and cell cycle G2/M transition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2023;677:63‐69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Zhou J, Jiang YY, Chen H, Wu YC, Zhang L. Tanshinone I attenuates the malignant biological properties of ovarian cancer by inducing apoptosis and autophagy via the inactivation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Cell Prolif. 2020;53(2):e12739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 111. Liu JZ, Hu YL, Feng Y, et al. BDH2 triggers ROS‐induced cell death and autophagy by promoting Nrf2 ubiquitination in gastric cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Lu Z, Luo RZ, Lu Y, et al. The tumor suppressor gene ARHI regulates autophagy and tumor dormancy in human ovarian cancer cells. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(12):3917‐3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Tian X, He Y, Qi L, et al. Autophagy inhibition contributes to apoptosis of PLK4 downregulation‐induced dormant cells in colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19(9):2817‐2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Vera‐Ramirez L, Hunter KW. Tumor cell dormancy as an adaptive cell stress response mechanism. F1000Res. 2017;6:2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Liu Z, Liu G, Ha DP, Wang J, Xiong M, Lee AS. ER chaperone GRP78/BiP translocates to the nucleus under stress and acts as a transcriptional regulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2023;120(31):e2303448120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Wang Z, Tan C, Duan C, et al. FUT2‐dependent fucosylation of HYOU1 protects intestinal stem cells against inflammatory injury by regulating unfolded protein response. Redox Biol. 2023;60:102618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. You K, Wang L, Chou CH, et al. QRICH1 dictates the outcome of ER stress through transcriptional control of proteostasis. Science. 2021. l371(6524):eabb6896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Cho J, Min HY, Lee HJ, et al. RGS2‐mediated translational control mediates cancer cell dormancy and tumor relapse. J Clin Invest. 2023;133(10):e171901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Liu Y, Lv J, Liang X, et al. Fibrin stiffness mediates dormancy of tumor‐repopulating cells via a Cdc42‐driven Tet2 epigenetic program. Cancer Res. 2018;78(14):3926‐3937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Ruppender N, Larson S, Lakely B, et al. Cellular adhesion promotes prostate cancer cells escape from dormancy. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Lopez‐Sanchez LM, Jimenez C, Valverde A, et al. CoCl2, a mimic of hypoxia, induces formation of polyploid giant cells with stem characteristics in colon cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Zhao S, Xing S, Wang L, et al. IL‐1beta is involved in docetaxel chemoresistance by regulating the formation of polyploid giant cancer cells in non‐small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):12763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Zheng M, Chen L, Fu J, et al. Cdc42 regulates the expression of cytoskeleton and microtubule network proteins to promote invasion and metastasis of progeny cells derived from CoCl(2)‐induced polyploid giant cancer cells. J Cancer. 2023;14(10):1920‐1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Zhang K, Yang X, Zheng M, Ning Y, Zhang S. Acetylated‐PPARgamma expression is regulated by different P53 genotypes associated with the adipogenic differentiation of polyploid giant cancer cells with daughter cells. Cancer Biol Med. 2023;20(1):56‐76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Zhou X, Zhou M, Zheng M, et al. Polyploid giant cancer cells and cancer progression. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:1017588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Liu K, Zheng M, Zhao Q, et al. Different p53 genotypes regulating different phosphorylation sites and subcellular location of CDC25C associated with the formation of polyploid giant cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Alhaddad L, Chuprov‐Netochin R, Pustovalova M, Osipov AN, Leonov S. Polyploid/multinucleated giant and slow‐cycling cancer cell enrichment in response to x‐ray irradiation of human glioblastoma multiforme cells differing in radioresistance and TP53/PTEN status. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(2):1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Miller I, Min M, Yang C, et al. Ki67 is a graded rather than a binary marker of proliferation versus quiescence. Cell Rep. 2018;24(5):1105‐1112. e1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Davis JE, Jr. , Kirk J, Ji Y, Tang DG. Tumor dormancy and slow‐cycling cancer cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1164:199‐206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. DeLuca VJ, Saleh T. Insights into the role of senescence in tumor dormancy: mechanisms and applications. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023;42(1):19‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Akkoc Y, Peker N, Akcay A, Gozuacik D. Autophagy and cancer dormancy. Front Oncol. 2021;11:627023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Clezardin P, Coleman R, Puppo M, et al. Bone metastasis: mechanisms, therapies, and biomarkers. Physiol Rev. 2021;101(3):797‐855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Endo H, Inoue M. Dormancy in cancer. Cancer Sci. 2019;110(2):474‐480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Xuan B, Ghosh D, Cheney EM, Clifton EM, Dawson MR. Dysregulation in actin cytoskeletal organization drives increased stiffness and migratory persistence in polyploidal giant cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]