Summary

Persistent Inflammation, Immunosuppression, and Catabolism Syndrome (PICS) is a clinical endotype of chronic critical illness. PICS consists of a self-perpetuating cycle of ongoing organ dysfunction, inflammation, and catabolism resulting in sarcopenia, immunosuppression leading to recurrent infections, metabolic derangements, and changes in bone marrow function. There is heterogeneity regarding the definition of PICS. Currently, there are no licensed treatments specifically for PICS. However, findings can be extrapolated from studies in other conditions with similar features to repurpose drugs, and in animal models. Drugs that can restore immune homeostasis by stimulating lymphocyte production could have potential efficacy. Another treatment could be modifying myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) activation after day 14 when they are immunosuppressive. Drugs such as interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 receptor antagonists might reduce persistent inflammation, although they need to be given at specific time points to avoid adverse effects. Antioxidants could treat the oxidative stress caused by mitochondrial dysfunction in PICS. Possible anti-catabolic agents include testosterone, oxandrolone, IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor-1), bortezomib, and MURF1 (muscle RING-finger protein-1) inhibitors. Nutritional support strategies that could slow PICS progression include ketogenic feeding and probiotics. The field would benefit from a consensus definition of PICS using biologically based cut-off values. Future research should focus on expanding knowledge on underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of PICS to identify and validate other potential endotypes of chronic critical illness and subsequent treatable traits. There is unlikely to be a universal treatment for PICS, and a multimodal, timely, and personalised therapeutic strategy will be needed to improve outcomes for this growing cohort of patients.

Keywords: chronic critical illness; critical care; PICS; post-intensive care syndrome; persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome

Editor's key points.

-

•

Post-intensive care syndrome, chronic critical illness, persistent critical illness, and persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome (PICS) are syndromes with overlapping features that require more precise definitions for diagnosis and study.

-

•

PICS is likely an endotype of chronic critical illness, and other endotypes likely exist.

-

•

Future collaborative research work is needed to elucidate the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of PICS, identify other potential endotypes, and enable mechanism-based therapies.

-

•

Potential treatments modalities include immunotherapy, anti-inflammatory and anti-catabolic approaches, and nutritional support for this growing cohort of former ICU patients.

After acute critical illness, possible outcomes include early death, rapid recovery, or failure to recover normal physiological function with development of chronic symptoms.1 Advances in intensive care have resulted in a growing cohort of patients in the latter two groups. Various terms have been proposed to classify patients surviving an acute critical illness but suffering from prolonged ICU stays and chronic symptoms on discharge. These terms include post-intensive care syndrome, chronic critical illness (CCI), persistent critical illness (PerCI), and persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome (PICS). There are many overlapping features between these syndromes, and the same patient can fit the diagnostic criteria for more than one of these. However, each classification has its own particular focus.

Post-intensive care syndrome

Post-intensive care syndrome occurs when patients have new or worsening impairments in at least one of three domains, following and persisting after an ICU admission. These domains include physical function (e.g. neuromuscular or pulmonary disease), cognitive function (e.g. memory, attention, or executive function), and mental health (e.g. depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder).2 There are both subjective and objective instruments used to measure these impairments, although there is no widely accepted consensus on which specific instruments to use and at what point to assess patients after discharge.3, 4, 5 Impairments in these domains affect social aspects, such as employment, and health-related quality of life.6 Approximately 50% of acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors do not return to work within 1 yr after discharge.7 The term post-intensive care syndrome applies to family members and the survivors themselves.8 Thus, post-intensive care syndrome gives a patient-focused approach in its definition, and this can be useful for ICU service evaluations and quality improvement initiatives. The broad nature of its definition underlies the heterogeneity in symptoms reported by this patient cohort. A limitation of the definition is that it does not provide mechanistic insights that could aid treatment development.

Chronic critical illness

Chronic critical illness (CCI) was first described almost 40 yr ago.9 However, there remains a lack of consensus on its exact definition.10, 11, 12 Girard and Raffin9 originally described CCI as the need for constant support and homeostatic correction with intensive therapy as a result of persistent organ dysfunction. In 2005, CCI was clinically described in patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation for at least 6 h a day for more than 21 days or requiring tracheostomy placement during their ICU stay.13 CCI was later described when patients with limited physiological reserves, owing to frailty and chronic comorbidities, have an acute critical illness that results in a chronic syndrome of prolonged mechanical ventilation with additional features. These include neuromuscular weakness, neuroendocrine changes, immunosuppression, brain dysfunction, and skin breakdown.14 Tracheostomy placement after at least 10 days of mechanical ventilation could mark the onset of CCI as this indicates a time when the patient is not expected to either imminently die or be weaned successfully.14

The Research Triangle Institute (RTI) defined CCI as an ICU length of stay (LOS) of at least 8 days with one of the following eligible clinical conditions: prolonged mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, multiple organ failure, sepsis, and other severe infections or severe wounds.15 However, this definition was not designed for clinical purposes but to assist policy makers in standardising prospective payments for potential long-term acute care hospitalisation.10,16 More recently, CCI has been defined as an ICU LOS of at least 14 days with evidence of persistent organ dysfunction, measured using components of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (i.e. cardiovascular SOFA ≥1, or score in any other organ system ≥2).17

Overall, CCI as a concept focuses on differentiating between what counts as ‘acute’ vs ‘chronic’, and how ongoing critical illness should be defined, usually by prolonged mechanical ventilation or persistent organ dysfunction. The timeframes to define ‘chronic’ seem to range from 7, 10, 14, or 21 days. Although these are based on expert opinion, they are arbitrary.18,19

Persistent critical illness

Persistent critical illness (PerCI) occurs when a cascade of new critical illnesses is more likely to contribute to continued ICU stay and potential mortality than the admitting diagnosis.20 This cascade could be repeated new insults from failure of homeostatic recovery, an aggregation of random, unfortunate events, or suboptimal management and iatrogenic causes.18 PerCI is a syndrome in its own respect and should be distinguished from conditions that have a long intrinsic recovery time, such as Guillain–Barré syndrome. Similarly, patients with PerCI should be distinguished from those with a poor baseline physiology that is insufficient to support function despite the new acute illness, and whose ICU course is attributed to their admitting diagnosis and advanced underlying disease.10 Instead, PerCI is an indolent form of critical illness originating prior to ICU admission, and resulting from a complex interplay between pre-admission morbidity, complications, ongoing disease, and the pathological effects of prolonged illness.21 At a population level, a transition point for PerCI occurs in the second week of an ICU stay around day 10.22 At this point, admission characteristics, such as diagnosis and severity of illness, are no better at discriminating hospital mortality than simple patient characteristics and comorbidities.18 This ‘loss of discrimination’ is because of cascading critical illnesses which become the primary determinants of long-term mortality, above that of the initial diagnosis.18 Overall, PerCI is an epidemiologically focussed definition for a subset of long-stay ICU patients, focussing on a time point at which new critical illnesses account for their prolonged admission rather than their initial diagnosis. It is debateable whether there are clinically meaningful differences between CCI and PerCI, or whether introducing these new terms is worsening the ‘Pinocchio effect’. The Pinocchio effect describes the situation where syndromes are treated as real diseases and population heterogeneity is transformed into syndrome homogeneity. This comes with an unrealistic expectation that specific treatments given to these nonspecific syndromes can be successful.23

Persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome

Persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome (PICS) has been introduced as a clinical endotype of the CCI phenotype.24 PICS should be distinguished from post-intensive care syndrome, which can confusingly be referred to with the same acronym. Although the patient cohorts overlap between PICS and post-intensive care syndrome, PICS is a model for the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying CCI. This consists of a self-perpetuating cycle of ongoing organ dysfunction, inflammation, catabolism resulting in sarcopenia, immunosuppression leading to recurrent infections, metabolic derangements, and changes in bone marrow function.25

Each of the terms within PICS has suggested surrogates. In the original description by Gentile and colleagues24: (a) persistent was defined as an ICU stay ≥10 days or prolonged hospitalisation >14 days; (b) inflammation as C-reactive protein (CRP) >1.5 mg L−1; (c) immunosuppression as a total lymphocyte count <0.80 × 109 L−1; and (d) catabolism as serum albumin <3.0 g dl−1, creatinine height index <80%, weight loss >10%, BMI <18 during hospital admission, or retinol-binding protein <10 μg dl−1. There is heterogeneity regarding the definition of PICS. Mira and colleagues26 gave similar cut-off values but suggested a lower CRP threshold of >0.5 mg L−1 as a marker of inflammation and a longer ICU stay of >14 days. With both definitions, it is unclear at what point these blood results need to be recorded. The basis for these cut-off values has not been fully established, contributing to the heterogeneity in definition.27 Using machine learning models, one study showed optimal cut-off values to define PICS as CRP >20 mg L−1, albumin <3.0 g dl−1, and a lymphocyte count <800 μl−1 on day 14.27 Notably, this CRP cut-off value is 40-fold greater than that proposed by Mira and colleagues.26

Other alterations from the original PICS definition include adding a prealbumin level of <10 mg dl−1 as a catabolism marker,28 clarifying that the blood results should be from the same day,28 and a different CRP cut-off as >30 mg L−1.29 One study proposed that PICS could be inferred if one or more of the surrogates for the three components (inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism) were positive.29 Another study gave both a clinical PICS and a PICS marker-positive definition. Clinical PICS was described as an ICU stay ≥14 days, three or more infectious complications, and evidence of catabolism, either by weight loss of >10%, BMI <18, or albumin <30 g L−1 during hospitalisation. The PICS marker-positive definition was determined if, during the first 30 days of hospital admission, patients have ≥2 days of immunosuppression (total lymphocyte count <0.8 × 109 L−1), ≥2 days of inflammation (CRP >50 mg L−1), and a catabolic state as described above in their clinical PICS definition.30 The different definitions for PICS are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the diagnostic criteria for persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome (PICS).

| Gentile and colleagues24 | Mira and colleagues26 | Hu and colleagues28 | Nakamura and colleagues29 | Hesselink and colleagues30 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU length of stay (days) | ≥10 | >14 | >10 | ≥14 | |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | >14 | >14 | |||

| C-reactive protein (mg L−1) | >1.5 | >0.5 | >1.5 | >30 | >50 |

| Total lymphocyte count (×109 L−1) | <0.8 | <0.8 | <0.8 | <0.8 | <0.8 |

| Albumin (g dl−1) | <3.0 | <3.0 | <3.0 | <3.0 | <3.0 |

| Pre-albumin (mg dl−1) | <10 | <10 | |||

| Creatinine height index (%) | <80 | <80 | <80 | ||

| Retinol-binding protein (mg dl−1) | <0.01 | <1 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| Weight loss (%) | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| BMI during hospitalisation | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 |

| Number of infectious complications | ≥3 |

These currently used diagnostic biomarkers are unlikely to be sensitive or specific enough to allow early identification of patients with PICS and individualised, targeted treatment.30 The variety of genetic and molecular changes associated with PICS means there are likely many other biomarkers of inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism that could have a higher sensitivity or specificity, but currently limited validation studies of such biomarkers have been completed.

Post-intensive care syndrome is a broad umbrella term for patients with persisting symptoms, be they physical, mental, or cognitive, after an acute critical illness. CCI is a subgroup within this cohort, predominately focused on physical symptoms with an emphasis on prolonged mechanical ventilation and multi-organ dysfunction. PerCI gives an epidemiological transition point for a subgroup of long-stay ICU patients where new cascading critical illnesses become the primary determinant of morbidity and mortality over the admitting diagnosis. Finally, PICS offers a definition with potential mechanistic insight. It is also the classification system that might be most amenable to intervention and prevention, as each of its components of inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism should be, in theory, reversible; hence, PICS is the focus of this review.

Epidemiology

The varying classifications for long-stay ICU patients and heterogeneous definitions pose a challenge for epidemiological research. For post-intensive care syndrome, broad incidence estimates have been shown for each of its components. Thus, psychiatric illnesses occur in 8–57% of ICU survivors, cognitive impairment in 30–80%, and new physical impairment in 25–80%.31, 32, 33, 34 Furthermore, systematic reviews have shown that at 1-yr follow-up, about one-third of critical care survivors experience anxiety35 and depressive symptoms,36 and one-fifth experience post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms.37 For CCI, a large study on 3 235 741 ICU admissions demonstrated that 7.6% met the RTI definition.16 Other studies have shown larger incidence estimates for CCI between 33% and 40%.11,38, 39, 40 A retrospective, observational study showed that cases of PerCI accounted for 5% of admissions but for 32.8% of ICU bed-days.22 There is limited epidemiological data available on the incidence of PICS because of the different definitions and substantial overlap with CCI.

Consequences

Patients with post-intensive care syndrome, CCI, PerCI, or PICS suffer from significant morbidity and mortality, with limited effective treatments.2,22,25 Patients with CCI commonly suffer from accelerated ageing and increased frailty, recurrent infections, muscle wasting and decline in physical function, hospital readmissions, and cognitive impairment.41,42 Furthermore, patients with CCI had a significantly higher 6-month mortality than those who experienced rapid recovery (37% vs 2%, respectively, P<0.01).43 Only around one-fifth of patients with CCI are discharged home, with the majority remaining in skilled nursing facilities or long-term acute care hospitals.16 CCI causes significant burdens on patients and their families, and the economy, with an estimated cost in the USA of $26 billion for 2009.16

Potential therapeutic avenues

Overall, there is a lack of understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying PICS. When considering our ageing population and reduced ICU mortality rates, the burden of PICS for patients, families, healthcare staff, and policymakers will continue to increase. We therefore need to prioritise research in this area to develop new treatments for PICS. The remainder of this review will summarise potential therapeutic avenues and areas of future research priority.

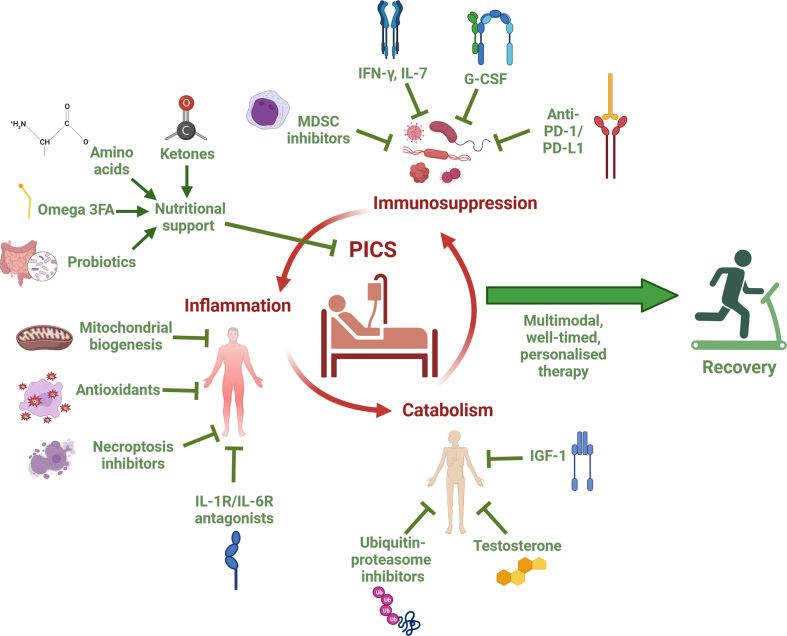

The three components of PICS—inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism—have reciprocal causation and form a self-perpetuating cycle, which likely requires multimodal approaches to prevent progression.25 PICS shares common features with other disorders, such as cancer, chronic renal disease, and cardiac cachexia.44 Although there is limited direct clinical evidence on specific treatments to improve long-term outcomes for patients with PICS, data can be extrapolated from other conditions to repurpose drugs, and from studies using animal models. However, as critical illness has systemic effects that impact drug absorption, distribution, and metabolism, and a multifactorial aetiologies, there are added complexities to repurposing treatments from other conditions.45 The range of possible treatments for PICS covers the immune system, inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways, muscle wasting, and nutritional support (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Summary diagram of potential treatments for Persistent Inflammation, Immunosuppression, and Catabolism Syndrome (PICS). This illustration highlights a range of potential treatments, organised by the specific component of PICS. It suggests that a multimodal, well-timed, personalised treatment strategy may be sufficient to break the self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism that underlies PICS and promote recovery. G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IL-1R, interleukin-1 receptor; IL-6R, interleukin-6 receptor; IL-7, interleukin-7; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; omega-3FA, omega-3 fatty acids; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; PD-1, programmed death protein 1 (Created with BioRender.com).

Immunotherapy

Although there are no currently licensed treatments specifically for PICS, there is ongoing research in multiple conditions on drugs that can restore immune homeostasis which could have potential efficacy in PICS. One method involves restoring normal lymphocyte numbers through granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF). A clinical trial on septic immunosuppressed paediatric patients showed that GM-CSF restored TNF production in lymphocytes and decreased nosocomial infection, time on mechanical ventilation, and hospital LOS.46 However, a meta-analysis of 12 RCTs showed that although G-CSF and GM-CSF improved infection clearance, there was no significant difference in 28-day mortality compared with placebo.47 As the studies did not include outcomes after 28 days, it is unclear whether there would have been significant improvements in outcomes relevant for patients with PICS.

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) is a key cytokine for activation of monocytes and macrophages, and both animal and human studies have shown that IFN-γ production is reduced during sepsis.48, 49, 50 Treatment for septic patients with recombinant IFN-γ increased monocyte mHLA-DR expression and function.51,52 In an RCT on severe trauma patients, IFN-γ treatment decreased the number of infection-related deaths.53 The immunomodulatory benefits of IFN-γ might be restricted to patients with downregulated mHLA-DR expression.54 IL-7 is an antiapoptotic cytokine that stimulates immune effector cell function that increases CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell numbers in murine models of sepsis, and was associated with increased survival.48,55 In human studies, IL-7 increases T-cell receptor diversity which is decreased with sepsis.56, 57, 58 During sepsis, Programmed Death-1 (PD-1) is upregulated on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to prevent excessive T-cell activation, and high levels are associated with increased secondary infection and mortality in critical illness.58, 59, 60 Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy has had some success in cancer treatment.61 PD-1/PD-L1 blockade can increase cytokine release and reduce viral loads in mice for weeks after treatment.62 Furthermore, blockade of this pathway reduces lymphocyte depletion and improves survival in murine models of sepsis.63,64

Although the pathophysiology of PICS remains to be fully elucidated, persistent expansion of MDSCs is thought to play a key role.65,66 In response to a severe insult, such as sepsis or trauma, emergency myelopoiesis occurs whereby granulocytes migrate from the bone marrow to the injured or infected site, allowing for the expansion of myeloid cells, including MDSCs.67, 68, 69, 70 MDSCs have an essential role in innate immunity and producing inflammatory mediators.66,71 Although MDSCs initially aid bacterial clearance and protect the host from early excessive inflammation or secondary infections, prolonged activation leads to immunosuppression and persistent inflammation.58,66 Modifying MDSC activation and expansion at a particular time point, such as after day 14 of sepsis when they are immunosuppressive,72 could be a potential therapeutic approach for PICS. In mice with burn injuries, gemcitabine, a ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor, given on day 6 resulted in a reduction in MDSCs and mortality after a lethal dose of lipopolysaccharide. However, the mice showed an increase in mortality to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection.73 Deficiency in MDSC signalling pathways can lead to an increase in inflammatory cytokines and a higher mortality.74 Other strategies of modulating MDSCs could involve epigenetic approaches44 or inhibiting MDSC by-products, such as arginase 1, nitric oxide (NO), or inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS).72 For example, in murine models of cancer, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil and tadalafil, inhibit iNOS, arginase 1, and MDSC function, which decreased mortality.75, 76, 77

Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant therapies

Many anti-inflammatory agents have been investigated for acute critical illness, but, similar to immunomodulatory therapies, there is limited data available on long-term outcomes. In a phase III clinical trial on septic patients with features of macrophage activation syndrome, IL-1 receptor blockade with anakinra was associated with reduced mortality.78 Blockade of IL-6-mediated pathways can reduce inflammatory responses and IL-6 receptor antagonists, tocilizumab and sarilumab, improve outcomes including survival in critically ill patients with COVID-19 infection.79 Anti-inflammatory agents in PICS require further investigation as inappropriate use could have adverse effects from stimulation or inhibition of other pertinent signalling pathways, especially if the timing of intervention is unsuitable.

Muscle biopsies in critically unwell patients have shown neutrophil and macrophage infiltration and muscle necrosis, which could be the persistent inflammation source in PICS.80 Targeting this necroptosis could be an alternative anti-inflammatory treatment strategy for PICS. Key components of necroptosis signalling include receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), RIPK3, and the mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) pseudokinase; there are potential small-molecule inhibitors of these targets, reviewed fully elsewhere.81

Another possible pathophysiological mechanism for PICS and its associated muscle wasting is mitochondrial dysfunction and a resultant bioenergetic crisis.82 Critically ill patients have mitochondrial swelling, and reduced mitochondrial numbers and density, which can take 6 months to recover after ICU discharge.83 Antioxidants have the potential to treat the oxidative stress caused by mitochondrial dysfunction.84 In a rat model of acute sepsis, mitochondria-targeted ubiquinone (Mit Q) decreased mitochondrial damage, IL-6 levels, and organ dysfunction.85 In other septic animal models, Mit Q reduced renal and liver injury86 and cardiac mitochondrial and contractile dysfunction.87 Melatonin has anti-inflammatory properties by acting as a scavenger for oxygen- and nitrogen-derived reactive species, and in animal models of sepsis melatonin inhibited mitochondrial damage and stimulated ATP generation.88, 89, 90 Caesium nanoparticles given i.v. to septic rats reduced reactive oxygen species production and mortality.91 An alternative therapeutic strategy could be to increase mitochondrial biogenesis, through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists, such as pioglitazone and rosiglitazone, or sirtuin activators, such as resveratrol.88 A systematic review showed that pioglitazone administration reduces intramuscular inflammation and increases intramuscular markers of ATP biosynthesis.92

Anabolic and anti-catabolic therapies

In critical illness, 3–5% of skeletal muscle is lost per day and this catabolism can continue for up to 30 days.80,82,93 Early mobilisation causes muscle fibre contraction that stimulates the mTOR signalling pathway and muscle hypertrophy.84,94 An RCT on 21 patients with septic shock showed that early physical therapy within the first week preserved muscle fibre cross-sectional area.95 In another RCT of 104 patients, daily interruption of sedation combined with early physical and occupational therapy was well tolerated, improved functional outcomes at discharge, and gave more ventilator-free days compared with standard care.96 Another RCT on 200 patients showed that early, goal-directed mobilisation improved functional mobility at discharge and decreased LOS.97 However, a larger more recent RCT on 750 patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation showed that early active mobilisation was associated with increased adverse events and did not result in more days that patients were alive and out of hospital.98 Other strategies involve the use of pharmacological agents. Through androgen signalling pathways, testosterone reduces muscle breakdown and autophagy, as demonstrated in patients with severe burns. Oxandrolone, a testosterone analogue, and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) reduce muscle breakdown in patients with burns.99, 100, 101 It is likely that the ubiquitin–proteasome system is involved in the catabolism of PICS, and ubiquitin–proteasome system inhibitors, bortezomib and MURF1 inhibitors, can prevent muscle breakdown.84,102

Nutritional support

Guidelines suggest that early enteral nutrition within 48 h of ICU admission could be effective in improving nutritional status and reducing inflammation.103 Guidelines also suggest that higher protein supplementation could improve outcomes by preserving muscle mass and reducing mortality.45,104, 105, 106 However, given the anabolic resistance that occurs in critical illness which can reduce up to 60% of the synthetic response, higher protein supplementation alone is unlikely to be effective in preventing catabolism in PICS.45,107,108 The recent EFFORT Protein trial demonstrated that higher protein doses did not improve the time-to-discharge-alive from hospital but had a signal for harm in patients with acute kidney injury and higher organ failure scores, effectively terminating this line of enquiry.109 Compared with patients with rapid recovery, patients with CCI failed to become anabolic despite getting sufficient macronutrients early after ICU admission, implying that other nutritional strategies are required for CCI/PICS.110 An immune-enhancing diet consisting of arginine, glutamine, nucleotides, omega-3 fatty acids, fish oil, selenium, vitamin C, and vitamin E has been hypothesised to reduce infections, promote recovery, and decrease ICU LOS.111

Arginine is an amino acid with a wide range of functions, including being a substrate for NO synthase, promoting vasodilation that enhances oxygen and nutrient delivery to tissues. Intracellularly, it can improve bactericidal activity of macrophages and T-cell proliferation and maturation.112, 113, 114, 115 In PICS, upregulation of arginase-1 by MDSCs leads to arginine deficiency, which could contribute to immunosuppression by causing failure of lymphocyte proliferation.84,116 Arginine supplementation in PICS might therefore promote recovery and partly reverse immunosuppression. A concern that arginine-induced vasodilation could alter haemodynamics and adversely affect septic patients is unlikely to be of significance if arginine is given outside of the acute window.112 Branched chain amino acids, including leucine, valine, and isoleucine, have a potential therapeutic benefit in PICS through anti-catabolic effects and increasing protein synthesis.117 A metabolite of leucine, beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate (HMB), can attenuate sarcopenia in older patients and might also have therapeutic potential in other muscle wasting conditions.118 Together, arginine and leucine synergistically activate the Akt-mTOR pathway that enhances protein synthesis and inhibits protein breakdown.119,120

Another amino acid, glutamine, could be of benefit in PICS through its pluripotent actions of enhancing gluconeogenesis and immune function, and acting as an antioxidant.112 However, early administration of glutamine to critically ill patients with multiorgan failure was associated with an increase in mortality.121 A mediation analysis of this trial showed that the urea-to-creatinine ratio was sensitive to glutamine administration and accounted for the higher risk of death with glutamine, suggesting a causal link between iatrogenic uraemia and mortality in PICS.122

Omega-3 fatty acids have anti-inflammatory effects in a wide range of conditions, including but not limited to, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and multiple sclerosis.112 In critical illness, a meta-analysis showed that omega-3 fatty acid-containing parenteral nutrition compared with standard parenteral nutrition is associated with reduced rates of infection and ICU LOS.123 Furthermore, a study on healthy volunteers showed that fish oil infusions can blunt the inflammatory response to endotoxin exposure.124 Specialised pro-resolving mediators are derivatives of omega-3 fatty acids that can reduce inflammation and promote tissue and organ recovery, which could attenuate the development of PICS.125, 126, 127, 128

Intermittent fasting could be beneficial in preventing or managing PICS through fasting-induced autophagy to clear macromolecular damage, enhancing ketogenesis which could stimulate muscle regeneration and reduce inflammation, and stimulating various signalling pathways that modulate mitochondrial biogenesis and the unfolded protein response.129, 130, 131, 132, 133 This is supported by many preclinical and observational studies.129 However, there are limited RCTs on intermittent fasting in critically ill patients looking at long-term outcomes and the development of PICS. RCTs comparing continuous feeding with intermittent feeding/fasting regimens in acute critical illness have yielded conflicting results, although the studies have been heterogeneous with small sample sizes.129 One study showed that intermittent feeding (six 4-hourly feeds in 24 h) on patients at risk for PerCI increased nutritional target requirements and was tolerated by patients but did not reduce muscle wasting.134 The short fasting intervals of 4–6 h used in such trials might be insufficient to activate the relevant cell-protective pathways.135,136 However, longer fasting periods could lead to feed intolerance.

An alternative strategy to activate similar pathways could be ketogenic feeding. Critical illness can prevent the efficient metabolism of the usual substrates, leading to metabolic dysfunction, but ketone bodies could provide an alternative substrate.137,138 Ketogenic feeding can promote immunomodulatory, regenerative, and anabolic pathways, and regulate autophagy.129,139,140 In a mouse model of sepsis-induced critical illness, treatment with the ketone ester 3HHB (3-hydroxybutyl-3-hydroxybutanoate) attenuated muscle weakness.141 Furthermore, in a murine model of autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a fasting mimicking diet reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and promoted cell regeneration.142 The Alternative Substrates in the Critically Ill Subject trial (ASICS, NCT04101071) is currently exploring the feasibility of giving a ketone-inducing feeding regime to critically ill patients.

Finally, the stress of critical illness and PICS can negatively affect the gut microbiome, and there has been growing interest in microbiota modulation with prebiotics and probiotics in many conditions.84 These can modulate the microbiome by increasing beneficial bacteria and reducing disease-causing bacteria, thereby reducing inflammation, enhancing the immune function of the gut, and restoring normal gut function.143,144 A meta-analysis on potential nutritional and pharmacological interventions against chronic low-grade inflammation with ageing showed that probiotics had the largest effect on reducing inflammatory markers (CRP and IL-6).145 However, administration of prebiotics and probiotics on ICU is not currently a standard of care, in part owing to the limited available evidence in this population and the risk of side-effects. There is also limited evidence on the specific species or regimens that should be used.

Future research priorities

There are several priorities for future research in this area to achieve better long-term outcomes for patients with PICS. Firstly, as outlined above, the field would certainly benefit from a consensus definition of PICS for epidemiological and clinical trials. Ideally, these definitions would use data- and biology-based cut-off values rather than arbitrary values. Establishing consensus definitions would allow for more accurate estimates for the incidence of PICS, and these data could drive appropriate funding and resource allocation. Furthermore, it would allow for comparison and meta-analyses between clinical trials to be conducted.

Secondly, as with many ICU conditions, specific treatments should be targeted to subgroups of patients who have shared underlying pathophysiological mechanisms that make them more amenable and hence more likely to benefit from the treatment. Therefore, future research should focus on expanding our knowledge on these underlying pathophysiological mechanisms and identify and validate other potential endotypes of CCI and subsequent treatable traits.146 This will likely require a variety of approaches including basic science and creating suitable animal models, multi-omic approaches, using genomic, epigenetic, and proteomic analyses, and big data and machine learning tools using both biological and clinical variables. Use of murine models of PICS has been established; these commonly involve a semi-lethal caecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model.147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153 However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of these models, such as differences in human and murine responses to sepsis, and that murine CLP survivors have a necrotic caecum and indeterminate nidus of infection.25 Many of these studies use young adult mice which do not clearly represent the aged population with comorbidities who are more likely to become septic.154

Thirdly, the improved understanding we obtain from laboratory studies should be directly translated into clinical trials and the development of therapeutic interventions for treatable traits in a bidirectional bedside-to-bench-to-bedside manner. Using platform trial designs could allow several interventions to be tested simultaneously and enhance the efficiency of studies. Furthermore, use of adaptive trial designs can overcome the long interval between intervention and outcome assessment in PICS trials by allowing treatments showing futility to be abandoned early and novel treatments to be added in, as we learn from the data as the trial progresses. There is unlikely to be a single ‘silver bullet’ treatment for PICS and therefore adaptive platform trials might be best suited to test multimodal approaches.

Fourthly, alongside new therapeutics, the epidemiological and basic science research should help us identify risk factors and biomarkers of PICS, and this will in turn allow for early diagnosis, or ideally a focus on prevention, to occur. Fifthly, all of this will require multicentre collaboration and data sharing, and involving expertise from a multidisciplinary team and other clinical specialties, such as geriatrics and oncology, where patients experience similar issues of immunosuppression, inflammation, and catabolism. Finally, it is important to remember that patient/public involvement will be crucial as research should focus on patient-reported outcomes.

A previous scoping review of 425 publications on ICU survivors showed that 250 different outcome measurement tools were used.155 This heterogeneity limits comparison and synthesis of studies and it is crucial for future trials to focus on patient-reported outcomes to assess the impact of potential treatments in a meaningful and holistic manner. When excluding mortality, only 5% of ICU RCTs used patient-important outcomes as the primary outcome measure.156 Given the poor health-related quality of life of patients with PICS and their multiple functional impairments, a drive to include patient-reported outcomes is even more important in this cohort.

Conclusions

A consensus definition of PICS is needed for consistency in future research. Regardless of the definition, PICS is likely an endotype of CCI, implying that other endotypes exist. Future collaborative research work is needed to expand our knowledge of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of PICS and identify other potential endotypes. This will identify treatable features that will drive multimodal, personalised treatments, likely including immunotherapy, anti-inflammatory and anti-catabolic therapies, and nutritional support, to improve outcomes for this growing cohort of patients.

Authors’ contributions

Conception: both authors

Interpretation of data: both authors

Drafting the original manuscript: KRC

Revising subsequent drafts: both authors

Approved the final version of the article to be published: both authors

Declarations of interest

ZP has received honoraria for consultancy from Nestlé, Nutricia, Faraday Pharmaceuticals, and Fresenius-Kabi and speaker fees from Baxter, Fresenius-Kabi, Nutricia, and Nestlé. KRC declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Handling Editor: Hugh C Hemmings Jr

References

- 1.Zhou Q., Qian H., Yang A., Lu J., Liu J. Clinical and prognostic features of chronic critical illness/persistent inflammation immunosuppression and catabolism patients: a prospective observational clinical study. Shock. 2023;59:5–11. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000002035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Needham D.M., Davidson J., Cohen H., et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders' conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mikkelsen M.E., Still M., Anderson B.J., et al. Society of Critical Care Medicine's International Consensus Conference on prediction and identification of long-term impairments after critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:1670–1679. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spies C.D., Krampe H., Paul N., et al. Instruments to measure outcomes of post-intensive care syndrome in outpatient care settings - results of an expert consensus and feasibility field test. J Intensive Care Soc. 2021;22:159–174. doi: 10.1177/1751143720923597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elliott D., Davidson J.E., Harvey M.A., et al. Exploring the scope of post-intensive care syndrome therapy and care: engagement of non-critical care providers and survivors in a second stakeholders meeting. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:2518–2526. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paul N., Cittadino J., Weiss B., Krampe H., Denke C., Spies C.D. Subjective ratings of mental and physical health correlate with EQ-5D-5L index values in survivors of critical illness: a construct validity study. Crit Care Med. 2023;51:365–375. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herridge M.S., Cheung A.M., Tansey C.M., et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosilek R.P., Schmidt K., Baumeister S.E., Gensichen J., Group S.S. Frequency and risk factors of post-intensive care syndrome components in a multicenter randomized controlled trial of German sepsis survivors. J Crit Care. 2021;65:268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2021.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girard K., Raffin T.A. The chronically critically ill: to save or let die? Respir Care. 1985;30:339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwashyna T.J., Hodgson C.L., Pilcher D., et al. Towards defining persistent critical illness and other varieties of chronic critical illness. Crit Care Resusc. 2015;17:215–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halacli B., Yildirim M., Kaya E.K., Ulusoydan E., Ersoy E.O., Topeli A. Chronic critical illness in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Chronic Illn. 2023 doi: 10.1177/17423953231161333. Advance Access published on March 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S., Wu X., Ren J. Diagnostic criteria for chronic critical illness should be standardized. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:e1060-e1. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacIntyre N.R., Epstein S.K., Carson S., et al. Management of patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: report of a NAMDRC consensus conference. Chest. 2005;128:3937–3954. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson J.E., Cox C.E., Hope A.A., Carson S.S. Chronic critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:446–454. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0210CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandilov A., Ingber M., Morley M., et al. RTI International; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2014. Chronically critically ill population payment recommendations. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahn J.M., Le T., Angus D.C., et al. The epidemiology of chronic critical illness in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:282–287. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loftus T.J., Mira J.C., Ozrazgat-Baslanti T., et al. Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center investigators: protocols and standard operating procedures for a prospective cohort study of sepsis in critically ill surgical patients. BMJ Open. 2017;7 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwashyna T.J., Viglianti E.M. Patient and population-level approaches to persistent critical illness and prolonged intensive care unit stays. Crit Care Clin. 2018;34:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carson S.S., Bach P.B. The epidemiology and costs of chronic critical illness. Crit Care Clin. 2002;18:461–476. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(02)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwashyna T.J., Hodgson C.L., Pilcher D., Bailey M., Bellomo R. Persistent critical illness characterised by Australian and New Zealand ICU clinicians. Crit Care Resusc. 2015;17:153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeffcote T., Foong M., Gold G., et al. Patient characteristics, ICU-specific supports, complications, and outcomes of persistent critical illness. J Crit Care. 2019;54:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwashyna T.J., Hodgson C.L., Pilcher D., et al. Timing of onset and burden of persistent critical illness in Australia and New Zealand: a retrospective, population-based, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:566–573. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soni N. ARDS, acronyms and the Pinocchio effect. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:976–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gentile L.F., Cuenca A.G., Efron P.A., et al. Persistent inflammation and immunosuppression: a common syndrome and new horizon for surgical intensive care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1491–1501. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318256e000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkins R.B., Raymond S.L., Stortz J.A., et al. Chronic critical illness and the persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1511. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mira J.C., Gentile L.F., Mathias B.J., et al. Sepsis pathophysiology, chronic critical illness, and persistent inflammation-immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:253–262. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura K., Ogura K., Ohbe H., Goto T. Clinical criteria for persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome: an exploratory analysis of optimal cut-off values for biomarkers. J Clin Med. 2022;11:5790. doi: 10.3390/jcm11195790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu D., Ren J., Wang G., et al. Persistent inflammation-immunosuppression catabolism syndrome, a common manifestation of patients with enterocutaneous fistula in intensive care unit. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:725–729. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182aafe6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamura K., Ogura K., Nakano H., et al. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy is associated with the outcome of persistent inflammation, immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2662. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hesselink L., Hoepelman R.J., Spijkerman R., et al. Persistent Inflammation, Immunosuppression and Catabolism Syndrome (PICS) after polytrauma: a rare syndrome with major consequences. J Clin Med. 2020;9:10. doi: 10.3390/jcm9010191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colbenson G.A., Johnson A., Wilson M.E. Post-intensive care syndrome: impact, prevention, and management. Breathe (Sheff) 2019;15:98–101. doi: 10.1183/20734735.0013-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvey M.A., Davidson J.E. Postintensive care syndrome: right care, right now...and later. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:381–385. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandharipande P.P., Girard T.D., Jackson J.C., et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffiths J., Hatch R.A., Bishop J., et al. An exploration of social and economic outcome and associated health-related quality of life after critical illness in general intensive care unit survivors: a 12-month follow-up study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R100. doi: 10.1186/cc12745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nikayin S., Rabiee A., Hashem M.D., et al. Anxiety symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;43:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabiee A., Nikayin S., Hashem M.D., et al. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1744–1753. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parker A.M., Sricharoenchai T., Raparla S., Schneck K.W., Bienvenu O.J., Needham D.M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1121–1129. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stortz J.A., Murphy T.J., Raymond S.L., et al. Evidence for persistent immune suppression in patients who develop chronic critical illness after sepsis. Shock. 2018;49:249–258. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brakenridge S.C., Efron P.A., Cox M.C., et al. Current epidemiology of surgical sepsis: discordance between inpatient mortality and 1-year outcomes. Ann Surg. 2019;270:502–510. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gardner A.K., Ghita G.L., Wang Z., et al. The development of chronic critical illness determines physical function, quality of life, and long-term survival among early survivors of sepsis in surgical ICUs. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:566–573. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenthal M.D., Kamel A.Y., Rosenthal C.M., Brakenridge S., Croft C.A., Moore F.A. Chronic critical illness: application of what we know. Nutr Clin Pract. 2018;33:39–45. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson J.E., Meier D.E., Litke A., Natale D.A., Siegel R.E., Morrison R.S. The symptom burden of chronic critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1527–1534. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000129485.08835.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stortz J.A., Mira J.C., Raymond S.L., et al. Benchmarking clinical outcomes and the immunocatabolic phenotype of chronic critical illness after sepsis in surgical intensive care unit patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84:342–349. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Efron P.A., Brakenridge S.C., Mohr A.M., et al. The persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome (PICS) ten years later. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;95:790–799. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000004087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McClelland T.J., Davies T., Puthucheary Z. Novel nutritional strategies to prevent muscle wasting. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2023;29:108–113. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000001020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meisel C., Schefold J.C., Pschowski R., et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to reverse sepsis-associated immunosuppression: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:640–648. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0363OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bo L., Wang F., Zhu J., Li J., Deng X. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) for sepsis: a meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2011;15:R58. doi: 10.1186/cc10031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Unsinger J., McGlynn M., Kasten K.R., et al. IL-7 promotes T cell viability, trafficking, and functionality and improves survival in sepsis. J Immunol. 2010;184:3768–3779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boomer J.S., Shuherk-Shaffer J., Hotchkiss R.S., Green J.M. A prospective analysis of lymphocyte phenotype and function over the course of acute sepsis. Crit Care. 2012;16:R112. doi: 10.1186/cc11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boomer J.S., To K., Chang K.C., et al. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA. 2011;306:2594–2605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Payen D., Faivre V., Miatello J., et al. Multicentric experience with interferon gamma therapy in sepsis induced immunosuppression. A case series. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:931. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4526-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Docke W.D., Randow F., Syrbe U., et al. Monocyte deactivation in septic patients: restoration by IFN-gamma treatment. Nat Med. 1997;3:678–681. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dries D.J., Jurkovich G.J., Maier R.V., et al. Effect of interferon gamma on infection-related death in patients with severe injuries. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Surg. 1994;129:1031–1041. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420340045008. discussion 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patil N.K., Bohannon J.K., Sherwood E.R. Immunotherapy: a promising approach to reverse sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Pharmacol Res. 2016;111:688–702. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Unsinger J., Burnham C.A., McDonough J., et al. Interleukin-7 ameliorates immune dysfunction and improves survival in a 2-hit model of fungal sepsis. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:606–616. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sportes C., Hakim F.T., Memon S.A., et al. Administration of rhIL-7 in humans increases in vivo TCR repertoire diversity by preferential expansion of naive T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1701–1714. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Venet F., Filipe-Santos O., Lepape A., et al. Decreased T-cell repertoire diversity in sepsis: a preliminary study. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:111–119. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182657948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Darden D.B., Kelly L.S., Fenner B.P., Moldawer L.L., Mohr A.M., Efron P.A. Dysregulated immunity and immunotherapy after sepsis. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1742. doi: 10.3390/jcm10081742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guignant C., Lepape A., Huang X., et al. Programmed death-1 levels correlate with increased mortality, nosocomial infection and immune dysfunctions in septic shock patients. Crit Care. 2011;15:R99. doi: 10.1186/cc10112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Day C.L., Kaufmann D.E., Kiepiela P., et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature. 2006;443:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature05115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen L., Han X. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy of human cancer: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3384–3391. doi: 10.1172/JCI80011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barber D.L., Wherry E.J., Masopust D., et al. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. 2006;439:682–687. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang Y., Zhou Y., Lou J., et al. PD-L1 blockade improves survival in experimental sepsis by inhibiting lymphocyte apoptosis and reversing monocyte dysfunction. Crit Care. 2010;14:R220. doi: 10.1186/cc9354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brahmamdam P., Inoue S., Unsinger J., Chang K.C., McDunn J.E., Hotchkiss R.S. Delayed administration of anti-PD-1 antibody reverses immune dysfunction and improves survival during sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:233–240. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0110037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mathias B., Delmas A.L., Ozrazgat-Baslanti T., et al. Human myeloid-derived suppressor cells are associated with chronic immune suppression after severe sepsis/septic shock. Ann Surg. 2017;265:827–834. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mira J.C., Brakenridge S.C., Moldawer L.L., Moore F.A. Persistent inflammation, immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33:245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Manz M.G., Boettcher S. Emergency granulopoiesis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:302–314. doi: 10.1038/nri3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Furze R.C., Rankin S.M. Neutrophil mobilization and clearance in the bone marrow. Immunology. 2008;125:281–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02950.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scumpia P.O., Kelly-Scumpia K.M., Delano M.J., et al. Cutting edge: bacterial infection induces hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell expansion in the absence of TLR signaling. J Immunol. 2010;184:2247–2251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ueda Y., Kondo M., Kelsoe G. Inflammation and the reciprocal production of granulocytes and lymphocytes in bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1771–1780. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Delano M.J., Scumpia P.O., Weinstein J.S., et al. MyD88-dependent expansion of an immature GR-1(+)CD11b(+) population induces T cell suppression and Th2 polarization in sepsis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1463–1474. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hollen M.K., Stortz J.A., Darden D., et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell function and epigenetic expression evolves over time after surgical sepsis. Crit Care. 2019;23:355. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2628-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Noel G., Wang Q., Osterburg A., et al. A ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor reverses burn-induced inflammatory defects. Shock. 2010;34:535–544. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181e14f78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sander L.E., Sackett S.D., Dierssen U., et al. Hepatic acute-phase proteins control innate immune responses during infection by promoting myeloid-derived suppressor cell function. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1453–1464. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Serafini P., Meckel K., Kelso M., et al. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition augments endogenous antitumor immunity by reducing myeloid-derived suppressor cell function. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2691–2702. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Meyer C., Sevko A., Ramacher M., et al. Chronic inflammation promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell activation blocking antitumor immunity in transgenic mouse melanoma model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17111–17116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108121108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lin S., Wang J., Wang L., et al. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition suppresses colonic inflammation-induced tumorigenesis via blocking the recruitment of MDSC. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7:41–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shakoory B., Carcillo J.A., Chatham W.W., et al. Interleukin-1 receptor blockade is associated with reduced mortality in sepsis patients with features of macrophage activation syndrome: reanalysis of a prior phase III trial. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:275–281. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Investigators R.-C., Gordon A.C., Mouncey P.R., et al. Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1491–1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Puthucheary Z.A., Rawal J., McPhail M., et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. JAMA. 2013;310:1591–1600. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gardner C.R., Davies K.A., Zhang Y., et al. From (tool)bench to bedside: the potential of necroptosis inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2023;66:2361–2385. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Flower L., Summers C., Puthucheary Z. In: Management of dysregulated immune response in the critically ill. Molnar Z., Ostermann M., Shankar-Hari M., editors. Springer Cham; Switzerland: 2023. Dysregulated immune response and organ dysfunction: the muscles; pp. 255–262. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schefold J.C., Wollersheim T., Grunow J.J., Luedi M.M., Z'Graggen W.J., Weber-Carstens S. Muscular weakness and muscle wasting in the critically ill. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020;11:1399–1412. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang J., Luo W., Miao C., Zhong J. Hypercatabolism and anti-catabolic therapies in the persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome. Front Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.941097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lowes D.A., Webster N.R., Murphy M.P., Galley H.F. Antioxidants that protect mitochondria reduce interleukin-6 and oxidative stress, improve mitochondrial function, and reduce biochemical markers of organ dysfunction in a rat model of acute sepsis. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:472–480. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lowes D.A., Thottakam B.M., Webster N.R., Murphy M.P., Galley H.F. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ protects against organ damage in a lipopolysaccharide-peptidoglycan model of sepsis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:1559–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Supinski G.S., Murphy M.P., Callahan L.A. MitoQ administration prevents endotoxin-induced cardiac dysfunction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R1095–R1102. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90902.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Supinski G.S., Schroder E.A., Callahan L.A. Mitochondria and critical illness. Chest. 2020;157:310–322. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Srinivasan V., Mohamed M., Kato H. Melatonin in bacterial and viral infections with focus on sepsis: a review. Recent Pat Endocr Metab Immune Drug Discov. 2012;6:30–39. doi: 10.2174/187221412799015317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Srinivasan V., Pandi-Perumal S.R., Spence D.W., Kato H., Cardinali D.P. Melatonin in septic shock: some recent concepts. J Crit Care. 2010;25:656 e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Selvaraj V., Nepal N., Rogers S., et al. Inhibition of MAP kinase/NF-kB mediated signaling and attenuation of lipopolysaccharide induced severe sepsis by cerium oxide nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2015;59:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McClelland T.J., Fowler A.J., Davies T.W., Pearse R., Prowle J., Puthucheary Z. Can pioglitazone be used for optimization of nutrition in critical illness? A systematic review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2023;47:459–475. doi: 10.1002/jpen.2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Flower L., Puthucheary Z. Muscle wasting in the critically ill patient: how to minimise subsequent disability. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2020;81:1–9. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2020.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Egan B., Zierath J.R. Exercise metabolism and the molecular regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation. Cell Metab. 2013;17:162–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hickmann C.E., Castanares-Zapatero D., Deldicque L., et al. Impact of very early physical therapy during septic shock on skeletal muscle: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:1436–1443. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schweickert W.D., Pohlman M.C., Pohlman A.S., et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874–1882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schaller S.J., Anstey M., Blobner M., et al. Early, goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:1377–1388. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31637-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hodgson C.L., Bailey M., Bellomo R., et al. TEAM Study Investigators and the ANZICS Clinical Trials Group, Early active mobilization during mechanical ventilation in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1747–1758. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2209083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Herndon D.N., Ramzy P.I., DebRoy M.A., et al. Muscle protein catabolism after severe burn: effects of IGF-1/IGFBP-3 treatment. Ann Surg. 1999;229:713–720. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199905000-00014. discussion 20–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hart D.W., Wolf S.E., Ramzy P.I., et al. Anabolic effects of oxandrolone after severe burn. Ann Surg. 2001;233:556–564. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wolf S.E., Thomas S.J., Dasu M.R., et al. Improved net protein balance, lean mass, and gene expression changes with oxandrolone treatment in the severely burned. Ann Surg. 2003;237:801–810. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000071562.12637.3E. discussion 10–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Haberecht-Muller S., Kruger E., Fielitz J. Out of control: the role of the ubiquitin proteasome system in skeletal muscle during inflammation. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1327. doi: 10.3390/biom11091327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Taylor B.E., McClave S.A., Martindale R.G., et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) Crit Care Med. 2016;44:390–438. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hurt R.T., McClave S.A., Martindale R.G., et al. Summary points and consensus recommendations from the international protein summit. Nutr Clin Pract. 2017;32(1_suppl):142S–151S. doi: 10.1177/0884533617693610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Allingstrup M.J., Esmailzadeh N., Wilkens Knudsen A., et al. Provision of protein and energy in relation to measured requirements in intensive care patients. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Deutz N.E., Wolfe R.R. Is there a maximal anabolic response to protein intake with a meal? Clin Nutr. 2013;32:309–313. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chapple L.-A.S., Kouw I.W., Summers M.J., et al. Muscle protein synthesis after protein administration in critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206:740–749. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202112-2780OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Puthucheary Z., Rooyackers O. Anabolic resistance: an uncomfortable truth for clinical trials in preventing intensive care–acquired weakness and physical functional impairment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206:660–661. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202206-1059ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Heyland D.K., Patel J., Compher C., et al. The effect of higher protein dosing in critically ill patients with high nutritional risk (EFFORT Protein): an international, multicentre, pragmatic, registry-based randomised trial. Lancet. 2023;401:568–576. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rosenthal M.D., Bala T., Wang Z., Loftus T., Moore F. Chronic critical illness patients fail to respond to current evidence-based intensive care nutrition secondarily to persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolic syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020;44:1237–1249. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rosenthal M., Gabrielli A., Moore F. The evolution of nutritional support in long term ICU patients: from multisystem organ failure to persistent inflammation immunosuppression catabolism syndrome. Minerva Anestesiol. 2016;82:84–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rosenthal M.D., Vanzant E.L., Moore F.A. Chronic critical illness and PICS nutritional strategies. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2294. doi: 10.3390/jcm10112294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Barbul A., Rettura G., Levenson S.M., Seifter E. Arginine: a thymotropic and wound-healing promoting agent. Surg Forum. 1977;28:101–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Barbul A., Sisto D.A., Wasserkrug H.L., Efron G. Arginine stimulates lymphocyte immune response in healthy human beings. Surgery. 1981;90:244–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bansal V., Ochoa J.B. Arginine availability, arginase, and the immune response. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003;6:223–228. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200303000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhu X., Pribis J.P., Rodriguez P.C., et al. The central role of arginine catabolism in T-cell dysfunction and increased susceptibility to infection after physical injury. Ann Surg. 2014;259:171–178. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828611f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rosenthal M.D., Vanzant E.L., Martindale R.G., Moore F.A. Evolving paradigms in the nutritional support of critically ill surgical patients. Curr Probl Surg. 2015;52:147–182. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Holecek M. Beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate supplementation and skeletal muscle in healthy and muscle-wasting conditions. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;8:529–541. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bar-Peled L., Sabatini D.M. Regulation of mTORC1 by amino acids. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cynober L., de Bandt J.P., Moinard C. Leucine and citrulline: two major regulators of protein turnover. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2013;105:97–105. doi: 10.1159/000341278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Heyland D., Muscedere J., Wischmeyer P.E., et al. A randomized trial of glutamine and antioxidants in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1489–1497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Haines R.W., Fowler A.J., Wan Y.I., et al. Catabolism in critical illness: a reanalysis of the REducing Deaths due to OXidative Stress (REDOXS) trial. Crit Care Med. 2022;50:1072–1082. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Pradelli L., Klek S., Mayer K., et al. Omega-3 fatty acid-containing parenteral nutrition in ICU patients: systematic review with meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24:634. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03356-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pittet Y.K., Berger M.M., Pluess T.T., et al. Blunting the response to endotoxin in healthy subjects: effects of various doses of intravenous fish oil. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:289–295. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1689-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rosenthal M.D., Patel J., Staton K., Martindale R.G., Moore F.A., Upchurch G.R., Jr. Can specialized pro-resolving mediators deliver benefit originally expected from fish oil? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2018;20:40. doi: 10.1007/s11894-018-0647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Duffield J.S., Hong S., Vaidya V.S., et al. Resolvin D series and protectin D1 mitigate acute kidney injury. J Immunol. 2006;177:5902–5911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Serhan C.N., Dalli J., Karamnov S., et al. Macrophage proresolving mediator maresin 1 stimulates tissue regeneration and controls pain. FASEB J. 2012;26:1755–1765. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-201442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Chiang N., Serhan C.N. Structural elucidation and physiologic functions of specialized pro-resolving mediators and their receptors. Mol Aspects Med. 2017;58:114–129. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Puthucheary Z., Gunst J. Are periods of feeding and fasting protective during critical illness? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2021;24:183–188. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Thiessen S.E., Van den Berghe G., Vanhorebeek I. Mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction and related defense mechanisms in critical illness-induced multiple organ failure. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863:2534–2545. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Stekovic S., Hofer S.J., Tripolt N., et al. Alternate day fasting improves physiological and molecular markers of aging in healthy, non-obese humans. Cell Metab. 2019;30:462–476. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.De Bruyn A., Gunst J., Goossens C., et al. Effect of withholding early parenteral nutrition in PICU on ketogenesis as potential mediator of its outcome benefit. Crit Care. 2020;24:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03256-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gunst J. Recovery from critical illness-induced organ failure: the role of autophagy. Crit Care. 2017;21:209. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1786-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.McNelly A.S., Bear D.E., Connolly B.A., et al. Effect of intermittent or continuous feed on muscle wasting in critical illness: a phase 2 clinical trial. Chest. 2020;158:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Van Dyck L., Casaer M.P. Intermittent or continuous feeding: any difference during the first week? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2019;25:356–362. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.de Cabo R., Mattson M.P. Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging, and disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2541–2551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1905136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Gunst J., Casaer M.P., Langouche L., Van den Berghe G. Role of ketones, ketogenic diets and intermittent fasting in ICU. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2021;27:385–389. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Puthucheary Z.A., Astin R., Mcphail M.J., et al. Metabolic phenotype of skeletal muscle in early critical illness. Thorax. 2018;73:926–935. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-211073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Thomsen H.H., Rittig N., Johannsen M., et al. Effects of 3-hydroxybutyrate and free fatty acids on muscle protein kinetics and signaling during LPS-induced inflammation in humans: anticatabolic impact of ketone bodies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108:857–867. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Shukla S.K., Gebregiworgis T., Purohit V., et al. Metabolic reprogramming induced by ketone bodies diminishes pancreatic cancer cachexia. Cancer Metab. 2014;2:1–19. doi: 10.1186/2049-3002-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Weckx R., Goossens C., Derde S., et al. Efficacy and safety of ketone ester infusion to prevent muscle weakness in a mouse model of sepsis-induced critical illness. Sci Rep. 2022;12 doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-14961-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Choi I.Y., Piccio L., Childress P., et al. A diet mimicking fasting promotes regeneration and reduces autoimmunity and multiple sclerosis symptoms. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2136–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Schuurman A.R., Kullberg R.F.J., Wiersinga W.J. Probiotics in the intensive care unit. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022;11:217. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11020217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Shimizu K., Ojima M., Ogura H. Gut microbiota and probiotics/synbiotics for modulation of immunity in critically ill patients. Nutrients. 2021;13:2439. doi: 10.3390/nu13072439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Custodero C., Mankowski R.T., Lee S.A., et al. Evidence-based nutritional and pharmacological interventions targeting chronic low-grade inflammation in middle-age and older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;46:42–59. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Maslove D.M., Tang B., Shankar-Hari M., et al. Redefining critical illness. Nat Med. 2022;28:1141–1148. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01843-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Pugh A.M., Auteri N.J., Goetzman H.S., Caldwell C.C., Nomellini V. A murine model of persistent inflammation, immune suppression, and catabolism syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1741. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Stortz J.A., Raymond S.L., Mira J.C., Moldawer L.L., Mohr A.M., Efron P.A. Murine models of sepsis and trauma: can we bridge the gap? ILAR J. 2017;58:90–105. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilx007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Shindo Y., McDonough J.S., Chang K.C., Ramachandra M., Sasikumar P.G., Hotchkiss R.S. Anti-PD-L1 peptide improves survival in sepsis. J Surg Res. 2017;208:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.08.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Jung E., Perrone E.E., Liang Z., et al. Cecal ligation and puncture followed by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia increases mortality in mice and blunts production of local and systemic cytokines. Shock. 2012;37:85–94. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182360faf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Gentile L.F., Nacionales D.C., Lopez M.C., et al. Protective immunity and defects in the neonatal and elderly immune response to sepsis. J Immunol. 2014;192:3156–3165. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Gentile L.F., Nacionales D.C., Lopez M.C., et al. Host responses to sepsis vary in different low-lethality murine models. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]