Abstract

Many cell functions require a concerted effort from multiple membrane proteins, for example, for signaling, cell division, and endocytosis. One contribution to their successful self-organization stems from the membrane deformations that these proteins induce. While the pairwise interaction potential of two membrane-deforming spheres has recently been measured, membrane-deformation-induced interactions have been predicted to be nonadditive, and hence their collective behavior cannot be deduced from this measurement. We here employ a colloidal model system consisting of adhesive spheres and giant unilamellar vesicles to test these predictions by measuring the interaction potential of the simplest case of three membrane-deforming, spherical particles. We quantify their interactions and arrangements and, for the first time, experimentally confirm and quantify the nonadditive nature of membrane-deformation-induced interactions. We furthermore conclude that there exist two favorable configurations on the membrane: (1) a linear and (2) a triangular arrangement of the three spheres. Using Monte Carlo simulations, we corroborate the experimentally observed energy minima and identify a lowering of the membrane deformation as the cause for the observed configurations. The high symmetry of the preferred arrangements for three particles suggests that arrangements of many membrane-deforming objects might follow simple rules.

Significance

Lipid-membrane-deforming objects, such as proteins, can interact through the membrane curvature they impose. These interactions have been suggested to be nonadditive; that is, one cannot extrapolate from the interaction between two objects the interactions between three or more such objects. In addition, the governing equations are so involved that there are only few and contradicting theoretical and numerical predictions. In this article, this interaction is quantified for the first time for three spherically symmetric deformations on spherical membranes through a series of experiments and Monte Carlo simulations. We find two preferred states: a linear arrangement for smaller distances and an equilateral triangle for slightly larger interparticle distances.

Introduction

Eukaryotic cells are surrounded by a phospholipid plasma membrane with proteins that make up about half of their membrane (1). The organization of these proteins into larger complexes not only plays a vital role in many functional membrane processes such as membrane trafficking, cell division, and endocytosis but may also cause disease (2,3,4). A precise understanding of the interactions between many proteins is necessary to unravel how the assembly pathway leads to functional or malignant complexes.

However, protein interactions are by no means simple. The proteins feature a complex shape and possess different physicochemical properties, which may lead to van der Waals interactions (5), electrostatics (6), or hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions (7). In addition, they may be interacting with or embedded in the cell membrane, an environment that is composed of various lipids and integral, peripheral, and cytoskeleton proteins and that can induce interactions due to Casimir-like thermal undulations of the membrane (8, 9), and membrane deformations (10). This complexity makes it difficult to selectively measure the contribution from a single interaction, such as the one stemming from membrane deformations. In addition, the small size of proteins makes it challenging to gain dynamic information about their arrangements and hence interactions.

For some interactions, such as electrostatics, a well-understood and widely tested theoretical framework is available that can be used to confidently make predictions. For membrane-deformation-based interactions, however, the governing equations are so complex that they preclude full analytical solutions. To simplify the problem, the lipid membrane is often modeled as a tensionless flat sheet that is being deformed by objects with simple shapes, such as cones, disks, or spheres. By using such an approach, it was predicted that membrane-bending-mediated interactions can provide a significant and possibly even dominant contribution to the overall interaction (10,11,12). However, theoretical analyses are restricted to linear approximations of the involved equations (10,13), making them only valid for the small perturbations regime where the membrane shape is not significantly deformed.

More recently, colloidal particles that deform lipid membranes have been employed to serve as models for quantitatively investigating membrane-mediated interactions in experiments. Using such a system, two-body interactions stemming from membrane deformations were measured for the first time and found to be attractive. However, understanding the arrangement of many particles in such systems is challenging due to the nonpairwise additive nature of these interactions (12,14). Analytical attempts to apply a first-order approximation of the indentation for three membrane-deforming objects predicted that the equilateral triangle is the most favorable arrangement, while a linear arrangement has been suggested to occur occasionally (11,15). However, these approaches also predicted a repulsion between symmetric membrane-deforming objects (10,16), which is in contrast to recent experiments on model systems and simulations that found an attraction for membrane-wrapped colloidal particles, which strongly deform the membrane (17,18,19).

Early computer simulations on flat sheets showed that a linear superposition of the curvatures induced by multiple membrane-deforming objects does not correctly reflect the energy between them (12). For spherical membrane-deforming particles whose degree of wrapping can be varied, it was found that the membrane bending energy and binding energy of the particles to the membrane determine their assembled state, which can be a linear, hexagonally ordered, or arrested aggregate (20). Interestingly, due to the many-body interactions, the linear arrangement was found to be favored for a wide range of bending rigidities (20). This linear arrangement tends to align with the direction of largest curvature, eventually forming arcs and rings that completely surround the deformed vesicle (21,22). Maybe even more surprisingly, spheres that interact with a pairwise repulsive interaction can form stable clusters on the membrane due to the nonadditive forces induced by the membrane deformations (12). Similarly, anisotropic membrane-deforming objects can assemble into different patterns, such as a linear and compact aggregates or disordered patterns (14,23,24,25). These intriguing observations from numerical calculations all originate from the nonadditive nature of the multibody interactions, but even the simplest case of three membrane-deforming particles has never been experimentally investigated.

We here employ an experimental model system consisting of giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) and adhesive colloidal particles (18,19) to study the configurations of three membrane-deforming, spherical objects. Our experimental setup allows us to single out membrane-deformation-induced interactions. We quantitatively measure the particle positions in time in 3D using confocal microscopy and extract the free energy landscape for the three-particle case for the first time. To better understand the nature of this interaction, we carry out Monte Carlo simulations of three membrane-deforming colloids and sample the energy at various colloid distances. The simulations quantitatively agree with experiment and allow us to identify the origin of the preferred particle arrangements to be the reduction in membrane bending energy in the neck region upon approach of the particles. The simplified particle shape and controlled membrane deformation by each particle allow us to draw conclusions about the nonadditive nature of membrane-bending-induced interactions.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) tablets, chloroform (99%), styrene (99%), itaconic acid (99%), sodium phosphate (99%), D-glucose (99%), 4,4′-azobis(4-cyanovaleric acid) (98%), N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide sodium salt (98%), 1,3,5,7-tetramethyl-8-phenyl-4,4-difluoro-bora-diaza-indacene (BODIPY; 97%) deuterium oxide (70%), and bovine serum albumin (BSA) (98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); sodium azide (99%) was obtained from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), methoxypoly(ethylene) glycol amine (molecular weight = 5000) from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimid hydrochloride (99%) from Carl Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany), NeutrAvidin (avidin) from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[biotinyl(polyethylene glycol)-2000], 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (DOPE-rhodamine), from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA) and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All chemicals were used as received. Deionized water obtained from a Millipore Filtration System (Milli-Q Gradient A10) with resistivity 18.2 M cm was used in all experiments.

Vesicle preparation

GUVs were prepared using a standard electroformation method. A lipid mixture containing 97.5 wt % DOPC, 2.0 wt % DOPE-polyethylene glycol (PEG)2000-biotin, and 0.5 wt % 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) was dissolved in chloroform to make a 1 g/L stock solution. Then, 10 μL this solution was deposited as a thin layer on two indium-tin-oxide-coated glass slides by spin coating. The coated glasses were dried for at least 2 h in a desiccator at low vacuum to evaporate the organic solvent. After that, the slides were immersed in a solution of 100 mM glucose in 49:51 D2O:H2O. For electroswelling, an alternating electric field of 500 V/mm at 10 Hz was applied to the electrodes for 1.5 h, after which the frequency was reduced to 6 Hz to increase production efficiency for the next 30 min. Eppendorf tubes were coated with a 1 g/L BSA solution to reduce adhesion. To remove undesirable lipid structures such as tubes and small vesicles, the GUV solution was carefully mixed with 100 mOsm/kg PBS, and GUVs were allowed to sediment. After 10 min, the supernatant was removed. PBS was made by dissolving a PBS tablet in water to 100 mOsm/kg. To offset the buoyancy of polystyrene particles and GUVs in the final sample we adjusted the density of the PBS with D2O:H2O. Osmolarity was adjusted with an osmometer (GonoTec Osmometer Model 3000). All procedures were done at room temperature.

Colloidal particle preparation

Polystyrene (PS) particles with a dense functionalization of carboxylic acid groups were synthesized using a surfactant-free dispersion polymerization as detailed in (26), resulting in monodisperse colloidal spheres with a diameter of 0.98 0.03 μm and a polydispersity of 3.3%. Following the synthesis, these PS particles were coated with Neutravidin and methoxypoly(ethylene) glycol amine 5000 following a protocol that was shown to yield a surface coverage of Neutravidin of μm−2 (18,27). Particles were dyed with fluorescent BODIPY dye throughout, following the protocol of (27). The particles have a small negative charge of −18 4 mV in PBS solution, which, together with a Debye length of 1 nm, ensures that electrostatic interactions are negligible in the experiments (18,27).

Microscopy and optical trapping

An inverted Ti-E Nikon microscope equipped with a 60 water immersion (NA = 1.2) objective lens was used to capture confocal images with an A1R confocal head. Resonant mode was employed to capture (video) images of 512 256 pixels at 15 kHz line scanning speed, equivalent to 59 frames/s. The image sequence performed in a 3× zoom, which yielded a pixel size of 136 nm/pixel. A 488 nm laser was used to excite the BODIPY dye inside the particles (depicted in green in Fig. 1), and the emission was detected between 500 and 550 nm. Simultaneously, a 561 nm laser was used to excite the rhodamine dye attached to a small fraction of lipids (0.5 wt %, depicted in magenta in Fig. 1) and the emission was collected between 580 and 630 nm. To control the optical leakage between the channels, we applied a negative voltage to the photomultiplier detectors. This approach effectively minimized the otherwise significant cross talk between the green (BODIPY) and magenta (rhodamine) channels. The microscope stage is mounted on a Madcity LAB nano Piezo z-positioner that can move the stage in the range of a hundred micrometers with high precision and speed. Images were acquired in two separate and independent channels.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup for measuring membrane-mediated interactions between three spherical, membrane-deforming particles. (a) Schematic of the model system that consists of giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs; depicted in magenta) and membrane-wrapped polystyrene spheres (depicted in green), three of which are positioned on top of the vesicle using optical tweezers. (b) Three-dimensional reconstruction of a confocal image of a hemisphere of a diameter GUV with three wrapped particles. (c) Detailed schematic of particle and membrane functionalization and membrane-wrapped configuration (not to scale). 1-DOPC lipid 2-DOPE lipid 3-biotin 4-Neutravidin 5-rhodamine 6-polyethylene glycol (PEG) 7-polystyrene particle. (d) Depiction of the definition of the parameters used to describe particle arrangement on the membrane, where r is the geodesic curve connecting two particles on the vesicle surface, is the geodesic curve from the middle of r to the center of the third particle, and θ is the angle between r and . (e–g) Membrane wrapping of colloids can be identified using different dyes and separate fluorescent detection channels, (e) membrane fluorescence is detected between 580 and 630 nm, and (f) particle fluorescence is detected between 500 and 550 nm; (g) an overlay of both channels allows identification of overlap of membrane and particle fluorescence by the white color. Scale bar: 2 μm. (h) Temporal evolution of three membrane-wrapped particles on the top of a GUV shortly after turning the optical tweezers off, illustrating a typical data set. Scale bar: 5 μm. Time t is indicated in the stills. To see this figure in color, go online.

We used home-built optical tweezers to bring the particles one by one to the top of the vesicle at the start of each experiment. Our optical tweezers consisted of a highly focused laser beam (Laser QUANTUM Opus with 1064 nm) that was integrated into the confocal microscope through the fluorescent port and merged into the microscope light path with an infrared short-pass filter. The same objective was used for confocal imaging and focusing the trapping beam inside the sample; the correction collar of the objective was set slightly lower than the real thickness of the coverslip to reduce the spherical aberration (28). The light intensity employed during the experiments was carefully controlled at 1 mW to ensure that it did not result in a significant increase in the local temperature (29).

Sample and chamber preparation

20 mm diameter glass coverslips were coated with 1 g/L BSA solution and then washed three times with PBS buffer. We also tested a polyacrylamide-coated coverslip and did not observe a significant difference in the result. Throughout this work, BSA-coated coverslips were used. GUVs were mixed gently with colloidal particles dispersed in isotonic PBS buffer to prevent spontaneous tube formation on the membrane. Then, the mixture was injected into a custom-made, round, 10 mm diameter microscope sample holder equipped with a BSA-coated coverslip on the bottom. The vesicles were allowed to sediment to the cover glass before positioning the colloidal particles and imaging. We achieved a decrease in the GUV tension, which is needed for particle wrapping, by keeping the sample holder open for a period of 30–45 min. The evaporation of water leads to a gradual increase of the ion concentration of the outer solution, which creates an osmotic pressure difference between the inside and outside of the GUV and hence a decrease in the GUVs’ tension.

We excluded nonspherical GUVs where the diameter of vesicles in any of the directions deviated by more than 10% for two reasons: (1) there might be an anisotropic force due to the elongation of membrane (22), and (2) the higher symmetry simplifies the analysis in that it reduces the problem from to and hence requires less data.

Image analysis and particle tracking

Particle position in the acquired (video) images were obtained using the Python-based software package Trackpy 0.5.0 (30). The software traces fluorescent particles by finding their center of mass using a Gaussian fit in x and y with subpixel resolution. At the start of each experiment, membrane size and position were extracted from a 3D image stack using a Python routine called “circletracking” that finds the vesicle center and contour with subpixel precision (31). The particles’ confinement to the membrane enabled us to retrieve their 3D position from their two-dimensional x-y coordinates (18,32). Membrane tension was measured from the fluctuation spectrum of several image sequences taken in the equatorial plane of the vesicle, following (33). To achieve a better fit, we have assumed a fixed bending rigidity of 22 kBT for a vesicle composed mainly of DOPC (34). All vesicles had a membrane tension σ 10 nN/m and were designated as “floppy” with visible waves greater than 1 μm in (18). The bendocapillary length scale () is over 3 μm for such a floppy vesicles. An example and further details are shown in Fig. S6.

Simulations

Coarse-grained Monte Carlo (MC) simulations of the membrane-colloid system were carried out using a previously developed triangulated fluid membrane model (18,20,35,36). This consists of a network of triangles with 5882 vertices that dynamically undergo MC moves involving translation of vertices and edge swapping. Each move is associated with an energy change calculated from the angles between the normals of the triangles and their area, which, together with the edge swapping, can replicate the bending rigidity, tension, and fluidity of biological membranes. Each move is accepted according to the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm, satisfying detailed balance. Between the vertices, there is a hard-core volume exclusion where the minimum distance between vertices is . We choose a membrane bending rigidity and membrane tension (1). For , this corresponds to a tension of . Colloids have been modelled to have a hard-core volume exclusion combined with an attractive potential interaction with the membrane and a hard-core volume exclusion with other colloids. The attraction takes the form (2), where d is the distance between the center of the colloid and a membrane vertex, is the diameter of the colloid, and ϵ, the strength of the interaction, is chosen to be 7kBT to ensure full and tight wrapping of the colloids by the membrane. The attraction is cut off at (3), after which it is zero. In contrast to earlier work, where the colloids are not fully wrapped by the membrane, (20,37,38) the colloids here are close to 100% wrapped with a very tight neck (see Figs. 3, b, top, and S4 for high-resolution renderings of the neck conformations), which closely resembles the experimental setup. Indeed, we confirm the theoretically predicted behavior of a discontinuous transition from semi-wrapped to fully wrapped as adhesion energy per colloid area is increased (39). To measure the potential energy for different configurations of the three colloids, we tether each colloid using a stiff harmonic spring at a chosen fixed angle with respect to the center of the vesicle and vary these angles to sample different configurations. The colloids are free to move in the radial direction and can be wrapped by the membrane. We run 20 seeds (with different randomized MC realizations) per fixed distance between the 3 colloids and obtain an averaged potential energy profile, each data point being an average of roughly 40,000 measurements, which are each an average of 2000 MC steps. We eliminate variable binding energy by first creating bins of data with the same total binding energy, averaging each bin independently, and then plotting the mean of these averages. When we plot the bending energy of the membrane as a function of arc distance, we average the membrane bending per bead for a strip which is wide and follows the arc that is defined by either r or (see Fig. 3). Simulations are performed in the canonical ensemble.

Figure 3.

Comparison between simulations and experiments. (a and c) Measurements of the change in bending and stretching energy () obtained by simulations (solid lines) and experiments (dotted lines, same data as shown in Fig. 2) as a function of for (a) the linear arrangement and (c) for the triangular arrangement, where D is the diameter of the colloid. (a) In the linear regime, there is a minimum at for a range of r in both simulation and experiment. Simulation snapshots of the linear configuration are shown on the right. (c) For the triangular arrangement, we find a minimum at for in simulation, while experiments yielded a minimum at and . Simulation snapshots of the triangular configuration are shown on the right. Error bars for the simulation measurements (shaded area) in (c) and (d) are calculated from the standard error. (b and d) Bending energy per membrane bead in simulation as a function of distance to the midpoint between the first two colloids for the (b) linear and (d) triangular states. We average the energy per membrane bead of a strip of membrane beads that is wide along the arcs defined by r and , not including the colloid-bound membrane beads. This allows us to visualize the three membrane necks as three peaks in energy-distance space. (b) The energy of the middle membrane neck is lower for the energy minimal configuration of and . (d) The neck energy reduction is less pronounced, but the zoomed inset shows that the energy minimum stems from a reduction in the neck energies at intermediate . To see this figure in color, go online.

Results and discussion

To quantitatively investigate how three membrane-deforming objects interact, we use an experimental model system consisting of model lipid membranes realized by GUVs with diameters ranging between 20 and 25 and membrane-adhering and -deforming colloidal particles (18). We induce adhesion between the colloids and the GUV by employing diameter PS spheres, in the following also referred to as colloids or colloidal particles (18,27), functionalized with μm−2 Neutravidin and stabilized against spontaneous aggregation with PEG 5000 as described in (18). GUVs were equipped with 2% w/w PEG-biotinylated lipids (see materials and methods for details and Fig. 1, a–c). PEG molecules were employed to prevent the nonspecific adhesion between the vesicle and the colloids. Additionally, to offset the buoyancy of PS colloids, we carefully matched the solution density by incorporating heavy water (D2O) (see materials and methods for more details).

Once attached to the membrane, the colloids can become fully wrapped by both leaflets of the membrane (see Fig. 1 c). This happens for sufficiently low surface tensions, σ, and when the adhesion energy per colloid surface area, , is larger than the bending energy, , required to deform the membrane with bending rigidity, κ (18,32,40,41). We achieve the latter by leaving our sample holder open such that gradual evaporation of water, which slowly increases the osmolarity of the outer fluid, leads to a deflation of the vesicles over the course of about 30 min. This deflation causes the membrane tension to lower to a level below 10 nN/m. Wrapped particles induce a spherically symmetric membrane deformation and can interact through this deformation (18,42).

We validate that colloids have been wrapped by the membrane with confocal microscopy. To this end, lipid membranes are labeled using rhodamine B (see Fig. 1 e, shown in magenta), colloids are dyed with BODIPY (see Fig. 1 f, shown in green), and we imaged both GUVs and colloids simultaneously in separate fluorescence channels. Overlapping signals of membrane and colloids lead to a white color (Fig. 1 g). The position of the colloidal particles with respect to the vesicle membrane allows clear distinction between wrapped and unwrapped particles (see Fig. 1, b and g). Instead of relying on diffusion-based random adhesion to the lipid membrane only, we also employ optical tweezers to bring the colloidal particles in contact with the GUV. This allows us to speed up not only the adhesion process of particles on the GUV but also their wrapping by the membrane (32).

To simultaneously and at high speed image the conformations and interactions of three membrane-deforming colloidal particles by confocal microscopy, the particles need to be at roughly the same focal depth (Fig. 1 h; Video S1). We achieve this by randomly positioning three wrapped particles with optical tweezers on top of the vesicle (Fig. 1, a and h) at the start of each experiment. A few seconds after releasing the confinement imposed by the optical tweezers, we extracted their x and y positions in time using Python-based image analysis routines (see materials and methods for details). Knowledge about the GUV size and position and the wrapping state allows us to infer the z-position of the colloidal particle from their x and y coordinates and hence use the much-faster 2D imaging.

We characterize the relative positions of the three interacting particles using three parameters: (1) r is defined as the geodesic between two particles, (2) is defined as the geodesic line from the middle of r to the third particle, and (3) θ is the angle between r and , schematically depicted in Fig. 1 d. To extract the free energy associated with different particle arrangements on the membrane from their positional data, different methods are available in the literature. Some of these methods require a long continuous trajectory (43,44), which makes it not possible to use them for such experiments where the particles might move out of the microscope’s focus and disappear from the field of view. Maximum-likelihood analyses of particle trajectories circumvent this problem but require an assumption of the three-body interaction potential and diffusion coefficient in advance (45). Here, we therefore used a standard Boltzmann statistics approach that only requires us to obtain information about the particles’ position, albeit at the cost of large amounts of data. We collected data from a total of 25 distinct vesicles with diameters between 20 and 25 μm and recorded more than one video of about 1 min per vesicle to ensure sufficient statistics for our analysis. During acquisition, we manually adjusted the focal height to follow the particles. Sedimentation of the particles was negligible due to density matching of the solvent to the particles. We split the data according to the geodesic distance along the vesicle between any two particles, r, into bins of m in a range from m. This bin size ensures good statistics by containing each at least 22,000 data points while at the same time being reasonably small with respect to the microscope resolution. This approach is equivalent to considering a probe particle that explores the interaction with two particles located within a fixed geodesic distance . Moreover, θ can vary from to , but all data can be mirrored to one quarter due to its symmetry (Fig. 2 a).

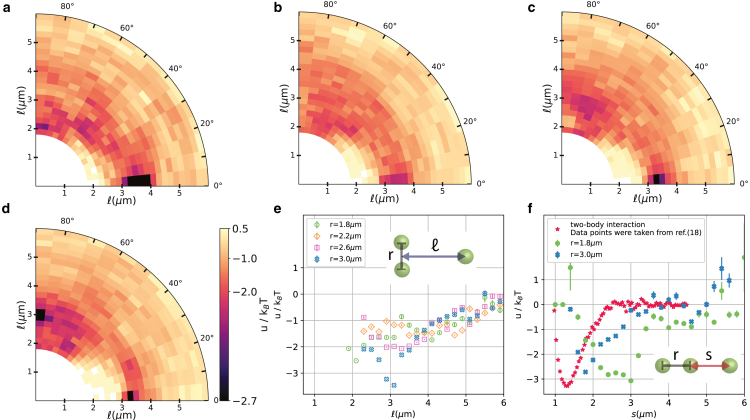

Figure 2.

Free energy u for three membrane-deforming spheres as a function of the geodesic distance and angle θ as defined in Fig. 1 where two particles are located at on the horizontal axis. Polar plot of the free energy for (a) m, (b) m, (c) m, and (d) m. (e) Free energy in T as a function of for the triangular arrangement, i.e., ; a switch from an arrangement of the three spheres along a geodesic of the vesicle (linear arrangement) to an equilateral triangle at larger values of r is visible. (f) Free energy in T as a function of distance s defined as shown in the inset schematic for the three particles to be arranged along a geodesic, i.e., (blue crosses) and for m (green circles) and m; in addition, the free energy for two membrane-deforming spheres is shown (red stars, taken from (18)) for comparison. Error bars of the data points are equal to or smaller than the size of the symbols and are standard deviations. To see this figure in color, go online.

Using this approach, we infer the free energy of three particles for four values of the distance between any two particles, r, and plot them as a function of the distance and angle θ of the third particle with respect to the center the two other particles (see schematic shown in Fig. 1 d). The color scale was scaled as a power law with power 0.3 for better visual presentation, with darker colors corresponding to a lower free energy. For the smallest value of m, the most likely arrangement is along a geodesic curve, with one particle being located at a geodesic distance of about 3.5 0.6 μm from the center of the other two particles (Fig. 2 a). Intriguingly, the distances between the three particles in the linear configuration are larger than those previously found for two particles, which was about 1.25 μm (18). Additionally, the maximum strength of the interaction between two particles was previously measured to be −3.3 T, which is similar to the value of −3.0 0.2 T that we find for the linear three-body configuration here. Arrangements with smaller values of r were so infrequently observed that we were unable to measure the free energy with high precision, and hence we do not report them here. Thus, our data suggest that the linear arrangement occurs at slightly larger distances and with nearly equal interaction strength compared to the two-body scenario. As r increases to 2.0 0.2 μm, the configuration along a geodesic curve of the three spheres is still the most likely state (Fig. S1 a) and persists even for larger values of r = 2.2 0.2 μm (Fig. 2 b) and 2.4 0.2 μm (Fig. S1 b).

A second preferred configuration appears when moving the two particles even further apart to and m (see Figs. 2 c and S1 c). This arrangement is equivalent to a triangular arrangement of the three spheres. Initially, the second minimum corresponding to the triangular configuration is shallow with respect to T, allowing particles to easily escape. Upon a further increase of the distance between the two particles, however, the minimum belonging to the linear arrangement () becomes less dominant, and the triangular arrangement at r and m and becomes energetically preferred, albeit by a small difference (Fig. 2, d and f). This becomes more clear when we plot the free energy for the triangular state as a function of the distance of the third particle for all distances r (see Fig. 2 e). Only for the largest distance m is the equilateral triangle preferred, with a minimum free energy of about −3.2 T at about m. However, the minimum has a broader width than the linear configuration. While a free energy minimum was found for all values of r in the triangular state, the most pronounced minimum is that for m (see Fig. 2 e). In this state, the three spheres are arranged in an equilateral triangle: two spheres have a distance m, which, for a perfect equilateral triangle, would require m. We find m from the experiments, which agrees within the error with an equilateral triangle configuration.

Our experimental observations of a linear arrangement and equilateral triangle of three membrane-deforming spheres on a closed lipid membrane have never been reported before in experiments. They are in line, however, with the observation of hexagonal arrangements found by Ramos et al. for negatively charged particles physisorbed onto oppositely charged surfactant vesicles (46). Besides the vesicle not being made from lipids, in the same work, irreversible aggregation of colloidal particles was reported—in contrast to our observations for membrane-wrapped particles here and earlier (18), and it is unclear whether these particles interacted purely through deformations. For our system, irreversible aggregation only occurred in the presence of spurious lipid structures or for combinations of wrapped and nonwrapped particles (42). Even more so, the energy differences between the different configurations are small, allowing free reconfiguration between all possible arrangements due to the thermal energy. See also Fig. 1 h for a time series during which the three particles adopt various arrangements and Video S1.

Our observations of a coexistence of linear and triangular arrangements on closed spherical lipid membranes have also never before been reported in analytical or numerical work. In fact, there are only a few reports in the literature that consider many objects that interact through deformations on spherical membranes (20,47) because most assume flat sheets for simplicity (11,12). Yet, this seemingly straightforward simplification may lead to different results, as was shown for two-body interactions (48,49). Being aware of this, and keeping in mind that these works predicted a repulsion between two deformations, we still would like to point out that early analytical work on three membrane-deforming objects on tensionless flat sheets found that their interaction depended on their precise arrangement and that the free energy was predicted to have maximum repulsion for an equilateral triangle (11,15).

Previous numerical work that most closely captures the physics of our experimental model system considered adhesive nanoparticles on flat and spherical membranes (20). These numerical calculations found a preference for linear arrangements at bending rigidities ranging from 10 to 100 T, which is the regime our GUV membrane falls into. For lower and higher bending rigidities, hexagonal arrangements were found. This preference was attributed to the higher gain in adhesion energy compared to the bending energy costs for the linear arrangement compared to the hexagonal one. Free energy calculations for three particles on flat membranes with two particles in close contact and the third one coming in linearly or in a triangular orientation confirmed a preference for the linear arrangement. However, larger values for r were not considered, which might have shown both the linear and the triangular state we observe in the experiments. In addition, the nanoparticles considered in this work were never found to be fully wrapped by the membrane but rather deformed the membrane to a maximum of about half their size.

To better understand the effect of an additional object on the two-body interaction as well as the nonpairwise nature of the interaction, in Fig. 2 f, we plotted the free energy of the three particles arranged in a line in a different way, namely as a function of . This allows us to compare our data more easily to the two-body interaction data measured previously in (18). This way of presenting the data is equivalent to considering the two-body interaction in the presence of a third particle, when all particles are arranged on a line, since the direction of the membrane-deformation-induced forces is parallel to this line. Interestingly, at short distances of m, the interaction free energy with the third particle is clearly not simply an addition of the interactions with two spheres at a distance s and . Instead, the magnitude of the interactions is comparable to what has been found for two spherical particles that deform the membrane in a similar way. Secondly, in contrast to pure two-body interactions, the minimum of the interaction is shifted to larger distances s and features a broader interaction range with roughly 1.2 μm (see Fig. 2 f). When the third particle is further away, i.e., for r = 3.0 μm, the minimum of the interaction potential moves to smaller values and closer to the value found for pure two-body interactions. In the case of a third particle located at infinite distance the potential of the two-body interaction is expected to be recovered. Therefore, we find that the effect of a third particle on the interaction of two particles is perturbs the equilibrium distance between them. This is stronger the closer the third particle is to the interacting pair. This finding clearly highlights and confirms experimentally for the first time the predicted nonadditive nature of the interaction.

To investigate these interactions further, we performed MC simulations consisting of a triangulated fluid membrane and adhesive colloids (see materials and methods for details). We focus on interactions where each colloid wraps individually and then interacts with other individually wrapped colloids. Due to the thermal noise in the system, it is challenging to measure interactions of the order of a few T found in experiment. The biggest source of noise measured in the energy in simulations is from variable colloid-membrane binding. When just one membrane bead binds or unbinds from a colloid in the wrapped state, there is a large difference in the energy. To mitigate this, we choose to measure the potential energy at constant binding. This is likely reflective of the experiments, where binding is irreversible due to the strong interaction between the biotin-Neutravidin linkers. We compare the potential energy differences measured in simulation to the free energy differences measured in experiment. The simulations reproduce the energy minima found in experiment remarkably well, suggesting that the interactions measured in experiment are neither entropic nor due to variable binding.

Fig. 3a shows simulation results alongside experimental results for the interaction between three colloids in the linear arrangement. The difference in bending energy and energy due to surface tension, , is plotted as a function of the distance between the third colloid and the midpoint between the first two colloids, (see Fig. 3 a, top right snapshot). We find a minimum for and at fixed , which reflects the findings from experiment for and , respectively. This favourable configuration is shown in the bottom snapshot in Fig. 3 a. Fig. 3 c shows the simulation and experimental results for the triangular state, where is plotted as a function of the same parameter, (see Fig. 3 c, top right snapshot). This interaction was more difficult to capture in simulations, as can be seen by the noise in the interaction profile. However, we see a pronounced minimum for and that probably reflects the only minimum found in experiment at slightly smaller and .

The advantage of these simulations is that we can look into where the interactions are coming from. To begin to explore this, we first revisited a system with only two membrane-deforming colloids. As can be seen in Fig. S2, the potential energy is minimal for the closest colloid-colloid distance we could simulate, , and is dominated by differences in bending energy, reflecting experiments and confirming previous simulation results (18). To interrogate the source of this interaction, we plot the local bending energy of the membrane as a function of arc distance from the center of the two colloids for different colloid configurations (see materials and methods for details). From this, we find that the tightest, highly bent part of the neck has a lower bending energy at close colloid-colloid distances. This is further illustrated by plotting histograms of membrane bending energy per membrane bead as shown in Fig. S3, and we find that this comes from a slight increase of the circumference of the neck opening (see Fig. S5).

Turning to the case of three colloids, we find analogous results. We again plot the average bending energy per membrane bead as a function of arc distance (see Fig. 3, b and d). In the linear regime, the two closest colloids have a lower membrane bending energy at the neck than the membrane neck of the furthest colloid (see neck 1 and neck 2 versus neck 3 in Fig. 3 b), directly reflecting the two colloid interaction. There is another reduction in the membrane neck bending energy of the middle colloid when the third colloid is an intermediate distance away (see neck 2: vs. Fig. 3 b). The bending energy differences between configurations in the triangular state also come from a reduction in bending energy of the tightest part of the neck, this time for all three necks (see Fig. 3 d). We expected to find these interactions mediated by the membrane area between the necks, but instead we find that it is mediated by the tightest part of the membrane necks. The two colloid and three colloid interactions have the same source, a reduction in bending of the membrane necks. Yet, the three-colloid potential minimum is for colloid-colloid distances that are larger than the distance of the two-colloid potential minimum, highlighting the nonadditive nature of this interaction.

Conclusions

We employed a model system consisting of colloidal particles and GUVs to measure the membrane-mediated interactions between three membrane-deforming, spherical objects. We found two distinct configurations for three particles on the membrane driven by minimization of the membrane bending energy: a linear arrangement and an equilateral triangular configuration at slightly longer distances. The minimum of the free energy was in both cases found to be around −3 T. We confirmed and quantitatively investigated the nonadditive interaction of the particles on spherical membranes for the first time and found that the third particle does not enhance the interaction but instead pushes the minimum toward a larger distance.

Extrapolating beyond two and three membrane-deforming objects, the simplicity of our observations of only two states, linear and equilateral triangular, and their high symmetry in the particle arrangement suggest that many-body arrangements might either be hexagonal lattices or lines or a combination of both. This is similar to early, albeit different because it is possibly not based on membrane-bending-mediated interactions only, experimental work (46) and numerical predictions on flat (11) and spherical membranes (20). We stress, however, that this is a hypothesis only that still needs to be tested, either in experimental model systems or numerical simulations.

Author contributions

A.A. and D.J.K. designed the experiment. A.A. carried out the experiments and analysis of the data. D.J.K. conceived the experiments and supervised experiments and data analysis. B.M. and A.Š. designed the simulations. B.M. and J.M. carried out the simulations, and A.Š. supervised the simulations. A.A., B.M., A.Š. and D.J.K. contributed to writing the article.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge useful discussions with Casper van der Wel, help by Yogesh Shelke with PAA coverslip preparation, and support by Rachel Doherty with particle functionalization. A.A. and D.J.K. would like to thank Timon Idema and George Dadunashvili for initial attempts to simulate the experimental system. D.J.K. would like to thank the physics department at Leiden University for funding the PhD position of A.A. B.M. and A.Š. acknowledge funding by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (ERC starting grant no. 802960).

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Editor: Rumiana Dimova.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2023.12.020.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Chaffey N., Alberts B., et al. Walter P. Molecular biology of the cell, 4th edition. Ann. Bot. 2003;91:401. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irvine G.B., El-Agnaf O.M., et al. Walsh D.M. Protein aggregation in the brain: The molecular basis for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Mol. Med. 2008;14:451–464. doi: 10.2119/2007-00100.Irvine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashraf G.M., Greig N.H., et al. Kamal M.A. Protein Misfolding and Aggregation in Alzheimer’s Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. CNS Neurol. Disord.: Drug Targets. 2014;13:1280–1293. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666140917095514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfefferkorn C.M., Jiang Z., Lee J.C. Biophysics of α-synuclein membrane interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roth C.M., Neal B.L., Lenhoff A.M. Van der Waals interactions involving proteins. Biophys. J. 1996;70:977–987. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79641-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Z., Witham S., Alexov E. On the role of electrostatics in protein-protein interactions. Phys. Biol. 2011;8 doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/8/3/035001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Killian J.A. Hydrophobic mismatch between proteins and lipids in membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1376:401–415. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(98)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golestanian R., Goulian M., Kardar M. Fluctuation-induced interactions between rods on membranes and interfaces. Europhys. Lett. 1996;33:241–246. doi: 10.1103/physreve.54.6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pezeshkian W., Gao H., et al. Shillcock J.C. Mechanism of Shiga Toxin Clustering on Membranes. ACS Nano. 2017;11:314–324. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b05706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goulian M., Bruinsma R., Pincus P. Long-Range Forces in Heterogeneous Fluid Membranes. Europhys. Lett. 1993;23:155. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park J.M., Lubensky T.C. Interactions between membrane inclusions on fluctuating membranes. J. Phys. I France. 1996;6:1217–1235. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim K.S., Neu J., Oster G. Curvature-mediated interactions between membrane proteins. Biophys. J. 1998;75:2274–2291. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77672-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yolcu C., Haussman R.C., Deserno M. The Effective Field Theory approach towards membrane-mediated interactions between particles. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;208:89–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dommersnes P.G., Fournier J.B. N-body study of anisotropic membrane inclusions: Membrane mediated interactions and ordered aggregation. Eur. Phys. J. B. 1999;12:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yolcu C., Deserno M. Membrane-mediated interactions between rigid inclusions: An effective field theory. Phys. Rev. 2012;86 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.86.031906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dommersnes P.G., Fournier J.B., Galatola P. Long-range elastic forces between membrane inclusions in spherical vesicles. Europhys. Lett. 1998;42:233–238. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynwar B.J., Illya G., et al. Deserno M. Aggregation and vesiculation of membrane proteins by curvature-mediated interactions. Nature. 2007;447:461–464. doi: 10.1038/nature05840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Wel C., Vahid A., Kraft D.J., et al. Lipid membrane-mediated attraction between curvature inducing objects. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep32825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarfati R., Dufresne E.R. Long-range attraction of particles adhered to lipid vesicles. Phys. Rev. E. 2016;94 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.94.012604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarić A., Cacciuto A. Fluid membranes can drive linear aggregation of adsorbed spherical nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;108:118101–118105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.118101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koltover I., Rädler J.O., Safinya C.R. Membrane mediated attraction and ordered aggregation of colloidal particles bound to giant phospholipid vesicles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999;82:1991–1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vahid A., Šarić A., Idema T. Curvature variation controls particle aggregation on fluid vesicles. Soft Matter. 2017;13:4924–4930. doi: 10.1039/c7sm00433h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dommersnes P.G., Fournier J.B. The many-body problem for anisotropic membrane inclusions and the self-assembly of "saddle" defects into an "egg carton". Biophys. J. 2002;83:2898–2905. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olinger A.D., Spangler E.J., et al. Laradji M. Membrane-mediated aggregation of anisotropically curved nanoparticles. Faraday Discuss. 2016;186:265–275. doi: 10.1039/c5fd00144g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simunovic M., Srivastava A., Voth G.A. Linear aggregation of proteins on the membrane as a prelude to membrane remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:20396–20401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309819110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Appel J., Akerboom S., et al. Sprakel J. Facile one-step synthesis of monodisperse micron-sized latex particles with highly carboxylated surfaces. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2013;34:1284–1288. doi: 10.1002/marc.201300422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Wel C., Bossert N., et al. Kraft D.J. Surfactant-free Colloidal Particles with Specific Binding Affinity. Langmuir. 2017;33:9803–9810. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b02065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reihani S.N.S., Mir S.A., et al. Oddershede L.B. Significant improvement of optical traps by tuning standard water immersion objectives. J. Opt. 2011;13 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peterman E.J.G., Gittes F., Schmidt C.F. Laser-induced heating in optical traps. Biophys. J. 2003;84:1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74946-7. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006349503749467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allan D.B., Caswell T., et al. Verweij R.W. 2021. Soft-Matter/Trackpy. Trackpy v0.5.0. [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Wel C. 2016. circletracking v1.0. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azadbakht A., Meadowcroft B., et al. Kraft D.J. Wrapping Pathways of Anisotropic Dumbbell Particles by Giant Unilamellar Vesicles. Nano Lett. 2023;23:4267–4273. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c00375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pécréaux J., Döbereiner H.G., et al. Bassereau P. Refined contour analysis of giant unilamellar vesicles. Eur. Phys. J. E Soft Matter. 2004;13:277–290. doi: 10.1140/epje/i2004-10001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faizi H.A., Reeves C.J., et al. Dimova R. Fluctuation spectroscopy of giant unilamellar vesicles using confocal and phase contrast microscopy. Soft Matter. 2020;16:8996–9001. doi: 10.1039/d0sm00943a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Šarić A., Cacciuto A. Mechanism of membrane tube formation induced by adhesive nanocomponents. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109:188101–188105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.188101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Šarić A., Cacciuto A. Self-assembly of nanoparticles adsorbed on fluid and elastic membranes. Soft Matter. 2013;9:6677–6695. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bahrami A.H., Weikl T.R. Curvature-Mediated Assembly of Janus Nanoparticles on Membrane Vesicles. Nano Lett. 2018;18:1259–1263. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b04855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynwar B.J., Deserno M. Membrane-mediated interactions between circular particles in the strongly curved regime. Soft Matter. 2011;7:8567–8575. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raatz M., Lipowsky R., Weikl T.R. Cooperative wrapping of nanoparticles by membrane tubes. Soft Matter. 2014;10:3570–3577. doi: 10.1039/c3sm52498a. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2014/sm/c3sm52498a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spanke H.T., Style R.W., et al. Dufresne E.R. Wrapping of Microparticles by Floppy Lipid Vesicles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020;125:198102–198109. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.198102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spanke H.T., Agudo-Canalejo J., et al. Dufresne E.R. Dynamics of spontaneous wrapping of microparticles by floppy lipid membranes. Phys. Rev. Res. 2022;4 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.198102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Wel C., Heinrich D., Kraft D.J. Microparticle Assembly Pathways on Lipid Membranes. Biophys. J. 2017;113:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frishman A., Ronceray P. Learning Force Fields from Stochastic Trajectories. Phys. Rev. X. 2020;10 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gnesotto F.S., Gradziuk G., et al. Broedersz C.P. Learning the non-equilibrium dynamics of Brownian movies. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5378. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18796-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarfati R., Bławzdziewicz J., Dufresne E.R. Maximum likelihood estimations of force and mobility from single short Brownian trajectories. Soft Matter. 2017;13:2174–2180. doi: 10.1039/c7sm00174f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramos L., Lubensky T.C., et al. Weitz D.A. Surfactant-mediated two-dimensional crystallization of colloidal crystals. Science. 1999;286:2325–2328. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2325. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/286/5448/2325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bahrami A.H., Lipowsky R., Weikl T.R. Tubulation and aggregation of spherical nanoparticles adsorbed on vesicles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109:188102–188105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.188102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vahid A., Idema T. Pointlike Inclusion Interactions in Tubular Membranes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;117:138102–138105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.138102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Idema T., Kraft D.J. Interactions between model inclusions on closed lipid bilayer membranes. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;40:58–69. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.