Abstract

Agriculture is among the most dangerous industries in the U.S., yet routine surveillance of injury hazards is not currently being conducted on a national level. The objectives of this study were to describe a new tool, called the Hazard Assessment Checklist (HAC), to identify and characterize farm hazards that increase injury risk to farmers and farm workers, and (2) report the inter-rater reliability of the new tool when administered on row-crop farms in Iowa. Based on a literature review and a consensus of expert opinion, the HAC included hazards related to self-propelled vehicles, powered portable implements, fixed machinery and equipment, farm buildings and structures, fall risks, and portable equipment associated with fall risk. A scoring metric indicating the extent of compliance with recommended safety guidelines and standards was developed for each item of the HAC, which included compliant, minimal improvement needed, substantial improvement needed, and not compliant. Inter-rater reliability was assessed from data collected by research staff on 52 row crop farms in Iowa. Cohen’s weighted Kappa values demonstrated high inter-rater reliability, ranging between 0.86 and 0.94, for all HAC sections. The HAC can be completed in 1.5-2 hours on each farm and requires about three hours of training, two hours of which are spent in field training. The ability to monitor injury-related hazards over time using an empirically driven tool will contribute significantly to injury prevention efforts in an industry with consistently high rates of fatal and nonfatal injury.

Keywords: Agriculture, audit, checklist, hazards, injury

It is well-established that agriculture is among the most dangerous industries in the U.S. (NIOSH, 2020). However, surveillance of agricultural injuries and their risk factors – a key strategy for prevention – is not systematically conducted and has been limited by methodological challenges (Patel et al., 2017). Primary data sources for agricultural injury surveillance have traditionally included the Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI), Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses (SOII), hospital discharge and emergency department data, and population surveys. However, these data sources likely capture only a fraction of the total injuries. For example, injuries on small farms are not reported in the SOII because this system only captures injury incidents occurring on farms with more than 10 employees, and hospital discharge and emergency department data are likely to capture only the more severe injury incidents.

National level surveillance of risk factors for agricultural injuries had been conducted in the US for several decades. Since 1990, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) partnered with the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) to administer national surveys of farm workers, including the Childhood Agricultural Injury Survey, Occupational Injury Surveillance of Production Agriculture, and injury modules of the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NIOSH, 2019; NIOSH, 2018a; NIOSH, 2018b). Although extremely valuable for monitoring risk factors, funding for these efforts is no longer available nationally, and surveillance using these sources ended by 2015. In 2015, the National Children’s Center for Rural and Agricultural Health and Safety developed AgInjuryNews to systematically collect and categorize news articles related to fatal and nonfatal agricultural injuries in the U.S. (Weichelt et al., 2018). While it is a current and public data source, it was not developed with the goal of surveillance but rather as a comprehensive source of farm incidents and safety messaging.

Regional surveillance of agricultural injury and injury-related risk factors has been done on farms through efforts such as the Certified Safe Farm (CSF) program (Rautiainen et al., 2004). As part of the farm certification process, trained personnel conduct on-site farm reviews to assess farm injury characteristics and risk factors contributing to injury (Donham et al., 2007; Rautiainen et al., 2010). The on-site review consists of 124 questions that take approximately two hours to complete for each farm. The safety review covers on-farm hazards, including equipment, livestock structures, storage and other structures, and the general outdoor working environment. The most commonly identified problems found on farms using the CSF program involved tractors, chemical storage, non-self-propelled machines, machine shop and repair area structures, swine and poultry structures, and grain storage structures (Jaspersen et al., 2004; Storm et al., 2018; CSF, 2016).

While CSF has been well-received by farmers (Kline et al., 2007; Storm et al., 2016; Schiller et al., 2010; Thu et al., 1998), sustainability as a community-based surveillance program has faced challenges. It has been difficult to recruit community organizations to conduct the on-farm safety reviews and move implementation of CSF from academic settings to the community (Schiller et al., 2010). Personnel who administer CSF assessments of farms require 20 hours of classroom and on-farm experiential learning (Rautiainen et al., 2010), which may be contributing to implementation barriers. Implementation barriers may also result from a lack of organizational resources, where for example, more established infrastructures (such as Extension Offices) have more resources to invest in implementation than community initiatives (Schiller et al., 2010; Storm et al., 2016). The literature suggests that CSF may be a useful starting model for identifying and reducing hazards on farms but for which adaptations are needed to create a sustainable community-based program.

Another program, called Farm/Agriculture/Rural Management- Hazard Analysis Tool (FARM-HAT), uses a gradated hazard scale to assess the safety of tractors, power take-off (PTO) machines, buildings and structures (e.g., farm shops, grain bins, manure storage), and emergency preparation. In a preliminary study of more than 200 farms in Pennsylvania, approximately two-thirds of farm operators did not have acceptable safety practices in place (Murphy et al., 1998; Legault and Murphy, 2000). FARM-HAT, now called Safer Farm, is available online through the National Farm Medicine Center. The reach of this online tool and its use as a surveillance system to collect farm hazard data is not known.

With the loss of NIOSH funding for national surveillance of farm injury and hazards, and because sustainable surveillance efforts are needed at the community level, it is critical to develop and evaluate surveillance strategies that can be easily implemented across multiple organizations that serve farmers. The purpose of this paper is to (1) describe a new tool to identify and characterize farm hazards that increase injury risk to farmers and farm workers, and (2) report the inter-rater reliability of the new tool when administered on row-crop farms in Iowa.

Materials and Methods

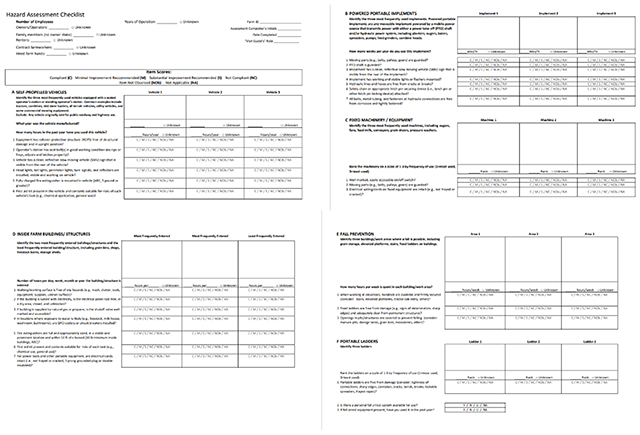

Development of a Hazard Assessment Checklist

The Hazard Assessment Checklist (HAC), a new tool for surveillance of agricultural injury risk factors, was developed by experts in the fields of occupational safety, industrial hygiene, occupational medicine, ergonomics, and injury epidemiology with representation from national trade associations, extension and outreach offices, researchers, and row crop farm owners and operators. The contents were reviewed iteratively by the experts until no further revisions of content or wording were made. Items included assessment of hazards known to increase the risk of acute farm injuries (Pickett et al., 2001; Swanton et al., 2016) as well as compliance with safety guidelines (e.g., American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers). The HAC was then pilot tested among operators of five row crop farms of varying sizes in Iowa, USA. Revisions from the pilot included: improving definitions of employee categories (e.g., distinguishing between contract workers and hired hands), improving definitions of the items to be scored, and modifying how duration of exposure to equipment and buildings was collected (e.g., hours per year for vehicles, times per day/week/month/year for buildings, frequency of use ranking for portable implements). The final version of the hazard assessment checklist is available in the Appendix.

Sections of the Hazard Assessment Checklist

Based on a literature review and a consensus of expert opinion, the checklist included hazards related to: self-propelled vehicles (e.g., tractors, combines), powered portable implements (e.g., planters, augers), fixed machinery and equipment (e.g., feed mills, conveyors), farm buildings and structures (e.g., grain bins, shops), fall risks (e.g., elevated platforms, grain storage), and portable equipment associated with fall risk. Within each of these sections, 3-7 individual items assessed compliance with recommended safety guidelines (e.g., American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers, Iowa Department of Transportation) or OSHA safety standards. Each section of the HAC allowed for three separate farm equipment/objects or spaces to be assessed (prioritizing those used most frequently). A description of what is included in each section, and the items assessed, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Items assessed for compliance in the Hazard Assessment Checklist

|

Description of Equipment and Spaces Assessed |

Characteristics Assessed for Compliance to Recommended Safety Guidelines or OSHA Standards |

|---|---|

|

Self-Propelled Vehicles Included vehicles equipped with a seated operator’s station or standing operator’s station, including tractors, combines, skid steer loaders, all terrain vehicles (ATVs), utility vehicles (UTVs), and some commercial mowing equipment. Excluded any vehicle originally sold for public roadway and highway use. |

• Rollover protective structure • Operator’s seatbelt • Slow moving vehicle (SMV) emblem • Lighting and marking • Fire extinguisher • First aid kit |

|

Powered Portable Implements Included any moveable implement powered by a mobile power source that transmits power with either a power take-off (PTO) shaft and/or hydraulic power system, including planters, augers, balers, spreaders, pumps, feed grinders, and combine heads. |

• Machine guarding • Power take-off (PTO) shaft • SMV emblem • Lighting and marking • Hydraulic line and hose • Safety chain and hitch pin • Bolts, metal tubing and fasteners |

|

Fixed Machinery and Equipment Included augers, fans, feed mills, conveyors, grain dryers, and pressure washers. |

• Emergency off switch • Machine guarding • Electrical wiring |

|

Inside Buildings and Structures Included the interior of buildings and structures used as part of the farming operation, including grain bins, shops, livestock barns, and storage sheds. Excluded residential buildings or other buildings not used as part of the farming operation. |

• Housekeeping and maintenance of walking/working surface • Electrical panel condition • Emergency gas shutoff valve • GFCI outlet/breaker • Fire extinguisher • First aid kit • Electrical cord on power tools |

|

Fall Prevention Included fixed but elevated working areas, including grain storage, elevated platforms, stairs, and fixed ladders on buildings. |

• Handrail • Fixed ladder • Opening on the floor |

|

Portable Ladders Included portable ladders and scissor lifts. Included availability of personal fall arrest system, and if so, if it had been used in the past year. |

• Damage to ladder • Availability of fall arrest equipment |

In addition to the sections assessed for compliance with recommended safety guidelines and OSHA standards, the following information was also included in the checklist:

Years of Operation, defined as the number of years the farm had been in operation at the time of the assessment.

Number of Employees, which included the number of current owners and operators, family members with no owner/operator stake in the farm operation, renters, contract farmers (defined as workers employed by a contracting agency or who are self-employed, including sprayers, crop dusters, fertilizers, veterinarians, shippers, etc.) and hired hands (excluding contract workers).

Inventory of Written Safety Policies, defined as any written signage on the farm or written policies available in physical or virtual form (see Table 2 for a list of policy topics).

Inventory of Safety Training, defined as formal training or certification provided to or received by all employees (see Table 2 for list of safety training topics).

Number of Work-Related Fatalities and Injuries by each category of employee (i.e., owner/operator, family member, renter, contract worker, hired hands) and included the following: (1) Number of work-related fatalities ever to occur on the farm, (2) number of injuries occurring on the farm in the past year that required hospitalization or surgery (not including those resulting in a fatality), (3) number of injuries occurring on the farm in the past 6 months that required attention from a primary care provider, urgent care provider or other healthcare provider (not including those that resulted in hospitalization or surgery or those resulting in a fatality), and (4) number of injuries in the past month that required first aid only.

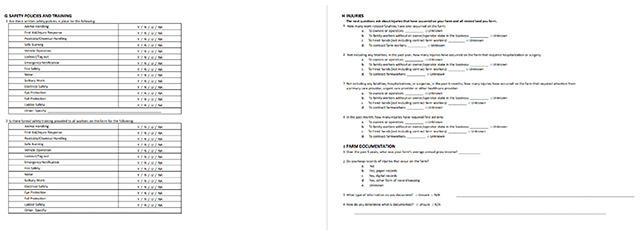

Table 2.

Written safety policies and safety training topics collected in the Hazard Assessment Checklist

| • Animal handling • First aid/Injury response • Pesticide/Chemical handling • Safe burning • Vehicle operation • Lockout/Tagout • Emergency notification • Fire safety |

• Noise • Solitary work • Electrical safety • Eye protection • Fall protection • Ladder safety • Other (with a description of the “other” topic(s)) |

Rating the HAC Items

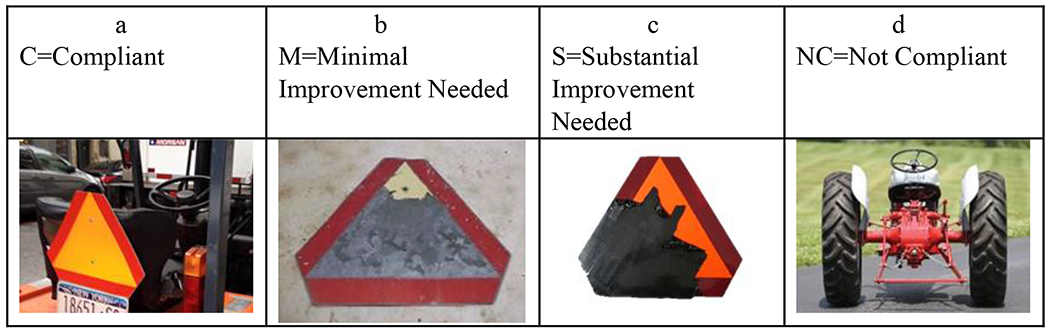

A scoring metric of three or four levels indicating the extent of compliance with recommended safety guidelines and standards promulgated by the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers (ASABE), Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and Iowa Department of Transportation (IDOT) was developed for each HAC item outlined in Table 1. Equipment and spaces were scored as compliant (“C”), minimal improvement needed (“M”), substantial improvement needed (“S”) and not compliant (“NC”). For example, for the self-propelled vehicle item, “Vehicle has a clean, reflective slow-moving vehicle (SMV) sign that is visible from the rear of the vehicle”, a score of “C” was assigned when the SMV sign was mounted correctly, easily visible, and had a solid red triangle border that was entirely retro-reflective with a non-reflective fluorescent center (Figure 1.a); a score of “M” was assigned if the SMV sign was mounted correctly and easily visible but its red triangle was dirty, beginning to fade or the fluorescent center was faded, ripped or missing (Figure 1.b); a score of “S” was assigned if the SMV sign was no longer reflective or broken or if the sign was not mounted correctly to allow for visibility from the rear (Figure 1.c); and a score of “NC” was assigned if an SMV sign was not present on the vehicle (Figure 1.d).

Figure 1.

Scoring of compliance to self-propelled vehicle item, “Vehicle has a clean, reflective SMV sign that is visible from the rear.”

In addition to the four levels of compliance, individual HAC items could be recorded as “Not Observed” if the equipment/space to which the item referred could not be observed at the time of the assessment (e.g., implement was in storage or in use at the time of the assessment) or “Not Applicable” (e.g., farm did not have three examples of each type of equipment/space at the time of the assessment, or recommended safety guidelines were not applicable to that piece of equipment/space).

Methods for Inter-Rater Reliability Assessment

Iowa row crop farm owners/operators whose farms were accessible within a two-hour drive of a midwestern university were eligible for enrollment in the study. Farmers were identified and recruited into the study through a variety of methods, including: (1) calls to subscribers of Farm Journal magazine, (2) in-person recruitment at the Iowa Corn Growers Safety Fair in Johnson County, events sponsored by the Midwest Old Settlers and Threshers Association, and Practical Farmers of Iowa field day events, and (3) advertising through social media and existing registries. All individuals were screened for eligibility by the Iowa Social Science Research Center (ISRC) and scheduled for a farm visit if eligible and interested in participating. The farm visit was completed by two research assistants (RAs) with farming expertise who were trained to identify hazards and rate them for compliance using the HAC scoring procedure and an accompanying field manual (available from the investigators by request). The field manual consisted of definitions, examples and pictures of each rating category (Compliant, Minimal Improvement, Substantial Improvement, Not Compliant) for each item on the checklist. The field manual was used to ensure consistent application of rating criteria across the researchers and was kept with the RAs at all times during the farm visits.

Before field training to collect HAC data, the RAs reviewed the HAC questions and field manual with a senior study team researcher to ensure that the intent of the questions was understood and that definitions used in the rating system were clear. During the field training, the senior researcher trained the RAs on how to score HAC items by discussing the scoring in real-time. During this training period, only the senior researcher’s scores were coded, and they were not analyzed for agreement. Once the RAs were comfortable with the scoring system, the research pair completed several more visits where separate scoring occurred, followed immediately by a discussion of why items were assigned particular scores. Only when the RAs scores and rationale for the scores were consistent with the field manual, did they attend farm visits and complete the HAC independently.

Upon arrival at the farm after farm owner/operator enrollment, the researchers introduced themselves, re-explained the purpose of the study and collected farm information (e.g., number of employees, years in operation). Next, the farm owner/operator or designee led the researchers on a tour of the farm. During this time, the researchers communicated with the owner/operator and each other about which hazards on the farm they had selected to rate but did not share their ratings with each other. Individual HAC items were assessed and rated independently so that inter-rater reliability could be accurately evaluated. For each section of the HAC, the researchers asked to be shown the most commonly used equipment/object or space and rated that object or space using the C/M/S/NC scale described above. The farm visits typically required 60 to 90 minutes depending on the size and layout of the farm. At the end of the visit, the farm owner/operator or designee was thanked for their time and compensated $50 cash. HAC data were collected between June 2019 and March 2020.

Data were collected on hard-copy forms while on the farm and then entered into REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) (Harris et al., 2009; Harris et al., 2019) after the farm visit. For data entry quality control, each hazard assessment checklist was entered twice by two researchers and checked for discrepancies. The study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Boards of the universities from which the authors are employed.

Inter-rater reliability (IRR) was assessed between the two raters for 52 farms using weighted Kappa statistics for ordinal outcomes (i.e., C, S, M, NC). If an item on the HAC was not observed (NOB) or not applicable (NA) on a farm, then that item was not included in the inter-rater reliability assessment. The weighted Kappa statistic (Cohen, 1968) is a measure of agreement for ordinal categorical ratings assigned by two raters that is corrected for agreement due to random chance. An IRR score of at least 0.80 is defined as having strong inter-rater agreement (McHugh, 2012). For each item of the HAC, point estimates and 95% confidence limits were calculated for weighted Kappa, based on Cicchetti-Allison agreement weights (Cicchetti and Allison, 1971). Averages of weighted Kappa were subsequently calculated for each section of the HAC. All analyses were completed using SAS, version 9.4, with weighted Kappa statistics obtained via the FREQ procedure.

Results and Discussion

The estimated weighted Kappas demonstrated high inter-rater reliability (IRR) for all sections (Table 3) and items (Table 4) of the HAC. Average weighted Kappa values for the six HAC sections ranged between 0.86 (indicating a strong level of agreement) and 0.94 (indicating almost perfect agreement). The sections with the highest IRR were for self-propelled vehicles (average weighted Kappa=0.94) and powered-portable implements (average weighted Kappa=0.93). The sections with the lowest IRR were for ladders (average weighted Kappa=0.86) and fall areas (average weighted Kappa=0.89).

Table 3.

Inter-rater reliability by section of the Hazard Assessment Checklist, 52 farms assessed.

|

HAC Section |

Total items in section | Average of weighted Kappa values | Range of weighted Kappa values |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Self-Propelled Vehicles | 6 | 0.94 | 0.84-0.98 |

| B. Powered-Portable Implements | 7 | 0.93 | 0.87-1.0 |

| C. Fixed Machinery / Equipment | 3 | 0.91 | 0.87-0.94 |

| D. Inside Buildings / Structures | 7 | 0.92 | 0.81-0.97 |

| E. Fall Areas | 3 | 0.89 | 0.81-0.94 |

| F. Portable Ladders | 1 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

Table 4.

Inter-rater reliability weighted Kappa statistics by HAC item, 52 farms assessed.

|

HAC Item |

N* |

Weighted Kappa (95% CL) |

|---|---|---|

|

A. Self-Propelled Vehicles | ||

| Equipment has rollover protective structure (ROPS) free of structural damage and in upright position? | 155 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.0) |

| Operator′s station has seat belt(s) in good working condition (i.e., no rips or frays, adjusts and latches properly)? | 153 | 0.94 (0.89, 1.0) |

| Vehicle has a clean, reflective slow-moving vehicle (SMV) sign that is visible from the rear of the vehicle? | 149 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.0) |

| Head lights, tail lights, perimeter lights, turn signals, and reflectors are installed, visible and working on vehicle? | 153 | 0.84 (0.73, 0.96) |

| Fully charged fire extinguisher is mounted in vehicle (ABC, 5 pound or greater)? | 155 | 0.97 (0.91, 1.0) |

| First aid kit is present in the vehicle and contents suitable for risks of each vehicle′s task (e.g., chemical application, general use)? | 153 | ** |

|

B. Powered Portable Implements | ||

| Moving parts (e.g., belts, pulleys, gears) are guarded? | 136 | 0.89 (0.82, 0.96) |

| PTO shaft is guarded? | 117 | 0.90 (0.84, 0.96) |

| Implement has a clean, reflective slow-moving vehicle (SMV) sign that is visible from the rear of the implement? | 129 | 0.97 (0.93, 1.0) |

| Implement has working and visible lights or flashers mounted? | 129 | 0.87 (0.80, 0.95) |

| Hydraulic lines and hoses are free from cracks or breaks? | 89 | 1.00 *** |

| Safety chain or appropriate hitch pin securing device (i.e., lynch pin or other hitch pin locking device) attached? | 79 | 1.00 (1.0, 1.0) |

| All bolts, metal tubing, and fasteners at hydraulic connections are free from corrosion and tightly fastened? | 89 | 0.93 (0.81, 1.0) |

|

C. Fixed Machinery | ||

| Well marked, easily accessible on/off switch? | 136 | 0.94 (0.89, 1.0) |

| Moving parts (e.g., belts, pulleys, gears) are guarded? | 136 | 0.92 (0.87, 0.97) |

| Electrical wiring/cords on fixed equipment are intact (e.g., not frayed or cracked)? | 135 | 0.87 (0.75, 0.99) |

|

D. Inside Buildings and Structures | ||

| Walking/working surface is free of trip hazards (e.g., trash, clutter, tools, equipment supplies, unlevel surface)? | 145 | 0.81 (0.72, 0.89) |

| If building is supplied with electricity, is the electrical panel rust-free, in a dry area, closed, and unblocked? | 128 | 0.92 (0.87, 0.98) |

| If building is supplied by natural gas or propane, is the shutoff valve well marked and accessible? | 40 | 0.87 (0.76, 0.98) |

| In locations where exposure to water is likely (e.g., livestock, milk house, washroom, bathrooms), are GFCI outlets or circuit breakers installed? | 43 | 0.96 (0.91, 1.0) |

| Fire extinguishers are full and appropriately sized, in a visible and prominent location and within 50 ft of a hazard? (10 lbs. minimum inside buildings, ABC) | 143 | 0.97 (0.94, 1.0) |

| First aid kit is present and contents suitable for risks of each task (e.g., chemical use, general use)? | 139 | 0.97 (0.90, 1.0) |

| For power tools and other portable equipment, are electrical cords intact (i.e., not frayed or cracked, 3 prong grounded plug or double insulated)? | 72 | 0.91 (0.79, 1.0) |

|

E. Fall Areas | ||

| When working at elevations, handrails are available and firmly secured (consider: stairs, elevated platforms, tractor cab entry, other)? | 100 | 0.94 (0.90, 0.99) |

| Fixed ladders are free from damage (e.g., signs of deterioration, sharp edges) and adequately clear from permanent structures? | 90 | 0.81 (0.58, 1.0) |

| Openings in pits/structures are covered to prevent falling (consider: manure pits, storage tanks, grain bins, mezzanines, other)? | 80 | 0.94 (0.81, 1.0) |

|

F. Ladders | ||

| Portable ladders are free from damage (consider: tightness of connections, sharp edges, corrosion, cracks, bends, breaks, lockable spreaders, frayed ropes)? | 126 | 0.86 (0.75, 0.97) |

: The number of responses used to calculate weighted Kappa values varied as a function of the number of pieces of equipment or farm spaces available for inspection and assessment (from a minimum of one to a maximum of three).

: Weighted Kappa statistic could not be calculated due to the perfect homogeneity of the data (i.e., all 153 scores from both raters were scored as non-compliant because none of the vehicles assessed had a first aid kit).

: Confidence interval could not be calculated due to data having perfect agreement.

The weighted Kappa values for individual items on the HAC ranged between 0.81 and 1.00 (Table 4). Items scoring hydraulic lines and hoses and safety chain or hitch pins for powered portable implements had perfect agreement between raters. The individual items with the lowest IRR were walking/working surfaces in buildings were free of trip hazards (weighted Kappa=0.81; 95% CL: (0.72, 0.89)) and fixed ladders were free from damage and adequately clear from permanent structures (weighted Kappa=0.81; 95% CL: (0.58, 1.0)). Across all items of the HAC (n=27), two-thirds had weighted Kappa values indicating almost perfect agreement (i.e., between 0.90 and 1.00).

All sections and items of the Hazard Assessment Checklist (HAC) had very high inter-rater reliability. This was likely due to the use of a detailed standard field manual, the extensive training research assistants received, and the expertise of the research assistants (RAs) in agricultural safety. The HAC developed in this study can be completed in one to one and a half hours and requires about three hours of training, two hours of which are spent in field training. While it also requires a user with some knowledge of farming practices and agricultural safety, the HAC is simple and straightforward to complete and requires minimal training time. It also has excellent inter-rater reliability, whereas other tools have shown mixed scores across raters (Murphy et al., 1998; Legault and Murphy, 2000; Rautiainen et al., 2010).

Of the six sections of the HAC, the assessment of self-propelled vehicles and powered portable implements had the best agreement between raters. They both also included a high number of items (6 and 7 items, respectively), increasing the precision of the averaged estimates. All individual items scored in the self-propelled vehicles section had an average weighted Kappa > 0.90 with the exception of headlights, perimeter lights, turn signals, and reflectors are installed, visible and working on vehicles? (weighted Kappa=0.84). Upon further investigation of this item, we found that older vehicles with headlights or taillights but no turn signals were recorded as compliant by one research assistant (because they had taken the lighting and marking requirement at the time of manufacture of the older vehicle into consideration) and minimal improvement recommended by the other research assistant (in comparison to current requirements), therefore contributing to the lower agreement. The field manual has been clarified to prevent heterogeneity of self-propelled vehicles and powered portable implement lighting and marking scoring.

The high agreement for the powered portable implements category was likely influenced by the two questions about hydraulics, which had perfect agreement. These questions were: hydraulic lines and hoses are free from cracks or breaks? and safety chain or appropriate hitch pin securing device (i.e., lynch pin or other hitch pin locking device) attached? Agreement between researchers was likely high for these items because there was little or no personal judgment necessary to assign the compliance categories of these items. The inclusion in the field manual of several pictures that clearly distinguished between the categories on the scale likely also contributed to the high level of observed agreement.

One of the individual items with the lowest agreement assessed the degree to which walking and working surfaces were free from trip hazards. There was substantial variation in the type of floors that were present across farm buildings, for example dirt floors in barns, gravel floors in machine sheds, and cement floors in workshops. Therefore, what may have been considered safe for one flooring type (e.g., the presence of straw on a barn floor reduces slipperiness from mud) may have been hazardous for another (e.g., the presence of straw on a cement floor makes it more slippery). This example suggests that the field manual needs to be revised with examples and definitions for various flooring types.

The Hazard Assessment Checklist was designed initially to be administered by agricultural safety research staff but has the potential to be translated to multiple users, including insurance company representatives, extension office staff and farmers. To our knowledge, a common tool for assessing injury hazards is not consistently used across organizations that serve farmers. Based on the literature, there have been barriers to translating injury surveillance efforts from the academic research setting to community-led settings where they are more likely to be sustained long-term (Schiller et al., 2010). However, audit tools exist, including Farm/Agriculture/Rural Management- Hazard Analysis Tool (FARM-HAT). FARM-HAT was developed and tested in the late 1990s and was the first to measure the degree of protection against various farm hazards (Murphy et al., 1998; Legault and Murphy, 2000). Previously, farm hazards had been dichotomously rated as ‘safe or unsafe’ or ‘satisfactory or not satisfactory’, which limits how hazards are described and how they can be corrected. Similar to FARM-HAT, now SaferFarm, the Hazard Assessment Checklist uses a gradation of compliance to industry and regulatory standards to assess injury-related farm hazards.

This study has several limitations. The first concerns the way in which data was collected to perform the inter-rater reliability assessment. Two researchers went to the farm visit together, as it was determined to be too burdensome on the farm owner/operator to schedule two separate farm visits. Therefore, researchers needed to be compliant with instructions to complete the HAC independently while at the same visit. Another limitation was that the HAC only focused on hazards associated with row crop farms (i.e., there were no assessments of animal-related hazards). This was intentional due to the limited number of dairy, beef, and chicken farms within feasible travel distance from the midwestern university and concerns about recruiting a sufficient number of animal and poultry farms to meet sample size requirements. While pork farms are prevalent in Iowa, there was an outbreak of African swine fever during the study period which likely would have negatively influenced recruitment. We also incentivized farmers $50 cash for the time they participated in HAC data collection, which is likely not a sustainable or realistic implementation strategy outside of a research study. Finally, the study excluded chemical hazards in the assessment. This was also intentional because most acute traumatic injuries from chemicals on farms are task-specific which we were unlikely to observe during a farm visit.

Conclusions

Future directions for the HAC include its digitization into a mobile app format for faster data entry and dissemination efforts, expanding the tool beyond row crop operations, and developing the tool for multiple users with a goal of sustainability. Future research should focus on developing and evaluating dissemination protocols to maximize use of the Hazard Assessment Checklist in organizations that serve, regulate or market products or services to farms. Ultimately, we believe that the ability to monitor injury-related hazards over time using an empirically driven tool will contribute significantly to injury prevention efforts in an industry with consistently high rates of fatal and nonfatal injury.

Highlights.

Sustainable tools for conducting surveillance of farm injury and injury-related hazards in the U.S. is needed.

A new tool for the surveillance of injury hazards on row crop farms has excellent inter-rater reliability.

The new tool is simple and straightforward to complete and requires minimal training time.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Rebekah Estes and Virgil Jackson for their agricultural injury expertise and skills in data collection. This work was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Grant numbers: U54 OH 007548, T42 OH 008491). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

APPENDIX

References

- Cicchetti DV, Allison T (1971). A new procedure for assessing reliability of scoring EEG sleep recordings. Am. J. EEG Technology, 11(3), 101–110. DOI: 10.1080/00029238.1971.11080840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1968). Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol. Bull, 70(4), 213–20. DOI: 10.1037/h0026256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CSF (Certified Safe Farm) Manual. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.unmc.edu/publichealth/cscash/_documents/CSFManual-81216i.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Donham KJ, Rautiainen RH, Lange JL, Schneiders S (2007). Injury and illness costs in the Certified Safe Farm Study. J. Rural. Health, 23(4), 348–55. DOI: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2007.00103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform, 42(2), 377–81. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, … REDCap Consortium. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. J. Biomed. Inform 95, 103208. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspersen J, Von Essen S, List P, Howard L, Morgan D (1999). The Certified Safe Farm Project in Nebraska: The first year. Biological Systems Engineering: Papers and Publications. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Kline A, Leedom-Larson K, Donham KJ, Rautiainen R, Schneiders S (2008). Farmer assessment of the Certified Safe Farm program. J. Agromedicine. 12(3), 33–43. DOI: 10.1080/10599240801887827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legault ML, Murphy DJ (2000). Evaluation of the Agricultural Safety and Health Best Management Practices Manual. J. Agric. Saf. Health. 6(2), 141–153. DOI: 10.13031/2013.3026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh ML Interrater reliability: The Kappa statistic. (2012). Biochem. Med. (Zagreb). 22(3), 276–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DJ, Kiernan NE, Hard DL, Landsittel D (1998). The Pennsylvania Central Region Farm Safety Pilot Project: Part 1- rationale and baseline results. J. Agric. Saf. Health. 4(1), 25–41. DOI: 10.13031/2013.15346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH. (2019). National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/aginjury/naws/default.html [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH. (2018a). Childhood Agricultural Injury Survey (CAIS). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/childag/cais/default.html#:~:text=Childhood%20Agricultural%20Injury%20Survey%20%28CAIS%29%20Results%20Youth%20who,at%20high%20risk%20for%20non-fatal%20and%20fatal%20injuries [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH. (2018b). Occupational Injury Surveillance of Production Agriculture (OISPA). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/aginjury/oispa/default.html [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH. (2020). Agricultural Safety. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/aginjury/default.html [Google Scholar]

- Patel K, Watanabe-Galloway S, Gofin R, Haynatzki G, Rautiainen R (2017). Non-fatal agricultural injury surveillance in the United States: A review of national-level survey-based systems. Am. J. Ind. Med. 60(7), 599–620. DOI: 10.1002/ajim.22720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett W, Hartling L, Dimich-Ward H, Guernsey JR, Hagel L, Voaklander DC, Brison RJ (2001). Surveillance of hospitalized farm injuries in Canada. Inj. Prev. 7(2), 123–128. DOI: 10.1136/ip.7.2.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautiainen RH, Grafft LJ, Kline AK, Madsen MD, Lange JL, Donham KJ (2010). Certified Safe Farm: Identifying and removing hazards on farms. J. Agric. Saf. Health. 16(2), 75–86. DOI: 10.13031/2013.29592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautiainen RH, Lange JL, Hodne CJ, Schneiders S, Donham KJ (2004). Injuries in the Iowa Certified Safe Farm Study. J. Agric. Saf. Health. 10(1), 51–63. DOI: 10.13031/2013.15674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller LF, Donham K, Anderson T, Dingledein DM, Strebel RR (2010). Incorporating occupational health interventions in a community-based participatory preventive health program for farm families: A qualitative study. J. Agromedicine. 15(2), 117–26. DOI: 10.1080/10599241003622491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm JF, LePrevost CE, Arellano C, Cope WG (2018). Certified Safe Farm implementation in North Carolina: Hazards, safety improvements, and economic incentives. J. Agromedicine. 23(4), 381–92. DOI: 10.1080/1059924X.2018.1508395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm JF, LePrevost CE, Tutor-Marcom R, Cope WG (2016). Adapting Certified Safe Farm to North Carolina agriculture: An implementation study. J. Agromedicine. 21(3), 269–83. DOI: 10.1080/1059924X.2016.1180273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanton AR, Young TL, Peek-Asa C (2016). Characteristics of fatal agricultural injuries by production type. J. Agric. Saf. Health. 22(1), 75–85. DOI: 10.13031/jash.22.11244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thu KM, Pies B, Roy N, Von Essen S, Donham K (1998). A qualitative assessment of farmer responses to the Certified Safe Farm concept in Iowa and Nebraska. J. Agric. Saf. Health. 4(3):161–71. DOI: 10.13031/2013.15354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weichelt B, Salzwedel M, Heiberger S, Lee BC (2018). Establishing a publicly available national database of US news articles reporting agriculture-related injuries and fatalities. Am. J. Ind. Med. 61:667–674. DOI: 10.1002/ajim.22860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]