From the Authors:

We sincerely thank Wang and coworkers for their thoughtful comments on our study (1). These are greatly valued, as they help in refining our understanding of this complex topic.

We acknowledge the discrepancy identified concerning the pendelluft calculation. The pixel-per-pixel Tidal impedance variation (TidalΔZ) is indeed, by definition, always larger than the breath-cycle TidalΔZ, as evidenced when comparing the values for TidalΔZ in Table 2 and Table E1 in our study (1). The confusion arose as a result of a labeling error in Figure E7 in the online supplement (1), in which the x- and y-axes were inadvertently swapped. We are grateful to Wang and colleagues for spotting this oversight, allowing us to rectify the error promptly. A corrected version of the figure has been inserted in the online supplement (1); the Journal is also publishing an erratum to notify its readership of the change.

In their letter, Wang and colleagues provide several interesting physiological and methodological observations, sparking an engaging discussion on the complex physiology of transpulmonary pressure distribution and the limitations of electrical impedance tomography. It is indeed true that the propagation of transpulmonary pressure in the lungs is not homogeneous, with regional inhomogeneities potentially amplifying transpulmonary pressure in nearby areas. This theory, proposed more than 50 years ago, has been substantiated by Cressoni and coworkers using computed tomography scans, showcasing certain regions acting as “stress raisers” for the surrounding areas (2, 3). This might be particularly prominent during spontaneous breathing, in which the intense inspiratory effort coupled with local inhomogeneities may result in increased force delivery to the dorsobasal regions of the lungs (4).

In this sense, because positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) improves the aeration of dorsal areas and reduces the magnitude of pendelluft (5), it may also decrease the inflation inhomogeneities. This may explain why, in our study, the magnitude of pendelluft was lower with helmet continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and noninvasive ventilation (NIV) (1). Our study was the first to address pendelluft magnitude in nonintubated patients with acute respiratory failure. Unfortunately, it is complicated to otherwise assess the regional heterogeneity of transpulmonary pressure during spontaneous breathing.

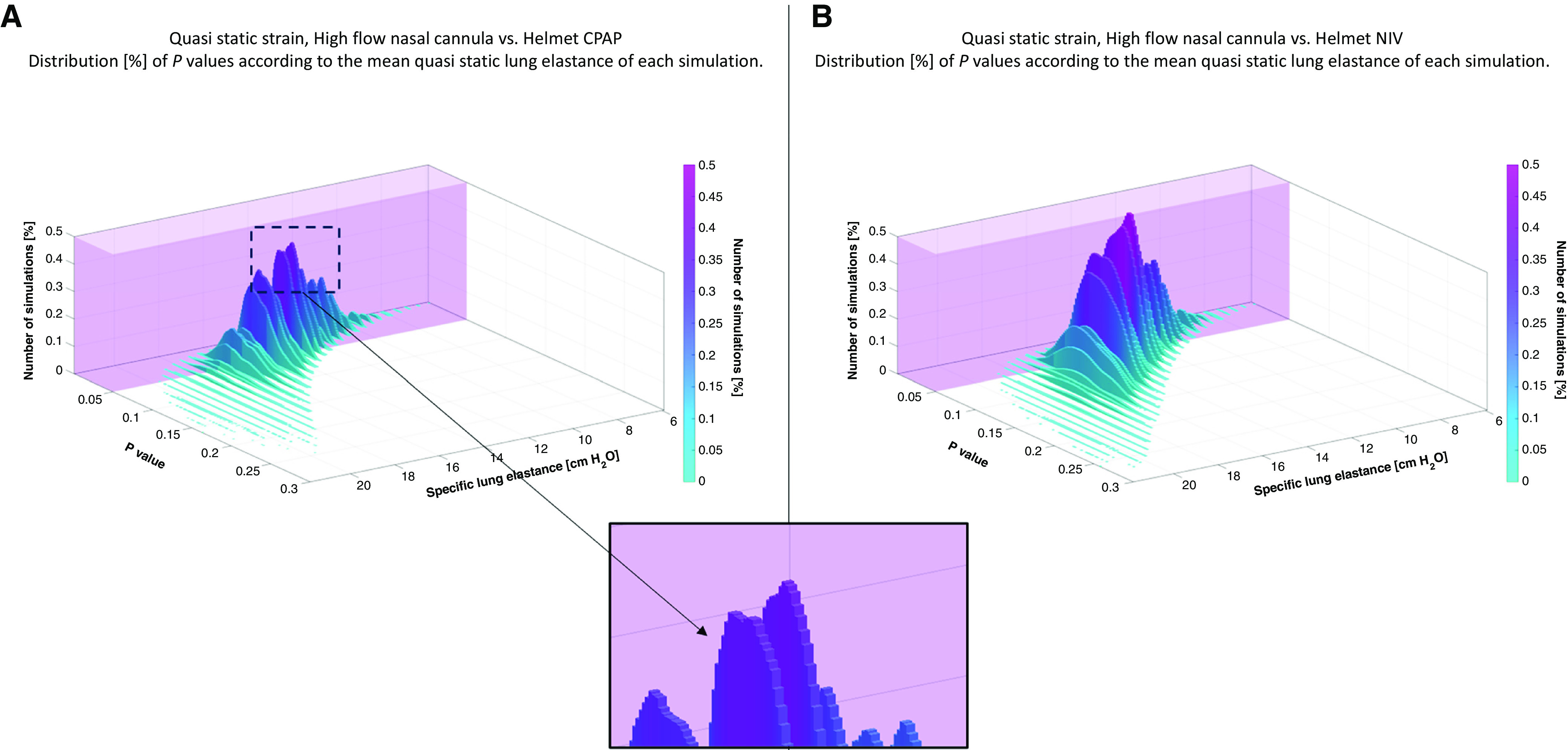

Wang and coworkers question the approach to dynamic strain assessment proposed in our study, which is based on the constant relationship between stress and strain based on specific lung elastance. They correctly address the variability of specific lung elastance, which represents the transpulmonary pressure required to inflate the lung with a tidal volume equal to the functional residual capacity. They correctly point out that it can vary not only with the application of PEEP, but also as a dependency of relatively high inflated volumes (6). The assessment of dynamic strain is crucial to rate the risk of ventilator-induced lung injury, which is a concern when noninvasive respiratory support is applied in patients with hypoxemia. We definitely share these concerns; however, we are not aware of any other technique to assess dynamic strain in nonintubated patients. Although our computation is an approximation based on specific assumptions, we did our best to provide results based on a reasonable approach. To address the concerns of Wang and colleagues, we performed an in silico simulation, assuming the specific lung elastance for our 15 patients to be 10.4 cm H2O, 13.7 cm H2O, or 16.99 cm H2O (mean and 95% confidence intervals of a previous cohort of patients with acute respiratory failure) (7). By generating all possible combinations of elastance values across our patient set, we explored the potential interplay between the assumed elastance values and the study results. Our bootstrap produced a total of 315 (14,348,907) different possible dynamic strain values (in the high-flow nasal oxygen [HFNO] phase) for our cohort of patients. We then compared dynamic strain in the three study phases using our prior calculations for each of these cohorts (1). The decrease in dynamic strain with helmet CPAP compared with HFNO was statistically significant in 82% of simulations, and the difference between helmet NIV and HFNO persisted in 53% of cases (Figure 1). No significant difference was detected between NIV and CPAP for any of the cohorts. We think this simulation indicates the substantial likelihood of the results we described in our study.

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional histogram representing the results of the in silico simulation. The x- and y-axes represent the mean specific lung elastance (k) of a single simulation and the associated P value, and the color intensity on the z-axis (vertical axis) represents the frequency of occurrences (%). The mean k values were calculated by averaging the different lung elastances from every random combination of the three selected k values and the 15 patients as described in the letter. As highlighted in the magnified inset, per every mean k, there is a Gaussian-like distribution of the histograms, and every single histogram reflects the behavior of that percentage of simulations with a specific k and the associated P value. The transparent purple cuboids superimposed on the three-dimensional histograms highlight the regions where the simulations resulted in a P value ⩽ 0.05.

Despite the inherent limitations of all these approximations, we believe the overall clinical meaning of our study remains clear and is sound: we observed a potential reduction in dynamic lung strain (confirmed by the additional analysis detailed here) with CPAP and NIV, and we report a different effect of PEEP and pressure support on inspiratory effort, aeration in dorsal areas, and the extent of pendelluft.

We extend our sincere gratitude to the authors for their thoughtful commentary. It underscores the challenges of conducting physiological research in awake and nonintubated patients, and emphasizes the importance of new techniques for advanced physiological measurements and, possibly, for personalization of care based on physiological phenotypes.

Footnotes

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202307-1173LE on August 16, 2023

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Menga LS, Delle Cese L, Rosà T, Cesarano M, Scarascia R, Michi T, et al. Respective effects of helmet pressure support, continuous positive airway pressure, and nasal high-flow in hypoxemic respiratory failure: a randomized crossover clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2023;207:1310–1323. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202204-0629OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mead J, Takishima T, Leith D. Stress distribution in lungs: a model of pulmonary elasticity. J Appl Physiol . 1970;28:596–608. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1970.28.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cressoni M, Cadringher P, Chiurazzi C, Amini M, Gallazzi E, Marino A, et al. Lung inhomogeneity in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2014;189:149–158. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1567OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yoshida T, Torsani V, Gomes S, De Santis RR, Beraldo MA, Costa ELVV, et al. Spontaneous effort causes occult pendelluft during mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2013;188:1420–1427. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201303-0539OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morais CCA, Koyama Y, Yoshida T, Plens GM, Gomes S, Lima CAS, et al. High positive end-expiratory pressure renders spontaneous effort noninjurious. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2018;197:1285–1296. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1244OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mingote Á, Marrero García R, Santos González M, Castejón R, Salas Antón C, Vargas Nuñez JA, et al. Individualizing mechanical ventilation: titration of driving pressure to pulmonary elastance through Young’s modulus in an acute respiratory distress syndrome animal model. Crit Care . 2022;26:316. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-04184-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chiumello D, Carlesso E, Cadringher P, Caironi P, Valenza F, Polli F, et al. Lung stress and strain during mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2008;178:346–355. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200710-1589OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]