Abstract

Cerebral vasogenic edema, a severe complication of ischemic stroke, aggravates neurological deficits. However, therapeutics to reduce cerebral edema still represent a significant unmet medical need. Brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs), vital for maintaining the blood-brain barrier (BBB), represent the first defense barrier for vasogenic edema. Here, we analyzed the proteomic profiles of the cultured mouse BMECs during oxygen-glucose deprivation and reperfusion (OGD/R). Besides the extensively altered cytoskeletal proteins, ephrin type-A receptor 4 (EphA4) expressions and its activated phosphorylated form p-EphA4 were significantly increased. Blocking EphA4 using EphA4-Fc, a specific and well-tolerated inhibitor shown in our ongoing human phase I trial, effectively reduced OGD/R-induced BMECs contraction and tight junction damage. EphA4-Fc did not protect OGD/R-induced neuronal and astrocytic death. However, administration of EphA4-Fc, before or after the onset of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO), reduced brain edema by about 50%, leading to improved neurological function recovery. The BBB permeability test also confirmed that cerebral BBB integrity was well maintained in tMCAO brains treated with EphA4-Fc. Therefore, EphA4 was critical in signaling BMECs-mediated BBB breakdown and vasogenic edema during cerebral ischemia. EphA4-Fc is promising for the treatment of clinical post-stroke edema.

Keywords: Blood-brain barrier, EphA4, stress fibers, stroke, vasogenic edema

Introduction

Ischemic stroke is a major cause of adult disability and death worldwide. 1 The disruption of blood flow blocks oxygen and nutrients that support the infarct area, resulting in neuronal damage. The pathogenic cascading events include brain edema, blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption, oxidative stress, and inflammatory response. 2 Neuroprotective drugs, such as edaravone and cerebrolysin, have been developed to decrease oxidative stress and enhance neurotrophic effects in stroke brains. 3 However, effective and specific drugs to treat cerebral vasogenic edema after a stroke are still unavailable.

Cerebral vasogenic edema is an acute and severe complication during a stroke. If not immediately treated, cerebral edema causes extensive brain damage and death. 4 The pathogenesis of brain edema starts from the early onset of cytotoxic edema developed minutes after a stroke to the severe vasogenic edema that occurs about 6 h after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. 5 So far, the essential clinical management practice of brain edema is nontargeted interventions, such as hyperosmolar agents, sedation, and decompressive craniectomy.6,7 Developing specific and targeted pharmacological drugs to alleviate vasogenic edema is urgently needed in emergency rooms to protect the stroke brain. However, finding crucial molecular targets and developing specific targeting drugs to treat brain edema has been challenging. 8

The complexity of cellular structures and molecules involved in maintaining the BBB integrity underlines the challenges of finding crucial molecular targets for cerebral edema. The first barrier limiting water entrance from the blood into the brain parenchyma is the BBB. Disruption of BBB integrity is the primary cause of vasogenic edema in stroke. 9 BBB consists of brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) sealed by tight junctions, the basement membrane of the blood vessel endothelial cells, pericytes, and the astrocytic end feet. The expression patterns of tight junction proteins on BMECs also reflect the integrity of the BBB. 10 We have shown previously that the loss of tight junction proteins occurs during the early reperfusion phase of cerebral ischemia.11,12 Additionally, the expression of vascular endothelial growth factors receptors, matrix metalloproteinases, aquaporins, Na+–K+–Cl−–co-transporter 1, sulfonylurea receptor 1-regulated nonselective cation channels, endothelin receptor, and glucocorticoid receptor are all considered to be part of the edema responses during the early stage of cerebral ischemia.6,13,14 Collectively, the current literature emphasizes the critical role of BMECs as the first defense barrier in post-stroke vasogenic edema.

To better understand the molecular complexity of BMECs in brain edema after cerebral ischemia, we performed proteomic analysis on cultured BMECs subjected to OGD/R. Using this approach, we discovered the elevated expression of ephrin type-A receptor 4 (EphA4), which has been reported to modulate the severity of brain damage during cerebral ischemia.15 –17 We developed a specific blocker, EphA4-Fc, to demonstrate the reduced damage to the in vitro cultured BMECs. To our surprise, blocking EphA4 significantly reduced cerebral vasogenic edema in vivo in the ischemic mouse brain. This experimental evidence supports the potential role of EphA4 as a molecular target for modulating vasogenic edema in the post-stroke brain.

Methods

Chemicals

Collagenase II was purchased from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Lakewood, NJ, USA). Evans blue, sodium fluorescein, 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC), DNAse I, bovine serum albumin (BSA), Percoll, poly-D-Lysine, collagen type IV, fibronectin, heparin, were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Collagenase/dispase was purchased from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, high glucose), glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, glucose-free DMEM, RIPA buffer, cocktail, chemical luminescence, Neurobasal medium, B27, and BCA kit were obtained from Thermo Scientific (USA). CCK-8 kit, puromycin, and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) were purchased from MedChemExpress (China).

Primary cell culture

According to the previously published methods, cortical neurons were isolated from the mice at embryonic day 19 (E19). 18 Briefly, the collected cortex was cut into small pieces and digested in DMEM with papain (0.1 mg/ml) and DNAse (10 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37 °C. The dissociated neuronal cells at the concentration of 4 × 105 cells/ml were seeded in the poly-D-Lysine (0.1 mg/ml) coated 96-well plate or glass coverslips in a 24-well plate and cultured in Neurobasal medium containing B27 supplement and 0.5 mM glutamine. After culturing for 7 d, neurons were used for experiments.

Brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) were isolated from mice as previously described. 11 After removing the meninges by rolling the brains on a sterile blotting paper, cortices and striatum from ten mice (20–25 g of body weight) were cut into small pieces in ice-cold DMEM medium and mixed with collagenase II (1 mg/ml) and DNAse (10 μg/ml) for digestion (1 h, 37 °C) in a shaker at 180 rpm. The tissue suspension was centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the residues were suspended with 30 ml of BSA-DMEM (20% w/v) and centrifuged at 1000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. The residues were further digested with collagenase/dispase (1 mg/ml) and DNAse (10 μg/ml) in DMEM for 1 h at 37 °C. After centrifugation at 1000 g for 5 min at 4 °C, the residues were transferred on the surface of a 33% continuous Percoll solution, including 19 ml PBS (1x), 1 ml PBS (10x), 1 ml FBS and 10 ml Percoll. BMEC clusters were separated on Percoll gradient (1000 g, 10 min, 4 °C) and seeded on collagen type IV (0.16 mg/ml) and fibronectin (10 μg/ml)-coated multiwell plates. The culture medium included DMEM, 20% FBS, 5 ng/mL bFGF, 100 μg/ml heparin, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. The cells were exposed to puromycin (4 μg/ml) for the first 2 d and used for the experiment when reaching confluency.

Astrocytes were isolated from the cortex of perinatal (P1 to P4) mouse pups. 19 The collected cortex without the meninges was digested with 2.5% trypsin for 30 min at 37 °C and then centrifuged for 5 min at 300 g to obtain the cell pellet. Cells at the concentration of 1 × 107 cells/ml were seeded in the poly-D-Lysine (0.1 mg/ml) coated T75 tissue culture flask and cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. When reaching the confluency, shaking the T75 flask at 180 rpm for 30 min was to remove microglia, and continuous shaking the flask at 240 rpm for 6 h was to remove oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Then the enriched astrocytes could be used for further experiments.

Oxygen-glucose deprivation and reperfusion (OGD/R)

Cells were washed with PBS three times and incubated with nitrogen-bubbled glucose-free DMEM, which were transferred to the airtight chamber (Billups-Rothenberg, USA) with an oxygen detector (Nuvair, USA). The hypoxic environment with the oxygen concentration (< 0.5%) was achieved by injecting 95% N2 and 5% CO2 for 20 min and maintaining for 4 h at 37 °C. The control cells were incubated with DMEM without FBS for 4 h at 37 °C in 95% air and 5% CO2. After oxygen-glucose deprivation, the cells were given the fresh culture medium (OGD/R).

Label-free quantitative proteomics of BMECs after OGD/R treatment

In OGD/R-treated or control group, three samples of BMECs in each group were collected for proteomic assay. BMECs, exposed to 4 h OGD and 2 h reperfusion, were collected in ice-cold lysis buffer (0.2% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM Na3VO4, protease inhibitor, phosphatase inhibitor, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6). Cells were vortexed and incubated on ice for 30 min, and cell lysates were centrifuged for 15 min at 11000 g at 4 °C using a centrifuge (JXN30, Beckman, USA). The supernatant was collected for protein concentration measurement. Then the supernatant was added with 4x volumes of ice-cold methanol and vortex, 1x volume of chloroform and vortex, 3x volumes of ice-cold water and vortex, and centrifuged at 14000 g for 2 min, at 4 °C. The top aqueous layer was removed, and 4x volumes of methanol were added. After centrifugation at 14000 g for 2 min, 4 °C and methanol were removed without disturbing the protein pellet. The protein was precipitated for 5–10 min at room temperature. 200 μg protein extract was mixed with 200 μl of 8 M urea buffer to redissolve the protein precipitate, and incubated with 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at 55 °C for 25 min. The solution successively reacted with 30 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark, 5 mM DTT for 15 min at room temperature in the dark, 4x volumes of 50 mM Tirs-HCl (pH 8.5), and 1 mM CaCl2. Then trypsin (50 μg trypsin: 1 mg protein) was added for digestion at 37 °C, rotation overnight (14-18 hours). Trifluoroacetic acid (10%) was added to the digested peptides to pH 2-3, which was centrifuged at 11000 g for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube. StageTip with C18 membrane (Thermo Fisher) was washed with 20 μl of methanol, 2000 g for 10 s, with 20 μl of 80% acetonitrile, 0.5% acetic acid at 2000 g for 10 s, with 20 μl of 1% formic acid for twice. The protein sample was resuspended with 100 μl of 1% acetic acid, loaded twice at 400 g for 5 min, and washed with 20 μl of 1% formic acid twice. Then the peptides were eluted with 40 μl of 80% acetonitrile, 0.5% acetic acid. The protein sample was dried via a CentriVap Benchtop Vacuum Concentrator (Labconco) and stored at −20°C for mass spectrometry analysis.

Mass Spectrometry analysis was performed with an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer with a nanospray ion source and an EASY-nLC 1000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A binary mobile phase system was used, buffer A: 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water and buffer B: 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile. Peptides were eluted with a gradient of 7%-22% buffer B for 50 min followed by 22%-35% buffer B for 10 min. The full mass scan was acquired from m/z 350 to 1550 with resolution 120,000 at a target of 2e5 ions, and the MS/MS spectra were obtained in a data-dependent acquisition in the top speed mode with higher-energy collision dissociation (target 5e4 ions, max ion injection time 40 ms, isolation window 1.6 m/z, normalized collision energy 30%). The dynamic exclusion time was set to 30 s.

Raw data were analysed by PEAKS Studio version 8.0 software (Bioinformatics Solutions Inc., Waterloo, Canada). The database was built from the UniProt-proteome UP000000589. The database search was performed with the following parameters: a fragmentation mass tolerance of 0.05 Da; precursor mass tolerance of 15 ppm; static modifications–carbamidomethyl; dynamic modifications–oxidation (HW), and acetylation (N-term). The resulting protein list was filtered by a 1% false discovery rate (FDR).

Venn, Volcano plot, and Heatmap were analysed in Sangerbox (version 3H.W., http://sangerbox.com/). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was applied to elucidate the regulatory networks of interest by forming hierarchical categories according to the biological process, cellular component, and molG.O.ular function of the differentially expressed protein molecules via clusterProfiler package and Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB).

Measurement of endothelial cell contraction

BMECs cultured in the 24-well plate were automatically captured with a live-cell imaging system (Lionheart FX, BioTek). BMECs were pre-treated with EphA4-Fc (10 μg/ml) for 1 h before OGD exposure. After OGD, the cells were continuously exposed to EphA4-Fc. At the beginning of reperfusion and 2 h after reperfusion, BMECs at the exact position of the culture plate were imaged. The degree of cell contraction was expressed as a ratio between the increased space and the total space area on the captured image.

Cell survival assay

Neurons, BMECs, and astrocytes were pre-treated with EphA4-Fc (10 μg/ml) for 1 h before OGD exposure. After OGD for 4 h, the cells were restored with the fresh medium with or without EphA4-Fc for 24 h. Then CCK-8 solution was added to each well in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The optical density at 450 nm was detected using a microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x, Molecular Devices).

Transient MCAO model in mice

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Zhejiang, China). Mice were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled animal facility with a 12 h light/dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech-JY2018065-A1), and carried out in accordance with the regulations set by the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Guangdong Province. Efforts were made to minimize the number of animals and animal suffering according to the ARRIVE reporting guidelines. The G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7) was used to estimate the sample size. A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power version 3.1.9.7 20 to determine the minimum sample size required to test the study hypothesis. Results indicated the required sample size to achieve 80% power for detecting a large effect, at a significance criterion of α = 0.05, was n = 21 using t-test to compare between two independent means (in this case: vehicle vs. treated)]. In the current study, based on our previously published studies using the same animal model and the required local animal care protocol, we used on average 5-7 mice per group, a sample size adequate to test the study hypothesis.

Transient and focal MCAO was induced in male mice (8–10 weeks old, 25–30 g of body weight) by intraluminal occlusion of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA), as we previously described. 21 Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane in air and an 8-0 monofilament with a silicon-coated tip was inserted into the carotid artery to block the blood flow into the MCA. The body temperature of mice was maintained at 37 ± 0.5 °C during surgery utilizing a heating pad. Cortical blood flow (CBF) was measured using laser Doppler flowmetry, and the mice with CBF reduction of at least 75% of baseline level after ischemia were included for further experimentation. After cerebral ischemia for 60 min, the filament was withdrawn, and the blood flow was allowed to resume. After suturing the skin, the mice were kept in an intensive care unit cage. In the sham group, mice were subjected to the same surgery without MCA occlusion. No mice were dead.

EphA4-Fc protein production and administration

EphA4-Fc (PEF, Brisbane, Australia) is a soluble fusion protein in which the extracellular domain of mouse EphA4 is combined with mouse IgG1 Fc fragment. It is an EphA4 antagonist by competitively binding to ephrin-A and -B ligands.22 –25 In this study, EphA4-Fc (5 mg/ml) diluted in the phosphate buffer saline (PBS) was intraperitoneally injected into mice (1 mg per mouse) 1 h before ischemia or at the beginning of reperfusion. Some animals that received the EphA4-Fc treatment post-surgery then received an additional EphA4-Fc treatment once at 20 mg/kg 48 h later. This dose has been proven effective in spinal cord injury and motor neuron disease.23,26 In this study, mice were randomized for treatment, and the investigators were blinded about the vehicle or EphA4-Fc administration. In in vitro experiments, cells were pre-treated with EphA4-Fc (10 μg/ml) for 1 h and underwent the OGD/R condition.

Neurological deficit and motor function assessment

After 24 h or 72 h reperfusion, mice were evaluated using the neurological deficit score and the forelimb grip strength as previously described.12,27 The neurological deficit score was assessed as follows: 0, normal motor function; 1, flexion of the contralateral torso and forelimb on lifting the animal by the tail; 2, circling to the contralateral side but normal posture at rest; 3, leaning to the contralateral side at rest; 4, no spontaneous motor activity. The forelimb grip strength test was performed using the Grip Strength Meter from Columbus Instruments (MyNeurolab, St Louis, MO). At least three measurements were taken for each mouse, and the average value was analyzed. During these experiments, investigators did not know the group allocation and assessed the behavior function of mice.

Measurements of volumes of brain infarction and edema

The procedures were as we have described previously. 27 Briefly, brains were collected and cut into four coronal slices with 2 mm thickness. After staining with 2% 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) solution for 10 min at 37 °C, images of brain slices were immediately captured and analyzed using the Image J software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Percentage of infarct = (volume of the contralateral hemisphere − (volume of intact ipsilateral hemisphere − the volume of ipsilateral infarct hemisphere)/volume of contralateral hemisphere) × 100; Percentage of edema = (volume of the ipsilateral hemisphere − the volume of the contralateral hemisphere)/volume of contralateral hemisphere × 100.

Additionally, edema was evaluated by the wet-dry weighting method after ischemic brain injury. After reperfusion for 24 h, the brains were obtained from tMCAO mice and cut into left and right hemispheres, which were furtherly weighted and placed in an oven at 65 °C for 3 days until constant weight. Percentage of edema = [(wet weight of the ipsilateral hemisphere − dry weight of the ipsilateral hemisphere) − (wet weight of the contralateral hemisphere − dry weight of the contralateral hemisphere)]/(wet weight of the contralateral hemisphere − dry weight of the contralateral hemisphere) × 100 .

BBB permeability assay

The method used to demonstrate BBB leakiness was as previously described.28,29 Briefly, Evans blue (EB) (molecular weight at 961 Da; 4% in saline, 2 ml/kg) or sodium fluorescein (molecular weight at 376.27 Da; 40 mg/kg, 5 ml/kg) was injected via the tail vein. After circulation for 1 h, EB or sodium fluorescein in blood was removed by intracardiac perfusion with PBS. Then the brains were obtained from EB-injected mice, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution, cut into four sections (2 mm for each section), and photographed using a digital camera. Paraformaldehyde fixed brains were immersed in 10% and 30% sucrose solution for dehydration, and the brains were cut into 30 μm thick sections with a freezing microtome (CM1950, Leica, Germany). The EB positive volume and sodium fluorescein positive area was analyzed with Image J software.

Immunofluorescence histochemistry

Ice-cold PBS-infused brains were rapidly collected in optimal cutting temperature compound and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Then the brains were cut into 10 μm thick sections with a freezing microtome for co-staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and F-actin labeled with Phalloidin-iFluor 488. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and washed with PBS. PBS-infused brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 12 h and immersed in 10% and 30% sucrose solution for dehydration. Then the brains were cut into 16 μm thick sections with a freezing microtome (CM1950, Leica, Germany). The brain sections needed antigen retrieval. 30 The sections or cells were incubated with 5% BSA for 1 h to block unspecific binding of the antibodies and incubated with the primary antibodies, including mouse anti-microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2) (Abcam, USA), rabbit anti-zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) (Proteintech, China), rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Abcam, USA) and rabbit anti-Occludin (Proteintech, China) in 3% BSA in a humidified chamber for overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, slices or cells were incubated with Alexa Flour 488/546-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit mouse secondary antibody (Abcam, USA) mixed with Phalloidin-iFluor 488 (Abcam, USA) to label F-actin. The images were captured under a microscope (Axio Observer7, ZEISS, Germany) or an All-in-One fluorescence microscope (BZ-X800LE, KEYENCE). Quantitative analysis was conducted in a double-blind fashion using the Image J software.

Western blotting

Total protein was obtained by lysing BMECs in a radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor. The prepared samples were separated on 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, CA, USA). After blocking with 3% BSA, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, including rabbit-anti p-EphA4 (ECM Bioscience, 1:1000, EP-2731), mouse-anti EphA4 (Invitrogen, 1:500, 37-1600) or mouse-anti β-actin (Abcam, 1:2000, ab8226), washed in TBS-Tween 20, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies (Abcam), which was detected by chemical luminescence and visualized on a luminescent image analyser (Tanon 6100 A, USA). Densitometric analyses were performed using Image J software.

Statistical analysis

Data normality distribution was analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. When the data were normally distributed, multiple groups were compared using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. For comparison between the two groups, the Student's t-test was used. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. A box graph was used where box limits indicate the range of the central 50% of the data, with a central line marking the median value. The IBM SPSS 25 statistical software was used for the statistical analysis. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification of EphA4 during BMECs' response to OGD/R

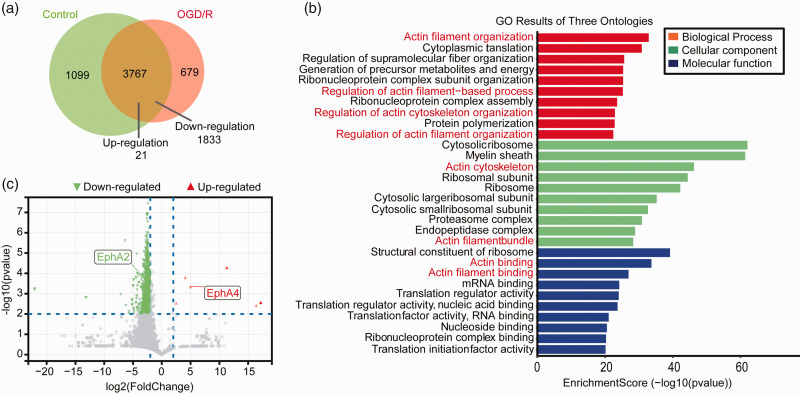

Proteomics analysis was performed on in vitro cultured BMECs exposed to 4 h OGD and 2 h reperfusion treatment to identify molecules potentially involved in post-stroke brain edema. Of the identified 5545 proteins, 3767 of them were expressed in both the untreated control and OGD/R-treated groups (Figure 1(a) and Supplemental File 1). Of these 3767 proteins, there were 1854 proteins differentially expressed in the OGD/R-treated group, with 1833 down-regulated and 21 up-regulated (p < 0.05). The result of GO analysis showed that multiple proteins related to the actin cytoskeleton were altered during OGD/R treatment, suggesting their potential role in changing BMECs' cellular morphology (Figure 1(b)).31,32 Our attention was focused on the 21 up-regulated proteins and their possible functions related to cytoskeleton regulation. EphA4 was up-regulated 4-fold after OGD/R treatment (p < 0.01; Figure 1(c) and Supplementary Fig. 1) and was selected for further analysis.

Figure 1.

Altered protein expression in BMECs treated with OGD/R. Proteomics analysis of BMECs after 4 h OGD and 2 h reperfusion treatment were performed. Venn analysis diagram of identified differentially expressed proteins in BMECs (a). The 1833 down-regulated proteins and 21 up-regulated proteins (p < 0.05, Student's t-test) were subjected to Gene Ontology (GO) analysis (b). Proteins differentially expressed more than 4 folds (p < 0.01, Student's t-test) after OGD/R treatment was shown in the volcano plot (c).

Activation of EphA4 mediates OGD/R-induced contraction of cultured BMECs

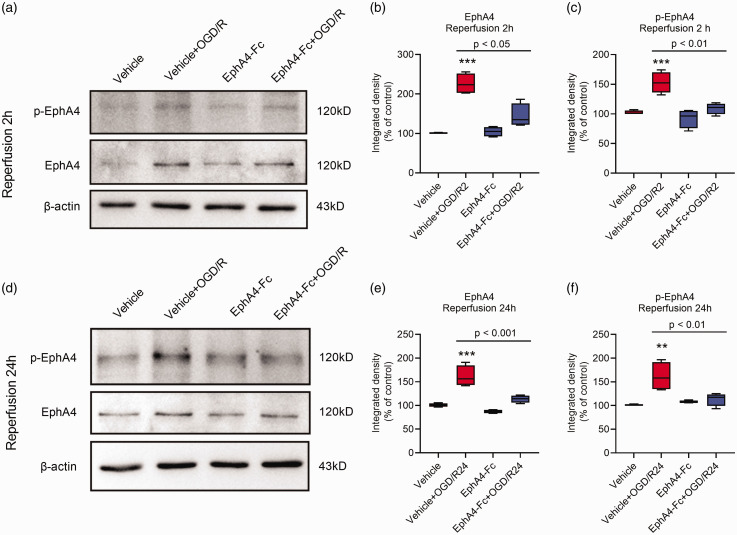

We used Western blotting to confirm the elevated expressions of EphA4 and its activated phosphorylated form (p-EphA4) in BMECs after 4 h OGD followed by 2 h or 24 h reperfusion treatment (Figure 2). We have developed an EphA4 receptor antagonist, EphA4-Fc peptide, a soluble fusion protein combining the extracellular domain of wildtype EphA4 with an IgG Fc fragment. Our previous studies showed that the EphA4-Fc peptide effectively blocked the function of EphA4 and significantly promoted axonal regrowth in rodents after spinal cord injury23,24 and neurogenesis in the hippocampus. 22 Interestingly, the elevated levels of EphA4 and p-EphA4 induced by OGD/R in BMECs were reduced after EphA4-Fc treatment (Figure 2). Importantly, the EphA4-Fc peptide inhibited BMECs stress fiber formation and cellular contraction during the early stage of OGD/R (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Figure 3(a) and (b)). A confluent monolayer of BMECs was treated with OGD in the presence or absence of the EphA4-Fc peptide. Two hours after reperfusion, BMECs altered their morphology and became more polarized, reflecting the formation of actin stress fibers within BMECs (Figure 3(a) and (b)). Intercellular gaps increased during OGD/R and the addition of EphA4-Fc for 2 h significantly reduced the formation of intracellular actin stress fibers and the level of intercellular gaps compared to the vehicle-treated group (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Figure 3(a) and (b)). These data demonstrated that activation of EphA4 promoted OGD/R-induced contraction of BMECs during the early reperfusion stage.

Figure 2.

Quantitative determination of EphA4 expression in BMECs treated with OGD/R. BMECs were treated with 4 h OGD and followed by 2 h or 24 h reperfusion in the presence or absence of EphA4-Fc. Western blotting was performed (a and d) and quantified using β-actin as an internal control for EphA4 and p-EphA4 in BMECs after reperfusion for 2 h (b, c) and 24 h (e, f). Data represent the mean ± SD. Error bars indicate SD. n = 4, **indicates p < 0.01 compared with the vehicle group using two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc analysis.

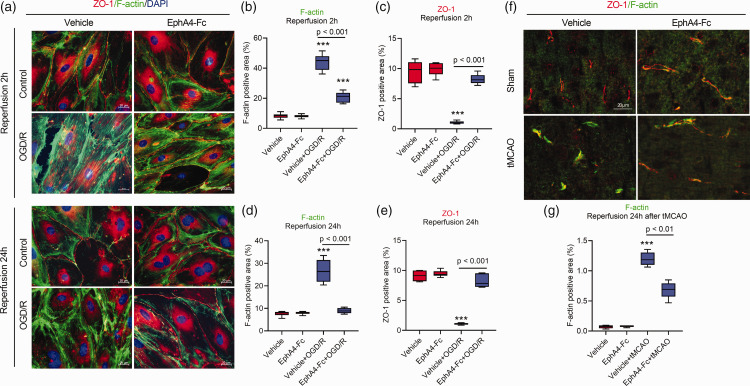

Figure 3.

Blocking EphA4 prevents tight junction damage of OGD/R- or tMCAO-treated BMECs. Cultured BMECs were treated as indicated, followed by fixation for immunostaining with F-actin (green) and ZO-1 (red) (a). The expression levels of F-actin (b, d) and ZO-1 (c, e) were quantified with area. After reperfusion for 24 h, ZO-1 and F-actin were co-stained in the brain tissue of tMCAO-treated mouse (f), and the expression levels of F-actin were quantified (g). Data represent the mean ± SD. Error bars indicate SD. n = 6, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared with the vehicle group by two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc analysis.

EphA4 plays a role in maintaining the tight junctions in OGD/R-treated BMECs

To further understand the role of EphA4 in maintaining endothelial cell integrity, we examined the expression of tight junction proteins ZO-1 and occludin using immunohistochemical staining. The expression levels of ZO-1 in the BMECs treated with or without EphA4-Fc were similar along regions of cell-cell junctions. However, the OGD/R treatment significantly changed the ZO-1 expression patterns. After 2 h of reperfusion, the expression of ZO-1 and occludin appeared fragmented along the length of the cell-cell contact region (Figure 3(a) and (c) and Supplementary Fig. 3). In contrast, the EphA4 inhibition with EphA4-Fc maintained the morphology of ZO-1 immunostaining along the cell-cell contact region, indicating protection of tight junctions. After 24 h of reperfusion, the expression of F-actin in the BMECs in vitro and in vivo significantly increased in the form of intense stress fibers. In contrast, the EphA4-Fc treatment reduced F-actin formation and area along the cell-cell contact region to a degree similar to the control BMECs (Figure 3(a), (d), (f) and (g) and Supplementary Fig. 4). Moreover, the expression of ZO-1 along the cell-cell contact regions were markedly decreased after 24 h reperfusion. At the same time, EphA4-Fc preserved their normal expression levels and patterns (Figure 3(a) and (e)).

These results demonstrated that during the reperfusion time, EphA4 inhibition limited the formation of OGD-induced F-actin stress fibers and contraction of BMECs, and maintained the tight junction architecture as exemplified by the expression patterns of tight junction proteins such as ZO-1. Together, these in vitro data supported the role of EphA4 in maintaining the tight junctions in BMECs.

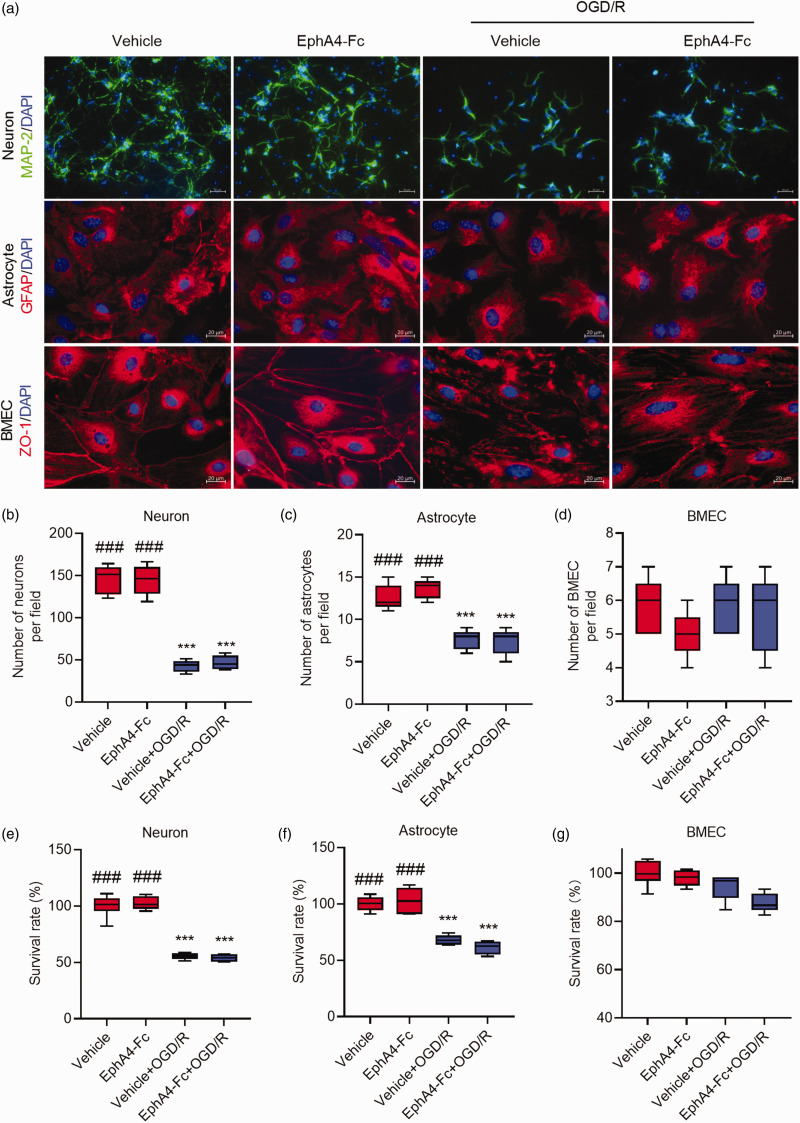

Blocking EphA4 does not prevent OGD/R-induced cell death

To demonstrate whether inhibiting EphA4 prevents OGD/R-induced cell death, cultured primary cortical neurons, astrocytes, and BMECs were subjected to 4 h OGD followed by 24 h reperfusion. Cells were immunostained with markers for neurons, astrocytes, and BMECs, as shown in Figure 4(a), and the cellular viability was determined using a CCK-8 viability assay kit. Significant numbers of neurons (Figure 4(b)) and astrocytes (Figure 4(c)) died during OGD/R. The OGD/R resulted in approximately 50% and 30% of neuronal and astrocytic cell death, respectively (Figure 4(e) and (f)). There were no significant changes in BMECs viability in response to OGD/R (Figure 4(d) and (g)). Interestingly, EphA4 inhibition with EphA4-Fc did not affect OGD/R-induced death of neurons and astrocytes (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

EphA4-Fc did not prevent neuronal death caused by OGD/R. (a) Cultured primary cortical neurons, astrocytes, and BMECs were treated as indicated and followed by immunostaining for MAP-2, GFAP, or ZO-1 with nuclei stained with DAPI (blue color). The number of neurons (b), astrocytes (c), and BMECs (d) per microscopic field were counted and shown. Cell survival rates of neuron (e), astrocytes (f), and BMECs (g), assayed using the CCK-8 assay kit, were shown. Data represent the mean ± SD. Error bars indicate SD. n = 6, ***p < 0.001 vs. vehicle, ###p < 0.001 vs. the vehicle+OGD/R by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis.

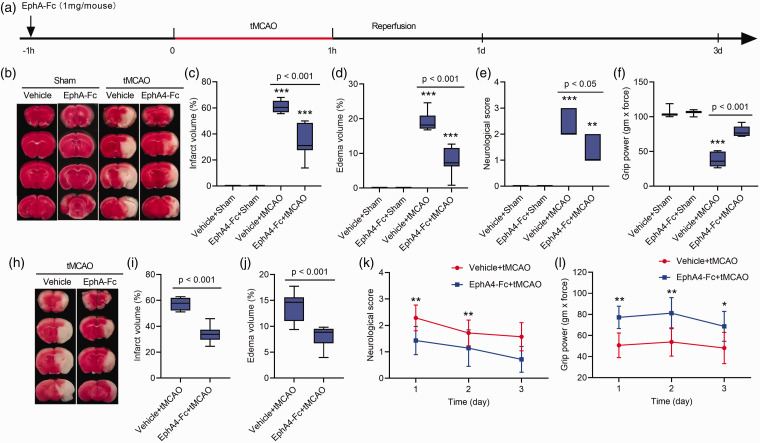

Preoperative administration of EphA4-Fc reduces cerebral edema and confers brain protection

To determine the effect of EphA4 inhibition in the ischemic brain, the EphA4-Fc was administrated in mice 1 h before the tMCAO surgery. The saline vehicle was given to the tMCAO mice serving as a control (Figure 5(a)). The tMCAO caused cerebral blood flow reduction of at least 75% of the baseline level monitored using Doppler flow cytometry (Supplementary Fig. 5). The silicon-coated thread was withdrawn after 60 min MCAO to allow reperfusion. The edema volume, cerebral infarction volume, and motor functions, including neurological deficit score and forelimb grip strength, were examined on the 1-, 2- and 3-d post-tMCAO. Administration of EphA4-Fc 1 h before tMCAO resulted in a remarkable 57.9% reduction in cerebral edema volume in the EphA-Fc treated-tMCAO mice (8.1%) compared to the vehicle-treated tMCAO mice (19.3%) (Figure 5(b) and (d)). Consequently, a significant decrease in the cerebral infarction volume occurred compared to the vehicle-treated tMCAO group examined 1 d post-tMCAO (33.7% vs. 61.4%, respectively) (Figure 5(b) to (c)). EphA4-Fc treatment significantly improved the motor functions of ischemic mice examined at 1 d post-tMCAO (Figure 5(e) and (f)). A near 50% enhancement of neurological deficits (Figure 5(e)) and forelimb grip strength (Figure 5(f)) were recorded in the EphA4-Fc treated group compared to the vehicle-treated tMCAO group. These findings demonstrated a remarkable function of EphA4 in mediating cerebral edema. Blocking EphA4 using EphA4-Fc effectively reduced cerebral edema, ischemic infarction, and neurological deficits.

Figure 5.

Preoperative administration of EphA4-Fc protects the tMCAO brains. (a), a schema of the treatment. (b and h), TTC staining of brain sections at 2 mm thickness to show the infarct area (white) and the normal brain region (red). (c, d, i, j), the infarction and edema volumes were measured from the TTC-stained brain sections. The neurological deficits scores (e, k) and the forelimb grip strength test (f, l) were measured at 1- and 3-d post-tMCAO. Data represent the mean ± SD. Error bars indicate SD. n = 7, ***p < 0.001 vs. the vehicle+sham group by two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test (c-f) or *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. the vehicle+tMCAO group by Student's t-test analysis (k, l).

To determine the long-term effect of this one-time preoperative EphA4-Fc treatment, we performed tMCAO surgery on another cohort of mice and evaluated brain changes 3 d post-tMCAO. A significant reduction in edema volume and brain infarction occurred at 3 d post-tMCAO in the EphA4-Fc treated mice compared to the vehicle-treated tMCAO mice (Figure 5(h) to (j)). Furthermore, the preoperative EphA4-Fc treatment resulted in sustained improvements in motor functions compared with the vehicle-treated tMCAO group (Figure 5(k) and (l)). These results demonstrated that the one-time preoperative administration of EphA4-Fc can provide long-term ischemic brain protection.

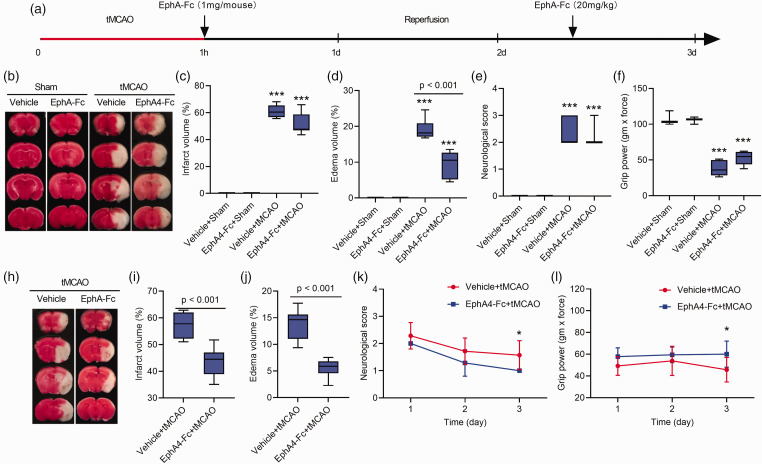

Postoperative administration of EphA4-Fc also effectively ameliorated vasogenic edema and ischemic brain injury

To mimic stroke treatment in a clinical setting, we administered EphA4-Fc 1 h after cerebral ischemia, followed by a booster injection at the same dosage on the 2 d during reperfusion (Figure 6(a)). This experimental design was to determine if delayed blocking of EphA4 could also reduce vasogenic edema and preserve motor functions. To our surprise, a 49.7% decrease in edema volume was seen at 1 d post-tMCAO compared between the EphA4-Fc-treated (9.7%) and the vehicle-treated tMCAO groups (19.3%) (Figure 6(b) and (d)), despite the lack of significant changes in the brain infarct volume (Figure 6(b) and (c)) and motor functions (Figure 6(b), (e) and (f)) at this early time point of post-tMCAO.

Figure 6.

Postoperative administration of EphA4-Fc reduces vasogenic edema in the tMCAO brains. (a), a schema of the treatment time course. (b, h), TTC staining of brain sections at 2 mm thickness to show the infarct area (white) and the normal brain region (red). (c, d, i, j), the infarction and edema volume was measured from the TTC-stained brain sections. The neurological deficits scores (e, k) and the forelimb grip strength test (f, l) were measured at 1- and 3-d post-tMCAO. Data represent the mean ± SD. Error bars indicate SD. n = 7, ***p < 0.001 vs. the vehicle+sham group by two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test (c-f) or *p < 0.05 vs. the vehicle+tMCAO group by Student's t-test analysis (k, l).

Remarkably, on the 3 d pos-tMCAO, a significant decrease (59.9%) in edema volume appeared in the EphA4-Fc treated group of mice compared to the vehicle-treated tMCAO mice (Figure 6(h) and (j); 5.5% vs. 13.7%, respectively). The cerebral ischemic infarction volume was also reduced from 57.6%to 43.3% compared between the vehicle- and EphA4-Fc-treated groups (Figure 6(h) and (i)). The postoperative administration EphA4-Fc also significantly improved motor functions at 3 d post-tMCAO with an enhancement of neurological deficit scores and forelimb grip strength of the EphA4-Fc treated mice compared to the vehicle-treated control mice (Neurological deficit score: 1.00 vs. 1.57; Forelimb grip strength: 60.0 vs. 45.7; respectively) (Figure 6(k) and (l)).

These results demonstrated the function of EphA4 in mediating the early onset of vasogenic edema, resulting in significant neuroprotection and motor function enhancement.

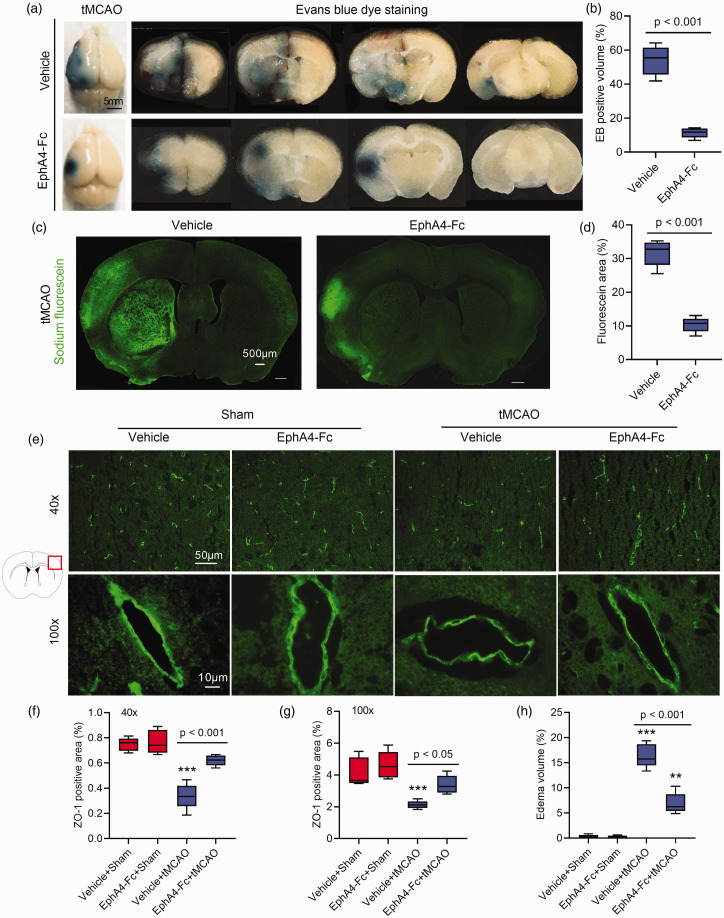

EphA4-Fc protects the BBB integrity and decreases cerebral edema in tMCAO mice

Based on the in vitro BMECs OGD/R data, we postulated that in the cerebral ischemic brain, BMECs EphA4 might function directly to reduce vasogenic edema. The following experiments were, therefore, performed to determine whether in vivo EphA4 inhibition reduces BBB damage and edema in the tMCAO mouse brain. The extravasation of Evens blue (EB) and sodium fluorescein into the brain 24 h post-tMCAO was measured. As shown in Figure 7(a) to (d), EphA4-Fc markedly reduced the EB-positive brain volumes and sodium fluorescein-positive area compared to the vehicle-treated tMCAO mice. This result was consistent with the ability of EphA4-Fc to minimize cerebral edema volume seen at 24 h post-tMCAO.

Figure 7.

EphA4-Fc reduces BBB permeability and cerebral edema. After 24 h reperfusion, tMCAO mouse brains were dissected and photographed after EB injection (a). EphA4-Fc decreased EB (b) or sodium fluorescein (c, d) extravasation in tMCAO brains by Student's t-test analysis. (e) Micrographs showing ZO-1 expression along the vascular endothelial cells located in the cerebral infarct area and the quantification of their area (f, g). Cerebral edema evaluated by the wet-dry weighting method was shown in panel (h). Data represent the mean ± SD. Error bars indicate SD. n = 5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. the vehicle+sham by two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test.

The expression of ZO-1 on BMECs in the infarction cortex from the same EB-treated mouse was also examined using immunohistochemistry. Mice treated with EphA4-Fc significantly maintained the expression levels and patterns of ZO-1 in BMECs compared to the control group (Figure 7(e) to (g)). Furthermore, the brain edema volume assayed by the wet-dry weighting method was also confirmed the 50% reduction in edema in mice treated with the EphA4-Fc at 24 h post-tMCAO (Figure 7(h)).

Collectively, these data strongly supported the idea that inhibition of EphA4 using EphA4-Fc protected the BBB integrity and reduced vasogenic edema, leading to brain protection.

Discussion

The present study identified EphA4 as a critical receptor in mediating ischemic brain vasogenic edema, a life-threatening emergency following a stroke. The findings that inhibition of BMECs EphA4 reduces cerebral edema are exciting, suggesting that BMECs EphA4 is an important molecular target and that the EphA4 blocker, EphA4-Fc, can be a promising drug candidate to treat cerebral vasogenic edema.

EphA4 is a well-characterized Eph receptor that can bind to most Ephrin-A and -B ligands.33,34 Eph/Ephrin forward signaling is known for its roles in neurogenesis, axonal growth, and synaptic plasticity during development and in adults.22,33,35 –39 EphA4's involvement in stroke-induced brain damage was previously thought to be through regulating some of these processes.15 –17 It is only recently that molecular genetic evidence showed that the complete genetic deletion of EphA4 targeted to the endothelial cells significantly diminished the brain lesion size. The molecular mechanism was through EphA4's crosstalk with Tie2 to promote leptomeningeal collateral remodeling and angiogenesis following ischemic stroke. 15 In light of this information, our present study not only provided further support for the involvement of EphA4 in microvessel endothelial cell response to cerebral ischemia but also, for the first time, demonstrated that inhibition of EphA4 conferred brain protection by reducing EphA4-mediated cerebral vasogenic edema.

Ischemic injury and OGD/R can markedly induce the elevation of EphA4 expression in neurons, endothelial cells, and even the whole injured cerebral cortex.15,40 EphA4-Fc can effectively block the interaction of Ephrins and EphA4, and inhibit the elevation of EphA4 signal.23,40,41 As shown in Figure 2, treatment of cultured BMECs with EphA4-Fc did not alter EphA4 and p-EphA4 levels (panels A and D, lanes 1 and 3), indicating that EphA4-Fc alone does not affect the steady-state of EphA4 transcription and EphA4 phosphorylation. Thus, the significant decrease in the elevated levels of EphA4 and p-EphA4 may be through an indirect mechanism by a yet unknown signaling pathway. The protective effect of EphA4-Fc during OGD/R may trigger the activation of transcription factors specific for reducing EphA4 expression and the subsequent phosphorylation of EphA4. These possible mechanisms require further studies.

Several lines of evidence are provided in the present study to support the role of BMECs EphA4 in maintaining BBB integrity. First, OGD/R treatment of in vitro cultured primary BMECs is an excellent model to mimic cerebral ischemia in vivo. The proteomic analysis of OGD/R-treated BMECs allowed the identification of changes in many cytoskeletal proteins potentially responsible for maintaining the cellular morphology of BMECs. The correct expression of cytoskeletal proteins is crucial in forming a tight junction seal in the brain microvessels to prevent water leakage in keeping cerebral osmotic homeostasis. Using this approach, we identified the differentially expressed EphA4. The Western blotting results showed that OGD/R evoked an increased expression of the phosphorylated form of EphA4 (p-EphA4), indicating the activation of EphA4 during OGD/R. The activated EphA4 of BMECs was associated with BMECs contractions, formation of stress fibers, and tight junction damage during OGD/R treatment since blocking EphA4 using EphA4-Fc inhibited the rise of p-EphA4 and the associated deleterious effects on BMECs. Second, the EphA4-Fc could not effectively prevent neuronal death in response to OGD/R. Third, EphA4-Fc significantly reduced the early onset of vasogenic edema and EB extravasation before the appearance of brain protection post-tMCAO in vivo. These data strongly support the role of EphA4 of the BMECs in mediating BBB breakdown and vasogenic edema in the ischemic brain.

Our previously published works demonstrated that the EphA4 receptor antagonist, EphA4-Fc, effectively promotes axonal regrowth in rodents after spinal cord injury,23,24 increases the proliferation of precursors in the hippocampus, 22 and improves survival of motor neurons in an animal model of motor neuron disease (SOD1G93A). 26 The present study revealed an important function of EphA4-Fc in reducing cerebral vasogenic edema. The EphA4-Fc is well tolerated in our ongoing phase I human clinical trials. The effective dosage of EphA4-Fc used in the present study was based on our prior knowledge of the half-life of EphAA4-Fc. 24 It was remarkable that EphA4-Fc administered before or after tMCAO significantly decreased the acute occurrence of vasogenic edema. Not only the ischemic brains were better protected, but the ischemic mice that received EphA4-Fc treatment also performed better in motor skill tests than the vehicle-treated ischemic control mice. These data indicate that EphA4-Fc can be an excellent candidate for development to treat stroke brain vasogenic edema.

Despite agreements with previous reports showing rapid endothelial cytoskeletal reorganization enabling early BBB disruption and long-term ischemia-reperfusion brain injury, 42 the downstream mechanism of how EphA4 affects intracellular signaling impacts the appearance of F-actin stress fibers and BBB integrity remains unclear. Future studies will be focused on the endothelial tight junctions, transporters, Wnt/β-catenin, and angiopoietin/Tie2 signaling pathways, which are all critical in BBB integrity.43 –46

This study's limitations include the lack of validated anti-EphA4 antibody for labeling EphA4 in BMECs with the immunofluorescence method and limited analysis of the proteomic data. The molecular mechanism of how EphA4 regulates the actin network of BMECs, also requires further studies.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that microvessel endothelial EphA4 maintains BBB integrity and cerebral edema during ischemic stroke. Applying EphA4-Fc, an EphA4 inhibitor, significantly decreases the early onset of edema by blocking the deformation of BMECs and maintaining the expression of tight junction proteins. Future studies are warranted to unveil the downstream signaling pathways of EphA4 in maintaining BBB integrity and modulating vasogenic edema.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X231209607 for Inhibition of EphA4 reduces vasogenic edema after experimental stroke in mice by protecting the blood-brain barrier integrity by Shuai Zhang, Jing Zhao, Wei-Meng Sha, Xin-Pei Zhang, Jing-Yuan Mai, Perry F Bartlett and Sheng-Tao Hou in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-jcb-10.1177_0271678X231209607 for Inhibition of EphA4 reduces vasogenic edema after experimental stroke in mice by protecting the blood-brain barrier integrity by Shuai Zhang, Jing Zhao, Wei-Meng Sha, Xin-Pei Zhang, Jing-Yuan Mai, Perry F Bartlett and Sheng-Tao Hou in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-jcb-10.1177_0271678X231209607 for Inhibition of EphA4 reduces vasogenic edema after experimental stroke in mice by protecting the blood-brain barrier integrity by Shuai Zhang, Jing Zhao, Wei-Meng Sha, Xin-Pei Zhang, Jing-Yuan Mai, Perry F Bartlett and Sheng-Tao Hou in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Acknowledgements

We thank SUSTech Animal Facility for providing animal care and services.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by grants to STH from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81871026); Shenzhen-Hong Kong Institute of Brain Science-Shenzhen Fundamental Research Institutions (2022SHIBS0002); Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee Research Grants (JCYJ20180504165806229; KQJSCX20180322151111754); Shenzhen Sanming Project (Baoan Hospital, 2018.06). STH and PFB are also supported by the Guangdong Innovation Platform of Translational Research for Cerebrovascular Diseases and SUSTech-UQ Joint Center for Neuroscience and Neural Engineering (CNNE). STH is a Pengcheng Peacock Plan (A) Distinguished Professor.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions: SZ, WMS, XPZ, and JYM performed experiments and collected data; SZ and JZ analyzed data and wrote the first draft; PFB and STH supervised the project, provided funding, and wrote the final draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD: Sheng-Tao Hou https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9736-342X

References

- 1.Beal CC. Gender and stroke symptoms: a review of the current literature. J Neurosci Nurs 2010; 42: 80–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi DW, Rothman SM. The role of glutamate neurotoxicity in hypoxic-ischemic neuronal death. Annu Rev Neurosci 1990; 13: 171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta A, Mahale R, Buddaraju K, et al. Efficacy of neuroprotective drugs in acute ischemic stroke: is it helpful? J Neurosci Rural Pract 2019; 10: 576–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu S, Yuan R, Wang Y, et al. Early prediction of malignant brain edema after ischemic stroke. Stroke 2018; 49: 2918–2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen S, Shao L, Ma L. Cerebral edema formation after stroke: emphasis on blood-brain barrier and the lymphatic drainage system of the brain. Front Cell Neurosci 2021; 15: 716825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halstead MR, Geocadin RG. The medical management of cerebral edema: past, present, and future therapies. Neurotherapeutics 2019; 16: 1133–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah S, Kimberly WT. Today's approach to treating brain swelling in the neuro intensive care unit. Semin Neurol 2016; 36: 502–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clément T, Rodriguez-Grande B, Badaut J. Aquaporins in brain edema. J Neurosci Res 2020; 98: 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreier JP, Lemale CL, Kola V, et al. Spreading depolarization is not an epiphenomenon but the principal mechanism of the cytotoxic edema in various gray matter structures of the brain during stroke. Neuropharmacology 2018; 134: 189–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Me O. Chapter 30 – ion and water transport across the blood–brain barrier. In: Alvarez-Leefmans FJ, Delpire E. (eds) Physiology and pathology of chloride transporters and channels in the nervous system. Academic Press: San Diego, 2010, pp.585–606. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang S, An Q, Wang T, et al. Autophagy- and MMP-2/9-mediated reduction and redistribution of ZO-1 contribute to hyperglycemia-increased blood-brain barrier permeability during early reperfusion in stroke. Neuroscience 2018; 386: 351–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang S, Song X-Y, Xia C-Y, et al. Effects of cerebral glucose levels in infarct areas on stroke injury mediated by blood glucose changes. RSC Advances 2016; 6: 93815–93825. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michinaga S, Koyama Y. Pathogenesis of brain edema and investigation into anti-edema drugs. Int J Mol Sci 2015; 16: 9949–9975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo ZW, Ovcjak A, Wong R, et al. Drug development in targeting ion channels for brain edema. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2020; 41: 1272–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okyere B, Mills WA, Wang X, et al. EphA4/Tie2 crosstalk regulates leptomeningeal collateral remodeling following ischemic stroke. J Clin Invest 2020; 130: 1024–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Boer A, Storm A, Gomez-Soler M, et al. Environmental enrichment during the chronic phase after experimental stroke promotes functional recovery without synergistic effects of EphA4 targeted therapy. Hum Mol Genet 2020; 29: 605–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemmens R, Jaspers T, Robberecht W, et al. Modifying expression of EphA4 and its downstream targets improves functional recovery after stroke. Hum Mol Genet 2013; 22: 2214–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seibenhener ML, Wooten MW. Isolation and culture of hippocampal neurons from prenatal mice. J Vis Exp 2012; 65: e3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schildge S, Bohrer C, Beck K, et al. Isolation and culture of mouse cortical astrocytes. J Vis Exp 2013; 71: e50079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. G*power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007; 39: 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gangaraju S, Sultan K, Whitehead SN, et al. Cerebral endothelial expression of Robo1 affects brain infiltration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils during mouse stroke recovery. Neurobiol Dis 2013; 54: 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao J, Taylor CJ, Newcombe EA, et al. EphA4 regulates hippocampal neural precursor proliferation in the adult mouse brain by d-serine modulation of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor signaling. Cereb Cortex 2018; 29: 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spanevello MD, Tajouri SI, Mirciov C, et al. Acute delivery of EphA4-Fc improves functional recovery after contusive spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 2013; 30: 1023–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldshmit Y, Spanevello MD, Tajouri S, et al. EphA4 blockers promote axonal regeneration and functional recovery following spinal cord injury in mice. PLoS One 2011; 6: e24636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldshmit Y, Galea MP, Wise G, et al. Axonal regeneration and lack of astrocytic gliosis in EphA4-deficient mice. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 10064–10073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao J, Cooper LT, Boyd AW, et al. Decreased signalling of EphA4 improves functional performance and motor neuron survival in the SOD1(G93A) ALS mouse model. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 11393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang S, Zhang X, Zhong H, et al. Hypothermia evoked by stimulation of medial preoptic nucleus protects the brain in a mouse model of ischaemia. Nat Commun 2022; 13: 6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hou ST, Nilchi L, Li X, et al. Semaphorin3A elevates vascular permeability and contributes to cerebral ischemia-induced brain damage. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 7890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malmgren LT, Olsson Y. Differences between the peripheral and the central nervous system in permeability to sodium fluorescein. J Comp Neurol 1980; 191: 103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang S, Shao SY, Song XY, et al. Protective effects of forsythia suspense extract with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties in a model of rotenone induced neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology 2016; 52: 72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kania A, Klein R. Mechanisms of ephrin-Eph signalling in development, physiology and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016; 17: 240–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mostowy S, Cossart P. Septins: the fourth component of the cytoskeleton. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012; 13: 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lemke G. A coherent nomenclature for eph receptors and their ligands. Mol Cell Neurosci 1997; 9: 331–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowden TA, Aricescu AR, Nettleship JE, et al. Structural plasticity of eph receptor A4 facilitates cross-class ephrin signaling. Structure 2009; 17: 1386–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aoki M, Yamashita T, Tohyama M. EphA receptors direct the differentiation of mammalian neural precursor cells through a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 32643–32650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davy A, Soriano P. Ephrin signaling in vivo: look both ways. Dev Dyn 2005; 232: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez A, Soriano E. Functions of ephrin/eph interactions in the development of the nervous system: emphasis on the hippocampal system. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2005; 49: 211–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuijper S, Turner CJ, Adams RH. Regulation of angiogenesis by eph-ephrin interactions. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2007; 17: 145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Genander M, Frisen J. Ephrins and eph receptors in stem cells and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2010; 22: 611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen F, Liu Z, Peng W, et al. Activation of EphA4 induced by EphrinA1 exacerbates disruption of the blood-brain barrier following cerebral ischemia-reperfusion via the rho/ROCK signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med 2018; 16: 2651–2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woodruff TM, Wu MC, Morgan M, et al. Epha4-Fc treatment reduces ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced intestinal injury by inhibiting vascular permeability. Shock 2016; 45: 184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi Y, Zhang L, Pu H, et al. Rapid endothelial cytoskeletal reorganization enables early blood-brain barrier disruption and long-term ischaemic reperfusion brain injury. Nat Commun 2016; 7: 10523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao Y, Zhang Y, Liao X, et al. Potential therapies for cerebral edema after ischemic stroke: a mini review. Front Aging Neurosci 2020; 12: 618819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stokum JA, Gerzanich V, Sheth KN, et al. Emerging pharmacological treatments for cerebral edema: Evidence from clinical studies. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2020; 60: 291–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abdullahi W, Tripathi D, Ronaldson PT. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction in ischemic stroke: targeting tight junctions and transporters for vascular protection. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2018; 315: C343–c356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liebner S, Dijkhuizen RM, Reiss Y, et al. Functional morphology of the blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol 2018; 135: 311–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X231209607 for Inhibition of EphA4 reduces vasogenic edema after experimental stroke in mice by protecting the blood-brain barrier integrity by Shuai Zhang, Jing Zhao, Wei-Meng Sha, Xin-Pei Zhang, Jing-Yuan Mai, Perry F Bartlett and Sheng-Tao Hou in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-jcb-10.1177_0271678X231209607 for Inhibition of EphA4 reduces vasogenic edema after experimental stroke in mice by protecting the blood-brain barrier integrity by Shuai Zhang, Jing Zhao, Wei-Meng Sha, Xin-Pei Zhang, Jing-Yuan Mai, Perry F Bartlett and Sheng-Tao Hou in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-jcb-10.1177_0271678X231209607 for Inhibition of EphA4 reduces vasogenic edema after experimental stroke in mice by protecting the blood-brain barrier integrity by Shuai Zhang, Jing Zhao, Wei-Meng Sha, Xin-Pei Zhang, Jing-Yuan Mai, Perry F Bartlett and Sheng-Tao Hou in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism