Abstract

Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) is an innate immune receptor that localizes to endosomes in antigen presenting cells and recognizes single stranded unmethylated CpG sites on bacterial genomic DNA. Previous bioinformatic studies have indicated that the genome of the human pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis contains TLR9 stimulatory motifs, and correlative studies have implied a link between human TLR9 (hTLR9) genotype variants and susceptibility to infection. Here we present our evaluation of the stimulatory potential of C. trachomatis gDNA and its recognition by hTLR9- and murine TLR9 (mTLR9)-expressing cells. We confirm that hTLR9 colocalizes with chlamydial inclusions in the pro-monocytic cell line, U937. Utilizing HEK293 reporter cell lines, we demonstrate that purified genomic DNA from C. trachomatis can stimulate hTLR9 signaling, albeit at lower levels than gDNA prepared from other Gram-negative bacteria. Interestingly, we found that while C. trachomatis is capable of signaling through hTLR9 and mTLR9 during live infections in non-phagocytic HEK293 reporter cell lines, signaling only occurs at later developmental time points. Chlamydia-specific induction of hTLR9 is blocked when protein synthesis is inhibited prior to the RB-to-EB conversion and exacerbated by the inhibition of lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis. The induction of aberrance / persistence also significantly alters Chlamydia-specific TLR9 signaling. Our observations support the hypothesis that chlamydial gDNA is released at appreciable levels by the bacterium during the conversion between its replicative and infectious forms and during treatment with antibiotics targeting peptidoglycan assembly.

Keywords: Chlamydia, Innate Immunity, TLR9, pathoadaptation, persistence

INTRODUCTION

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium that utilizes a unique biphasic developmental cycle1. The pathogen has three morphological forms; an Elementary Body (EB) that is infectious, but non-replicating, a Reticulate Body (RB) that is the replicative but non-infectious, and an aberrant body (AB) that is thought to be a defensive response by the bacterium to extracellular stressors. The microbe spends the majority of its existence in an intracellular pathogenic vesicle called an inclusion, where it is protected from a number of immune responses to bacterial infections2.

Chlamydia species are recognized by the innate immune system via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD-like Receptors (NLRs), which respond to various components of bacterial and viral pathogens3. This early interaction initiates a cytokine signaling cascade that results in the recruitment of immune cells to the area in order to fight off the infection and direct a subsequent, cell-mediated adaptive response4. TLRs play an important role in numerous infections of the female lower genital tract5, and a number of studies have investigated the importance of various immunostimulatory chlamydial components (lipids / lipoproteins / MOMP / HSP60, Lipooligosaccharide; LOS, peptidoglycan) and their cognizant innate immune receptors (TLR2, TLR4, NOD1/2), respectively3. The predominantly held view is that TLR2 plays a major role during chlamydial infections, while TLR4 and NOD1/2 are accessory and play a more supportive role6. This assessment is based largely on the fact that Chlamydia species produce less immunostimulatory LOS7–9 and peptidoglycan10–14 than similarly sized Gram-negative bacteria, supporting the hypothesis that these differences represent pathoadaptations by the organism that enable it to subvert the hos’s innate immune system2,15.

Considerably less is known about the role of the innate immune receptor TLR9 during Chlamydia infections. TLR9 recognizes single stranded, unmethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanosine (CpG) sites on bacterial genomic DNA16. Unlike TLR2/4 and NOD1/2, which are broadly expressed by a large number of cell types, TLR9 is expressed almost exclusively in monocytes and dendritic cells16–18. In addition to being expressed in only a small subset of cell populations, TLR9 is exclusively found within vesicles associated with the endosomal maturation pathway. When phagocytic cells ingest foreign, extracellular bacteria, TLR9 is translocated to the endosomal compartment19 and signals after trafficking to the lysosome where it interacts with the DNA released from bacteria undergoing degradation20. While C. trachomatis avoids fusing with vesicles in the endosomal maturation pathway in most cell types21–27, this is not the case in many immune cells that actively express TLR928–31.

Because many TLR9 stimulatory (and inhibitory) signaling motifs have been identified, it is possible to estimate the stimulatory potential of genomic DNA from any microbe whose genome has been sequenced32. C. trachomatis stimulatory DNA CpG motifs have been calculated in the low-to-mid range33,34, indicating that its gDNA is likely recognizable by TLR9. Correlative studies have found that TLR9 gene polymorphisms are associated with increased risk of cervicitis35 and pathology associated with Chlamydia infections in human patients36, as well as susceptibility to Chlamydia infection in ruminants37. Despite these observations, studies investigating TLR9’s role in responding to Chlamydial infections in animal models have demonstrated little to no significant association with infectivity or disease presentation34,38,39, leading us to question the degree to which TLR9 signaling occurs in Chlamydia-infected cells.

Here we present an analysis of the stimulatory potential of gDNA from C. trachomatis and through a series of experiments demonstrate its ability to interact with TLR9.

RESULTS

Genomic DNA from C. trachomatis induces hTLR9 signaling in vitro.

We began our study by first confirming that gDNA isolated from C. trachomatis was capable of initiating a signaling cascade through TLR9. Utilizing a human TLR9-expression reporter cell line (hTLR9-HEK-Blue) we examined secreted Embryonic Alkaline Phosphatase (SEAP) activity in the supernatants of reporter cells exposed to various concentrations of sonicated gDNA obtained from three different bacterial species; Escherichia coli (strain MG1655), Chlamydia trachomatis (serovar L2, strain Bu / 434), and Chlamydia muridarum (strain Nigg). E. coli gDNA was highly stimulatory, C. muridarum gDNA exhibited no stimulatory activity, and C. trachomatis gDNA was somewhat stimulatory, ~50x less stimulatory than E. coli gDNA (Fig. 1). We took these results as confirmation that gDNA (purified from C. trachomatis EBs) can act as a positive stimulatory ligand for hTLR9, but that Chlamydia-specific TLR9 signaling is (as predicted by in silico analysis33) not as robust as that of other Gram-negative bacteria.

Figure 1: Genomic DNA from C. trachomatis induces hTLR9 signaling in vitro.

A human TLR9 (hTLR9) HEK 293 reporter system was used to evaluate the stimulatory potential of sonicated genomic DNA isolated from Escherichia coli (strain MG1655), C. trachomatis (strain L2 434/Bu), and Chlamydia muridarum (strain Nigg). Data presented are the mean of three independent, biological replicates and error bars represent standard error of the mean. Groups were compared via one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. ****, p ≤ 0.0001; ***, p ≤ 0.001. All comparisons to the media control not shown were not significant.

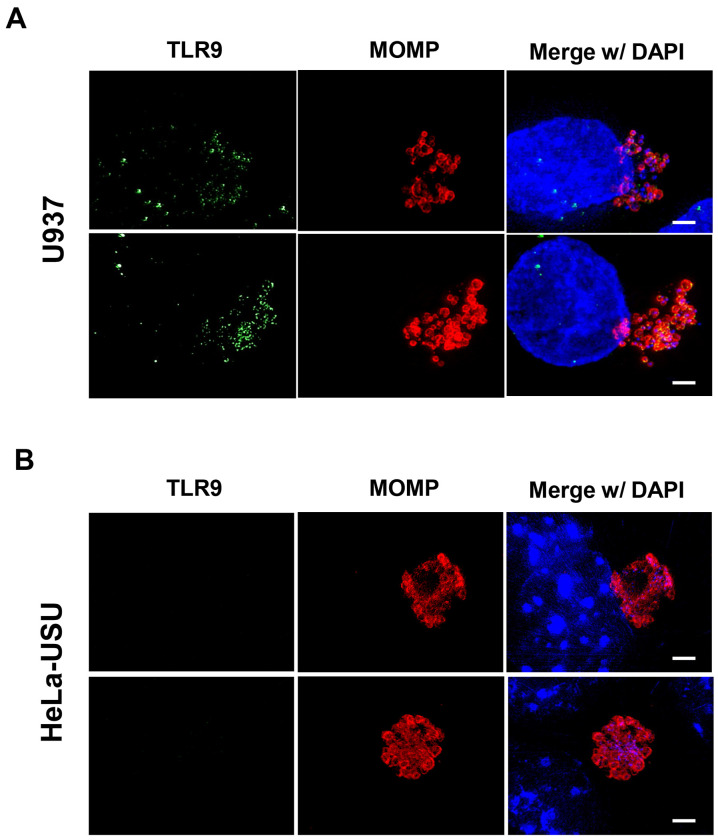

hTLR9 co-localizes with C. trachomatis in U937 cells.

In unstimulated immune cells, TLR9 is maintained in the endoplasmic reticulum20,40. Upon stimulation, the receptor traffics through the Golgi Complex and primarily localizes to endolysosomes41, where it can interact with any foreign bacterial DNA sampled from the environment. While chlamydial inclusions are generally thought to be non-fusogenic with endosomes and lysosomes in most cell types21–27, the exception to the rule is macrophages and certain specialized dendritic cells28–31. While TLR9 is thought to be expressed in only subsets of dendritic cells and B cells in humans42, previous studies have demonstrated CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) signaling in the human monocyte-derived cell line U93743–45. To assess whether Chlamydia resides within TLR9-containing compartments within U937 cells, we conducted an immunolabeling experiment with cells infected with C. trachomatis. At 40 hpi, hTLR9 colocalizes with C. trachomatis inclusions in U937 cells (Fig. 2A), indicating that this receptor successfully traffics to the inclusion in this cell line. Infected HeLa cells were used as a negative immunolabeling control, and no hTLR9 labeling was observed in the proximity of inclusions or anywhere in the infected cells (Fig. 2B). These observations indicate that both C. trachomatis and hTLR9 associate within the same intracellular vacuole within this human monocyte-derived cell line.

Figure 2. hTLR9 localizes to C. trachomatis inclusions in U937 cells.

(A) U937 (pro-monocytic, human myeloid leukemia derived) and (B) HeLa cells were infected via rocking incubation with C. trachomatis at a MOI of ~5. At 40 hpi, cells were fixed in 10% PFA, blocked with 3% BSA, and labeled with polyclonal antibodies to the pathogen’s Major Outer Membrane Protein (MOMP) and TLR9. Images presented are Maximum Intensity Projections from zStacks acquired from a Zeiss PS.1 ELYRA imaging system and are representative of over 40 fields of view observed over two separate labeling experiments. Scale bar ~5 μm.

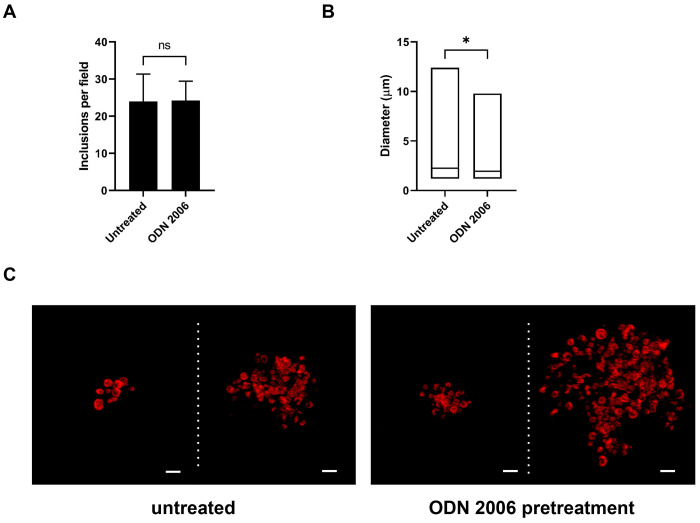

Pre-exposure to stimulatory TLR9 ligands has a minor but measurable effect on the development of C. trachomatis in U-937 cells.

While C. trachomatis gDNA does stimulate signaling through hTLR9, it is significantly less immunostimulatory when compared to other bacteria (Fig 1, 33). Previous researchers have proposed that this represents a shared pathoadaption by bacterial STIs, enabling them to suppress their immunogenicity and evade or delay cell-mediated immune responses33. We sought to test this hypothesis by examining whether pre-treatment of U937 cells with a known hTLR9 agonist (ODN 2006) resulted in higher tolerance to subsequent infection by C. trachomatis. We found that cells pretreated with ODN 2006 appeared to be just as susceptible to infection as non-pretreated cells, as measured by inclusion forming unit counts at 24 hpi (Fig. 3A), however, there was a measurable difference (p<0.05) in the overall size of inclusions between the two groups, with fewer large (> 5μm diameter) inclusions present in the pretreated group (Fig. 3B). The vast majority of cells under both conditions contained small inclusions with only a few bacteria present, and the larger inclusions appeared oddly-shaped containing RBs that appeared dispersed and not closely associated with inclusion walls (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3: Pre-stimulation with a TLR9 agonist has a minor but measurable impact on the growth / development of C. trachomatis in the TLR9-expressing cell line U937.

(A) The average number of inclusions observed per field of view (from 20 fields) in U937 cells that were left untreated or pretreated with the TLR9 agonist ODN 2006 for 18 hours prior to infection with C. trachomatis. Cell monolayers were fixed and labeled at 24 hpi. (B) Inclusion size measurements in U937 cells that were untreated or pretreated with ODN 2006 prior to infection. Data from two separate experiments were pooled for the analysis, and groups were compared via unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. *, p< 0.05. (C) Representative images of larger (≥ 5 μm) inclusions containing multiple RB-sized bacteria found in Chlamydia-infected U937 cells. All cells were fixed and imaged 24 hpi. Scale bar, ~2 μm.

Infection with live C. trachomatis, but not live C. muridarum, induces hTLR9 signaling in HEK293 reporter cells late in the pathogen’s developmental cycle.

While we effectively demonstrated that chlamydial gDNA is immunostimulatory and recognized by TLR9 (Fig. 1), we reasoned that because the trafficking of extracellular gDNA to TLR9-containing vesicles is dependent on endosomes19, this would likely be the case for Chlamydia-specific TLR9 signaling as well. However, as chlamydial inclusions only associate with endosomes / lysosomes in dendritic cells, and our hTLR9 reporter cell line is not of monocytic origin46, we questioned whether direct infection of hTLR9-expressing HEK-293 cells with C. trachomatis would result in measurable, hTLR9-specific SEAP activity. To test this, reporter cells were infected with C. trachomatis at a MOI of either 2 or 0.2 and SEAP activity was assessed at 24 and 40 hours post infection (hpi). Surprisingly, direct infections did result in measurable, dose-dependent hTLR9 activity, albeit significant signaling did not occur until the later stages of the pathogen’s develoμmental cycle (Fig. 4A). Follow-up assays demonstrated that this signaling was unique to C. trachomatis, as live infections with C. muridarum did not result in similar hTLR9-specific activity (Fig. 4B). To account for the possibility that C. trachomatis-specific hTLR9 signaling was due to the presence of extracellular gDNA from killed / lysed bacteria present in the infection inoculum, we ran the assay comparing the signaling potential of live vs. heat-killed organisms, and found measurable TLR9 signaling activity only during live infections (Fig. 4C). These observations indicate that chlamydial viability is required for this late-stage signaling observed in our hTLR9 reporter cells.

Figure 4: C. trachomatis-induced hTLR9 signaling occurs late in the pathogen’s developmental cycle in non-phagocytic cells.

(A) SEAP activity was measured from the supernatants of hTLR9- and Null 1-HEK 293 reporter cells infected with C. trachomatis serovar L2 (strain Bu/434) at 24 and 40 hpi. (B) A comparison of the hTLR9-dependent SEAP activity present in supernatants obtained from reporter cells infected with either C. trachomatis or C. muridarum for 48 hours. (C) hTLR9 signaling assessed at 48 hpi for live and heat-killed C. trachomatis EBs. For all panels, columns represent the mean value calculated for data acquired from three separate experiments (biological replicates) and error bars represent standard error of the mean. Groups were compared via two-way and one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons, respectively. ****, p ≤ 0.0001; ***, p ≤ 0.001; ns, not significant.

Both live C. trachomatis and C. muridarum signal through mTLR9 signaling in HEK293 reporter cells.

We found it curious that C. trachomatis appeared to signal more robustly through hTLR9 than C. muridarum, as we had hypothesized that each pathogen would have evolved to minimize the immunogenicity to the TLRs of their respective host species. To examine this question of cross-species recognition further, we conducted an additional strain comparison using a reporter cell line expressing the murine allele of TLR9 (mTLR9). mTLR9 has been shown to exhibit structural differences from hTLR9 and recognizes different CpG motifs42,47. We examined three different MOIs for each organism (10, 1, and 0.1), and observed mTLR9 signaling at the 24 hpi time point for both C. trachomatis or C. muridarum when our highest MOI was used (Fig. 5A). At the 48 hpi time point, mTLR9 signaling was observable at MOIs as low as 1 (Fig. 5B), and when compared directly, C. trachomatis signaling was approximately twice that of C. muridarum at both time points examined (Fig. 5C, D). When combined with the purified gDNA data, these observations demonstrate that C. muridarum is significantly less stimulatory than C. trachomatis as assessed by both the human and murine TLR9 receptors.

Figure 5: Both C. trachomatis and C. muridarum signal through mTLR9 during live infections of HEK293 reporter cells.

SEAP activity was measured from the supernatants of mTLR9-HEK 293 reporter cells infected with C. trachomatis and C. muridarum at 24 (A) and 48 hpi (B). A side-by-side comparison of the stimulatory activity of each strain is presented for 24 (C) and 48 (D) hpi. For all panels, columns represent the mean value calculated for data acquired from three biological replicates and error bars represent standard error of the mean. Groups were compared via one-way and two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons, respectively. ****, p ≤ 0.0001; ***, p ≤ 0.001; **, p<0.01; ns, not significant.

Chlamydia-specific TLR9 signaling in HEK293 cells occurs as a result of the RB-to-EB conversion.

Given that we did not observe Chlamydia-specific hTLR9 signaling at 24 hpi (Fig. 4A), we reasoned that this could be due to one of two possibilities: 1) that not enough intracellular bacterial replication had occurred to meet the threshold needed for detection by TLR9 and / or 2) that chlamydial gDNA availability varied at different time points post infection. The conversion between the chlamydial replicative and infectious forms begins to occur (in cultured epithelial cells) between ~20-24 hpi48,49. To determine whether the interruption of chlamydial EB development affects Chlamydia-specific TLR9 signaling, we measured signaling in Chlamydia-infected cells that were treated with chloramphenicol (Cm25) at various time points postinfection. We observed that signaling only occurred in untreated cells and cells treated with Cm25 at or later than 22 hpi (Fig. 6A), roughly coinciding with the initiation of RB-to-EB conversion.

Figure 6. Chlamydia-specific TLR9 signaling in HEK293 cells occurs as a result of the RB-to-EB conversion.

(A) C. trachomatis-infected hTLR9-HEK293 reporter cells were treated with chloramphenicol (25 ug/mL; Cm25) at the time points indicated and SEAP activity was measured at 44hpi. (B) The effects of the LOS inhibitor LPC-011 on C. trachomatis-induced hTLR9 signaling. All columns represent mean values calculated for data acquired from three biological replicates and error bars represent standard error of the mean. Groups were compared via two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. ****, p ≤ 0.0001; ns, not significant.

The autolysis of C. trachomatis RBs has been described previously50, and it is commonly thought that a small subset of RBs within the inclusion will undergo lysis during the developmental cycle. We hypothesized that such lytic events are likely the cause of gDNA release within inclusions. Given the delay we observed in TLR9 signaling in our HEK293 report cells (Fig. 4A), we also hypothesized that the most likely time when gDNA is released from the microbe would be during the transition state between replicative and infectious forms. To examine the degree to which gDNA release impacted our Chlamydia-specific TLR9 signaling, we examined the effects of the LpxC inhibitor LPC-01151 on C. trachomatis-induced TLR9 signaling. LpxC carries out the 2nd step in the lipooligosaccharide (LOS) biosynthesis pathway, and while LOS biosynthesis is not required for the transition of Chlamydia EBs to RBs, nor for RB replication, it is required for the conversion of RBs into EBs at the end of the pathogen’s developmental cycle51,52. In the absence of LOS, RBs lyse during the conversion process. When infected HEK293 cells were treated with the LOS inhibitor LPC-011, a dose-respondent increase in Chlamydia-specific hTLR9 signaling was detected (Fig. 6B). Together, these observations support the hypothesis that C. trachomatis gDNA release in epithelial cells is the result of the process of RB-to-EB conversion.

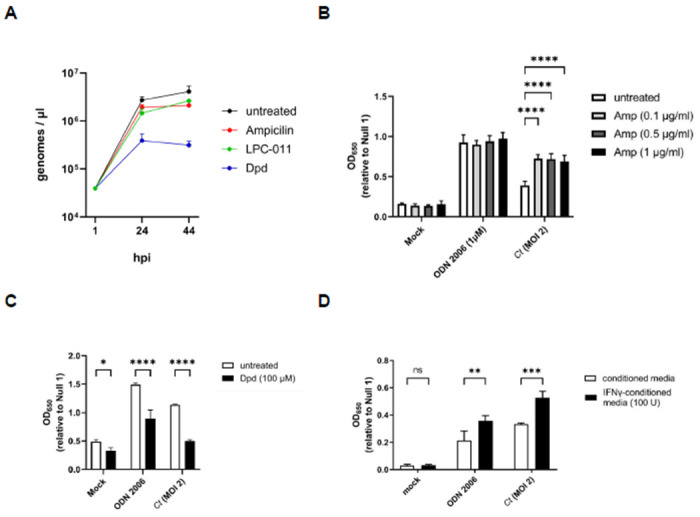

Persistence alters Chlamydia-induced hTLR9 signaling.

We have previously reported that stress-inducing conditions linked to the aberrant / persistent phenotype in C. trachomatis can directly affect the recognition of the pathogen by the Nod-like Receptor (NLR) NOD153. Prior studies have also found that these persistence-inducing conditions can affect the ability of Chlamydia and Chlamydia-related organisms to regulate DNA replication. While cell division is inhibited during persistence, some persistence-inducing conditions result in a marked reduction in chlamydial DNA replication54,55 while others result in the accumulation of 100s of genome copies residing within a single, enlarged bacterium55–59. Given that many of these ’aberran’ chlamydial forms exhibit evidence of membrane disruptions and structural defects60–62, we reasoned that DNA could likely be shed by these aberrant forms into the inclusion space. We also hypothesized that continued DNA replication would directly impact TLR9-stimulation by C. trachomatis, as the abundance of available ligand (gDNA) would likely correspond to the signaling potential of the microbe. We began by examining genome replication in C. trachomatis under aberrance induction by ampicillin and the iron chelator 2,2’-Dipyridyl (Dpd) over the course of the microbe’s developmental cycle (~44hpi). Similar to previously published results48, we found that the majority of C. trachomatis genome replication occurs within the first 24 hours post-infection under all the conditions tested, and that persistence induced by iron chelation resulted in ~1 log10 reduction in genome counts (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7. Persistence alters Chlamydia-induced hTLR9 signaling.

(A) C. trachomatis genome copies were measured in untreated cells as well as in cells infected in the presence of ampicillin, the iron chelator 2,2’-Dipyridyl (Dpd), and the LpxC inhibitor (LPC-011) over the span of 44 hours. Measurements were taken at 1, 24, and 44 hpi. (B-D) The effects of (B) ampicillin; Amp, (C) 2,2’-Dipyridyl; Dpd, and (D) tryptophan-depletion via interferon gamma (IFNγ) were accessed on hTLR9-stimulatory activity of ODN 2006 and infection by C. trachomatis. All columns represent mean values calculated for data acquired from three biological replicates and error bars represent standard error of the mean. Groups were compared via two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. ****, p ≤ 0.0001; ***, p ≤ 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p ≤ 0.05; ns, not significant.

Having assessed the relative differences in genome replication under a variety of persistence-inducing conditions, we next tested Chlamydia-infected cells under these same conditions over a 44-hour period in our hTLR9 HEK293 reporter assay. Antibiotics that target peptidoglycan are known to result in high levels of ’emporary polyploidy’ in the resulting chlamydial aberrant bodies55–59 and we observed that in the presence of ampicillin, C. trachomatis-induced TLR9 activity was significantly enhanced (Fig. 7B). Conversely, iron restriction is associated with a reduction in genome replication in Chlamydia and Chlamydia-like organisms (Fig. 7A,54,55) and we observed a marked decrease in TLR9 activity when infected cells were treated with the iron chelator 2,2-dipyridyl (Dpd) (Fig. 7C). However, we also observed that the condition impacted our positive control (ODN 2006), indicating that the effects on signaling are likely indirect. Tryptophan starvation resulting from treatment of primate-derived cells with interferon gamma (IFNγ) also results in the accumulation of large numbers of genome copies within single aberrant chlamydial bodies63,64, and we found that this condition significantly enhanced hTLR9 signaling (Fig. 7D), however, this was also not unique to Chlamydia-induced signaling as we saw significant enhancement in our positive control. Taken together, these data indicate that TLR9 signaling results from the release of gDNA from C. trachomatis within its inclusion and that, similar to NOD1 signaling53, ’persistence’-inducing conditions can affect both Chlamydia-specific and Chlamydia non-specific TLR9 signaling.

DISCUSSION

Our data indicates that C. trachomatis gDNA is a stimulatory ligand for both human and murine TLR9 and has a higher stimulatory potential than the murine pathogen C. muridarum. We found that TLR9 signaling from C. trachomatis was higher than that of C. muridarum in both in vitro testing of purified gDNA (Fig. 1) and live infections of reporter cells (Fig. 4B and Fig. 5). Given our data indicating that TLR9 signaling is impacted by the timing of the chlamydial developmental cycle (Fig. 4A and Fig. 6A) and bacterial load (Fig. 4A and Fig. 5), this is a particularly significant finding. C. muridarum has a higher replication rate and a shorter developmental cycle than C. trachomatis65, and thus likely releases gDNA into the inclusion earlier and at a higher abundance than C. trachomatis. The fact that C. muridarum TLR9 signaling is so much lower than C. trachomatis is likely the result of fewer CpG-stimulatory motifs present in its genome than are present in C. trachomatis. This difference in the immunostimulatory potential of the gDNA from of these two pathogens may have arisen due to differences in tissue/host-specific prevalence of TLR9. TLR9 was originally thought to be expressed in a number of cell types (such as macrophages) in mice66 and expressed in only a few specialized dendritic cell populations in humans67. However, more recent studies have brought this general consensus into question, and TLR9 is now known to be highly expressed in multiple cell types in both human and murine lung tissue68. Given its origin69 (and re-emergence70) as a murine lung pathogen, C. muridarum likely evolved under heightened selective pressure in this environment and the reduced stimulatory potential of its gDNA may be evidence of a pathoadaptation to this niche.

TLR9 haplotypes and polymorphisms have been previously shown to correlate with potential risk of cervicitis35, cervical cancer71, as well as susceptibility and the development of symptoms after HR-HPV and C. trachomatis infection36,72. TLR9-stimulatory adjuvants have also been used extensively in chlamydial vaccine development73–77. Despite this, TLR9 has been deemed to play only a minor role in chlamydial recognition during active infections. This general consensus has been based on studies investigating pattern recognition molecules generated by C. muridarum that are recognized by oviduct epithelial cell lines38 and assessing the impact of murine TLR9 on the clearance of C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae infections utilizing a TLR9−/− mouse infection model34,39. While these studies were well powered and well-controlled, they did not directly explore the interaction of either pathogen with the receptor at early stages of infection. The relatively high doses required to generate stable C. trachomatis infections in the murine model are likely due to the presence of innate immunological factors (such as TLR9) that are thought to play a larger role in preventing infections from occurring (particularly in the lower genital tract), rather than controlling them once they are established. By comparison, TLR238,78–82 and TLR47–9,83 are thought to play a critical role in controlling chlamydial infections. While TLR2 and TLR4 have been shown to be highly expressed in the upper genital tract, TLR9 as well as NOD-like Receptors (NLRs) 1 and 2 are expressed more uniformly throughout the upper and lower genital tract84. Similarly, the cGAS-STING signaling pathway, another innate DNA recognition system that grants heightened immunity to C. trachomatis infection, is notably restricted to the lower genital tract85.

Given that we observed co-localization of C. trachomatis inclusions with TLR9 in U937 cells (Fig.2), the availability of chlamydial gDNA in this circumstance is understandable. In macrophages and dendritic cells, the AP3 adaptor complex and the AP-3-interacting cation transporter (Slc15a4) are responsible for trafficking TLR9 from the early endosome to a specialized lysosome-related organelle where TLR9 then activates MYD88 signaling86. In contrast, while a number of TLRs (as well as their adaptor protein MYD88) associate with the chlamydial inclusions in epithelial cells78,87, these inclusions avoid fusing with endosomes / lysosomes88. Thus, while the mechanism for TLR9 interacting with gDNA from Chlamydia species in U937 cells is straightforward (bacterial lysis in lysosomes containing TLR9), the mechanism by which signaling occurs during live infections in our HEK293 report cells is not. Given that we observe signaling only on the second day post infection (Fig. 4A), we believe that TLR9 signaling under these conditions is the result of gDNA being released from a subset of chlamydial RBs that fail to successfully convert into EBs. Our data demonstrating 1) prevention of the RB to EB conversion eliminates TLR9 signaling (Fig. 6A) and 2) artificially enhancing the frequency of lysis events during conversion (utilizing the LpxC inhibitor) enhances TLR9 signaling (Fig. 6B) supports this proposition.

It is presently unclear how the gDNA that is released during RB lysis traffics to TLR9-containing endosomes in our HEK293 cells. Previous studies have indirectly demonstrated the presence of cytosolic chlamydial gDNA in infected cells in culture89,90, and we hypothesize that if chlamydia gDNA is capable of exiting the inclusion into the cell cytosol, this might enable it to eventually be trafficked to TLR9-containing compartments. To date, no direct mechanism has been proposed by which chlamydial DNA exits the inclusion. Evidence exists in multiple model systems that DNA transfer from a bacterium to a host cell can occur via type IV secretion systems (T4SS)91–93, but there exists no example of DNA being successfully transferred via the secretion systems utilized by C. trachomatis (ie. type II and type III secretion). Experiments investigating alternative trafficking route(s) of chlamydial gDNA from the inclusion to the TLR9 receptor and currently ongoing.

In addition to immune recognition, the presence of cytosolic chlamydial DNA in infected host cells has implications for other aspects of chlamydial biology, such as factors that influence genetic exchange between strains94 and potential barriers to inter-species gene flow. Chlamydia species undergo conversion from RBs to EBs in a rather disjointed fashion, and the reasons for this are not well understood. C. trachomatis encodes ComEC homologs that enable DNA uptake and lateral gene transfer95. These are presumably expressed predominantly in RBs, as most metabolic processes in chlamydial EBs are significantly reduced. Given our observations that C. trachomatis releases gDNA into its immediate environment during RB-to-EB transition events (Fig 6), it stands to reason that asynchronous conversion between developmental forms may have arisen, in part, due to the potential for genetic exchange between replicating RBs and RBs lysing during conversion. C. trachomatis inclusions exhibit homotypic fusion, in that multiple inclusions within a cell can fuse into a single, enlarged inclusion. This process is largely dependent on IncA96–98, a SNARE-like protein that is secreted by the chlamydial Type III secretion system and incorporates into the inclusion wall. Infections with different strains99,100 and mixed infections with different chlamydial species101,102 have been used to date to demonstrate the potential gene flow between Chlamydia species that are capable of residing within shared inclusions. Interestingly, genetic exchange between non-fusogenic species has also been observed102, suggesting that DNA trafficking between inclusions can also occur. Studies exploring the mechanism(s) by which gDNA transits to and from the host cell cytosol are presently ongoing.

Conclusions.

In this study, we demonstrate the stimulatory potential of Chlamydial gDNA for recognition by hTLR9 and mTLR9, show that hTLR9 colocalizes with chlamydial inclusions in the pro-monocytic cell line U937, demonstrate that under normal growth conditions Chlamydia-specific TLR9 signaling occurs during the stage in the pathogen’s developmental cycle when developmental form conversion occurs, and that the induction of aberrance can either enhance or diminish this signaling. The disjoining of genome replication and cell division that occurs during chlamydial persistence has been previously suggested to be a beneficial adaptation, enabling the microbe to rapidly proliferate via numerous, simultaneous cell division events upon the removal of stress-inducing conditions. Our data indicates that any such benefit likely comes with inherent costs in immune cells, specifically the recognition of immunostimulatory chlamydial gDNA by a hos’s innate immune defenses. We reason that persistence requires the evasion of immunological clearance mechanisms and as such, models of chlamydial persistence (to include those independent of the ’aberran’ phenotype103) that demonstrate this characteristic in vitro are more likely to correspond to phenotypes associated with persistence in animal models and human patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents:

Anti-TLR9 (AB134368) was purchased from Abcam and Invitrogen, respectively. Anti-MOMP (LS-C123239) was purchased from LSBio. LpxC inhibitor LPC-011 was graciously provided by Dr. Pei Zhou (Duke University).

Bacterial Strains and Cell Lines:

C. trachomatis serovar L2 strain 434/Bu, C. muridarum strain Nigg, and E. coli strain MG1655 were provided by Anthony Maurelli (University of Florida). Chlamydial stocks were generated utilizing HeLa-USU cells (also provided by Anthony Maurelli) unless otherwise noted. Whole cell lysate (’crude’) freezer stocks of chlamydial EBs were generated from HeLa cells 40 hours post infection and stored at −80° C in sucrose phosphate glutamic acid buffer (7.5% w/v sucrose, 17 mM Na2HPO4, 3 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM L-glutamic acid, pH 7.4) until use. Stocks were titered via inclusion forming unit (IFU) assay (described below). HEK-Blue-hTLR9, -mTLR9, and -Null1 cells were purchased from InvivoGen and propagated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell lines were passaged in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone). U937 cells were purchased from ATCC and propagated according to their instructions. All cell lines were checked for mycoplasma contamination 2 passages after the initial liquid nitrogen thaw, and every subsequent 10 passages.

Genomic DNA isolation:

Prior to the day of isolation, one 7 ml overnight culture of E. coli strain MG1655 was prepared. On the day of isolation, (4) 100 μl aliquot ’crude’ EB preparations of C. trachomatis serovar L2 strain 434/Bu and C. muridarum strain Nigg were thawed at room temperature. As stocks thawed, 6 ml of the overnight E. coli culture was centrifuged at 16,000 G for 2 minutes. gDNA from C. trachomatis, C. muridarum, and E. coli were then isolated using a Promega Genomic DNA Purification Kit. gDNA from each species was rehydrated in 50 μl of sterile, deionized water (Fischer) and placed in a 4° C fridge overnight. On the following day, aliquots were placed on ice and the concentration of gDNA was assessed via nanodrop. To sufficiently shear gDNA for use in TLR9 signaling assays, gDNA stocks were then pulse-sonicated ~10 times (sonicating for 3 seconds then pausing for 1 - 2 seconds), and placed on ice immediately after for at least 10 minutes. If not used the same day, gDNA stocks were then stored at −20° C.

Quantification of Inclusion Forming Units (IFU):

96 well tissue culture-treated plates (Fisher) are seeded 24 hours prior to IFU assays with 200μl per well of a 200,000 L2 cells/ml suspension in DMEM / 10% FBS (~40,000 cells per well). On the day of the assay, bacterial suspensions are thawed on ice and then serially diluted in infection medium [DMEM, 10% FBS, MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids (Sigma), 0.5μg/ml cycloheximide]. Spent media is removed from the 96 well plate and 200 μl of each chlamydia dilution is added to each well, with each dilution conducted in duplicate. Plates were then spun in a tabletop centrifuge (Eppendorf) at 3000 rpm at 35° C for 1 hour to synchronize infection and ensure that all infectious EBs come into contact with cell monolayers. Plates were then incubated for 24-28 hours at 37° C 5% CO2. At the desired hpi, infection medium was removed by suction, infected cells were fixed / permeabilized by the addition of 200 μl of ice-cold methanol and incubated at room temperature for ~10 minutes. The methanol was then aspirated and 1 drop of Pathfinder Chlamydia Culture Confirmation System (BioRad) was added to each well. Plates were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes, after which time the antibody staining solution was removed, wells were gently washed 3 times with deionized water, and 1 drop of glycerol mounting medium was added to each well. Plates were inverted, stored at 4° C and examined under an epifluorescence microscope (Olympus) within 24 hours. Total inclusion forming units (IFU) were calculated by counting the number of visible inclusions for 20 different imaging fields using the 40x objective.

C. trachomatis Infections of U937 cells:

For infecting U937 cells, ~2.5 x 105 cells / mL were spun down and resuspended in infection medium containing ~1x106 IFU of C. trachomatis (MOI ~4). 2.5 x 105 cells were then added to each well of a 24 well plate and placed in the incubator for 24 or 44 hours. For pre-stimulation experiments, ~2.5 x 105 cells / mL were spun down and resuspended in infection medium + / − 1μm ODN 2006 and incubated overnight at 37° C. The next morning, cells were spun down and resuspended in infection medium containing ~1x106 IFU of C. trachomatis (MOI ~4), 2.5 x 105 cells were then added to each well of a 24 well plate and placed in the incubator (at 37° C) for an additional 24 or 44 hours.

Fluorescence Microscopy / TLR9 and MOMP-labeling:

Briefly, HeLa cells were infected with C. trachomatis L2 434/Bu as described above. At indicated time points infection medium was removed, and cells were washed three times with 1× PBS. Cells were fixed and permeabilized with methanol for 5 min and gently washed three times with 1× PBS. Cells were then further permeabilized and blocked as described above. Cells were then washed with 3% BSA and incubated with donkey anti-mouse or donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1,000 in 3% BSA). For visualizing cell nuclei, cells were incubated with Hoechst stain for ~5 min and then washed with 3% BSA and 1× PBS.

For labeling TLR9 in infected U937 and HeLa cells, cells were fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min at room temperature and subsequently washed with 1× PBS. Cells were then permeabilized with 100% Methanol for 2 minutes, washed with 1 × PBS, and then blocked for 1 h with 1% BSA. Cells were then incubated with anti-MOMP and anti-TLR9 (1:100) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by several washes 3% BSA, and subsequent incubation with anti-goat and anti-rabbit conjugated antibodies (Alexa594 and Alexa488, respectively). Cells were then further washed with 3% BSA, PBS, and then coverslips were mounted on slides with ProLong gold antifade mounting medium and stored in the dark at 4°C prior to imaging via structured-illumination (Elyra PS.1) microscopy.

HEK-Blue hTLR9 and Null1 NF-κB reporter assay:

HEK-Blue cells expressing human or murine TLR9 and carrying the NF-κB SEAP (secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase) reporter gene (InvivoGen) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions and adapted to assess TLR-specific NF-κB activity induced via live C. trachomatis and isolated bacterial gDNA. Briefly, 3 × 105 cells/ml of HEK-Blue-hTLR9 or -Null1 cells were plated in 96-well plates (total reaction volume of 200 μl per well [~6.0 × 104 cells per well]) and allowed to settle/adhere overnight at 37°C. Media was then removed and replaced with 200 μl of medium containing either C. trachomatis (at the MOIs indicated), purified genomic DNA, or the known TLR9-stimulating ligand ODN 2006. Plates were then centrifuged for 1 h at 2,000 × g and subsequently incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C. Cell supernatants were collected at indicated time points for subsequent analysis of SEAP activity. A colorimetric reporter assay was then utilized to quantify the abundance of SEAP in cell supernatants. Twenty microliters of supernatant collected from infected cells was added to 180 μl of the SEAP detection solution (InvivoGen), followed by incubation at 37°C for ~6 h. SEAP enzymatic activity was then quantified using a plate reader set to 650 nm. Infected cells were compared to uninfected (media) controls and cells treated with ODN 2006 (positive control). To ensure that changes in alkaline phosphatase activity were TLR- dependent under each of the experimental conditions tested, all experiments were carried out in parallel in the HEK-Blue-Null1 cell line, which contains the empty expression vector but lacks TLR9. HEK-Blue TLR9 SEAP reporter assays were always carried out in three separate experiments, statistical analysis was conducted by either 1 -or 2-way ANOVA, and significance values were analyzed by utilizing Sidak’s multiple-comparison test.

Assessing Chlamydial genome copy number:

L2 cells in 24-well plates were infected with C. trachomatis L2 at MOI of 0.1 as described above. Total content of the wells was harvested at 1, 24 and 44 hpi and DNA was extracted using DNAeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen). Genome copy number quantitation was done by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using C. trachomatis 16S rRNA primer-probe mix (Forward 5’-GTAGCGGTGAAATGCGTAGA-3’, Reverse 5’-CGCCTTAGCGTCAGGTATAAA-3’, Probe 5’-ATGTGGAAGAACACCAGTGGCGAA-3’) (Integrated DNA Technologies), iTaq universal probes supermix (Bio-Rad) and 1 μl DNA as template. PCR reaction (40 cycles) was done on a CFX96 qPCR machine (Bio-Rad) using following conditions: initial denaturation 95°C for 3 min, denaturation 95°C for 5s and annealing/extension 60°C for 30s. Genome copy number was determined using a standard curve generated from serial dilutions of genomic DNA from purified EBs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Anthony Maurelli (University of Florida) and his laboratory for providing us with the strains used in this work as well as helpful feedback during the development of this project and drafting of the manuscript. We would also like to thank Dr. Pei Zhou (Duke University) for graciously providing us with the LpxC inhibitor used in this work. This work was supported by a MIRA ESI award (R35 GM138202) and a USU faculty start up award (HP73LIEC18) to GL. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University or the Department of Defense.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stelzner K., Vollmuth N. & Rudel T. Intracellular lifestyle of Chlamydia trachomatis and host-pathogen interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 21, 448–462 (2023). 10.1038/s41579-023-00860-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong W. F., Chambers J. P., Gupta R. & Arulanandam B. P. Chlamydia and Its Many Ways of Escaping the Host Immune System. J Pathog 2019, 8604958 (2019). 10.1155/2019/8604958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yadav S., V. V., Dhanda R.S., Yadav M. Insights into the toll-like receptors in sexually transmitted infections. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray S. M. & McKay P. F. Chlamydia trachomatis: Cell biology, immunology and vaccination. Vaccine 39, 2965–2975 (2021). 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao X. et al. Role of Toll-Like Receptors in Common Infectious Diseases of the Female Lower Genital Tract. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 28, 232 (2023). 10.31083/j.fbl2809232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zou Y., Lei W., He Z. & Li Z. The role of NOD1 and NOD2 in host defense against chlamydial infection. FEMS Microbiol Lett 363 (2016). 10.1093/femsle/fnw170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heine H., Muller-Loennies S., Brade L., Lindner B. & Brade H. Endotoxic activity and chemical structure of lipopolysaccharides from Chlamydia trachomatis serotypes E and L2 and Chlamydophila psittaci 6BC. Eur J Biochem 270, 440–450 (2003). 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03392.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heine H., Gronow S., Zamyatina A., Kosma P. & Brade H. Investigation on the agonistic and antagonistic biological activities of synthetic Chlamydia lipid A and its use in in vitro enzymatic assays. J Endotoxin Res 13, 126–132 (2007). 10.1177/0968051907079122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ingalls R. R. et al. The inflammatory cytokine response to Chlamydia trachomatis infection is endotoxin mediated. Infect Immun 63, 3125–3130 (1995). 10.1128/iai.63.8.3125-3130.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenkin H. M. Preparation and properties of cell walls of the agent of meningopneumonitis. J Bacteriol 80, 639–647 (1960). 10.1128/jb.80.5.639-647.1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perkins H. R. & Allison A. C. Cell-wall constituents of rickettsiae and psittacosis-lymphogranuloma organisms. J Gen Microbiol 30, 469–480 (1963). 10.1099/00221287-30-3-469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrett A. J., Harrison M. J. & Manire G. P. A search for the bacterial mucopeptide component, muramic acid, in Chlamydia. J Gen Microbiol 80, 315–318 (1974). 10.1099/00221287-80-1-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liechti G. W. et al. A new metabolic cell-wall labelling method reveals peptidoglycan in Chlamydia trachomatis. Nature 506, 507–510 (2014). 10.1038/nature12892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liechti G. et al. Pathogenic Chlamydia Lack a Classical Sacculus but Synthesize a Narrow, Mid-cell Peptidoglycan Ring, Regulated by MreB, for Cell Division. PLoS Pathog 12, e1005590 (2016). 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen H., Wen Y. & Li Z. Clear Victory for Chlamydia: The Subversion of Host Innate Immunity. Front Microbiol 10, 1412 (2019). 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemmi H. et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature 408, 740–745 (2000). 10.1038/35047123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemmi H., Kaisho T., Takeda K. & Akira S. The roles of Toll-like receptor 9, MyD88, and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit in the effects of two distinct CpG DNAs on dendritic cell subsets. J Immunol 170, 3059–3064 (2003). 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klinman D. M. Immunotherapeutic uses of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Nat Rev Immunol 4, 249–258 (2004). 10.1038/nri1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latz E., Visintin A., Espevik T. & Golenbock D. T. Mechanisms of TLR9 activation. J Endotoxin Res 10, 406–412 (2004). 10.1179/096805104225006525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latz E. et al. TLR9 signals after translocating from the ER to CpG DNA in the lysosome. Nat Immunol 5, 190–198 (2004). 10.1038/ni1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scidmore M. A., Fischer E. R. & Hackstadt T. Restricted fusion of Chlamydia trachomatis vesicles with endocytic compartments during the initial stages of infection. Infect Immun 71, 973–984 (2003). 10.1128/IAI.71.2.973-984.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ronzone E. & Paumet F. Two coiled-coil domains of Chlamydia trachomatis IncA affect membrane fusion events during infection. PLoS One 8, e69769 (2013). 10.1371/journal.pone.0069769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paumet F. et al. Intracellular bacteria encode inhibitory SNARE-like proteins. PLoS One 4, e7375 (2009). 10.1371/journal.pone.0007375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinzen R. A., Scidmore M. A., Rockey D. D. & Hackstadt T. Differential interaction with endocytic and exocytic pathways distinguish parasitophorous vacuoles of Coxiella burnetii and Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun 64, 796–809 (1996). 10.1128/iai.64.3.796-809.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rzomp K. A., Scholtes L. D., Briggs B. J., Whittaker G. R. & Scidmore M. A. Rab GTPases are recruited to chlamydial inclusions in both a species-dependent and species-independent manner. Infect Immun 71, 5855–5870 (2003). 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5855-5870.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cortina M. E., Bishop R. C., DeVasure B. A., Coppens I. & Derre I. The inclusion membrane protein IncS is critical for initiation of the Chlamydia intracellular developmental cycle. PLoS Pathog 18, e1010818 (2022). 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Del Balzo D., Capmany A., Cebrian I. & Damiani M. T. Chlamydia trachomatis Infection Impairs MHC-I Intracellular Trafficking and Antigen Cross-Presentation by Dendritic Cells. Front Immunol 12, 662096 (2021). 10.3389/fimmu.2021.662096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun H. S. et al. Chlamydia trachomatis vacuole maturation in infected macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 92, 815–827 (2012). 10.1189/jlb.0711336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Zeer M. A., Al-Younes H. M., Lauster D., Abu Lubad M. & Meyer T. F. Autophagy restricts Chlamydia trachomatis growth in human macrophages via IFNG-inducible guanylate binding proteins. Autophagy 9, 50–62 (2013). 10.4161/auto.22482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yasir M., Pachikara N. D., Bao X., Pan Z. & Fan H. Regulation of chlamydial infection by host autophagy and vacuolar ATPase-bearing organelles. Infect Immun 79, 4019–4028 (2011). 10.1128/IAI.05308-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gracey E., Lin A., Akram A., Chiu B. & Inman R. D. Intracellular survival and persistence of Chlamydia muridarum is determined by macrophage polarization. PLoS One 8, e69421 (2013). 10.1371/journal.pone.0069421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lundberg P., Welander P., Han X. & Cantin E. Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA is immunostimulatory in vitro and in vivo. J Virol 77, 11158–11169 (2003). 10.1128/jvi.77.20.11158-11169.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singer M., de Waaij D. J., Morre S. A. & Ouburg S. CpG DNA analysis of bacterial STDs. BMC Infect Dis 15, 273 (2015). 10.1186/s12879-015-1016-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ouburg S. et al. TLR9 KO mice, haplotypes and CPG indices in Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Drugs Today (Barc) 45 Suppl B, 83–93 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chauhan A. et al. Association of TLR4 and TLR9 gene polymorphisms and haplotypes with cervicitis susceptibility. PLoS One 14, e0220330 (2019). 10.1371/journal.pone.0220330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verweij S. P. et al. TLR2, TLR4 and TLR9 genotypes and haplotypes in the susceptibility to and clinical course of Chlamydia trachomatis infections in Dutch women. Pathog Dis 74, ftv107 (2016). 10.1093/femspd/ftv107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Indira Beishova B. N., Alena Belaya, Gulzhagan Chuzhebayeva, Vadim Ulyanov,, Tatyana Ulyanova, A. K., Laura Dushayeva, Kenzhebek Murzabayev, & Ainura Taipova, A. Z. a. A. I. Marking of Genetic Resistance to Chlamydia, Brucellosis and Mastitis in Holstein Cows by Using Polymorphic Variants of LTF, MBL1 and TLR9 Genes. American Journal of Animal and Veterinary Sciences (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Derbigny W. A., Kerr M. S. & Johnson R. M. Pattern recognition molecules activated by Chlamydia muridarum infection of cloned murine oviduct epithelial cell lines. J Immunol 175, 6065–6075 (2005). 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothfuchs A. G., Trumstedt C., Wigzell H. & Rottenberg M. E. Intracellular bacterial infection-induced IFN-gamma is critically but not solely dependent on Toll-like receptor 4-myeloid differentiation factor 88-IFN-alpha beta-STAT1 signaling. J Immunol 172, 6345–6353 (2004). 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leifer C. A. et al. TLR9 is localized in the endoplasmic reticulum prior to stimulation. J Immunol 173, 1179–1183 (2004). 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chockalingam A., Brooks J. C., Cameron J. L., Blum L. K. & Leifer C. A. TLR9 traffics through the Golgi complex to localize to endolysosomes and respond to CpG DNA. Immunol Cell Biol 87, 209–217 (2009). 10.1038/icb.2008.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kayraklioglu N., Horuluoglu B. & Klinman D. M. CpG Oligonucleotides as Vaccine Adjuvants. Methods Mol Biol 2197, 51–85 (2021). 10.1007/978-1-0716-0872-2_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shintani Y. et al. TLR9 mediates cellular protection by modulating energy metabolism in cardiomyocytes and neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110, 5109–5114 (2013). 10.1073/pnas.1219243110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim S. K., Choe J. Y. & Park K. Y. Activation of CpG-ODN-Induced TLR9 Signaling Inhibited by Interleukin-37 in U937 Human Macrophages. Yonsei Med J 62, 1023–1031 (2021). 10.3349/ymj.2021.62.11.1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ward G. A. et al. Oxidized Mitochondrial DNA Engages TLR9 to Activate the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Int J Mol Sci 24 (2023). 10.3390/ijms24043896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kavsan V. M., Iershov A. V. & Balynska O. V. Immortalized cells and one oncogene in malignant transformation: old insights on new explanation. BMC Cell Biol 12, 23 (2011). 10.1186/1471-2121-12-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bauer S. et al. Human TLR9 confers responsiveness to bacterial DNA via species-specific CpG motif recognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98, 9237–9242 (2001). 10.1073/pnas.161293498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miyairi I., Mahdi O. S., Ouellette S. P., Belland R. J. & Byrne G. I. Different growth rates of Chlamydia trachomatis biovars reflect pathotype. J Infect Dis 194, 350–357 (2006). 10.1086/505432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee J. K. et al. Replication-dependent size reduction precedes differentiation in Chlamydia trachomatis. Nat Commun 9, 45 (2018). 10.1038/s41467-017-02432-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsumoto A. Structural characteristics of chlamydial bodies. (CRC Press, 1988). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nguyen B. D. et al. Lipooligosaccharide is required for the generation of infectious elementary bodies in Chlamydia trachomatis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 10284–10289 (2011). 10.1073/pnas.1107478108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cram E. D., Rockey D. D. & Dolan B. P. Chlamydia spp. development is differentially altered by treatment with the LpxC inhibitor LPC-011. BMC Microbiol 17, 98 (2017). 10.1186/s12866-017-0992-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brockett M. R. & Liechti G. W. Persistence Alters the Interaction between Chlamydia trachomatis and Its Host Cell. Infect Immun 89, e0068520 (2021). 10.1128/IAI.00685-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pokorzynski N. D., Brinkworth A. J. & Carabeo R. A bipartite iron-dependent transcriptional regulation of the tryptophan salvage pathway in Chlamydia trachomatis. Elife 8 (2019). 10.7554/eLife.42295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scherler A., Jacquier N., Kebbi-Beghdadi C. & Greub G. Diverse Stress-Inducing Treatments cause Distinct Aberrant Body Morphologies in the Chlamydia-Related Bacterium, Waddlia chondrophila. Microorganisms 8 (2020). 10.3390/microorganisms8010089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gordon F. B. & Quan A. L. Susceptibility of Chlamydia to antibacterial drugs: test in cell cultures. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2, 242–244 (1972). 10.1128/AAC.2.3.242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gerard H. C. et al. Expression of Chlamydia trachomatis genes encoding products required for DNA synthesis and cell division during active versus persistent infection. Mol Microbiol 41, 731–741 (2001). 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02550.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lambden P. R., Pickett M. A. & Clarke I. N. The effect of penicillin on Chlamydia trachomatis DNA replication. Microbiology (Reading) 152, 2573–2578 (2006). 10.1099/mic.0.29032-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kintner J., Lajoie D., Hall J., Whittimore J. & Schoborg R. V. Commonly prescribed beta-lactam antibiotics induce C. trachomatis persistence/stress in culture at physiologically relevant concentrations. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4, 44 (2014). 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang J. et al. Altered protein secretion of Chlamydia trachomatis in persistently infected human endocervical epithelial cells. Microbiology (Reading) 157, 2759–2771 (2011). 10.1099/mic.0.044917-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frohlich K. M. et al. Membrane vesicle production by Chlamydia trachomatis as an adaptive response. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4, 73 (2014). 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsumoto A. & Manire G. P. Electron microscopic observations on the effects of penicillin on the morphology of Chlamydia psittaci. J Bacteriol 101, 278–285 (1970). 10.1128/jb.101.1.278-285.1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lewis M. E. et al. Morphologic and molecular evaluation of Chlamydia trachomatis growth in human endocervix reveals distinct growth patterns. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4, 71 (2014). 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muramatsu M. K. et al. Beyond Tryptophan Synthase: Identification of Genes That Contribute to Chlamydia trachomatis Survival during Gamma Interferon-Induced Persistence and Reactivation. Infect Immun 84, 2791–2801 (2016). 10.1128/IAI.00356-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lyons J. M., Ito J. I. Jr., Pena A. S. & Morre S. A. Differences in growth characteristics and elementary body associated cytotoxicity between Chlamydia trachomatis oculogenital serovars D and H and Chlamydia muridarum. J Clin Pathol 58, 397–401 (2005). 10.1136/jcp.2004.021543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.An H. et al. Up-regulation of TLR9 gene expression by LPS in mouse macrophages via activation of NF-kappaB, ERK and p38 MAPK signal pathways. Immunol Lett 81, 165–169 (2002). 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00010-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kadowaki N. et al. Subsets of human dendritic cell precursors express different toll-like receptors and respond to different microbial antigens. The Journal of experimental medicine 194, 863–869 (2001). 10.1084/jem.194.6.863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schneberger D., Caldwell S., Kanthan R. & Singh B. Expression of Toll-like receptor 9 in mouse and human lungs. J Anat 222, 495–503 (2013). 10.1111/joa.12039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nigg C. & Eaton M. D. Isolation from Normal Mice of a Pneumotropic Virus Which Forms Elementary Bodies. The Journal of experimental medicine 79, 497–510 (1944). 10.1084/jem.79.5.497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mishkin N. et al. Reemergence of the Murine Bacterial Pathogen Chlamydia muridarum in Research Mouse Colonies. Comp Med 72, 230–242 (2022). 10.30802/AALAS-CM-22-000045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pandey N. O. et al. Association of TLR4 and TLR9 polymorphisms and haplotypes with cervical cancer susceptibility. Sci Rep 9, 9729 (2019). 10.1038/s41598-019-46077-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang C. et al. Association of TLR4 and TLR9 gene polymorphisms with cervical HR-HPV infection status in Chinese Han population. BMC Infect Dis 23, 152 (2023). 10.1186/s12879-023-08116-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pal S., Peterson E. M. & de la Maza L. M. Vaccination with the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein can elicit an immune response as protective as that resulting from inoculation with live bacteria. Infect Immun 73, 8153–8160 (2005). 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8153-8160.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cong Y. et al. Intranasal immunization with chlamydial protease-like activity factor and CpG deoxynucleotides enhances protective immunity against genital Chlamydia muridarum infection. Vaccine 25, 3773–3780 (2007). 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang J. et al. A chlamydial type III-secreted effector protein (Tarp) is predominantly recognized by antibodies from humans infected with Chlamydia trachomatis and induces protective immunity against upper genital tract pathologies in mice. Vaccine 27, 2967–2980 (2009). 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yu H. et al. Chlamydia muridarum T-cell antigens formulated with the adjuvant DDA/TDB induce immunity against infection that correlates with a high frequency of gamma interferon (IFN-gamma)/tumor necrosis factor alpha and IFN-gamma/interleukin-17 double-positive CD4+ T cells. Infect Immun 78, 2272–2282 (2010). 10.1128/IAI.01374-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pal S. et al. Vaccination with the recombinant major outer membrane protein elicits long-term protection in mice against vaginal shedding and infertility following a Chlamydia muridarum genital challenge. NPJ Vaccines 5, 90 (2020). 10.1038/s41541-020-00239-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.O’Connell C. M., Ionova I. A., Quayle A. J., Visintin A. & Ingalls R. R. Localization of TLR2 and MyD88 to Chlamydia trachomatis inclusions. Evidence for signaling by intracellular TLR2 during infection with an obligate intracellular pathogen. J Biol Chem 281, 1652–1659 (2006). 10.1074/jbc.M510182200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Massari P., Toussi D. N., Tifrea D. F. & de la Maza L. M. Toll-like receptor 2-dependent activity of native major outer membrane protein proteosomes of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun 81, 303–310 (2013). 10.1128/IAI.01062-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang Y. et al. Chlamydial Lipoproteins Stimulate Toll-Like Receptors 1/2 Mediated Inflammatory Responses through MyD88-Dependent Pathway. Front Microbiol 8, 78 (2017). 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beckett E. L. et al. TLR2, but not TLR4, is required for effective host defence against Chlamydia respiratory tract infection in early life. PLoS One 7, e39460 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0039460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Darville T. et al. Toll-like receptor-2, but not Toll-like receptor-4, is essential for development of oviduct pathology in chlamydial genital tract infection. J Immunol 171, 6187–6197 (2003). 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bulut Y. et al. Chlamydial heat shock protein 60 activates macrophages and endothelial cells through Toll-like receptor 4 and MD2 in a MyD88-dependent pathway. J Immunol 168, 1435–1440 (2002). 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hafner L. M., Cunningham K. & Beagley K. W. Ovarian steroid hormones: effects on immune responses and Chlamydia trachomatis infections of the female genital tract. Mucosal Immunol 6, 859–875 (2013). 10.1038/mi.2013.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Su X. et al. Evidence for cGAS-STING Signaling in the Female Genital Tract Resistance to Chlamydia trachomatis Infection. Infect Immun 90, e0067021 (2022). 10.1128/iai.00670-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Blasius A. L. et al. Slc15a4, AP-3, and Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome proteins are required for Toll-like receptor signaling in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, 19973–19978 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.1014051107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang C. et al. Chlamydia evasion of neutrophil host defense results in NLRP3 dependent myeloid-mediated sterile inflammation through the purinergic P2X7 receptor. Nat Commun 12, 5454 (2021). 10.1038/s41467-021-25749-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Elwell C., Mirrashidi K. & Engel J. Chlamydia cell biology and pathogenesis. Nature reviews. Microbiology 14, 385–400 (2016). 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang Y. et al. The DNA sensor, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase, is essential for induction of IFN-beta during Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J Immunol 193, 2394–2404 (2014). 10.4049/jimmunol.1302718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bishop R. C. & Derre I. The Chlamydia trachomatis Inclusion Membrane Protein CTL0390 Mediates Host Cell Exit via Lysis through STING Activation. Infect Immun 90, e0019022 (2022). 10.1128/iai.00190-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bundock P., den Dulk-Ras A., Beijersbergen A. & Hooykaas P. J. Trans-kingdom T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J 14, 3206–3214 (1995). 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07323.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hamilton H. L. & Dillard J. P. Natural transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: from DNA donation to homologous recombination. Mol Microbiol 59, 376–385 (2006). 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04964.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Varga M. G. et al. Pathogenic Helicobacter pylori strains translocate DNA and activate TLR9 via the cancer-associated cag type IV secretion system. Oncogene 35, 6262–6269 (2016). 10.1038/onc.2016.158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Demars R., Weinfurter J., Guex E., Lin J. & Potucek Y. Lateral gene transfer in vitro in the intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis. J Bacteriol 189, 991–1003 (2007). 10.1128/JB.00845-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.LaBrie S. D. et al. Transposon Mutagenesis in Chlamydia trachomatis Identifies CT339 as a ComEC Homolog Important for DNA Uptake and Lateral Gene Transfer. mBio 10 (2019). 10.1128/mBio.01343-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hackstadt T., Scidmore-Carlson M. A., Shaw E. I. & Fischer E. R. The Chlamydia trachomatis IncA protein is required for homotypic vesicle fusion. Cell Microbiol 1, 119–130 (1999). 10.1046/j.1462-5822.1999.00012.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Suchland R. J., Rockey D. D., Bannantine J. P. & Stamm W. E. Isolates of Chlamydia trachomatis that occupy nonfusogenic inclusions lack IncA, a protein localized to the inclusion membrane. Infect Immun 68, 360–367 (2000). 10.1128/IAI.68.1.360-367.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cingolani G. et al. Structural basis for the homotypic fusion of chlamydial inclusions by the SNARE-like protein IncA. Nat Commun 10, 2747 (2019). 10.1038/s41467-019-10806-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.DeMars R. & Weinfurter J. Interstrain gene transfer in Chlamydia trachomatis in vitro: mechanism and significance. J Bacteriol 190, 1605–1614 (2008). 10.1128/JB.01592-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jeffrey B. M., Suchland R. J., Eriksen S. G., Sandoz K. M. & Rockey D. D. Genomic and phenotypic characterization of in vitro-generated Chlamydia trachomatis recombinants. BMC Microbiol 13, 142 (2013). 10.1186/1471-2180-13-142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Suchland R. J. et al. Chromosomal Recombination Targets in Chlamydia Interspecies Lateral Gene Transfer. J Bacteriol 201 (2019). 10.1128/JB.00365-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Suchland R. J., Sandoz K. M., Jeffrey B. M., Stamm W. E. & Rockey D. D. Horizontal transfer of tetracycline resistance among Chlamydia spp. in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53, 4604–4611 (2009). 10.1128/AAC.00477-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rockey D. D., Wang X., Debrine A., Grieshaber N. & Grieshaber S. S. Metabolic dormancy in Chlamydia trachomatis treated with different antibiotics. Infect Immun, e0033923 (2024). 10.1128/iai.00339-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]